https://ebookmass.com/product/the-making-of-a-modern-temple-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

A

Nation Fermented: Beer, Bavaria, and the Making of Modern Germany Robert Shea Terrell

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-nation-fermented-beer-bavaria-and-themaking-of-modern-germany-robert-shea-terrell/

ebookmass.com

Muslims and the Making of Modern Europe Emily Greble

https://ebookmass.com/product/muslims-and-the-making-of-modern-europeemily-greble/

ebookmass.com

Reconstructing the Temple: The Royal Rhetoric of Temple Renovation in the Ancient Near East and Israel Andrew R. Davis

https://ebookmass.com/product/reconstructing-the-temple-the-royalrhetoric-of-temple-renovation-in-the-ancient-near-east-and-israelandrew-r-davis/ ebookmass.com

An Introduction to English Legal History 5th Edition John

Baker

https://ebookmass.com/product/an-introduction-to-english-legalhistory-5th-edition-john-baker/

ebookmass.com

Tattered Huntress (Thrill of the Hunt Book 1) Helen Harper

https://ebookmass.com/product/tattered-huntress-thrill-of-the-huntbook-1-helen-harper/

ebookmass.com

Comptia Security+ Guide to Network Security Fundamentals 7th Edition Mark Ciampa

https://ebookmass.com/product/comptia-security-guide-to-networksecurity-fundamentals-7th-edition-mark-ciampa/

ebookmass.com

Design and analysis of centrifugal compressors Van Den Braembussche

https://ebookmass.com/product/design-and-analysis-of-centrifugalcompressors-van-den-braembussche/

ebookmass.com

(eBook PDF) Strategic Human Resource Management 5th Edition by Jeffrey A. Mello

https://ebookmass.com/product/ebook-pdf-strategic-human-resourcemanagement-5th-edition-by-jeffrey-a-mello/

ebookmass.com

Lege

et Lacrima (Lost Hope Book

1) Alina Comsa

https://ebookmass.com/product/lege-et-lacrima-lost-hope-book-1-alinacomsa/

ebookmass.com

Health Psychology Consultation in the Inpatient Medical Setting 1st Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/health-psychology-consultation-in-theinpatient-medical-setting-1st-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

The Making of a Modern Temple and a Hindu City

The Making of a Modern Temple and a Hindu City

Kālīghāt and Kol K ata

Deonnie Moo D ie

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Moodie, Deonnie, 1981– author.

Title: The making of a modern temple and a Hindu city : Kālīghāṭ and Kolkata / Deonnie Moodie.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018015454 (print) | LCCN 2018040622 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190885274 (updf) | ISBN 9780190885281 (epub) | ISBN 9780190885267 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780190885298 (online content)

Subjects: LCSH: Kālīghāṭa (Temple : Kolkata, India) | Hindu temples—India—Kolkata. | Middle class—Religious life—India—Kolkata. | Kolkata (India)—Religious life and customs.

Classification: LCC BL1243.76.C352 (ebook) |

LCC BL1243.76.C352 K355 2018 (print) | DDC 294.5/350954147—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018015454

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

This book is dedicated to all of the Kolkata-wālās and -wālīs who shared with me their love of Kālī and their city. Without them, this work would not have been possible.

