The Prince & the Apocalypse 1st Edition

Kara Mcdowell

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-prince-the-apocalypse-1st-editionkara-mcdowell/

ebookmass.com

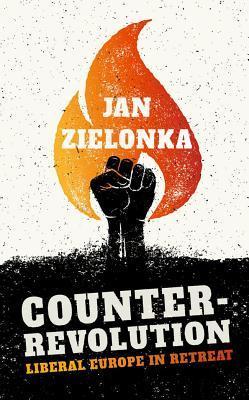

OXFORD

UNIVERSITY PRESS

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in India by Oxford University Press 2/11 Ground Floor, Ansari Road, Daryaganj, New Delhi 110 002, India

© Oxford University Press 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

First Edition published in 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

ISBN-13 (print edition): 978-0-19-948169-9

lSBN-10 (print edltion): 0-19-948169-5

ISBN-13 (eBook): 978-0-19-909182-9

ISBN-10 (eBook): 0-19-909182-X

CONTENTS

Acknowledgements List of AbbreviatiotlS

Introduction: Liberal Democracy and Free Speech

1. Political Offences and Speech Crimes: Comparing Legal Regimes · ·The Past

2. Sedition and Western Liberal Democracies. and the Present

d P · tism· Sedition . Resistance, Suppression, an atno · in Colonial India

Caste, Class, Community, and the Everyday Tales of Law

6. Indian Democracy and the 'Moment of Contradiction'

Conclusion: The Life of a Law and Contradictions of Liberal Democracies Bibliography

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work evolved from my doctoral research at the Department of Political Science, University of Delhi, and bears the imprint of the efforts of no single individual but a collective. I express my sincere thanks to all the faculty members, non-teaching staffs, and fellow research students in the department for their support. I have been extremely fortunate to receive the guidance of noted academics over the years who have shaped my understanding of politics. I am thankful to Achin Vanaik, Pradip Kumar Datta, and Pumima Roy. To Yogendra Yadav I would always remain indebted for his unflinching support and faith in me. I was privileged to receive the insightful comments and words of encouragement from Anuradha Chenoy, Manjari Katju, and Monica Sakhrani, which propelled the work forward.

The doctoral research fellowship at King's College, London, granted by the Ministry of Culture Government of India, was one of the most facilitating experiences fo; this research. I am extremely grateful to the faculty, staff, and students at King's India Institute, King's College, London. The incisive comments of Sunil Khilnani, Conor Gearty, and Sandipto Dasgupta are reflected in this work. I am also thankful to Robert Sharp at English PEN, for sharing his views and for putting me in touch with those involved with the movement for abolition of the offence of sedition in England. I thank the staff of British Library, London, which was virtually my home for over three months, and major parts of the work were written in its reading room which were subsequently revised.

Acknowledgements

This work would be incomplete without the mention of my dear friends, colleagues, and fellow researchers. Om Prakash, Prccti, Vikas, Santana, Subarta, lndrajeet, Anusha, Kamal, Pooja, Kunal, and K.K. Subha-1 cannot thank them enough for their comments, discussions, and overwhelming support over the years. I also thank my colleagues at Gargi College, University of Delhi, for their cheerful support. Friends at People's Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR) and their resilience to struggle have been constantly inspiring. I have benefitted enormously from the various discussions and the work we did together.

Manoranjan Mohanty, Uma Chakravarti, and Gautam Navlakha have never ceased to amaze and inspire me with their passion, commitment, and energy. While working on this book, I have found some of the recent studies theorizing the nature of the liberal democratic states and democratic rights within most engaging. In this regard, the contribution to the field made by Michael Held, Sarah Sorial, Katherine Gelber, Jinee Lokaneeta, and Gautam Bhatia is immense. The conceptual categories innovated and theoretical interventions made by Laura Nader, Julia Eckert, and Ujjwal Singh have benefitted this work enormously.

I am grateful to my two anonymous reviewers whose suggestions for improvement were extremely beneficial, and to Oxford University Press for their guidance and support.

1 thank the staff at the National Archives of India, New Delhi, and the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library, New Delhi for their help. The fieldwork in parts of Haryana, Maharashtra, Delhi, and Bihar would not have been possible without the support and generosity of the people there. Everywhere I went and stayed, 1 felt received and aided. Many of the everyday stories I attempt to theorize in this work bear the imprint of the ordinary and the extraordinary struggles of these people and their institutions; naming a few would belittle the struggles of the thousands.

The immense love and support received from my family, and the autonomy I have been granted, has indelibly shaped this work. Singh and Shweta Singh, would remain the strength behind

To U.N. Singh, Poonam Singh, A.K. Singh, Pushpa Kumar, .K. Smgh, Kinshuk, and Tejrashi Mehrotra, among others, I remam indebted. My soul sisters, Anamika Asthana and Shivani Naram, have been my lifelines. I also thank Jamshed and Jyotsna for

Acknowledgements

b th my grandmothers and Badi familial love. Those who left midway- o Ma-continue to live within me. 1 rvisor: critic, friend, and mens. h my doctora supe ' 1· · 11 him Ujjwal Kumar mg , world view and po ttiCS. o . tor for life, has constantly mdy ch commitment to acttv. ente resear , . h" I owe my interest in praxts-on h b "11" ance of which reflects m ts "th law-t e n 1 k fr "ts ism, and engagement wt ·s reflections on this wor om t own work on the anti-terror laws. Ht various drafts, and persistent inception onwards, critical book. I have deep respect for h ealed mto t lS rt Over encouragement ave cong t d yet unrelentt.ng suppo · Anupama Roy who has been an unsdta e. rably failed at emulating the d h orks an rntse R d UJ·J·wal the years 1 have rea er w To Anupama oy an strength and expression of her argumentts. and unconditionality. f. h .r sheer ove Singh I owe this work, or t et

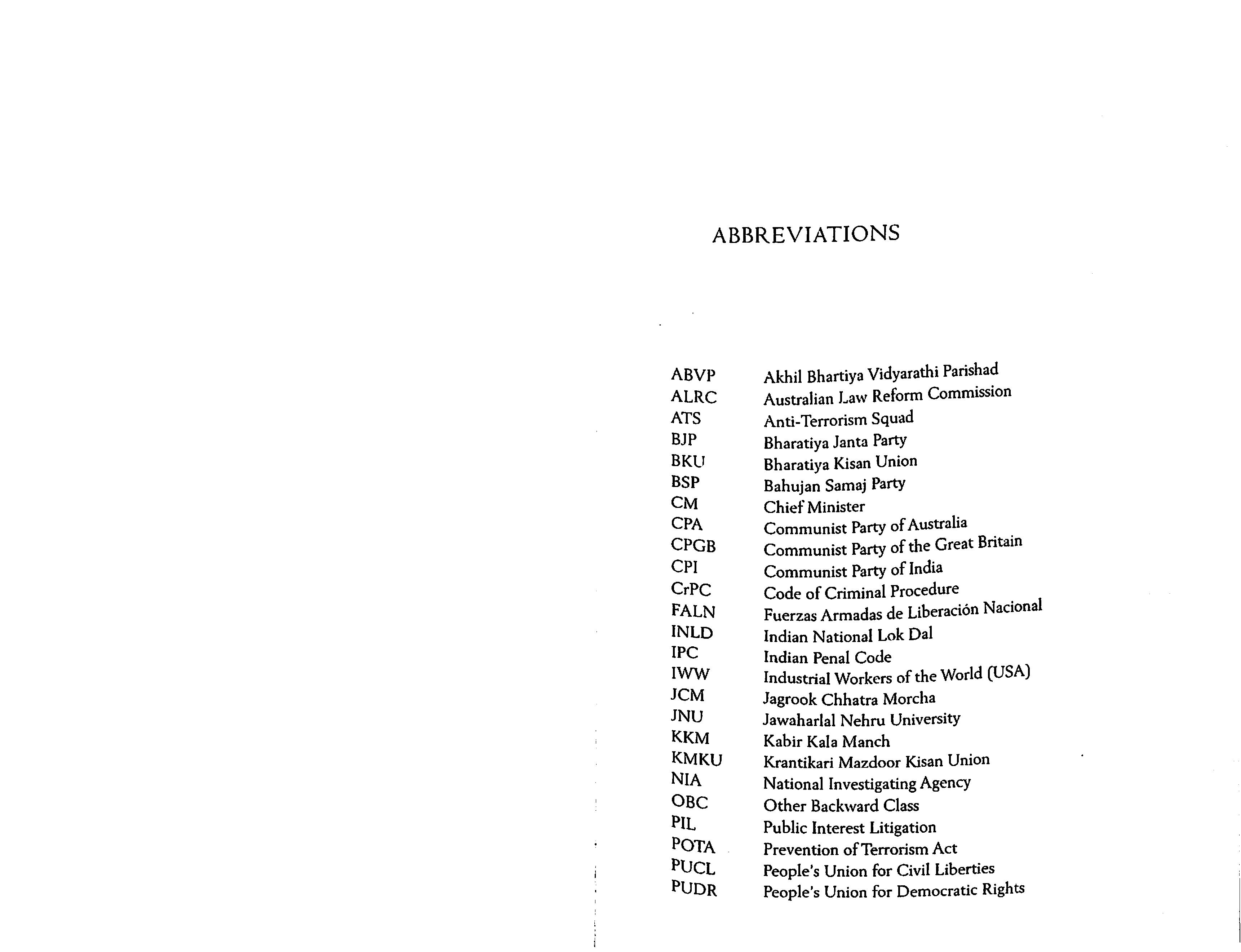

ABBREVIATIONS

ABVP

ALRC

ATS

BJP

BKU

BSP

CM

CPA

CPGB

CPI

CrPC

FALN

INLD

IPC

IWW

JCM

JNU

KKM

KMKU

NIA

0BC

PIL

POTA

PUCL

PUDR

Akhil Bhartiya Vidyarathi Parishad

Australian Law Reform Commission

Anti- Terrorism Squad

Bharatiya Janta Party

Bharatiya Kisan Union

Bahujan Samaj Party

Chief Minister

Communist Party of Australia

Communist Party of the Great Britain

Communist Party of India

Code of Criminal Procedure

Fuerzas Armadas de Liberaci6n Nacional

Indian National Lok Dal

Indian Penal Code

Industrial Workers of the World (USA)

