Beginning Programming with Java For Dummies 6th Edition

Barry Burd

https://ebookmass.com/product/beginning-programming-with-java-fordummies-6th-edition-barry-burd/

ebookmass.com

Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

Print publication date: 2018

Print ISBN-13: 9780198827375

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2018

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198827375.001.0001

Title Pages

Jeffrey A. Auerbach (p.i) Imperial Boredom (p.ii) (p.iii) Imperial Boredom (p.iv) Copyright Page

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of

Page 1 of 2

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Jeffrey A. Auerbach 2018

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

First Edition published in 2018

Impression:1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2018939480

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Access brought to you by:

Page 2 of 2

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

Print publication date: 2018

Print ISBN-13: 9780198827375

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2018

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198827375.001.0001

Dedication

Jeffrey A. Auerbach (p.v) For Dalia (p.vi)

Access brought to you by:

Page 1 of 1

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

Print publication date: 2018

Print ISBN-13: 9780198827375

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2018

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198827375.001.0001

(p.vii) Acknowledgments

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

Second books, I have discovered, can take a long time. This project began at Yale University in 1996 in the most serendipitous and unexpected of ways, when

Oxford History of the British Empire. In the midst of that

Elisabeth Fairman, Curator of Rare Books and Manuscripts at the Yale Center for British Art, brought to my attention a small diary she had recently acquired, written by a little-known Lieutenant-Colonel in the British Army who had served in southern Africa in the late 1840s, in which he had drawn some sketches and watercolors of the people and scenery around him. It was in the course of reading his account of his time in the Cape Colony that I first encountered

Since then, my research has taken me to, and been funded by, institutions around the globe. These include the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut, and the Henry E. Huntington Library in San Marino, California, both of which offered me research fellowships in 1997, and the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich, where I was a Caird Research Fellow in 2004. I am grateful to all three libraries for their assistance, and especially to Amy Meyers, Director of the Yale Center for British Art but formerly Curator of American Art at the Huntington, who let me audit a seminar she was teaching and encouraged me to pursue my interest in early European representations of the East. I must express my appreciation as well to the curators, staff, and archivists at the British Library, the National Archives, the National Army Museum, the Victoria & Albert Museum, and the Wellcome Library, all in London; the State Library of New South Wales and the Australian National Maritime Museum in Sydney; the National Library of Australia in Canberra; and

Page 1 of 3

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

the State Library of Tasmania and the Allport Library in Hobart. Special thanks go to David Hansen for deepening my understanding of the art of John Glover and the Australian picturesque with a personalized tour of the Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery where he was Senior Curator. My thanks also go to the

Library, and to the Honnold Library in Claremont and the Young Research Library at UCLA, both of which granted me borrowing privileges.

When it comes to financial support for this project, no one was more generous, over a longer period of time, than Stella Theodoulou, longtime Dean of the College of Social and Behavioral Sciences at California State University Northridge. For a decade, amidst considerable budgetary constraints, she found ways to support faculty research and conference participation. In my case this included the annual meeting of the American Historical Association in Boston

2001; the Australasian Modern British History Association meeting in Canberra

(p.viii) State of Mind: Articulations of British Culture in

Studies in Berkeley in 2013 and Las Vegas in 2015; and the North American

International Interdisciplinary Conference on Boredom in Warsaw, both in 2015. The comments and suggestions from those in attendance helped sharpen my analysis enormously. Likewise for the lectures I delivered at the Humanities Center at the City College of New York in 2001, and the University of Pittsburgh in 2005. I also benefitted immeasurably from a university sabbatical leave fellowship in 2012. There is simply no substitute for uninterrupted time, and creativity is all but impossible without it. In an academic world that is increasingly driven by short-term results, it is reassuring to know, and worth recognizing, that there are those who still support long-term research projects. My gratitude also goes to Matt Cahn, Interim Dean of the College of Social and Behavior Sciences at California State University Northridge, for a summer research stipend to acquire many of the images reproduced in this book.

Some of the ideas and evidence presented here first appeared in article form in

Journal

The British Art

The Journal of Australian Colonial History 7 (2005):

Common Knowledge

indebted to the editorial and production team at Oxford University Press, especially Stephanie Ireland and Cathryn Steele.

Page 2 of 3

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Numerous scholars have referred me to sources, offered suggestions, listened patiently as I worked through arguments, commented on chapters, or in some cases helped me decipher nineteenth-century longhand. They include Jordanna Bailkin, Stephanie Chasin, Paul Deslandes, Nadja Durbach, Michael Fisher (who also very kindly invited me to dinner in London), Doug Haynes, Peter Hoffenberg, Maya Jasanoff, Tom Laqueur, Philippa Levine, John MacKenzie, John McAleer, Susan Matt, Thomas Metcalf, Tillman Nechtman, Erika Rappaport, Romita Ray, Jenni Siegel, Priya Satia, Lisa Sullivan, Michelle Tusan, and Amy Woodson-Boulton. At Scripps College, Eric Haskell encouraged me years ago to think about the relationship between text and image. Several of my colleagues at California State University Northridge offered valuable feedback, including Tom Devine, Richard Horowitz, Nan Yamane, and Chris Magra. Susan Fitzpatrick, Patricia Juarez-Dappe, Miriam Neirick, and Josh Sides offered support and encouragement in other ways. I owe a special debt of gratitude to Adam Phillips, who graciously gave me an hour of his time in his Notting Hill office to discuss the underlying psychology of boredom. And, as has been the case throughout my academic career, my greatest intellectual and professional debts are to Linda Colley and David Cannadine, who have always made time for me, and whose imprint on my work is profound and greatly appreciated.

