MOVEMENT DISORDERSIN CHILDHOOD

THIRDEDITION

HARVEY S.SINGER

JohnsHopkinsUniversitySchoolofMedicine,DepartmentofNeurology,andtheKennedyKriegerInstitute, Baltimore,MD,UnitedStates

JONATHAN W.MINK

UniversityofRochesterMedicalCenter,DepartmentofNeurology,DivisionofChildNeurology,Rochester, NY,UnitedStates

DONALD L.GILBERT

DivisionofNeurology,CincinnatiChildren’sHospitalMedicalCenter;DepartmentofPediatrics, UniversityofCincinnati,Cincinnati,OH,UnitedStates

JOSEPH JANKOVIC

Parkinson’sDiseaseCenterandMovementDisordersClinic,DepartmentofNeurology,BaylorCollegeofMedicine, Houston,TX,UnitedStates

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier 125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom

Copyright © 2022ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearance CenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher (otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthis fieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroaden ourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationor methodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhom theyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeanyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceor otherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthe materialherein.

ISBN:978-0-12-820552-5

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublicationsvisitour websiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: NikkiLevy

AcquisitionsEditor: JoslynChaiprasert-Paguio

EditorialProjectManager: KristiAnderson

ProductionProjectManager: SelvarajRaviraj

CoverDesigner: MattLimbert

CoverImage: “BoysAfflictedwithChoreaKnown” , usedwithpermissionfromHistoria/Shutterstock.

TypesetbyTNQTechnologies

Prefaceix

SectionI

Overview

1.BasalGangliaAnatomy,Biochemistry, andPhysiology

Introduction4 BasalGangliaCircuits,CellTypes,and Compartments4

Neurotransmitters6

OtherBasalGangliaNuclei7

InhibitingandDisinhibitingMotorPatterns9 ImplicationsforDisease:FocalLesionsand AbnormalMovements10 References11

2.CerebellarAnatomy,Biochemistry, Physiology,andPlasticity

IntroductionandOverview16

OverviewofCerebellarStructure,Function,and SymptomLocalization16

CerebellarIntegrationwithBasalGanglia Circuits23

NeurotransmittersintheCerebellum26

NeuroplasticityintheCerebellum28 Conclusion30

References30

3.Classi ficationofMovementDisorders

Introduction33 Ataxia36 Athetosis36 Ballismus36 Chorea37

Dystonia37 Myoclonus38 Parkinsonism39 Startle39

Stereotypies39 Tics40 Tremor41 MixedMovementDisorders41

AtypicalMovementDisorders41 References42

4.DiagnosticEvaluationofChildrenWith MovementDisorders

Introduction44 Preclinic46 InClinic48

TheDiagnosis57 Summary64

References65

5.MotorAssessments

Introduction70

QuantitativeMeasurementinMovement Disorders70

RatingScalesforPediatricMovement Disorders72 References77

SectionII DevelopmentalMovementDisorders

6.TransientandDevelopmental MovementDisorders

Introduction85 References93

SectionIII

ParoxysmalMovementDisorders

7.TicsandTouretteSyndrome

Introduction100

DefinitionofTics101

ClinicalCharacteristics Phenomenologyand ClassificationofTics101

LocalizationandPathophysiology102

SpecificTicDisorderDiagnoses112

Treatment119

References126

8.MotorStereotypies

IntroductionandOverview142

Definitions142

ClinicalCharacteristics,Classi fications,and Differentiation142

Pathophysiology146

MajorDiseasesandDisorders151

StereotypyRatingScales157

Treatment157

References158

9.ParoxysmalDyskinesias

IntroductionandOverview165

ClinicalCharacteristics166 DiseasesandDisorders168

References176

SectionIV

HyperkineticandHypokinetic MovementDisorders

10.Chorea,Athetosis,andBallism

IntroductionandOverview184

DefinitionsofChorea,Athetosis,and Ballism184

ClinicalCharacteristics PhenomenologyofChorea, Athetosis,andBallisminChildren185

LocalizationandPathophysiology187

DiseasesandDisorders189

SummaryofDiagnosticandTherapeutic Approach217

References218

11.Dystonia

IntroductionandOverview230

ClassificationofDystonias231

LocalizationandPathophysiology238

DiseasesandDisorders239

DiagnosticApproachtoDystonia250

ManagementandTreatment251

PatientandFamilyResources253

References253

12.Myoclonus

IntroductionandOverview264

DefinitionofMyoclonus265

ClinicalCharacteristics Phenomenologyof MyoclonusinChildren265

LocalizationandNeurophysiology268

DiseasesandDisorders270

SummaryofDiagnosticandTherapeutic Approach295

References296

13.Tremor

IntroductionandOverview306

DefinitionofTremor306

ClinicalCharacteristics Phenomenologyand ClassificationofTremorinChildren307

LocalizationandPathophysiology310

DiseasesandDisorders314

ApproachtoDiagnosisandManagement324

References325

14.Ataxia

IntroductionandOverview334

DefinitionofAtaxia335

ClinicalCharacteristics PhenomenologyofAtaxia inChildren335

LocalizationandPathophysiology336

DiseasesandDisorders336

ApproachtoDiagnosisandManagement379

References382

15.Parkinsonism

IntroductionandOverview396

ClinicalFeaturesofParkinsonism396 PathophysiogyofParkinsonism397 DiseasesandDisorders399

