https://ebookmass.com/product/sustainable-biofloc-systems-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Marine Ecology: Processes, Systems, and Impacts 2nd Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/marine-ecology-processes-systems-andimpacts-2nd-edition/

ebookmass.com

Systems Biogeochemistry of Major Marine Biomes Aninda Mazumdar

https://ebookmass.com/product/systems-biogeochemistry-of-major-marinebiomes-aninda-mazumdar/

ebookmass.com

Vermicomposting for Sustainable Food Systems in Africa 1st Edition Hupenyu Allan Mupambwa

https://ebookmass.com/product/vermicomposting-for-sustainable-foodsystems-in-africa-1st-edition-hupenyu-allan-mupambwa/

ebookmass.com

(eTextbook PDF) for Criminal Justice in Action: The Core 9th Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/etextbook-pdf-for-criminal-justice-inaction-the-core-9th-edition/

ebookmass.com

Financial

Eugene F. Brigham

https://ebookmass.com/product/financial-management-mindtap-1-termprinted-access-card-eugene-f-brigham/

ebookmass.com

003 - Die tödliche Stille Roxann Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/003-die-todliche-stille-roxann-hill/

ebookmass.com

Schaum's Outline of Calculus, 7th Edition Elliott Mendelson

https://ebookmass.com/product/schaums-outline-of-calculus-7th-editionelliott-mendelson/

ebookmass.com

Prisons, Politics and Practices in England and Wales 1945–2020: The Operational Management Issues Cornwell

https://ebookmass.com/product/prisons-politics-and-practices-inengland-and-wales-1945-2020-the-operational-management-issuescornwell/ ebookmass.com

Financial Management for Public, Health, and Not-forProfit Organizations Fifth Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/financial-management-for-public-healthand-not-for-profit-organizations-fifth-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-shards-a-novel-bret-easton-ellis/

ebookmass.com

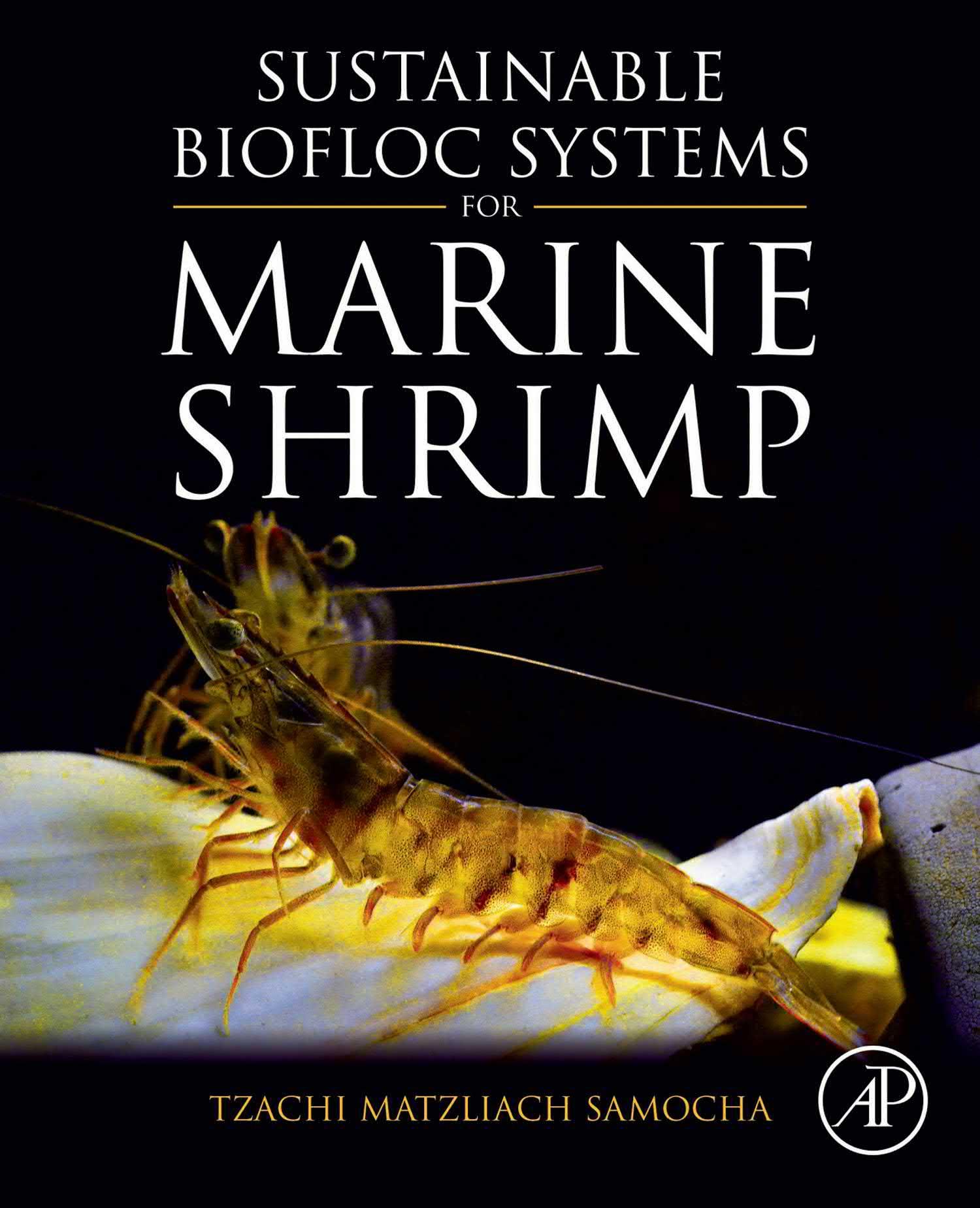

SUSTAINABLEBIOFLOCSYSTEMSFOR MARINESHRIMP

SUSTAINABLE BIOFLOC SYSTEMSFOR MARINESHRIMP

TZACHI MATZLIACH SAMOCHA

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier 125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom ©2019ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic ormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem, withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,further informationaboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizations suchastheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatour website: www.elsevier.com/permissions

Thisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythe Publisher(otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperience broadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedical treatmentmaybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgein evaluatingandusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.In usingsuchinformationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyof others,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors, assumeanyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproducts liability,negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products, instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN978-0-12-818040-2

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublicationsvisitour websiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: CharlotteCockle

AcquisitionEditor: PatriciaOsborn

EditorialProjectManager: LauraOkidi

ProductionProjectManager: PremKumarKaliamoorthi

CoverDesigner: AlanStudholme

TypesetbySPiGlobal,India

Contributors

LeandroF.Castro ZeiglerBros.Inc.,Gardners,PA, UnitedStates

TerryHanson SchoolofFisheries,Aquacultureand AquaticSciences,AuburnUniversity,Auburn,AL, UnitedStates

IngridLupatsch ABAgriLtd.,Peterborough, UnitedKingdom

DavidI.Prangnell TexasParksandWildlife Department,SanMarcos,TX,UnitedStates

TzachiM.Samocha MarineSolutionsandFeed Technology,Spring,TX,UnitedStates

NickStaresinic aquacalc@gmail.com

GranvilD.Treece Treece&Associates,Lampasas, TX,UnitedStates

Listoffigures

Fig.1.1 Belizeaquaculture. 4

Fig.1.2 Productionatoutdoorshrimp bioflocfarms. 5

Fig.1.3 Traditionalfarmcomparedto thearearequiredforcomparable super-intensiveproduction [red area—(lightgraysquareinprintversion)]. 6

Fig.1.4 Biofloctechnologyinpracticeat WaddellMaricultureCenterin Bluffton,SouthCarolina,USA. 7

Fig.1.5 AmericanMariculture,Inc.on PineIsland,Florida,USA. 9

Fig.1.6 FloridaOrganicAquaculture’s indoorbioflocshrimpculture raceways. 9

Fig.1.7 GlobalBlueTechnologieshatcheryand grow-outcellsnearRockport,Texas, USA. 10

Fig.1.8 Commercialshrimpnurseryin Texasusingbiofloc.Theeight concreteracewaysaremodeled onthe100-m3 TexasA&MARMLraceways. 10

Fig.1.9 Indoorshrimpproduction facilityinMedinadelCampo, Spain. 11

Fig.1.10 Indoorproductionfacilityfor L.vannamei inChina. 11

Fig.1.11 TheGanixBlueOasisfarmin LasVegas,Nevada,USAwas veryshortlived. 12

Fig.1.12 Cumulativedistributionoftotal cost($/kg)forearthenponds vs.RAS. 13

Fig.2.1 Lateralviewoftheexternal morphologyofageneralized penaeidshrimp. 20

Fig.2.2 Externalgenitaliaofgeneralized adultpenaeidshrimp, (A)petasma(male),(BandC) thelyca(female). 20

Fig.2.3 Lateralviewoftheinternal morphologyofanadultfemale

penaeidshrimp(“shrimp-culture. blogspot.com”). 21

Fig.2.4 Typicallifecycleofpenaeid shrimp. 21

Fig.3.1 Appearanceofthewater surface (left) andamicroscopicviewof abioflocaggregate (right) froman indoor,biofloc-dominated productionsystem. 30

Fig.3.2 Morphologyofthethird maxillipedinthreepenaeidspecies: (A) Litopenaeusvannamei, (B) Fenneropenaeuschinensis, (C) Marsupenaeus japonicus.ScaleBar:0.5mm.

33

Fig.3.3 Ascanningelectronmicrograph showingthenet-likestructureof thethirdmaxillipedofPacific WhiteShrimp. 34

Fig.4.1 Supplycanallinkedtothe coastallagoonfromwhichthe TexasA&M-ARMLandTexas ParksandWildlifeLaboratory drawwater. 38

Fig.4.2A TheMarineNitrogenCycle. Featuresofparticularimportance toaquaculturethatarediscussedin thetext.Ammoniaproducedby shrimpandsomebioflocbacteria(8) isconvertedbyammonia-oxidizing bacteria(4&9)intonitrite.Nitriteoxidizingbacteria(5&11)convert nitritetonitrate.Together,these processesarereferredtoas nitrification andoccurin oxygenatedenvironments.Under anoxicconditions,denitrifiers(13) andanammoxmicrobes(10) followdifferentpathwaysto producenitrogengasthatislost totheatmosphere,thus removingnitrogenfromthe system.

