PAINMEDICINE ACASE-BASED LEARNINGSERIES

TheSpine

STEVEND.WALDMAN,MD,JD

Elsevier

1600JohnF.KennedyBlvd. Ste1800 Philadelphia,PA19103-2899

PAINMEDICINE:ACASE-BASEDLEARNINGSERIES THESPINE

Copyright © 2022byElsevier,Inc.Allrightsreserved

ISBN:978-0-323-75636-5

Allunnumberedfiguresare ©ShutterstockCh1#450846769,Ch2#119077213,Ch3#523752955, Ch4#1029126937,Ch5#797324008,Ch6#682553182,Ch7#51781282,Ch8#1080607136, Ch9#1145461898,Ch10#561008035,Ch11#1491945620,Ch12#514912501,Ch13#725790448, Ch14#1362404147,Ch15#278451497.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans, electronicormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageand retrievalsystem,withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseek permission,furtherinformationaboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangements withorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency, canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions

Thisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythe Publisher(otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notice

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgein evaluatingandusinganyinformation,methods,compoundsorexperimentsdescribedherein. Becauseofrapidadvancesinthemedicalsciences,inparticular,independentverificationof diagnosesanddrugdosagesshouldbemade.Tothefullestextentofthelaw,noresponsibility isassumedbyElsevier,authors,editorsorcontributorsforanyinjuryand/ordamageto personsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuse oroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2020950564

ExecutiveContentStrategist: MichaelHouston

ContentDevelopmentSpecialist: JeannineCarrado/LauraKlien

Director,ContentDevelopment: EllenWurm-Cutter

PublishingServicesManager: ShereenJameel

SeniorProjectManager: KarthikeyanMurthy

DesignDirection: AmyBuxton

PrintedinIndia.

Lastdigitistheprintnumber: 987654321

It’s Harder Than It Looks

MAKING THE CASE FOR CASE-BASED LEARNING

For sake of full disclosure, I was one of those guys. You know, the ones who wax poetic about how hard it is to teach our students how to do procedures. Let me tell you, teaching folks how to do epidurals on women in labor certainly takes its toll on the coronary arteries. It’ s true, I am amazing. . .I am great. . .I have nerves of steel. Yes, I could go on like this for hours. . .but you have heard it all before. But, it’ s again that time of year when our new students sit eagerly before us, full of hope and dreams. . .and that harsh reality comes slamming home. . .it is a lot harder to teach beginning medical students “doctoring” than it looks.

A few years ago, I was asked to teach first-year medical and physician assistant students how to take a history and perform a basic physical exam. In my mind I thought “this should be easy. . .no big deal” . I won ’t have to do much more than show up. After all, I was the guy who wrote that amazing book on physical diagnosis. After all, I had been teaching medical students, residents, and fellows how to do highly technical (and dangerous, I might add) interventional pain management procedures since right after the Civil War. Seriously, it was no big deal...I could do it in my sleep with one arm tied behind my back blah blah blah.

For those of you who have had the privilege of teaching “doctoring,” you already know what I am going to say next. It’s harder than it looks! Let me repeat this to disabuse any of you who, like me, didn’t get it the first time. It is harder than it looks! I only had to meet with my first-year medical and physician assistant students a couple of times to get it through my thick skull: It really is harder than it looks. In case you are wondering, the reason that our students look back at us with those blank, confused, bored, and ultimately dismissive looks is simple: They lack context. That’ s right, they lack the context to understand what we are talking about.

It’ s really that simple. . .or hard. . .depending on your point of view or stubbornness, as the case may be. To understand why context is king, you have to look only as far as something as basic as the Review of Systems. The Review of Systems is about as basic as it gets, yet why is it so perplexing to our students? Context. I guess it should come as no surprise to anyone that the student is completely lost when you talk about let’ s say the “constitutional” portion of the Review of Systems, without the context of what a specific constitutional finding, say a fever or chills, might mean to a patient who is suffering from the acute onset of headaches. If you tell the student that you need to ask about fever, chills, and the other “constitutional” stuff and you take it no further, you might as well be talking about the

InternationalSpaceStation.Justsaveyourbreath;itmakesabsolutelynosenseto yourstudents.Yes,theywanttoplease,sotheywillmemorizetheelementsofthe ReviewofSystems,butthatisaboutasfarasitgoes.Ontheotherhand,ifyoupresentthecaseofJannettePatton,a28-year-oldfirst-yearmedicalresidentwithafever andheadache,youcanseethelightsstarttocomeon.Bytheway,thisiswhat Jannettelookslike,andasyoucansee,Jannetteissickerthanadog.This,atitsmost basiclevel,iswhat Case-BasedLearning isallabout.