CONTENTS

List of Figures ix

Acknowledgments xi

Notes on Translation and Transliteration xv

Introduction: The Temples of Modern India 1

1. Reviving and Reforming Calcutta’s Hindu Past 37

2. A Religious Institution Goes Public 67

3. Sacred Space Becomes Public Space 99

4. Resisting Middle-Class Modernizing Projects 135

Conclusion: Bourgeoisifying Hinduisms and Hindu-izing Cities 161

Notes 171

Bibliography 189

Index 205

FIGURES

I.1 Murti of Kālī in the Inner Sanctum of Kālīghāṭ 2

I.2 Photo of Kālīghāṭ from Northeastern Corner 5

I.3 Photo of a Flower Seller Inside the Kālīghāṭ Temple Courtyard 6

I.4 A Hawker’s Stall in Front of the Temple 7

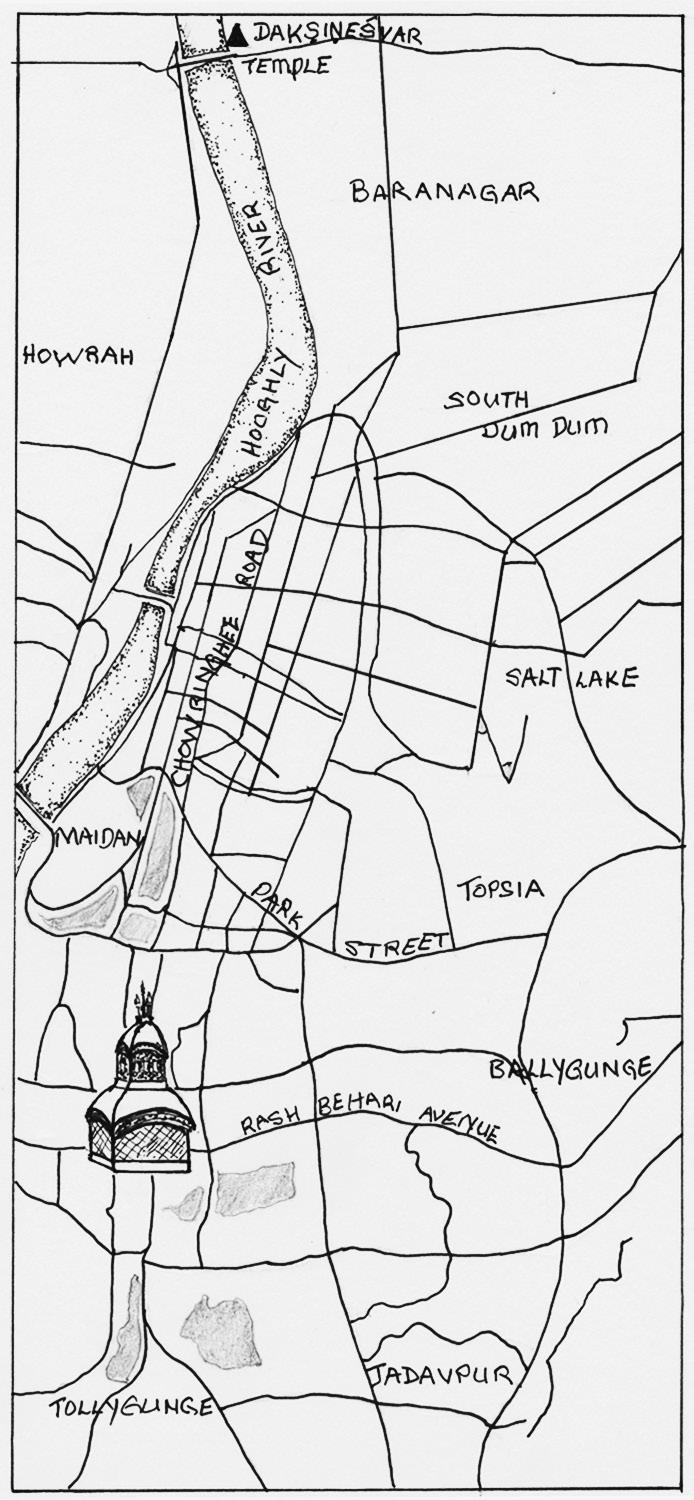

I.5 Map of Kolkata 8

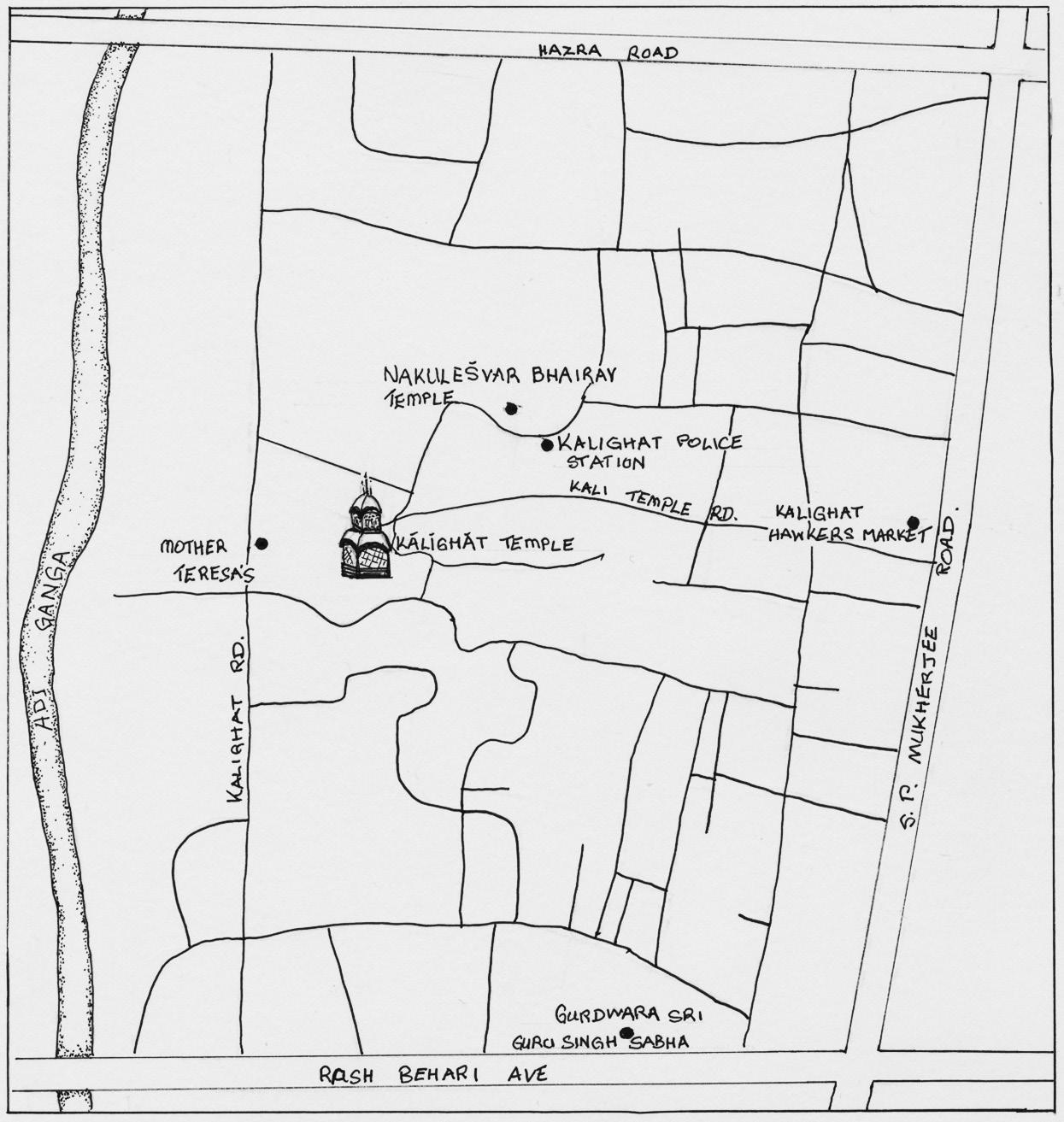

I.6 Map of the Kālīghāṭ Neighborhood 9

I.7 Plan of Kālīghāṭ Temple 10

I.8 Photo of the Office Exterior of the International Foundation of Sustainable Development 16

1.1 Drawing of the Kālīghāṭ Courtyard Circa 1891 from the Western Side 39

1.2 Map of the Kālīghāṭ Neighborhood Circa 1891 40

1.3 Conjectural Map of Sutānuṭi, Kalikātā, and Govindapur Villages Prior to the Arrival of Job Charnock 45

1.4 Boundaries of “White Town” as Variously Defined During the Colonial Period 48

2.1 Comparison of the Kālīghāṭ Temple Committee’s Composition According to High Court and Supreme Court Rulings in 1956 and 1961 93

3.1a–e The International Foundation for Sustainable Development’s Architectural Plans for Kālīghāṭ and Its Surroundings 115

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

It was boyd wilson who first introduced me to India. For over two decades, he led groups of American undergraduates on month-long immersion programs traversing the subcontinent. Of all the historic and sacred sites he introduced my peers and me to during the sweltering May month of 2002, Kālīghāṭ is the one that most captivated me. I have spent the ensuing decade and a half working to understand the role this site plays in the lives of those who make use of it. The book before you would not have been possible without Boyd.

