https://ebookmass.com/product/saving-food-production-supply-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Sustainable Food Systems from Agriculture to Industry Improving Production and Processing Galanakis

https://ebookmass.com/product/sustainable-food-systems-fromagriculture-to-industry-improving-production-and-processing-galanakis/

ebookmass.com

Food Waste Recovery: Processing Technologies, Industrial Techniques, and Applications 2nd Edition Charis M. Galanakis

https://ebookmass.com/product/food-waste-recovery-processingtechnologies-industrial-techniques-and-applications-2nd-editioncharis-m-galanakis/

ebookmass.com

Food Quality and Shelf Life Charis M. Galanakis

https://ebookmass.com/product/food-quality-and-shelf-life-charis-mgalanakis/ ebookmass.com

Siegfried Kracauer, or, The Allegories of Improvisation: Critical Studies 1st

Edition Miguel Vedda

https://ebookmass.com/product/siegfried-kracauer-or-the-allegories-ofimprovisation-critical-studies-1st-edition-miguel-vedda/

ebookmass.com

Pegasus: The Story of the World's Most Dangerous Spyware

Laurent Richard

https://ebookmass.com/product/pegasus-the-story-of-the-worlds-mostdangerous-spyware-laurent-richard/

ebookmass.com

The Parasite and Other Tales of Terror Arthur Conan Doyle

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-parasite-and-other-tales-of-terrorarthur-conan-doyle/

ebookmass.com

Secret Lives Mark De Castrique

https://ebookmass.com/product/secret-lives-mark-de-castrique-5/

ebookmass.com

Mobility Patterns, Big Data and Transport Analytics: Tools and Applications for Modeling Constantinos Antoniou (Editor)

https://ebookmass.com/product/mobility-patterns-big-data-andtransport-analytics-tools-and-applications-for-modeling-constantinosantoniou-editor/

ebookmass.com

Sayings of Gorakhnath: Annotated Translation of the Gorakh

Bani Gordan Djurdjevic

https://ebookmass.com/product/sayings-of-gorakhnath-annotatedtranslation-of-the-gorakh-bani-gordan-djurdjevic/

ebookmass.com

Social Work Practice with Families A Resiliency-Based Approach 3rd Edition Mary Patricia Van Hook

https://ebookmass.com/product/social-work-practice-with-families-aresiliency-based-approach-3rd-edition-mary-patricia-van-hook/

ebookmass.com

SavingFood

Editedby

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier 125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom

Copyright©2019ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearance CenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher (otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroaden ourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingand usinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformation ormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhom theyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeany liabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceor otherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthe materialherein.

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

ISBN:978-0-12-815357-4

ForInformationonallAcademicPresspublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: CharlotteCockle

AcquisitionEditor: MeganBall

EditorialProjectManager: LauraOkidi

ProductionProjectManager: NileshKumarShah

CoverDesigner: MatthewLimbert

TypesetbyMPSLimited,Chennai,India

Listofcontributors

ElisabeteM.C.Alexandre QOPNA&LAQV-REQUIMTE,Departmentof Chemistry,UniversityofAveiro,Aveiro,Portugal;CenterforBiotechnologyand FineChemistry AssociatedLaboratory,SchoolofBiotechnology,Catholic UniversityofPortugal,Porto,Portugal

Vale ´ rieL.Almli SensoryandConsumerScienceDepartment,Nofima,A ˚ s, Norway

GracielaAlvarez RefrigerationProcessEngineeringResearchUnit,IRSTEA, Antony,France

JessicaAschemann-Witzel MAPPCentre,DepartmentofManagement,Aarhus SchoolofBusinessandSocialSciences,AarhusUniversity,Aarhus,Denmark

CarlaCaldeira EuropeanCommission,JointResearchCentre(JRC),Ispra,Italy

SaraCorrado EuropeanCommission,JointResearchCentre(JRC),Ispra,Italy

ChristineCostello AssistantProfessor,Industrial&ManufacturingSystems Engineering,UniversityofMissouri,Columbia,MO,UnitedStates

IlonaE.deHooge MarketingandConsumerBehaviourgroup,Wageningen University,Wageningen,TheNetherlands

HansDeSteur DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,FacultyofBiosciences Engineering,GhentUniversity,Ghent,Belgium

ManojK.Dora CollegeofBusiness,Arts&SocialSciences,BrunelBusiness School,BrunelUniversity,London,UnitedKingdom

GabrieldaSilvaFilipini FederalUniversityofRioGrande,SchoolofChemistry andFood,RioGrande,Brazil

XavierGellynck DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,FacultyofBiosciences Engineering,GhentUniversity,Ghent,Belgium

SelaleGlaue EfesVocationalSchool,DokuzEylulUniversity, ˙ Izmir,Turkey

NihanGogus EfesVocationalSchool,DokuzEylulUniversity, ˙ Izmir,Turkey

TizianoGomiero Independentscholar,Treviso,Italy

GangLiu SDULifeCycleEngineering,DepartmentofChemicalEngineering, Biotechnology,andEnvironmentalTechnology,UniversityofSouthernDenmark, Odense,Denmark

LaraManzocco DepartmentofAgricultural,Food,EnvironmentalandAnimal Sciences,UniversityofUdine,Udine,Italy

PaolaChavesMartins FederalUniversityofRioGrande,SchoolofChemistry andFood,RioGrande,Brazil

Vila ´ siaGuimara ˜ esMartins FederalUniversityofRioGrande,Schoolof ChemistryandFood,RioGrande,Brazil

UltanMcCarthy SchoolofScience&Computing,DepartmentofScience, WaterfordInstituteofTechnology,Waterford,Ireland

SamuelMercier DepartmentofElectricalEngineering,UniversityofSouth Florida,Tampa,FL,UnitedStates;DepartmentofChemicalandBiotechnological Engineering,Universite ´ deSherbrooke,Sherbrooke,QC,Canada

MartinMondor Saint-HyacintheResearchandDevelopmentCentre,Agriculture andAgri-FoodCanada,Saint-Hyacinthe,QC,Canada

Sı´lviaA.Moreira QOPNA&LAQV-REQUIMTE,DepartmentofChemistry, UniversityofAveiro,Aveiro,Portugal;CenterforBiotechnologyandFine Chemistry AssociatedLaboratory,SchoolofBiotechnology,CatholicUniversity ofPortugal,Porto,Portugal

SemihOtles FoodEngineeringDepartment,EgeUniversity, Izmir,Turkey

AdityaParmar NaturalResourcesInstitute,UniversityofGreenwich,London, UnitedKingdom

DarianPearce DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,FacultyofBiosciences Engineering,GhentUniversity,Ghent,Belgium

ManuelaPintado CenterforBiotechnologyandFineChemistry Associated Laboratory,SchoolofBiotechnology,CatholicUniversityofPortugal,Porto, Portugal

CarlosA.Pinto QOPNA&LAQV-REQUIMTE,DepartmentofChemistry, UniversityofAveiro,Aveiro,Portugal

StellaPlazzotta DepartmentofAgricultural,Food,EnvironmentalandAnimal Sciences,UniversityofUdine,Udine,Italy

VivianePatrı´ciaRomani FederalUniversityofRioGrande,SchoolofChemistry andFood,RioGrande,Brazil

SerenellaSala EuropeanCommission,JointResearchCentre(JRC),Ispra,Italy

JorgeA.Saraiva QOPNA&LAQV-REQUIMTE,DepartmentofChemistry, UniversityofAveiro,Aveiro,Portugal

TaijaSinkko EuropeanCommission,JointResearchCentre(JRC),Ispra,Italy

DespoudiStella AstonBusinessSchool,AstonUniversity,Birmingham,United Kingdom

SebnemTavman FoodEngineeringDepartment,EgeUniversity, Izmir,Turkey

IsmailUysal DepartmentofElectricalEngineering,UniversityofSouthFlorida, Tampa,FL,UnitedStates

SebastienVilleneuve Saint-HyacintheResearchandDevelopmentCentre, AgricultureandAgri-FoodCanada,Saint-Hyacinthe,QC,Canada

JoshuaWesana DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,FacultyofBiosciences Engineering,GhentUniversity,Ghent,Belgium;SchoolofAgriculturaland EnvironmentalSciences,MountainsoftheMoonUniversity,FortPortal,Uganda

LiXue InstituteofGeographicSciencesandNaturalResourcesResearch,Chinese AcademyofSciences,Beijing,P.R.China;SDULifeCycleEngineering, DepartmentofChemicalEngineering,Biotechnology,andEnvironmental Technology,UniversityofSouthernDenmark,Odense,Denmark;Universityof ChineseAcademyofSciences,Beijing,P.R.China

Preface

Aboutone-thirdofthefoodproducedintheworldforhumanconsumptiongetslost orwastedeveryyear.Thisquantityisshockingconsideringthatitaccountsapproximatelyfor1.3billiontonsoffood.Asitcanbeeasilyunderstood,theproblemof foodlossandwasteisdirectlyconnectedtohungerandglobalsustainabilityinthe 21stcentury.However,theproblemisevenbiggerthanitseems,asfoodlossalso accompaniesamajorsquanderingofresourcessuchaswater,land,energy,labor, andcapital.Inaddition,itisconnectedtoincreasedandunwantedgreenhousegas emissionsthatcontributetoglobalwarmingandclimatechange.Theproblemof foodlossandfoodwasteissobigthatitcannotbesolvedwithmereactivitiesor simplesuggestions.Itcanbeeliminatedonlybyfacingchallengesandproviding continuoussolutions,atalllevelsoffoodproductionandconsumptionforallthe involvedactorsandstakeholders.Correctingthepolicyframework,optimizingagriculturalpractices,shapingfoodproduction,changingconsumers’andcompanies’ attitudes,motivatingretailers,promotingpackagingandprocesstechnologies,valorizingwastestreams,andotheractionsshouldalsobetakenintoaccount.

