https://ebookmass.com/product/possessed-by-the-virginhinduism-roman-catholicism-and-marian-possession-in-south-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

John of Damascus' Marian Homilies in Mediaeval South Slavic Literatures Tsvetomira Danova

https://ebookmass.com/product/john-of-damascus-marian-homilies-inmediaeval-south-slavic-literatures-tsvetomira-danova/

ebookmass.com

Deities and Devotees: Cinema, Religion, and Politics in South India Uma Maheswari Bhrugubanda

https://ebookmass.com/product/deities-and-devotees-cinema-religionand-politics-in-south-india-uma-maheswari-bhrugubanda/

ebookmass.com

Power and Possession in the Russian Revolution Anne O'Donnell

https://ebookmass.com/product/power-and-possession-in-the-russianrevolution-anne-odonnell/

ebookmass.com

Understanding Biology Kenneth Mason Et Al.

https://ebookmass.com/product/understanding-biology-kenneth-mason-etal/

ebookmass.com

My Highland Enemy (Warriors of the Highlands Book 7): An Enemies to Lovers Historical Romance Novel Miriam Minger

https://ebookmass.com/product/my-highland-enemy-warriors-of-thehighlands-book-7-an-enemies-to-lovers-historical-romance-novel-miriamminger/

ebookmass.com

Negotiation: Readings, Exercises, and Cases 7th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/negotiation-readings-exercises-andcases-7th-edition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

A topical approach to life-span development 9th Edition John W. Santrock

https://ebookmass.com/product/a-topical-approach-to-life-spandevelopment-9th-edition-john-w-santrock/

ebookmass.com

Android Smartphone Fotografie für Dummies Mark Hemmings

https://ebookmass.com/product/android-smartphone-fotografie-furdummies-mark-hemmings/

ebookmass.com

The Protests of Job : An Interfaith Dialogue Scott A. Davison

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-protests-of-job-an-interfaithdialogue-scott-a-davison/

ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/plazas-5th-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

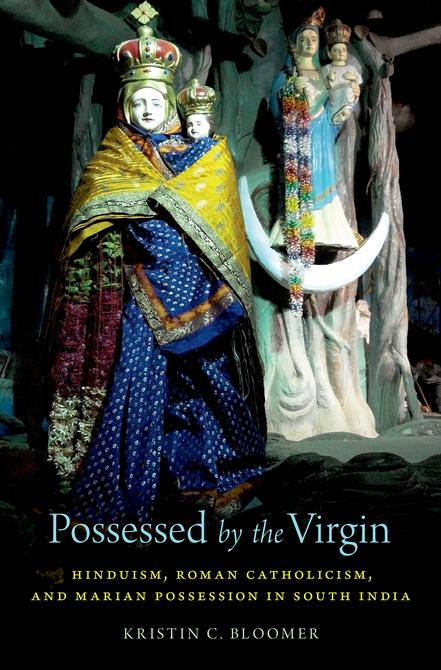

Possessed by the Virgin

Possessed by the Virgin

Hinduism, Roman Catholicism, and Marian Possession in South India

Kristin C. Bloomer

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Bloomer, Kristin C., author.

Title: Possessed by the Virgin : Hinduism, Roman Catholicism, and Marian possession in South India / Kristin C. Bloomer.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, 2018. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017006768 (print) | LCCN 2017039303 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190615109 (updf) | ISBN 9780190615116 (epub) | ISBN 9780190615123 (oso) | ISBN 9780190615093 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Mary, Blessed Virgin, Saint—Cult—India—Tamil Nadu. | Christianity—India—Tamil Nadu. | Mariyamman (Hindu deity)— Cult—India—Tamil Nadu. | Tamil Nadu (India)—Religious life and customs.

Classification: LCC BT652.I4 (ebook) | LCC BT652.I4 B56 2017 (print) | DDC 200.954/82—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017006768

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

For my parents and sisters

CONTENTS

Acknowledgments ix

Dramatis Personae xiii

Note on Transliteration xv

Maps of India xvii

Introduction 1

1. Rosalind 32

2. The Place, the People, the Practices: Our Lady Jecintho and the Quest for Embodied Wholeness 56

3. Authenticity and Double Trouble: The Case of Nancy-as- Jecintho 84

4. Possession, Processions, and Authority 109

Interlude 130

5. Return to Mātāpuram 133

6. Women’s Work: Gendered Space and the Dangerous Labor of (Virgin) Birth 156

7. Memory, Mimesis, and Healing 187

8. Conclusion: Departures and Homecomings 209

Epilogue 234

Notes 247

Glossary 289

Bibliography 295 Index 309

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

To have worked on a project for more than a dozen years means that I have lots of people to thank—more than can possibly be listed here. But I will try.

