ThalamusModulatesConsciousness viaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex

MichelleJ.Redinbaugh,1,* JessicaM.Phillips,1 NiranjanA.Kambi,1 SounakMohanta,1 SamanthaAndryk,1 GavenL.Dooley,1 MohsenAfrasiabi,1 AeyalRaz,2,3,5 andYuriB.Saalmann1,4,5,6,* 1DepartmentofPsychology,UniversityofWisconsin-Madison,Madison,WI53706,USA 2DepartmentofAnesthesiology,RambamHealthCareCampus,Haifa3109601,Israel 3RuthandBruceRappaportFacultyofMedicine,Technion–IsraelInstituteofTechnology,Haifa3200003,Israel 4WisconsinNationalPrimateResearchCenter,Madison,WI53715,USA

5Theseauthorscontributedequally

6LeadContact

*Correspondence: mredinbaugh@wisc.edu (M.J.R.), saalmann@wisc.edu (Y.B.S.) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.005

SUMMARY

FunctionalMRIandelectrophysiologystudiessuggestthatconsciousnessdependsonlarge-scale thalamocorticalandcorticocorticalinteractions. However,itisunclearhowneuronsindifferent corticallayersandcircuitscontribute.Wesimultaneouslyrecordedfromcentrallateralthalamus (CL)andacrosslayersofthefrontoparietal cortexinawake,sleeping,andanesthetized macaques.Wefoundthatneuronsinthalamus anddeepcorticallayersaremostsensitiveto changesinconsciousnesslevel,consistentacross differentanestheticagentsandsleep.Deep-layer activityissustainedbyinteractionswithCL. Consciousnessalsodependsondeep-layerneuronsprovidingfeedbacktosuperficiallayers (nottodeeplayers),suggestingthatlong-range feedbackandintracolumnarsignalingareimportant.Toshowcausality,westimulatedCLin anesthetizedmacaquesandeffectivelyrestored arousalandwake-likeneuralprocessing.This effectwaslocationandfrequencyspecific.Our findingssuggestlayer-specificthalamocortical correlatesofconsciousnessandinformhowtargeteddeepbrainstimulationcanalleviatedisordersofconsciousness.

INTRODUCTION

Consciousnessisthecapacitytoexperienceone’senvironment andinternalstates.Theminimalmechanismsthataresufficient forthisexperience,theneuralcorrelatesofconsciousness (NCC),aremuchdebated(DehaeneandChangeux,2011;Friston,2010;Lamme,2006;Oizumietal.,2014).Nonetheless,majortheoriesofconsciousnessemphasizetheimportanceof recurrentactivityandinteractionbetweenneurons.Thiscan taketheformofcommunicationbetweenbrainareasalong

feedforwardandfeedbackpathwaysandintracolumnar communicationwithinacorticalarea.

Feedforwardpathwayscarrysensoryinformationfromsuperficiallayerstosuperficialandmiddlelayersofhigher-order corticalareas,whereasfeedbackpathwayscarryprioritiesand predictionsfromdeeplayerstoeithersuperficialordeeplayers oflower-ordercorticalareas(Markovetal.,2014;Mejiasetal., 2016).Reportsofthecontributionoffeedforward(Maksimow etal.,2014;Sandersetal.,2018;vanVugtetal.,2018)and feedback(Bolyetal.,2011;Leeetal.,2009,2013;Razetal., 2014;Uhrigetal.,2018)pathwaystoconsciousnesshavevaried. However,previousstudiesdidnothavethespatialresolution todeterminetransmissionalongpathsbetweenspecific layers—inparticular,whetherfeedbackpathstosuperficialor deepcorticallayers,orboth,contributetoconsciousness.

Availableevidencesuggeststhatchangesinthelevelof consciousnessdifferentiallyinfluencesactivityincortical layers.Non-rapideyemovement(NREM)sleepreducesspiking activityindeeplayersoftheprimaryvisualcortex(V1)inmice andcats(LivingstoneandHubel,1981;Senzaietal.,2019),as wellasinteractionsbetweenthesuperficialanddeeplayers ofV1(Senzaietal.,2019).NREMsleepinmice(Funketal., 2016)andisofluraneanesthesiainferrets(Sellersetal.,2013) alsochangeslocalfieldpotentials(LFPs)differentiallyacross layers.Itisunclearhowchangesinconsciousnessinfluence individualneuronsacrosslayers,andtheirinteraction,inthe higher-ordercortex.

Reciprocallyconnectedwiththehigher-ordercortex,higherorderthalamicareasfacilitatecorticalcommunication(Saalmannetal.,2012;Schmittetal.,2017;Theyeletal.,2010)and couldthusplayaroleinmodulatingcorticocorticalinteraction acrossdifferentconsciousstates.Changesinconsciousness levelbroadlyinfluencethalamicactivityandthalamocortical interactions(Bakeretal.,2014;Contrerasetal.,1997;Jones, 2009;Llina ´ setal.,1998).However,thecentrallateralthalamus (CL)mayhaveaspecialrelationtoconsciousness.CLdamage islinkedtodisordersofconsciousness(Schiff,2008).Anatomically,CLreceivesinputfromthebrainstemreticularactivating system.Italsoprojectstosuperficiallayersandreciprocally connectswithdeeplayersofthefrontoparietalcortex(Kaufman andRosenquist,1985;PurpuraandSchiff,1997;Townsetal.,

1990).Thus,CLiswellpositionedtoinfluenceinformationflow betweencorticallayersandareas.Deepbrainstimulationof thecentralthalamusincreasedresponsivenessinaminimally consciouspatient(Schiffetal.,2007),andcentralthalamic stimulationimprovedtheperformanceofavigilancetaskin healthymacaques(Bakeretal.,2016).Althoughthalamocortical mechanismsofsucheffectshavebeenproposed(Jones,2009; Llinasetal.,1998;PurpuraandSchiff,1997),experimental evidenceislacking.Basedonitsconnectivity,wehypothesized thatCLinfluencesfeedforward,feedback,andintracolumnar corticalprocessestoregulateinformationflow,andthus, consciousness.

ToresolvethecontributionsofcorticocorticalandthalamocorticalpathstotheNCC,weusedlinearmulti-electrode arraystorecordspikesandLFPssimultaneouslyfromthe rightfrontaleyefield(FEF);thelateralintraparietalarea(LIP; frontoparietalareasimplicatedinawareness)(Wardaketal., 2002,2006);andinterconnectedCLintwomacaquesduring task-freewakefulness,NREMsleep,andgeneralanesthesia (isoflurane,propofol).Aftercharacterizingthalamocortical networkactivityunderanesthesia,weelectricallystimulated thethalamus,reliablyinducingarousal.Wereportlayer-specific NCCinfrontoparietalcortexandcortico-CLpathways.

RESULTS

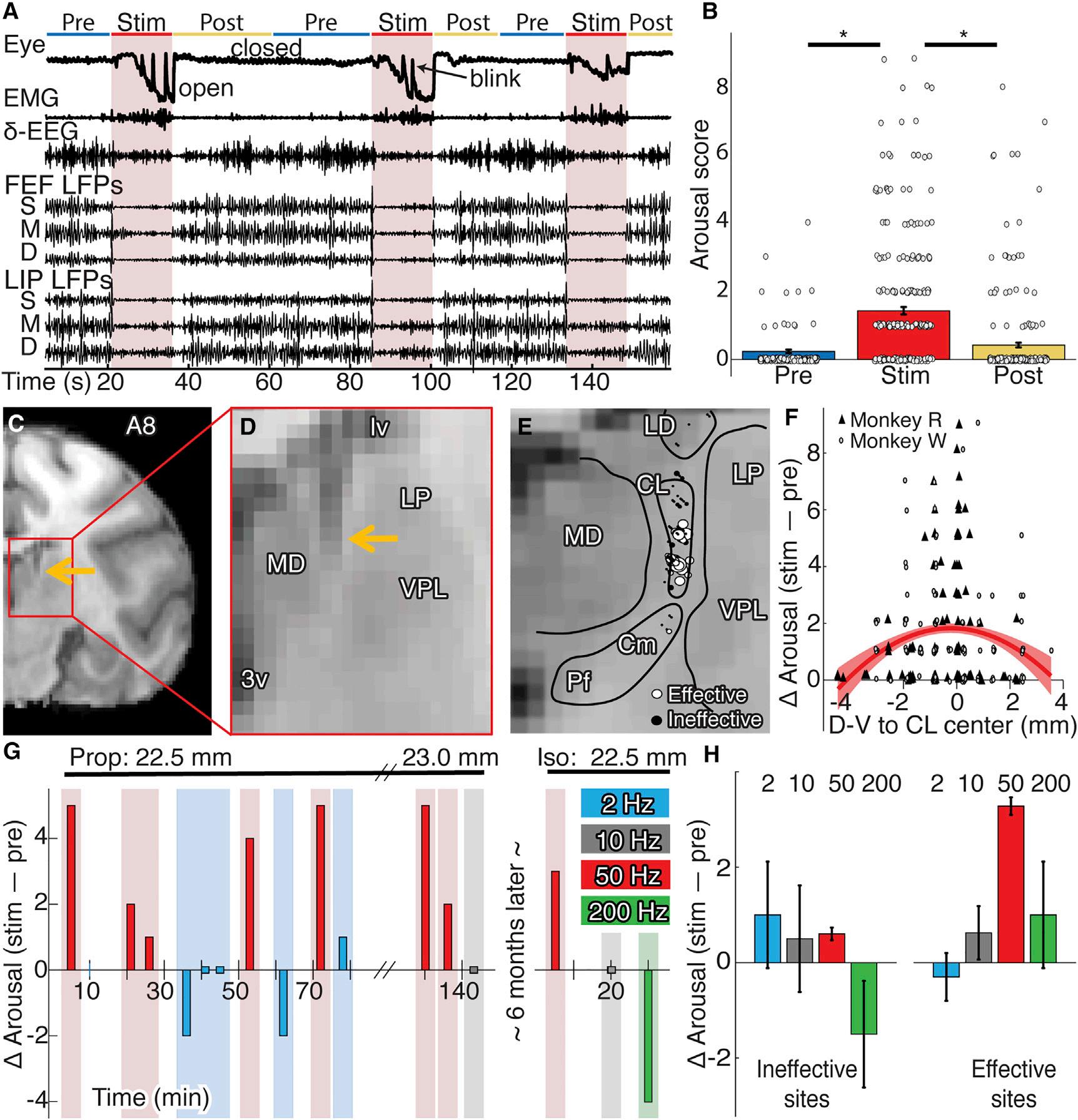

Gamma-FrequencyCLStimulationIncreased ConsciousnessLevel

Aftermaintainingstableanesthesia(arousalscore0–1)forat least2hwhilerecordingneuralactivity,weevaluatedthe signsofarousalbefore,during,andafterstimulationusinga customizedscalesimilartoclinicalmetrics(STARMethods) andperformedstatisticalanalysesusinggenerallinearmodels (STARMethods; TablesS1–S4).Across261stimulationblocks, thalamicstimulationsignificantlyincreasedarousalrelativeto pre-(F=119.28,n=261,p<1.0 3 10 10)andpost-conditions (F=124.64,n=261,p<1.0 3 10 10),evenwhenaccounting fordifferencesindoseandanesthetic(Figures1A,1B,and S1A–S1C).Behavioralchanges(Figure1A)weretimelockedto stimulation:monkeysopenedtheireyeswithwake-like occasionalblinks,performedfullreachesandwithdrawals withforelimbs(ipsi-orcontralateral),madefacialandbody movements,showedincreasedreactivity(palpebralreflex, toe-pinchwithdrawal),andhadalteredvitalsigns(respiration rate,heartrate).Thereconstructionofelectrodetracks placedeffectivestimulations(arousalscore R 3)nearthecenter ofCL(Figures1C–1F).Euclidianproximityofthestimulation arraytoCLsignificantlypredictedchangesinarousal(Figures S1G–S1I;T= 3.39,n=225,p=0.00082);whensystematically varyingarraydepth,proximitytotheCLcentershoweda significantquadraticrelationwitharousal(T= 2.92,n=225, p=0.00393; Figures1Fand S1D–S1F).Effectivestimulation sitesremainedsoonseparaterecordingdaysandwithdifferent anesthetics(Figure1G).Stimulationeffectivenessdepended onfrequency(Figures1Gand1H).Ateffectivesites,only 50-Hzstimulationsreliablyincreasedarousal(T=3.91,n=44, p=0.00035).TheseresultsshowthatCLstimulationcan rouseanimalsfromstable,anesthetizedstates.Thisallowedus

tozeroinonNCCs,identifiedhereasactivitydifferencesbetweenwakefulnessandanesthesia,whichareselectively restoredbyeffective(arousalscore R 3,n=55,mean=4.70, SD=1.70)relativetoineffective(arousalscore<3,n=171, mean=0.77,SD=0.74)50-Hzstimulations.

