OceanCurrents

PhysicalDriversinaChangingWorld

RobertMarsh

ProfessorinOceanography,HeadofPhysicalOceanography

ResearchGroup,UniversityofSouthampton,UK

ErikvanSebille

AssociateProfessorinOceanography, UtrechtUniversity,TheNetherlands

Elsevier

Radarweg29,POBox211,1000AEAmsterdam,Netherlands

TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates

Copyright©2021ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearance CenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher(other thanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroadenour understanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusing anyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationormethods theyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhavea professionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeanyliability foranyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceorotherwise,or fromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN:978-0-12-816059-6

ForinformationonallElsevierpublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: CandiceJanco

AcquisitionsEditor: LouisaMunro

EditorialProjectManager: SaraPianavilla

ProductionProjectManager: DebasishGhosh

CoverDesigner: MatthewLimbert

TypesetbySPiGlobal,India

Acknowledgements

Wehavemanypeopleandorganizationstothank.

Forcommentsbothnurturingandforthright,perchapter,wearegratefultovaluedcolleagues aroundtheworld:LisaBeal,GrantBigg,HarryBryden,PiersChapman,SjoerdGroeskamp, NikolaiMaximenko,PaulMyers,AlexSenGupta,BabluSinha,JanetSprintall,JanZika.We respondedasfaraspossibletotheirwide-rangingcomments.Astimeranout,weperhapsfell shortofsomeexpectations,butwethinkthebookwasgreatlyimprovedthroughtheirforensic scrutiny!

ThearrivalofCovid-19posedseveralchallengesaswecompletedthefirstdraft,sought reviews,andrevisedthechapters.Throughoutthistime,colleaguesattheUniversityof SouthamptonandUtrechtUniversitymaintainedtheITsystemsthatwereliedontocomplete calculationsandfigures,forwhichwearemostgrateful.

Weareindebtedtocolleaguesaroundtheworldforthevariousdatasets,modelsimulations,and softwarethatwehaveusedthroughoutthebook,acknowledgedinturn:

• DatacollectedandmadefreelyavailablebytheInternationalArgoProgramandthe nationalprogramsthatcontributetoit(http://www.argo.ucsd.edu, http://argo.jcommops. org)

• TheEN4temperatureandsalinitydataset,freelyprovidedbytheMetOfficeHadleyCentre

• NCEPReanalysisdataandGODASdata,providedbytheNOAA/OAR/ESRLPSL, Boulder,Colorado,USA,fromtheirwebsiteat https://psl.noaa.gov/

• TheCommonOceanReferenceExperiment(CORE.2)GlobalAir-SeaFluxDataset, providedviatheNCARwebsite, https://rda.ucar.edu

• NOAA’sInternationalBestTrackArchiveforClimateStewardship(IBTrACS)data, providedvia https://www.ncdc.noaa.gov/ibtracs

• HURDAT-2besttrackAtlantichurricanedata,providedviatheNationalHurricane Center/NOAAvia https://www.nhc.noaa.gov/data/#hurdat

• Monthlyseaicedatasets,providedbytheNASANationalSnowandIceDataCenter (NSIDC)via https://nsidc.org

• ArchivesofdailyicebergchartsforthenorthwestAtlantic,providedbytheNavigation CenteroftheUnitedStatesCoastGuard,aspartoftheInternationalIcePatrol(IIP)

Therestlessocean

ChapterOutline

1.1Tenbigquestions 3

1.2Organizationvs.chaos 3

1.3Measuringtheocean—Challengesandinternationalorganization 5

1.4Measuringoceancurrents 7

1.4.1Driftmeasurements 7

1.4.2Pointmeasurements 11

1.4.3Profilemeasurements 12

1.4.4Radarmeasurements 14

1.5Estimatingoceancurrents 15

1.5.1Hydrography 15

1.5.2Bottompressurerecorders 17

1.5.3Satellitealtimeters 18

1.5.4Electricalcables 19

1.6Computersimulationofoceancurrents 19

1.7Anoceanofscales 22

1.8Summary 22 References 23 OceanCurrents. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-816059-6.00005-X

Fewpeopledirectlyexperiencethepowerfulinfluenceofourrestlessoceansintheirdailylives, butpublicknowledgeandperceptionsarechanging.Whileeffortstoconservemarine environmentsandecosystemshaveattractedbroadsupport,theroleoftheoceansinclimate changeisnowwidelyappreciated.Ourseasandoceansincreasinglydemandtheattentionof policymakers,rangingfromtheUnitedNations,concernedwithinternationaltreatiesand regulations,tolocalauthorities,concernedwithmanagementofportsandcoastlines.For businessandindustry,ourseasandoceansareintegraltointernationaltrade,renewableenergy, andfisheries.