Anne Monius read countless drafts of my dissertation—the work that provides the basis for this one—and provided critical and detailed feedback at every step. She is a model advisor and mentor who has shown tireless dedication to my development as a scholar and as a person. Thank you to Brian Hatcher, who generously provided many remarks on multiple versions of my dissertation and then my book proposal. I am indebted both to him and to fellow scholar of Bengal, Rachel McDermott, for providing a great deal of support for my developing research. Thank you also to Rebecca Manring and Tony Stewart, who aided in my (and many others’) initial study of Bengali in Dhaka, and to Maya De, Protima Dutt, Prasenjit Dey, and Indrani Bhattacarya for their help and encouragement as I translated many of the Bengali works referenced here. I am also deeply indebted to Diana Eck and Michael Jackson for their support and guidance throughout the 10 years of my graduate education, and for their insightful comments on this and much of my other writing. The research for this book was funded by a generous grant from the Fulbright-Nehru Student Research Program in 2011 and 2012. Thank you to Professor Arun Bandopadhyay of the University of Calcutta, who guided my research in Kolkata. I am also grateful to Rajshekar Basu, Uma Chattopadhyay, and Amit Dey of the University of Calcutta; Himadri Banerjee and Ruby Sain

of Jadavpur University; Partho Datta at Delhi University; Kunal Chakrabarty at Jawaharlal Nehru University; as well as Gautum Bhadro, Partha Chatterjee, Keya Dasgupta, and Tapati Guha-Thakurta at the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, for their guidance during the period of my research. Many thanks to the historians in Kolkata who provided support and invaluable insights into my work, including Haripad Bhoumick, Debasish Bose, P. T. Nair, and Abhik Ray. Thank you also to Shevanti Narayan and Sumanta Basu at the United States–India Educational Foundation for their help in many aspects of my work in Kolkata.

Hena Basu, who has facilitated the work of many scholars of Bengal over the decades, helped me navigate many of the city’s libraries, social networks, and even its courtrooms. She collected countless newspaper articles and translated a number of works for me both while I was in Kolkata and upon my return. My thanks go to her and to the many others who connected me to resources in the city, including Ashim Mukhopadhyay at the National Library, Abhijit Bhattacarya at the library of the Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta, Saktidas Ray at the Ananda Bazar Patrika archives, Arun Kumar Roy at the Kolkata Municipal Corporation, and Anirban Das Gupta of Das Gupta & Co. Bookshop.

Many of the people who were kind enough to speak with me about this project are cited in the following pages. I want to thank a few of them here specifically, not only for their help in my research, but for their friendship: Probal Ray Choudhury and his family, Dilip Haldar and his family, Gopal Mukherjee and his family, Gora and Maitreyi Mukherjee, Arun Kumar Mukherjee, Ashok Banerjee (sevāyet), Ashok Banerjee (Government Pleader), Mridul Pathak, Partha Ghosh, Prahlad Roy Goenka, Debasish Mitra, Nayan Mitra, Anjan Mitra, Jayanta Bagchi, Pyarilal Datta, Swapan and Bhaswati Chakrabarty, Debasish Chakrabarty, Darshi and Raj Dutt, Linika, Kanta Chatterjee, Mira Kakkar, Tinku Khanna, Aloka Mitra, Mousami Rao, Sugandha Ramkumar, Rekha Gupta, B. N. Das, Laxmi and K. S. Parasuram, Ranabir Chakrabarty, Amarjit Sethi, Shanti Bhattcarya, Alok Banerjee, Ananta Charan Kar, Pallab Mitra, Molloy Ghosh, and the pāṇḍās of Kalighat, including Dipu, Gopal, and Bicchu. Finally, thank you to the women of Kālīghāṭ, especially Rina and Ashtami, for their hospitality and grace.

In the transformation of this research into a book, I owe a great debt to my colleagues at the University of Oklahoma, especially Jill Hicks-Keeton, Charles Kimball, David Vishanoff, and Mara Willard. Conversations with each of these individuals have been invaluable in reworking and fine-tuning my ideas. Many thanks to the organizers of the American Institute of Indian Studies’ “Dissertation-to-Book Workshop” at the Annual Conference on

South Asia at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. Geraldine Forbes and Karen McNamara, among others, provided fruitful feedback on a previous version of this manuscript during that workshop in 2014. I am also grateful to Joanne Waghorne, Sanjay Joshi, and David Vishanoff for being part of a Manuscript Review Workshop hosted and funded on my behalf by the Religious Studies Program at OU under the leadership of Charles Kimball in 2016. This workshop was instrumental in helping me rethink the structure of this book and providing the necessary enthusiasm and momentum required to revise, complete, and submit the manuscript.

I received further financial support for the production of this book from the Religious Studies Program, College of Arts and Sciences, and the Office of the Vice President for Research at the University of Oklahoma. Thank you especially to Jen Waller, Scholarly Communication Coordinator at the University of Oklahoma, who assisted me in obtaining permissions for many of the figures in this work.

