Detailed Contents

Preface

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Chapter 1 Introduction to Organization Design

Organization Design Defined

Organization Design Is a Set of Deliberate Decisions

Organization Design Is a Process

Organization Design Assumes a Systems Approach to Organization

Organization Design Is Based on the Organization’s Strategy

Organization Design Encompasses Multiple Levels of Analysis

Organization Design Is More Than Organizational Structure

Organization Design Is an Interdisciplinary Field of Research and Practice

History of Organization Design

1850s to Early 20th Century

1910s to World War II

Post–World War II to 1960s

1970s and 1980s

1990s and 2000s

The Case for Organization Design Today

Design Affects Performance

Design Is a Leadership Competency

Today’s Organizations Experience Significant Design

Challenges

Changing Nature of Work

Globalization

Technology

Organization Designs Today

Today’s Focus on Agility Is a Design Issue

Summary

Questions for Discussion For Further Reading

Chapter 2 Key Concepts and the Organization Design Process

Key Concepts of Organization Design

The STAR Model of Organization Design

Alignment, Congruence, and Fit

Contingency Theory and Complementarity

Trade-offs and Competing Choices

Reasons to Begin a Design Project

Performance Is Suffering Because of Misalignment

The Strategy Changes

There Is a Shift in Environment or External Context

There Are Internal Changes to Structures, Functions, or Jobs

The Organization Has Made One or More Acquisitions

The Organization Expands Globally

There Are Cost Pressures

There Is a Leadership Change

Leaders Want to Communicate a Shift in Priorities

The Design Process

Scope, Approach, and Involvement

Top Down

Bottom Up

Deciding Who Is Involved

Benefits of a More Participative Approach

Choosing the Right Participants

Design Assessments and Environmental Scanning

Design Assessments: Gathering Data

Interviews

Focus Groups

Surveys and Questionnaires

Observations and Unobtrusive Measures

Using the STAR Model as a Diagnostic Framework

Environmental Scanning: STEEP and SWOT

Evaluating the Current Design

Evaluating Alignment in the Design

Evaluating Strategy/Task Performance and Social/Cultural

Factors in the Design

Goold and Campbell’s Nine Design Tests

Design Criteria and Organizational Capabilities

Benefits of Design Criteria

How to Develop and Use Design Criteria in the Design Process

Summary

Questions for Discussion

For Further Reading

Exercise

Case Study 1: The Supply Chain Division of Superior Module

Electronics, Inc.

Chapter 3 Strategy

Why Strategy Is an Important Concept for Organization Design

What Is Strategy?

Sustainable Competitive Advantage

Activity Systems and Strategic Trade-offs

Strategy Rests on Unique Activities

Strategy Requires Trade-offs

Types of Strategy

Porter’s Generic Strategies

Cost Leadership

Differentiation

Focus

Treacy and Wiersema’s Value Disciplines

Operational Excellence

Product Leadership

Customer Intimacy

Miles and Snow’s Strategy Typology

Defenders

Prospectors

Analyzers

Reactors

Stuck in the Middle

Key Concepts

Porter’s Five Forces Model

Threat of New Entrants

Bargaining Power of Buyers

Bargaining Power of Suppliers

Threat of Substitute Products or Services

Rivalry Among Existing Competitors

Core Competencies

Blue Ocean Strategies and the Strategy Canvas

New Trends in Thinking About Strategy

Summary

Questions for Discussion For Further Reading

Exercises

Chapter 4 Structure

Connecting Strategy and Structure

How Strategy Influences Structure

How Structure Influences Strategy

Dimensions of Organization Structure

Departmentalization or Groupings

The Purpose of Department Groupings

Structure Options

Functional Structure

Product Structure

Customer/Market Structure

Geographic Structure

Process Structure

Network Structure

Front–Back Structure

Matrix Structure

Advantages and Disadvantages of Structure Types

Choosing a Structure and Evaluating the Options

1. To what extent does the option maximize the utilization of resources?

2. How does grouping affect specialization and economies of scale?

3. How does the grouping form affect measurement and control issues?

4. How does the grouping form affect the development of individuals and the organization’s capacity to use its human resources?109

5. How does the grouping form affect the final output of the organization?

6. How responsive is each organization form to important competitive demands?110

Principles of Structure

Shape/Configuration: Span of Control and Layers

Distribution of Power: Centralization/Decentralization

Division of Labor and Specialization

Connecting Strategy and Structure: Revisited

Summary

Questions for Discussion

For Further Reading

Exercises

Chapter 5 Processes and Lateral Capability

Lateral Capability: The Horizontal Organization

Why Developing Lateral Capability Is So Difficult

Benefits and Costs of Lateral Capability

Forms of Lateral Capability

Networks

Cultivating Networks

Shared Goals, Processes, and Systems

Teams

Cross-Functional Teams

Integrator Roles

Matrix Organizations

Making the Matrix Work

Getting the Level of Lateral Capability Right

How to Decide Which Form to Use

Governance Models and Decision Authority

Governance and Planning Processes

Decision-Making Practices

Enablers for Successful Lateral Capability

Summary

Questions for Discussion

For Further Reading

Exercise

Case Study 2: Collaboration at OnDemand Business Courses, Inc.

