Aquaculture

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aquaculture

Optimal dietary protein level for pacu Piaractus mesopotamicus juveniles reared in biofloc system

Dara Cristina Pires a , Gabriel Artur Bezerra a , Andr´ e Luiz Watanabe b , Celso Carlos Buglione Neto b , ´ Alvaro Jos´ e de Almeida Bicudo c , Hamilton Hisano d, *

a Programa de Pos-Graduaçao em Zootecnia, Universidade Estadual de Mato Grosso do Sul, Aquidauana, MS, Brazil

b Itaipu Binacional, Foz do Iguaçu, PR, Brazil

c Universidade Federal do Paran´ a, Palotina, PR, Brazil

d Embrapa Meio Ambiente, Jaguariúna, SP, Brazil

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Aquaculture system

Diet

Hematology

Microbial protein

Protein requirement

ABSTRACT

This study evaluated the effects of dietary protein levels on growth performance, hematological and biochemical parameters, carcass and fillet yields, somatic indexes, and body chemical composition of pacu juveniles reared in a biofloc system over a 60-day period. Five isoenergetic (13.4 MJ kg 1 DE) experimental diets were formulated with increasing crude protein (CP) levels (194, 232, 278, 316, and 359 g kg 1). Three hundred fish weighing an average of 3.16 ± 0.3 g were randomly distributed in 20 experimental tanks (50 L) at the rate of 15 fish per replicate and fed experimental diets until apparent satiation four times a day. The experimental design was completely randomized with five treatments and four replicates. Weight gain (WG), thermal growth coefficient (TGC), protein productive value (PPV), and fillet yield (FY) showed quadratic effect (P < 0.05) as protein levels increased. Feed consumption (FC) and carcass yield (CY) showed a linear growth (P < 0.05), while protein efficiency ratio (PER) decreased linearly (P < 0.05) as protein levels increased. The hematological and biochemical parameters did not differ between treatments (P > 0.05), except for the hematocrit. However, blood parameters remained at normal range for this species. The optimal dietary protein level was estimated at 310 g kg 1 CP (≈ 268 g kg 1 DP) for the best growth of pacu juveniles reared in the biofloc system.

1. Introduction

Pacu or Piaractus mesopotamicus is an omnivorous fish from the Characiformes order found in Paran´ a, Uruguay, and Paraguay rivers, as well as their affluents (Petrere Júnior, 1989). This species is part of the predominant group of freshwater fish in South America with commercial importance to fisheries and aquaculture in several countries such as Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, and Peru (Merola, 1988; Valladao et al., 2016).

In Brazil, pacu and other species of Serrasalmidae, such as pirapitinga (Piaractus brachypomus), tambaqui (Colossoma macropomum), and their interspecific hybrids are the main native species, representing 9.8% of fish production from aquaculture in 2019 (IBGE, 2020). Currently, P. mesopotamicus is mainly farmed in ponds, with a small portion farmed in net cages. Improving balanced and low-cost diets and management practices are essential to expand pacu production since intensive farming increases production costs, dependence on

manufactured diets, and environmental impact (Bolivar et al., 2010).

The biofloc technology (BFT) system has been proposed as a sustainable alternative for intensive aquaculture because it boosts productivity, decreases water use, and effluents production through nutrient recycling by heterotrophic microorganisms (Avnimelech, 2014). Heterotrophic bacteria aggregates in microbial flocs assimilate ammonia in the water systems and convert it into microbial protein, which can be used as a complementary food for filter-feeding species or to maintain water quality and increased productivity (Khanjani and Sharifinia, 2020).

Protein is the most expensive macronutrient in aquafeeds, and reducing dietary protein levels without impairing fish performance improves the diets economically and environmentally. Thus, determining protein requirements is usually one of the first steps in selecting new species for aquaculture, especially in traditional intensive production systems (e.g., RAS, raceways). Dietary protein requirements for the best growth of pacu in the initial phase vary from 270 (Bicudo et al.,

* Corresponding author at: Embrapa Meio Ambiente, Rodovia SP 340, Km 127,5, 13918-110, C.P. 69 Jaguariúna, SP, Brazil.

E-mail address: hamilton.hisano@embrapa.br (H. Hisano).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738274

Received 9 December 2021; Received in revised form 14 April 2022; Accepted 17 April 2022

Availableonline20April2022

0044-8486/©2022ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

Table 1

Formulation, proximate and estimated composition of experimental diets (based on dry matter).

Ingredients

Proximate and estimated composition

a Composition of the vitamin-mineral premix (Tectron, Toledo, Paran´ a, Brasil), kg 1 diet: vitamin A 1.000.000 UI, vitamin D3 500.000 UI, vitamin E 20.000 UI, vitamin K3 500 mg, vitamin B1 1.900 mg, vitamin B2 2.000 mg, vitamin B6 2.400 mg, vitamin B12 3.500 μg, vitamin C 25 g, niacin 5.000 mg, pantothenic acid 4.000 mg, folic acid 200 mg, biotin 40 mg, manganese 7.500 mg, zinc 25 g, iron 12,5 g, copper 2.000 mg, iodine 200 mg, selenium 70 mg, BHT 300 mg.

b Estimated values based on digestible nutrients compiled by Abimorad and Carneiro (2004) and Bicudo et al. (2013).

c Estimated values calculated based on Rostagno et al. (2017)

d Analyzed values according to AOAC (2005)

2010) to 326 g kg 1 (Khan et al., 2020) when farmed in clearwater systems (no endogenous protein sources). However, Serrasalmidae species are efficient filter-feeding fish, especially in the early stages (Vidal Júnior et al., 1998).

Microbial biomass of bioflocs has high nutritional value consisting of 200–450 g kg 1 crude protein, 150–600 g kg 1 ash, 10–80 g kg 1 lipids, 10–150 g kg 1 fiber, and 180–350 g kg 1 carbohydrates (El-Sayed, 2020). Furthermore, its nutritional profile presents great nutrient diversity depending on floc size and organic carbon sources (Wei et al., 2016). According to Avnimelech and Kochba (2009), tilapia can uptake up to 240 mg N kg 1 of microbial biomass, equivalent to approximately 25% of protein of the diet. Due to the utilization of the microbial protein of BFT, dietary crude protein can be reduced by 5 to 11% for Nile tilapia juveniles (Silva et al., 2018; Hisano et al., 2019).

In addition to the nutritional benefits, studies have shown that microbial biomass has probiotic properties (Romano et al., 2020) and bioactive substances (Azimi et al., 2022), which improves digestive enzymes activity and feed utilization (Long et al., 2015) and enhances fish immune and antioxidative responses (Shourbela et al., 2021).

Considering pacu's filter-feeding nature and the potential use of microbial biomass as a complementary protein source, previously determined protein requirements in clear water can be excessive due to the continuous availability of endogenous food in the BFT system. Thus, this study evaluated the effects of protein levels on growth performance, hematological and biochemical parameters, somatic indexes, and carcass and fillet yields of pacu juveniles reared in BFT.

2. Material and methods

2.1.

Ethical statement

The study was carried out at the Itaipu Binacional Fish Culture Station, Foz do Iguaçu, PR, Brazil. All experimental procedures followed the Ethical Principles in Animal Research and were approved by the Committee for Ethics in Animal Experimentation of the Federal University of Paran´ a/Palotina (Protocol: 45/2019).

2.2. Experimental diets

Five isoenergetic (13.4 MJ kg 1 DE) experimental diets were formulated with increased crude protein (CP) levels (194, 232, 278, 316, and 359 g kg 1) based on pacu's protein requirement (270 g kg 1 CP) in clear water determined by Bicudo et al. (2010). Experimental feedstuffs were analyzed prior to formulation for certification and control, showing the following values for soybean meal: 880 g kg 1 dry matter (DM), 427.2 g kg 1 CP, 17.24 MJ kg 1 crude energy (CE), 19.5 g kg 1 ether extract (EE), 53 g kg 1 ash (A); corn: 890 g kg 1 DM, 87 g kg 1 CP; 16.48 MJ kg 1 CE, 40.8 g kg 1 EE, 11 g kg 1 A; wheat middlings: 885 g kg 1 DM, 151.2 g kg 1 CP, 16.42 MJ kg 1 CE, 34 g kg 1 EE, 43 g kg 1 A and poultry offal meal: 920 g kg 1 DM, 577 g kg 1 CP, 19.88 MJ kg 1 CE, 142 g kg 1 EE, 148 g kg 1 A.

Digestible energy (DE) and digestible protein (DP) were estimated according to the apparent digestibility coefficients of macronutrients and gross energy of several feedstuffs used in pacu diets (Abimorad and Carneiro, 2004; Bicudo et al., 2013). Lysine and methionine levels were adjusted based on the CP content maintaining the amino acid to CP ratio. Protein from animal feedstuff was fixed at 30% of the total dietary protein, so the content of poultry viscera meal increased according to the graded levels of CP in experimental diets (Table 1).

Feedstuffs were ground in a mill (Model MA340, Moinhos Viera Ltda., Tatuí, SP, Brazil) to reach 0.3 mm. Further, they were weighed, homogenized, and mixed in a Y-mixer (Model MA201, Marconi Laboratory Equipment Ltda., Piracicaba, SP, Brazil), moistened with approximately 20% of water, and processed in a single-screw extruder (Model EX-30, Exteec, Ribeirao Preto, SP, Brazil) through 1.5 mm diameter die at 90 ◦ C to reach 3 mm diameter final pellets. Diets were dried in a forced air oven (55 ◦ C) for 24 h (Model MA035/1, Marconi Laboratory Equipment Ltda., Piracicaba, SP, Brazil) and dried pellets were packed in plastic recipients to be stored under refrigeration (4 ◦ C) until its use.

2.3. Fish, experimental conditions and feeding

Pacu fingerlings P. mesopotamicus were obtained from a commercial fish farm (Dal Bosco Fish Farming, Toledo, PR, Brazil) and then acclimated to the experimental conditions in a 5000-L stabilized biofloc circular polyethylene aerated tank for seven days. Meanwhile, they were fed a commercial diet with 460 g kg 1 crude protein (min.), 120 g kg 1 moisture (max.), 80 g kg 1 crude lipid (min.), 30 g kg 1 fiber, and 140 g kg 1 ash (max.) (Supra Alisul Alimentos S.A, Rio Claro, SP, Brazil) twice daily (08.00; 17.00) at 3% body weight per day.

The biofloc technology (BFT) system was assembled using the macrocosm-microcosm model (Wasielesky Júnior et al., 2006). Before the experimental trial, 1 L of water from the stabilized BFT tank used to acclimate the fish was inoculated in a macrocosm BFT tank for 30 days to ensure maturation and stability of the system. Pacu fingerlings (n = 300; 3.16 ± 0.3 g; 15 fish/experimental unity) were individually weighed and randomly distributed into 20 rectangular polyethylene tanks (50-L microcosms) connected to a circular polyethylene tank (310L macrocosm) for continuous water distribution to the experimental units with individual aeration and recirculation rate at 250 L h 1 .