First, to the Tamil women about whom this book is written, I owe a debt I can never repay. They opened their lives to me with immeasurable grace, hospitality, and patience— for reasons I may never be able to understand. To “Dhanam,” her extended family, and to all the people of “Mātāpuram;” to S. Nancy Browna and family; and last, but certainly not least, to C. Rosalind and family— to M. Charles, Lawrence, Robert, Benjamin, M. Paul, Celina, Ruby Mary, their spouses and children, Julie, Alex, and the entire extended family of Our Lady Jecintho Prayer House—mikka anbudan. I will never be able to communicate the depth of my gratitude.

For the kindness of strangers. To the guard at Chennai International Airport who hailed my first auto-rickshaw on my first night in India; to the driver of that auto, who dropped me in the middle of that night in the middle of a dark highway amidst a group of day-and-night-laborers; to those same kind strangers, who pushed me backpack and all onto the bus that would take me to Pondicherry: thank you. To the myriad people who helped pave my way— the coffee-karars, sari- tiers, restaurant servers, hotel owners, night watchmen, slum dwellers, house holders, fish sellers, kadai-karars, farmers, relief workers, painters, dancers, doctors, business people, children, and civil servants, especially the immigration official who tried to kick me out of the country (resulting in my stumbling upon the subject of this book): thank you.

To my teachers. To Annie Dillard, whose friendship and early mentorship changed my life. To my two dissertation advisers: Wendy Doniger, One Amazing Woman, and Kathryn Tanner, whose brilliance and bravery inspired me from the start. To the two outside members of my doctoral committee: Kalpana Ram, whose first book catalyzed my interest in this topic, and Corinne Dempsey, whose warm friendship, sense of humor, commitment to intellectual community, and thirst for adventure lift my heart. To Dan Baum and Margaret Knox, working writers and great lovers of life, who have mentored me from my first years as a journalist through today

( x ) Acknowledgments

and who— along with Rosa Knox- Baum— gave me a place to live in Boulder, Colorado, when I came back broke from India. Thank you.

To my Tamil instructors. At the University of Chicago, the late Norman Cutler introduced me to the romance of bhakti poetry through Hymns for the Drowning while helping me discern the difference between adverbial and adjectival participles. John Bernard “Barney” Bate’s high spirits, big heart, and famous fluency kept me from giving up. James Lindholm, who wrote the best textbook on Tamil yet to be written, supported me morally and generously in our tutorials; Jonathan Ripley and Benjamin Schonthal modeled what it meant to be a good student of Tamil; and David Shulman passed on his patient teaching and love for the language. In India, the Summer Tamil Language Program at the French Institute of Pondicherry enabled my first Tamil “field interview” with the family of a boy possessed by St. Anthony; and in Madurai, Dr. S. Bharati at the American Institute of Indian Studies, now at the University of California–Berkeley, showered us with learning like the goddess Saraswati.

To academic institutions and scholars in India. S. Anandhi, Padmini Swaminathan, and A.R. Venkatachalapathy took me under their wings at the Madras Institute of Development Studies and shepherded me through particularly difficult times. In Palayamkottai, the Folklore Resources and Research Center at St. Xavier’s College shared their holdings, and Peter Arokiaraj in particular labored to procure copies of texts and films that gave me early insights into Marian possession in rural Tamil Nadu.

In Chennai, the generous hospitality and intellectual companionship of Dr. Nirmal Selvamony, his wife Dr. Ruckmani, and their daughters Madhini and Padini enriched my experience more than I can express. Sitting around their dining table late into the night discussing everything from Tolkāppiyam to contemporary Tamil politics, they lost much sleep while feeding my mind, soul, and body. The completion of this book and many of its insights are very much indebted to our conversations.

