https://ebookmass.com/product/the-effect-of-fines-on-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Empirical Correlation of Soil Liquefaction Based on SPT TV-Value and Fines Content Kohji Tokimatsu & Yoshiaki

Yoshimi

https://ebookmass.com/product/empirical-correlation-of-soilliquefaction-based-on-spt-tv-value-and-fines-content-kohji-tokimatsuyoshiaki-yoshimi/ ebookmass.com

Reformation, Resistance, and Reason of State (1517-1625)

Sarah Mortimer

https://ebookmass.com/product/reformation-resistance-and-reason-ofstate-1517-1625-sarah-mortimer/

ebookmass.com

Effects of Sand Compaction on Liquefaction During the Tokachioki Earthquake Yorihiko Ohsaki

https://ebookmass.com/product/effects-of-sand-compaction-onliquefaction-during-the-tokachioki-earthquake-yorihiko-ohsaki/

ebookmass.com

Hadzic's Peripheral Nerve Blocks and Anatomy for Ultrasound-Guided Regional Anesthesia 3rd Edition Admir

Hadzic

https://ebookmass.com/product/hadzics-peripheral-nerve-blocks-andanatomy-for-ultrasound-guided-regional-anesthesia-3rd-edition-admirhadzic/ ebookmass.com

Nelson English: Year 1/Primary 2: Pupil Book 1 Wendy Wren

Sarah Lindsay

https://ebookmass.com/product/nelson-english-year-1-primary-2-pupilbook-1-wendy-wren-sarah-lindsay/

ebookmass.com

Advertising and Integrated Brand Promotion 8th Edition

Thomas O'Guinn

https://ebookmass.com/product/advertising-and-integrated-brandpromotion-8th-edition-thomas-oguinn/

ebookmass.com

Prince of Endless Tides (Darkmourn Universe Book 4) Ben Alderson

https://ebookmass.com/product/prince-of-endless-tides-darkmournuniverse-book-4-ben-alderson/

ebookmass.com

Analytical Techniques for the Elucidation of Protein Function Isao Suetake

https://ebookmass.com/product/analytical-techniques-for-theelucidation-of-protein-function-isao-suetake/

ebookmass.com

SAP S/4HANA Financial Accounting Configuration: Learn Configuration and Development on an S/4 System, 2nd Edition Andrew Okungbowa

https://ebookmass.com/product/sap-s-4hana-financial-accountingconfiguration-learn-configuration-and-development-onan-s-4-system-2nd-edition-andrew-okungbowa-2/

ebookmass.com

Junqueira’s Basic Histology Text and Atlas 14th Edition

Anthony L. Mescher

https://ebookmass.com/product/junqueiras-basic-histology-text-andatlas-14th-edition-anthony-l-mescher/

ebookmass.com

SOILSANDFOUNDATIONSVol.48,No.5,713–725,Oct.2008

JapaneseGeotechnicalSociety

THEEFFECTOFFINESONCRITICALSTATEANDLIQUEFACTION RESISTANCECHARACTERISTICSOFNON-PLASTICSILTYSANDS

ANTHI PAPADOPOULOUi) andTHEODORA TIKAii)

ABSTRACT

Monotonicandcyclictriaxialtestswerecarriedoutonsand-siltmixturesfortheinvestigationoftheeŠectofˆnes contentontheircriticalstateandliquefactionresistancecharacteristics.Boththeundrainedandthedrainedmonotonictestsproduceauniquecriticalstatelineforeachtestedmixture,whichmovesdownwardswithincreasingˆnescontentuptoathresholdvalueof35z andthenupwards.AtagivenvoidratioandmeaneŠectivestress,theliquefaction resistanceratiodecreaseswithincreasingˆnescontentuptothesamethresholdvalueof35z,andincreasesthereafter withfurtherincreasingˆnescontent.However,atagivenintergranularvoidratio,deˆnedastheratioofthevolume of ˆnesplusvoidstothatofsandparticles,liquefactionresistanceratioincreaseswithincreasingˆnescontentuptothe thresholdvalue.Thethresholdˆnescontentvalue,whichisanimportantparameterindeterminingthetransitionfrom thesanddominatedtothesiltdominatedbehaviourofsand-siltmixtures,isrelatedtotheirparticlepacking. Anexpressionisproposedfortheestimationofthethresholdˆnescontentasafunctionofthemeandiameterratio, d50/D50, andthevoidratio.Theresults,presentedherein,alsoshowthatforeachtestedmixturetheliquefactionresistanceratio isrelatedtothestateparameterandthatthisrelationisin‰uencedbytheeŠectivestresslevelandˆnescontent.The resultsonthesand-siltmixturesaresupportedbysimilarresultsonnaturalsiltysands.

Keywords: criticalstate,ˆnes,liquefaction,non-plastic,sands,silt,stateparameter,threshold,voidratio(IGC: C3/D6/D7/E7)

INTRODUCTION

Liquefactionofsandysoilsundermonotonicandcyclicloadingconditionsisconsideredtobeoneofthe majorcausesoffailureofearthstructuresandfoundations.Fieldobservationsfromfailuresduetoliquefactionhaveshownthatbothcleansandsandsandscontainingˆnes(particleswithdiameterlessthan75 mm)aresusceptibletoliquefaction.Semi-empiricalˆeld-based proceduresforevaluatingtheliquefactionpotentialduringearthquakesarebasedoncorrelationsbetweenˆeld behaviourandin-situindextests,suchasstandard penetrationtest(SPT),conepenetrationtest(CPT), Beckerpenetrationtest(BPT)andshearwavevelocity(V s).Seedetal.(1985)proposedtheoldestandperhapsthe mostwidelyusedprocedureinwhichthecyclicstressratio,CSR=tav/s? o,iscorrelatedwiththeSPTblowcounts, correctedforbotheŠectiveoverburdenstressandenergy, (N1)60,forcleansandsandsiltysandswithˆnescontent greaterthan5z andearthquakemagnitude, M=7.5.Accordingtothiscorrelation,thepresenceofˆnesinsilty sandsincreasestheirliquefactionresistanceandconsequentlydecreasesthepotentialofliquefactiondevelopment.ThisbeneˆcialeŠectofˆnesontheliquefaction resistanceofsiltysandshasbeenalsoadoptedinall

moderncodes,(NCEER,1997andEurocode8)andmay beexplainedbyconsideringempiricalcorrelationsbetweentherelativedensity, Dr,and N valueoftheSPT, whichalsoaccountforthegrainsizeeŠectsonthe penetrationresistanceofsandysoils.Skempton(1986) foundthatthenormalized(N1)60/Dr 2 valueincreaseswith increasinggrainsize(or D50),whichimpliesthatfora given(N1)60 value, Dr increaseswithdecreasing D50 value (orincreasingˆnescontent).CubrinovskiandIshihara (2002)usedthevoidratiorange, emax -emin toquantifythe eŠectofgradingpropertiesontheSPTresistance.They foundthatthenormalized(N1)60/Dr 2 valuedecreaseswith increasing emax -emin.As emax -emin increaseswithincreasing ˆnescontent,theaboveˆndingsimilarlyindicatesthat foragivenvalueof(N1)60, Dr increasesastheˆnescontentincreases.

Inlaboratory,althoughnumerousstudieshavebeen performedinordertoinvestigatetheeŠectofˆnescontentontheliquefactionresistanceratioofsiltysands,the resultsappeartobecon‰icting.Ishihara(1996)andAminiandQi(2000),amongothers,foundthattheliquefactionresistanceratioincreaseswithincreasingˆnescontent(positiveeŠect),andotherslikeTroncosoandVerdugo(1985),Vaid(1994)andMiuraetal.(1995)suggestedthattheliquefactionresistanceratiodecreaseswithin-

i) ResearchStudent,DepartmentofCivilEngineering,AristotleUniversityofThessaloniki,Greece ii) Professor,ditto(tika@civil.auth.gr).

ThemanuscriptforthispaperwasreceivedforreviewonJuly9,2007;approvedonJuly23,2008.

WrittendiscussionsonthispapershouldbesubmittedbeforeMay1,2009totheJapaneseGeotechnicalSociety,4-38-2,Sengoku,Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo112-0011,Japan.Uponrequesttheclosingdatemaybeextendedonemonth.

713

PAPADOPOULOUANDTIKA

creasingˆnescontent(negativeeŠect),whereasothers likeThevanayagametal.(2000),PolitoandMartin (2001),XenakiandAthanasopoulos(2003)andYanget al.(2004)foundthatthereisanincreaseofliquefaction resistanceratiowithincreasingˆnescontentuptoacertainvalueandadecreasethereafterwithfurtherincreasingˆnescontent.TheˆnescontentatwhichtheeŠectof ˆneschangesfrompositivetonegativehasbeentermedas threshold,orlimiting,ortransitional.

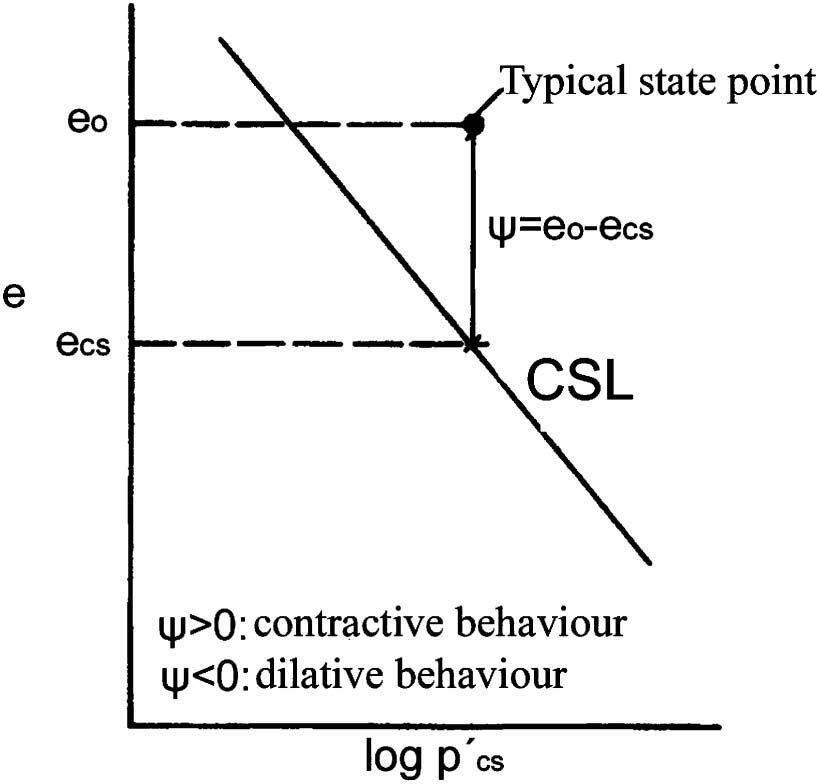

Thecriticalstate,deˆnedasthestateatwhichthesoil continuestodeformatconstantshearstressandconstant voidratio,hasincreasinglybeenusedasafundamental statetocharacterizethestrengthanddeformationpropertiesofsandsinlimitequilibrium(Casagrande,1936; Roscoeetal.,1958;SchoˆeldandWroth,1968).Atthis state,thereisauniquerelationshipamongvoidratio, ecs, meaneŠectivestress, p? cs,andshearstrength, qcs,expressedbythecriticalstateline,CSL,inthevoidratio versusmeaneŠectivestressplane.Accordingtothecriticalstateconcept,thebehaviourofasanddependsnot onlyondensity,butalsoonstresslevel.Thetruestateof asandisdescribedbythelocationofitscurrentstateof stressandvolumerelativetothecriticalstateline.When thestateofasandisabovethecriticalstateline,thesand hasthetendencytocontractuponshearing,whereas whenitsstateisbelowthecriticalstateline,ithasatendencytodilate.Variousnormalizedparametershave beenproposedtocharacterizethediŠerencebetweenthe actualstateandthecriticalstateline.BeenandJeŠeries (1985)havequantiˆedthedistanceofthecurrentstate fromthecriticalstatelinebymeansofastateparameter, c,whichisthediŠerenceinvoidratiosbetweenthecurrentstateandthecriticalstatelineatthecurrentmean eŠectivestress, p? cs,Fig.1.

Recently,inanattempttore-evaluatetheeŠectof overburdenstressconsideredinthesemi-empiricalˆeldbasedprocedures,suchasSPTandCPTtests,theliquefactionresistanceratioofcleansandsduringboth monotonicandcyclicloadinghasbeencorrelatedwith

Fig.1.Deˆnitionofstateparameter(BeenandJeŠeries,1985)

thestateparameter(PillaiandMuhunthan,2001; Boulanger,2003;IdrissandBoulanger,2004).Theextensionoftheabovestatedcorrelationfromcleansandsto sandscontainingˆneswouldbebothusefulandofgreat interest.

Thepurposeoftheworkpresentedinthispaperisˆrst toclarifytheeŠectofˆnescontent, fc,onthecriticalstate lineandtheliquefactionresistancecharacteristicsofsilty sandsandthentoinvestigatewhethertheliquefaction resistanceratioofthesesoilscanberelatedtotheircriticalstate.

