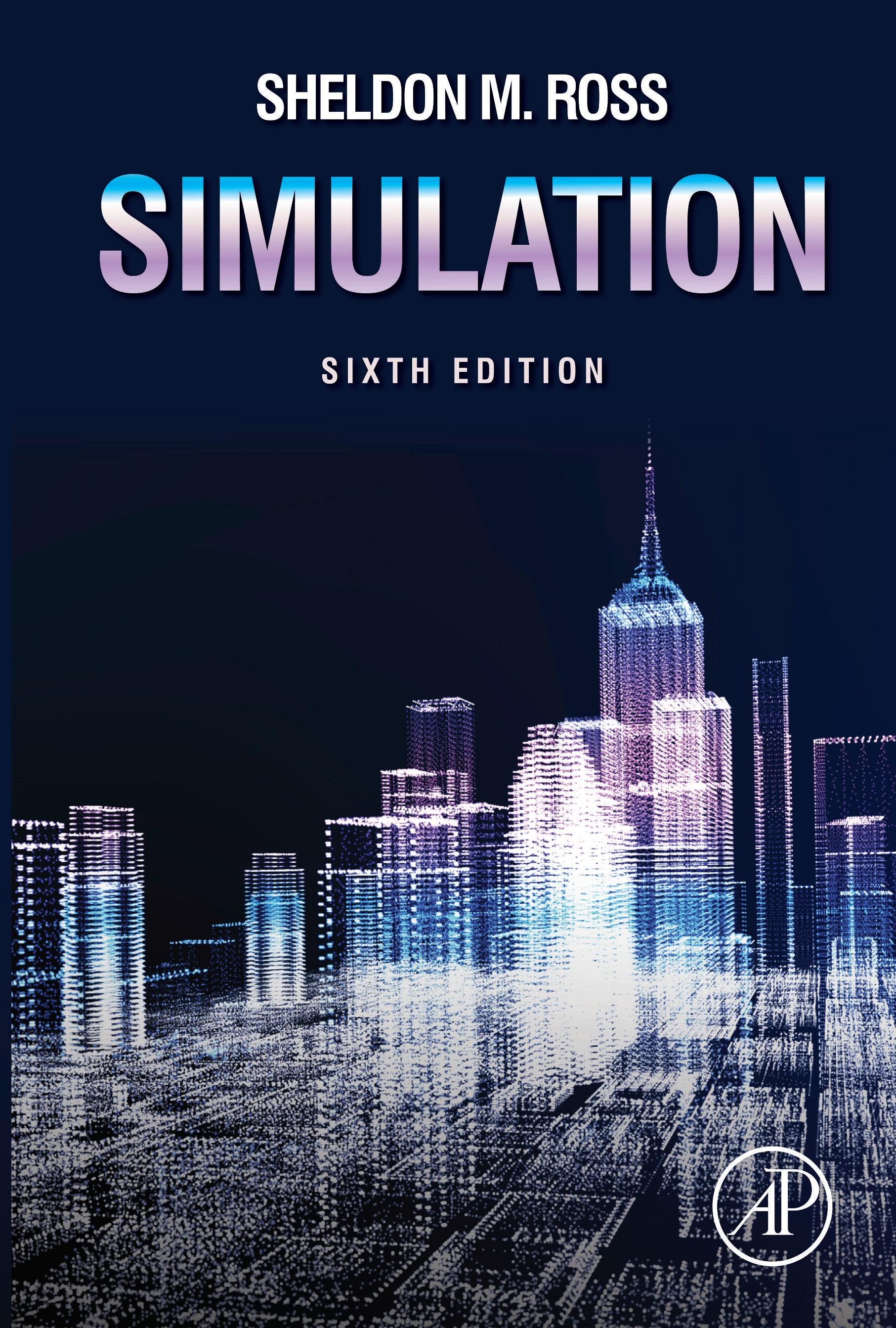

Simulation

SheldonM.Ross

EpsteinDepartmentofIndustrialand SystemsEngineering

UniversityofSouthernCalifornia

LosAngeles,CA,UnitedStates

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier 125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom

Copyright©2023ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationabout thePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyright ClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher (otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperience broadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatment maybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingand usinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuch informationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,including partiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assume anyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability, negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideas containedinthematerialherein.

ISBN:978-0-323-85739-0

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: KateyBircher

EditorialProjectManager: SaraValentino

ProductionProjectManager: ManchuMohan

Designer: VictoriaPearsonEsser

TypesetbyVTeX

PrintedinTheUnitedStatesofAmerica

Lastdigitistheprintnumber: 987654321

5Generatingcontinuousrandomvariables69

6Themultivariatenormaldistributionandcopulas99

This page intentionally left blank

Preface

Overview

Informulatingastochasticmodeltodescribearealphenomenon,itusedtobethat onecompromisedbetweenchoosingamodelthatisarealisticreplicaoftheactual situationandchoosingonewhosemathematicalanalysisistractable.Thatis,theredid notseemtobeanypayoffinchoosingamodelthatfaithfullyconformedtothephenomenonunderstudyifitwerenotpossibletomathematicallyanalyzethatmodel. Similarconsiderationshaveledtotheconcentrationonasymptoticorsteady-stateresultsasopposedtothemoreusefulonesontransienttime.However,theadventoffast andinexpensivecomputationalpowerhasopenedupanotherapproach—namely,to trytomodelthephenomenonasfaithfullyaspossibleandthentorelyonasimulation studytoanalyzeit.