Iwouldliketotell youthat,smartguy thatIam,Iimmediatelysawthelight andbecameaconvert to Case-BasedLearning. Buttruthbetold,it wasCOVID-19that reallygotmethinkingabout Case-Based Learning.Beforethe COVID-19pandemic, Icouldjustdragthestudentsdowntothemed/surgwardsandwalkintoa patientroomandriff.Everyonewasawinner.Forthemostpart,thepatients lovedtoplayalongandthoughtitwascool.ThepatientandthebedsidewasallI neededtoprovidethecontextthatwasnecessarytoillustratewhatIwastrying toteach thewhyheadacheandfeverdon’tmixkindofstuff.HadCOVID-19 notrudelydisruptedmyabilitytoteachatthebedside,Isuspectthatyouwould notbereadingthis Preface,asIwouldnothavehadtowriteit.Withinaveryfew daysaftertheCOVID-19pandemichit,mydaysofbedsideteachingdisappeared,butmystudentsstillneededcontext.Thisgotmefocusedonhowto providethecontexttheyneeded.Theanswerwas,ofcourse, Case-BasedLearning. Whatstartedasadesiretoprovidecontext becauseitreallywas harderthanit looked ledmetobeginworkonthiseight-volume Case-BasedLearning textbookseries.Whatyouwillfindwithinthesevolumesareabunchoffun,real-life casesthathelpmakeeachpatientcomealiveforthestudent.Thesecasesprovide thecontextualteachingpointsthatmakeiteasyfortheteachertoexplainwhy, whenJannette’schiefcomplaintis, “MyheadiskillingmeandI’vegotafever,” itis abigdeal.

Havefun!

StevenD.Waldman,MD,JD

Spring2021

Averyspecialthankstomyeditors,MichaelHouston,PhD,JeannineCarrado, andKarthikeyanMurthy,foralloftheirhardworkandperseveranceintheface ofdisaster.GreateditorssuchasMichael,Jeannine,andKarthikeyanmaketheir authorslookgreat,fortheynotonlyunderstandhowtobringtheThreeCsof greatwriting...Clarity 1 Consistency 1 Conciseness...totheauthor’swork,but unlikeme,theycanactuallypunctuateandspell!

StevenD.Waldman,MD,JD

P.S. ...Sorryforalltheellipses,guys!

MimiBraverman

A68-Year-OldFemaleWith AcuteWorseningNeckand OccipitalPain

LEARNINGOBJECTIVES

• Learnhowrheumatoidarthritisaffectsthecervicalspine.

• Developahighindexofsuspicionforthepotentialforlife-threatening complicationsofunrecognizedrheumatoidarthritis-inducedatlantoaxial instability.

• Learntoidentifyriskfactorsassociatedwithanincreasedincidenceof rheumatoidarthritisaffectingthecervicalspine.

• Learntheclinicalpresentationofatlantoaxialinstabilitysecondarytorheumatoid arthritis.

• Learntheclassicclinicalpresentationofrheumatoidarthritisaffectingthehands.

• Understandtheroleoflaboratorytestingandimagingintheevaluationof rheumatoidarthritis-inducedatlantoaxialinstability.

• Learntoidentifytheneurologicfindingsassociatedwithcervicalmyelopathy.

• Developanunderstandingoftheroleofdisease-modifyingdrugsinthe preventionofrheumatoidarthritis-induceddamagetothecervicalspine.

MimiBraverman

MimiBravermanisa68-year-old femalewiththechiefcomplaintof, “IknowthatyouwillthinkI’ mcrazy, butitfeelslikemyheadisgoingtofall off.” Mrs.Bravermansaidthatshe knew “somethingwasn’trightwith herhead” forseveralmonths.Shehad attributedtheheadandneckdiscomfortto “oldage” andshechoseto “justlivewiththepain.” Anavidknitter,itwasn’tuntilacoupleofweeks ago,whenshelookeddownather knitting,thatshefeltandhearda “clunk” inherneck.Thepatientnotedthatthe “clunk” reallyscaredherandshewasworriedthat “somethingwasreally wrong. ” Shesaidthatthe “clunk” happenedacoupleofmoretimesanditscared hersomuchthatnowshewasafraidtoknit...eventhoughtheoccupational therapisttoldherthat “knittingwasgoodforherhands.”