Fish were fed four times a day (8 h:00; 11 h:00; 14 h:00, and 17 h:00) until apparent satiety during 60 days. Diets of each experimental unit

D.C.

were weighed daily to estimate consumption, and biometrics were performed every 30 days. The experimental design was randomized with five treatments (190, 230, 270, 310, and 350 g kg 1 CP) and four replicates.

The carbon (C): nitrogen (N) ratio was kept at 15:1, and sugar cane was used as a carbon source, as recommended by Avnimelech (1999) During the experimental period, water lost by evaporation was restored, but with no complete renovation in the system.

2.4. Water quality

Temperature, dissolved oxygen (DO), and pH were monitored two times per day (07:30 and 16:00) with a multiparameter instrument (Model Professional Plus, YSI, New York, USA). Total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), nitrite (NO2 ), nitrate (NO3 ), and alkalinity were analyzed twice a week, using a commercial kit and photometer (Hanna Instruments, New Deli, India). Total suspended solids (TSS) (APHA, 2012), sedimentable solids (SS) (Avnimelech, 2014), and chlorophyll (Lorenzen, 1967) content were determined weekly.

The physical-chemical water quality parameters of the BFT system were kept at the recommended levels for the species and development stage (Proença and Bittencourt, 1994). During the experimental trial, dissolved oxygen, pH, and temperature were 7.45 ± 0.41 mg.L 1 , 8.17 ± 0.31 and 27.2 ± 2.86 ◦ C, respectively. TAN was 0.32 ± 0.12 mg.L 1 , nitrite 2.62 ± 3.17 mg.L 1 , and nitrate 18.98 ± 15.51 mg.L 1 Alkalinity remained at 183.11 ± 34.68 mg.L 1 CaCO3. TSS and SS were 284.8 ± 147.22 mg.L 1 , and 23.79 ± 16.34 mL.L 1 , respectively. Chlorophyll is an indicator of phytoplankton biomass in the BFT and was quantified at 228.14 ± 140.87 μg/L, with a cell count of 5.1 × 104 ± 1.33.

2.5. Growth performance, somatic indexes and body yield

At the end of the growth trial, fish were fasted for 24 h and individually weighed to determine survival rate (SR), weight gain (WG), feed intake (FI), apparent feed conversion ratio (AFCR), protein efficiency ratio (PER), uniformity (U), thermal growth coefficient (TGC), and protein productive value (PPV), (NRC, 2011; Hisano et al., 2019; Couto et al., 2018; Oliveira et al., 2021).

To determine whole-body composition and PPV, 40 fish were

euthanized by benzocaine overdose (500 mg/L) after fasting for 24 h and then ground, homogenized, and stored at 4 ◦ C for chemical analysis. The initial total whole-body composition was determined using 20 fish from the original population. Each treatment collected liver, viscera, and fat from 24 fish to calculate the hepatosomatic index (HSI) and mesenteric fat index (MFI). After evisceration, fish were weighed to determine the skinless fillet yield (FY) and the carcass yield (CY) with the head.

2.6. Hematological and biochemical parameters

After the growth trial, 24 fish (6 per treatment) were randomly collected and anesthetized with benzocaine (50 mg/L) for blood sampling via caudal puncture with heparinized (5000 IU) syringes. The samples were placed in microtubes (1.5 mL) and refrigerated (4 C) for further analysis.

Hemoglobin (Hb) was determined by the cyanmethemoglobin method (Collier, 1944) using the commercial kit (Labtest, Lagoa Santa, MG, Brazil) in a semi-automatic analyzer (Model SB-190 Medsystem, Celm, Sorocaba, SP, Brazil). Hematocrit (Ht) was performed by microhematocrit method (Ranzani-Paiva et al., 2013) in a centrifuge (Model NI 1807, Nova Instruments, Piracicaba, SP, Brazil) at 10,000 rpm for 5 min and subsequent read on a graduated scale. The total plasma protein content (PPT) was determined with a refractometer (Hand-Held Pocket, ATAGO, Vantaa, Finland). Red blood cell (RBC) counts were performed after blood dilution (1:200) (Ranzani-Paiva et al., 2013) in formalin-citrate solution using a Neubauer hemocytometer. The mean corpuscular volume (MCV) and mean corpuscular hemoglobin concentration (MCHC) hematimetric indexes were also calculated (Ranzani-Paiva et al., 2013).

Previously collected blood samples were centrifuged for 10 min at 3500 rpm (Model LS-4, Celm, Barueri, SP, Brazil) to obtain the plasma fraction. Albumin, globulin, glucose, cholesterol, and triglycerides were analyzed using commercial kits (Labtest, Sao Paulo, Brazil) in an automatic biochemical analyzer (Labmax 560, Labtest, Lagoa Santa, MG, Brazil).

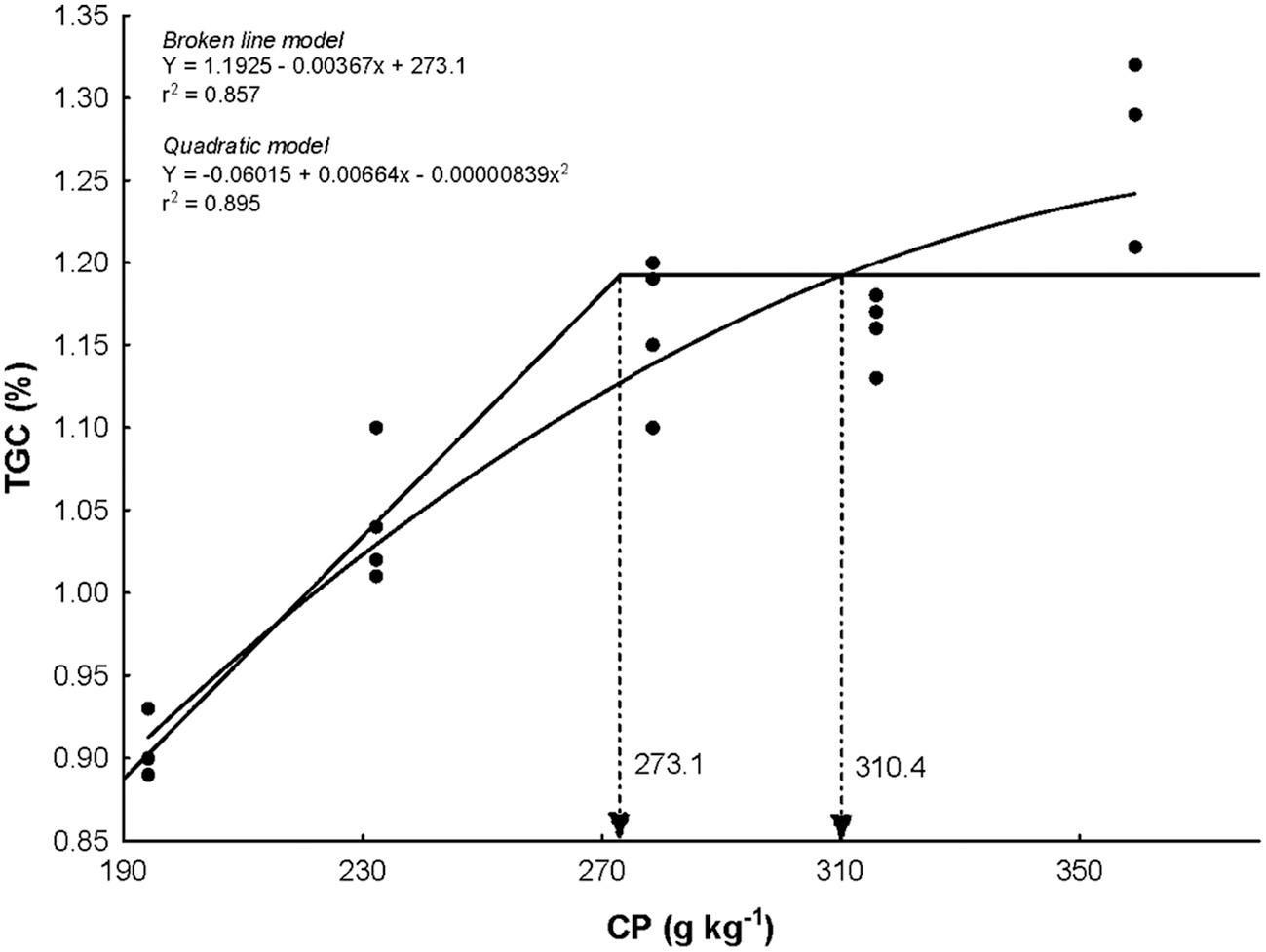

Fig. 1. Relationship between thermal-unit growth coefficient (TGC) and dietary crude protein level for juvenile pacu reared in BFT. The dashed lines indicate the estimated crude protein requirement estimated by Linear Response Plateau (LRP) and by Baker's model (Baker et al., 2002).

D.C.

2.7. Chemical analysis

Dry matter, moisture, crude protein, crude energy, ether extract, and ash analysis of feedstuffs, experimental diets, whole body, and biofloc were performed following the AOAC (2005) methodologies.

2.8. Statistical analysis

All data were submitted to normality (Shapiro-Wilk test) and homogeneity of variance (Bartlet test) tests. After the assumptions were met, they were submitted to one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA). When significant (P < 0.05), they were subjected to Tukey's test (growth performance parameters, hematological and biochemical

parameters, chemical composition, and somatic indexes) to compare the means. Data were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Carcass and fillet yields, as well as growth performance parameters, were also analyzed by regression analysis. Considering the possible over and underestimation by the quadratic polynomial and Linear Response Plateau (LRP) models (Dumas et al., 2010), the optimal crude protein level was determined by combining the two models as proposed by Baker et al. (2002), using the first intersection of the quadratic model with LRP. All statistical analyses were performed with SAS software (version 9.1).

