Stereochemistryand OrganicReactions

Conformation,Configuration,Stereoelectronic EffectsandAsymmetricSynthesis

DipakK.Mandal

FormerlyofPresidencyCollege/University Kolkata,India

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier 125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom

Copyright©2021ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans, electronicormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageand retrievalsystem,withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseek permission,furtherinformationaboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangements withorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,can befoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions

Thisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythe Publisher(otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperience broadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedical treatmentmaybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluating andusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuch informationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers, includingpartiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors, assumeanyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproducts liability,negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products, instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN978-0-12-824092-2

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: SusanDennis

AcquisitionsEditor: EmilyMcCloskey

EditorialProjectManager: AllisonHill

ProductionProjectManager: PaulPrasadChandramohan

CoverDesigner: VictoriaPearson

TypesetbySPiGlobal,India

Preface

Organicstereochemistryisavastandimportantsubject.Itisanintrinsicpartof allorganicchemistry.Planningandexecutingstereoselectivesynthesistopreparesingleenantiomersaswellassinglediastereomersisanexhilarating sciencethathasregisteredenormousprogressovertheyears,andstillisinfast development.Understandingofthefactorsthatdeterminethehighlevelsof three-dimensionalcontrolinorganicsynthesisisanessentialandfundamental topicforallstudentsoforganicchemistry.Itisnotsurprisingthereforethat stereochemistryiscoveredineveryundergraduate,advancedundergraduate andgraduatecourseinorganicchemistry.Itismyinvolvementinteachingthis subjecttoundergraduateandgraduatestudentsformorethan30yearsthathas inspiredmetowritethisbook.Thepurposeofthisendeavourisentirely pedagogic,keepinginviewthatourstudentsdesperatelycraveunderstanding, notfactualknowledgealone.Understandingrequiresa‘feel’forthesetof principlesthatinfluencethestereochemistryoforganicmoleculesandtheir reactions,whichisintheheartofthisbook;thehistoricaldevelopmenthasbeen generallygivenshortshrift.

Thebookisprimarilystructuredinthreeparts(PartI–III),andeachpartis factoredintoseveralchapters.AnappendixisincludedinPartIV.PartIdeals withthestereochemistry—conformationandconfiguration—ofacyclic molecules(Chapters1and2)andcyclicmolecules(Chapter3).Thestereochemistryoforganicreactionsfollowsthereafter.PartIIprovidesanintroductiontoperturbationmolecularorbitaltheoryfortheoriginofstereoelectronic effects(Chapter4)andanintroductiontotheprinciplesofstereoselectivity andhierarchicallevelsorgenerationsofasymmetricsynthesis(Chapter5)as abackgroundaidtofollowthereactionstereochemistrycoveredinPartIII. Ihopethisuniquestylewouldhelpenhancethepedagogyofthistext.Thestereochemistryofreactionswithparticularemphasisondiastereoselectivityand asymmetricsynthesisarepresentedinsevenchaptersalongthelinesofmechanisticclasses.Twoelaboratechapters(Chapters6and7)aredevotedtoionic reactions,themostabundantclass,twoforpericyclicreactions(Chapters8and 9),andoneeachfortransitionmetal-catalysedreactions(Chapter10),radical reactions(Chapter11)andphotochemicalreactions(Chapter12).

Thebookisdistinctfromothercontemporarytextbooksinthatitbringsa holisticapproachbyproviding,withinthelimitsofspaceandtime,separate chaptersonthestereochemistryofreactionsofallmechanistictypesranging

fromionic,pericyclic,transitionmetal-catalysedtoradicalandphotochemical. Thiswouldundoubtedlyhelprevealtheunifyingprinciplesforstereochemical understandingandprediction.Anotherimportantdifferencebetweenthisbook andothersistheemphasisontheworkingofstereochemistry,specificallyhow todelineatethestereochemistryofproducts.Learningstereochemistryishard work.Ihavefoundthatstudentsareoftennotquitecomfortabletowork stereochemistryforthemselves.Theyneedsomemorehelp.Toaddresstheir concerns,Ihavealwaysbeenlookingforinnovativeapproachestostereochemicalissues.Myeffortshaveproducedsomesimpleandgeneralstereochemical rules/guidelines,someofwhichhavebeenpublishedinthreepapersinthe JournalofChemicalEducation.Thesepublished(alsosomeunpublished) rules/mnemonicshavebeenusedextensivelyintherelevantchaptersasan aidtodrawquicklyandcorrectlytheproductstereochemistryinorganic reactions.

Asanelementoflearningandpedagogy,Ihaveprovidedover150problems withinthechapters,reinforcingthemainthemesinthetext.Ihopethatstudents couldtesttheirlearningimmediatelywhilereadingthroughthechapters.These problemsetsshouldbeconsideredanintegralpartofthecourse.Thedetailed answerstotheproblemswithreferences,wherevernecessary,aregivenin AppendixinPartIV.Ihaveprovidedatotalofabout1,400referencestoprimaryandreviewliterature,witheachchaptercontainingareferencelistat itsend.Thesereferenceswillenablethereaderstogofurtherintothesubject.

Theapproachpresentedinthisbookisdistinctandclasstested.Ihavetried tofindaleveltosuiteveryoneinhis/herownwayfromtheundergraduatetothe researchlevel.Ihopethisbookwillbeofvalueandinteresttothestudents, teachersandresearchersoforganic,biologicalandmedicinalchemistry,and alsotoawidercircleofreadersincludingbiologists,pharmacologists,polymer chemistsandchemistsworkinginindustrywhomightwishtohaveanoverview ofthishighlyfascinatingfieldofchemistry.

Iwouldliketothanktheanonymousreviewersforhelpfulsuggestions.Iam gratefultotheeditorialmembersEmilyM.McCloskeyandAllisonHill, productionmanagerPaulP.Chandramohan,andtheircolleaguesatElsevier forexcellentsupportandcooperation.Finally,IthankmywifeTapasiand mydaughterSudiptafortheircontinuoussupportandmysonTirthaforhis activehelpinartworkandreferencing.Icouldnotfinishwithoutthanking mylittlegranddaughterAdritawhohasprovidedmethenecessaryfillipduring thepreparationofthisbook.

