https://ebookmass.com/product/neuroethics-and-bioethics-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Psychiatric Neuroethics: Studies in Research and Practice

Walter Glannon

https://ebookmass.com/product/psychiatric-neuroethics-studies-inresearch-and-practice-walter-glannon/

ebookmass.com

Decoding Consciousness and Bioethics 1st Edition Alberto García Gómez

https://ebookmass.com/product/decoding-consciousness-andbioethics-1st-edition-alberto-garcia-gomez/

ebookmass.com

The Methods of Bioethics: An Essay in Meta-Bioethics John Mcmillan

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-methods-of-bioethics-an-essay-inmeta-bioethics-john-mcmillan/

ebookmass.com

(eBook PDF) Fundamentals of Human Resource Management 8th Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/ebook-pdf-fundamentals-of-humanresource-management-8th-edition/

ebookmass.com

The Toyota Engagement Equation: How to Understand and Implement Continuous Improvement Thinking in Any Organization Richardson

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-toyota-engagement-equation-how-tounderstand-and-implement-continuous-improvement-thinking-in-anyorganization-richardson/ ebookmass.com

Rural Communities: Legacy + Change 5th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/rural-communities-legacy-change-5thedition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Electric Circuits, 12e 12th Edition James Nilsson

https://ebookmass.com/product/electric-circuits-12e-12th-editionjames-nilsson/

ebookmass.com

Traditions & Encounters Volume 1 From the Beginning to 1500 6th Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/traditions-encounters-volume-1-from-thebeginning-to-1500-6th-edition/

ebookmass.com

McGraw-Hill Education SAT, 2020 edition Christopher Black

https://ebookmass.com/product/mcgraw-hill-education-sat-2020-editionchristopher-black/

ebookmass.com

Stephen Orgel

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-idea-of-the-book-and-the-creationof-literature-stephen-orgel/

ebookmass.com

SerialEditor

JudyIlles,CM,PHD

DistinguishedUniversityScholarandUBCDistinguished ScholarinNeuroethics

DivisionofNeurology,DepartmentofMedicine NeuroethicsCanada

TheUniversityofBritishColumbia 2211WesbrookMall,KoernerS124 VancouverBCV6T2B5

Canada

KatherineBassil,EditorialAssistanttoJudyIlles

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier

50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 125LondonWall,London,EC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom

Firstedition2022

Copyright©2022ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic ormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem, withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,further informationaboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuch astheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

Thisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythe Publisher (other than asmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperience broadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedical treatmentmaybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluating andusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuch informationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,including partiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assume anyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability, negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideas containedinthematerialherein.

ISBN:978-0-12-824562-0 ISSN:2589-2959

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: Zoe Kruze

AcquisitionsEditor: Sam Mahfoudh

DevelopmentalEditor: CindyAngelitaGardose

ProductionProjectManager: SudharshiniRenganathan CoverDesigner: VictoriaPearson

TypesetbySTRAIVE,India

Contributors

ClareBond

SarahWigglesworthArchitects,London,UnitedKingdom

SoniaBoue

ArtistandConsultantforNeurodiversityintheArts,Oxford,UnitedKingdom

JosBoys

LearningEnvironmentsEqualityDiversityandInclusionCentre(LEEDIC),TheBartlett FacultyoftheBuiltEnvironment,UniversityCollegeLondon;TheDisOrdinary ArchitectureProject,London,UnitedKingdom

AnthonyClarke

BLOXAS,Melbourne,VIC,Australia

J.T.EisenhauerRichardson

DepartmentofArtsAdministration,Education,andPolicy,TheOhioStateUniversity, Columbus,OH,UnitedStates

JohnGardner

SchoolofSocialSciences,MonashUniversity,Clayton,VIC,Australia

MarieK.Harder

Values&SustainabilityResearchGroup,UniversityofBrighton,Brighton,UnitedKingdom

CamilleY.Huang

NeuroethicsCanada,DivisionofNeurology,DepartmentofMedicine,UniversityofBritish Columbia,Vancouver,BC,Canada

JudyIlles

NeuroethicsCanada,DivisionofNeurology,DepartmentofMedicine,UniversityofBritish Columbia,Vancouver,BC,Canada

AllenKong

AllenKongArchitectPtyLTD,NorthMelbourne,VIC,Australia

YeoryiaManolopoulou

TheBartlettUniversityCollege,London,UnitedKingdom

MollyMattaini

InterdisciplinaryTheaterStudies,UniversityofWisconsin–Madison,Madison,WI, UnitedStates

RaquelMeseguerZafe

Founder,UncharteredCollectiveandPMStudioResident,ArnolfiniGalleryBristol2021–2022,NarrowQuay,Bristol,England

TanyaPetrovich

DementiaAustralia,Parkville,VIC,Australia

WilliamRenel

TourettesheroCIC,London,UnitedKingdom

JimSinclair

AutismNetworkInternational(ANI),Syracuse,NY,UnitedStates

JessicaThom

TourettesheroCIC,London,UnitedKingdom

NatashaM.Trotman

TheWellcomeCollectionHub,TheWellcomeTrust;TheHelenHamlynCentrefor Design,RoyalCollegeofArt;KensingtonGore,SouthKensington,London, UnitedKingdom

SarahWigglesworth

SarahWigglesworthArchitects,London,UnitedKingdom

Foreword

TheIndusRiverValley,whichliesneartheborderofthemodernstatesof IndiaandPakistan,wasthesiteofoneoftheearliesthumancivilizationson theplanet.Coursedbysnow-andmonsoon-fedrivers,thisrichalluvialplain wasoriginallyhometoanagrariansociety,whichgrewtobecomealarge andtechnicallyadvancedbronze-ageurbanculture—aculturethathelped definethesubsequentgrowthoftheIndiansubcontinent.Atitsancient peak,theIndusValleycivilizationdevelopedmodernformsofgovernance, manufacturing,andtradeandexcelledinbothfineandpracticalarts. Buildingdesignandconstruction,andurbanplanning,wereamongthe strengthsofthissociety,andthepracticalandphilosophicalaspectsofthese disciplineswerecapturedinearlyHinduVedasas“VaastuShastra,”the scienceofarchitecture.

Vaastuisacomplexsetofrulesandformalismsforbuildingdesign,much ofwhichhasoriginsinreligiousandmysticalbeliefs,butoneofitsguiding principlesisthat“forms,space,proportion,energypointsandaesthetic features,canbeputtogetherinsuchawaythattheentireexperiencecreated bythebuildingwouldbringaboutanextraordinaryresponseinthe occupants”(Ananth,1999).“Response”herereferstomentalstates— perceptual or cognitive—thatinfluencedecisions,beliefs,emotions,and actions.Perhaps,mostimportantly,thisearlyHinduapproachwasearnestly egalitarian,foundedontheprinciplethateachindividualhasuniquespiritual andmaterialconnectionstotheuniverse.Itnaturallyfollowedthatabuildingcanonlyfunction,canonlyachievean“enhancementandenrichmentof theusers’consciousness,”iftheuniqueelementsoftheuserareunderstood andincorporatedindesign(Ananth,1999).Thesimplebutfundamental principle here isthatthebuildingmustbedesignedforthepersonwho occupiesit,withrecognitionthateveryindividualhasspecific—andequally valid—requirementsforfulfillmentthroughthespacestheyinhabit.