To my research assistants. S. Padma Balaji of Chennai helped me tirelessly from 2005 to 2006, through floods and hot, dry spells, while sharing hearty laughter and hardwork. Her interviewing techniques were impeccable. M. Thavamani of Gingee lent me invaluable assistance from 2005 to the end of this book and beyond, traveling many miles away from his farm and his family to help me navigate difficult interviews and painstakingly transcribe recordings. Some of my favorite memories include sitting in his own house in beautiful Pasumalaithangal, coffee by my side, as we worked on these translations together. To his wife, Jothi, and to his children, Anna and Les: mikka anbu.

To the many priests and nuns who extended their generosity: Rev. Fr. Bernard Lawrence of Annai Velankanni, Besant Nagar; Rev. Fr. Vincent Chinnadurai and Rev. Fr. Gaspar of Chennai; Rev. Fr. Ananthan of Sacred Heart Seminary, Poonamalee; Rev. Sr. Dr. Mother Annamma Philip and Sr.

Florine Monis of Stella Maris College; Rev. Fr. Pictaimuuthu, the wandering priest of the people; the priests at the Basilica of Our Lady Velankannni, Nagapattinam; Rev. Fr. Aasir Vatham of Sivagangai Diocese; the Most Rev. M. Devadass Ambrose, Bishop of Thanjavur; Rev. Fr. Arul Selvam of Sivagangai; Rev. Fr. R. K. Sami of the Liturgical, Biblical and Catechismal Institute, Bangalore; Rev. Dr. G. Patrick of the University of Madras; and Rev. Fr. S. P. Xavier, now of Kolkata, who first helped me to understand the rosary in Tamil. Nandri.

To the many people who helped me navigate the aftermath of the 2004 Asian Tsunami, opening their hearts, homes, and stories to me, and to the Sisters of the Sacred Heart of Jesus Convent in Nagercoil, who housed and fed me: thank you.

To my many colleagues and friends throughout the United States who sustained me through various stages of this book, even before it began, I owe thanks beyond words. I list you non-alphabetically and in no particular order, but in groupings you may recognize: Lee Siegel, Elizabeth Blalock, Monica Ghosh, Paul Lyons, Sai Bhatawadekar, Chad Bauman, Steven Hopkins, Selva Raj, Joyce Flueckiger, Kaori Hatsumi, Gemma Betros, Anne Braude, Judith Casselberry, Hauwa Ibrahim, Zilka Spahić Ŝiljak, Francis X. Clooney, Chinnappan Devaraj, Sarah Feldman, Gabriel Robinson, Gabi Marcus, Eliza Kent, Elaine Craddock, Gillian Goslinga, Kristen Rudisill, Katherine Ulrich, C. Maheswari, Gardner Harris, Venkatesh Chakravarty, Francis Cody, Davesh Soneji, Shiladitya Sarkar, Martha Selby, James Laine, Erik Davis, Pam Percy, Sigrid Austin, Venkateshwaran Ravichandran, Dietrix Jon Ulukoa Duhaylonsod, J. Michelle Molina, and Wendy Boxer. My colleagues at Carleton College kept me afloat with ongoing good cheer and intellectual companionship, most belovedly: Amna Khalid, Paul Petzschmann, Meera Sehgal, Brendan LaRoque, Noah Salomon, Roger Jackson, Lori Pearson, Michael McNally, Louis Newman, Asuka Sango, Kevin Wolfe, Sonja Anderson, Sandy Saari, Bardwell Smith, Eleanor Zelliot, Annette Nierobisz, Jane McDonnell, Paula Lackie, Liz Coville, Van Dusenbery, Amel Gorani, Anita Chikkatur, Laurel Bradley, Sam Demas, Peter Balaam, and Laska Jimsen. Many of my former graduate students at the University of Hawaii-Manoa, now dear friends—Deeksha Sivakumar, Juston Stein, and Jessica Freedman, in particular—gave me helpful feedback and emotional support. At Carleton College, the ongoing curiously, insight, and open minds of my students, especially in “Many Marys,” the “Sacred Body,” and “Spirit Possession,” gave me innumerable insights and kept me on my toes.

