1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Walden, Joshua S., 1979– author.

Title: Musical portraits : the composition of identity in contemporary and experimental music / Joshua S. Walden.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017020694 | ISBN 9780190653507 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190653521 (epub)

Subjects: LCSH: Characters and characteristics in music. | Music—20th century—History and criticism.

Classification: LCC ML197 .W36 2018 | DDC 781.5/9—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017020694

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

To Judy Schelly, Mike Walden, and Danny Walden

I drew men’s faces on my copy-books, Scrawled them within the antiphonary’s marge, Joined legs and arms to the long music-notes, Found eyes and nose and chin for A’s and B’s.

—Robert Browning, “Fra Lippo Lippi,” in Charlotte Porter and Helen A. Clarke (eds.), Poems of Robert Browning (New York: Thomas Y. Crowell, 1896), 127–8.

CONTENTS

List of Figures ix

List of Musical Examples xi

Acknowledgments xiii

Introduction: Portraiture as a Musical Genre 1

1. Musical and Literary Portraiture 22

2. Musical Portraits of Visual Artists 55

3. Listening in on Composers’ Self-Portraits 81

4. Celebrity, Music, and the Multimedia Portrait 109

Epilogue: Musical Portraiture, the Posthumous, and the Posthuman 143

Bibliography 161 Index 177

LIST OF FIGURES

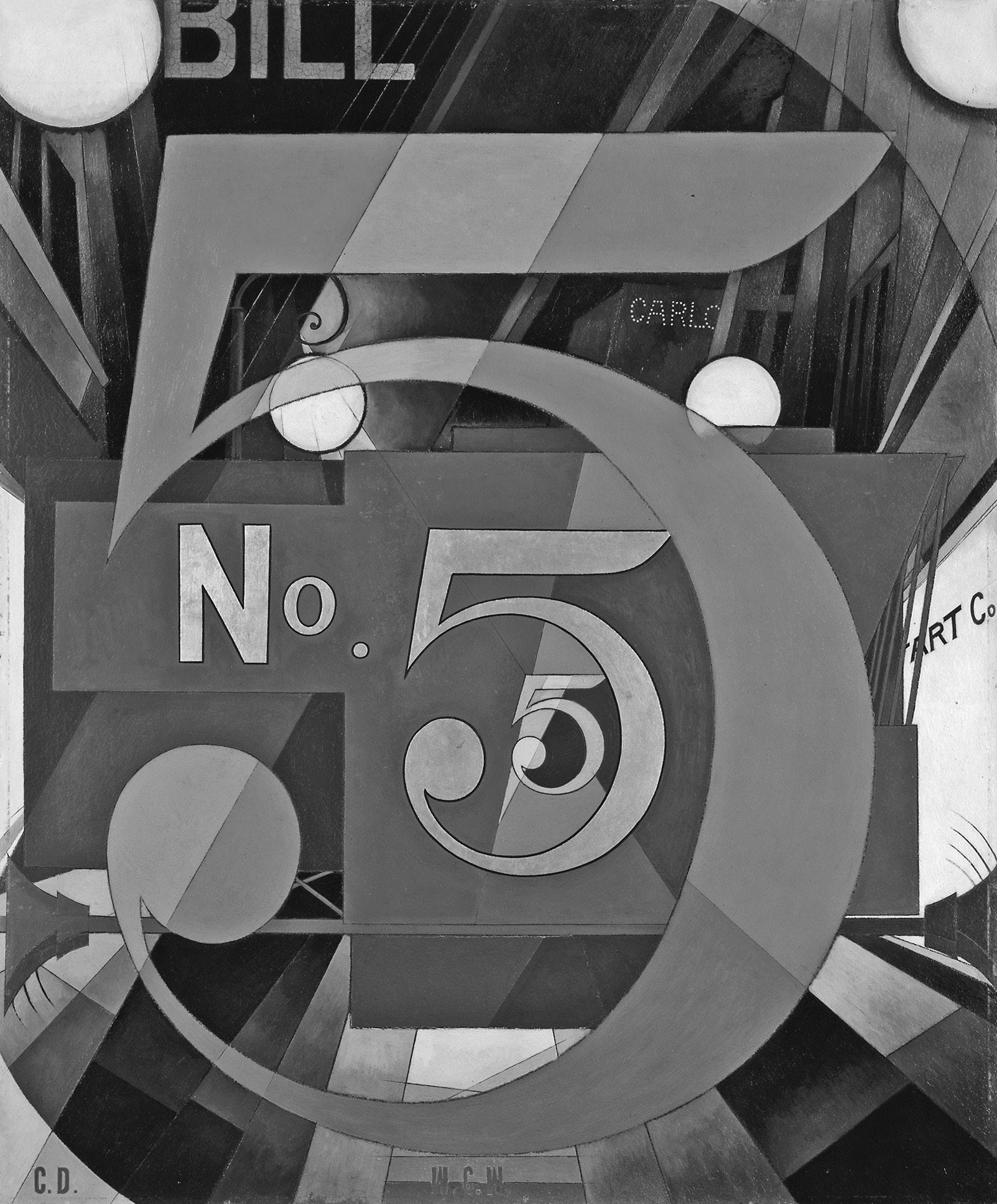

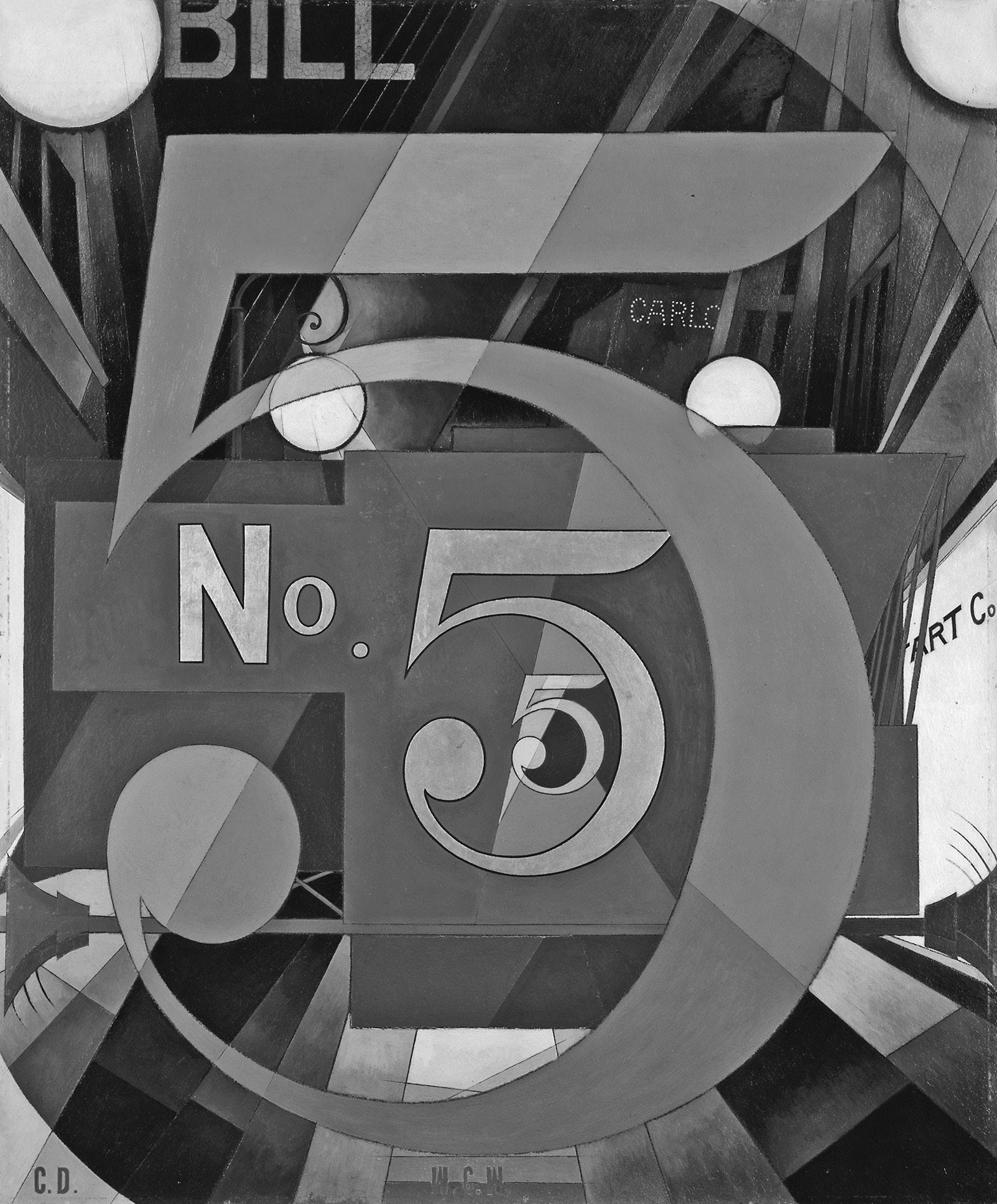

I.1 Charles Demuth, “The Figure 5 in Gold,” 1928, oil on cardboard, 35-1/2 x 30 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.59.1). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 7