Thechallengetoscientists,andtooceanographersspecifically,istomeasure,understand,and predictthecharacterofouroceans.Afundamentalaspectofthischaracteristheconstant motionofseawater—oceancurrents.Ranginginstrengthfromjustafewcentimetresper secondinmostplacesto1–2mpersecond(abriskwalkingpace)inafewselectlocations,these currentsconnectwidelyseparatedlocations—spanningregionalseas,thebasinsthatseparate continents,andultimatelytheentireglobalocean.Inrecentyears,this connectivity hasbeen showntobefundamentallyimportantformanydifferentmarineecosystems,andforthefateof ourdiscardedmaterial,suchasourplasticwaste.Inaddition,keyenvironmentalproperties suchastemperatureandconcentrationsofdissolvedsubstancesarestronglycontrolledby oceancurrents.

Glancingdownfromawindowseatonalong-haulflight,theoceanappearsstatic,andyetwe knowthatitisinconstantmotion.So,whydoestheoceanmove?Insimplestterms,theoceanis pushedorpulledby forces associatedwithwinds,Earth’sgravity,andinteractionsbetween Earth,Moon,andSun.Oceancurrentsarealsorelatedtospatialdifferencesofseawater properties(watertemperatureandsaltcontent),interactionsofeddyfluctuations,andinterior frictionalstresses.FurthercomplicatingmattersistheinfluenceofEarth’srotation,leadingtoan evidentturningofcurrentsontimescalesbeyondafewhours.Itisamajorgoalofphysical oceanographerstoquantifyandunderstandhowtheseforcesandinfluencescollectivelydrivethe currents.

Oceancurrentsaremanyandvaried,yetfundamentalprinciplesunderpinacommondynamical frameworkthathelpsustounderstandeachinturn.Followingthisintroductorychapter,we thereforeoutlinethisframework,alongwitharangeofdatasetsandmethods,necessaryto revealandexplainhowtheoceanmoves(Chapter2).Inthefollowing10‘topicchapters’ (Chapters3–12),weintroduceoceancurrentsacrossawiderangeofgeographicalsettings,in eachcaseemphasizinganappliedcontextandimpact.Inaclosing Epilogue,wesummarizeand reviewthebreadthoftheseimpacts,andlookforwardtotheexcitingchallengesthatlieahead forthosewhoseekadeeperknowledgeandunderstandingofoceancurrents.

Inthischapter,westartbyposing10‘bigquestions’,whichprovidealargepartofthe motivationfor Chapters3–12.Wethenhighlightthetensionbetweentheorganizedandchaotic natureofoceancurrents,emphasizingtheintrinsicdispersionofmaterialandproperties.We

Therestlessocean3

nextreviewthechallengeofmeasuringoceancurrents,withafocusonthechallengeof organizingoceanobservationatinternationalscale.Inabriefoverviewofobservational approaches,wedistinguishbetweendirectmeasurementandestimationofoceancurrents. Complementarytoobservationsareincreasinglyrealisticcomputersimulations,providingdata thatweusetotraceflowsthroughouttheocean.Weconcludewithareflectiononthe challengingrangeoftimeandspacescalesimplicitinoceancurrents,andonthe co-developmentoftechnologyandcommunityactivitythatunderpinsourknowledgeand understandingoftherestlessocean.

1.1Tenbigquestions

Associatedwitheachappliedcontext,andthereforefeaturingineachtopicchapter,weposea ‘bigquestion’:

1.HowdoesourplasticendupinsomeofthemostremoteplacesonEarth?(Chapter3)

2.Howdomarinecreaturesexperienceandadapttostrongcurrents?(Chapter4)

3.Whyarethemostproductivefisheriesfoundintheeasternsubtropics?(Chapter5)

4.Howandwheredodestructivecyclonesformovertropicaloceans?(Chapter6)

5.HowdooceancurrentsconnecttheArcticwiththeAtlanticandPacific?(Chapter7)

6.HowdoestheoceaninteractwiththeAntarcticicesheet?(Chapter8)

7.Howdoeswaterandmaterialmovearoundshallowcoastalandshelfseas?(Chapter9)

8.Howdotheoceansconnecttoeachother,andwhydoesthismatter?(Chapter10)

9.Howdoeswatermoveatglobalscale?(Chapter11)

10.Howdoestheoceancirculationcontrolclimate?(Chapter12)