42

Fig.4.2B TheBasicNitrogenCycleina MixotrophicBiofloc-DominatedSystem. Shrimpingestprotein-nitrogenfrom formulatedfeed(1)andbiofloc(6)to supportgrowthandbuildbiomass.They excretemainlyammonia(2)thatis assimilatedbybothheterotrophicand autotrophicflocbacteria(3). Theheterotrophsbuildbacterialbiomass andtheautotrophsnitrifyammoniain twosteps:firsttonitrite(4)andthento nitrate(5).Theautotrophicnitrifiers producefarlessbacterialbiomass. Withoutadenitrifyingprocess,nitrate accumulatesinthesystem. 44

Fig.4.3 Thetypicalpatternofammonia,nitrite, andnitrateconcentrationsinanewly startedsystem,demonstratinghow ammonia-oxidizingbacteriadevelop soonerthannitrite-oxidizingbacteria (leadingtonitritebuildup),and theaccumulationofnitratewhenthereis insufficientdenitrificationorwater exchange. 51

Fig.4.4 Organicmatter(biofloc)removedfrom asystembyafoamfractionator. 53

Fig.5.1A Open-walledtank. 62

Fig.5.1B GreenhouseusedattheTexas A&M-AMRL. 63

Fig.5.1C Inflatedair-supportedstructure. 63

Fig.5.1D Alargewoodenstructureused byFloridaOrganicAquaculture, Fellsmere,FL. 63

Fig.5.1 A2500-m3 reservoirpond (left) and36-m3 mixingtank (right) attheTexasA&M-ARML. 64

Fig.5.2 Concreteharvestbasinsatthe TexasA&M-ARML(A)andat BowersShrimpFarm,Palacios,Texas, US(B). 64

Fig.5.3 Airblowersinflatedouble-layer polyethylenegreenhouseroofsatthe TexasA&M-ARML. 67

Fig.5.3A Roundfiberglasstanksused attheTexasA&M-ARML. 70

Fig.5.3B Rigidpolyethylenetanks. 70

Fig.5.3C RacewaylinedwithEPDMmembrane. 72

Fig.5.3D Corrugatedroundtanklined withpolyethylene.

Fig.5.4 Backupdieselgenerators (30kWand250kW)installedat aquaculturefacilities.

Fig.5.5 Airpressuregauge.Noteinstallationof a5-cmPVCvalveforpressure regulation.

Fig.5.6 Positivedisplacementblowerwithbelt drive(A)andregenerativeblowers(B) drivingdiffusersandairliftsinthe TexasA&M-ARML40m3 raceways. Blowershaveinletfilters.

Fig.5.7

78

Silicaairstones(A),diffuser hose(B)(blackhosewith blue line)(lightgrayline inprintversion), andmicro-bubblediffuser (ceramicplate)(C).

Fig.5.8

72

75

77

79

Schematics(A,B,D)andphoto (C)ofanairliftintheTexas A&M-ARML40m3 raceways. Airisinjectedviaapolyethylene hoseatthebaseofa5-cmPVCpipecut inhalflength-wise. 81

Fig.5.9 SchematicofaVenturi injector.Air-oxygenisdrawnintothe flowatthepointofrestriction. 81

Fig.5.10 Schematicofa3 injector.45-psiwater (bluearrow) (darkgrayarrow inprint version)mixeswithair (dashed-line arrow) 82

Fig.5.11 Pureoxygensupply;(A)Liquidoxygen bottle(LOX),(B)Compressedoxygen cylinders,(C)Oxygengenerator. 83

Fig.5.12 Speececone. 84

Fig.5.13 Diagramofasimpleconical settlingtank. Redarrows (light gray inprintversion):water fromculturetank. Bluearrows (darkarrow inprintversion): waterreturntotank.

85

Fig.5.14 Hydrocyclonefilter. 87

Fig.5.15 Aswirlseparator. 87

Fig.5.16 Left photo—PressurizedSand Filterwithsandusedfor filtration; Right photo—Poly Geyserbeadfilterwith beadmedia. 88

Fig.5.17 Drumfilter. 88

Fig.5.18 Beltfeedersplacedover shrimpproductionraceways. 89

Fig.5.19 Evenlyspacedbeltfeedersmountedon walkwaysoveraraceway,andasingle beltfeedermountedonthesideofa culturetank. 90

Fig.5.20 Somemeasurestoprevent entryofunauthorized personnelandpredators: (A)walls,(B)electrifiedwire, (C)motiondetector,(D)predatortrap. 90

Fig.5.21 Flow-injectionanalyzerusedto measureammonia,nitrite,nitrate,and phosphateattheTexasA&M-ARML. 92

Fig.5.21A Agreenhousewithsix40m3 raceways atTexasA&M-ARML.Corrugated fiberglassonfrontwall(A),oneofthree garagedoors(B),outsideviewoffanshutter(C),insideviewoffan(D),open sidewall(E)rolled-up(F)androlleddown(G),electrifiedwiresontheside wall(H)withacontroller(I),andshade clothcoveringtheroof(J). 96

Fig.5.22 Photosof40m3 racewaysandsupport systems:(A)antijumpnetting, (B)freeboard,(C)boardwalk,(D)belt feeder,(E)centerpartition,(F)three5-cm airlifts,(G)accessdoor,(H)

2.5-cmPVCairdistribution pipe,(I)ropesforpositioningcenter partition. 97

Fig.5.23 Top-viewschematicdrawingof40m3 racewaywithsupportsystems. 98

Fig.5.24 Close-up(A)andgenerallayoutofthe raceway’scenterpartition(B);center partition(a),weightmadeof3.8-cm PVCpipeabovespraypipe(b),5-cm PVCspraypipe(c),partitionsupport (d),ropeholdingthepartition(e). 99

Fig.5.25 Spraynozzleinbottomspray pipe:(A)completeset,(B) assemblywithoutspraytip,(C)street adapter. 100

Fig.5.26 Two-hppumpwith5-cmPVC pipenetworkandvalvesof40m3 raceway;(A)waterfromraceway, (B)waterfromreservoir,(C)waterto raceway,(D)watertoevaporation pond,(P)pump. Bluelines (dotted dark grayline inprintversion)show directionofflow. 100

Fig.5.27 Aphotoof40m3 raceway showing(A)5-cmPVCairdistribution pipe,(B)2.5-cmPVCairdeliverypipe, (C)1.6-cmflexibleairsupplyhosesto airliftpumpsanddiffusers,(D)1.6-cm PVCballvalvecontrollingairsupplyto airliftanddiffusers,(E)bottom spraypipewithspraynozzleand diffuser,(F)boardwalk,(G)center partition,(H)ropeholdingpartitionin place.

Fig.5.30 Settlingtanksfor40m3 raceway system:(1)sideview,(2)topview, (3)allsixsettlingtanks:(A)sleeve preventingmixingofwater enteringandleavingthetank, (B)woodensupport,(C)tanklid, (D)1.6-cmsupplyhose,(E)1.6-cm PVCsupplyvalve,(F)5-cmPVCreturn pipe,(G)5-cmPVCdrainvalve. 104

Fig.5.31 Foamfractionatorinthe40m3 raceway: (A)5-cmPVCvalveonpump dischargepipe,(B)1.6-cmPVCvalve controllingwatersupplytofoam fractionator,(C)1.6-cmPVCvalve controllingwatersupplytosettling tank,(D)1.6-cmhoseconnectingvalve andfoamfractionator,(E)oneoftwo 2-cmVenturiinjectors,(F)clearacrylic tube,(G)2.5-cmPVCgate-valve controllingflowfromfoamfractionator toracewayvia2.5-cmflexiblehose (H),(I)foamfractionatordrainvalve, (J)separationtank.

Fig.5.32

101

Fig.5.28 Venturiinjectorassembly:(A)oxygen flowmeter,(B)oxygensupplyvalve, (C)oxygensupplyhoses,(D)check valve,(E)airintake. 102

Fig.5.29 YSI5500DDOmonitoringsystem: (A)on-sitedisplay,(B)computer displaywithaudio,(C)optical probe,(D)programmingand screenshotofalarm-settingsoftware. 103

105

Multicyclonemountingandvalve arrangementin40m3 raceway:(A)5-cm PVCdischargepipe,(B)1.6-cmPVC valvecontrollingsupplytofoam fractionator,(C)1.6-cmPVCvalve controllingsupplytosettlingtank, (D)multicyclonefilter,(E)5-cmPVC valvecontrollingsupplytomulticyclone filter,(F)wastedrainvalve. 106

Fig.5.33 Separationtankswithdrying biofloc(A),afalse-bottomiscreatedby placingawoodenframe(B),covered withchickenwire(C),andcoveredbya geotextilemembrane(D),orburlap cloth(E)forwaterseparation,with hosereturningwaterbacktothe raceway(F)viaanoutletatthebottom ofthetank(G). 106

Fig.5.34 Drybioflocinaseparationtank. 107

Fig.5.35 Greenhousefortwo100m3 racewayswithdouble-layer inflatedroofcoveredbyblack shadecloth(A),inflated double-layerwovenpolyethyleneside(B)andend-walls(C),garagedoor (D),sidedoor(E),exhaustfan(F). 107

Fig.5.36 Schematictopviewofthe100m3 raceway.

Fig.5.37 100m3 raceway:Antijumpnetting (A),5-cmPVCdistributionpipes (B),2.5-cmPVCa3 watersupply pipe(C),boardwalk(D),center partition(E),accessdoor(F), beltfeeders(G).