Subsequently,aguidecoveringthelatestdevelopmentsinthisparticulardirectionisrequired.Thisbookfillsthesegapsbycoveringalltheaspectsoffood-loss reductionatallrelevantstagesandinallpossibleways.Itprovidesdetailsabout introducingsustainablefoodproduction,adaptingmoresustainablemethodsfor efficientcropcultivationandharvesting,optimizingutilizationofresources,eliminatinglossesinthesupplychain,adaptingsustainablepackagingsolutions,appealingenterprisestochangeconsumerbehavior,developingfoodwastevalorization strategies,andraisingpeople’sawarenessofwastedfood.Theultimategoalisto supportthescientificcommunity,policymakers,professionals,andenterprises,that aspiretosetupactionsandstrategies,toreducewastageoffood.Thereby,thebook targetsallinvolvedactorsandaimstodriveinnovations,promoteinterdisciplinary dialogues,andsparkdebatestogeneratesolutionsacrosstheentirevaluechain fromfieldtofork.

Itconsistsof13chapters.Chapter1providesanintroductiontoglobalfoodloss andfoodwasteusingdatafor84countriesand52individualyears.Chapter2 reviewssoilandcropmanagementpracticesthatmayreduceyieldloss,or increaseyields,whilereducingtheuseofinputsandtheenvironmentalimpactof agriculturalactivities.Anumberoffoodlossreductionmeasures(technicaland behavioral)areavailablealongtheentirevaluechain,butthemotivationtoimplementthemistheonethatneedsdueconsiderationandaction.Furtheroptimization ofagriculturalpracticestosavefoodisdescribedinChapter3.

Duringfoodproduction,transport,storage,andfinalconsumption,thefoodpropertiesmaygetaffectedinseveralways.Toensuresafetyandstabilityoffoodsand avoidtheirdischarge,effectiveandeconomicfoodpreservationmethodsshouldbe selected.Chapter4dealswiththeconventionalandemergingpreservation techniques,suchaspasteurization,sterilization,cooling,freezing,ohmicheating, microwave,andradiofrequency,whicharethermalpreservationtechnologies.On theotherhand,Chapter5dealswiththeapplicationofnonthermalandeco-friendly emergentprocessingmethodologiessuchashighpressureprocessing,pulsedelectricfields,andultrasounds.Thesemoderntechnologiesassureproducts’safetyas wellasmaintaintheiroriginalquality,thuscontributingtofoodlossreductionduringproduction.

Anefficientwaytopreservefoodisusingindustrialprocesses,butitisalso possibletouseactivepackagingtoextendtheshelflifeoffoodproducts.Tothis end,Chapter6discussesexistingandinnovativepackagingsolutionstominimize foodwaste.Chapter7reviewsthemainstagesandtechnologiesusedforthepreservationofperishablefoodproductsalongthesupplychain,andtheamountoffood lostorwastedalongthesestagesforthemainfamiliesofproducts.Italsohighlights theneedforbetterrefrigerationoffoodalongthelaststagesofthecoldchain(retail andconsumerhandling)andforbettermanagementalongthecommercialportion ofthecoldchainindevelopedcountries.Chapter8aimstoprovideanoverviewon lossesinthefoodindustry.Atfirst,foodlossesintheupstreamanddownstream supplychainarediscussedpriortodenotingthedifferentwaystoreducefood lossesbyoptimizingsupplychains.Solutionsatthesupplychainentity levelas wellassupplychainnetwork levelareprovided.Chapter9presentsmitigating approachesthatcouldbeinitiatedalongfoodsupplychains.Thisisconductedby discussingacasestudyofmeasuringfoodlossesinthesupplychainthroughvalue streammappinginthedairysectorinUganda.

Foodwastevalorizationincludesdifferentfoodwastemanagementstrategies, whosegoalistoturnfoodwasteintovalue-addedderivativestobeusedinfoodor otherindustrialsectors.Thesestrategiespresenttheadvantageofexploitingan always-availableandcheapsource,suchasfoodwaste,forproducingderivatives presentingahighpotentialmarketvalue.Chapter10,discussesthebasicdefinitions andprinciplesatthebasisoffoodwastevalorizationandpresentsrelevantstrategies,withparticularemphasisonthoseinwhichthegreatpotentialoffoodwasteis maximallyexploited.

InChapter11,theenvironmentalimpactsoffoodproductionandconsumption ofanaverageEuropeancitizenareassessedtakingthefoodwastegeneratedalong thefoodsupplychainintoaccount.Inaddition,theimpactoffoodwastereduction andadoptionofdifferentdietsareestimated.Chapter12discussesfoodwasteat theconsumer retailerinterface,theso-called“suboptimalfood”(reductionoffood lossesandwastesisoneoftheagriculturalresearchareas,thathasreceivedonly limitedresourcesandattentionfromthepublicandprivatesectorsincomparisonto increasedyieldsperhectare).Finally,Chapter13providesanintroductiontothe conceptsofZeroWasteandlife-cycleassessment;anoverviewofthechallenges presentedbytheUnitedStatesagriculturalsystemasitistoday;andadiscussion

onthefoodwastemanagementoptionsincludedintheEnvironmentalProtection Agency’sFoodRecoveryHierarchy.

Conclusively,thebookisaguideforfoodretailers,supplychainspecialists, foodscientists,foodtechnologists,foodengineers,professionals,agriculturalists, andfoodproducerstryingtominimizethefoodlossandadaptzerowastestrategies. Itprovidescriticalinformationinthisdirection,sothatthegeneralpubliccanbe aware,thegovernmentcansetrelevantguidelines,andfinallythefoodindustrycan optimizeproductionlines.Itprovidesanoverviewanddescriptionoftheproblem fromdifferentangles(e.g.,environmentalimpacts,somesocialandmanytechnologicalissues)andcoveringdifferentactors(consumers,producers,processors, industry,policymakers,etc.).Thiswayitcanhelpidentifycurrentresearchgaps andspurmorein-depthinvestigationsofcertaintopicsdescribedinthedifferent chapters.Itcouldbeofparticularinteresttofoodindustrystakeholdersasit highlightsstrategiesandtechnologiesthatcouldhelpmitigatefoodwaste. Knowledgeofbestpracticesandadvancedproceduresforthebalancedproduction ofagriculturalresourcesandfoods,andtheirredistribution,transportation,and consumptionwouldmakeitpossibletoachievesustainablefoodsystems.

Atthispoint,Iwouldliketoexpressmygratitudetoalltheauthorsofthebook fortheiracceptanceofmyinvitationandtheirparticipationinthiscollaborative bookthatbringstogether,forthefirsttime,differentscientific,technological,and managerialissuesofsavingfoodinonecomprehensivetext.Theyacceptedand followedtheeditorialguidelines,thebook’sconcept,andthetimelinewithultimate attention.Alltheseactionsconcludeinagreathonorformeandarehighlyappreciated.Iconsidermyselffortunatetohavehadtheopportunitytobringtogetherso manyexpertsfromBelgium,Brazil,Canada,China,Denmark,France,Italy, Ireland,Norway,Portugal,TheNetherlands,Turkey,Uganda,theUnitedKingdom, andUnitedStates.IwouldliketothanktheacquisitioneditorMeganBall,thebook managerKaterinaZaliva,andallElsevier’sproductionstafffortheirhelpduring theeditingandpublishingprocess.

IwouldalsoliketothanktheFoodWasteRecoveryGroup(www.foodwasterecovery.group)ofISEKIFoodAssociationanditspoolofexpertsthatprovidedus withvaluableinformationaboutdifferentwaysofsavingfood.

Lastbutnottheleast,amessageforallthereaders:Suchcollaborativeprojects ofhundredsofthousandsofwordsmaycontainafewerrorsandgaps.Anyinstructivecommentsorevencriticismsareandalwayswillbewelcome.Thus,neverhesitatetocontactmetodiscussanyissueswiththebook.