Many of the chapters of this book first emerged as conference papers. The co-panelists and colleagues whose questions and suggestions pushed me to refine my thinking are acknowledged in endnotes throughout this work, but let me thank here especially Emilia Bachrach, Pearl Barros, Varuni Bhatia, Joel Bordeaux, Richard Delacy, Namita Dharia, Joyce Flueckiger, George Gonzalez, Valarie Kaur, Max Mueller, Jenn Ortegren, Rowena Potts, Leela Prasad, Shil Sengupta, Tulasi Srinivas, Hamsa Stainton, Sarah Pierce Taylor, Joanne Waghorne, and Kirsten Wesselhoeft. Their fresh ideas and encouragement have provided immense intellectual sustenance over the years. Many thanks also to David Amponsah and his colleagues at the University of Missouri for inviting me to present my work as part of their Rufus Monroe & Sofie Hoegaard Paine Lecture Series and to Kristian Petersen, who publicized this research in an interview he included in the “Directions in the Study of Religion” series of Marginalia: Review of Books Podcast.

Thank you to Cynthia Read and Hannah Campeanu at Oxford University Press and the anonymous reviewers who provided detailed comments on my manuscript draft. They provided insights that made this book better than it otherwise would have been.

Last but certainly not least, I am grateful for the unfailing support and encouragement of my husband, David King. He has been by my side for the entirety of this project—in Kolkata while I was conducting research, and in Cambridge and Oklahoma City while I wrote this book. He is my thought partner, travel companion, and best friend. Without him, my creations would not be what they are.

NOTES ON TRANSLATION AND TRANSLITERATION

All translations are mine, unless otherwise noted. For the sake of consistency, both Sanskrit and Bengali words are italicized and transliterated according to the International Alphabet of Sanskrit Transliteration (IAST) conventions, unless I quote a text in which they appear differently. In many of the works employed throughout this book, various spellings are used for the same word. The English transliteration for the Bengali word for a temple proprietor, sevāyet (েসবােযত), for example, is not standardized in nineteenth- and twentieth-century texts. Thus, it appears variously as sevāyet, shevayet, shebait, and sebait when I quote such texts. Otherwise, I employ “sevāyet” according to the IAST convention for transliterating its standard Bengali spelling. Those words that have entered the English language are written according to the English convention (i.e., Brahmin).

Proper names are reproduced here in the way that individuals to whom I refer self-identify. If individuals Anglicize their names, I employ those Anglicized versions (i.e., Gaur Das Bysack). If they have authored works in Bengali, I use IAST conventions to transliterate their names into the Latin script (i.e., Sūrjyakumār Caṭṭopādhyāy). For Indian authors who are now known widely by Anglicized versions of their names, I employ the spelling by which they are known (i.e., Baṅkim Candra Caṭṭopādhyāy is written as Bankimcandra Chatterji, and Rabīndranāth Ṭhakur as Rabindranath Tagore).

Prior to 2001, the city of Kolkata was known as “Calcutta.” The village of “Kalikātā,” after which the city was named, was Anglicized as “Calcutta” under East India Company and then British colonial rule. Like many Indian cities (including Bangalore, which is now known as Bengaluru, and Bombay, now known as Mumbai), its name was changed to reflect the indigenous pronunciation of its original moniker. I follow the official name usage, employing “Calcutta” to refer to the city prior to 2001 and “Kolkata” to refer to the city after 2001.

Introduction

t he t emples of m odern Ind I a

India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal nehru, once anticipated a time when dams and power plants would become the temples of modern India.1 He was not alone in envisioning the nation’s future as one in which religion would take a back seat to industry. In the intervening decades, industries have indeed flourished, but temples have not receded from the forefront of public life. This is a book about what Hindu temples do for Hindus so that they have not been abandoned in moves to modernize India but have become an integral part of modernizing projects. For many among the middle classes in particular, religion’s public forms have been transformed over the past long century into emblems that declare proudly to the world who they are, where they come from, and where they are going. Counter to Nehru’s prediction, then, the temples of modern India are in fact temples.