108

109

Fig.5.38 Two2-hpcentrifugalpumpsfora 100m3 raceway.The5-cmPVC valvemanifoldcontrolssingleordual pumpuse.Valvehandlesarepaintedto reduceUVdegradation. 109

Fig.5.39 Asaddleforapaddlewheelflowmeter (A),oneoftwo-5cmPVCdistribution pipesfeedingsevena3 injectorsineach raceway(B),screenedpumpintake (oneoftwo)noteguardnetontopof thefilterpipe(C),boardwalk(D), freeboard(E),antijumpnetting(F),and racewayfootingsupportingantijump netting(G). 110

Fig.5.40 Waterandairflowofa3 injectorfor aerationandmixinginthe100m3 raceway:Oneoftwo5-cmPVC distributionpipes(A),2.5-cmPVCball valvecontrollingwatertoinjector (B),2.5-cmPVCbarrelunionadapter (C),2.5-cmwatersupplypipe (D),2.5-cmairsuctionpipe(E),a3 injector(F),airbubbleandwater mixturestreamingoutofinjector (G),boardwalk(H),5-cmballvalvefor quickfillofraceway(I). Bluearrows (darkgrayarrows inprintversion):high pressurewatersupply; Redarrows (dottedlightgrayarrows inprint version):atmosphericairsuction. 111

Fig.5.41 Oxygenbackupsystem:aquarium hose(A)deliversoxygentoa3 suction pipe(B). 111

Fig.5.42 Centerpartition:EPDMgluedtobottom andsupportedbyropesconnectedto 5-cmcappedflotationpipe.20-cmPVC concrete-embeddedelbowconnectedto harvestbasin(A),boltingEPDM membraneintoconcretewith stainless-steelframe(B). 112

Fig.5.43 Afullandemptyraceway.Notice freeboardinthefullraceway. 112

Fig.5.44 Racewayfilledtoworkingdepth with20-cmPVCstandpipe extendingabovethesurface (A).Netpreventsshrimplarger than1gfromenteringthedrain line(B). 113

Fig.5.45 (1)2-m3 outdoorfiberglasssettlingfor oneraceway;(2)topviewofsettling tank;(3)pipingsystematshallowend ofraceway;(4)5cmPVCpipe returningwaterfromsettlingtankto

raceway:(A)sleevetopreventmixing ofwaterenteringandleavingsettling tank,(B)1.6-cmhosedeliveringwater fromracewaytosettlingtank, (C)1.6-cmvalvecontrollingflowto settlingtank,(D)5-cmPVC distributionpipe,(E)5-cmPVC pipereturningwaterfromsettlingtank toraceway,(F)2.5-cmPVCvalve feedinga3 injector,(G)5-cmPVCvalve toquicklyfillraceway. 113

Fig.5.46 (1)Homemadefoamfractionator, (2)schematicoffoamfractionator: (A)30-cmPVCpipe,(B)10-cmacrylic pipe,(C)5-cmPVCfoamdeliverypipe, (D)temporaryfoamstoragetank, (E)2.5-cmPVCballvalvecontrolling flowtofoamfractionator,(F)a3 injector, (G)2.5-cmPVCairintakepipe, (H)2.5-cmPVCgatevalvecontrolling returnflowtoraceway. 114

Fig.5.47 Concreteharvestbasin.(A)5-cm PVCoutletfordrainingtheracewayby pump,(B)15-cmPVCthreadedoutlet (oneoneachsidewall)forconnectinga fishpump,(C)nested20-cmPVCfilter pipespreventcloggingthedischarge linewithforeignobjects,(D) safetywoodengridontopofthe structure. 116

Fig.6.1 Filterbagonseawaterinletof TexasA&M-AgriLifeResearch MaricultureLab. 120

Fig.6.2 Pressuresprayingracewayswith freshwatertoremoveorganic matter. 120

Fig.6.3 Venturiinjectorforadding disinfectantstoareservoir.Asthe middle5-cmvalveisclosed,thesuction pressurethroughtheVenturiincreases. 121

Fig.6.4 Liquid(12.5%)sodium hypochloriteina200-L(55-gal.) drumwithasiphonpump. 122

Fig.6.5 Chemicalstorageincontainment traystolimitspills. 122

Fig.6.6 Disinfectingaracewaywithchlorine solutionspraywhilewearing protectiveequipment. 124

Fig.7.1 Amodifiedcontainerusedto dripachemicalsolutionintoa culturetank. 137

Fig.7.2 One-literImhoffconesusedtomeasure settleablesolids. 141

Fig.7.3 Racewayfilledwithnewwater (clear)withlowbioflocandlow turbidity (left) andaracewaywith maturedbioflocwaterwithhigh turbidity (right) 142

Fig.7.4 Harvestedshrimpbeingdissected, dried,andgroundforionic compositionanalysis. 144

Fig.7.5 MicrobialCommunityColorIndex (MCCI)indicatingthetransition fromanalgaltoabacterialsystemas feedloadincreases.Thetransition occursatafeedrateof300–500kg/haperday(30–50g/m2 per day),indicatedbyanMCCI between1and1.2. 148

Fig.7.6 Racewayswithalgaldominatedwater. 148

Fig.7.7 Filterscreenssurroundingthe pumpintakestandpipeoftwosystems toprevententrapmentofPL.An aerationringmountedatthebaseofthe pumpintakeofthe40m3 raceway (left) aidsscreencleaning(theopeningat thetoppreventsdamagetoPLand cavitation). 149

Fig.7.8 BottomandbioflocPVCmixing tool. 150

Fig.7.9 Mixingaracewaymanually. Notetheunevendistributionofbiofloc onthesurface.

Fig.8.1 Postlarvaegradingfromalarval rearingtank(A),transferintoa bucket(B),placementinsideacageina tankwithpureoxygensupply (C),collectionofthesmallPLfrom outsidethecage(D),andtransferintoa newtank(E).

Fig.8.2 In-tankPLseparation.(A)collectingPL withadipnetfromthelarvalrearing tank(C)andtransferintoafloating cagemadefromnettingwithamesh sizethatallowssmallPLtopassback intothetank.

Fig.8.3 Smallerpostlarvae(A)remaining afterremovaloflargerpostlarvae (B)fromthesamelarvalrearing tank.

Fig.8.4 Shippingpostlarvaeinoxygen-inflated plasticbags(A)andpackedin Styrofoamboxes(B).

150

154

155

155

156

Fig.8.5 AcclimatingPLsinhaulingtanks. 157

Fig.8.6 Small-tankacclimationshowinga hand-heldmonitorwith

multiprobeandshippingbagwith PLfloatinginoxygenatedwater(A). Bagsareopened,attachedtothesideof thetank,andprovidedwithanoxygen andairsupplyforeachbag(B).Water fromtheacclimationtankisadded graduallytoashippingbag(C).

157

Fig.8.7 Standpipeinacclimationtankis removedtoletPLdrainbygravityinto thenurserytank(A),Noteairsupplyto theacclimationtank(B). 159

Fig.8.8 SamplingPLinanacclimationtank. Notemixingbytwopeopleand transferofthesample(A)toa 1-Lcontainer(B). 160

Fig.8.9

ObservationandcountingofPLin samplescollectedfromacclimation tanksorshippingbags.General observationsofswimmingactivity, deadPL,andpredationaredonein aglassjarorbeaker(A).Counting isdonebypouringsmallquantitiesofPL onastretched350-μmmeshwhitescreen (B)orframedscreenwithmarkedgrid (C),orbypouringthemintoaflatwhite tray(D).Hand-heldcounter(E). 160

Fig.8.10 TopviewofPLsamplingtank withbottomaerationgrid.

161

Fig.8.11 Spoutlesssamplingcups(A)compared witharegularbeakerwithspout(B). 161

Fig.8.12 MetalstrainerforquantifyingPL. 163

Fig.8.13 Imageofpostlarvatailshowing half-emptygut. 165

Fig.8.14 Highsizevariationofpostlarvae inanursery. 166

Fig.8.15 Exampleofawidesizedistribution inanursery(averageweight SD: 143 118mg/individual,CV:83%, min:23mg/individual,max:600mg/ individual).Eachcolorrepresentsa feedsizeappropriateforasize class:6%of0.4to0.6mm,36%of 0.6to8.5mm,56%of1mm,and3% of1.5-mmdrypellets(Zeigler Bros.,Inc.). 167

Fig.8.16 Suggesteddailyfeedrationsand particlesizebasedonwater temperature,survival,stocking density,andassumedfeedconversion ratioasusedinanurserytrialatthe TexasA&M-ARML.Suggestedfeeding tablewasprovidedbyZeiglerBros., Inc.,Gardners,PA,US. 168

Fig.8.17 Typicalshrimpnurseryfeed labels. 169

Fig.8.18 Datarecordingstation(A), preweighingconveyor(B) postweighingconveyor(C),and anelectronicbalancebetweenthetwo conveyors(D)withremotedisplay(E). 175

Fig.8.19 Fishbasketforharvestingsmall juvenileshrimp(A);basketfor weighinglargejuveniles(B);aclose-up offishbasketwalllinedwith1mmnet (C);afishbasketwithalid(D),and handle(E). 176

Fig.8.20 Harvestbyswivelstandpipe. 178

Fig.8.21 Dewateringdevice(A)andclose viewofadewateringrack(B)of afishpump. 179

Fig.9.1 Pumpintakefilterscreenpipe(A), pumpintake(B),andaerationring(C). 182

Fig.9.2 The5-cmPVCscrewcapofthe bottomspraypipeatthe raceway’sdeepend. 183

Fig.9.3 The5-cmPVCvalvecontrolling waterflowintotheVenturi injector. 183

Fig.9.4 The5-cmbleedvalvecontrolling waterflowintothebottom spraypipe. 183

Fig.9.5 Anairdiffuserattachedtothe bottomspraypipe. 183

Fig.9.6 Watersupplyto100m3 raceway: 5-cmvalvesfeedingtheprimarya3 injectorsupplypipeandthe cyclonefilter(A).A2.5-cmvalve controllingwaterflowtoeacha3 injector(B).Theinjectorassembly (C).A5-cmquick-fillvalveatthe endofeachofthetwoprimary watersupplypipesineachraceway (D),andapressuregagerequiredto ensureadequatewaterpressureto operatetheinjectoratmaximum efficiency(E). 184

Fig.9.7 Effectof20%improvementin biologicalorpricefactorson10-year NetPresentValue(NPV)ofa super-intensivebioflocPacific WhiteShrimpproduction (Hansonetal.,2009).

Fig.9.8 Feedbagsstackedonawooden palletandwrappedin shrink-wrap.

Fig.9.10

Placementofbeltfeedersina 100-m3 TexasA&M-ARMLraceway. 192

Fig.9.11 Left and middle:Castnetusedina confinedspacetomonitorgrowthina 100-m3 tank; Right:Castnetusedinan openarea. 193

Fig.9.12

Fig.9.13

Fig.9.14

SamplingprocedureattheTexas A&M-ARML:(A)Prepare materials;(B)Tarebucket; (C)Spreadthecastnet. 194

Shrimpwithsignsthatindicateculture problems. 195

Shrimpwithsuboptimal(1)and optimal(2)gutfullness.