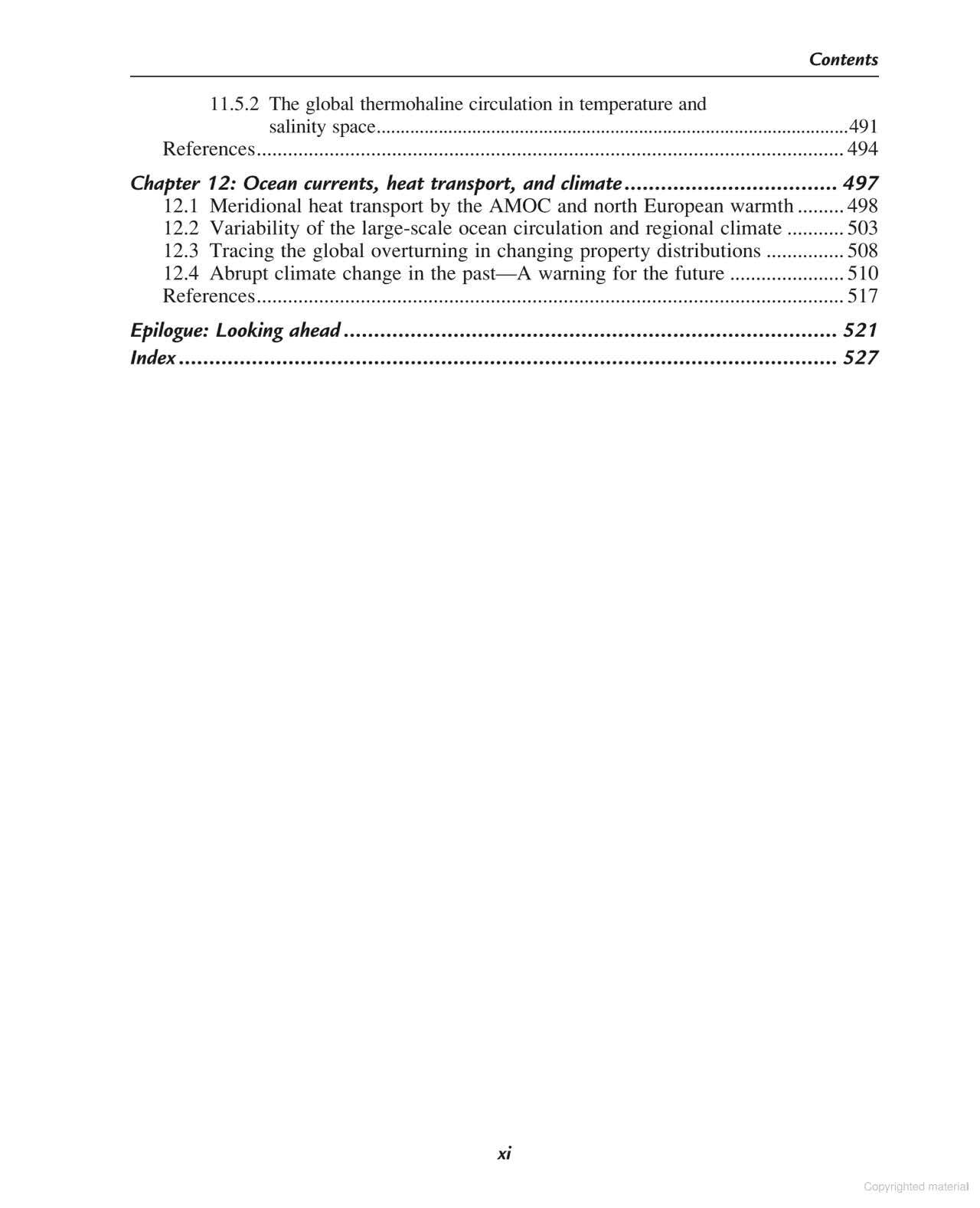

Thesequestionshelptoframeeachtopicchapter,inrelationtoparticulartypesofocean currentandareillustratedin Fig.1.1,introducingthevisualimagerythatweusethroughout. The10panelscombineamixtureofdirectobservationsin(B,D),computersimulations (A,E–H),blendsofobservationandsimulation(C,J),andaschematic(I).Thismixofsources willbeevidentthroughoutsubsequentchapters,andthesearebrieflydiscussedlaterinthis chapter.

1.2Organizationvs.chaos

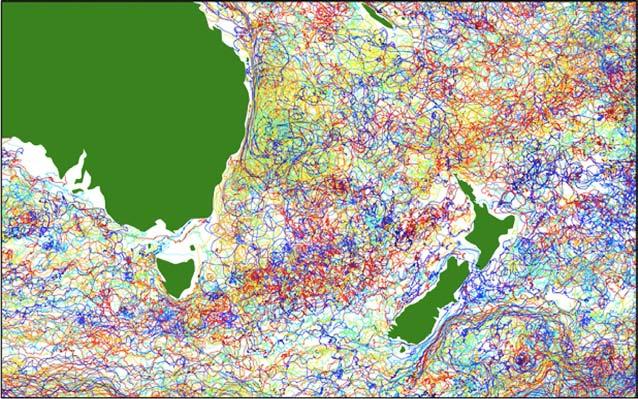

Atraditionalviewistoidentify,describe,andnameindividualcurrentsaroundtheWorld’s oceans.Inthisapproach,theoceanisanorganizedplace,withpredictablecurrentsthatmaybe drawnassmoothflowsonnauticalchart,orevenonaglobe.Whilewewillrespectthis orthodoxapproach,wemuststresstheunpredictabilityoftheflow.Averagingflowsintimeand space,currentsdoindeedemerge,buttheinstantaneousflowfieldisoftenmuchmore complex.Thisinherent chaos isapparentin Fig.1.1BandH,andmoreexplicitlyin Fig.1.2

