CONTENTS

introduction

James Miller vii

translator’s note

Pamela Mensch xix

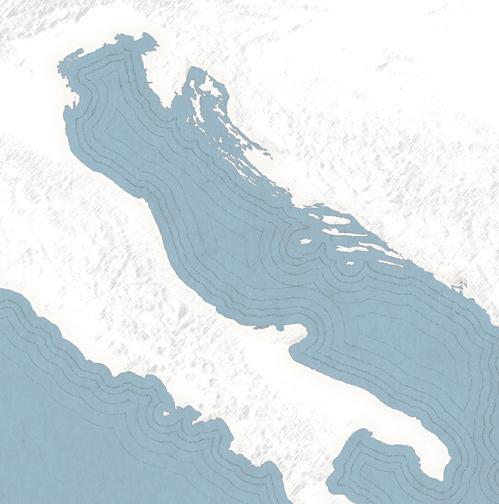

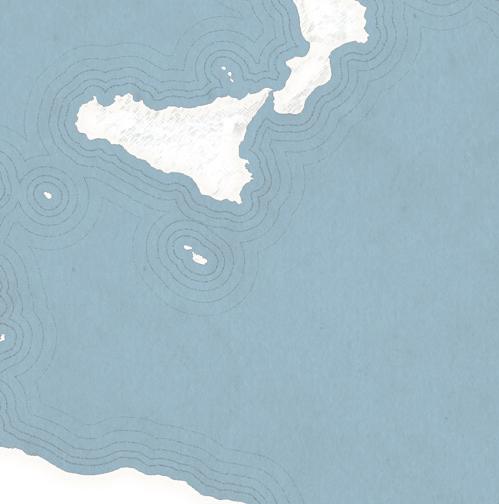

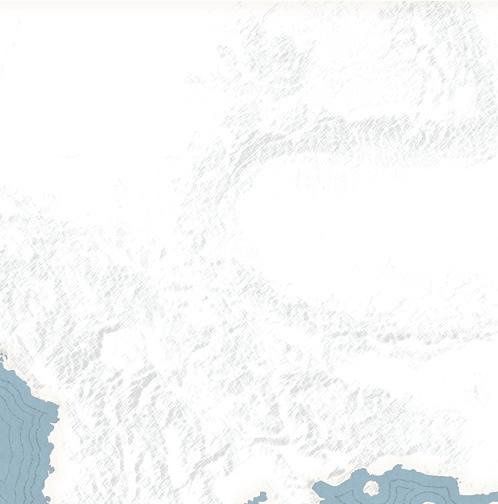

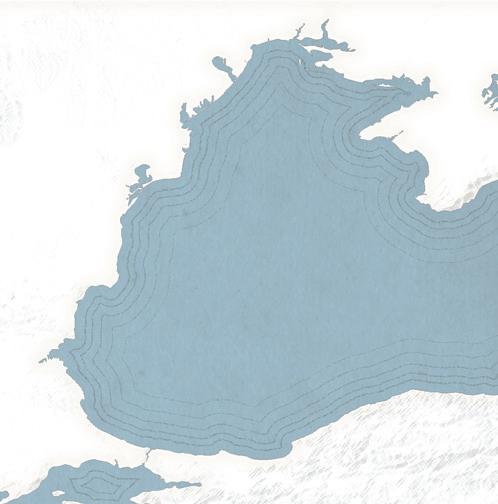

map xx

lives of the eminent philosophers

BOOK 1 3

Prologue; Thales, Solon, Chilon, Pittacus, Bias, Cleobulus, Periander, Anacharsis, Myson, Epimenides, Pherecydes

BOOK 2 59

Anaximander, Anaximenes, Anaxagoras, Archelaus, Socrates, Xenophon, Aeschines, Aristippus, Phaedo, Euclides, Stilpo, Crito, Simon, Glaucon, Simmias, Cebes, Menedemus

BOOK 3 133

Plato

BOOK 4 177

Speusippus, Xenocrates, Polemon, Crates, Crantor, Arcesilaus, Bion, Lacydes, Carneades, Clitomachus

BOOK 5 211

Aristotle, Theophrastus, Strato, Lyco, Demetrius, Heraclides

BOOK 6 259

Antisthenes, Diogenes, Monimus, Onesicritus, Crates, Metrocles, Hipparchia, Menippus, Menedemus

BOOK 7 311

Zeno, Ariston, Herillus, Dionysius, Cleanthes, Sphaerus, Chrysippus

BOOK 8 393

Pythagoras, Empedocles, Epicharmus, Archytas, Alcmeon, Hippasus, Philolaus, Eudoxus