Abbreviations

Ac acetyl(MeCO)

acac acetylacetonato(MeCOCHCOMe )

AIBN azobisisobutyronitrile[Me2C(CN)N]N(CN)CMe2]

Alpine-Borane B-isopinocamphenyl-9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane

AQN anthraquinone

9-BBN 9-borabicyclo[3.3.1]nonane

BINAL-H binaphthyllithiumaluminiumhydride

BINAP 2,20 -bis(diphenylphosphino)-1,10 -binaphthalene

BINOL 1,10 -bi-2-naphthol

Bn benzyl(PhCH2)

Boc tertiary-butoxycarbonyl(Me3COC]O)

box bis-oxazoline

bpy 2,20 -bipyridine

Bs brosylor p-bromobenzenesulphonyl(4-BrC6H4SO2)

Bu butyl[Me(CH2)3]

i-Bu isobutyl(Me2CHCH2)

s-Bu secondary-butyl[MeCH2C(Me)H]

t-Bu tertiary-butyl(Me3C)

Bz benzoyl(PhCO)

CAN cerium(IV)ammoniumnitrate[Ce(NH4)2(NO3)6]

Cbz benzyloxycarbonyl(PhCH2OC]O)

CD circulardichroism

CE Cottoneffect

CIR chiralinducingreagent

cod 1,5-cyclooctadiene

mCPBA meta-chloroperbenzoicacid(3-ClC6H4CO3H)

CSP chiralstationaryphase

Cy cyclohexyl(C6H11)

DAIB 3-exo-(dimethylamino)isoborneol

dba trans,trans-dibenzylideneacetone[(PhCH]CH)2CO] de diastereomericexcess

DET diethyltartrate

DHQ dihydroquinine

DHQD dihydroquinidine

DIBAL-H diisobutylaluminiumhydride(i-Bu2AlH)

DIP-Cl diisopinocamphenylboronchloride(Ipc2BCl)

DIPT diisopropyltartrate

DMAD dimethylacetylenedicarboxylate(MeO2CC^CCO2Me)

DME 1,2-dimethoxyethane(MeOCH2CH2OMe)

DMF N,N-dimethylformamide(Me2NCH¼O)

DMSO dimethylsulphoxide(Me2S]O)

dr diastereomerratio

DTBP 2,6-di-t-butylpyridine

e electron

ee enantiomericexcess

ESR electronspinresonance

Et ethyl(MeCH2)

FMO frontiermolecularorbital

fod 2,2-dimethyl-6,6,7,7,8,8,8-heptafluoro-3,5-octanedionate

1G/2G/3G/4G first/second/third/fourthgeneration

gb gauche-butane

GC gaschromatography

HOMO highestoccupiedmolecularorbital

HMPA hexamethylphosphoramide[(Me2N)3P]O]

HPLC highperformanceliquidchromatography

IND N-carboxy-indoline

IR infrared

ISC intersystemcrossing

Ipc2BH diisopinocamphenylborane

Ipc2BOTf diisopinocamphenylborontriflate

KHMDS potassiumhexamethyldisilazide[(Me3Si)2NK]

LCAO linearcombinationofatomicorbitals

Lcp leftcircularlypolarized

LDA lithiumdiisopropylamide(i-Pr2NLi)

L-DOPA (S)-30 ,40 -dihydroxyphenylalanine

LiHMDS lithiumhexamethyldisilazide[(Me3Si)2NLi]

LiTMP lithiumtetramethylpiperidide

L-Selectride lithiumtri(sec-butyl)borohydride[Li(s-Bu)3BH]

LUMO lowestunoccupiedmolecularorbital

2,6-Lutidine 2,6-dimethylpyridine

Me methyl(CH3)

Meerwein’s salt trimethyloxoniumtetrafluoroborate(Me3 O + BF4 )

Ms mesylormethanesulphonyl(MeSO2)

NAD+ nicotinamideadeninedinucleotide

NADH nicotinamideadeninedinucleotidehydride(reducedformof NAD+)

NaHMDS sodiumhexamethyldisilazide[(Me3Si)2NNa]

NBS N-bromosuccinimide

NGP neighbouring-groupparticipation xx Abbreviations

Abbreviations xxi

NMO N-methylmorpholine-N-oxide

NMR nuclearmagneticresonance

op opticalpurity

ORD opticalrotatorydispersion

Oxone potassiumperoxymonosulphate(2KHSO 5 KHSO4 K2SO4)

Ph phenyl(C6H5)

PHAL phthalazine

PHOX phosphinooxazoline

PMP 1,2,2,6,6-pentamethylpiperidine

PPTS pyridinium p-toluenesulphonate

Pr propyl[Me(CH2)2]

i-Pr isopropyl(Me2CH)

2-Py 2-pyridinyl

QP quininehypophosphite

QDP quinidinehypophosphite

RAMP (R)-1-amino-2-(methoxymethyl)pyrrolidine

Red-Al sodiumbis(2-methoxyethoxy)aluminiumhydride [NaAlH2(OCH2CH2OMe)2]

Rcp rightcircularlypolarized

r.t. roomtemperature

SAEP (S)-1-amino-2-(1-ethyl-1-methoxypropyl)pyrrolidine

SAMP (S)-1-amino-2-(methoxymethyl)pyrrolidine

SET singleelectrontransfer

SOMO singlyoccupiedmolecularorbital

TADDOLs α,α,α0 ,α0 -tetraaryl-1,3-dioxolane-4,5-dimethanols

TAPA α-(2,4,5,7-tetranitro-9-fluorenylideneaminooxy) propionicacid

TEMPO 2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl

TBDMS tertiary-butyldimethylsilyl(t-BuMe2Si)

TBDPS tertiary-butyldiphenylsilyl(t-BuPh2Si)

Tf triflylortrifluoromethanesulphonyl(CF3SO2)

TFA trifluoroaceticacid(CF3CO2H)