Fig.1.1

Visualizingthe10bigquestions:(A)garbagepatches(vanSebilleetal.,2015a);(B)passivedriftofjuvenileturtles(Scottetal.,2014); (C)equatorwardwindsoffCalifornia,drivingupwellingandhighproductivityinJune1988;(D)thefrequencyoftropicalcyclones; (E)climatologicalsurfaceflowsinandaroundtheArcticinSeptember,fromahigh-resolutionmodelhindcast;(F)simulatediceberg massaroundAntarcticainanoceanmodelwithinteractiveicebergs (Marshetal.,2015);(G)tidalmixingfrontsinthenorthwest EuropeanshelfinearlyJuly,attheboundarybetweenstratifiedwateroffshoreandmixedwaterinshore;(H)Agulhasleakage(in van Sebilleetal.,2018);(I)schematicelementsofglobaluppercirculation,superimposedonhigh-resolutionbathymetry;(J)Januarysurface airtemperaturedeparturefromzonalmean. Panel(D):DatafromIBTrACS.Panel(J):DataarefromtheNCEP/NCARReanalysis1,averaged over1948–2018.

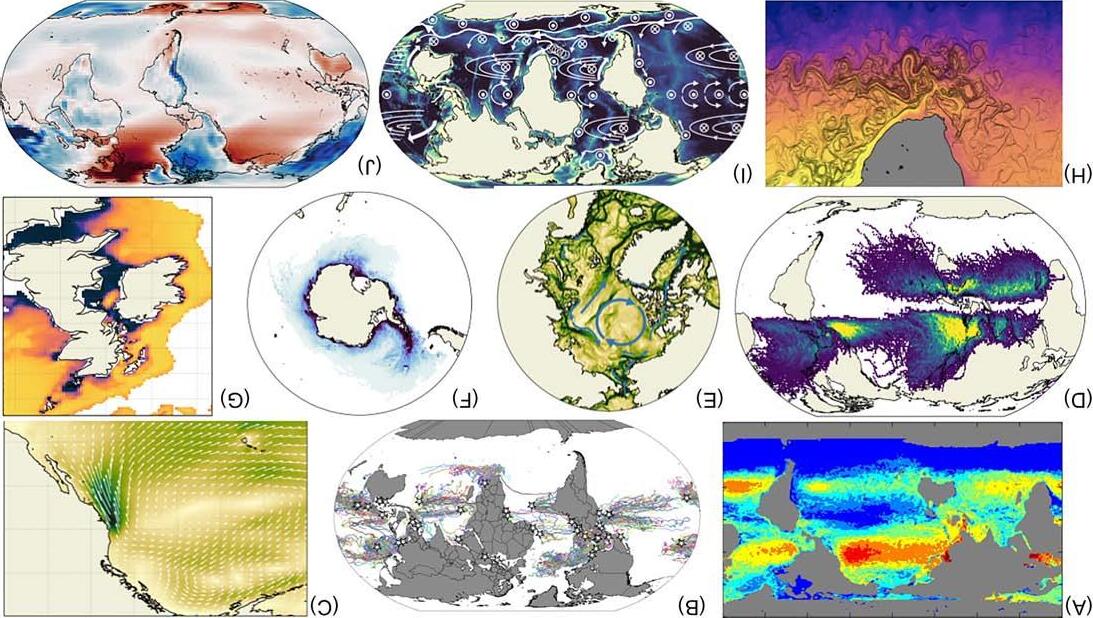

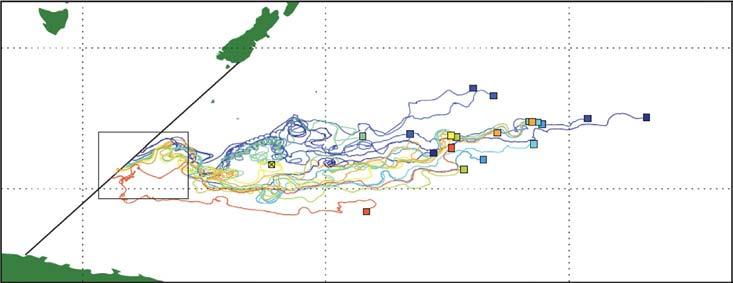

ExampleofchaoticoceandriftintheSouthernOcean;pairsofbuoys,deployed15mapartonthe sternofaresearchship,separatedbyupto200kminamonth. FromvanSebille,E.,Waterman,S., Barthel,A.,Lumpkin,R.,Keating,S.R.,Fogwill,C.,Turney,C.,2015b.Pairwisesurfacedrifterseparationinthe westernPacificsectoroftheSouthernOcean.J.Geophys.Res.Oceans120,6769–6781. https://doi.org/10. 1002/2015JC010972.