BOOK 9 435

Heraclitus, Xenophanes, Parmenides, Melissus, Zeno, Leucippus, Democritus, Protagoras, Diogenes, Anaxarchus, Pyrrho, Timon

BOOK 10 491 Epicurus

Diogenes Laertius: From Inspiration to Annoyance (and Back)

Anthony Grafton 546

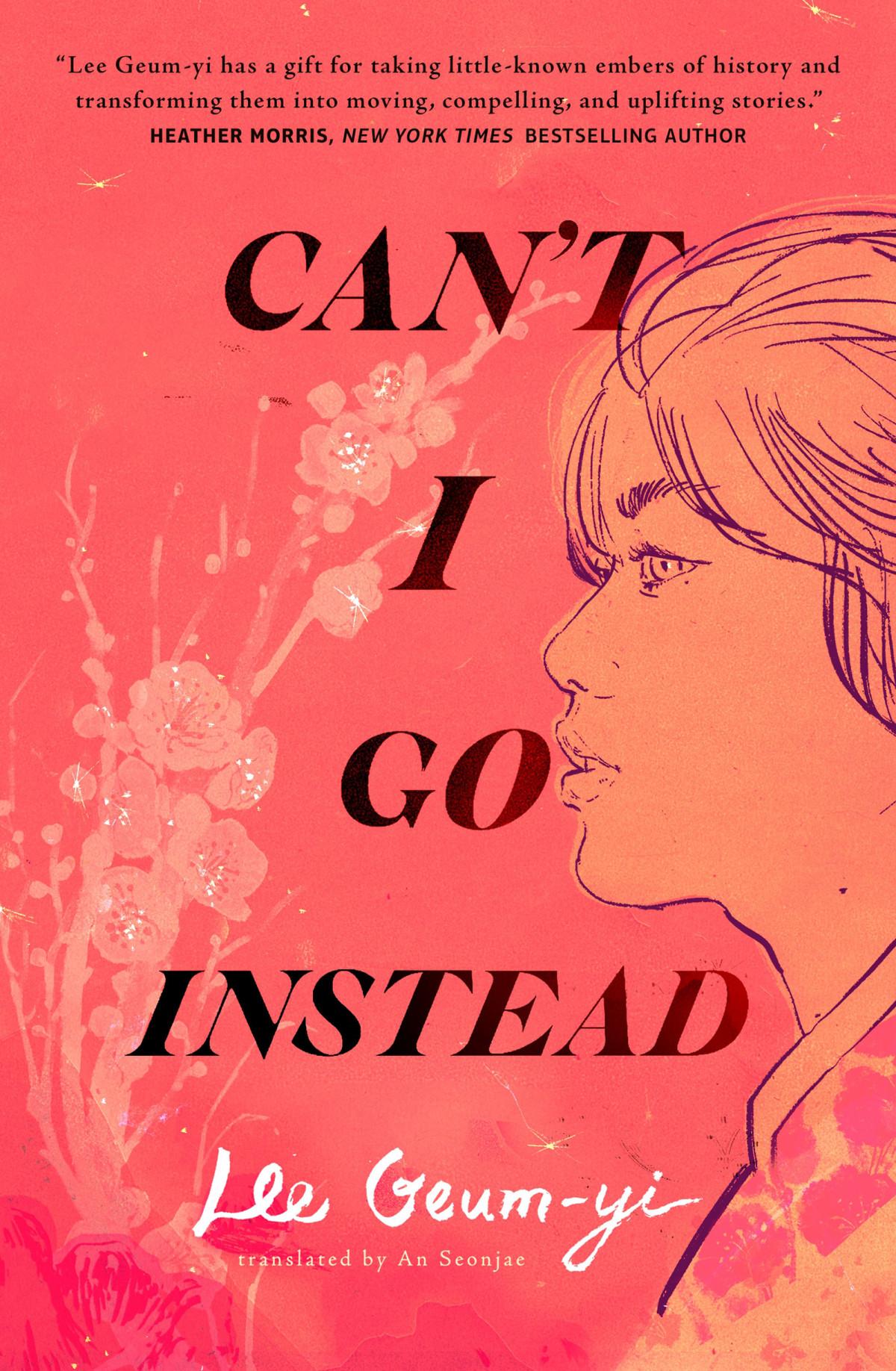

Raphael’s Eminent Philosophers: The School of Athens and the Classic Work Almost No One Read

Ingrid D. Rowland 554

Diogenes’ Epigrams

Kathryn Gutzwiller 561

Corporeal Humor in Diogenes Laertius

James Romm 567

Philosophers and Politics in Diogenes Laertius

Malcolm Schofield 570

Diogenes Laertius and Philosophical Lives in Antiquity

Giuseppe Cambiano 574

“A la Recherche du Texte Perdu”: The Manuscript Tradition of Diogenes Laertius’ Lives of the Eminent Philosophers