Whenthepatientwasaskedtouseonefingertopointtotheareawherethe “clunk” camefrom,shepointedtotheposteriorocciput.Thepatientnotedthat whenshelookeddown,painshotupintothebackofherheadaswellasintoher faceandear.Shealsonotedthatshefeltsuddenelectricshocksthatwentfrom thebackofherheaddownintoherarms.Thepainwentawayassoonasshe raisedherhead.Whenaskedtodescribethecharacterofthepain,thepatient statedthatthepaininthebackofherheadfeltlikewhenyourleggoestosleep,a kindofpinsandneedlessensation.Shenotedthatthepaindownherarmswas different...thatitwaslikeanelectricshock.Whenaskedwhatmadeherpain worse,shestatedemphaticallythatitonlyoccurredwhenshelookeddown. Whenaskedwhatmadeherpainbetter,shesaid, “lookingup.” Thepatientrated herpainasa5ona1to10verbalanaloguescalewith10beingtheworstand 1beingthemildest.

Whenaskedaboutassociatedsymptoms,Mrs.Bravermannotedthatsince shebeganhavingthe “clunking” sensation,thatshewasalso “losingurine” and hadhadseveralaccidentswhenshedidn’tmakeittothebathroom.Whenquestioned,sheadmittedthatshenoticedthatherbottomwasnumbwhenshewiped aftergoingtothebathroom.

Onphysicalexamination,thepatientwasnormotensiveandafebrile.Hercognitionwasnormal,aswashernutritionalstatus.Bilateralcataractswerenotedin bothofhereyes.Hercardiopulmonaryexaminationwasunremarkable,aswas herabdominalexaminationTherewasnoperipheraledema.

Fig.1.1 Ulnardrift.(FromChungKC,PushmanAG.Currentconceptsinthemanagementofthe rheumatoidhand. JHandSurg.2011;36(4):736 747,Fig.4.)

Examinationofthehandsrevealedsevereulnardriftbilaterally(Fig.1.1).No activesynovitiswasnoted.Examinationofherfeetrevealedseverearthritis. Carefulexaminationofthecervicalspinerevealedcrepituswithflexion.At about30degreesofflexion,anaudibleandpalpableclunkwasappreciated.This clunkelicitedapositiveLhermitte’ssign.Whenthecervicalspinewasreturned totheneutralposition,thepatientnotedthattheshocklikepaincompletely disappeared.

Thepatient’sneurologicexaminationrevealedthatthepatienthadan unsteadygait.Examinationofthedeeptendonreflexesoftheupperandlower extremitiesrevealedhyperreflexiathroughout.Babinskisignwaspresent,as wasHoffman’ssign(Videos1.1 and 1.2 onExpertConsult).Clonuswasnotpresent.Sensoryexaminationrevealednoevidenceofperipheralorentrapmentneuropathy,buttherewasdecreasedrectalsphinctertoneandperinealnumbness.

KeyClinicalPoints

THEHISTORY

’ Chiefcomplaintof “itfeelslikemyheadisgoingtofalloff”

’ Recentonsetofa “clunking” sensationandsoundinMimi’suppercervicalspine

’ Pinsandneedles-likepaininposteriorocciput

’ Electricshocklikepainradiatingdownupperextremitiesbilaterally

’ Shortdurationofsymptomsassociatedwithflexionofcervicalspine

’ Symptomstriggeredbyflexionofcervicalspine

’ Symptomsrelievedbyreturningcervicalspinetoneutralposition

’ Urinaryandfecalincontinence

’ Perinealnumbness

’ Handclumsiness

Video1.1 DemonstrationoftheBabinskisign.

Video1.2 TheHoffman’sreflex.ThevideodemonstratesapositiveHoffman’sreflex.

