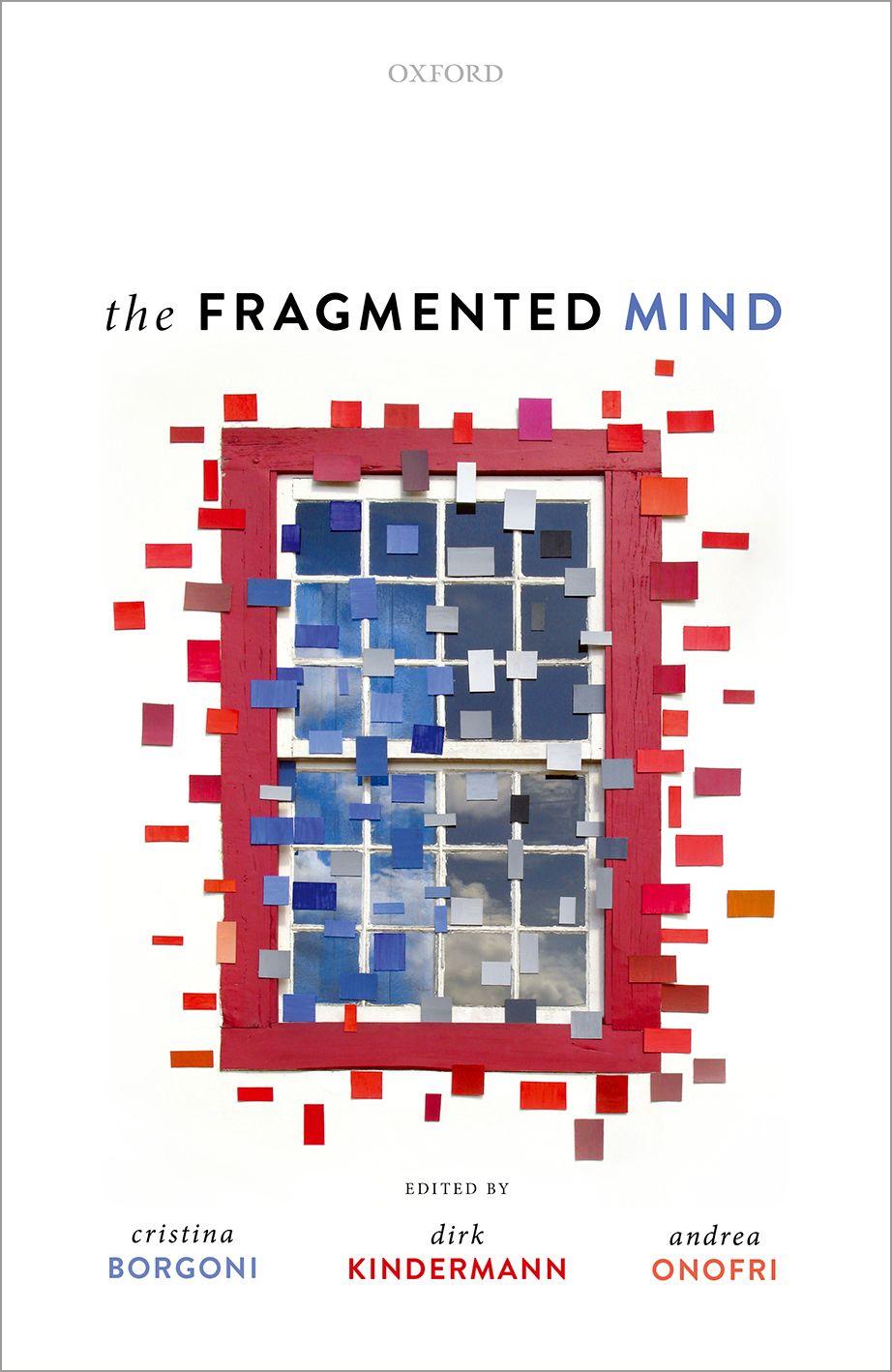

TheFragmentedMind:AnIntroduction

DirkKindermannandAndreaOnofri

Thisbookisaboutthehypothesisthatthemindisfragmented,orcompartmentalized. Whenitissaidthatanagent’smindisfragmented,itisusuallymeantthat theiroverallbeliefstateisfragmented.¹Toa fi rstapproximation,abeliefstate canbesaidtobefragmentedifitisdividedintoseveralsub-statesofthesame kind:fragments.Eachfragmentisconsistentandclosedunderentailment, butthefragmentstakentogetherneednotmakeforaconsistentandclosed overallstate.Thethesisthatthemindisfragmentedcontrastswiththewidespread,ifoftenimplicit,assumption callit Unity thatthemindisuni fi ed, i.e.thatanagent’ soverallbeliefstateisconsistentandclosedunderentailment. Themotivationforfragmentationcomesfromanumberofplaces,notablythe shortcomingsof Unity:theproblemoflogicalomniscience,theproblemof inconsistentdoxasticstates,casesofcognitivedissonanceandimperfectinformationaccess,andothers.InthisIntroduction,weoutlinewhatvarietiesof fragmentationhaveincommonandwhatmotivatesthem.Wethendiscussthe relationshipbetweenfragmentationandthesesaboutcognitivearchitecture, introducetwoclassicaltheoriesoffra gmentation,andsketchrecentdevelopments.Finally,asanoverviewofthevolume,wepresentsomeoftheopen questionsaboutandissueswithfragme ntationthatthecontributionstothis volumeaddress.

1.UnityandFragmentation

Doxasticstateslikebeliefandepistemicstateslikeknowledgearestandardly assumedtobeinherentlyrational.Muchofepistemiclogic,Bayesianaccountsof humanbelief,decisiontheory,andsomein fl uentialviewsaboutrationality proceedfromtheunderlyingviewthatthemind oratleastdoxasticstates isuni fi ed: ¹Thisformulationfocusesonbelief,sincethishasbeenthemainfocusoftheliteratureonthetopic. Wemeantoleaveopenthepossibilitythatafragmentedmindisoneinwhichoverallattitudestateslike knowledgeordesireare(also)fragmented.