InmodernculturesoftheindustrializedWest,thisperson-centricdesign ethicisallbutlost.Architectswhoattendtotheindividualandtheirrelationshiptothesite,tothecommunity,andtothenaturalenvironmentmust chargeheftyfeesfordoingso.Thishasbecomeanelitistpracticesuchthat fewerthan2%ofresidentialhousinginAmericaisnowdesignedbyarchitects(Dickinson,2016).Outsideoftheupscaleresidencesofthewealthyand sometimes architecturally sophisticated,homedesign,today,islargely

drivenbyprofitandexpediencemotivesofrealestatedevelopers.Withina fewmilesofmyownhomeinSouthernCalifornialiesablightoftract houses,boundedbythefreewayandextendingasfareastastheeyecan see.Overafewshortdecades,largeswathsofsomeofthemostbeautiful landontheplanetwassoldtodevelopers,wholeveledthenaturalwarp andwoofoftheearthandbuilthousesofmind-numbingsameness.Allof thispracticedeniesanyneedforrealdesignorcreativityandgreatlyreduces thecostofconstruction.Contrarytothearchitecturalprinciplesthatguided thebuiltenvironmentofmillenniapast,theresultisthatourbuildingstoday dictatewhotheoccupantmustbe,ratherthanthepersonasthesourceof inspirationforthebuilding.

Theeditorsandcontributorstothisnewvolumehave,quiterightlyand usefully,castarchitectureasanethicalchallenge.Whenasystemofpractice discountsthemanifolddiversityofthehumanpopulation,forcingallindividualstoconformtothesameideal,dueprocessfailsanddisparitiesof opportunities,access,andtreatmentareinevitable.Architectsandobservers ofsocialhistoryalikepointtothepatentandprofoundinfluenceofthebuilt environmentonhumanbehaviorandcognitivefunction.Butweshyaway fromfrankscientificdiscussionsofthepsychologicaldeprivationcausedby thesamenessofplannedresidentialcommunities,thebanalityofour public-schoolclassrooms,thesensoryandmotorinequitiesthatresultwhen profitdrivesthebuiltenvironment,andthefactthatdesignforpeoplewith geneticoracquireddisordersofthebrainisatriskofhavingthesamestatusas anorphandrug.

Theauthorsofthechaptersinthiscollectionbringtheseissuesoutinto theopenand,indoingso,contributetoanongoingdiscussionofindividual differencesandfairnessinthelightoffast-growingknowledgeofhowthe humanbraindevelopsandfunctionsandhowitgivesrisetotheuniqueness ofindividualhumancharacterandability.Thechaptersinthiscollection defineneuroethicsandframeitsrelationshiptothebuiltenvironment (andindeedspacemoregenerally)andtomodernneuroscienceresearch. Perhaps,themosteffectivewaytocommunicatetheseconceptsandstrategiesisinthecontextofspecificcases,includinghowthedesignneedsof individualswhothinkdifferentlyfromoneanotherorwhosufferfrom neurologicalandcognitiveimpairmentsareslowlybutsteadilybeing addressed.Severalchaptersinthiscollectionadoptthisapproachwithfocus, forexample,ondementiaandautism.Advocacyandinterventionare naturallycriticalelementsofapathforwardandareappropriately highlightedinthiscollection.Finally,andverycompellingly,thecollection

includescontributionsbyindividualswho,byvirtueoftheirinabilitytofit insidethestandardbox,havesufferedatthehandsofasocietyinuredofits diversity.

Manywillcontinuetoaskwhypeoplearenotallcontentwiththesame threebaths,elevatedentryway,andshinyopen-plankitchen,withthe convenienceandpastelpeacethatitaffords.Theanswer,wellunderstood bytheancientHindusandre-articulatedherein,isthatpeoplearenotall thesame.Modernneuroscienceandcognitivesciencehaveprobedthe depthsofdifferenceandrevealedthatstructuralandfunctionalattributes ofthebrainareuniqueproductsofpersonallifeandexperiencesoftheenvironmentalandsocialcontextsinwhicheachindividuallearns,decides,and acts.Theculturaldiversityoftheseexperiences,expressedbyhumans throughassortedpersonalitieswithdistinctivetastes,colorfullyeccentric designpreferences,andvariedstrengthsandweaknesses,arewhatdefines theManushyalaya—the“humantemple”inVaastu,thelivingspacefor “discoveringandhoningtheindividualspirit”(Ananth,1999).

This person-centric andegalitarianapproachtothebuiltenvironment doesnotscaleeasilyinafreemarket,particularlyinthecontextoflarge disparitiesofwealthandpower.Buttressedbyacontinuouslygrowing knowledgeofbrainfunction,however,itisanapproachthatmightlead backtoanerainwhichthescienceofthehumanconditionactuallymatters toarchitecture.Cultivatingthatapproach,asthisvolumedoes,advancesa visionandapromiseofanewarchitectureforthehumangood.

THOMAS D.ALBRIGHT

TheSalkInstituteforBiologicalStudies LaJolla,CA,UnitedStates August2022

References

Ananth,S.(1999). ThePenguinguidetoVaastu:TheclassicalIndianscienceofarchitectureand design.India:PenguinBooks. Dickinson,D.(2016).Architectsdesignjust2%ofallhouses—Why?.CommonEdge7, 2016. https://commonedge.org/architects-design-just-2-of-all-houses-why/

Introduction

JohnGardnera,JosBoysb,andAnthonyClarkec

aSchoolofSocialSciences,MonashUniversity,Clayton,VIC,Australia

bLearningEnvironmentsEqualityDiversityandInclusionCentre(LEEDIC),TheBartlettFacultyoftheBuilt Environment,UniversityCollegeLondon;TheDisOrdinaryArchitectureProject,London,UnitedKingdom cBLOXAS,Melbourne,VIC,Australia

Architecture,asAmosRapoportfamouslyillustrated(1969),isaclear expressionof socialandculturalnorms.Thephysicalspacesofoureveryday lives—ourhomesandworkplaces,towns,cities,andtransportinfrastructures—reflectdeeply-heldassumptionsabouthumanbehaviorandinteraction.Domesticspacesareobviousexamples(Duncan&Lambert,2004; Gorman-Murray,2007; Percival&Hanson,2009).Mostnewlybuilthomes in western countriescontaintwoorthreebedrooms,reflectingthecultural intransigenceofthenuclearfamilystructure.Thedominanceofstepsand staircases(insteadoflevelaccessesandramps)assumesthatindividualsmove bipedally.Sotoodoestheconventionalwidthofdoorframesorthesizeof powderroomsandtoiletingspaces,bothofwhichtypicallyinhibittheuseof walkingaidsandwheelchairs.Thetrendtowardopen-plankitchenanddiningareasinmanycountriesreflectstheincreasingcentralityofthekitchen andfoodpreparationinsocialentertainmentand,nodoubt,theassumption thatmealpreparationandchild-mindingresponsibilitiesareundertakenby thesameindividualsimultaneously(Dowling&Power,2012).Somebehavioral norms haveofcoursebecomeencodedindomesticbuildingregulationsandguidelines(e.g.,theneedtoseparatetoiletingareasfromfood preparation),somearereinforcedbyeconomicdynamics(whocanafford ahousewiththreebedrooms,letalonefour?),andmanyaretheconsequenceofthehabitualprofessionalpracticesofdevelopers,architects, designers,andbuilders(e.g.,thenear-universalpreferenceforsmoothand hardandlargelyfeaturelessinternalwalls).