Inthistextweshowhowtoanalyzeamodelbyuseofasimulationstudy.Inparticular,wefirstshowhowacomputercanbeutilizedtogeneraterandom(moreprecisely, pseudorandom)numbers,andthenhowtheserandomnumberscanbeusedtogeneratethevaluesofrandomvariablesfromarbitrarydistributions.Usingtheconcept ofdiscreteeventsweshowhowtouserandomvariablestogeneratethebehavior ofastochasticmodelovertime.Bycontinuallygeneratingthebehaviorofthesystemweshowhowtoobtainestimatorsofdesiredquantitiesofinterest.Thestatistical questionsofwhentostopasimulationandwhatconfidencetoplaceintheresulting estimatorsareconsidered.Avarietyofwaysinwhichonecanimproveontheusual simulationestimatorsarepresented.Inaddition,weshowhowtousesimulationto determinewhetherthestochasticmodelchosenisconsistentwithasetofactualdata.

Newtothisedition

• Newexercisesinmostchapters.

• ThenewSection 5.2.1 showshowwecansimulateorderstatisticsbyfirstsimulatingbetarandomvariables.

• Therearemanynewexamplesinthetext.Example 9p isconcernedwithusing simulationtoestimatetheprobabilitythatasumofindependentandidenticallydistributedrandomvariablesexceedssomevalue.ThisexamplegivestheAsmussen–Kroeseestimatoralongwithanimprovementofit.Example 9q usessimulation argumentstoobtaincomputationalboundson P(X1 = max(X1 ,...,Xn )) when the Xi areindependentrandomvariables.

• ThenewSection 10.2 showshowanidentitydevelopedbyChenandSteinintheir workonboundingtheerrorofPoissonapproximationscanbeusedtoobtaina verylowvarianceestimatoroftheprobabilitythatthesumofBernoullirandom variablesliesinsomespecifiedregion.

• ThenewSection 10.3 introducestheconceptofarandomhazard,andshowshow itcanbeutilizedtoobtainsimulationestimatorswithsmallvariances.

Chapterdescriptions

Thesuccessivechaptersinthistextareasfollows.Chapter 1 isanintroductorychapter whichpresentsatypicalphenomenonthatisofinteresttostudy.Chapter 2 isareview ofprobability.Whereasthischapterisself-containedanddoesnotassumethereader isfamiliarwithprobability,weimaginethatitwillindeedbeareviewformostreaders.Chapter 3 dealswithrandomnumbersandhowavariantofthem(theso-called pseudorandomnumbers)canbegeneratedonacomputer.Theuseofrandomnumbers togeneratediscreteandthencontinuousrandomvariablesisconsideredinChapters 4 and 5.

Chapter 6 studiesthemultivariatenormaldistribution,andintroducescopulas whichareusefulformodelingthejointdistributionofrandomvariables.Chapter 7 presentsthediscreteeventapproachtotrackanarbitrarysystemasitevolvesover time.Avarietyofexamples—relatingtobothsingleandmultipleserverqueueingsystems,toaninsuranceriskmodel,toaninventorysystem,toamachinerepairmodel, andtotheexercisingofastockoption—ispresented.Chapter 8 introducesthesubject matterofstatistics.Assumingthatouraveragereaderhasnotpreviouslystudiedthis subject,thechapterstartswithverybasicconceptsandendsbyintroducingthebootstrapstatisticalmethod,whichisquiteusefulinanalyzingtheresultsofasimulation.

Chapter 9 dealswiththeimportantsubjectofvariancereduction.Thisisanattempttoimproveontheusualsimulationestimatorsbyfindingoneshavingthesame meanandsmallervariances.Thechapterbeginsbyintroducingthetechniqueofusingantitheticvariables.Wenote(withaproofdeferredtothechapter’sappendix)that thisalwaysresultsinavariancereductionalongwithacomputationalreductionwhen wearetryingtoestimatetheexpectedvalueofafunctionthatismonotoneineach ofitsvariables.Wethenintroducecontrolvariablesandillustratetheirusefulnessin variancereduction.Forinstance,weshowhowcontrolvariablescanbeeffectivelyutilizedinanalyzingqueueingsystems,reliabilitysystems,alistreorderingproblem,and blackjack.Wealsoindicatehowtouseregressionpackagestofacilitatetheresulting computationswhenusingcontrolvariables.Variancereductionbyuseofconditional expectationsisthenconsidered,anditsuseisindicatedinexamplesdealingwithestimating n,andinanalyzingfinitecapacityqueueingsystems.Also,inconjunction withacontrolvariate,conditionalexpectationisusedtoestimatetheexpectednumberofeventsofarenewalprocessbysomefixedtime.Theuseofstratifiedsampling asavariancereductiontoolisindicatedinexamplesdealingwithqueueswithvarying arrivalratesandevaluatingintegrals.Therelationshipbetweenthevariancereduction

techniquesofconditionalexpectationandstratifiedsamplingisexplainedandillustratedintheestimationoftheexpectedreturninvideopoker.Applicationsofstratified samplingtoqueueingsystemshavingPoissonarrivals,tocomputationofmultidimensionalintegrals,andtocompoundrandomvectorsarealsogiven.Thetechniqueof importancesamplingisnextconsidered.Weindicateandexplainhowthiscanbean extremelypowerfulvariancereductiontechniquewhenestimatingsmallprobabilities. Indoingso,weintroducetheconceptoftilteddistributionsandshowhowtheycanbe utilizedinanimportancesamplingestimationofasmallconvolutiontailprobability. Applicationsofimportancesamplingtoqueueing,randomwalks,andrandompermutations,andtocomputingconditionalexpectationswhenoneisconditioningonarare eventarepresented.ThefinalvariancereductiontechniqueofChapter 9 relatestothe useofacommonstreamofrandomnumbers.