CharisM.Galanakis1,2

1FoodWasteRecoveryGroup,ISEKIFoodAssociation,Vienna, Austria, 2Research&InnovationDepartment,GalanakisLaboratories, Chania,Greece

Introductiontoglobalfoodlosses andfoodwaste

LiXue1,2,3 andGangLiu2

1

1InstituteofGeographicSciencesandNaturalResourcesResearch,ChineseAcademyof Sciences,Beijing,P.R.China, 2SDULifeCycleEngineering,DepartmentofChemical Engineering,Biotechnology,andEnvironmentalTechnology,UniversityofSouthern Denmark,Odense,Denmark, 3UniversityofChineseAcademyofSciences,Beijing,P.R. China

ChapterOutline

1.1Introduction1

1.2Systemdefinition4

1.2.1Foodlossesandfoodwaste4

1.2.2Foodsupplychain4

1.2.3Foodcommoditygroups5

1.2.4Geographicalandtemporalboundary5

1.3Foodlossesandfoodwastequantification6

1.3.1Bibliometricanalysisofliterature6

1.3.2Differentmethodsusedforfoodlossesandfoodwastequantification9

1.3.3Foodlossesandfoodwasteingeneral16

1.4Implicationsforfuture23

1.5Conclusions26 References26

1.1Introduction

Foodlossesandfoodwaste(FLW)occuralongthewholefoodsupplychain.In recentyears,FLWhasbecomeaglobalconcernandposesconsiderablechallenges tofoodsecurity(TheEconomistIntelligenceUnit,2014),naturalresources(FAO, 2013),environment(Katajajuurietal.,2012),andhumanhealth(Phametal., 2014),andisthereforeconsideredasakeyobstacletosustainabledevelopment. Therefore,reducingFLWhasbeenputonthepoliticalagendaattheglobaland nationallevels.Forinstance,theUnitedNationshassetatargetofhalvingpercapitaglobalfoodwasteattheretailandconsumerlevelsandreducingfoodlosses alongproductionandsupplychainsby2030,intheSustainableDevelopmentGoals (SDG)Target12.3(UnitedNations,2017).TheEuropeanUnion(European CommissionFoodSafetyHomePage,2017)hastakenactionstoworktowardsthis

target;in2015,theUnitedStates(UnitedStatesDepartmentofAgriculture,2017) alsoannounceditsfirst-evernationalgoaltoreducefoodwasteby50%by2030to improvefoodsecurityandprotectnaturalresources;andtheAfricanUnionalso madeacommitmenttohalvepostharvestlossesby2025inthe2014Malabo Declaration(Lipinskietal.,2016).

Overthepastfewdecades,withgrowingconcernsandattentiononFLWfrom publicandpoliticalsectors,moreandmorestudieshavequantifiedFLWacrossthe foodsupplychainatnational,regional,andglobalscales.Forexample,according totheFoodandAgricultureOrganization(FAO)oftheUnitedNations,aboutonethirdoffoodproductionwaslostorwastedworldwidethatwasmeantforhuman consumption(Gustavssonetal.,2011).ThissignificantamountofFLWwould mean4.4gigatonnesofCO2 equivalent(FAO,2015),250km3 ofbluewaterfootprint(FAO,2013),28%ofthetotalagriculturelandgloballyduringagricultureproduction,aneconomiccostofaboutUSD750billion(equivalenttothegross domesticproduct(GDP)ofTurkey)(FAO,2013),andapproximately24%ofall foodproducedwhenconvertedintocalories(Gustavssonetal.,2011).

ManyotherstudieshavealsorevealedasimilarscaleofFLWontheregionalor countrylevelanditssignificantimpactsonenvironment,economicdevelopment, andfoodsecurity.Forexample,itisreportedthattheEU-28generateabout100 milliontonnesofFLWeachyear,andthelargestcontributionisfromhouseholds (45%)(FUSIONS,2015).Forthememberstates,householdsintheUnited Kingdomwastedapproximately7.2milliontonnesoffoodin2012(WRAP,2014). ThewastedfoodfromhouseholdsinFinland,Denmark,Norway,andSwedenmake up30%,23%,20%,and10% 20%offoodpurchased,respectively(Gjerrisand Gaiani,2013).InSwitzerland,aboutone-thirdoffoodproduced(calorieequivalent) iswastedandhouseholdscontributethemost(Berettaetal.,2013).Someother developedcountriesalsohighlightasimilartrend.Forexample,intheUnited States,thepercapitaFLWincreasedbyabout50%between1979and2003(Hall etal.,2009).InAustralia,morethan4.2milliontonnesofFLWgoestolandfillper year(Vergheseetal.,2013).

Inthepastdecades,somegovernmentalorganizationsandnationalagencies havemadegreatefforttoquantifyFLW.Forexample,theFAOhasissuedanumberofrelevantreportsonFLWataglobalscale(Gustavssonetal.,2011;FAO, 2014).TheUnitedStatesDepartmentofAgricultureEconomicResearchService (USDA-ERS)developedtheLoss-AdjustedFoodAvailabilityDataSeriesin1997, whichcoversabout200itemsforthreestages(productiontoretail,retail,andconsumer)oflossesintermsofquantities,values,andcalories(Buzbyetal.,2009; BuzbyandGuthrie,2002).IntheUnitedKingdom,theWasteandResources ActionProgramme(WRAP)organizationhasbeensetuptoreducefoodwaste,and hasreleasedanumberofreportsonFLWinthefoodsupplychainsince2007 (WRAP,2008,2009).

Inrecentyears,relevantstakeholdersfromacademia,industry,andgovernmental andnongovernmentalorganizationshaveparticipatedinresearchprojectsand workedonthestandardizationofquantificationandmethodsofFLW.Forexample, theprojectFoodUseforSocialInnovationbyOptimizingWastePrevention

Strategies(FUSIONS)(2012 16)fundedbyEuropeanCommissionhasbeenworkingtowardsamoreresourceefficientEurope,andhasissuedanumberofreports, coveringtheframeworkofFLWdefinition,measurement,andmitigationstrategies (Ostergenetal.,2014;FUSIONS,2016).In2015,theEuropeanCommission fundedafurtherprojectcalledResourceEfficientFoodanddRinkfortheEntire SupplycHain(REFRESH)(2015 19),whichinvolves26partnersfrom12 EuropeancountriesandChinaandfocusesonthereductionofavoidablewasteand improvedvalorizationoffoodresources(RefreshHomePage,2017).In2016, WorldResourcesInstitute,UnitedNationsEnvironmentProgramme(UNEP), WorldBusinessCouncilforSustainableDevelopment,FAO,andWRAPtogether asapartnershipofmajorinternationalorganizationsannouncedthefirstglobalstandardtoquantifyFLW(WorldResourcesInstitute,2016).

ThoughtherearecontinuouseffortsonquantifyingFLWandsomeresearchers havealsostressedthedatadeficiencyandinconsistencyandraisedconcernsonthe demandofbettermeasurementofFLW(Parfitt,2013;Liu,2014;Shafiee-Joodand Cai,2016),therearestillmajorgapsintheexistingglobalFLWdataasfollows:

● Thespatialcoverageofexistingstudiesisnarrow.Mostresearchiscarriedoutindevelopedcountries.Forinstance,thereareplentyofpublicationsdrawingoutthesituationof FLWintheUnitedStates(Thybergetal.,2015;BuzbyandHyman,2012;Kantoretal., 1997)andSweden(Brautigametal.,2014;FilhoandKovaleva,2015).Incontrast,onlya fewstudiesquantifiedFLWindevelopingcountries,suchasNepal(Choudhury,2006) andthePhilippines(Parfittetal.,2010)andsomecountriesexperiencingarapiddevelopment,suchasChinaandIndia(ParfittandBarthel,2011).

● Thereisanunevenfocusonthedifferentfoodsupplystages.Agreatmanystudieshave illustratedfoodwasteatretailingandconsumptionstages(DaviesandKonisky,2000; Stenmarcketal.,2011;Parryetal.,2015),mainlyconductedindevelopedcountries,such astheUnitedStates.Ontheotherhand,therearefewstudiesrevealingthesituationof postharvestlosses,whicharemainlycarriedoutindevelopingcountries,suchasIndia (Gangwaretal.,2014).

● Someexistingdataareoutdatedbutstillinuse.Somestudieshavetodependontheolder dataduetothelackofupdatedones.Forexample,dataonthepostharvestlossesoffresh fruitsandvegetablesfromonestudyinthe1980sand1990swereusedintworecentstudies(Parfittetal.,2010;Kader,2005).

● Thereisalackofprimarydataandagreatmanystudieshavetocitedataintheexisting studies.Forexample,manyresearchershaverepeatedlyciteddatafromtheFAOreport issuedin2011(OelofseandNahman,2013;Lipinskietal.,2013;NahmananddeLange, 2013).Butitmaynotberepresentativeintermsoftimeandcountriesforcommodities (Liu,2014).ThedataprovidedbytheAfricanPostharvestLossInformationSystemhas beenmostlyusedtoaddresspostharvestlosses(Prusky,2011;WorldBank,2011;Segre ` etal.,2014).

● ThedefinitionofFLW,methodsused,andsystemboundariesaredifferentinexistingstudies.ThismakesitdifficulttosystematicallycompareandverifyFLWdatabetweencountries,commodities,andstages.Therefore,itisuncertaintodoanalysisontherelationship betweenFLWandsocial,economic,andenvironmentalfactorsbasedontheexistingdata.

Itisparticularofimportancetoclearlyandcomprehensivelyunderstandthe existingglobalFLWdataontheirqualityandavailability.First,itisaprerequisite

fortrackingtheprogresstowardtheSDGTarget12.3andthenationalFLWreductiongoals,andevaluatingtheeffectofrelevantpolicies.Second,itwillcontribute toraisingawareness,informingmitigationstrategies,andgivingprioritytoprevent andreduceFLW.Third,betterdatacanbeenverifiedandcomparedamongcountries,stages,andcommodities,helpingtodistinguishpatternsanddriversofFLW generated.Fourth,itcanbeanessentialfoundationforfurtheranalyzingthesocial, economic,andenvironmentalimpactsofFLW.