Architecture,however,isnotsimplytheexpressionofsocialandcultural norms.Itisaverypowerfulmeansbywhichsuchnormsareimposedand perpetuated.Indeed,theidealthatverymuchunderpinsarchitectureasa professionisthatbetterarchitecturewillmakegenuineimprovementsto peoples’lives,andis,then,apublicgood(Lautner,2011).Thereisalso now a well-knownandsubstantialbodyofevidencethatthearrangement

ofourphysicalspaces—suchasthesimpleproximityofwindowswith views—canmakemeasurableimprovementsinpeoples’healthandwellbeing(Rice,2019).Theassumptionthat“weshapeourbuildingsand thereafter they shapeus”(Churchill,1943)needstobetreatedwithcare. Whoexactly isthis“we?”Whoisbeingvaluedinthedesignofourbuilt surroundingsandwhoisbeingignored,marginalizedormis-represented? Whohaspoweroverwhatgetsfinancedandconstructedandmaintained? Whoisleftoutoftheseprocesses?Andhowexactlydoesarchitecturework inrelationtohowweoccupyit?Asthefeministarchitecturecollective Matrixwrotein 1984:

Buildingsdonotcontrolourlives.Theyreflectthedominantvaluesinoursociety, politicalandarchitecturalviews,people’sdemandsandtheconstraintsoffinance, butwecanliveinthemindifferentwaysfromthoseoriginallyintended.Buildings onlyaffectusinsomuchastheycontainideasabout[ ]our ‘properplace’,about whatisprivateandwhatispublicactivity,aboutwhichthingsshouldbekeptseparateandwhichputtogether(pp.9–10)

Whilematrixwasthinkingmainlyaboutgender,manyothershavecritiqued assumptionsaboutarchitectureanditsoccupation.Disabilityadvocatesand academicsfromvariousdisciplineshavelongdemonstratedthatthematerial fabricofourbuiltenvironmentisenablingforsomepeopleanddisablingand alienatingforothers,reifyingsocialdivisionsandstigma(Blunt&Dowling, 2006; Delitz,2017; Duncan,1996; Gleeson,1964; Heylighen,Van Doren, & Vermeersch,2013; Imrie,1996; Jackson,2018).Morerecently, disabilitystudies scholarsandactivistshaveextendedthesedebates,for example,bycriticallyexploringhistoriesofbuildingaccessandinclusive design(Hamraie,2017; Hendren,2020; Titchkosky,2003; Williamson, 2019)andbuildingdirectlyondisabledandneurodivergentpeople’sown diverse perspectives andexperiencesofbuiltspaceasincludedinacademic scholarship,autobiography,memoirandotherformsofnarrative(Gadsby, 2022; Limburg,2021; MainspringArts,2021; Wong,2020; Yergeau,2017). Architecture and thebuiltenvironment,therefore,are ethically relevant. Theyareethicallyrelevantbecausetheyenactageneralizedsetofnorms abouthowhumansshouldconductthemselves,andindoingso,theyconstrain,enable,andtransmutetheactionsofindividualsandcollectivesin waysthatsignificantlyimpacttheirwell-being.Architectureandthebuilt environmentarealso,asmanyscholarshaveargued,importanttargetsfor ethicallyrelevantinterventions(Fox,2012).Thesemightbepermanent adjustments and reconfigurationsofthebuiltenvironment,aimedatdirectly mitigatinginequalitiesand,ideally,ultimatelyenablingadiversityofpeoples toflourish(Watchorn,Larkin,Hitch,&Ang,2014).Or,theymightinclude

thecreationoftemporaryinstallations,aimedatpromptingagreater awarenessandreflexivityamongthosewhoengagewiththemaboutthe ethicalrelevanceofthebuiltenvironment(e.g., Boys,2014; Cachia, 2017).Ortheymightbeaimedatshiftingbotheverydayanddisciplinary practices that—whetherbecauseofunconsciousbiasordeliberate intention—reproduceparticularpatternsofinequalityinaccessto,and useof,spaceandresources.

Architectureasanethicalendeavor

Conceptualizingarchitectureasanethicalendeavorraisesanumberof importantquestions.Ingeneralterms,whatprocesseswillbringaboutspaces thatgenuinelysupporttheflourishingofadiversityofpeople?Morespecifically,wemightask:whataretherelationshipsbetweenhumanvariety,inall itsneuro-andbiologicalcomplexity,andthedesignandoccupationofbuilt spaces?Towhatextentshouldarchitectureengagewithrapidlyemerging neuroscientificknowledgeaboutthenatureofhumandifference?How mightlivedexperiencesandtheaccumulatedknowledgeofdiverseindividualsandgroupsbemeaningfullyincorporated?Andhowcanpeoplewho considerthemselvesunproblematicallynormalpayattentionto,andtake accountof,nonnormativeandneurodivergentothersthatgoesbeyond commonplacetropesofanassumedabnormalityorpathology?

Therecognitionandcelebrationofneurodiversityoverthepasttwo decades(see Kapp,2019)hasmadethesequestionsandtheissuesthatunderpin them especiallyrelevant.Ourhomesandworkplacesandbuiltoutdoor spacesarebasedoninnumerableassumptionsaboutthecognitivecapabilities andemotionalresponsesoftypicalhumans.Theymakedemandsonour memories,ourhabitsofreasoning,andourlevelsofenergy.Theyassume sharedsensitivitiestosomeelements(e.g.,airtemperature,theheightof doorhandles),andageneralinsensitivityorirrelevancetoothers(e.g., thefeelingofsteppingonthegroutlinesbetweentiles,thephysicalsensation ofbricksurfaces).Forthosewhoapproximatea“typicalhuman”intheir cognitivecapacitiesandemotionalresponses,theexperienceofinhabiting everydaybuiltenvironmentswillbemostlyunremarkable,asidefromvariouslevelsofcomfortanddiscomfort.Forothers,however,suchenvironmentscanbedeeplyperplexing,alienating,andindeedtraumatic.These atypicalengagementsmaybeaconnectedtolearningdisabilities,chronic illness,cognitivedecline,resultfrominjury,oldageorneurodegenerative disease.Theyarealsoindicativeofconditionsthathaveacquiredadiagnostic labelsuchasautismspectrumdisorder,posttraumaticstressdisorder,

Tourettessyndromeorsimilar,someofwhicharenowrecognizedandoften celebratedasevidenceofnormalhumanneurodiversityinourmanyforms ofresponsivenessandsensitivitiestooursurroundings.Thesemodesofexistenceandexperienceforegroundwhatwecancallthe neuroethical relevance ofarchitecture.Thisreferstotheconventionalcapacityofthebuiltenvironmenttoperpetuateandenableneurotypical(NT)modesofexistenceand expression,andtodisableneurodivergentandbio-divergentpeople;butalso duetoits potential asameansofsupportingandenablingother, neurodivergentmodesofexistenceandexpression.