Tiziano Dorandi 577

Diogenes Laertius in Byzantium

Tiziano Dorandi 582

Diogenes Laertius in Latin

Tiziano Dorandi 585

Diogenes Laertius and the Pre-Socratics

André Laks 588

Plato’s Doctrines in Diogenes Laertius

John Dillon 592

Cynicism: Ancient and Modern R. Bracht Branham 597

Zeno of Citium: Cynic Founder of the Stoic Tradition

A. A. Long 603

Skeptics in Diogenes Laertius

James Allen 610

Epicurus in Diogenes Laertius

James Allen 614

Diogenes Laertius and Nietzsche

Glenn W. Most 619

Guide to Further Reading

Jay R. Elliott 623

Glossary of Ancient Sources

Joseph M. Lemelin 634

Illustration Credits 649

Index 655

INTRODUCTION

James Miller

Lives of the Eminent Philosophers of Diogenes Laertius is a crucial source for much of what we know about the origins of philosophy in Greece. The work covers a larger number of figures and a longer period of time than any other extant ancient source. Yet few classical texts of such significance have provoked such sharp disagreement, even contempt.

Modern scholars have generally dismissed Diogenes Laertius as a mediocre anthologist, if not an “ignoramus” (thus the great German classicist Werner Jaeger). Even when dealing with invaluable evidence of otherwise unknown philosophical doctrines, concluded one expert, “we may be said to have a museum of philosophical ideas which are pinned like beetles on pegs in glass cases to be looked at and admired, a compilation which is no more capable of furnishing an understanding of the history of these ideas than the mere examination of beetles under a glass will yield an understanding of the life of the beetle.”1

Renaissance readers, though not uncritical, by contrast tended to revel in the book’s abundance of biographical lore. In one of his Essays, Montaigne says he wished that instead of just one Diogenes Laertius there had been a dozen: “for I am equally curious to know the lives and fortunes of these great instructors of the world as to know the diversity of their doctrines and opinions.”2

Friedrich Nietzsche, who came to admire Lives after itemizing its manifold defects from the standpoint of modern scholarship, quipped that Diogenes Laertius is the porter who guards the gate leading to the Castle of Ancient Philosophy. Like Montaigne, Nietzsche savored the paradox that this gatekeeper was also a fabulist. But the biographies recounted by Diogenes became for him one touchstone of how properly to search for wisdom—through studying lives as well as doctrines. “I for one prefer reading Diogenes Laertius,” Nietzsche wrote in 1874, in the context of dismissing