(p.ix) Needless to say, I could not have made it through this process without the support of dear friends. These include, as always, Keith Langston, as well as, more locally, Frank Bright, Jonathan Brown, Hao Huang, Chuck Kamm, Steve Moss, David Myers and Nomi Stolzenberg, Brian Spivack, Mark Taylor, and Larry Weber. I am especially grateful to Linda Bortell, who has been willing to listen to me talk about boredom whenever I have wanted to, and to Andra Becherescu, who never seems to get bored.

Finally, my thanks go to my parents for their unwavering support, with special gratitude to my father for his critical reading of several chapters and to my mother who drew on years of editorial experience to flag some infelicitous phrases; to my daughter Dalia, who is never boring; and to Nancy, who, amidst her own academic career, indulged me and my obsession with boredom for many years. (p.x)

Access brought to you by:

Page 3 of 3 PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

Print publication date: 2018

Print ISBN-13: 9780198827375

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2018

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198827375.001.0001

(p.xiii) List of Figures

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

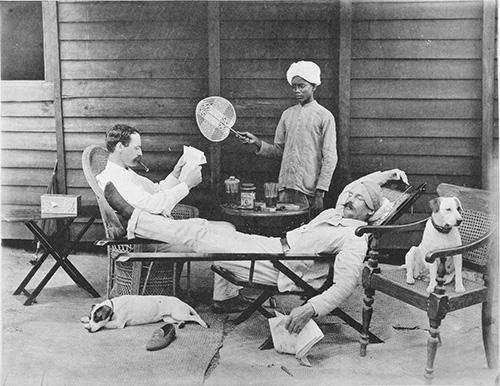

0.1. A. G. E. Newland, The Long, Long Burmese Day

The Journal of the Photographic Society of India Vol. V: 3 (March 1892), after p. 38. © British Library. 2

1.1.

Ship Wrecked on a Rocky Coast (c 50). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 13

1.2.

A general chart for the purpose of West Indies or the Pacific Ocean (London: Charles Wilson, 1852). State Library of New South Wales, Mitchell Map Collection. 34

1.3.

Illustrated London News Vol. 4 (13 April 1844): 229. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. 35

1.4. Cabin Scene, Man Relaxing in a Chair, with His Feet Up (1820). © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London. 36

1.5.

Ascension Island (c.1815). © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London, Caird Collection. 37 1.6.

Illustrated London News Vol. 14 (20 January 1849): 41. Courtesy of The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. 39

1.7.

Views on the North Coast of Australia (1802). National Library of Australia. 40

2.1. Thomas Sutherland (b. 1785) after Lt.-Col. Charles Ramus Forrest The Taj Mahal, Tomb of the Emperor Shah Jehan, from A Picturesque Tour along the Rivers Ganges and Jumna, in India (London: L. Harrison for Rudolph Ackermann, 1824). © British Library. 45

Page 1 of 3

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Page 2 of 3

2.2.

Road, from The Kafir Wars and the British Settlers in South Africa (London: Day and Son, 1865). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 58

2.3. Mount

Misery, Waterkloof, from The Kafir Wars and the British Settlers in South Africa (London: Day and Son, 1865). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 59

2.4. View of the Keiskama Hoek, from Scenes in Kaffirland (London, 1854). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 60

2.5. c.1814), View across Sydney Cove from the Hospital towards Government House. Natural History Museum, London. 64

2.6. Thomas Watling [attrib.], A Direct North General View of Sydney Cove (1794). Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales. 64

2.7. Country NW of Tableland (c.1846). National Library of Australia. 67 (p.xiv) 2.8. View from Rose Bank (1840). National Gallery of Australia. 71

2.9. My Harvest Home (1835). Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. 72

3.1. The Viceroy Lord and Lady Curzon Tiger Hunting (1902). © British Library. 80

3.2. Garnet Wolseley, (Westminster: Archibald Constable, 1903). 83

3.3. Lord Auckland Receiving the Rajah of Nahun, from Portraits of the Princes & People of India (London: J. Dickinson & Son, 1844). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 88

3.4. Our

Joint Magistrate, from Curry & Rice (on Forty Plates); or The Ingredients (London: Day & Son, [1859]). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 95

3.5. Vanity Fair (27 March 1875). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 98

3.6. Illustrated London News Vol. 92 (3 March 1888): 222. The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. 100

3.7. Sir Frank Swettenham (1904). © National Portrait Gallery, London. 102

4.1.

Punch, Vol. 98 (Christmas Supplement); Harvard University Library. 109

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

4.2. Pen and Pencil Reminiscences of a Campaign in South Africa (London: Day & Son, 1861). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 115

4.3. Pensioners on Guard (1852). National Library of Australia. 122

4.4. The Delhi

Sketch Book Vol. 3, No. 10 (1852): 101. © British Library. 124

4.5.

Stray Leaves from the Diary of an Indian Officer (London: Whitfield, Green & Son, 1865), after p. 18. State Library of New South Wales. 130

4.6.