TreatmentofParkinsonism407 References408

16.HereditarySpasticParaplegia

IntroductionandOverview416

DefinitionsofSpasticityand Hypertonia417

ClinicalCharacteristics PhenomenologyofSpastic ParaplegiainChildren417

LocalizationandPathophysiology419 DiseasesandDisorders420

ApproachtoDiagnosisand Management433 Summary435

References435

SectionV

SelectedSecondaryMovement Disorders

17.MetabolicDisordersWithAssociated MovementAbnormalities

PediatricNeurotransmitter Disorders445

StorageDisorders456 Leukodystrophies474 Aminoacidemias475 OrganicAcidemias479

Glycolysis,PyruvateMetabolism,andKrebsCycle Disorders484

MitochondrialDisorders488 PurineMetabolismDisorders493

CreatineMetabolismDisorders497

CongenitalDisordersofGlycosylation499

Cofactor,Mineral,andVitamin Disorders500

NeuroacanthocytosisSyndromes503

OtherMetabolicConditions506 References508

18.MovementDisordersinAutoimmune Diseases

Introduction536 ImmunologyOverview536 DiseasesandDisorders537

References552

19.MovementDisordersinSleep

Introduction562

OverviewofSleepPhysiology563

Sleep-RelatedMovementDisorders565 HyperkineticMovementDisordersthatArePresent DuringtheDaytimeandPersistDuring Sleep580

SeizuresinandAroundtheTimeofSleep580 References581

20.CerebralPalsy

Introduction592 Epidemiology593 Etiology593 Diagnosis595

HistoryandPhysicalExamination595 AssessmentScales596

CluesforDeterminingtheMotorCPType597 CerebralPalsySyndromes598 Management606 References610

21.MovementDisordersand NeuropsychiatricConditions

IntroductionandOverview620

AttentionDeficitHyperactivityDisorder621

ObsessiveCompulsiveDisorder623 AutismSpectrumDisorder625

Conclusions629 References629

22.Drug-InducedMovementDisorders inChildren

IntroductionandOverview638

DefinitionofDrug-InducedMovement Disorders639

ClinicalCharacteristics Phenomenologyof Drug-InducedMovementDisordersin Children639

Drug-InducedMovementDisorders640

Conclusion658

References658

23.FunctionalMovementDisorders

Introductions667 Epidemiology668

ClinicalFeaturesofFunctionalMovement Disorders670 Pathophysiology670 Diagnosis671

Conclusion676 References676

AppendixADrugAppendix681

AppendixBSearchStrategyforGenetic MovementDisorders705

Index713

BasalGangliaAnatomy, Biochemistry,andPhysiology

HarveyS.Singer1,JonathanW.Mink2, DonaldL.Gilbert3 andJosephJankovic4 1DepartmentofNeurology,JohnsHopkinsHospitalandtheKennedyKriegerInstitute, Baltimore,MD,UnitedStates; 2DivisionofChildNeurology,UniversityofRochesterMedical Center,Rochester,NY,UnitedStates; 3DivisionofNeurology,CincinnatiChildren’sHospital MedicalCenter,Cincinnati,OH,UnitedStates; 4DepartmentofNeurology,BaylorCollegeof Medicine,Houston,TX,UnitedStates

Introduction

Thebasalgangliaarelargesubcorticalstructurescomprisingseveralinterconnectednuclei intheforebrain,diencephalon,andmidbrain.Historically,thebasalgangliahavebeen viewedasacomponentofthemotorsystem.However,thereisnowsubstantialevidence thatthebasalgangliainteractwithalloffrontalcortexandwiththelimbicsystem.Thus, thebasalganglialikelyhavearoleincognitiveandemotionalfunctioninadditiontotheir roleinmotorcontrol.1 Indeed,mostdiseasesofthebasalgangliacauseacombinationof movement,affective,andcognitivedisorderswiththemovementdisorderbeingpredominant.Themotorcircuitsofthebasalgangliaarebetterunderstoodthantheothercircuits, butbecauseofsimilarorganizationofthecircuitry,conceptualunderstandingofbasal gangliamotorfunctioncanprovideausefulframeworkforunderstandingcognitiveandaffectivefunction,too.

BasalGangliaCircuits,CellTypes,andCompartments

Circuits

Thebasalgangliaincludethestriatum(caudate,putamen,nucleusaccumbens),thesubthalamicnucleus(STN),theglobuspallidus(internalsegment GPi,externalsegment GPe, ventralpallidum VP),andthesubstantianigra(parscompacta SNpcandparsreticulata SNpr)(Fig.1.1).ThestriatumandSTNreceivethemajorityofinputsfromoutsideofthebasal ganglia.Mostofthoseinputscomefromcerebralcortex,butthalamicnucleialsoprovide stronginputstostriatum.Thebulkoftheoutputsfromthebasalgangliaarisefromthe globuspallidusinternalsegment,VP,andsubstantianigraparsreticulata.Theseoutputs areinhibitorytothepedunculopontineareainthebrainstemandtothalamicnucleithatin turnprojecttofrontallobe.