Inthischapter,acriticaloverviewofalltheavailableFLWdatain202publicationsisprovided,whichcouldprovideabasicdatabaseforfurtheranalysisofenvironmentalimpactsandmitigationstrategiesofFLW.Bibliometriccharacteristicsof existingliteratureandmethodsofmeasurement(advantagesanddisadvantages)are assessed,theirpatternsbetweencountries,foodsupplychainstages,andfoodcommoditiesarediscussed,andsomeimplicationsforfutureworkaredenoted.

1.2Systemdefinition

1.2.1Foodlossesandfoodwaste

FLWoccursacrossthefoodsupplychain.Somestudieshavemadeadifference betweenthedefinitionofFLW,edibleandinediblefoodwaste,avoidableand unavoidablefoodwaste.Forexample,accordingtotheFAO(FAO,2014),food lossreferstofoodthatislostduetoquantityorqualityreasons,andfoodwaste referstofoodthatislefttospoilorexpireduetocarelessnessofconsumers,which isusuallyrelatedtodiscardingdeliberatelyorotheruseoffood(e.g.,animalfeed). Becauseofthedeficiencyofconsistenciesintheliteraturereviewed,thedistinctionswerenotconsideredandwedonotdifferentiatebetweenfoodlossandfood wasteinthisstudy,sowedefineFLWasthecombinedamountofFLW.

1.2.2Foodsupplychain

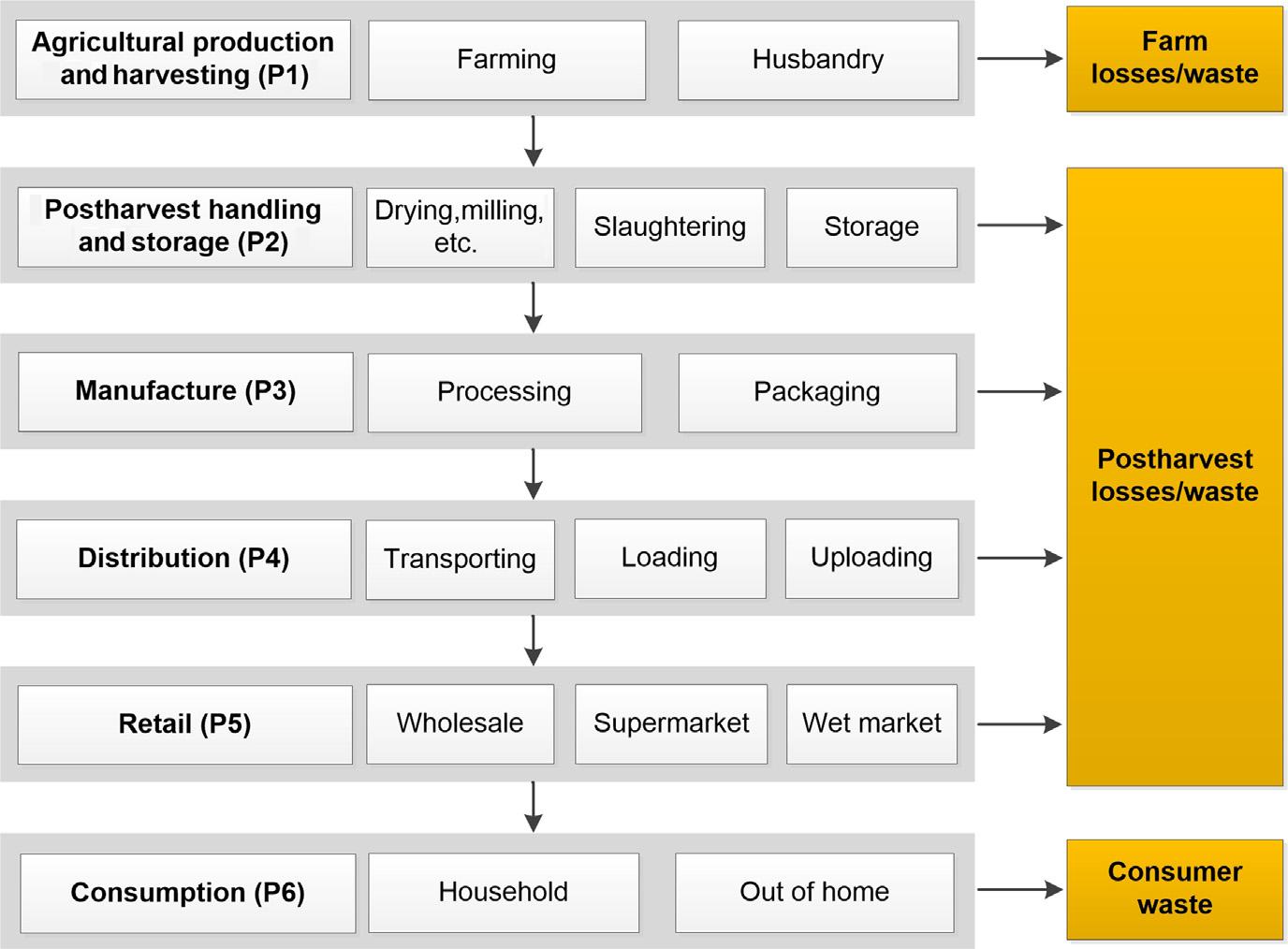

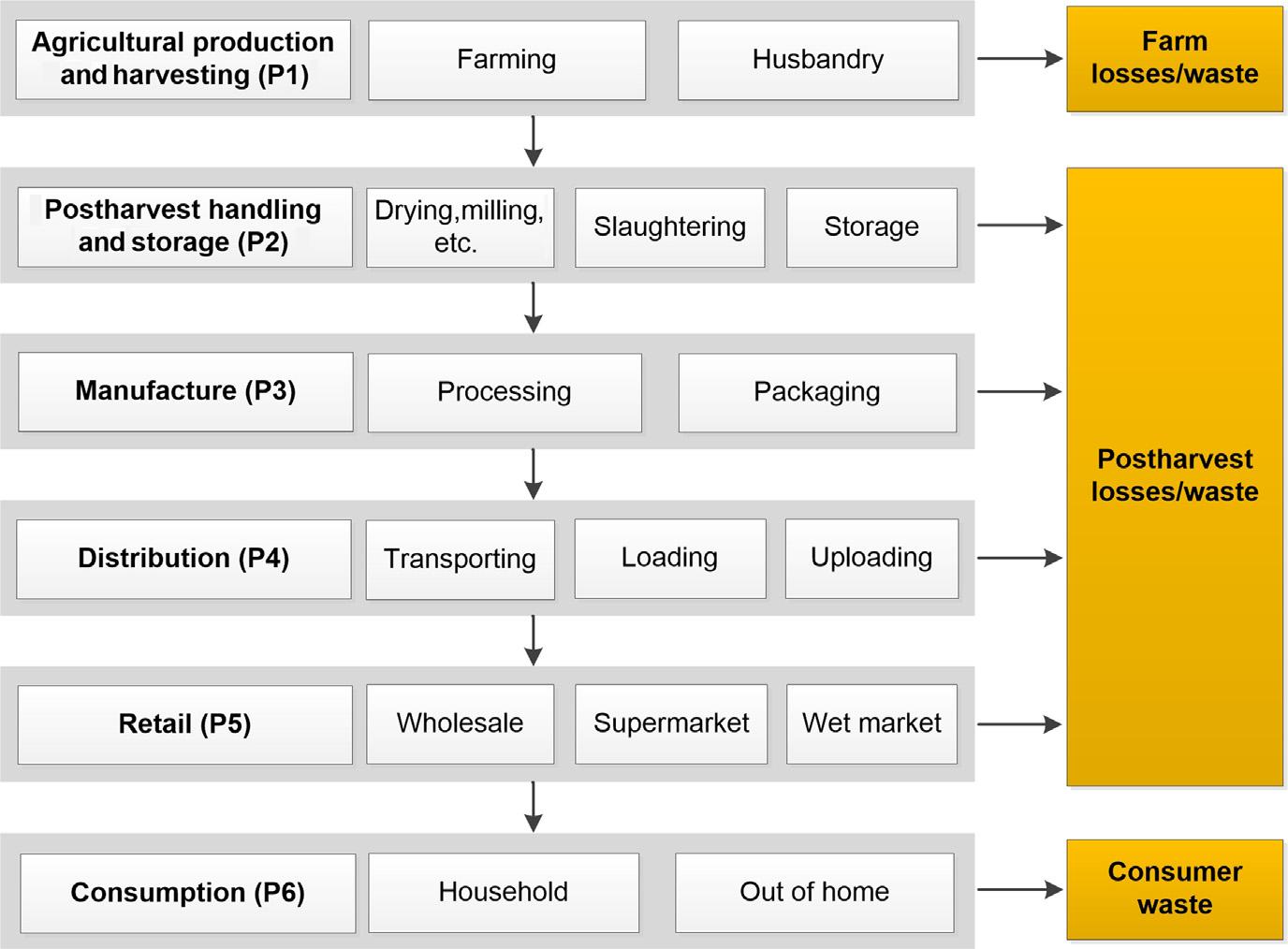

Asshownin Fig.1.1,FLWinvolvessixmajorprocesses.FLWcouldbefurther classifiedintothreetypes:farmlosses/waste(duringagriculturalproductionand harvesting),postharvestlosses/waste(duringpostharvesthandlingandstorage, manufacturing,distribution,andretailing),andconsumerwaste(bothinhousehold andout-of-home).Agriculturalproductslosses/wasteonthefarmaremainlycaused byinsects,diseases,andsevereweather.Forlivestockproducts,itrelatestosicknessanddeathduringbreedingstageforcattle,pig,andpoultrymeat,anddiscarded fishduringfishing.Postharvestlosses/wastereferstofoodspoilageanddegradation duringdifferentstages.Itincludespostharvesthandlingandstorage(whenfoodis underthreshing/shellingoricingandanimalstransportedtoslaughtering), manufacturing(whenfoodisprocessedintovariousproducts),distribution(when foodistransported,loaded,anduploaded),aswellasretailing(includeswholesale, supermarket,andwetmarket).Consumerfoodwasteoccursbothinhouseholdand diningoutawayfromhome.

