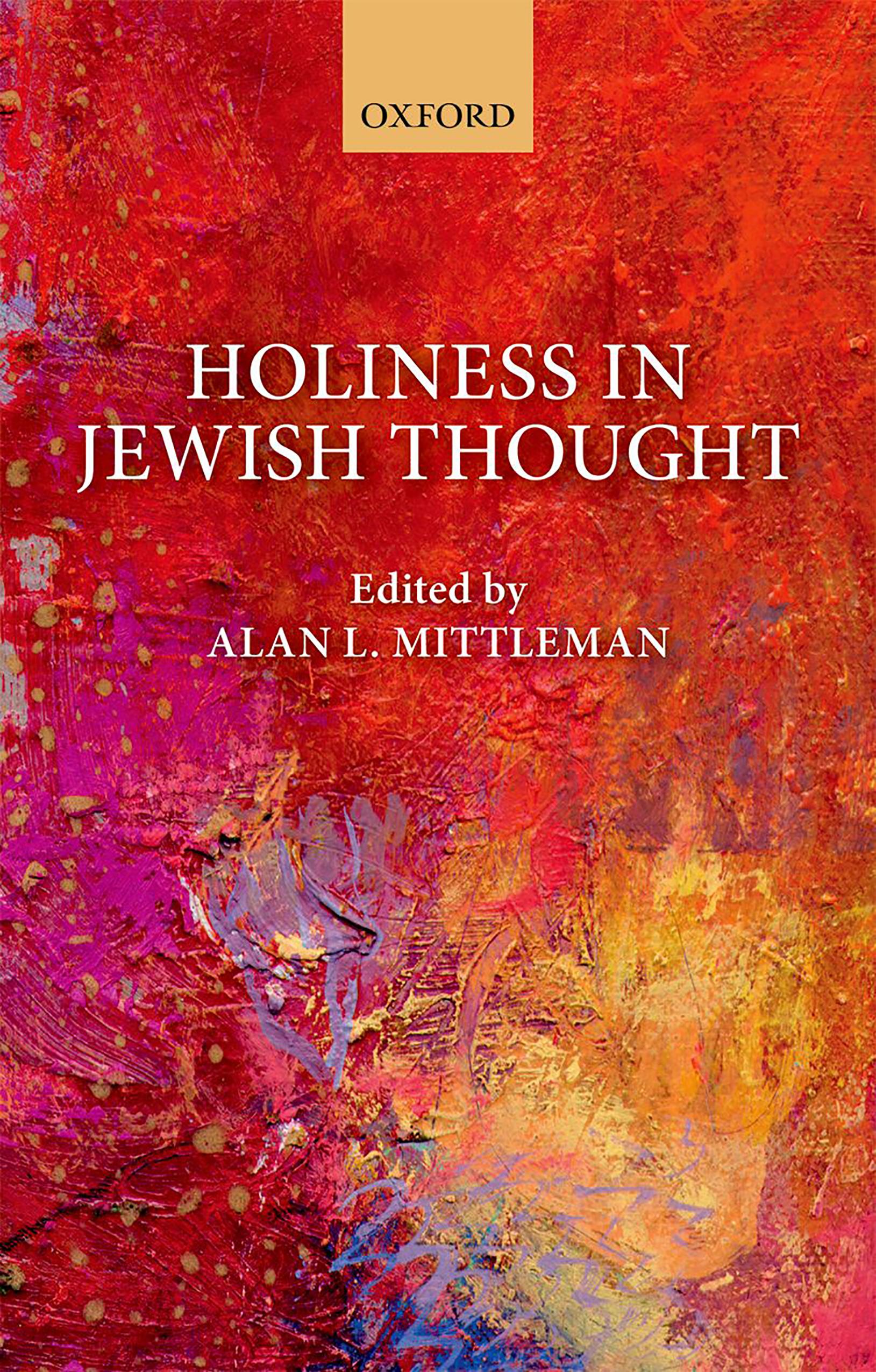

Holiness in Jewish Thought

EDITED BY ALAN L. MITTLEMAN

1

Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Oxford University Press 2018

The moral rights of the authors have been asserted

First Edition published in 2018

Impression: 1

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available

Library of Congress Control Number: 2017943293

ISBN 978–0–19–879649–7

Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY

Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. Oxford disclaims any responsibility for the materials contained in any third party website referenced in this work.