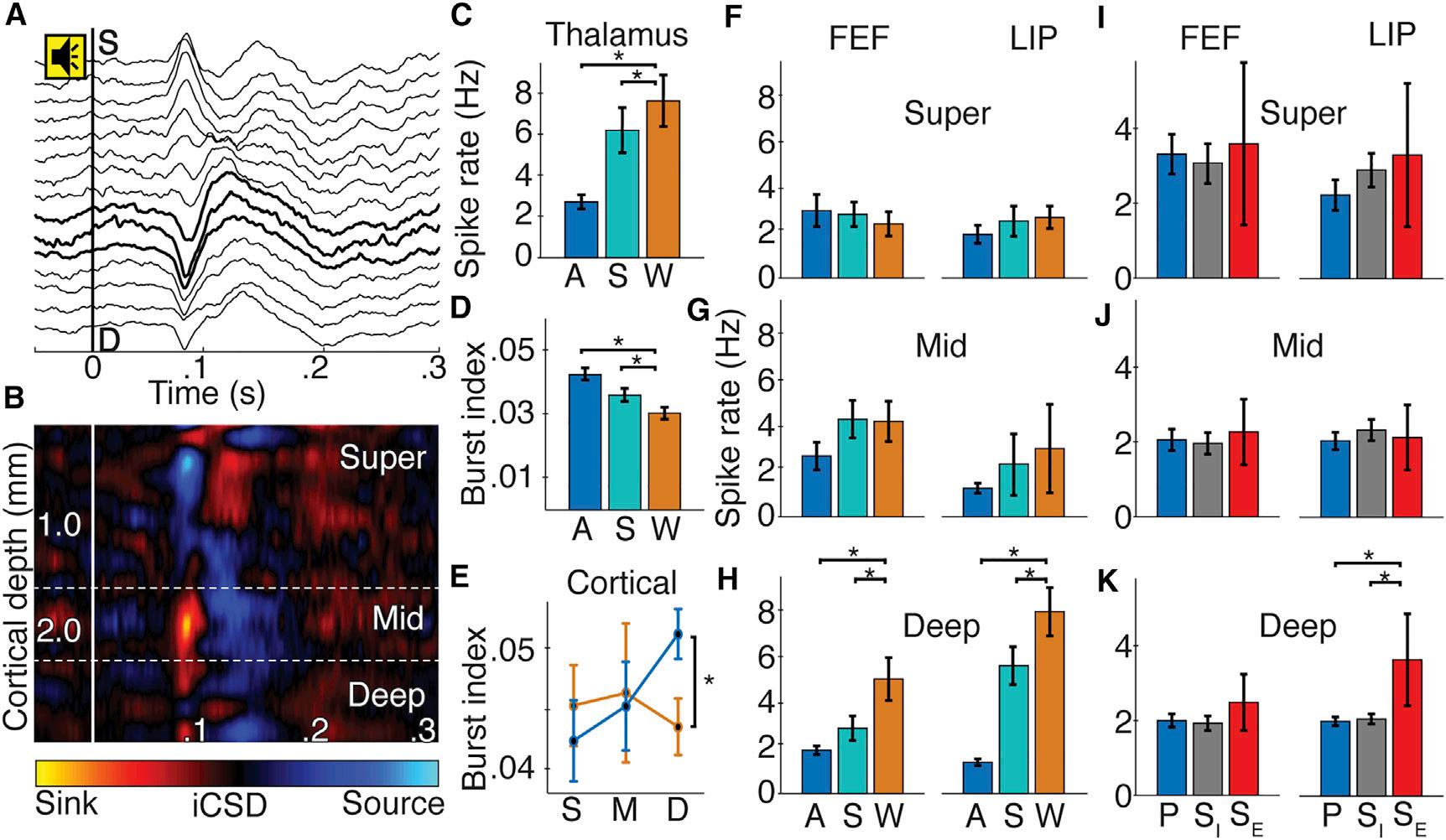

ConsciousnessLevelModulatedSpikeRateandTiming inDeepCorticalLayersandCL Werecorded845neuronsacross3brainareas(FEF,LIP,CL) during4states(wake,sleep,isoflurane,propofol; Figure2). Wakeandanesthesiadataderivedfromseparatesessions, whereasthesameneuronsyieldedsleepandwakedata.This includedasubsetofCLneuronswitharelativelyhighfiring rate( 40–50Hz; FiguresS2EandS2F),similartoneuronsreportedincats(GlennandSteriade,1982;Steriadeetal.,1993). Thalamicneuronsshowedstate-dependentspikerateand burstingactivity(Figures2Cand2D).CLneuronsrecorded duringanesthesia(T= 4.67,n=282,p=3.0 3 10 5)and NREMsleep(F=16.40,n=83,p=0.001)hadsignificantly lowerspikeratesthanduringwakefulness.Isofluraneand propofoleffectswerenotsignificantlydifferent(FigureS2A). Relativetowakefulness,CLneuronsalsoincreasedbursting duringanesthesia(Figures2Dand S2G;T=2.27,n=172,p= 0.024)andsleep(F=7.11,n=121,p=0.0095).

Welocalizedcorticalneuronstosuperficial,middle,or deeplayersusingcurrentsourcedensity(CSD)responses tosoundsinthepassiveoddballparadigm(Figures2Aand 2B).Onlydeepneuronsshowedstate-dependentactivity (Figures2E–2H).Firingratesduringsleepweresignificantly lowerthanwakefulness;thestate-by-layerinteractionwas significantinbothFEF(F=15.17,n=101,p=0.008)andLIP (F=7.70,n=98,p=0.031).Similarly,firingratesduring anesthesiawerelowerthanduringwakefulness;state-by-layer interactionsinFEF(T=3.05,n=281,p=0.013)andLIP(T= 3.79,n=282,p=0.001)weresignificant.Onlydeepneurons increasedburstingduringanesthesia,evidencedbysignificant state-by-layerinteraction(Figure2E;T=2.12,n=285,p= 0.035).Isofluraneandpropofolyieldedsimilarresults(Figures S2B–S2D).Effective50-Hzthalamicstimulationcountered anesthesiaeffectsindeepcorticallayersoftheLIP(Figures2I–2K);the4-wayinteractionofstimulationepoch,effectiveness, layer,andareawassignificant(F=5.19,n=167,p=0.023). Overall,stateswithhigherconsciousnesslevels(stimulationinducedarousal,wakefulness)showedincreaseddeepcortical andthalamicactivities,suggestingaroleintheNCC.

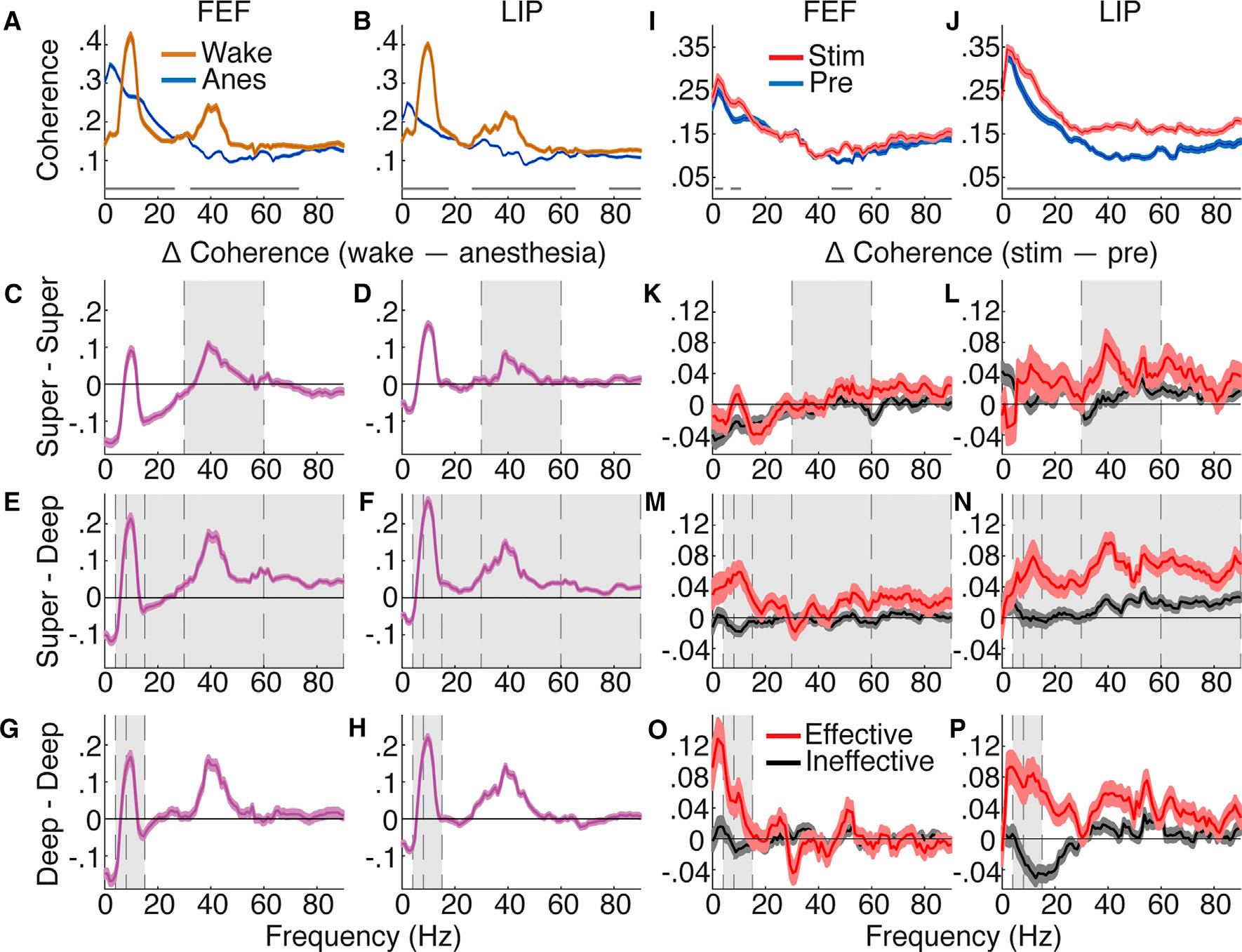

IntracolumnarInteractionsShowedLayer-SpecificNCC Tomeasurestate-relatedchangesinthalamocorticaland corticocorticalcommunication,wecalculatedpowerandcoherenceusingbipolarderivatizedLFPs.Wecombineddata acrossanesthetics,aseffectswerequalitativelysimilar(Figures S2H–S2Oand S4A–S4H).Wefocushereonintracolumnar changes,particularlycoherencewithinsuperficiallayers, deeplayers,andbetweensuperficialanddeeplayersofthe samecorticalarea.Coherencechangedmarkedlybetween wakefulnessandanesthesia;anesthesiaincreaseddeltacoherence(<4Hz)andreducedalpha(8–15Hz)andlowgamma coherence(30–60Hz; Figures3Aand3B; TableS1 forcomplete

Figure1.Gamma-FrequencyCLStimulationIncreasedConsciousnessLevel

(A)Examplebehavioralandneuralrecordingsduring50-Hzstimulation(arousalscore5).

(B)Populationmeanarousalscore(±SE)before,during,andafterstimulationsforbothmonkeys(circlesshowindividualstimulationevents).

(C)Coronalsectionofrighthemisphere8mmanteriortointerauralline(A8).Thearrowshowstheelectrode. (D)Magnifiedviewofthethalamus.

(E)StimulationsitesinmonkeyR(n=90)collapsedalongtheA-Paxis.Circlesrepresentthemiddlecontactinthestimulationarray;diameterscales withinduced arousal.

(F)Stimulation-inducedarousalchange(scoreduringstim–pre)asafunctionofthedorsal-ventraldistancefromCLcenter.Symbolsshowstimulationeventsby monkey;theredcurveshowsthequadraticfit(±SE).

(G)Exampleofstimulationseriesfordifferentfrequenciesduringpropofol(left)andisoflurane(right)atthesamesite22.5mmventraltothecorticalsurface.

(H)Populationmeanarousalchange(±SEofpointestimate)fordifferentstimulationfrequenciesateffectiveandineffectivesitesfrombothmonkeys.

statistics).Wake-anesthesiadifferenceswereconsistentbetweendifferentlayersofFEFandLIP(Figures3C–3H)and qualitativelysimilartodifferencesbetweenwakefulnessand NREMsleep(FigureS2).Notably,coherencebetweensuperficial anddeeplayersofbothcorticalareasshowedsubstantial decreasesinallhigher-frequency(>4Hz)communicationduring anesthesia(T R 10.05,n=8,725,p<1.0 3 10 10; Figures3E and3F; TableS1),suggestingalteredprocessingincortical microcircuits.

Effective50-Hzthalamicstimulationincreasedintracolumnar coherencedifferentiallyacrossfrequencybandsandlayers (Figures3K–3P; TableS1 forcompletestatistics).Coherence withinsuperficiallayerswasincreasedforeffectivecompared toineffectivestimulationsatlowgamma(Figures3Kand3L),

106,1–10,April8,2020 3 Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Redinbaughetal.,ThalamusModulatesConsciousnessviaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex,Neuron(2020),https://

Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Redinbaughetal.,ThalamusModulatesConsciousnessviaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex,Neuron(2020),https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.005

Figure2.ConsciousnessLevelModulatedSpikeRateandTiminginDeepCorticalLayersandCL (A)Exampleofsound-alignedevokedpotentialsfromlinearmulti-electrodearrayinFEF.Toneonsetat0s.BoldlinesshowinverseCSD(iCSD)-defined middlelayers. (B)Sound-alignediCSDcorrespondingto(A).

(CandD)PopulationCLspikerate(±SE)(C)andCLburstindex(±SE)(D)foranesthesia(blue),sleep(teal),andwake(orange)states;*p<0.05.

(E)Cortical(FEFandLIP)burstindex(±SE)insuperficial(S),middle(M),anddeep(D)layersforwakefulness(orange)andanesthesia(blue).

(F–H)Superficial(F),middle(G),anddeep(H)layerspikerates(±SE)inFEFandLIPacrossstates.

(I–K)Superficial(I),middle(J),anddeep(K)spikerates(±SE)inFEFandLIPduringeffectivestimulation(SE,red),ineffectivestimulation(SI,gray),andprestimulation(P,blue).

showingasignificantinteractionbetweenstimulationand effectiveness(T=5.24,n=2,387,p=1.8 3 10 6).Withindeep layers(Figures3Oand3P),similarinteractionsshowthateffectivestimulationsselectivelyincreasedcoherenceattheta(4–8Hz,T=9.04,n=2,183,p<1.0 3 10 10)andalpha(T= 11.79,n=2,183,p<1.0 3 10 10)frequencies.Importantforintracolumnarprocessing,superficialanddeeplayersshowed broadbandcoherenceincreasesselectiveforeffectivestimulationsatthesamefrequencieshinderedbygeneralanesthesia (bands>4Hz;T R 4.83,n=2,631,p % 1.3 3 10 6;see Table S1).Notethatpowerchangesduringthalamicstimulationdid notcorrelatewithcoherencechanges(FiguresS3K–S3P; Table S2 forcompletestatistics),nordidpowerchangesreflectbehavioralarousalduringstimulation.