Sowhatmightanarchitecturethatalsotakesintoaccount neurodivergentmodesofexistenceandexpressionactuallybelike?How wouldthedesignofourbuildingsandinfrastructureneedtochange? Whatprocesses,collaborations,tools,andsensitivitiesmightmeaningfully engageneurodivergentpeopleandtheiralliesinthedesignandevolution ofbuiltenvironments?Whatistherelevanceofneuroscienceandemerging knowledgeofneuralandcognitivemechanisms?Andtowhatextentdo educatorsandprofessionals—boththoseinvolvedinneuroscienceandthose acrossthebuiltenvironmentsector—needtocriticallyrethinktheir practicesandattitudes?Whatrolecandisabilityartandtheaterplayinboth generatingawarenessamongpractitionersandcommunitiesabouttherelationshipsbetweenarchitectureandneurodivergence;andinopening-up creativeandprovocativespacesthatsuggestthepotentialofbuiltspaceto supportallitsdiverseoccupants?

Framingneurodivergence

Thepurposeofthiseditedcollection—thefifthinthe Developmentsin NeuroethicsandBioethics series—istoaddressthesequestions.Ouraimshere aretodemonstratethenecessityforcriticalengagementwitharchitecture andarchitecturalprocessesaswerecognizeandcelebrateneurodivergent modesofexistenceandexpression,andtoillustratewhathasandisbeing doneinthisregard,byacademicscholars,practitioners,andimportantly, byneurodivergentpeoplethemselves.Wehavethereforebroughttogether articlesthatrangeacrossacademicdisciplinesincludingneuroethics,sociology,architecturaltheoryanddisabilitystudies;thatcenterneurodivergent people’sownknowledgeandexperiencesofbuiltspaceanditsassociated designpracticesandprocesses;andthatincludecontributionsfromarchitects anddesignersworkingwithneurodivergentclientsandusersinavarietyof ways.Oneconsequenceofthisisthatthisvolumeisquitedifferentinits formandformatcomparedtoothersintheseries,andindeedconventional

collaborativeacademictextsmoregenerally.Somecontributionsareindeed conventionalintheiracademicstyleandtone.Others,however,employ manyimages;someuseamorecasualandwidely-accessibletoneandstyle; somearedeliberatelywrittenoutsideofacademicnorms;andsomecontributionsaresignificantlyshorterthanconventionalacademictexts.Wehave moretosayabouttheimportanceofthispluralisticapproachbelow.

Itisalsoimportanttomentionherethatmanycontributionsinthisvolume arewrittenbyautisticpeople,and/orareaboutautisticperceptionsand experiences.“Neurodiversity”and“neurodivergence”are—aswediscuss inmoredepthbelow—evolvingconcepts.Inaddition,neurodivergenceis oftencurrentlyusedintheliteratureasasynonymforautism.Itisnotour placeheretodelineatewhatexactlyconstitutesneurodivergence,andwe wanttoremainopentotheprospectthatitcanbeappliedtomanydifferent modesofexistenceandexpression,includingbutnotrestrictedtolearning disabilities,ADHD,dyslexia,trauma,braininjuryordegenerationandthe like.Thefactthatmorechaptersfocusonautisminthisvolumethanother modesofneurodivergenceisareflectionofthepioneeringworkthathasbeen undertakenbyautisticscholarsandtheiradvocates,which,webelieve, illustratesthemesandconcernswhicharerelevanttoneurodivergenceand architecturemoregenerally.Atthesametime,wewanttoresistatendency totryanddelineateafixedandfinallistof“neurodivergent”categories.We aremoreinterestedinexploringboththesimilaritiesanddifferencesinthe manyneurodivergentwaysofbeingintersectwithbuiltspaces.

Exploringcomplexintersectionsasthisvolumedoesmakescertain demands.Itdemandsaclarityaboutconceptsandmethods,sothesecan besharedeffectivelyacrossmultipledisciplinaryperspectivesandagendas, anditdemandsacriticalityaboutconventionalacademicwritingitself,to ensurethatnonnormativevoicesarenotexcluded.Whileourintended readersspanacrosspeopleworkinginneuroscience,thoseworkinginbuilt environmentareas,andneurodivergentscholars,artistsandothersinterested inarchitecture,thebuildenvironmentandneurodivergentspacemore generally;weareparticularlykeentomakesurethatvariousneurodivergent voicesandperspectivesarerepresented.Inthisspace,itisessentialthatwe recognizeandvaluebothalternativenonnormativeformsofacademic writing,andthecentralityofvisualization,illustrationsandotherformsof representationswithinarchitectureandotherbuiltenvironmentdisciplines.

Thisalsorequiresthatwefirstlookattheterminologyofneurodiversity, neurodivergenceandneurotypicality,anditsassociatedeverydaypractices. Thisisanareaofactivism,advocacy,andscholarshipwherethesocio-ethical implicationsoflanguage,terms,andconceptshavebeenwidelydiscussed.

Hereweprovidesomegeneraldefinitionsforthekeyconceptsandterms thatareusedbyauthorsinthisvolume.Indoingthis,wealsowanttoillustrate“whatisatstake”inourchoiceoftermsandphrases.Likethearchitectureofourbuiltenvironments,thelanguageweusetomakesenseofeach otherisanassertionofparticularconventionsandnorms,andthiscanhave stigmatizingandrepressiveconsequences.Werecognizetheneedfora sharedunderstandingofkeyconceptsandterms—hencetheprovisional definitionsweprovidehere—butwealsorecognizethenecessitythatsuch conceptsandtermsevolveviacontestationandnegotiation.

Readerswillnotethatwehavechosenforthetitleofthisbook NeurodivergenceandArchitecture,ratherthan NeurodiversityandArchitecture. Here,wehavemadeuseoftheincreasinglycommondistinctionbetween neurodivergenceandneurodiverse:theformerreferstomodesofbeingthat divergefrom thenorm,andarethus distinctfrom so-calledNTmodesofbeing, whereasthelatterreferstothefullspectrum,includingmodesofbeing conventionallydeemednormalortypical.Ourdecisionherereflectsour focusonarchitecturalandothercreativeprocessesthatengagewithatypical participants.Afocusonneurodiversity,incontrast,wouldimplytheinclusionofarchitecturalresponsesandprocessesthatengagealsowithNT people,whobydefinitionrepresentthelargestanddominantsegmentof neurodiversespectrum.SuchafocuswouldofcoursebearedundantexercisegiventheeverydayunnoticedprivilegingofNTpeopleinarchitectural processesandaccompanyingscholarship,anditwouldundermineour objectivetochampionarchitecturesandprocessesthatcelebratemodesof existenceandexpression.

Whatexactly,then,mightbeincludedwithintheterm “neurodivergent?”Asnotedabove,wedonotmakeafirmdistinctionabout whatmodesofbeingare—orshouldbe—includedwithintheterm.Itisnot ourplacetomakesuchadelineation,anditislikelythattheapplicationof thetermwillevolve.Ingeneralterms,however,weassumethatthetermcan applytoarangeofatypicalmodesofexistenceandexpression.Thisofcourse includesatypicalmodesthatarenowrecognizedandcelebratedbyan increasingnumberofscholarsandadvocatesasnormalbutatypical,such asautismorADHD.