Chapter 10 introducesadditionalvariancereductiontechniques.Thefirsttwosectionsareconcernedwithusingsimulationtoestimateprobabilitiesconcerning W ,the sumofBernoullirandomvariables.Section 10.1 introducestheconditionalBenoulli samplingmethod,whichcanbeusedtoestimatetheprobabilitythat W ispositive, whichisequivalenttoestimatingtheprobabilityofaunionofevents.Section 10.2 showshowanidentitydevelopedbyChenandSteinintheirworkonboundingthe errorofPoissonapproximationscanbeusedtoobtainaverylowvarianceestimator of P(W ∈ A) foranyset A.Section 10.3 introducestheconceptofarandomhazard, andshowshowitcanbeutilizedtoobtainsimulationestimatorswithsmallvariances. Section 10.4 introducesnormalizedimportancesampling,whichcanbeusedtoestimatetheexpectedvalueofafunctionofarandomvectorwhosedistributionisonly specifieduptoamultiplicativeconstant.Section 10.5 dealswithLatinhypercubesampling.

Chapter 11 isconcernedwithstatisticalvalidationtechniques,whicharestatistical proceduresthatcanbeusedtovalidatethestochasticmodelwhensomerealdata areavailable.Goodnessoffittestssuchasthechi-squaretestandtheKolmogorov–Smirnovtestarepresented.Othersectionsinthischapterdealwiththetwo-sample andthe n-sampleproblemsandwithwaysofstatisticallytestingthehypothesisthata givenprocessisaPoissonprocess.

Chapter 12 isconcernedwithMarkovchainMonteCarlomethods.Thesearetechniquesthathavegreatlyexpandedtheuseofsimulationinrecentyears.Thestandard simulationparadigmforestimating θ = E [h(X)],where X isarandomvector,isto simulateindependentandidenticallydistributedcopiesof X andthenusetheaverage valueof h(X) astheestimator.Thisistheso-called“raw”simulationestimator,which canthenpossiblybeimproveduponbyusingoneormoreofthevariancereduction ideasofChapters 9 and 10.However,inordertoemploythisapproachitisnecessary boththatthedistributionof X bespecifiedandalsothatwebeabletosimulatefrom thisdistribution.Yet,asweseeinChapter 12,therearemanyexampleswherethe distributionof X isknownbutwearenotabletodirectlysimulatetherandomvector X,andotherexampleswherethedistributionisnotcompletelyknownbutisonly specifieduptoamultiplicativeconstant.Thus,ineithercase,theusualapproachto estimating θ isnotavailable.However,anewapproach,basedongeneratingaMarkov chainwhoselimitingdistributionisthedistributionof X,andestimating θ bytheaver-

ageofthevaluesofthefunction h evaluatedatthesuccessivestatesofthischain,has becomewidelyusedinrecentyears.TheseMarkovchainMonteCarlomethodsare exploredinChapter 12.Westart,inSection 12.2,byintroducingandpresentingsome ofthepropertiesofMarkovchains.AgeneraltechniqueforgeneratingaMarkovchain havingalimitingdistributionthatisspecifieduptoamultiplicativeconstant,knownas theHastings–Metropolisalgorithm,ispresentedinSection 12.3,andanapplicationto generatingarandomelementofalarge“combinatorial”setisgiven.Themostwidely usedversionoftheHastings–MetropolisalgorithmisknownastheGibbssampler,and thisispresentedinSection 12.4.Examplesarediscussedrelatingtosuchproblemsas generatingrandompointsinaregionsubjecttoaconstraintthatnopairofpointsare withinafixeddistanceofeachother,toanalyzingproductformqueueingnetworks, toanalyzingahierarchicalBayesianstatisticalmodelforpredictingthenumbersof homerunsthatwillbehitbycertainbaseballplayers,andtosimulatingamultinomial vectorconditionalontheeventthatalloutcomesoccuratleastonce.Anapplication ofthemethodsofthischaptertodeterministicoptimizationproblems,calledsimulatedannealing,ispresentedinSection 12.5,andanexampleconcerningthetraveling salesmanproblemispresented.Section 12.6 dealswiththesamplingimportanceresamplingalgorithm,whichisageneralizationoftheacceptance-rejectiontechnique ofChapters 4 and 5.TheuseofthisalgorithminBayesianstatisticsisindicated.The finalsectionofChapter 12 introducesamethod,calledcouplingfromthepast,thatenablesustogeneratearandomvectorwhosedistributionisexactlyequaltothelimiting distributionoftheMarkovchain.