Kālīghāṭ temple in Kolkata (formerly Calcutta)2 is an ideal site for a case study in the now widespread phenomenon by which India’s middle classes work to modernize temples. This temple, which is dedicated to the dark goddess Kālī, who accepts animal sacrifice, and is situated in a neighborhood inhabited by priests and sex workers, has been roundly critiqued by elites throughout its history for representing superstition and backwardness. This was especially true when Calcutta was the capital of the British Empire in India. Kālīghāṭ epitomized for colonialists, Orientalists, Christian missionaries, and Hindu reformers alike everything that was wrong with temple Hinduism. The most studied of Calcutta’s colonial middle classes3 the likes of Rammohan Roy, Rabindranath Tagore, and Vivekananda—ignored or denounced Kālīghāṭ. They worked to reform Hinduism by expunging it of places like Kālīghāṭ and the practices of image worship and animal sacrifice that accompanied them. This temple still represents backwardness for many

middle-class Hindus who decry its rituals as superstitious, its administration disorderly, and its physical state messy and chaotic.

Yet beginning in the late nineteenth century, Kālīghāṭ became the subject of major modernization projects undertaken by lesser-known middleclass Hindus in the city. Those Hindus wrote history books and journal articles that worked to rationalize Kālīghāṭ’s history and bourgeoisify its Hindu practices. In the mid-twentieth century, middle-class men filed and adjudicated lawsuits to make this once-private institution public and to secularize and democratize its management structure. They now form nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and file further lawsuits with the aim of gentrifying its physical space. For these individuals, Kālīghāṭ ought to represent Indian modernity, and they work hard to make it so. Their efforts mirror those at other temples across India from Chennai to Delhi to Bangalore.4

This temple remains important to these Hindus and others because the goddess within remains a potent force and a familiar figure in their lives. But it also remains important because the conceptual, institutional, and physical forms of this religious site are facets through which they can produce and publicize their modernity, as well as their city’s and their nation’s. In Kolkata, the distinctive black, oval form that Kālī takes at Kālīghāṭ (see Figure I.1)— with wide red eyes, a long golden tongue, and hands that hold a sword and

fI gure I.1 Murti of Kālī in the Inner Sanctum of Kālīghāṭ

source: Unattributed photograph purchased by author at stall near Kālīghāṭ.

severed head—adorns the walls of the most upscale houses to those of the most humble shops, and from the home screens of smartphones to the rearview mirrors of rickshaws. She literally permeates this city. Bengali Hindus— those living in the region of India that now spans the Indian state of West Bengal and the nation of Bangladesh—call her “Mā,” meaning “mother.” Kālīghāṭ is further thought to be one of the most potent of South Asia’s 51 Śaktipīṭhs (seats of the goddess) where pieces of the goddess’s body fell in a primordial age.5 It is visited by Kālī devotees from all over the world.

Since their earliest beginnings in the Indian landscape, temples have been sites where people have worked to publicly demonstrate their piety and social standing. Royal families built some of the most famous of India’s temples in the early medieval period. In constructing and renovating grand façades and patronizing opulent ritual performances, rulers legitimized their rule by demonstrating their economic prowess and their close relationship to the deities within.6 The wealthy landholders who built Kālīghāṭ in 1809, while not kings, surely demonstrated the same through that building.7 It is likely no coincidence that they initiated construction in 1799, the very same year that the East India Company’s governor general, Lord Wellesley, initiated the construction of Government House (now Raj Bhavan) just a few miles north. Devotees, too, have funded new archways, pillars, and other architectural features at this and other temples and have patronized their rituals and festivals, displaying to both Kālī and their peers their social status and devotion. Middle-class actors do the same when they work to modernize this temple.

Modernizing projects at Kālīghāṭ have three features that set them apart from pre-modern building and renovation projects. First, they deploy modernist idioms, including rationality, democracy, order, and cleanliness. These stand in stark contrast to idioms governing changes to temples in pre-modernity—purity, divine power, and the valor of aristocratic lineages. This novelty is one of substance rather than form, as people always work on sites that are important to them according to the values of their historical contexts. By definition, modern idioms were not available in pre-modern eras.

Second, and similarly, the notion of the Indian nation was not available in pre-modern eras. Beginning in the 1890s, alongside the early intimations of Indian nationalism, middle-class actors began to fashion Kālīghāṭ as a site that would represent the unique cultural heritage of Calcutta and India— first to colonial powers and, now, to the world. Middle-class actors felt that this temple could then become part of a project by which India would be perceived as modern but not Western.