Thisisinformedbyalonghistoryofchallengestothemedicalmodelof disability,thatis,onethatseesimpairmentsasindividualproblems,predominantlyarticulatedwithinamedicalframeworkasdiagnosableconditions characterizedbyabnormalbrainfunctioningandadysfunctionalengagementwiththeworld,andthatthereforerequiremedicaltreatment and—preferably—cure.Commonterminologythatisoftenusedtomake

senseofautism,suchas“high-”and“low-functioning”reflectsthismedical framework,andhasbeenconsistentlyresistedbymanyautisticactivistsand scholars(seeHarder,thisvolume).Thepremiseofthisbookisthatsuch modesmayindeedbeenactedandexperiencedasdysfunctional,butthatthis istheproductofengagementwithinadequatebuiltenvironments(aswellas otherstigmatizingandrepressivesocialandculturalfactors).Fromthis perspective,disabilityneedstobeunderstoodthroughasocialmodelthat examinestheinterplaybetweendiscriminatorysocietalattitudes,social andmaterialbarriers,andimpairment.

Thisinturn,hasbroadenedourengagementswithneuroethics,asshown bytherangeofselectedcontributionstothisvolume.Ifneuroethicswithin neurosciencefocusesontheongoingimprovementsinourabilitytomonitorandinfluencebrainfunction,requiring“theexaminationofwhatisright andwrong,goodandbad,aboutthetreatmentof,perfectionof,or unwelcomeinvasionofandworrisomemanipulationof,thehumanbrain” (Marcus,2002:p.5),thenaneuroethicsthatalsoengageswiththesocial model and withourbuiltsurroundings,necessarilyopensuptheneedfor conceptualframeworksthatconnecthowourbrainsgiverisetothepeople thatweareandthesocialandspatialstructuresthatweinhabitandcreate.In differentways,fromthepersonalthroughtothetheoretical,manyofour authorsareconcernedtoconnectneuroethicstohumanrightsaroundaccess andinclusion;toequalityandequity;andtosocialspatialandmaterial justice—oftencalleddisabilityjustice(Costanza-Chock,2020; Mingus, 2011; Piepzna-Samarasinha,2018; SinsInvalid,2019).

Towardneurodivergentarchitectureandspaces?

Inthisregard,wetakethepositionthatmanyneurodivergentmodes ofexistenceandexperiencearereflectionsofnaturalandvitalvariationin neuralandcognitivecapabilities,thatcanandshouldbevalued,andare notinherentlypathologicalorinferior.Wealsonotethatmanyautistic activistsandscholarsseethemselvesasnotdisabledbutashavinganautistic wayofbeing;oftendeliberatelyreversingtheterminologythatonlynames themashavingadeficit,byusingtermssuchasnormateandNTinorderto highlighthowtypicalbodiesandmindssimultaneouslyvaluethemselves overothers,whileassumingtheirownwaysofbeingasnonproblematic. However,ouruseof“neurodivergent”alsoencompassesmodesofexistence whicharesubjecttomuchdebateregardingtheirstatusasneurologicalillnessesordisabilities,andotherswhichperhapshavemorestabledefinitions. TheformermayincludeTourettes,schizophrenia,andpsychological

trauma,whilethelattermayincludeconditionsarisingfromneurodegenerativediseaseandinjurysuchasAlzheimers,learningdisabilitiesorbrain trauma.Thisisaboutwhetherparticular“mentaldifferencesareformsof illnessordisorderatall”aswellasthedifficultiesofcreatingaccuratediagnosticlabels(Radden,2019).Thiscanbeseeninthemultipleandpartial attempts through history(andacrossplace)todefinevariousformsofcognitivedifferenceintoclearandmutuallyexclusivecategories(Silberman, 2015).Inaddition,thelanguageusedinthesedefinitionshaschanged,away from the beliefofmentalillnessesas“evil,”as“willfulerror,”as“grave misfortune”or,attheveryleast,regardedasunwelcome(Radden,2019).

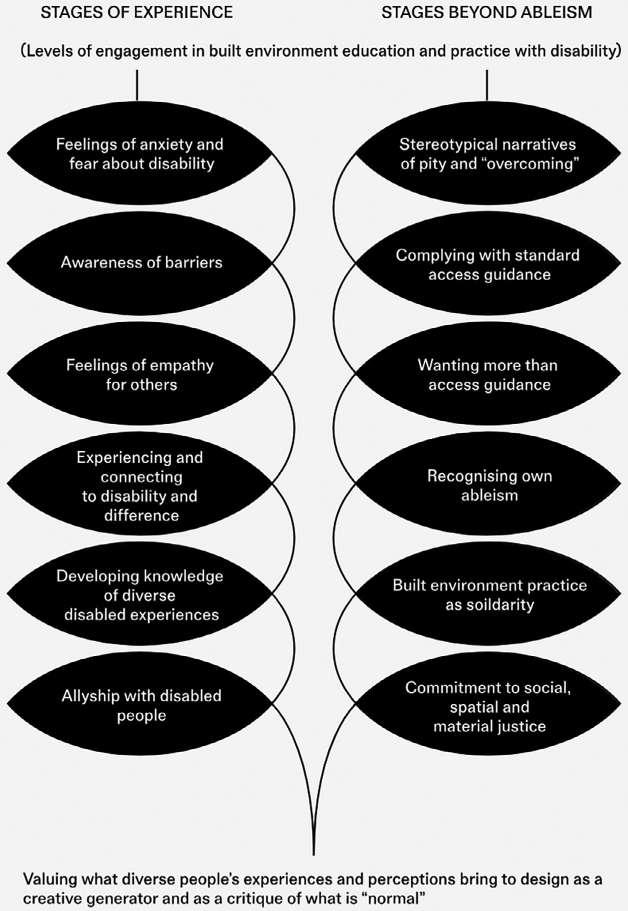

Atthesametime,disabledpeople’sperceptionsandexperiencesare—of course—verydiverse,intersectedwithotherkindsoflabel(bygenderor raceorsexualityforexample);sothatattemptsatimpairmentcategorization, and/orgeneralizationsaboutneedsandpreferences,arealwayspotentially fraught.JessThom,aneurodivergentperformerandwriter(seealso Chapter15 this volume) recentlycreatedadiagramthatexploresand explainsherownpersonalexperiencesofcomingtoidentifypositively andpoliticallyasadisabledperson.Called“AcceptanceandIdentity: SevenStages”(Thom,2020),itstartsfromthesocialmodelofdisability (alreadyoutlinedinthisintroduction)byseparatingoutpeople’svarious impairments(thatis,thefactsoftheirownbodymind)fromdisabilityas thelivedexperienceofattitudinalandmaterialbarriers,becauseofthat impairment.Thomthenexploresthedifferentstagesthroughwhichpeople maygoinunderstandingbothhowtheypositionthemselvesasdisabled,and howsocietypositionsthem.Theserangefromfeelingsofshockandgrief throughtoacceptance;andofmovingfromthefrustratingexperiencebarrierstovaluingthecontributionthatdisabledpeoplemake.Thisisrelevant here,becausealltoooftendisabledpeopleareaskedtoparticipateindesign processesasiftheyareauthenticrepresentativesforawholeimpairmentcategory.Thisisproblematicfortworeasons.First,itfailstorecognizeboth howmuchimpairmentscanvarywithinadisabilitycategoryaswellas acrosscategories.Second,itdoesnottakeaccountofthemultitudeofways disabledpeopleplacethemselvesinrelationshiptowidersocietalviews (Fig.1). Boys(2021) hasalsoexploredaversionofthisvariationinpositioningfornondisabledpeople,totryanddrawoutequivalentdifferences andjourneys,thatrecognizesaconsiderablerangeofattitudesto disability—fromfeelingsofpitytofullengagementwithenablingsocial, spatialandmaterialjustice(Fig.2).