TESTEDMATERIALS

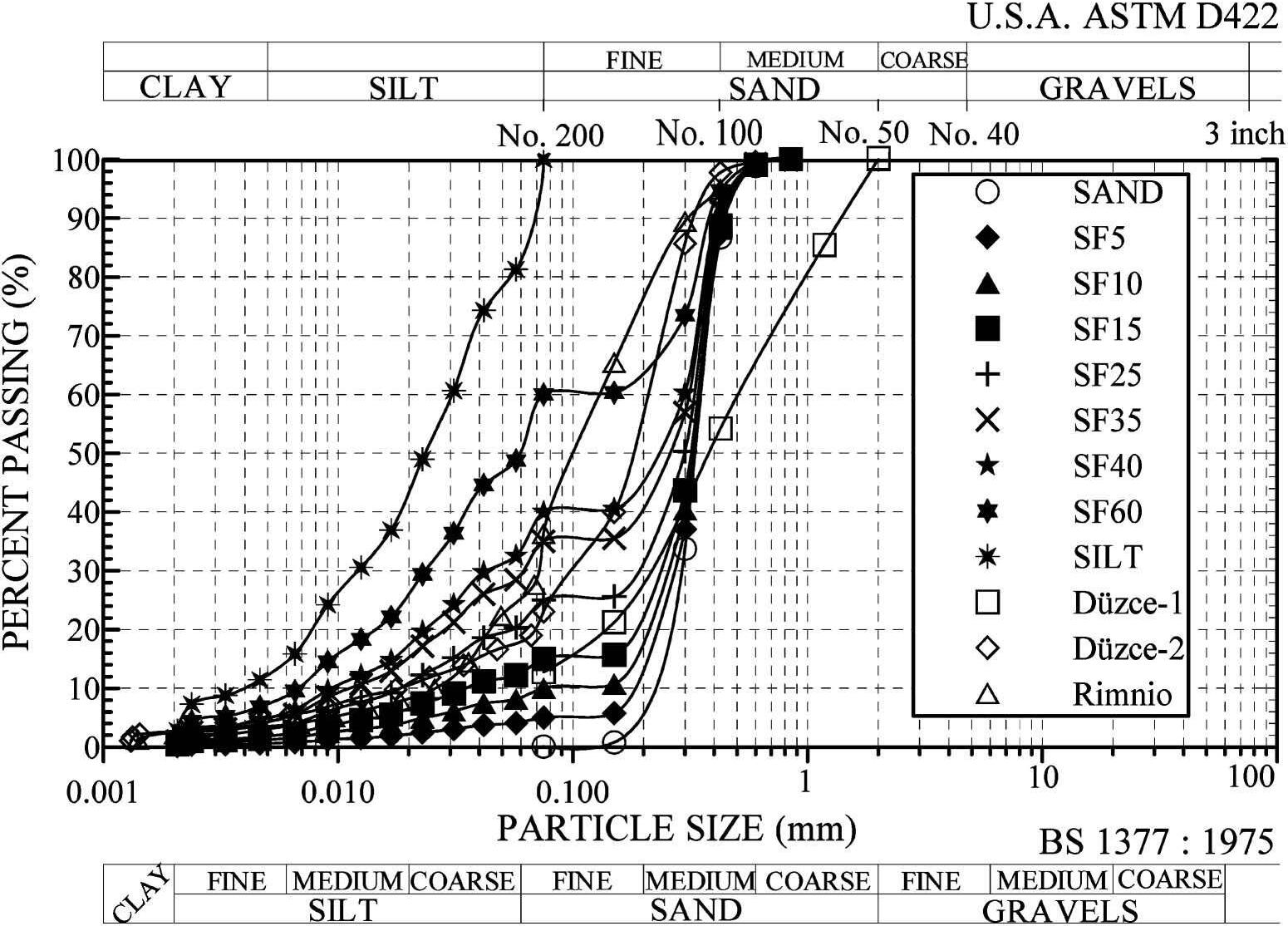

Thematerialsusedinthetestingprogrammewereartiˆcialsand-siltmixturesandnaturalsiltysands. Sand-siltmixturesweremadefromacleanquartzsand (M31)withwell-roundedgrainsandanon-plasticsilt,a groundproductofnaturalquartzdepositsfromAssyros inGreece.Sampleswerepreparedbymixingthesand(S) withthesilt(F)atpercentagesof5,10,15,25,35,40and 60z ofthetotaldrymassofthemixture(notedasSF5, SF10,SF15,SF25,SF35,SF40andSF60respectively). Testswerealsoconductedonspecimensofcleansandand puresilt.

Twonaturalsiltysands(Däuzce-1,Däuzce-2)were retrievedfromliqueˆedsitesinDäuzce,Turkey,during the1999earthquakeofmagnitude Mw =7.1andtheother wasretrievedfromthefoundationoftheRimnioembankmentbridgeinGreece,whichfailedduringthe1995 Kozaniearthquakeofmagnitude Ms =6.6(Tikaand Pitilakis,1999).

Thephysicalpropertiesandgrainsizedistributionsof thetestedmaterialsarepresentedinTable1andFig.2, respectively.

AlthoughtheASTM(D4253andD4254)testmethods forthedeterminationofminimumandmaximumvoid ratiosareapplicabletosoilsthatmaycontainupto15z, bydrymass,ofsoilparticlespassingtheNo.200(75-mm) sieve,providedtheyhavecohesionlesscharacteristics, boththesemethodswereusedinthisworkinconjunction withothersinordertogetaconsistentvalue.Inparticular,forthedeterminationoftheminimumvoidratio boththevibratorytable(ASTMD4253,method2A)and thestandardproctortestmethodswereused.Themaximumvoidratiowasdeterminedinaccordancewiththe

Table1.Physicalpropertiesoftestedmaterials

(zº75 mm)

Fig.2.Grainsizedistributionsofthetestedmaterials

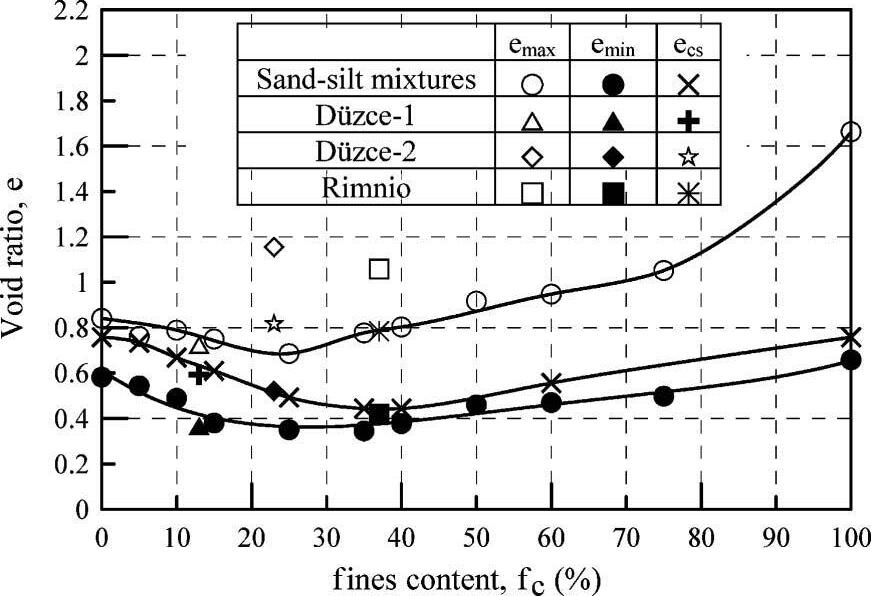

Fig.3.Variationofmaximum, emax,minimum, emin,andcriticalstate ( s ? o =100kPa), ecs,voidratioswithˆnescontent, fc,forthetested materials

ASTM(D4254,methodC)testmethodandalsobypouringdrymaterialinamouldthreetimesandconsidering theaverageasthemaximumvalue.Figure3showsthe minimumandmaximumvoidratiosofthetestedmaterials.AsshownintheaboveFigureforthesand-siltmixtures,theminimumvoidratioisobtainedataˆnescontentbetween25z and35z

TESTINGEQUIPMENTANDEXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURE

Thetestingprogrammeconsistedofmonotonicandcyclictriaxialtestsforthedeterminationofthecriticalstate lineandtheliquefactionresistanceratioofthetested materialsrespectively.Bothtypesoftestswereperformed

usingaclosed-loopautomaticcyclictriaxialapparatus (MTSSystemsCorporation,U.S.A.).Itsprinciplesof operationaregivenindetailinPapadopoulou(2008). Thespecimens(height/diameter§100mm/50mm) wereformedbymoisttampingatawatercontentvarying between4z and12z forallthetestedmaterialsand35z onlyforthesiltspecimens,usingtheundercompaction method,introducedbyLadd(1978).Moisttampingwas preferredtootherpreparationmethods,asitproduces specimensofvaryingdensities(VerdugoandIshihara, 1996).Saturationwasachievedbypercolatingthroughoutthespecimen,fromthebottomtothetopdrainage line,ˆrstcarbondioxidegas(CO2)for20minutesand thende-airedwater.Asuctionpressureof15kPawasappliedwhiledismantlingthespecimen,measuringits dimensionsandassemblingthetriaxialcell.Inorderto ensurefullsaturation,aseriesofstepsofsimultaneous increasingcellpressureandbackpressurewereperformed,whilemaintaininganeŠectiveconˆningstressof 15kPa.Inallthetests,aˆnalbackpressureof500kPa wasfoundtobesu‹cient,astheparameterofporewater pressure, B=Du/Ds,didnotincreasebyfurtherincreasingbackpressure.Inalltheteststheparameter B had valuesfrom0.95to1.00.Nocorrectionoftheresultswas madeformembranepenetration,becauseoftheuncertainties,associatedwithsuchacorrectionandsotheraw testresultsarepresentedhere.Afterthecompletionof saturation,thespecimenswereisotropicallyconsolidated underaneŠectiveisotropicstress, s? o,rangingfrom50to 300kPa.Aperiodoftimeequaltodoubletheconsolidationtimeofthespecimenswasallowedbeforeshearing. Duringconsolidationthevolumechangeandtheaxial displacementofthespecimenswererecordedinorderto

calculatethepostconsolidationvoidratio.

Inthemonotonictests,thespecimensweresubjectedto eitherundrained(CU),ordrained(CD)compressionata constantrateofaxialdisplacementof0.05mm/min.

Inthecyclictriaxialtests,asinusoidallyvaryingaxial stress(±sd)wasappliedatafrequencyof f=0.1Hz,underundrainedconditions.Inthiswork,cyclicstressratio, CSR=sd/2s? o,correspondstodoubleamplitudeaxial strain, eDA§5z andliquefactionresistanceorcyclic resistanceratio,CRR15,isdeˆnedasthecyclicstressratio,CSR=sd/2s? o,requiredtocausedoubleamplitude axialstrain, eDA§5z at15cyclesofloading.

TESTRESULTSANDDISCUSSION

Severalstudieshaveconsideredsandscontainingˆnes asconsistingoftwomatrices,thesandgrainsmatrixand theˆnesmatrix,andanalysedtheirbehaviourintermsof theinteractionwitheachother(Vaid,1994;Thevanayagametal.,2000;PolitoandMartin,2001;Xenakiand Athanasopoulos,2003;Yangetal.,2004).Thenatureof thecontributionofsandandˆnesmatricesmaybeexpressedintermsoftheintergranularandinterˆnevoid ratiosrespectively.

Theintergranularvoidratio, eg,expressestherelative contributionofsandfractiononthebehaviourofthe mixtureandisgivenbythefollowingequation(Mitchell, 1975):

eg = VFINES+VV VSAND = fc+w・(GSF/Sr) (1 fc) (G

where VFINES isthevolumeoftheˆnes, VV isthevolume ofvoids, VSAND isthevolumeofsandgrains, fc istheˆnes content, w isthewatercontentofthespecimen, GSF isthe speciˆcgravityoftheˆnesand GSG isthespeciˆcgravity ofsandgrains.Forsaturatedspecimens(Sr =100z)and consideringthat GSF§GSG,theintergranularvoidratio aftertheconsolidationofthespecimenisexpressedas follows:

g = fc+ec (1 fc) (2) where ec isthevoidratioofthemixtureafterconsolidation.