Chapter 6 People

Case 1: Coca-Cola

Case 2: AT&T

Case 3: Lafarge

Traditional Approaches to People Practices

A Strategic Approach to People Practices

Key Positions and the Differentiated Workforce

“A” Positions and Pivot Roles

“A” Positions: Strategic

“B” Positions: Support

“C” Positions: Surplus

Talent Identification and Planning

Talent Identification: Focus on Potential

Talent Planning, Pipelines, and Talent Pools

Career Development

The Classic View: Stages of the Career

The Contemporary View: Boundaryless Careers

Career Lattice Versus Career Ladder

Talent Development and Learning Programs

New Forms of Learning Versus Formal Training

Development Through Experiences

Performance Management

Strategic Analysis and Designing the People Point

Global Considerations

Summary

Questions for Discussion

For Further Reading

Exercise

Chapter 7 Rewards

Approaches to Rewards

Misaligned Rewards: When Rewards Fail

Unethical Behavior

Counterproductive Behavior

Conflict and Competition

Slower Change and Resistance

Why Designing Rewards Is So Challenging

Motivation

Expectancy Theory, Goal Setting, and Equity

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivation

Motivation-Hygiene Theory

Intrinsic Motivation and Extrinsic Rewards

Motivational Impact of Job Design

Metrics and the Balanced Scorecard

Rewards Strategy and Systems

Basis for Rewards

Types of Rewards

Designing a Rewards System That Works

Rewards, Strategy, and Other STAR Points

Summary

Questions for Discussion

For Further Reading

Exercises

Case Study 3: A Talent and Rewards Strategy at EZP Consulting

Chapter 8 Reorganizing, Managing Change, and Transitions

Change and Resistance

Personal Transitions

A Change and Transition Planning Framework

Resistance

Reorganizing and Transition Planning

Structure, Reporting Relationships, and Staffing

Pace and Timing

Scope and Sequencing

Communication

Feedback and Learning

Organizational Culture and Design

What Is Culture?

Understanding Culture: Competing Values Framework

Leadership and Organization Design

Leadership’s Role During the Design Process

Leadership’s Role During Change

Design and Leadership Development

Leading New Teams

Summary

Questions for Discussion

For Further Reading

Exercise

Case Study 4: Reorganizing the Finance Department: Managing

Change and Transitions245

Chapter 9 Agility

Why Agility Is Important Today

Continuous Design and Reconfigurable Organizations

What Agility Means

“Change-Friendly” Identity

Sensing Change

Agile Strategy

Zara and Transient Advantages

Rapid Prototyping and Experimentation

Agile Structure

Structure and the “Dual Operating System”

Holacracy

Agile Processes and Lateral Capability

Agile Teams

Global Collaboration

Partnerships and Collaborative Networks

Agile People

Learning Agility

Leadership Agility

Agile Rewards

Agility and Stability

Summary

Questions for Discussion

For Further Reading

Chapter 10 Future Directions of Organization Design

Emerging Beliefs About Organizations and Design

Work Trends Create Design Challenges

Design Challenges Shape Design Process

Future Trends in Organization Design Theory and Practice

Big Data

Digital Technologies, Platforms, and Business Models

Sustainability and the Triple Bottom Line

Changes in Organization Design Practice: A Case Study of Royal Dutch Shell

The Organization Design Practitioner Role and Skills

Summary

Questions for Discussion For Further Reading

Appendix

Organization Design Simulation Activity

Part I: Strategy

Your Profile

Your Mission: Create an Organization and Explain Its Strategy

Part II: Structure and Processes and Lateral Capability

Structure

Processes and Lateral Capability

Part III: People and Rewards

People Practices

Reward Practices

Part IV: Reorganizing References

Index

Sara Miller McCune founded SAGE Publishing in 1965 to support the dissemination of usable knowledge and educate a global community. SAGE publishes more than 1000 journals and over 800 new books each year, spanning a wide range of subject areas. Our growing selection of library products includes archives, data, case studies and video. SAGE remains majority owned by our founder and after her lifetime will become owned by a charitable trust that secures the company’s continued independence.