Fig.1 DiagramadaptedfromJessThom’s “AcceptanceandIdentity:SevenStages,” as publishedontheTourettesheroblog2020(3rdSeptember).

Fig.2 Jos Boys(2021) diagramofanequivalentjourneyfornondisabledpeoplecalled “DisabilityandAwarenessfortheNon-Disabled:SixStages,” publishedonlineas Boys (2021) ShiftingtheGround:anessayonre-thinkingaccessandinclusion Molonglo(online).

Thisacceptanceofafluidityofdefinitionsof,expansivenessabout, andcontestedviewsover,whatitistobedisabledand/orneurodivergent, isthereforepartofabroaderinterestinhowdiversebodiesandmindsengage withbuiltspace.Here,similaritiesanddifferencesinaccessneedsaretobe found(withinandacrossimpairments,perceptionsandexperiences)inwhat makessupportivebuiltspaces.Thisisabouttracingtheemergentand dynamicpatternsofbothalignmentsandpotentialcontradictionsinour multiplewaysofbeingintheworld;andproposingthatthiscanbecritically andcreativelylearntfrom(forallbodyminds).Thatis,wesee neurodivergenceasacreativeplacetostart,asapotentialgeneratorofdesign ideas(RichardRogers,theworld-renownedarchitectwasfamouslydyslexic),andasachallengetonormativeassumptionsbuiltintoourmaterial surroundingsthatdisablesomeandenableothers.

Aseditors,wehaveasimilarexpansivenessinourdefinitionofarchitecture.Wehaveselectedcontributorswhounderstandarchitectureasmore thanitsbuiltproducts.Authorshaveexploredarchitectureanddesignasa processandpractice;asadynamicservicethatcanmeettheneedsofdiverse people;asasiteforperformanceandothercreativeactionsthatcanindicate newdesignpossibilities;andasbuiltspacethatsupportsnonnormative bodiesandmindsThisfocusonarchitectureasalwaysongoinganddynamic, ratherthanastaticthingfitswithmuchcontemporaryworkinthebuilt environmentdisciplines—understandingbuildingsandpublicspacesin termsoftheprocessesandpracticesthroughwhichtheyarebothcreated andoccupied.Thisisparticularlyrelevantwhenconnectedtoneurodivergence,asitdemandsacriticalengagementwithnormativeand NTassumptionsabouthowbuildingsshouldbedesigned;whoandwhat isvaluedinitsconventionalprocessesandpractices;whatbecomeframed assolutions;andwhatareexamplesofgoodpracticeforalternativesand improvement.

Chapteroutlines

Thisvolumeisdividedintothreesections—Frameworks,Advocacy, andPractices.Thefirstsectionpresentstheoreticalandmethodological frameworksformakingsenseoftheintersectionsbetweenneurodivergence, architectureandethics.Thereare,asthissectionwillargue,arangeofrelevanttheoriesaroundconceptualizingrelationshipsbetweenminds,bodies andbuiltspaceacrossneuroscience,neuroandbioethics,thesocialsciences, aswellassomeartsandhumanitiesdisciplines.Itisimportanttorepresenta

rangeofperspectivesandagendasthatengagewiththeseissues,aswellas illustratingthediversescholarshipthatsupportsthevariousformsof advocacyanddesignpracticesandprocessesthatareexploredinsubsequent sections.

TheAdvocacysectioncentersondisability-ledapproachestoneurodivergenceandarchitecture.Byadvocacy,wemeanscholarshipand activismthatstartsfrom,andsupports,aparticularcauseorpolicy;inthis case,foregroundingtheperceptionsandexperiencesofmultiple neurodivergentpeopleastheyengagewithbuiltspaceanditsdesign. Practices,thethirdsection,centersreal-lifeexamples—bothdesignprocessesandbuiltprojects—toexaminehowneurodivergenceasaconcept, andneurodivergentpeopleasaconstituencyacrossmanyvariations,are positivelyimpactingonarchitectureandthebuiltenvironment.

Frameworks

Webeginwithexaminingneuroethicsasascholarlyfieldinitsownright.In “TheNeuroethicsofArchitecture,”JudyIlles(Editor-in-Chief)and CamilleHuangarguethatmodernneuroscience,psychology,andbehavioralstudiesprovidetoolsthatcansignificantlyimproveourunderstanding ofhumanresponsestothebuiltenvironment.Theyarguethat,together, thesegiverisetoascience-basedframeworkforunderstandinghowarchitecturecanberesponsivetodiverseneurologicalneeds.IllesandHuang beginbyoutliningbasicunderstandingsofhowthebraininterpretsthebuilt environment,illustratingthatneuroscienceforegroundstheconnection betweenthebuiltenvironmentandindividuals’mentalresponses.They thengoontoproposeaneuroethicalframeworkthatreflectsthisscientific understandingofthebrain-environmentconnection;andhowthiscan informdesignsothatitisgenuinelyalignedwithhumanhealthand well-being,andfacilitativeofhumanflourishing.

ThesecondcontributionisJohnGardner’s“ScienceandTechnology Studies(STS)andtheneuroethicsofarchitecture.”Inthischapter, GardnerdrawsontheinterdisciplinaryfieldofScienceandTechnology Studies(STS)toconceptualizetherelationshipbetweenarchitectureand neurodiversity,andtoadvocateforinterventionsaimedatcreatingbuilt environmentsthataccommodateandcelebrateneurodivergentmodesof existenceandexpression.AnimportantadvantageofanSTS-informed approach,Gardnersuggests,isthatitencouragesustorecognizethevalue ofneuroscientificknowledgeofhumanresponsestothebuiltenvironment

whilealsoavoidingthepitfallsofneuro-reductionismorneuro-essentialism. Gardnerthenarguesthatthebuiltenvironmentreflectssocialnormsand values,includingthosethatprivilegeNTmodesofexistence,anditthereforeparticipatesinenablingandsupportingpeoplewhoapproximate “typical”individuals,whiledisablingandconstrainingthosewhodonot. Thechapterthusconcludesbyprovidingadescriptionofgeneralneuroethicalinterventionsthatcanbringaboutenvironmentsthataremoresupportiveandcelebratoryofneurodivergentmodesofexistenceand expression.

In Chapter3, “Disabilitystudies,neurodivergenceandarchitecture,” Jos Boysfirstoutlinessomekeyaspectsofdisabilitystudies,andthen considershowthisstronglyemergingfieldisintersectingwithscholarship andactivismacrossmanyvarietiesofneurodivergence—aswellaswider intersectionalities—todrawoutsomeofthisapproach’sunderlyingprinciples,aswellasitsvariousethicalchallengestoeverydaynegativeandableist attitudestodisability.Boysthenexploresconnectionswitharchitecture— bothasadisciplinarypractice,andasbuiltspace.Sheoffersexamplesofprojectsthatchallengethedeficitmodelofdisabilityandneurodivergence (whichassumesbeing“normal”andNTisinherentlyanaturallypreferred andsuperiorwayofbeing)bytreatingmentalnonnormativityasacreative generator,ratherthanaproblemtobesolved.Andsheexploresprojectsand processesthataimtowardafuturewherestartingfromneurodivergence enablesalternativewaysofthinkinganddoingarchitecture.