Formixtureswithhighˆnescontents,whenthesand grainsbecomeisolated(VSAND maybeignored),theinterˆnevoidratio, ef,maybeamoreappropriateparameter tobeused(ThevanayagamandMohan,2000):

ef= VV VFINES (3)

Similarly,forsaturatedspecimens(Sr =100z)andconsideringthat GSF§GSG,theinterˆnevoidratioafterthe consolidationofthespecimenisexpressedasfollows: ef= ec fc (4)

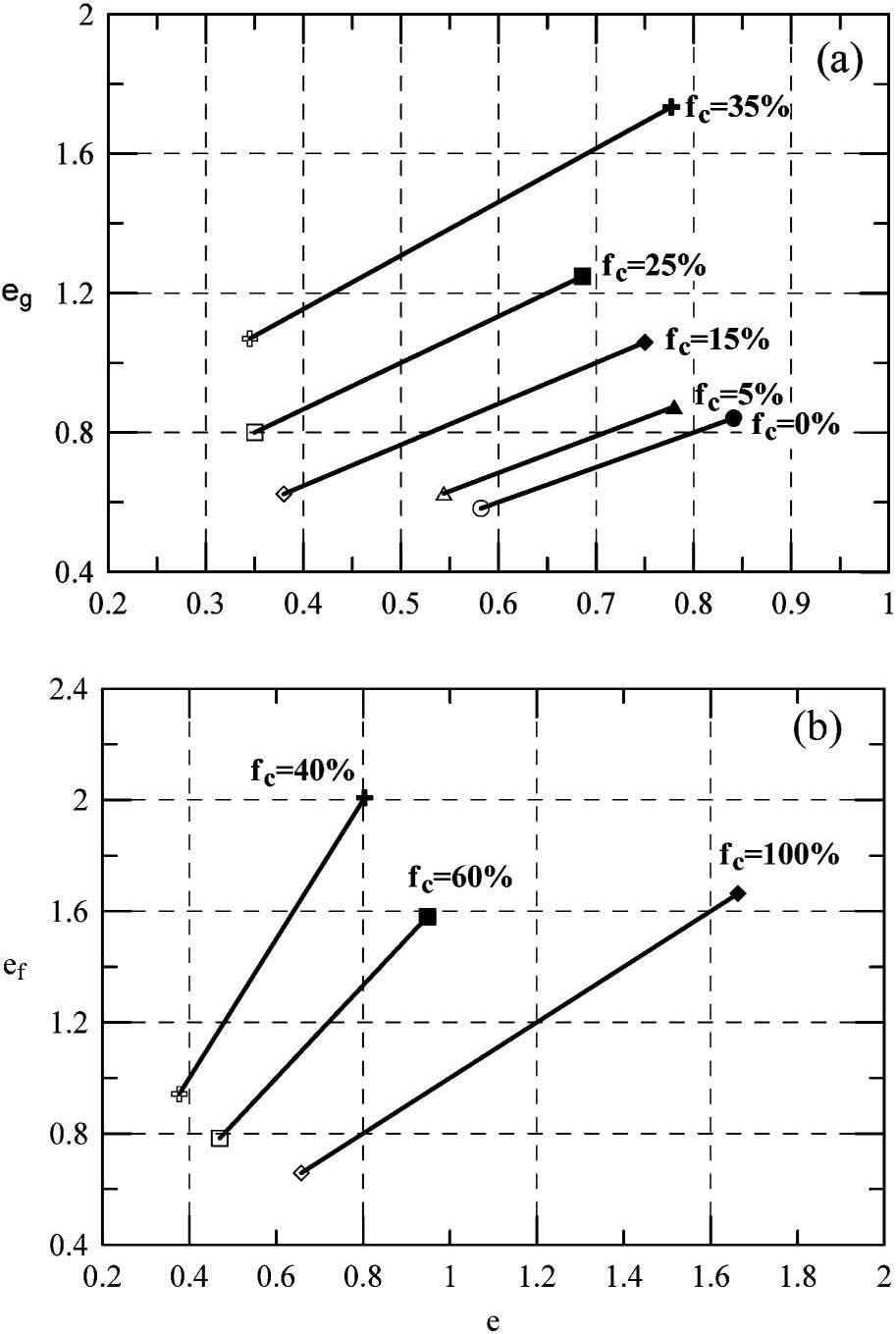

Figure4presentsthevariationofboth

eg and ef with thevoidratioofmixturesatvarious fc values.Inthefol-

Fig.4.Variationof(a)intergranularvoidratio, eg (fcÃfcth)or(b)interˆne, ef (fcÀfcth)voidratiowithvoidratio, e,atvarious fc (open andclosedsymbolsindicate emin and emax valuesrespectively)

lowingtheresultsforthecriticalstateandtheliquefactionresistancecharacteristicsofthetestedsoilsare presentedandthendiscussed.

Sand-siltMixtures

CriticalState

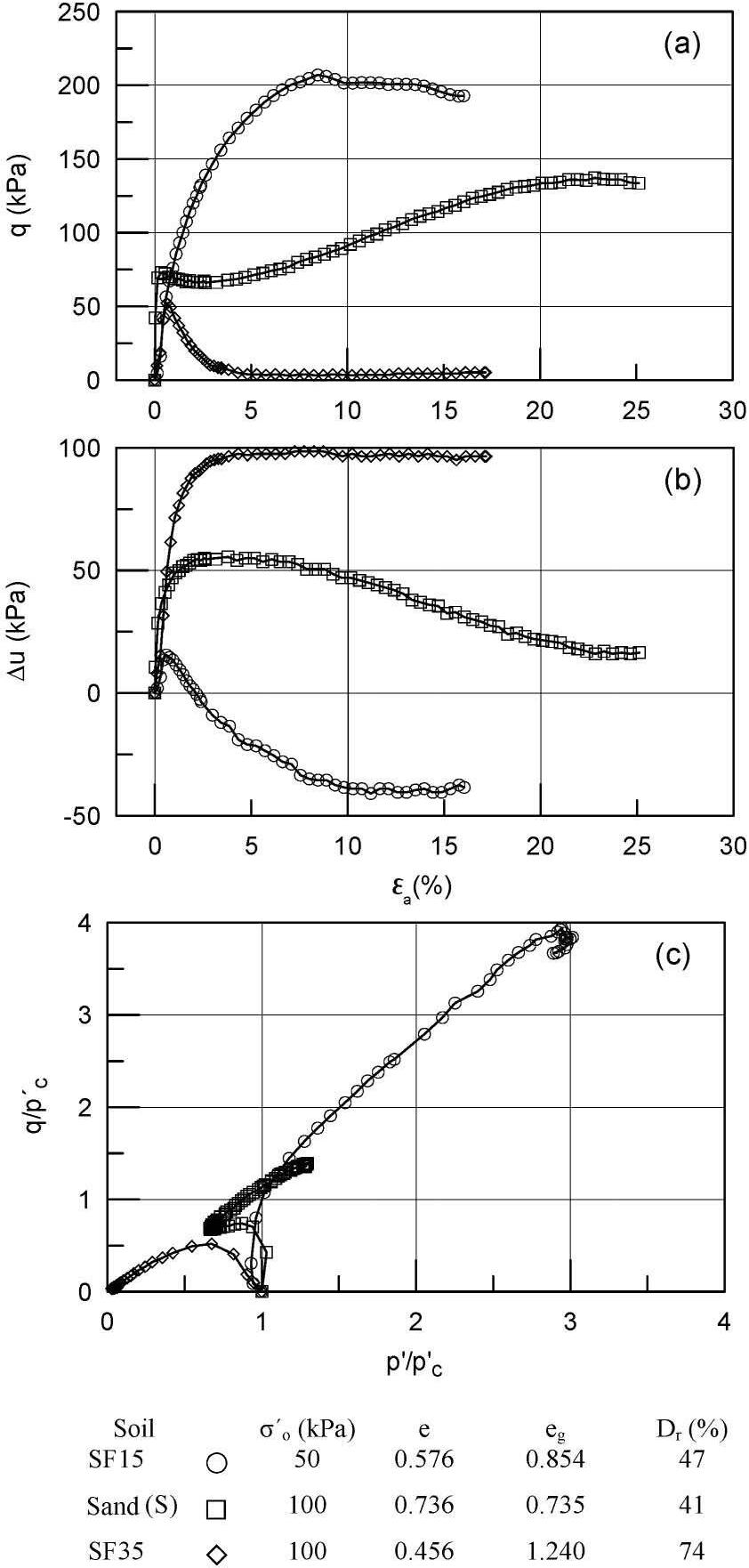

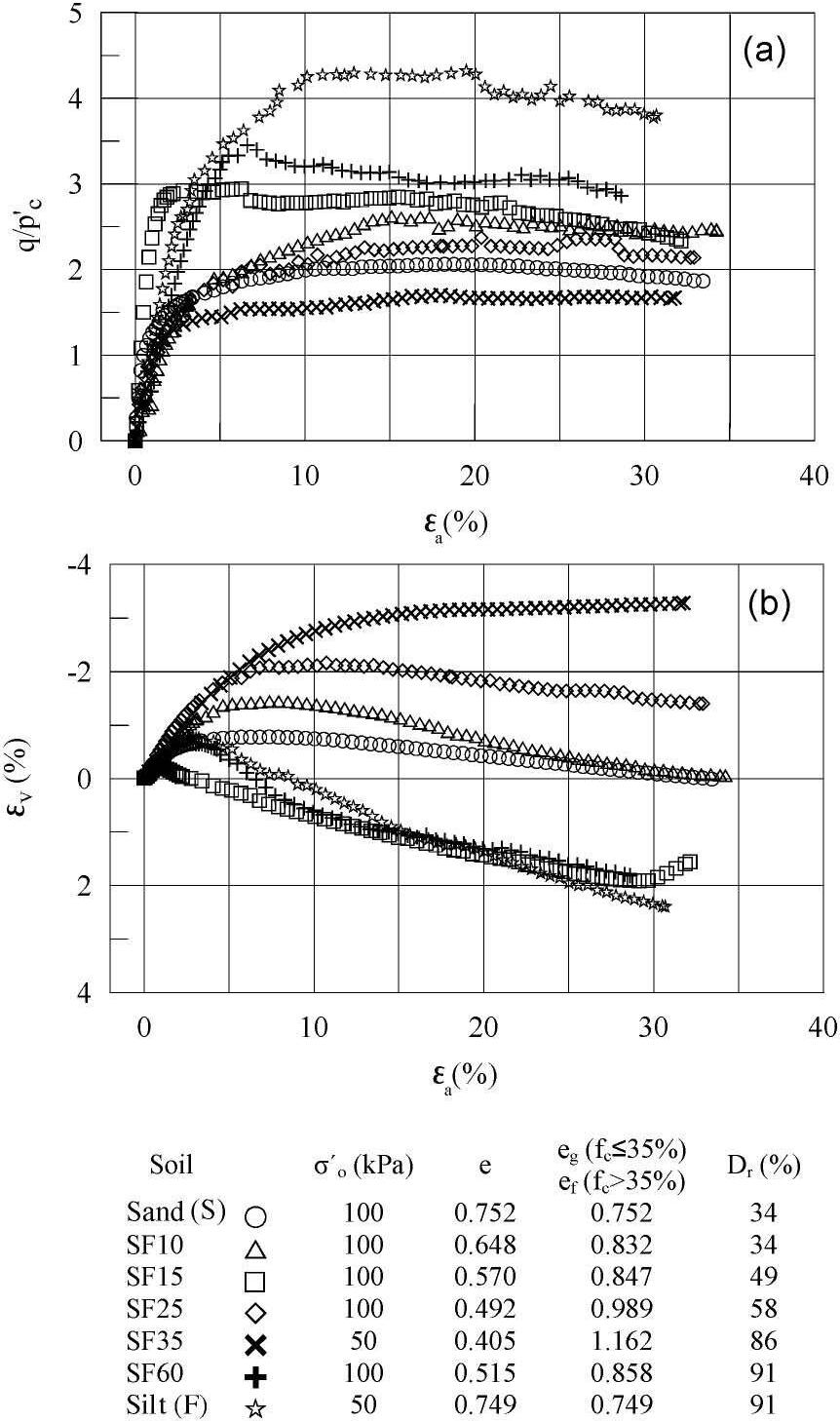

Inthemonotonicundrainedtestsitwasconsideredthat theonsetofcriticalstateconditionscorrespondstothe pointswheretheshearandthemeaneŠectivestresses,as wellastheporewaterpressure,remainedpracticallyconstantwithaxialstrain.Intheconductedtests,these pointscorrespondedtostrainsrangingfrom7z to42z, dependingonthetypeofbehaviour(contractive,contractive/dilative,dilative),thetypeofmaterialandthedensity.Figure5showstypicalresultsfromtheundrained testsinwhichcontractive,contractive/dilativeanddilativebehaviourofspecimenswasobserved.Inthedrained testsitwasconsideredthatcriticalstateconditionshad beenreachedataxialstrainsexceeding30z,wherethe rateofchangeofbothshearstressandvolumetricstrain decreasedconsiderablyorceased.Figure6presentsthe resultsfromthedrainedtests.Foralltestedmixtures,the CSLsinthe q-p? cs planearerepresentedbystraightlines passingthroughtheorigin:

Fig.5.Typicalresultsofmonotonicundrainedtriaxialtestswithcontractive(SF35),contractive/dilative(S)anddilativebehaviour (SF15),(a) q- e a,(b) D u- e a and(c) q/p? c -p?/p? c plots

where Mcs isanintrinsicconstantforeachmixture,Table 2.Ananalyticaldescriptionofthemonotonictestshas beenpresentedbyPapadopoulou(2008).