DirkKindermannandAndreaOnofri, TheFragmentedMind:AnIntroduction In: TheFragmentedMind.Editedby:Cristina Borgoni,DirkKindermann,andAndreaOnofri,OxfordUniversityPress.©DirkKindermannandAndreaOnofri2021. DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198850670.003.0001

Agentshaveaunifiedrepresentationoftheworld(attime t) asinglestateof belieforganizedbytwoprinciples:

1. Consistency:Thetotalsetofanagent’sbeliefs(at t)isconsistent.

2. Closure:Thetotalsetofanagent’sbeliefs(at t)islogicallyclosed.Thatis, agentsbelievethelogicalconsequencesoftheirbeliefs.²

Unity mayseemtoimposeunreasonablystrongrequirementsondoxasticstates. Intheliterature, Unity aswecallit isoftenendorsedwithoneofthefollowing qualifications.

First, Unity isoftenthoughtofaspartofadescriptivetheoryof ideal rational agents,notofrealagents.Thus,someauthorsimplicitlyorexplicitlytaketheir analysestodescribesuitablyidealizedversionsofrealagents.³Idealizationaffords manytheoreticaladvantages,includingsimplicityinaccountingforlogicalrelationsamongbeliefs.Noneofthisentailsthatthetheoryappliesdirectlytoreal agents.Anopenquestionhereisofcoursewhetherrealagentsaresimilarenough totheseidealizedagentsforthetheorytohaveanyuseintheexplanationofreal agents’ doxasticattitudes(see ‘IdealizationandExplanatoryPower’ below).

Second,the Consistency and/or Closure principlesaresometimesweakened.For instance,EaswaranandFitelson(2015)propose ‘non-dominance’ foran(ideally rational)agent’soverallbeliefs,acoherencerequirementthatisstrictlyweaker than Consistency. ⁴ Closure issometimesweakenedtoapplyonlytologicalconsequencesthatwouldbe ‘manifest toanidealcognizer’ (Fine2007:48;ouritalics)or toconsequencestheagentalso believes tobeconsequencesofherbeliefs.Despite varianceintheprinciples,mostauthorsassumethattheyapplytoanagent’ssingle overallbeliefstate.

Third, Consistency and Closure aresometimesunderstoodas rationalityconditions onbelief.Theyaremeanttobepartofanormativeaccountofhowreal agents should behaveintheirdoxasticlivestocountasrational.⁵ Itissometimes notentirelyclearwhetheragivenanalysisofbeliefisproposedasa descriptive

²Tobeinclusive,we’llkeepthenotionsofconsistencyandclosurequitegeneral.Asetoffullbeliefs thuscountsasconsistentjustincaseitcontainsnotwobeliefswhosecontentscannotbetruetogether. Wewill,forthemostpart,talkaboutfullbelief;whereagradednotionofbeliefisrelevant,consistency isunderstoodasfollows:asetofgradedbeliefsisprobabilisticallyconsistent iff itobeysthelawsof probability.Abeliefcountsasalogicalconsequenceofasetofbeliefsincaseitfollowsfromthesetby thelawsoflogic.

³Stalnaker(1991)givesausefuloverviewoftheroleofidealizationintheoriesofbelief.SeeGriffith etal.(2012)onrationalityasamethodologicalassumptioninthedescriptiveanalysisofhumanbelief.

⁴ Others,however,assumeanotionofcoherencethatisstrongerthan Consistency:traditional coherencetheoristsinepistemologyrequire(rationalorjustified)beliefstobelogicallyconsistent and mutuallyinferable and tostandinvariousexplanatoryrelationstoeachother(see,e.g.,BonJour1988).

⁵ See,forinstance,Kolodny(2008)fordiscussionofdescriptivevs.normativeversionsof Consistency and Closure.

accountofrealagentsorasa normative accountofwhatanagent’srationalbeliefs shouldbelike.Butevenwhenanormativeorheavilyidealizedaccountisassumed, mostauthorsinphilosophy,formalepistemology,anddecisiontheorypresuppose thatagentshaveasinglebeliefstate.

Becauseofitstheoreticalvirtues, Unity iswidelyadoptedinseveraldifferent areas.First,inBayesianepistemology,indoxasticandepistemiclogic,andin decisiontheory, Unity allowsformuchsimplerformalmodelsofhumanthought andagency.Thus,givingupon Consistency or Closure comesatthecostofgiving upclassicallogicalassumptionsthatunderliemuchofBayesianprobabilitytheory anddecisiontheoryandwouldrequiretheadoptionofweaker,non-normal doxasticandepistemiclogics.⁶

Second,inphilosophy,mostauthorsaccept Consistency asaminimalrequirementonrationalbelief(seeEaswaranandFitelson2015).Kolodny’s(2008)useof theterm ‘themythofformalcoherence’ forapackageofprinciplesincluding Consistency and Closure bespeakstheirpervasivenessinthediscipline.⁷ Formany authors,partofwhatitistobeabeliefistotendtoproducebeliefsinwhatfollows fromthebeliefinquestionandtotendtoeliminateinconsistencies.⁸ Forinstance, theDavidsoniantraditionholdsthat,inordertointerpretotherpeopleinlinguistic communication,wemustpresupposethattheirbeliefsareconsistenttoasufficient degree.⁹ AndDennett(1981)explicitlyclaimsthat,whenattributingintentional statestoothersinordertoexplaintheirbehavior,our ‘starting’ assumptionisthat theirbeliefsareconsistentanddeductivelyclosed wethenrevisethatassumption onthebasisofthespecificcircumstancesoftheagentwearedealingwith.