1 Richard Hope, The Book of Diogenes Laertius: Its Spirit and Its Method (New York, 1930), 96, 201.

2 Montaigne, Essays, bk. II, ch, 10, “Of Books.”

JAMES MILLER

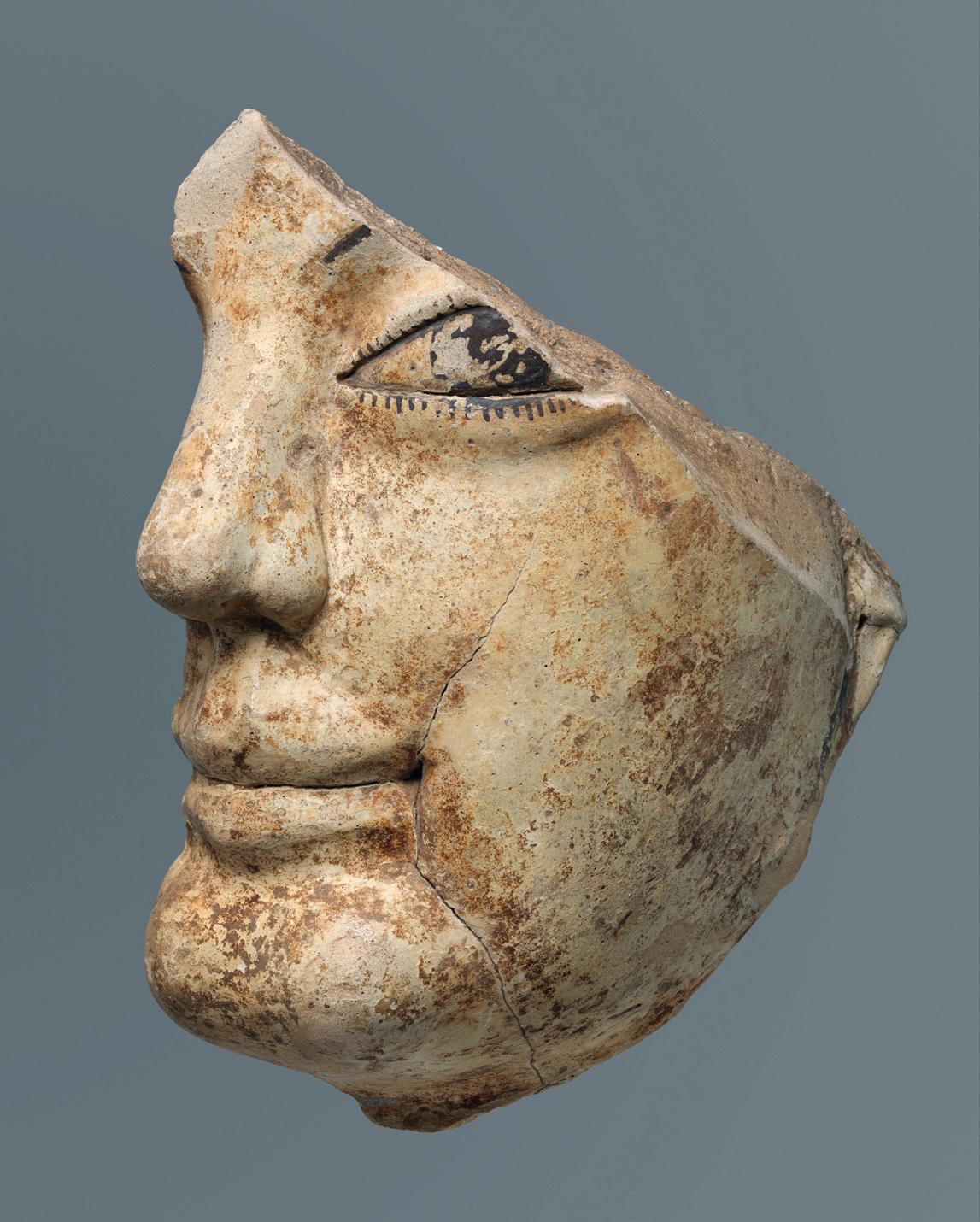

Plate with relief decoration of two philosophers debating, eastern Mediterranean, AD 500–600.

From the J. Paul Getty Museum: “Two seated philosophers, labeled Ptolemy and Hermes, engage in a spirited discussion. The scene has been interpreted as an allegory of the debate between Myth and Science: Ptolemy, the founder of the Alexandrian school of scientific thought, debating Hermes Trismegistos, a deity supporting the side of myth. The woman on the left, gesturing and partaking in the exchange, is identified as Skepsis. Above the two seated men, an unidentified enthroned man is partially preserved.”

academic philosophy as arid and uninteresting: “The only critique of a philosophy that is possible and that proves anything, namely trying to see whether one can live in accordance with it, has never been taught at universities; all that has ever been taught is a critique of words by means of other words.”3

3 Nietzsche, Untimely Meditations, “Schopenhauer as Educator,” #8.

As we understand the disciplines of philosophy and intellectual history today, Diogenes Laertius practiced neither, nor was he much of a literary stylist. But Diogenes was a man on a mission, and he had the ingenuity and diligence to carry it out.

The author compiled a variety of information about all the philosophers for whom he had material—eighty-two, as it happened. All the chosen were Greek or wrote their works in Greek, since Diogenes took it as axiomatic that not only all philosophy but “the human race itself” began with the Greeks and not the barbarians (be they Persian or Egyptian). In addition to summarizing key doctrines, Diogenes offers a sequence of short biographies—the most extensive set we possess.

The author’s voice is direct, generally plain, even impassive—though a dry sense of humor is also at play. He appears as a stockpiling magpie, leaving little out if it fits with his own apparent fascination with whether, and how, the lives of philosophers squared with the doctrines they espoused.4 Evidently interested in odd and amusing anecdotes, the more controversial the better, Diogenes sometimes notes the bias of his sources, but only rarely does he make an effort to evaluate their plausibility or the authenticity of the letters and other documents he reproduces. Although he obliquely comments on his Lives through a series of epigrams by others and poems of his own, filled frequently with puns and wordplay meant to amuse, he almost never praises or criticizes directly the characters he describes, nor does he venture any unambiguous opinion of his own about how one might best undertake philosophy as a way of life. His philosophical views (if he had any) are obscure.

The treatment of individual philosophers is uneven, ranging from an interminable list of categorical distinctions in the chapter on Plato to the verbatim citation of several works by Epicurus in his chapter on that philosopher. Some chapters are barely one paragraph long; others go on for pages. Sometimes a reader feels as if the author had simply dumped his notes on a table.5 Recent research suggests Diogenes may have died before he was able to organize a definitive version of his text, which would explain some of the

4 It is telling that perhaps his most extensive and explicitly critical treatment of a philosopher occurs in the case of Bion of Borysthenes, whose superstitious piety at the end of his life flagrantly contradicted the outspoken atheism he had espoused previously: see the poem at 4:55–57.