Jagrook Chhatra Morcha

Jawaharlal Nehru University

Kahir Kala Manch

Krantikari Mazdoor Kisan Union

National Investigating Agency

Other Backward Class

Public Interest Litigation

Prevention of Terrorism Act

People's Union for Civil Liberties

People's Union for Democratic Rights

SJSM

TADA

UAPA

Abbreviations

Shiromani Akali Dal

Student Isla · M . . mtc ovement of India

ShJValtk Jan Sangharsh Manch

Terrorist and Disru tiv . . .

Unlawful Activit" pp e Acttvtttes (Prevention) Act tes revention Act

INTRODUCTION

Liberal Democracy and Free Speech

On 1 February 2017 at the University of California, Berkeley, USA, mob violence erupted on campus with 1,500 protesters demanding the cancellation of a public lecture by Milo Yiannopoulos, a British author notorious for his alleged racist and anti-Islamic views. 1 Consequently, event was cancelled triggering a chain of reactions on the desirabilIty and limits of freedom of expression within American democracy. The Left-leaning intellectuals and politicians were accused of allowing the mob violence to become a riot on campus defending it in the name of protest against racism fascism and social injustice. In defending the rights of the protesters not 'illiberal' or hate speech on campus, however, many claimed that the message conveyed was that only liberals had th · h fr 2 e ng t to ee speech.

Almost contemporarily in 2016, in India, a series of criminal cases registered involving the act of sloganeering in support of the nght to self-determination of people in Kashmir. Kashmir is one of the states of the Indian Union where the movement for self-determination

1 New York Times, 2 February 2017 'A Free Speech Battle at the Birthplace of aM , . ovement at Berkeley', available at https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/02/ us/university-california-berkeley-free-speech-milo-yiannopoulos.html?_r=O, accessed: 12 February 2017

2

htt . Matthew Vadum, 6 February 2017, 'The Sedition Left', available at p.//www.frontpagemag.com/fpm/265 71 7/seditious-left-matthew-vadum, accessed: 12 April 2017.

has existed since its integration within the Union in 194 7. Notably, in February 2016, students of Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi, were charged and arrested for sedition for participating in a meeting in which· it was alleged that slogans were raised to support Kashmir's freedom from India.3 In March 2017, in an interview given to India Today, Union Minister Venkaiah Naidu said that 'pro-freedom' slogans will not be tolerated and must be penalized, as they result in violence and endanger national unity. 4 In this case, the justification for restriction on free speech was in the name of protecting the Indian nation state, to which secessionism is interpreted as the biggest threat. The incident at Berkeley, presents with a case, in which restriction on free speech was demanded and justified in the name of protecting what is largely called the 'liberal-democratic' values from 'illiberal' political opinions. In the Indian case, however, the restriction on the right to freedom of expression of individuals was justified in the name of coagulating state security. The brief description above pre-empts the larger framework within which this work is placed, which is the debate over the centrality of free speech and the restrictions on the same. These concerns, however, gain prominence only within a specific context. An authoritarian state which does not recognize the individual as a right-bearing citizen is inappropriate for any debate on freedom to take shape. The appropriate context is informed by a form of government, which we refer to as liberal democracy, which claims to guarantee the liberal right to freedom of speech and expression to all citizens.

As an ideal, as well as an evaluative framework, democracy realizes itself politically through a democratic state. The process of this realization is, however, fraught, since it involves reconciling conflicting tendencies which inhere in the logic of 'democracy' and the logic of the 'state'. A liberal democratic state, it may be said, is a fraught combination of competing tendencies and traditions, since it attempts

3 The Indian Express, 16 March 2016, 'JNU Row: University Report Links Azadi Slogans to "Outs"d " . h 1 ers Wtt Covered Faces' available at http://mdtanexpress.com/artide/indi /' d" .

. . a m ta-news-mdta/}nu-report-hnks-azadt-slogans-tooutstders-wtth-covered-faces/' accessed: 20 March 2016.

4 Naidu's interview giv t I d"

. . . en o n ta Today TV Network, available at http:// mdtatoday.mtoday.in!story/v k · h "d . en ata -nat u-ratsmg-azaadi-slogans-treason-seditmn-law/1/895067 .html, accessed: 10 March 201 7.

. d democracy, on the one hand, and to bring together liberahsm an d th tate on the other. It is in the fd cyan es ' .. the imperatives o emocra ence of these confhcting ten. fr m the converg di . · contestations emergmg 0 peech' of which se 15 a f 'extremes ' . dencies, that the category o . f political speech, an expresston d. · ·s a form 0 a h · 1: b"dden kind emerges. Se ttton • d state whic 1s tor 1 , f th vernment an ' against the authority : e ate criticism, and, therefore, profor exceeding the limtt of legtttm eech and expression. By ratsmg the t t d by the right to freedom of s_p h may be freely exercised, ec e d htch speec 'th' issue of the conditions un er w d clition reveals a dilemma wt m or alternatively legitimately curbe , lds in the tensions between the liberal democracies. This between freedoms of citizens d d the relations •P relative prece ence an and obligations of the state. of the many restrictions on diti n are one . . The laws to penalize se o d ex ression. Hence it ts tmperathe right to freedom of speech an palysis on this account would tive to mention at the democracy and the right not make any sweeping clatms atho' rk is the fate of those forms f 1S wo d · t the to free speech. The concern o des that are uttere agams of expressions within liberal thus is the state of freedom of authority of the state. The uiliority within those forms h gamst e a · expression that citizens ave a th liberal and democratic. of government that claim to be bo

·Amalgam or a Conundrum'?

Liberal Democracy: An Life and Times of Liberal h wrote The d · t the In 1977 when C.B. Macp erson . that existe pnor 0 he excluded the entire democracy. He counted nineteenth century from the frame loh"sttofY of the western democral"tica t · the way the pre-nineteenth-century po 1 d cracy gradually pavmg d th d Is f l'beral emo ' h argue at cies as precursor mo e 0 1 · n Macp erson ki this dtsttnct10 ' 1 d cracy were to its emergence. In rna ng . r to libera emo all models of democracy that existed eties (Macpherson 1977,. P· -class soct . · hip pnv- based on either classless or one . . al equality and c1uzens 11 ). The understanding was that poltttc U eople belonged to the same ileges belonged either to one class or a. pt Greece fitted the model of ·n Anc1en f A h -born class. The Athenian democracy 1 th privilege o t ens . · hip was e 1 ed by one-class society where ctttzens u·c mode s propos 23) Democra propertied men (Held 1987, P· ·

Rousseau in the mid-eighteenth century or Thomas Jefferson towards the end of the eighteenth century envisaged societies with no class distinction (Macpherson 1977, pp. 15-16). Rousseau and Jefferson differed from the Athenian model in the sense that they did not exclude the property-less from the class of citizenry but both presupposed a society in which everyone who could be called a citizen, would have at least a little property to work on, hence a limited property right. Hence, within the supposed class of citizens, there would have been inequality of property but all still belonged to the same class of propertied bodies.

Liberal democratic model, for the first time in the nineteenth century envisaged a form of government for a society that had class divisions and the rights-bearing citizens belonging to different classes. Liberal democracy hence, as Macpherson opined, was essentially a form of government for a capitalist society that sustained the class divisions in the society while guaranteeing the same rights in theory to different classes of citizens. (Macpherson 1977, pp. 9-20).