Indeed,theassumptionsof Consistency and Closure arereflectedinoureveryday,commonsenseattributionsofbelief.Weusuallyexpectotheragentstoexhibit relevantreasoningpatternsonthebasisoftheirbeliefs,drawingvariouskindsof inferencesbothconsciouslyandunconsciously.Wealsoexpectthat,uponreceivingnewinformationthatcontradictstheirpreviouslyheldbeliefs,theywillusually updatetheirdoxasticstateaccordingly,insteadofsimplyacceptingblatantly inconsistentpropositions.Everydaybeliefattributionsthusmanifestbothan assumptionthatpeople’sbeliefsareconsistentanddeductivelyclosedandan expectationthatpeople ’sbeliefsshouldexhibitthesetwoproperties.

Finally, Unity’splausibilitystemsinpartfromtheideathatthepointofbelief istorepresenttheworldaccurately,withoutmissingimportantbits.¹⁰ Butour

⁶ See,e.g.,Christensen(2004:ch.2)fordiscussionofthefoundationsofprobabilisticanalysesof beliefinclassicaldeductivelogic.SeeKaplan(1996)foradefenseof Consistency and Closure atthe heartofdecisiontheory.

⁷ Amongthemostoutspokensupportersof Consistency arecoherencetheoristsofepistemic justification(e.g.BonJour1988).Forrecentattackson Consistency whichnonethelesspresumethat agentshaveasingletotalsetofbeliefs,seeKolodny(2007,2008)andChristensen(2004).

⁸ See,forinstance,Bratman(1987),whoholdsthisviewforotherattitudes,suchasintentions.

⁹ SeeDavidson(1973,1982/2004).

¹⁰ See,e.g.,vanFraassen(1995:349).

beliefs,sothislineofthoughtgoes,cannotrepresentaccuratelyandcomprehensivelyiftheyareinconsistentandtheirconsequencesarenotdrawn.¹¹Insum, accordingtothisviewofbelief,

beliefs...necessarily,orconstitutively,tendtoformalcoherenceassuch(evenif thistendencyissometimesinhibited).Partofwhatitistobeabelief,manyinthe philosophyofmindwillsay,istotendtoproducebeliefsinwhatfollows...And partofwhatitistobeabeliefistotendeithertorepelcontradictorybeliefs,orto givewaytothem,assuch.(Kolodny2008:438)

Despite Unity’sattractivefeatures,applying Consistency and Closure toanagent’ s globaldoxasticstatealsogeneratesseriousproblems,whichwewilldiscussin Section2.Fragmentationviewswereoriginallyproposedtoavoidsuchproblems whilekeepingwiththeideathat,locally, Consistency and Closure areimportant ingredientsofwhatitistobeinadoxasticstatesuchasbelief.DaviesandEgan providethefollowingsummaryofwhatitisforanagenttobeinafragmented beliefstate:

Actualbeliefsystemsarefragmentedorcompartmentalised.Individualfragmentsareconsistentandcoherentbutfragmentsarenotconsistentorcoherent witheachotheranddifferentfragmentsguideactionindifferentcontexts.We holdinconsistentbeliefsandactinsomecontextsonthebasisofthebeliefthat Pandinothercontextsonthebasisofthebeliefthatnot-P.Frequentlywefailto putthingstogetherorto ‘joinupthedots.’ Itcanhappenthatsomeactionsare guidedbyabeliefthatPandotheractionsareguidedbyabeliefthatifPthenQ, butnoactionsareguidedbyabeliefthatQbecausethebeliefthatPandthebelief thatifPthenQareinseparatefragments.(DaviesandEgan2013:705)

Atahighlevelofabstraction,thehypothesisoffragmentation,orcompartmentalization,consistsoffourclaims:

Fragmentation

F1.Thetotalsetofanagent’sbeliefs(attime t)isfragmentedintoseparatebelief states.

F2.Eachbeliefstate(at t)isafragmentwhoseconstituentbeliefsareconsistent witheachotherandclosedunderlogicalconsequence.

¹¹Theargumentcanbefound,e.g.,inLehrer(1974:203).Christensen(2004:ch.4)givesahelpful summaryofargumentsfor Consistency.

F3.Thebeliefstatesofasingleagent(at t)arelogicallyindependent:Theymay notbeconsistentwitheachother,andtheagentmaynotbelievetheconsequencesofhisbelieffragmentstakentogether.

F4.Differentbelieffragmentsofasingleagent(at t)guidetheagent’sactionsin differentcontextsorsituations.

Fragmentationseesanagent’soverallbeliefstateasfragmentedintovarioussubstates,eachofwhichis ‘active’ or ‘available’ forguidingactioninaspecificcontext. Whileeachsinglesub-state,orfragment,isconsistentandclosedunderlogical consequence,anagentmayhaveaninconsistentoverallbeliefstateonaccountof inconsistentbeliefsbelongingtodifferentfragments;thatis,inconsistentbeliefs thatare ‘active’ indifferentcontexts.Furthermore,theagentmayfailtodrawthe logicalconsequencesofbeliefsbelongingtodifferentfragments.(Notethattheses F1–F4donotentailthatasinglebeliefmustbelongtoonlyonefragment;infact, many(basic)beliefswillbelongtomostfragmentsiftheyareaction-guidingin manycontexts.)Inwhatfollows,wetreatviewsthatendorsefragmentationas minimallycommittedtoclaimsF1–F4(orsimilarversionsthereof).

2.MotivationsforFragmentation

2.1.LogicalOmniscienceandClosure

Someofthemotivationfor Fragmentation stemsfromthenotoriousshortcomingsof Unity.Forinstance, Unity’ s Closure principlefacesaversionoftheproblem oflogicalomniscience.¹²Let’sconsiderthefollowing,single-premiselogicalclosureprinciple:

Single-premiseclosure

Foranypropositions p and q,ifanagent A believes p,and p logicallyentails q,it followsthat A alsobelieves q.