Figure1.1 Foodsupplychainforfoodlossesandfoodwaste.

1.2.3Foodcommoditygroups

ThecommoditiescategoriesweredefinedbasedontheclassificationofFAOand bytakingconsiderationofcharacteristicsofdatainthepublications.Asaresult,10 groupsoffoodcommoditieswerepresented:

1. Cerealandcerealproducts(e.g.,wheat,maize,andrice);

2. Rootsandtubers(e.g.,potatoesandcassava);

3. Oilseedsandpulses(e.g.,peanutsandsoybeans);

4. Fruits;

5. Vegetables;

6. Meat;

7. Fishandseafood;

8. Dairyproducts; 9. Eggs; 10. Othersornotspecified.

1.2.4Geographicalandtemporalboundary

TheFLWdatawascollectedfromasearlyaspossibleto2015attheglobal, regional,andnationallevels.BasedonpercapitaGDPandtheclassificationprinciplesofFAO(Gustavssonetal.,2011),thecountriesaredividedintomedium/highincomecountriesandlow-incomecountries(Table1.1).

Table1.1 Groupingofdifferentdevelopmentlevelsofcountries

Medium/high-incomecountriesLow-incomecountries

ArmeniaLithuaniaAngolaMalaysia

AustraliaLuxembourgArgentinaMexico

AustriaMaltaBangladeshMyanmar

BelarusNetherlandsBeninNepal

BelgiumNewZealandBoliviaNigeria

BulgariaNorwayBrazilPakistan CanadaPolandCambodiaPeru ChinaPortugalCameroonPhilippines

CyprusRomaniaChileSaudiArabia

CzechRepublicRussiaColombiaSouthAfrica

DenmarkSingaporeCostaRicaSriLanka

EstoniaSlovakiaEgyptSwaziland

FinlandSloveniaEthiopiaTanzania FranceSouthKoreaGhanaThailand

GermanySpainIndiaTogo

GreeceSwedenIndonesiaTurkey

HungarySwitzerlandIranUganda

IrelandUnitedKingdomJamaicaVenezuela

ItalyUkraineKenyaVietnam

JapanUnitedStatesLaosZambia

LatviaMadagascarZimbabwe Malawi

1.3Foodlossesandfoodwastequantification

1.3.1Bibliometricanalysisofliterature

1.3.1.1Typeofpublications

WebofScienceandGoogleScholarwerethemainsourcefortheresearch,and reportsissuedbyresearchinstitutionsaswellasgovernmentalornongovernmental organizationswerealsocollectedtoensureawidercoverageofavailabledata. Finally,202publicationswerereviewed.Theyincludefivetypes:peer-reviewed journalarticles(53.5%),reports(35.6%),PhDandmaster’stheses(5.9%),conferenceproceedings(3.0%),andbookchapters(2.0%).Journalarticlesweredominant (108)inthereviewedpublications,whichwerepublishedin69differentjournals andcoveredawiderangeofsubjects.Intotal,approximately45%ofthemwere publishedinthetop10journals(Fig.1.2).Themajorityofthepublications outletswere WasteManagement, WasteManagement&Research, Resources, ConservationandRecycling, FoodPolicy,and JournalofCleanerProduction, representing15.7%,7.4%,5.6%,4.6%,and2.8%ofthetotalpublishedarticles, respectively.

Figure1.2 Thetop10journalsthatpublishesfoodlossandfoodwastedata.