5 Diogenes’ presentation recalls other published notes (hypomnemata) from the same period, as described by Pierre Hadot, The Inner Citadel: The Meditations of Marcus Aurelius, trans. Michael Chase (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998), 32.

JAMES MILLER

lacunae and inconsistencies careful readers will notice.6 Yet even if the overall order of the books and some of the biographies was still unsettled at the time of his death, the text as we have it is never haphazard, since the material on individual philosophers is sorted more or less carefully into sections on genealogy, anecdotes, apothegms, doctrines, key works, and (almost always) a necrology, just as each of the work’s ten books is more or less plausibly organized by schools and lines of putative succession.

As a result of this encyclopedic format, it has long been the habit of most scholars and ordinary readers to dip into Lives of the Eminent Philosophers as needed, treating it like a reference work (however strange and unreliable).

But if instead one reads the entire text straight through (as there is some evidence the author intended), a not unwelcome bewilderment descends.

Despite some rough parts and missing passages, we behold a meticulously codified panorama of the ancient philosophers. Through the eyes of Diogenes, we watch them as a group living lives of sometimes extraordinary oddity while ardently advancing sometimes incredible, occasionally cogent, often contradictory views that (to borrow a phrase from Borges) “constantly threaten to transmogrify into others, so that they affirm all things, deny all things, and confound and confuse all things”—as if this parade of pagan philosophers could only testify to the existence of “some mad and hallucinating deity.”7

It has proven impossible to determine the exact dates of Diogenes Laertius. Since the author makes no mention of Neoplatonism, which began to flourish in the latter half of the third century AD, and since he discusses nobody born after the second century AD, experts have tentatively concluded that he lived in the first half of the third century AD.

Equally uncertain is the reason for the text’s survival: if Diogenes Laertius had readers in his own lifetime, we don’t know who they were. The manuscript may well have been published only posthumously, prepared by a scribe forced to work with unfinished material. No one knows how many copies were initially made. Unlike the corpus of Plato, which was carefully preserved by his school, or the treatises of Aristotle, which came to be

6 This research is summarized by Tiziano Dorandi in his essay on the manuscript tradition—see page 577.

7 Jorge Luis Borges, “The Library of Babel,” in Collected Fictions, trans. Andrew Hurley (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), 117.

widely read, studied, and copied in antiquity, it’s as if the manuscript had been preserved by a quirk of fate, just like the wall paintings in Pompeii (or the papyrus rolls of the Epicurean philosopher Philodemus in nearby Herculaneum).

Modern philologists have spent careers examining the scant evidence for more clues about Diogenes and the provenance of his text. Some of this research has focused on an effort to reconstruct a Greek text as close as possible to the (lost) original manuscript. Other research has examined the sources Diogenes consulted. As one scholar dryly remarked, “The relation of all this work to the Laertius problem as a whole has been strikingly expressed in a statement of Richards: ‘I have confined myself mainly to minutiae, with which it seems comparatively safe to deal.’”8 (In his doctoral work on the text as a young philologist, Nietzsche focused on just such minutiae.)

The earliest surviving references to Diogenes appear in works by Sopater of Apamea (fourth century) and Stephanus of Byzantium (sixth century). But it was only centuries later that the text became better known in the West, at first through a Latin translation by the Christian monk Ambrogio Traversari (1386–1439), and then through the first print editions of the Greek text.

Despite their obvious import, the biographies in Diogenes have long chagrined modern scholars, not because they are unsourced but because of their sheer number—and their sometimes amazing contents.

For example, his life of Pythagoras gives four different versions of how that philosopher died, citing three sources: he died fleeing a fire; he died in combat; he starved to death; and then this:

When he arrived in Italy, he built an underground chamber and instructed his mother to commit to writing everything that occurred, and at what time, and then to send her notes down to him until he came back up. This his mother did. And after a time Pythagoras emerged, withered and skeletal; entering the assembly, he said that he had come from Hades; he even read aloud what he had experienced there. Shaken by what he said, the people wept and wailed and were so convinced Pythagoras was a god that they sent their wives to him in the hope they might learn some of his doctrines. These were called the Pythagorizusae (Women Who Followed Pythagoras). So says Hermippus.

8 Hope, The Book of Diogenes Laertius, quoting Herbert Richards, “Laertiana,” Classical Review 18 (1904): 340–46.

JAMES MILLER

Lives glories in the deadpan reproduction of this kind of lore, some of it slyly deflationary, all of it offered in disorienting abundance.

