HANDBOOKOFCLINICAL NEUROLOGY

SeriesEditors

VOLUME137

MICHAELJ.AMINOFF,FRANÇOISBOLLER,ANDDICKF.SWAAB

ELSEVIER

Radarweg29,POBox211,1000AEAmsterdam,Netherlands

TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom

50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates

©2016ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicormechanical, includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,withoutpermissioninwriting fromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthePublisher ’spermissions policiesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyright LicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher(otherthan as may benotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperience broadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmay becomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusingany information,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationormethodsthey shouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessional responsibility.

Withrespecttoanydrugorpharmaceuticalproductsidentified,readersareadvisedtocheckthemostcurrent informationprovided(i)onproceduresfeaturedor(ii)bythemanufacturerofeachproducttobeadministered,to verifytherecommendeddoseorformula,themethodanddurationofadministration,andcontraindications.Itisthe responsibilityofpractitioners,relyingontheirownexperienceandknowledgeoftheirpatients,tomake diagnoses,todeterminedosagesandthebesttreatmentforeachindividualpatient,andtotakeallappropriatesafety precautions.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeanyliability foranyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceorotherwise,or fromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

ISBN:978-0-444-63437-5

ForinformationonallElsevierpublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/

Publisher: ShirleyDecker-lucke

AcquisitionEditor: MaraConner

EditorialProjectManager: KristiAnderson

ProductionProjectManager: SujathaThirugnanaSambandam

CoverDesigner: AlanStudholme

TypesetbySPiGlobal,India

Preface

Vertigoanddizzinessrankamongthemostcommonsymptomsinprimarycare,otolaryngology,andneurology.Causes varyfromharmlessbutbothersomeconditionssuchasbenignparoxysmalpositionalvertigotolife-threateningemergenciessuchasposteriorfossastrokes.Ourunderstandingofdiagnosis,pathophysiologicmechanisms,andeffective treatmentshasincreasedconsiderablyinthelasttwodecades.Newdevelopmentsincludealgorithmsforbedsidedetectionofvestibularstrokes,thedelineationofvestibularmigraineasoneofthemostfrequentcausesofrecurrentvertigo, descriptionofvariantsofbenignparoxysmalpositionalvertigo,devicesfortestingindividualsemicircularcanalsand otolithorgans,andtheadvancementofvestibularrehabilitationasthemostimportanttherapeutictoolinneuro-otology. Thisvolumeofthe HandbookofClinicalNeurology assemblescontributionsfromleadinginternationalauthorsto communicatethecurrentclinicalknowledgeofneuro-otologyandacomprehensivelistofreferences.Chapters1–14 dealwithbasicknowledgeandgeneralprinciplesofneuro-otology,suchasanatomy,physiology,epidemiology, historytaking,examination,andvestibularrehabilitation.Thisisfollowedbythedisease-specificChapters15–28, coveringallcommoncausesofvertigoanddizziness.Thenumeroustablesandfiguresinthisbookmakethefield ofvestibularscienceandmedicineevenmoreaccessible.

JosephM.Furman ThomasLempert

Contributors

A.Alghadir

DepartmentofRehabilitationSciences,Collegeof AppliedMedicalSciences,KingSaudUniversity, Riyadh,SaudiArabia

A.A.Alghwiri

DepartmentofPhysicalTherapy,Facultyof RehabilitationSciences,UniversityofJordan,Amman, Jordan

C.D.Balaban

DepartmentsofOtolaryngology,Neurobiology, CommunicationSciencesandDisorders,and Bioengineering,UniversityofPittsburgh,Pittsburgh, PA,USA

P.Bertholon

DepartmentofOto-Rhino-Laryngology,Centre HospitalierUniversitairedeSaintEtienne,SaintEtienne, France

A.Bisdorff

DepartmentofNeurology,CentreHospitalierEmile Mayrisch,Esch-sur-Alzette,Luxembourg

T.Brandt

GermanCenterforVertigoandBalanceDisordersand InstituteforClinicalNeurosciences,UniversityHospital Munich,CampusGrosshadern,Munich,Germany

A.M.Bronstein

Neuro-otologyUnit,ImperialCollegeLondon,Charing CrossHospitalandNationalHospitalforNeurologyand Neurosurgery,London,UK

C.Chabbert

IntegrativeandAdaptativeNeurosciences,Universityof AixMarseille,Marseille,France

M.Cherchi

DepartmentofNeurology,NorthwesternUniversity FeinbergSchoolofMedicine,Chicago,IL,USA

K.-D.Choi

DepartmentofNeurology,CollegeofMedicine,Pusan NationalUniversityHospital,Busan,Korea

J.G.Colebatch

NeuroscienceResearchAustraliaandDepartment ofNeurology,PrinceofWalesHospitalClinical School,UniversityofNewSouthWales,Sydney, Australia

A.I.Colpak

HacettepeUniversitySchoolofMedicine,Ankara, Turkey

K.E.Cullen

DepartmentofPhysiology,McGillUniversity,Montreal, Quebec,Canada

R.A.Davies

DepartmentofNeuro-otology,NationalHospitalfor NeurologyandNeurosurgery,London,UK

M.Dieterich

GermanCenterforVertigoandBalanceDisordersand DepartmentofNeurology,UniversityHospitalMunich, CampusGrosshadern;andMunichClusterforSystems Neurology(SyNergy),Ludwig-MaximiliansUniversity, Munich,Germany

J.M.Espinosa-Sanchez

OtologyandNeurotologyGroup,Departmentof GenomicMedicine,CentreforGenomicsand OncologicalResearch(GENYO),Pfizer-Universityof Granada-JuntadeAndalucia,GranadaandDepartment ofOtolaryngology,HospitalSanAgustin,Linares,Jaen, Spain

K.Feil

GermanCenterforVertigoandBalanceDisordersand DepartmentofNeurology,UniversityHospitalMunich, CampusGrosshadern,Munich,Germany

HandbookofClinicalNeurology, Vol.137(3rdseries) Neuro-Otology

J.M.FurmanandT.Lempert,Editors http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63437-5.00001-7 ©2016ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved

Anatomy,physiology,andphysicsoftheperipheral

vestibularsystem

H.KINGMA* ANDR.VANDEBERG

Department ofOto-Rhino-LaryngologyandHeadandNeckSurgery,MaastrichtUniversityMedicalCentre,Maastricht, theNetherlandsandFacultyofPhysics,NationalResearchStateUniversityTomsk,Tomsk,RussianFederation

Abstract

Manymedicaldoctorsconsidervertigoanddizzinessasthemajor,almostobligatorycomplaintsinpatients withvestibulardisorders.Inthischapter,wewillexplainthatvestibulardisordersresultinmuchmore diverseandcomplexcomplaints.Manyoftheseothercomplaintsareunfortunatelyoftenmisinterpreted andincorrectlyclassifiedaspsychogenic.Whenwereallyunderstandthefunctionofthevestibularsystem, itbecomesquiteobviouswhypatientswithvestibulardisorderscomplainaboutalossofvisualacuity, imbalance,fearoffalling,cognitiveandattentionalproblems,fatiguethatpersistsevenwhenthevertigo attacksanddizzinessdecreasesorevendisappears.Anotherinterestingnewaspectinthischapteristhatwe explainwhythefunctionoftheotolithsystemissoimportant,andthatitisamistaketofocusonthefunctionofthesemicircularcanalsonly,especiallywhenwewanttounderstandwhysomepatientsseemto suffermorethanothersfromthelossofcanalfunctionasobjectifiedbyreducedcaloricresponses.

INTRODUCTION

Intheirprefacetothebook, MammalianVestibularPhysiology,publishedin1979,thefamousvestibularscientistsWilsonandMelvillJonesmadeaperceptive statement: “Itiseasytounderratetheimportanceofa sensorysystemwhosereceptorisburieddeepwithin theskullandofwhoseperformanceweareusuallynot aware” (WilsonandMelvillJones,1979).Thisstatement is stilluptodate,asmanydoctorsareunawareoftherelevanceofthevestibularsystemindailylifeandalsothink thatcentralcompensationandsensorysubstitution almostcompletelydealwithvestibularlossandreduce complaintstoaminimum.Also,inunilateralloss,itis oftenstatedthatthehealthylabyrinthwilltakeover. Howabsurdsuchastatementis,becomesclearifwe claimthatlosingoneearoroneeyeisofnoimportance aswecanstillhearwithoneearandseewithoneeye. Losingonevestibularorgan,likelosingoneearoreye, resultsinadisturbingasymmetry.Bilateralvestibular

areflexia(thereisnotevenacommonwordforitinlay language)isamajorhandicaplikedeafnessorblindness. Butapparently,symptomsassociatedwithbilateralvestibularareflexiaareoftennotrecognized,leadingtoadelay ofmanyyearsbeforeacorrectdiagnosisismade(vande Bergetal.,2011;Guinandetal.,2015a;Guyot,2015).The majorreasonisthatthefunctionofthevestibularsystemis poorlyunderstoodbybothdoctorsandpatients.This unawarenessalsoledtoproblemsinobtainingpermission todevelopavestibularimplantforhumans,verydifferent fromthedevelopmentofcochlearimplantsseveral decadesago.Onlyafterpublicationofanumberofscientificarticlesshowingtheimpactandincidenceofsevere bilateralvestibularlosswasaSwiss–Dutchresearchteam allowedtoexecutethefirsthumanvestibularimplantation inAugust2012(Pelizzoneetal.,2014;PerezFornosetal., 2014;Guinandetal.,2015b).