(vanSebilleetal.,2015b),whichillustrateshow10pairsofdriftingbuoysmoveapartovera periodof7monthsintheSouthernOcean,whileallmovinginthesameeastwarddirectionat roughlysimilarspeeds.Eachpairwasdeployedatthesamelocationandtimeonaresearch expeditionboundforthepackiceofAntarctica.Reportingpositionshourlyviasatellite,drifter pairsstayclosetogetheratfirst,buttheirinevitableseparationconformstoourunderstandingof chaoticoceancurrents.This dispersion ofeverythingcarriedbycurrentsgovernsmany importantprocessesandcanleadtosomesurprisingphenomena,whichwehighlightin subsequentchapters.

1.3Measuringtheocean—Challengesandinternationalorganization

Thescientificmethodstartswithmeasurement.Therearemanydifferentwaystomeasure oceancurrents,butoceanographersmustcontendwithsomemajorchallengesinworkingat sea.Theoceanisvastanddiverse.Consequently,measurementsinajustafewselectlocations maynotberepresentativeoftheoceanasawhole.Shipsareveryexpensivetooperate,with costsforopen-oceanvesselseasilyintheorderof $40kperday.Theoceanishostileand unpredictable,withmanyworkingdays—andsometimesscientificequipment—losttobad weather.Thisequipmentmustbeengineeredverycarefullytowithstandtheenormous pressuresofthesub-surfaceocean.Theoceaniseverywherecorrosive,withimplicationsforall metalcomponentsinoceanographicequipment.Theoceanisopaquetolightandothertypesof

Fig.1.2

electromagneticradiation,sowehavelimitedcapabilitytomeasurebeyondtheimmediate vicinityofmostequipment.Mostoftheoceanbelongstonobody,withconflictingclaimsinthe vicinityofsomenations.Consequently,itisnotalwaysclearwhocanorshouldmakewhich measurements,whenandwhere.

Inthefaceofsomanymeasurementchallenges,manysmartmethodshavebeendevelopedand refinedoverthelastcenturyorso.Justasimportant,internationalcooperationhasbeen developedandrefinedthroughaseriesofmajorprogrammessincethe1950s.TheInternational GeophysicalYear(IGY)spanning1957–58wasanambitiousundertakingthatincluded oceanographyalongside10otherearthsciences.Intherealmofphysicaloceanography,IGY activitiesbroadlyspannedtheAtlantic,Pacific,Indian,andSouthernOceans.Itwasalready understoodthattheoceanmovedindifferentwaysatdifferentdepths.Oceanographers wonderedwhetherandhowtheAtlanticmighthavechangedsince1920’sand1930’ssurveys bytheGermanSurveyShip Meteor,ledbyGeorgWust,oneofthegreatpioneersof oceanography.Mindfuloftheirsuccessors,IGYscientistspaidparticularattentionto measurementsthatwouldberepeatedinthefollowingdecades.FollowingsoonafterIGY during1959–65,theInternationalIndianOceanExperiment(IIOE)addressedbiologicalas wellasphysicaloceanography.IIOEalsoprovidedanimpetustothedevelopmentofmarine scienceintheregion,underthecoordinationofthenewIntergovernmentalOceanographic Commission(IOC)oftheUnitedNationsEducational,ScientificandCulturalOrganization (UNESCO).

Throughoutthe1970s,theGeochemicalOceanSectionsStudy(GEOSECS)addressedthe detectionofdissolvedchemicalsthroughouttheocean,fromsurfacetoabyss,inAtlantic, Indian,andPacificoceans.Concentrationpatternsfordifferentchemicalsrevealedhowwater movesacrossgreatdistancesonlong(decadaltocentennial)timescales,andtherateatwhich differentbodiesofseawatermixtogether.The1990ssawalandmarkachievementwiththe WorldOceanCirculationExperiment(WOCE,1990–97),whichestablishedafullyglobal surveyoftheoceans,revisitingmanyIGYlocationstorevealavarietyofchangessincethelate 1950s.Bynow,measurementsfromshipswerecomplementedbysatellitemeasurementsofsea surfaceproperties,andincreasinglyambitiouscomputermodelsimulations.

OverlappingwiththelatteryearsofWOCE,andintegraltoanongoingsynthesisofWOCE data,theClimateVariabilityandPredictability(CLIVAR)componentoftheWorldClimate ResearchProgramme(WCRP)waslaunchedin1995,initiallyscheduledfor15years,but currentlyongoing.CLIVARsupportstheinternationalcoordinationoflarge-scaleobserving andmodellingactivitieswithaparticularfocusonthevariabilityandpredictabilityofclimate, onseasonaltocentennialtimescales,whichisdeterminedtoalargeextentbychangesinthe ocean.