A general picture of the philosopher as a social type nevertheless starts to emerge. He (with one or two exceptions, the philosopher is a man) is an imposing figure, often adept at argument, and generally interested in questions about the order of the world, the best way to live, or both. Absentmindedness is frequently noted, starting with Thales, along with an indifference to hygiene—body lice are a common malady; he is often a stranger to conventional behavior and customary beliefs, and his utterances are sometimes inscrutable.

A representative sample of anecdotes and odd apothegms: When asked what knowledge is the most necessary, Antisthenes said, “How to rid oneself of the need to unlearn anything”; when masturbating in the marketplace, a shameless act that made him a cynosure, Diogenes the Cynic said, “If only one could relieve hunger by rubbing one’s belly”; Carneades let his hair and fingernails grow, so single-minded was his devotion to philosophy; Pyrrho took as an example of perfect tranquillity a pig in a ship eating calmly in the midst of a raging storm; Xenocrates was so infallibly honest that he was allowed to give unsworn evidence in courts; Chrysippus, a Stoic of unrivaled industriousness and quickness of wit, was renowned for his copious use of citation, “with the result that in one of his books he copied out nearly the whole of Euripides’

A group of men pushing philosophers toward a fire fueled by burning books. Engraving attributed to Marco Dente, c. 1515–1527.

Medea; and when someone holding the book was asked what he was reading, he replied, ‘Chrysippus’ Medea.’”

The cumulative effect of such details is to underline the eccentricity of the philosopher as a social type and of philosophy as a way of life. But whereas Plato’s enchanting dramatizations of the transcendental moral perfection of Socrates still lead otherwise skeptical readers to suspend disbelief, the accounts in Diogenes, often allegorical in nature, occupy a playful twilight zone between fact and fiction: they seem designed both to fascinate and to provoke incredulity.

Then again, perhaps the real reason for the promiscuous citation of strange stories and conflicting authorities is to confirm the fame of the figure in question. After all, the work’s objects of interest are not just any old philosophers, but only those who are eminent. And what makes someone famous is, in part, the number of legends that surround him. Those prove eminence.

Diogenes thus starts his biography of Plato with a genealogy linking him to an Olympian deity and the legendary lawgiver Solon, followed immediately by an account of his virgin birth:

Plato, son of Ariston and Perictione—or Potone—was an Athenian, his mother tracing her descent back to Solon. For Solon’s brother was Dropides, and Dropides was the father of Callaeschrus, who was the father of Critias (one of the Thirty) and of Glaucon, who was the father of Charmides and Perictione, by whom Ariston fathered Plato. Thus Plato was in the sixth generation from Solon. Solon himself traced his descent to Neleus and Poseidon, and his father is said to have traced his descent to Codrus, son of Melanthus; both, according to Thrasylus, trace their descent to Poseidon. Speusippus in Plato’s Funeral Feast, and Clearchus in his Encomium on Plato, and Anaxilaides in his second book On Philosophy say that there was a story in Athens that Ariston tried to force himself on Perictione, who was then in the bloom of youth, and was rebuffed; and that when he ceased resorting to force, he saw a vision of the god Apollo, after which he abstained from conjugal relations until Perictione gave birth.

The biographies of Plato in modern textbooks simply omit such information, yet these details offer vivid evidence of how Plato came to be called “divine”—and hence help to explain how his writings became as consecrated as anything in Jewish or Christian scripture.

In composing his biographies, Diogenes, not unlike Plutarch, the most distinguished among the ancient biographers, gave pride of place to emblematic anecdotes. As Plutarch explained at the outset of his life of Alexander, “It is not histories I am writing, but lives; and the most glorious deeds do not always reveal the working of virtue or vice. Frequently, a small thing—a phrase or flash of wit—gives more insight into a man’s character than battles where tens

JAMES MILLER

of thousands die, or vast arrays of troops, or sieges of cities. Accordingly, just as painters derive their likenesses from a subject’s face and the expression of his eyes, where character shows itself, and attach little importance to other parts of the body, so must I be allowed to give more attention to the manifestations of a man’s soul, and thereby mold an image of his life, leaving it to others to describe the epic conflicts.”9 Diogenes seems similarly to assume that a vignette or a telling anecdote may reveal more about the essential character of a philosopher than the canonic writings that generations have intensively studied.

In any case, it is Diogenes Laertius alone who remains our main source for the lives—and legends—of most Greek philosophers.