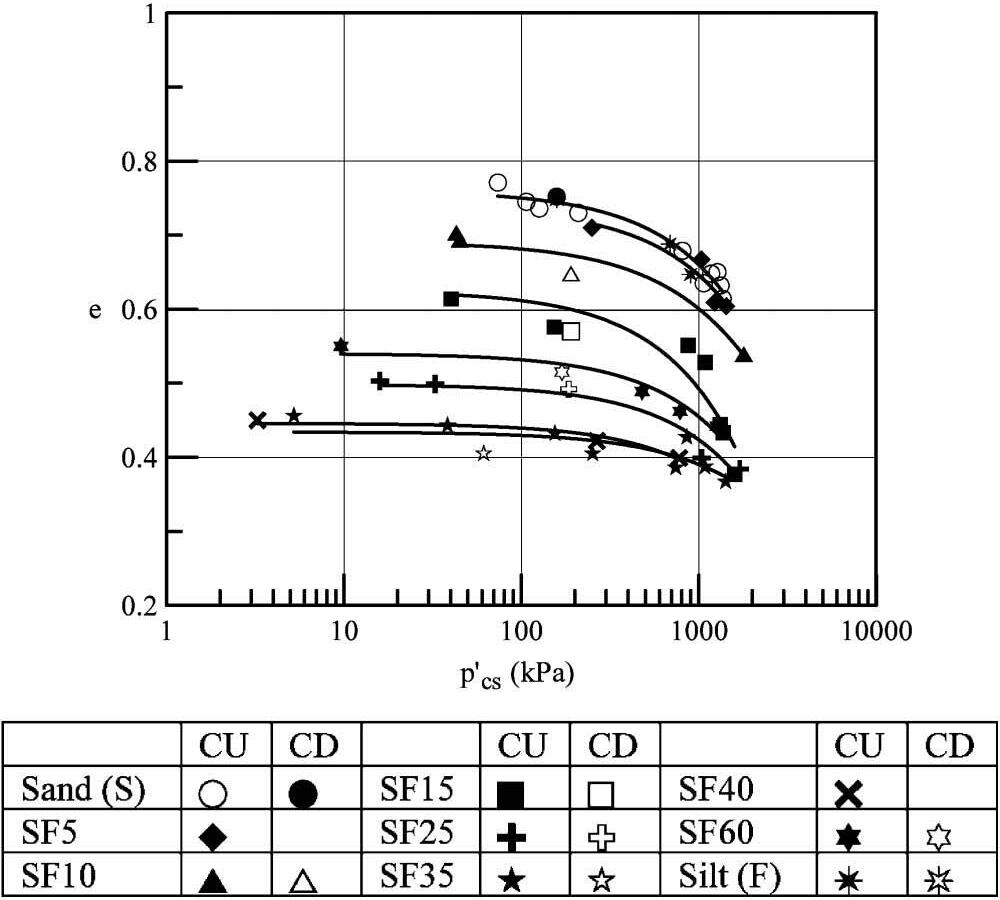

Figure7showstheCSLsinthe e-p? cs ofthesand-silt mixtures,aswellasthesandandthesilt.Asshowninthe aboveFigure,foreachsoilboththeundrainedandthe drainedtestsproduceauniqueCSL.AtsmallmeaneŠectivestresses,below300kPaapproximately,theCSLsare nearlyparallelandhaveasmallinclination.WithincreasingmeaneŠectivestresslevel,however,theysteepenand convergeatstressesabove1000kPa.Gradinganalyses wereperformedontheinitialmaterials,asusedinthe testsandafterthetests.Noparticlebreakagewasindicatedbothforthesandandthesand-siltmixtures.Asalso showninFig.7,theCSLsmovedownwardswithincreasing fc uptoathresholdvalue, fcth,of35z,andthenupwards.TheCSLsat fc valuesof35z and40z arevery close,andtheCSLsofthesandandthesiltpractically

Fig.6.Resultsfrommonotonicdrainedtriaxialtests,(a) q/p? c - e a and (b) e v - e a plots

Table2. Mcs valuesoftestedmaterials Soil M

Sand(S)1.35530.9970

SF51.41230.9991

SF101.44690.9997

SF151.54410.9848

SF251.40830.9999

SF351.43900.9994

SF401.43510.9999

SF601.43980.9992

Silt(F)1.51470.9998

Däuzce-11.50130.9999 Rimnio1.38640.9996

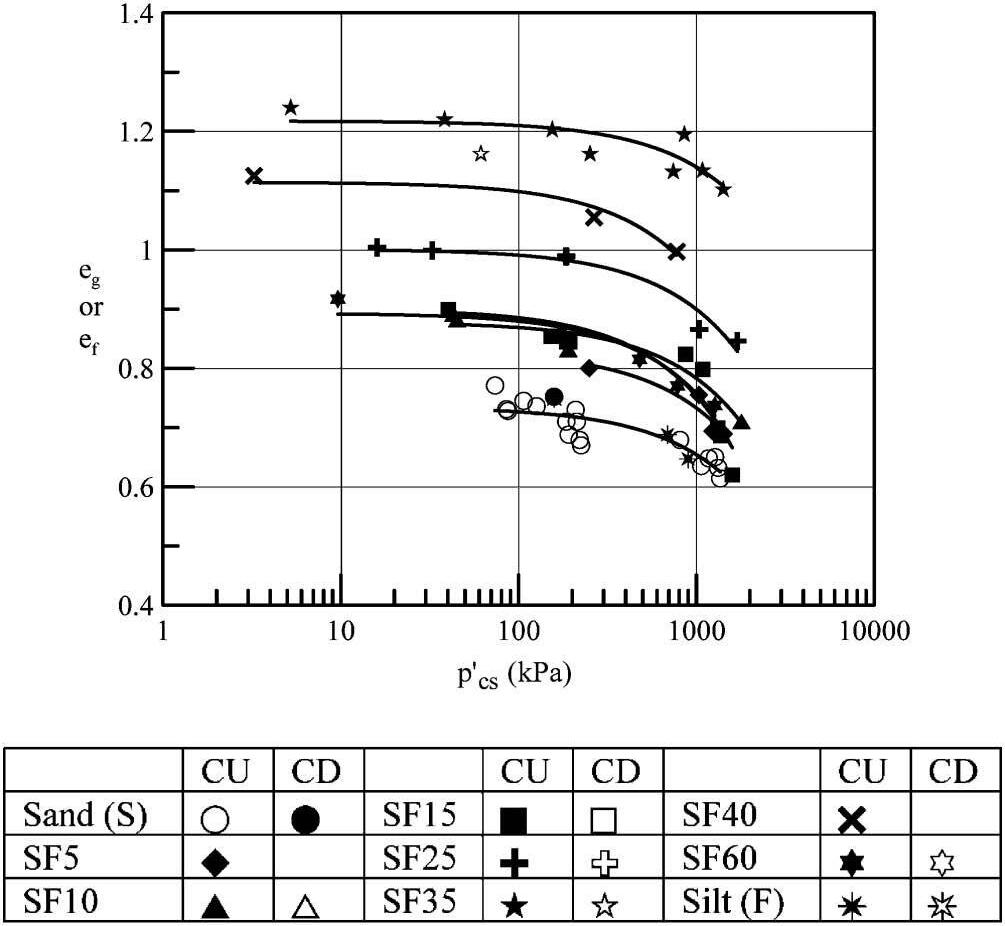

coincide.Thevariationof ecs with fc,ataneŠectivestress of s? o =100kPa,whichispresentedinFig.3,conˆrms the fcth valueof35z. TheCSLsofthesand-siltmixturesintermsof eg or ef, areshowninFig.8.Asshowninthisˆgure,inthiscase theCSLsmoveupwardswithincreasing fc uptothe fcth of 35z,andthendownwardsThismaybeattributedtothe increasingvaluesof eg astheincreasingpresenceofsilt loosensthestructureofthesand-siltmixture.At fc values greaterthanthe fcth=35z,thepresenceofsiltstartsto

Fig.7.Criticalstatelinesofsand-siltmixturesintermsofvoidratio, e

Fig.8.Criticalstatelinesofsand-siltmixturesintermsofintergranular, eg ( fcÃ35 % )orinterˆne, ef ( fcÀ35 % )voidratio

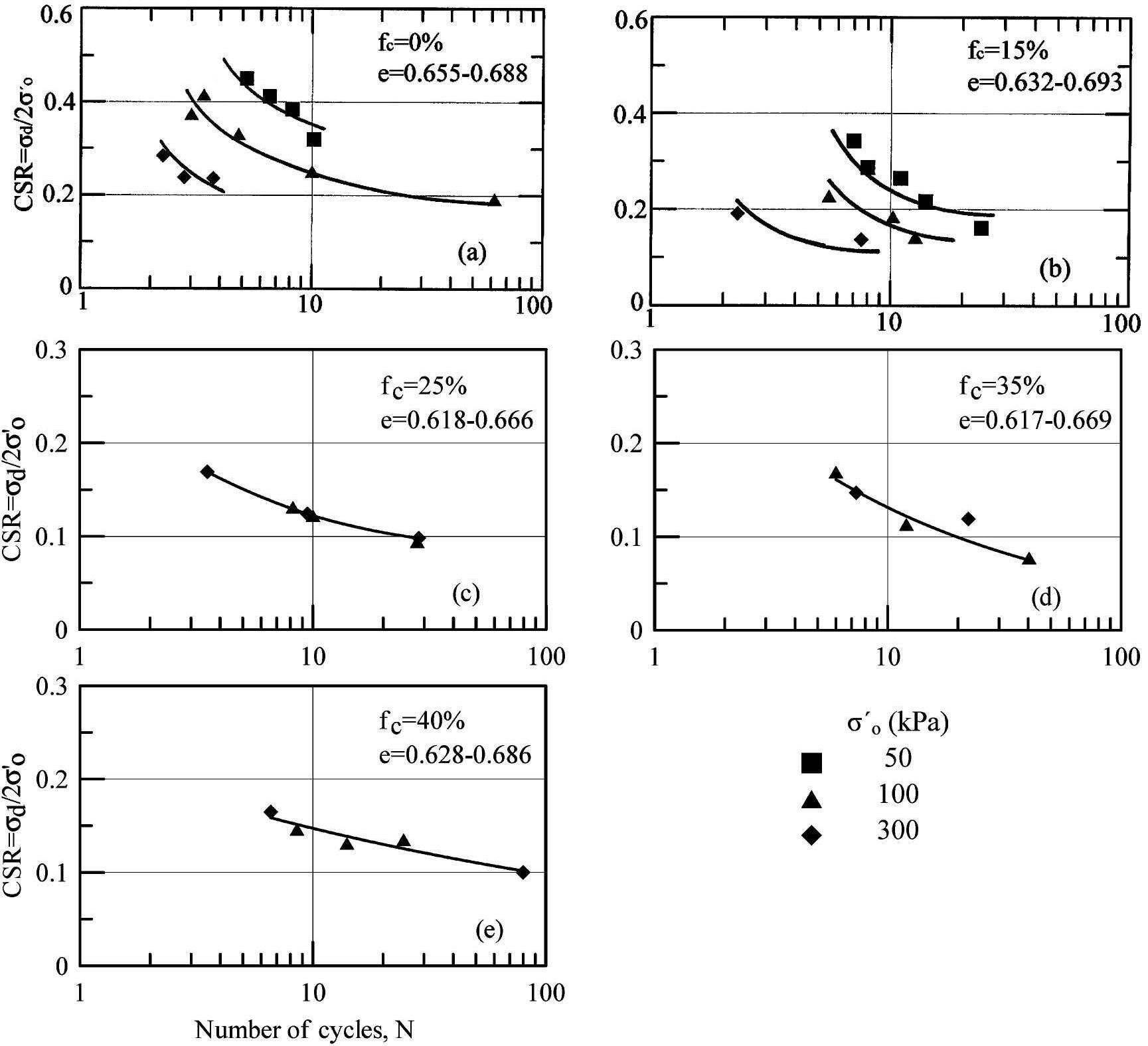

Fig.9.Variationofcyclicstressratio, s d/2 s ? o,withnumberofcycles, N,atconstantvoidratio, e,andvariouslevelsofmeaneŠectivestress, s ? o, for(a)S,(b)SF15,(c)SF25,(d)SF35and(e)SF40

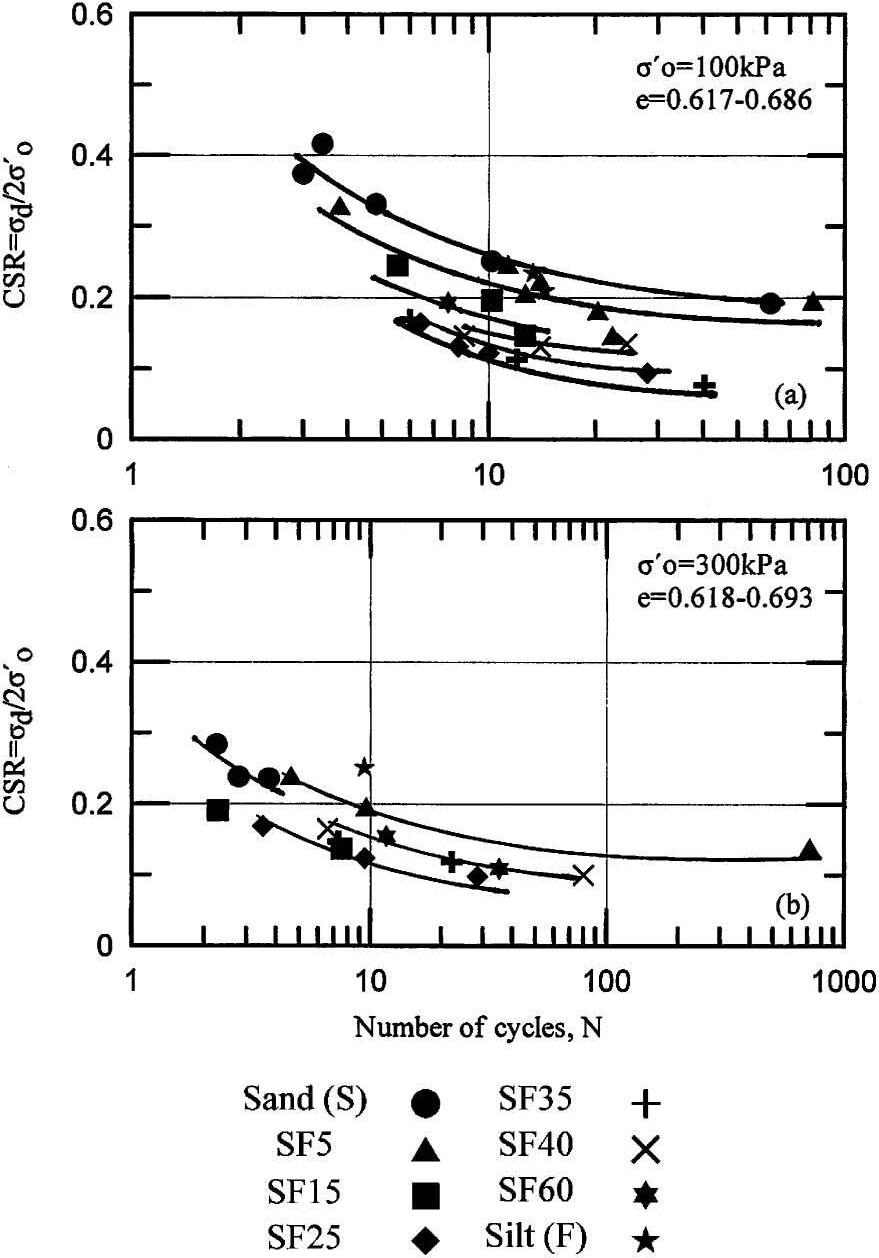

Fig.10.Variationofcyclicstressratio, s d/2 s ? o,withnumberofcycles, N,atconstantvoidratio, e,andvariousˆnesconents, fc,at s ? o,(a)100kPaand(b)300kPa

dictatethebehaviourofthesand-siltmixtureand ef is used.