I.2 Katherine Dreier, “Abstract Portrait of Marcel Duchamp,” 1918, oil on canvas, 18 x 32 inches. Museum of Modern Art. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/ Art Resource, NY. 8

1.1 Pablo Picasso, “Gertrude Stein,” 1905–1906, oil on canvas, 39-3/8 x 32 inches. © 2016 Estate of Pablo Picasso/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY. 27

1.2 Buffie Johnson, “Portrait of Virgil Thomson,” 1963, oil on Masonite, 23-3/4 x 19-1/2 inches. Used by permission of the University of Missouri-Kansas City Libraries, Dr. Kenneth J. LaBudde Department of Special Collections. Additional permission granted by Jenny J. Sykes. 33

2.1 Willem de Kooning, “Woman, I,” 1950–1952, oil on canvas, 6 feet 3-7/8 x 58 inches. © 2016 The Willem de Kooning Foundation/ Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY. 67

2.2 Chuck Close, “Phil,” 1969, acrylic on canvas, 108 x 84 inches.

© Chuck Close, courtesy Pace Gallery. 70

2.3 Chuck Close, “Phil,” 2011–2012, oil on canvas, 108-5/8 x 84 inches.

© Chuck Close, courtesy Pace Gallery. 73

3.1 Brother Rufillus, Initial R, from a Passionale from Weissenau Abbey, c. 1170–1200, Cod. Bodmer 127, f. 244r. Fondation Martin Bodmer, Cologny (Geneva). 82

3.2 Eugène Atget, “Coiffeur, Palais Royal,” 1927, albumen silver print (gold-toned), 7 x 9-1/2 inches. Museum of Modern Art. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY. 83

3.3 Richard Hamilton, “A Portrait of the Artist by Francis Bacon,” 1970–1971, collotype and screenprint, 32-3/8 x 27-3/8 inches. © R. Hamilton. All Rights Reserved, DACS and ARS 2016. Image copyright © The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image source: Art Resource, NY. 89

3.4 Kazimir Malevich, “Suprematism: Self-Portrait in Two Dimensions,” 1915, oil on canvas, 31-1/2 x 24-3/8 inches. Stedelijk Museum. Art Resource, NY. 92

3.5 John Baldessari, “Beethoven’s Trumpet (With Ear) Opus # 133,” 2007, foam, resin, aluminum, cold bronze, and electronics, 84 x 120 x 84 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery. 96

4.1 Robert Wilson and Tom Waits, “Robert Downey Jr.,” 2004, video. Courtesy RW Work Ltd. 117

4.2 Robert Wilson and Michael Galasso, “Winona Ryder,” 2004, video. Courtesy RW Work Ltd. 118

4.3

4.4

Robert Wilson and Philip Glass, “Knee Play 1” from Einstein on the Beach, 2012–2014 revival production. Courtesy of BAM Hamm

Archives and the Robert Wilson Archives and the Byrd Hoffman Water Mill Foundation. © Lucie Jansch. 132

Robert Wilson and Philip Glass, “Knee Play 5” from Einstein on the Beach, 2012–2014 revival production. Courtesy of BAM Hamm

Archives and the Robert Wilson Archives and the Byrd Hoffman Water Mill Foundation. © Lucie Jansch. 133

E.1 Kim Novak in Vertigo, directed by Alfred Hitchcock, Paramount Pictures, 1958. 145

E.2 Robert Wilson and Bernard Herrmann, “Princess Caroline,” 2006, video. Courtesy RW Work Ltd. 149

LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES

1.1 Virgil Thomson, “Miss Gertrude Stein as a Young Girl,” 1928, mm. 1–11. 31

1.2 Virgil Thomson, “Buffie Johnson: Drawing Virgil Thomson in Charcoal,” 1981, mm. 1–6. 34

1.3 Virgil Thomson, “Buffie Johnson: Drawing Virgil Thomson in Charcoal,” 1981, mm. 20–4. 34

2.1 Morton Feldman, “de Kooning,” first page. Copyright © 1963 by C. F. Peters Corporation. All Rights Reserved. Used by permission. 64