Fig.10.1 Vividappearanceoffreshlychill-killed shrimp(A)comparedtostressedor deadshrimpthathavebeenchilled(B).

195

202

Fig.10.2 Containers,materials,andtools forharvestattheTexasA&M-ARML: (A)tablewithsamplingsupplies, (B)taredharvestbaskets,(C)harvest usingalong-handledipnet,(D)harvest basketfilledwithshrimp,(E)splashprotectedelectronicbalance,(F) weighingwithhangingelectronic balance;notelidonbasket,(G)basket transferbyfour-wheeler,(H) insulatedharvesttote,(I)chill-killtanks withicewater;shrimpinbaskets,(J) plasticsiftingscoop. 202

Fig.10.3

Fig.10.4

Fig.10.5

Astandpipeinthe20-cmdrain outletduringnormaloperation(A). Thestandpipeisremovedbefore operatingthefishpump.Also shownaretwoscreenedpumpintakes inanempty (rightpicture) anda half-fullraceway(B). 204

Threaded15-cmoutletinthe harvestbasinsidewallabovethebottom (A)andafilterpipetopreventforeign objectsfromenteringthedrainline(B). 205

Nonsubmersible(A)andsubmersible (B)fishpumpwithhydraulichoses, hydraulicpowerpack(C)withelectric motor(1),hydraulicpump(2),and hydraulicoiltank(3). 205

Fig.10.6

186

187

Fig.9.9 Typicalfeedbaglabels. 188

Fishpumpconnecteddirectlyto theracewayoutletonthesidewall oftheharvestbasin(A).Waterfrom thedewateringtowerreturnsto theharvestbasinviathebluehose (B)andshrimparecollectedina harvestbasket(C). 206

Fig.10.7 (A)Funnelingshrimpfromthe dewateringtower(1)intoharvest basketwithlid(noteuseoffeedbagas adisposablechute),(B)dewatering towerwithsteps(1)foreasyaccess, (C)hoseconnectingthefishpumpto thedewateringtower(1)with powerrack(2),(D)fishpumpregulator (1)andhydraulichoseconnectors (2and3). 207

Fig.10.8 Ashrimptrapusedforlive harvest. 207

Fig.10.9 (A)DC-poweredsubmersible pumpwithprotectivenettingand aspraybarinsidea600-Llive-haul tank,(B)thepumpandspraybar, (C)watermixingbypump. 208

Fig.11.1 Settledsolidslevelfroman anaerobicdigestermeasuredwith aclearsamplingtube. 213

Fig.11.2 Stagesinadenitrification digester.Thesemaybelocatedin separatetanksorseparate compartmentsinthesametank. 213

Fig.11.3 Artificialwetlandgrowing Salicornia sp.tofilterwaterfromashrimp system. 215

Fig.11.4 Subsurfaceflowinaconstructed wetlandfornutrientrecoveryof maricultureeffluent.Viewshows1.5% subsurfacegradeandwaterlevelwith respecttosurface. 216

Fig.11.5 Schematicandflowdiagramwith photosofHSSFconstructed wetlandfornutrientrecoveryof maricultureeffluent. 217

Fig.12.1 Shrimphealthinculturesystemsis affectedbymanyfactorsthatact togethertodeterminegrowth,survival, andFCR. 220

Fig.12.2 Shrimpwithfull(A)and partiallyfull(B)guts. 221

Fig.12.3 Shrimpwithseverediscolorationoftail segments(necrosis)suggesting Vibrio infection,infectiousmyonecrosis, ormicrosporidiosis. 221

Fig.12.4 Necrosis(deadtissue)onshrimp. 222

Fig.12.5 Shrimpmoltscollectedfromaraceway. 223

Fig.12.6 Monitoringshrimpsize variationisimportantinhealth monitoringandnecessaryforselecting anappropriate sizefeed. 223

Fig.12.7 Preservedjuvenile L.vannamei showingsignsofIHHNV-causedrunt deformitysyndrome:bentrostrums (left) anddeformityofthetailmuscle and6thabdominalsegment (right) 228

Fig.12.8 Juvenile L.vannamei showingsigns ofTaurasyndrome: red (darkgray inprintversion)tailfanwith roughedgesonthecuticular epitheliumofuropods (left) and multiplemelanizedcuticular lesions (right). 229

Fig.12.9

Juvenile L.vannamei showing signsofwhitespotdisease:distinctive whitespots,especiallyonthecarapace androstrum (left and bottomright) or pink (lightgray inprintversion)to red-brown (darkgray inprintversion) discoloration (topright) 229

Fig.12.10 P.monodon showingsignsofyellow headdisease(YHD): Yellow (lightgray inprintversion)to yellow-brown (dark gray inprintversion)discolorationof thecephalothoraxandgillregion. Threeshrimpwith (left) andwithout (right) YHD. 230

Fig.12.11 P.monodon(left) and L.stylirostris(right) withsignsofvibriosis.Septic hepatopancreaticnecrosiscausedby Vibrio(left).Shrimponfarrightis normal,otherthreehavepalered discoloration(especiallylegs),and atrophied,pale-whitehepatopancreas. Bacterialshelldiseasecausedby Vibrio indicatedbymelanizedlesions (right). 231

Fig.12.12 Shrimpmortalitiesfollowing EMSoutbreakinMexicoin2012. 232

Fig.12.13 Subadult Farfantepenaeuscaliforniensis (left)and Litopenaeusvannamei (right) showingsignsof Fusarium disease: black,melanizedlesionsonthegills (left)andprominentprotrudinglesion (right). 232

Fig.12.14 L.vannamei postlarvawithtrophozoites ofthegregarine Paraophioidina scolecoides inthemidgut. 233

Fig.12.15 Litopenaeussetiferus (left)andjuvenile L.vannamei (right)withsignsofcotton shrimpdisease.Normalshrimp (bottomleft)comparedto“cottony” striatedmusclesandblue-black cuticleofshrimpinfectedwith Ameson sp. 233

Fig.12.16 Scavengerssuchasraccoonsandother pestsmustbeexcludedfromculture andfeedstorageareastoprevent predationonshrimpanddisease introduction. 235

Fig.12.17 Moltsanddeadshrimpremovedfrom aculturetankduringa Vibrio outbreak. 237

Fig.13.1 Ten-yearannualnetcashflow. 264

Fig.13.2 Greenhousestructuretocover eight500-m2 (fourperside) racewayunitssharingacentralharvest area. 266

Fig.13.3 Marketingnetworkwithflowsof informationonproductdemand, price/availability,productsupply, andtransactions. 281

Fig.13.4 Exampledistributionchannels forshrimp. 281

Fig.13.5 HistoricalGulfofMexicoBrown Shrimp(shell-onheadless)pricesat firstpointofsale,1998–2014. 282

Fig.13.6 Farm-raisedPacificWhiteShrimp prices,CentralandSouthAmerica (head-on)atfirstpointofsale, 1998–2014. 282

Fig.14.1 (A)Acommonswimmingpool pressurizedsandfilterwithmanual backwash,(B)anautomatedbeadfilter, and(C)alargefoamfractionatorused tocontrolparticulatematterinthree separateracewaysinthe2003nursery trial. 289

Fig.14.2 WeeklychangesinTAN,NO2-N, NO3-N,andTSSintrialswiththree differentparticlecontrolmethods. 289

Fig.14.3 (A)Heavyfoamdevelopedinthe racewaywiththepressurizedsand filter,(B)apersistentalgalbloom developedintheracewaywithafoam fractionatorduringthe2003nursery trial,(C)Imhoffcones,showing (leftto right) watercolorationintheraceways operatedwithbeadfilter,sandfilter, andfoamfractionator. 290

Fig.14.4 Homemadefoamfractionators(F)with adesignatedpump(P),Venturiinjector (V),polyethylenefoam-diverting sleeve(S),andfoamcollectiontank(C). 291

Fig.14.5 Weeklychangesinammonia(A), nitrite(B),nitrate(C),dailychangesin nitrite(D),andweeklychangesinTSS (E).Alldatafroma62-dnurserytrialin 2009withPacificWhiteShrimp

PL10–12infour40m3 racewaysat5000 PL/m3 fed30%and40%crudeprotein (CP)feeds.

Fig.14.6 DailyNO2-Nina52-dnursery trial(2010)withPacificWhite Shrimpat3500PL11/m3 infour40m3 racewaysandnowaterexchange.

Fig.14.7 WeeklychangesinTAN,NO2-N,TSS, andSSina49-dnurserytrial(2012)in six40m3 racewayswithPacificWhite shrimpat1000PL9/m3 andno exchange.

Fig.14.8 ChangesinTANandNO2-Nina62-d nurserytrial(2014)withthePacific WhiteShrimpPL5–10(0.9 0.6mg)at 540/m3 intwo100m3 racewayswithno exchange.