Liberal democracy came to be identified with a form of government that guaranteed equal rights to all citizens, rule of law, basic civil liberties, and popular sovereignty. It is evident in Macpherson's argument that liberal democracy was an imperative of the liberal state based on capitalist relations. Hence, liberal democracy is referred to as a form of government that became liberal first and then democratic. David Held brings forth this argument in tracing the historical emergence of modem state in the west in which he makes reference to liberal state and liberal democracy as two different forms of modern states (Held 1992, p. 89). The liberal state was founded on the idea of constitutionalism 5 that is, an idea of a limited government, private property, and economy. It upheld the right to life, liberty, and property of the citizens hut the citizens were essentially the property-owning male adult class. It ':as only in the course of many struggles fought for voting rights that umversal adult franchise was established as a governing principle of

th 5 d which emerged as a principle of liberal states, became , e e. feature of liberal democratic states as well. Constitutionalism or garantiSme as Sartori · . d th 1 . ' Wntes, m mo ernity is believed to be teleological where e te os IS securing rights t . d" "d 1 . b o m lVI ua c1tizens y limiting the power of the government. See Sartori 1962, pp. 853 -6 4

t of the ushering in of representgovernmcnt.6 This was the The form that governments ative democracy within the hbera states. took then was called liberal ld be disagreements on h . da1m ere wou

Contrary to Macp erson s 'd t" g these principles had been f, f rnment eno m the fact that a orm o gove the nineteenth century. In 1885, put in place in the west much bhe oCre t<tution commenting on constih V o· t Lawoft e ons.. , w en A. . 1cey _e . . and USA particularly, he traced many tutional democracies m Bntam b k to Common law and other of the principles of liberal 'rule of law' was foremost. 7 'practices of liberties' in Britatn, 10 w f 1 cc al equality of all citizens b d the idea o 1orm Rule of law was ase on . h l"berty of all individuals. d . . ofthe ng t to I d before law an recogmtlon b t the temporal contexts an

Although there may be debates fal"bou 1democracy all accounts of f, h gence o 1 era , th their corollaries or t e emer theoretical underpinnings show e the life of liberal democracy and tts ·b li ...... and democracy. The idea d" · -li era Su• coming together of two tra tttons 1 t was· democratized in the of individuals as capable of self-deve citizens. The democratic sense that this was now applied y ·ghts and at the same time, h . div• ua s n ' government was to protect t e 10 d from unlimited state power. 8 In the individuals were to be protecte

on Moore Jr., 1966, Social Origin of

6 Refer to Chapters 1 and 3 10 Barnngt fthe advent of capitalist democracy D d · h" ran account 0 · · hts emocracy an Dzctators 1p, 10 . trU lefor liberal democrattc ng · in England and USA through bourgeoiS s gg d to Introduction to the Study of M. h r's Forewor k

7 See the Editor, Roger IC ene . h d. 1962 based on his wor a cenv D. pubhs e 10 LAw and Co1zstitution by A. · lcey f l · three constituent parts- . . f rule o aw m f tury ago. Also see Dicey's defimtlon o f rnment secondly, the rdea o art o gove ' . 1 firstly, absence of arbitrary power on P b the result of the ordinary aw . . allawto e legal equality, and thirdly, constitution ofland. See Dicey 1962, pp. 183-205· l . y of liberal democracy into s Macpherson classified the historica JOdumel pmental democracy, and the the eve o S three models: the protective democracy, d T" es of Liberal Democracy. ee equilibrium democracy in his work The Life an rm riated by David Held, Macpherson 1977. The earlier t-.vo models we;e app::e demo·cracy was based later to denote the phase of liberal democracy. rotec 1democracy talked about l . h"l developmenta on the idea of constitutiona 1sm w 1e . . l" m as a necessary meaparticipation in political life along with constltllutlodna 1 ;lopment of individuals. thefu est ev sure to secure individual rights, to ensure See Held 1987.

sum, it was the individual and her rights that were at the centre of the philosophy of liberal democracy.

It is evident hence, that the trajectory of liberal democracy, and this is strictly speaking for the west, places the liberal tradition before the democratic one at least in the historical time line. Bhikhu Parekh argues that liberal democracy is 'liberalized democracy', that is, democracy defined and structured within the limits set by liberalism. 9 Liberalism believes in the idea of individual as prior to state and possessing rights that are above and before the state. The democratic system arranged within the liberal paradigm then accepts the state to maintain a system of individual rights in which people can control and compel the government and the authority of state (Parekh 1992, p. 165). Within this arrangement it comes to fore that the nature of state within liberal democracy is defined along the parameters of liberalism. The state is a human creation, created to safeguard the rights of individuals, and the individuals retain the right to withdraw support from political authority if it violates the rights it was supposed to protect. 10

This is not to say that liberal democracy stands out to be the perfect peaceful amalgamation of the two different traditions, as Chantal Mouffe writes, this union was full of struggles and imposed many limits on how liberal democracies were to function. 11 According to her, the

9

Bhikbu Parekh makes the argument in context ofliberal democracy and it being a form of government specific to a context, that is, the western societies, and its universal applicability is something that the world outside of the west must be apprehensive o£ See Parekh 1992, pp. 160-75.

• 10 The social contract tradition within liberalism in the writings of, primartly, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke took the above position regarding the nature of state and conditions of political obligation. In Hobbes' thoughts, right to rebel was a right available to individuals only when threatened with life by thfehstate. See Jones 2002, p. 19. Locke, however, laid down a systematic defence

0 t . h d e ng t to issolve the sovereign government when it failed to fulfill its responsibilities t t d S h

XI , rus · ee Jo n Locke, Two Treatises of Government, Chapter Of the Dissolution of Government', in The Works of John Locke. A New Edztion, Corrected in 11 , , 1 W Sh d ' en vo umes. Vol. V. London: Printed for Thomas Tegg; G ·.ffi an Son; G. Offor; G. and J. Robinson; J. Evans and Co.: Also R. n 1 nan Co. Glasgow; and J. Gumming, Dublin 1823. · 1

Chantal Mouffe calls th· · f . I d d h ts umon o two nva trad1ttons a democratic para- ox an t e reason why the h· t f t·b 1 ts ory o 1 era democracy has always been full

Liberal Democracy and Free Speech 7

d r · 1 lity and popular saver- democratic tradition represente po ttica. 1' . hts and liberty eignty while the liberal tradition stood for 10 tvt ua s ng Th f limitation on state power. e to he guaranteed as a consequence o . f I based . · the exerctse o popu ar latter imposed restncttons on f diti" ns that according to . Th . t nee o two tra o ' on political equahty. e exts e 1 . d d 'both perfect liberty b m tl rationa tze rna e her, could never e pe ec ssible' (Mouffe 2000, p. 10). Liberal and perfect equality become tmpo d . ti"ally a paradox that . M « • wor s 1s essen · democracy, hence, m ourre s '

1 · · ti" t nsions within it. resu ts m persts ng e ·nts out to such per-

, . . f l"beral democracy pot

Carl Schmttt s cntique 0 1 h . . e oflt"beral democracies, . . d c"ng is cnttqu sisting tensions. Schmttt m a 1 nta democracies, wrote that libwhich he referred to as the parhame ry .ty (Schmitt 1926). Prior k .th rt ·n homogenet eral democracies wor wt ce at . th d ocratic tradition had to the emergence of liberal democractes, only for those who worked on the principle of substantivthe equalt d d others For Schmitt, h · d e occ u e · were equals. 12 The ot ers remame a liberal idea and not

I d "t their status was equality of all mdivtdua s espt e th . dividualistic ethics of "b t· t lked about e m a democratic one. Lt era Jsm a ·es as Schmitt writes, are h d m democract , equality of all persons. T e mo 6 IJ) that claim the equality 'a confused combination of both ( 192 'p.l the homogenised equals. 1 "ghts to on Y of all persons but grant equa n h ry person is automatically Th f I. b ]"eves t at eve e liberal idea o equa tty e 1 ti"c conception of equality, The democra , equal to every other person. who belong to the 'demos however, distinguishes between those t about the inequality "t The argumen and those who are exterior to 1 • • endance as one of the b d th uals gatns asc etween the equals an e uneq th" k focuses upon. d .l d . that ts wor . t emmas of liberal emocractes f the liberal democratic fi th emergence o . While this holds true or e ld the liberal democrattc . . . fi th t of the wor tradttton m the west, or e res . . l of liberal democracy idea travelled through colonialism. The prmctp es d uallty have persisted. See of struggles as the tensions between liberty an eq

Mouffe 2000. f tradition in Europe 12 David Held opined the same about the democra 1\ to this tradition th "b I d cracy. He re.ers at pre-dated the emergence of h era emo d th Athenian society. h · ·t base on e as t e Classical model of democracy, pnman Y

See Held 1987, p. 23.

were truncated by the colonial state in terms of the denial of liberal rights, which otherwise universally belonged to all individuals. The idea of colony was that of an exception to the universal, conditioned upon the 'differences' with its colonizers, not yet capable of exercising the right to liberty otherwise presented as a universal norm (Chatterjee 1993, p. 18). Despite the denial of the basic principles of liberalism by the colonial state, the idea of modern state that it represented was implanted, which was later appropriated by postcolonial societies to strive for the same liberal democratic state whose model was showcased by colonialism (Kaviraj 2003). While this proves to be an important historical digression for an analysis of the concept of liberal democracy, it is politic to return to the context which saw the birth of the idea of liberal democracy, the west. For the postcolonial world, the mimesis of liberal democracy created further dilemmas that this work would explore.