THEPHYSICALEXAMINATION

’ Thepatientisscaredandupset

’ Patientthoughtshehadcancer

’ Bilateralhanddeformities ulnardrift(see Fig.1.1)

’ Decreasedrangeofmotionofaffectedjoints

’ Bilateralfootdeformities

’ Decreasedrangeofmotionofwristandfingers

’ Crepitusonflexionofcervicalspine

’ Suddenpalpableandaudible “clunk” withflexionofthecervicalspine

’ ElicitationofLhermitte’ssignwithflexionofthecervicalspine

’ Unsteadygait

’ Hyperreflexicdeeptendonreflexesthroughout

’ Babinskisignpresent(see Video1.1 onExpertConsult)

’ Hoffmansignpresent(see Video1.2 onExpertConsult)

’ Perinealnumbness

’ Decreasedsphinctertone

OTHERFINDINGSOFNOTE

’ Bilateralcataracts

’ Normalcardiovascularexamination

’ Normalpulmonaryexamination

’ Normalabdominalexamination

’ Noperipheraledema

WhatTestsWouldYouOrder?

Thefollowingtestswereordered:

’ Rheumatoidfactorandanticitrullinatedproteinantibodytiters

’ Plainflexionandextensionradiographsofthecervicalspinewithopen mouthviewstoevaluatetheodontoid.Iaskedthattheradiologytechnician usegreatcarewhenflexingandextendingthecervicalspine.

’ Computedtomography(CT)scanofthecervicalspinetodocumentpreciselythe relativepositionoftheodontoidrelativetotheforamenmagnumandtoidentify thepresenceofotherbonyabnormalities,includingsubaxialsubluxation,that mightbecontributingtotheneurologic symptoms.Ialsohopedtodefinebetter whatwascausingcompromise ofthesubarachnoidspace.

’ Magneticresonanceimaging(MRI)ofthecervicalspinetoidentifyretroodontoidpseudotumorthatmightbecompromisingthecervicalspinal cord.Ialsowantedtotryandevaluatetheconditionofthetransverse ligamentandidentifyanyedemaand/orerosionoftheodontoidprocess,

aswellasidentifyanyofthejoints.Ialsohopedtoascertaintheappearance ofthecervicalspinalcord.