Fig.14.9 AphotooftheblackHDPE-extruded nettingaroundtheperimeterofa40m3 racewayusedin2006ina94-dgrow-out trialwithPacificWhiteShrimpjuveniles (0.76 0.08g)at279/m3

294

295

298

300

303

Fig.14.10 PacificWhiteShrimpshowing tailnecrosis(A)andtaildeformities(B). 309

Fig.14.11 Yellow&green Vibrio countsina38-d grow-outtrial(2014)in100m3 racewayswithhybrid(FastGrowth Taura-Resistant)juveniles (6.4g)at458/m3 324

Fig.AI.1 Imhoffconeswithbacterial floc. 354

Fig.AI.2 Refractometer(A)andscale visiblewhenlookingthroughthe refractometereyepiece(B),with specificgravityontheleftandsalinity (ppt)ontheright. 356

Fig.AII.1 TCBSagarplateswith Vibrio colonies. (A) Yellow (lightgrayinprintversion) dominant[onlyone green (darkgrayin printversion)],(B)Higherproportion ofgreencolonies. 360

Fig.AII.2 ACHROMagar Vibrio agar (CHROMagar-France)withmauve (V.parahaemolyticus), green-blue (light grayinprintversion)to turquoise-blue (darkgrayinprintversion) (V.vulnificus/V.cholerae),and white(colorless)(V.alginolyticus) colonies. 361

Fig.AIII.1 Injectionpointsforfixationofwhole shrimp. 364

Fig.AIII.2 Incisionlocationsforfixationofwhole shrimp. 364

Fig.AV.1 LayoutoftheBasicWQMap. 374

Fig.AV.2 TheWQMap’sdatainputpanelsfor theexampleprobleminthetext. 376

Fig.AV.3 TheWQMapfortheexampleproblem withinitialandtargetpointsplusthe bicarbonatevector. 377

Fig.AV.4 AdjustmentOptionsmenu withsodiumbicarbonateselected. 377

Fig.AV.5 Water-qualitypointsinthe yellowadjustmentzonecanbereached byaddingNa-bicarbonateand Na-hydroxide. 378

Fig.AV.6 Adding1.13kgofNa-bicarbonateand 0.26kgofNa-hydroxidesolvesthe exampleproblem. 378

Fig.AV.7 Adding0.58kgofNa-bicarbonateand 0.70kgofNa-carbonatealsosolvesthe exampleproblem. 379

Fig.AV.8 NoamountofNa-carbonateand Na-hydroxidecanreachthetargetof theexample. 380

Fig.AV.9 WQMapdecoratedwiththe GreenZone(safearea)plusUIA&CO2 dangerzones. 380

Fig.AV.10 Settingcriticalvaluesofun-ionized ammoniaanddissolvedcarbon dioxide. 381

Fig.AV.11 Predictedwaterquality61/2hafter feeding120kgofshrimpat1.5%/day (blackcircle). 382

Fig.AV.12 Acaseinwhichadding NaHCO3 increasespH. 383

Fig.AV.13 Acaseinwhichadding NaHCO3 decreasespH. 384

Fig.AV.14 Acaseinwhichadding NaHCO3 doesnotchangepH. 384

Fig.AV.15 AddingCO2 lowerspH withoutchangingTotal Alkalinity. 386

Fig.AV.16 RemovingCO2 raisespH withoutchangingTotal Alkalinity. 386

Listoftables

Table1.1 ProductionPerformanceof ArcaBiruFarmin2010 5

Table1.2 AmountofWatertoProduce 1-kgShrimp 7

Table1.3 Grow-OutTrialComparison 12

Table2.1 CalculationsofDailyEnergyand ProteinRequirementsforPacific WhiteShrimp 22

Table2.2 RecommendedDietaryVitamin andMineralRequirementsfor Shrimp 23

Table2.3 SummaryofProgressinthe GeneticImprovementofPacific WhiteShrimpbyShrimp ImprovementSystems(SIS) 25

Table4.1 GeneralCharacteristicsof WaterSourcesforShrimp Culture(Chien,1992;Davis etal.,2004;Prangnelland Fotedar,2006) 40

Table4.2 IonicCompositionofSeawater ComparedtoaSeaSaltMixand TwoInlandSalineWaters 40

Table4.3 Consequencesof Chemoautotrophic,Heterotrophic Bacterial,andAlgalMetabolism for1gofAmmonia-Nitrogen (Ebelingetal.,2006;Lefflerand Brunson,2014) 46

Table4.4 TheMainCharacteristicsof HeterotrophicandAutotrophic Systems 47

Table4.5 Consequencesof Chemoautotrophicand HeterotrophicBacterial MetabolisminaMixotrophicSystem With1kgof35%ProteinFeed,No SupplementalOrganicCarbon, and50.4gNH4+-N(Ebelinget al.,2006)

Table4.6 OxygenSolubilityat AtmosphericPressure(101.3kPa)

Table4.7 TheInfluenceofpHDirectlyon Shrimp

Table4.8 PercentageofTotalAmmoniain theMoreToxicUn-Ionized AmmoniaFormin32–40ppt SalinitySeawateratDifferent TemperaturesandpH 51

Table4.9 MaximumConcentrationsof HeavyMetals,Pesticides, andPCBsPermittedbythe FDAinFarmedShrimp (AquacultureCertification Council,2009;Drazba,2004;FDA,2011) 56

Table5.1 SiteSelectionFactorsforan IndoorShrimpProduction Facility 60

Table5.2 ThermalResistance(R)ofCommon Materials(Fowleretal.,2002; InspectAPedia,2015) 66

Table5.3 CharacteristicsofThree LinersCommonlyUsedbyin Aquaculture 71

Table5.4 Characteristicsof Blower-Driven,Pump-Driven, andCombinedMethodsfor IndoorBiofloc 76

Table5.5 WaterDepthtoWhichAirCan BePumpedatDifferentAir Pressures 76

Table5.6 GeneralCharacteristicsof DifferentDiffusers 79

Table5.7 ComparisonofPureOxygen Sources 82

Table5.8 ComparisonofEquipmentfor SolidsControlinIndoorBiofloc Systems 85

Table5.9 RecommendedEquipmentfor IndoorSuper-IntensiveBiofloc ShrimpProduction 93

Table6.1 CleaningandDisinfection Protocol(Yanongand Erlacher-Reid,2012) 121

Table6.2 RecommendedConcentrations andExposureTimesforChlorine Disinfection(HugueninandColt, 2002;Lawson,1995) 123

Table6.3 ProductstoIncreasethe ConcentrationofMajorCations inCultureWater 127

Table7.1 CommonReagentsUsedto IncreaseAlkalinityandTheir Characteristics 136

Table7.2 OrganicCarbonSourcesfor BioflocSystems 140

Table7.3 CalculationofCarbonAddition (asWhiteSugar)toRemovea DesiredProportionof AmmoniaFromaGivenAmount ofFeed 141

Table7.4 RecommendedConcentrationsof SelectedTraceElementsinWater forShrimpCultureWithina SalinityRangeof5to35ppt (Whetstoneetal.,2002) 143

Table7.5 OptimalRangesofWater-Quality ParametersforPacificWhite ShrimpinBioflocSystems,Frequency ofAnalysis,andAdjustment Methods 145

Table8.1 AcclimationofPacificWhite Shrimp(PL10andOlder)Basedon DifferencesinpH,Salinity (10–40ppt),andTemperature(°C) 159

Table8.2 PacificWhiteShrimpPL TolerancetoFormalinand LowSalinitybyAge 163

Table8.3 RecommendedExposure ConcentrationandExpected SurvivalforFormalinStressTestof PL1toPL5PacificWhiteShrimp (n ¼ 100) 163

Table8.4 RecommendedExposure ConcentrationandExpected SurvivalforLowSalinityStress TestofPL1toPL5PacificWhite Shrimp(n ¼ 100) 164

Table8.5 RecommendedDecreaseand ExpectedSurvivalforLow SalinityStressTestofPL1 toPL5PacificWhiteShrimp(n ¼ 100) 164

Table8.6 PacificWhiteShrimpPLStress Tests 164

Table8.7 SummaryofPLQuality Assessment 165

Table8.8 SummaryofObservationsof PostlarvaeandRecommended Responses 165

Table8.9 RoutineNurseryActivities 173

Table8.10 DataSheetRecordingSamples toCalculateTotalYieldFroma HypotheticalNursery 177

Table9.1 FeedTableBasedonMaximum IngestionAccordingtoBody Weight(Nunes,2011) 189

Table9.2 ExampleofDataCollectedFrom aGrow-OutTank 194

Table9.3 RoutineTasksAssociated WithManagingGrow-OutRaceways 196

Table9.4 Grow-OutRoutine 198

Table12.1 ShrimpHealthSummary 224

Table13.1 TemplateforCalculating Staffing,Salary,andWages foraShrimpProduction Facility 246

Table13.2 TemplateforDetermining ElectricalCostsforTypical MachineryItemsUsedina GreenhouseShrimpProduction Facility 247

Table13.3 Bio-EconomicModelUser InputSpreadsheets,Biological ParameterstoEnter 249

Table13.4 Bio-EconomicModelUserInput Spreadsheets,Racewayand GreenhousePhysicalFacility ParameterstoEnter 249

Table13.5 Bio-EconomicModelUser InputSpreadsheets,InputUnit Cost-PriceParameterstoEnter 250

Table13.6 Bio-EconomicModelUserInput Spreadsheets,Capital InvestmentCosts 251

Table13.7 InvestmentItemInformation RequiredfortheBio-Economic Model 252

Table13.8 CalculationofInitialInvestmentand AnnualReplacementCosts 254

Table13.9 Intermediate-andLong-Term LoanPaymentsofAnnual InterestandPrincipal 257

Table13.10 EnterpriseBudget(Receipts, VariableCosts,FixedCosts,Net ReturnstoLand)andBreakeven PricesforaSuper-Intensive ShrimpProductionSystem ConsistingofTenGreenhouses (EightGrow-OutRacewaysper GreenhouseandTwoNursery RacewaysperGreenhouse) BasedonAverageof10-yr CashFlow 258

Table13.11 ExampleofaOne-YearCash FlowGeneratedasanOutput FromCashFlow,Year1,fora RecirculatingBiosecureShrimp ProductionFacility 260

Table13.12 Bio-EconomicModelOutput 263

Table13.13 ThreeBuildingStructureOptionsto EncloseRacewayUnits 267

Table13.14 EstimatedRacewayConstruction CostsforTwoWallTypesandSlabor SandBottoms,andAs-BuiltRaceway Cost 268

Table13.15 RacewayEconomiesofScale WithPostandLiner Construction 269

Table13.16 FixedCostsforConstructions andEquipment/Machineryforthe TexasA&M-ARMLIndoor RecirculatingShrimp ProductionFacility,Six40m3 Raceways,2014 271

Table13.17 FixedCostsforConstructions andEquipment/Machineryforthe TexasA&M-ARMLIndoor RecirculatingShrimp ProductionFacility,Two100m3 Raceways,2014 273

Table13.18 BaseScenarioConditionsUsed inBio-EconomicModelRun 275

Table13.19 ChangeinNetPresentValue(NPV), InternalRateofReturn(IRR),and CostofProduction(COP)With20% ImprovementinCriticalProduction Factors 276

Table13.20 2013StudyResultsComparing Hyper-Intensive35%Protein Feed(HI-35)toa40%Protein ExperimentalFeed(EXP-40) 276