What eventually emerged as the liberal democratic form of government, as discussed earlier, premised itself upon the right to liberty of individuals. Despite the contradictions that persisted in realizing the universal equality of all individuals in exercising their liberty, the individual's right to liberty formed the core of the idea of liberal democracy. One of the essentials of the right to liberty is the freedom to express onesel£ The historical route, as well as the theoretical models, establish the centrality of the right to freedom of expression of individuals, within a liberal democratic state. Aligned to this proposition, is the question-why is free speech valuable within this framework?

The Value of Free Speech and the Category of 'Extreme Speech'

The value of free speech has been recognized in western liberal discourse both for its normative as well as instrumentalist presence. The defence of free speech within liberal democracy follows many strands within which the right to free expression against the authorIty IS read as an implied right.

While tracing the historical emergence of democratic forms of governments, Macpherson referred to developmental democracy as a variant of liberal democracy guaranteeing effective freedom and an equal right to self-government for all (1977, pp. 50-64). Developmental

idea of liberal democracy that went back democracy was a normative h' k On Liberty Mill stated f J h St art Mill In IS wor ' ' d to the writings o · o n u · t that those who governe h h form of governmen f that it was wit t IS new th lers-external to the class o ·fied ·th ople rather an ru d d were identi WI pe Th h governed were electe an subjects over whom they ruled. hoselwtod them The people retained h Ple w o e ec e . f If hence responsible to t e peo d h This was the age o seh 1 ho goveme t em. power over t e ru ers w . h' h th tyranny of the government d him m w IC e · government accor mg to ' . k dd however, that even m f ·t H was qutc to a ' ill was not the greatest o evi s. e 1 did not always represent the w the age of self-government, the ru ers th rule of each by himself asn't always e ft th of all and self-government w .11 of the people, more o en an What prevailed in the name of the W1M'll the tyrannY of majority was not was the will of the majority. For I f the government. Thus, for a a g;eater evil compared to the tyranny o ·oritarian will, he proposed society to be truly free from the each individual: first, the th st be exerctse t three basic liberties at mu d freedom to pursue tas es d di ssion· secon ' b . freedom of thought an scu dt fr dom to unite without emg that do not harm others; and lastly, eh ee on others. It would be read 'th · flicting arm uld h forced to do so and WI out 10 f liberal democracy wo ave along that for him, a genuine fonndo t individuals (Mill1999, PP· , h ki ds of free oms o d th . ht guaranteed these t ree n . lib rties he prioritize e ng f th e baste e ' 45-57). In the category 0 es . to freedom of thought and discusst:· ht and discussion shows why Mill's advocacy of freedom of oug. ty for its usefulness. Within b ted in a socte b d the free speech must e protec . th advocacy was ase on the framework of Mill's . ety 13 Mill was of the opinion 'l'ty 1n socte · kn idea of free speech being a utt 1 . bl' atory for the society, to ow 'tytSO tg f rt' that freedom of speech in socte tion that truth o ce am d the assumP 11 d t be the truth. His theory reste on . d n1 if they are a owe 0 beliefs or judgments can be determtn.: He based his argument debated and deliberated upon freely 1 p

like pleasure, happiness, d · arious ways · k \ike 13 UtUity could be interprete In v f the utilitarian thin ers · the thoughts 0 d d the prin- economic wellbeing, and so on, Utilitarianism expan e Bentham and James Mill. J.S. Mill 10 his book to certain ends but was tn ciple of utility saying that utility was not a ted that utility is desired In a itself Thus, the principle of utility 1998, p. 82. society as it results in general happtness.

upon two hypotheses, first, that the opinion which is being suppressed in society is possibly true and its suppression denies truth to the society, and second, he propounded, it may be probable that the opinion is false, in which case its expression would make its falsity known to the world and there would be no need for its constant denial (Mill 1999, pp. 59-60). Search for truth enhanced the utility in a society, eventually leading to the well-being of the entire society.

Seemingly, Mill's theory is a moral discourse on the objective idea of what constitutes the truth, and truth itself being a utility in the society. Mill's argument, however, has a lot to offer in terms of the consequences of conflicting opinions in society and the ways of dealing with them towards increasing the efficiency of a democratic government. Eric Barendt opined that Mill's argument about freedom of expression relates to the imperiousness of political opposition in a democracy. Only when the opposition has the right to freely challenge the actions of the government by judging them on parameters different from that of the ruling power can there be a possibility of appropriate action (Barendt 2005).

Mill's theory finds resonance in a similar argument defending free speech, which is the 'market place of ideas'. The reference to this argument is found in the United States Supreme Court verdict in Abrams v. United States, 14 1919. According to this argument, extreme ideas should he allowed to be circulated in the society in the hope that such arguments would be argued against and eventually rejected. Justice in landmark case in 1919 in USA outlined this idea while Issentmg With a majority decision in the court in case of a prosecution under the Espionage and Sedition Act 1917. Holmes' much quoted dis- sent note 'the b t f th . es test o tru Is the power of the thought to get itself accepted in the c · · f h k ' s f h ompetitron o t e mar et 1 is a classic application o t e theory that M'U h d ti th th 1 a propounded. It is of consequence to men- an at e argum t f ' k I l'b 1d c en ° mar etp ace of ideas' was also a typically 1 era e!ence of & h accorded hi h ri speec within a liberal democracy. The argument eren t d g P onty to free speech and interpreted freedom with ref- ce 0 Ynamism d b an enefits of a free market (Blasi 2004). Some

14 250 u.s. (1919).

IS Abrams v. United States, 250 U.S. (19I9).

Liberal Democracy and Free Speech II

h I pear to be attempts to bring of these defences of free speec a so ap ti' t dt'ti'ons ofliberalism b n the compe ng ra about a rapprochement etwee k I of ideas' is a liberal way of d Wh'l the 'mar etp ace and emocracy. 1e ether another argument offered holding liberalism and democracy b ' democratic way of doing by Alexander Meiklejohn appeare to e a

the same. d t of the First Amendment M 'kl . h as an a voca e

Alexander e1 eJO n w ld th 'ght to freedom of speech to the US Constitution that uphe e Speech and its Relation S . . He wrote n'f!e and expression to U Citizens. I f free speech in functioning of tl . · the roe o to Self-Govemment ou mmg a form of government 'kl . h democracy was a democracy. For Mel eJO n, d . order to self-govern people where people govern of electorate. Right to free must possess all information as f fio y ti'on and made democracy h . fr fl w o m orma speech ensured t IS ee 0 h 'ght to speak but the right t muc on n , vibrant. His focus was no so . ll kinds of views that the best to hear, as it was only after listenmgd freedom of speech does not judgment could be made. He argueth t eryone worth speaking shall h II k but a ev mean that everyone s a spea ' hi'slher views apoear to be b 'I d because · speak. No person shall e Sl ence believed that all political opinions conflicting, false, or dangerous. He h ted at the heart of the idea d b use t ey res deserved to be expresse eca h pie govern themselves, they thatw en peo of self-governance. It meant the content and the nature . dgment on II alone have the right to pass a JU ld be ensured only when a 1 Th1s cou ) of the speech and no one e se. d (Meiklejohn 1948, pp. 24-7 · kinds of thoughts are allowed to ?e has been an emphasis on proWithin the free speech scholarship, h'ch h s an important utilitarian . . I hl6 w 1 a d d tection given to pohttca speec t·ti· al speech is often wor e . for po 1 c b angle of defence. This protection h fi r self-governance (Gel er . e it as o In the language of the consequenc 2010, pp. 304-24). fi di free speech based on the . . · · de en ng d

Another maJor mtervention 10 d tic principles was rna e 11 on emocra Philosophy of liberalism as we as .J 0 .1 Fx:pression. This theory b 'T''h f Freeaom 'l . y Scanlon in his work A 1' 0 of liberalism that believed 10 Premised itself on the basic pnnctple

16 To categorize political speech as a or:m I of the ways of defining I th 'ty ts on Yone &ovemment, state, or the politica au on Political speech, which this work subscribes to.

[I of speech about or against the

individuals as rational beings capable of self-development, an argument that also lies at the heart of Mill's philosophy. According to Scanlon, the rationality of individuals makes them capable of self-governance, much on the lines of Meiklejohn's study. He says, an act of expression is any act that is intended by its agent to communicate to one or more persons some proposition or attitude which includes display of symbols as well as failures to display them (Scanlon 1972). In devising his theory, Scanlon talks about speech acts such as incitement, advocacy, conspiracy, and so on to commit certain actions that are likely to produce harm and defends them as acts protected under freedom of expression based on what he calls the 'Millian' principles, extending Mill's defence of freedom of thought and discussion.