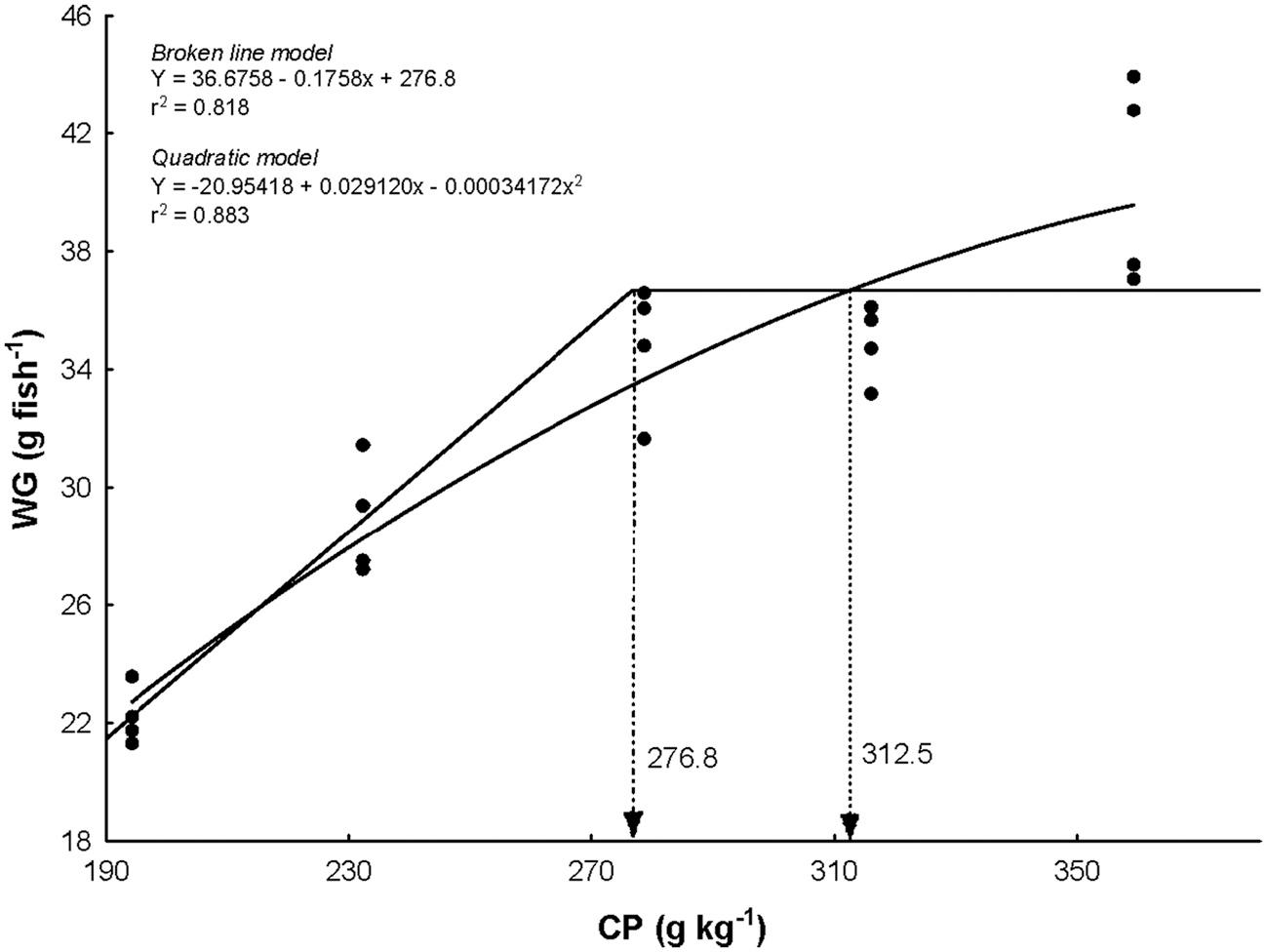

Fig. 2. Relationship between weight gain (WG) and dietary crude protein level for juvenile pacu reared in BFT. The dashed lines indicate the estimated crude protein requirement estimated by Linear Response Plateau (LRP) and by Baker's model (Baker et al., 2002).

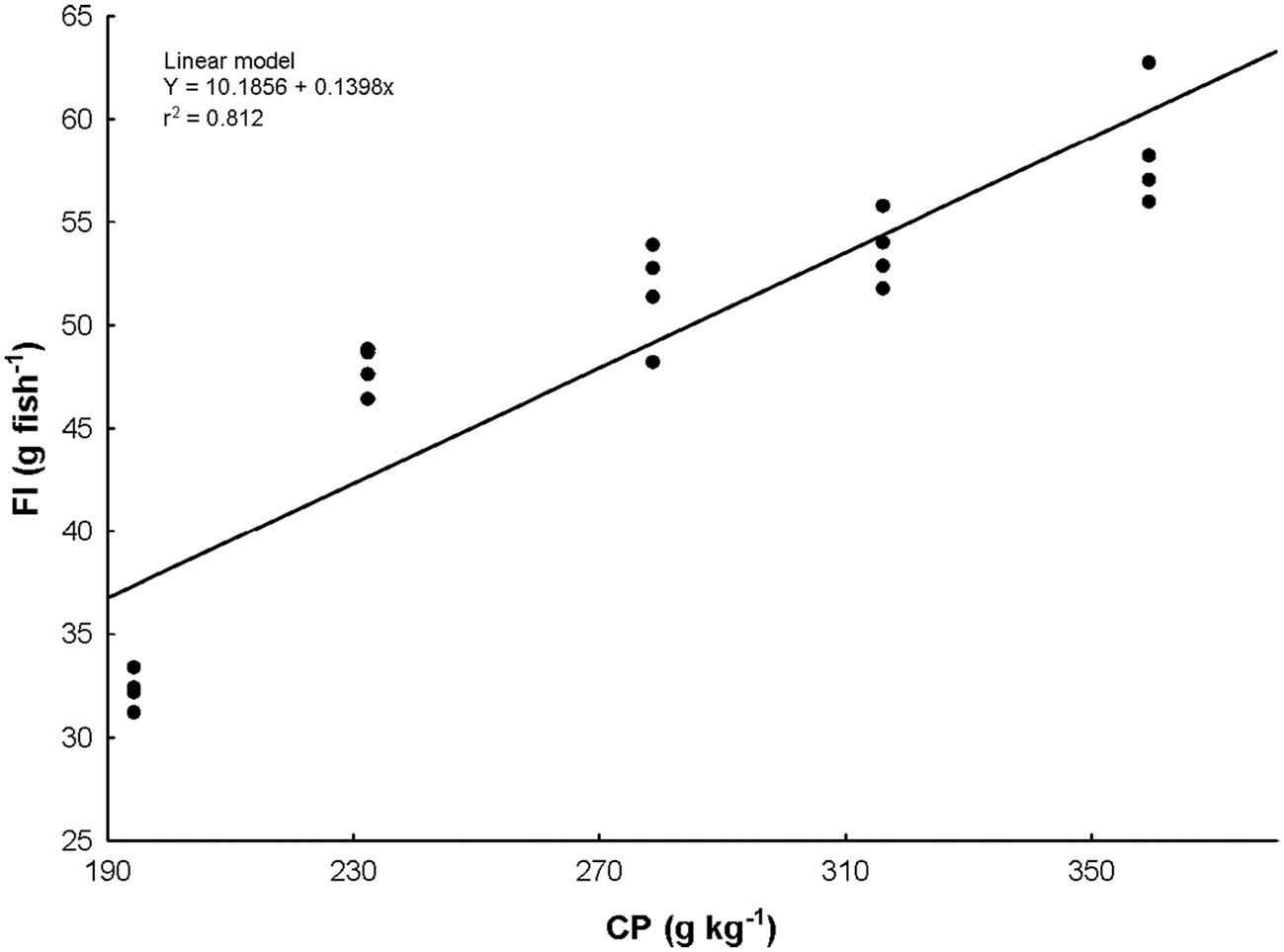

Fig. 3. Relationship between feed intake and dietary crude protein level for juvenile pacu reared in BFT.

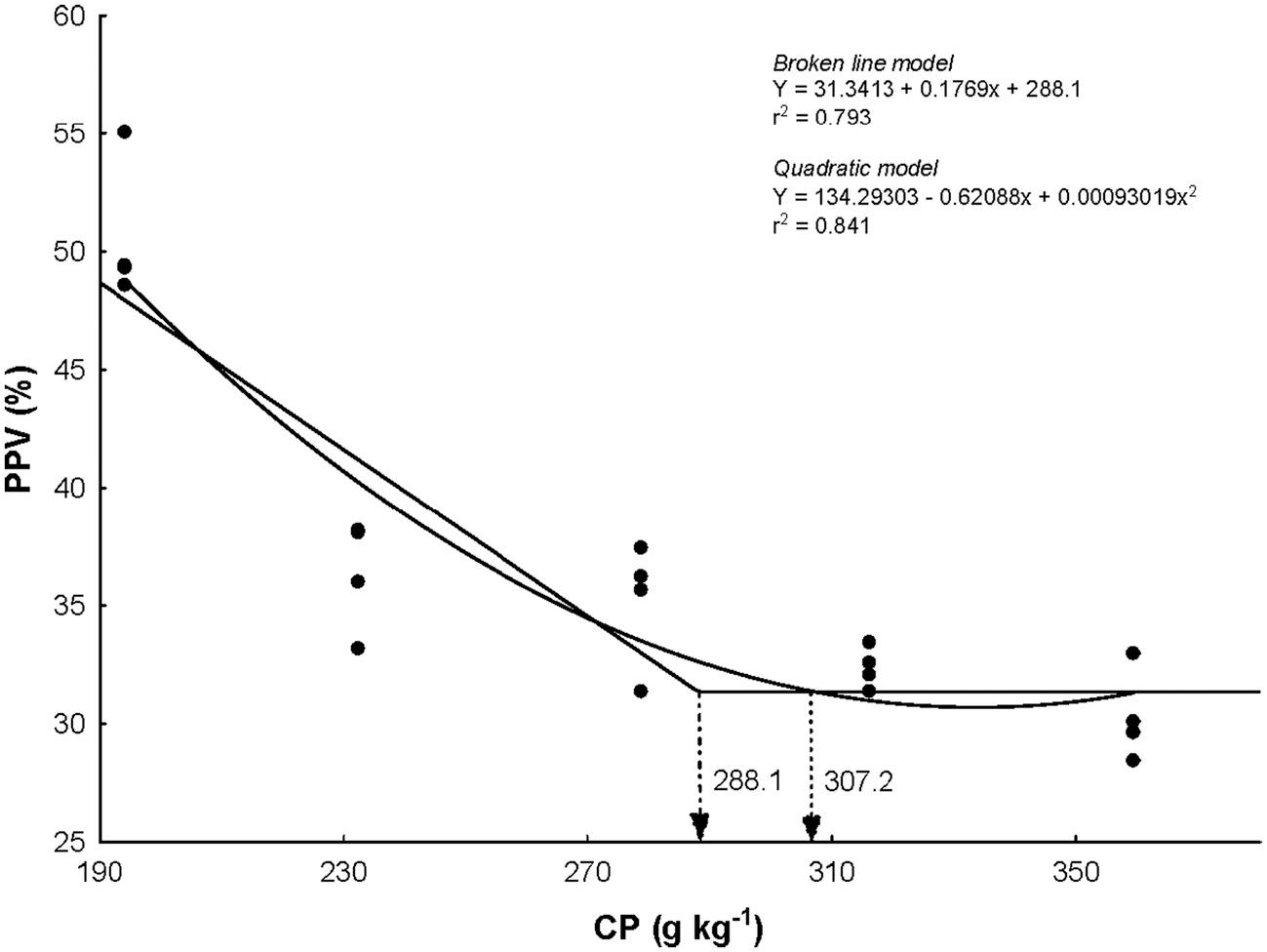

5. Relationship between protein productive value (PPV) and dietary crude protein level for juvenile pacu reared in BFT. The dashed lines indicate the estimated crude protein requirement estimated by Linear Response Plateau (LRP) and by Baker's model (Baker et al., 2002).