Table13.21 Summaryof2013ProductionResults ExtrapolatedtoaGreenhouseWith Eight500-m3 Grow-OutRaceways andTwo500-m3 Nursery RacewaysandTwoShrimp SellingPrices 277

Table13.22 SummaryofEconomicAnalysis forthe2013TrialsExtrapolated toaGreenhouseWithEight500-m3 Grow-OutRacewaysand Two500-m3 NurseryRaceways atTwoShrimpSellingPrices 277

Table13.23 Summaryof2014NurseryStudy ComparingProductionof ShrimpGrowninTwoDifferent Greenhouse/Raceway Configurations 278

Table13.24 Summaryof2014NurseryStudyCost ofShrimpProductionRaisedinTwo DifferentGreenhouse/Raceway Configurations 278

Table13.25 Summaryof2014Grow-OutStudy ComparingProductionofShrimp GrowninTwoDifferent Greenhouse/Raceway ConfigurationsandFedTwoDietsin theGreenhouseWithSixRaceways 279

Table13.26 Summaryof2014Grow-Out StudyCostofShrimp ProductionGrowninTwoDifferent Greenhouse/Raceway ConfigurationsandFedTwoDietsin theGreenhouseHaving SixRaceways 279

Table13.27 Historical Ex-Vessel Price($/lb) forHeads-onShrimpFromthe NorthernGulfofMexico 283

Table13.28 TheEffectofShrimpSizeon ProductionandEconomicMeasures 284

Table14.1 Summaryof40m3 Nursery Trials(1998and1999)With PacificWhiteShrimpPostlarvae atDifferentStockingDensities 288

Table14.2 Summaryof50-dNurseryTrial in2000WithPL8–10(0.8mg)Pacific WhiteShrimpat3700PL/m3 in40m3 RacewaysWithSandFilterand SupplementedPureOxygen 288

Table14.3 Summaryofa74-dNursery Trial(2003)With40m3 RacewaysWith 0.6-mgPL5–6PacificWhiteShrimp at4300,7300,and5600PL/m3 With aBeadFilter(BF),Pressurized SandFilter(PSF),andFoam Fractionator(FF) 290

Table14.4 ResultsFroma71-dNursery(2004)in 40m3 RacewaysWith0.6mgPacific WhiteShrimpPLat4000/m3 and ParticulateMatterControlledby WaterExchange(WE)of9.37%/dora CombinationofPressurizedsand FiltersandHomemadeFoam Fractionators(FF)with3.35%/d ExchangeinTwoReplicates 292

Table14.5 Summaryof62-dNurseryTrial (2009)With1-mgPacificWhite ShrimpPL10–12in40m3 Racewaysat 5000PL/m3 Offered30%and40% CrudeProtein(CP)Feeds 293

Table14.6 PerformanceofFast-Growthand Taura-ResistantPacificWhiteShrimp PLina52-dNursery(2010)inFour 40m3 Racewaysat3500PL11/m3 andNoWaterExchangeina Two-ReplicateTrial 295

Table14.7 PerformanceofFast-Growth andTaura-ResistantPacific WhiteShrimpPL9(2.5mg)ina49-d NurseryTrial(2012)in40m3 Racewaysat1000PL/m3 and NoExchange 296

Table14.8 WaterQualityina49-dNurseryTrial (2012)in40m3 RacewaysWithPacific WhiteShrimpat1000PL9/m3 andNo Exchange 297

Table14.9 Summaryof62-dNurseryTrial (2014)WithPacificWhiteShrimp PL5–10(0.9 0.6mg)at675PL/m3 in 40m3 RacewaysFedEZ Artemia and DryFeedinBiofloc-Dominated WaterWithNoExchange 299

Table14.10 Summaryofa62-dNursery Trial(2014)WithPacificWhite ShrimpPL5–10(0.9 0.6mg)at 540PL/m3 in100m3 Raceways fedEZ Artemia andDryFeedin Biofloc-DominatedWaterWith NoExchange 301

Table14.11 NurseryTrialsinRacewaysat theTexasA&MAgriLife ResearchMariculture Laboratory(1998–2014) 302

Table14.12 PerformanceofPacificWhiteShrimp Juveniles(0.76 0.08g)Stockedat 279/m3 ina94-dGrow-OutTrial (2006)inSix40m3 Raceways OperatedinDuplicatesWithThree Treatments:NoFoamFractionator andLimitedWaterExchange (No-FF),FoamFractionatorWith LimitedWaterExchange(FF),andNo FoamFractionatorWithIncreased WaterExchange(WE)WhenFed35% ProteinFeed 304

Table14.13 Summaryofa92-dGrow-Out Trial(2007)infour40m3 Raceways WithPacificWhiteShrimpJuveniles (1.3 0.2g)at531/m3 Feda35% CrudeProteinFeedandNoWater Exchange 305

Table14.14 PacificWhiteShrimp Performanceina108-dGrow-Out Trial(2009)inFour40m3 Raceways with1.0gJuvenilesat450/m3 EachOperatedWithaFoam Fractionator(FF)orSettlingTank(ST) forTSSControlWithTwoReplicate perTreatment 307

Table14.15 Summaryofthe2011Grow-OutTrial WithPacificWhiteShrimpJuveniles inFive40m3 Racewaysat500/m3 WithNoWaterExchangeandFeda 35%ProteinFeed 310

Table14.16 WaterQualityinthe2012Grow-Out TrialWithPacificWhiteShrimp Juvenilesin40m3 Racewaysat 500/m3 WithNoWaterExchange and35%ProteinFeed 312

Table14.17 PacificWhiteShrimpPerformancein a67-dGrow-OutTrial(2012)With 2.7gJuvenilesinSix40m3 Raceways at500/m3 FedTwoCommercial Feeds,NoWaterExchange,With FoamFractionators(FF)andSettling Tanks(ST)toControlBiofloc 313

Table14.18 WaterQualityina77-d Grow-OutTrial(2013)WithPacific WhiteShrimpJuvenilesinSix40m3 Racewaysat324/m3 FedCommercial (HI-35)andExperimental(EXP-40) FeedWithNoWaterExchange 314

Table14.19 PacificWhiteShrimpPerformancein a77-dGrow-OutTrial(2013)inSix 40m3 Racewaysat324/m3 Fed Commercial(HI-35)and Experimental(EXP-40)FeedWithNo WaterExchange 314

Table14.20 WaterQualityina49-d Grow-OutTrial(2014)With PacificWhiteShrimpJuvenilesin Four40m3 RacewaysFedTwo CommercialFeedsWithNo WaterExchange 315

Table14.21 Mean Vibrio ColonyCountsonTCBS overa49-dGrow-OutTrial(2014)in Four40m3 RacewaysFed35%and 40%ProteinFeeds(HI-35and EXP-40) 316

Table14.22 PacificWhiteShrimpPerformancein a49-dGrow-OutTrial(2014)infour 40m3 Racewaysfed35%and40% CrudeProteinFeedsWithNoWater Exchange 317

Table14.23 Grow-OutTrialsin40m3 RacewaysattheTexasA&M-ARML (2006–2014) 318

Table14.24 Summaryof87-dGrow-Out Trial(2010)inTwo100m3 Raceways WithPacificWhiteShrimpJuveniles (8.5g)at270/m3 WithNoWater Exchange 319

Table14.25 WaterQualityina106-d Grow-OutTrial(2011)in100m3 RacewaysStockedWith3.1gJuvenile PacificWhiteShrimpat390/m3,a3 Injectors,HI-35Feed,andNoExchange 321

Table14.26 Summaryofa106-dGrow-OutTrial (2011)inTwo100m3 Raceways StockedWith3.1gJuvenilePacific WhiteShrimpat390/m3,a3 Injectors, HI-35Feed,andNoExchange 321

Table14.27 Summaryofa63-dTrial(2012)intwo 100m3 RacewaysWith3.6-gPacific WhiteShrimpJuvenilesat500/m3,a3 Injectors,HI-35Feed,andNo Exchange 322

Table14.28 WaterQualityina38-dGrow-Out Trial(2014)inTwo100m3 RacewaysWith6.4-gHybrid (Fast-Growth Taura-Resistant) PacificWhiteShrimpJuveniles at458/m3 324

Table14.29 Vibrio Countsina38-dTrial(2014)in two100m3 RacewaysWithHybrid (Fast-Growth Taura-Resistant) Juveniles(6.4g)at458/m3 325

Table14.30 Summaryofa38-dGrow-Out Trial(2014)inTwo100m3 Raceways WithPacificWhiteShrimp(6.4g)at 458/m3,a3 Injectors,EXP-40Feed, andNoExchange 325

Table14.31 SummarizestheGrow-OutTrialsin Two100m3 RacewaysattheTexas A&M-ARML(2010–2014) 326

TableAI.1 PercentageofToxic(Unionized) Ammoniainthe23–27ppt SalinityRangeatDifferent TemperaturesandpH 351

TableAI.2 PercentageofToxic(Unionized) Ammoniainthe18–22ppt SalinityRangeatDifferent TemperaturesandpH 351

TableAI.3 PercentageofToxic(Unionized) AmmoniainFreshwater (TDS ¼ 0mg/L)atDifferent TemperaturesandpH 352

TableAII.1 ColonyColorFormedby DifferentPathogenic Vibrio spp. onTCBSAgarPlatesAccording toSucrose(Yellow)or NonsucroseFermenting(Green) (NoguerolaandBlanch,2008;Doug Ernst,personalcommunication; JeffreyTurner,TAMU-CC,personal communication) 360

TableAIV.1 RecommendedWaterQuality LaboratoryAnalyses, Equipment,andSupplies 368

TableAVI.1 UnitConversionTable 389

TableAVI.2 TemperatureConversion

Preface

Reducingaquaculture’simpactontheenvironmentisnowwidelyrecognizedbyproducers, retailers,researchers,andconsumersalikeas absolutelyessentialiftheindustryistoexpand tomeetthegrowingglobaldemandforseafood.