1.3.1.2Temporaltrendforyearofpublicationsandestimation

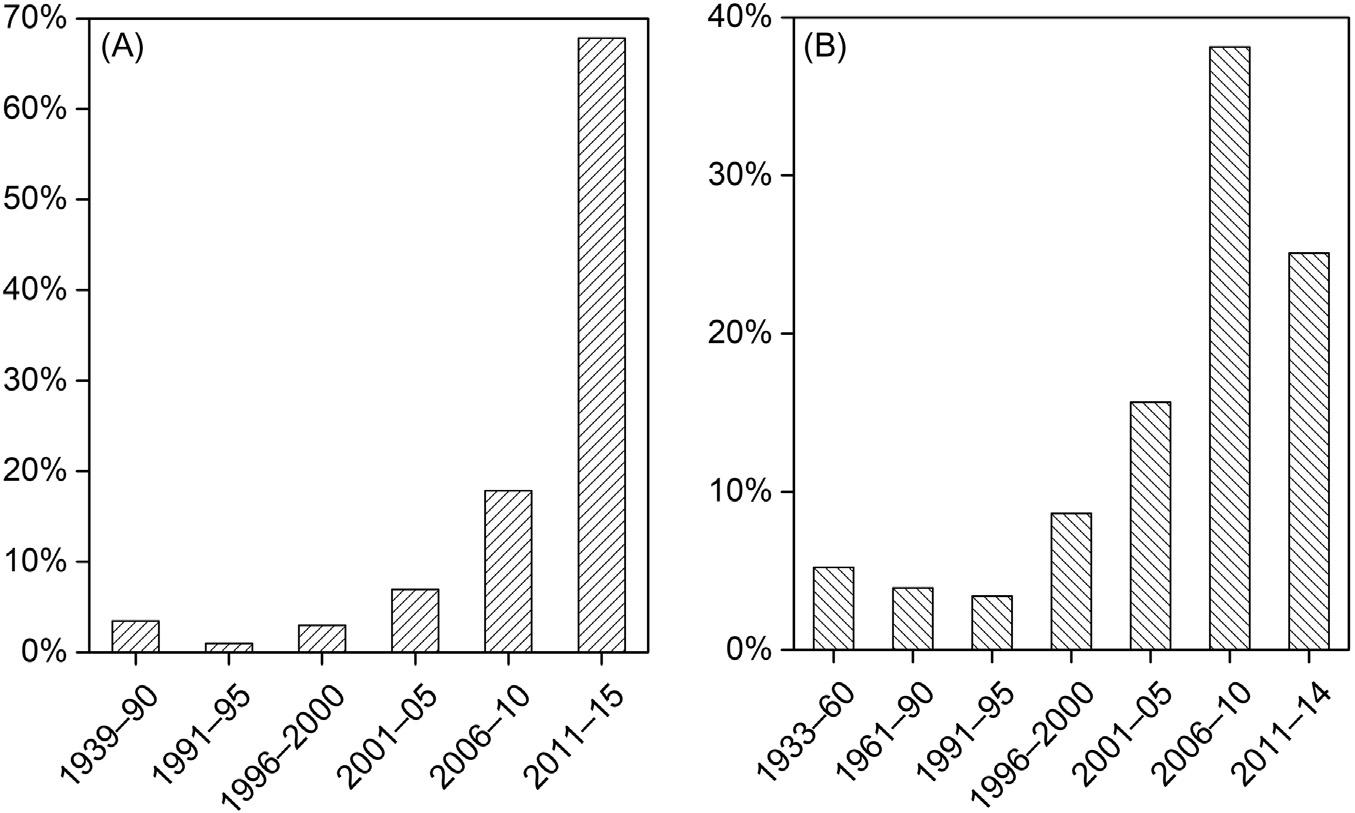

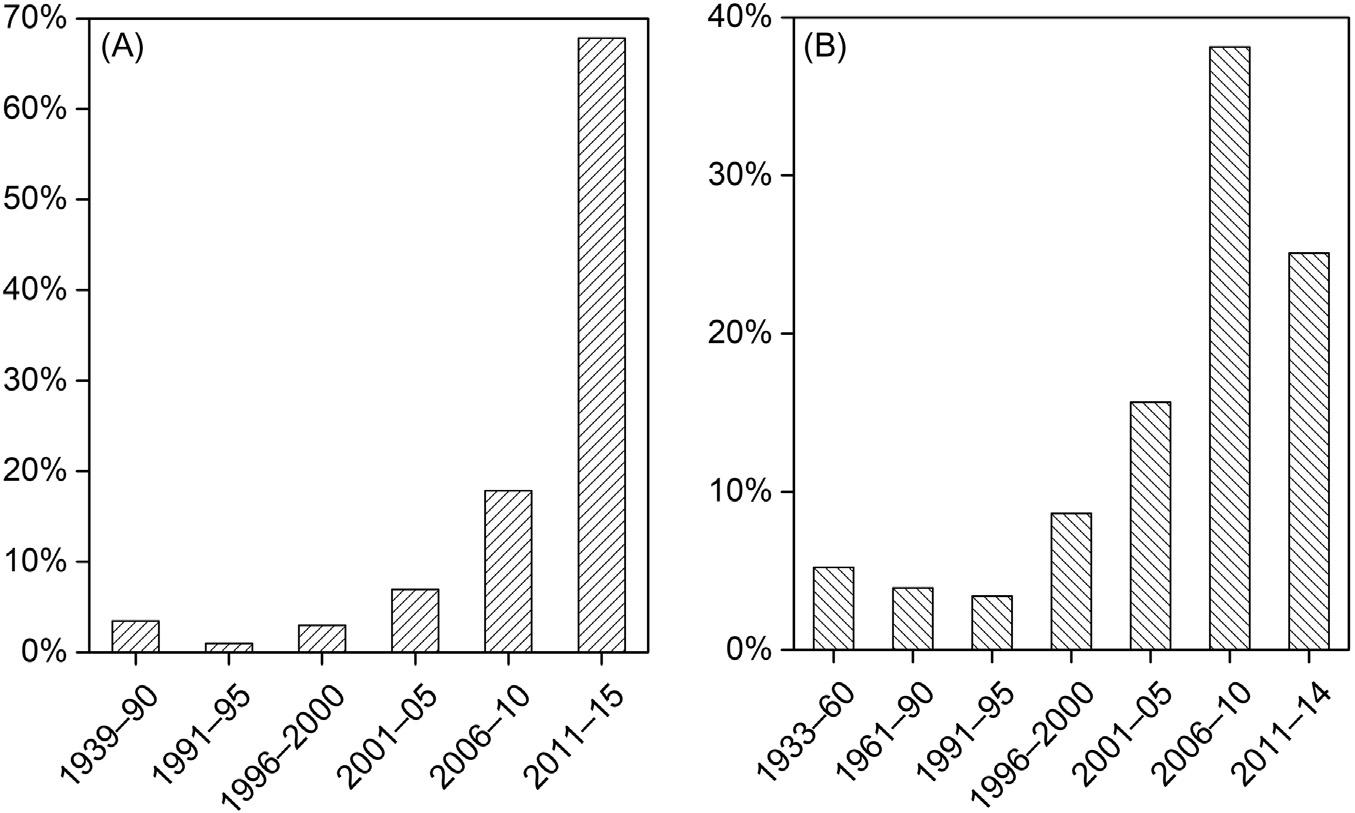

Fig.1.3A showsthenumberofpublicationsduringthe76-yearperiod(1939 2015). Ingeneral,thenumberofpublicationsi ncreasedthroughoutthewholeperiod.It wassmallandremainedstablebefore 2000.Afterwards,ithasseenagradual increaseduring2001 10.Inthelastfiveyears,thenumberofstudieshasgrown substantially(137),accountingfor67. 8%ofthetotalpublications.Thismeans thereisanincreasingfocusonFLWresearcharoundtheworld.

Fig.1.3B illustratesthetimetrendoftheyearofestimation.Accordingtoliterature, theFLWdatawasdiscoveredasearlyas1933,andthenumberremainedstableand lowuntil1995.Afterwards,thenumberhas increasedsignificantlybymorethan60% overthepast10years,38.1%from2006to2010and25.1%from2011to2014.

1.3.1.3Distributionofcountries

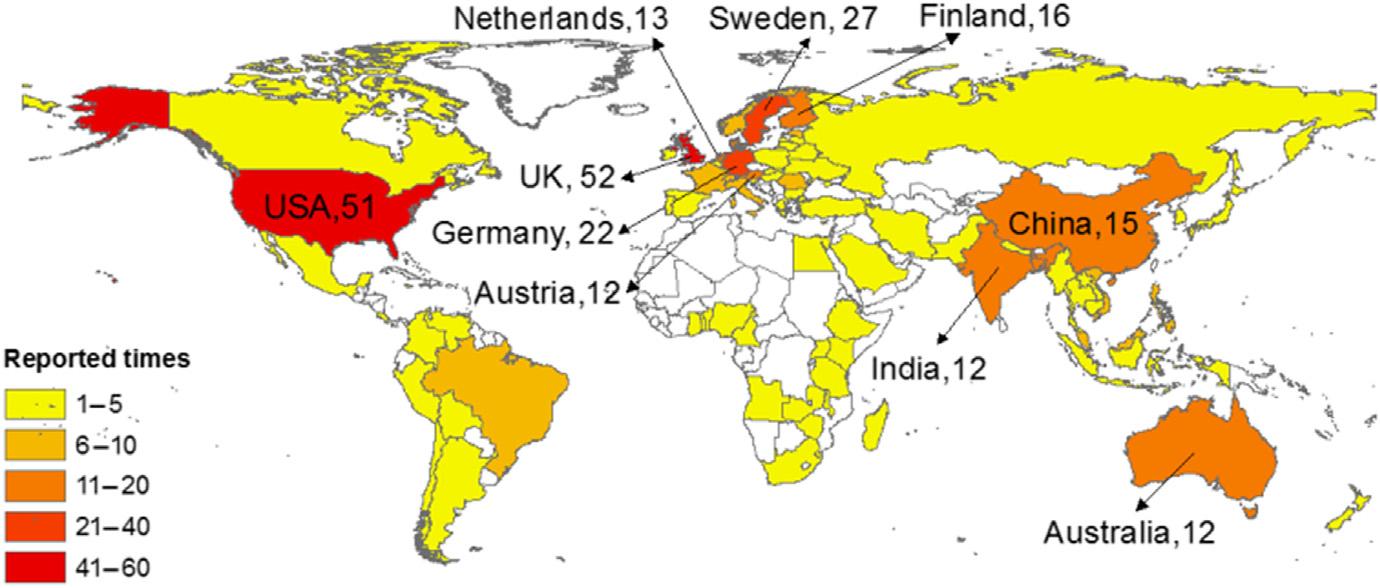

The202publicationsreportedFLWdatathroughoutthefoodsupplychaincovering 84countries(reported498times)distributedallovertheworld.However,thefocus onFLWwasunbalancedindifferentregions.Moststudieswereconductedinthe developedareas,suchasNorthAmerica,NorthernandWesternEurope,whereaslittle attentionwaspaidtothedevelopingcountries,suchasIndia. Fig.1.4 showsspatial distributionandthetop10countrieshavebeenstudied.Mostresearchwasconducted intheUnitedKingdom(Langleyetal.,2010;Menaetal.,2014;Vanhametal.,2015; Xuetal.,2015)andUnitedStates(Thybergetal.,2015;BuzbyandHyman,2012; Kantoretal.,1997),bothofwhichmadeupmorethan10%ofthereportedtimes, respectively.ThenSweden(Br ¨ autigametal.,2014;FilhoandKovaleva,2015), Germany(Kranertetal.,2012;Jorissenetal.,2015),andFinland(Silvennoinenetal., 2012;Silvennoinenetal.,2015)accountedfor5.4%,4.4%,and3.2%,respectively.

Figure1.3 (A)Temporaltrendofreviewedfoodlossesandfoodwaste(FLW)dataintermsof yearofpublication.(B)TemporaltrendofreviewedFLWdataintermsofyearofestimation.

Figure1.4 Geographicaldistributionofcasecountries.Thenumbersarethereportedtimes ofindividualcountries.

Source:AdoptedfromXue,L.,Liu,G.,Parfitt,J.,Liu,X.,VanHerpen,E.,Stenmarck,A

., etal.,2017.Missingfood,missingdata?Acriticalreviewofglobalfoodlossesandfood wastedata.Environ.Sci.Technol.51(12),6618 6633.

1.3.1.4Foodsupplychaincoverage

Accordingtothepublicationsfound,theycovereddifferentstagesinthefoodsupplychainintermsofmedium/high-incomecountriesandlow-incomecountries.

Fig.1.5 showsthatmoststudiescoveredtheretailingandconsumptionstages.In total,thelargestnumberofstudieswerecarriedoutinhousehold,accountingfor

Figure1.5 Thenumberofpublicationsintermsofdifferentfoodsupplystagesanddifferent developmentlevelsofcountries.

49%ofallthepublications,whichwasfollowedbytheretailingstages(35%). However,onlyasmallportionofstudiesincludedthestagesbetweenagricultural productionanddistribution.Indetail,agriculturalproduction,postharvesthandling andstorage,manufacturing,anddistributionstagesaccountedfor26.7%,18.8%, 28.7%,and21.8%,respectively.