This research was generously funded by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the American College of Learned Societies, the Women’s Studies in Religion Program at Harvard University, the Center for the Study of World Religions at Harvard University, Carleton College, the University of Hawaii Research Relations Fund, the American Institute of Indian Studies, the

Fulbright-Hays Doctoral Dissertation Research Abroad Fellowship, and, at the University of Chicago, the Committee on South Asian Studies, the Martin Marty Center, the Center for Gender Studies, and the Harper Dissertation Writing Fellowship. Carleton College granted me four terms of leave for research and writing.

To editors, to my two anonymous outside readers, whose comments and suggestions helped me focus and pare down a manuscript that threatened to outweigh Moby Dick. To Cynthia Read, my editor at Oxford University Press whose early faith in this project gave me hope; to Drew Anderla, the editorial assistant who answered my emails swiftly and with much appreciated exclamation points; and to Ginny Faber, a terrific copy editor. To Tracy Thompson and Jerri Hurlbutt, who helped me edit early versions of this manuscript, and to Katherine Ulrich (again), indexer and Indologist editor extraordinaire. Thank you.

To Brian Welch, whose patience, emotional support, fastidious proofreading, and level-headedness helped me especially through later stages of this project.

Last but not least, to my family. To my cousin John J. Bloomer, who took me salsa dancing in Cambridge when I desperately needed it, and to the Bruce and Sandy Bloomers who housed and cheered on cross- country treks from Minnesota to Massachusetts and back. To my nieces Izzy and Addy Bloomer- Duffy, the lights of my life who delight me both in person and over Face Time, Instagram, and Musical.ly. To my grandparents, whose spirits inform this work. And, most deeply: to my parents, John and Patricia Bloomer, and to my sisters, Karin and Joanna Bloomer— without whose support and love this book would never have been possible, let alone conceivable. There is no word for “thank you.”

DRAMATIS PERSONAE (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE, ORGANIZED BY PLACE)

OUR LADY JECINTHO PRAYER HOUSE

Alex: M. Paul’s son, Rosalind’s youngest cousin, who first fell ill; had visions of Mary; and later became possessed

Rosalind: Charles’s daughter, the eldest child in the family, and only girl

Fredy: Rosalind’s son

M. Charles: Rosalind’s father

Lawrence: Charles’s eldest son, Rosalind’s brother

Maria Auxilia: Lawrence’s wife

Benjamin: Charles’s second son

Robert: Charles’s third son and Rosalind’s youngest brother, to whom she is closest

M. Paul: Charles’s younger brother, Rosalind’s uncle

Celina: M. Paul’s wife, a Hindu

Ruby Mary: M. Paul’s eldest daughter

Julie: M. Paul’s youngest daughter

Francina: Rosalind’s attendant, confidante, and best friend

Lata: possessed by pēy, and a prayer house member

Anna Francis: prayer house member

Rex: lay preacher and prayer house member

Rev. Dr. Lawrence Pius: Auxiliary Bishop of Madras-Mylapore Archdiocese

Rev. Fr. Vincent Chinnadurai: parish priest of St. Patrick Church at Saint Thomas Mount, Chennai; first told me about Rosalind

Sr. Florine Monis: Director of Administration at Stella Maris College, Chennai

Rev. Sr. Dr. Mother Annamma Philip: Principal of Stella Maris, Chennai

Rev. Fr. Pitchaimuuthu: priest supporting Our Lady Jecintho Prayer House

Most Rev. Dr. A. M. Chinnappa: Archbishop of Madras-Mylapore Archdiocese

Rev. Fr. A. Thomas: parish priest of Muthamizh Nagar, in which Our Lady Jecintho Prayer House is located

KODAMBAKKAM, CHENNAI

Nancy: S. Nancy Browna, the second woman to get possessed by Jecintho Mātā, after Rosalind

Maatavan Shanthakumar: Nancy’s father

Leela: Nancy’s mother

Antony: Nancy’s brother (younger)

S. Padma Balaji: field assistant, from Chennai

Vadivambal: Nancy’s paternal grandmother

Rev. Fr. Ambrose: parish priest of Our Lady of Fatima Church, Kodambakkam

MĀTĀPURAM (ALIAS NAMES)