3. Results

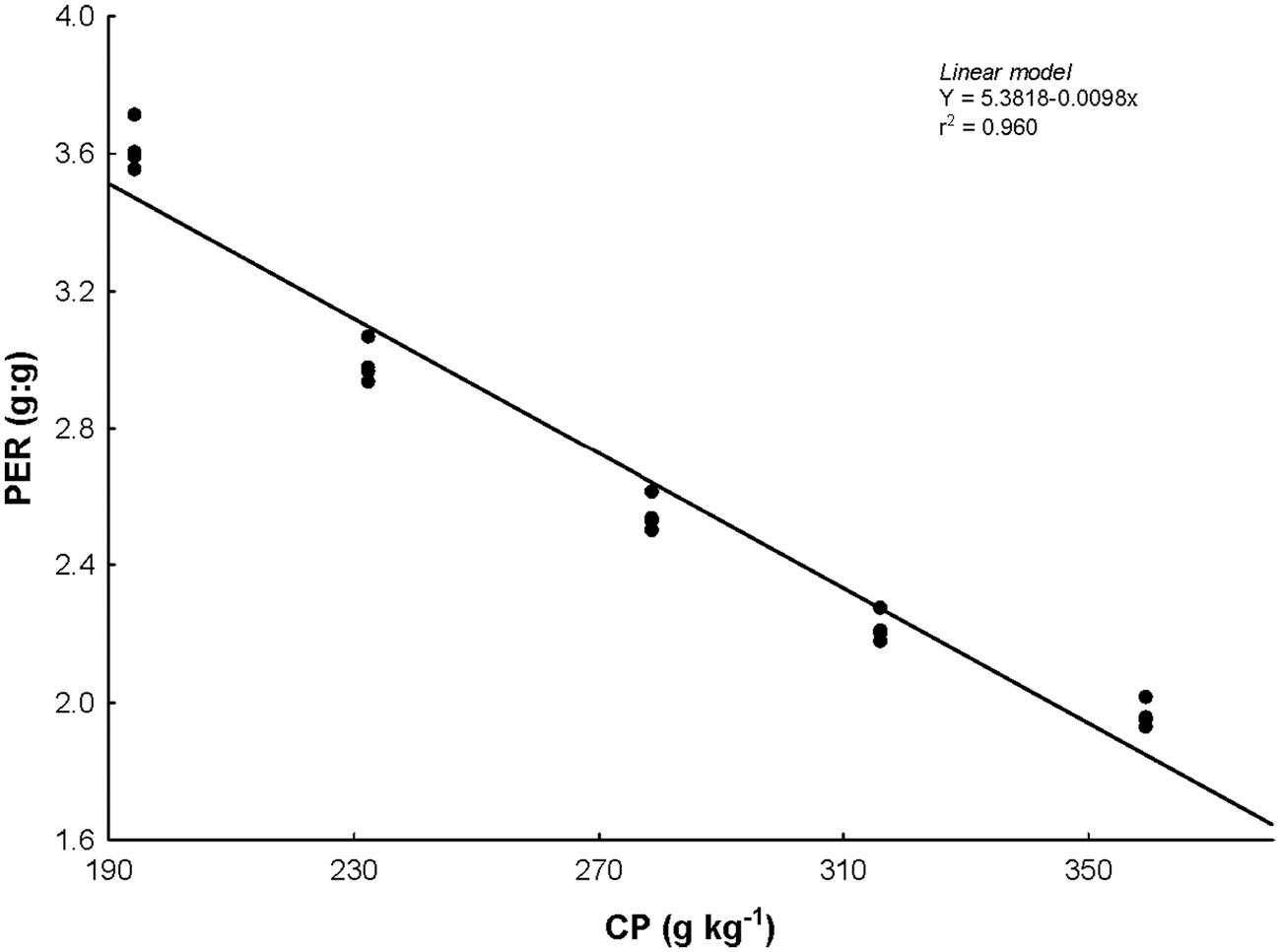

The survival rate at the end of the experiment was 100%. Crude protein requirement for optimum TGC and WG was estimated, respectively, at 310–312 g kg 1 , and the minimum level for pacu juveniles ranged from 273 to 276 g kg 1 if considered the broken line model exclusively (Figs. 1 and 2). FI increased linearly with dietary CP (Fig. 3). The opposite trend was observed for PER (Fig. 4). On the other hand, PPV decreased in fish fed up 288.1–307.2 g kg 1 CP, with a stabilization trend after these levels (Fig. 5). AFCR and U showed no difference (P > 0.05) by dietary CP. The growth performance variables are shown in Table 2

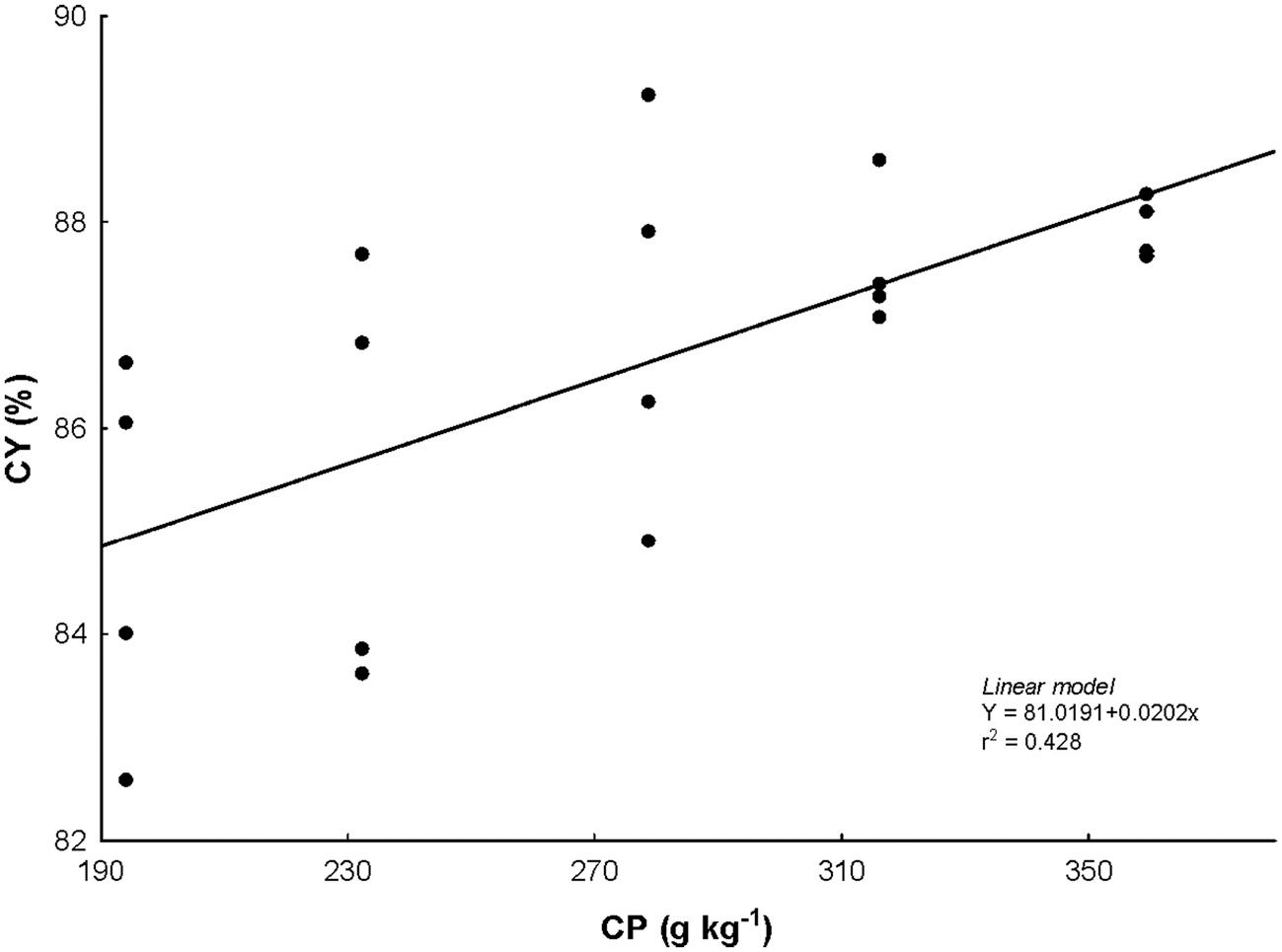

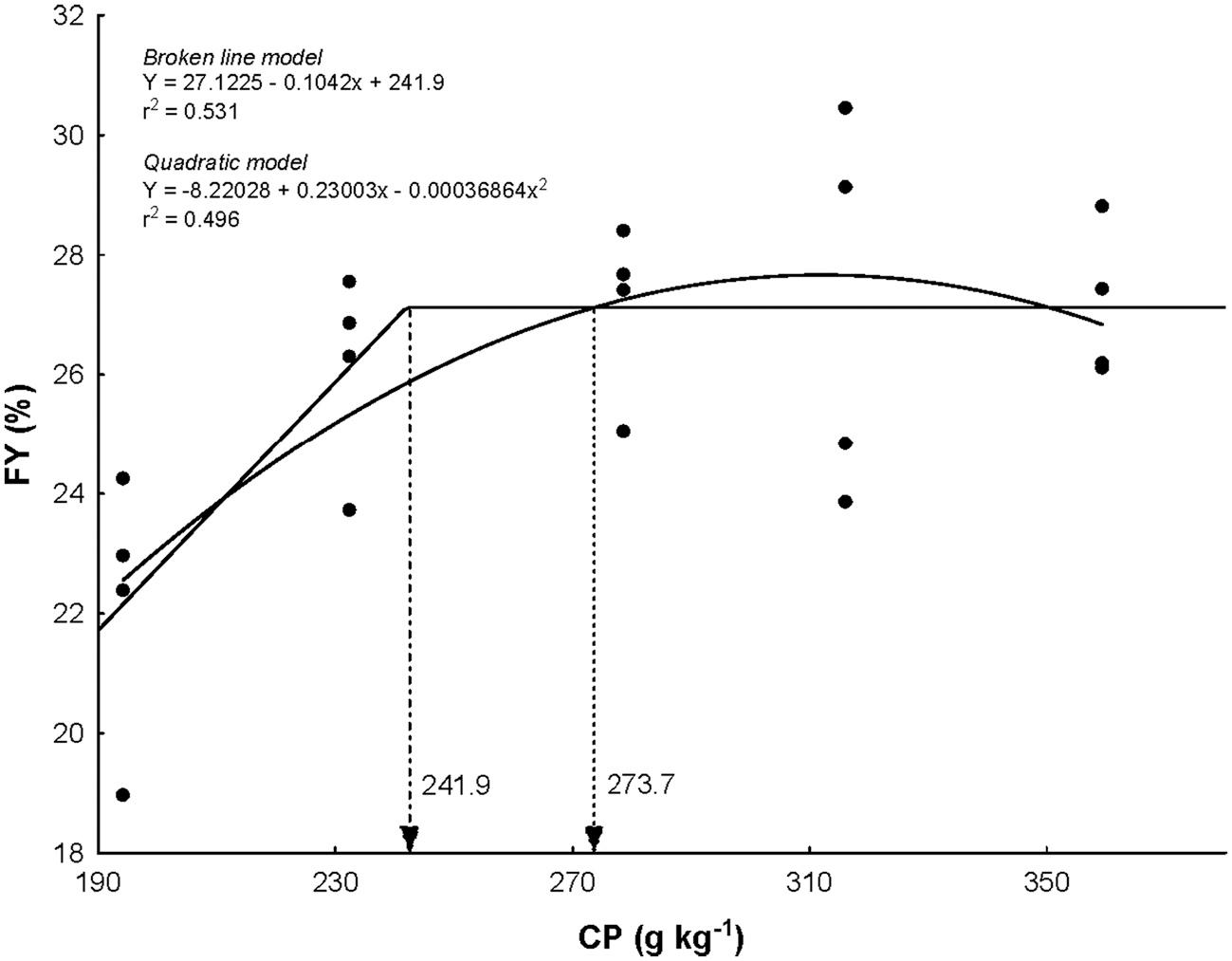

CY of fish increased (P < 0.05) proportionally to CP of diets (Fig. 6).

