LIST OF CONTRIBUTORS

Meghan Bretz

Director

St. Vincent Evansville & University of Evansville Physical Therapy Neurologic Residency

Rehabilitation

Ascension St. Vincent Evansville, Indiana

Adjunct Faculty

Physical Therapy

University of Evansville Evansville, Indiana

Tzurei Chen

Assistant Professor Physical Therapy

Pacific University Hillsboro, Oregon

Kevin Chui

Director and Professor

School of Physical Therapy and Athletic Training

Pacific University Hillsboro, Oregon

Elizabeth Ennis

Associate Professor, Chair Physical Therapy

Bellarmine University Louisville, Kentucky Coowner

All About Families, PLLC Louisville, Kentucky

Mary Kessler

Dean

College of Education and Health Sciences

Associate Professor

Physical Therapy

University of Evansville Evansville, Indiana

Jordana Lockwich Assistant Professor

Physical Therapy

University of Evansville Evansville, Indiana

Suzanne Martin Professor Emerita Physical Therapy

University of Evansville Evansville, Indiana

Jason Pitt Assistant Professor

Physical Therapy

University of Evansville Evansville, Indiana

Preface, vii

List of Contributors, viii

SECTION 1: Foundations

1 The Roles of the Physical Therapist and Physical Therapist Assistant in Neurologic Rehabilitation, 1

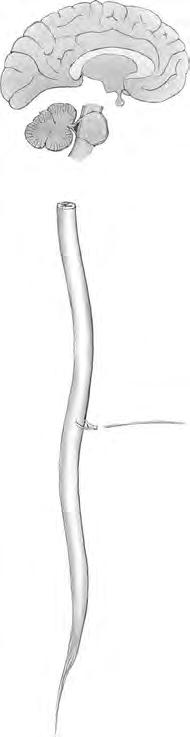

2 Neuroanatomy, 12

3 Motor Control and Motor Learning, 41

4 Motor Development, 66

SECTION 2: Children

5 Positioning and Handling to Foster Motor Function, 103

6 Cerebral Palsy, 144

7 Myelomeningocele, 189

8 Genetic Disorders, 220

9 Autism Spectrum Disorder, 272

SECTION 3: Adults

10 Proprioceptive Neuromuscular Facilitation, 294

11 Stroke, 348

12 Traumatic Brain Injuries, 423

13 Spinal Cord Injuries, 453

14 Other Neurologic Disorders, 525

Index, 563

This page intentionally left blank

The Roles of the Physical Therapist and Physical Therapist Assistant in Neurologic Rehabilitation SECTION

OBJECTIVES

After reading this chapter, the student will be able to:

1. Discuss the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health and its relationship to physical therapy practice.

INTRODUCTION

The practice of physical therapy in the United States continues to change to meet the increased demands placed on service provision by reimbursement entities and federal regulations. The profession has seen an increase in the number of physical therapist assistants (PTAs) providing physical therapy interventions for adults and children with neurologic deficits. PTAs are employed in outpatient clinics, inpatient rehabilitation centers, extended-care and pediatric facilities, school systems, and home health care agencies. Traditionally, the rehabilitation management of adults and children with neurologic deficits consisted of treatment derived from the knowledge of disease and interventions directed at the amelioration of patient signs, symptoms, and functional impairments. Physical therapists (PTs) and PTAs “help individuals maintain, restore, and improve movement, activity, and functioning, thereby enabling optimal performance and enhancing health, well-being, and quality of life” (APTA, 2014).

Physical therapy ser vices are provided across the lifespan to children and adults “who have or may develop impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions” (APTA, 2014). These limitations develop as a consequence of various health conditions including those of the “musculoskeletal, neuromuscular, cardiovascular, pulmonary, and/or integumentary system” or the negative consequences of the interaction of personal and environmental factors on human performance (APTA, 2014).

Sociologist Saad Nagi developed a model of health status that has been used to describe the relationship between health and function (Nagi, 1991). The four components of the Nagi Disablement Model (disease, impairments, functional limitations, and disability) evolve as the individual

2. Explain the role of the physical therapist in patient/client management.

3. Describe the role of the physical therapist assistant in the treatment of adults and children with neurologic deficits.

loses health. Disease is defined as a pathologic state manifested by the presence of signs and symptoms that disrupt an individual’s homeostasis or internal balance. Impairments are alterations in anatomic, physiologic, or psychological structures or functions. Functional limitations occur as a result of impairments and become evident when an individual is unable to perform everyday activities that are considered part of the person’s daily routine. Examples of physical impairments include a loss of strength in the anterior tibialis muscle or a loss of 15 degrees of active shoulder flexion. These physical impairments may or may not limit the individual’s ability to perform functional tasks. Inability to dorsiflex the ankle may prohibit the patient from achieving toe clearance and heel strike during ambulation, whereas a 15-degree limitation in shoulder range of motion may have little impact on a person’s ability to perform self-care or dressing tasks.