Los Angeles | London | New Delhi | Singapore | Washington DC | Melbourne

Preface

Observers of contemporary organizations continue to enumerate the enormous challenges facing leaders today. Leaders are required to operate with global teams to serve global customers; to cope with increased competitive pressures from rivals large, small, new, and unexpected; to innovate in agile ways to secure even a short-term competitive advantage; and to do all of this with fewer resources than ever before. Organizations are developing increasingly complex designs to account for the collaboration required in today’s rapidly changing, global, dynamic environment. In many ways, organization design is a core leadership competency to address these challenges. Yet while dozens of publications introduce students and business leaders to the foundations of strategy or talent management, there are few introductory publications in the field of organization design.

Organization design is a complex subject that can be intimidating to newcomers. Students who come to the field of organization design through strategy find themselves quickly mired in complex discussions of four-sided matrix designs or virtual organizations. These frameworks seem to forget that people design organizations and execute on their strategies. Other students who come to design from the people side or human resources discipline tend to become lost in discussions of strategy and complex global operating models. Practicing organization design requires an understanding of industry trends and strategic positioning as well as an understanding of organizational behavior, organizational change, and even psychology.

Organization design is an interdisciplinary field of theory and practice. Students and managers who apply design concepts need to not only understand design theory, but how to translate that theory into practice. These topics can be difficult to understand, much less to apply in an ever changing contemporary environment and adapt to the unique needs of any given organization.

The purpose of this book is to expose you to not only classic and traditional but also contemporary and innovative organization design concepts, and to do

so in a way that is accessible to a novice. Design practitioners come in many forms: You might be a leader looking to enhance your knowledge of organization design so that you can create a department or team that is aligned with the organization’s strategy and removes barriers to performance. You might be a human resources (HR) professional or organization development consultant whose role is to work with leaders in your organization on their organization design challenges and to facilitate them through a design process. In any case, the concepts, theories, and approaches in this book are intended to provide an introduction to the field of organization design and the choices that must be weighed. You will find the term organization designer throughout the book to emphasize these different roles, from leader to consultant to HR practitioner.

Consistent with the view that there is no one right organization design, you will not find any particular design advocated or an attempt to push the latest fad designs. Instead, it is important that as managers, students, and practitioners we have an appreciation for the thought process involved in organization design. It is more helpful to develop an understanding of the choice points, trade-offs, considerations, and consequences of any design alternative than to adopt a design just because it is popular. By learning more about organization design in this way, you will be a better observer of organization design challenges and a better critic of proposed designs and their consequences. You will also be in a position to recommend alternatives that are more likely to result in the objectives you are trying to reach.

Learning Objectives

In this chapter you will learn What organization design is and how it is defined. The history and development of the field of organization design. Why organization design is relevant as a subject of study and practice today.

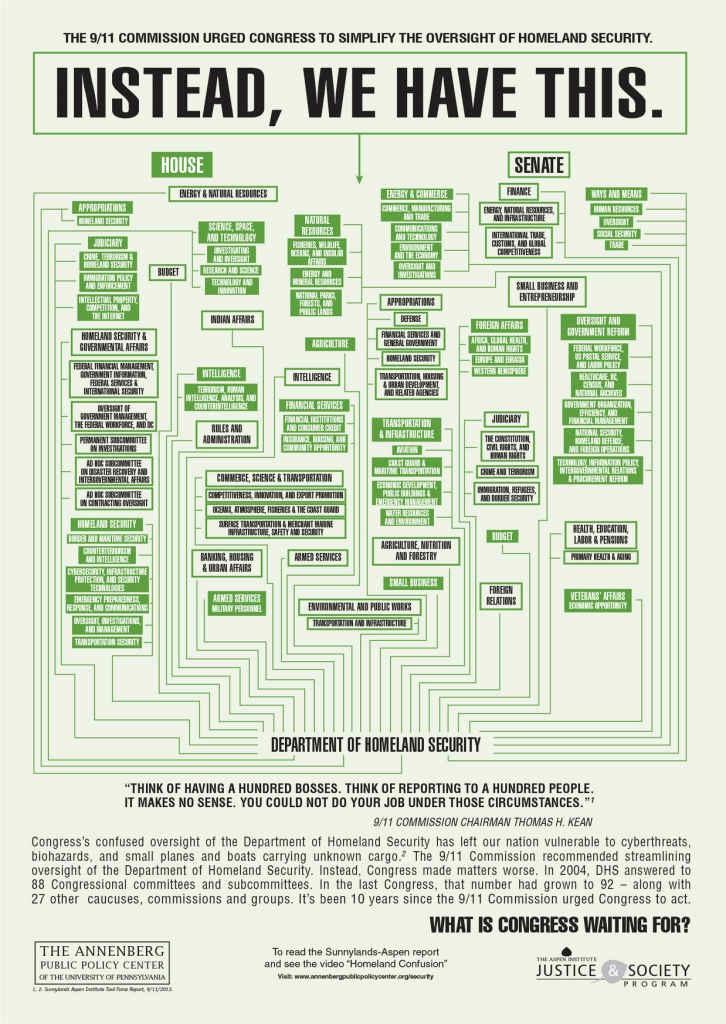

On July 22, 2014, a full-page ad appeared in the New York Times (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1

Source: Annenberg Public Policy Center of the University of Pennsylvania. (2014, July 22). Instead, we have this. The New York Times.