4.1 Philip Glass, “Knee Play 1,” from Einstein on the Beach, premiered 1976, organ 1 part, first measure. 132

4.2 Philip Glass, “Knee Play 2,” from Einstein on the Beach, premiered 1976, solo violin part, rehearsal 3. 132

E.1 Bernard Herrmann, Carlotta’s leitmotif, from Vertigo, 1958, dir. Alfred Hitchcock. David Cooper, Bernard Herrmann’s Vertigo: A Film Score Handbook (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2001), 20. 146

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am thankful to Alessandra Aquilanti, Andrea Bohlman, Christopher Doll, Walter Frisch, Sharon Levy, Michael Maul, Laura Protano-Biggs, Hollis Robbins, David Smooke, and Andrew Talle for the friendship and support they offered at various stages of my work on this project. This book received support from the Manfred Bukofzer Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. I want to acknowledge the insightful editorship of Suzanne Ryan and to thank Andrew Maillet, Victoria Kouznetsov, and the rest of the Oxford University Press staff who helped with the production of this book. Peering back further, I am grateful to the instructor who taught me the most about art and assured it would always be a source of fascination for me, Michele Metz. Whenever I visit a museum I still remember her lessons vividly as I come across the artworks she discussed in her class, and I am sure those lectures played no small part in the generation of this project. Most importantly, as always, the deepest thanks are owed to my family. The education I have received from my parents and brother in music, art, and literature has profoundly shaped the way I think about the world, and no one can be more helpful than they are, as interlocutors, sounding-boards, editors, and collaborators. It has been great fun to share this project with them.

Introduction

Portraiture as a Musical Genre

The artist’s work is to show us ourselves as we really are. Our minds are nothing but this knowledge of ourselves; and he who adds a jot to such knowledge creates new mind as surely as any woman creates new men.

George Bernard Shaw1

“Ahguarda, sorella,” sings the love-struck Fiordiligi to her sister Dorabella in the first act of Mozart and Da Ponte’s opera Così fan tutte (1790). In a lilting, circling melody, she repeats, “Guarda, guarda”—“Look, look.” Both sisters wear portrait miniatures of their beaux about their necks. Fiordiligi gazes admiringly at the portrait of her beloved Guglielmo, but convincing her sister to look will mean distracting the impulsive Dorabella from the miniature portrait of Ferrando over which she is swooning. Fiordiligi doubts one can find a finer mouth or nobler countenance than those depicted in the portrait she beholds: she sees “the face of a soldier and a lover.” This characterization comes across in the orchestral accompaniment as well, his strength in the dotted rhythms rising in a major arpeggio, his amorousness in the suddenly languorous and melismatic singing style that follows. For her part, Dorabella is preoccupied by the depiction of her lover’s eyes, which seem to shoot flames and darts at her. She sees in her portrait “a face attractive but forbidding,” characteristics conveyed musically by the sudden change to minor and the ensuing anxious motivic repetition, an aroused turn to the Sturm und Drang style.

Portraiture depicts aspects of our selves that are available to the senses, but it also proposes elements of our reality that we might not otherwise recognize so readily. It can reveal features of the human self that are hidden

beyond plain view, but it can additionally convince us of attributes of identity that are pure fabrication. If the opera had opened with this duet, we might be persuaded that the portraits tell the truth about the subjects they depict, or at least that these young women’s interpretations of what they see in their miniatures can be believed. But we met the young men they describe during the previous scene, in which, drunk and impetuous, they argued over which of them inspired the more intense devotion in his lover, and devised a plan to test Fiordiligi and Dorabella’s constancy by dressing as Albanians and trying to seduce one another’s sweethearts. Can these be the strong and reputable youths whose respective noble face and fiery eyes are depicted in their portraits?

The young women’s duet derives its ironic depiction of loving idolization from the friction between perception and truth, symbolized simply but potently by the unreliability of portraits and the pitfalls of believing in the accuracy of their representations. The sisters’ vocal lines also reveal music’s ability to conjure aspects of character, bearing, and social status in a way that reflects the representational power of visual art: Mozart’s text setting and instrumental writing during this number mirror the portraits’ images as described by the two young women, evoking the series of affects about which they sing through the juxtaposition of musical gestures, textures, and topics. One can almost picture in the imagination the miniatures the women gaze at through the descriptions presented in the poetry and music. This operatic scene demonstrates how music, in combination with language, can be devised to fashion an impression of human identity. Like the miniatures that hang from the necks of Fiordiligi and Dorabella, Mozart’s musical portrayal of their lovers employs well-known sonic tropes that serve as metaphors to depict qualities of respectability, moral strength, and maturity that both the young men and the young women would like to believe reflect the truth about their characters. But members of the audience—along with the philosopher Don Alfonso and the maid Despina, the characters who join together to put the couples’ affection through a series of trials over the course of the narrative—know these musical and poetic interpretations of the miniature portraits to be exaggerated and false. To recognize the music as ironic, we have to see the conflict between the way the men are represented in the first scene and the musical construction of their identities here. In this manner Mozart’s opera shows that the representations of individuals that emerge from the mixture of sound and words must always be viewed as subjective constructions rather than objective mirrors of reality.