Dhanam: possessed by Mātā

Rev. Fr. Arlappan: guide back to Mātāpuram; Aarokkiyam’s brother

Aarokkiyam: Arlappan’s brother and Sahaya Mary’s husband

Sahaya Mary: Dhanam’s neighbor, a woman possessed by Pandi Muni

Sebastiammal: Aarokkiyam and Arlappan’s mother

Ubakaram: Aarokkiyam and Arlappan’s grandmother

Sebastian Samy: Dhanam’s husband

Sofia Mary: Dhanam’s daughter

Peter Raj: Dhanam’s son-in-law, husband of Sofia Mary

Adaikkala Raj: Dhanam’s eldest son

Aananthan: Dhanam’s second eldest son; ordained priest

Dhanam’s youngest son: unnamed seminarian in Agra

M. Thavamani: field assistant, from Gingee

Arokkiya Mary: Dhanam’s daughter and eldest child

Rev. Fr. Michael Antony: Dhanam’s brother, living in Agra

Rev. Fr. Aasir Vatham: parish priest of Sahaya Mary Church, Devakotai

NOTE ON TRANSLITERATION

Tamil words were transliterated following the University of Madras Tamil Lexicon. According to this system, “c” is pronounced “s,” and “ḻ” is the unique Tamil letter linguists refer to as the voiced retroflex approximate, which is pronounced somewhere between “l” and retroflex “r.” For reading ease, Tamil personal, caste, and place names are given with diacritics at first mention if at all and then without diacritics using the most widely recognized Anglicized forms. Also for easier reading, I have generally transliterated the Sanskrit “ś” as it sounds: “sh.” Most non-Tamil Indian words have been transliterated without diacritics, using the standard Anglicized forms when possible.

MAPS OF INDIA

Map 1: India and its states, with Tamil Nadu highlighted.

Map 3: Chennai, with neighborhoods of Kodungaiyur, Kodambakkam, Mylapore, and Besant Nagar.

Possessed by the Virgin

Introduction

Itall started with the deaths of five men. That’s how Dhanam saw it, anyway.

The year was 1979. The victims were five Hindu Untouchables—now known as Dalits, which means “ground down” or “oppressed.”1 Their village was Chinna Unjanai, which lay in the parched, red- soil countryside of southern Tamil Nadu, India. Dhanam, a graceful tenant farmer with sleek black hair and a voice like velvet, was also a Dalit. Unlike the murdered men, she was Roman Catholic, and lived in Mātāpuram, the Roman Catholic village next to theirs. Both Dalit villages had been in the service of higher castes who had oppressed them for centuries.

It was a time of mounting tensions, especially on those rare occasions when high- and low- caste2 people came together—usually on important religious festivals. In June of 1979, some members of the Pallar clan from Chinna, also Dalits, had been barred by the higher- caste Kallars3 from participating in two annual religious processions—one at a huge Shiva temple in the nearby village of Kandadevi, and another to a lesser god named Aiyanar.4 The Pallars, denied the honor both of pulling the huge chariot carrying Shiva around town and also of carrying the terra- cotta horses for Aiyanar,5 cooked up a plan to hold their own Aiyanar festival. Somehow the Kallars learned of it, and hired some fifteen hundred low- caste people from another district to attack the men from Chinna.6 At dawn on June 29, the hired thugs set off fireworks in the fields outside the village, luring people outside.7 Then they attacked. They set fire to the village, and—armed with knives and hatchets—hacked five men to death, nearly killing a sixth and injuring about thirty more. The five dead men were buried between Chinna Unjanai and Mātāpuram.8 No Dalit—either in what remained of Chinna Unjanai or in the next-door village of Dalits, Dhanam’s village of Mātāpuram— slept well those nights.

( 2 ) Possessed by the Virgin

Dhanam was eighteen at the time of the murders, two years married and nursing a six-month-old daughter. News traveled quickly to Dhanam’s village: its residents were of the Paraiyar clan— from which the English word “pariah” comes. Paraiyar men historically went from village to village, shirtless, beating their parai drums, announcing upcoming festivities and funerals.9 Before the attack, Dhanam had seen the murdered Chinna men in passing. She knew their faces, and she had seen the white body bags in which they were brought back for burial after the postmortem. Now, collecting firewood or walking to the fields for water or work, she would sometimes pass by their headstones. In South India, many people believe that the spirits of the untimely dead— pēy—can “catch” women, especially newly married women, and cause illness or domestic havoc, even blocking their ability to conceive.10 Dhanam and her husband longed for a son—and Dhanam came to suspect that the pēy of the murdered Hindu men were preventing her from getting pregnant again. The minute she flicked off the single light bulb of their clay home, or extinguished a lamp, they would be standing there, dead, one holding his own head, the others’ faces swollen and blue. She feared she would never conceive. But when she was twenty-one, she felt a child stirring in her belly. She and her husband thought it might be a boy, which made them even happier.11