The ad featured a dizzying array of organizational boxes and lines depicting the complex interfaces required to manage the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). Just over one year after the attacks of September 11, 2001, Congress established the DHS as a new department formed from all or some of 22 different government agencies. The intent was to bring together disparate practices and groups to remedy “the current confusing patchwork of government activities into a single department whose primary mission is to protect our homeland” (Proposal to Create the Department of Homeland Security, 2002, p. 1). The initial proposal promised a “clear and efficient organizational structure” (p. 2). This was no small achievement, as the U.S. federal government is a very large and complex organization comprising more than 2.7 million workers in addition to almost 1.5 million military personnel, according to the U.S. Office of Personnel Management. More than 240,000 of these employees work in the DHS.

A report that was subsequently produced more than 10 years after the establishment of the new department lamented the complexity of this new model. It noted that the DHS was required to report to almost 100 different congressional committees and subcommittees. Whereas a government agency such as the Department of State might report predominantly to the Foreign Affairs committees in the House and Senate, DHS was faced with oversight from dozens of committees that had overlapping and perhaps even competing authority and jurisdictions. On the one hand, one could argue that this complexity created too many interactions that resulted in duplicative, wasted effort. Are employees spending time producing similar presentations and reports and sitting in meetings that may not be the best use of their time? On the other hand, this might be exactly the model required to manage the complex threats in areas as diverse as cybersecurity and bioterrorism. Perhaps these multiple connections create opportunities for collaboration and information sharing that otherwise would not exist? Whether this is the right model or not for this organization, the ad brought issues of organization design to national attention in a way that most Americans had probably never

considered about the federal government. It introduced issues in a way that most people could relate to and begin to debate.

For example, consider these common questions that organizational leaders must address:

How much complexity in an organization is necessary and helpful to respond to a complex and rapidly changing environment? When a new set of activities is introduced to an organization, should a new division be established, or should the work be assigned to existing divisions?

What is the ideal number of committees and meetings that does not waste time but encourages the right coordination and information sharing?

Despite the number of organizations we interact with on a regular basis, including schools, churches, hospitals, and businesses large and small, most of us rarely consider their designs consciously until something is not working effectively. You might be a frustrated customer at the mercy of a poor organization design when you had a problem with a company and heard from every employee that your problem was not the responsibility of that department. You might wonder why the same insurance company you have for auto insurance and life insurance cannot seem to share information between the different divisions or why two doctors in the same office do not have similar billing practices. In addition, consider your place of employment. You may have noticed inefficiencies in how your department operates, or you might have seen what happens when work falls through the cracks because it was no one’s responsibility. You may have been part of a merger with or acquisition by another company, or you might have experienced the confusion that resulted from your own department being divided or integrated with another internally.

All of this is to say that you have certainly experienced organization design even if you have never before considered the issues and decision points in an organization’s design. The purpose of this book is to introduce you to the field of organization design, an area of academic research and professional practice devoted to the conscious design of organizations of all forms, from nonprofit organizations to for-profit companies and local, state, and national

governments.

Organization Design Defined

Over the decades of its history, organization design has been defined in different ways. Let’s look at three widely respected definitions of organization design:

“Organization design is conceived to be a decision process to bring about a coherence between the goals or purposes for which the organization exists, the patterns of division of labor and interunit coordination and the people who will do the work” (Galbraith, 1977, p. 5).

“Organization design is the making of decisions about the formal organizational arrangements, including the formal structures and the formal processes that make up an organization” (Nadler & Tushman, 1988, p. 40).

“Organization design is the deliberate process of configuring structures, processes, reward systems, and people practices and policies to create an effective organization capable of achieving the business strategy” (Galbraith, Downey, & Kates, 2002, p. 2).

You may have noticed a number of consistent themes included in each of these definitions.

Organization Design Is a Set of Deliberate Decisions

All organizations are designed (or have a design), even if they were not designed that way intentionally. In addition, all organizations evolve and change, and as they do, the design usually changes as well. Sometimes these changes are thoughtfully considered. An executive leaves the company and two existing units with complementary capabilities get combined. The company decides to enter into a new market and establishes a separate division to manage the product development, marketing, and sales of the new products for that market. At other times, the organization may be changing without conscious attention. Customer demands may grow to the point that the existing customer service organization cannot effectively manage the