Thanks

WeareindebtedtoYonthaAth(CaliforniaStateUniversity,LongBeach),DavidButler(OregonStateUniversity),MattCarlton(CaliforniaPolytechnicStateUniversity), JamesDaniel(UniversityofTexas,Austin),WilliamFrye(BallStateUniversity), MarkGlickman(BostonUniversity),ChuanshuJi(UniversityofNorthCarolina), YongheeKim-Park(CaliforniaStateUniversity,LongBeach),DonaldE.Miller (St.Mary’sCollege),KrzysztofOstaszewski(IllinoisStateUniversity),BernardoPagnocelli,ErolPekoz(BostonUniversity),YuvalPeres(UniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley),JohnGrego(UniversityofSouthCarolina,Columbia),ZhongGuan(Indiana University,SouthBend),NanLin(WashingtonUniversityinSt.Louis),MattWand (UniversityofTechnology,Sydney),LianmingWang(UniversityofSouthCarolina, Columbia),EstherPortnoy(UniversityofIllinois,Urbana-Champaign),andRundong Ding(UniversityofSouthernCalifornia)fortheirmanyhelpfulcomments.Wewould liketothankthosetextreviewerswhochosetoremainanonymous.

1 Introduction

Considerthefollowingsituationfacedbyapharmacistwhoisthinkingofsettingupa smallpharmacywherehewillfillprescriptions.Heplansonopeningupat9 A . M .everyweekdayandexpectsthat,onaverage,therewillbeabout32prescriptionscalled indailybefore5 P. M .Hisexperienceisthatthetimethatitwilltakehimtofilla prescription,oncehebeginsworkingonit,isarandomquantityhavingameanand standarddeviationof10and4minutes,respectively.Heplansonacceptingnonew prescriptionsafter5 P. M .,althoughhewillremainintheshoppastthistimeifnecessarytofillalltheprescriptionsorderedthatday.Giventhisscenario,thepharmacistis probably,amongotherthings,interestedintheanswerstothefollowingquestions:

1. Whatistheaveragetimethathewilldeparthisstoreatnight?

2. Whatproportionofdayswillhestillbeworkingat5:30 P. M .?

3. Whatistheaveragetimeitwilltakehimtofillaprescription(takingintoaccount thathecannotbeginworkingonanewlyarrivedprescriptionuntilallearlierarrivingoneshavebeenfilled)?

4. Whatproportionofprescriptionswillbefilledwithin30minutes?

5. Ifhechangeshispolicyonacceptingallprescriptionsbetween9 A . M .and5 P. M ., butratheronlyacceptsnewoneswhentherearefewerthanfiveprescriptionsstill needingtobefilled,howmanyprescriptions,onaverage,willbelost?

6. Howwouldtheconditionsoflimitingordersaffecttheanswerstoquestions1 through4?

Inordertoemploymathematicstoanalyzethissituationandanswerthequestions, wefirstconstructaprobabilitymodel.Todothisitisnecessarytomakesomereasonablyaccurateassumptionsconcerningtheprecedingscenario.Forinstance,we mustmakesomeassumptionsabouttheprobabilisticmechanismthatdescribesthe arrivalsofthedailyaverageof32customers.Onepossibleassumptionmightbethat thearrivalrateis,inaprobabilisticsense,constantovertheday,whereasasecond (probablymorerealistic)possibleassumptionisthatthearrivalratedependsonthe timeofday.Wemustthenspecifyaprobabilitydistribution(havingmean10and standarddeviation4)forthetimeittakestoserviceaprescription,andwemustmake assumptionsaboutwhetherornottheservicetimeofagivenprescriptionalwayshas thisdistributionorwhetheritchangesasafunctionofothervariables(e.g.,thenumberofwaitingprescriptionstobefilledorthetimeofday).Thatis,wemustmake probabilisticassumptionsaboutthedailyarrivalandservicetimes.Wemustalsodecideiftheprobabilitylawdescribingagivendaychangesasafunctionofthedayof theweekorwhetheritremainsbasicallyconstantovertime.Aftertheseassumptions, andpossiblyothers,havebeenspecified,aprobabilitymodelofourscenariowillhave beenconstructed.

Onceaprobabilitymodelhasbeenconstructed,theanswerstothequestionscan,in theory,beanalyticallydetermined.However,inpractice,thesequestionsaremuchtoo difficulttodetermineanalytically,andsotoanswerthemweusuallyhavetoperforma

simulationstudy.Suchastudyprogramstheprobabilisticmechanismonacomputer, andbyutilizing“randomnumbers”itsimulatespossibleoccurrencesfromthismodel overalargenumberofdaysandthenutilizesthetheoryofstatisticstoestimatethe answerstoquestionssuchasthosegiven.Inotherwords,thecomputerprogramutilizesrandomnumberstogeneratethevaluesofrandomvariableshavingtheassumed probabilitydistributions,whichrepresentthearrivaltimesandtheservicetimesof prescriptions.Usingthesevalues,itdeterminesovermanydaysthequantitiesofinterestrelatedtothequestions.Itthenusesstatisticaltechniquestoprovideestimated answers—forexample,ifoutof1000simulateddaysthereare122inwhichthepharmacistisstillworkingat5:30,wewouldestimatethattheanswertoquestion2is 0.122.