Thisallillustrateshowpoorlythefunctionandrelevanceofthevestibularsystemisunderstoodinclinical practice,andthisiswhathasmotivatedustowritethis

*Correspondenceto:HermanKingma,DepartmentofORLandHeadandNeckSurgery,MaastrichtUniversityMedicalCentre, Maastricht,theNetherlands.E-mail:kingmaherman@gmail.com

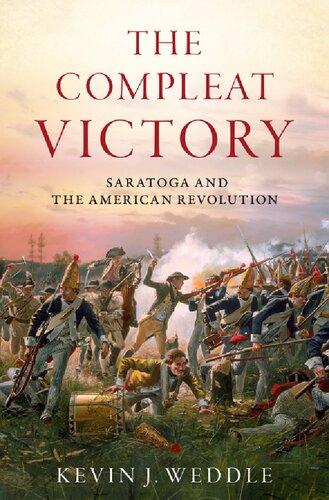

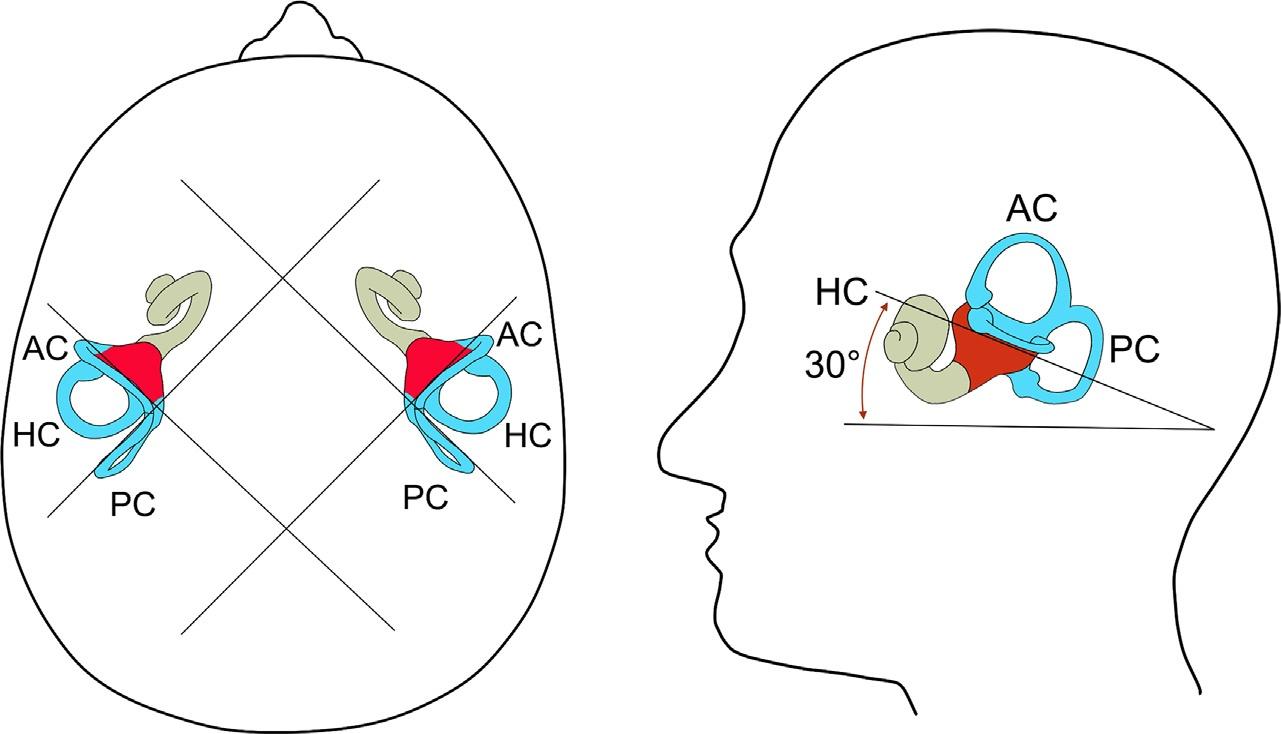

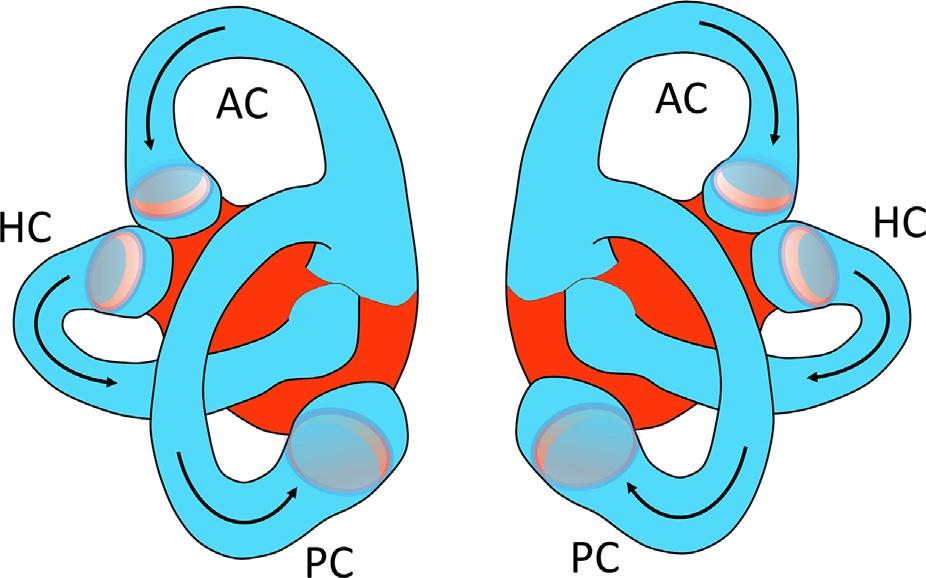

Fig.1.3. Schematicdrawingoftheorientationofthetwolabyrinthsintheskull.HC,horizontal(orlateral)canal;PC,posterior canal;AC,anterior(orsuperior)canal.