Stray Leaves from the Diary of an Indian Officer (London: Whitfield, Green & Son, 1865), after p. 24. State Library of New South Wales. 130

4.7.

from Scenes in Kaffirland (London, 1854). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection. 132

4.8. East India Company Recruiting Broadsheet c.1810. Alamy. 135

5.1. Melbourne Punch, 2 February 1860. State Library of New South Wales. 143 (p.xv) 5.2. The Daughter of Gen. Ritherdon, Madras (1863). Hulton Archives/Getty Images. 146

5.3. Anna Jameson (1844). © British Library. 157

5.4. Florishing [i.e. flourishing] State of the Swan River Thing (London: Thomas McLean, 1830). National Library of Australia. 159

5.5. S. T. Gill, The Shepherd. State Library of New South Wales. 161

5.6.

Library of Australia. 162

5.7. The Life and Times of The Marquis of Salisbury (J. S. Virtue, 1895). 163

5.8. Victoria Terminus, Bombay (1887). 169

5.9.

Views of Calcutta and its Environs (London, 1826), Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection 170

5.10. A Half-Timbered House in Simla. © British Library. 171

6.1. The Remnants of an Army (1879). © Tate, London. 186

(p.xvi)

Access brought to you by:

Page 3 of 3

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

Print publication date: 2018

Print ISBN-13: 9780198827375

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2018

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198827375.001.0001

(p.xvii) List of Colour Plates

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

1. Life in the Ocean Representing the Usual Occupations of the Young Officers in the Steerage of a British Frigate at Sea (1837). © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

2. An Interesting Scene, On Board an East Indiaman, Showing the Effects of a Heavy Lurch, after Dinner (1818). Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

3. Indiaman, 1000 Tons (Entering Bombay Harbor) (c.1843). © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

4. Tahiti Revisited (c.1775). © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

5. Tom Raw Forwarded to Headquarters, frontispiece from Tom Raw, the Griffin: A Burlesque Poem in Twelve Cantos (London: R. Ackermann, 1828). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

6. Calcutta from Twenty-Four Views in St. Helena, The Cape, India, Ceylon, the Red Sea, Abyssinia, and Egypt (London: William Miller, 1809). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

7. Cape Town, from the Camps Bay Road, from The Kafirs Illustrated (London, 1849). Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection.

8. View of Port Bowen, Queensland (1802). © National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

9. (1838), Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery.

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

10. John Glover, Hobart Town, from the Garden Where I Lived (1832), Dixson Galleries, State Library of New South Wales.

11. Robert Provo Norris (d. 1851), [Landscape with Fort as Seen from Riverbank]. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

12. Robert Provo Norris, Eno, A Kaffir Chief. Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Fund.

13. Poster for Huntley & Palmers Biscuits. Printed by W.H. Smith, 1891. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

14. (1842). Wellcome Library.

15. Berhampore, 1863. © British Library.

16. The Entrance of Port Jackson, and Part of the Town of Sydney, New South Wales (London: Colnaghi & Co., 1823). State Library of New South Wales.

(p.xviii)

Access brought to you by:

2 of

FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Imperial Boredom: Monotony and the British Empire

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

Print publication date: 2018

Print ISBN-13: 9780198827375

Published to Oxford Scholarship Online: November 2018

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780198827375.001.0001

Introduction

Jeffrey A. Auerbach

DOI:10.1093/oso/9780198827375.003.0001

Abstract and Keywords

Burmese Days and its portrait of the boredom and lethargy that characterized British colonial life in the 1930s, the introduction poses the question of when and why the British Empire became so the many and famous tales of glory and adventure, a significant and overlooked feature of the nineteenth-century British imperial experience was boredom and psychological origins, and summarizes the chapters that follow. It asserts that the empire came to be constructed as a place of adventure, opportunity, and picturesque beauty not so much because British men and women were seeking to escape from boredom at home, as has often been surmised, but because the empire lacked these very features.

Keywords: British Empire, boredom, ennui, George Orwell, Burmese Days, diaries, adventure, Enlightenment, individualism

In his 1934 novel Burmese Days, George Orwell produced a memorable portrait of the boredom, loneliness, and alienation that characterized life in Burma during the waning days of the British Empire. John Flory, the protagonist who and drink whisky. When, early in the story, Flory meets the District

Page 1 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

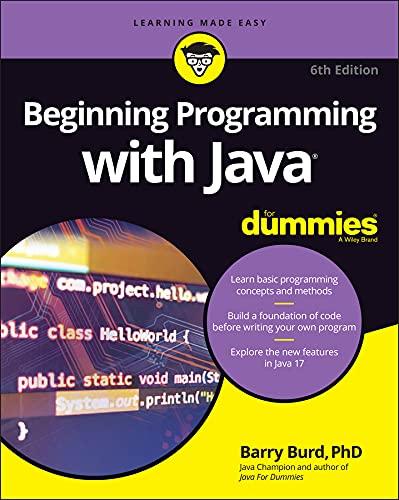

Superintendent of Police, the officer is standing on the steps of the club, rocking in 1

When did British India, of which Burma was a part, become such a melancholy and monotonous place (Fig. 0.1)? To what extent was the boredom Orwell 2 And if the British imperial experience was so dreary and disappointing, why was it so popular treasure rumored to have been left by King Solomon. Along the way they trek across deserts, climb mountains, hack their way through jungles, and fight for their lives, bravely defeating a ruthless tribal king and narrowly escaping from a dark chamber with enough diamonds to make them all rich. It is the archetypal Robinson Crusoe, to The Man Who Would Be King stories for boys with titles such as By Sheer Pluck: A Tale of the Ashanti War, to The Four Feathers in which a British officer redeems himself through courageous acts of endurance and derring-do in the Sudan, imperial fiction glamorized and romanticized the empire.3 Nor were the heroes only fictitious: real life exemplars include Walter Raleigh, James Cook, Robert Clive, David Livingstone, Cecil Rhodes, T. E. Lawrence, and end-of-empire supermen such as Lord Mountbatten and Edmund Hillary, whose achievements were celebrated and whose stories enthralled a nation.4 Even those historians who nevertheless acknowledged the ubiquity, if not omnipresence, of imperial heroes in literature and the arts.5