Inordertobeabletoexecutesuchananalysis,onemusthavesomeknowledgeof probabilitysoastodecideoncertainprobabilitydistributionsandquestionssuchas whetherappropriaterandomvariablesaretobeassumedindependentornot.Areview ofprobabilityisprovidedinChapter 2.Thebasesofasimulationstudyareso-called randomnumbers.AdiscussionofthesequantitiesandhowtheyarecomputergeneratedispresentedinChapter 3.Chapters 4 and 5 showhowonecanuserandom numberstogeneratethevaluesofrandomvariableshavingarbitrarydistributions. DiscretedistributionsareconsideredinChapter 4 andcontinuousonesinChapter 5 Chapter 6 introducesthemultivariatenormaldistributionandshowshowtogenerate randomvariableshavingthisjointdistribution.Copulas,usefulformodelingthejoint distributionsofrandomvariables,arealsointroducedinChapter 6.Aftercompleting Chapter 6,thereadershouldhavesomeinsightintotheconstructionofaprobability modelforagivensystemandalsohowtouserandomnumberstogeneratethevaluesofrandomquantitiesrelatedtothismodel.Theuseofthesegeneratedvaluesto trackthesystemasitevolvescontinuouslyovertime—thatis,theactualsimulation ofthesystem—isdiscussedinChapter 7,wherewepresenttheconceptof“discrete events”andindicatehowtoutilizetheseentitiestoobtainasystematicapproachto simulatingsystems.Thediscreteeventsimulationapproachleadstoacomputerprogram,whichcanbewritteninwhateverlanguagethereaderiscomfortablein,that simulatesthesystemalargenumberoftimes.Somehintsconcerningtheverification ofthisprogram—toascertainthatitisactuallydoingwhatisdesired—arealsogiven inChapter 7.Theuseoftheoutputsofasimulationstudytoanswerprobabilistic questionsconcerningthemodelnecessitatestheuseofthetheoryofstatistics,andthis subjectisintroducedinChapter 8.Thischapterstartswiththesimplestandmostbasic conceptsinstatisticsandcontinuestoward“bootstrapstatistics,”whichisquiteuseful insimulation.Ourstudyofstatisticsindicatestheimportanceofthevarianceofthe estimatorsobtainedfromasimulationstudyasanindicationoftheefficiencyofthe simulation.Inparticular,thesmallerthisvarianceis,thesmalleristheamountofsimulationneededtoobtainafixedprecision.Asaresultweareled,inChapters 9 and 10, towaysofobtainingnewestimatorsthatareimprovementsovertherawsimulation estimatorsbecausetheyhavereducedvariances.Thistopicofvariancereductionis extremelyimportantinasimulationstudybecauseitcansubstantiallyimproveitsefficiency.Chapter 11 showshowonecanusetheresultsofasimulationtoverify,when somereal-lifedataareavailable,theappropriatenessoftheprobabilitymodel(which

wehavesimulated)tothereal-worldsituation.Chapter 12 introducestheimportant topicofMarkovchainMonteCarlomethods.Theuseofthesemethodshas,inrecent years,greatlyexpandedtheclassofproblemsthatcanbeattackedbysimulation.

Exercises

1. Thefollowingdatayieldthearrivaltimesandservicetimesthateachcustomer willrequire,forthefirst13customersatasingleserversystem.Uponarrival,a customereitherentersserviceiftheserverisfreeorjoinsthewaitingline.When theservercompletesworkonacustomer,thenextoneinline(i.e.,theonewho hasbeenwaitingthelongest)entersservice.

ArrivalTimes:1231639599154198221304346411455537

ServiceTimes:40325548185047182854407212

a. Determinethedeparturetimesofthese13customers.

b. Repeat(a)whentherearetwoserversandacustomercanbeservedbyeither one.

c. Repeat(a)underthenewassumptionthatwhentheservercompletesaservice,thenextcustomertoenterserviceistheonewhohasbeenwaitingthe leasttime.

2. Consideraservicestationwherecustomersarriveandareservedintheirorderof arrival.Let An , Sn ,and Dn denote,respectively,thearrivaltime,theservicetime, andthedeparturetimeofcustomer n.Supposethereisasingleserverandthatthe systemisinitiallyemptyofcustomers.

a. With D0 = 0,arguethatfor n> 0

Dn Sn = Maximum {An ,Dn 1 }

b. Determinethecorrespondingrecursionformulawhentherearetwoservers.

c. Determinethecorrespondingrecursionformulawhenthereare k servers.

d. Writeacomputerprogramtodeterminethedeparturetimesasafunctionof thearrivalandservicetimesanduseittocheckyouranswersinparts(a)and (b)ofExercise1.

This page intentionally left blank

Elementsofprobability

2.1Samplespaceandevents

Consideranexperimentwhoseoutcomeisnotknowninadvance.Let S ,calledthe samplespaceoftheexperiment,denotethesetofallpossibleoutcomes.Forexample, iftheexperimentconsistsoftherunningofaraceamongthesevenhorsesnumbered 1through7,then

S = allorderingsof (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7)

Theoutcome(3,4,1,7,6,5,2)means,forexample,thatthenumber3horsecamein first,thenumber4horsecameinsecond,andsoon.

Anysubset A ofthesamplespaceisknownasanevent.Thatis,aneventisaset consistingofpossibleoutcomesoftheexperiment.Iftheoutcomeoftheexperiment iscontainedin A,wesaythat A hasoccurred.Forexample,intheabove,if

A ={alloutcomesin S startingwith5}

then A istheeventthatthenumber5horsecomesinfirst.

Foranytwoevents A and B wedefinethenewevent A ∪ B ,calledtheunionof A and B ,toconsistofalloutcomesthatareeitherin A or B orinboth A and B Similarly,wedefinetheevent AB ,calledtheintersectionof A and B ,toconsistof alloutcomesthatareinboth A and B .Thatis,theevent A ∪ B occursifeither A or B occurs,whereastheevent AB occursifboth A and B occur.Wecanalsodefine unionsandintersectionsofmorethantwoevents.Inparticular,theunionoftheevents A1 ,...,An —designatedby ∪n i =1 Ai —isdefinedtoconsistofalloutcomesthatare inanyofthe Ai .Similarly,theintersectionoftheevents A1 ,...,An —designatedby A1 A2 ··· An —isdefinedtoconsistofalloutcomesthatareinallofthe Ai .