Thestriatumreceivesthebulkofextrinsicinputtothebasalganglia.Thestriatum receivesexcitatoryinputfromvirtuallyallofcerebralcortex.2 Inaddition,theventralstriatum(nucleusaccumbensandrostroventralextensionsofcaudateandputamen)receivesinputsfromhippocampusandamygdala.3 Thecorticalinputusesglutamateasits neurotransmitterandterminateslargelyontheheadsofthedendriticspinesofmedium spinyneurons.4 Theprojectionfromthecerebralcortextostriatumhasaroughlytopographicorganizationthatprovidesthebasisforanorganizationoffunctionallydifferent circuitsinthebasalganglia. 5, 6 Althoughthetopographyimpliesacertaindegreeofparallel organization,thereisalsoevidenceforconvergenceanddivergencei nthecorticostriatal projection.Thelargedendritic fi eldsofmediumspinyneurons7 allowthemtoreceiveinput fromadjacentprojections,whicharisefromdifferentareasofcortex.Inputstostriatumfrom severalfunctionallyrelatedcorticalareasoverlapandasinglecorticalareaprojectsdivergentlytomultiplestriatalzones.8 ,9 Thus,thereisamultiplyconvergentanddivergentorganizationwithinabroaderframeworkoffun ctionallydifferentparallelcircuits.This organizationprovidesananatomicalframewor kfortheintegrationandtransformationof corticalinformationinthestriatum. 1.BasalGangliaAnatomy,Biochemistry,andPhysiology

FIGURE1.1 Simplifiedschematicdiagramofbasalganglia thalamo-corticalcircuitry.Excitatoryconnections areindicatedby openarrows,inhibitoryconnectionsby filledarrows.Themodulatorydopamineprojectionisindicated bya three-headedarrow.Abbreviations: dyn,dynorphin, enk,enkephalin, GABA,gamma-amino-butyricacid, glu, glutamate, GPe,globuspallidusparsexterna, GPi,globuspallidusparsinterna, IL,intralaminarthalamicnuclei, MD, mediodorsalnucleus, PPA,pedunculopontinearea, SC,superiorcolliculus, SNpc,substantianigraparscompacta, SNpr,substantianigraparsreticulata, SP,substanceP, STN,subthalamicnucleus, VA,ventralanteriornucleus, VL, ventrallateralnucleus.

CellTypes

Mediumspinystriatalneuronsmakeup90% 95%ofthestriatalneuronpopulation.They projectoutsideofthestriatumandreceiveanumberofinputsinadditiontotheimportant

corticalinput,including(1)excitatoryglutam atergicinputsfromthalamus;(2)cholinergic inputfromstriatalinterneurons;(3)gamma -amino-butyricacid(GABA),substanceP, andenkephalininputfromadjacentmediumspinystriatalneurons;(4)GABAinput fromfast-spikinginterneurons;(5)alarge inputfromdopamine-containingneuronsin theSNpc;(6)amoresparseinputfromtheser otonin-containingneuronsinthedorsal andmedianraphenuclei.

Thefast-spikingGABAergicstriatalinterneuronsmakeuponly2% 4%ofthestriatal neuronpopulation,buttheyexertpowerfulinhibitiononmediumspinyneurons.Likemediumspinyneurons,thestriatalinterneuronsreceiveexcitatoryinputfromcerebralcortex. Theyappeartoplayanimportantroleinlimitingtheactivityofmediumspinyneurons andinfocusingthespatialpatternoftheiractivation. 10 Abnormalitiesinthenumberorfunctionoftheseneuronshavebeenlinkedtothepathobiologyofinvoluntarymovements. 11 13

Compartments

Althoughtherearenoapparentregionaldifferencesinthestriatumbasedoncelltype,an intricateinternalorganizationhasbeenreve aledwithspecialstains.Whenthestriatumis stainedforacetylcholinesterase(AChE),there isapatchydistributionoflightlystainingregionswithinmoreheavilystainedregions. 14 TheAChE-poorpatcheshavebeencalled striosomes andtheAChE-richareashavebeencalledtheextrastriosomal matrix .Thematrix formsthebulkofthestriatalvolumeandreceivesinputfrommostareasofcerebralcortex. Withinthematrixareclustersofneuronswithsimilarinputsthathavebeentermed matrisomes.ThebulkoftheoutputfromcellsinthematrixistobothsegmentsoftheGP,VP,and toSNpr.Thestriosomesreceiveinputfrom prefrontalcortexan dsendoutputtoSNpc. 15 Immunohistochemicaltechniqueshavedemon stratedthatmanysubstancessuchassubstanceP,dynorphin,andenkephalinhaveapatchydistributionthatmaybepartlyor whollyinregisterwiththestriosomes.Thestri osome-matrixorganizationsuggestsalevel offunctionalsegregationwithinthestriatumthatmaybemaintainedbydifferential in fl uencesofdopamine.16 Whilepreferentialinvolvemento fthestriosomeormatrixcompartmentshasbeensuggestedinsomedisorders,17 theclinicalsigni fi canceofthisorganizationisstillnotwellunderstood.

Neurotransmitters

Dopamine

Thedopamineinputtothestriatumterminateslargelyontheshaftsofthedendritic spinesofmediumspinyneuronswhereitisinapositiontomodulatetransmissionfrom thecerebralcortextothestriatum.18 Theactionofdopamineonstriatalneuronsdepends onthetypeofdopaminereceptorinvolved.FivetypesofGprotein-coupleddopaminereceptorshavebeendescribed(D1.D5).19 Thesehavebeengroupedintotwofamiliesbasedon theirlinkagetoadenylcyclaseactivityandresponsetoagonists.TheD1familyincludes D1andD5receptorsandtheD2familyincludesD2,D3,andD4receptors.Theconventional viewhasbeenthatdopamineactsatD1receptorstofacilitatetheactivityofpostsynapticneuronsandatD2receptorstoinhibitpostsynapticneurons.20 Indeed,thisisafundamental 1.BasalGangliaAnatomy,Biochemistry,andPhysiology

conceptforsomemodelsofbasalgangliapathophysiology.21,22 However,thephysiologiceffectofdopamineonstriatalneuronsismorecomplex.WhileactivationofdopamineD1receptorspotentiatestheeffectofcorticalinputtostriatalneuronsinsomestates,itreducesthe efficacyofcorticalinputinothers.23 ActivationofD2receptorsmoreconsistentlydecreases theeffectofcorticalinputtostriatalneuron.24 Dopaminecontributestofocusingthespatial andtemporalpatternsofstriatalactivity.