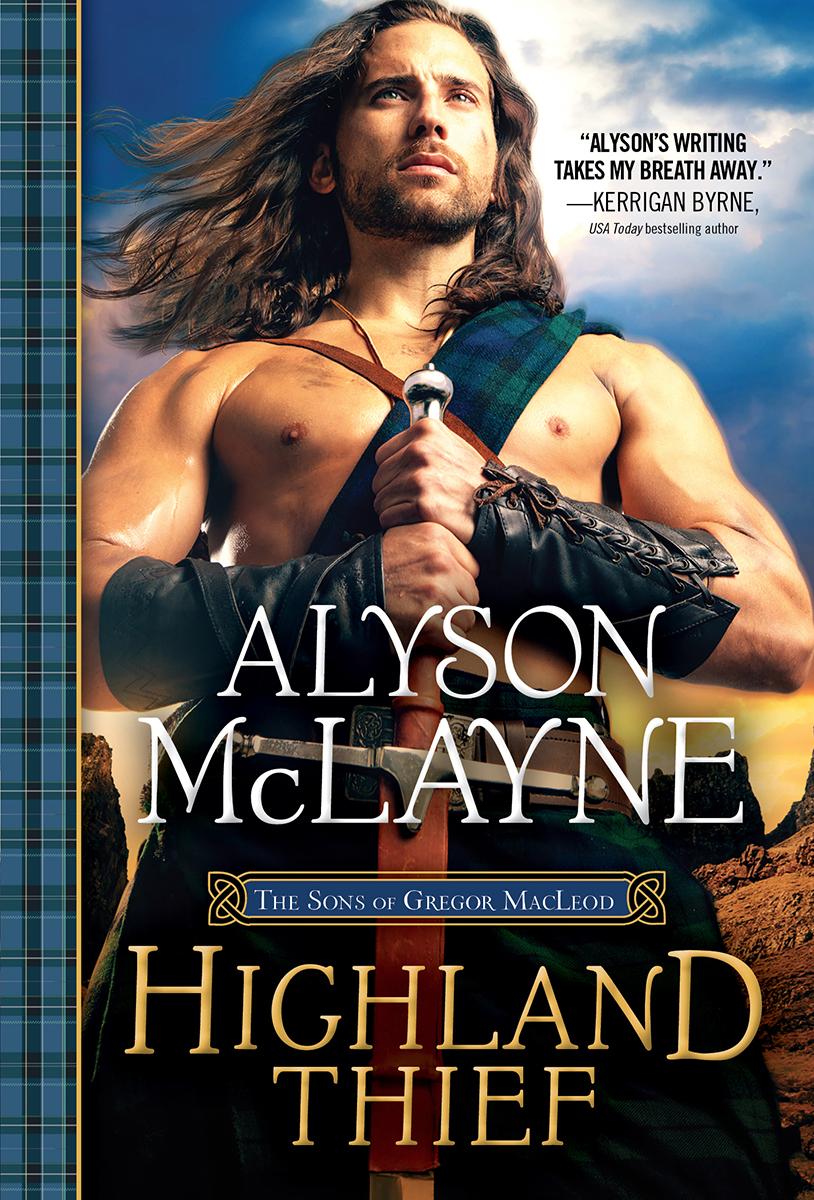

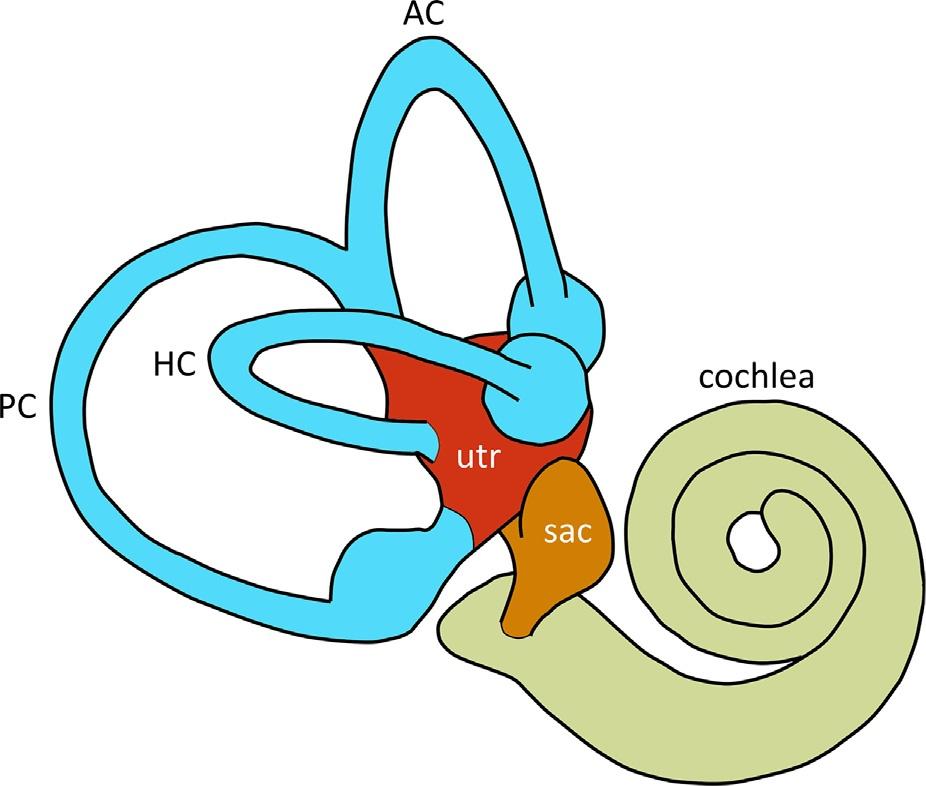

Fig.1.4. Schematicdrawingofthe right membranouslabyrinth:HC,horizontal(orlateral)canal;PC,posteriorcanal; AC,anterior(orsuperior)canal;Utr,utriculus;Sac,sacculus.

Thevestibularhaircells(Fig.1.7)arecomposedof acellbodyandabundleofciliaontopofthem,onaverageabout50stereociliaandonekinocilium(Hudspeth andCorey,1977;frog’ssacculus).Thestereociliaform abundleofciliathatincreaseinlengththecloserthey aretothekinocilium.Ontheirtop,theciliaaremechanicallyinterconnectedbyelastictiplinks.Thetiplinks maketheciliaofonehaircellmovetogetheruponaccelerationsandarealsothoughttomechanicallyopenand closeionchannelspositionedontopofthestereocilia. Thekinociliumisthelongestcilium,thatisdeflected themostbysmallmovementsofthecupulainthe canalsandofthemaculainthevestibule;butthanksto thetiplinks,allciliawillmoveinsynchronywithit andtherebyenhancetotalsensitivity.

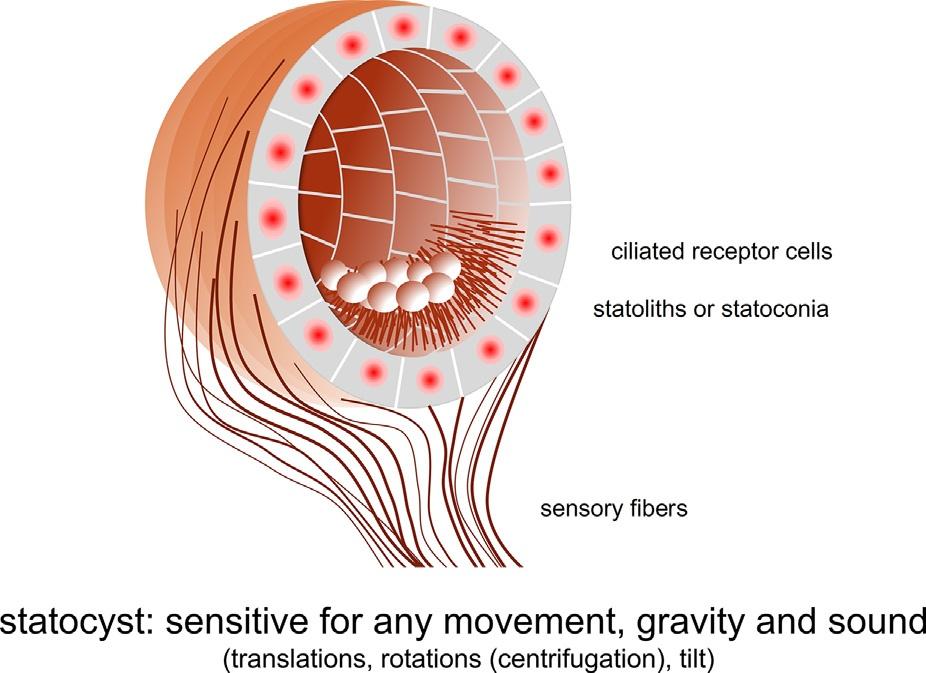

Fig.1.5. Schematicdrawingofthestatocyst:thestatolith organininvertebrates.Thestatocystisamechanoreceptorsystemthatissensitiveforanymovement,tiltandsound.

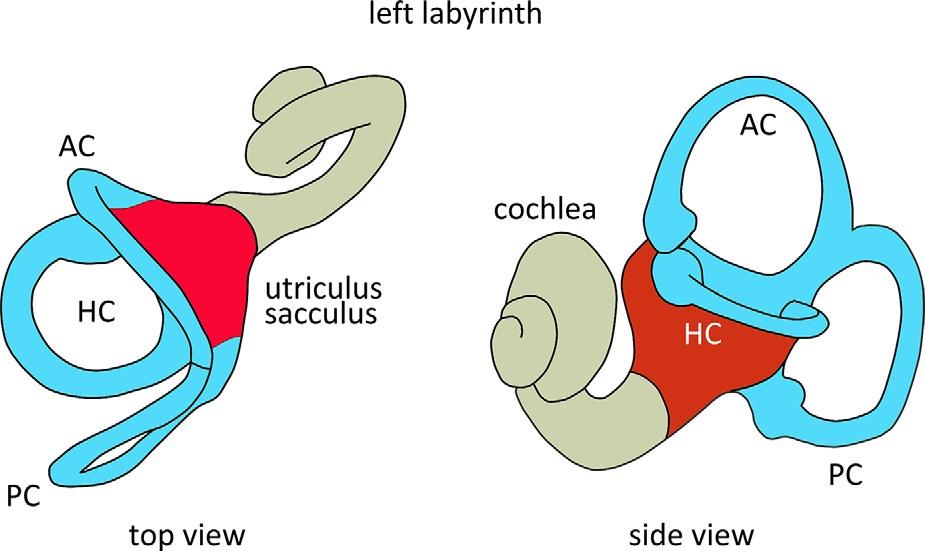

Fig.1.6. Topandsideviewoftheleftlabyrinth.HC,horizontal(orlateral)canal;PC,posteriorcanal;AC,anterior(orsuperior)canal.Thevestibularlabyrinthreachesitsmaturesize between17and19weeksofgestationalage.Adetailedquantitativedescriptionofthedimensionsofthehumanlabyrinthis givenby JefferyandSpoor(2004).