Agentsautomaticallybelieveallofthelogicalconsequencesofanyoftheirbeliefs. Itisobviousthataviewendorsing Closure isnotdescriptivelyadequateforagents with finitelogicalabilities(Parikh1987,1995);itimpliesthathumanshaveno needforlogicalreasoning,astheyalreadyknowallthelogicalconsequencesofany

¹²Theproblemoflogicalomniscienceisoftenassociatedwithpossibleworldsmodelsofattitude content.Note,however,thatanyviewonwhich Closure isendorsedwillfacetheproblem,nomatter whatmodelofattitudecontentisadopted(cf.Stalnaker1991andGreco,Chapter3inthisvolume).

oftheirbeliefs.ButasHarmanhasfamouslyargued,endorsing Closure isnot normativelyadequateeither:Rationalagentswith ‘limitedstoragecapacity’ should notstrivetodrawanyandalllogicalconsequencesfromthebeliefstheyhold,or elsetheir finitemindswillbecome ‘cluttered ’ withtrivialbeliefsthatareirrelevant totheirlives(Harman1986:13).

Onewayforatheoryofbelieftoavoidtheproblemoflogicalomniscienceis simplybydroppinganylogicalconstraintsontheoverallsetofanagent’sbeliefs. Butasmanyhaveargued,abeliefsetmustmeetsomeminimallogicalstandardsin ordertocountasabeliefsetatall.Thus,Cherniakwrites,

[t]heelementsofamind and,inparticular,acognitivesystem must fit together orcohere.Acollectionofmynahbirdutterancesorsnippetsofthe NewYorkTimes arechaos,andso(atmost)justasentenceset,notabeliefset.... norationality,noagent.(Cherniak1986:6)

Theproblemoflogicalomniscienceisthusbutonesideoftheproblemof finding the ‘right’ consequencerelation(orevenmorebroadly,the ‘right’ logicalprinciples)underwhichthebeliefsetsofrealagentsareclosed(cf.Stalnaker1991).

Fragmentationviewsofbeliefpromisetomake some progressonthislarger problembyavoidingthecounterintuitiveresultsofmultiple-premiseclosure:

Multiple-premiseclosure

Foranypropositions{p, q,... r},ifanagent A believes p and A believes q ...and {p, q,...} togetherentail r,then A believes r.

Versionsofthefragmentationapproachdenythatmultiple-premiseclosureholds fortheentirebeliefstate;thatis,acrossfragments.Soifthebeliefthat p andthe beliefthat q belongtodifferentfragments,theagentneednotcountasbelieving anylogicalconsequenceof p and q takentogether.Inaddition,fragmentation viewsallowustocountsuchagentsasrational,althoughthereisalargelyopen questionastowhataminimalthresholdforrationalbeliefacrossfragmentsmight beonfragmentationviews(cf.Cherniak1986andBorgoni,Chapter5inthis volume).Atthesametime,fragmentationviewsdoimposeminimalconstraints onbeliefsets,orstates,byacceptingversionsof Consistency and Closure forthe individualfragments.Thus,beliefsare ‘locally’ consistentandcomplete,butnot acrossfragments.¹³

¹³Itisstillpartoffragmentationviewsthatsingle-premiseclosureholdswithineverysingle fragment,andthustheystillfacetheproblemfromsingle-premiseclosure.SeeYalcin(2008,2018) foranattempttomakeprogressonthesingle-premiseclosureproblemforfragmentationviews cf. Section4.3ofthisIntroductionformoredetails.Rayo(2013)addressestheproblemofmathematical andlogicalomniscienceonapossibleworldsconceptionofcontent.

Aparallelproblemarisesfor Unity’ s Consistency principle:Itseemsclearthat agentssometimesholdinconsistentbeliefs.Lewis(1982:436)providesafamous example:

IusedtothinkthatNassauStreetranroughlyeast–west;thattherailroadnearby ranroughlynorth–south;andthatthetwowereroughlyparallel.(By ‘roughly’ Imean ‘towithin20degrees.’)

Lewis’sthreebeliefsweremanifestlyinconsistent.However,accordingtothe Consistency principlethatispartof Unity,agentsdonotholdinconsistentbeliefs.

Lewis’sexamplethusseemstopresentaproblemfor Unity. Wemightbetemptedtosimplydismiss Consistency asbeingimplausiblystrong andclearlyinadequate.Asnotedintheprevioussection,however,thiskindof moveisnotenoughtosolvetheproblemfacedby Unity.Wewouldnotbeinclined toconsideralargecollectionofcompletelyinconsistentbeliefsanagent’sdoxastic state,soifweabandon Consistency,wewillneedanalternativeprinciple:an agent’sbeliefsmightoccasionallybeinconsistent,asinLewis’scase,butthey cannotbesystematicallyinconsistentwhilestillcountingasacognitivesystem.So whatprincipleshouldweadoptwhendealingwiththepossibilityofinconsistent beliefs?

Again, Fragmentation canbeusedtoofferananswertothisquestion. Immediatelyaftersketchingtheabovecase,Lewishimselfprovidesabriefbut influentialformulationofthefragmentationapproach:

Now,whatabouttheblatantlyinconsistentconjunctionofthethreesentences?

Isaythatitwasnottrueaccordingtomybeliefs.Mysystemofbeliefswasbroken into(overlapping)fragments.Differentfragmentscameintoactionindifferent situations,andthewholesystemofbeliefsnevermanifesteditselfallatonce.The firstandsecondsentencesintheinconsistenttriplebelongedto weretrue accordingto differentfragments;thethirdbelongedtoboth.Theinconsistent conjunctionofallthreedidnotbelongto,wasinnowayimpliedby,andwasnot trueaccordingto,anyonefragment.Thatiswhyitwasnottrueaccordingtomy systemofbeliefstakenasawhole.Oncethefragmentationwashealed,straightwaymybeliefschanged:nowIthinkthatNassauStreetandtherailroadbothrun roughlynortheast–southwest.(Lewis1982:436)