Acknowledgments

The core of this book originated in a scholarly working group on holiness convened by the Tikvah Project on Jewish Thought at Princeton University in 2010 under the direction of Prof. Leora Batnitzky. I am deeply grateful to Prof. Batnitzky for entrusting me with the leadership of the group and the choice of topic. It allowed me to pursue, with learned colleagues, questions about holiness that had gnawed at me for decades. I thank Rabbi Dr. Sol Cohen, who first got me thinking about the complexities of holiness in the mid-1970s. I thank as well the Tikvah Fund, which supported the many activities of the Tikvah Project at Princeton. The original members of the group, Professors Elsie Stern, Jonathan Jacobs, Joseph Isaac Lifshitz, Eitan Fishbane, and Sharon Portnoff contributed searching essays and showed great patience over several years as we contemplated what we might do with our fledgling work. Confident that we had something worth developing, I eventually reached out to scholars beyond the original group and invited further contributions. I thank Tzvi Novick, Martin Lockshin, Menachem Kellner, William Plevan, Hartley Lachter, and Lenn Goodman for their contributions. Special thanks go to Oxford University Press, especially to Tom Perridge and Karen Raith, for their openness to this project, as well as to the anonymous readers whose suggestions helped shape the volume.

The chapters by Lockshin and Kellner appeared in an earlier form elsewhere. (Martin J. Lockshin, “Is Holiness Contagious?” in Purity, Holiness, and Identity in Judaism and Christianity: Essays in Memory of Susan Haber, eds. Carl S. Ehrlich, Anders Runesson, and Eileen Schuler, Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck, 2013. Menachem Kellner, “Spiritual Life,” in The Cambridge Companion to Maimonides, ed. Kenneth Seeskin, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.) I thank Mohr Siebeck and Cambridge University Press for permission to use revised versions of those essays here. Further thanks go to Eisenbrauns, Yale University Press, Littman Library, and Stanford University Press for the use of extensive quoted material in Chapters 1, 5, 6, and 7 respectively.

I dedicate this volume to the memory of my dear friend, Prof. Johannes Brosseder (1937–2014), Professor of Catholic Theology at the University of Cologne, who showed me the importance of history for theology and the importance of hospitality for human flourishing.

Alan L. Mittleman

1. Reclaiming the Priestly Theology

Elsie R. Stern

2. Holiness in the Rabbinic Period

Tzvi Novick

3. Why is Holiness Not Contagious?

Martin Lockshin

4. Holiness and the Land of Israel

Joseph Isaac Lifshitz

5. Gratitude, Humility, and Holiness in Medieval Jewish Philosophy: A Rationalist Current

Jonathan Jacobs

6. Maimonides on Holiness

Menachem Kellner

7. Israel as a Holy People in Medieval Kabbalah

Hartley Lachter

8. Shabbat and Sacred Time in Later Hasidic Mysticism

Eitan P. Fishbane

9. Holiness in Hermann Cohen, Franz Rosenzweig, and Martin Buber

William Plevan

10. Holiness and the Holocaust: Emil Fackenheim and the Challenge of Historicism

Sharon Portnoff

Lenn E. Goodman

Holiness and Jewish Thought

Alan L. Mittleman

Holiness is a challenge for contemporary Jewish thought. The concept of holiness is crucial to religious discourse in general and to Jewish discourse in particular. “Holiness” seems to express an important feature of religious thought and of religious ways of life. Yet the concept is ill defined. What does “holy” mean? How do most people use the word? Do the people who use it know what they are talking about or is it a vague verbal gesture? Presumably, the biblical Hebrew words that we translate by “holy” or “holiness” once had a precise meaning or meanings. Assuming that we can reconstruct them, can we reappropriate them?1 This volume attempts to do just that—to explore what concepts of holiness were operative in different periods of Jewish history and bodies of Jewish literature and to offer preliminary reflections on their theological and philosophical import today.