TFAE 2,2,2-trifluoro-1-(9-anthryl)-ethanol

TfO triflate(CF3 SO3 )

THF tetrahydrofuran

TIPS triisopropylsilyl(i-Pr3Si)

TLC thinlayerchromatography

TMEDA N,N,N0 ,N0 -tetramethylethylenediamine[Me2N(CH2)2NMe2]

TMS trimethylsilyl(Me3Si)

TOT tri-o-thymotide

Ts tosylor p-toluenesulphonyl(4-MeC6H4SO2)

TS transitionstructure

UV ultraviolet

Acyclicmolecules1: Conformationandsymmetry

Organicstereochemistry1–4 isthechemistryoforganicmoleculesinthreedimensional,andisanintrinsicpartofallorganicchemistry.Organicstereochemistryisusuallyfactorizedintostereochemistryofmolecules(static aspects)andstereochemistryofreactions(dynamicaspects).Stereochemistry ofmoleculesbroadlyreferstoconformationandconfiguration.Inthischapter, wewilldescribetheconformationandsymmetryofacyclicmolecules.

1.1Stereoisomerisminmolecules

Theconstitutionofamoleculeisdefinedbythesequenceofatomsandbonds buildingupthemolecule.Moleculeswiththesamemolecularformulabutwith adifferenceinconstitution(bondingconnectivity)arecalled constitutionalisomers.Forexample,1-buteneand2-butenearetwoconstitutionalisomersof C4H8.Thedifferencesbetweentheconstitutionalisomersare topological. Again,moleculeswithidenticalconstitutioncandifferintheirstereochemical structure,i.e.arrangementofatomsorgroupsinthree-dimensionalspace.Such moleculeswiththesameconstitutionbutdifferentstereochemicalarrangements arecalled stereoisomers.Stereoisomers,inturn,maydifferinconformation (conformationalisomersorconformers)orconfiguration(configurationalisomers).Aconfigurationalisomermayexistinseveralconformationalisomers. Thestereoisomers(conformationalorconfigurational)arefurtherclassified into enantiomers and diastereomers.Enantiomersarethestereoisomersthatare mirrorimagesofeachother.Notably,theenantiomericrelationshipcanexist onlybetweentwostereoisomers.Sincethetwoenantiomersdonotdifferin thedistancesbetweentheconstitutionallyequivalentatomsbutdifferwhen oneisreflectedinamirrorplane,theirdifferenceis topographical.Ontheother hand,stereoisomersthatare not mirrorimagesofeachotherarecalleddiastereomers.Thus,thestereoisomersthatarenotenantiomersarediastereomers. Evidently,thediastereomericrelationshipispossiblebetweentwoormorestereoisomers.Asthedistancesbetweentheconstitutionallyequivalentatomsof

thediastereomersaredifferent,theirdifferenceis geometric.Fortheclassificationofisomerism,seealso Fig.2.1 (Chapter2).

1.2Representationoftetrahedralmolecules:Perspective (flyingwedge,zigzag)andprojection(Fischer,sawhorse, Newman)formulas

Atetrahedralsp3 carbonisbondedtofourligands(atomsorgroups).Ofthefour bonds,a maximumoftwobonds canlieonaplane(say,theplaneofthepaper) whenonebond(third)isabovetheplaneandtheother(fourth)isbelowthe plane,asshownforCHFClBr 1.1 (Fig.1.1).Todrawthetetrahedralstructure, thefollowingconventionisadoptedinthistext:aboldbondinwedgedform indicatesafront(up)ligand;ahashedbondinuntaperedformindicatesarear (down)ligand.

Therepresentation 1.1 iscalledaflyingwedgeformula.Arotationaround theC Hbondlyingontheplanecanplaceotherthreeligands(F,Cl,Br)outof theplane 1.2 (useamolecularmodel).Inthisrepresentation,onlyonebond (C H)islyingontheplane.Now,iftheC Hbondistiltedbackwards,arepresentation 1.3 isobtainedwhennobondislyingontheplane.Thistypeofrepresentationinwhichtwohorizontalbondslieabovetheplaneandtwovertical bondsarebelowtheplanecanbetransformedintoaprojectionformulacalled theFischerprojection.Therepresentations 1.1–1.3 indicateperspectiveformulas.Theprojectionsofthebondsintheperspectiveformula 1.3 ontheplaneof thepapergiveaFischerprojection 1.4.Rememberthathorizontalandvertical bondsinaFischerprojectioncorrespondtoabovetheplaneandbelowtheplane bondsrespectively.Allfourrepresentations(1.1–1.4)areequivalent.

Agivenperspectiveorprojectionformulacanbetransformedintoequivalentformula(s)byrotatingingroupsofthree,orbymakingtwo(orevennumber)interchanges. Fig.1.2AshowsthataflyingwedgeformulaofCHFClBris convertedintoanequivalentformulabyclockwiserotationofthreeligands(F, Br,Cl)through120degreesaroundC Hbondorbymakingtwointerchanges asindicated.SimilarproceduresalsoapplytoaFischerprojection,asshownin Fig.1.2B.Notethatkeepinganyligand(say,H)fixed,theotherthreeligands(F, Cl,Br)arerotated.Thisprocedurecanberepeatedtodrawotherequivalent Fischerprojections.Asshownin Fig.1.2B,aFischerprojectioncanalsobe

FIG.1.1 RepresentationsofatetrahedralmoleculeCHFClBrinperspectiveformulasandFischer projection.

FIG.1.2 Methodsfordrawing(A)equivalentflyingwedgeformulasand(B)equivalentFischer projectionsforatetrahedralmoleculeCHFClBr.

rotated180degreesintheplanetoobtainanequivalentFischerprojection.

Fig.1.2BalsoshowsthattwointerchangesgiveanequivalentFischerprojection.Rememberthatanytwoligandscanbechosenforanactofexchange. TherepresentationsofaC Cbondwiththespatialdispositionofassociatedligandsareneededinstereochemicaldescriptions.Thesimplestmolecule withaC Cbondisethane.FormoleculeswithanumberofC Cbonds,a stereochemicalrepresentationoftenneedstobedrawnwithrespecttoa particularC Cbond.Asforexample,consider2-bromo-3-chlorobutane (MeCHBrCHClMe)inastaggeredconformationandinaneclipsedconformation(see Section1.3).