According to the disablement model, a disability results when functional limitations become so great that the person is unable to meet age-specific expectations within the social or physical environment ( Verbrugge and Jette, 1994). Society can erect physical and social barriers that interfere with a person’s ability to perform expected life roles. The societal attitudes encountered by a person with a disability can result in the community’s perception that the individual is handicapped. Fig. 1.1 depicts the Nagi classification system of health status.

The second edition of the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice incorporated the Nagi Disablement Model into its conceptual framework of physical therapy practice. The use of this model directed PTs to focus on the relationship between impairment and functional limitation and the patient’s ability to perform everyday activities within the patient’s home and community (APTA, 2003).

Impairment Functional limitation

Pathology Alteration of structure and function

Difficulty performing routine tasks

Societal disadvantage of disability Disease

Significant functional limitation; cannot perform expected tasks

Fig. 1.1 Nagi classification system of health status.

individuals with the same medical diagnosis might have very different functional outcomes and levels of participation based on environmental and personal factors.

Fig. 1.2 Model of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health. (From Cech D, Martin S: Functional movement development across the life span, ed 3, St. Louis, 2012, Elsevier.)

The World Health Organization (WHO) developed the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), which was endorsed by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) in 2008. This system provides an updated frame of reference for physical therapy practice and standard language to describe health, function, and disability at both the individual and population level, and is incorporated into the third edition of the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice. Fig. 1.2 illustrates the ICF model. Health is much more than the absence of disease; rather, it is a condition of physical, mental, and social well-being that allows an individual to participate in functional activities and life situations ( WHO, 2013; Cech and Martin, 2012). A biopsychosocial model of health is central to the ICF and defines a person’s health status and functional capabilities by the interactions between one’s biological, psychological, and social domains (Fig. 1.3). This conceptual framework recognizes that two

The ICF also presents functioning and disability in the context of health and organizes the information into two distinct parts. Part 1 addresses the components of functioning and disability as they relate to the health condition. The health condition (disease or disorder) results from the impairments and alterations in an individual’s body structures and functions (physiologic and anatomic processes). Activity limitations present as difficulties performing a task or action and encompass physical as well as cognitive and communication activities. Participation restrictions are deficits that an individual may experience when attempting to meet social roles and obligations within the environment. Functioning and disability are therefore viewed on a continuum in which functioning encompasses performance of activities and participation and disability implies activity limitations and restrictions in one’s ability to participate in life situations such as employment, education, or relaxation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017; WHO, 2013).

Part 2 of the ICF recognizes the contextual factors “external environmental factors (e.g., social attitudes, architectural characteristics, legal and social structures, and climate and terrain)” and internal personal factors (age, sex, social, and educational background, coping strategies, profession, life experiences, and other factors) that influence a person’s response to the presence of a disability and the interaction of these factors on one’s ability to participate in meaningful activities (APTA, 2014). Fig. 1.4 provides a diagram of the ICF Model of Functioning and Disability. All factors must be considered to determine the impact, both positive and negative, these factors have on function and participation (APTA, 2014; WHO, 2013).

Fig. 1.3 The three domains of function—biophysical, psychological, sociocultural—must operate independently as well as interdependently for human beings to achieve their best possible functional status. (From Cech D, Martin S: Functional movement development across the life span, ed 3, St. Louis, 2012, Elsevier.)

Part 2: Contextual factors Part 1: Functioning and disability

Fig. 1.4 Structure of the International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF) Model of Functioning and Disability. (Adapted from [http://www.apta.org], with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association. © 2019 American Physical Therapy Association. All rights reserved.)

The ICF emphasizes enablement rather than disability (Cech and Martin, 2012). In the ICF model, there is less focus on the cause of the medical condition and more emphasis directed to the impact that activity limitations and participation restrictions have on the individual. As individuals experience a decline in health, it is also possible that they may experience some level of disability. Thus the ICF “mainstreams the experience of disability and recognizes it as a universal human experience” ( WHO, 2002).

An ICF for Children and Youth has been developed to provide greater detail for children from birth to age 18 years. This document addresses the “body functions and structures, activities, participation, and environments specific to infants, toddlers, children, and adolescents” and provides a framework for common language and documentation as it relates to health status and disability in children (APTA, 2014; WHO, 2007). Fig. 1.5 provides an example of the ICF applied to children w ith cerebral palsy, autism, and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder.