Inadditiontoshort-termfacilitationorinhibitionofstriatalactivity,thereisevidencethat dopaminecanmodulatecorticostriataltransmissionbymechanismsoflong-termdepression (LTD)andlong-termpotentiation(LTP).Throughthesemechanisms,dopaminestrengthens orweakenstheefficacyofcorticostriatalsynapsesandcanthusmediatereinforcementofspecificdischargepatterns.LTPandLTDarethoughttobefundamentaltomanyneuralmechanismsoflearningandmayunderliethehypothesizedroleofthebasalgangliainhabit learning.25 SNpcdopamineneurons fireinrelationtobehaviorallysignificanteventsand reward.26 Thesesignalsarelikelytomodifytheresponsesofstriatalneuronstoinputsthat occurinconjunctionwiththedopaminesignalresultinginthereinforcementofmotorand otherbehaviorpatterns.Striatallesionsorfocalstriataldopaminedepletionimpairsthe learningofnewmovementsequences,27 supportingaroleforthebasalgangliaincertaintypes ofprocedurallearning.Dopaminemayalsoplayaroleinotheraspectsofmotorlearning.28

GABA

MediumspinystriatalneuronscontaintheinhibitoryneurotransmitterGABAandcolocalizedpeptideneurotransmitters.29,30 Basedonthetypeofneurotransmittersandthepredominanttypeofdopaminereceptortheycontain,themediumspinyneuronscanbedividedinto twopopulations.OnepopulationcontainsGABA,dynorphin,andsubstancePandprimarily expressesD1dopaminereceptors.Theseneuronsprojecttothebasalgangliaoutputnuclei, GPi,andSNpr.ThesecondpopulationcontainsGABAandenkephalinandprimarilyexpressesD2dopaminereceptors.Theseneuronsprojecttotheexternalsegmentoftheglobus pallidus(GPe).21

Acetylcholine

Cholinergicinterneuronsdenselyinnervatethestriatum 31 andmodulatedopamine release.32 Additionalcholinergicinputintostriatumcomesfromthepedunculopontinenucleusandthelaterodorsaltegmentalnucleiinthebrainstem.33 Viamuscarinicacetylcholine receptors,cholinergicinterneuronsin fluencebothdopamineD1andD2receptorexpressingmediumspinyneurons.Akeypropertyofcholinergicinterneuronsistheirtonic spikingactivity,andthustheyarealsoreferredtoastonicallyactiveneurons.34

OtherBasalGangliaNuclei

SubthalamicNucleus

TheSTNreceivesanexcitatory,glutamatergicinputfrommanyareasoffrontallobeswith especiallylargeinputsfrommotorareasofcortex.35 TheSTNalsoreceivesinhibitory

GABAergicinputfromGPe.TheoutputfromtheSTNisglutamatergicandexcitatorytothe basalgangliaoutputnuclei,GPi,VP,andSNpr.STNalsosendsanexcitatoryprojectionback toGPe.ThereisasomatotopicorganizationinSTN36 andarelativetopographicseparationof “motor” and “cognitive” inputstoSTN.

OutputNuclei:GlobusPallidusInternaandSubstantiaNigraParsReticulata

TheprimarybasalgangliaoutputarisesfromGPi,aGPi-likecomponentofVP,andSNpr. Asdescribedabove,GPiandSNprreceiveexcitatoryinputfromSTNandinhibitoryinput fromstriatum.TheyalsoreceiveaninhibitoryinputfromGPe.Thedendritic fieldsofGPi, VP,andSNprneuronsspanupto1mmdiameterandthushavethepotentialtointegrate alargenumberofconverginginputs.37 TheoutputfromGPi,VP,andSNprisinhibitory andusesGABAasitsneurotransmitter.Theprimaryoutputisdirectedtothalamicnuclei thatprojecttothefrontallobes:theventrolateral,ventroanterior,andmediodorsalnuclei. ThethalamictargetsofGPi,VP,andSNprproject,inturn,tofrontallobe,withthestrongest outputgoingtomotorareas.Collateralsoftheaxonsprojectingtothalamusprojecttoanarea atthejunctionofthemidbrainandponsintheareaofthepedunculopontinenucleus.38 Other outputneurons(20%)projecttointralaminarnucleiofthethalamus,tothelateralhabenula, ortothesuperiorcolliculus.39

Thebasalgangliamotoroutputhasasomatotopicorganizationsuchthatthebodybelow theneckislargelyrepresentedinGPi,andtheheadandeyesarelargelyrepresentedinSNpr. Theseparaterepresentationofdifferentbodypartsismaintainedthroughoutthebasal ganglia.Withintherepresentationofanindividualbodypart,italsoappearsthatthereis segregationofoutputstodifferentmotorareasofcortexandthatanindividualGPineuron sendsoutputviathalamustojustoneareaofcortex.40 Thus,GPineuronsthatprojectviathalamustomotorcortexareadjacentto,butseparatefrom,thosethatprojecttopremotorcortex orsupplementarymotorarea.GPineuronsthatprojectviathalamustoprefrontalcortexare alsoseparatefromthoseprojectingtomotorareasandfromVPneuronsprojectingviathalamustoorbitofrontalcortex.Theanatomicsegregationofbasalganglia-thalamocorticaloutputssuggestsfunctionalsegregationattheoutputlevel,butotheranatomicevidence suggestsinteractionsbetweencircuitswithinthebasalganglia(seeabove).5,41