Fig.1.3Ashowsperspectiveformulas(flyingwedgeandzigzag)andprojectionformulas(sawhorseandNewman)ofastaggeredconformationof2-bromo3-chlorobutane.TheflyingwedgeformulaisdrawnviewingtheC2 C3bond sideways (useamolecularmodel)whenthefour-carbonchainliesintheplane ofthepaper.Notethat,foreachtetrahedralcarbonC2orC3,twobondsareon theplane,onebondisabovetheplaneandtheotherisbelowtheplane.Ifthe C2 C3bondisviewedin oblique fashion,oneobtainsasawhorseprojection formula,inwhichBrandClareonthesamesideoftheC Cbondasinthe equivalentflyingwedgeformula.ANewmanprojectionformulaisobtained whentheC2 C3bondisviewed end-on.Themaincarbonchainoftheflying wedgeformulacanalsobedrawnasahorizontal zigzag chainwithligands

FIG.1.3 RepresentationsofaC Cbondandassociatedligandsof2-bromo-3-chlorobutane: (A)astaggeredconformationinflyingwedge,sawhorse,Newmanandzigzagformulas,and (B)aneclipsedconformationinflyingwedge,sawhorse,NewmanandFischerformulas.

(otherthanH)pointingupordown.Thisperspectivezigzagformula(devisedby Masamune)alwaysdenotesastaggeredconformation.Azigzagformuladoes notrepresentaneclipsedconformation.

Fig.1.3Bshowsaperspectiveformula(flyingwedge)andprojectionformulas(sawhorse,NewmanandFischer)foraneclipsedconformation.Theflying wedge,sawhorseandNewmanformulasaredrawninasimilarmanneras describedabove.Notethat,intheNewmanprojection,theligandsontheback carbon(C3)areartificiallyrotatedalittlesothattheyarenotobscured completely.IntheFischerprojection,horizontalandverticalligandsatthe C2 C3bondindicateabovetheplaneandbelowtheplaneligandsrespectively.Incontrasttoazigzagformula,aFischerprojectionalwaysdenotes aneclipsedconformation,anddoesnotrepresentastaggeredconformation.

1.3Conformation

Conformationhasbeendefined5 as“thespatialarrangementoftheatoms affordingdistinctionbetweenstereoisomerswhichcanbeinterconvertedby rotationsaboutformallysinglebonds.”Thetermhasbeenextendedtoinclude inversionattrigonalpyramidalcentres(seelater Section2.5.2).Conformational analysisreferstothestudyoftherelativestabilityofconformationsandrelating conformationtothepropertiesandreactivityofmolecules.SinceaC C σ bondiscylindricallysymmetrical,internalrotationattheC Cbondisnot likelytoaffectthebondorbital.However,therotationabouttheC Cbond isnotabsolutelyfreeandthereoccursanenergybarriertorotation.ConformationsalsoariseasaresultofrotationaboutC NandC Obonds.

FIG.1.4 Apositivetorsionangle(ϕ).

1.3.1Torsionanglesandtorsionalstrain

InanonlinearchainoffouratomsA C1 C2 B,thetorsionangle(ϕ)forthe twobondsA C1andC2 Bisdefinedastheanglebetweentheprojectionsof A C1andC2 BonaplaneperpendiculartoC1 C2(Fig.1.4).Thetorsion anglehasbothmagnitudeandasign.LookingalongtheC Cbondin either direction(C1 ! C2orC2 ! C1),iftheturnfromthefrontatomtotherearatom isclockwise, ϕ ispositiveandiftheturnisanticlockwise ϕ isnegative.

Internalrotationchangesthetorsionangle.Conformationmaybedescribed intermsofexactmagnitudeandsignof ϕ.However,whenexactvaluesof ϕ are notknownorrelevant,conformationmaybedescribedusingarangeoftorsion angles( 30degrees),knownasKlyne–Prelogclassification6 (Table1.1).

Thedihedralangleisatermsimilartothetorsionanglebutunlikeatorsionangle,thedihedralangleisanunsignedangle.Torsionanglesof 120 and 60degrees(see Table1.1)correspondtodihedralanglesof240and 300degrees,respectively.Thetermdihedralanglewillnotgenerallybeused inthistext.

Thetorsionalstrain(orPitzerstrain)referstotheinteractionthatleadstothe variationofpotentialenergyasafunctionoftorsionangle.Thetorsionangle

TABLE1.1 Klyne–Prelogspecificationoftorsionangles.

Torsionangle(ϕ)(degrees)Designation

0 30( 30to+30)synperiplanar(sp)

+60 30(+30to+90)+synclinal(+ sc)

+120 30(+90to+150)+anticlinal(+ ac)

180 30(+150to 150)antiperiplanar(ap)

120 30( 150to 90) anticlinal( ac)

60 30( 90to 30) synclinal( sc)

Synclinal(ϕ 60degrees)isoftencalledgauche(g+ +60degrees,g 60degrees). Antiperiplanar(ϕ 180degrees)isfrequentlycalledanti.

functionisnaturallyaFourierseries.However,forasimpleC(sp3) C(sp3) singlebond,thetorsionalpotential(Vϕ)appearstofollowasimplecosine functionas

where V0 isaconstant.ForaC C C Cchain, V0 is3.1kcalmol 1 . 7 When ϕ ¼ 0degreesfortheeclipsed(synperiplanar)conformation,theEq. (1.1) gives Vϕ ¼ V0,i.e.thetorsionalpotentialisatamaximum.Thetorsionalpotentialisat aminimum(Vϕ ¼ 0)when ϕ ¼ 60degreesforthestaggered(synclinal) conformation.