(p.2) Empire building has generally been framed in extremes. Some have portrayed it as a bold and glorious mission, designed to carry commerce and civilization to the furthest reaches of the globe. For others, it represents the imposition through military or economic power of a capitalist culture that resulted in the trampling of longstanding local customs and

Page 2 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Fig. 0.1. A. G. E. Newland, The Long, Long Burmese Day

The Journal of the Photographic Society of India Vol. V: 3 (March 1892), after p. 38. © British Library.

structures under the guise of the national interest.6 Scholars have tended to describe the men responsible for establishing and maintaining empire either as courageous heroes charting new lands and amassing great wealth; or, as pathetic misfits whose missions were beset with problems and who imposed culturally-bound norms and values that led to the destruction of indigenous peoples and their ways of life.7 They have characterized the work of colonial women in a similarly dichotomous fashion, emphasizing either their complicity in constructing a racialized view of the world, or their resistance to such stereotyping by subverting and critiquing European claims of superiority and objectivity.8 Even the revisionists, however, while demythologizing many of the same men and women whom the hagiographic approach exalted, have nonetheless taken for granted that imperial travelers lived exciting lives and had an enormous impact on the empire, however much their fame may have derived from the destruction they wrought.

In describing the British Empire in such bifurcated terms, scholars have tended to rely on the carefully edited writings of famous explorers such as Henry Stanley (p.3) and John Speke, self-promoting administrators including Lords Cromer and Curzon, renowned generals such as Charles Gordon and Herbert Kitchener, and intrepid women such as Mary Kingsley and Flora Shaw. Yet the distinguished writer James (now Jan) Morris, in Pax Britannica (1968), an

Jubilee in 1897, made the important point that men like Rhodes and Curzon millions of settlers, administrators, merchants, soldiers, and housewives.9 What of these men and women? What was it like to be a soldier on the frontier in South Africa, to trek through the jungles along the Zambezi, to accompany a colonial administrator to a hill station in India, or to be employed as a governess in Western Australia?

Imperial Boredom argues that despite the many and famous tales of glory and adventure, a significant and overlooked feature of the nineteenth-century British imperial experience was boredom and disappointment. Diaries, letters, memoirs, and illustrated travel accounts, both published and unpublished, demonstrate that all across the empire, British men and women found the landscape monotonous, the physical and psychological distance from home enervating, the routines of everyday life tedious, and their work dull and unfulfilling. After George Bogle, the Scottish adventurer and diplomat who undertook the first British mission to Tibet in 1774, finally met the Panchen Lama, he quickly grew

Page 3 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

tedious and uniform life I spent at Teshu Lumbo [the fifteenth-century monastery 10 And Mary Kingsley, who traveled to West Africa in the 1890s, carving her way through the Congo with verve and vitality, complained about having to eat the same kind of

11 Perhaps the Daily Telegraph put it best, and certainly most 12 Boredom, in short, was neither peripheral nor incidental to the experience of empire; it was central to it, perhaps even the defining characteristic of it.

Boredom is an emotional state that individuals experience when they find themselves without anything particular to do and are uninterested in their surroundings.13 Some of the earliest recorded uses of the word occur in Charles Bleak House Hard Times there no one knows, but Harriet Martineau, who toured Egypt in the 1840s,

14

Along with its corollary, ennui, boredom is most commonly associated with finde-siècle France.15

the (p.4) greatest fictional portrait of boredom in Madame Bovary, for whom 16 In Les Fleurs du Mal (1857), his contemporary, Charles Baudelaire, characterized boredom as the root of human evil, testifying to its growing influence in European life and literature. Perhaps no fictional character was more thoroughly bored though than Durtal in JorisThe Cathedral condition and coming to the conclusion that his boredom was actually twofold in

17 But the world-weariness that was endemic in late nineteenth-century French literature, as well as in The Picture of Dorian Gray

Burmese Days and, it will be seen, in numerous other less well-known writings about the British Empire. Rather, the expressions of imperial boredom reflect a sense of dissatisfaction and disenchantment with the

Page 4 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

immediate and the particular, and at times with the enterprise of empire more broadly, but not with life itself.

Scholars have endeavored to trace the origins of boredom as far back as ancient Greece and Rome, but most of the evidence suggests that boredom is a relatively modern construct that did not exist either as a word or a concept before the mideighteenth century. If people felt bored before then, they did not know it or express it.18 The emergence of boredom has instead been linked to relatively recent historical changes, notably the spread of industrial capitalism and the development of leisure time.19 society work was part and parcel of everyday life and leisure was not a separate

20 But during the eighteenth century work and leisure became distinct pursuits. The Industrial Revolution altered conceptions of time, mechanizing it, speeding it up, and transforming it into something that was always fleeting and must not be wasted.21 Leisure time, especially for a middleclass that began to define itself by its commitment to work, became dangerous and destabilizing, something that had to be filled with meaningful and improving activities.22 Meanwhile, leisure grew increasingly commercialized, as a veritable

23 Boredom, therefore, can be seen in part as a response to the absence of the new, the exciting, and the entertaining.

are, as the American Declaration of Independence proclaimed, fundamental

Locke wrote about in his Second Treatise of Government happens if an individual is not happy, since the right to pursue happiness at least hints at the possibility of achieving it? Boredom, in this context, emerges as one of the opposites, however ill defined, of happiness. Closely linked is the rise of individualism, the origins of (p.5) which have been traced to the late-medieval period, but which is also most often associated with the eighteenth century: the push for individual rights, the desire for a more affective marriage, and an increasing interest, particularly evident in Rousseau, in self-awareness and selffulfillment.24

expanding capitalist economy. The crystallization of the concept of boredom in the eighteenth century made possible a new way of relating to the world.