GlobusPallidusExterna

TheGPeandtheGPe-likepartofVPmaybeviewedasintrinsicnucleiofthebasalganglia. LikeGPiandSNpr,GPereceivesaninhibitoryprojectionfromthestriatumandanexcitatory onefromSTN.UnlikeGPi,thestriatalprojectiontoGPecontainsGABAandenkephalinbut notsubstanceP.21 TheoutputofGPeisquitedifferentfromtheoutputofGPi.Theoutput fromGPeisGABAergicandinhibitory,andthemajorityoftheoutputprojectstoSTN. TheconnectionsfromstriatumtoGPe,fromGPetoSTN,andfromSTNtoGPiformthe “indirect” striatopallidalpathwaytoGPi42 (Fig.1.1).Inaddition,thereisamonosynaptic GABAergicinhibitoryoutputfromGPedirectlytoGPiandtoSNprandaGABAergicprojectionbacktostriatum.43 Thus,GPeneuronsareinapositiontoprovidefeedbackinhibition

toneuronsinstriatumandSTNandfeedforwardinhibitiontoneuronsinGPiandSNpr.This circuitrysuggeststhatGPemayacttooppose,limit,orfocustheeffectofthestriatalandSTN projectionstoGPiandSNpraswellasfocusactivityintheseoutputnuclei.

SubstantiaNigraParsCompacta

DopamineinputtothestriatumarisesfromSNpcandtheventraltegmentalarea(VTA). SNpcprojectstomostofthestriatum;VTAprojectstotheventralstriatum.TheSNpcand VTAaremadeupoflargedopamine-containingcells.SNpcreceivesinputfromthestriatum, speci ficallyfromthestriosomes.ThisinputisGABAergicandinhibitory.TheSNpcandVTA dopamineneuronsprojecttocaudateandputameninatopographicmanner,41 butwithoverlap.Thenigraldopamineneuronsreceiveinputsfromonestriatalcircuitandprojectbackto thesameandtoadjacentcircuits.Thus,theyappeartobeinapositiontomodulateactivity acrossfunctionallydifferentcircuits.

InhibitingandDisinhibitingMotorPatterns

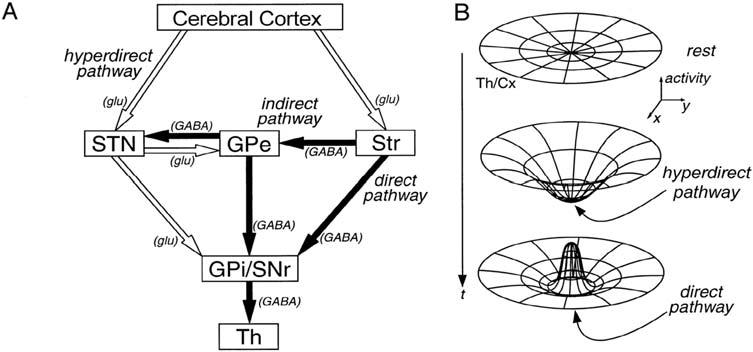

Althoughthebasalgangliaintrinsiccircuitryiscomplex,theoverallpictureisoftwoprimarypathwaysthroughthebasalgangliafromcerebralcortexwiththeoutputdirectedvia thalamusatthefrontallobes.Thesepathwaysconsistoftwodisynapticpathwaysfromcortex tothebasalgangliaoutput(Fig.1.2).Inaddition,thereareseveralmultisynapticpathways involvingGPe.Thetwodisynapticpathwaysarefromcortexthrough(1)striatum(the direct pathway) and(2)STN(the hyperdirectpathway) tothebasalgangliaoutputs.Thesepathways haveimportantanatomicalandfunctionaldifferences.First,thecorticalinputtoSTNcomes onlyfromfrontallobe,whereastheinputtostriatumarisesfromvirtuallyallareasofcerebral cortex.Second,theoutputfromSTNisexcitatory,whereastheoutputfromstriatumisinhibitory.Third,theexcitatoryroutethroughSTNisfasterthantheinhibitoryroutethroughstriatum.44 Finally,theSTNprojectiontoGPiisdivergentandthestriatalprojectionismore focused.45 Thus,thetwodisynapticpathwaysfromcerebralcortextothebasalgangliaoutput nuclei,GPiandSNpr,providefast,widespread,divergentexcitationthroughSTNand slower,focused,inhibitionthroughstriatum.17 ThisorganizationprovidesananatomicalbasisforfocusedinhibitionandsurroundexcitationofneuronsinGPiandSNpr(Fig.1.3). BecausetheoutputofGPiandSNprisinhibitory,thisresultsinfocusedfacilitationandsurroundinhibitionofbasalgangliathalamocorticaltargets.47 Thetonicallyactiveinhibitory outputofthebasalgangliaactsasa “brake” onmotorpatterngenerators(MPGs)inthecerebralcortex(viathalamus)andbrainstem.Whenamovementisinitiatedbyaparticular MPG,basalgangliaoutputneuronsprojectingtocompetingMPGsincreasetheir firing rate,therebyincreasinginhibitionandapplyinga “brake” onthosegenerators.Otherbasal gangliaoutputneuronsprojectingtothegeneratorsinvolvedinthedesiredmovement decreasetheirdischarge,therebyremovingtonicinhibitionandreleasingthe “brake” from thedesiredmotorpatterns.Thus,theintendedmovementisenabledandcompetingmovementsarepreventedfrominterferingwiththedesiredone.35,48

1.BasalGangliaAnatomy,Biochemistry,andPhysiology

FIGURE1.2 Schematicdiagramofthehyperdirectcortico-subthalamo-pallidal,directcortico-striato-pallidal,and indirectcortico-striato-GPe-subthalamo-GPipathways. Whiteandblackarrows representexcitatoryglutamatergic(glu) andinhibitoryGABAergic(GABA)projections,respectively. GPe,externalsegmentoftheglobuspallidus; GPi,internalsegmentoftheglobuspallidus; SNr,substantianigraparsreticulata; STN,subthalamicnucleus; Str,striatum; Th,thalamus. B:aschematicdiagramexplainingtheactivitychangeovertime(t)inthethalamocorticalprojection (Th/Cx)followingthesequentialinputsthroughthehyperdiectcortico-subthalamo-pallidal(middle)anddirect cortico-striato-pallidal(bottom)pathways. ModifiedfromRef.[44].