In the seventh month of Dhanam’s pregnancy, the rains refused to come. The naked sun raked the fields until the paddy withered and the dirt rose in puffs to the sky. Pregnant women were not supposed to fish, particularly not in Hindu territory—or so many local Hindus and Christians believed. But Dhanam was bold, the heat was unbearable, and the villagers’ stomachs were near empty— so she joined her husband and a crowd of villagers, and walked past the graves to catch fish on the other side of Chinna. The water level in the lake then had fallen so low, it was said, that people were catching fish with their bare hands. Villagers’ spirits were high as they set out with the prospect of cooling off and catching fish. They took the path along the shore through low-lying scrub and bramble, passing Aiyanar’s temple. The warrior god’s immense terra- cotta horse guarded the edge of Hindu terrain. His divine peons, lesser gods, animated the black stone icons housed there, all smeared with ghee, vibhuti, and kumkum12 in dark, cave-like shelters. Dhanam hardly noticed them, eager as she was to reach the boisterous activity at the lake.

The trip was a success: she and her husband caught several mackerel and catfish. But the way out was slippery, and she fell, belly-down, toward the bank. She thought little of it— she felt fine—and returned home with fellow villagers, relaxed and contented. Dhanam cleaned and cooked the fish, fed her husband and daughter, ate after they did, as is custom for women in South India, and went to sleep full and happy. But later in the night, Dhanam awoke in terrible pain. Her stomach ached and torqued; she couldn’t hold down her

food. Her husband carried her to the nearest health clinic in Aravaiyil, a village one-and-a-half-kilometers away, where a nurse gave her an injection.13 When the relief proved only temporary, Dhanam’s parents arrived to take her home to her natal village of Manapunjai, about twenty kilometers away.14 In the center of their village, as in Dhanam’s, was a chapel to Mary. Sick people often sought refuge there for healing—her father, a staunch devotee, sometimes said mantras over the sick in her name.

Dhanam’s parents brought her to the chapel, and her mother attended to her. She lay on the cool cement floor while her mother tried to feed her curd rice and gruel. She even tried to tempt her with murukku, the savory, crunchy twists of rice and chickpea flour usually reserved for South Indian holidays, but Dhanam wouldn’t eat. When it was clear that she was not improving, her parents took her to the Christian hospital in Puliyal, a few kilometers away. A medically trained nun gave Dhanam another injection, telling her that she was anemic and that her blood pressure was low. She should stay at least ten days and eat well, the nun said.

The pain only increased. Ten days later, Dhanam’s parents brought her back to the Mary chapel in her natal village.

It was there, lying on the cool stone floor of the chapel in Manapunjai, that Dhanam heard a madduk-madduck in her stomach and felt a shudder and shake in her womb: the death throes of the fetus. She felt faint, then drowsy. “Take me back to the hospital,” she said. The sisters in Puliyal gave her another injection, causing contractions.

The child, a boy, was stillborn.

Dhanam and her husband cried inconsolably. About ten other babies were born in the clinic that day. Dhanam’s was the only stillbirth.

They buried the small body in the cemetery outside the hospital and returned home to Mātāpuram, empty-handed.

Back home, the pain in Dhanam’s stomach remained; it became an ache that would not release her. She could barely breathe when the cramps came, and she thought she would suffocate, feeling at times as if several people were sitting on her chest.15 At night in her dreams, the five Dalit men returned in their gory lineup. She now knew her mistake— to pass the burial ground of the murdered men as a bride and new mother, with the fragrance of jasmine in her hair and the smell of sex on her skin, and to wade into a lake guarded by Hindu gods while pregnant. She had been too loyal to her Christianity to appeal to Hindu rites for protection. Now, it didn’t help that some people thought they would have saved her baby.

One night, as Dhanam lay in pain, bleeding, cramping, and mourning, Mary— whom the people of Dhanam’s village, like most Tamils, called Mātā (mother)— came to Dhanam’s pallet, took her by the hand, and led her to a