By the nineteenth century, however, a variety of more concrete social, cultural, and technological changes, many of them unique to the British Empire, were undermining the sense of novelty and excitement that had characterized earlier imperial activity. These include, ironically, improvements in navigation that

Page 5 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

enabled ships to sail further and out of sight of land longer than ever before; the spread of tourism and the proliferation of guidebooks that heightened expectations about the beauty of imperial landscapes and the grandeur of imperial ruins; and the increasingly bureaucratic and ceremonial nature of British rule, which inundated imperial administrators with paperwork and left them chafing against their diminished autonomy. Also important was the growth of British communities overseas, which grew progressively more isolated from indigenous people and customs. Increasingly, British men and women sought to re-create the very conditions they had left behind in a futile search for the familiarity of home, neither fully embracing nor entirely rejecting the newness and differences they encountered overseas. In settler colonies, such as South Africa and Australia, they built houses and churches to resemble English country villages.25 In the hill stations of India they replicated the same calendar of balls, teas, and parties that were the hallmarks of the London Season.26 And when artists sketched and painted imperial lands, they sought out picturesque landscapes that reminded them of the English Lake District.27 The sixteenthcentury empire may have been, as literary scholar Stephen Greenblatt has argued, about wonder and marvel, both real and imagined, but the nineteenthcentury empire was a far less exciting and satisfying project.28

Boredom also has psychological origins and significance. According to 29 can lead to self-sufficiency and creativity, but also frustration.30 In this respect boredom sheds light on a profound question that surfaced with great urgency in boredom serves as a defense against the annoyance of waiting, this was something British men and women did a lot of in the nineteenth century: waiting for a ship to arrive, waiting for a military posting, waiting for a meeting to take place. As David Carnegie, a young colonial official who died in Northern Nigeria in 1900 when he and a group of armed men were ambushed while trying to man, but I feel sure he was never on the Niger. The motto for this country ought 31 His annoyance over (p.6) away country in the Boer War is palpable. Only his confessions of boredom seem to keep his anger or sense of uselessness in check.

Boredom can also be seen as a crisis of unfulfilled or unacknowledged desire. In this way, boredom is intimately linked to expectations, which in the imperial context were heightened by propagandistic pamphlets, popular paintings and engravings, and self-serving memoirs. Hunters rarely found big game; diggers rarely struck gold. As it turns out, British men and women in the nineteenth

Page 6 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

unmet hopes and dreams and their uncertainty about when if ever they were

32 If, as Lars Svendson has pointed out, boredom frequently signals a loss of meaning, then this had enormous ramifications in the imperial context.33

travelers were so bored, why did they write about their experiences at all? The very fact that they kept diaries seems to imply that they regarded their lives as interesting and important. Keeping a diary, however, was a fashion of the age.

34 But more than just a way to fill time, or a method of record keeping, diaries of this sort may be 35 They provided a means and a need, perhaps, that may have been heightened in the colonial context when, as many scholars have pointed out, identities were being challenged and in flux.36 In this context, diaries were or could be a discourse about the self.37 They were also a means of imposing order on a disorderly world created by new experiences in unfamiliar places.38 It is important to acknowledge, however, that the act of writing a diary can constrain as well as liberate. A diary begs to be

existence implies that there is something worth writing on a daily basis. Yet, the diaries discussed in the chapters that follow reveal that there were many days when nothing worth noting occurred. Thus, keeping a diary forced diarists either to find something to write about, or else to acknowledge, in ways that they might not have in a memoir or guidebook, that there was very little of interest taking place.

Imperial Boredom explores these and other related issues through five thematic chapters that trace the experience of traversing, viewing, governing, defending, and settling the British Empire from the mid-eighteenth century to the early because that is how the empire began. As Jeremy Black has written, the British

39 This first chapter explores the normalization of ocean travel during the nineteenth century as navigation improved and the routes to South Africa, India, and Australia became more frequently plied. Prior to the (p.7) introduction of steamships in the 1840s and 1850s, the voyage from England to India took anywhere from three to six the small sailing vessels that were tossed about in every storm, the cramped and

Page 7 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

dirty cabins that had to be shared with rats, the two buckets of salt water, one worst part about the journey was the boredom: day after day out on the water with nothing to break up the monotony. At least through the first quarter of the nineteenth century, it was common for ships sailing to India or Australia to stop for fresh water and provisions, and passengers were thankful for the break at St. Helena or the Cape. Similarly, beginning in the 1870s, with the advent of the steamship and the opening of the Suez Canal, the journey not only became shorter; it had to be interrupted for frequent coaling stops. But for most of those traveling during the middle decades from about 1825 to 1875, the voyage was made nonstop and out of sight of land for almost the entire distance. Additionally, whereas in the eighteenth century amateur naturalists had been thrilled to make scientific observations, by the mid-nineteenth century most of what could be easily identified, such as the albatross, had been noted. In short, by the middle of the nineteenth century, ocean travel had indeed become more monotonous: it was less dangerous, routes were better known, there were few if any stops, land was rarely in sight, and there was little novelty in seeing birds and fish that had been seen and described before. Whereas in the seventeenth century a voyage to India was a treacherous journey into the unknown, by the mid-nineteenth century it had become a dreary interlude.