This book is about musical portraiture, a genre of compositions that operate as musical evocations of aspects of individual identities in the manner of portraits in the visual arts and literature. Musical portraits have been

written in a variety of forms, from the eighteenth-century keyboard miniature to the twentieth-century portrait opera and beyond. With no other definitive distinguishing features, such works require the aid of a title or other manner of description by the composer in order to be identified as portraits. The genre emerged in the early 1700s with works by François Couperin (1668–1733) and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach (1714–1788) and has remained of interest to composers through the present day, as a means of creating sonic depictions of patrons, family members, friends, and historical figures.2

Portraiture in music has proven a more complex and even elusive enterprise than portraiture in painting or sculpture, for obvious reasons: in the absence of a means of depicting physical appearance, an element of portraiture in the visual arts that is commonly considered essential, composers have grappled with the question of how music can convey attributes of identity other than appearance in such a way that listeners will construe the composition to represent an individual. The musical portrait invites interpretation, as the listener, inspired by the composition, constructs in the imagination an impression of the work’s human subject. Musical portraiture therefore evinces a particularly self-conscious, interactive form of representation, in which a piece’s sounds and structures, in conjunction with a title identifying it as a portrait, are assembled by the composer and performer and heard by the listener to evoke abstract attributes of identity such as character, personality, social status, and profession.

The second half of the twentieth century and the start of the twenty-first have brought compelling developments to the genre of visual portraiture, as Western conceptions of identity have altered in parallel with increasing challenges to the predominance of mimesis in artistic representation. This book investigates the ways such recent debates over the nature of the self inform our understanding of music’s capacity to represent human identity by considering works of musical portraiture composed since 1950. Indeed, while composers have created musical portraits with some regularity since the early development of the genre, the contemporary focus in the arts on challenging traditional modes of representation has provoked increasing numbers of composers to experiment with the representation of personal identity in music and in multimedia combinations of sound, text, and image.

The subjects of the musical portraits examined in this book are principally artists in the fields of literature, painting, composition, and performance. By looking in particular at musical portraits of authors and artists as well as composers’ self-portraits, the case studies in each chapter explore the complex relationships among musical, visual, and linguistic modes of depicting human identity. This introduction offers a brief history

of visual and musical portraiture and a discussion of modes of representation in music. It then examines how the musical portrait operates as a narrative construction of an identity or self. Finally, it closes with an overview of the structure of this book’s exploration of contemporary musical portraiture.

LIKENESS, IDENTITY, AND METAPHOR IN PORTRAITURE

Portraiture in the visual arts typically assumes the representation of physical likeness, the fixing for posterity of a person’s appearance in a single moment of life. Highlighting this function of the genre, the early modern art theorist Leon Battista Alberti wrote in his 1435 treatise On Painting: “Painting contains a divine force which not only makes absent men present . . . but moreover makes the dead seem almost alive. . . . Thus the face of a man who is already dead certainly lives a long life through painting.”3 The notion of the portrait as fixing a life in spite of human mortality is the focus of the 1850 short story “The Oval Portrait” by Edgar Allan Poe, which describes the creation of a portrait of a lively young woman that hangs on the wall of an abandoned chateau. The woman had fallen in love with the painter, whose devotion to his craft so distracts him that over the course of sitting for the portrait she becomes increasingly jealous of his attentions. After completing his last brush stroke and standing back to look at the finished portrait, the artist “grew tremulous and very pallid, and aghast, and crying with a loud voice,” he exclaimed, “This is indeed Life itself!” He then turns to discover, to his horror, that as he painted her portrait, his beloved has died.4 The artist who preserves a life for posterity, in Poe’s imagination, and in a reversal of the dynamic Alberti describes, renders that life absent in the present.5