Theabovedescribedbehaviourforthesand-siltmixtures,concerningtheinclinationoftheCSLsandthe eŠectof fc ontheirposition,isingeneralagreementwith theresultsoftheinvestigationsofZlatoviácandIshihara (1995),Thevanayagametal.(2002),NaeiniandBaziar (2001)andYangetal.(2006).However,inmostofthe aboveinvestigations,eitherthevalueof fcth wasinferred, ortheinclinationoftheCSLswasdeterminedoveranarrowstressrange.

LiquefactionResistance

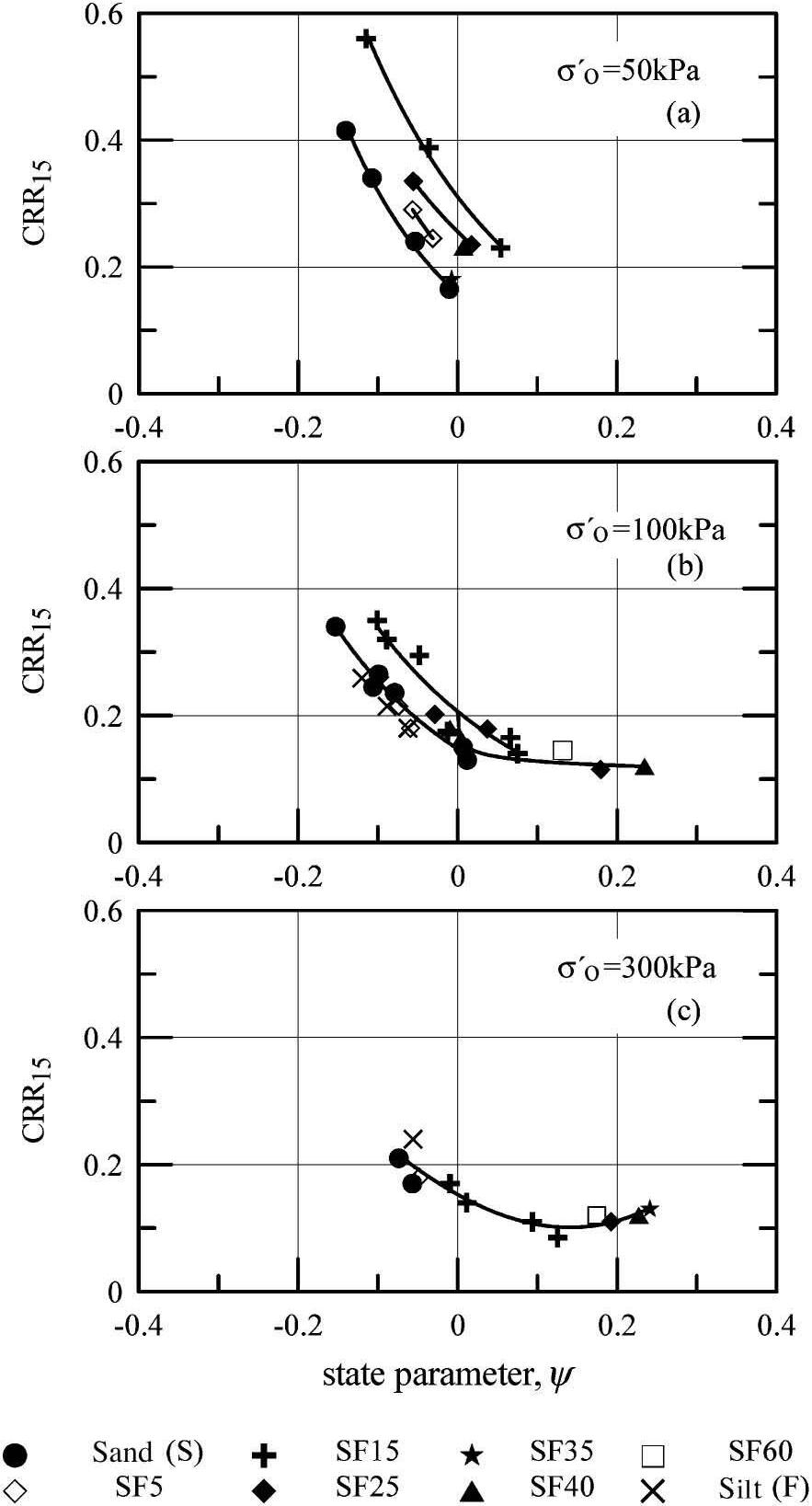

Figure9showsthevariationofCSRwithnumberof cyclesatvarious fc values.Atagivennumberofcyclesa decreaseofCSRwithincreasing s? o from50kPato300 kPaisobservedfor fc valuesupto15z.Although, resultsat s? o =50kPaandhigher fc valuesarenotavailable,Figs.9(c),(d)and(e)showthattheeŠectof s? o onthe CSRdiminishesas fc increases.TheeŠectof fc onCSRat constantvoidratioand s? o isshowninFig.10.Atagiven numberofcycles,CSRˆrstdecreaseswithincreasing fc uptoathresholdvalueof35z andincreasesthereafter withfurtherincreasing fc

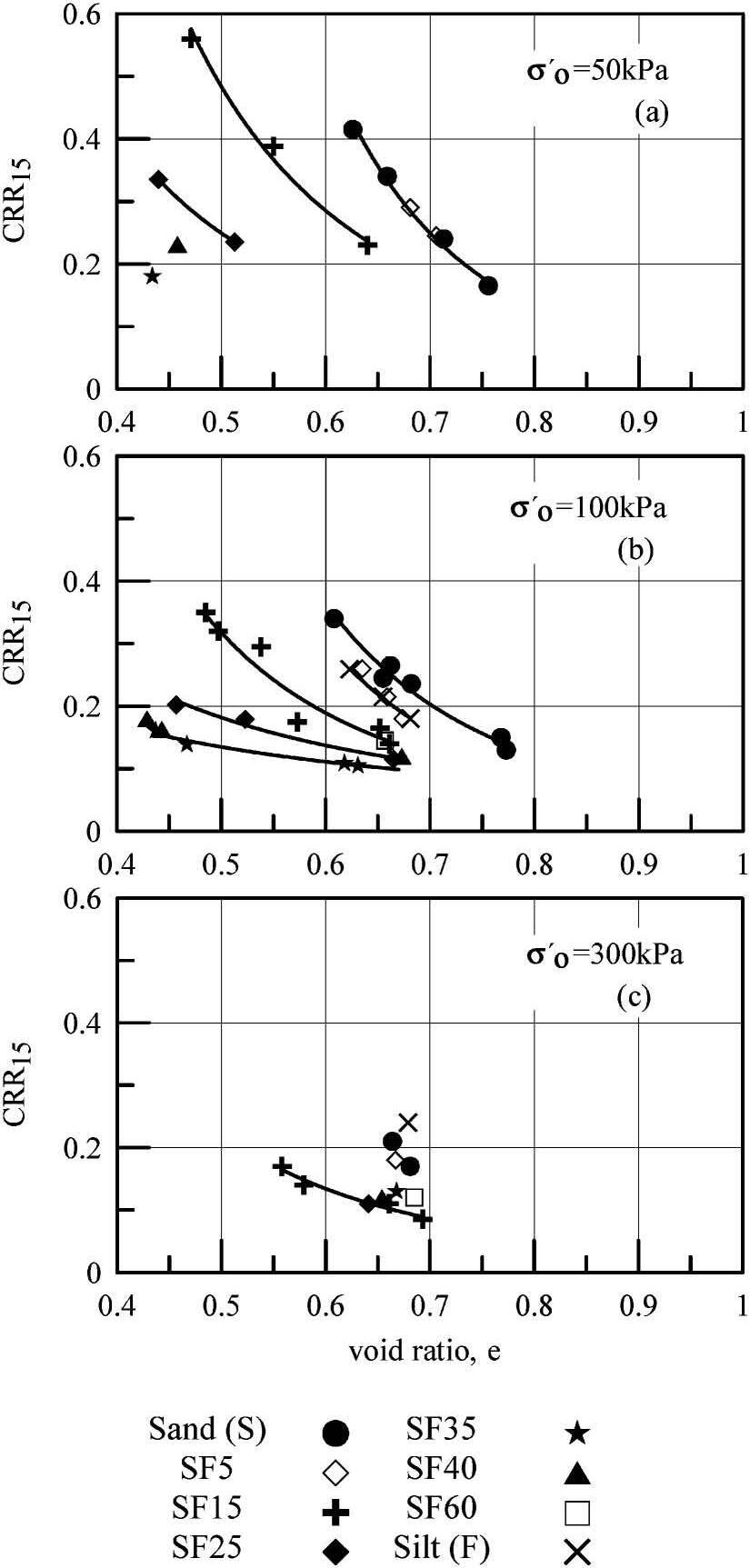

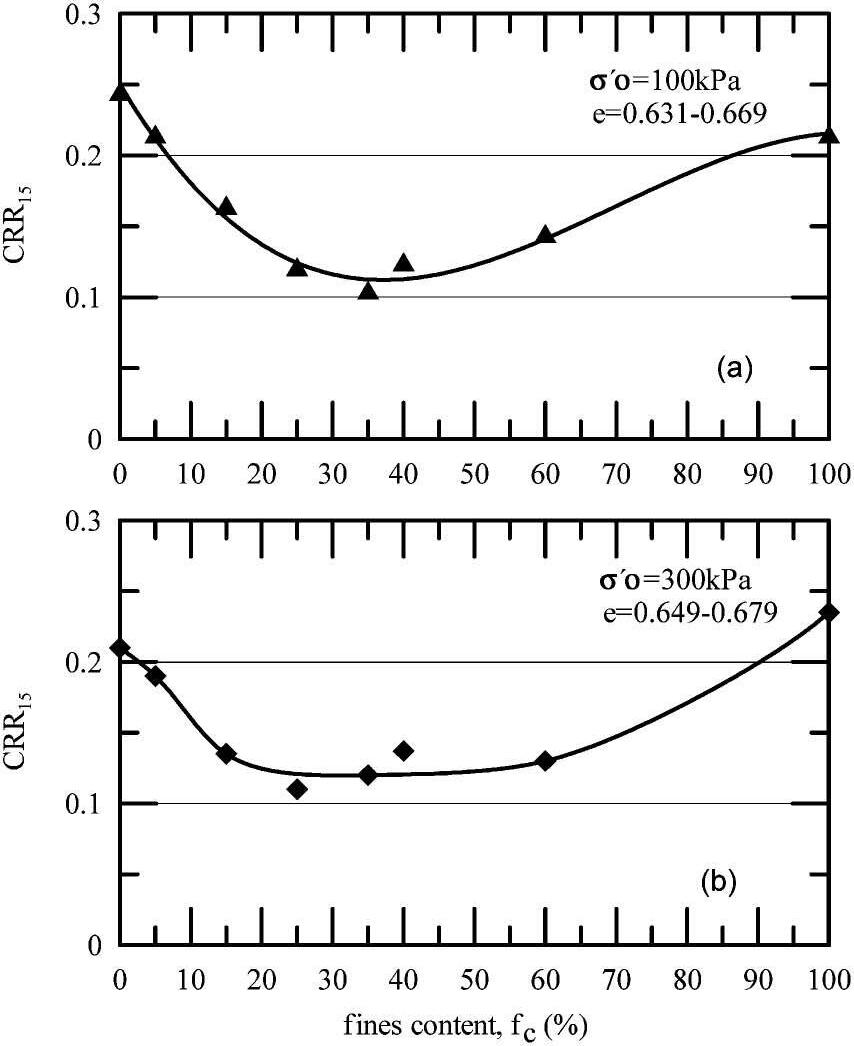

TheeŠectofboth s? o andvoidratioontheCRR15 is showninFig.11.AdecreaseofCRR15 withincreasing voidratioatagiven s? o isobservedforeachtestedmixture.ThevariationoftheCRR15 with fc isshowninFig.

Fig.11.Variationofcyclicresistanceratio,CRR15,withvoidratio, e, forvariousˆnescontents, fc,andat s ? o,(a)50kPa,(b)100kPaand (c)300kPa

12at s? o =100and300kPa.TheresultsinFigs.11and12 showthatonceCRR15 reachesaminimumatathreshold ˆnescontent,itremainsrelativelyconstantthereafter irrespectivelyof fc,unlessthelatterisincreasedsigniˆcantly.Thethresholdˆnescontentisabout35z and 25z at s? o =100and300kParespectively.Thethreshold ˆnescontentat s? o =100kPaisidenticaltothe fcth value, determinedfromthemonotonictests,asdescribedpreviouslyandshowninFigs.3and7.