The Millian principle recognizes the individuals as equal, autonomous and rational to the effect that individuals are 'sovereigns in deciding what to believe and in weighing competing reasons for their actions' (Scanlon 1972, p. 21 5). According to Scanlon the autonomy of the individuals enables them the power of judgments hence each individual is responsible for his/her actions. If the individual wa; incited to act a certain way, the responsibility of the act committed because of the incitement rested with the individual who acted upon it because he/ she had the autonomy to decide whether to act upon the incitement or not. In case the state exercises the right to protect people against false expressions by restricting those expressions in public space, it infringes ufon the autonomy of the individual as it does not concede the right 0 the individual to decide upon the consequences of the Free speech, hence, enables the exercise of autonomy.

nt.Greenawalt talks about the consequentialist and the non-con- sequenttalist 1·u t'fi . f ti . s t cat1ons o free speech. A consequentialist justifica- on constders pr t . f fi

t . 0 eCtion o ree speech an imperative, as it contributes o certam desirable st t f cc • I'k h of truth . d' . a e 0 alCatrs I e an onest government, discovery • tn tVtdual dev 1 d J·ustificat' lks e opment, an so on. A non-consequentialist ton ta about th . f fi someth' b e Imperative o ree speech in the sense that mg a out the · f its conseq practtce o free speech is right without regard to uences (Gr I value premt' f I'b eenawa t 1989). These justifications rest on the ses o 1 eralis h h that free speech b . m rat er t an the favourable consequences both kinds of . gs about. According to him, in a liberal democracu JUs t cation h ld th J• democracy r ts h s up 0 e value of free speech. A liberal es on t e cho. c f . . t es o ctttzens, and free speech ensures the

Liberal Democracy and Free Speech

13

h . b nabling informed decision- possibility of exercising those c mces y e f t· . 1 'd as th f Pression o po ttica t e . making and reducing e scope 0 sup fr d f olt'ti'b z· t lked about ee om 0 p John Rawls in his Political Lt era tsm a . h h . d' 'd al has an . l'b . on whtc eac 10 tvt u cal speech as part of basiC 1 erties up . · (R Is 1993 p. . . d t • eate a JUSt soctety aw , equal amount of clatm 10 or er o cr . . while making a staunch 340-48). Carole Pateman and Anne Plulhps, t lked about revif th · · I'b al democracy, a feminist critique o e eXIsting 1 edr c king sexual inequality a h . . . calle ,or rna sions within it. T e reviSIOn IS ld t 1 ·1 more substantial dd d d that wou en a concern to be a resse an 2012 . Philips 1993). They active participation of feminists (Patemanb h 'd in order to make a c h · ht f women to e ear essentially re1er to t e ng 0 cc t lks of creating a true . I t· . I d·a: nee Chantal Moune a . . substantia po ttica 1nere · . al pace to antagomstic liberal-democratic society that would give sf those voices within voices thereby upholding the right to expressiOn o .. d . ·17 a polity that are dissident an competing. the ri ht to free speech in a While considering the arguments about . d that the question · · t be borne m mm liberal democratic soctety, tt mus h . threat to its violation. . . h . ly when t ere ts a . of upholding th1s ng t anses on th kind of speech that ts No society would feel the need to suppress bile outlining his theory of · I Scanlon w e either pleasant or inconsequentta . d of expression becomes · d that free om freedom of expression mentione ches having harmful cona significant doctrine only when those speel talks about the minimal . . Kent Greenawa t _£ • sequences are 10 question. hould not intenere 10 . h th government s . . . h principle of ltberty t at says e h th commumcation m1g t t harm t at e communication unless to preven . s have been given many h c f express1on cause (1989, p. 10). Sue IOrms 0 h d so on. This work refers to tags such as harmful speech, hurt speec :an ;,., and Hare in their work ech Wemste... f these expressions as extreme spe · e speech as that form o d define extrem ) Extreme Speech an Democrac::' . of legitimate protest (2009, p. I · speech that goes beyond the limtts ch as a broad category of t me spee This work, however, treats ex re . . of any liberal democratic th t' e funct10nmg those expressions that e rou 10 The category of extreme c t h society finds discom1ort10g 0 f ressions like hate speec • . I d' ge o exp speech is diverse me u mg a ran

M ffe calls an agonistic model of 17 Such a society is based on ou democracy. See Mouffe 2000, PP· 9S--IOS.

pornography, libel, and so on. Sedition is also referred to as a category within extreme speech. Many argue that the centrality of right to free speech within liberalism is countenanced in a way that it provides space for extreme speech. Freedom of expression, as Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. said, is 'not free thought for those who agree with us but freedom for the thought of those we hate' (Soutphommasane 2006, p. 33). The defence of extreme speech, thus, also follows several strands of thought.

Sorial and Mackenzie talk about three kinds of defences for extreme speech (2011, pp. 165-88). The first argument is that the speech that urges violence is remote from actual occurrences of violence; hence, it is not a cause of direct harm. This argument, however, does not find much support even among the defenders of extreme speech, as it has been often argued that the harm is not always direct. Literature dealing with hate speech or pornography has mostly refuted this defence, arguing that the nature of harm does not always have to be physical and evident.

The second argument says that it is often difficult to distinguish between extreme speech and criticism of the government, hence, restriction on extreme speech many a times results in restriction on legitimate criticism of government as well. The third argument is about maturing of a democracy. It advocates that a mature democracy should be able to tolerate ideas expressed by extreme speech as it would have long-term consequences for democratic living. Both these arguments correspond to a democratic functioning where the values of democracy are accentuated to justify toleration of extreme speech. Defending extreme speech along the same lines, Ben Saul argued that unless we able to hear and understand the views of our political adversarIes, we cannot chan th · · d th h ge etr mm s at t ey are wrong or change our own behaviour to a da . . . ' 'gh ccommo te opposmg posttions that turn out to be : 1 t pp. 868-86). These defences of extreme speech argue 1 dcreating a deliberative sphere of adversarial political opinions. t era emocracies . d d l b th . are commttte to e i eration because it is one of e pnmary ways that

. . . th h h ensure ctttzen parttctpation and engagmg with ose w o old extrem . b (Sori 1 d M k . e VIews must e a part of deliberative process a an ac enz1e 2011, p. 169).

As per the deliberati d 1 f · legitimac f d ve mo e o democracy, the rationality and yo emocracy can only be established if the decision making

. . l f llective deliberation among free and process in a pohty ts a resu t 0 co th h lity where all h . b sured only roug equa equal citizens. T ts can e . . h ts to question to inter'ty 'to tmttate speec ac ' , have the same opportum , nhabib 1996, P· 70). This is equally rogate, and to open debate. (Be h dit' ns that is based on his linked to Habermas' idea of tdeal speec tothat only those 'action . . 1 Habermas wn es notion of discourse pnnclp e. h a: cted could agree as pard h . h l1 those w o are aue norms are vali tow tc a 1996 p 107-8). By 'action . 1 d' e' (Haberrnas • · ticipants in rattona tscours . th behaviour of people and norms' he means general rules governhmg . te rest could be affected by d , h those w ose m e by those 'affecte e means . Rational discourse for him . f th actlon norms. the general practtce o ose . d t achieving an understandis a process by which an attempt IS rna ati'on Hence the process of h h commumca . , ing over action norms t roug . ld be considered valid only « . 1 w making wou rational discourse anecting a - ££ ted and since laws affect . . . . f all who are anec • tf it has the partictpatton ° . . t'on of all. Habermas does ld the partiCtpa 1 all, the process wou requtre . . ti' arrive at a consensus. The th h PartiCtpa ng not mean that all ose w 0 are . ·f th who are not agreeing get ki · valtd 1 ose d process of decision-rna ng ts . their opinions and are trie 11 d freely votce an opportunity to equa Yan hy a certain decision must to be convinced by those who agree the conditions of ideal be taken. This is another way of saymg onsequence of the rational l·d and are a c speech ensure that laws are va t discourse. h in democracy, the common

In all these arguments defending speefc mmon good or good of the f . idea o co h running thread is that o a certam 1 tion of extreme speec · d through to era society that can be promote . . blic debate that extreme f 'button to pu ld There is a certain logic o . . d that extreme speech shou ideas can make, if tolerated. It tS tmplie£ 'ts democratic utility, either h but10r1 not be protected as extreme speec ' dt's idea of shielding away from going by Mill's truth argument or Bren d . £ rm of words have lesser elease tn IO

Violence as discontentment once r h N ssbaum talks of the same . . . 1 e Mart a u h th possibility of erupting m v1o enc · b'l'ties approach, w ere e defence of free speech through her capa h 1 1 onditions to all citizens · t enable t e c argument is that, lawgtverS mus 1 .£ The prominence given to t d d · f human ne. · · owar s a goo conceptton o . bout the constitutive f h . fr e IS hence a reedom of speech within t ts am l bt'lt'ties (Gelber 2010, . f . di ·dua capa role of speech in formation o m Vl p.315).