Lewis’ssystemofbeliefsconsistsof(is ‘brokeninto’)differentfragments,noneof whichincludestheinconsistentconjunctionofallthreebeliefs.Therefore,each fragmentrespectsconsistencyrequirements theinconsistencywouldonlyarise inafragmentthatincludedallthreebeliefs,butthereisnosuchfragmentin

Lewis’soveralldoxasticstate.Withinafragmentationapproach,then,individual fragmentsareinternallyconsistent,butinconsistencymaystillariseamongbeliefs belongingtodifferentfragments(asinLewis’scase).¹⁴

2.3.IdealizationandExplanatoryPower

Inbelief–desirepsychology,doxasticstatesareassumedto figureinpsychological lawsthatexplainandpredicttheactionsofrationalagents,suchas ‘[I]fAwantsp andbelievesthatdoingqwillbringaboutp,thenceterisparibus,Awilldoq’ (Borg 2007:6).¹ ⁵ Arguably,suchlawsmakeuseofoureverydaynotionsofbeliefand desire,ifnotofscientificallyrespectableones.Theendorsementofthisroleof beliefintheexplanationandpredictionofaction,however,presentsadifficultyfor viewsthat(eventacitly)endorse Unity Unity isdescriptivelyinaccurate; finite agentsarenotalwaysconsistentintheirbeliefsanddonotdraweachandevery deductiveinferencefromthem.Asaresult,theassumptionsof Consistency and Closure typicallyinvolvetheidealizationofagents’ rationalcapacities.While idealizationisacommonandusefulelementofscientifictheorizing,theassumptionofidealrationality exempli fiedin Consistency and Closure seemstobeso extremethatitcannotbeappliedininterestingwaystorealagentswith finite computationalcapacitiesandlimitedmemory.Inparticular,idealrationality appearstoleavethosetheorieswithoutanyabilitytoexplainorpredicttheactions ofrealagentsatall.¹⁶ Cherniak(1986)usesthefollowingstorytomakehiscase againsttheassumptionofagentswithidealizedrationalcapacities:

In ‘AScandalinBohemia’ SherlockHolmes’sopponenthashiddenavery importantphotographinaroom,andHolmeswantsto findoutwhereitis. HolmeshasWatsonthrowasmokebombintotheroomandyell ‘Fire!’ when Holmes’sopponentisinthenextroom,whileHolmeswatches.Then,asonewould expect,theopponentrunsintotheroomandtakesthephotographfromitshiding place....oncetheconditionsaredescribed,itseemsveryeasytopredictthe opponent’sactions.Primafacie,wepredicttheactions...byassumingthatthe opponentpossessesalargesetofbeliefsanddesires includingthedesireto preservethephotograph,andthebeliefthatwherethere’ssmokethere’ s fire,the

¹⁴ FordiscussionofLewis’scase,seeforinstancethecontributionstothisvolumebyBorgoni,Egan, Greco,andYalcin.

¹⁵ Cf.Davidson(1963,2004).

¹⁶ WeareadaptingCherniak’sargumentagainstwhathecallsthe ‘idealgeneralrationalitycondition’ (‘IfAhasaparticularbelief–desireset,Awouldundertake all andonlyactionsthatareapparently appropriate’ (Cherniak1986:7)).SeealsoStalnaker(1991)forargumentsforwhythestandardreasons foridealizingdonotapplytotheidealizationsunderlying Consistency and Closure.

beliefthat firewilldestroythephotograph,andsoon andthattheopponentwill actappropriatelyforthosebeliefsanddesires.(Cherniak1986:3–4)

Againsttheoriesofbeliefthatassumetheidealizedrationalityofbelief,desire,and theirconnectiontoaction,Cherniakarguesthat

withonlysuchatheory,Holmescouldnothavepredictedhisinevitablysuboptimalopponent’sbehavioronthebasisofanattributionofabelief–desireset; hecouldnothaveexpectedthatherperformancewouldfallshortofrational perfectioninanyway,muchlessinany particular ways.Holmeswouldhaveto regardhisopponentasnothavingacognitivesystem.(Cherniak1986:7)

Theidealizationsinvolvedin Unity,then,makethetheoryvirtuallyinapplicableto agents ‘inthe finitarypredicament’ (Cherniak1986:8).Sincewe,likeHolmes,do havewaysofexplainingandpredictingagents’ specificbehaviorbasedonattributionsofbeliefsanddesires,nosuchtheorycanbetrueofournotionofbelief. Putdifferently,ifwewantatheoryofbeliefthatallowsfortheexplanationandthe predictionoftheactionsofrealagents,we’dbetterletgooftheextremeidealizationsinvolvedin Unity

Atthesametime,wesawintheprevioussectionsthatwecannotletgoofall rationalityconstraintsonthenotionofbeliefeither.Ifourtheoryallowedfor agents’ overallbeliefstatestoberandomsetsofbeliefswithoutanyrestrictions,it isnotclearthatwe’dhaveatheoryofthebeliefsof agents. Cherniakconcludesthat weneedtosteeramiddlepathbetweenidealizedrationalityconditionsandno rationalityconditions whathecalls minimalrationality .Fragmentationviews fit minimalrationalityconstraints:agentsdonotmaintainconsistencyorlogical closureacrosstheirentirebeliefset,orstate,andneitherdotheyneedtoinorder tocountasminimallyrational.Fragmentationviewsallowforinconsistencyand closurefailureacrossfragments.Butagentsdo(needto)keeptheirbeliefslocally consistentandlogicallyclosed.Fragmentationviewsdoplaceconsistencyand closurerequirementsoneachindividualfragment.