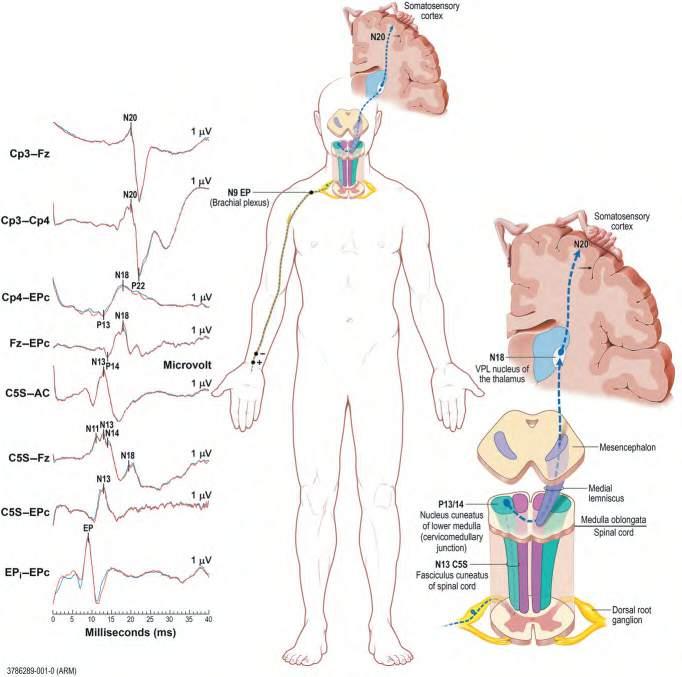

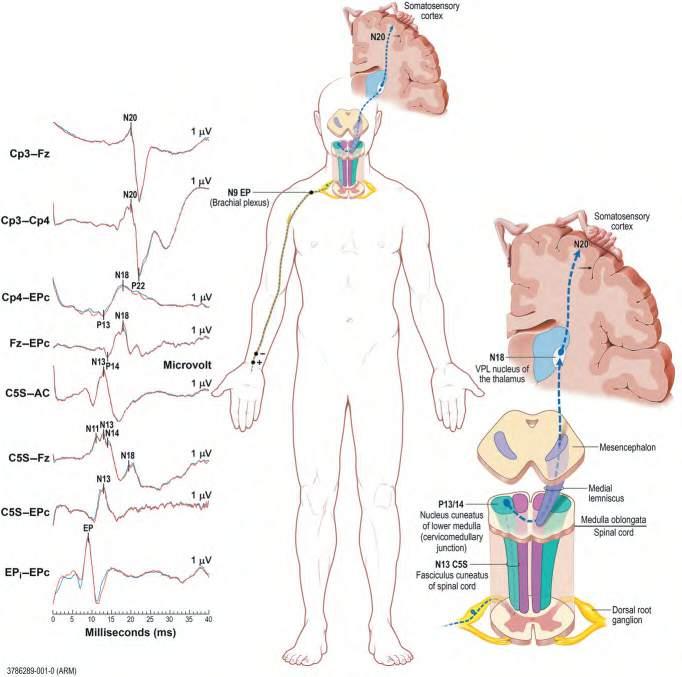

’ Somatosensory-evokedpotentialstoquantifythepresenceandextentof cervicalmyelopathy

TESTRESULTS

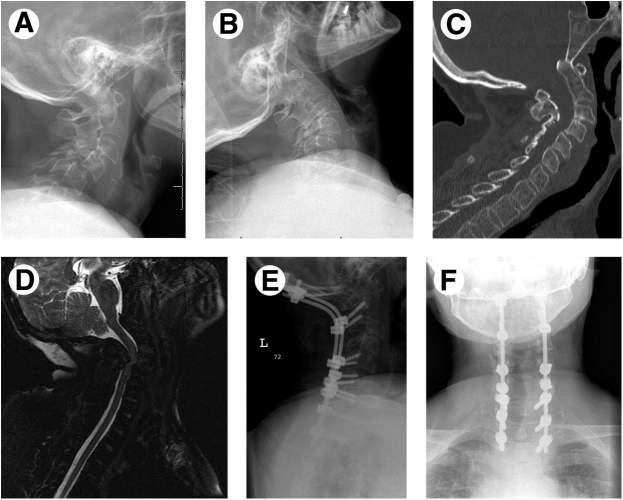

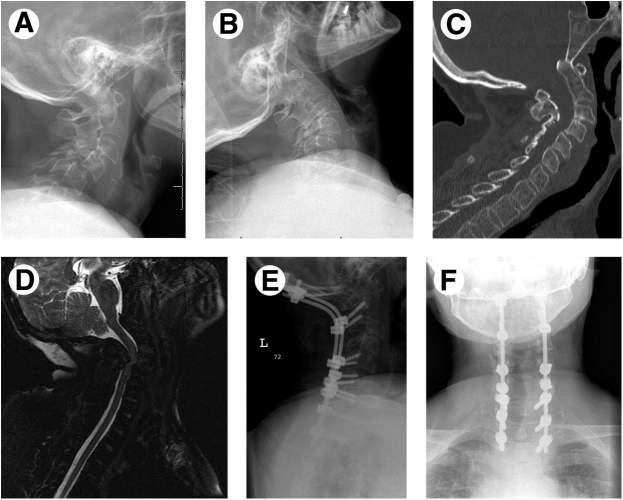

Asexpected,Mimi ’ srheumatoidfactorandantici trullinatedproteinantibody titersweremarkedlyelevated,confirmi ngmyclinicaldiagnosisofrheumatoid arthritis.GiventhedurationandextentofMimi ’ sdisease,itwasnotsurprisingthatallofherimagingresultswerem arkedlyabnormal.FlexionandextensioncervicalspineradiographsrevealedsignificantanteriorsubluxationofC1 onC2withananterioratlantodentali ntervalof5mm.Therewasextensive subaxialdiseasewithsubluxationofC3onC4anddiscspacenarrowing,anteriorosteophytosis,andfacetjointdiseaseofthelowercervicalspine( Fig.1.2 ).

HerCTscanrevealedatlantoaxialdislocationandcervicalkyphosis( Fig.1.3 ).

MRIscanofthecervicalspinerevealedatlantoaxialinstabilitywithproximal migrationoftheodontoidprocessandseverespinalcordcompressionat C3-C4.Thespinalcorddrapedovertheodontoidprocess( Fig.1.4 ). Somatosensory-evokedpotentialswereconsistentwithsignificantcervical myelopathy( Fig.1.5 ).

Fig.1.2 Plainlateralradiographsofthecervicalspineinflexion(A)andextension(B)revealsignificant anteriorsubluxationofC1onC2withananterioratlantodentalintervalof5mm.Thereisextensive subaxialdiseasewithsubluxationofC3onC4anddiscspacenarrowing,anteriorosteophytosis,and facetjointdiseaseofthelowercervicalspine.(FromDeQuattroK,ImbodenJB.Neurologicmanifestationsofrheumatoidarthritis. RheumDisClinNorthAm.2017;43(4):561 571,Fig.1.)