FY increased (P < 0.05) with dietary protein up to 241.9 g kg 1 (Fig. 7). Body index and whole-body chemical composition are summarized in Table 3. Fish fed 316 and 359 g kg 1 CP showed lower (P < 0.05) MFI compared to those fed 232 g kg 1 CP but did not differ from the other treatments. HSI did not show differences (P > 0.05) between treatments. Body protein of fish fed 316 and 359 g kg-1 CP diets showed similar (P > 0.05) content but differed statistically from those fed with other levels of CP. Gross energy and crude lipid whole-body content were similar (P > 0.05) for fish fed 194 and 232 g kg 1 CP diets. However, these parameters decreased (P < 0.05) when dietary CP levels raised after these levels. Moisture content registered the opposite trend. Fish fed 232 g kg 1 CP showed higher (P < 0.05) gross energy than those fed with higher dietary CP. Whole-body ash content did not differ significantly

Fig. 4. Relationship between protein efficiency ratio and dietary crude protein level for juvenile pacu reared in BFT.

Fig.

Table 2

Growth performance (mean ± SD) of pacu juveniles fed diets with crude protein levels in BFT during 60 days.

Variables

Values in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different according to Tukey's test (P < 0.05). WG – weight gain; TGC – thermal-unit growth coefficient; FI – feed intake; AFCR – apparent feed conversion ratio; PER – protein efficiency ratio; PPV – protein productive value; U – uniformity.

between treatments.

Fish fed 232 g kg 1 CP showed hematocrit statistically equivalent to 194 g kg 1 CP but differed (P < 0.05) from the others treatments (Table 4). Dietary CP levels did not affect biochemical parameters (Table 5).

4. Discussion

The protein requirements in this study ranged from 273 g kg 1 (LRP model) to 312 g kg 1 CP (Baker's model). LRP estimated was near of requirement (270 g kg 1 CP) estimated by Bicudo et al. (2010) for juvenile pacu in clear water (CW) system. On the other hand, the Baker's model registered a lower optimum CP requirement (≈310 g kg 1 CP) than that estimated for pacu (326 g kg 1 digestible protein ≈ 365 g kg 1 CP) by polynomial quadratic regression in CW (Khan et al., 2020). Nevertheless, results from different studies must be compared with caution since they used different statistical methods, production systems, stocking densities, experimental conditions, and initial weight.

Feeding management plays a crucial role in dietary nutrient utilization. In the present study, fish received experimental diets until apparent satiety at four times a day. Considering that the estimated optimal protein level was close to those determined in CW, the results indicate that pacu juveniles prioritized dietary nutrients according to the feeding management adopted, even though there was a lot of natural food (microbial biomass of bioflocs) available in the system. This may be due to the production of neuroendocrine regulators that inhibit or stimulate appetite, influenced by the fasting period, as previously reported for pacu (Volkoff et al., 2017). Sgnaulin et al. (2021) found that pacu juveniles' intake of natural food available in the BFT system only occurs after 24 h of fasting. Furthermore, the filtration rate of the available natural food is closely related to fish size, and small fish registered high rates (Turker et al., 2003). Consequently, biofloc consumption may have decreased proportionally to fish growth over the 60day trial. Thus, when an artificial diet is available in quantity and quality that meets the nutritional requirements, pacus prioritize this type of feed.

BFT proved to be an effective aquaculture system to pacu juveniles since it promoted high growth performance rates (WG% = 1105) after 60 days at the estimated optimum protein levels. This growth was seven times higher than the registered by Sgnaulin et al. (2021) for pacu fed 270 g kg 1 CP in BFT over 42 days. Furthermore, pacu showed WG% three to four times higher compared to CW systems at the dietary protein requirements estimated by Khan et al. (2020) and Bicudo et al. (2010) respectively, corroborating to the best growth responses and feed efficiency of tilapia in BFT in comparative studies between CW and BFT systems (Nguyen et al., 2018; Hisano et al., 2021).

Although WG% of fish fed 194 and 232 g kg 1 CP diets were respectively 37% and 17% lower than those fed with the estimated optimal level, when compared to the results of Sgnaulin et al. (2021) with pacu juveniles in BFT, WG% was respectively 4.4 and 5.8 times higher, indicating that bioflocs played an essential role as a complementary food providing nutrients to meet fish nutritional requirements, ensuring basal metabolism and a minimum growth rate, supplying some of the protein deficit. In addition, biofloc technology has probiotic species (e.g. Bacillus spp., Enterobacteria spp., and Acinetobacter spp.) (Romano et al., 2020) and bioactive substances such as carotenoids, phytosterols, bromophenols, and amino sugars (Azimi et al., 2022), which improves digestive enzyme activity and feed utilization (Long

D.C.

7. Relationship between fillet yield (FY) and dietary crude protein level for juvenile pacu reared in BFT.

others.

Table 3

Body index and whole-body chemical composition (wet basis) expressed as (mean ± SD) of pacu juveniles fed diets with crude protein levels in BFT during 60 days.

Variables Crude protein levels (g kg 1) P value

Moisture (g kg 1)

Crude

(g kg 1)

Gross energy (MJ kg 1)

Crude

(g kg 1)

Ash (g kg 1)

Values in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different according to Tukey's test (P < 0.05). HSI: hepatosomatic index and MFI: mesenteric fat index.

et al., 2015), additionally highlighting growth responses at the optimal level and decreasing negative effects on fish fed at the lowest protein levels.

However, using the endogenous food available in BFT to partially supply the nutritional requirements of fish seems to be the result of a multifactorial process involving some aspects, such as (i) fish species need to be able to filter and ingest food kept continuously in suspension by strong aeration systems; (ii) the types of microorganisms constituting this “endogenous micro food” and its concentration in the BFT system; (iii) the chemical composition and nutritional value (digestibility) of nutrients from this endogenous food, (iv) feeding management, among

The feeding and protein level of exogenous diets modifies the production of microorganisms and plankton in the aquaculture systems. Pacu juveniles have shown the ability to ingest natural food available in BFT (Sgnaulin et al., 2021) and pond (Bechara et al., 2005) even in low concentrations. However, the chemical composition of microbial biomass in BFT and its nutritional value result from multiple factors (ElSayed, 2020). Despite being a continuous supplemental food sourceand thus usually known to reduce protein and fish feed supply - this continuous feeding can result in nutritional unbalance between the exogenous and endogenous dietary nutrients ingested (Boaratti et al., 2021). This study registered an inverse proportion between pacu growth and nitrogen retention and increasing dietary protein up to a plateau around 273 and 288 g kg 1 CP, respectively. Although nitrogen retention was high in pacu feeding up to 232 g kg 1 CP, the low growth observed suggests that amino acids intake was mainly directed to the basal metabolism. Besides, higher mesenteric fat index and whole-body lipid in fish fed with 194 and 232 g kg 1 CP diets suggest a possible excess of dietary energy from both exogenous and endogenous food. Thus, it is probable that pacu juveniles in BFT systems reach the growth and nitrogen retention plateaus when ingesting the ideal amount of protein and energy, without any nutritional input interference.

Body lipids are the main form of energy storage in fish, especially in rheophilic species such as pacu, most being deposited in the abdominal cavity. Diets with a high energy/protein ratio result in higher body fat accumulation, as observed in fish fed 194 and 232 g kg 1 BW. Fish fed 190 g kg 1 BW registered higher values of plasma cholesterol and triglycerides, although without significant difference (P > 0.05) concerning other treatments. On the other hand, fish fed 278 g kg 1 CP decreased the deposition of fat (especially mesenteric) and increased whole-body protein. Carcass yield increased linearly in response to dietary protein levels. This reflects the ratio between the mass of edible (mainly muscle) and non-edible (mainly viscera) fish parts from the human nutrition viewpoint. However, carcass yield is constituted mainly by protein, lipid, and a minor ash fraction (predominantly minerals from bones), which was not influenced (P > 0.05) by dietary protein levels. Therefore, proportional differences between body lipid deposition sites (muscle, subcutaneous, celomatic, liver) associated with the negative correlation between whole-body lipid and moisture

Fig.

Table 4

Hemogram (mean ± SD) of pacu juveniles fed diets with crude protein levels in BFT during 60 days.

Variables

Values in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different according to Tukey's test (P < 0.05).

Table 5

Biochemical parameters (mean ± SD) of pacu juveniles fed diets with crude protein levels in BFT during 60 days.

Values in the same row with different superscripts are significantly different according to Tukey's test (P < 0.05). TPP: total plasma protein.

(McCue, 2010) may explain the low relationship (r2) registered by regression analysis between carcass and fillet yield of pacu juveniles and protein levels of diets.

Determining the optimal crude protein level in fish diets should also be based on physiological state and growth performance values. Nutritional deficiency can alter fish hematological parameters. Consequently, the erythrogram is an important tool to evaluate organic responses involving nutrition. In the present study, these variables showed appropriate values for the species in biofloc systems (Tavares-Dias et al., 2002; Tavares-Dias and Mataqueiro, 2004; Bicudo et al., 2009; Hisano et al., 2016), allowing the fish well-being.

Since the hematological and biochemical parameters can be used as health and nutritional indicators (Tavares-Dias and Mataqueiro, 2004), the biofloc system allowed adequate environmental and nutritional conditions, especially for fish fed diets with protein levels below recommended for the species and phase. Therefore, even the treatment with the lowest protein level enabled the maintenance of fish basal metabolism, including the hematopoietic functions.

Based on the results, the optimal crude protein level for pacu juveniles (3.16 to 43.45 g) in the biofloc system was 310 g kg 1 CP (≈ 268 g kg 1 PD). Therefore, the available endogenous food was not sufficient to guarantee a similar growth performance for pacus fed with lower protein levels in the weight range evaluated. However, considering growth performance and physiological parameters, the biofloc system appears to be a viable aquaculture system for the species.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Dara Cristina Pires: Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Gabriel Artur Bezerra: Investigation, Data curation. Andr ´ e Luiz Watanabe: Resources, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Funding acquisition. Celso Carlos Buglione Neto: Investigation, Data curation. ´ Alvaro Jos ´ e de Almeida Bicudo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization. Hamilton Hisano: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Resources, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this manuscript.