2.4.MemoryandInformationAccess

Anothermotivationinfavoroffragmentationstartswiththeobservationthata pieceofinformationwepossess(inmemory)maybeaccessibletousgivenone purposeortaskbutmaynotbeaccessiblegivenanotherpurposeortask.Consider thefollowingexampleofferedbyStalnaker:

[I]twilltakeyoumuchlongertoanswerthequestion, ‘Whataretheprime factorsof1591?’,thanitwillthequestion, ‘Isitthecasethat43and37arethe

primefactorsof1591?’ Buttheanswerstothetwoquestionshavethesame content,evenonavery fine-grainednotionofcontent.Supposethatwe fixthe thresholdofaccessibilitysothattheinformationthat43and37aretheprime factorsof1591isaccessibleinresponsetothesecondquestion,butnotaccessible inresponsetothe first.Doyouknowwhattheprimefactorsof1591areornot? (Stalnaker1991:438)

ThelessmathematicallyinclinedamongusareperhapsjustasStalnakerdescribes: theinformationthat 43and37aretheprimefactorsof1591 isaccessibletousfor thetaskofansweringtheyesornoquestion,butitisnotaccessibleforthetaskof answeringthe wh-question.¹ ⁷ Stalnaker(1991,1999)arguesthatanotionof accessiblebelief(relativetoapurpose)isnecessaryinexplanationsofactionin termsofbeliefanddesire.Someofanagent’sactionsarebestpredictedor explainedbyattributingabelief p tothem(giventheirdesires),whileotheractions performedbythesameagentinthesamesituationcanonlybepredictedor explainedwhen p isnotamongtheirbeliefs(giventhesamedesires).Thenotion ofanaccessible,oravailable,beliefcanbenaturallyaccommodatedbythe fragmentationapproach.Forinstance,variableinformationaccess(inmemory) maybeduetotheneedforanefficientrecallmechanismthatsearchesonlythose partsofmemorythatarerelatedtothepurposeathand(Cherniak1986:ch.3). Thisassumptionsitsnaturallywiththeviewaccordingtowhichourinformation (inmemory)isorganizedintofragments,whichinturnareassociatedwith particularpurposes,ortasks.

2.5.ThePrefaceParadox

Next,fragmentationmayallowforanintuitivesolutiontotheprefaceparadox.It isrationalforabook’sauthortobelieveallthestatementstheymakeinthebook. Atthesametime,itisrationalforthemtoadmittheirfallibility;thatis,tostate F: thatatleastoneofthesebeliefsisfalse.Thus,itwouldberationalforthemtohave inconsistentbeliefs:asetofbeliefs and thebeliefthatatleastoneofthemisfalse.

Onfragmentationviews,Cherniakargues,itmayindeedbe(minimally) rationaltohaveinconsistentbeliefsingenuineprefaceparadoxcases:

Theseeminglyoverlookedpointthatisofinteresthereisthatthe size ofthe beliefsetforwhichapersonmakesthestatementoferror F determinesthe reasonabilityofhisjointassertions.Ifhesays, ‘Somesentencein{p}isfalse,and

¹⁷ ElgaandRayo(Chapter1inthisvolume)andRayo(2013)provideanumberoffurtherexamples thatsupporttheclaimthatinformationisaccessibletousrelativetovariouspurposes,ortasks.Seealso Greco(2019)fortheclaimthatanagent’sknowledgeandevidenceareavailableonlyrelativeto particularpurposes.

p, ’ thisseemsclearlyirrational,likesaying, ‘Iaminconsistent;Ibelieveboth p and not-p.’ Ifhesays, ‘Somesentencein{p, q}isfalse,and p,and q, ’ thisissimilarly unacceptable.Butifthesetisverylarge,andinparticularencompassesthe person ’stotalbeliefset,thenaccepting F alongwiththatbeliefsetbecomes muchmorereasonable.(Cherniak1986:51)

Withinasinglefragment,someversionof Closure holdsfromwhichtheprinciple of Agglomeration followsforbeliefs p and q inthesamefragment:(B(p)& B(q)) ! B(p & q),where B isthebeliefoperator.Taking Closure asaconstraintonrational belief,afragmentationtheoristmayholdthatitisirrationaltoaddtoafragmenta belief F inone’sfallibilitywithregardtothebeliefsinthatfragment.Otherwise, therewouldbeaninconsistentfragment.Butforlargersetsofbeliefsincluding p, q, r, thatbelongtodifferentfragments,itisnotirrationaltoaddtoone’ssetof beliefsthebelief F thatatleastoneof p, q, r, ... isfalse.Noclosureconditionholds acrossfragments,so Agglomeration doesn’tholdeitherforbeliefs p, q, r, and F, andnoinconsistentconjunctionneedbederived.¹⁸

2.6.CognitiveDissonanceandImplicitBias

Casesof ‘cognitivedissonance’ and ‘implicitbias’ seemtoprovidefurthersupport forfragmentation.Beforewemovetothecases,itwillbehelpfultoofferageneral characterizationofthesetworelatedphenomena,startingwithcognitivedissonance.Aronson(1997)describescognitivedissonanceasfollows,ashesummarizes themainideasbehindFestinger’sclassicworkonthetopic:

Ifapersonholdstwocognitionsthatarepsychologicallyinconsistent,heexperiences dissonance:anegativedrivestate(notunlikehungerorthirst).Becausethe experienceofdissonanceisunpleasant,thepersonwillstrivetoreduceit usuallybyst[r]ugglingto findawaytochangeoneorbothcognitionstomake themmoreconsonantwithoneanother.(Aronson1997:128)

Asanexampleoftwodissonantpsychologicalstates,considerthefollowingcase byGendler:

Lastmonth,whenIwastravelingtotheAPAProgramCommitteemeeting, Iaccidentallyleftmywalletathome....whenIgottoBaltimore,Iarrangedto

¹⁸ Stalnaker’sfragmentationapproachtotheprefaceparadoxissomewhatdifferentfromCherniak’ s positionabove.WhileStalnaker(1984:ch.5)agreesthat Agglomeration shouldbegivenupasaglobal, i.e.inter-fragment,normativeidealofrationalityfortheattitudeof ‘acceptance,’ heupholds Agglomeration,togetherwith Consistency,asaglobalnormativeidealofrationalityfortheattitudeof belief.