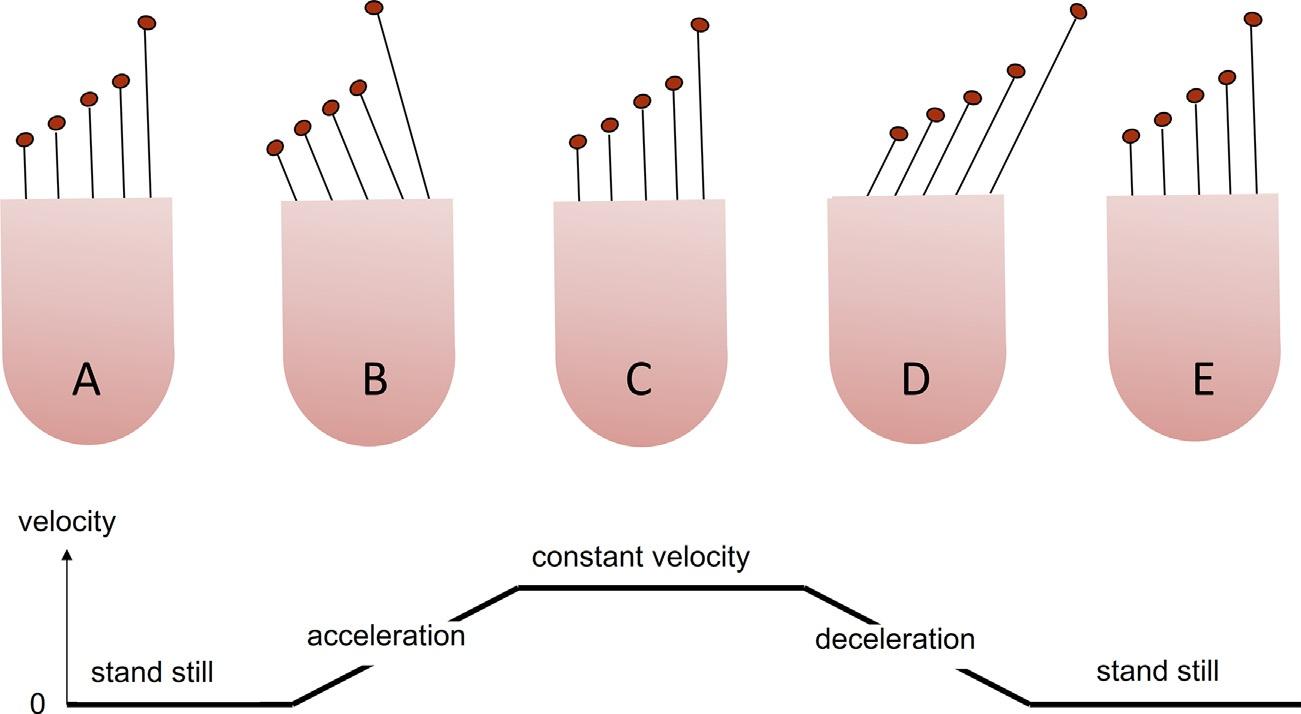

Nowtheerectpositionoftheantennaindicatesconstant velocityorstandstill.Upondecelerationofthecar,dueto theinertiaoftheorange,theantennawillbendforwards. Nowtheinclinationoftheantennaisproportionaltothe deceleration.Duetoitselasticity,theantennawillreturn toitsverticalorientationassoonasthecarstops.When wetiltthecar,theantennawilldeflectinthedirection oftiltoveranangleproportionaltothetiltanglerelative tothegravityvector.Nodistinctionispossiblebetween tiltandtranslation(comparewith Figs.1.11 and 1.12). Also,whenwestarttorotateandholdtheantenna upright,theantennawillstarttobendoutwardsdueto centrifugalforce.

Theotolithsystemissensitivetolinearaccelerations, rotations/centrifugationandtiltthankstotheprincipleof inertiaofmass.Assumethattheheadundergoeslinear acceleration(Fig.1.11).Thelowerpartoftheutricular membraneimmediatelyfollowstheheadmovement, buttheotoconiaonthetopofthemembranewilllag behind,resultinginadeflectionofthecilia.Thisbending causesdepolarizationorhyperpolarizationofthehair cellsdependingonthedirectionofdeflectionofthecilia (Fig.1.7).Thehaircellsofthemaculaarepolarizedinall directions,incontrasttothesemicircularcanals.Atilt relativetothegravityvectororcentrifugationalso inducesashearforceintheplaneoftheotoconial membraneandadeflectionofthecilia.Theotolith organscannotdistinguishbetweenheadtilt,rotation, andheadtranslation(forexample,anaccelerationforwardsleadstoasimilardeflectionoftheciliaasabackwardtiltofthehead: Fig.1.11).Theonlyexceptionto thismaybethattheeccentricityoftheotolithmembranes canbedifferentrelativetotherotationaxis.Thismay resultinadifferenceindirectionand/orstrengthofthe centrifugalforcesactingupontheotolithmembranes. Whetherthisprovidesaphysiologicallyrelevantandsufficientsensitivitytodiscriminatebetweenrotations

Fig.1.12. Schematicdeflectionpatternoftheciliaofthehair cellsintheutriculusandsacculusupontilt.

versustiltortranslationisstillthesubjectofstudy.At constantrotationalheadvelocity,thecanalsarenotstimulated.However,duringbothconstantandchanging rotationalheadvelocitytheotolithsystemisstillstimulatedduetocentrifugalforce,probablyhavingasupportingandregulatoryfunctionforthecanals(seebelow).

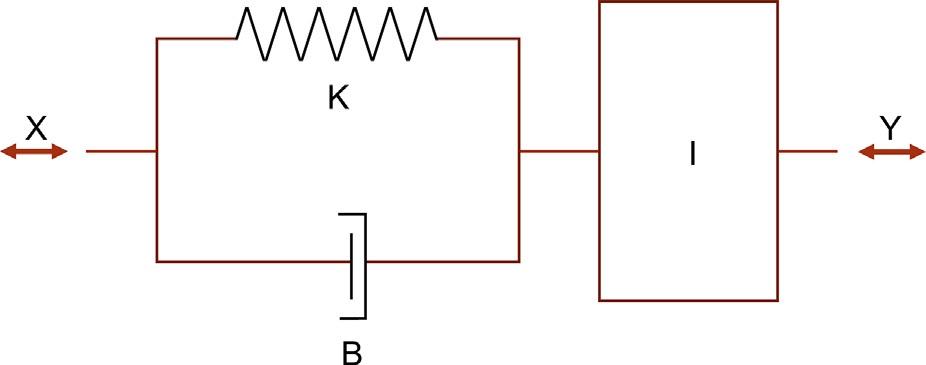

THEORETICMODEL

Duringlinearheadacceleration,centrifugation,orhead tilt,theotoconiamassshiftsrelativetothemaculadue tootoconialmassinertia,causingopposingviscousfrictionandanelasticforce.Thereforetheotolithorgan semicircularcanalscanbemodeledsimilarlytothesemicircularcanalswithasimplemechanicanalog,using inertia(I ),viscosity(B),andelasticity(K )asphysical quantities(Fig.1.13).Themomentofinertiaisgiven

Fig.1.11. Schematicdeflectionpatternoftheciliaofthehaircellsintheutriculusandsacculusupontranslation.

Fig.1.13. Mechanicalanalogofthestatolithorgan: I,otoconiamassinertia; B,viscousfriction; K,elasticrestoringforce; x,positionofthehead; y,positionoftheotoconia; □, x y, relativedisplacementoftheotolithmembrane.

by I y,themomentofviscousfrictionby B _ d,and themomentofelasticityby K d,whichwouldlead toasecond-orderdifferentialequationsimilartothe semicircularcanals.Inthecaseoftheotolithorgan,however,sincetheotoconialmassisimmersedinendolymph fluidofdensity re,anylinearaccelerationwillgeneratea buoyancyforceactingaccordingtoArchimedes’ principleinthedirectionofimposedaccelerationandequalto re =ro ðÞ I x,with ro thedensityoftheotoconialmass. Therefore,thesecond-orderdifferentialequationofthe otolithorganis:

1 re ro I x ¼ I d + B d + K d

with € x linearheadacceleration, € y linearotoconiaacceleration,and d relativedisplacementoftheotolithicmembrane,using d ¼ x y (MelvillJones,1979;Kingmaand Janssen,2013).Thetransferfunctioncanbewrittenas:

€ x s ðÞ¼ 1 re ro I I s2 + B s + K

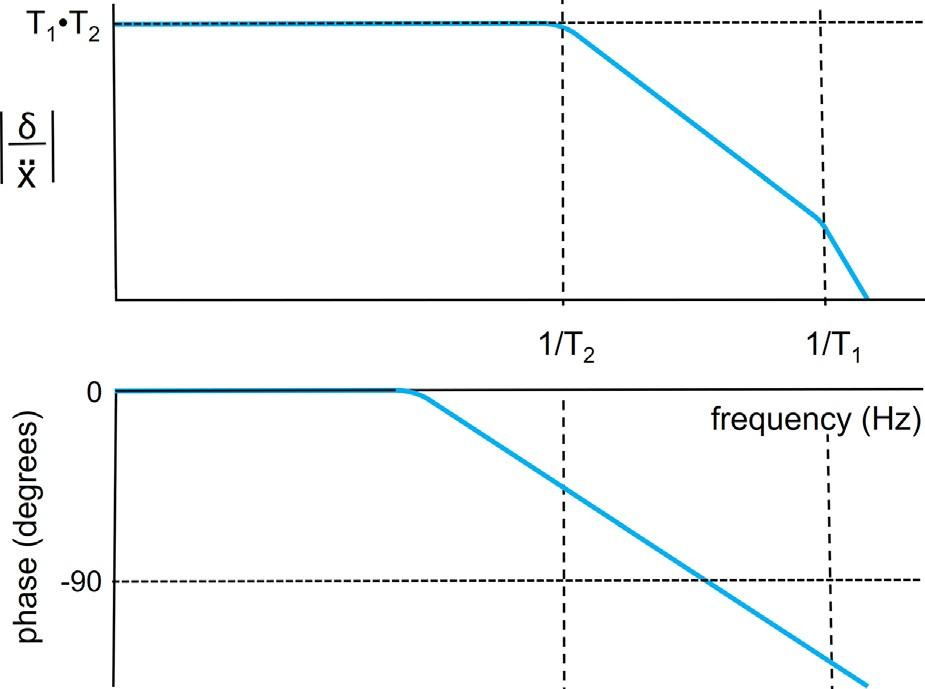

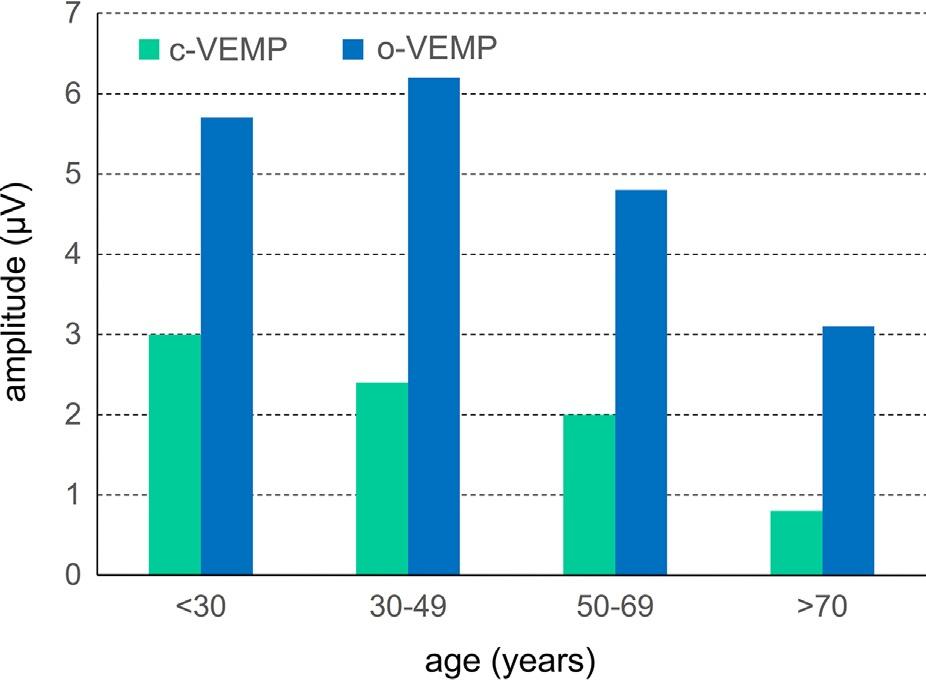

withlinearheadacceleration x asinputandrelativeotolithicmembranedisplacement d asoutput.Theformof thistransferfunctionisshownin Figure1.14A,using thefactthat I/B (T1 0.1s)issmallerthan B/K (T2 1s). Theotolithorganissensitiveforconstant(0Hz)and low-frequencylinearaccelerations.Becauseagravitationalaccelerationandacorrespondinglinearacceleration ofthesystemarephysicallyequivalent(Einstein’sequivalenceprinciple),theotolithorganscannotdistinguish betweenpureheadtranslations,headtilts,androtations, unlesstheymakeuseofaspecificarrangementofthe direction-sensitivehaircellsinthesensoryepithelium. Therelativeotolithmembranedisplacement d inresponse toconstantlinearaccelerationissimilartothecupuladisplacementinresponsetoangularacceleration,asshownin Figure1.12. Agrawaletal.(2012) foundadecreasein amplitudeofthecervicalandocularvestibular-evoked myogenicpotentialswithage,suggestinganage-related declineofthestatolithsystem(Fig.1.14B).

SEMICIRCULARCANALS

Asshownin Figure1.4,threesemicircularcanalscanbe identifiedinthevestibularlabyrinth:thelateral,posterior,andanteriorcanalthatslightlydifferinsize:thelateralcanalhasadiameterofabout2.3mm(SD 0.21),the posteriorcanal3.1mm(SD 0.30),andtheanteriorcanal 3.2mm(SD 0.24).Thecanalsareorientedmoreorless orthogonallytoeachother(Fig.1.4);theorientationof allcanalsvariesamonghealthysubjects(SD between 4.1° and5.4°).Theinnerdiameterofthecanalsisestimatedtovarybetween0.2and0.3mm(see Melvill Jones,1979).

Fig.1.14. (A)Bodeplotofthefrequencyresponseofthetransferfunctionequation4,representingthedynamicresponseofthe mechanicalanalogoftheotolithorgan.Uppertrace:amplitudespectrum(gain ¼ sensitivity).Lowertrace:phaseasafunctionof frequency.(B)Responseamplitudesofc-VEMP(asummedtoreflectsaccularfunction)ando-VEMP(assumedtoreflectutricular function)asafunctionofage(afterAgrawaletal.).

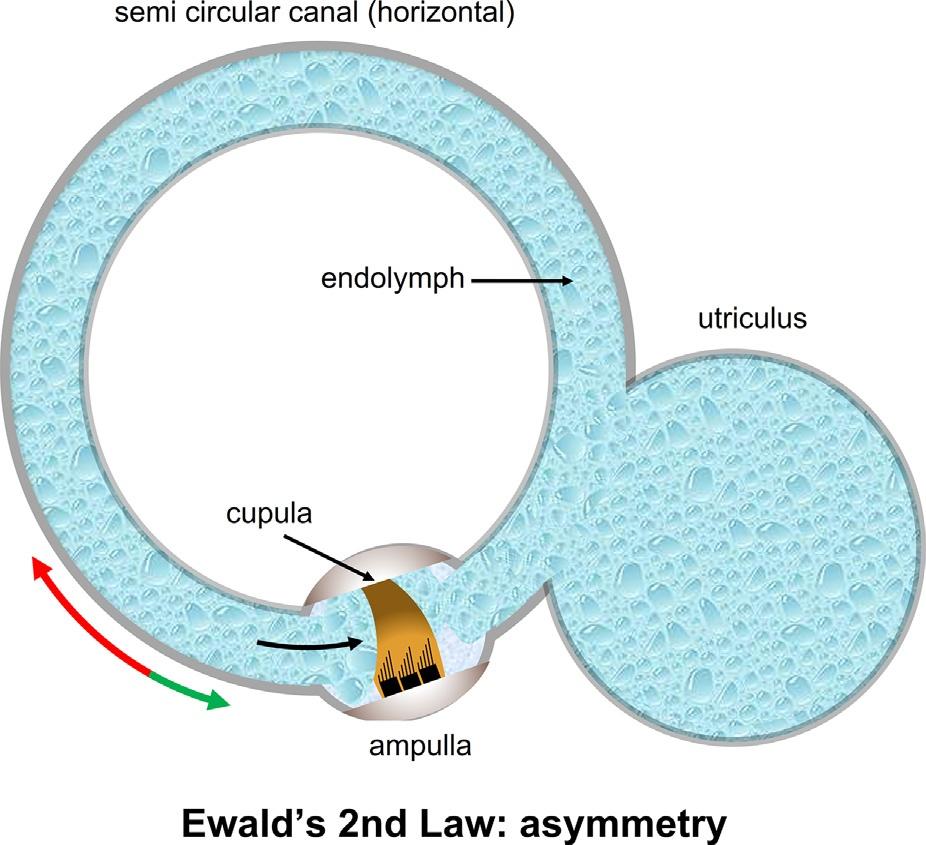

Fig.1.15. Schematicpresentationofthesemicircularcanalswiththecupulaholdingthehaircells.Duetothesimilarorientationof allhaircellsinthecupula,theasymmetricsensitivityofthehaircellsresultsinanasymmetricsensitivityofthesemicircularcanals.

Fig.1.16. Backviewofthetwovestibularlabyrinths.Thearrowsindicatethepreferred(maximumsensitivity)rotationdirection ineachcanal.HC,horizontalcanal;PC,posteriorcanal;AC,anteriorcanal.Notethatthedirectionofthesensitivityofthecanalsis oppositefortheHCcomparedtothatoftheACandPC(oppositeorientationofthehaircellsinthecupulae).

Thehaircellsofthecanalsarelocatedinthebasalpart ofagelatinousmass,thecupula,thatextendsthroughthe ampullaofeachcanalandformsaflapthatclosesthe semicircularcanal,preventingendolymphfrompassing theampulla(Fig.1.15).Theciliaextendintothecupula.

Asindicatedabove,thehaircellshavethehighestsensitivityfordeflectionstothekinocilium:thepolarization direction.Inthecupulaallhaircellsarearrangedwiththe samedirectionofpolarization.Asaconsequence,the receptorpotentialofallhaircellsinacupuladecreases orincreasesinsynchronyuponacupuladeflection. Butagain,asthemaximumsensitivityisinthepolarizationdirection,thereisalsoapreferreddirectionofa cupuladeflection,explainingtheasymmetricsensitivity ofeachsemicircularcanal:actually,eachcanalismost sensitiveforrotationsinthedirectionofthatspecific canal(Fig.1.16).