To get a sense of the stakes, consider the following quote from Abraham Joshua Heschel. In a moving reminiscence of the intellectual struggles of his student days at the University of Berlin, Heschel writes: “The problem to my professors was how to be good. In my ears the question rang: how to be holy.” He continues:

1 Several paragraphs of this Introduction appeared previously in Alan Mittleman, “The Problem of Holiness,” The Journal of Analytic Theology, Vol. 3, May 2015 and are used here with permission of the journal.

Introduction: Holiness and Jewish Thought

To the philosophers, the idea of the good was the most exalted idea, the ultimate idea. To Judaism the idea of the good is penultimate. It cannot exist without the holy. The good is the base; the holy is the summit. Man cannot be good unless he strives to be holy.2

Heschel was staking out a territory for Jewish uniqueness, for a form of life that in some way exceeded the good life as conceived by Western philosophy. Western notions of reason, morality, and happiness had to be ordered to holiness to achieve stability or fulfillment. Undoubtedly, the young man from Warsaw was coping with his status as an outsider in the tumultuous capital of the Weimar Republic. His claim reflects a struggle for dignity and identity vis-à-vis the majority culture. But beyond that struggle, is Heschel’s claim philosophically cogent? Does goodness need holiness? What precisely would holiness, if it could be adequately defined, add?

Solomon Schechter, an early twentieth century figure who founded the seminary in New York at which Heschel, as a refugee from the Holocaust, would eventually teach, wrote: “Holiness is the highest achievement of the Law and the deepest experience as well as realization of righteousness. . . . In its broad features holiness is but another word for imitatio dei, a duty intimately associated with Israel’s close contact with God.”3 Schechter, following the Talmud, then constitutes imitatio dei by a set of actions which reflect moral goodness: clothing the naked, nursing the sick, comforting mourners, burying the dead. Holiness seems indistinguishable from consistently good acts or from the virtuous disposition which gives rises to good actions. If there is some criterion that distinguishes holiness from morality broadly speaking, it is not clear on Schechter’s account what it is. The imitation of God, which for him constitutes holiness, is ipso facto the imitation of a moral God. The transparently moral quality of altruistic acts gains rhetorical force through association with the divine but does it gain anything else?

Although Heschel and Schechter, as they ethicize holiness, reflect authentic currents of Jewish thought, they also scant the non-moral elements that give holiness, in the ancient context, its enigmatic character. The early twentieth-century German scholar, Rudolf Otto, gave

2 Abraham Joshua Heschel, “The Meaning of Observance,” in Jacob Neusner, ed., Understanding Jewish Theology: Classical Issues and Modern Perspectives (Binghamton: Global Publications, 2001), 95.

3 Solomon Schechter, Aspects of Rabbinic Theology (New York: Schocken Books, 1961), 199.

memorable expression to those dimensions with his phrase mysterium tremendum et fascinans. He alluded to the “numinous” character of the experience of the holy, to its uncanny, dangerous dimension. Otto sought, in perhaps too Romantic a way, to recover a God unconstrained by “civilized” or rational norms. For him, holiness does not refer to consistent moral goodness but to (amoral) power. To infringe on God’s holy space or possessions is to risk instantaneous destruction, as Nadav and Abihu (Lev ch. 10) discovered when they offered “alien fire” on the altar or as befell Uzzah when he touched the holy Ark to prevent it from falling (II Sam ch. 6). God is totaliter aliter, wholly Other; a force not originally bound to morally intelligible norms, on Otto’s view. To what extent does Otto’s view capture authentic elements of the biblical tradition? To what extent does it resonate with later Jewish tradition? Otto’s studied irrationalism may fall afoul of much of the Jewish tradition but it still has a heuristic function. It sets out a theory of holiness much at odds with the ethicized version. Several of the chapters in this book analyze the tension between views such as those of Otto and those of Heschel and Schechter. Some of the contributors are deferential to Otto; some struggle with his portrayal of holiness; some (especially Lenn Goodman in the Afterword) reject him forcefully.