Finally, and the most novel of the three transformations, is the role that is played by middle classes at the temple today. While sometimes espousing their subjugation to the divine power that temples house, middle-class actors also feel empowered to wield the worldly influence they have over those temples. Today, they join hands with state bodies to alter many aspects of temple life. In many ways, these men and women have taken on the role of those kings who once built grand temples and played an administrative role in them. Yet they are not kings. In fact, their class sensibilities would compel them to be troubled by the comparison. They see themselves instead as representatives of the public. They frame their modernizing efforts as “public interest” projects, self-evidently beneficial to everyone who visits the temple. An examination of opposition to their modernization projects reveals that the middle classes do not, in fact, represent the entire public. For many devotees, as well as temple Brahmins and members of the lower classes who make use of this site, Kālīghāṭ is not in need of transformation. Nor is it primarily valuable for its ability to represent their identity. Instead, it is a site of community, commerce, and worship, in which ties are forged between human and divine figures. Nevertheless, the middle classes do exert control over temples—at least at an official level—through the justification that they represent the public. This signifies a dramatic shift in the place of the temple in Indian society.

This argument will unfold throughout the pages of this book, but requires first an introduction to the specificities of Kālīghāṭ as well as the highly charged concepts of “modernity,” “the middle classes,” and “the public.” By way of introducing the temple and the kinds of significances it holds for individuals of many class backgrounds today, I offer a series of vignettes taken from my fieldwork in Kolkata in 2011 and 2012.

Following is a description of my visit to Kālīghāṭ one Saturday morning in October, 2011, with Kamala, a friend of my neighbor in the Tollygunge Phari neighborhood of Kolkata:

“This is a Śaktipīṭh, you know? It is a special place of the goddess. Long, long back, goddess Kālī’s little finger fell here in this spot. There are 58 places all over India where pieces of her body fell.”8

Kamala, an IT executive in her early forties, dressed in a crisply ironed, floral sari described to me the significance of Kālīghāṭ temple as we slowly approached it in her chauffeured, air-conditioned car. I had heard the Śaktipīṭh story many times before and would hear it many times again. The details

always differed—Was it one finger or a few? Was it fingers or toes? Was it Kālī’s body parts or Satī’s? Or are all goddesses really manifestations of the one goddess? Are there 58 places where her body fell, or 51, or 108? For devotees who visit Kālīghāṭ, the details of this story are not nearly as important as its truth— Kālī has been in that place “since time immemorial” and she is therefore immensely powerful there. She is more “jāgrata” (awake) at Kālīghāṭ than at any other temple. “There are many Kālī temples in Kolkata,” a professor of education once told me, “but if you want the real thing, you have to go to Kālīghāṭ.”

Devotees come from far and wide to visit this most famous Kālī temple in the world and what is held to be the most potent pilgrimage site in Bengal.

“We are all Kālī’s children,” Kamala continued. “Some people come to her for bad deeds and others come for good. But Kālī doesn’t discriminate.”

Kamala visits Kālī as often as she can. On this day, she had her twelfth-grade son in mind as she went to pray to this goddess known for her immense, undiscriminating power. According to her estimation, he had not studied nearly enough for his upcoming exams. “Typical teenager!” she quipped.

The car crept along the crowded Kali Temple Road, barely wide enough for one car to squeeze through. We were only a few hundred feet away, but it was hard to make out the temple façade as it is neither very large nor very grand and has many makeshift shop stalls attached to its walls (see Figure I.2). It was a Saturday morning—a day particularly auspicious for the goddess—so the crowds of devotees approaching the site swelled to the thousands. They were accompanied by hawkers selling everything from purses and bangles, to

fI gure I.2 Photo of Kālīghāṭ from Northeastern Corner source: Photo taken by Ankur P. in 2017.

ritual accoutrements including coconuts and garlands of prayer beads and of Kālī’s favorite red hibiscus flowers (see Figure I.3). As we came nearer to the temple itself, pictures and physical representations of Kālī and Śiva and other members of the Hindu pantheon were being sold (see Figure I.4). Devotees purchase these images of the gods and goddesses as mementoes of their visit and as mūrtis (embodiments of deities) to install in their home shrines.