Artists and critics have long remarked that the representation that captures an individual life in portraiture for eternity requires more than simply the reproduction of physical likeness: the portrait must convey a sense of a sitter’s character, understood to include such aspects as personality, social position, and profession.6 Thus even in the ancient world, the Greek historian Plutarch praised Lysippos—the artist of the fourth century bce known as the “father of Hellenistic sculpture” for his bronze representations of Alexander the Great that combined physical idealization with the depiction of their subject’s individuality— for bronzes that “preserve [Alexander’s] manly and leonine quality” and in so doing “brought out his real character . . . and gave form to his essential excellence.” 7

Identity is thus viewed as related to but not defined by the body; as the analytic philosopher Bernard Williams puts it, “Identity of body is at least not a sufficient condition of personal identity.”8 The successful portrait exceeds the mere representation of the body: it allows the viewer to infer a broader and multidimensional conception of the invisible aspects of the sitter’s subjectivity. As Paul Klee wrote of his portraiture in his diary in 1901, “I am not here to reflect the surface . . . but must penetrate inside. My mirror probes down to the heart. . . . My human faces are truer than the real ones.”9

The use of portraiture to represent interior identity rather than simply to mimic external appearance can be understood as a form of aesthetic realism, even as it involves the development of techniques for depicting something invisible to the eye. Indeed, a portrait that fails to define the sitter’s character is likely to be criticized as untruthful or incomplete, no matter how precise its likeness. In her first novel, Adam Bede (1859, rev. 1861), George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) sets forth her conception of the importance of creating portraits of characters in all their complexity: she imagines a hypothetical reader asking why she has represented her characters as flawed individuals, and responds by explaining that her task is not to idealize “life and character entirely after my own liking,” but “to give a faithful account of men and things as they have mirrored themselves in my mind.”10

To describe this literary technique she raises the analogy of paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, with their focus on the realistic depiction of the appearance, character, and daily activities of the working classes. Though she does not call for the wholesale rejection of “the divine beauty of form,” she writes,

But let us love that other beauty too, which lies in no secret of proportion, but in the secret of deep human sympathy. Paint us an angel, if you can, with a floating violet robe, and a face paled by the celestial light . . . but do not impose on us any aesthetic rules which shall banish from the region of Art those old women scraping carrots with their work-worn hands, those heavy clowns taking holiday in a dingy pot-house, those rounded backs and stupid weather-beaten faces that have bent over the spade and done the rough work of the rough curs, and their clusters of onions. . . . It is so needful we should remember their existence, else we may happen to leave them quite out of our religion and philosophy, and frame lofty theories which only fit a world of extremes. Therefore let Art always remind us of them.11

In this passage, Eliot proposes that the artist has an ethical responsibility to represent the faces of ordinary people, and to do so in a way that favors the truthful depiction of interior life over the idealization of external appearance.

Eliot makes this distinction with regard to literature and painting, but it informs our study of portraiture in music as well, and in many of the portraits examined in the following three chapters of this book, composers explore ways to represent in music, without idealization, the interior lives of their subjects.12 The fourth chapter, on the other hand, views the influence of visual idealization, as found in images of military and political leaders and in celebrity and fashion photography, on contemporary portraiture in musical multimedia.

Taking to its extreme this notion of portraiture as the art of depicting a person’s internal character, a number of artists in the early twentieth century began to experiment with the elimination of literal likeness in portraiture, developing innovative methods of representing individuals without relying on realistic visual mimesis, and thus expanding and challenging the traditional boundaries implied by standard definitions of the genre.13 For example, Pablo Picasso engaged the techniques of cubism to deconstruct his sitters’ bodies, and Francis Bacon painted images of sitters with their faces and bodies contorted, often beyond recognition. Charles Demuth’s portrait of William Carlos Williams titled “The Figure 5 in Gold” (1928) depicts words and images from Williams’s poetry rather than a likeness of his face to represent his identity (Figure I.1), while Katherine Dreier’s “Abstract Portrait of Marcel Duchamp” (1918) abandons pictorialism altogether to offer an abstract, fragmented representation of her subject (Figure I.2).14 In these works portraiture becomes a sort of game, in which the viewer is invited to interpret the relationship between various symbolic or abstract elements of the image and the named subject it is said to represent.15

Such developments in portraiture in the visual arts provide a model for describing how composers have experimented with depicting human subjects through music. In a manner reflective of cubism and other abstract modes of painting, composers of musical portraits have represented their sitters through musical elements such as form, rhythm, harmony, and style. Where portrait painters rely on visual art’s stasis to fix a moment for posterity, however, composers of musical portraits often take advantage of the temporal aspect of their medium as well. This allows them to create portraits that render their subjects’ character and life experiences from various perspectives and unfolding through time— for example by using narrative techniques to portray events in their subjects’ biographies, or evoking a succession of affects to convey the development of character. The musical portraits of artists known for their work in various media that are discussed in this book also depict the subjects identified in their titles by suggesting affinities with qualities of their own works of portraiture in the visual arts, literature, and

music. These portraits call attention to analogies between musical and other aesthetic means of representation, especially through metaphors that associate what we hear with what we see.