1.3.2NonbondedvanderWaalsinteractions

Atinfinitedistance,theenergyofinteractionoftwononbondedatomsiszero. Asthetwoatomsapproacheachother,anattractiveforce(Londonordispersion force)operateswhichistakenas ar 6 (a isaconstantandristheinternuclear distance).Thisleadstoaloweringoftheenergy.Atastillcloserdistance,a repulsiveforceduetoclosed-shellrepulsiontakesplacewhichisexpressed as br 12 (b isaconstant).Theoverallnonbondedpotential(Vnb)isthen expressedbyEq. (1.2),calledaLennard-Jonespotential.

Fig.1.5 showsaplotof Vnb againstr. vanderWaalsradiusreferstothedistancebetweentwononbondedatomsat whichthereisnonetattractionorrepulsion.Atthispoint,thedistance(r0 ) betweenthetwoatomsisthesumoftheirvanderWaalsradii.Nonbondedinteractionsmaybeattractiveorrepulsivedependingontheinternucleardistance. Whenthedistancebetweentwospecifiedatomsislessthanthesumoftheir vanderWaalsradii,theyrepeleachother.Suchrepulsionduetocrowdingis referredtoasvanderWaalsstrainorstericstrain.

FIG.1.5 NonbondedvanderWaalsinteractionsbetweentwoatoms.

TheapproximatevaluesofvanderWaalsradii(inA ˚ )ofafewatomsor groupsaregivenbelow.

1.3.3Molecularmechanics

Onlyaverybriefintroductiontomolecularmechanicsispresentedhere.An overviewandageneralaccountofthemethodsofmolecularmechanicscan befoundelsewhere.8,9

Straininamoleculearisesfromanonidealmoleculargeometryandseveral strainfactorscontributetothetotalstrainenergyofthemolecule.Theseinclude bondlengthstrain,bondanglestrain,torsionalstrainandnonbondedinteractions.Thetotalstrainenergy(Vstrain)isgivenby

where Vr isbondlengthstrainduetobondstretchingorcompression, Vθ isbond angledeformationstrain, Vϕ istorsionalstrain(Eq. 1.1)and Vnb isnonbonded interactions(Eq. 1.2).

Thebondlengthstrain(Vr)isassumedtofollowaHooke’slawexpressionas

whereristhebondlengthatanygiveninstant,r0 isthemeanorequilibrium bondlengthand kr isaconstantforatypeofbond.Itisassumedthatsuchconstantscanbetransferredbetweenmoleculesinmolecularmechanicscalculation.Typically, Vr is3.2kcalmol 1 ifr r0 isonly10pm(0.1A ˚ )foraC C singlebond.Thusachangeofbondlengthisenergeticallyverycostly.

Thebondanglebendingisalso,toafirstapproximation,aquadratic functionas

where θ θ 0 isthechangeinbondanglefromtheequilibriumbondangletaken as109°280 ,and kθ istheappropriateforceconstant.Typically, kθ is 0.025kcalmol 1 degrees 2 forCCCangle.Thus Vθ isonly0.3kcalmol 1 for a5degreesdeformationinbondangle.Thebondanglechangemayarisefrom therehybridizationofthepivotalatomthroughvariationsofsandpcharacterof theorbitalsinvolvedinbonding.

ItisofnotethatthelistoftermsinEq. (1.3) canbeenlargedtoincludeintramolecularelectrostatic(coulombic)interactions(VE)forpolargroupsif

present,solvation( VS)andcrosstermswithtwoparameterstoimprove Vstrain. Amolecularmechanicscalculationbeginswiththecalculationofstrainenergy ofatrialstructureobtainedfromamolecularmodelorfromasimilarmolecule intheX-raystructuraldatabase.Computationally,thestructureofamolecule with n atomsisavectorof3n Cartesiancoordinates.Bychangingthecoordinatesandrecomputingtheenergies,theenergiesofallgeometriesslightlydeviatedfromtheoriginaltrialstructurecanbeexplored.Theenergyasafunctionof thecoordinatesisminimizedusingasuitablecomputeralgorithmandtheexplorationisrepeateduntilastructureisfoundatanenergyminimumsothatany furtherdeformationleadstoahigherenergy.Thestructureattheenergyminimumistakentobethepredictedstructureofthemolecule.Themethodpermits thecalculationofbothstructureandenergy.

Themathematicalfunctions(forcefields)thataccuratelymodelthevarious straininteractionsforawidevarietyofmoleculeshavebeendeveloped.The termforcefieldsignifiesthatthearrayofatomsisinafieldofinteratomic forces.Themethodallowsthestrainenergyofanyparticularconformation tobeestimated.Bycalculatingdifferentenergiesofvariousconformations, itispossibletopredictthelowestenergyconformation.

1.3.4Conformationofethane

ThesimplestmoleculewithasingleC Cbondisethane.Theinternalrotation ofonemethylgrouprelativetotheotherchangesthetorsionangleandgivesrise toconformations.Inprinciple,infinitenumberofconformationsispossible. ThepotentialenergycurveforrotationabouttheC Cbondinethaneshows thattherearethreedegenerateminimaandthreedegeneratemaxima(Fig.1.6).

FIG.1.6 Potentialenergyasafunctionoftorsionangleforethane.

Thethreeminimacorrespondtotorsionangles ϕ ¼ 60degrees,180degrees andrepresentstaggeredconformationswhilethethreemaximacorrespondto eclipsedconformations(ϕ ¼ 0degrees, 120degrees).Theconformationsthat arelocatedattheenergyminimaarecalledconformationalisomersorconformers.Thereforeethanehasthreeindistinguishablestaggeredconformers. Theenergydifferencebetweentheeclipsedandthestaggeredconformationis 2.9kcalmol 1 whichgivestheenergybarriertointernalrotationinethane.10 Thus,atanyinstant,anyindividualmoleculeislikelytobeinthestaggered conformation.Theeclipsedconformationisregardedasatransitionstructure (TS)conformationfortheinterconversionbetweenstaggeredconformations. Theenergybarrierisnotsohigh;atroomtemperaturearapidinterconversion ofstaggeredconformerstakesplacethroughaneclipsedconformation.