Otto’s treatment of holiness in the Bible emphasizes its ontological dimension. For the biblical authors, holiness does seem to indicate a mysterious presence or property of special objects, times, places, or beings. In biblical religion, the ground on which Moses unwittingly stood prior to his encounter with God was holy (Exod 3:5). The wilderness tabernacle was holy (Exod 29:42–6), as were the two temples erected in Jerusalem, as well as, according to the Mishnah, the innermost chamber of the Temple, the outer courts, the city of Jerusalem, its environs, and ultimately the entire Land of Israel. Holiness was graded from center to periphery, as if it were a substance that became more diluted as it dissolved and diffused.4 Where holiness is most concentrated or intense, the objects, places, or times that exemplify or bear it require special treatment. They are separated from normal consideration or use. One must be in a state of ritual purity, enabled by elaborate regulations and procedures in order to encounter the holy. This is, we might say, a metaphysically inflated view.

4 Philip P. Jenson, Graded Holiness: Key to the Priestly Conception of the World, JSOT Sup 106 (Sheffield, 1992).

Introduction: Holiness and Jewish Thought

The tacit claim that holiness is metaphysical property need not be limited to archaic religion. I recall being in line years ago to see the Bill of Rights and the Declaration of Independence in the National Archives. I wanted to see the First Amendment with my own eyes. As I approached the documents, in their evocatively biblical setting of ark and altar, I craned my neck to read the text of the First Amendment. A guard barked at me: The document is for viewing, not for reading! Move along! I had unwittingly profaned a sacred object, thoughtlessly bringing it into the normal world of daily use by treating it as a mere text. Purity considerations were not in play here but an awareness of the sacred and the danger of its profanation surely was.

How is one to think about this putative property of holiness? A property might be ontological or relational. That is, holiness could be thought to inhere in objects in the way that redness inheres in a red ball. There is something physical about it. Or holiness might be conceived not so much as a property available to empirical observation (or pretending to be available to empirical observation) but as a relation, an ascription of status, rank, or significance to something relative to other things. On this view, holiness is ascribed to the Temple or the People of Israel in the way that large is ascribed to a large ball or good to an exemplary horse. Largeness is not an inherent property of the ball; it is a property only insofar as the ball is related to other, smaller balls. So too with good; the good horse is the one that runs best. From this perspective holy designates a status, rank, or significance within a framework of relations rather than a substantive or ontological quality of an object, time, or place. Holiness is an evaluation, an assertion of value. Concepts of holiness, both in the Bible and in later Jewish literature display both features.

Holiness sometimes seems to be an almost physical property. But it is also a way of designating the status, stature, or significance of an item. Eyal Regev argues that the Bible tracks both of these dimensions. It has two main conceptions of holiness: dynamic and static. On the dynamic view, which informs the priestly writings, holiness is property-like; its presence waxes and wanes depending on Israel’s actions and condition of purity or impurity. Holiness emanates from the Temple, where God is present. It is endangered by impurity and must be protected from it. On the static view, associated with Deuteronomy, holiness is an ascription of status fixed by legal norms. There is nothing natural, objective, or substantial about holiness; it depends on human compliance with the covenant. If Israel does its duty, then it is holy. If it doesn’t, it loses

that status (albeit not permanently). Where the priestly outlook reifies holiness, Deuteronomy emphasizes deontology over ontology, holiness as legal artifact instead of property.5