borrowmoneyfromafriendwhowasalsoattendingthemeeting.Ashehanded methebills,Isaid: ‘Thankssomuchforhelpingmeoutlikethis.Itisreally importantformetohavethismuchcashsinceIdon’thavemywallet.’ Rooting throughmybagasItalked,Icontinued: ‘It’salotofcashtobecarryingloose, though,soletmejuststashitinmywallet... ’ (Gendler2008a:637)

Gendlerherselfprovidesaconcisestatementoftheproblemraisedbythiscase:

Howshouldwedescribemymentalstateasmy fingerssearchedformywalletto housetheexplicitlywallet-compensatorymoney?(Gendler2008a:637)

Gendlerclearlyseemstobelievethatshedoesnothaveherwallet indeed,she explicitlysayssotoherfriend.Atthesametime,however,herbehaviordoesnot fitwiththebeliefshehasopenlyexpressed.Givenherbelief,hernon-verbal behavior(movingher fingerstosearchforthewallet)willyieldnousefuloutcome, forsheknowsthewalletissimplynotthere.Thesameappliestoherverbal behavior(‘letmejuststashitinmywallet’);givenherbeliefthatthewalletisnot there,theintentionthatsheisverballyexpressingcannotbefulfilled.

Toseewhycognitivedissonanceisaproblem,notethatbeliefisgenerallytakento haveanintimateconnectionwithaction.Thisseemstobepartofour ‘folk,’ commonsenseconceptionofbelief putsimply,weexpectpeopletoactinways that fitwellwiththeirbeliefs,andwhentheydonotactinthoseways,westart doubtingwhethertheyreallydohavethebeliefsinquestion.Furthermore,thebelief–actionconnectioniscentraltomanyphilosophicalaccountsofbelief(seeforinstance Stalnaker1984andGreco,Chapter2inthisvolume).Oncethisideaisinplace,itis easytoseewhycognitivedissonanceisaproblem.PartofGendler’sverbalbehavior (‘Idon’thavemywallet’)indicatesthatshebelieves: Idon’thavemywallet. However, otheraspectsofherbehavior(suchassearchingforthewallet)indicatethatshe believes: Ihavemywallet.Now,ifweadopted Unity’srequirementof Consistency,one oftheseoptionsmustbeincorrect,forthetwobeliefsareofcourseinconsistent.

Fragmentationoffersamorepromisingsolution.Gendler’sinitialassertion(‘I don’thavemywallet’)isguidedbyinformationinonefragment,afragmentwhich includesthebelief Idon’thavemywallet.Gendler’sotheractions(suchas searchingforthewallet)areguidedbyinformationinadifferentfragment,a fragmentwhichincludesthebelief Ihavemywallet. Gendlerholdsbothbeliefs,so wecanmakesenseofherbehavior;however,thetwobeliefsarestoredindifferent fragments,sointra-fragmentconsistencyispreserved.

Letusnowmoveonto ‘implicitbias.’ Brownsteindefinesthenotionand providesanexample:

‘Implicitbias’ isatermofartreferringtorelativelyunconsciousandrelatively automaticfeaturesofprejudicedjudgmentandsocialbehavior....themost

strikingandwell-knownresearchhasfocusedonimplicitattitudestoward membersofsociallystigmatizedgroups,suchasAfrican-Americans,women, andtheLGBTQcommunity...Forexample,imagineFrank,whoexplicitly believesthatwomenandmenareequallysuitedforcareersoutsidethehome. Despitehisexplicitlyegalitarianbelief,Frankmightneverthelessbehaveinany numberofbiasedways,fromdistrustingfeedbackfromfemaleco-workersto hiringequallyqualifiedmenoverwomen.(Brownstein2019)

Brownsteinoffersseveralempiricallydocumentedexamplesofimplicitbias,but Frank’simaginarycasewillbeenoughforourpurposes.¹⁹ Thecentralquestionis: WhatdoesFrankbelieveconcerninggenderequality?Hisexplicitverbalbehavior suggeststhathehasthefollowingbelief: Womenandmenareequallysuitedto careersoutsidethehome.Atthesametime,otheraspectsofhisbehavior(likehis behaviorintheworkplace)suggestthathebelievesthat womenandmenarenot equallysuitedtocareersoutsidethehome.

Again,sincethetwobeliefsareinconsistent,Frankcannothavebothofthem, accordingtounity.Fragmentationoffersanalternative.²⁰ Frank’soveralldoxastic statecouldbedividedintovariousfragments,withonefragmentincludinghis egalitarianbeliefandguidinghisexplicitverbalbehaviorandanotherfragment includinghisanti-egalitarianbeliefandguidingotheraspectsofhisbehavior,such ashisdecisionsintheworkplace.AsinGendler’scognitivedissonancecase,then, fragmentationmightgiveusnewexplanatorytoolstomakesenseof ‘inconsistent’ behaviorexhibitedbyimplicitlybiasedsubjectslikeFrank.²¹

3.FragmentationandCognitiveArchitecture

3.1.HorizontalFragmentation

It’susefultodistinguishfragmentationviewsfromaclusterofviewswhichhave alsoreceivedthelabel ‘fragmentation’ (cf.Greco2014).Wecancallfragmentation asweunderstandithere ‘horizontal’ (orintra-attitude-type)fragmentationasit involvestheclaimthatthe samekind ofattitudeorrepresentationalstateis

¹⁹ SeeSchwitzgebel(2010)foramoredetailedexampleofthesamekind.

²⁰ Forfragmentationapproachestocognitivedissonanceandimplicitbias,seeforinstanceBendaña (Chapter11inthisvolume),Borgoni(2018),andMandelbaum(2015).