ThalamocorticalandCorticocorticalInteractions

ShowedPathway-SpecificNCC

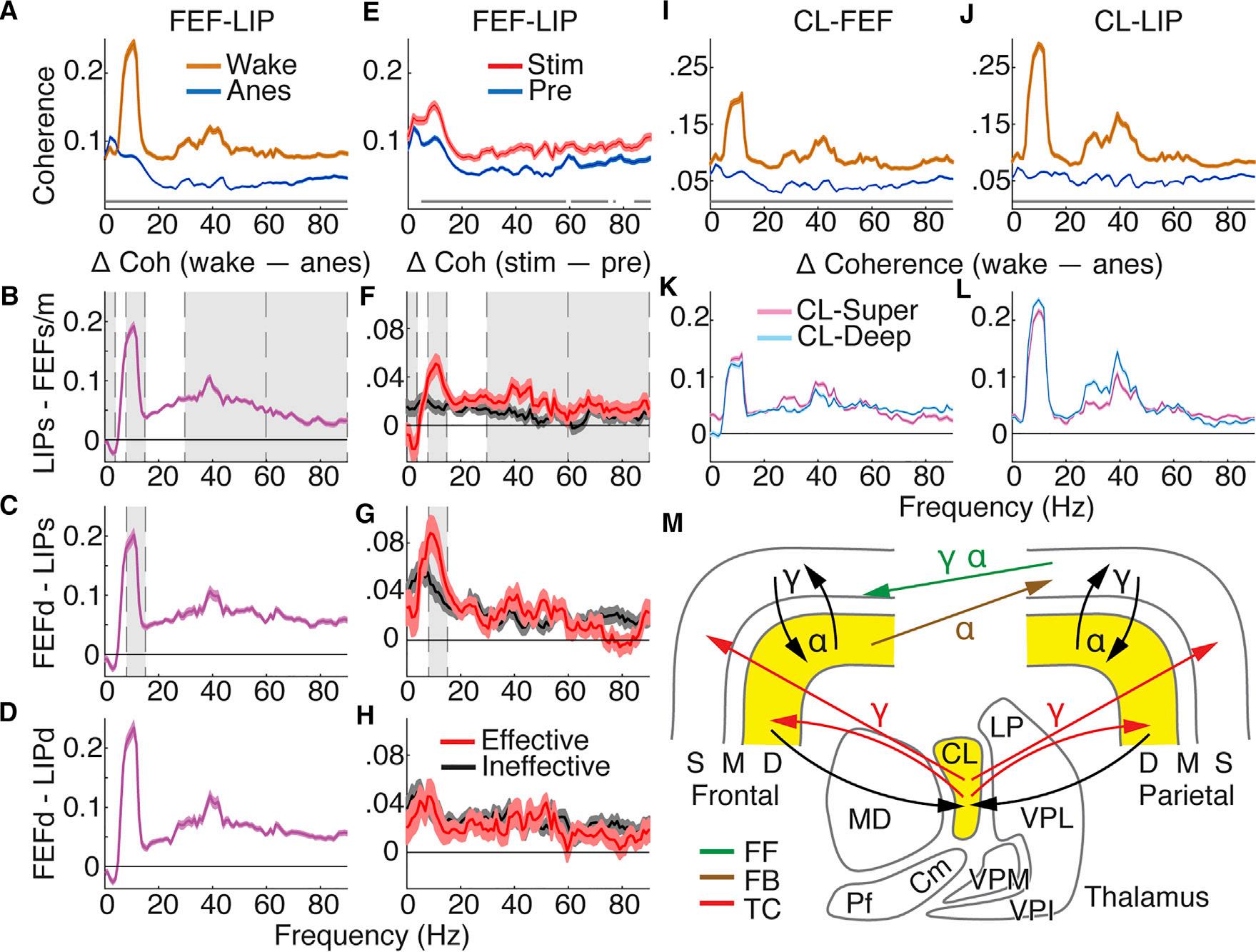

Wenextfocusonanatomicallymotivatedinteractionsacross thefrontoparietalcortex.Wemeasuredcoherencebetween theoriginandterminationofputativefeedforward(superficial LIP-superficialandmiddleFEF)andtwofeedback(deepFEF-superficialLIPordeepFEF-deepLIP)pathways(Markovetal., 2014;Mejiasetal.,2016).Wealsoexaminedstate-dependent effectsonthalamocorticalcoherence(CL-superficialorCLdeepcorticallayers)(Molinarietal.,1994;Townsetal.,1990). Communicationbetweencorticalareasshowedsignificant changesduringgeneralanesthesia(Figure4A).Corticocortical

4 Neuron 106,1–10,April8,2020

coherenceincreasedatdeltaanddecreasedatallhigherfrequenciesacrossputativefeedforwardandfeedbackpathways (|T| R 6.04,N R 4,030,p % 1.6 310 9; TableS3 forcomplete statistics).Wefoundqualitativelysimilarbutsmallereffects duringNREMsleep(FiguresS4C,S4F,andS4I)andforspikefieldcoherence(FiguresS4J–S4L; TableS3 forcompletestatistics).Coherencebetweenthalamusandeithersuperficialor deepcorticallayersdecreasedacrossallfrequencybandsduringanesthesia(Figures4I–4L; TableS4 forcompletestatistics). Thalamocorticalspike-fieldcoherenceshowedsimilareffects (FiguresS4M–S4R; TableS4 forcompletestatistics).These resultsshowthatanesthesiadecreasesbroadbandthalamocorticalandcorticocorticalcoherence.

Thalamicstimulationisolatedspecificinteractionsbetween corticalareasimportantforconsciousness(Figure4E).Effectivestimulationsresultedintargetedrestorationoffrontoparietalcoherenceinputativefeedforwardandfeedbackpathways (Figures4F–4H).Coherencebetweensuperficiallayersof LIPandsuperficialandmiddleFEFsubstantiallyreducedat delta(T= 4.05,n=2,799,p=8.6 3 10 4),andincreased atalpha(T=6.87,n=2,799,p=1.46 3 10 10),lowgamma (T=4.45,n=2,799,p=1.50 3 10 4),andhighgamma (60–90Hz;T=3.03,n=2,799,p=0.027),foreffectivemore thanineffectivestimulations,asshownbysignificantinteractions(Figure4F).Therewasalsoasignificantinteractionfor coherencebetweendeeplayersofFEFandsuperficialLIPat alpha(Figure4G;T=3.97,n=1,617,p=0.001),showing

Figure3.IntracolumnarInteractionsShowLayer-SpecificNCC

(AandB)PopulationFEF(A)andLIP(B)coherencewith95%confidenceintervalsforwakefulnessandanesthesia.Averageofallcontactpairsacrosslayers.The graylinesshowsignificantdifferencesbetweenspectra(Holm’scorrectedttests).

(C–H)Populationcoherencedifferencebetweenwakefulnessandanesthesia.Positivewhenwake>anesthesia.Theerrorbarsindicate95%confidenceintervals ofttestsateachfrequency.Thegrayshadingshowseffectsconsistentbetweenstate(wakeversusanesthesia)andthalamicstimulation(effectiveversus ineffectiveinK–P)results.Averageofallcontactpairsforandbetweensuperficial(C)FEFand(D)LIP;superficialanddeep(E)FEFand(F)LIP;anddeep(G)FEF and(H)LIP.

(IandJ)PopulationFEF(I)andLIP(J)coherencewith95%confidenceintervalsunderanesthesiabeforeandduringeffectivestimulation.Averageacrossall layers.

(K–P)Populationcoherencedifference(stim–pre)with95%confidenceintervalsforeffectiveandineffectivestimulations.Positivewhenstim>pre.Averageofall contactpairsforandbetweensuperficial(K)FEFand(L)LIP;superficialanddeep(M)FEFand(N)LIP;anddeep(O)FEFand(P)LIP.

substantialincreasesinalphacoherencespecifictoeffective stimulations.WhilecoherencebetweenFEFandLIPdeep corticallayersdidgenerallyincreasewithstimulation,nointeractionsweresignificant(Figure4H; TableS3 forcompletestatistics).Overall,more-consciousstatesshowedincreased alphaandgammacoherenceinfeedforwardpathwaysas wellasalphacoherenceinthefeedbackpathwaysoriginating indeeplayersandterminatinginsuperficiallayersofthe lower-orderarea.

DISCUSSION

Circuit-LevelMechanismforConsciousnessand Anesthesia

Ourresultssuggestthatspecificfeedforwardandfeedback corticocorticalpathaswellasintracolumnarandthalamocort-

icalcircuitdynamicscontributetotheNCC(Figure4M). Welinkconsciousnesstoincreasedspikingactivityin deepcorticallayersandCL,whichisconsistentwithcatand rodentstudiesofV1(LivingstoneandHubel,1981;Senzai etal.,2019)andCL(GlennandSteriade,1982)comparing wakefulnessandNREMsleep.Thisspikingactivityislikely sustainedthroughreciprocaldeep-layercortex-CLconnections,becausereduceddeepcorticallayerandCLspiking coincidedwithreducedfunctionalconnectivitybetween CLandcortex,andCLstimulationincreaseddeepcortical layerspiking.

Thedeepcorticallayersareanatomicallypositionedto drivefeedbacktosuperficiallayersinlower-orderareas,and toinfluencefeedforwardpathwaysviainteractionswithsuperficiallayersinthesamecorticalcolumn.CL,withprojections bothtosuperficialanddeepcorticallayers,canmodulate

Figure4.ThalamocorticalandCorticocorticalInteractionsShowPathway-SpecificNCC

(A)Populationcoherencewith95%confidenceintervalsforallpairedcontactsbetweenFEFandLIPduringwakefulnessandanesthesia.Thegraylinesshow significantdifferencesbetweenspectra(Holm’scorrectedttests).

(B–D)Populationaveragecoherencedifference:wake–anesthesia.Theerrorbarsindicate95%confidenceintervalsofttestsateachfrequency.Thegray shadingshowseffectsconsistentbetweenstateandthalamicstimulation(inF–H)results.(B)SuperficialLIPandsuperficialandmiddleFEF;(C)deep FEFand superficialLIP;and(D)deepFEFanddeepLIP.

(E)PopulationcoherencebetweenFEFandLIPwith95%confidenceintervalsforallpairedcontactsunderanesthesia,beforeandduringeffectivestimulation.

(F–H)Populationaveragecoherencedifference,stim–pre,with95%confidenceintervalsforeffectiveandineffectivestimulations.(F)SuperficialLIPandsuperficialandmiddleFEF;(G)deepFEFandsuperficialLIP;and(H)deepFEFanddeepLIP.

(IandJ)Populationthalamocorticalcoherencewith95%confidenceintervalsforwakeandanesthesiaacrossallpairedCL-FEF(I)andCL-LIP(J)contacts. (KandL)Populationaveragethalamocorticalcoherencedifference,wake–anesthesia,with95%confidenceintervalsofttests.CL-superficialandCL-deep layersfor(K)FEFand(L)LIP.

(M)SchematicshowingpathwaysandpredominantfrequenciescontributingtoNCC.Yellowshadingwherespikingchangeswithconsciousnesslevel.FF, feedforward;FB,feedback;TC,thalamocortical.

intracolumnarandcross-areainteractions(PurpuraandSchiff, 1997).Theseinteractionsoperatedatalphaandgammafrequenciesduringconsciousness,whereasgeneralanesthesia andsleepreducedactivityindeepcorticallayersandCL, thusreducingalphaandgammafrequencycommunication withinandbetweencorticalareas.ReactivationofthisCLdeepcorticallayerloopwithgamma-frequencystimulation reinstatedwake-likecorticaldynamicsandincreasedtheconsciousnesslevel,overcomingtwoseparateanestheticswith differentmoleculartargets.Overall,ourstudyprovides empiricalevidenceforacircuit-levelmechanismofconsciousnesswithspecialemphasisonthereciprocalinteraction betweenCLanddeepcorticallayers,whichmayserveasa

commontargetofanestheticdrugs,particularlythosewith actionsontheGABA-Areceptor.

SpecificityofEffectiveThalamicStimulationPointsto MinimalandSufficientMechanismsforConsciousness OurresultssuggestthatCLhasaspecialroletoplayinconsciousness,asstimulationsweremosteffectivewhen centeredonCLasopposedtoneighboringthalamicareas, suchasthemediodorsal(MD)andcentromedian(CM)nuclei. Thus,theuniquepropertiesofCLhaveimportantimplications forconsciousness.CLprojectstosuperficialanddeeplayers ofthefrontalandtheparietalcortex(KaufmanandRosenquist,1985;PurpuraandSchiff,1997;Townsetal.,1990).

ThisprojectionpatterndifferssubstantiallyfromtheMD,which largelyprojectstotheprefrontalcortexandhasdifferent laminardistribution(EricksonandLewis,2004;Giguereand Goldman-Rakic,1988;RayandPrice,1993).Whilecholinergic stimulationoffrontalcortexhasprovensufficientforbehavioralarousalinrodents( Paletal.,2018),prefrontalstimulation viatheMDprovedlesseffectiveinourmacaques.Thissuggeststhatprefrontalactivationalone,viatheMD,isinsufficientforconsciousness.CLalsohasaprominentprojection tothestriatum,whichcouldcontributetoconsciousness. However,theCM,withastrongerprojectiontothestriatum butlimitedcorticalprojections(Smithetal.,2004),wasless effectivethanCLstimulationatinducingconsciousness.This suggeststhatactivationofthedirectthalamo-striatalpathis insufficientforconsciousness.Ourresultsfurthersupport coordinatedactivityacrosstheCLandthefrontoparietalcortexasNCC.

ValidatingNCCwithMultipleConsciousand UnconsciousStates

Changesinconsciousnesscoincidewithstatechangesacross sleepandwakecycles,traumaticbraininjury,orexposuretoa widerangeofanestheticagentswithdifferentmoleculartargets.Assuch,itcanbedifficulttodistinguishNCCfromneural effectsspecifictooneofthesestates,suchaseffectsofattention,trauma,oraparticularpharmacologicalagent.Inthis study,weshowNCCinathalamocorticalsystemthatare(1) similarlyperturbedinnatural(sleep)andtwoinducedstatesof unconsciousnesswithdifferentpharmacologicalagents(isofluraneorpropofol),and(2)validatedintwostatesofconsciousness,normalwakefulness,andstimulation-induced arousalduringcontinuousanestheticadministration(Figures3 and 4,grayshading).Thisshowsthatourresultsareneither drugspecificnorpurelyreflectinganunnaturalstateofconsciousness.Rather,ourresultsshowconsistentNCCandpoint toacommoncircuit-leveltargetofgeneralanesthetics.