Chapter 2

lands, arguing that the picturesque was an aesthetic paradigm that concealed the monotony, hardship, and otherness of imperial places. The increase in travel opportunities in the nineteenth century brought a corresponding proliferation of tourist literature encouraging middle- and upper-class men and women to journey overseas in search of picturesque landscapes and ruins. Ironically, by privileging certain sites and vistas, the picturesque ideal rendered most of the empire boring and uninteresting as even the most impressive sites were rarely as spectacular or novel in person as they were in paintings and engravings.40 Moreover, the visual familiarity of iconic sites meant fewer opportunities to explore the unexplored. Even in India, with its remarkable array of historical and religious sites, the British described much of the terrain as monotonous. In part, this characterization of the landscape can be attributed to a sense of cultural superiority. While British travelers were clearly impressed with cities such as Banaras (Varanasi) and Cairo, they rarely failed to comment on the state of ruin in which they found the more famous buildings. But at least in India and Egypt the British acknowledged that there had once existed a great civilization. In other locations, such as South Africa and Australia, there were no ruins whatsoever, and so, except for a few scattered vistas, there was little that was deemed noteworthy. Thus it is important to analyze the complex interaction of aesthetic theory and perception, and especially the propagandistic qualities of the picturesque idiom employed by amateur and professional artists in both their public and private work.

Page 8 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

(p.8) Chapter 3 the Colonial Office in London to the lived experience of Governors-General and civil servants scattered around the globe, whose lives were increasingly dominated by mind-numbing meetings and dreary dispatches. Although the number of were

empire became noticeably more bureaucratic between the 1830s and the 1870s, as the British came to rely less on the support of indigenous rulers and more on their own centralized administrative rule.41 Even before the widespread use of the telegraph and typewriter, the volume of paperwork grew markedly, and governors especially, who relished the active and leisured lifestyle that characterized the aristocratic ideal, complained regularly in their private correspondence about the quantity of deskwork and the frequency of public duties such as hospital visits, school inspections, and state dinners.42 Moreover,

numbers of low- and mid-ranking civil servants who were sent to live and work in remote locations performing menial tasks. Historians have amply demonstrated how in the eighteenth century Britain developed a fiscal-military state.43 state are to be found at least as much in the nineteenth-century British Empire as in the Victorian post office, the court system, and the administration of the new Poor Law.44 In this way, Imperial Boredom of the empire, highlighting instead the limits on individual action and the impact

The situation was much the same for soldiers, the subject of Chapter 4. Although the story of the British Empire has often been told in terms of its military 45

although military heroism was part of the lore of the British Empire, by the midnineteenth century soldiers were spending much of their time sitting in tents in the heat with little to do but drink. Many soldiers, in fact, went years, and in some cases decades, without participating in so much as a skirmish. As the empire grew in size, there were more and more British soldiers stationed

following the invention of the repeating rifle, battles were shorter and more onesided. These changes in warfare, and the huge increase in references to boredom that resulted from them, also align closely with new definitions of masculinity, suggesting that the boredom soldiers expressed was at least partly related to their inability to demonstrate their bravery and physical prowess in the absence of hand-to-hand combat. In the end, many found themselves deeply disillusioned with imperial service. The well-known saying that war consists of

British officer stationed on the Western Front during the First World War, had its figurative origins in the nineteenth-century British Empire.

Page 9 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Finally, in Chapter 5, Imperial Boredom women who spent significant portions of their lives overseas. Many migrated voluntarily; others, like the Australian convicts, involuntarily. Some settled permanently; others (p.9) gave up and returned home. But time and again, these imperial travelers describe their experiences as not just dreary, but downright disillusioning. Led to believe that life in the empire would be full of opportunity, many of them instead found only the monotony of daily routine. John Henderson, for example, who traveled to Australia to become a pastoralist,

46 Life was particularly difficult for women, whether entertaining friends in the Indian hill stations or whiling away the hours in the Australian outback. The former suffered from vapid social rituals and prohibitions on contact with indigenous people; the latter from extreme isolation and loneliness. With few exceptions, women, regardless of their social class, had lots of leisure time; the difficulty was filling it. They read; they painted; and they gossiped with other women, assuming there were any around. But all the parties in the world could not make up for the boredom, and in remote locations especially, the same people met day after day to eat the same meals and exchange the same tired conversation.47 governesses, from gold diggers to bushwhackers, boredom was omnipresent.