Thepolarizationdirectionofthehaircellsinthecupula ofthehorizontalcanalissuchthatthecanalismoresensitiveforacupuladeflectiontowardstheampulla(ampullopetal),whichcorrespondstoaheadrotationinthe oppositedirection(arrow;seeexplanationbelowrelated tothephysicsofcupuladeflection).Thepolarization directionofthehaircellsinthecupulaofthevertical canalsissuchthatthecanalismoresensitiveforacupula deflectionawayfromtheampulla(ampullofugal),which againcorrespondstoaheadrotationintheoppositedirection(arrow).Asaruleofthumb,eachcanalismaximally sensitiveforrotationsinthedirectionofthatcanalabout anaxisorthogonaltotheplaneofthatcanal.

Throughthisorientationwearesuppliedwiththree pairsofcanalswithacomplementaryandopposingoptimalsensitivity(Fig.1.16):(1)theleftandrighthorizontalcanal;(2)theleftanteriorandrightposteriorcanal;

Fig.1.17. (A)Clockwiseangularaccelerationofthecanalsleadstoaampullopetalendolymphaticflowandadeflectionofthe cupulaandhaircellsthatallhavethesamepolarisation.Clockwiseangularaccelerationleadstocupuladeflectionintheopposite direction.(B)Whenrotationvelocitybecomesconstant,thecupulastartstomovebacktotheoriginal(resting)position,which takesabout20secondsonaverage(timeconstantabout6seconds).Thisimpliesthatitisnotpossibletodistinghuishonthebasisof canalinputtothebrainbetweenstandstillandconstantrotation.

Fig.1.18. FirstlawofEwald:cupuladeflectionwillbemaximalforrotationsaroundanaxisorthogonaltotheplaneinwhich thecanalissituated;cupuladeflectionwillbeminimalforrotationsaroundanaxisintheplaneinwhichthecanalissituated.

and(3)therightanteriorandleftposteriorcanal.Thesensitivity(gain)ofthesemicircularcanalissuchthatitgeneratescloseto1spike/sper °/sat0.5Hzintheafferent nervefibers(YangandHullar,2007).

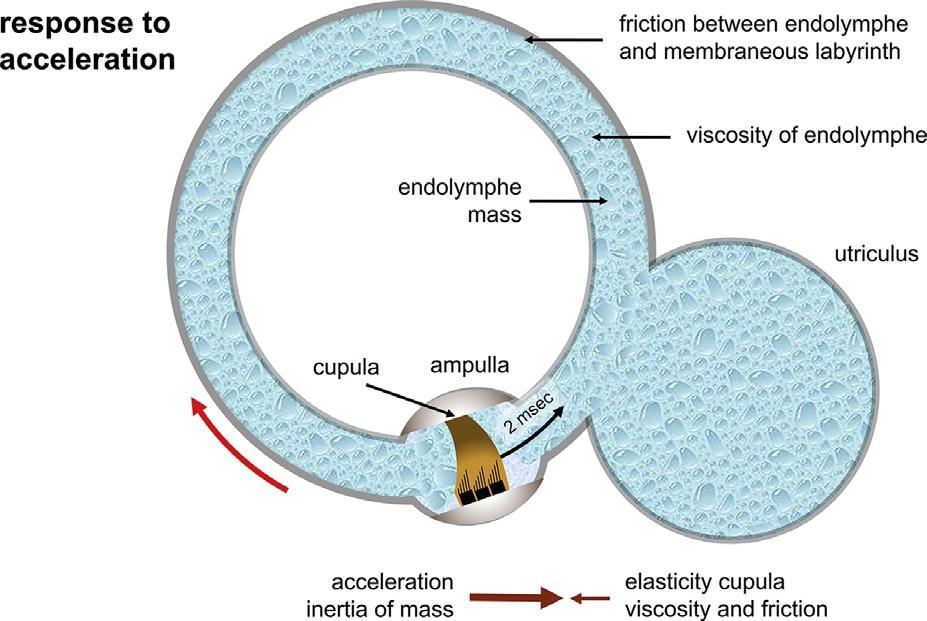

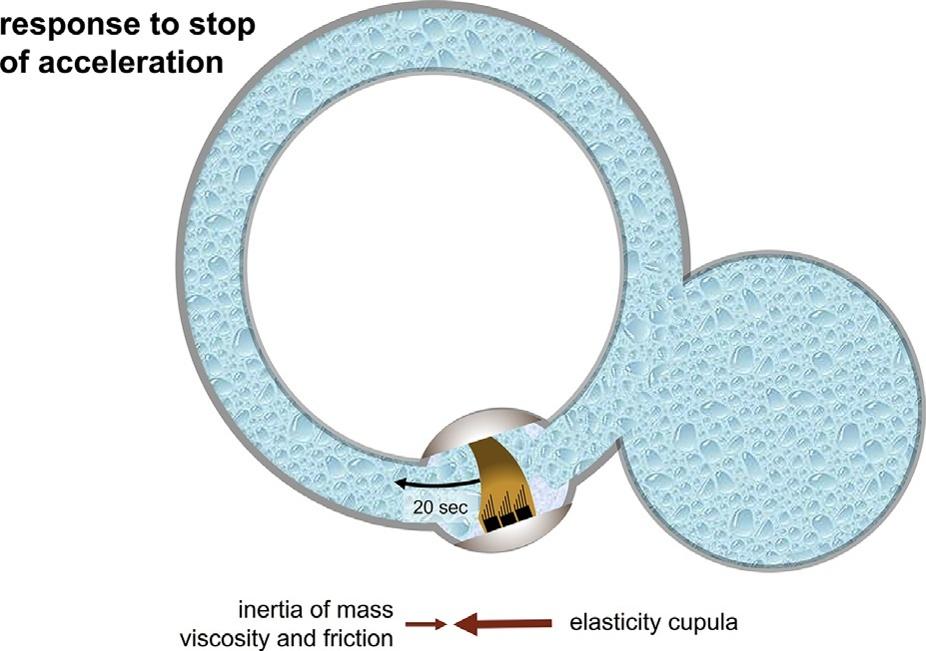

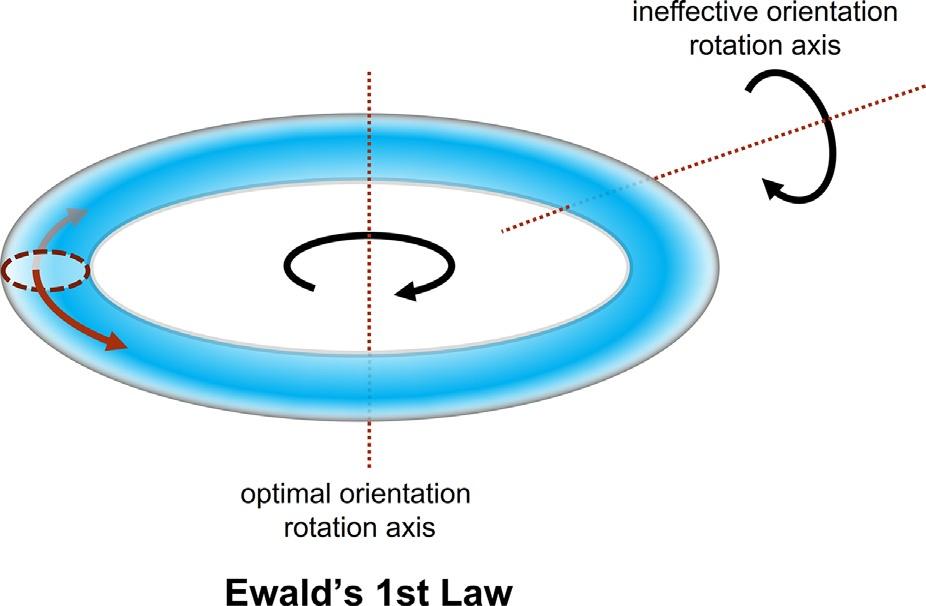

Whentheheadisrotated,theendolymphfluidlags behindduetomassinertiaandexertsaforceagainst thecupula(Fig.1.17A),causingthecupulatobend. Whenconstantrotationisreached(Fig.1.17B)andaccelerationbecomesnil,thedrivinginertialforcewillbecome niltoo(Newton ’slaw:force ¼ mass acceleration).Now thecupulawillbendbacktoitsoriginalposition,driven bythecupulaelasticityagainsttheviscosityoftheendolymphandthefrictionbetweenendolymphandmembranouslabyrinth.Theendolymphwillmovemaximally whentherotationaxisisorthogonaltotheplaneinwhich thecanalisoriented(Fig.1.18;theendolymphandcupula

willnotmovewhentherotationaxisisintheplaneofthe canal:Ewald’sfirstlaw).Asmentionedalready(Fig.1.1), theimpactofrotationonanindividualcanaldoes notdependonthedistancebetweentheaxisofrotation andthecenterofthecanal – parallelaxistheorem (Feynman,2011).Incontrast,thecentrifugalcomponent relatedtorotationdependsonthelocationofthelabyrinth relativetotherotationaxis.