Fig.1.3 Computedtomography(CT)scanofthecervicalspineinanelderlyfemale.(A)Sagittalimage ofCTscanshowingatlantoaxialdislocationandcervicalkyphosis.(B)SagittalCTscanwithcutpassingthroughthefacets.Itshowstype1atlantoaxialfacetaldislocation.(FromGoelA,KaswaA,Shah A.Roleofatlantoaxialandsubaxialspinalinstabilityinpathogenesisofspinal “degeneration”—related cervicalkyphosis. WorldNeurosurg.2017;101:702 709,Fig.1A&B.)

ClinicalCorrelation—PuttingItAllTogether

Whatisthediagnosis?

’ Atlantoaxialinstabilitysecondarytorheumatoidarthritisinvolvingthe cervicalspine

TheScienceBehindtheDiagnosis

Theexactpathophysiologyofrheumatoidarthritisremainselusive,but recentresearchthathasledtothedevelopmentofnewerdisease-modifying agentssuggeststhatabnormalantigensproducedbysynovialcellselicitthe productionofmultipleautoantibodies.Themostimportantoftheseautoantibodiesappearstoberheumatoidfactorandanticitrullinatedproteinantibodies.Someinvestigatorsbelievethattheseantiautoantibodiesmayact synergisticallytocausethejointandorgansystemdamageassociatedwith rheumatoidarthritis(Fig.1.6).

Fig.1.4 Treatmentofcombineddeformity:AIandsubaxialinstability.This39-year-oldwomanwith RAhadadvancedinvolvementofthecervicalspinewithAIandsubaxialinstabilitythatledtorapidprogressivemyelopathywithquadriparesis.(A)Flexionand(B)extensionviewsdemonstratesubaxial instabilityatC4andC5.(C)AIisshownmoreclearly,withproximalmigrationoftheodontoidprocess. (D)AnMRIT2sagittalview,depictingseverecordcompressionatC3-C4withthecorddrapedover theodontoidprocess.ThispatientwastreatedwithanocciputtoT2fusionwithC2-C6laminectomy (E,lateralview;F,anteroposteriorview).Sherecoveredenoughstrengthinherupperandlower extremitiestobeabletowalk30feetwithawalker.(FromHohlJB,GrabowskiG,DonaldsonWF. Cervicaldeformityinrheumatoidarthritis. SeminSpineSurg.2011;23(3):181 187,Fig.3C&D.)

Approximately80%ofpatientssufferingfromrheumatoidarthritiswillhave involvementofthecervicalspine.Riskfactorsforcervicalspineinvolvement, whicharelistedin Box1.1,includefemalegender,presenceofmarkersindicatinghigherdiseaseactivity,longdurationofdisease,delayinuseofdiseasemodifyingdrugs,andyoungerageatdiseaseonset.Theclinicalsignificanceof thisinvolvementcanrangefromasymptomatictolifethreatening.Although rheumatoidarthritishasthepotentialtoaffectallelementsofthecervicalspine, theatlantoaxialjoint(C1-C2)ismostcommonlyaffected(Figs.1.7,1.8,and 1.9). Ifthepatient’srheumatoidarthritisispoorlymanaged,inflammatorydestructionofthejoint,transverseligament,anderosionoftheodontoidprocess mayoccurwithresultantatlantoaxialjointinstability(Figs.1.10 and 1.11). Rheumatoidarthritis-inducedretro-odontoidpseudotumorformationcanexacerbatecompressionofthecervicalspinalcordatthislevelbycausingdirectcompressionofthespinalcordandbyweakeningthetransverseandalarligaments,

Fig.1.5 Cervicalsomatosensory-evokedresponsetesting. (FromLevinK,ChauvelP. Handbook ofClinicalNeurology.Vol.160.Amsterdam:Elsevier;2019:Fig.35.1.)

Fig.1.6 Overviewofthefactorsthatmaycontributetothedevelopmentofrheumatoidarthritis.(From vanDelftMAM,HuizingaWJ.Anoverviewofautoantibodiesinrheumatoidarthritis. JAutoimmun. 2020;110.)