BeyondDelta:Path-SpecificIndicatorsofLevelof Consciousness

Sincetheearlystudiesofconsciousness,electroencephalogram(EEG)deltaactivityhasbeenconsideredcriticalforsleep stagingandmonitoringdepthofanesthesia.Ourresults showthatdeltaactivity,whileprevalentinunconsciousstates (isoflurane,propofol,andsleep),differsbetweenthefrontal andtheparietalcortex,aswellasacrosscorticallayers,and isnotitselfapredictorofbehavioralarousal(FiguresS3A–S3H).Furthermore,wefoundthatwhiledeltacoherence wasanticorrelatedwithconsciousnessinfeedforwardpathways,possiblydemonstratingamechanismfordisconnection, therewasnosuchrelationforfeedbackpathways(Figures4F–4H).Ifdeltaoscillationsdofacilitatecorticocorticaldisconnection,ourfindingssuggestthattheydosoinapathwayspecificmanner,inwhichfeedforwardprocessesarereadily disruptedbytheincreasedprevalenceofdeltaactivityrelative tofeedback.Thus,deltaoscillationsmayplayalargerrole indisconnectingthebrainfromtheexternalsensoryenvironmentthaninpreventinginternalandtop-downgenerated experiences.

Long-RangeFrontoparietalInteractionContributesto Consciousness,NotJustReport

Frontalcorticalactivity,instudiesofconsciousnessrequiring behavioralreports,mayreflectthereportratherthanthelevel ofconsciousness(Tsuchiyaetal.,2015 ).Ourstudydidnot requirereport(althoughitcannotberuledoutcompletelythat observedactivityreflectsanunderlyingprocessrelatedtoreporting).Furthermore,toruleoutsensorimotordifferences betweendifferentstatesofconsciousness,weperformedrecordingsinaquiet,darkroomandonlyanalyzeddatafrom epochswhenthemonkey’seyeswerestable,therebycontrollingforsensorystimulationandeyemovements.Underthese conditions,wefoundfrontoparietalinteractionfeaturedduring wakefulnessandstimulation-inducedarousal,appearing rapidlyaftertheonsetofthalamicstimulationandgenerally dissipatingjustasquicklyafterstimulationendedinanesthetizedmonkeys.Thissuggeststhatfrontoparietalcommunicationmaynotsimplyberelatedtoreport,butrathercontributes totheconsciousexperience.Becausefeedbackprojections todistantcorticalareaspreferentiallyterminateinsuperficial layers(whereasfeedbacktoadjacentareaspreferentially terminateindeeplayers)(Markovetal.,2014),ourfindingthat feedbacktosuperficiallayerscorrelatedwiththelevelofconsciousnessmaysuggestthatlong-rangefeedbackprojections arevitalforconsciousness.

ImplicationsforClinicalInterventionsinDisordersof Consciousness

Interventionsusingclinicaldeepbrainstimulation(DBS)electrodesinhumans(Schiffetal.,2007)andmonkeys(Baker etal.,2016)andbipolarstimulatingelectrodesinrodents (MairandHembrook,2008;Shirvalkaretal.,2006)haveshown arousalmodulationwithstimulationfrequenciesbetween100 and200Hz.Incomparison,usingalinearmulti-electrode arraywithasmallelectrodecontactsize,wefoundthatCLstimulationmosteffectivelyinducedarousalat50Hz(cf.with2,10, and200Hz).CLisanelongatednucleusalongthedorsalventralaxis, 3–4mminextentinmacaques.Byusinglinear multi-electrodearrays(simultaneouslystimulating16contacts, with200- m minter-contactspacing),wewereabletostimulate acrossthedorsal-ventralextentofCLatsmall,regularlyspaced intervalsinarelativelypreciseway.Thisconfigurationledtothe greatestbehavioraleffects(Figures1Fand S1D–S1F),demonstratingclearspatialspecificity.Whileourstudydidnottestthe fullrangeofclinicallyrelevantstimulationfrequencies,itisinterestingtonotethat50-Hzstimulationinourstudy,andthemore spatiallyrefined40-and100-Hzoptogeneticstimulationina ratsleepstudy(Liuetal.,2015),modulatedarousal.These frequenciesmatchtheactivitypatternsofthesubsetofCL neuronswithahighfiringrateduringwakefulness,reportedin FiguresS2EandS2Fandpreviouswork(GlennandSteriade, 1982;Steriadeetal.,1993).Mimickingthewakefulfiring rateoftheseneuronsduringanestheticadministrationmay partiallyexplaintheincreasedefficacyofgammastimulation inourdata.Inlightoftheseresults,itmaybepossibletooptimizeclinicalDBStobetterreflectthedesiredneuraldynamics ofaffectedthalamocorticalcircuitstohelpalleviatedisorders ofconsciousness.

STAR+METHODS

Detailedmethodsareprovidedintheonlineversionofthispaper andincludethefollowing:

d KEYRESOURCESTABLE

d LEADCONTACTANDMATERIALSAVAILABILITY

d EXPERIMENTALMODELANDSUBJECTDETAILS

d METHODDETAILS

B Neuroimaging

B Surgery

B Behavioraltasksandsensorystimuli

B Arousalscoring

B Electrophysiologicalrecordingandstimulation

B Electrodearraylocalization

B Anesthesiaexperiments

B Awakeexperiments

B Sleep

B Neuraldatapreprocessing

B Spikerate

B Spiketiming

B Currentsourcedensity(CSD)

B Power

B Coherence

d QUANTIFICATIONANDSTATISTICALANALYSIS

B Generalapproach

B Stimulationeffects

B Spikerateeffects

B Burstingeffects

B Powerandcoherenceeffects

d DATAANDCODEAVAILABILITY

SUPPLEMENTALINFORMATION

SupplementalInformationcanbefoundonlineat https://doi.org/10.1016/j. neuron.2020.01.005

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

WethankM.I.Banks,C.W.Berridge,R.A.Pearce,R.D.Sanders,B.M.Krause, andC.Murphyforusefulcommentsonthemanuscript.ThisworkwassupportedbyNIHgrantsR01MH110311andP51OD011106,BSFgrant201732, andaWNPRCpilotgrant.

AUTHORCONTRIBUTIONS

M.J.R.,J.M.P.,N.A.K.,S.M.,A.R.,andY.B.S.performedtheresearch;M.J.R., S.A.,G.L.D.,M.A.,andY.B.S.analyzedthedata;M.J.R.,A.R.,andY.B.S. wrotethepaper;M.J.R.,J.M.P.,N.A.K.,S.M.,S.A.,G.L.D.,M.A.,A.R.,and Y.B.S.editedthepaper.

DECLARATIONOFINTERESTS

A.R.isaconsultantforandreceivesfundingfromMedtronic.Theotherauthors declarenocompetinginterests.

Received:November19,2019

Revised:December26,2019

Accepted:January7,2020

Published:February12,2020

REFERENCES

Baker,R.,Gent,T.C.,Yang,Q.,Parker,S.,Vyssotski,A.L.,Wisden,W., Brickley,S.G.,andFranks,N.P.(2014).Alteredactivityinthecentralmedial thalamusprecedeschangesintheneocortexduringtransitionsintobothsleep andpropofolanesthesia.J.Neurosci. 34,13326–13335.

Baker,J.L.,Ryou,J.W.,Wei,X.F.,Butson,C.R.,Schiff,N.D.,andPurpura,K.P. (2016).Robustmodulationofarousalregulation,performance,andfrontostriatalactivitythroughcentralthalamicdeepbrainstimulationinhealthy nonhumanprimates.J.Neurophysiol. 116,2383–2404.

Bokil,H.,Purpura,K.,Schoffelen,J.M.,Thomson,D.,andMitra,P.(2007). Comparingspectraandcoherencesforgroupsofunequalsize.J.Neurosci. Methods 159,337–345.

Bokil,H.,Andrews,P.,Kulkarni,J.E.,Mehta,S.,andMitra,P.P.(2010). Chronux:aplatformforanalyzingneuralsignals.J.Neurosci.Methods 192, 146–151.

Bollimunta,A.,Chen,Y.,Schroeder,C.E.,andDing,M.(2008).Neuronal mechanismsofcorticalalphaoscillationsinawake-behavingmacaques. J.Neurosci. 28,9976–9988.

Boly,M.,Garrido,M.I.,Gosseries,O.,Bruno,M.A.,Boveroux,P.,Schnakers, C.,Massimini,M.,Litvak,V.,Laureys,S.,andFriston,K.(2011).Preserved feedforwardbutimpairedtop-downprocessesinthevegetativestate. Science 332,858–862.

Bruce,C.J.,Goldberg,M.E.,Bushnell,M.C.,andStanton,G.B.(1985).Primate frontaleyefields.II.Physiologicalandanatomicalcorrelatesofelectrically evokedeyemovements.J.Neurophysiol. 54,714–734.

Caruso,V.C.,Pages,D.S.,Sommer,M.A.,andGroh,J.M.(2016).Similarprevalenceandmagnitudeofauditory-evokedandvisuallyevokedactivityinthe frontaleyefields:implicationsformultisensorymotorcontrol. J.Neurophysiol. 115,3162–3173.

Chen,X.,Zirnsak,M.,andMoore,T.(2018).DissonantRepresentationsof VisualSpaceinPrefrontalCortexduringEyeMovements.CellRep. 22, 2039–2052.

Cohen,Y.E.,Russ,B.E.,andGifford,G.W.,3rd(2005).Auditoryprocessingin theposteriorparietalcortex.Behav.Cogn.Neurosci.Rev. 4,218–231. Contreras,D.,Destexhe,A.,Sejnowski,T.J.,andSteriade,M.(1997). Spatiotemporalpatternsofspindleoscillationsincortexandthalamus. J.Neurosci. 17,1179–1196.

Dehaene,S.,andChangeux,J.P.(2011).Experimentalandtheoreticalapproachestoconsciousprocessing.Neuron 70,200–227.

Erez,Y.,Tischler,H.,Moran,A.,andBar-Gad,I.(2010).Generalizedframeworkforstimulusartifactremoval.J.Neurosci.Methods 191,45–59. Erickson,S.L.,andLewis,D.A.(2004).Corticalconnectionsofthelateralmediodorsalthalamusincynomolgusmonkeys.J.Comp.Neurol. 473,107–127. Friston,K.(2010).Thefree-energyprinciple:aunifiedbraintheory?Nat.Rev. Neurosci. 11,127–138.

Funk,C.M.,Honjoh,S.,Rodriguez,A.V.,Cirelli,C.,andTononi,G.(2016).Local SlowWavesinSuperficialLayersofPrimaryCorticalAreasduringREMSleep. Curr.Biol. 26,396–403.

Gifford,G.W.,3rd,andCohen,Y.E.(2005).Spatialandnon-spatialauditory processinginthelateralintraparietalarea.Exp.BrainRes. 162,509–512. Giguere,M.,andGoldman-Rakic,P.S.(1988).Mediodorsalnucleus:areal, laminar,andtangentialdistributionofafferentsandefferentsinthefrontal lobeofrhesusmonkeys.J.Comp.Neurol. 277,195–213.

Glenn,L.L.,andSteriade,M.(1982).Dischargerateandexcitabilityofcortically projectingintralaminarthalamicneuronsduringwakingandsleepstates. J.Neurosci. 2,1387–1404.

Grunewald,A.,Linden,J.F.,andAndersen,R.A.(1999).Responsestoauditory stimuliinmacaquelateralintraparietalarea.I.Effectsoftraining. J.Neurophysiol. 82,330–342.

Haegens,S.,Barczak,A.,Musacchia,G.,Lipton,M.L.,Mehta,A.D.,Lakatos, P.,andSchroeder,C.E.(2015).LaminarProfileandPhysiologyofthe a Rhythm

Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Redinbaughetal.,ThalamusModulatesConsciousnessviaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex,Neuron(2020),https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.005

inPrimaryVisual,Auditory,andSomatosensoryRegionsofNeocortex. J.Neurosci. 35,14341–14352.

Jenkinson,M.,Beckmann,C.F.,Behrens,T.E.,Woolrich,M.W.,andSmith, S.M.(2012).Fsl.Neuroimage 62,782–790.

Jones,E.G.(2009).Synchronyintheinterconnectedcircuitryofthethalamus andcerebralcortex.Ann.NYAcad.Sci. 1157,10–23.

Katzner,S.,Nauhaus,I.,Benucci,A.,Bonin,V.,Ringach,D.L.,andCarandini, M.(2009).Localoriginoffieldpotentialsinvisualcortex.Neuron 61,35–41. Kaufman,E.F.,andRosenquist,A.C.(1985).Efferentprojectionsofthe thalamicintralaminarnucleiinthecat.BrainRes. 335,257–279. Lacey,C.J.,Bolam,J.P.,andMagill,P.J.(2007).Novelanddistinctoperational principlesofintralaminarthalamicneuronsandtheirstriatalprojections. J.Neurosci. 27,4374–4384.

Lamme,V.A.(2006).Towardsatrueneuralstanceonconsciousness.Trends Cogn.Sci. 10,494–501.

Lee,U.,Kim,S.,Noh,G.J.,Choi,B.M.,Hwang,E.,andMashour,G.A.(2009). Thedirectionalityandfunctionalorganizationoffrontoparietalconnectivity duringconsciousnessandanesthesiainhumans.Conscious.Cogn. 18, 1069–1078.

Lee,U.,Ku,S.,Noh,G.,Baek,S.,Choi,B.,andMashour,G.A.(2013). Disruptionoffrontal-parietalcommunicationbyketamine,propofol,andsevoflurane.Anesthesiology 118,1264–1275.

Linden,J.F.,Grunewald,A.,andAndersen,R.A.(1999).Responsestoauditory stimuliinmacaquelateralintraparietalarea.II.Behavioralmodulation. J.Neurophysiol. 82,343–358.

Liu,J.,Lee,H.J.,Weitz,A.J.,Fang,Z.,Lin,P.,Choy,M.,Fisher,R.,Pinskiy,V., Tolpygo,A.,Mitra,P.,etal.(2015).Frequency-selectivecontrolofcorticaland subcorticalnetworksbycentralthalamus.eLife 4,e09215.