The third edition of the Guide to Physical Therapist 3.0 recognizes the critical roles that PTs and PTAs play in providing “rehabilitation and habilitation, performance enhancement, and prevention and risk-reduction services” for patients and the overall population (APTA, 2014). Additionally, as professionals we play a critical role in developing standards for our practice and in recommending health care policy to ensure access, availability, and quality, patient-centered physical therapy care (APTA, 2014).

It is important that therapists continue to appreciate our role in optimizing patient function as various functional skills are needed in domestic, vocational, and community environments. Within the third edition of the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice 3.0 (APTA, 2014), functioning is defined as “an umbrella term for body functions, body structures, activities and participation. Functioning is the positive

interaction between an individual with a health condition and that individual’s environmental and personal factors” (APTA, 2014). Individuals often define themselves by what they are able to accomplish and how they are able to interact in the world (Cech and Martin, 2012). Function “comprises activities that an individual identifies as essential to support his or her physical, social, and psychological well-being and to create a personal sense of meaningful living” (APTA, 2014). Function is related to age-specific roles in a given social context and physical environment and is defined differently for a child of 6 months, an adolescent of 15 years, and a 65-year-old adult. Factors that contribute to an individual’s functional performance include personal characteristics (age, race, sex, level of education), physical ability, sensorimotor skills, emotional status (depression, anxiety, self-awareness and self-esteem), and cognitive ability (intellect, motivation, concentration, and problem-solving skills). The environment in which the adult or child lives and works, such as one’s home, school, or community, social supports, and the social and cultural expectations placed on the individual by the family, community, or society all impact performance of functional tasks and quality of life (APTA, 2014; Cech and Martin, 2012).

THE ROLE OF THE PHYSICAL THERAPIST IN PATIENT MANAGEMENT

As stated earlier, PTs are responsible for providing rehabilitation, habilitation, and services to maintain health and function, prevent functional decline, and in individuals who are healthy enhance performance (APTA, 2014). Ultimately, the PT is responsible for performing a review of the patient’s history and systems, and for administering appropriate tests and measures to determine an individual’s need for physical therapy services. If after the examination the PT concludes

Body functions/Body structures

• Mental functions

• Sleep pattern

• Pain

• Vision and hearing

• Physical fitness

• Control of movements

• Structures of the nervous system

• Structures related to movement

• Structures involved in voice and speech

Neurodevelopmental disorders: cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder

Activities

• Learning and applying knowledge

• Communication

• Eating and drinking

• Dressing

• Mobility

• Doing chores

Participation

• Playing with peers

• Going to the movies

• Attending school

• Playing team sports

• Dating

• Finding a job/working

Environmental factors

• Family, peers, and social support

• Adapted toys

• Sound/light quality

• Assistive technologies

• Societal attitudes

• Health, education, social services

• Policies

Personal factors

• Motivation

• Priorities and goals

• Age-developmental stage

• Personal interests

Fig. 1.5 The International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health biopsychosocial model applied to neurodevelopmental disorders. (From Schiariti V, Mahdi S, Bolte S: International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health Core Sets for cerebral palsy, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder, Dev Med Child Neurology 60:933–941, 2018.)

that the patient will benefit from services, a plan of care is developed that identifies the goals, expected outcomes, and the interventions to be administered to achieve the desired patient outcomes (APTA, 2014). The PT may also determine that the patient is not appropriate for physical therapy services and will recommend referral or consultation to another health care provider.

The steps the PT utilizes in patient/client management are outlined in the third edition of the Guide to Physical Therapist Practice, and include examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, interventions, and outcomes. The PT integrates these elements to optimize the patient’s health, function, or physical performance. Fig. 1.6 identifies the element of patient/client management. In the examination, the PT collects data through a review of the patient’s history and a review of systems, and then administers appropriate tests and measures to determine the patient’s need for services (APTA, 2014). The PT evaluates the data, interprets the patient’s responses to tests and measures, and integrates that data with information obtained during the review of history and systems. Within the evaluation process, the therapist establishes a physical therapy diagnosis based on the patient’s level of impairment and functional limitations. A differential diagnosis (a systematic process to classify patients into diagnostic categories) may be used. When PTs provide a differential diagnosis, they do so with consideration of the impact of the health condition on system function, especially the movement system, and take into consideration the entire person (APTA, 2014). Once the diagnosis is established,

EXAMINATION

EVALUATION

DIAGNOSIS

PROGNOSIS

INTERVENTION

OUTCOMES

Fig. 1.6 The elements of patient/client management. (Adapted from [http://www.apta.org], with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association. © 2019 American Physical Therapy Association. All rights reserved.)