DespitethecoordinationofCLIVAR,itbecameapparentthatanewframeworkspecifictoglobal oceanobservationwasneededintheyearsfollowingWOCE,tooptimizenationalcommitments

tooceanographicobservation,standardizethesuiteofoceanmeasurements,andharmonizedata sharing.TheGlobalOceanShip-basedHydrographicInvestigationsProgram(GO-SHIP) emergedinthe2000s.From2007,apanelwasformedtodevelopanewstrategyforsustained globalrepeathydrography,basedaroundWOCE,integraltowhicharethestandardsandlinesof communicationnecessaryforeffectivedatamanagementandsynthesis.Witha‘2012–23 Survey’ofGO-SHIPtrans-oceanreferencesectionsestablished(see www.go-ship.org),new measurementsareavailableforcomparisonwiththosefromWOCE,20–30yearsearlier.

ComplementarytoGO-SHIP,thedecade-longGEOTRACESprogrammewaslaunchedin January2010.GEOTRACESisprovidingthefirstcoordinatedglobalsurveyofdissolved chemicals.Withmorecompleteglobalsampling,wecanbetterunderstandthesources, transports,andsinksofkeychemicalspeciesthatarevitalforlife.Alsoprovidingimportant tracers ofoceancurrents(andmixing)arethelarge-scaledistributionsofvarioustrace elementsandtheirisotopicvariantsthataredetectedatverylowconcentrations.The GEOTRACESsections(see geotraces.org)arerathermorecomplexandconvolutedthanthose ofGO-SHIP,asthescientificobjectivesarespecifictokeylocations,suchasmid-oceanridges andcoastalzones.

1.4Measuringoceancurrents

Wenowturnspecificallytothemeasurementofoceancurrents.Wedistinguishthe measurementofmovement—ofwaterandassociatedquantities/properties—throughtimeand space,fromthedirectmeasurementofoceancurrentsinsitu,instantaneouslyorthroughtime. Westartwiththeformercase—measuringthe drift duetooceancurrents.Wethenreview currentmeasurementsmadeatafixedpoint,inprofile,orwithground/ship-basedradar.

1.4.1Driftmeasurements

Perhapsthesimplestobservationofanoceancurrentistheresultingdrift.Consideracorked bottledeployedfromaboat.Thebottlemaycontainamessagethatrecordsthetimeand locationofdeployment.Thebottleisbuoyantandfloatsattheseasurface.Intime,itdrifts elsewhere.Ifthebottleisretrievedandweopenittodiscoverwheretheboatdeployedit,then wemightsimplydrawanarrowfromthepointofdeploymenttothepointofretrieval,wehavea direction.Ifwealsoreadthetimeof‘departure’andcombinethatwithourcurrentlocationand time,wecanworkoutastraight-linedistancetravelledandsimplydividethisbytimeelapsedto geta speed.Withspeedanddirection,wehaveatime-averaged currentvector.Ofcourse, objectsintheoceandonotdriftinarrow-straightlines,butinevitablymeanderalongunique trajectories.Anaccuraterecordofthebottletrajectorywouldthusrevealamoredetailed pictureofoceancurrentsvaryinginbothtimeandspace.