1.3.4.1Torsionalbarrierandkinetics

Anideaoftherateofrotationcanbeobtainedfromanestimateofapproximate rateconstantusingtransitionstatetheory.Therateconstant(k)foraprocess derivedfromtransitionstatetheoryisgivenby

where kB isBoltzmannconstantand ΔG¼ isthefreeenergybarrier.Assuming entropytermtobeinsignificantforaconformationalprocess, ΔG¼ istakento betheconformationalenergybarrier(2.9kcalmol 1).Substitutingthisvaluein Eq. (1.6),thevalueof k at25°C(298K)isobtainedas

Therateofrotationat25°Cisthusextremelyfastwithanaveragetime betweencrossingsistotheorderof10 10 s.

Therelativeinstabilityoftheeclipsedconformationisattributedtotorsional strainorPitzerstrain.Anydeviationfromthelowestenergystaggeredconformationisaccompaniedbytorsionalstrainwhichreachesamaximumatthe eclipsedconformation.

1.3.4.2Originofthetorsionalstrain

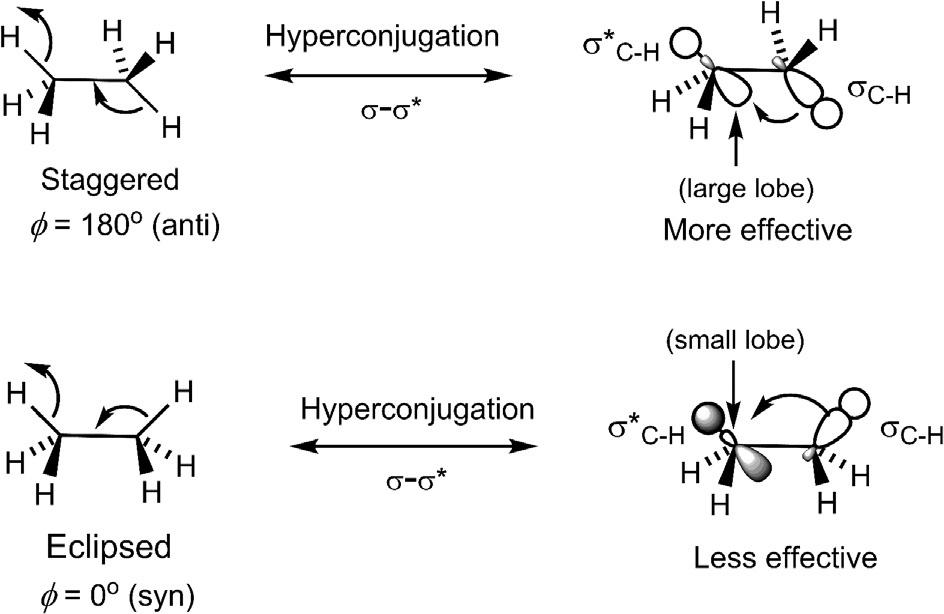

Theoriginoftherotationalbarrier(torsionalbarrier)hasbeenmuch debated.11,12 Thestericrepulsionintheeclipsedconformationisatmosta minorfactorsincetheHatomsofthetwomethylgroupsarebarelywithin thevanderWaalsdistance.Inorbitalterms,thestericrepulsion,ifany,would arisefromthefilledorbital/filledorbitalrepulsionoftheC Hbondsin eclipsedethane.Themainfactorresponsibleforthetorsionalbarrieris σ–σ* hyperconjugation(infrontierorbitalterms,HOMOσ/LUMOσ∗ interaction),

FIG.1.7 Originoftorsionalbarrierinethaneattributedto σ–σ* hyperconjugation.

whichstabilizesthestaggeredconformationmuchmorethantheeclipsedconformation,andhencefavourstheformer(Fig.1.7).

Calculations13 indicatethatifthehyperconjugationeffectsareswitchedoff, eclipsedconformationispreferred.Thushyperconjugation,notthefilled/filled repulsion,istheoriginofthetorsionalbarrierinethane.11,13 Itshouldbenoted thattherearethreeantiH/Hpairsinstaggeredethanesothateach σ–σ* hyperconjugationstabilizesitroughlyby1kcalmol 1.Inotherwords,eachH/H eclipsingraisestheenergyby 1kcalmol 1 .

1.3.4.3Conformationofpropaneandbutaneforrotationabout C1-C2bond

InmoleculesofthetypeH3C CH2R,theconformationalsituationisverysimilar tothatofethane.Thuspropane(R ¼ Me)andbutane(R ¼ Et)hasthreedegeneratestaggeredconformersduetorotationaboutC1 C2bond.Therearealso threedegenerateeclipsedconformations. Fig.1.8 showsonestaggeredand oneeclipsedconformationofpropaneandbutane.DuetoR/H(R ¼ Me,Et) eclipsing,thetorsionalbarrierinpropaneorbutaneishigherthaninethane. Thetorsionalbarrierinpropaneisestimatedtobe 3.4kcalmol 1 . 14,15 Thusa

FIG.1.8 Staggeredandeclipsedconformationsofpropaneandbutaneduetorotationabout C1 C2bond.

Acyclicmolecules1:Conformationandsymmetry Chapter 1 13

Me/Heclipsingcontributes 1.4kcalmol 1 comparedtoH/Heclipsing ( 1kcalmol 1)becauseofanadditionalMe/Hsteric(vanderWaals)repulsion.

Problem1.1 Thetorsionalbarriersinethylhalides(CH3CH2X,X ¼ F,Cl,Br,I) areremarkablysimilar(3.3–3.5kcalmol 1).Explain.