the PT develops a prognosis, which is the predicted level of functional improvement and an estimate to the amount of time needed to achieve those levels. As the PT determines the patient’s prognosis, he or she must consider what the patient is capable of functionally, and what is likely to be habitual for the patient. Patient motivation is important to consider during this process. Therefore the PT must understand “the difference between what a person currently does and what the person potentially could do” as he or she makes a prognosis and develops realistic, achievable functional goals and outcomes (APTA, 2014). It is also important to note that the patient must be an active participant in this process and the PT must follow the decisions made by the patient as they relate to what constitutes meaningful function (APTA, 2014).

Inter vention is the element of patient management in which the PT or the PTA interacts with the patient through the administration of “various interventions to produce changes in the [patient’s] condition that are consistent with the diagnosis and prognosis” (APTA, 2014). Interventions are organized into nine categories: “patient or client instruction (used with every patient and client and in every practice setting); airway clearance techniques, assistive technology, biophysical agents; functional training in self-care and domestic, work, community, social, and civic life; integumentary repair and protection techniques; manual therapy techniques; motor function training; and therapeutic exercise” (APTA, 2014). The PT must prescribe the type and intensity of the interventions as well as the method, mode, duration, frequency, and progression. Reexamination of the patient may be necessary and includes performance of appropriate tests and measures to determine if the patient is progressing with treatment, if modifications in the techniques administered are needed, or if the episode of care is complete. “Outcomes are the actual results of implementing the plan of care that indicate the impact on functioning (body functions and structures, activities, and participation)” (APTA, 2014). The PT must determine the impact selected interventions have had on the following: disease or disorder, impairments, activity limitations, participation, risk reduction and prevention, health, wellness, fitness, societal resources, and patient satisfaction (APTA, 2014).

The development of the plan of care is the final step in the examination, diagnostic, and prognostic process. It is developed in collaboration with the patient, and if necessary other individuals who are involved in the patient’s care. Goals should be developed to impact functioning (body functions and structures, activities, and participation) and should be objective, measurable, functionally oriented, time measurable, and meaningful to the patient. Goals may be written as short or long term depending on the practice setting. The plan of care must also discuss the patient’s discharge from services, “conclusion of the episode of care” and follow-up visits or referrals needed (APTA, 2014). If a patient has not achieved his or her goals, a report of the patient’s current status and rationale for discontinuation of services is provided.

Other aspects of patient/client management include coordination, “the working together of all parties involved

with the patient,” communication, and documentation of services provided (APTA, 2014). Documentation includes any and all entries into the patient’s health record and should include the services provided and the patient’s response to treatment administered. All documentation for physical therapy services should follow the APTA’s Guidelines. (APTA, 2014).

Interventions are designed to produce changes in a patient’s condition. The PT will select interventions based on information obtained in the examination and that are based on the patient’s current condition and prognosis. Physical therapy interventions are designed to optimize patient function, emphasize patient education and instruction, and promote individual health, wellness, and fitness with the goal of preventing reoccurrence of the condition. Interventions are administered by the PT and when indicated by others involved in the patient’s plan of care. PTAs may be “appropriately utilized in components of the intervention and in collection of selected examination and outcomes data” (APTA, 2018a). All other tasks remain the sole responsibility of the PT.

The guidelines for direction and supervision of PTAs follow those suggested by Dr. Nancy Watts in her 1971 article on task analysis and division of responsibility in physical therapy ( Watts, 1971). This article was written to assist PTs with guidelines for delegating patient care activities to support personnel. Although the term delegation is not used today because of the implications of relinquishing patient care responsibilities to another practitioner, the principles of patient/client management, as defined by Watts, can be applied to the provision of present-day physical therapy services. PTs and PTAs unfamiliar with this article are encouraged to review it because the guidelines presented are still appropriate for today’s clinicians and are referenced in APTA documents.