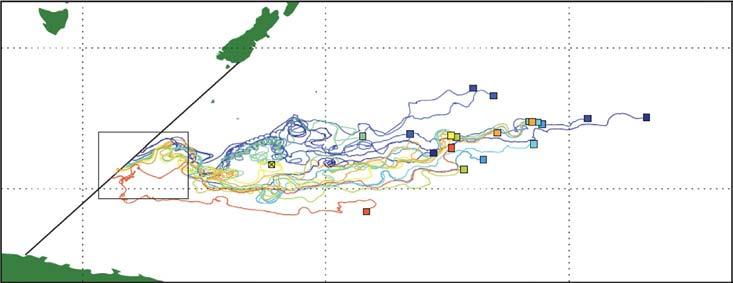

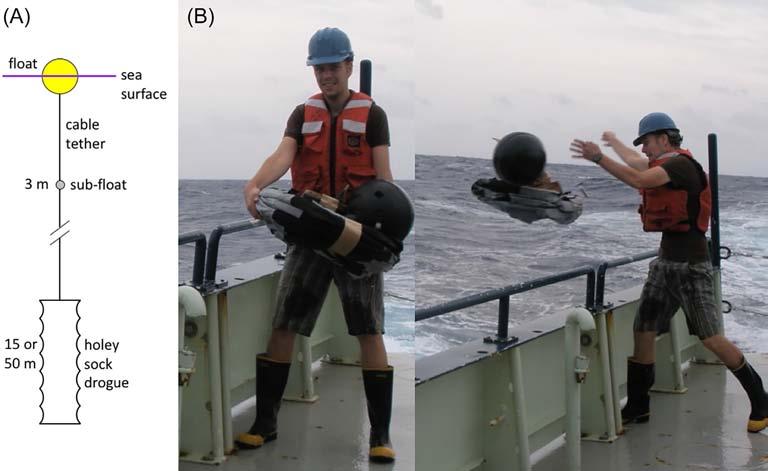

Sincethelate1970s,oceanographershaveorganizedthemeasurementofnear-surfaceflow with driftingbuoys.Apartfromtechnicalchallengesinbatteriesandsatellitecommunication, theseoceanographersfacedchallengesabouthowdeepreachingtomakethesebuoys. Nowadays,thereareessentiallytwotypesofbuoys:thosethataimtomeasurethecurrentsnear theabsolutesurfaceoftheoceanwhereoceanwavesandwindscanexertasubstantial influence,andbuoysthatmeasurethecurrentsaveragedovertheupperfewtensofmetres. Basicdesignanddeploymentofthelattertypeisillustratedin Fig.1.3.Thesesurfacebuoysare drogued todriftwiththecurrentsatatargetdeptharound15m(Fig.1.3A),toavoiddrifting withcurrentsveryclosetothesurface.Thedroguethenactsasaseaanchor,andthebuoy trajectoryisrepresentativeofthecurrentsthattransportmostheatandnutrientsintheupper ocean.However,forbuoyantmaterial(seaweed,debris,plastics,etc.),itispreciselythesurface driftthatweneedtomeasureandunderstand.Inthatcase,driftersneedtobeasflataspossible, withoutstickingtoohighabovethewaterbecausethentheywouldsail,ratherthandrift. Technologicaldevelopmentofverythinbuoysismovingatarapidpace,withthelatest iterationofdrifters(the Stokesdrifters fromFloridaStateUniversity)beingonlyafew centimetresthick.

Throughoutthisbook,wewillmostlybereferringtothetrajectoriesofdroguedbuoys,andthen specificallytheSVP(SurfaceVelocityProgram)type.Withtheadventofaccuratesatellite

(A)Drogueddriftingbuoyinverticalprofile;(B)drifterdeploymentofftheBahamas. Photos:Chris Meinen.

Fig.1.3

Fig.1.4

AllsouthwestPacifictrajectoriesofGDPbuoys. FromvanSebille,E.,2014.Adrift.org.au—afree,quickand easytooltoquantitativelystudyplanktonicsurfacedriftintheglobalocean.J.Exp.Mar.Biol.Ecol.461,317–322.

trackinginthe1970s,driftertechnologydevelopedrapidlywithintheSVP(Niileretal.,1995). Driftmeasurementssince1979havebeencoordinatedviatheGlobalDrifterProgram(GDP). However,whilethesebuoysallstartoutwithadrogue,theyoftenlosetheirdrogueduring stormsandheavyswell,whentheconnectionbetweendrogueandbuoysnaps.Soeventhe datasetoftheGDPisacombinationofdroguedandun-drogueddrifters.

AcomplexpatternofoceancurrentsemergesfromanalysisoftheGDPdataset.Asa regionalexample, Fig.1.4 showsallGDPdriftertracksforthesouthwestPacific.Someorderis apparentinthechaos,suchasoffthecoastsofeasternAustraliaandNewZealand,where currentsareconstrainedbycoastlinesandsteepoceanbottomslopes,butchaosisotherwise dominant.

Deeperoceandriftisamorechallengingmeasurement,butofgreatimportancefor understandingoceancurrentsatglobalscale.Theprimarychallengeistotargetflowsatgreat depths,forwhichadrogueisquiteimpractical.Thekeyto‘parking’anoceandrifteratsuch depthistoneutralizeitsbuoyancy,ordensity(formoredetailsondensity,see Chapter2).Ifa drifterismorebuoyant(orlessdense)thansurroundingwater,itwillrise;ifitislessbuoyant(or denser),itwillsink;ifitisexactlyasbuoyantasthesurroundingwater—i.e.thesamedensity, orwith neutralbuoyancy—itwillremaininsitu(atconstantdepth).Seawatergetsgradually denserwithdepth,formorethanonereason.Onereasonisthesheerweightofwateraboveany givendepth,applyingapressuretotheslightlycompressibleseawater;butwateralsogets denserastemperaturefallsorassaltconcentration(salinity)increases.Thecombinationof

pressure,temperature,andsalinitythusdeterminesseawaterdensity,andprecisehydrographic measurementsindicatehowdensityconsequentlyvaries,upanddownthewatercolumn,and fromplacetoplace.