Acknowledgment

This research was funded by Embrapa and Itaipu Binacional (Project n◦ 30.20.00.034.00.02.001). The authors are grateful to Coordenaçao de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES/Brazil) for scholarship to first author, and Jose P. Lazzarin, Jefferson E. Cruz, Sara S. Machado, Tainara L.S. Blatt, Reinaldo S. Shimabuku, and Isalina A. Nascimento for their assistance during the experiment.

References

Abimorad, E.G., Carneiro, D.J., 2004. Metodos de coleta de fezes e determinaçao dos coeficientes de digestibilidade da fraçao proteica e da energia de alimentos para o pacu, Piaractus mesopotamicus (Holmberg, 1887). Rev. Bras. Zootec. 33, 1101–1109. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1516-35982004000500001

AOAC International, 2005. Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 18 ed. AOAC International, Gaithersburg, MD

APHA, 2012. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater, 22 ed, Washington, DC. American Public Health Association

Avnimelech, Y., 1999. Carbon/nitrogen ratio as a control element in aquaculture systems. Aquaculture 176, 227–235. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(99) 00085-X

Avnimelech, Y., 2014. Biofloc Technology: A Practical Guide Book, 3. ed. World Aquaculture Society

Avnimelech, Y., Kochba, M., 2009. Evaluation of nitrogen uptake and excretion by tilapia in bio floc tanks, using 15N tracing. Aquaculture 287, 163–168. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2008.10.009

Azimi, A., Shekarabi, S.P.H., Paknejad, H., Harsij, M., Khorshide, Z., Zolfaghari, M., Zakariaee, H., 2022. Various carbon/nitrogen ratios in a biofloc-based rearing system of common carp (Cyprinus carpio) fingerlings: effect on growth performance, immune response, and serum biochemistry. Aquaculture 548, part 1. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.737622

Baker, D.H., Batal, A.B., Parr, T.M., Augspurger, N.R., Parsons, C.M., 2002. Ideal ratio (relative to lysine) of tryptophan, threonine, isoleucine, and valine for chicks during the second and third weeks posthatch. Poult. Sci. 81, 485–494. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ps/81.4.485

Bechara, J.A., Roux, J.P., Díaz, F.J.R., Quintana, C.I.F., Meabe, C.A.L., 2005. The effect of dietary protein level on pond water quality and feed utilization efficiency of pacú Piaractus mesopotamicus (Holmberg, 1887). Aquac. Res. 36, 546–553. https://doi. org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01252.x

Bicudo, A.J.A., Sado, R.Y., Cyrino, J.E.P., 2009. Growth and haematology of pacu, Piaractus mesopotamicus, fed diets with varying protein to energy ratio. Aquac. Res. 40, 486–495. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2008.02120.x

Bicudo, A.J.A., Sado, R.Y., Cyrino, J.E.P., 2010. Growth performance and body composition of pacu Piaractus mesopotamicus (Holmberg 1887) in response to dietary protein and energy levels. Aquac. Nutr. 16, 213–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1365-2095.2009.00653.x

Bicudo, A.J.A., Abimorad, E.G., Carneiro, D.J., 2013. Exigencias nutricionais e alimentaçao do pacu. In: Cyrino, J.E.P., Fracalossi, D.M. (Eds.), Nutriaqua: nutriçao e alimentaçao de esp ´ ecies de interesse para aquicultura brasileira. Florian ´ opolis, Sociedade Brasileira de Aquicultura e Biologia Aqu´ atica, pp. 217–226 Boaratti, A.Z., Nascimento, T.M.T., Khan, K.U., Mansano, C.F.M., Oliveira, T.S., Queiroz, D.M.A., Fernandes, J.B.K., 2021. Assessment of the ideal ratios of digestible essential amino acids for pacu, Piaractus mesopotamicus, juveniles by the amino acid deletion method. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 1–17 https://doi.org/10.1111/ jwas.12740

Bolivar, R.B., Cruz, E.M.V., Jimenez, E.B.T., Sayco, R.M.V., Argueza, R.L.B., Ferket, P.R., Borski, R.J., 2010. Feeding reduction strategies and alternative feeds to reduce production costs of tilapia culture. Tech. Rep. Investig. 2007-2009, 50–78 Collier, H.B., 1944. The standardizations of blood haemoglobin determinations. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 50 (6), 550–552

Couto, M.V.S., Sousa, N.C., Abe, H.A., Dias, J.A.R., Meneses, J.O., Emmanuel, P., Fujimoto, R.Y., 2018. Effects of live feed containing Panagrellus redivivus and water depth on growth of Betta splendens larvae. Aquac. Res. 1–5 https://doi.org/10.1111/ are.13727

Dumas, A., France, J., Bureau, D., 2010. Modelling growth and body composition in fish nutrition : where have we been and where are we going? Aquac. Res. 41, 161–181. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2109.2009.02323.x

El-Sayed, A.-F.M., 2020. Use of biofloc technology in shrimp aquaculture : a comprehensive review, with emphasis on the last decade. Rev. Aquac. 1–30 https:// doi.org/10.1111/raq.12494

Hisano, H., Pilecco, J.L., Lara, J.A.F., 2016. Corn gluten meal in pacu Piaractus mesopotamicus diets: effects on growth, haematology, and meat quality. Aquac. Int. 1–12 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10499-016-9970-7

Hisano, H., Parisi, J., Cardoso, I.L., Ferri, G.H., Ferreira, P.M.F., 2019. Dietary protein reduction for Nile tilapia fingerlings reared in biofloc technology. J. World Aquacult. Soc. 1–11 https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12670

Hisano, H., Barbosa, P.T.L., de Arruda, Hayd L., Mattioli, C.C., 2021. Comparative study of growth, feed efficiency, and hematological profile of Nile tilapia fingerlings in biofloc technology and recirculating aquaculture system. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 53 (1), 60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-020-02523-z

IBGE, 2020. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística. Produçao da Pecuaria Municipal 2019, Brasília. https://biblioteca.ibge.gov.br/visualizacao/periodi cos/84/ppm_2019_v47_br_informativo.pdf (acessed 18 August 2021).

Khan, K.U., Gous, R.M., Mansano, C.F.M., Nascimento, T.M.T., Romaneli, R.S., Rodrigues, A.T., Fernandes, J.B.K., 2020. Response of juvenile pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus Holmberg, 1887) to balanced digestible protein. Aquac. Res. 00, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/are.14722

Khanjani, M.H., Sharifinia, M., 2020. Biofloc technology as a promising tool to improve aquaculture production. Rev. Aquac. 1–15 https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12412

Long, L., Yang, J., Li, Y., Guan, C., Wu, F., 2015. Effect of biofloc technology on growth, digestive enzyme activity, hematology, and immune response of genetically improved farmed tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Aquaculture 448, 135–141. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2015.05.017

Lorenzen, C.J., 1967. Determination of chlorophyll and pheo-pigments: spectrophotometric equations. Limnol. Oceanogr. 343–346

McCue, M.D., 2010. Starvation physiology : reviewing the different strategies animals use to survive a common challenge. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A 156, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.01.002

Merola, N., 1988. Effects of three dietary protein levels on the growth of pacu, Colossoma mitrei berg, in cages. Aquac. Fish. Manag. 19, 145–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/ j.1365-2109.1988.tb00417.x.

Nguyen, H.Y.N., Chau, T.D., Torbjorn, L., Trinh, T.L., Anders, K., 2018. Comparative evaluation of brewer s yeast as a replacement for fishmeal in diets for tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus), reared in clear water or biofloc environments. Aquaculture 495, 654–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.06.035

NRC, 2011. Nutrient Requirements of Warmwater Fishes and Shrimp. The National Academies Press, Washington, D.C.

Oliveira, L.K., Pilz, L., Furtado, P.S., Ballester, E.L.C., Bicudo, A.J.A., 2021. Growth, nutritional efficiency, and profitability of juvenile GIFT strain of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) reared in biofloc system on graded feeding rates. Aquaculture 541, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2021.736830

Petrere Júnior, M., 1989. River fisheries in Brazil: a review. Regul. Rivers: Res. Mgmt 4, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrr.3450040102

Proença, C.E.M., Bittencourt, P.R.L., 1994. Manual de piscicultura tropical. IBAMA, Brasília.

Ranzani-Paiva, M.J., P´ adua, S.B., Tavares-Dias, M., Egami, M., 2013. M´ etodos para an ´ alise hematol ´ ogica em peixes. Fapesp. Maring´ a, Eduem

Romano, N., Surratt, A., Renukdas, N., Monico, J., Egnew, N., Kumarsinha, A., 2020. Assesing the geasibility of biofloc technology to largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides juveniles: insights into their welfare and physiology. Aquaculture. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2020.735008

Rostagno, H.S., Albino, L.F.T., Hannas, M.I., Donzele, J.L., Sakomura, N.K., Perazzo, F.G., Brito, C.O., 2017. Tabelas brasileiras para aves e suínos: composiçao de alimentos e exigencias nutricionais, 4a ediçao. Viçosa

Sgnaulin, T., Pinho, S.M., Durigon, E.G., Thomas, M.C., Mello, G.L., Emerenciano, M.G. C., 2021. Culture of pacu Piaractus mesopotamicus in biofloc technology (BFT): insights on dietary protein sparing and stomach content. Aquac. Int. 1–17

Shourbela, R.M., Khatab, S.A., Hassan, M.M., Van Doan, H., Dawood, M.A.O., 2021. The effect of stocking density and carbon sources on the oxidative status, and nonspecific immunity of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) reared under biofloc conditions. Animals 11, 184. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani11010184

Silva, M.A., Alvarenga, E.R., Alves, G.F.O., Manduca, L.G., Turra, E.M., Brito, T.S., Teixeira, E.A., 2018. Crude protein levels in diets for two growth stages of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) in a biofloc system. Aquac. Res. 1–11 https://doi.org/ 10.1111/are.13730

Tavares-Dias, M., Mataqueiro, M.I., 2004. Características hematol ´ ogicas, bioquímicas e biom´ etricas de Piaractus mesopotamicus Holmberg, 1887 (Osteichthyes: Characidae) oriundos de cultivo intensivo. Acta Sci. Biol. Sci. 26, 157–162. https://doi.org/ 10.4025/actascibiolsci.v26i2.1647.

Tavares-Dias, M., Martins, M.L., Schalch, S.H.C., Onaka, E.M., Quintana, C.I.F., Moraes, J.R.E., Moraes, F.R., 2002. Alteraçoes hematol ´ ogicas e histopatol ´ ogicas em pacu, Piaractus mesopotamicus Holmberg, 1887 (Osteichthyes, Characidae), tratado com sulfato de cobre (CuSO4). Acta Sci. 24, 547–554. https://doi.org/10.4025/ actascibiolsci.v24i0.2358

Turker, H., Eversole, A.G., Brune, D.E., 2003. Effect of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus (L.), size on phytoplankton filtration rate. Aquac. Res. 34, 1087–1091. https://doi. org/10.1046/j.1365-2109.2003.00917.x

Valladao, G.M.R., Gallani, S.U., Pilarski, F., 2016. South American fish for continental aquaculture. Rev. Aquac. 0, 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/raq.12164

Vidal Júnior, M.V., Donzele, J.L., Camargo, A.C.S., Andrade, D.R., Santos, L.C., 1998. Níveis de proteína bruta para tambaqui (Colossoma macropomun), na fase de 30 a 250 gramas. 1. Desempenho dos tambaquis. Rev. Bras. Zootec. 27, 421–426

Volkoff, H., Sabioni, R.E., Coutinho, L.L., Cyrino, J.E.P., 2017. Appetite regulating factors in pacu (Piaractus mesopotamicus): tissue distribution and effects of food quantity and quality on gene expression. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A 203, 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2016.09.022

Wasielesky Júnior, W., Atwood, H., Stokes, A., Browdy, C.L., 2006. Effect of natural production in a zero exchange suspended microbial floc based super-intensive culture system for white shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei Aquaculture 258, 396–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.04.030

Wei, Y., Liao, S.-A., Wang, A., 2016. The effect of different carbon sources on the nutritional composition, microbial community and structure of bioflocs. Aquaculture 465, 88–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2016.08.040.