Inthefinalchapterinthissection,“Autoethnographicreflectionson architectural design forneurodivergence”AnthonyClarkeusesselected casestudiesfromhisownarchitecturalpracticetohighlighttheimportance ofthephysicalenvironmenttoindividualneeds,desires,andexpectations, usingdesignprocessesthatstartfromthemindandbodydifferencesof hisclients,andquestioningwhateffectsthismighthaveondesigningfor neurodivergence.Clarkeusesanauto-ethnographicdesignmethodology, whichhearguesisavaluabletoolforarchitectsanddesignerstoappreciate thebenefitsofreflectingon,andworkingwith,theemotivedimensionsof designandthedesignprocess.

Advocacy

ThefirstchapterinthissectionisbyJimSinclair.AsacofounderofAutism NetworkInternational(ANI)in1992andasitscoordinatorsincethen, theyhavebeenacentralfigureinthedevelopmentofautistic-ledactivism.

In“Culturalcommentary:Beingautistictogether,”writtenin2010withan extractreprintedhere,Sinclairnotesthatautisticpeoplearegenerallyseen byNTpeopleaslackinginabilitytosharecommoninterestswithothers, disconnectedfromsocialparticipationandfellowship,andunabletounderstandormanage“normal”socialbehaviorsandattitudes.Theysuggestthat forautisticpeople,thesituationisnotsoclear-cut,andthatisolationand withdrawalisasmucharesultofthedistresscausedbynormativedemands onbehavior.Duringthepast20years,facilitatedbytheavailabilityofthe Internet,moreandmoreautisticpeoplehavebeenreachingoutandforming connections,creatingcommunity,anddiscoveringtheirownstylesofautistictogetherness.ANIwastheprobablythefirstautisticcommunitytobe creatednaturalisticallybyautisticpeopleandremainsthelargest autistic-runorganizationtohaveregularphysicalgatheringsofautisticpeople.Inthisarticle,Sinclairreportsonthesocialandspatialculturethatsuch meetingscreate;drawingontheexperiencesoftheANIanditsretreat-style conferences,Autreat,toprovidereflectionsandguidanceonpreparing sharedautisticspaces.

In Chapter6, ProfessorMarieHarder,anautisticacademicwhospecializes insustainablewastemanagementandisbasedattheUniversityofFudan Shanghai,considersherownworkingenvironments.In“Self-madedesign notesforanautistic’soffice,”shearguesthatmeaningfulwork/occupationis abasichumanneedandthatmeaningfuloccupationforherrequiresplace andspacetoimmerseintacitthinkingprocesses.Thisisdevelopedasa principleforexaminingtherelationshipofherneurodivergencetovarious builtenvironmentattributes.Harderconcludesthatvaliddesignfor neurodivergentpersonssuchasherselfneedsaholisticandautoethnographic consideration,ratherthatchecklistapproachesandbimodalmedical descriptions.

ThethirdcontributiontothissectionisbyNatashaTrotman.“Equalities design: Toward post-normativeequity”describestheapproachusedto informandguidetheirpracticeasadesigner.Trotmanoutlinestheirown creativedevelopmentjourneyandtheassociatedtools,methodsand approachesdeveloped,aimedatenablingtheinterrogationandqueering ofnormative(includingneuronormative)assumptionsinordertocreate alternativebodymindexplorationsandexperimentaloutputs.Ratherthan simplisticdesignsolutionsthathavebeenpresentedasinclusive,thisworkis aboutcenteringintersectionalityandtheprofoundchallengesencountered bymultiply-marginalizedgroups.Thechapterarguesforthenecessityof

suchanapproachanddescribesaDesignExosystemFrameworkthatbuilds inequality,andthusethicalpositioning,rightfromthestart.Thechapter alsointroducesexamplesoftheimplicationsofthisapproach,through Trotman’sinvolvementwiththeWellcomeTrust’s DesignandtheMind initiative,focusedoncocreationandengagementwithneurodivergent, disabledandD/deafpeopleandgroups,andwhichproducedoutputs suchastoolkitsandapublic-facing5-dayprogramintheWellcome CollectionHub.

Inthefinalchapterforthissection,“Dialogicdrawing,”architect YeoryiaManolopoulouwritesabouttheLosingMyselfproject,developed fromtheperspectiveofarchitectsneedingtoknowmuchmoreabout dementia,inordertobetterinformthedesignprocess.Withthearchitect Nı´allMcLaughlin,sheengagedincriticaldialogueswithpeopleandcarers affectedbydementia,aswellasexpertsfromhealth,cognitive,andbehavioralfields.AsManolopouloustates,thesedialogues“soughttoexaminethe experiencesofpeoplelivingwithdementiaand,morefundamentally,how thebraincomprehendsspaceandtheimplicationsofthisforarchitecture.” Thesediscussions“questionedreductivedesignguidelinesandasked:What spatialcapacitiesdowehavethatwemightlosebecauseofdementia?What findingsfromneuroscience,anthropology,art,healthcare,andpolicy researchcanhelparchitectsdesignforpeoplelivingwithdementiaand, morebroadly,forallofus?”Manolopoulou’scontributiontothisvolume reflectsonsomeofthecontentofthesedialogues,engagingwithmore recentresearchandpolicyinitiativesoninclusivedesignasitrelatestobrain health.Indoingthis,italsoengageswithMikhailBakhtin’simportant theoreticalworkondialogueandthedialogicprocessofarchitecturedrawing.Sheconcludesbyarguingthat“manyofourlimitationsinunderstandingneurodivergenceholisticallyandimaginatively,bothasarchitectsandas citizens,canbeovercomebydevelopinglearningandcommunication processesthataretrulydialogic.”

Practices

ThefirstcontributioninthePracticessectionisbyarchitectAllenKong. Itpresentsexamplesofinclusivearchitectureforatypicalpeople,designed byAllenKongArchitects(AKA).ThedesignphilosophyofAKAisthat thequalityoflifeoftheindividualisfirstandforemost,andthatthisrequires addressingtheirindividualneedsinawaythatalsorecognizestheirsocial,

economic,andenvironmentalcontexts.Thechaptersummarizesthisdesign approachandpresentthreeAKAprojectsinAustralia:thePortMelbourne Hostelforparticularlyvulnerableelderlyindividualswhowouldotherwise behomeless;TheOdysseyHouseFamilyUnitsforindividualsreceiving therapyfordrugandalcoholaddictionandtheirfamilies;andthe Wallara-WintringhamPotterStreetRedevelopment,forindividualswith disabilitiesandtheirelderlyparentcarers.

Chapter10 isbyautisticartistSoniaBoue. “Notallsurfacescatchthelight atthesametime”presentsworkwrittenduringherArtsCouncilEngland (ACE)funded NeitherUseNorOrnament (NUNO)curatedexhibitionproject. Thischapterbothreflectson,andpresents,acuratedselectionofblogposts originallypublishedon TheOtherSide (Boue‘sWordpressblog).Thisboth documentsthedevelopmentoftheprojectandtheevolutionofherown thinkingaboutenablinginclusiveprocessesandprojects.Theaimsof NUNOweretwofold;toleadtheprojectautistically,andleveltheplaying fieldfortheautisticartistsontheproject.Usingamethodologyofworked iteratively(withthesupportofmentors),Boueexploredhowtomakeaccess forall—regardlessofneurologicalstatus—apriorityaboveallothercriteria, includingprojectdesignandoutcomes.Thisrecognizedthatallparticipants hadneedsthatrequiredaccommodation,anddemonstratedthatwhen accesswascentered,projectoutcomestookcareofthemselves.Boththe reflectionsandtheassociatedcollectionofwritingsprovideinsightsintoan outstandinglysuccessfulexperimentinaccessibleprojectdesign,whichcreatedapeakpositiveexperienceforparticipants.Boueconcludesbyexploring questionsaroundsustainingsuchinitiatives,andhowthespiritofNUNO mightbereplicatedortranslatedtoothercontexts.