THE ROLE OF THE PHYSICAL THERAPIST ASSISTANT IN TREATING PATIENTS WITH NEUROLOGIC DEFICITS

There is little debate as to whether PTAs have a role in treating adults with neurologic deficits, as long as the individual needs of the patient are taken into consideration and the PTA follows the plan of care established by the PT. PTAs are the only health care providers who “assists a physical therapist in practice” (APTA, 2018a). The primary PT is still ultimately responsible for the patient, both legally and ethically, and is responsible for the actions of the PTA relative to patient management that can include the performance of selected interventions and the collection of certain examination and outcomes measures (APTA, 2018a). The APTA has identified the following responsibilities as those that must be performed exclusively by the PT (APTA, 2018a):

1. Interpretation of referrals when available

2. Initial examination, evaluation, diagnosis, and prognosis

3. Development or modification of the plan of care, which includes the goals and expected outcomes and is based on results of the initial examination

4. Determination of when the expertise and decision-making capabilities of the PT requires the PT to personally render services and when it is appropriate to utilize a PTA

5. Revision of the plan of care if indicated

6. Conclusion of a patient’s episode of care

7. Responsibility for communication related to a “hand off”

8. Oversight of all documentation for services rendered

The APTA has stated that it is the responsibility of the PT to perform the examination, evaluation, diagnosis, prognosis, intervention, and outcomes. The entire evaluation, the creation of the patient’s diagnosis and prognosis as well as components of the examination, intervention, and outcomes must be exclusively performed by the PT because of the need for continuous assessment and synthesis of information. Additionally, the APTA has identified selected interventions that are performed solely by the PT, which include “spinal and peripheral joint mobilization/manipulation and dry needling, which are components of manual therapy; and sharp selective debridement, which is a component of wound management” (APTA, 2018b). Any intervention that requires immediate and continuous examination and evaluation is to be performed by the PT (APTA, 2018b).

As stated earlier, PTAs may be utilized in administering interventions and in the collection of certain examination and outcomes. Before directing the PTA to perform specific components of the intervention, the PT must critically evaluate the patient’s condition (stability, acuity, criticality, and complexity), he or she must also consider the practice setting in which the intervention is to be delivered, the type of intervention to be provided, and the predictability of the patient’s probable outcome to the intervention (APTA, 2018a). The guidelines proposed follow those suggested by Dr. Watts ( Watts, 1971).

In addition, the knowledge base of the PTA, his or her level of experience, training, and skill level must be considered when determining which tasks can be directed to the PTA. The APTA has developed two algorithms (PTA direction and PTA supervision; Figs. 1.7 and 1.8) to assist PTs with the steps that should be considered when a PT decides to direct certain aspects of a patient’s care to a PTA and the subsequent supervision that must occur. Even though these algorithms exist, it is important to remember that communication between the PT and PTA must be ongoing to ensure the best possible outcomes for the patient. PTAs are also advised to become familiar with the Problem-Solving Algorithm Utilized by PTAs in Patient/Client Intervention (Fig. 1.9) as a guide for the clinical problem-solving skills a PTA should employ before and dur ing patient interventions (APTA, 2007).

PTs and PTAs are advised to refer to APTA policy documents, their state practice acts, and the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education guidelines for the most up-to-date information regarding interventions that are considered outside the scope of practice for the PTA. Practitioners are also encouraged to review individual state practice acts and payer requirements for supervision requirements as they relate to the PT/PTA relationship (Crosier, 2011).

State practice acts often describe the scope of practice and supervision requirements for PTAs. It is also important to note that levels of supervision are also described by the APTA. The APTA identifies three levels of supervision including: general supervision in which the PT is not required to be onsite but is available by telecommunications; direct supervision in which the PT is “physically present and immediately available for direction and supervision and has direct contact with the patient during each visit”; and direct personal supervision in which the PT or PTA is “immediately available to direct and supervise tasks that are related to patient management. The direction and supervision is continuous and telecommunications does not meet the requirement of direct personal supervision” (APTA, 2012). It is important to note that various policy documents define and mandate different levels of supervision (Crosier, 2010).

Unfortunately, in our current health care climate, there are times when the decision as to whether a patient should be treated by a PTA is determined by productivity concerns and the patient’s payer source and not the patient’s rehabilitation needs. An issue affecting some clinics and PTAs is the denial of payment by some insurance providers for services provided by a PTA. Consequently, decisions regarding the utilization of PTAs are sometimes determined by financial remuneration and not by the needs of the patient.

THE PHYSICAL THERAPIST ASSISTANT AS A MEMBER OF THE HEALTH CARE TEAM

The PTA functions as a member of the rehabilitation team in all treatment settings. Members of this team include the primary PT; the physician; speech, occupational, and recreation therapists; nursing personnel; the psychologist; case manager; and the social worker. However, the two most important members of this team are the patient and his or her family. In a rehabilitation setting, the PTA is expected to provide interventions to improve the patient’s functional independence and participation in life situations. Relearning motor activities, such as bed mobility, transfers, ambulation skills, stair climbing, and wheelchair negotiation, if appropriate, are emphasized to enhance the patient’s functional mobility. In addition, the PTA participates in patient and family education and is expected to provide input into the patient’s discharge plan. Patient and family instruction include providing information, education, and the actual training of patients, families, significant others, or caregivers, and is a part of every patient’s plan of care (APTA, 2014). As is the case in all team activities, open and honest communication and mutual respect among all team members is crucial to maximize the patient’s participation and achievement of an optimal functional outcome.