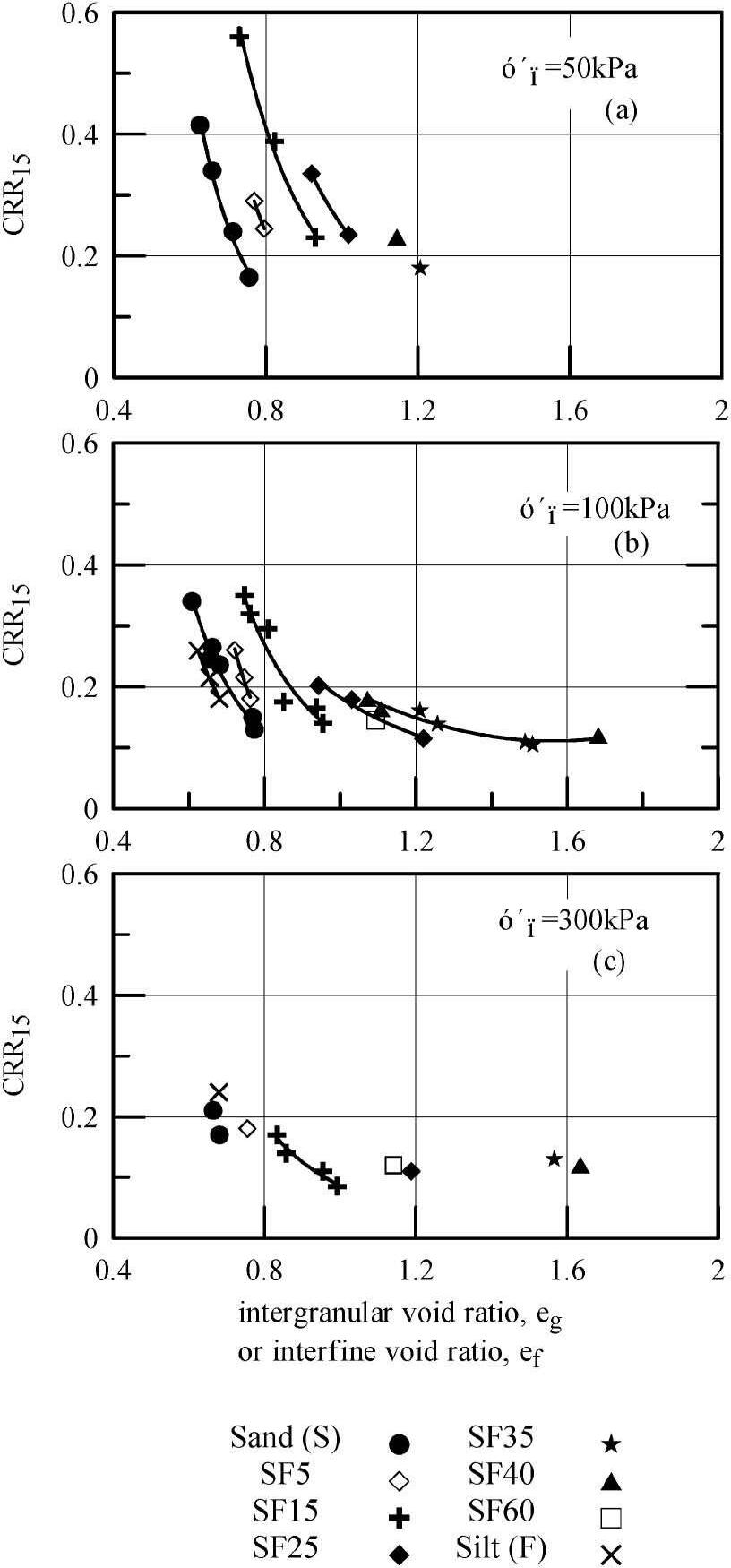

Figure13showsthevariationofCRR15 witheither eg ( fcÃ35z),or ef ( fcÀ35z)ataconstantvalueof s? o.For eachtestedmixture,itisshownthatCRR15 decreaseswith increasing eg or ef value.However,atagiven eg value, CRR15 increaseswithincreasing fc uptothe fcth=35z, (positiveeŠect).Athigher fc values( fcÀ35z),adecrease ofCRR15 withincreasing fc isindicatedatagiven ef value (negativeeŠect).Thismaybeattributedtothefactthatat aconstantvalueof eg,thevoidratioofthemixtures decreaseswithincreasing fc andthustheybecomestrong-

Fig.12.EŠectofˆnescontent, fc onliquefactionresistanceratio, CRR15,atconstantvoidratio, e,at s ? o,(a)100kPaand(b)300kPa

er(Fig.4(a)).Onthecontrary,ataconstantvalueof ef, thevoidratioofthemixturesincreaseswithincreasing fc abovethe fcth valueandtheybecomeweaker(Fig.4(b)).

ThepositiveeŠectofnon-plasticˆnesonCRR15 in termsof eg issimilartothatconsideredinthecorrelation betweenCSRand(N1)60,intheSPTbasedprocedure.As notedpreviously,agivenvalueof(N1)60,correspondsto greaterrelativedensitiesvalues,as fc increases,andthereforetogreatervaluesofCRR15.Similarly,foragiven valueof eg,anincreasein fc correspondstoanincreasein relativedensityandsoinincreasedvaluesofCRR15 (Fig. 4).

TheThresholdFinesContentinRelationtoParticle Packing

Asstatedabove,achangeoftheeŠectofˆnesonboth themonotonicandcyclicbehaviourofthetestedmixtureswasobservedat fcth.ThischangeoftheeŠectof ˆnesonthebehaviourofmixturescanbeexplainedby consideringthealterationoftheirstructurewithincreasing fc.As fc increasesfromzero,ˆnesenterthevoid spacesbetweenthesandgrains,whichareinfullcontact witheachother.Thisholdsuptothe fc atwhichthevoid spacesarecompletelyˆlledwithˆnes,andresultsinan increaseofthedensityofthemixture,withouthowever anyactiveparticipationofˆnesinthetransferofinterparticlecontactstresses.Withfurtherincreasing fc,the sandgrainsstarttoseparate,astheyarepushedslightly apartbytheˆnes,whichstartoccupyingalsolocations betweenthesandgrainsandparticipatinginthetransfer ofinterparticlecontactstresses.Thisisthereasonwhya decreaseof ecs andCRR15 withincreasing fc atagiven valueofvoidratio,isobserved.Thiscontinuesuntilthe

Fig.13.Variationofcyclicresistanceratio,CRR15,withintergranular voidratio, eg (fcÃ35 % )orinterˆne, ef (fcÀ35 % )voidratio

fcth,atwhichthevolumeofˆnesissogreatthatsand grainsaredisplacedfarapartfromeachotherandthey loosecontact.Thebehaviourofˆnesnowcontrolsthe behaviourofthemixture,whichbecomesunstable.As fc increasesbeyond fcth thesandgrainsbecometotallyisolatedandtheˆnesmatrixbecomesstrongerduetotheincreasingdevelopmentofcontactsbetweenˆnesparticles whichcannowtransferlargerinterparticlecontactstresses.Thispatternofbehaviourexplainswhyfor fcÀfcth an increaseof ecs andCRR15 withincreasing fc atagiven valueofvoidratio,isobserved.

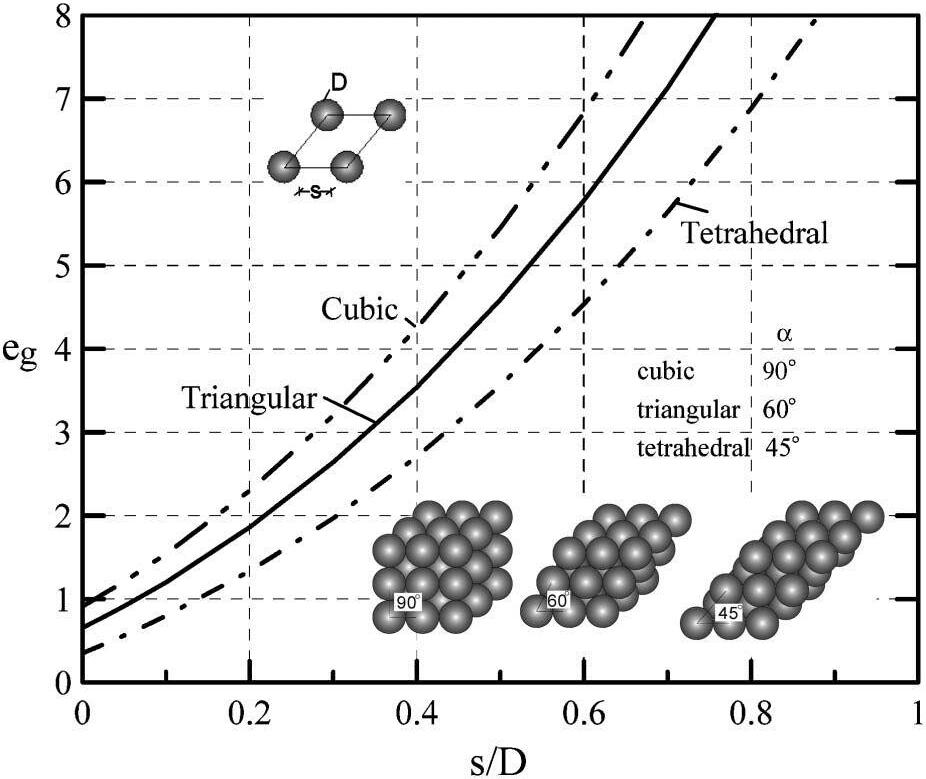

Table3summarizespreviouslaboratoryinvestigations intotheeŠectof fc,eitheronthecriticalstate,oronthe cyclicbehaviourofsand-siltmixturesinwhich fcth wasdeterminedexperimentally.Accordingtothem, fcth varies from35z to50z.Sofar,therehavebeennostudieson howtoestimate fcth onatheoreticalbasis.Considering thepackingofsinglesizesphericalsandparticleswithdiameter, D,ataseparationdistance, s,arelationshipbe-

(4) Foudry0S00sand &crushed silicaˆnes Quartz—0.8000.6080.2502.1000.6270.0100.04032.5

Notation:

(1):ZlatoviácandIshihara(1995),(2a,2b):PolitoandMartin(2001),(3):XenakiandAthanasopoulos(2003),(4):Thevanayagametal.(2002), (5):NaeiniandBaziar(2004),(6):Yangetal.(2006aandb),(7):thisstudy WR:wellrounded,R:rounded,SR:subrounded,SA:subangular,A:angular * asreportedbyVerdugoandIshihara(1996)

** theexactthresholdˆnescontentwasnotdetermined

† asimpliedfromPolitoandMartin(2001)andMulilisetal.(1975)

‡ itwasassumed,asmostofthenaturalsandsinGreececontainfeldspar&micaandhavesubangularparticles

!! theexactthresholdˆnescontentwasnotdetermined.Itisestimatedtobewithintherangeof25z to40z

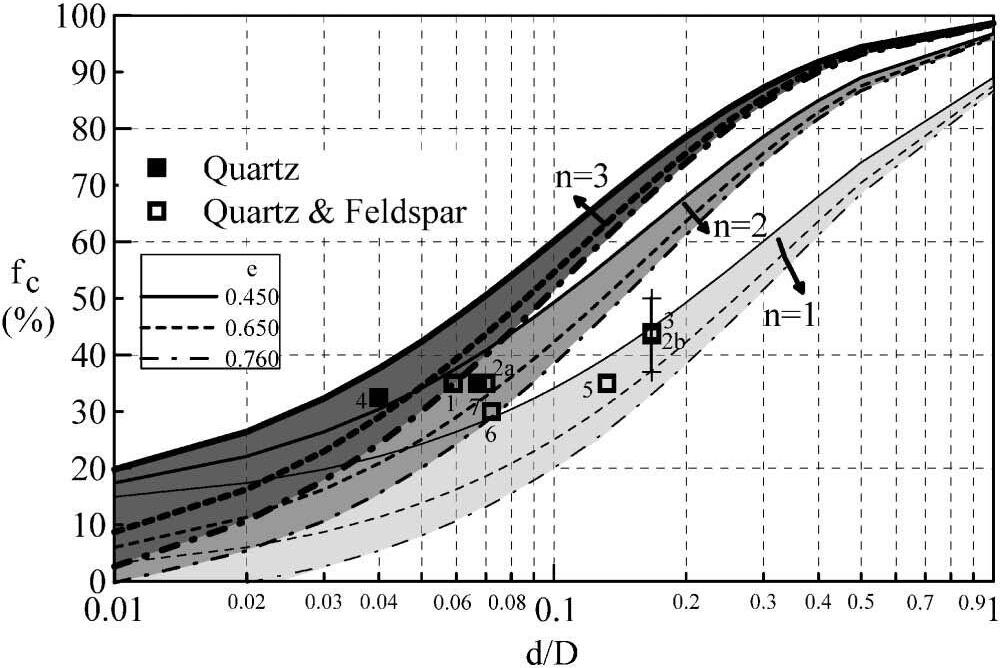

Fig.14.Relationshipbetweenintergranularvoidratio, eg,andtheratiooftheseparationdistancetotheparticlediameter, s/D,forsinglesizesphericalparticles

tween eg andtheratioofseparationdistancetoparticle diameter s/D canbederived,Fig.14: eg =b Ø s D +1 »3 1(6)

where b=1.910,1.654and1.350fortheloosest(cubic), average(triangular)anddensest(tetrahedral)packingof sphericalgrains.Theseparationdistancerepresentsthe thicknessofthelayerofˆnes,whichcanbeinsertedbetweenthesphericalsandgrainsandindicatesthe probabilityofafailurezoneformingwithouttheinterferenceofsandgrains.

WhenmixingsphericalparticlesoftwodiŠerentsizes, theseparationdistanceofthelargesizeparticlesmustbe ntimesthediameterofthesmallparticles,thatis: s D =n・Ø d D » (7)

where D and d arethediametersofthelargeandsmall sizeparticlesrespectively.