Whether holy names a putative ontological property or is closer to evaluative terms than to empirically descriptive ones, the question remains: what warrants a correct evaluation, a correct employment of the term? What are the grounds or warrants for holiness? What governs whether we use holy (qadosh) correctly (or incorrectly)? There are criteria for the correct predication, in context, of large or good—or of red, but are there similar criteria for holiness? One answer to this question is strictly conventional: the tradition, for no reasons other than internal ones, tells us what is holy and what is not. We know that Zion is holy and Sinai is not because tradition tells us so. Holiness is simply an artifact of the Torah’s legal system; it is based on nothing but the Torah’s claim to divine authority. (In this volume, Tzvi Novick and Menachem Kellner argue that the Rabbis and Maimonides, respectively, made just this move. They de-centered holiness as an independent category and subordinated it to the law, a move already prepared by Deuteronomy, if Regev is correct.) Or, where holiness is granted an ontological dimension, its only tokens are those described in the Bible. Other religions may have their holy places or holy men and women, but they are confused or mistaken insofar as holiness is explicable solely within the terms set by Torah. Claims to holiness elsewhere (as in the civil-religious example above) are at best derivative. Thus, a holy life is one of strict fidelity to the inherent norms of the Judaic system; holiness as it pertains to persons is nothing more or less than this. Holiness is sui generis and incommensurable. A disturbing implication of this is that holy acts gain their justification without reference to external normative standards. If holy war, for example, is what God is thought to require then mere ethical constraints count for nothing. Holiness trumps all other considerations and is answerable only to internal norms and authorities.

Such a view has a degree of explanatory power but it is also an arrest of thought. It precludes further inquiry into the nature of holiness. It prevents understanding Jewish concepts through comparison with philosophical or other religious ideas. It fails to account for the intuition that holiness is intelligible even when it is not Judaic. Should we

5 Eyal Regev, “Priestly Dynamic Holiness and Deuteronomic Static Holiness,” Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 51, Fasc. 2, April, 2001, 243–61.

Introduction: Holiness and Jewish Thought

doubt that Mother Teresa did holy work or that compassionate, saintly persons from other religious cultures cannot on principle be thought holy? Should we doubt that there is something supremely unholy about holy war? Conventionalism, although it fills the term with a distinctive content, leaves both word and meaning suspended in the air, useful only to the denizens of the enclave where the language is spoken. The contributors to this volume eschew this stance and adopt a comparative and phenomenological one.

What emerges from the various explorations are two approaches, both manifest in the primary sources and in the scholars’ interpretations of them. The first approach takes the ontological dimension of holiness seriously (call this metaphysical inflation); the second takes an axiological approach (metaphysical deflation). As we have seen, on the view that holiness is a property inherent in objects, holy works like red. To make this claim is to assume that terms have extension or reference. It is to assume that there must be an objective feature of the universe to which holy refers when used properly. Such a feature is typically thought to be supernatural. In the Bible, the holy implies the presence of God. God comes into the world from another order of reality; holiness marks God’s presence. Where God appears is holy for the duration of the appearance; what God designates as his own is removed from ordinary use. This view seems typical of much religious thought throughout the millennia (see, especially, the work of Mircea Eliade). It posits a wholly other dimension, a special order of transcendent reality, which enters our cosmos as holiness (qedusha, in post-Biblical Hebrew). A holy place, pace Eliade, is an axis mundi; a place where the transcendent and the immanent are linked. A holy time reenacts the primordial time of the beginning (in illo tempore), infusing the entropic present with renewed power. This is not just a way of speaking that means to endow phenomena with extraordinary significance; it makes an ontological claim about what sorts of things and states make up reality. This is what we might call a strong constitution of holiness. On this view, statements such as “The Land of Israel is holy” or “The Sabbath is holy” have truth value in a way similar to the truth value held by observation statements such as “The ball is red.” We cannot, of course, see qedusha as we can see (given normally functioning eyes) red, but we are thought to be able somehow to sense it. Portrayals of the holiness of space, as described in this volume, by Isaac Lifshitz, or of time, as described here by Eitan Fishbane, are at home with such assertions. So too the mystical tradition’s

portrayal of the holiness of the Jewish people as analyzed here by Hartley Lachter. In his chapter, Martin Lockshin treats puzzling ancient and medieval texts which seem to endorse holiness as a “contagious” property, similar to impurity, which spreads by physical contact, and yet to retreat from those implications at the same time. What fuels the metaphysical inflation is a strong claim about divine presence. God enters and acts in the world in a definite, agential way. Holiness comes from (and with) God.