Inthenextchapter,byJ.T.EisenhauerRichardson,theauthorreturnsto an installationartworkcreatedinMay2008entitledAdmissionandaprior DisabilityStudiesQuarterly(DSQ) (2009)articletitled“Admission:Madness and(Be)comingOutWithinandThroughSpacesofConfinement.” InvokingKarenBarad’s“re-turning”asaniterativeanddiffractivepractice, Richardsonconsidersneuroqueerintimacyandneuroqueertouchin relationtoboththeiroriginalartworkandtoexperiencesofconfinement withinpsychiatricspaces.Thiscentersexperiencesinarchitecturesof madness,includingrelationshipswithnonhumanactantsbeyondconstructs ofinsightandintentionality,throughaneuroqueerresponseof“Idon’t know.”Suchnot-knowingchallengestheexplanatoryimpulseofcriticality throughinsight.ExtendingErvinGoffman’sframingof“admission”within psychiatricspacesasdispossession,Richardsonarguesthatneuroqueertouch

andneuroqueerintimacyisintegraltoamorecomplexunderstanding ofpsychiatricarchitecturesofconfinementbeyondNTframesofagency andaction.

ThisisfollowedbyacontributionfromMollyMattaini,reprintedfrom YouthTheaterJournal (2019)called“Creatingautisticspaceinability-inclusive sensorytheater(AIST)”.ThisisanemerginggenreofTheaterforYoung Audienceswhichservesyoungpeoplewithautismandothercognitive disabilities.Distinctfromsensoryfriendlyorrelaxedperformances,theseproductionsbuildtheentireaestheticexperiencetocatertoanaudiencewithsensorydifferences.Thespacecreatedintheseproductionsmirrorthesocial conceptof“autisticspace”inwhichtheneedsofpeopleontheautismspectruminformthephysicalandsocialdesignoftheenvironment.Thischapter exploreshowAISTproductionscreateautisticspacethroughscriptdevelopment,audienceengagement,immersivedesign,softtransitions,sensory objects,andanaudience-centricdramaturgy.

In Chapter13 , TanyaPetrovichoutlines“Thevirtualdementiaexperience”(VDE),developedin2013.Itsaimistousegametechnology toprovidelearningexperiencesaboutdementiasoastoenablecarers, andotherslivingwithpeoplewithdementia,betterunderstandingof howtoprovideenablingsupport.Creatingavirtualworldallowed developerstoillustratehowthebuiltenvironmentmaybeinterpreted differentlybypeoplelivingwithde mentia.Petrovicharguesthatthe impactoftheexperienceonlearnershasbeenverypositiveinrelation totheircarepracticesandthattheVDEhasalsoofferedapowerful toolforunderstandingthebuiltenvironmentandtheprinciplesof dementia-friendlydesign.

Inthefollowingchapter,SarahWigglesworthandClareBondfrom Sarah Wigglesworth Architects(SWA)discusssomeofthepractice’sprojects.Aswithmanyofourotherauthors,“Designingwithneurodiverse childrenandadults:Learningadifferentlessonwitheveryengagement”take asastartingpointthespecificitiesandcomplexitiesofeachdesignprocess. SWAusesa“learningthroughdoing”methodthatcombinesprojectwork withresearchandknowledgebuilding.Theirchapterexploresthisapproach throughtwodifferentprojects,ClassroomfortheFutureatMossbrook SpecialSchoolinSheffieldUK,acompletedbuilding;andacollaborative researchprojectwithHabintegHousingAssociation.Boththeseprojects arefocusedoninclusiveandaccessibledesignforpeoplewithneurodiversities;withthelatterbuildingontheprinciplesofresearchandengagementwhichwereembeddedwithinthedesignofMossbrookSchool.

WorkingwithHabinteghasalsorequiredthetranslationoflessonsfromthe educationsectortotheresidentialsectorandbeyond;thusenablingthe updatinganddeepeningofthepractice’sunderstandingofhowadultsaswell aschildrenwithneurodiversitiesandotherphysicalimpairmentsnavigate thebuiltenvironmentwithineverydaylife.

Chapter15 “Relaxandresist:ReflectionsontheTourettesherorelaxed venuemethodology”isbyWilliamRenelandJessicaThom.InFebruary 2020,BatterseaArtsCentre(BAC)inLondonlaunchedastheworld’s firstRelaxedVenue,aimingtoradicallyembedaccessandinclusivity acrossalloftheiractivitiesbyutilizinganew“RelaxedVenue”methodology. ThismethodologywasdevelopedbyTouretteshero,adisabledand neurodivergent-ledCommunityInterestCompanyandisunderpinnedby Touretteshero’smissiontocreateaninclusiveandsociallyjustworldfordisabledandnondisabledpeoplethroughculturalpractice.Thischapteroutlines theprocessthroughwhichtheRelaxedVenuemethodologywascreated, focusingonmomentsofchangeatBACanddescribingthethreeRelaxed Venuecommitments:“NoNewBarriers,”“EqualityofExperience,”and “ReduceFuss.”RenelandThomarguethattheirRelaxedVenuemethodologychallengesthedepoliticizedunderstandingofaccessibilityasa check-list,anendgoalora“nicethingtodo”andsoundsacalltoaction formoreenvironmentsthataredesignedtosupportadiversityofbodies andmindstotakeupspacemeaningfullyandequitablytogether.

Thefinalcontributiontothissection,bydisableddancetheaterpractitionerRaquelMeseguer,iscalled“Chronicpain&chronicillness:Acrash courseincloudspotting.”Init,sheaskswhatitisliketonavigateourbuilt environmentinabodythatishurtorfatigued;andhowwemightreimagine therelationshipbetweenrestingbodiesandpublicspace.Workingfromher creativeandimmersiveproject, Acrashcourseincloudspotting,Meseguerisable todrawonnearly300storiesaccumulatedfrompeoplewithchronicpain, chronicfatigue,and/orotherdisabilitiesand/orneurodivergence.Thiswork aimstochallengetheetiquetteofourpublicspace,tomakehorizontalbodies morevisible,tore-frameandelevateactsofrest,andtoconveysomethingof thelivedexperienceofadisabilitylikechronicpain.Meseguercallsthisacrip practiceadvocatingforcripspaces:pocketsofnonnormativetimeandspace, wherebodymindsarewelcometorest.Shearguesthatrestenablesadifferent modeofbeingandofexperiencingtheworld:amorepoeticorientationthat shouldn’tbehiddenawaybutthatcanbeaproudandcentralpartsofourcityscapes.Shefinisheswithacallforthedesignofbeautifulandexquisiteresting spaces,thatcelebratedifference,andchallengeculturalattitudestowardpeople whopresentdifferentlyinpublic.