Soria] and Mackenzie opine that there has to be considerable difference between extreme speech with a purpose to affect the public sphere positively and extreme speech which intends to propose resolution of issues in public sphere through violence (2011, pp. 175-6). Though there are always contingencies attached to allowing extreme ideas to be circulated in public, as the consequence may turn out to be violent, however, the unintended consequences are not to be the basis of judgment. Their logic is that even if there is propagation of tile politics or goals of a so called terrorist organization, that must be allowed to be heard as that would help the society make better sense of the act of violence resorted to and also the nature of deprivation and oppression that may have resulted in such acts. But this does not mean that the propagation of a violent act, urging people to take up arms, should be allowed. This is based on the logic that propagation · of extreme ideas about violence may contribute towards culling out the truth in society and help in rational decision-making. But the same ideas in form of incitement to violence do not serve the same purpose hence should not be protected. IS

The above argument offers a ground saying tllat there will be instances of expression of extreme ideas resulting in violence in society. If the ideas, however, were expressed independent of an intention to result in violence then the undesired consequence must be tolerated for the goodness of the intention with which the idea was expressed. This line of reasoning concludes that if the speech in question cannot he used to justify its contribution to the betterment of society then it should not to he protected. The argument about societal good being tllrough free speech also contains, within itself, the possibilIty of a counter argument. If the purpose of speech is to contribute positively to a society, when a speech affects a society deleteriously or certain sections of the same, it ought to he restricted. This argument has been advanced by many scholars on hate speech specifically. 19

• 18 kinSorial and Mackenzie, while giving the above argument defending certam ds of extr h d . 1. erne speec an not defending the others, say that this logic 1S app 1cable for th · · h h th ose soc1et1es t at ave a functioning liberal democracy. For 0 er Circumstances ho d 19 wever, a vocacy to violence might be tolerated. Gelber uses Nussbaum's argument to revert it to say that if hate sGpelebc 2 ° 0 es not enhance the individual's capabilities, it must be prohibited See e er IO,p.318. ·

. used b a speech, there have been stud-

On the question of to predict the reception of a ies that have proved that It IS d' n the hearer speaker and h . h nge depen mg upo ' h speec as meanmgs c a t ffected by the same speec .,0 H h ay people may ge a context.- ence, t e w . different. These studies have h 11 be the targets, IS even though t ey may a h . question is not always the 'b. the speec m f suggested that proscn mg . d education on the lines o ·t bl . fact persuasion an best remedy avat a e, m nas impact the aggressor th et group as we toleration help protect e targ (Weinstein and Hare 2009, P·. lOS). the causal connection between the

The question about how tightly h been one of the most pro« be drawn, as 09 speech and 1ts enects can . . f free speech (Post 20 , P· nounced defences against proscnption tlo requirement of proving the t how severe le f h 134). In any case, no mater h . de the contingency o t e d b speec IS ma , conjectural harm cause Y a ·th 1 . most likely that a speech not b d ay WI • tIS argument cannot e one aw h ful occurrence to follow may h

t for any arm th · having enoug mcttemen h having met all e requireresult in the unanticipated, and a speec fa harmful speech may not . h parameters o ments of proscriptiOn on t e . the question that emerges . A . t these dilemmas, result in any act1on. gams is what can words do?

h A Reconsidered

Sedition as a Speec ct, f which sedition is a f treme speech, o When we focus on the fate 0 ex minence. If speeches can f h assume pro h kind the consequences o speec . the meanings that speec es , theonze h · mean harm it is of our concem to b t consequences. The P I' . bring a ou . contain and how these meamngs . . and while domg so, the 1 h theonzatlon ed F losophy of language he ps t IS . ds to be complicat · or h d acttons nee · I 1 distinction between speec an h act theory is parocu ar Y , k the speec th . this purpose J.L. Austin s wor on d f the speech act eory IS ' b maeo (Btl helpful The assertion that can e on its addressees u er . . . . us impact up that language can have an 10JUf1°

. . theory approach, studied . muolcation h

2.0 Leets and Giles, through therr com the impact of racial speec d ·gns to see d' th t three different experimental case esl . ll thereby conclu mg a h d ·II t results 10 a ' · t on people and came up wit 111 eren ps and proscription 15 no • 11 target grou the attribution of harm is different 10 a 997 1 S L ts nd Giles 1 · a ways what is required. ee ee 3

1997, p. 16). Austin in his work, How to Do Things with Words, talks about three ways in which speech and action are related; firstly, saying something is to do something; secondly, in saying something we do something; and thirdly, by saying something we do something (Austin 1962, p. 108).

The study of speech act signifies that language performs action, hence the distinction between language and action does not exist. Searle, in Philosophy of Language, says that speaking a language is performing speech acts, such as making statements, giving commands, referring, predicating, and so on (Searle 1969, p. 16-9). Speech act, to put it simply, is the act performed in the utterance. The utterance may or may not be verbal, could be symbolic, just as speech is also a nonverbal form of communication. The study of speech act is the study of the symbols produced in the utterance, imperative to understanding the intention and the purpose of both the utterer and the utterance. According to Searle, this kind of study of theory of language is necessarily the study of theory of action.

Austin explains speech acts as having two kinds of effects-illocutionary and perlocutionary. An illocutionary act is the performance of an act in saying something rather than performance of an act of saying something (1962, p. 99). This means that an utterance has already produced an effect while being performed. This effect is called the illocutionary effect. A perlocutionary act is that which is produced as a consequence of saying something. Such an act results in a perlocutionary effect, which the audience of an utterance feels consequently. It is the actual effect of the speech act whether intended or not by the utterer (Austin 1962, p. 101). The basic difference between the two is that in case of an illocutionary act the speech itself constitutes an act while in case of perlocutionary act, the act is the consequence of the speech. For example, in a Christian wedding, if a couple pronounces 'I do' in front of a priest, that speech has an illocutionary effect as the act of marriage is solemnized in saying what they said. Example of a perlocutionary act would be the act of convincing. An utterance or speech that is making a statement to convince someone does not constitute an act in saying but it may lead to an act as a consequence (if the audience is convinced).

Austin, however, says that the effect of the perlocutionary act is not always as intended by the utterer. The consequences of the speech

to the intentions of the utterer and resulting in an act may be contraryd' f the audience. An illocutionary h h ierstan tng 0 t ·s in accordance wit t e unc d c while perlocutionary ac 1 1 aning an torce th f act has a conventiona me . A ti supplements his eory 0 1 d · t rpret1ve. us n b bal non-conventiona an 10 e . d s not always have to e ver h nt that 1t oe · nd speech act with t e argume . con)·oins the illocuuonary a 8) h. ch sometunes f . . a (Austin 1962, p. 11 • w 1 h t For example, an acto nus10g perlocutionary effects of a :c .act of intimidation, at the same stick will constitute the ry ffect of deterring a person from time it may have the e 'llocutionary effect, raising the doing something. In the case o ltimidation while in the case of stick has a conventional meaning o 10 ay not be deterred. This may cc the person may or m t always be perlocutionary euect f speech act may no mean that the perlocutionary effect o ; dith Buder writes, that illocuproduced. Interpreting Austin's theory, ulapse of time as the speech act c f ns without any . ts proceed tionary acts penorm ac 10 7) The perlocutionary ac . itself constitutes action ( 1997• p. 1 · not be sequentially followmg. h t maY or maY k b ·nto the by way of consequences t a h ry this war pro es 1 ful

Drawing from the speech adct t .e: :nd thereby between harm b h an actto h t theory esta - relationship between speec The speec ac speech and the harm that it can injurious effects. Hence, the lishes that speech is capable of pro ucds to be revisited from the vanpeech nee h t blished that entire question of extreme 5 d Th ugh Austin as es a eli th gh wor s. 0 th h ve been stu es tage point of harm rou senses, ere a all all speech acts are conducts in narrow esulting in further acts, not 11 b · acts or r 'tion that a that argue that despite e10g cc Hence the propost th me euects. 11 rted speeches can produce e sa t be genera Yasse · . ful ffects canno c 1' 't us performattve words can mean harm e t of a 1e tCl o ffi

Judith Butler talks about the acts can \ which is based on the idea that not a rmative is that in w tc on their addressees. A felicitous perfo effect (Butler 1997, p. 17)h. roduces some . b tween speec speech that performs an act P h equivocatton e h Hence within the speech act theoryht ethe effectiveness of the sp:ec and is not the only debate t -un.i\e considering the 'barmal . 'gnt can . vvu . ·thin 1i er act in producing effect ts more 51 'ts restrictton Wl h d rm1ing ror 1 ry extreme argument of a speec an . a o-·· e that because . ld democracy, it is not suffictent to arguth t may be injunous, tt shou d .£arms acts a · ccount the speech is a conduct an pen• . . st take mto a b b restrtctton mu e proscribed. The de ate on

effectiveness of the extreme speech in performing acts that produce harmful effects.