The presence of the hawkers selling these products hid storefronts and restaurants (called “hotels”) selling hot, milky chai alongside jalebi and gulab jamun—some of the sweets for which Bengal is best known. Beggars filled in the spaces between hawkers and devotees, some knocking on our window, hoping to be the beneficiaries of our generosity. Many were aged and crippled. Most were women. Pāṇḍās (male Brahmin ritual officiates and temple guides) young and old lingered, offering assistance to guide pilgrims through the temple. One pāṇḍā nodded at me, knowingly. Having visited the temple regularly for about a month before this visit with Kamala, I had come to know a few of the hundreds of pāṇḍās and beggars who work on temple grounds. I had walked along Kali Temple Road many times and knew that it would have taken us 5 minutes to walk the few blocks it took us almost 20 minutes to drive. Apart from the crowds slowing us down, much of the road in front of the temple was closed off, so that our route was circuitous. Kamala was my neighbor’s

fI gure I.4 A Hawker’s Stall in Front of the Temple source: Photo taken by author in 2009.

friend who, upon hearing that I was interested in this famed Hindu temple, offered to bring me along next time she went to visit. “I never go to Kālīghāṭ because of the pāṇḍā problem” my neighbor had remarked, offhandedly, when we first met. She complained that pāṇḍās harassed her every time she visited the temple, demanding exorbitantly large “tips.” Kamala complained instead of the huge crowds at the temple—“too much to manage”—she explained. Neither of these women visited Kālīghāṭ unless they had arranged to visit with a man named Jaidev—a “good pāṇḍā” in their words—who could be trusted to help them navigate the crowds and to conduct pūjā (worship) in the correct ways, without extorting money from them. Kamala’s husband is an orthopedic surgeon at a nearby hospital. His division sponsors this pāṇḍā so that all surgeons and their families can visit Kālīghāṭ with his assistance. This does not provide the completely “hassle-free” visit Kamala longs for, but it helps.

We turned left on Kālīghāṭ Road in order to reach our meeting place with Jaidev (for a map of this neighborhood and its location within Kolkata, see Figures I.5 and I.6). Priests from Kālīghāṭ live on the eastern side of this road, while sex workers live on the western side in an old but still operative red light district. This is the road on which Mamata Banerjee, chief minister of West Bengal, would approach the temple from her home, just a mile north. Having grown up in this neighborhood, “didi,” (elder sister) as she is known,

fI gure I.5 Map of Kolkata source: Gai Moodie, illustrator (not to scale).

touts her humble origins as evidence of her being one with the people. Kamala pointed out Jaidev as we passed by Mother Teresa’s Home for the Sick and Dying (Nirmal Hriday) on our left. The building in which it is housed was formerly a resting house for pilgrims visiting Kālīghāṭ. In 1952, the city gave it to the famed nun to pursue her work of providing care for the dying. Nuns and mostly foreign volunteers fed and bathed those nearing the end of their lives. That work was on pause during the year of my fieldwork as the building was under internal construction.

Jaidev held the car door open for us as we slid off our cool leather seats into the thick, humid air. He wore a white dhoti (traditional male garment consisting of a floor-length cloth that is wrapped around the waist). His sacred thread indicating his Brahmin caste identity was visible through his short-sleeved, collared shirt’s opened buttons. He handed Kamala a basket with a coconut, some red bangles, and a small piece of red and gold sari cloth. He poured water from a copper bowl into our hands so that we could purify ourselves before entering the temple grounds. We passed through the small lane in between Nirmal Hriday and the temple, which was flanked by more shop stalls.

fI gure I.6 Map of the Kālīghāt Neighborhood source: Gai Moodie, illustrator (not to scale).

We sat on a bench outside a sweet shop adjoined to the temple for a few minutes while Jaidev’s assistant selected pieces of miṣṭi (sweets) to add to the basket. These would become part of Kamala’s offerings to the goddess. The smell of butchered goat meat wafted into the shop area. We were very near where goats are taken after they are sacrificed. While animal sacrifice has ceased in almost every other temple in the city, it continues here on a daily basis. Part of the first goat sacrificed to Kālī each day becomes part of her midday meal. The rest of the goat meat is either taken by the family who offered it or sold in a small meat market in the corner of the temple. This sanctified flesh is cooked and eaten as prasād (blessed food). There is a great deal of ambivalence surrounding this practice. One priest had previously assured me that Kālī does not eat the meat—her “bhūt (ghostly attendants)” do. Most who offer sacrifices disagree. Noticing the smell, Kamala smiled politely and stated: “Some people offer animal sacrifice here. I have a different opinion about that, but jay hok (let it be)!” She performs what Jaidev calls “Vedic”—rather than “Tantric”—pūjā, meaning that she and her family sacrifice gourds as a substitute for goats.

We left our shoes at the sweet shop and entered the temple (see Figure I.7 for a plan of the temple). There was a long, winding queue of devotees waiting