To be sure, not everyone found the empire boring. Thus Imperial Boredom attempts to historicize boredom by investigating its contours: Who was bored and who was not? What places and situations were travelers likely to find boring, and was imperial travel different from other forms of travel, such as the European Grand Tour?48 When and why did boredom emerge as a characteristic of the imperial experience, and was there something uniquely boring about the empire, or was boredom such a common emotion (or affectation) for men and women of a certain social class at a particular time and place that anything might be boring?49 To what extent was boredom linked to the shift from an eighteenth-century empire of Nabobs to a more virtuous empire in the nineteenth century?50 This book, in short, attempts to explore the shape, functions, and contradictions of imperial monotony, contributing not just to understandings of the British Empire, but to the history of emotions, a field of inquiry still in its infancy.51

It must also be asked whether the empire was boring for those who were subjects of it: Indians, Maoris, Aborigines, Xhosa. Elspeth Huxley, who grew up ennui suggested that when the British Empire finally crumbled, its epitaph should be: 52 And Jamaica Kincaid, in A Small Place (1988), her

Page 10 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

lives a life of overwhelming and crushing banality and boredom and desperation

53

On the other hand, the Aboriginal experience with British settlers in Australia was a story of almost unmitigated pain and hardship.54 The closest this book will come to suggesting that indigenous people were bored by the empire will be to note that many Indians and Africans, especially in rural areas, actually had very little contact with British rule during the nineteenth century. Although important, a thorough analysis of this (p.10) issue is beyond the scope of this people they encountered and ruled. This is not to deny indigenous agency, but instead to recognize its potential uniqueness and difference.

Geographically, this book ranges widely, though it focuses most closely on India, Australia, and southern Africa. It has little to say about the British Empire in the Americas, although the experience of Anna Jameson (see Chapter 5), a British writer who traveled to Canada in 1836 to visit her estranged husband, Robert, who had been appointed chief justice of the province of Upper Canada, suggests that Canada could be as boring and disappointing as any other region.55

Winter Studies and Summer Rambles in Canada (1838), best known for its descriptions of the indigenous Indian communities near Lake Huron, which Jameson observed with great sensitivity.56 As to whether imperial monotony was characteristic of the French and German empires, that too is a matter for other

Instead, this book seeks to offer a history and sociology of boredom as it pertains

One of the benefits of using boredom as a lens through which to view the British imperial experience is to help reintegrate the empire, which one historian has

57 Historians have struggled to conceptualize the British Empire, especially at its height in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. To what extent was there a single or did actors on the periphery affect decisions that were made in the metropole?58 Perhaps there were multiple centers, it having been argued, for example, that India functioned as a sort of imperial sub-center within the Indian Ocean arena, with its coinage, labor, legal structures, and architectural styles influencing what the empire looked like from East Africa to South-East Asia.59 Historians have written of networks, connections, crossings, counterflows, fault lines, zones, and webs.60 61

Imperial Boredom argues emphatically that there was indeed a unifying experience for British men and women across the long nineteenth century, and that the ubiquity of imperial monotony delineates linkages and vectors not

Page 11 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

wholly disconnected from metropolitan culture, but not entirely related to it either.

Above all, Imperial Boredom suggests that the empire was constructed as a place of adventure, excitement, and picturesque beauty not just because men and women were seeking to escape boredom at home, but because the empire so often lacked these very features. There is a marked difference between the way writers and artists depicted the empire in their published works, and how they portrayed it in on-the-spot sketches, letters, and unpublished diaries. It was one thing for Fanny Parkes to write in the published account of her 1822 journey to

England, her happiness would have been complete; quite another when she revealed in a private letter a (p.11)

62 The fantasy and reality of empire were very different things, and therefore many of the sources scholars have traditionally relied on, including published memoirs, hagiographic biographies, illustrated travel narratives, commissioned art, and adventure-filled novels, need to be regarded as propaganda on behalf of empire.63 It is only when these sources are read against the grain, and in conjunction with a variety of unpublished and less well-known writings, that they disclose the monotonous underside of imperialism. Life in the colonies was not by definition boring. There were exciting moments, and

seems, as many or as often as the British would have liked. By focusing on the divergence between the fantasy and reality of empire, and by highlighting the propagandistic nature of imperial art and literature, this analysis seeks to help explain both the popularity and longevity of empire, as well as why so many men and women were dissatisfied with it.64

There are hundreds of books about the British Empire that focus on what happened; many of them also explain why. This book, based as it is largely on first-hand accounts, is very much about how people felt. In fact, one of its main contentions is that for countless men and women serving or settling the British Empire in the nineteenth century, very little actually happened. In this respect, Imperial Boredom seeks to revive a kind of biographical history; that is, to use individual stories to trace a historical transition through the prism of lived experience.65 This book is about individuals, but also about the times and places in which they lived, and the broader work of empire in which they were involved.

In 1883, J. R. Seeley, Regius Professor of Modern History at Cambridge, famously remarked in The Expansion of England that the British Empire 66 In the decades since he coined that famous phrase, historians have thoroughly explored the reasons for and motives

Page 12 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

social, intellectual, or religious.67 It might be better to say, however, that the British Empire developed in a fit of boredom.

Notes:

(1.) George Orwell, Burmese Days 29, 32, 70. For a similar portrayal, see Edward Thompson, An Indian Day (London: Alfred A. Knopf, 1927).

(2.) Orwell, 41.

(3.) See Graham Dawson, Soldier Heroes: British Adventure, Empire, and the Imagining of Masculinities (London: Routledge, 1994); Robert Dixon, Writing the Colonial Adventure: Race, Gender and Nation in Anglo-Australian Fiction (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995); Richard Phillips, Mapping Men and Empire: Geographies of Adventure (London: Routledge, 1997).

(4.) Berny Sèbe, Heroic Imperialists in Africa: The Promotion of British and (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2013); John M. Mackenzie, ed., Imperialism and Popular Culture (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1986).