Livingstone,M.S.,andHubel,D.H.(1981).Effectsofsleepandarousalonthe processingofvisualinformationinthecat.Nature 291,554–561. Llinas,R.,Ribary,U.,Contreras,D.,andPedroarena,C.(1998).Theneuronal basisforconsciousness.Philos.Trans.R.Soc.Lond.BBiol.Sci. 353, 1841–1849.

Maimon,G.,andAssad,J.A.(2009).BeyondPoisson:increasedspike-time regularityacrossprimateparietalcortex.Neuron 62,426–440. Mair,R.G.,andHembrook,J.R.(2008).Memoryenhancementwitheventrelatedstimulationoftherostralintralaminarthalamicnuclei.J.Neurosci. 28, 14293–14300.

Maksimow,A.,Silfverhuth,M.,La ˚ ngsjo,J.,Kaskinoro,K.,Georgiadis,S., Jaaskelainen,S.,andScheinin,H.(2014).Directionalconnectivitybetween frontalandposteriorbrainregionsisalteredwithincreasingconcentrations ofpropofol.PLoSOne 9,e113616.

Markov,N.T.,Vezoli,J.,Chameau,P.,Falchier,A.,Quilodran,R.,Huissoud,C., Lamy,C.,Misery,P.,Giroud,P.,Ullman,S.,etal.(2014).Anatomyofhierarchy: feedforwardandfeedbackpathwaysinmacaquevisualcortex.J.Comp. Neurol. 522,225–259.

Mejias,J.F.,Murray,J.D.,Kennedy,H.,andWang,X.J.(2016).Feedforward andfeedbackfrequency-dependentinteractionsinalarge-scalelaminar networkoftheprimatecortex.Sci.Adv. 2,e1601335. Mitra,P.,andBokil,H.(2007).ObservedBrainDynamics(Oxford UniversityPress).

Molinari,M.,Leggio,M.G.,Dell’Anna,M.E.,Giannetti,S.,andMacchi,G. (1994).Chemicalcompartmentationandrelationshipsbetweencalcium-bindingproteinimmunoreactivityandlayer-specificcorticalcaudate-projecting cellsintheanteriorintralaminarnucleiofthecat.Eur.J.Neurosci. 6,299–312. Oizumi,M.,Albantakis,L.,andTononi,G.(2014).Fromthephenomenologyto themechanismsofconsciousness:IntegratedInformationTheory3.0.PLoS Comput.Biol. 10,e1003588.

Pal,D.,Dean,J.G.,Liu,T.,Li,D.,Watson,C.J.,Hudetz,A.G.,andMashour, G.A.(2018).DifferentialRoleofPrefrontalandParietalCorticesinControlling LevelofConsciousness.Curr.Biol. 28,2145–2152.e5.

Pettersen,K.H.,Devor,A.,Ulbert,I.,Dale,A.M.,andEinevoll,G.T.(2006). Current-sourcedensityestimationbasedoninversionofelectrostaticforward solution:effectsoffiniteextentofneuronalactivityandconductivitydiscontinuities.J.Neurosci.Methods 154,116–133.

Pigarev,I.N.,Saalmann,Y.B.,andVidyasagar,T.R.(2009).Aminimallyinvasiveandreversiblesystemforchronicrecordingsfrommultiplebrainsitesin macaquemonkeys.J.Neurosci.Methods 181,151–158.

Purpura,K.,andSchiff,N.D.(1997).TheThalamicIntralaminarNuclei:ARolein VisualAwareness.Neuroscientist 3,8.

Ray,J.P.,andPrice,J.L.(1993).Theorganizationofprojectionsfromthemediodorsalnucleusofthethalamustoorbitalandmedialprefrontalcortexinmacaquemonkeys.J.Comp.Neurol. 337,1–31.

Raz,A.,Grady,S.M.,Krause,B.M.,Uhlrich,D.J.,Manning,K.A.,andBanks, M.I.(2014).Preferentialeffectofisofluraneontop-downvs.bottom-uppathwaysinsensorycortex.Front.Syst.Neurosci. 8,191.

Romanski,L.M.,Tian,B.,Fritz,J.,Mishkin,M.,Goldman-Rakic,P.S.,and Rauschecker,J.P.(1999).Dualstreamsofauditoryafferentstargetmultiple domainsintheprimateprefrontalcortex.Nat.Neurosci. 2,1131–1136.

Saalmann,Y.B.,Pigarev,I.N.,andVidyasagar,T.R.(2007).Neuralmechanismsofvisualattention:howtop-downfeedbackhighlightsrelevantlocations.Science 316,1612–1615.

Saalmann,Y.B.,Pinsk,M.A.,Wang,L.,Li,X.,andKastner,S.(2012).Thepulvinarregulatesinformationtransmissionbetweencorticalareasbasedon attentiondemands.Science 337,753–756.

Saleem,K.S.,andLogothetis,N.K.(2007).ACombinedMRIandHistology AtlasoftheRhesusMonkeyBraininStereotaxicCoordinates (AcademicPress).

Sanders,R.D.,Banks,M.I.,Darracq,M.,Moran,R.,Sleigh,J.,Gosseries,O., Bonhomme,V.,Brichant,J.F.,Rosanova,M.,Raz,A.,etal.(2018).Propofolinducedunresponsivenessisassociatedwithimpairedfeedforwardconnectivityincorticalhierarchy.Br.J.Anaesth. 121,1084–1096.

Schall,J.D.,Morel,A.,King,D.J.,andBullier,J.(1995).Topographyofvisual cortexconnectionswithfrontaleyefieldinmacaque:convergenceandsegregationofprocessingstreams.J.Neurosci. 15,4464–4487.

Schiff,N.D.(2008).Centralthalamiccontributionstoarousalregulationand neurologicaldisordersofconsciousness.Ann.NYAcad.Sci. 1129,105–118.

Schiff,N.D.,Giacino,J.T.,Kalmar,K.,Victor,J.D.,Baker,K.,Gerber,M.,Fritz, B.,Eisenberg,B.,Biondi,T.,O’Connor,J.,etal.(2007).Behaviouralimprovementswiththalamicstimulationafterseveretraumaticbraininjury.Nature 448, 600–603.

Schmitt,L.I.,Wimmer,R.D.,Nakajima,M.,Happ,M.,Mofakham,S.,and Halassa,M.M.(2017).Thalamicamplificationofcorticalconnectivitysustains attentionalcontrol.Nature 545,219–223.

Schroeder,C.E.,Mehta,A.D.,andGivre,S.J.(1998).Aspatiotemporalprofile ofvisualsystemactivationrevealedbycurrentsourcedensityanalysisinthe awakemacaque.Cereb.Cortex 8,575–592.

Sellers,K.K.,Bennett,D.V.,Hutt,A.,andFrohlich,F.(2013).Anesthesiadifferentiallymodulatesspontaneousnetworkdynamicsbycorticalareaandlayer. J.Neurophysiol. 110,2739–2751.

Senzai,Y.,Fernandez-Ruiz,A.,andBuzsaki,G.(2019).Layer-Specific PhysiologicalFeaturesandInterlaminarInteractionsinthePrimaryVisual CortexoftheMouse.Neuron 101,500–513.e5.

Shirvalkar,P.,Seth,M.,Schiff,N.D.,andHerrera,D.G.(2006).Cognitive enhancementwithcentralthalamicelectricalstimulation.Proc.Natl.Acad. Sci.USA 103,17007–17012.

Smith,Y.,Raju,D.V.,Pare,J.F.,andSidibe,M.(2004).Thethalamostriatalsystem:ahighlyspecificnetworkofthebasalgangliacircuitry.TrendsNeurosci. 27,520–527.

Steriade,M.,Curro Dossi,R.,andContreras,D.(1993).Electrophysiological propertiesofintralaminarthalamocorticalcellsdischargingrhythmic(approximately40HZ)spike-burstsatapproximately1000HZduringwakingandrapid eyemovementsleep.Neuroscience 56,1–9.

Neuron 106,1–10,April8,2020 9

Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Redinbaughetal.,ThalamusModulatesConsciousnessviaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex,Neuron(2020),https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.005

Theyel,B.B.,Llano,D.A.,andSherman,S.M.(2010).Thecorticothalamocorticalcircuitdriveshigher-ordercortexinthemouse.Nat.Neurosci. 13,84–88.

Towns,L.C.,Tigges,J.,andTigges,M.(1990).Terminationofthalamicintralaminarnucleiafferentsinvisualcortexofsquirrelmonkey.Vis.Neurosci. 5, 151–154.

Trongnetrpunya,A.,Nandi,B.,Kang,D.,Kocsis,B.,Schroeder,C.E.,and Ding,M.(2016).AssessingGrangerCausalityinElectrophysiologicalData: RemovingtheAdverseEffectsofCommonSignalsviaBipolarDerivations. Front.Syst.Neurosci. 9,189.

Tsuchiya,N.,Wilke,M.,Frassle,S.,andLamme,V.A.F.(2015).No-Report Paradigms:ExtractingtheTrueNeuralCorrelatesofConsciousness.Trends Cogn.Sci. 19,757–770.

Uhrig,L.,Sitt,J.D.,Jacob,A.,Tasserie,J.,Barttfeld,P.,Dupont,M.,Dehaene, S.,andJarraya,B.(2018).Resting-stateDynamicsasaCorticalSignatureof AnesthesiainMonkeys.Anesthesiology 129,942–958.

vanVugt,B.,Dagnino,B.,Vartak,D.,Safaai,H.,Panzeri,S.,Dehaene,S.,and Roelfsema,P.R.(2018).Thethresholdforconsciousreport:signallossand responsebiasinvisualandfrontalcortex.Science 360,537–542.

Wardak,C.,Olivier,E.,andDuhamel,J.R.(2002).Saccadictargetselection deficitsafterlateralintraparietalareainactivationinmonkeys.J.Neurosci. 22,9877–9884.

Wardak,C.,Ibos,G.,Duhamel,J.R.,andOlivier,E.(2006).Contributionofthe monkeyfrontaleyefieldtocovertvisualattention.J.Neurosci. 26,4228–4235. Womelsdorf,T.,Ardid,S.,Everling,S.,andValiante,T.A.(2014).Burstfiring synchronizesprefrontalandanteriorcingulatecortexduringattentionalcontrol.Curr.Biol. 24,2613–2621.

Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Redinbaughetal.,ThalamusModulatesConsciousnessviaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex,Neuron(2020),https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.005

STAR+METHODS

KEYRESOURCESTABLE

REAGENTorRESOURCESOURCEIDENTIFIER Chemicals,Peptides,andRecombinantProteins

Isoflurane,USPPiramalEnterprisesLimitedNDC66794-013-25 PropoFlo28(Propofol)ZoetisInc.NDC54771-4944-1 KETAVED(KETAMINEHCL100MG) VedcoInc.NDC50989-996-06

ExperimentalModels:Organisms/Strains Monkeys(Macacamulatta)WisconsinNationalPrimate ResearchCenter(WNPRC)

SoftwareandAlgorithms

OmniPlexServerv1.14.1Plexon

https://www.primate.wisc.edu/

https://plexon.com/products/omniplex-software/ PlexContronv1.14.1Plexon https://plexon.com/products/omniplex-software/ PlexonStim-2v2.3.0.0Plexon https://plexon.com/products/plexstim-electricalstimulator-2-system/

Presentationv19.0NeurobehavioralSystems https://www.neurobs.com/ LogitechWebcamSoftwarev2.51Logitech https://support.logi.com/hc/en-us/articles/ 360024691274–Downloads-Webcam-C260 Fslv1.6OxfordUniversityInnovation https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsldownloads_registration Fsleyesv0.22.6OxfordUniversityInnovation https://fsl.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsldownloads_registration XQuartzv2.7.11X.OrgFoundation https://www.xquartz.org/ OfflineSorterv4Plexon https://plexon.com/products/offline-sorter/ MATLABR2015bMathWorks https://www.mathworks.com/products.html? s_tid=gn_ps

Chronuxv2.11chronux http://chronux.org/ SARGEtoolboxv1.5.4IBGLab https://www.ibglab.org/sarge CSDplotterv0.1.1KlasPettersen (klas.pettersen@umb.no.) https://github.com/espenhgn/CSDplotter Rv3.2.2RFoundationfor StatisticalComputing https://www.r-project.org/ RStudiov1.1.463RStudio https://rstudio.com/ MovaviVideoConverterv7.3.0Movavi https://www.movavi.com/videoconvertermac/? device=c&gclid=Cj0KCQiAtrnuBRDXARIsABiN7BytoiOxcGD8lyR3Fvs1MGc3zWwA0UisQaA1 DdujFHHS_q1fbZk6WwaAlnlEALw_wcB Elmediavideoplayerv7.6ElmediaPlayer https://www.elmedia-video-player.com/ Other MacaqueStimulatedArousalIndexThispaper

LEADCONTACTANDMATERIALSAVAILABILITY

STARMethods,Email(mredinbaugh@wisc.edu)

Thisstudydidnotgeneratenewuniquereagents.Furtherinformationandrequestsregardingresources,equipment,andexperimentalmethodsshouldbedirectedto,andwillbefulfilledby,theLeadContact,YuriB.Saalmann(saalmann@wisc.edu).

EXPERIMENTALMODELANDSUBJECTDETAILS

Weacquireddatafromtwomalemonkeys(Macacamulatta, 4.3-5.5yearsold,7.63-10.30kgbodyweight).AnimaldailyneedsmaintainedbyexperimentersandhusbandrystaffattheWisconsinNationalPrimateResearchCenter(WNPRC),whereanimals werehoused.AnimalhealthwasmonitoredbyveterinariansattheWNPRC.TheUniversityofWisconsin-MadisonInstitutional AnimalCareandUseCommitteeapprovedallprocedures,whichconformedtotheNationalInstitutesofHealthGuideforthe CareandUseofLaboratoryAnimals.

,1–10.e1–e12,April8,2020

METHODDETAILS

Neuroimaging

WeperformedstructuralimagingonanesthetizedmonkeysusingtheGEMR7503Tscanner(GEHealthcare,WaukeshaWI).At thestartofeachscansession,wepre-medicatedthemonkeywithketamine(upto20mg/kgbodyweight)andatropinesulfate (0.03-0.06mg/kg),priortointubation.Wethenadministeredisoflurane(1%–3%on 1L/minO2 flow)tothemonkey,withasemiopenbreathingcircuitandspontaneousrespiration,tomaintaingeneralanesthesiaforthedurationofthesession.Wemonitored themonkey’svitalsigns(expiredcarbondioxide,respirationrate,oxygensaturation,pulserate,temperature)usinganMR-compatiblepulseoximeterandrectalthermometer.