The many doctrinal excerpts—what classicists call “doxography”—present problems of their own in the work of Diogenes Laertius. While most modern scholars largely ignore the tall tales in his Lives, they have never ceased to mine his text for precious evidence of the doctrines put forth by a large number of ancient philosophers and the schools they founded. For the doctrines of some—the Stoics and the school of Epicurus—Diogenes Laertius is a primary or our only source. In some cases it is hard to be sure how reliable his extracts are, since many of the works he cited have been lost. Where experts agree that an extract is genuine, it is hard to be sure how to interpret material presented more or less out of context.

Above all, Diogenes represents a standing challenge to many modern accounts of ancient philosophy. John Cooper, in Pursuits of Wisdom: Six Ways of Life in Ancient Philosophy from Socrates to Plotinus (2012), narrows in on what he calls “mainline” philosophers—theoreticians who stress the role of reason and the capacity to reason in philosophy as a way of life. In a footnote, Cooper denigrates the importance of spiritual exercises as a constitutive component of ancient philosophy and on the conversion to a specific ancient philosophy as an existential choice; it’s as if, for him, philosophy just is a reasoned commitment to a system of reasonable doctrines—or it isn’t really philosophy at all.10

But an unprejudiced reading of Diogenes’ Lives suggests that a one-sided emphasis on the capacity to reason as the sine qua non of ancient philosophy is hopelessly anachronistic.

9 Plutarch, “The Life of Alexander,” translation by Pamela Mensch.

10 John Cooper, Pursuits of Wisdom: Six Ways of Life in Ancient Philosophy from Socrates to Plotinus (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2012), see esp. 18–19n, where his target is Pierre Hadot.

Sometimes joining one of the philosophical schools Diogenes describes involved a suspension of conventional beliefs, and sometimes a suspension of disbelief (as witness the legends surrounding many of the most charismatic founding figures of some major philosophical schools). Sometimes it hinged on the ability to make logical arguments. But sometimes it entailed ritualized regimens, or the memorization of core doctrines, or simply the emulation of an exemplary (if perhaps mythic) individual philosopher (as witness Pythagoras, Empedocles, Socrates, Diogenes the Cynic, Pyrrho, and Zeno of Citium). In his survey of ancient philosophical doctrines, Diogenes himself makes no effort to quarantine what seems purely rational from what seems superstitious, imaginative, dogmatic, or rooted in systematic doubt rather than reasoned knowledge. Instead of confirming the central importance of the sort of rationality vaunted by some Greek philosophers, such as Plato, Aristotle, and Chrysippus, the work of Diogenes, taken as a whole, rather illustrates “the whimsical constitution of mankind, who must act and reason and believe,” as Hume once put it, “though they are not able, by the most diligent enquiry, to satisfy themselves concerning the foundation of these operations, or to remove the objections, which may be raised against them.”11

In this way the work of Diogenes willy-nilly poses anew the invaluable question What is philosophy?

The goal of this edition has been to render Diogenes into an English prose that is fluent yet faithful to the original Greek. Throughout, Pamela Mensch has avoided easy glosses in English of passages that are inherently hard to fathom in the original Greek. The annotation is aimed at the general rather than specialist reader, and explains the various references to people, places, practices, and countless mythological characters as they occur.12

11 David Hume, An Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, sect. XII, 128.

12 The notes avoid commenting on various possible readings of the Greek text, or on the philosophical substance of the various views that Diogenes reproduces. Variant forms of the information found in Diogenes are cited only sparingly. Readers interested in a more comprehensive annotation of the text, including the varied extant classical sources for specific epigrams, textual excerpts, or legends and lore found in Diogenes, should consult the new critical edition of the Greek text prepared by Tiziano Dorandi, Diogenes Laertius: Lives of Eminent Philosophers (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2013). See also the copious scholarly annotation in the French edition prepared under the direction of Marie-Odile Goulet-Caze, Diogène Laërce: Vies et doctrines des philosophes illustres (Paris: Le Livre de Poche, 1999); in the Italian translation edited by Marcello Gigante, Diogene Laerzio: Vite dei filosofi, 3rd ed. (Bari: Laterza, 1987); and the sparser, but still helpful, notes on sources in the Loeb Classical Library edition of the Greek, with an English translation by Robert D. Hicks (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1925).

JAMES MILLER

The text of Diogenes’ Lives comes down to us through a manuscript tradition roughly two thousand years long. In the process of copying and recopying the manuscripts, errors and omissions have inevitably occurred. Modern editors have attempted to correct the text by removing erroneous additions and restoring passages that they believe have been lost. Our translation marks these editorial interventions using two devices. Braces—like these: {/}—are used to indicate text that is in the manuscript tradition but which we, following other modern editions, regard as corrupt. Angled brackets (</>) indicate text that is not in the manuscripts but has been introduced by editors in an attempt to reconstruct what Diogenes’ original text might have said; in cases where we are uncertain how the text should be reconstructed, we put ellipses within those angled brackets.