BOX1.1 ’ RiskFactorsforCervicalSpineInvolvementinRheumatoid Arthritis

’ Femalegender

’ Presenceofmarkersindicatinghigherdiseaseactivity

’ Positiverheumatoidfactor

’ Significantlyelevatederythrocytesedimentationrate

’ HighC-reactiveproteinlevel

’ Highdiseaseactivityscore

’ Longdurationofdisease

’ Delayinuseofdisease-modifyingagents

’ Youngerageatdiseaseonset

Transverse ligament

causingadditionalC1-C2instability(Figs.1.12 and 1.13).IftheC1-C2instability worsens,theodontoidprocessmaymigratesuperiorlyandimpingeonthe medullaandspinalcord(Fig.1.14).Complicatingtheclinicalpictureisthefact thatotherrheumatoidarthritis-inducedcervicalspineabnormalities,including subaxialsubluxationandfacetjointabnormalities,maycontributetothe patient’ssymptoms(see Figs.1.4 and 1.5).

Thephysicalfindingofulnardriftispathognomonicforrheumatoidarthritis (see Fig.1.1).Ulnardriftisthetermofartusedtodescribetwoseparaterheumatoidarthritis-inducedchangesofthemetacarpophalangealjoint:(1)ulnarrotationand(2)ulnarshift(Fig.1.15).Ulnarrotationistheresultofrotationofthe proximalphalanxintheulnaraxisrelativetothemetacarpalhead.Ulnarshiftis theresultofulnartranslationofthebaseoftheproximalphalanxrelativetothe metacarpalheads(see Fig.1.15).

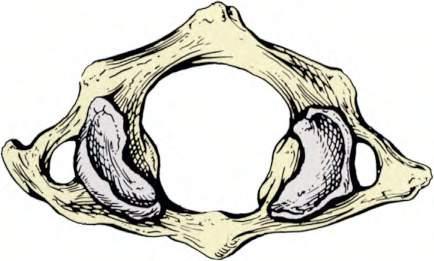

Atlantoaxial joint

Dens

Articular facet for dens of axis

Atlas (C1) Axis (C2)

Fig.1.7 Anatomyoftheatlantoaxialjoint.

Posterior arch

Transverse process

Superior articular facet of superior articular process

Foramen of the transverse process

Groove for the vertebral artery

mass

Anterior arch

Inferior articular process (lateral surface)

articular process

Inferior articular facet of inferior articular process

Fig.1.8 Atlas thefirstcervicalvertebra. Superior(A),inferior(B),and,lateral(C)viewsofthefirst cervicalvertebra theatlas.Superior(D),inferior(E),and,lateral(F)viewsofthefirstcervicalvertebra theatlas.(G)Close-up(superiorview)ofthelateralmassoftheatlas.Noticethecolliculusatlantisandsulcus(foveola)onthemedialsurfaceofthelateralmass.(FromCramerG,DarbyS. ClinicalAnatomyofthe Spine,SpinalCordandANS.3rded.St.Louis:Mosby;2014:135 209.)

Lateral

Posterior tubercle

Anterior tubercle

Superior

Posterior tubercle

Groove for the vertebral artery

Foramen of the transverse process

Foramen of the transverse process

Transverse process

(Continued).

Superior articular facet Transverse process

Inferior articular facet

Posterior ponticle

Arcuate (arcual) foramen

Posterior arch

Posterior tubercle

Anterior tubercle

Anterior tubercle

Anterior tubercle

Fig.1.8

MANAGEMENTANDTREATMENT

Posterior ponticle Transverse process

Superior articular facet

Oncethedamagecausedtotheatlantoaxialjointhasoccurred,thereisno effectivemedicationmanagement.Corticosteroidsmayprovidesome short-termsymptomaticrelief,butthereisnoevidencethattheycanprevent progressionofneurologicdeficitsoverthelongterm.Theuseofphysical modalitiesmayhelpprovidesymptomaticrelief.Asoftcervicalcollarmay helplimitflexionofthecervicalspine.Localheatmayprovidereliefofmusclespasms.Icepacksmayalsoprovidesymptomaticreliefoflocalizedpain andmusclespasm.