Thebrainreceivesoppositesignalsfromthetwolabyrinthsanddetectsthedifferencebetweenbothofthem, whichinengineeringtermsisconsideredasworkingasa differentialamplifier.Theredundancyinasystemwith twolabyrinths(similartohearingandvision)makesit lessvulnerableforunilaterallossoffunction.But,also, detectingthedifferencebetweenthetwooppositely sensitivelabyrinthsenhancesthesensitivitytwofold, whereasacommondisturbancefromoutsideissubtracted(common-moderejection).

PHYSICSOFTHECANALS

Ananalogofacanalwithoutcupulaisaclosedbottle completelyfilledwithwater(withoutanyairontop) fixedonaturntable.Assoonastheturntablestartsto rotate,thebottlewillfollowtherotationimmediately. However,duetotheinertiaofmass,thewaterwilllag behindandonlyafterawhile – duetotheadhesionof thewatertothebottlewallandtheinternalcohesionof thewatermolecules – willthewaterstarttorotateand thenrotatewiththesameangularvelocityasthebottle andturntable.Withoutthisfriction(adhesion)andviscosity(cohesion),thewaterwouldnotmoveatall;with morefrictionandviscositythewaterwillfollowthebottlemovementfaster.Besidesfrictionandviscosity,the

totalmassandspecificmassofthefluidorinertiaplaya crucialrole:thegreaterthefluidmass,themoreforce (acceleration)isneededinordertomovethewater.Friction,viscosity,mass,andaccelerationalldeterminehow muchthewaterlagsbehindthebottlemovementand overwhichangleitwillbedisplaceduntilthewater hasreachedthesameangularvelocityasthebottle.As longastheturntable,bottle,andwaterrotateataconstant velocity,nofurtherchangewilloccur.Theangleover whichthewaterisrotatedcomparedtothebottleisproportionaltotheappliedangularaccelerationofthebottle. Assoonastheturntablestops,thebottlewillstopaswell, butthewaterwillstillrotateinsidethebottle.Thevelocityofthewaterwilldecreaseovertimeduetothefriction betweenbottleandwaterandultimatelythewaterwill cometoacompletestandstill.Ifthedecelerationisthe sameastheacceleration,thesametimewillbeneeded forthewatertocometoastandstillandthewaterwill haverotatedtoexactlythesamepositionasinthebeginningoftheexperiment:nonetrelativeangulardisplacementisleft.Infact,decelerationandaccelerationneed notbethesame:thesamepositionisalwaysreached whenthestepsinvelocityduringaccelerationanddecelerationareoppositebuthavethesamemagnitude.For example,thevelocitystepisthesamebutopposite (120°/sand –120°/s)whenweacceleratein12seconds with10°/s2 to120°/s,andthebottlestopswhenwedeceleratein2secondsby60°/s2 from120°/stostandstill. Sotherelativedisplacementisproportionaltothevelocitystep: ¼ acceleration Tacceleration.Thishasadirect clinicalapplication:velocitystepsareusedwidelyin vestibulardiagnosticsusingrotatorychairs.

Whenweputaverylightfluidorgas(lowspecific mass)inthebottle(decreasingthemassinertia)oravery viscousfluidthathasastrongadherence(highfriction)to thebottlewall,thedisplacementofthecontentrelativeto thebottlewillbealmostnegligible.

So,therelativedisplacementincreaseswithmass, decreaseswithfriction(adhesionandcohesion),and increaseswiththemagnitudeofthestepinvelocity. Anytranslationoftheturntableandbottleontopwill notleadtoanymovementofthewaterasthewatercannot becompressed.Thewaterwillonlystarttomoveby rotation.

Thesituationisslightlymorecomplexinthesemicircularcanal:herethecupulapreventstheendolymphfrom rotatingfreelyinthecanal(Fig.1.15).Thecupulacanbe consideredasanelasticmembranethatcanslightlybend inbothdirections.Assoonasthecanalstartsrotating,the endolymphlagsbehindduetoitsinertiaofmass.Again, thelessfrictionandthemoreendolymphmassarein thecanal,themorethefluidwilltendtolagbehind andthestrongerwillbetheforceactinguponthecupula. Thestiffnessofthecupulawill,however,preventalarge

deflection:withinmillisecondsanequilibriumwillbe reachedbetweentheinertialforceactinguponthecupula andtheelasticforcefromthecupula.Aslongasthe accelerationcontinues,thisequilibriumwillremain, resultinginapersistentdeflectionthatstimulatesthehair cellsinthecupula.Thestrongertheacceleration,the morethecupulawillbend:theconstantdeflectionof thecupulawillbeproportionaltotheacceleration. Lowcupulastiffness(highelasticity),highendolymph mass,andlowfrictionwillallresultinalargercupula deflection(highersensitivity).Whenconstantangular velocityisreached,thecupulawillstarttobendback toitsneutralpositionasthereisnodrivingforce(acceleration)anymoretomaintainthecupuladeflection. However,thereturnlastsquitelong,asnowtheelastic forceofthecupulaalonewillhavetomovetheendolymphmassagainstfriction.Alowcupulastiffness(high elasticity ¼ smallelasticforce),ahighendolymphmass, andstrongfrictionwillresultinaslowerreturnofthe cupulatoitsneutralposition.Inpathologyandaging, endolymphviscosity(friction)andcupulastiffnesscan change;inbenignparoxysmalpositionalvertigo (BPPV)thespecificmassoftheendolymphcanbe assumedtoincrease.Insummary:

1.increaseofcupulastiffnessorincreaseofendolymphviscosity:lowercanalsensitivityand shorterpostrotatorysensations

2.increaseofabsoluteendolymphmass:higher canalsensitivityandlongerpostrotatory sensations

3.changeofendolymphspecificmasscompared tothatofthecupula:sensitivityofthecanals forgravityandlinearaccelerationsisinduced.

Acanalisphysiologicallyinsensitiveto(coincidental) linearaccelerations(MelvillJones,1979)becausethe cupula andendolymphhavethesamedensity.Ifdifferencesindensitiesoccur,thecanaldynamicswillbe morecomplex,andwouldleadtoadependencyonthe orientationofboththegravityvectorrelativetothecanal planeandtheaxisofrotation,aswellasonthedistance betweentheaxisofrotationandthecenterofthesemicircularcanal(Kondrachuketal.,2008).Thiseffectisa familiar experienceafteralcoholintake,resultinginthe sensationofrotationwhenlyinginbed,andcaneven induceeyemovementsknownaspositionalalcohol nystagmus(Goldberg,1966).Thisisalsotheeffectexperienced inthecommonvestibulardisorderBPPV.In BPPV,otoconiaarepresentinthesemicircularcanals. Theseparticlesmakethesemicircularcanalsystemsensitivetotheorientationofgravityandcanadheretothe cupula – cupulolithiasis(Schuknecht,1962) – or remain free-floating,whichiscalledcanalithiasis(Rajguruetal., 2004, 2005).

Manyattemptshavebeenmadetodevelophighfrequencytests(vestibularautorotationtest,head shakers,high-frequency(hydraulic)torsionswingchair tests).Noneoftheseobtainedawidespreadapplication comparabletothecalorictestduetomanypractical limitations,andlimitedsensitivityandreproducibility. Passiveheadimpulsetests,fastsmall-amplitudehighvelocityheadrotations,canbeconsideredasevaluating thehigh-frequencyfunctionofthecanals,allowing quantificationofthegain,butnotbothtimeconstants. Thankstothedevelopmentofvideoeye-trackingdevices thatallowquantificationofheadandeyevelocityduring theseheadimpulses,headimpulsetestinghasbecome thefirstchoiceforquantificationofcanalfunctionathigh frequencies.Thecaloricteststillremainsavaluabletool toquantifythelow-frequencypartofcanalfunction.As canbeeasilyunderstoodfromthephysicsofthecanals, low-,middle-,andhigh-frequencylosscanoccur,bothin isolationandindifferentcombinations.