Densityvariationsaremuchgreaterintheverticaldirectionthanhorizontally,soifa‘float’can bemadeasbuoyantasthewateratagivendepth,itwillsubsequentlydriftawayat approximatelythatdepth.Theopenoceanistypically4000–6000mdeep,andtargetdepthsfor followingdeepcurrentsaretypicallyintherange1000–3000m.Havingachievedneutral buoyancy,thesecondchallengeistoobtaininformationonposition,ideallyatregularintervals. Thisisadifficultproblem,ascommunicationfromgreatdepthdemandsinnovativetechnology. Onemethodreliesonoceanacoustics,assoundwavescanpotentiallytravelgreatdistancesin theocean.Thetraveltimeofsoundsignalsmaythusbeusedtofixthelocationofasub-surface float.

Thefirstneutrallybuoyantfloatfortrackingwatermovementsatgreatdepthwasinventedin themid-1950sbyBritishoceanographerJohnSwallow,andfamouslyusedtomakethefirst directobservationsofstrongequatorwardflowsdeepbeneaththeGulfStream(Swallowand Worthington,1961).Thebodyofthe Swallowfloat comprisedapairofthinnedaluminium tubes,eachoflength3m.Beforedeployment,Swallowfloatswerepreparedonthedeck,ina tankofwaterwithknowndensity,toensureneutralbuoyancyforthatdensity,i.e.thatthefloat neitherrisesnorsinks.Inthepreparations,furtheradjustmentsmustbemadeforthe compression(undertargetdepthpressure)ofbothseawaterandthefloatitself.Afterbeing loweredonawiretothetargetdepth,toensurenoleaksofthesalinefluidrequiredforneutral buoyancy,thefloatcouldbefullydeployed.Hydrophonesdeployedoverthesideoftheship wouldthenlistenforsignalsfromanacoustictransmitterhousedonthefloat.Byobtaininga seriesoffixesforpositionanddepth,deepcurrentscouldbeinferredfromdriftofthefloat.It waswithmeasurementsthusobtainedoveraperiodofaround2weeks,March–April1957,that thedeepflowswerefirstdirectlyobserved.

SubsequenttothepioneeringworkofSwallowandWorthington,theSoundRangingAnd Fixing(SOFAR)channel,locatedatdepthsofaround1000mthroughoutmuchoftheocean, wasexploitedusing SOFARfloats thatemittedsoundpulsesforremotereception.Bythe1990s, SOFARfloatsweresupersededby RangeandFixingofSound(RAFOS)floats (Rossbyetal., 1986).RAFOSfloats,movingatdepth,listenforsoundsignalsfrommultiplesub-surface beacons,muchlikemodern-dayGPS.Theyareprogrammedtoreturntothesurfaceatmission end,whereupontheytransmitthesepositionalfixestoshoreviasatellite.Itwasinrequiringless batterypoweronthefloatsthemselvesthatRAFOStechnologysupersededthatofSOFAR.Ina pioneeringmid-1990’sexperiment, BowerandHunt(2000) deployed26RAFOSindeepflows attwolevelsbeneaththeGulfStream,offtheeastseaboardoftheUnitedStates.Driftingforup to2years,thefloatsrevealedcomplexpathwaysthroughtheregionasdensewatermoveseither alongthecontinentalslopeormixesintothebasininterior.

1.4.2Pointmeasurements

Considernowthetime-varyingoceancurrentatafixedlocation,suchasamooring,orastable platformsuchasanOceanWeatherShip.Suchascenarioistypicalofthefixedpoint,or Eulerian,measurementsobtainedwithmoderncurrentmeters.Fixed-pointcurrentmeterswork onvariousdifferentoperatingprinciples.Themostcommonplace RotorCurrentMeters (RCMs) operateonmechanicalprinciples.Incoastalorestuarineenvironments,weuseRCMs thatareconstructedfromtitaniumandpolymers,toresistcorrosion,limitdimensions,and minimizeweight,suchasillustratedin Fig.1.5.Flowpasttheinstrumentdrivestheimpeller (yellowcomponent in Fig.1.5)torotate,generatingavoltageinproportiontotherateof rotation.Thecurrentmeterbodilyalignswiththewaterflow,andanon-boardcompassrecords thisorientation.Currentspeedanddirectionarethusmeasuredatregularintervalsandthisdata isloggedduringaperiodofdeployment.Tetheredtowire,theselightweightinstrumentsmay beloweredthroughthewatercolumntoobtainacurrentprofileormaintainedatafixeddepthto obtainatimeseries.

Inthedeepocean,currentmetersneedtomeettwocriteria:resiliencetoextremeenvironmental conditions(corrosionandhighpressure)andthecapabilitytointernallyrecordalargeamount ofdatawithminimalbatterypower(formonth-toyear-longdeployments).Thedevelopmentof

Fig.1.5

LightweightCurrentMeter(ValeportModel105),ownedandusedbytheUniversityofSouthampton. Photoscourtesyofauthor(Marsh).