William Wyndham, Lord Grenville

from a painting by Hoppner

Pitt’s appreciation of his sound sense appeared in his choice of Grenville for very delicate diplomatic missions to The Hague and Paris in the crisis of 1787. The evenness of his judgement and temper procured him the Speakership of the House of Commons in 1789, after the death of Cornwall. From this honourable post he was soon transferred to more congenial duties, as Secretary of State, and entered the Upper House as Lord Grenville. In 1791 he became Secretary for Foreign Affairs, his conduct of which will engage our attention later on. Here we may note that in all his undertakings he gained a reputation for soundness; and if the neutral tints of his character procured for him neither the enthusiastic love of friends nor the hatred of foes, he won the respect of all. The envious railers who penned the “Rolliad” could fasten on nothing worse than his solidity—

A youth who boasts no common share of head. What plenteous stores of knowledge may contain The spacious tenement of Grenville’s brain! Nature, in all her dispensations wise, Who formed his head-piece of so vast a size, Hath not, ’tis true, neglected to bestow Its due proportion to the part below.

Unfortunately, though Grenville could manage business, he could not manage men; and at this point he failed to make good a defect in the political panoply of Pitt. On neither of the cousins had nature bestowed the social tact which might have smoothed the rubs of diplomatic discussion, say, in those with the French envoy, Chauvelin, in 1792. That fervid royalist, Hyde de Neuville, complained bitterly of the freezing powers of Downing Street. The enthusiastic young Canning found it impossible to work with Grenville, who was also on strained terms with Dundas. The “inner Cabinet,” composed of Pitt, Grenville, Dundas, must have been the scene of many triangular

duels; and it needed all the mental and moral superiority of Pitt (as to which every one bears witness) to preserve even the appearance of harmony between seconds who were alike opinionated, obstinate, and covetous of patronage.386 On the whole, the personality of Grenville must rank among the dullest of that age. I have found no striking phrase which glitters amidst the leaden mass of his speeches and correspondence. His life has never been written. He would be a very conscientious zealot who would undertake it.

Turning to the central figure of the group, we have once more to mourn the lack of information about those smaller details which light up traits of character. Few of Pitt’s letters refer to his private affairs in the years 1784–86; and the knowledge which we have of them is largely inferential. Even the secondary sources fared badly; for it seems that Pitt’s housemaid made a holocaust of the many letters which Wilberforce wrote to him during his foreign tour in 1785.387 In the Pitt Papers there is only one letter of Wilberforce of this period; and as it throws light on their friendship and the anxiety felt by Pitt’s friends at the time of the Irish Propositions, I print it here almost in extenso. 388

Lausanne, 2nd Aug., 1785.

M� ���� P���,

... If I were to suffer myself to think on politics, I should be very unhappy at the accounts I hear from all quarters: nothing has come from any great authority; but all the reports, such as they are, are of one tendency. I repose myself with confidence on you, being sure that you have spirit enough not to be deterred by difficulties if you can carry your point thro’; and trusting that you will have that greater degree of spirit which is requisite to make a person give up at once when the bad consequences which would follow his going on are at a distance. Yet I cannot help being extremely anxious: your own character, as well as the welfare of the country are at stake; but we may congratulate ourselves that they are here inseparably connected. In the opinion of

unprejudiced men I do not think you will suffer from adjourning the Irish propositions ad calendas Graecas, if the state of Ireland makes it dangerous to proceed and you can make it evident you had good reason to bring them on, which I think you can. At the worst, the consequences on this side are only that you suffer (the Country may suffer too, but I am taking for granted this is the lesser evil); but I tremble and look forward to what may happen if the Irish Parliament should pass the propositions, and the Irish nation refuse to accept them; nor would it be one struggle only; but as often as any Bill should come over from our House of Commons to be passed in theirs, which was obnoxious, there would be a fresh opportunity for reviving it, especially as you have an Opposition to deal with as unprincipled and mischievous as ever embroiled the affairs of any country. God bless you, my dear Pitt and carry you thro’ all your difficulties! You may reckon yourself most fortunate in that chearfulness of mind which enables you every now and then to throw off your load for a few hours and rest yourself. I fancy it must have been this which, when I am with you, prevents my considering you as an object of compassion, tho’ Prime Minister of England; for now, when I am at a distance, out of hearing of your foyning, and your (illegible) other proofs of a light heart, I cannot help representing you to myself as oppressed with cares and troubles, and what I feel for you is more, I believe, than even Pepper feels in the moments of his greatest anxiety; and what can I say more?...

Pepper Arden, to whom Wilberforce here refers, scarcely lived up to his name. His character and his countenance alike lacked distinction. The latter suffered from the want of a nose, or at least, of an effectively imposing feature. What must this have meant in a generation which remembered the effect produced by Chatham’s “terrifying beak,” and was dominated by the long and concave curve on which Pitt suspended the House of Commons! Further, Pepper lacked dignity. His manner was noisy and inelegant.389 He pushed himself forward as a Cambridge friend of Pitt; and the House resented the painful efforts of this flippant young man to run in harness by the side of the genius. Members roared with laughter when Arden marched in,

at Christmastide of 1783, to announce that Pitt, as Prime Minister of the Crown, would offer himself for re-election. The effrontery of the statement was heightened by the voice and bearing of the speaker. Nevertheless, Pitt, as we have seen, made him Attorney-General. No appointment called forth more criticism. He entered the peerage as Lord Alvanley.

It is the characteristic of genius to attract and inspire the young; and Pitt’s influence on them was second only to that of Chatham. As we shall see later on, Canning caught the first glow of political enthusiasm from the kindling gaze of the young Prime Minister. Patriotism so fervid, probity so spotless, eloquence so moving fired cooller natures than Canning’s; and among the most noteworthy of those who now came forward was Henry Addington. His father, Anthony Addington, had started life as a medical man in Reading, and afterwards in Bedford Row, London, where Henry was born in 1754. In days when that profession held a lower place than at present, this fact was to be thrown in the teeth of the son on becoming Prime Minister. Chatham, however, always treated his family physician (for such Addington became) with chivalrous courtesy. Largely by the care of the doctor William Pitt was coaxed into maturity after his “wan” youth.390 It was natural, then, that the sons should become acquainted, especially as young Addington, after passing through Winchester School and Brasenose College, Oxford, entered at Lincoln’s Inn while Pitt was still keeping his terms there.

Considering the community of their studies and tastes, it is singular that few, if any, of their letters of this period survive. Such as have come down to us are the veriest scraps. Here, then, as elsewhere, some evil destiny (was it Bishop Tomline?) must have intervened to blot out the glimpses of the social side of the statesman’s life. It is clear, however, that Pitt must have begun to turn Addington’s thoughts away from Chancery Lane to Westminster; for the latter in 1783 writes eagerly against “the offensive Coalition of Fox and North.” At Christmas, when Pitt leaped to office as Prime Minister, he sought to bring Addington into the political arena, and held out the prospect of some subordinate post. Addington accordingly stood for Devizes, and was chosen by a unanimous vote at the hustings in April 1784. Nevertheless, his cool and circumspect nature rose slowly to the

height of the situation at Westminster. Externals were all in his favour. His figure was tall and well proportioned; his features, faultlessly regular, were lit up by a benevolent smile; and his deferential manners gave token of success either as family physician or family attorney In fine, a man who needed only the spur of ambition, or the stroke of calamity, to achieve a respectable success. It is said that Pitt early bade him fix his gaze on the Speaker’s chair, to which, in fact, he helped him in 1789, after Grenville’s retirement. But, for the present, nothing stirred Addington’s nature from its exasperating calm. As worldly inducements failed, Pitt finally made trial of poetry. During a ride together to Pitt’s seat at Holwood, the statesman sought in vain to appeal to his ambition; but Addington—five years his senior, be it remembered—pleaded the disqualifying effects of early habits and disposition. Thereupon Pitt burst out with the following passage from Waller’s poem on Henrietta Maria:

The lark that shuns on lofty boughs to build Her humble nest, lies silent in the field; But should the promise of a brighter day, Aurora smiling, bid her rise and play, Quickly she’ll show ’twas not for want of voice, Or power to climb, she made so low a choice; Singing she mounts; her airy notes are stretch’d Towards heaven, as if from heaven alone her notes she fetch’d.

Then the statesman set spurs to his horse and left Addington far behind.391 It is curious that when Addington’s ambition was fully aroused, it proved to be an obstacle to Pitt and a danger to the country in the crisis of 1803–4.

Adverting now to certain details of Pitt’s private life, we notice that he varied the time of his first residence on Putney Heath (August 1784–November 1785) by several visits to Brighthelmstone, perhaps in order to shake off the fatigue and disappointment attendant on his Irish and Reform policy. At that seaside resort he spent some weeks in the early autumn of 1785, enjoying the society of his old Cambridge friends, “Bob” Smith (afterwards Lord Carrington), Pratt (afterwards

Lord Camden), and Steele. We can imagine them riding along the quaint little front, or on the downs, their interchange of thought and sallies of wit probably helping in no small degree the invigorating influences of sea air and exercise. If we may trust the sprightly but spiteful lines in one of the “Political Eclogues,” it was at Brighton that Pitt at these times especially enjoyed the society of “Tom” Steele, whom he had made Secretary of the Treasury conjointly with George Rose. Unlike his colleague, whose visage always bore signs of the care and toil of his office, Steele was remarkable for the rotundity and joviality of his face and an inexhaustible fund of animal spirits.392 Perhaps it was this which attracted Pitt to him in times of recreation. The lines above referred to occur in an effusion styled—“Rose, or the Complaint,”—where the hard working colleague is shown as bemoaning Pitt’s preference for Steele:

But vain his hope to shine in Billy’s eyes, Vain all his votes, his speeches, and his lies.

Steele’s happier claims the boy’s regard engage, Alike their studies, nor unlike their age:

With Steele, companion of his vacant hours, Oft would he seek Brighthelmstone’s sea-girt towers; For Steele relinquish Beauty’s trifling talk, With Steele each morning ride, each evening walk; Or in full tea-cups drowning cares of state On gentler topics urge the mock debate.