1.3.5ConformationofbutaneforrotationaboutC2 C3bond

TheeclipsedandstaggeredconformationsandpotentialenergycurveasafunctionoftorsionangleforrotationaboutthecentralC2 C3bondinbutaneis shownin Fig.1.9A.Unlikeethane,thethreestaggeredconformersofbutane atpotentialenergyminimaarenotequivalent.Therearetwodegenerateminima correspondingtotwogaucheforms(g+ andg )andonelowestminimumrepresentinganantiform.Thetwogaucheformsarechiralandenantiomericwhile theantiformisachiral(see Figs1.26Band 1.28B).Threeconformersofbutane thuscomprisetwogaucheandoneantiforms.Thegauchebutanesuffersfrom repulsivesteric(vanderWaals)interactionbetweentwoCH3 groupswhich

FIG.1.9 (A)Potentialenergyprofileofbutaneasafunctionoftorsionangleforrotationabout C2 C3bondand(B)gauchebutaneinteractionasH/HvanderWaalsrepulsion.

raisesitsenergyby0.9kcalmol 1 relativetotheantibutanewhichisdevoidof suchstericrepulsion.14,16 Therelativestabilityofgaucheandanticonformersis thusattributedtostericorvanderWaalsstrain.Thistypeofstericinteraction betweentwoCH3 groupsatatorsionangle ϕ ¼ 60degreesisreferredtoas gauche–butane (gb)interaction.Notably,theCH3/CH3 interactioningauche butaneimpliesaH/HvanderWaalsrepulsionbetweentwohydrogenatoms onthetwoCH3 groups(theH Hdistanceis2.35A ˚ whichislessthanthe sumoftheirvanderWaalsradii)(Fig.1.9B).Inorbitalterms,thestericstrain referstothefilledorbital/filledorbitalinteraction(see Section4.2.1).Itispertinenttomentionthatthetorsionangleinthegaucheconformerissomewhat largerthanthe60-degreeangleinaperfectlystaggeredconformation.Thisis becausethevanderWaalsrepulsionrotatesthetwomethylgroupsawayfrom eachotherevenattheexpenseofincreasingtorsionalstrain,andenergyminimizationgivesatorsionangleof65degreesforthegaucheconformation.

Ofthethreemaxima,twodegeneratemaximacorrespondtoeclipsed conformationswithtorsionangles ϕ ¼ 120degreesinvolvingtwofold Me/Heclipsing,whichareoflowerenergythantheothereclipsedconformation at ϕ ¼ 0degreesinvolvingaMe/Meeclipsing.Theenergybarrierfor anti ! gaucheconversion14 viatheTSeclipsedconformationsat ϕ ¼ 120 degreesis3.6kcalmol 1,whereasthatforg ! g + conversionviatheTS eclipsedconformationat ϕ ¼ 0degreesis4.2(5.1 0.9)kcalmol 1 (Fig.1.9A). Itshouldbenotedthattheheightoftheenergybarrierbetweenthetwoconformers, say,gaucheandantidependsonwhetheritismeasuredfromthesideofthe lessstableconformer(gauche)orthemorestableconformer(anti)(Fig.1.9A).

Problem1.2 Usingeclipsinginteractions,estimatetheincreaseinenergyfor theeclipsedconformationofbutaneat ϕ ¼ 120degreesrelativetotheanti conformerofbutane.

Problem1.3 Theenergydifferencebetweentheeclipsedconformationat ϕ ¼ 0degreesandtheanticonformerofbutaneis5.1kcalmol 1.Estimatethe energeticcostofaCH3/CH3 eclipsinginteraction.

1.3.5.1Conformationalequilibriumandthermodynamic parameters

Theconformationalequilibriumofgaseousbutaneisrepresentedas (Rememberthatgauchebutaneisa1:1mixtureofg+ andg forms).The gauche–antienthalpydifferenceisreferredtoasconformationalenthalpyof butane,whichis0.9kcalmol 1 . Thepopulationofgaucheandanticonformerscanbeestimatedfromthe equilibriumconstant(K)where

ΔG0 isgivenby ΔG0 ¼ ΔH0 TΔS0.Theentropydifference(ΔS0)betweenthe twoconformersarisesmainlyfromentropyofsymmetryandentropyofmixing. (Thetranslationalentropyissame;therotationalandvibrationalentropiesfor thetwoconformers,thoughnotthesame,differbyasmallmargin.)

Theentropyofsymmetry(Ssym)isgivenby R ln σ where σ isthesymmetrynumber.Forbothgaucheandantiforms, σ ¼ 2(see Sections1.5.1and 1.5.2.2).

Theentropyofmixing(Smix)isgivenby R P xi ln xi where xi isthemole fractionofthe ithcomponent.Thegaucheconformerhasa Smix dueto1:1mixingofg+ andg formswhereasthereisno Smix fortheachiralanticonformer.

Therefore,

Thevalueof ΔG0 at25°Cforanti Ð gaucheisestimatedas

ΔG0 ¼ ΔH 0

Hencetheconformationalequilibriumofgaseousbutaneatroomtemperature comprisesapopulationof30%gauche(15%g+ and15%g )and70% antiforms.

Ingeneral,populationsinanytwostates(includingconformationalstates) canbeestimatedfromtheirfreeenergydifference(ΔG0). Table1.2 showsrelativepopulationsintwoconformationalstatesat25°Casafunctionoftheirfree energydifference(ΔG0).

Problem1.4 Thegauche–antienthalpydifferenceofbutaneintheliquidphase (ΔH0 ¼ 0.55kcalmol 1)islowerthanthatinthegaseousphase (ΔH0 ¼ 0.9kcalmol 1).Explain.

1.3.6Conformationof2,3-dimethylbutane

Theconformationalanalysisof2,3-dimethylbutaneprovidesaninteresting case.Herethegaucheandanticonformersappeartohavethesamestability, andthethreeconformers(twogaucheandoneanti)areequallypopulated.

TABLE1.2 Relativepopulationsintwoconformationalstatesasafunction of ΔG0 at298K.

Thisratherunexpectedresultisascribedtobondangledeformationandtheconsequentstericeffect.Inbutane,Me C Hbondangleisclosetotetrahedral.In contrast,Me C Meanglein2,3-dimethylbutaneopensuptonear 114degrees.17,18

Thiswideningofbondangle(Thorpe–Ingoldeffect)leads toenhancedvanderWaalsrepulsioninantiformbutdiminishedstericstrain ingaucheformasshownin Fig.1.10.Thustheantiformisdestabilizedand thegaucheformisstabilizedmakingthemalmostequienergetic.Similarconsiderationsapplytootherbranched-chainalkanesofthetypeRR0 CHCHRR0 . 18,19

FIG.1.10 antiandgaucheconformersof2,3-dimethylbutane.Onlyonegaucheconformer(g ) isshown.