Although PTAs work with adults who have had strokes, spinal cord injuries, and traumatic brain injuries, some PTs have viewed pediatrics as a specialty area of practice. This narrow perspective is held even though PTAs work with children in hospitals, outpatient clinics, schools, and community settings, including fitness centers and sports-training facilities.

PTA Direction Algorithm (See Controlling Assumptions)

Physical therapist (PT) completes physical therapy patient/client examination and evaluation, establishing the physical therapy diagnosis, prognosis, and plan of care.

Are there interventions within the plan of care that are within the scope of work of a PTA?

PT provides patient/client intervention for interventions that are not within the scope of work of the PTA, including all interventions requiring ongoing evaluation.

Is the patient/client’s condition sufficiently stable to direct the intervention to a PTA? Yes

Are the intervention outcomes sufficiently predictable to direct the intervention to a PTA? Yes

Given the knowledge, skills, and abilities of the PTA, is the intervention within the personal scope of work of the individual PTA?

Yes

Given the practice setting, have all associated risks and liabilities been identified and managed?

Yes

Given the practice setting, have all associated payer requirements related to physical therapy services provided by a PTA been managed?

Yes

Direct intervention to the PTA while:

PT provides patient/client intervention and determines when/if the patient/client health conditions have stabilized sufficiently to direct selected interventions to a PTA.

PT provides patient/client intervention and determines when/if the prognostic conditions have changed sufficiently to direct selected interventions to a PTA.

PT provides patient/client intervention; assesses the limits of the PTA’s personal scope of work, identifies areas for PTA development, and assists the PTA in obtaining relevant development opportunities.

PT provides patient/client intervention and identifies solutions for unmanaged risk and liabilities.

PT provides patient/client intervention when payer requirements do not permit skilled physical therapy services to be provided by a PTA.

• Maintaining responsibility and control of patient/client management;

• Providing direction and supervision of the PTA in accordance with applicable laws and regulations; and

• Conducting periodic reassessment/reevaluation of the patient as directed by the facility, federal and state regulations, and payers.

Fig. 1.7 Physical therapist assistant (PTA) direction algorithm. (Adapted from [http://www.apta.org], with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association. © 2019 American Physical Therapy Association. All rights reserved.)

Complete physical therapy examination, evaluation, and plan of care, including determination of selected interventions that may be directed to the PTA.

Establish patient/client condition safety parameters that must be met prior to initiating and during intervention(s) (e.g., resting heart rate, max pain level).

PTA Supervision Algorithm

(See Controlling Assumptions)

Review results of physical therapy examination/ evaluation, plan of care (POC), and safety parameters with the PTA.

Are there questions or items to be clarified about the selected interventions or safety parameters?

Follow up with patient/client including reexamination if appropriate.

PTA initiates selected intervention(s) directed by the PT.

Monitor patient/client safety and comfort, progression with the selected intervention, and progression within the plan of care through discussions with PTA, documentation review, and regular patient/client interviews.

Provide needed information and/or direction to the PTA.

PTA collects data on patient/client condition relative to established safety parameters. Yes

Have the established patient/client condition safety parameters been met?

Is patient/client safe and comfortable with selected intervention(s) provided by the PTA?

Continue to monitor and communicate regularly with the PTA.

Has the PTA tried permissible modifications to the selected intervention(s) to ensure patient/client safety/comfort?

Reevaluate patient/client and proceed as indicated.

Provide needed information and/or direction to the PTA.

Do the data collected by the PTA indicate that there is progress toward the patient/client goals?

Has the PTA progressed the patient/client within the selected intervention as permitted by the plan of care?

Has the PTA tried permissible modifications to the selected intervention(s) to improve patient/client response?

Do the data collected by the PTA indicate that the patient/client goals may be met?

Reevaluate patient/client and proceed as indicated.

Continue to monitor and communicate regularly with the PTA or reevaluate patient/client.

Continue to monitor and communicate regularly with the PTA.

Reevaluate patient/client and proceed as indicated.

Provide needed information and/or direction to the PTA.

Fig. 1.8 Physical therapist assistant (PTA) supervision algorithm. (Adapted from [http://www.apta.org], with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association. © 2019 American Physical Therapy Association. All rights reserved.)

Communicate with PT and follow as directed

Utilized by PTAs in Patient/Client Intervention (See Controlling Assumptions on previous page.)