In all artistic media, portraiture is a genre that relies inherently on metaphor. Until the more recent era of abstraction in visual portraiture, works in the genre, including those that idealize their sitters’ likenesses, have traditionally depended on the standard metaphor that the body is a container for whatever one believes it is that makes an individual unique—the soul, the self, character, personality, identity, or some other entity. As Richard

Figure I.1: Charles Demuth, “The Figure 5 in Gold,” 1928, oil on cardboard, 35-1/2 x 30 inches. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Alfred Stieglitz Collection, 1949 (49.59.1). Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Figure I.2: Katherine Dreier, “Abstract Portrait of Marcel Duchamp,” 1918, oil on canvas, 18 x 32 inches. Museum of Modern Art. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

Leppert writes, “Challenged to make identity visible . . . portraits must ‘employ’ the physical body as the proving ground of the soul, since the body is the only available terrain onto which the nonphysical can be visualized.”16 Wittgenstein suggests a similar point in his aphorism, “The human body is the best picture of the human soul.”17 According to this understanding, portraits represent “outer” attributes of physical appearance such as facial expression, posture, gesture, and physical bearing as signs of invisible “inner” aspects of identity.

The notion that the appearance of the body offers a representation of what lies “on the inside” has been long-standing in the discourse about portraiture. In a passage from The Memorabilia (fourth century bce), Xenophon recounts Socrates’s lesson to a sculptor: “Must not the threatening look in the eyes of fighters be accurately represented, and the triumphant expression on the face of conquerors be imitated? . . . It follows, then, that the sculptor must represent in his figures the activities of the soul.”18 In the late seventeenth century, the influential artist and art theorist Charles le Brun, who held the title of Premier Peintre du Roi at the court of Louis XIV, explains his view that facial expression (in the words of a 1701 translation) “is that which describes the true Characters of Things. . . . The external Characters, are certain Signs of the Affections of the Soul; so that by the Form of every Creature may be known its Humours and Temper.”19 In his 1753 treatise The Analysis of Beauty, William Hogarth, acknowledging his debt to le Brun, similarly writes, “It is by the natural and unaffected movements of the muscles, caused by the passions of the mind, that every man’s character would in some measure be written in his face.”20 The visible quality

of facial expression, according to le Brun and Hogarth, makes apparent the combination of passions that combine to form a person’s internal self.21 Even as notions of what constitutes the self—the passions, the humors, character, inherent qualities, or constructed elements of identity—have changed over the centuries, this basic premise has remained largely intact.

The metaphorical power of portraiture to dissect the body, to investigate its external aspects to find the self that lies underneath the surface, can be a source of self-consciousness and anxiety for the sitter. Susan Sontag writes that in posing for photographs she experiences the distance between body and soul, the space between her physical appearance and her interior self, especially acutely: “Immobilized for the camera’s scrutiny, I feel the weight of my facial mask, the jut and fleshiness of my lips, the spread of my nostrils, the unruliness of my hair. I experience myself as behind my face, looking through the windows of my eyes, like the prisoner in the iron mask in Dumas’s novel.”22

But it is also precisely because identity is thought to reside beneath the surface, mapped onto but also hidden by the outward, visible aspect of the individual, that portraiture can operate without conveying physical likeness at all. Although musical portraits, as well as abstract visual portraits of the twentieth century such as Demuth’s painting of Williams and Dreier’s of Duchamp, do not depict physical likeness, they still rely on the metaphoric conception of an individual’s identity as interior, available to the senses through artistic representation and interpretation.

Metaphors factor heavily in the ways music, like identity, is described in Western cultures, and these metaphors are typically brought into play in musical portraiture’s representations. Music is often conceptualized metaphorically through reference to qualities associated with physical movement, language, the visual, and other domains of human experience. 23 More than simply descriptive tropes or figures of speech, such metaphors are defining concepts in cultural modes of understanding music, and contribute to how sound is perceived in relation to other aspects of aesthetic contemplation, physical and social experience, and cultural notions of one’s place in the world.24 In the musical portrait, the metaphorical concepts that govern the understanding of both the human individual and the musical work interact and combine. For example, the twin metaphors of the piece of music as a container for the composer’s ideas and the body as a container for the self overlap in the case of the musical portrait, so that the expressive and emotional content of the composition are understood to depict the corresponding attributes of the person being represented. In this way, for instance, the structure of the piece may be used to outline ordered aspects of the subject’s

biography, in a manner that depends in part on the metaphors of both music and life as types of narrative.