Foranyevent A wedefinetheevent Ac ,referredtoasthecomplementof A,to consistofalloutcomesinthesamplespace S thatarenotin A.Thatis, Ac occursif andonlyif A doesnot.Sincetheoutcomeoftheexperimentmustlieinthesample space S ,itfollowsthat S c doesnotcontainanyoutcomesandthuscannotoccur.We call S c thenullsetanddesignateitby ∅.If AB =∅ sothat A and B cannotboth occur(sincetherearenooutcomesthatareinboth A and B ),wesaythat A and B are mutuallyexclusive.

2.2Axiomsofprobability

Supposethatforeachevent A ofanexperimenthavingsamplespace S thereisa number,denotedby P(A) andcalledtheprobabilityoftheevent A,whichisinaccord withthefollowingthreeaxioms:

Simulation. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-32-385738-3.00007-9 Copyright©2023ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Axiom1. 0 P(A) 1.

Axiom2. P(S) = 1.

Axiom3. Foranysequenceofmutuallyexclusiveevents A1 ,A2 ,...

n i =1 Ai = n i =1 P(Ai ),n = 1, 2,..., ∞

Thus,Axiom 1 statesthattheprobabilitythattheoutcomeoftheexperimentlies within A issomenumberbetween0and1;Axiom 2 statesthatwithprobability1 thisoutcomeisamemberofthesamplespace;andAxiom 3 statesthatforanysetof mutuallyexclusiveevents,theprobabilitythatatleastoneoftheseeventsoccursis equaltothesumoftheirrespectiveprobabilities.

Thesethreeaxiomscanbeusedtoproveavarietyofresultsaboutprobabilities. Forinstance,since A and Ac arealwaysmutuallyexclusive,andsince A ∪ Ac = S , wehavefromAxioms 2 and 3 that

= P(S) = P A ∪ Ac = P(A) + P Ac orequivalently P Ac = 1 P(A)

Inwords,theprobabilitythataneventdoesnotoccuris1minustheprobabilitythatit does.

2.3Conditionalprobabilityandindependence

Consideranexperimentthatconsistsofflippingacointwice,notingeachtimewhether theresultwasheadsortails.Thesamplespaceofthisexperimentcanbetakentobe thefollowingsetoffouroutcomes:

S = (H, H),(H, T),(T, H),(T, T)

where(H,T)means,forexample,thatthefirstfliplandsheadsandthesecondtails. Supposenowthateachofthefourpossibleoutcomesisequallylikelytooccurandthus hasprobability 1 4 .Supposefurtherthatweobservethatthefirstfliplandsonheads. Then,giventhisinformation,whatistheprobabilitythatbothflipslandonheads?To calculatethisprobabilitywereasonasfollows:Giventhattheinitialfliplandsheads, therecanbeatmosttwopossibleoutcomesofourexperiment,namely,(H,H)or (H,T).Inaddition,aseachoftheseoutcomesoriginallyhadthesameprobabilityof occurring,theyshouldstillhaveequalprobabilities.Thatis,giventhatthefirstflip landsheads,the(conditional)probabilityofeachoftheoutcomes(H,H)and(H,T)

1

is 1 2 ,whereasthe(conditional)probabilityoftheothertwooutcomesis0.Hencethe desiredprobabilityis 1 2 .

Ifwelet A and B denote,respectively,theeventthatbothflipslandonheadsand theeventthatthefirstfliplandsonheads,thentheprobabilityobtainedaboveiscalled theconditionalprobabilityof A giventhat B hasoccurredandisdenotedby

P(A|B)

Ageneralformulafor P(A|B) thatisvalidforallexperimentsandevents A and B can beobtainedinthesamemannerasgivenpreviously.Namely,iftheevent B occurs, theninorderfor A tooccuritisnecessarythattheactualoccurrencebeapointinboth A and B ;thatis,itmustbein AB .Nowsinceweknowthat B hasoccurred,itfollows that B becomesournewsamplespaceandhencetheprobabilitythattheevent AB occurswillequaltheprobabilityof AB relativetotheprobabilityof B .Thatis,

P(A|B) = P(AB) P(B)

Thedeterminationoftheprobabilitythatsomeevent A occursisoftensimplified byconsideringasecondevent B andthendeterminingboththeconditionalprobability of A giventhat B occursandtheconditionalprobabilityof A giventhat B doesnot occur.Todothis,notefirstthat

A = AB ∪ AB c

Because AB and AB c aremutuallyexclusive,theprecedingyields

P(A) = P(AB) + P AB c = P(A|B)P(B) + P A|B c P B c

Whenweutilizetheprecedingformula,wesaythatwearecomputing P(A) by conditioningonwhetherornot B occurs.

Example2a. Aninsurancecompanyclassifiesitspolicyholdersasbeingeitheraccidentproneornot.Theirdataindicatethatanaccidentpronepersonwillfileaclaim withinaone-yearperiodwithprobability.25,withthisprobabilityfallingto.10fora nonaccidentproneperson.Ifanewpolicyholderisaccidentpronewithprobability .4,whatistheprobabilityheorshewillfileaclaimwithinayear?