Weacquiredahigh-resolutionstructuralbrainimagepriortotheimplantsurgery,todelineatethalamocorticalregionsofinterest (ROIs),and,aftercraniotomy,additionalscansofelectrodes insitu toconfirmelectrodepositioning.Forthesethreedimensional T1-weightedstructuralimages,weusedaninversion-recoverypreparedgradientechosequencewiththefollowingparameters: FOV=128mm2;matrix=256 3 256;no.ofslices=166;0.5mmisotropic;TR=9.68ms;TE=4.192ms;flipangle=12 ;inversion time(TI)=450ms).Togeneratethehigh-qualitystructuralimage,wecollected6-10T1-weightedstructuralimagesandcalculated theaverageimageforeachmonkeyusingtheFMRIBSoftwareLibrary(FSL)(Jenkinsonetal.,2012).Tolocalizeelectrodes,weaveragedtwostructuralimagesofelectrodes insitu

Surgery

Weinducedanesthesiawithketamine(upto20mg/kgbodyweight,i.m.)andmaintainedgeneralanesthesiaduringasepticsurgical procedureswithisoflurane(1%–2%).Weused12ceramicskullscrewsanddentalacrylictoaffixheadimplantsonmonkeys.We drilled2.5mmcraniotomiesinthefrontalandparietalboneswithinacustomizedplasticrecordingchamber,providingaccessto ourthreethalamocorticalROIsintherighthemisphere:frontaleyefield(FEF),lateralintraparietalarea(LIP),andcentrallateral thalamicnucleus(CL).Wederivedcraniotomycoordinatesfromthehigh-qualityT1-weightedstructuralimagesacquiredpriorto thesurgery.Wefittedeachcraniotomywithaconicalplasticguidetubefilledwithbonewax(guidetubeprefabricatedusing modelofskullbasedonT1-weightedstructuralimages)(Pigarevetal.,2009;Saalmannetal.,2007,2012)throughwhichlinear electrodearraystraversed.Wealsoinsertedtwotitaniumskullscrewswithintherecordingchamber,onefromwhichtorecord theEEGandonetoserveasareference.Theheadimplantincludedaheadpostand,ontheimplantleftandrightsides,fourhollow slots(twooneachside)intowhichrodsfitted,allowingheadimmobilizationduringelectrophysiologicalrecordings.

Behavioraltasksandsensorystimuli

Tocompareelectrophysiologicaldatabetweendifferentstatesofconsciousness,weneededtoacquiredataundersimilarbehavioral andsensoryconditionsforawakeandanesthetizedmonkeys.Thus,weacquiredelectrophysiologicaldatafrombothawakeand anesthetizedmonkeysduringapassiveauditoryoddballparadigmaswellasduring‘‘restingstate’’(inwhichnosensorystimuli werepresented).Thepassiveauditoryoddballparadigmwasusefulbecauseitdoesnotrequireabehavioralresponse,doesnot requireopeneyes,andauditorystimulihavebeenshowntoelicitneuronalresponsesfromFEF(Carusoetal.,2016;Romanski etal.,1999;Schalletal.,1995)andLIP(Cohenetal.,2005;GiffordandCohen,2005;Grunewaldetal.,1999;Lindenetal.,1999), allowingsound-alignedcurrentsourcedensityanalyses.Additionally,ascontrolsintheawakemonkeys,weacquiredelectrophysiologydataduringafixationtask,andduringthepassiveauditoryoddballparadigmwhilethemonkeymaintainedfixation(oddball paradigmrunconcurrentlywithfixationtask;see‘‘AwakeExperiments’’section).Allelectrophysiologicalrecordingsoccurredina quiet,darkroom.

Inthepassiveauditoryoddballparadigm,thesequenceofauditorytones(200msduration,with800±100msjitterbetweeneach tone)comprised80%standardtones(0.9kHzfrequency)and20%deviant/oddballtones(1kHzfrequency).Atleastthefirstfour stimuliofasequence(3mindurationforanesthesia;6mindurationforwake)werestandardtones,andtwosequentialtonescould notbedeviantstimuli,otherwisethetoneorderwaspseudorandomwithintheconstraintoftheoverall80/20standard-to-deviant ratio.Wepresentedtonesusingtwospeakersplaced35cmfromeachearunderanesthesiaand80cmfromeachearduringwakefulness(soundlevelateachearwasabout75dBSPLforbothstates).

Inthefixationtask,themonkeyneededtofixateacentralfixationpoint(dimgraycircleofdiameter0.42degreesofvisualangle onblackbackground)onthemonitorscreenlocated57cmaway.Themonkeyreceivedasmallvolume(0.18-0.22mL)ofjuiceevery 2.2-3.5swhilemaintainingfixationwithina3 3 3degreeofvisualanglewindow,centeredonthefixationpoint.Whenthemonkey’s gazeleftthefixationwindow,hewouldtypicallyre-establishcentralfixationquickly,toagainreceivejuiceevery2.2-3.5s whilefixating.Toencouragelongfixations,wedoubledthejuicevolumeiffixationpersistedbeyond10s.Weonlyanalyzed electrophysiologicaldataduringstableeyeepochs(eyepositionremainedfixedforatleast1s).Thisappliedtoallwake-state data(resting,oddballparadigmandfixationtask).

Forawakeexperiments,wemonitoredmonkeys’eyepositionusingavideo-basedeyetracker(500Hzsamplingrate).For anesthesiaexperiments,wemonitoredeyesusingadigitalvideocamera(capturing30framespersecond)andusedMATLABto analyzeluminancecontrastinawindowtightlyboundingtheeyeimage.Thecontrastdifferentiatedclosedeyes(i.e.,relatively

homogeneoushighluminanceeyelidshade)andthalamicstimulation-inducedeyeopenings(i.e.,darkpupilandiriscontrasting againstsclera),asshownin Figure1A;andvisualinspectionoftheeyevideoverifiedthetimingofeyeopenings/closingsderived fromthecontrastanalysis.

Arousalscoring

Wedevelopedanarousalindexbasedonclinicalarousalscalestomeasurethebehavioraleffectsofelectricalstimulation.The arousalindexincorporatedfivemainindicatorsofarousal,witheachindicatorscored0,1or2,andthesumofthescoresofthe fiveindicatorsyieldingthearousalindex(range0-10).Thefiveindicatorsare:

1)limb/facemovements(0=nothing;1=smallmovementorincreasedEMGwithnoclearmovement;2=fullreachorwithdrawal)

2)oralsigns(0=nothing;1=smallmouth/jaw/tonguemovements;2=fulljawopenings/closures,withmultiplerepetitions)

3)bodymovements(0=nothing;1=smalltorsomovementorswallowing;2=largefulltorsomovement)

4)eyemovements/openings(0=nothing;1=eyelidflutters/smallblinksorincreasedeyemovements;2=fulleyeopeningwith occasionalblinks)

5)vitalsigns(0=nochange,i.e.,differenceof<10%respirationrate(RR),<5%heartrate(HR);1=differenceof>10%RR,>5% HR;2=atleast20%changeineitherRRorHR,oratleast10%changeinbothRRandHR;comparedtobaseline30spriorto stimulation).

AveterinarianattheWisconsinNationalPrimateResearchCenter,aclinicalanesthesiologist,andfiveotherprimateelectrophysiologistsobservedtheelectricalstimulationeffectsduringanesthesiaexperiments.Usingobservationsrecordedatthetimeof stimulationexperimentsaswellasofflinereviewofvideosandEMGdata(filtered30-450Hz,full-waverectified,thenfiltered 5-100Hztoextracttheenvelope),wescoredarousallevelpriorto,during,andafterallstimulationevents.Atypicalstimulationblock consistedofthreestimulationeventrepetitions(oneminuteeach)withinasevenminuterecordingperiodatagivensite,usingthe samestimulationfrequency,current,polarity,duration,anestheticanddose.Wedefinedstimulationeventepochsfromtheonset tooffsetofpulses,i.e.,from1-2minutes,3-4minutes,and5-6minutesofasevenminuteblock.Thetimebetweentwostimulation epochswassplitequallyintopost-andpre-stimulationepochs(see Figure1Aforanexample).Thepre-stimulation,duringstimulationandpost-stimulationarousalindexforablockreflectedthemaximumpossiblescoreacrosstherepetitions(repetitionslargely producedthesamescorewithineachepochtype).Priortoelectricalstimulations(exceptforararefewinstancestestingthevalence ofdifferentstimulationfrequencies),thearousalindexwas0or1.Thiscouldbedifferentiatedfromstimulationeventsinducing anarousalindexof3ormorebyallobservers.Thus,wedefinedeffectivestimulationeventsasthoseinducinganarousalindex of3ormore,whereasineffectivestimulationeventshadanarousalindexof0-2.Thebehavioralindicesusedtocomputethearousal scorearebasedonbehaviorsexhibitedbyindividualsrecoveringfromgeneralanesthesiaordisordersofconsciousness.Stimulation-inducedarousalscoresreflectdifferent(parallel)progressionsalongtherecoverysequence.

Electrophysiologicalrecordingandstimulation

FEFandLIPelectrodeshadeither16or24contacts,andCLelectrodeshad24contacts(MicroProbes).Theseplatinum/iridium electrodecontactshadadiameterof12.5 mm,and200 mmspacingbetweencontacts.Theimpedanceofcontactsonrecording electrodeswastypically0.8-1MU.WealsomeasuredtheEEGusingtitaniumskullscrewslocatedabovedorsalfrontoparietalcortex and,inanesthetizedexperiments,theEMGusingahypodermicneedle(30G)intheforearm.Werecordedelectrodesignals(filtered 0.1-7,500Hz,amplifiedandsampledat40kHz)usingapreamplifierwithahighinputimpedanceheadstageandOmniPlexdata acquisitionsystemcontrolledbyPlexControlsoftware.

Weelectricallystimulatedusing24-contactelectrodearraysthathadpreviouslybeenusedseveraltimesasrecordingelectrodes (andnowhadlowerimpedance).Inearlystimulationtrials,wetitratedcurrent(tested100-300 mA,butbecause100-200 mAinduced arousal,therewereonlyasmallnumberof>200 mAcases),polarityoffirstphaseofbiphasicpulse(negative-orpositive-goingfirst phase),numberofelectrodecontactssimultaneouslystimulated(tested1,4,8and16contacts),andstimulationduration(15-60s). Forsubsequentelectricalstimulations,wesimultaneouslystimulatedvia16electrodecontacts(16mostventralcontacts),with 400 msbi-phasicpulsesof200 mA,foratotalof60sstimulationdurationforanygivenstimulationevent(experimentsincluded multiplestimulationevents).Wetypicallyperformedthreestimulationeventsatagivenfrequencywithinastimulationblockfor reproducibility,witharecoverytimeofatleastthestimulationeventdurationbetweenrepetitions,i.e.,stimulationsfrom1-2minutes, 3-4minutes,and5-6minutesofasevenminuteblock.Inouranalyses,weincludedallstimulationdatawithcurrentsfrom 100-200 mA.Stimulationeventduration,rangingfrom15-60s,didnotinfluencearousalindices,soweincludedalldurationsin ouranalyses.

Electrodearraylocalization

WeacquiredT1-weightedstructuralimageswithelectrodesheld insitu bythecustomizedguidetubes(Pigarevetal.,2009;Saalmannetal.,2007,2012).Whiletheactualelectrodeisnotvisibleintheimages,asusceptibility‘‘shadow’’artifactappears alongthelengthoftheelectrodewithawidthofapproximatelyonevoxel(0.5mm3,eithersideoftheelectrode).WetargetedelectrodestothalamocorticalROIsbasedontheindividualmonkey’sstructuralimages,usingastereotaxicatlasasageneralreference

(SaleemandLogothetis,2007).Were-positionedelectrodesasnecessaryandre-acquiredT1-weightedstructuralscansuntilelectrodeswereintheirdesiredlocationsinthethalamusandcortex.Offline,weregistered(6degreesoffreedom)theimageswithelectrodes insitu tothehigh-qualitystructuralimageacquiredpriortosurgery.Usingmeasurementsofelectrodedepthduringimaging andrecordingsessionsaswellastheimageofelectrodes insitu,wereconstructedrecordingandstimulationsitesalongelectrode tracks.Thalamicstimulationsites,specificallytheeighthelectrodecontactofthe16contactssimultaneouslyusedforelectricalstimulation(i.e.,middleofstimulatingarray),areshownononecoronalslice(sitescollapsedacrosstheanterior-posterioraxis)in Figure1 (monkeyR).

WefurthervalidatedthelocalizationofrecordingsitesinourthreethalamocorticalROIsusingfunctionalcriteria.Weconfirmed theFEFROIinaninitialexperimentusingelectricalstimulationatthefrontalrecordingsite,i.e.,lowcurrents(<100 mA)elicited eyemovements(Bruceetal.,1985).IntheLIPROIduringawakeexperiments,alargenumberofneuronsshowedtheclassical responsecharacteristicofperi-saccadicactivity.IntheCLROI,wefoundasubsetofneuronswithhighfiringrates(around 40-50Hz)intheawakestate,consistentwithaCLlocus(GlennandSteriade,1982;Steriadeetal.,1993).

WiththeaimofpositioningelectrodecontactsinallcorticallayersinFEFandLIP,weuseddepthmeasurementsderivedfrom structuralimagestoinitiallypositionelectrodearraysacrossFEFandLIPlayers(24contactswith200 mmspacingbetweencontacts correspondstoa4.6mmspan,and16contactscorrespondtoa3mmspan,whichgenerallyallowsforcontactsinsuperficial,middle anddeepcorticallayersfortracksnearperpendiculartothecorticalsurfaceorwithmoderateanglesfromperpendicular).Wefurther adjustedelectrodepositiontomaximizethenumberofcontactsshowingsingle-unitormulti-unitspikingactivity,andwevisualized evokedpotentialstoauditorytones,withmiddlelayersshowingearliestresponse.Wethenusedcurrentsourcedensity(CSD) analysistoattributecontactstosuperficial,middleanddeepcorticallayers(seesection‘‘CurrentSourceDensity[CSD]’’below).