The metaphors that help form the understanding of music by relating it to visual art also play an important role in the depiction of the musical portrait’s subject. Though arguably those musical elements typically characterized as “lines,” “shapes,” “colors,” and “textures” are rarely combined in the imagination into anything resembling physical likeness, they can map onto the way we employ visual metaphors in understanding human character as embodying varying degrees of color, vibrancy, darkness, hard and soft edges, and so forth. For example, a piece described as colorful— perhaps because it incorporates a variety of contrasting timbral or “tone color” effects—might be understood to convey a portrait subject’s “colorful” personality.

Paying critical attention to the connections we make between sound and sight helps to reveal what Simon Shaw-Miller calls the “close and porous mutual surfaces” between musical and visual art forms that are too often treated as entirely distinct.25 Adapting philosopher Jerrold Levinson’s approach, in the essay “Hybrid Art Forms” (1984), to works of art that correlate different media types through processes of juxtaposition, synthesis, and transformation, Shaw-Miller proposes the study of the hybrid arts as a way to reveal the rich interactions between music and the visual.26 Indeed, the appreciation of music often entails a visual dimension, one that involves the image of the human body, particularly that of the performer. Leppert explains, “Whatever else music is ‘about,’ it is inevitably about the body; music’s aural and visual presence constitutes both a relation to and a representation of the body.”27 Because many listeners are conditioned to associate the sounds of music with the appearance—present or imagined—of the body of the performer, and with human form and movement more generally, music operates particularly effectively as a medium in the construction of individual identities in portraiture, even if it is incapable of reproducing detailed physical likeness.28

Of course viewing art, like listening to music, also brings us in touch with the human body; while the sonic and visual arts are distinct in many fundamental ways, physical and psychological aspects of perception in both fields also overlap. In particular, although it may seem intuitive to describe music as temporal and gestural and visual art as static in time and space, the appreciation of visual art, like the experience of music, in fact also involves physical movement and gesture, as we reposition ourselves before an artwork to see it from different angles, move our eyes across its surface, and experience it in time, shifting our perspective from one area to another to observe different aspects of the image’s construction and narrative.29 Furthermore, we might infer from brush strokes and other elements of the canvas the

motions that were made by the artist during the creation of the painting, much as we interpret the physical gestures of musicians when attending a performance or imagine them when listening to a recording, and such perception of the artist’s movements in any medium can influence the interpretation of the content and subject of the work.30

CONSTRUCTING THE CONTEMPORARY SELF IN MUSIC

The philosopher Jerrold Seigel writes that the Western conception of the self consists of three principal components: the bodily, or physical existence; the relational, deriving from social interaction and cultural contexts; and the reflective, the capacity to examine and question oneself.31 Of course, conceptions of what constitutes these three aspects of human identity have varied considerably over time, and conventions in both visual and musical portraiture have developed in parallel. According to the modern view, whose origins are found in the Renaissance, the self entails a coherent entity associated with notions of autonomy and free will; it is this isolated self that characterizes people as separate individuals with unique identities.32 With the postwar perspectives introduced by deconstructionist critique and the new understandings of identity developed by proponents of postcolonialism, gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race, and other modern schools of thought, the self came generally to be recognized as fragmented and mutable, and as formed discursively through social interaction, rather than unified and fixed at a single point of emergence.33 Madan Sarup writes, “Identity in postmodern thought is not a thing; the self is necessarily incomplete, unfinished—it is ‘the subject in process.’ ”34

If the self is constructed, it is also performed and interpreted: individuals adopt certain actions in public that will express corresponding aspects of character, and onlookers interpret these behaviors to combine in the impression of an identity.35 In portraiture, the artist constructs an identity on the canvas, generally by representing physical appearance, but the subject posing for the image may also play a role in this construction through an act of performance that aims to depict the self. Roland Barthes describes his behavior when he is photographed as involving a self-conscious sort of performance:

I decide to “let drift” over my lips and in my eyes a faint smile which I mean to be “indefinable,” in which I might suggest, along with the qualities of my nature, my amused consciousness of the whole photographic ritual: I lend myself to the social game, I pose,