However much Pitt enjoyed Steele’s company on occasions like these, he did not allow his feelings to influence him when a question of promotion arose. Steele’s talents being only moderate, his rise was slow, but he finally became one of the Paymasters of the Forces. In that station his conduct was not wholly satisfactory; and Pitt’s friendship towards him cooled, though it was renewed not long before the Prime Minister’s death.

For George Rose, on the other hand, despite his lack of joviality, Pitt cherished an ever deepening regard proportioned to the thoroughness and tactfulness of his services at the Treasury. In view of

the vast number of applications for places and pensions, of which, moreover, Burke’s Economy Bill had lessened the supply, the need of firm control at the Treasury is obvious; and Pitt and the country owed much to the man who for sixteen years held the purse-strings tight.393 On his part Rose felt unwavering enthusiasm for his chief from the time of their first interview in Paris in 1783 until the dark days that followed Austerlitz. Only on two subjects did he refuse to follow Pitt, namely, on Parliamentary Reform, from which he augured “the most direful consequences,” and the Slavery Question. That he ventured twice to differ decidedly from Pitt (in spite of earnest private appeals) proves his independence of mind as well as the narrowness of his outlook. He even offered to resign his post at the Treasury owing to their difference on Reform, but Pitt negatived this proposal. We need not accept his complacent statement that Pitt later on came over decidedly to his opinion on that topic.394

The tastes of the two friends were very similar, especially in their love of the country; and it was in the same month (September 1785) that each bought a small estate. We find Pitt writing at that time to Wilberforce respecting his purchase of “Holwood Hill,” near Bromley, Kent, and stating that Rose had just bought an estate in the New Forest, which he vowed was “just breakfasting distance from town.” “We are all turning country gentlemen very fast,” added the statesman. A harassing session like that of 1785 is certain to set up a centrifugal tendency; and we may be sure that the nearness of Holwood to Hayes was a further attraction. Not that Pitt was as yet fond of agriculture. He had neither the time nor the money to spare for the high farming which was then yearly adding to the wealth of the nation. But he inherited Chatham’s love of arranging an estate, and he was now to find the delight of laying out grounds, planting trees and shrubs and watching their growth. Holwood had many charms—“a most beautiful spot, wanting nothing but a house fit to live in”—so he described it to Wilberforce.395 He moved into his new abode on 5th November 1785, and during the rest of the vacation spent most of his time there, residing at Downing Street only on Wednesdays, Thursdays, and Fridays. Many affairs of State were decided at parties at Holwood, or, later on, at Dundas’s villa at Wimbledon.

Pitt admitted to Wilberforce that the purchase of Holwood was a piece of folly; and this was soon apparent to all Pitt’s friends who had old-fashioned notions of making both ends meet. That desirable result had rarely, if ever, been attained by the son of the magnificent Chatham. Sparing for the nation’s exchequer, Pitt was prodigal of his own. The aristocratic hauteur, of which all but his friends complained, led him to disregard the peccadilloes of servants and the overcharges of tradesmen. A bachelor Prime Minister, whose nose is high in air, is good sport for parasites; and even before the purchase of Holwood, Pitt was in difficulties. During one of the visits to Brighthelmstone, “Bob” Smith undertook to overhaul his affairs, and found old and forgotten bills amounting to £7,914. The discovery came as a shock; for Pitt, with his usual hopefulness, had told his Mentor that, as threequarters of his official salary were due, he would have enough for his current liabilities. A further scrutiny showed that tradesmen, in default of any present return, took care to ensure an abundant harvest in the future. The butcher usually sent, or charged for, three or four hundredweight of meat on a Saturday, probably because Pitt was often away for the week-end. The meat bill for January 1785, when Pitt generally dined out, was £96, which, reckoning the price at sixpence a pound, implied a delivery of 34 hundredweight. Other bills for provisions (wrote Smith to Wilberforce) “exceed anything I could have imagined.” Apparently they rose in proportion to Pitt’s absence from home. His accounts were kept by a man named Wood, whose bookkeeping seems to have been correct; but Smith begged Wilberforce to urge on Pitt the need of an immediate reform of his household affairs.396 Whether it took place, we cannot tell; for this is one of the private subjects over which Bishop Tomline chose to draw the veil of propriety.

An economical householder would have found relief from the addition of £3,000 a year to his income. That was the net sum which accrued to him after August 1792, from the Lord Wardenship of the Cinque Ports.397 That Pitt felt more easy in his mind is clear from his letter to Lady Chatham, dated Downing Street, 11th November 1793. She had been in temporary embarrassment. He therefore sent £300, and gently chid her for concealing her need so long. He continued as follows: “My accession of income has hitherto found so much

employment in the discharge of former arrears as to leave no very large fund which I can with propriety dispose of. This, however, will mend every day, and at all events I trust you will never scruple to tell me when you have the slightest occasion for any aid that I can supply.”

398

Unfortunately, Pitt soon fell into difficulties, and partly from his own generosity as Colonel of the Walmer Volunteers. As we shall also see, he gave £2,000 to the Patriotic Fund started in January 1798. But carelessness continued to be his chief curse. In truth his lordly nature and his early training in the household of Chatham unfitted him for the practice of that bourgeois virtue, frugality. That he sought to practise it for the Commonwealth is a signal proof of his patriotism. We shall see that his embarrassments probably hindered him from a marriage, which might have crowned with joy his somewhat solitary life.

In the career of Pitt we find few incidents of the lighter kind, which diversify the lives of most statesmen of that age. Two such, however, connect him with the jovial society of Dundas. It was their custom to outline over their cups the course of the forthcoming debates; and on one occasion, when a motion was to be brought forward by Mr. (afterwards Earl) Grey, Dundas amused the company by making a burlesque oration on the Whig side. Pitt was so charmed by the performance that he declared that Dundas must make the official reply. The joke sounded well over wine; but great was the Scotsman’s astonishment to find himself saddled with the task in the House. Members were equally taken aback; and the lobbies soon rustled with eager conjectures as to the reason why Pitt had surrendered his dearly cherished prerogative. It then transpired that the Prime Minister had acted partly on a whim, and partly on the conviction that a speaker who had so cleverly pleaded a case must be able to answer it with equal effect.399

The other incident is likewise Bacchic, and is also uncertain as to date. Pitt, Dundas, and Thurlow had been dining with Jenkinson at Croydon; and during their rollicking career back towards Wimbledon, they found a toll-bar gate between Streatham and Tooting carelessly left open. Wine, darkness, and the frolicsome spirit of youth prompted them to ride through and cheat the keeper. He ran out, called to them

in vain, and, taking them for highwaymen, fired his blunderbuss at their retreating forms.400 The discharge was of course as harmless as that of firearms usually was except at point-blank range; but the writers of the “Rolliad” got wind of the affair, and satirised Pitt’s lawlessness in the following lines:

Ah, think what danger on debauch attends!

Let Pitt o’er wine preach temperance to his friends, How, as he wandered darkling o’er the plain, His reason drowned in Jenkinson’s champagne, A rustic’s hand, but righteous fate withstood, Had shed a premier’s for a robber’s blood.

Gaiety and grief often tread close on one another’s heels; and Pitt had his full share of the latter. The sudden death of his sister Harriet, on 25th September 1786, was a severe blow. She had married his Cambridge friend, Eliot, and expired shortly after childbirth. She was his favourite sister, having entered closely and fondly into his early life. He was prostrated with grief, and for some time could not attend even to the public business which was his second nature. Eliot, now destined to be more than ever a friend and brother, came to his house and for some time lived with him. It will be of interest to print here a new letter of George III to a Mr. Frazer who had informed him of the sad event.

W������, Sept. 25, 1786. 9.15 p.m.401

I am excessively hurt, as indeed all my family are, at the death of the amiable Lady Harriot Elliot (sic); but I do not the less approve Mr. Frazer’s attention in acquainting me of this very melancholy event. I owne I dread the effect it may have on Mr. Pitt’s health: I think it best not at this early period to trouble him with my very sincere condolence; but I know I can trust to the prudence of Mr. Frazer, and therefore desire he will take the most proper method

of letting Mr. Pitt know what I feel for him, and that I think it kindest at present to be silent.

G. R.

The King further evinced his tactful sympathy by suggesting that Pitt should for a time visit his mother at Burton Pynsent. In other respects his private life was uneventfully happy. The conclusion of the commercial treaty with France, the buoyancy of the national revenue, and the satisfactory issue of the Dutch troubles must have eased his anxieties in the years 1786–87; and after the serious crisis last named, his position was truly enviable, until the acute situation arising from the mental malady of George III overclouded his prospects at the close of the year 1788.

Certainly Pitt was little troubled by his constituents. Almost the only proof of his parliamentary connection with the University of Cambridge (apart from warnings from friends at election times how so and so is to “be got at”) is in a letter which I have discovered in the Hardwicke Papers. It refers to a Cambridge Debt Bill about to be introduced by Charles Yorke in April 1787, to which the University had requested Pitt to move certain amendments in its interest. It will be seen that Pitt proposed to treat the request rather lightly:

D��� Y����,

I am rather inclined to wish the Cambridge [Debt] Bill should pass without any alteration, unless you think there are material reasons for it.—The impanelling the jury does not seem to be a point of much consequence, but seems most naturally to be the province of the mayor.—With regard to the appeal, I think we agreed to strike it out entirely.—As the Commission are a mixed body from the town, the county, and the University, there seems to be an impropriety in appealing either to the town sessions or the County Sessions, either of which may be considered as only one out of three parties interested. The decision of the Commission appears therefore the most satisfactory, and if I recollect right, it is final as the bill now stands.

Yours most sincerely, W. P���.402

In the whole of Pitt’s correspondence I have found only one episode which lights up the recesses of his mind. As a rule, his letters are disappointingly business-like and formal. He wrote as a Prime Minister to supporters, rarely as a friend to a friend. And those who search the hundreds of packets of the Pitt Papers in order to find the real man will be tempted to liken him to that elusive creature which, when pursued, shoots away among the rocks under a protective cloud of ink. At one point, however, we catch a glimpse of his inmost beliefs. Wilberforce, having come under deep religious convictions in the autumn of 1785, resolved to retire for a time from all kinds of activity in order to take his bearings anew. Then he wrote to Pitt a full description of his changed views of life, stating also his conviction that he must give up some forms of work and amusement, and that he could never be so much of a party man as he had hitherto been. Pitt’s reply, of 2nd December 1785, has recently seen the light. After stating that any essential opposition between them would cause him grief but must leave his affection quite untouched, he continued as follows:

Forgive me if I cannot help expressing my fear that you are nevertheless deluding yourself into principles which have but too much tendency to counteract your own object and to render your virtues and your talents useless both to yourself and to mankind. I am not, however, without hopes that my anxiety paints this too strongly. For you confess that the character of religion is not a gloomy one, and that it is not that of an enthusiast. But why then this preparation of solitude, which can hardly avoid tincturing the mind either with melancholy or superstition? If a Christian may act in the several relations of life, must he seclude himself from them all to become so? Surely the principles as well as the practice of Christianity are simple, and lead not to meditation only but to action. I will not, however, enlarge upon these subjects now. What I ask of you, as a mark both of your friendship and of the candour which belongs to your mind, is to open yourself fully and without