Solution. Let C betheeventthataclaimwillbefiled,andlet B betheeventthatthe policyholderisaccidentprone.Then

P(C) = P(C |B)P(B) + P C |B c P B c = (.25)(.4) + (.10)(.6) = .16

Supposethatexactlyoneoftheevents Bi ,i = 1,...,n mustoccur.Thatis,suppose that B1 ,B2 ,...,Bn aremutuallyexclusiveeventswhoseunionisthesamplespace S .

Thenwecanalsocomputetheprobabilityofanevent A byconditioningonwhichof the Bi occur.Theformulaforthisisobtainedbyusingthat

A = AS = A ∪n i =1 Bi =∪n i =1 ABi

whichimpliesthat

P(A) = n i =1 P(ABi ) = n i =1 P(A|Bi )P(Bi )

Example2b. Supposethereare k typesofcoupons,andthateachnewonecollected is,independentofpreviousones,atype j couponwithprobability pj , k j =1 pj = 1.

Findtheprobabilitythatthe nth couponcollectedisadifferenttypethananyofthe preceding n 1.

Solution. Let N betheeventthatcoupon n isanewtype.Tocompute P(N),condition onwhichtypeofcouponitis.Thatis,with Tj beingtheeventthatcoupon n isatype j coupon,wehave

P(N) = k j =1 P(N |Tj )P(Tj ) = k j =1 (1 pj )n 1 pj

where P(N |Tj ) wascomputedbynotingthattheconditionalprobabilitythatcoupon n isanewtypegiventhatitisatype j couponisequaltotheconditionalprobability thateachofthefirst n 1couponsisnotatype j coupon,whichbyindependenceis equalto (1 pj )n 1 .

Asindicatedbythecoinflipexample, P(A|B),theconditionalprobabilityof A,giventhat B occurred,isnotgenerallyequalto P(A),theunconditionalprobabilityof A.Inotherwords,knowingthat B hasoccurredgenerallychangesthe probabilitythat A occurs(whatiftheyweremutuallyexclusive?).Inthespecial casewhere P(A|B) isequalto P(A),wesaythat A and B areindependent.Since P(A|B) = P(AB)/P(B),weseethat A isindependentof B if

P(AB) = P(A)P(B)

Sincethisrelationissymmetricin A and B ,itfollowsthatwhenever A isindependent of B , B isindependentof A.

2.4Randomvariables

Whenanexperimentisperformedwearesometimesprimarilyconcernedaboutthe valueofsomenumericalquantitydeterminedbytheresult.Thesequantitiesofinterest thataredeterminedbytheresultsoftheexperimentareknownasrandomvariables.

Thecumulativedistributionfunction,or,moresimply,thedistributionfunction, F oftherandomvariable X isdefinedforanyrealnumber x by

F(x) = P {X x }

Arandomvariablethatcantakeeitherafiniteoratmostacountablenumberofpossiblevaluesissaidtobediscrete.Foradiscreterandomvariable X wedefineits probabilitymassfunction p(x) by

p(x) = P {X = x }

If X isadiscreterandomvariablethattakesononeofthepossiblevalues x1 ,x2 ,..., then,since X musttakeononeofthesevalues,wehave

i =1 p(xi ) = 1

Example2a. Supposethat X takesononeofthevalues1,2,or3.If p(1) = 1 4 ,p(2) = 1 3

then,since p(1) + p(2) + p(3) = 1,itfollowsthat p(3) = 5 12 .

Whereasadiscreterandomvariableassumesatmostacountablesetofpossible values,weoftenhavetoconsiderrandomvariableswhosesetofpossiblevaluesisan interval.Wesaythattherandomvariable X isacontinuousrandomvariableifthere isanonnegativefunction f(x) definedforallrealnumbers x andhavingtheproperty thatforanyset C ofrealnumbers

Thefunction f iscalledtheprobabilitydensityfunctionoftherandomvariable X . Therelationshipbetweenthecumulativedistribution F(·) andtheprobabilitydensity f( ) isexpressedby

F(a) = P X ∈ (−∞,a) = a −∞ f(x)dx Differentiatingbothsidesyields

da F(a) = f(a)

Thatis,thedensityisthederivativeofthecumulativedistributionfunction.Asomewhatmoreintuitiveinterpretationofthedensityfunctionmaybeobtainedfrom Eq.(2.1)asfollows: P a 2 X a + 2 = a + /2 a /2 f(x)dx ≈ f(a)

when issmall.Inotherwords,theprobabilitythat X willbecontainedinaninterval oflength aroundthepoint a isapproximately f(a).Fromthis,weseethat f(a) is ameasureofhowlikelyitisthattherandomvariablewillbenear a .

Inmanyexperimentsweareinterestednotonlyinprobabilitydistributionfunctions ofindividualrandomvariables,butalsointherelationshipsbetweentwoormoreof them.Inordertospecifytherelationshipbetweentworandomvariables,wedefine thejointcumulativeprobabilitydistributionfunctionof X and Y by

F(x,y) = P {X x,Y y }

Thus, F(x,y) specifiestheprobabilitythat X islessthanorequalto x andsimultaneously Y islessthanorequalto y .