Theformationofashearzoneatcriticalstatewouldre-

Fig.15.Relationshipbetweenˆnescontent, fc,andratioofdiameters ofsmalltolargesizeparticles, d/D forthetriangularpacking(The numbersintheˆgureindicatethenumbersofinvestigations,summarizedinTable3)

quirethedisplacementofatleasttwotothreediameters ofthesmallparticles(JeŠeriesandBeen,2006).CombiningEqs.(2),(6)and(7),thefollowingexpressionof fc as afunctionofdiameterratio, d/D,andvoidratiocanbe obtained:

Figure15showsthevariationof fc withthediameterratio, d/D,fortheaverage(triangular)packing, n=1,2 and3andvoidratiovaluesof0.450,0.650and0.760,as wellasthe fcth values,determinedbytheinvestigations summarizedinTable3.InTable3alsothevaluesofthe parameter n,denotedas nth,forwhichthe fc valuesobtainedfromEq.(8),matchedthe fcth determinedbythe investigations,arepresented.Themeandiameterratio, d50/D50 andthesamevoidratioofthemixtures,asreportedinthestudies,wereusedtoestimate fcth.Forallthe sand-siltmixtures,summarizedinTable3,thevaluesof the nth parameterrangefrom1.15to2.30.Theabove resultsshowthatthe fcth dependsmainlyonthevoidratio ofthemixtures,onthemeandiameterratio, d50/D50,as wellasthemineralogyandtheparticleshapecharacteristics,asexpressedbysphericity,angularityandroughness. Feldsparandmicaminerals,encounteredinmanynatural siltysands(cases1–3and5–6inTable3, nth=1.15–2.30), haveplatyshapeandtheirpresencefacilitatestheformationofashearzoneatsmallerseparationdistancesbetweenthesphericalparticles(smaller n values),ascomparedwithquartzsandswithequidimensionalparticles, (cases4and7inTable3, nth=1.60–2.30).

Itshouldbenoted,however,thatthegradingofnaturalsiltysandsisin‰uencedbyseveralotherfactorsinadditiontothoseconsideredaboveforbinarypackingandartiˆcialsand-siltmixtures.Naturalsandshavepractically aninˆnitenumberofparticlediameterswithvarying shapecharacteristicsandmayalsocontainverysmall

Fig.16.Variationofcyclicresistanceratio,CRR15,withstate parameter, c ,forsand-siltmixturesatvariouslevelsofmeaneŠectivestress, s ? o,(a)50kPa,(b)100kPaand(c)300kPa

particleswhosebehaviourisdictatedbytheinteracting surfaceforces.

RelationshipbetweenStateParameterandLiquefactionResistanceRatio

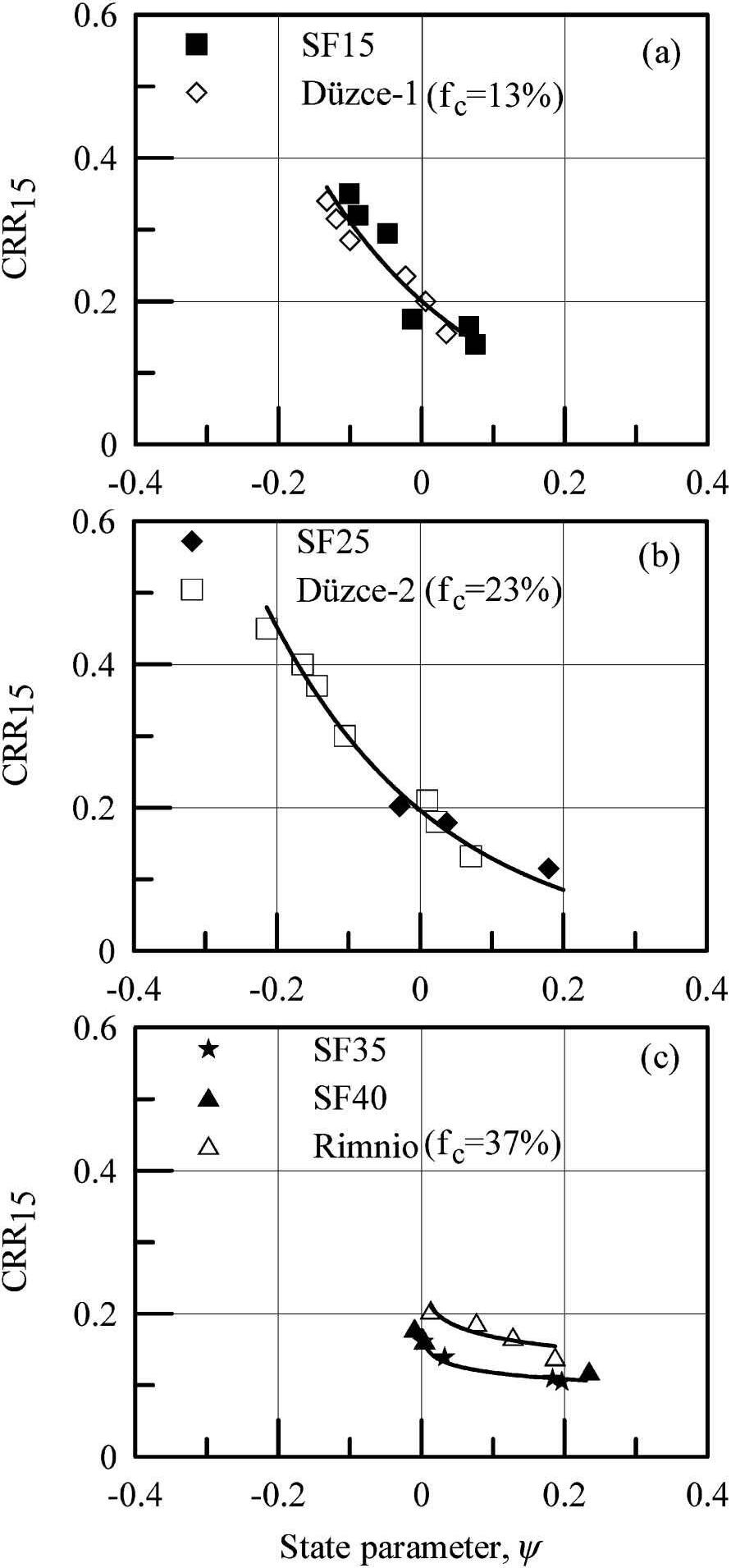

ThevalueofCRR15 ofthetestedsand-siltmixturesis relatedtothestateparameter, c,inFig.16.Foreach testedmixture,adecreaseofCRR15 withincreasingvalue of c isobserved,duetoincreasingcontractivenessofthe soil.Thetestresultsalsoindicatethatfordilativebehaviour(cº0)andloweŠectivestresses(s? o =50kPa),the presenceofˆnesupto25z increasesCRR15 foragiven c.Thismaybeattributedtothefactthatfor fc upto25z besidessand,siltparticlesalsoparticipateintransferring orsustainingtheimposedstresses.However,thiscontributionofsiltparticlesdiminishesprogressivelywithincreasing s? o andat s? o =300kPanoapparenteŠectof fc on therelationbetweenCRR15 and c isobservedforthetestedmixtures.Therearealsoindicationsthatforcontractivebehaviour(cÀ0),at s? o valuesequalorgreaterthan 100kPa,thereisalowerboundvalueofCRR15 ofthe

Fig.17.Criticalstatelinesofnaturalsiltysandsintermsof(a)void ratio, e and(b)intergranularvoidratio, eg

Fig.18.Variationofcyclicresistanceratio,CRR15,with(a)voidratio, e and(b)intergranularvoidratio, eg,atameaneŠectivestress, s ? o =100kPa

Fig.19.Variationofcyclicresistanceratio,CRR15,withstate parameter, c ,atthemeaneŠectivestress, s ? o =100kPa

orderof0.09to0.12independentlyof fc

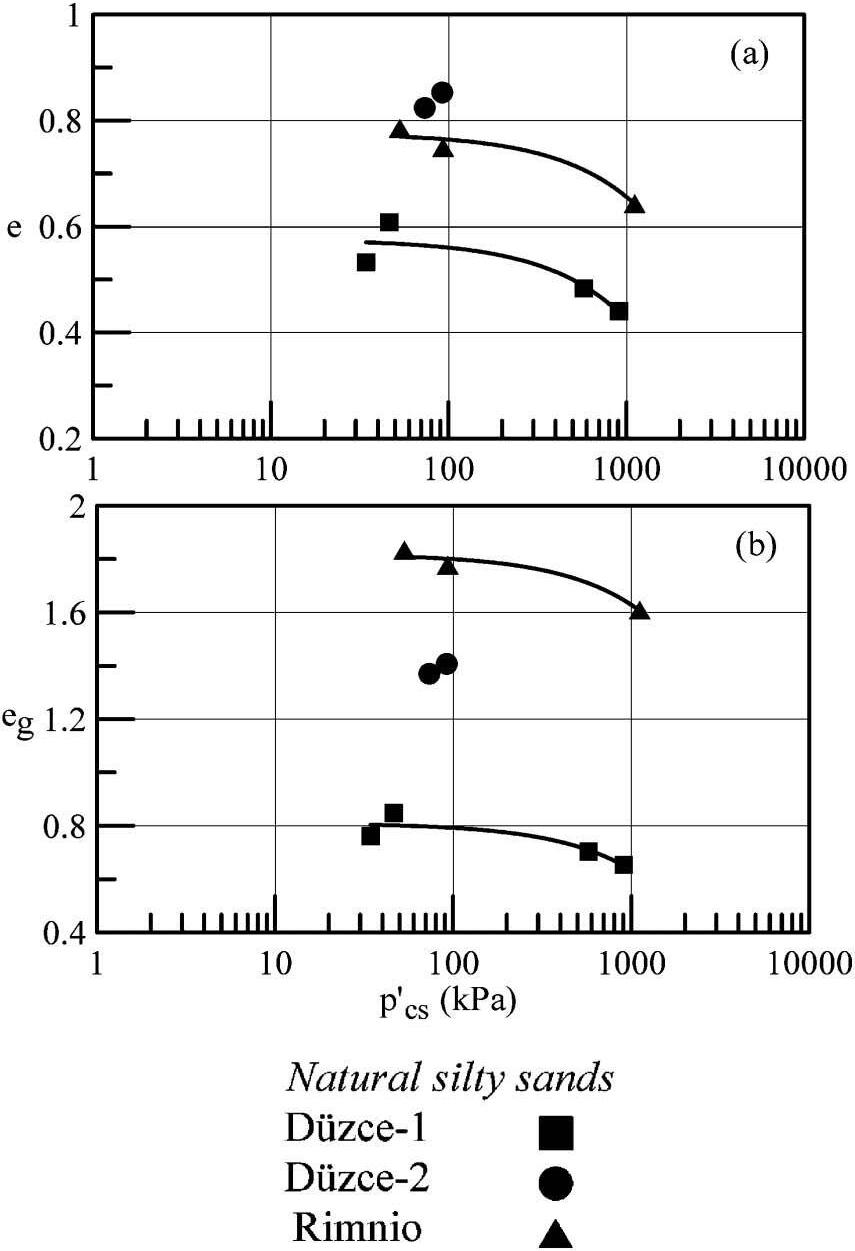

NaturalSiltySands

TheCSLsofthenaturalsiltysandsareshowninFig. 17bothintermsofvoidratioand eg.Thevaluesof parameter Mcs,determinedforDäuzce-1andRimniosoils aregiveninTable2.

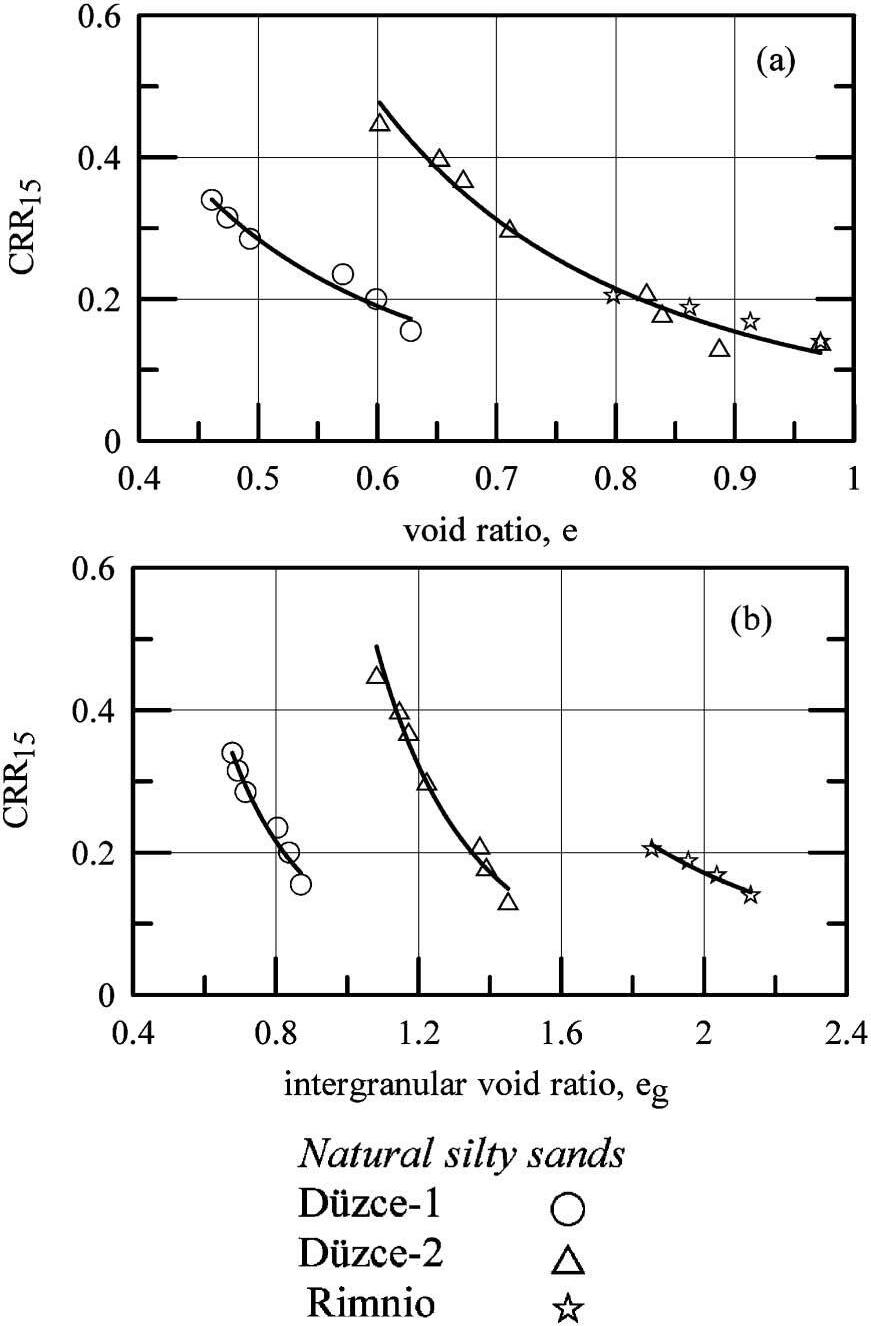

ThevariationoftheirCRR15 withbothvoidratioand eg isshowninFig.18.ThecoincidenceofCRR15 versus voidratiorelationsbetweenDäuzce-1andthesand-silt mixturewith fc =15z andalsobetweenDäuzce-2and Rimniocanbeexplainedbythefactthatthesoilsinboth caseshadsimilarvaluesof emin and emax,Table1andFig. 3.CoincidenceintheCRR15 versus eg relationisobserved onlybetweenDäuzce-1andthesand-siltmixturewith fc = 15z,sincebothsoilshavealsosimilar fc values.