Before we get into the nuances of determining the between speech and harm, it is imperative to understand the dtfferent ways in which sedition as a form of extreme speech/speech act can constitute the illocutionary and perlocutionary effects. As has been discussed above, the illocutionary act in saying something is constituted by force of convention. This implies that illocutionary utterances have conventional meanings-meanings that have a general acceptance. In deciding the illocutionary effect of the speech act, however, it is of utmost significance to see who the utterer is. For example, banging of a hammer by a judge in a court constitutes the act of silencing and disciplining the people in court but the same speech act performed by a lay person on the street may not have the same meaning. Sarah Sorial outlines three criteria for a speech act to take illocutionary force; first, the speaker/utterer must have the appropriate authority over a domain of audience who are the addressees of the speech act; second, the speaker must have an intention to constitute the act he/she tries to constitute through the speech; and third, the addressees must recognize the speaker's intention (2012, p. 95). It is also the fulfilment of these criteria that ensures the efficacy the speech has over the action it constitutes and the effect it produces.

For a seditious speech to have an illocutionary effect, and for it to be restricted within a liberal democracy, it must be assumed that the speech constitutes the act of violence/harm on its target. This work considers the possibility of a seditious speech act against the state to constitute illocutionary effect if-the speaker has authority over the domain in question, the intention to constitute the act, and the audience recognizes the intention. In such a scenario, would a seditious speech act having illocutionary force, constitute the act of violence against the state? This question reverberates through the chapters taking up an array of cases of sedition for scrutiny.

For a speech act to have perlocutionary force, it is the consequence of the act that needs to be weighed. Austin marked the specific characteristic of perlocutionary acts, that is, the consequences produced may or may not be intended. Butler in her work also reiterates the argument that speech acts have effects that we cannot predict. While arguing in context of hate speech she writes, while the speaker is responsible for

Liberal Democracy aud Free Speech 21

eech act can produce depends upon what she says, the effect that a S h S rial alternatively writes as whtch ara o the context of its utterance , . 12012 p. 172). Hence, any argu- f ' bl" ntext (Sona , d . t the criteria o ena mg co ds to be cautione agams . . peech act nee k ment towards restnctmg a s . I The following chapters ta e · · 1 f assessmg larm. h k using general pnne1p es 0 f the identity of t e spea er, . d" . the parameters o h b . f up cases of se ttton on d equentiality as t e asts o f . harm an cons the intention o causmg t ·n being injurious. determining the effectiveness of an ac t. b th a methodological and a d . . . speech act ts o th ffi

Constructing se ttton as a h . t ntion is to probe e o entheoretical question for this democracy for which the f d . . vtthm I era h sive connotation o se ltiOn ' . I It helps examine t e extreme cr ff, cuve too · f h t t speech act theory oners an e e f the potentiality o t e ac o speech in question on the the practice of the speech act produce harm while juxtaposmg tt Wlk p in the following chapters. h h studies ta en u on ground throug t e case

L .b a1 Democratic Logic d. · · hin the 1 er Placing Se ttlon Wlt h the distinction of extreme speec , . While considering the category erges on the bas1s of who f h acts em f between different classes 0 speec f particular kind o extreme their target is. Accordingly, the : takes shape. Sedition as a speech or the rationale for its. for the authorclass of extreme speech is restncted . of the state. One of the most ity of the government and the secunty rity discourse of the state ks lain the secu d ffence dominant framewor to exp ft n interprete as an ° d . · most o e f • ra is the 'reason of state'. Se ttton, . h" the 'reason o state paI · n wtt m d I against the state finds exp anatiO · . e of unrestricte panop Y • th exercts C I digm. Reason of state advocates with existential challenges. . ar of measures by the state when face • provides for considerations, J. Friedrich suggests that 'reasons _of;t:teinsure [that] the survival of Which exist 'whenever it is reqmred 0 1 responsible for it, no matter . d" · ua s "ty the state must be done by the 10 lVI h in their private capact as be tot em "d ti s are how repugnant such an act may 17). These const era ' decent and moral men' (Singh 20°7• P· h"ch aim at preservmg the h . ki · decisions w 1 owever, important m ta ng existence of the state. f t are normally understood as sta e . · · The considerations of the reason ° h e the state is facmg a cnsls . I d"tions w er ernerging out of exceptwna con 1

situation This calls for measures that are extraordinary or exceptional to address a crisis that is neither routine nor ordinary (Singh 2007, p. 17). This argument brings into play the distinction between routine and exception. Reason of state is a manifestation of an exceptional condition imperilling the existence of the state, the answer to which lies in an exceptional non-routine legal provision. 21 Liberal democracies have witnessed the enactment of sedition laws in response to an immediate crisis situation; however, in the course of history, these provisions have been extended beyond the exceptional situation leading to the regularization of these laws. Paradoxically, sedition laws emerge as measures for crisis situations; however, they are used as ordinary routine laws for ordinary times, thus complicating the defence of sedition laws based on the reason of state.

The idea of reason of state stems from the argument that it protects the state, hence protects those who reside within. The rights of people are the cost of the security they enjoy. When it comes to the context of liberal democracies, however, it has to be deduced whether the logic of 'reason of state' operates any differently, and in doing so, it is Foucault's work that assumes significance. Foucault traces the evolution of the concept of reason of state. The modern state, as it came to be recognized in the sixteenth and the seventeenth centuries, worked on the principle of reason of state understood differently from the times of the liberal democracies. Foucault treats liberal democracies as a phenomenon that saw emergence in the eighteenth century. According to Foucault, the sixteenth-century conception of the reason of state was essentially a 'conservative' idea that talked about identifying what is necessary and sufficient for the state to exist and maintain itself in its integrity. He emphasized that it was not a principle of the state's transformation, or even of its development but rather the perfecting of features and chara t · · h 1 . c ensttcs t at a ready constituted the state. In that sense, it was an Idea of conservation of the state and its maintenance. 22

21 u-· t s· d JJWa tngh explains the existence of extraordinary laws within Indian emocracy with inhe t d . . . d , , ren un emocrabc provtsiOns presente as emergent' and temporal' laws desig d dd ' Singh 2007 . ' ne to a ress crisis situations that are exceptional. See 22

_In his lecture, Foucault outlines while citing the views of Bacon those sttuattons that manifested th , f ' . e reason o state' in the sixteenth century. The situations were the occur f b 11 rences o re e IOn and sedition. Sedition was understood

. f son of state Foucault was clear In context of the considerations 0 rea ' . d not only when the state was that they were at work all the time an 'th bl" would . p 1 saying e repu tc warding off danger. Foucault cttes a azzo ' . e if it were d would have no continuanc not survive for a moment an . . d b n art of govern. t and ma1ntame Y a not revtewed at every momen 41 S lf- then ment assured by raison d'etat' ( 1978 • p. 3 ks)St: be able to becomes the logic on which the state wor : a e rt which Foucault d d This reqwres an a strengthen themselves an en ure. 377_8). It is rational calls 'Political Rationality' state perpetuation. knowledge that leads to the techntq . F cauit is not concerned . ccording to ou The logic of state perpetuatton a · wt"th the state and I Th only concern 1s with any general rule or aw. e f st t The entire argument . . . 11 d h eason o a e. Its exigencies, whtch IS ca e t e r th h rt of the fact that states b l · t· ested at e ea a out govemmenta rat10na tty r th th h nge 10 · context how. ·dWi eca ' should exist and were mamtame · ever, this rationality also changed. . the fact that now the . h l"b l d mocractes was What changed Wlt 1 era e . der the will of the sovd I. ·th subJects un rul:rs were no ea mg WI d with rights and interests' (Rose eretgn but with 'mdivtduals entroste ed the logic on which the state 2006, p. 149). This change also rnmental rationality. Colin operated meaning thereby, a change 10 gove It meant by governmenG d fi what Foucau ordon in attempting to e ne f th" king about the nature of t 1 · · • system o 10 a rat10nahty wrote, a way or . what governing is· what the practice of government (who can e forn1 of that bl f making som or. who is governed), capa e 0 ractitioners and to those upon thtnkable and practicable both to tts p 3) Within liberalism, with Whom it was practised' (Gordon 199 entity and the need the recognition of the individual as a ng th rights of the individual, of th t t protect e estate and the governmen ° d fr m that of its sixteenththe rationale of the reason of state change 0 "ty and conservation. . . d t state secun century logic which was hm1te 0 this changed context and Now, liberty was the condition of secunty 10 . the ·ruler in form of libels and relation to the rebellion of subjects agamst S d"tion and rebellion were dts d th ho govern. e 1 courses against the state an ose w th b"ects or discontentment cond· "th rty of e su J tttons emanating from et er pove frorn the rule. See Foucault 1978, PP· 348-52·

a violation of liberty would have actually meant not just violation of rights but ignorance about how to govern (Gordon 1991, P· 20) ·

Under these changed circumstances, the principle of reason of state demanding the submission of rights of individuals for the maintenance of the state by any means, negated the values of liberalism. wrote, 'the game of liberalism (was)-not interfering, allowing free movement, letting things follow their course; laissez-faire ... basically and fundamentally means acting so that reality develops, goes its way, and follows its own course .. .' (1978, p. 70). For this theoretical claim to take shape in reality, the governmental rationality had to operate through other means rather than direct physical force. 23 Foucault by no means argues that liberalism is all about individual liberty and minimalist state and does draw a distinction between the theoretical claims and existing realities (Gordon 1991, pp. 14-27). Studies on contemporary liberal democracies have shown that violence is integral to the working of the liberal democratic states despite its official denial. 24

For our purpose, however, it is imperative to interrogate these theoretical claims on which liberal democracies have been founded. If so, does this governmental rationality allow the curtailment of individual liberty for the sake of security of state? Is the concept of reason of state essentially anachronistic to the principles on which liberal democracies operate? Or is it the fact that the imperative of the state supersedes the other imperatives in a way that liberal democracies are left to be no exceptions in terms of upholding the liberal democratic rights?