ImplicationsforDisease:FocalLesionsandAbnormalMovements

Thisschemeprovidesaframeworkforunderstandingboththepathophysiologyofparkinsonism35,49 andinvoluntarymovement.35,48 Differentinvoluntarymovementssuchasparkinsonism,chorea,dystonia,orticsresultfromdifferentabnormalitiesinthebasalganglia circuits.LossofdopamineinputtothestriatumresultsinalossofnormalpausesofGPi dischargeduringvoluntarymovement.Hence,thereisexcessiveinhibitionofMPGsandultimatelybradykinesia.49 Furthermore,lossofdopamineresultsinabnormalsynchronyofGPi neuronaldischargeandlossofthenormalspatialandtemporalfocusofGPiactivity.49 51 BroadlesionsofGPiorSNprdisinhibitbothdesiredandunwantedmotorpatternsleading toinappropriateactivationofcompetingmotorpatterns,butnormalgenerationofthe wantedmovement.Thus,lesionsofGPicausecocontractionofmultiplemusclegroups anddifficultyturningoffunwantedmotorpatterns,similartowhatisseenindystonia, butdonotaffectmovementinitiation.52 LesionsofSNprcauseunwantedsaccadiceyemovementsthatinterferewiththeabilitytomaintainvisual fixationbutdonotimpairtheinitiation ofvoluntarysaccades.53 Lesionsofputamenmaycausedystoniaduetothelossoffocused inhibitioninGPi.48 LesionsofSTNproducecontinuousinvoluntarymovementsofthecontralaterallimbs(hemiballismorhemichorea).48 Despitetheinvoluntarymovements,voluntary movementscanstillbeperformed.Althoughstructurallesionsofputamen,GPi,SNpr,or STNproducecertaintypesofunwantedmovementsorbehaviors,theydonotproduce tics.Ticsaremorelikelytoarisefromabnormalactivitypatternsinthestriatum.12,48

FIGURE1.3 Schematicofnormalfunctionalorganizationofthebasalgangliaoutput.Excitatoryprojectionsare indicatedwith openarrows;inhibitoryprojectionsareindicatedwith filledarrows.Relativemagnitudeofactivityis representedbylinethickness. ModifiedfromRef.[46].

Althoughthefocusofthisdiscussionofbasalgangliacircuitshasbeenonmotorcontrol andmovementdisorders,itislikelythatthefundamentalprinciplesoffunctioninthesomatomotor,oculomotor,limbic,andcognitivebasalgangliacircuitsaresimilar.Ifthebasic schemeoffacilitationandinhibitionofcompetingmovementsisextendedtoencompass morecomplexbehaviorsandthoughts,manyfeaturesofbasalgangliadisorderscanbe explainedasafailuretofacilitatewantedbehaviorsandsimultaneouslyinhibitunwantedbehaviorsduetoabnormalbasalgangliaoutputpatterns.Indeed,manymovementdisorders areaccompaniedbycognitiveandaffectivesymptoms.54 56

References

1.Baez-MendozaR,SchultzW.Theroleofthestriatuminsocialbehavior. FrontNeurosci.2013;7:233.

2.KempJM,PowellTPS.Thecorticostriateprojectioninthemonkey. Brain.1970;93:525 546.

3.FudgeJ,KunishioK,WalshC,RichardD,HaberS.Amygdaloidprojectionstoventromedialstriatalsubterritoriesintheprimate. Neuroscience.2002;110:257 275.

4.CherubiniE,HerrlingPL,LanfumeyL,StanzioneP.Excitatoryaminoacidsinsynapticexcitationofratstriatal neuronesinvitro. JPhysiol(Lond).1988;400:677 690.

1.BasalGangliaAnatomy,Biochemistry,andPhysiology

5.KellyR,StrickPL.Macro-architectureofbasalganglialoopswiththecerebralcortex:useofrabiesvirustoreveal multisynapticcircuits. ProgBrainRes.2004;143:449 459.

6.AlexanderGE,DeLongMR,StrickPL.Parallelorganizationoffunctionallysegregatedcircuitslinkingbasal gangliaandcortex. AnnuRevNeurosci.1986;9:357 381.

7.WilsonCJ,GrovesPM.Finestructureandsynapticconnectionsofthecommonspinyneuronoftheratneostriatum:astudyemployingintracellularinjectionofhorseradishperoxidase. JCompNeurol.1980;194:599 614.

8.SelemonLD,Goldman-RakicPS.Longitudinaltopographyandinterdigitationofcorticostriatalprojectionsinthe rhesusmonkey. JNeurosci.1985;5:776 794.

9.FlahertyAW,GraybielAM.Corticostriataltransformationsintheprimatesomatosensorysystem.Projections fromphysiologicallymappedbody-partrepresentations. JNeurophysiol.1991;66:1249 1263.