(5.) Bernard Porter, The Absent-Minded Imperialists (Oxford: Oxford University

(6.) Compare, for example, Niall Ferguson, Empire: How Britain Made the Modern World (London: Allen Lane, 2002), with Mark Cocker, Rivers of Blood, (London: Jonathan Cape, 1998) and Basil Davidson, Nation State (New York: Random House, 1992).

(7.) Those in the first group include Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa, (New York: Random House, 1991); Peter Hopkirk, The Great Game: The Struggle for Empire in Central Asia (New York: Kodansha International, 1990); Karl E. Meyer and Shareen Blair Brysac, Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia (Washington, DC: Counterpoint, 1999); Kathryn Tidrick, Empire and the English Character (London: Tauris, 1992); Frank McLynn, Hearts of Darkness: The European Exploration of Africa (New York: Carroll and Graff, 1992); and Brian Thompson Imperial Vanities: The Adventures of the Baker Brothers and the Gordon of Khartoum (London: HarperCollins, 2002). Scholars in the second group include Mary Louise Pratt, Imperial Eyes (London: Routledge, 1992); Geoffrey Dutton, The Hero as Murderer: The Life of Edward John Eyre, Australian Explorer and (Sydney: Collins, 1967); I. F. Nicolson, The (Oxford: Clarendon, 1969); and Johannes Fabian, Out of Our Minds: Reason and Madness in the Exploration of Central Africa (Berkeley: University of California Press,

Page 13 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

2000). One notable exception is Dane Kennedy, The Highly Civilized Man: Richard Burton and the Victorian World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2005).

(8.) Nupur Chaudhuri and Margaret Strobel, eds., Western Women and Imperialism: Complicity and Resistance (Bloomington: Indian University Press, 1992); Antoinette Burton, Burdens of History: British Feminists, Indian Women, (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1994).

(9.) James Morris, Pax Britannica: The Climax of an Empire (New York: Harcourt, Brace, & World, 1968). There has been very little work on non-elite colonists. Exceptions include Robert Bickers, Empire Made Me: An Englishman Adrift in Shanghai (New York: Columbia University Press, 2003); Nicholas Thomas and Richard Eves, Bad Colonists: The South Sea Letters of Vernon Lee Walker and Louis Becke (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1999); Lucy Frost, No Place for a Nervous Lady: Voices from the Australian Bush, rev. edn. (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1995); Elizabeth Buettner, Empire Families: Britons and Late Imperial India (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004).

(10.) Clements Markham, ed., Narratives of the Mission of George Bogle to Tibet, and of the Journey of Thomas Manning to Lhasa (London: Trübner and

(11.) Mary Kingsley, Travels in West Africa (1897; London: Everyman, 1976), 157.

(12.) Daily Telegraph, 17 August 1866, quoted in Christine Bolt, Victorian Attitudes to Race (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1971), 143.

(13.) See Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi, Beyond Boredom and Anxiety: Experiencing Flow in Work and Play (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 1975) and Adam Phillips, On Kissing, Tickling, and Being Bored (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press,

(14.) Harriet Martineau, Eastern Life (Philadelphia: Lea and Blanchard, 1848), 58.

(15.) Eugen Weber, France, Fin de Siècle (Cambridge: Cambridge University According to T. C. W. Blanning, French politician Alphonse La France (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000), 241.

(16.) Flaubert in Egypt, trans. and ed. Francis Steegmuller (New York: Penguin Books, 1972), 140; Alain de Botton, The Art of Travel (New York: Pantheon

Page 14 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020

Gustave Flaubert, Madame Bovary, trans. Margaret Mauldon (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2004), 252.

(17.) J.-K. Huysmans, The Cathedral, trans. Clara Bell, ed., C. Kegan Paul (London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1922), 152.

(18.) Patricia Meyer Spacks, Boredom: The Literary History of a State of Mind Peter Toohey, Boredom: A Lively History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2011). In 1780, for example, boring. See her Diary and Letters, Vol. I (London: Henry Colburn, 1843), 424.

(19.) See Spacks, as well as Barbara Dalle Pezze and Carlo Salzani, eds., Essays on Boredom and Modernity (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 2009); Reinhard Kuhn, The Demon of Noontide: Ennui in Western Literature (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1976); Elizabeth Goodstein, Experience without Qualities: Boredom and Modernity (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2004). There were also expressions of boredom in the United States: see Daniel Paliwoda, Melville and the Theme of Boredom (Jefferson, NC: McFarland & Co., 2010).

(20.) Stanley Parker, The Sociology of Leisure (London: Allen & Unwin, 1976), 24. See also Peter Laslett, The World We Have Lost: England Before the Industrial Age 35.

(21.)

Past and Present

The culmination of this process came at the turn of the twentieth century: see Stephen Kern, The Culture of Time and Space (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1983). In The Railway Journey: The Industrialization of Time and Space in the 19th Century (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986), Wolfgang Schivelbusch links boredom to

(22.) The Birth of a Consumer Society, eds. Neil McKendrick, John Brewer, and J. H. Plumb (Bloomington: Peter Bailey, Leisure and Class in

(London: Routledge, 1978); Walter E. Houghton, The Victorian Frame of Mind, F. M. L.

Thompson, The Rise of Respectable Society: A Social History of Victorian Britain

Page 15 of 22

PRINTED FROM OXFORD SCHOLARSHIP ONLINE (www.oxfordscholarship.com). (c) Copyright Oxford University Press, 2020. All

Subscriber: University of Edinburgh; date: 24 May 2020