²¹Thereareotherargumentsagainstunityandinfavoroffragmentationthatwewillnotbeableto discusshere.Inparticular,thehypothesisoffragmentationplaysanimportantroleinDavidson’ s (1982/2004,1986/2004)accountofrationalityandaction,inEgan’s(2008)theoryofperceptionand beliefformation,andinGreco’s(2014)discussionofepistemicakrasia.Thesepotentialapplicationsof fragmentationareimportantandshouldbeexploredindetail,buthereweprefertofocusona narrowersetofissuestoavoidmakingthediscussiontoodifficulttofollow.Theinterestedreaderis alsoreferredtoBendañaandMandelbaum(Chapter3inthisvolume)forapresentationofempirical evidenceinfavorof Fragmentation.

fragmented;thatis,anagent’ s beliefs aresaidtobedividedintodifferent fragments.

Acontrastingfamilyofviewshavebeenofferedasexplanationsofcognitive dissonance(seeSection2.6).Despitegreatdifferencesindetail,theseviewsshare theideathatdifferent kinds ofrepresentationalmentalstatesareinvolvedin,and responsiblefor,themanifestationsofourapparentbeliefs:assertionsandexplicit avowals,ontheonehand,andmoreautomatic,action-entrenchedresponses,on theother.OneprominentversionofthisideaisdevelopedbyGendler(2008a, 2008b).Gendlerdrawsadistinctionbetweenbeliefandwhatshecalls ‘alief,’ where theformerisresponsibleforexplicitavowalsandthelatteris ‘ associative, automatic,and arational’ (Gendler2008a:641).

Thisfamilyofviewscanbecalled ‘vertical’ fragmentation(orinter-attitudetypefragmentation)asitpositsdifferent kinds ofrepresentationalmentalstates. Thisisdifferentfromthe ‘horizontal’ (orintra-attitude-type)fragmentation discussedsofar.Whilehorizontalandverticalfragmentationviewsareinprinciplecompatible,theypresent primafacie competingexplanatorystrategies regardingthephenomenonofcognitivedissonance.²²Sincehorizontalfragmentationviewswillbeourmainfocus,wewillonlyuse ‘fragmentation’ torefertothis groupofviewsinwhatfollows.

3.2.Fragmentation,CognitiveProcesses,Modularity

Anotherquestionconcernstheconnectionbetweenfragmentationandcognitive architecture.Bysayingthatanattitudelikebeliefisfragmented intheminimal senseofF1–F4above,oneisnotautomaticallymakingaclaimaboutthepsychologicalprocessesorsystemsthatproducebeliefs.Anagent’soverallbeliefstate maybesplitintoseveralfragments,butthisdoesnotimplythatbeliefsinthesame fragmentarealltheresultofthesametypeofpsychologicalprocess,orthatbeliefs indifferentfragmentsmustbetheresultofdifferentprocesses.Forinstance, theoriesoffragmentationaredistinctfrom(butcompatiblewith)dual-process anddual-systemviews.²³Ofcourse,thisdoesn’tpreventfragmentationtheorists fromprovidingasubstantialaccountofhowfragmentationisimplemented cognitively seeBendañaandMandelbaum(Chapter3inthisvolume)forsuch aproposal.

Forparallelreasons,wealsotakefragmentationtobe primafacie distinctfrom modularity.²⁴ Iffragmentationaboutbeliefturnsouttobecorrect,thenthebeliefs

²²Accordingtoourclassification, ‘verticalfragmentation’ viewsinclude,e.g.,Bilgrami(2006),who distinguishescommittalfromdispositionalbeliefs;Gendler(2008a),whocontrastsaliefwithbelief;and Gertler(2011),whoseparatesoccurrentfromdispositionalbeliefs.

²³SeeFrankish(2010)foranoverviewofdual-processanddual-systemviews.

²⁴ SeeFodor(1983).

ofanordinarycognitiveagentbelongtodifferentfragments.However,itdoesnot followthatsomeofthosebeliefsbelongtodifferentcognitivemodules,forthey mightallbeprocessedinacentral,non-modularway.Sothetwonotions (fragmentationandmodularity)yieldcross-cuttingdistinctionsamongcognitive states.Again,thisisjusttosaythatthetwonotionsareconceptuallydistinct,not thattherecannotbeinterestingconnectionsbetweenthephenomenainquestion.

Insum,tobea(horizontal)fragmentationviewmeansbeingcommittedto (somethinglike)claimsF1–F4inSection1,andthiscommitmentiscompatible withdifferentanswerstoquestionsaboutcognitivearchitecture,psychological processes,systems,andsoforth.Aswewillsee,manytheoriesoffragmentationdo takeonmoresubstantialcommitmentsregardingthenatureofbeliefand/or cognitivearchitecture.Still,theseadditionalcommitmentsarenotimmediate consequencesofthecorethesesthatdefinethefragmentationhypothesis.

4.TheoriesofFragmentation

Theideaoffragmentationwaspowerfullyexpressedinphilosophybyafew authorsinthe1980sbutseemstohavelaindormantsincethen.Itisonlyin recentyearsthattheideahasattractedrenewedinterest.Here,weintroducetwo influentialearlytheoriesoffragmentation,byChristopherCherniakandby RobertStalnaker,andsketchsomeoftherecentdevelopments.

4.1.CherniakonMemoryandCognitiveArchitecture

Inhisbook MinimalRationality (1986),ChristopherCherniakdevelopsan accountofrationalityinwhichfragmentationplaysanimportantrole.²⁵ The mainmotivationbehindCherniak’stheoryissuccinctlystatedinthefollowing passage:

Howrationalmustacreaturebetobeanagent,thatis,toqualifyashavinga cognitivesystemofbeliefs,desires,perceptions?Untilrecently,philosophyhas uncriticallyacceptedhighlyidealizedconceptionsofrationality.Butcognition, computation,andinformationhavecosts;theydonotjustsubsistinsome immaterialeffluvium.Weare,afterall,onlyhuman.

²⁵ Cherniakgenerallyusestheterm ‘compartmentalization,’ buthedoessometimesspeakof ‘fragments’ (seeforinstanceCherniak1986:68).Hereweusetheterms ‘compartmentalization’ and ‘fragmentation’ interchangeably.