Problem-Solving Algorithm

Does the data comparison indicate that the safety parameters established by the PT about the patient's/client's condition have been met?

Communicate with PT for clarification

Compare results with previously collected data and safety parameters established by the PT

Collect data on patient/client current condition (e.g., chart review, vitals, pain, and observation)

Initiate selected intervention(s) as directed by the PT

Communicate results of patient/client intervention(s) and data collection, including required documentation

Does the data comparison indicate that the expectations established by the PT about the patient's/client's response to the interventions have been met?

Compare results with previously collected data

Collect relevant data

Yes

Are there questions or items to be clarified about the selected interventions?

Is patient/client safe and comfortable with selected intervention(s)?

Does the data comparison indicate that there is progress toward the expectations established by the PT about the patient's/client's response to the interventions?

No/Uncertain

Communicate with PT and follow as directed

Communicate with PT and follow as directed

Can modifications be made to the selected intervention(s) to improve patient's/client's response?

Interrupt/stop intervention(s)

Continue selected intervention(s)

Make permissible modifications to intervention(s)

Fig. 1.9 Problem-solving algorithm utilized by physical therapist assistants (PTAs) in patient/client intervention. (Adapted from [ http://www .apta.org ], with permission of the American Physical Therapy Association. © 2019 American Ph ysical Therapy Association. All rights reserved.)

Read physical therapy examination/ evaluation and plan of care (POC) and review with the physical therapist

Stop/interrupt intervention(s)

Can modifications be made to the selected intervention(s) to ensure patient/client safety/comfort?

Communicate with PT and follow as directed

Although some areas of pediatric physical therapy are specialized, many areas are well within the scope of practice of the generalist PT and PTA. The Academy of Pediatric Physical Therapy in their fact sheet state that “Physical therapist assistants may be involved with the delivery of physical therapy services under the direction and supervision of a licensed PT” (APPT, 2019). Additionally, the Academy states that “Physical therapists and physical therapist assistants must be graduates of accredited educational programs and comply with rules of state licensure and practice guidelines” (APPT, 2019). Practitioners may secure additional knowledge, certification, and credentials to recognize specialization in pediatrics (APPT, 2019).

The provision of pediatric services in school systems by PTAs is supported, however, because of supervision requirements it may be difficult for school systems to meet the PT/ PTA supervision requirements. This can be especially problematic in rural areas where the number of providers may be limited. When it is possible to comply with supervision standards, many school settings find that the “PT/PTA service delivery model is an effective and efficient way to provide services for students, consistent with the need for cost containment” (APTA, 2014).

The rehabilitation team working with a child with a neurologic deficit usually consists of the child; his or her parents; the various physicians involved in the child’s management, and other health care professionals, such as an audiologist and physical and occupational therapists; a speech language pathologist; and the child’s classroom teacher. The PTA is expected to bring certain skills to the team and to the child, including knowledge of positioning, posture and lifting, use of adaptive equipment and assistive technology, management of abnormal muscle tone, knowledge of developmental activities that foster acquisition of functional motor skills and movement transitions, knowledge of family-centered care, and the role of physical

CHAPTER SUMMARY

Changes in physical therapy practice have led to an increase in the number of PTAs, and greater variety in the types of patients treated by these clinicians. PTAs are actively involved in the treatment of adults and children with neurologic deficits. After a thorough examination and evaluation of the patient’s status, the primary PT may determine that the patient’s intervention

REVIEW QUESTIONS

1. Discuss the ICF model as it relates to health and function.

2. List the factors that affect an individual’s performance of functional activities.

3. Discuss the elements of patient/client management.

therapy in an educational environment. Additionally, interpersonal communication and advocacy skills are beneficial as the PTA works with the child and the family, as well as others. Family teaching and instruction are expected within a family-centered approach to the delivery of various interventions embedded into the child’s daily routine. Because the PTA may be providing services to the child in his or her home or school, the assistant may be the first to observe additional problems or be told of a parent’s concern. These observations or concerns should be communicated immediately to the supervising PT. Because of the complexity of patients’ problems and the interpersonal skill set needed to work with the pediatric population and their families, most clinics require prior work experience or residency training prior to employing a PT, or prior work experience or advanced proficiency for PTAs who wish to work in these practice settings ( Clynch, 2012).