Consumershavebeenprominentindriving thistrendbydemandingthattheirseafoodpurchasessatisfycertainsustainabilitycriteria. Theirconcernsrelatetopracticesthatnotonly ensureahealthyproduct,butalsoreduceaquaculture’senvironmentalfootprint.Innoparticularorder,theseconcernsinclude:

• Dischargeofuntreatedwastewaterand pathogensintotheenvironment

• Feedingredientsderivedfromstressed fisherystocks

• Antibioticsandartificialcoloringagentsused inproduction

• Inefficientuseofdiminishingfreshwater resources

• Escapeofculturedstockintowild populations

• Preferenceforlocallyraised,ultra-fresh products

• Farm-to-forktraceability

Fulfillingmanyofthesecriteriainevitably requiresashiftfromtraditionalflow-through systemstorecirculatingaquaculturesystem (RAS)technologies.Commercialadoptionof RAS,however,isproceedingveryslowly.Two reasonsforthisareasfollows:

• Itismoreprofitableto“externalize”thecost ofwatertreatmentbydischargingwaste directlyintotheenvironment.

• RASmanagementrequiresgreatertechnical expertise.

Responsibleenvironmentallegislationand consumerpreferenceforsustainablyproduced seafoodbothencouragegrowersto“internalize” watertreatment,theformerbyregulatory enforcementandthelatteractingthroughmarketforces.

Thetechnicalhurdletoexpansionislowered byprovidingthetoolsandtrainingneeded formodernRASdesignandmanagement. Thisis,infact,thecoremotivationbehind thepresentmanualthatdescribesthebioflocdominated(BFD)systemdevelopedby Dr.TzachiSamochaattheTexasA&MAgriLife ResearchMaricultureLaboratory(ARML)in CorpusChristi,Texas.

Dr.Samocha’ssystem,theproductofover 16yearsofresearch,hasreachedapointat whichitisreadyfordisseminationbeyondthe aquacultureresearchcommunity.Partsofit havebeenreportedinthescientificliterature andsomecomponentshavebeenimplemented commercially(FloridaOrganicAquaculture,Fellsmere,FL,US;AmericanMariculture,St.James City,FL,US;BowersShrimp,Palacios,TX,US;severalsmall-scaleproductionoperationsthroughoutthe US;LAQUA,Palotina,Parana,Brazil,andanumberofshrimpfarmersinSouthKorea),butthismanualisthefirstcompletedescriptionmade availableforawideaudienceofaquaculture stakeholders.

AmongRAStechnologies,Dr.Samocha’s BFDsystemstandsoutbyregularlyyielding 7–9kg/m3 ofhigh-quality,marketableshrimp

afterabouttwomonthsofgrow-out.Thisis roughlytentimestheyieldoftraditionalflowthroughsystems,withwhichwell-runBFDsystemsarecostcompetitive.Further,thisis achievedwitheffectivelyzerowaterexchange, animportantfeaturethatenhancesthissystem’s claimofenvironmentalsustainability.

TexasA&Mhasarecordofproducingpracticalaquaculturemanualsbasedondecadesof researchbyitsstaff,students,andcollaborators. Thesemanuals(e.g., TreeceandYates,1988, 2000;TreeceandFox,1993)havehadarecognizedimpactinadvancingcommercialaquacultureinTexasandbeyond.

Thepresentworkaspirestocontinuethattraditionbutdivergesinthatitisnotstrictlya ‘How-To’manual.Whileitdoescontaindetailed instructionsforcarryingoutproceduresessentialtoBFDproductionofPacificWhiteShrimp, italsoprovidesathoroughaccountnotonlyof whatworkedbut—importantly—whatdid not work.Thisgivesreadersdeeperinsightinto theprocessthatresultedinthemostrecent BFDsystemandalsoalertsthemtocertainpitfallstobeavoided.

Muchofthematerialinthemanualthusdoes notfitthecontentandstylerequiredbytypical scientificjournalsandsohasnotpreviously appearedinprint.Thetextalsoispurposely writteninamorenarrativestyleintendedto makeitmoreaccessibletoawideraudience. Theintentistohelpaspiringentrepreneurs buildandoperateascaleversionofDr.Samocha’sBFDsystemtogethands-onexperience undertheconditionsoftheirsite.Suchexperiencewillinformtheirdecisionofhow—or whether—toincorporateBFDtechnologyin

theirbusinessplans.Theeconomicanalysesof Chapter13willproveparticularlyusefulin thisregard.

Alongwithasetofhelpfulappendices,the manualalsotouchesonmoregeneralaspects ofclosedsystems,suchasequipmentand procedureoptions,thatmaybeunfamiliarto thosewithoutexperiencewiththistypeof aquaculture.

Finally,itisthehopeoftheauthorandhis contributorsthatthismanualwillproveuseful instimulatingadoptionofthisinnovative shrimpproductiontechnologyand,insome way,contributetosustainableexpansionofthe USshrimpaquaculturesector.

Descriptionsofprocedures,equipment,andmaterialsusedinthisworksometimesgivethenameof manufacturers.Mentioningsuppliernamesdoes not,however,implyendorsementbytheauthors, TexasA&MAgriLifeResearch,ortheTexasSea GrantProgram

NickStaresinic

References

Treece,G.D.,Fox,J.M.(Eds.),1993.Design,Operationand TrainingManualforanIntensiveCultureShrimp Hatchery. https://eos.ucs.uri.edu/seagrant_Linked_ Documents/tamu/noaa_12406_DS1.pdf.(Accessed25 May2019).

Treece,G.D.,Yates,M.E.(Eds.),1988.Laboratorymanual forthecultureofPenaeidshrimplarvae.TexasA&M UniversitySeaGrantCollegeProgram,TAMU-SG-88-202. Treece,G.D.,Yates,M.E.(Eds.),2000.Laboratorymanualfor thecultureofPenaeidshrimplarvae.TexasA&MUniversitySeaGrantCollegeProgram,TAMU-SG-88-202(R). Reprinted.

Acknowledgments

Thispublicationwassupportedinpart byanInstitutionalGrant(NA14AR4170102: “Seed-to-HarvestOperationsManual&TrainingProgramforIndoorBioFloc-Dominated Productionof Litopenaeusvannamei,thePacific WhiteShrimp”)totheTexasSeaGrantCollege ProgramfromtheNationalSeaGrantOffice, NationalOceanicandAtmosphericAdministration,U.S.DepartmentofCommerce.

Wewishtoacknowledgethecontributions andsupportofthefollowingpeopleand organizations:

Mr.CliffMorris,President&Founder,FloridaOrganicAquaculture,Fellsmere,Florida forprovidingmatchingfundsfortheabovementionedSeaGrantfunding.Wealsogreatly appreciatehisinitiativeandeffortsinhelping tobringthismanualtoitssuccessfulcompletion atacriticaljuncture.

Dr.PamelaPlotkin,Director,TexasSeaGrant CollegeProgram,CollegeStation,Texasforher monumentaleffortstoensurethecompletionof thismanual.

TexasA&MAgriLifeResearchforproviding thefacilityandfundingleadingtothegenerationoftheinformationsummarizedinthis manual.

ZeiglerBros.Inc.,Gardners,Pennsylvania andYSIInc.,YellowSpring,Ohioforverygenerouslyprovidingthetimelyfinancialsupport forprofessionallyrenderedpagelayout.

Mr.RodSantaAna,journalist,TexasA&M AgriLifeCommunications,Weslaco,Texasfor hiscontributiontoourshrimpresearchprogramandhisverywelcomehelpinproviding professionalpagelayoutservicesforanearlier version.

Mr.BobRosenberry,owner,Shrimp NewsInternational,forhismanyconstructive suggestionsandfordistributingapreviewofthis manualtohis9000-plusworldwidesubscribers.

Dr.DominickMendola,SeniorDevelopment Engineer,ScrippsInstitutionofOceanography, UniversityofCaliforniaSanDiego,SanDiego, Californiaforhisgreatinitiativeataparticularly criticaljunctureinthisproject.

Dr.DaleHunt,RegisteredPatentAttorney, SanDiego,Californiaforhisveryquickand indispensablehelpinaddressinguseoftheterm “mixotrophic”inthismanual.

Dr.SandraShumway,DepartmentofMarine Sciences,UniversityofConnecticut,Groton, Connecticutforhermonumentalinitiativein gettingthismanualbackincirculation.

Ms.PatriciaOsborn,Sr.AcquisitionsEditor andMs.LauraOkidi,EditorialProjectManager, atElsevierScience,ElsevierBookDivision,for theirprofessionalismandgeneroushelpinpublishingthismanual.

TheElsevierBookDivisionforundertaking thepublicationofthismanualandsupporting developmentoftheaquacultureindustryover manyyears.

TheU.S.MarineShrimpFarmingProgram, GulfCoastResearchConsortium,USDA, NationalInstituteofFoodandAgriculturefor partialfundingtodevelopsustainableand biosecureshrimpproductionmanagementpracticesforthePacificWhiteShrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei.

REVIEWERS

Wewouldliketoacknowledgethefollowing peoplewhohavecontributedtoimprovingthe contentandthequalityofthismanualbytheir criticalreadingandconstructivesuggestions:

Dr.JohnLeffler,formerDirector,Marine ResourcesResearchInstitute(MRRI),South CarolinaDepartmentofNaturalResources (SCDNR),SouthCarolina

Dr.RobertStickney,formerDirector,Texas SeaGrantCollegeProgram,College Station,Texas

Dr.JohnHargreaves,Aquaculture AssessmentsLLC,SanAntonio,Texas

Mr.WilliamBray,formerSeniorResearch AssociatewiththeTexasAgricultural ExperimentStationtheShrimpMariculture LabatPortAransas,Texas

Dr.TomZeigler,Chairman,ZeiglerBros.Inc. (ZBI),Gardners,Pennsylvaniaforhisvery usefulcommentsoniterationsofthemanual outline

Dr.DallasWeaver,Owner&President, ScientificHatcheries,HuntingtonBeach, Californiaforgenerouslytakingthetimeto providehisinsightfulreviewofAppendixV

CONTRIBUTORS

Dr.SusanLaramore,AssistantResearch ProfessorandHeadAquaticAnimalHealth Laboratory,HarborBranchOceanographic Institute,FloridaAtlanticUniversity,Florida, forhercontributiontoChapter12.

Dr.TomZeigler,Chairman,ZBI,Gardners, Pennsylvania,forhiscontributionto Chapter8and9.

Dr.CraigBrowdy,DirectorofResearch& DevelopmentZBI,forhisconstructiveadvice infinalizingthemanual.