If X and Y arebothdiscreterandomvariables,thenwedefinethejointprobability massfunctionof X and Y by

p(x,y) = P {X = x,Y = y }

Similarly,wesaythat X and Y arejointlycontinuous,withjointprobabilitydensity function f(x,y),ifforanysetsofrealnumbers C and D P {X ∈ C,Y ∈ D }=

f(x,y)dxdy

Therandomvariables X and Y aresaidtobeindependentifforanytwosetsofreal numbers C and D

P {X ∈ C,Y ∈ D }= P {X ∈ C }P {Y ∈ D }

Thatis, X and Y areindependentifforallsets C and D theevents A ={X ∈ C } and B ={Y ∈ D } areindependent.Looselyspeaking, X and Y areindependentif knowingthevalueofoneofthemdoesnotaffecttheprobabilitydistributionofthe other.Randomvariablesthatarenotindependentaresaidtobedependent. Usingtheaxiomsofprobability,wecanshowthatthediscreterandomvariables X and Y willbeindependentifandonlyif,forall x,y ,

P {X = x,Y = y }= P {X = x }P {Y = y }

Similarly,if X and Y arejointlycontinuouswithdensityfunction f(x,y),thenthey willbeindependentifandonlyif,forall x , y , f(x,y) = fX (x)fY (y)

where fX (x) and fY (y) arethedensityfunctionsof X and Y ,respectively.

Thefunction F(x) = 1 F(x) = P(X>x) iscalledthetaildistributionfunction.

2.5Expectation

Oneofthemostusefulconceptsinprobabilityisthatoftheexpectationofarandom variable.If X isadiscreterandomvariablethattakesononeofthepossiblevalues x1 ,x2 ,..., thenthe expectation or expectedvalue of X ,alsocalledthemeanof X and denotedby E [X ],isdefinedby

E [X ]= i xi P {X = xi } (2.2)

Inwords,theexpectedvalueof X isaweightedaverageofthepossiblevaluesthat X cantakeon,eachvaluebeingweightedbytheprobabilitythat X assumesit.For example,iftheprobabilitymassfunctionof X isgivenby

p(0) = 1 2 = p(1)

then

E [X ]= 0 1 2 + 1 1 2 = 1 2

isjusttheordinaryaverageofthetwopossiblevalues0and1that X canassume.On theotherhand,if p(0) = 1 3 ,p(1) = 2 3 then

E [X ]= 0 1 3 + 1 2 3 = 2 3

isaweightedaverageofthetwopossiblevalues0and1wherethevalue1isgiven twiceasmuchweightasthevalue0since p(1) = 2p(0).

Example2b. If I isanindicatorrandomvariablefortheevent A,thatis,if

I = 1if A occurs 0if A doesnotoccur then

E [I ]= 1P(A) + 0P Ac = P(A)

Hence,theexpectationoftheindicatorrandomvariablefortheevent A isjustthe probabilitythat A occurs.

If X isacontinuousrandomvariablehavingprobabilitydensityfunction f ,then, analogoustoEq.(2.2),wedefinetheexpectedvalueof X by

E [X ]= ∞ −∞ xf(x)dx

Example2c. Iftheprobabilitydensityfunctionof X isgivenby

f(x) = 3x 2 if0 <x< 1 0otherwise then

E [X ]= 1 0 3x 3 dx = 3 4

Supposenowthatwewantedtodeterminetheexpectedvaluenotoftherandom variable X butoftherandomvariable g(X), where g issomegivenfunction.Since g(X) takesonthevalue g(x) when X takesonthevalue x ,itseemsintuitivethat E [g(X)] shouldbeaweightedaverageofthepossiblevalues g(x) with,foragiven x, theweightgivento g(x) beingequaltotheprobability(orprobabilitydensityinthe continuouscase)that X willequal x .Indeed,theprecedingcanbeshowntobetrue andwethushavethefollowingresult.

Proposition. If X isadiscreterandomvariablehavingprobabilitymassfunction p(x),then

E g(X) = x g(x)p(x) whereasif X iscontinuouswithprobabilitydensityfunction f(x),then

E g(X) = ∞

g(x)f(x)dx

Aconsequenceoftheabovepropositionisthefollowing.

Corollary. Ifaandbareconstants,then

E [aX + b ]= aE [X ]+ b

Proof. Inthediscretecase

E [aX + b ]= x (ax + b)p(x)

= a x xp(x) + b x p(x)

= aE [X ]+ b

Sincetheproofinthecontinuouscaseissimilar,theresultisestablished.

Itcanbeshownthatexpectationisalinearoperationinthesensethatforanytwo randomvariables X1 and X2 E [X1 + X2 ]= E [X1 ]+ E [X2 ]

whicheasilygeneralizestogive

2.6Variance

Whereas E [X ],theexpectedvalueoftherandomvariable X ,isaweightedaverageof thepossiblevaluesof X ,ityieldsnoinformationaboutthevariationofthesevalues. Onewayofmeasuringthisvariationistoconsidertheaveragevalueofthesquareof thedifferencebetween X and E [X ].Wearethusledtothefollowingdefinition.

Definition. If X isarandomvariablewithmean μ,thenthevarianceof X ,denoted byVar(X),isdefinedby

Var(X) = E (X μ)2

AnalternativeformulaforVar(X )isderivedasfollows:

Var(X) = E (X μ)2 = E X 2 2μX + μ 2 = E X 2 E [2μX ]+ E μ 2 = E X 2 2μE [X ]+ μ 2 = E X 2 μ 2

Thatis,

Var(X) = E X 2 E [X ] 2

Ausefulidentity,whoseproofisleftasanexercise,isthatforanyconstants a and b

Var(aX + b) = a 2 Var(X)