PTs and PTAs are valuable members of a patient’s health care team. To optimize the relationship between the two and to maximize patient outcomes, each practitioner must understand the educational preparation and experiential background of the other. The preferred relationship between PTs and PTAs is one characterized by trust, understanding, mutual respect, effective communication, and an appreciation for individual similarities and differences (Clynch, 2012). This relationship involves direction, including determination of the tasks that can be directed to the PTA, supervision because the PT is responsible for supervising the assistant to whom tasks or interventions have been directed and accepted, communication, and the demonstration of ethical and legal behaviors. Positive benefits that can be derived from this preferred relationship include more clearly defined identities for both PTs and PTAs and a more unified, collaborative approach to the delivery of high-quality, cost-effective, patient-centered, physical therapy services.

or a portion of the intervention may be safely performed by an assistant. The PTA functions as a member of the patient’s rehabilitation team, and works with the patient to maximize his or her ability to participate in meaningful activities. Improved function in the home, school, or community remains the primary goal of our physical therapy interventions.

4. Identify the factors that the PT must consider before utilizing a PTA.

5. Discuss the roles of the PTA when working with adults or children with neurologic deficits.

REFERENCES

Academy of Pediatric Physical Therapy, American Physical Therapy Association: Academy of pediatric physical therapy fact sheet, the ABCs of pediatric physical therapy, Alexandria, VA, 2019, APTA. Available at: https://pediatricapta.org/includes/fact-sheets/ pdfs/09 abcs of ped pt.pdf?v=1.1. Accessed May 4, 2019.

American Physical Therapy Association: Guide to physical therapist practice 3.0, Alexandria, VA, 2014, APTA. Available at: guidetoptpractice.apta.org. Accessed May 4, 2019.

American Physical Therapy Association: Direction and supervision of the physical therapist assistant HOD P06-18-28- 35, Alexandria, VA, 2018a, APTA. Available at: www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/ APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/Practice/DirectionSupervisionPTA. pdf. Accessed January 4, 2019.

American Physical Therapy Association: Guide to physical therapist practice, ed 2, Alexandria, VA, 2003, APTA, pp 13–47, 679.

American Physical Therapy Association: Interventions performed exclusively by physical therapists HOD P06-18-31-36, Alexandria, VA, 2018b, APTA. Available at: www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/ APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/Practice/ProceduralInterventions. pdf. Accessed May 4, 2019.

American Physical Therapy Association: Levels of supervision HOD P06-00-15-26, Alexandria, VA, 2012, APTA, Available at: www.apta. org/uploadedFiles/APTA/org/About_US/Policies/Terminology/ Levels of Supervision.pdf. Accessed March 13, 2019.

American Physical Therapy Association Education Division: A normative model of physical therapist professional education, version 2007, Alexandria, VA, 2007, APTA, pp 84–85.

Cech D, Martin S: Functional movement development across the life span, ed 3, Philadelphia, 2012, Saunders, pp 1–13.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Disability and health overview, impairments, activity limitation and participation restrictions, Atlanta, GA, 2017, CDC. Available at: www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/ disabilityandhealth/disability.html. Accessed May 1, 2019.

Clynch HM: The role of the physical therapist assistant: regulations and responsibilities, Philadelphia, 2012, FA Davis, pp 23, 43–76.

Crosier J: PTA direction and supervision algorithms, PTinMotion 2010. Available at: www.apta.org/PTinMotion/2010/9/PTA supervisionalgorithmchart. Accessed January 7, 2014.

Crosier J: The PT/PTA relationship: 4 things to know , February 2011. Available at: www.apta.org/PTA/PatientCare/ PTPTARelationship4Thingst oKnow. Accessed May 4, 2019.

Nagi SZ: Disability concepts revisited: implications for prevention. In Pope AM, Tarlox AR, editors: Disability in America: toward a national agenda for prevention, Washington, DC, 1991, National Academy Press, pp 309–327.

Section on Pediatrics American Physical Therapy Association: School-based physical therapy: conflicts between Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) and legal requirements of state practice acts and regulations, Alexandria, VA, 2014, APTA. Available at: www.pediatricapta.org/includes/Fact-sheets?pdfs. Accessed May 4, 2019.

Verbrugge LM, Jette AM: The disablement process, Soc Sci Med 38:1–14, 1994.

Watts NT: Task analysis and division of responsibility in physical therapy, Phys Ther 51:23–35, 1971.

World Health Organization: How to use the ICF: a practical manual for using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF), Geneva, Switzerland, 2013, WHO.

World Health Organization: International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health: children and youth version, Geneva, Switzerland, 2007, WHO.

World Health Organization: International Classification of Functioning, Disability, and Health (ICF), World Health Organization. Available at: www.who.int/classifications/icf/en/. Accessed January 5, 2014.

World Health Organization: Towards a common language for functioning, disability and health, ICF, Geneva, Switzerland, 2002, WHO.

Keywords: International classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Direction and Supervision, Roles and function of PT and PTAs