Inthecaseofregionstudied,thenumberofpublicationsinmedium/high-income countrieswasmuchhigherthanthatinlow-incomecountriesalongthefoodsupply chain,apartfromthepostharvesthandlingandstoragestagewiththesamenumber ofpublicationsforboth.Themajorityofstudiesinvolvingretailingandconsumptionstageswereconductedinmedium/high-incomecountries,occupying31.2% and42.6%ofalltheliterature,respectively.Ontheotherhand,low-incomecountriesweretargetedmainlyintheearlyandmiddlestagesofthefoodsupplychain, especiallyfortheagriculturalproductionandpostharvesthandlingandstorage stages. 1.3.2Differentmethodsusedforfoodlossesandfoodwaste

1.3.2.1Overviewofmethods

TherewerevariousmethodsusedtomeasurethequantityofFLWalongthefood supplychain. Table1.2 summarizesthemethodsusedtoquantifyFLW.Twokinds ofmethodologieshavebeenusedtoquantifyFLW,whichcanbedividedintotwo

Table1.2 Descriptionofdifferentmethodsusedforfoodlossesandfoodwastequantification

MethodSymbolExampleofcase countries/regions

Direct measurement

Indirect measurement

FoodsupplychainReferences

WeighingWPortugalP6b Dias-Ferreiraetal.(2015)

GarbagecollectionGAustriaP6a Dahle ´ nandLagerkvist(2008)

SurveysSUnitedKingdomP1,P2,P3,P5 Menaetal.(2014)

DiariesDUnitedKingdomP6a Langleyetal.(2010)

RecordsRSwedenP5 Scholzetal.(2015)

ObservationOItalyP6b Saccaresetal.(2014)

ModelingMUnitedStatesP6 Halletal.(2009)

FoodbalanceFGlobalP1,P2,P3,P4,P5,P6 Gustavssonetal.(2011)

UseofproxydataPSingaporeP6a GrandhiandAppaiahSingh(2016)

UseofliteraturedataLDenmarkP1,P3,P4,P6 Halloranetal.(2014)

Note:P6a 5 Household,P6b 5 Out-of-home.

groups:(1)directmeasurementorapproximationbasedonfirst-handdata,and(2) indirectmeasurementorcalculationderivedfromsecondarydata.Thesemethods couldprovideaninsightoforiginsandspecificstagesinthewholefoodsupply chainofFLW,oranoverviewofFLWattheregionalorgloballevelfromamacroperspective.Detailedinformationonthemethodsusedisoutlinedasfollows: Directmeasurementinvolvesavarietyofmethodstoquantifyorestimatethe amountofFLW:

● Weighing:Itisusuallyusedinrestaurants,hospitals,andschoolviainstrumentordevice tomeasuretheweightofFLW.ItmayormaynotinvolveweighingeachpartofFLWfor thecompositionalanalysis.

● Garbagecollection:Thisinvolvesseparationfromothertypesofresidualwastescollected todeterminetheweightorproportionofFLW.Itmayormaynotinvolvecompositional analysisofFLW.Itcanbecollectedfromhouseholds(Gutie ´ rrez-BarbaandOrtega-Rubio, 2013).

● Surveys:Questionnairesareusedtocollectinformationaboutperceptionsandbehaviors onFLWansweredbyagreatmanyindividuals,orbyface-to-faceinterviewswithmajor stakeholdersinthefield.Thisusuallytakesplaceinhouseholds,wherepeoplecandirectly estimatethequantityoffoodwasteorthepercentageoffoodpurchasedthatgoestowaste intheirfamilies(Stefanetal.,2013).

● Diaries:Itisoftenusedinhouseholdsandcommercialkitchensbyrecordingthequantity ofFLWforacertaintime,whereweighingscalesaresometimesusedtoquantifythe amountofthefoodwaste(RathjeandMurphy,2001).

● Records:Itisusuallyusedintheretailingandmanufacturingstages,especiallyforsupermarketsandlarge-scalefoodcompanies,whereregularcollectionofinformation(notinitiallyusedforFLWrecord)candeterminethequantityofFLW.

● Observation:VisuallyestimatingtheamountoffoodleftoverbyusingscaleswithmultiplepointsorassessingthevolumeofFLWbycountingthenumberofgoods.

Theothergroupincludesmethodsbasedontheexistingdatafromdifferentsecondarysources:

● Modeling:ItusesmathematicalmodelstoobtaintheamountofFLWonthebasisofthe factorsthataffectFLWgeneration.

● Foodbalance:Usingfoodbalancesheet(e.g.,FAOSTAT)basedoninputs,outputs,and stocksinthefoodsupplychaintocalculateFLW,orhumanmetabolism(e.g.,therelationshipbetweenbodyweightandtheamountoffoodeaten).

● Useofproxydata:Usingdatafromcompaniesorstatisticalinstitutions(inanaggregated level)toestimatetheamountofFLW.

● Useofliteraturedata:UsingdatafromliteraturedirectlyorestimatingquantitiesofFLW accordingtothedatainotherliterature.

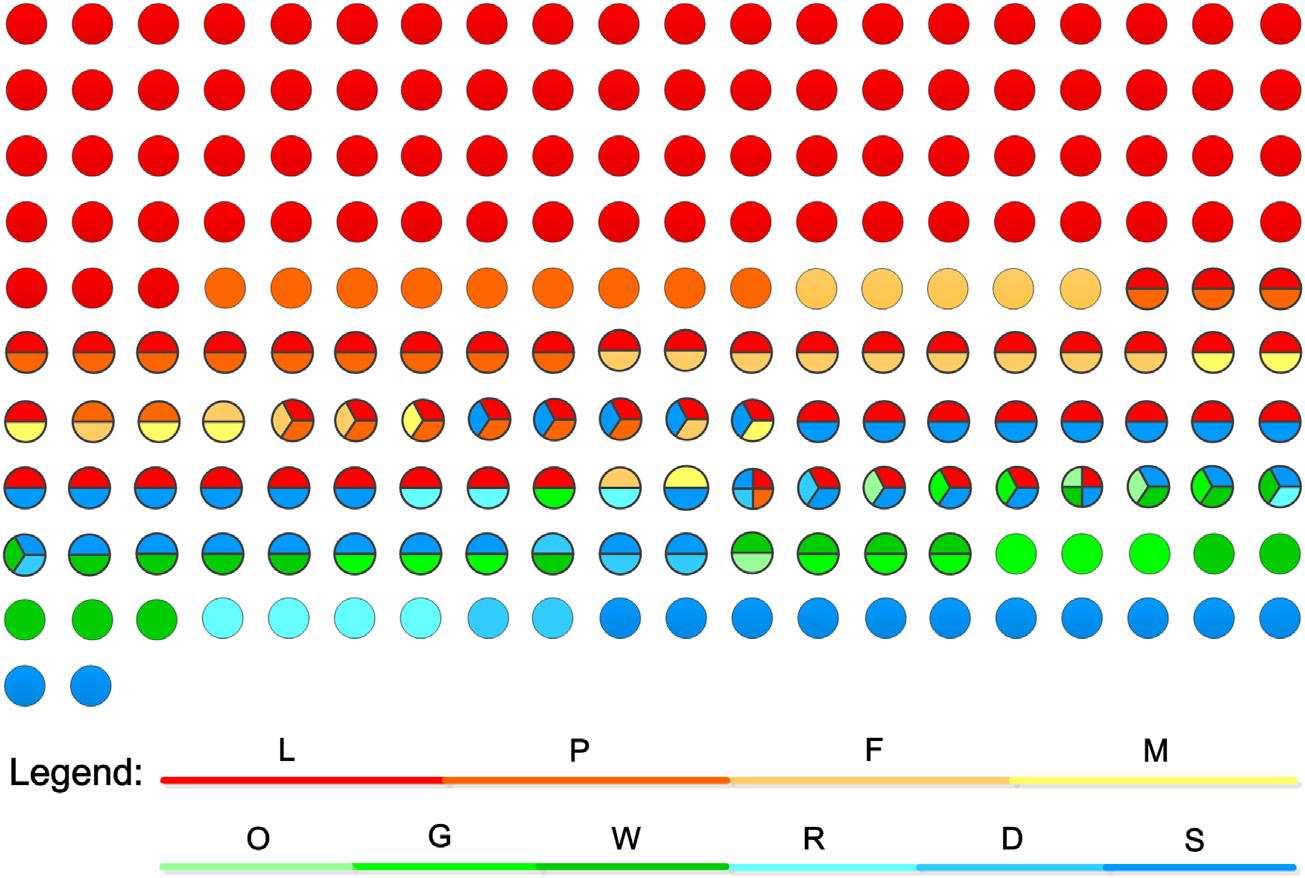

Fig.1.6 showsthemethodsusedinthe202publications.Itcanbeseenthat mostofthepublicationsdependedontheindirectmeasurement(red-yellow(dark grayinprintversion)colorsin Fig.1.6).Morethan40%ofthemwereonlybased onliteraturedata,andaboutone-thirdusedothertypesofmethodswithliterature data,forinstance,modeling(KhanandBurney,1989;Liuetal.,2013)orproxy data( Gooch,2012;Anetal.,2014)(indirectmeasurement)orweighingorsurveys( Papargyropoulouetal.,2014;Edjabouetal.,2015)(directmeasurement).

Figure1.6 Anoverviewofthemethodsusedinthereviewed202publications.Eachcircle indicatesonepublication,andthecolorsrepresentdifferentmethodsused.Direct measurementincludes:weighing(W),garbagecollection(G),surveys(S),diaries(D), records(R),andobservation(O).Surveysalsocontainquestionnaires,interviewsand experts’estimation.Indirectmeasurementinvolves:useofliteraturedata(L),useofproxy data(P),foodbalance(F),andmodeling(M).

Source:AdoptedfromXue,L.,Liu,G.,Parfitt,J.,Liu,X.,VanHerpen,E.,Stenmarck,A ˚ ., etal.,2017.Missingfood,missingdata?Acriticalreviewofglobalfoodlossesandfood wastedata.Environ.Sci.Technol.51(12),6618 6633.