Weperformedpost-mortemhistologytoreconstructelectrodetracksinonemonkey(inadditiontothereconstructionsusing structuralMRIandelectrodedepthmeasurementsinbothmonkeys).Afterfixingthebrainin10%neutralbufferedformalin,theright hemispherewascutintoapproximately5mmthickcoronalsections,embeddedinparaffin,thenthinlysectioned(8 mm).Around ROIs,westainedsectionswithHematoxylinandEosin,andvisualizedsectionsunderamicroscopetoconfirmelectrodetracks throughourROIs.

Werecorded282CLneurons,281FEFneuronsand282LIPneuronsintotal.ForCL,therewere181neuronsduringanesthesia; 101neuronsduringwakefulness;and83neuronsduringsleep.ForFEFsuperficial,middleanddeeplayers,therewererespectively 48,33and91neuronsduringanesthesia;37,22and50neuronsduringwakefulness;and37,22and42neuronsduringsleep.ForLIP superficial,middleanddeeplayers,therewererespectively38,34and91neuronsduringanesthesia;36,10and73neuronsduring wakefulness;and24,9and65neuronsduringsleep.Neuronsrecordedduringsleepwerealsorecordedduringthewakestate. Neuronsrecordedduringanesthesiawererecordedindifferentsessionsfromneuronsrecordedduringwakefulness/sleep.

Anesthesiaexperiments

Weusedeitherisoflurane(9sessions:5forMonkeyR,4forMonkeyW)orpropofol(9sessions:4forMonkeyR,5forMonkeyW)in anesthesiaexperiments,toensurethatresultswerenotdrug-specific,insteadreflectinggeneralmechanismsofanesthesia/consciousness.Thedurationofeachanesthesiaexperimentalsessionwas10-12hours.Weinducedanesthesiawithketamine(upto 20mg/kgbodyweight,i.m.),thenintubatedthemonkeyandinsertedanintravenouscatheter(s)forfluidanddrugadministration. Wemaintainedgeneralanesthesiainspontaneouslyrespiringmonkeyswithisoflurane(0.8%–1.5%on1L/minO2 flow)orpropofol (0.17-0.33mg/kg/mini.v.),andaclinicalanesthesiologist(A.R.)oversawstableconditionsthroughout.Wecategorizeddosesas lower(isoflurane<1%;propofol<0.23mg/kg/min),medium(isoflurane1%–1.19%;propofol0.23-0.26mg/kg/min)andhigher (isoflurane R 1.2%;propofol R 0.27mg/kg/min)withintheaforementionedrangesforstatisticalpurposes(see‘‘Quantification andStatisticalAnalysis’’section).Wepositionedmonkeysinthepronepositionwithinamodifiedstereotaxicapparatusatopasurgicaltable,withthemonkey’sheadimmobilizedbyfourrods(attachedtothestereotaxicdevice)thatslidintotheimplanthollows.We maintainedthemonkey’stemperatureusingaforced-airwarmingsystemandmonitoredvitals(endtidalcarbondioxide,respiration rate,oxygensaturation,heartrate,bloodpressureandrectaltemperature).

Eachexperimentalsessionhadtwoparts:thefirstpartinvolvedsimultaneousrecordingsfromFEF,LIPandCL(recordingsstarted atleasttwohoursafteranestheticinductionandketamineadministration),andthesecondpartinvolvedelectricalstimulationofCL duringsimultaneousrecordingsfromFEFandLIPwithoutchangingtheanestheticregimen.Weindependentlypositionedlinear multielectrodearraysineachROI,andallowedarraystosettlefor30minutespriortostartingrecordings.Microdrivescoupledto anadaptorsystemalloweddifferentapproachanglesforeachROI.Forbothpartsofexperiments,weinterleavedrestingstate epochsandthepassiveauditoryoddballparadigm.Duringthefirstpartoftheexperimentalsession,weperformedneuralrecordings atanumberofdifferentanestheticlevels,adaptingthedosetoreflectarangeofclinicallyrelevantanestheticdepths,e.g.,1%,1.1%, 1.25%and/or1.5%isoflurane,or0.2,0.225,0.25and/or0.3mg/kg/minpropofol,allowingdosingchangestostabilizebeforestarting thenextblockofrecordings(typicallyatleast30minutes).Duringthesecondpartoftheexperiment,weeitherelectricallystimulated usingthelinearmultielectrodearrayexistinginthethalamusorreplaceditwithanotherarrayinsertedalongthesametrajectoryto thesamedepth.Wefirststimulatedthalamicsitesatafrequencyof50Hz.Ifthisdidnotinducearousal,thenwemovedthestimulatingelectrodetoanewdepthinthethalamusinstepsof0.5-1mmdorsalorventralalongtheelectrodetrack,untilstimulation inducedarousal.When50Hzstimulationinducedarousal,wetestedadditionalstimulationfrequencies,i.e.,2,10or200Hz,orfurther depths(mappingtheareaofeffect).Theorderofstimulationfrequenciesgenerallyfollowedoneoftwopatterns:50Hzalternating e4 Neuron 106,1–10.e1–e12,April8,2020 Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Redinbaughetal.,ThalamusModulatesConsciousnessviaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex,Neuron(2020),https://

withoneoftheotherstimulationfrequencies;ormultiplerepetitionsofaparticularstimulationfrequency,followedbymultiple repetitionsofadifferentstimulationfrequency.

Inearlyexperiments,wetestedthalamicstimulationsatdifferentanestheticdosesbetween0.8%–1.3%forisofluraneand between0.17-0.3mg/kg/minforpropofol.Weobservedthalamicstimulation-inducedarousalforallbutthehighestdoses (i.e.,1.3%isofluraneand0.3mg/kg/minpropofol).Insubsequentisofluraneexperiments,weuseddosesbetween0.8–1.25% (M=1.04,SD=0.11)duringthalamicstimulation,andinpropofolexperiments,weuseddosesbetween0.17-0.28mg/kg/min (M=0.23,SD=0.03).Dataforalldoseswereincludedinanalysesandcontrolledforstatistically(see‘‘QuantificationandStatistical Analysis’’section).

Asanadditionalcontrol,wealsoseparatelystimulatedtheFEFandLIPusingthesamestimulationparametersasthoseusedinthe thalamus(10or50Hz).FEForLIPstimulationalonedidnotinducearousal.Stimulatingbothareaswouldhaverequiredconsiderable pilotingandadditionalexperimentation,andwasthusbeyondthescopeofthisstudy.

Awakeexperiments

Weperformed40awakeexperimentalsessions(18formonkeyR;22formonkeyW),eachsessionusuallyof2-4hoursduration.Monkeyssatuprightinaprimatechairwiththeirheadimmobilizedusingtheheadpostand/orfourrodsthatslidintothehollowslotsinthe headimplant.Awakeexperimentsweresplitintotwotypes(similartothetwopartsofanesthesiaexperimentalsessions);thosewith andwithoutthalamicstimulation.ExperimentswithoutstimulationinvolvedsimultaneousrecordingsfromFEF,LIPandCLacross multipleblocksofalltaskconditions.StimulationexperimentalsessionsinvolvedelectricalstimulationofCL,atdifferentfrequencies, duringsimultaneousrecordingsfromFEFandLIPacrossalltaskconditions.Duringeachtypeofexperiment,weinterleaved taskconditionsinvolvingreward(fixationandoddballfixation)withthosenotinvolvingrewards(restingstateandpassiveoddball). Thespecifictaskorderwasvariedrandomlyacrossdifferentexperimentalsessions.

Forelectricalstimulation,wepseudorandomlyappliedstimulationblocksofdifferentfrequencies,i.e.,10,50and200Hz.Because electricalstimulationofthethalamusat50Hzfrequency(orotherfrequencies)inawakemonkeysdidnotelicitanymovements(as observedduringeffectivestimulationeventsinanesthesiaexperiments),itisunlikelythattheeffectsof50HzstimulationofCLin anesthetizedmonkeyssimplyreflecteddirecteffectsonthemotorsystem.Rather,itsupportsthefindingthat50Hzstimulation effectsreflectedincreasedarousal.

Weperformedneuralrecordingsfrombrainareasimplicatedinawareness.Becausetheseareasarealsoinvolvedinselective attentionandoculomotorfunction,weaimedtoensuredifferencesbetweenwakeandanesthesiaresultswerenotrelatedtoattentionalorsaccadicprocesses.Tothisend,withinthewakestate,wecomparedrecordingsduringthefixationtasktorestingstate,as wellasrecordingsduringthepassiveoddballwithfixationtothatwithoutfixation.Foreachcondition(fixationtask,restingstate, oddballwithandwithoutfixation),weanalyzedepochs(atleast1sinduration)inwhichthemonkey’seyepositionwasstable,as verifiedusingtheeyetracker.Theseanalysesshowedneuraldatafromcomparedconditionstobequalitativelysimilar.Considering thesecontrols,tokeepwakeandanesthesiaconditionsassimilaraspossible,wecomparedwakeandanesthesiadatacollected duringconditionsinwhichtherewerenotaskdemands,i.e.,therestingstateandpassiveoddballconditions(notthefixation taskortheoddballwithfixation)inthedark.

Sleep

Duringawakeexperiments,monkeysattimeswouldfallasleep,particularlyduringconditionsnotinvolvingrewards,suchasthe restingstate.Online,weidentifiednon-rapideyemovement(NREM)sleepusingthefollowingcriteria:increaseddelta(1-4Hz)activity inEEG(comparedwithwake);extendedeyeclosure(recordingtimeswheneyesclosedandre-opened,tocomparewithsemi-automaticdetectionoffline);precedingperiodofdrowsinessindicatedbyslowdrooping/closingofeyelids;stopinfixationtaskperformance(ifcurrenttaskisfixationtask);andnoovertbodymovement.Offline,weidentifiedNREMsleepperiodsusingEEGand eyetrackerdata.Webandpassfiltered(1-4Hz;Butterworth,order6)EEGdataandappliedtheHilberttransform,tocalculatethe instantaneousdelta-bandamplitude.Fromtheresultingtimeseries,wedetectedtimesofrelativelyhighdeltaamplitudeusing thresholdstitratedforeachrecordingsession,becausethemeandeltaamplitudeandstandarddeviationcouldvarydepending ontherecordingsessionandtotalsleeptime.Foreachsession,weselectedthethresholdasthenumberofstandarddeviations fromthemeandeltaamplitudethatproducedatotalsleeptimeestimatethatcloselyresembledtheexpectedsleeptimebased ononlineNREMidentification,aswellastheofflinecalculationofthetotaltimewhenthemonkey’seyeswereclosed(usingtherecordedeyetrackertimeseriesdata).OfflineNREMsleepidentificationandtimestampingtheninvolvedautomateddetection ofextendedepochsacrosstherecordingsessionwhenboththemonkey’seyeswereclosedanddeltaamplitudewasabove threshold.TheseofflineNREMsleepdetectionsweresimilartomanualonlinedetections,andprovedreliablefordifferentrecording sessionsandmonkeys.

TheidentifiedsleepepochscorrespondedtoearlyphasesofNREMsleep(N1orN2,i.e.,lightsleep).Thus,monkeyswerenotat thesamedepthofunconsciousnessduringsleepastheywereduringgeneralanesthesiainourstudy.Thisnotwithstanding,we includedthespikeratedataduringearlyNREMsleep,asthisallowedustocomparetheinfluenceofconsciousandless-conscious statesonthesamesubsetofneurons(n=282)recordedinbothwakefulnessandsleep.Thisfurthersubstantiatedourcomparisonof spikingactivitybetweentheawakeandanesthetizedstates,activityrecordedfromtwodifferentsamplesofneuronsfromthe sameROIs(maintenanceofstableanesthesiaupto12hoursrequiredrecordingstotakeplaceinasurgicalsuite,whereasawake Neuron 106,1–10.e1–e12,April8,2020 e5

recordingstookplaceinthebehaviorallab).Becauselocalfieldpotentials(LFPs)reflectcombinedactivityfromaconsiderablylarger volume(comparedwithsingle-neuronactivity)(Katzneretal.,2009),LFPsrecordedatdifferenttimes,i.e.,awakeandduringanesthesia,aremorereadilycompared.Nonetheless,weincludeearlyNREMsleepLFPdataaswell,tofurthersubstantiatethealtered connectivityduringanesthesia(althoughacompleteaccountofsleepinfluenceonourthalamocorticalrecordingsisbeyondthe scopeofthisstudy).

Neuraldatapreprocessing

Wedefineddatasegmentsof1sduration(akintotrials)foranalysis.Intheawakestate,wefirstdeterminedstableeyeepochs(to matcheyebehaviorbetweenconsciousandunconsciousstates),i.e.,epochsstarting200msafterasaccadeandending200ms beforethenextsaccade.Next,wedividedstableeyeepochsintonon-overlapping1swindows.Intheanesthetizedandnon-REM sleepstates(wheneyesareclosed),wedividedalldataineachofthesestatesintonon-overlapping1swindows.

Welowpassfiltereddatato250HzforLFPs(Butterworth,order6,zero-phasefilter).Next,welinearlydetrendedLFPs,thenextractedartifactsfromLFPdata,byremovingsignificantsinewavesusingtheChronuxfunctionrmlinesc.Individualelectrodecontactswithsignalamplitudegreaterthan5standarddeviationsfromthemeanwereexcludedfromanalysis.Forpowerandcoherence analyses,wefurthercalculatedbipolarderivationsofLFPs,i.e.,thedifferencebetweentwoadjacentelectrodecontacts(excluding contactsthathadbeenremovedduetonoise),tominimizeanypossibleeffectsofacommonreferenceandvolumeconduction (Bollimuntaetal.,2008;Haegensetal.,2015;Trongnetrpunyaetal.,2016).

Webandpassfiltereddata250-5,000Hzforspikingactivity(Butterworth,order4,zero-phasefilter)andsortedspikesusingPlexon OfflineSortersoftware.Initialspikedetectioninvolvedthresholdingdataat>3standarddeviationsawayfromthemean.Wethen usedprincipalcomponentsanalysistoextractfeaturesofthespikeshapes.Finally,weusedtheT-distributionexpectationmaximizationalgorithmtoidentifyclustersofspikeswithsimilarfeatures.