This work addresses these explanations while probing into the theoretical defences of liberal democracies in retaining the law of sedition and whether this retention truncates the value premise of liberal democracy.

23 For Foucault, the answer lies in govemmentality, the art of governing. For the purpose of this work, however, the problematic is not governmentality but the fact whether the changed governmental rationality within liberal democracies help explain the existence of sedition as an offence.

24 Jinee Lokaneeta in her comparative work on US and Indian liberal democracies argues that these states continue to rely on excess violence as a mode of controlling and governing the modern societies and this reliance is conditioned by the vagaries within the law in defining the threshold of permissible violence. See Lokaneeta 2012.

Organization of the Book

h lationship between liberal democThis work is primarily about t e re . n with other liberal democ. I d' While companso ed racy and sedition m n ta. . 1 ture of historically situat d th are m t le na racies has been one, t: • 'b t the debates on the concept . nd contn ute o . illustrations to mtervene a E 1 d USA and Austraha to . h en are ng an , , . of sedition. The countnes c os b n the right to expresston h tussle etwee study a common aspect-t e . k b rrows from Tushnet's concept f d. · Thts wor 0 1 and the concept o se ttton. d f mparative constitutiona h. stu y o co ·f of normative umversahsm 10 ts . al (11ushnet 2008). So 1 . 1 s are umvers law, which says that certam va ue h . a universal value, it helps h . ht t free speec ts th th it is assumed that t c ng d different principles at e · · n 1t base on to assess the restncttons 0 ll . f d'cc t ountries fo ow. . 1 . t JUrisprudence o meren c . rticularities tn re ation o . ent certatn pa . The three countnes repres h ept of sedition owes tts . rk T e cone the central concern of thts wo · lib 1 democracies have been d t other era . genesis to English law an , mos eli . . England. England ts also 1 f se tton m f influenced by the Common aw 0 . h e abolished the offence 0 . l'b 1d ocractes to av . th one of the earhest 1 era em t liberal democracy tn e consedition. The US is seen as the stronges b t free speech jurisprudence. d 1 ed a ro us h l temporary world and has eve op . . l USA has retained t e aw f h prmctp es, 1. Despite the strongest ree speec h made one of the ear test l·b 1 d mocracy as b . . of sedition. Australian t era e l age of sedition to nng It d'fy the angu . and definitive attempts to mo 1 B 'des in recent times, parttcu1 . l tions. est ' . Within the counter-terror egts a f th ontemporary literature on larly between 2005 and 2010, most 0h e selected represent The t ree c ld h' h sedition is Australian literature. 1.· h developed wor w tc ld d rticular Y t e . r thi different parts of the wor an pa t of liberal democracy. It ts 1or . s has come to hegemonize the concep d' ase becomes interestlng, . . h the In tan c .reason that their companson wtt 1 . society shares the tmpres l . l deve optng where India being a postco onta ' . h h se countries. sion of being a liberal democracy wtt t he t r on four legal regimes, t've c ap e h t· .

The first chapter is a compara 1 d I dia dealing wit P0 ttl1. an n · 1 namely England USA, Austra ta, nalyses two particu ar , ' . . The chapter a h cat offences and speech cnmes. . . as an offence-first, t e h . of sed1t1on f r , d Paradigms to study t e ex1stence h sical act 0 torce an f • · 1 ce as a P Y h d ' conventional paradigm o v10 en f , · lence throug wor s · d' m o VlO second, the non-conventional para tg

Within the first paradigm, sedition is compared with the allied political offences of; (a) treason, (b) incitement to disaffection/violence/overthrow, and (c) political conspiracies. Within the second paradigm, sedition is compared with four speech crimes: (a) personal libel, (b) hate speech, (c) blasphemy, and (d) pornography. Both levels of comparison offer deductions about specificity of sedition as a political speech act creating a discord within the value framework of liberal democracies.

The second chapter leads to separate inquiries into the political history of the law of sedition in each of the three western democracies, based upon legislations, judicial trials, and targets of the law and its relationship with counter-terror legislations. In each country, there is one specific moment in relation to sedition that gains prominence through the course of study. The chapter offers a framework of three specific moments, namely, 'abolition', 'restriction', and 'modernization' that most aptly define the place of sedition in that particular country.

The third chapter is the first specific chapter on India. It discusses the idea of sedition from its inception within the legal code by the colonial regime and the different meanings that it acquired within colonial India. This chapter proposes that the idea of sedition within colonial India took shape within two different discourses-the judicial and the political. These two discourses are treated as two frameworks to look at the different meanings, deployments and the politics of sedition, through a detailed study of the use of the law and various trials related to it. Subsequently, it tries to see how the colonized subjects responded to the concept of sedition within the two discourses to conclude what sedition meant in colonial times. The focus of the chapter is on the early trials involving the nationalists and the emerging idea of sedition as political resistance. The colonial literature, available as part of archirecords, serves to he the most exhaustive source for constructing a htstory of sedition within colonial India.

. The fourth chapter traces the discourse on freedom of expression postcolonial idea, the security imperatives of the state, the political htstory of the law of sedition post-Independence and its journey within the courts. Through this, an attempt at conceptualizing public order of state and other grounds along which the act of sedition penaltzed is mad Th" h b . . h '. e. ts c apter egms wtth debates on sedition within t e Constituent A hi d . · h "gh ssem y an systemattcally takes these debates to the 1 er courts · 1 d" 1 . m n ta emp oymg legal hermeneutics to read into the

"ud ments and deduce a theory of sedition coming from_ the.judiciary. J g . I ments as contnbuting to the The chapter treats the judicta pronounce th . .d tify what emerges as e cnme study of sedition as a speech act to 1 en . h I I . ·d·cal regime in Indta. of sedition within t ega -JUfl 1 d tandin of sedition emerging

The fifth chapter JUXtaposes the f thg law on the ground. . d" . "th the practtce o e from the higher JU tctary Wl h" h 1 ks at sedition in its h · · ·1 field-based, w lC 00 T e chapter ts pnman Y . 1 d based on caste class . d . h the socta or er , , everydayness intertwme wtt d th h a study undertaken of d I d" It procee s roug an commumty tn n ta. h d Pun1·ab The regions f H Maharas tra, an · three specific regions o aryana, th erged as field areas folfi ld · · fact ey em are not chosen as e sttes, 10 '. h h "ntertwined dynamics of h d . whtc t e t lowing the case law met 0 10 1 d "t different character. This h . t· · 1 ariables en 1 a sedition wit soctopo ttica v . . ws and the attempts to . . f: t face 10tervte , included personal vtslts, ace 0 • . f th actors involved, both, at h I" d eaht1es o e partially experience t e tve r th . This has also involved the th . . nd 0 erwtse. e level of state institutions a h" s memorialization. They • f, to arc tves a process of archiv10g, re emng l f 1 ·maginations borrowing . d paces o ' are the creation of memones an d · 2003) 'Traces' brings , • (Appa urat · from Appadurai's idea of traces. di "d t·zed notion of traces, like h h . The 10 v1 ua 1 t e notion of w at rema10s. . . also forms a part of the d · agtnations, people's lived experiences an 1m everyday narratives of laws. merging in the working of th · the patterns e

The sixth chapter eonzes . ·fie themes along which . b .d tifytng specl the law of sedition in Indta Y 1 en ti"dian life of the law in the fi n the quo the law has been used. It ocuses 0 th wer oflaw enforcement. It h . ands of the state executives w orary times, its use agamst h f di · in contemP c ronicles various cases o se uon . . s communal politics, the d , rgamzatton , anti-nuclear movement, stu ents 0 Through these narratives, also dominant discourse of nation, and so on. . ·ngs and its identification . blic jmagtnt emerges the idea of sedition tn pu . l' deshdroh. It also theorizes . d , ti-nauona or . al Wtth what is loosely terme as an f clition and the exception th th . law o se e relationship between e rouune Th h the patterns identified, 1 roug or extraordinary counter-terror aws. d acy being characterized h . I di l"h ral emocr t ts chapter identifies the n an 1 e . the offence of sedition. by a 'moment of contradiction' in relation to ther the common and the The conclusion attempts to weave .tolge eech the offence of sedith · h olittCa sp 1 uncommon between e ng t to P th f ur countries. tion, and the liberal democratic frame of e 0

POLITICAL OFFENCES AND SPEECH CRIMES

Comparing Legal Regimes