Onlyasmallfractionofth epublicationsdependedonthedirectmeasurement. Inaddition,forthe138publicationsusingliteraturedata,theyoftendepended oneachotherandsomepublicationshavebeenhighlycited.Morethanonefourthofthemreferredtothedatafromthetop10publicationscited,andthe numberofcitationshasgreatlyincreasedsince2008( Fig.1.7 ).ThehighpercentageofusingthesecondarydatamayindicatethattheavailableglobalFLWdatabasehashighuncertainties,especiallywhenthereislackoforiginaldatafor acertaincountryoracertainyearbutliteraturedatathatarenotrepresentative areused.

1.3.2.2Advantagesanddisadvantagesofmethods

Table1.3 liststheadvantagesanddisadvantagesofdifferentmethodsbasedon somecriteria(e.g.,time,cost,andaccuracy).

● Weighingandgarbagecollectioncanproviderelativelydetailed,objective,andaccurate informationoffooddiscarded.ThesetwomethodsmayleadtofullquantificationofFLW andcanproducemoredetaileddataatthefoodtypeslevel.However,theycanbe

Figure1.7 Thecitationnetworkofthe138publicationsthatusedliteraturedata.Eachdot indicatesonepublication.Thesizeofthedotrepresentsthenumberofcitations,andthe arrowrepresentsthedirectionofcitation.Thedotsinwhiteontherightrepresent publicationsoutsidethecitationnetwork.Thetop10citedpublicationsare:(1) Kantoretal. (1997);(2a) WRAP(2009);(2b) Gustavssonetal.(2011);(3a) WRAP(2008);(3b) Monier etal.(2010);(3c) BuzbyandHyman(2012);(4a) Kader(2005);(4b) Kranertetal.(2012); (5a) Buzbyetal.(2009);(5b) Langleyetal.(2010).

Source:AdoptedfromXue,L.,Liu,G.,Parfitt,J.,Liu,X.,VanHerpen,E.,Stenmarck,A

., etal.,2017.Missingfood,missingdata?Acriticalreviewofglobalfoodlossesandfood wastedata.Environ.Sci.Technol.51(12),6618 6633.

performedonlywhenspaceavailableforclassifyingfoodandwithdevicetoweigh,and theyarealsomoretime-consumingandexpensivethanothermethods.Forexample,a studyonfoodwasteinrestaurantswasconductedinfourChinesecasecities(Beijing, Shanghai,Chengdu,andLhasa)in2015,whichdirectlyweighedfoodwastefrom3557 tablesin195restaurantsofdifferentcategories,includinglunchanddinnerbyindividual items.Itisestimatedthatfoodwastepercapitainrestaurants(approximately11kg/cap) isclosetotheaveragelevelofWesterncountries.Thisisafirstapproximationofthe scalesandpatternsofrestaurantsfoodwasteinChinesecities,whichcanhelpinformthe strategiesonfoodwastereduction(Wangetal.,2017).Inaddition,theaccuracyofwaste compositionanalysisreliesonthemethodsused,andithasidentifiedvarioussourcesof error(LebersorgerandSchneider,2011).

● Surveys,diaries,records,andobservationareotherwaysofdirectmeasuringand approximatingFLWdata,whichconsumeslesstimeandcostsmorethanweighing. However,duetosomefactorssuchaspers onalviews,thewayofrawdatacollection,

Table1.3 Advantagesanddisadvantagesofdifferentmethodsusedforfoodlossesandfoodwastequantification

andsubjectivityofobservers,theaccuracyofthedatacollectedmaybelower.Surveys thatincludequestionnairescanbecompletedbyemailorbyphone,orbyface-to-face interviewsandexpertestimation.ButbiasesmayoccurinFLWestimationbecausethis methoddependsonthememoryofpeopleand theymayprovideanswersthatthesocietyexpects.Forexample, Nazirietal.(2014) conductedquestionnairesurveys,focus groupdiscussion,andkeyexpertinterviewsonpostharvestlossesofcassavaduring JulyandOctober2012infourindividualdevelopingcountries(Ghana,Nigeria, Thailand,andVietnam)toinvestigatetheamountoflossesandexploremitigationstrategies.Diariescanbeaheavytaskforparticipants,andcausegradualdeclineofparticipants’enthusiasm( Langleyetal.,2010 ),aswellasdifficultiesinrecruitmentandhigh dropoutrates( Sharpetal.,2010).Inaddition,keepingdiariesmayhaveinfluenceson changesinawarenessandbehavior,whichw illleadtouncertainaccuracyofthediaries ( Sharpetal.,2010).Forexample,toanalyzethecompositionoffoodwasteinthe UnitedKingdomhouseholds, Langleyetal.(2010) asked13householdstokeepadiary for7days,recordingtheinformationonthetype,origin,andweightoffoodwaste. RecordsoftencostlessandtakelittletimetogetFLWdata.Observationisarelatively quickwaytoestimateFLW,buttheaccuracyandreliabilityarequestioned.

● Becauseoflowcostandhighfeasibility,secondarydataiswidelyusedtomeasurethe amountofFLW.Butthereishigheruncertaintyamongthesemethods.Formodeling,the choiceofmodelparametersandtherelationshipbetweenthesefactorsandthequantityof FLWwouldlargelyaffecttheresults.Forfoodbalancemethod,theaccuracyisdeterminedbythequalityandcomprehensivenessofthefoodbalancesheetdata.Themost cost-effectiveandfeasiblewaytoobtaindataisbyusingproxydataandliteraturedata, however,theiraccuracyprimarilyreliesonthequalityandrepresentativenessofthe sourcedataused.Ifthedataareuncertainandinaccurate,theresultswouldalsonotbe reliable.

Inreality,nodirectorindirectmethodscanbesatisfactory.Despitetheadvantages,directmeasurementusuallyinvolvesalimitednumberofparticipantsina certaincommunityorcityandacertainstageofthefoodsupplychain,whichcould leadtoanunavoidableproblemofdeficiencyofrepresentativeness,especiallyfor thelargecountriesliketheUnitedStatesandChina.Ontheotherhand,indirect measurementcanprovideanoverviewoftheentirecountryandvariousstages.A combinationofdirectandindirectmeasurementcouldbeabetterchoicetoillustratetheFLWproblem.Forpolicymakingandmitigationstrategies,basedonthe statisticaldataatthenationalorregionallevelitcoulddeterminetheseverityofthe problem.Forthedesignofeffectiveinterventionsteps,usingfirst-handdataand exploringthedrivingandinfluencingfactorscouldbeagoodapproach.

ThechoiceofmethodhasasignificantimpactontheFLWquantification,which couldresultindatadisparityintheliteratureexamined.Forexample,itwas reportedthatthefoodmanufacturingindustryinItalyproducedabout5.7million tonnesofFLWin2006(Monieretal.,2010),whileanotherstudybasedonmodelingestimatedabout1.9milliontonnesofFLWforthissector(Brautigametal., 2014).Suchbigdifferenceexistsbetweenthembecausetheyuseddifferentdata sourcesandassumptions.TheformeroneincludedFLWandrecycledorreused byproducts,whereasthelatteroneadoptedthelossrateinthemanufacturingsector andthemethodreportedbyFAO(Gustavssonetal.,2013).

1.3.3.1Farmlossesandwaste

Attheagricultureproductionstage,theFLWinlow-incomecountriesisgenerally higherthanthatinmedium/high-incomecountries,becausethereismoreadvanced technologyandinfrastructureforharvestinginrichcountries.Forexample,itis reportedthatFLWatthisstageaccountsforthelargestportion(26%)ofthetotal FLWinSouthAfrica(SpeschaandReutimann,2013)whereasitmakesup13%ofthe overallFLWacrossthefoodsupplychaininCanada(NahmananddeLange,2013).

Accordingtotheexistingdata,thereislittleinformationonFLWoffoodcommoditiesintheagriculturalproductionandharvestingstage.Fordifferentfoodcategories,onapercapitalevel,cereallossisthelargestwithamedianofroughly 16kg/cap.Forexample,itisreportedthatabout5% 9%ofcerealwaslostatthis stageinChina,andasimilartrendcanbeseeninGhana(WorldBank,2011). Fruitsandvegetablesarethesecondlargestwastedcategoryatthisstagewitha valueof13kg/cap.However,thereisasignificantdifferenceoffruitand vegetablelosses/wastebetweenlessdevelopedandindustrializedcountries.For example,fruitandvegetableFLWmadeupabout20% 30%ofthetotalproductioninChina(Liu,2014)whileitaccountedforonly6% 15%atthisstageinItaly (Segre ` etal.,2014).Thereasonforthebigdifferenceisthatmoreadvancedand newertechnologiesareusedindevelopedcountries.ThereisasmallfarmFLWof meatandfish,dairyproducts,andeggsattheproductionlevel(Fig.1.8).

1.3.3.2Postharvestlossesandwaste

PostharvestFLWoccursduringthepostharvesthandlingandstorage,manufacturing,distribution,andretailingstages,wheredistinctivecharacteristicscanbeseen

Figure1.8 Percapitafarmfoodlossesandfoodwasteofdifferentfoodcommodities.