Onceatlantoaxialinstabilitysecond arytorheumatoidarthritis-induced damagetothecervicalspinehasoccurred,surgicalstabilizationisindicated. Studieshaveshownthatsurgicalstabi lizationnotonlyimprovesqualityof lifeandfunction,butalsoincreaseslifeexpectancyinthispatientpopulation. Surgicaloptionsavailableforthetreatm entofatlantoaxialinstabilityinclude (1)posteriortransarticularscrews,(2) posteriorsublaminarwiring,(3)Halifax clamping,and(4)screw-rodconstructs( Fig.1.16 ).Thechoiceofsurgical

Sulcus (foveola) atlantis Colliculus atlantis

Groove for the vertebral artery

Fig.1.8 (Continued).

Transverse process

Spinous process

Inferior articular facet

Lamina

Superior articular facet

Odontoid process

Superior articular facet

Groove for articulation with transverse ligament

Foramen of the transverse process

Fig.1.9 Axis thesecondcervicalvertebra. Superior(A),inferior(B),and,lateral(C)viewsofthe secondcervicalvertebra theaxis.Superior(D),inferior(E),and,lateral(F)viewsofthesecondcervicalvertebra theaxis.(G)Anterior-posterior “openmouth” viewoftheuppercervicalregionshowing theatlas,axis,andrelatedbonystructures.(FromCramerG,DarbyS. ClinicalAnatomyoftheSpine, SpinalCordandANS.3rded.St.Louis:Mosby;2014.)

Odontoid process (dens)

Lamina

Pedicle

Vertebral body A B

Odontoid process Superior articular facet

Odontoid process

Spinous process

Transverse process

Superior articular facet

Bifid spinous process

Inferior articular facet

Transverse process

Foramen of the transverse process

Vertebral body Foramen of the transverse process Inferior articular facet

(Continued).

Pedicle

Vertebral body

Fig.1.9

Fig.1.9 (Continued).

1. Odontoid process (dens)

2. C1 Lateral mass

3. C1 Transverse process

4. C1 Posterior arch

5. C2 Vertebral body

6. C2 Pedicle

7. C2 Spinous process

8. Odontoid-lateral mass space

9. Lateral atlanto-axial articulation

10. Styloid process

11. Unerupted third molar

A B C

Fig.1.10 (A)LateralradiographofthecervicalspineinextensionshowsnormalC1-C2alignment. (B)Oncervicalflexion,however,thereiswideningofthepredentalspaceowingtoC1-C2instability (double-headedarrow).(C)ThesagittalT1-weightedmagneticresonanceimageshowserosionofthe dorsalaspectoftheodontoidpeg.(FromWaldmanSD,CampbellRSD. ImagingofPain.Philadelphia: Saunders;2011:Fig24.1.)

techniquewillbedrivenbytheexperienceoftheoperatoraswellasthequality ofvertebralboneascorticosteroid-inducedosteoporosisisoftenpresent. Otherfactorsaffectingthechoiceofsurgicaltechniqueincludecoexistentsubaxialandatlanto-occipitalinstability.

Fig.1.11 Abnormalitiesofthecervicalspine:odontoidprocesserosions. Lateralconventional tomogramrevealsseveredestructionoftheodontoidprocess (arrows),whichhasbeenreducedtoan irregular,pointedprotuberance.(FromResnickD,KransdorfMJ. BoneandJointImaging.3rded. Philadelphia:Saunders;2004:244.)

Retro-odontoid pseudotumor formation

Anterior arch of atlas

Base of skull

Posterior arch of atlas

Odontoid process

Fig.1.12 Rheumatoidarthritis-inducedretro-odontoidpseudotumorformationcanexacerbate compressionofthecervicalspinalcordatthislevelbydirectcompressionofthespinalcordandby weakeningthetransverseandalarligaments,causingadditionalC1-C2instability.

Fig.1.13 MidsagittalT1-weightedmagneticresonanceimagingshowingpresenceofretro-odontoid softtissue.(FromRyuJII,HanMH,CheongJH,etal.Theeffectsofclinicalfactorsandretroodontoidsofttissuethicknessonatlantoaxialinstabilityinpatientswithrheumatoidarthritis. World Neurosurg.2017;103:364 370,Fig.2.)

Fig. 1.14 Gross anatomic specimen of the base of the skull of a patient with severe rhematoid arthritis. Looking down into the foramen magnum from above, a bony protuberance can be seen. This upward dislocation of the odontoid process of the axis pushes the medulla and spinal cord backward. (From Kovacs G, Alafuzoff I. Handbook of Clinical Neurology. Vol. 145. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2017: Fig. 29.9.)