TherelationshipbetweenCRR15 and c fornaturalsoils isshowninFig.19togetherwiththecorresponding resultsforthesand-siltmixtureswithsimilar fc values.A goodagreementisobservedbetweentheresultsfrom Däuzce-1andthecorrespondingfromthesand-siltmixturewith fc =15z,asthesesoilshavebothsimilar emin and emax and fc values.TheagreementoftheresultsbetweenDäuzce-2andthecorrespondingfromthesand-silt mixturewith fc =25z at cÀ0mayberegardedasaccidental,sincethesesoilshavediŠerentphysicalproperties(emin, emax andgradation).ForRimniosiltysand highervaluesofCRR15 atagivenvalueof c weredeterminedthanthecorrespondingforthesand-siltmixtures with fc =35z and40z.ThisdiŠerencemaybeattributed todiŠerencesingradation,mineralogy,andparticle shapecharacteristics.

CONCLUSIONS

Thefollowingconclusionscanbedrawnfromthetest resultsonthesand-siltmixtures:

Drainedandundrainedmonotonictestsproducea uniqueCSLforeachtestedmixture.However,thelocationoftheCSLisdiŠerentforeachmixture.Atlow stresses,theCSLsarenearlyparallelandhaveasmallinclination.WithincreasingmeaneŠectivestresslevel, however,theysteepenandconvergeatstressesabove 1000kPa.TheCSLsmovedownwardswithincreasing fc uptoathresholdvalue, fcth of35z,andthenupwards. When eg or ef isconsidered,theCSLsmoveupwardswith increasing fc upto35z andthendownwards.

Liquefactionresistanceratiodecreaseswithincreasing s? o atagiveneithervoidratio,or eg (or ef)voidratio.The eŠectof s? o onCRR15 diminisheswithincreasing fc.At constantvoidratio,CRR15 decreaseswithincreasing fc up toa fcth andincreasesthereafterwithfurtherincreasing fc Forthetestedsand-siltmixturesthe fcth is35z at s? o =100 kPaandisthesame,asthatdeterminedfromtheCSLs. Theresultsalsoindicatethatthe fcth reduceswithincreasing s? o.Atconstant eg,CRR15 increaseswithincreasing fc upto fcth (positiveeŠect).ThispositiveeŠectofˆneson CRR15 intermsof eg isinagreementwiththatsuggested bythesemi-empiricalproceduresincodesofpractice, whenevaluatingliquefactionpotentialduringearthquakes.

Thevalueof fcth isanimportantparameter,determiningthetransitionfromthesand-dominatedtothesiltdominatedbehaviourofthemixtures.Itisshownthatthe fcth ofsand-siltmixturesisrelatedtotheirparticlepacking.Equation(8)hasbeenproposedfortheestimationof fcth,asafunctionofthevoidratioofthemixture,the meandiameterratio, d50/D50,andtheseparationdistance ofthesandgrainswhichisequalto nth timesthediameter ofsiltparticleswith nth=1.15–2.30.Thecomparisonof the fcth values,predictedbytheaboveequationandthe correspondingdeterminedexperimentallybythisand previousstudies,alsohighlightsthein‰uenceofother parameterson fcth suchasgradation,mineralogyandparticlesshapecharacteristicsofthemixtures,which,

however,arenotconsideredinthesemi-empiricalˆeld basedproceduresforthebehaviourofnaturalsiltysands.

TherelationbetweenCRR15 and c dependsonboth s? o and fc.ThereareindicationsthattheeŠectof fc diminisheswithincreasing s? o,i.e.,at s? o =300kPatheserelations coincideforallmixtures,independentlyof fc andalso thatforcontractivebehaviour(cÀ0)thereisalower boundvalueforCRR15 oftheorderof0.09to0.12forthe testedmixtures.Thebehaviourofnaturalsoilsissimilar tothatofartiˆcialmixtures,onlywhentheyhavesimilar physicalproperties,suchasgradation,mineralogyand particlecharacteristics.

Itisworthnoting,however,thatthein-siturelationshipbetweenliquefactionresistanceratioandstate parametermaybediŠerentfromthatdeterminedin laboratoryduetotheeŠectsofstresshistory,structure (fabricandbonding)andageing.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

TheauthorswouldliketoexpresstheiracknowledgementstotheOnassisPublicBeneˆtFoundation,theState ScholarshipsFoundationofGreeceandtheGeneral SecretaryofResearchandTechnology,Greece,forthe ˆnancialsupportoftheˆrstauthor.Thetestsonthesoils fromDäuzcewereperformedwithintheMarmaraEarthquakeRehabilitationProject(MERP).

REFERENCES

1)ASTMD4253: StandardTestMethodsforMaximumIndexDensityofSoilsUsingaVibratoryTable,AmericanSocietyofTesting andMaterials,U.S.A.

2)ASTMD4254: StandardTestMethodsforMinimumIndexDensity andUnitWeightofSoilsandCalculationofRelativeDensity, AmericanSocietyofTestingandMaterials,U.S.A.

3)Amini,F.andQi,Z.G.(2000):Liquefactiontestingofstratiˆedsiltysands, J.Geotech.andGeoenvr.Engrg.,ASCE, 126(3), 208–217.

4)Been,K.andJeŠeries,M.G.(1985):Astateparameterforsands, Gáeotechnique, 41(3),365–381.

5)Boulanger,R.W.(2003):HighoverburdenstresseŠectsinliquefactionanalyses, J.Geotech.andGeoenvr.Engrg.,ASCE, 129(12), 1071–1082.

6)Casagrande,A.(1936):CharacteristicsofcohesionlesssoilaŠecting thestabilityofslopesandearthˆlls, J.BostonSoc.CivilEngrg., 13–32.

7)Cubrinonski,M.andIshihara,K.(2002):Maximumandminimum voidratiocharacteristicsofsands, SoilsandFoundations, 42(6), 65–78.

8)Eurocode8-EN1998: DesignofStructuresforEarthquake Resistance,Part5:Foundations,retainingstructuresandgeotechnicalaspects.

9)Idriss,I.M.andBoulanger,R.W.(2004):Semi-empiricalproceduresforevaluatingliquefactionpotentialduringearthquakes, Proc.11thInt.Conf.onSoilDyn.andEarth.Engrg.-3rdInt. Conf.onEarth.Geotech.Engrg.

10)Ishihara,K.(1996): SoilBehaviourinEarthquakeGeotechnics, ClarendonPressOxford,NewYork,U.S.A.,227.

11)JeŠeries,M.andBeen,K.(2006): SoilLiquefaction-ACriticalState Approach,TaylorandFrancis,London.

12)Ladd,R.S.(1978):Preparingtestspecimensusingundercompaction, Geotech.Test.J.,GTJODJ, 1(1),16–23.

13)Mitchell,J.K.(1975):Fundamentalsofsoilbehavior, JohnWiley

andSons,Inc.,NewYork,U.S.A.,1stEdition.

14)Miura,S.,Yagi,K.andKawamura,S.(1995):Liquefaction damageofsandyandvolcanicgroundsinthe1993HokkaidoNansei-Okiearthquake, Proc.3rdInt.Conf.onRec.Adv.inGeotech. Earth.Engrg.andSoilDyn., 3.06,193–196.

15)Mulilis,J.P.,Chan,C.K.andSeed,H.B.(1975):TheeŠectsof methodofsamplepreparationonthecyclicstress-strainbehaviour ofsands, EERCReport,(75–18).

16)Naeini,S.A.andBaziar,M.H.(2004):EŠectofˆnescontenton steady-statestrengthofmixedandlayeredsamplesofasand, Soil Dyn.andEarth.Engrg., 24(3),181–187.

17)NationalCenterforEarthquakeandEngineeringResearch (NCEER)(1997): Proc.NCEERWorkshoponEvaluationofLiquefactionResistanceofSoils,ReportNo.NCEER–97–0022, Youd,L.T.andIdriss,I.M,6,62,64.

18)Papadopoulou,A.I.(2008):Laboratoryinvestigationintothebehaviourofsiltysandsundermonotonicandcyclicloading, Ph.D Thesis,AristotleUniversityofThessaloniki,Greece.

19)Pillai,V.S.andMuhunthan,B.(2001):Areviewofthein‰uenceof initialstaticshear(Ka)andconˆningstress(Ks)onfailuremechanismsandearthquakeliquefactionofsoils, Proc.4thInt.Conf.on Rec.Advn.Geotech.Earth.Engrg.andSoilDyn.,SanDiego, California, 1.51

20)Polito,C.P.andMartin,J.R.(2001):EŠectsofnonplasticˆneson theliquefactionresistanceofsands, J.Geotech.andGeoenvir. Engrg.,ASCE, 127(5),408–415.

21)Roscoe,K.H.,Schoˆeld,A.N.andWroth,C.P.(1958):Onthe yieldingofsoils, Gáeotechnique, 8(1),22–53.

22)Schoˆeld,A.N.andWroth,C.P.(1968): CriticalStateSoil Mechanics,Mc-GrawHill,London.

23)Seed,H.B.,Tokimatsu,K.,Harder,L.F.andChung,R.M. (1985):Thein‰uenceofSPTproceduresinsoilliquefaction resistanceevaluations, J.Geotech.Engrg., 111(12),1425–1445.

24)Skempton,A.K.(1986):Standardpenetrationtestproceduresand theeŠectsinsandsofoverburdenpressure,relativedensity,particle

size,agingandoverconsolidation, Gáeotechnique, 36(3),425–447.

25)Thevanayagam,S.,Fiorillo,M.andLiang,J.(2000):EŠectofnonplasticˆnesonundrainedcyclicstrengthofsiltysands, SoilDynamicsandLiquefaction,77–91.

26)Thevanayagam,S.andMohan,S.(2000):Intergranularstatevariablesandstress-strainbehaviourofsiltysands, Gáeotechnique, 50(1), 1–23.

27)Thevanayagam,S.,Shenthan,T.,Mohan,S.andLiang,J.(2002): Undrainedfragilityofcleansands,siltysandsandsandysilts, J. GeotechandGeoenvir.Engrg.,ASCE, 128(10),849–859.

28)Tika,T.andPitilakis,K.(1999):PerformanceofRimniobridge embankmentduringthe1995Kozani-Grevenaearthquake, Proc. 12thEuropeanConf.onSMGE,TheNetherlands, 2,857–862.

29)Troncoso,J.H.andVerdugo,R.(1985):Siltcontentanddynamic behavioroftailingsands, Proc.12thICSMFE,SanFrancisco, U.S.A.,1311–1314.

30)Vaid,V.P.(1994):Liquefactionofsiltysoils, GroundFailuresunderSeismicConditions,GeotechnicalSpecialPublication,(44), ASCE,1–16.

31)Verdugo,R.andIshihara,K.(1996):Thesteadystateofsandy soils, SoilsandFoundations, 36(2),81–91.

32)Xenaki,V.C.andAthanasopoulos,G.A.(2003):Liquefaction resistanceofsand-siltmixtures:anexperimentalinvestigationof theeŠectofˆnes, SoilDynamicsandEarth.Engrg., 23,183–194.

33)Yang,S.,Sandven,R.andGrande,L.(2004):Instabilityofloose sand-siltmixtures, Proc.11thInt.Conf.onSoilDynamicsand Earth.Engrg.-3rdInt.Conf.onEarth.Geotech.Engrg.,Berkeley, California,U.S.A.

34)Yang,S.,Sandven,R.andGrande,L.(2006):Steady-statelinesof sand-siltmixtures, Can.Geotech.J., 43,1213–1219.

35)Zlatoviác,S.andIshihara,K.(1995):Onthein‰uenceofnonplastic ˆnesonresidualstrength, Proc.1stInt.Conf.onEarth.Geotech. Engrg.,14–16November1995(eds.byK.Ishihara,A.A.Balkema),Rotterdam,TheNetherlands,239–244.