SocratesAristotle

Works by Lui Shtini from the series The Matter of an Uncertain Future, 2011. Pencil on paper, 36 x 28 cm.

The letters of Epicurus preserved in Book 10 present a different kind of editorial challenge. Modern scholars generally agree that certain passages in these letters are genuine parts of Diogenes’ text, but not genuine parts of Epicurus’ letters. Rather, these passages are thought to represent a later commentary on the letters, which was incorporated into the text of the letters from which Diogenes transcribed them. Such passages of commentary have been italicized and enclosed in square brackets.

If an unfamiliar proper name mentioned in a section of the text for the first time is not given a footnote, then the person mentioned usually is someone whom Diogenes Laertius is using as a source. The Glossary of Ancient Sources, which starts on page 634, will offer more information on such people.

The selection of essays that follows the translation will give readers a sample of some of the latest scholarship in the field.

Mensch has worked from the new, authoritative Greek text established by Tiziano Dorandi and published by Cambridge University Press—with one significant exception. As Dorandi points out, there are no chapter headings in the most important extant Greek manuscripts for the parts of the text that concern an individual philosopher, perhaps a sign that Diogenes wished his text to be regarded as a whole rather than as a series of separate chapters on individual philosophers. In order to make the work easier for ordinary readers to approach, we have nevertheless followed the traditional convention of assigning the names of individual philosophers to the relevant parts of the text where each is discussed.

In commissioning and reviewing the essays, I have been assisted by James Allen, Dorandi, Anthony Grafton, A. A. Long, and Glenn Most. I have asked the contributors to keep in mind lay readers, but some of the philological and philosophical issues at stake are fairly technical. Not every reader will be interested in every essay.

The notes to the text come from several hands. James Romm annotated the historical references, while Jay Elliott focused on philosophical notations. Madeline Miller (a novelist by choice and a classicist by training, who is no relation to the present writer) annotated most of the mythological references with help from Kyle Mest.

Trent Duffy copyedited the text and notes and served as production editor during the long process of turning this complicated manuscript into a book. In editing the essays, I also had the valuable assistance of Prudence Crowther.

The many images and maps that accompany the main text have been selected by Timothy Don. Since these images are meant to illustrate the ongoing influence of many of the philosophical anecdotes compiled by Diogenes, we have

JAMES MILLER

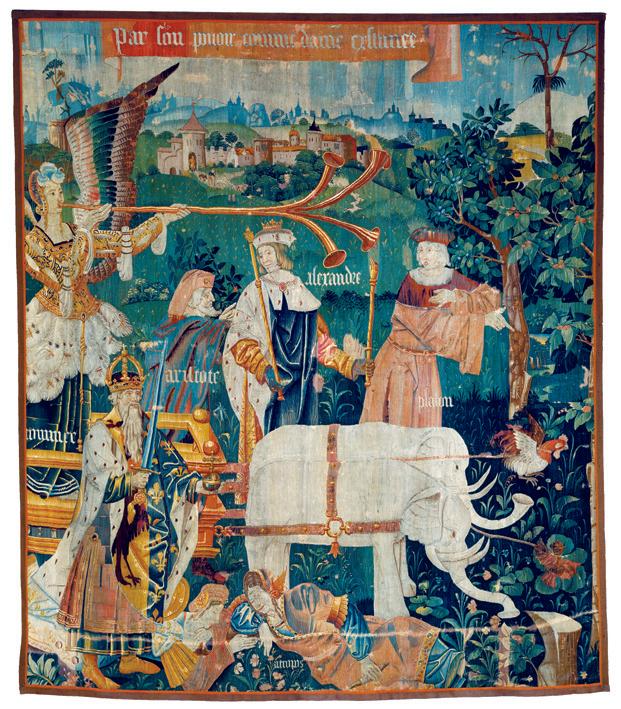

The Triumph of Fame over Death, South Netherlandish, c. 1500–1530.

The winged figure of Fame, riding in a chariot pulled by a team of white elephants and sounding a trumpet, heralds the appearance of four famous men: two philosophers, Plato and Aristotle, and two rulers, Alexander the Great (bearing a golden scepter) and Charlemagne (lower left). Death, symbolized by the two female figures, is trampled underfoot.

included material that is modern as well as ancient. The book was designed by Jason David Brown.

Our common goal has been to make Lives as accessible as possible to English-speaking readers—and at the same time to convey some of the essential strangeness of what philosophy once was, in hopes that readers may wonder anew at what philosophy might yet become.