10.MalletN,LeMoineC,CharpierS,GononF.Feedforwardinhibitionofprojectionneuronsbyfast-spikingGABA interneuronsintheratstriatuminvivo. JNeurosci.2005;25:3857 3869.

11.KataokaY,KalanithiPS,GrantzH,etal.Decreasednumberofparvalbuminandcholinergicinterneuronsinthe striatumofindividualswithTourettesyndrome. JCompNeurol.2010;518:277 291.

12.McCairnKW,BronfeldM,BelelovskyK,Bar-GadI.Theneurophysiologicalcorrelatesofmotorticsfollowing focalstriataldisinhibition. Brain.2009;132:2125 2138.

13.GittisAH,LeventhalDK,FensterheimBA,PettiboneJR,BerkeJD,KreitzerAC.Selectiveinhibitionofstriatal fast-spikinginterneuronscausesdyskinesias. JNeurosci.2011;31:15727 15731.

14.GraybielAM,AosakiT,FlahertyAW,KimuraM.Thebasalgangliaandadaptivemotorcontrol. Science. 1994;265:1826 1831.

15.GerfenCR.Theneostriatalmosaic:multiplelevelsofcompartmentalorganizationinthebasalganglia. AnnuRev Neurosci.1992;15:285 320.

16.PragerEM,DormanDB,HobelZB,MalgadyJM,BlackwellKT,PlotkinJL.Dopamineoppositelymodulatesstate transitionsinstriosomeandmatrixdirectpathwaystriatalspinyneurons. Neuron.2020;108:1091 1102.e5.

17.CrittendenJR,GraybielAM.Basalgangliadisordersassociatedwithimbalancesinthestriatalstriosomeandmatrixcompartments. FrontNeuroanat.2011;5:59.

18.BouyerJJ,ParkDH,JohTH,PickelVM.Chemicalandstructuralanalysisoftherelationbetweencorticalinputs andtyrosinehydroxylase-containingterminalsinratneostriatum. BrainRes.1984;302:267 275.

19.SibleyDR,MonsmaFJ.Molecularbiologyofdopaminereceptors. TrendsPharmacolSci.1992;13:61 69.

20.GerfenCR,EngberTM,MahanLC,etal.D1 andD2 dopaminereceptor-regulatedgeneexpressionofstriatonigral andstriatopallidalneurons. Science.1990;250:1429 1432.

21.AlbinRL,YoungAB,PenneyJB.Thefunctionalanatomyofbasalgangliadisorders. TrendsNeurosci 1989;12:366 375.

22.DeLongMR.Primatemodelsofmovementdisordersofbasalgangliaorigin. TrendsNeurosci.1990;13:281 285.

23.Hernandez-LopezS,BargasJ,SurmeierDJ,ReyesA,GalarragaE.D1receptoractivationenhancesevoked dischargeinneostriatalmediumspinyneuronsbymodulatinganL-typeCa2þ conductance. JNeurosci. 1997;17:3334 3342.

24.NicolaS,SurmeierJ,MalenkaR.Dopaminergicmodulationofneuronalexcitabilityinthestriatumandnucleus accumbens. AnnuRevNeurosci.2000;23:185 215.

25.JogM,KubotaY,ConnollyC,HillegaartV,GraybielA.Buildingneuralrepresentationsofhabits. Science. 1999;286:1745 1749.

26.SchultzW,RomoR,LjungbergT,MirenowiczJ,HollermanJR,DickinsonA.Reward-relatedsignalscarriedby dopamineneurons.In:HoukJC,DavisJL,BeiserDG,eds. ModelsofInformationProcessingintheBasalGanglia. Cambridge:MITPress;1995:233 249.

27.MatsumotoN,HanakawaT,MakiS,GraybielAM,KimuraM.Roleofnigrostriataldopaminesysteminlearning toperformsequentialmotortasksinapredictivemanner. JNeurophysiol.1999;82:978 998.

28.WoodAN.Newrolesfordopamineinmotorskillacquisition:lessonsfromprimates,rodents,andsongbirds. LID.2020. https://doi.org/10.1152/jn.00648

29.KreitzerAC.Physiologyandpharmacologyofstriatalneurons. AnnuRevNeurosci.2009;32:127 147.

30.PennyGR,AfsharpourS,KitaiST.Theglutamatedecarboxylase-,leucineenkephalin-,methionineenkephalinandsubstanceP-immunoreactiveneuronsintheneostriatumoftheratandcat:evidenceforpartialpopulation overlap. Neuroscience.1986;17:1011 1045.

31.KawaguchiY,WilsonCJ,AugoodSJ,EmsonPC.Striatalinterneurones:chemical,physiologicalandmorphologicalcharacterization. TrendsNeurosci.1995;18:527 535.

32.ThrelfellS,LalicT,PlattNJ,JenningsKA,DeisserothK,CraggSJ.Striataldopaminereleaseistriggeredbysynchronizedactivityincholinergicinterneurons. Neuron.2012;75:58 64.

33.DautanD,Huerta-OcampoI,WittenIB,etal.Amajorexternalsourceofcholinergicinnervationofthestriatum andnucleusaccumbensoriginatesinthebrainstem. JNeurosci.2014;34:4509 4518.

34.BennettBD,CallawayJC,WilsonCJ.Intrinsicmembranepropertiesunderlyingspontaneoustonic firinginneostriatalcholinergicinterneurons. JNeurosci.2000;20:8493 8503.

35.MinkJW.Thebasalganglia:focusedselectionandinhibitionofcompetingmotorprograms. ProgrNeurobiol 1996;50:381 425.