Ms.CherylShew,GlobalShrimpSales Specialist,ZBI,forhercontributionto Chapters8and9.

Mr.LeeSchweikert,mydevotedand exceptionallytalentedformeremployeeof15 years,forhiscontributiontoChapter5.

Dr.PaulFrelierDVM,AquaticDisease Specialist,ThreeForks,Montana,forhis contributiontoChapter12.

Specialthanksareowedtothemany researchers,formerstudents,employees,and individualswhoworkedinourlaborcollaboratedwithusduringthelasttwoandahalf decades.Inparticularwewouldliketomention thefollowingpeople:

Mr.TimMorris,GeneralManager,American Mariculture,Inc.,St.JamesCity,FL,forhis usefulcommentsduringthepreparationof thismanual.Alsospecialthanksforhishard work,devotion,andhisoutstandingresearch supportovereightyearsofworkinmylab.

Dr.MehdiAli,AnalyticalChemistry LaboratoryManager,TheUniversityof NewMexico,Albuquerque,NewMexico, inappreciationofhisexpertiseandthe pleasureofworkingtogetherfor morethanadecadeandahalfondifferent aspectsofwaterqualityinshrimp culturesystems.

Dr.EudesCorreia,DistinguishProfessor, FederalRuralUniversityofPernambuco, DepartmentofFisheriesandAquaculture, Recife,Brazilforthequalityofhisresearch duringhissabbaticalinmyresearchfacility.

Dr.AndreBraga,Professor,Universidad Auto ´ nomadeBajaCalifornia,Instituteof OceanographicInvestigations,Ensenada, Mexico,Dr.DarianoKrummenauer, ResearchProfessor,MaricultureLab,Federal UniversityofRioGrande,Oceanography Institute,RioGrande,Brazil,andDr.Rodrigo Schveitzer,FederalUniversityofSaoPaulo, Professor,DepartmentofMarineSciences, Sa ˜ oPaulo,Brazilfortheirdedication,hard work,andthesignificantresearchresultsthey producedduringtheirprofessionaltraining atthefacility.

Mr.BobAdvent,owner,a3 All-Aqua Aeration,FarmingtonHills,Michiganforour jointresearchonhisa3 injectorsinbiofloc shrimpproductionsystemsandfordonating theinjectorsusedinthetwo100m3 raceway system.

Dr.AllenDavis,AlumniProfessor& Nutritionist,AuburnUniversity,Auburn, Alabamaformorethantwodecadesof workingtogetheronmanyresearchand commercialprojectsrelatedtoshrimp nutritionandsuper-intensiveproduction systemsofnativeandexoticshrimpspecies withnowaterexchange.

Mr.JoshWilkenfeld,formerAssistant ResearchScientist,TexasA&MAgriLife ResearchMaricultureLabatFlourBluff, CorpusChristi,Texasforourmanyyearsof workingtogetherandhistireless contributionstothedevelopmentofbioflocdominatedproductionpracticesfornative andexoticshrimp.

Dr.RyanGandy,ResearchScientist,Fishand WildlifeResearchInstitute,St.Petersburg, Floridaforthemanyproductiveyearsof researchwithnativeandexoticshrimpatthe facility.

MyVerySpecialthanksarereservedformy wifeRuthieandmychildrenforputtingupwith myworkaholicnature.Iloveyouall.

Theauthorsofthismanualaresolelyresponsiblefortheaccuracyofthestatementsandinterpretationscontainedherein.Thesedonotnecessarily reflecttheviewsofthereviewers,NationalSea Grant,TexasSeaGrant,TexasAgriLifeResearch, TexasA&MUniversitySystemortheElsevierBook Division.

Allphotospresentedwithoutcreditwere takenbyformerTexasA&MAgriLifeResearch staffmembers.

1 Introduction

1.1DEVELOPMENTOFBIOFLOC TECHNOLOGYFORSHRIMP PRODUCTION

Inthe1980s,mostshrimpfarmsaroundthe worldweremanagedasextensiveorsemiintensivepondswithlowpostlarvae(PL)stocking densities(2–5PL/m2),lowyields(0.05–0.1kg/ m2),andhighdailywaterexchangeofupto 100%(buttypically10%–15%).Whenevera waterqualityproblemarose—suchashigh levelsofammonia,lowdissolvedoxygen,dense algaeblooms,oroutbreaksofdiseaseorparasiticorganisms—itsimplywasflushedaway byreplacingalargefractionofpoor-quality waterwithfreshlypumped“clean”water.This practiceexportswaterqualityproblemstothe localenvironment,compromisingthehealthof thesurroundingaquaticecosystemandthe qualityofintakewaterpumpedbydownstream aquaculturefarms.Thistypeofwaterquality managementclearlyisunsustainable.

• TauraSyndromeVirus(TSV)infectedshrimp inpondsintheTauraRiverareaofEcuador andrapidlyspreadtootherpartsofthe country.

• WhiteSpotSyndromeVirus(WSSV)started inAsia,arrivedintheUnitedStatesin1995 andcontinuestocauseproblemsinMexico andmanyothercountries.

• EarlyMortalitySyndrome(EMS),alsocalled AcuteHepatopancreaticNecrosisDisease (AHPND),beganinChinain2009and subsequentlyspreadtoThailand,Vietnam, andMexico.

Thisnaturallypromptedmuchgreaterattentiontobiosecurity,whichnowbecameacentral concernofshrimpproducers.Acommon responsetocontrollingdiseaseoutbreakswas toaddasecureholdingreservoirtoisolate disease-freebroodstock.Inaddition,many farmsbegantreatingincomingwater.Inadramaticbreakwithcontemporarypractices,some establishedfarmsevenundertookamajor reconfigurationfromtraditionalflow-through towater-reusesystems.

Manyoftheseflow-throughsystemsgraduallyevolvedtowardsmallerponds(<10ha) withgreaterstockingdensities(5–20PL/m2) andgreateryields(upto0.3kg/m2).Thisinitiallyworkedverywell,butin1988 Monodon baculovirus (MBV)infectedshrimpfarmsinTaiwan.Otherviralandbacterialdiseasessoon followedandthisexactedaheavytollonthe worldwideshrimpaquacultureindustrywell intothe1990s.Someexamplesofnoteworthy diseasesinclude:

Overthissameperiod,effortsweremadeto developaviablemarineshrimpfarmingindustryintheUnitedStates.TheemergingUSindustrywasfacedwithovercominganumberof obstacles,foremostofwhichisalimitedgrowingseason.Significantlyhigherlaborcosts, higherenergycosts,lackofsuitablecoastalland, andmorestringentenvironmentalregulations thaninmanyshrimpproducingcountriesalso contributedtothecompetitivechallenge.

Withlimitedpotentialfordevelopmentof year-roundpondculture,researchfocusedon cost-effectiverecirculatingaquaculturesystems (RAS)thatoperateatmuchhigherbiomass (>5kg/m3)andwithminimalwaterexchange (<10%/day).Becausethesesystemsuseconsiderablylesslandandwaterthantraditional ponds,theypromisedenhancedsustainability, greaterbiosecurity,andaregularsupplyof ultra-fresh,high-qualityshrimptodomestic markets.

Achievingthisobjectivemotivatedadvances inanumberofrelatedareas,especiallydevelopmentofgeneticallyimprovedlinesofcommercialshrimpspeciesthataremoretolerantof elevatedstockingdensities,advancedaeration equipmentandtechniques,efficientammonia managementprocedures,andmanufactured dryfeedsspeciallyformulatedforuseinhighdensityclosedsystems.Regardinggenetically improvedshrimp,manygenerationsofselective breedingresultedintheproductionofspecific pathogenfree(SPF)stocksofPacificWhite Shrimp Litopenaeusvannamei. Thisspecieshas sincerisentobecometheprimaryspeciesculturedinpondsandclosedsystemsaroundthe world.Thesegeneticlineshavebeenakeyreasonforachievementofthemuchhigheryields inmodernaquaculturesystems.

RASmaybeclassifiedinseveralways.One thatisusefulforpresentpurposesdistinguishes betweenthosethatraisethetargetspeciesseparatelyfromthebio-treatmentprocessesand thoseinwhichthetargetspeciesisraisedin thesamewatervolumeasthebio-treatment organisms.

Thefirstincludestypical“clearwater”and IMTA(IntegratedMulti-TrophicAquaculture) systems,bothofwhichmaintainseparatecompartmentsforgrow-outandremovalofdissolvedinorganicnitrogen.Clearwatersystems useatraditionalbiofilter(Timmonsand Ebeling,2013)andIMTAusesmacroalgaeand bivalvesforessentialwater-treatmenttasks (Samochaetal.,2015).

Inthesecondcategory,thetargetspeciesis raisedtogetherwithorganismsthatremove ammoniaandrecyclewasteproducts.These maybeamixtureofphytoplanktoninso-called greenwatersystems,orflocaggregateswith theirmicrobialcommunityin“brownwater” systems.Thebioflocsystemthatisthesubject ofthismanualbelongstothelattertype.

1.2THEBEGINNINGSOFBIOFLOC

Ingeneralterms,flocculationisaphysical processbywhich,underfavorableconditions, smallparticlessuspendedinafluidcoalesceto formaggregates.Ithaslongbeenemployedin wastewatertreatmentandhasanevenlonger historyinfoodprocessing,especiallyinbeer andcheeseproduction.

Oneofthefirstreferencesinthepopularscientificliteraturetowhatnowisreferredtoas “biofloc”bytheaquaculturecommunitymight betracedtoashortpieceentitled“FoodBubbles”thatappearedintheNovember1964issue ofthe ScientificAmerican magazine.Itintroduced whatpreviouslywasanunappreciatedpathin themarinefoodweb:wave-generatedbubbles thatstimulatedformationoforganic-richaggregates.Thearticlestated:

...moleculesfromthevastsupplyoforganicchemicalsdissolvedinseawateradhereinlargenumbers tothe“airbubbles”two-dimensionalboundary layers.Theyformclumpsoforganicmaterialthat areeatenbythesmallestmembersofthemarineanimalpopulation.Itwaspointedoutthatthequantityof organicmatterintheoceansisatleast50timesgreater thanthatcontainedinalllivingplankton.