MULTISENSORYASPECTS

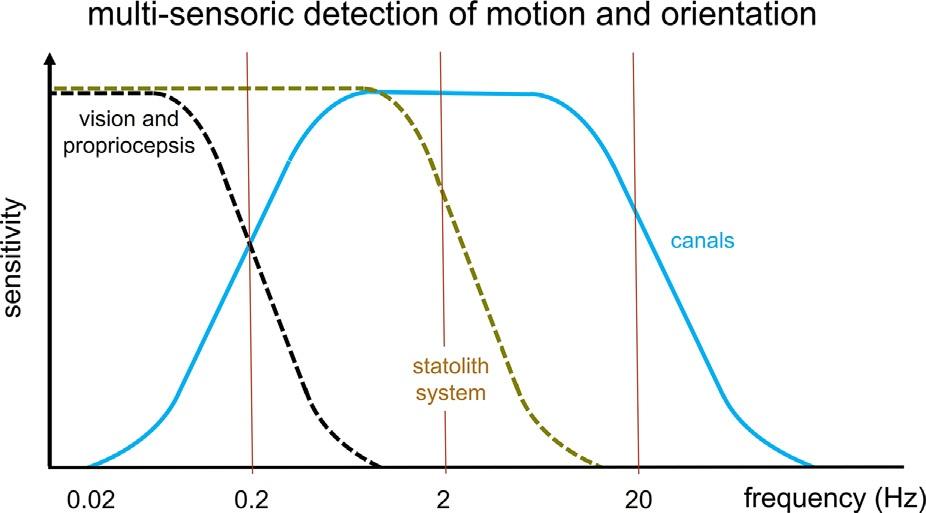

Canals,maculae,vision,andproprioceptionallcontributetomotionandtiltperception.Boththevisualand somatosensorysystemcanonlyprocessrelativelyslow bodymovements,andcanbemodeledwithalow-pass transferfunction,withacutofffrequencyofabout 0.2Hz.Theotolithorgansdetectlow-frequencylinear accelerations(translationsandtilt)uptoabout1Hz, whereasthesemicircularcanals(semicircularcanals) detectangularvelocitybetween0.1and10Hz.Based onthephysicsdescribedabovewecanestimatethefrequencydependenceofhumancanalsandstatolithorgans asdepictedin Figure1.21,butthereadershouldrealize thatthisisspeculationratherthanestimation.Atpresent

Fig.1.21. Graphicpresentationofthefrequencydependence ofcanalandstatolithfunction,incombinationwithpropriocepsionandvision.Motionsicknessisknowntooccuroften atmovementfrequenciesaround0.2Hz,wherethetransition occursfromdominanceofvisual-proprioceptiveinputversus thatofcanalinput.

itisnotpossibletoverifythesecurvesindetaildueto limitsofthediagnostictests,especiallybecauseitisstill notpossibletostimulateanyoneofthefivevestibular sensorsperlabyrinthseparately.Also,themagnitude ofthevestibularresponsesdependsonmanyfactors, includingcognitivefactors(alertness,instruction)and theprecisestimulusconditions(indarknessversusin thelight).Thevisualandsomatosensorysystemssupport theotolithorgansinthedetectionofconstantlinear accelerations(Vaugoyeauetal.,2008)andtiltperception atlowfrequencies,whereasthesemicircularcanalssupporttheotolithorganstodistinguishtruebodytiltfrom translationsatfrequenciesabove0.1Hz(Greenetal., 2005;Merfeldetal.,2005).Ifdifferentsensorysystems giveconflictingorinsufficientinformation,hindering thedeterminationofthedirectionofgravityordistinguishingcorrectlybetweenenvironmentalandselfmotion,motionsicknessisquitecommon(Blesetal., 1998),especiallyinindividualswithaneasilyactivated autonomicnervoussystem(neurovegetativesensitivity). Wealsoaddedthehypotheticfrequencysensitivityof proprioceptionandvision,whichcontributetomotion perceptionandorientationinthelow-frequencyrange.

PATHOLOGY

Losingsensorsformotionandtiltdetectionunavoidably leadstoalossoffunctionalityandcannotbecompensatedforbyothersensorysystemsthatdonothavesufficientsensitivityforthehigherfrequencies(Fig.1.15). Indeed,apermanentunilateralorbilateralperipheralloss leadstoapermanentreductionofautomaticimagestabilizationduringheadmovement(oscillopsia,reductionof dynamicvisualacuity),apermanentlossofautomatic balance(“nomoretalkingwhilewalking”)andapermanentlossofautomationofspatialorientation(feeling insecureinsituationswithstrongoptokineticstimuli,like busytrafficandsupermarkets).Thecontinuousand intenseextracognitiveloadneededforvision,balance, andorientationleadstofastfatigue,whichisamajor probleminpatientswithpermanentvestibulardeficits.

Adecreaseinvestibularsensitivitywithaging,presbyovestibulopathy,similartoperceptivehearingloss (presbyacusis)isamajorcauseofadecreaseofdynamic visualacuity,reducedbalance,andhighincidenceoffalls intheelderly.Besideshaircelldegeneration,agingmight alsoaffecttissuestiffnessandhydration,andthusalso affectsthevestibularphysicalquantitiesofboththesemicircularcanalsandotolithorgans:

1.anincreasingstiffness K increasesthelower cutofffrequency(K/B)anddecreasesthegain (I/K)belowthiscutofffrequency

2.anincreasingviscosity B decreasesthehigher cutofffrequency(B/I)anddecreasesthegain (I/B)belowthiscutofffrequency.

Theseeffectsareschematicallyshownin Figures1.16 and 1.17.Thevestibularsystemasawholeisthus affected aswell,reducingthedistinctionbetweentilt andtranslation,becausetheoptimalrangeofthesemicircularcanalsshiftstohigherfrequencies.Thisisparticularlyunfortunatebecausewithagebodymovements becomeslowerduetostifferbodymechanics.

CONSIDERATIONSCLINICALLY RELEVANTTOTHEIMPACTOF LABYRINTHINEFUNCTIONLOSS

Thevestibularlabyrinthsactasverysensitivesensorsof headaccelerationandtilt.Asexplainedabove,theutriculusandsacculuscanbeconsideredasveryrudimentary sensors,sensitiveforallmotionsandtilts,butnotableto discriminatebetweenthedifferenttypesofmotion. Dependingontheprecisemotionpattern,additional informationfromcanalsallowsdiscriminationbetween translations,centrifugations,andtilts.

Whenwelosecanalfunction,asmonitoredbythe calorictest,rotationaltest,andheadimpulsetests,we canstilldetectallmotionwiththestatolithsystem, althoughwithalowersensitivity,especiallyathigher frequencies.Whenwelosestatolithfunction,thefast intuitivedetectionofgravityandthesensitivityfortranslationswillbeimpaired,butrotationalsensitivitywillbe preserved.Oftenadistinctionismucheasierwhenadditionalvisualandproprioceptiveinformationisavailable. Adistinctionbetweenslowtiltsandtranslationsexplicitlyrequiresforeknowledgeaboutthetypeofmovement oradditionalinformationfromvisionand/orproprioception.Forexample,diversindarkwaterandpeoplecoveredbyanavalancheareunabletosensetheirorientation towardsgravity:thissuggeststhatthebrainisunableto detecttheorientationrelativetogravitywhencompletely deprivedofvisualorproprioceptiveinput,whichmaybe duetothisambiguityinthestatolithsystem.

Motionsicknessisconsideredtooccurespeciallyin conditionswhereweexperienceconflictsbetweenthe motion-sensitiveinputsignalstothebrainand/orwhen theperceivedverticaldiffersfromtheexpectedvertical. Subjectswithoutlabyrinthinefunctiondonotsufferfrom motionsickness.Interestingly,motionsicknesscanbe causedbystimulithatdonotactivatethelabyrinth,such asvisualillusionofmotion.Thiscanbeexplainedbythe factthatthecentralvestibularsystemisalwaysinvolved intheperceptionofself-motionandthedetectionofgravity, eveniftheinformationissuppliedbythevisualsystem.

Tosummarize,themajorfunctionsofthevestibular systeminrelationtoclinicalsymptomsare:

● Maintainingvisualacuityduringheadmotions: dynamicvisualacuitybymeansofthe vestibulo-ocularreflex.Vestibularfunctionloss mayleadtoapermanentlossofvisualacuityand oscillopsiaduringwalkingandheadmotion (oscillopsiaistheperceptionthattheimageis unstableontheretina).Especiallyduringwalking,verticalheadmovementsrequirecompensatoryeyemovements.Itisasyetunclearwhatthe precisecontributionofthestatolithandcanal systemsisforimagestabilizationasthehead movementsarecomposedoftranslational,rotational,andtiltcomponents.Thissuggeststhat thecorrelationbetweenalossofdynamicvisual acuitydependsonmanyfactors.Theoverall impactofa(frequency-dependent)labyrinthine lossforimagestabilizationneedsmoreresearch: patientsmightcompensateforthelossofimage stabilization(thevestibulo-ocularreflex)partly bysmallsaccades,so-calledcovertsaccades,or byimprovingtheabilityofthevisualsystemto analyzetheinformationpresentinmoving imagesontheretina,similartowhathasbeen suggestedincongenitalnystagmus.

● Allowingfastbalanceandposturalcorrectionsby anintuitiveperceptionofthegravityvectorand fastvestibulospinalreflexes.Sothespecificcontributionofthelabyrinthtobalancecontrolseems tobespeed.Severelabyrinthinelossmaythereforeleadtopermanentimbalance(walkinglike adrunkensailor),fearoffalling,andfalls.The impactofafunctionlossofthestatolithsystem maybeofgreaterrelevancethanlossofcanal function.However,weshouldstillbeawarethat thebrainneedsthecanalorothersensoryinputin additiontotheinherentlyambiguousotolithinput toallowareliabledetectionofthegravityvector.

● Spatialorientation:discriminationbetweenselfmotionandenvironmentalmotionandorientation relativetothegravityvector.Thelossoflabyrinthinefunctionmaythereforeleadtouncertainty. Thetrivialsensorysubstitutionthatisobserved inmanypatients,particularlywithregardto vision,canhaveadverseconsequencesasitmay leadtovisualdependenceandsometimesintolerancetomovingvisualstimuliorrepetitivepatterns withhighcontrasts(optokineticstimuli):oneof thepresentationsofso-calledvisualvertigo.

Asecondaryimpactofvestibularlossisalossofautomaticimagestabilization,balancecontrol,andspatial