1.3.7Conformationof1,2-dihaloethanesandrelatedmolecules20–22

Themoleculeswithpolarsubstituentspossesssubstantialdipoles;thuselectrostaticeffectsbydipole–dipoleinteractionscomeintoplay(besidesthesteric effects)togoverntherelativestabilityoftheconformers.Themagnitudeof thedipoleinteractionswill,however,besolventdependent(seebelow).

1.3.7.11,2-Dichloroethaneand1,2-dibromoethane

Theconformationalequilibriumfor1,2-dichloroethaneinthegas-phaseis

Ithasbeenobservedthattheanticonformerisfavouredoverthegaucheconformerby0.9–1.3kcalmol 1 . 20 Here,besidesthestericeffects,thegaucheconformerisfurtherdestabilizedbydipole–dipolerepulsion(twoC Cldipolesin gauchearemoreorlessalignedincontrasttoantiwherethetwodipolesare opposed).Thegaucheconformerhasahigherdipolemomentthanantiform inwhichthebondmomentsoftwoC Cldipolescancel.Withriseintemperature,thepopulationofthegaucheformwillincreasewhichwillleadtoan increaseindipolemomentof1,2-dichloroethane.Evidenceforbothgauche andanticonformersintheconformationalequilibriumhasbeenobtainedfrom theIRspectrumofthecompound.Iftheanticonformerwerepopulatedexclusively,1,2-dichloroethanewillhavenodipolemomentandhencewouldbe weaklyIRactive.ThepresenceofsignificantbandsintheIRspectrumsuggests asignificantpopulationofthegaucheconformerinconformationalequilibrium.

Inpolarsolvents,thedipole–dipolerepulsionwillbelesssignificantasthe polarsolventmoleculeswillsurroundthedipolesandtherebyminimizethe dipole–dipolerepulsion.Thepopulationofthegaucheconformerinapolarsolventwillthereforeincrease.Inotherwords,thegaucheconformerwiththehigherdipolemomentwillbenefitfromtheincreasedenergyofsolvation,resulting inanincreaseinthepopulationofthegaucheform.Asthepolarityofthesolvent (whichcorrelateswiththedielectricconstant ε)increases,thegaucheformisless destabilizedbydipolerepulsion,andconsequentlygauche–antienthalpydifference(ΔH0)decreases(Table1.3).

Thesituationin1,2-dibromoethaneissimilar.21 Thegauche–antienthalpy differenceislarger(ΔH0 ¼ 1.4–1.8kcalmol 1)thanthatfor1,2-dichloroethane. Bothstericanddipole–dipolerepulsionscontributetodestabilizethegauche conformer.AsBrislargerthanCl,thestericeffectismoresignificantinthe caseof1,2-dibromoethane.

TABLE1.3 Solventdependenceofgauche–anti enthalpydifference(ΔH0)of1,2-dichloroethane.

Solvent

εΔH0 (kcalmol 1)

Cyclohexane2.00.91

Diethylether4.30.69

Liquid(neat)10.10.31

Acetone20.70.18

ε ¼ dielectricconstant.

1.3.7.21,2-Difluoroethane

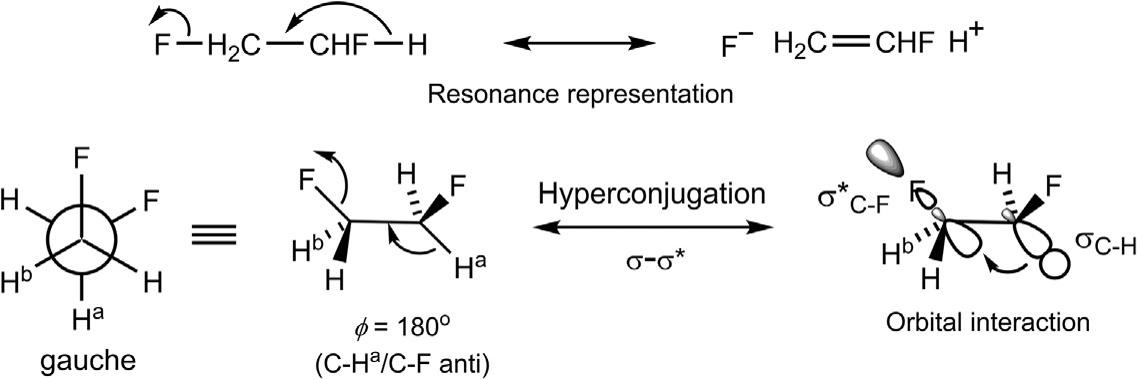

Theconformationalequilibriumfor1,2-difluoroethaneseemsanomalous;the gaucheformisfavouredovertheantiformby0.6–0.9kcalmol 1 eveninthe gasphasenotwithstandingtherepulsivedipole–dipoleinteraction.23

Thereasonforthepreferenceofthegaucheformisattributedtotherelatively smallvanderWaalsrepulsionbetweentwofluorineatoms(vanderWaals radius ¼ 1.5–1.6A ˚ )andastrongstereoelectroniceffectby σC H–σ* C F hyperconjugation24 (Fig.1.11).Thestereoelectronicrequirementforaneffective hyperconjugationistheantiperiplanarityoftheinvolvedC HandC Fbonds (ϕ ¼ 180degrees).Intheanticonformer,noC Fbondisantiperiplanartoa C Hbond.Incontrast,bothC Fbondsinthegaucheconformercanbenefitfromthefavourable σC H–σ* C F overlap(infrontierorbitalterms,

FIG.1.11 Preferenceofthegaucheconformerof1,2-difluoroethaneintermsof σ–σ* hyperconjugation.TheorbitalinteractioninvolvingoneC-Hbond(labelledC Ha)isshownonly.