36.NambuA,TakadaM,InaseM,TokunoH.Dualsomatotopicalrepresentationsintheprimatesubthalamicnucleus:evidencefororderedbutreversedbody-maptransformationsfromtheprimarymotorcortexandthesupplementarymotorarea. JNeurosci.1996;16:2671 2683.

37.PercheronG,YelnikJ,FrancoisC.Agolgianalysisoftheprimateglobuspallidus.III.Spatialorganizationofthe striato-pallidalcomplex. JCompNeurol.1984;227:214 227.

38.ParentA.Extrinsicconnectionsofthebasalganglia. TrendsNeurosci.1990;13:254 258.

39.FrancoisC,PercheronG,YelnikJ,TandeD.Atopographicstudyofthecourseofnigralaxonsandofthedistributionofpallidalaxonalendingsinthecentremedian-parafascicularcomplexofmacaques. BrainRes. 1988;473:181 186.

40.HooverJE,StrickPL.Multipleoutputchannelsinthebasalganglia. Science.1993;259:819 821.

41.HaberSN,FudgeJL,McFarlandNR.Striatonigrostriatalpathwaysinprimatesformanascendingspiralfromthe shelltothedorsolateralstriatum. JNeurosci.2000;20:2369 2382.

42.AlexanderGE,CrutcherMD.Functionalarchitectureofbasalgangliacircuits:neuralsubstratesofparallelprocessing. TrendsNeurosci.1990;13:266 271.

43.BolamJP,HanleyJJ,BoothPA,BevanMD.Synapticorganisationofthebasalganglia. JAnat.2000;196:527 542.

44.NambuA,TokunoH,HamadaI,etal.Excitatorycorticalinputstopallidalneuronsviathesubthalamicnucleus inthemonkey. JNeurophysiol.2000;84:289 300.

45.ParentA,HazratiL-N.Anatomicalaspectsofinformationprocessinginprimatebasalganglia. TrendsNeurosci 1993;16:111 116.

46.MinkJW.BasalgangliadysfunctioninTourette’ssyndrome:anewhypothesis. PediatrNeurol.2001;25:190 198.

47.OzakiM,SanoH,SatoS,etal.Optogeneticactivationofthesensorimotorcortexreveals “localinhibitoryand globalexcitatory” inputstothebasalganglia. CerebCortex.2017;27:5716 5726.

48.MinkJ.Thebasalgangliaandinvoluntarymovements:impairedinhibitionofcompetingmotorpatterns. Arch Neurol.2003;60:1365 1368.

49.BoraudT,BezardE,BioulacB,GrossCE.Fromsingleextracellularunitrecordinginexperimentalandhuman Parkinsonismtothedevelopmentofafunctionalconceptoftheroleplayedbythebasalgangliainmotorcontrol. ProgrNeurobiol.2002;66:265 283.

50.RazA,VaadiaE,BergmanH.Firingpatternsandcorrelationsofspontaneousdischargeofpallidalneuronsin thenormalandthetremulous1-methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridineVervetmodelofparkinsonism. JNeurosci.2000;20:8559 8571.

51.TremblayL,FilionM,BedardPJ.ResponsesofpallidalneuronstostriatalstimulationinmonkeyswithMPTPinduceparkinsonism. BrainRes.1989;498:17 33.

52.MinkJW,ThachWT.Basalgangliamotorcontrol.III.Pallidalablation:normalreactiontime,musclecocontraction,andslowmovement. JNeurophysiol.1991;65:330 351.

53.HikosakaO,WurtzRH.ModificationofsaccadiceyemovementsbyGABA-relatedsubstances.II.Effectsofmuscimolinmonkeysubstantianigraparsreticulata. JNeurophysiol.1985;53:292 308.

54.AsmusF,GasserT.Dystonia-plussyndromes. EurJNeurol.2010;17(Suppl1):37 45.

55.PolettiM,DeRosaA,BonuccelliU.AffectivesymptomsandcognitivefunctionsinParkinson’sdisease. JNeurol Sci.2012;317:97 102.

56.RossCA,AylwardEH,WildEJ,etal.Huntingtondisease:naturalhistory,biomarkersandprospectsfortherapeutics. NatRevNeurol.2014;10:204 216.

Thispageintentionallyleftblank

CerebellarAnatomy,Biochemistry, Physiology,andPlasticity

HarveyS.Singer1,JonathanW.Mink2, DonaldL.Gilbert3 andJosephJankovic4

1DepartmentofNeurology,JohnsHopkinsHospital,Baltimore,MD,UnitedStates; 2Division ofChildNeurology,UniversityofRochesterMedicalCenter,Rochester,NY,UnitedStates; 3DivisionofNeurology,CincinnatiChildren’sHospitalMedicalCenter,Cincinnati,OH,United States; 4DepartmentofNeurology,BaylorCollegeofMedicine,Houston,TX,UnitedStates

IntroductionandOverview16

OverviewofCerebellarStructure, Function,andSymptomLocalization16

MacroscopictoMicroscopicCerebellar Structure17

CerebellarStructural “Threes” 17

TheThreeAnatomic Regions StructuresandAfferent Connections18

TheThreeCerebellarFunctionalRegions ConnecttoThreeDeepCerebellar Nuclei18

TheThreePairedCerebellarPeduncles21 TypesofAfferentFibers23

TheThreeLayersofCerebellarCortex andTheirCellTypes23

CerebellarIntegrationwithBasal GangliaCircuits23

NeurotransmittersintheCerebellum26 Glutamate26 Gamma-AminobutyricAcid27 Acetylcholine,Dopamine, Norepinephrine,andSerotonin27 Endocannabinoids28

NeuroplasticityintheCerebellum28 CerebellarStimulation28 Conclusion30 References30