Forneuraldataduringelectricalstimulation,therewasabriefartifactcausedbytheappliedcurrent.Toremovethisartifact,wefirst exciseda1mswindowaroundtheartifact,thenlinearlyinterpolatedacrossthiswindow.Next,weusedtheChronuxfunctionrmlinesctoremoveanysignificantsinewavesatthestimulationfrequency(wealsoperformedartifactremovalusingtheSARGEtoolbox (Erezetal.,2010),whichyieldedqualitativelysimilarresults).

Spikerate

Wecalculatedtheaveragespikeratein1swindows(duringstableeyeepochs)foreachneuron,intheawake,sleepand/oranesthetizedstates.Wedividedanesthetizedstatedataintoelectricalstimulationandnostimulationwindows.Forelectricalstimulation data,wecalculatedthespikerateduringthestretchesofdataunaffectedbythestimulation-inducedartifact.

Spiketiming

Foreachneuron,wegeneratedinterspikeinterval(ISI)histograms(1msbinwidth),fromwhichwederivedanindexofburstfiring propensityintheawakeandanesthetizedstates(Senzaietal.,2019).Weexcludedneuronswithverylowspikerate(<1Hz)from theburstindexanalysis,astheirISIhistogramshadtoofewsamples).Forthalamicneurons,theburstindexequaledtheproportion ofspikesoccurringwithin2-8ms(sumofspikesinthe2-8msbinsoftheISIhistogramdividedbythetotalnumberofspikes; Figure2D);wealsocalculatedindicesfor2-5,2-10and2-15msbins(forqualitativelysimilarresults).BecauseISIsinCLneuronal burstshavebeenreportedtocommonlyrangeupto6ms(lengtheningwithincreasingburstsize)(Laceyetal.,2007),weselected thenextaccommodatingwindowsize,2-8ms.Forcorticalneurons,theburstindexequaledtheproportionofspikesoccurring within2-15ms(sumofspikesinthe2-15msbinsoftheISIhistogramdividedbythetotalnumberofspikes; Figure2E);wealsocalculatedindicesfor2-10,2-20and2-30msbins.AlthoughithasbeenreportedthatLIPneuronshavealowtendencytoburstinthewake state(MaimonandAssad,2009),westillmeasuredchangesinspikingregularityacrossdifferentstates,byusingarelatively largerwindow,2-15ms(cf. CL),stillapplicableforfrontalcortex(Womelsdorfetal.,2014),toallowcomparisonsbetween corticalareas.

Currentsourcedensity(CSD)

Welocalizedelectrodecontactstosuperficial,middleordeepcorticallayersbasedoninverseCSDanalyses(Pettersenetal.,2006). Todothis,weusedtheCSDplottertoolboxforMATLAB(https://github.com/espenhgn/CSDplotter ;dt=1ms,corticalconductivity value=0.4S/m,diameter=0.5mm)forcalculatingtheinverseCSDinresponsetoauditorytonesinthepassiveoddballparadigm. Linearmulti-electrodearraysmeasuretheLFP, f,atNdifferentcorticaldepths/electrodecontactsalongthezaxiswithspacingh. ThestandardCSD,Cst,isestimatedfromtheLFPsusingthesecondspatialderivative.

LFPscanalsobeestimatedfromgivenCSDs,representedinmatrixformas F = F b C ,where F isthevectorcontainingtheNmeasurementsof f, b C isthevectorcontainingtheestimatedCSDs,andFisanNxNmatrixderivedfromtheelectrostaticforwardcalculation ofLFPsfromknowncurrentsources.TheinverseCSDmethodusestheinverseofFtoestimatetheCSD,i.e., b C = F 1 F.Forthestep

inverseCSDmethod(Pettersenetal.,2006)usedhere,itisassumedthattheCSDisstepwiseconstantbetweenelectrodecontacts, sothesourcesareextendedcylindricalboxeswithradiusRandheighth.Inthiscase,Fisgivenby:

where s istheelectricalconductivitytensor,and f(zj)isthepotentialmeasuredatpositionzj atthecylindercenteraxisduetoacylindricalcurrentboxwithCSD,Ci,aroundtheelectrodepositionzi.TheinverseCSDmethodoffersadvantagesoverthestandardCSD. TheinverseCSDmethodestimatestheCSDaroundallNelectrodecontacts,whereasthestandardCSDmethodyieldsestimates aroundN-2contacts.Further,thestandardCSDrequiresequidistantcontacts,whereastheinverseCSDmethoddoesnot,whichis advantageouswhendatafromanoisycontactmayneedtobeexcluded.WeusedthestepinverseCSDmethod,becauseitmay performbetterthanthedelta-sourceCSDmethodaselectrodecontactspacingincreases,andthesplineCSDmethodcanbemore sensitivetospatialnoise,e.g.,fromgaindifferencesbetweenelectrodecontactsorfromanexcludedcontact(Pettersenetal.,2006). Weidentifiedtheearlycurrentsinkinresponsetoauditorystimulationanddesignatedthebottomofthesinkasthebottomofthe middlelayers(aroundboundarybetweenlayers4and5).Weincludedtheelectrodecontactatthebottomofthemiddlelayersandthe twomoresuperficialcontactsasthemiddlelayers.ElectrodecontactsinFEForLIPsuperficialtothemiddlelayersweredesignated asbeinginthesuperficiallayers,whereasFEForLIPcontactsdeeperthanthemiddlelayersweredesignatedasbeinginthedeep layers.Layerassignmentswerecross-referencedtoreconstructionsoftherecordingsitesalongtheelectrodetrack(basedonmeasurementsofelectrodedepthaswellastheimageofelectrodes insitu)aswellastosingle-unitormulti-unitspikingactivity,which helpeddelineatetheborderbetweengrayandwhitematter.Weexcludedfromanalysiscontactsthatwerefoundtobelocated outsidetheROI.

PreviousstudiesgeneratedCSDdatainFEF(Chenetal.,2018)andLIP(Schroederetal.,1998)usingvisualstimulation(FEF:1 degreeofvisualanglesquareat60%contrast;LIP:diffuselight).OurCSDprofilesgeneratedwithauditorystimulationwereroughly consistentwiththesepreviousstudiesofFEFandLIPinsofarassensorystimulationelicitedearlysinksinmiddlelayers(whichwould bepredictedbasedonauditorystimulationactivatingmiddlecorticallayersrelativelyearly).

WealsoperformedCSDanalyses,inthecaseofrestingstaterecordings,usingLFPsignalsalignedtothetroughofdelta-band oscillationsrecordedfromtheelectrodecontactwiththehighestdeltapower(i.e.,thiscontactservedasthephaseindex)(Bollimunta etal.,2008;Funketal.,2016;Haegensetal.,2015).Thesedeltaphase-realignedCSDsshoweddifferencesacrosscorticallayers whichhelpedverifythatprobepositionsremainedstableacrossrecordingblocksthatdidnotincludeauditorystimuliofthepassive oddballparadigm.

Power

Wecalculatedpowerin1swindows(stableeyeepochs)foreverybipolar-derivedLFP,usingmulti-tapermethods(5Slepiantaper functions,timebandwidthproductof3,averagingoverwindows/trials)withtheChronuxdataanalysistoolboxforMATLAB(http:// chronux.org/)(Bokiletal.,2007,2010;MitraandBokil,2007).Noisytrials,sampleswithamplitudesthatexceeded4standarddeviationsfromthemean,wereremoved.Sinusoidalnoise,especiallyatstimulationfrequenciesand60Hz,wasremovedusingnotch filtersortheChronuxfunctionrmlinesc.Therewereanunequalnumberofwindowspercondition,duetodifferencesindatalength andnumberofstableeyeepochs.Becausethenumberoftimewindows(ortrials)affectsthepowerestimate(S(f)),webias-corrected powervalues(Bokiletal.,2007).Thebias-correctedpowerspectrum,B(f),isgivenby:

where n0 =2*K*N,whereKisthenumberoftapers(5)andNisthenumberoftimewindows.Toobtainpopulationvalues,wepooled thebias-correctedpowerestimatesfortheawakestateandagainfortheanesthetizedstate(separatelyforthenostimulation,effectivestimulationandineffectivestimulationconditions).

Coherence

Wecalculatedcoherenceusingmulti-tapermethods(5Slepiantaperfunctions,timebandwidthproductof3)withtheChronux toolbox.Noisytrials,sampleswithamplitudesthatexceeded4standarddeviationsfromthemean,wereremoved.Sinusoidalnoise, especiallyatstimulationfrequenciesand60Hz,wasremovedusingnotchfiltersortheChronuxfunctionrmlinesc.Weusedthe coherencemeasuretostudythetemporalrelationshipbetweenLFPs,orbetweenspikesandLFPs,withinandbetweenthethalamus, FEFandLIP.Thecoherenceisgivenby:

whereS(f)isthespectrumwithsubscripts1and2referringtothesimultaneouslyrecordedspike/LFPatonesiteandLFPatanother site.Thecoherenceisnormalizedbetween0and1,soitcanbeaveragedacrossdifferentpairsoftimeseries.Foreachpaired

Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Redinbaughetal.,ThalamusModulatesConsciousnessviaLayer-SpecificControlofCortex,Neuron(2020),https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.01.005

recording,wecalculatedthecoherencein1swindowsduringwhichthemonkey’seyeswerestable.Therewereanunequal numberofwindowspercondition,duetodifferencesindatalengthandnumberofstableeyeepochs.Becausethenumberof timewindows(ortrials)affectsthecoherenceestimate,webias-corrected/transformedcoherencevalues(Bokiletal.,2007).The transformedcoherence,T(f),isgivenby:

where n0 isthedegreesoffreedom;forourmulti-taperestimates, n0 =2*K*N,whereKisthenumberoftapers(5)andNisthenumber oftimewindows.Toobtainpopulationvalues,wepooledthetransformedcoherenceestimatesfortheawakestateandagainforthe anesthetizedstate(separatelyforthenostimulation,effectivestimulationandineffectivestimulationconditions).

Toensurethatchangesincoherencedidnotsimplyreflectchangesinpoweratgivenfrequencybands,weinvestigatedtherelationshipbetweenourpowerandcoherenceresults.Whilewedidfindthatanesthesiaincreaseddeltapoweranddecreasedpowerat higherfrequenciesforallcorticalareas,powerchangesduringthalamicstimulationwerebroadbandandtypicallysmallerforeffectiverelativetoineffectivestimulations(unlikecoherencechanges; FigureS3; TableS2).Thispoorcorrelationbetweenarousaland powerduringstimulationsuggeststhatpowerisunlikelytobedrivingstimulation-inducedchangesincoherence,andisnotakey componentoftheNCC.

QUANTIFICATIONANDSTATISTICALANALYSIS

Generalapproach

Weperformedstatisticalanalysesusinggenerallinearmodels(GLMs)inRviaRStudio,regressingtherelevantdependentvariableon allindependentvariables,interactions,andcovariates(Models1-21below).Weusedlinearmodels(LMinR)foreffectsthatvaried betweenallothereffects,yieldingTstatisticsforeachestimatedslope(b parameter).Effectsthatvariedwithinothereffectsofinterest wereestimatedusinglinearmixedeffectmodels(LMERinR),yieldingFstatistics,oraftercomputingdifferencescoreswithlinear models,yieldingTstatistics.RandomeffectsofLMERmodelsarerepresentedasgammaparameters,andallsimpleandmaineffectsarepresentedasbetaparameters,wheretheslopefortheeffectofinterestis b1.Pvaluesstemmingfromthesamefamilyof statisticaltests(modelsintendedtodescribethesameeffectindifferentpopulations)werecontrolledformultiplecomparisonsusing Holm’scorrection.

Tocomparedosesbetweenanesthetics,weseparateddosesintolower( 1),medium(0),andhigher(1)dosegroupswithinthe experimentalrangeusedforbothanestheticagents.Forisoflurane,lowerdoseswere<1%,mediumwere R 1%and<1.2%,and higherdoseswere R 1.2%.Forpropofol,lowerdoseswere<0.23mg/kg/min,mediumwere R 0.23and<0.27mg/kg/min,and higherdoseswere R 0.27mg/kg/min.Thisallowedustousecodeddose(DoseCode)asacovariateindependentofanesthetic.

Tocontraststimulationeffectiveness,wecodedstimulationsproducingarousal R 3aseffective(1)andthoseproducing arousal<3asineffective(0).Thisallowedustocompareneuraldynamicsacrossstimulationsthatreflectedclearchangesinthelevel ofconsciousnesswhilecontrollingforchangesthatmaybeinducedonlybyintroductionofthalamiccurrent,whichwasthesamefor ineffectiveandeffectivestimulations.

Tolimitthenumberofmultiplecomparisonsacrossfrequency,weaveragedpowerandcoherenceacrosscanonicalfrequency bands:delta=0-4Hz,theta=4-8Hz,alpha=8-15Hz,beta=15-30Hz,lowgamma=30-60Hzandhighgamma=60-90Hz.As acontrolforpossibleartifacts,wealsoaveragedmoreselectivelywithinthelowgamma(across30-47and53–57Hz)andhigh gamma(63-90Hz)bands,soasnottoincludedataat50Hz,thefrequencyofthalamicstimulation,and60Hz,thefrequencyofpower linenoise,producingsimilarresults.

Stimulationeffects

Totestthegeneraleffectofthalamicstimulationonarousal(Figure1B),weregressedarousalscorewithinstimulationblocksonthe peri-stimulationepoch(pre,stimulation,post),includingdoseandanestheticascovariates.Peri-stimulationepoch(StimEpochF) wasdummycodedasafactorreferencedtotheepochwithstimulation,anestheticwascodedasacentereddichotomousvariable (isoflurane= 0.5,propofol=0.5),anddosewastreatedasDoseCode.Weincludedrandomslopesonlyforstimulationepochs,as doseandanestheticremainedconstantwithinagivenstimulationevent.Significantlynegative b1 showsthatoutsideofstimulation, arousalscoreislowerevencontrollingfortheeffectsofdoseandanesthetic.

ArousalScore b0 + b1 StimEpochF + b2 DoseCode + b3 Anes (Model1)