The axiological approach makes weaker claims for the holy. Here, to repeat, holy is less like red than it is like an evaluative term, such as good. Holiness is not a “physical” property; it is a value. But what kind of value does it signify? Arguably, holy signifies an evaluative concept within a normative universe that is thicker and more particular than the normative universe sketched by “thin” terms such as good. Thus, one who strenuously observes Shabbat, kashrut, family purity, and so on— one who accepts the mitzvah of sanctifying God’s name (qiddush haShem) and tries to live by it every waking hour in speech, in thought, in action—such a person is holy. Such a person lives up to an ideal that has shaped his or her life. Holiness connotes a value that exceeds a thin, purely ethical standard but is continuous with such a standard, perhaps in a dialectical way. Holiness gives substance and focus to the right and the good but can also be corrected by them. This presumably is what writers such as Schechter and Heschel had in mind. Others, such as Eliezer Berkovits appear to go further. Berkovits writes:

Holiness is not, for example, ethics. Holiness is a specifically religious category. The highest form of ethics may be unrelated to holiness. It is a noble thing to do the good for its own sake, but it is not holiness. Holiness is being with God by doing God’s will. Now, it is the will of God that man should act ethically. But if he acts ethically for the sake of the good, he is an ethical man; if he does so for the sake of God, in order to do God’s will, he is striving for holiness.6

Berkovits wants to discern a separate sphere for religious values such as holiness. He is keen to avoid the complete ethicization of the holy, such that holiness becomes superfluous or redundant. But I don’t think that

6 Presumably no “teleological suspension of the ethical” is entailed by Berkovits’s view; holiness is thus continuous with ethics for Berkovits in a way that it would not be for Otto or Kierkegaard. See Eliezer Berkovits, “The Concept of Holiness,” in Eliezer Berkovits, Essential Essays on Judaism, David Hazony, ed. (Jerusalem: Shalem Press, 2002), 284.

Introduction: Holiness and Jewish Thought

he intends a sharp dichotomy between the religious and the ethical. That would, at any rate, cut against a great deal of the Jewish tradition. On the axiological view, holiness takes its stand on the particular but does not divorce the particular from transcendent norms. This approach was manifest in the Middle Ages among rationalist Jewish philosophers, as interpreted here by Jonathan Jacobs. It is widespread in contemporary Jewish thought and life, as analyzed in the chapter by William Plevan. For medieval thinkers, distinctive, traditional Jewish practices are thought to align one with intellectual and practical virtue; to enable the highest degree of perfection of which humans are capable. For modern thinkers, Jewish tradition enriches one’s life and secures the future of one’s people. Holiness is a function of a particular way of life (Hegel’s Sittlichkeit) but is related to universal norms (Moralität). The Jews, as a holy people, should be a light unto the nations. They should enable the nations, so to speak, to see what holiness is. This approach is neither reductive nor conventional. It has confidence in the cross-cultural intelligibility of holiness, as well as in its cultural particularity. It has confidence in the moral soundness of holiness even as the holy exceeds “mere” ethics.

Both of these approaches have problems. The metaphysically inflated version of holiness is at home in some strands of biblical and medieval Judaism. The problem with a strong constitution of holiness, after the age of miracles has passed, is that many of us have a hard time believing it. Clearly many people continue to believe in miracles, angels, and so on—the doors of the church, as Weber put it, always remain open, even in a disenchanted age. And many of us today are disenchanted with disenchantment, as the late Ernest Gellner remarked.7 Nonetheless, the wholesale construction of another world from whence holiness derives seems overly imaginary, unbound from the cords of reason. (The problem here is less a conviction about the homogeneity of causation—a conviction upset by quantum mechanics—than an intuition of troubling paradoxicality.) A substantively miraculous or occult view of holiness forces us to posit another world. This other world is a charmed, spiritual sphere, albeit with some of the same ontological features as our world (space, time, force, causality). The ontological features of our world make for its plausibility and intelligibility. The imagined features of the posited world are parasitic on our world; they draw their patina

7 Ernest Gellner, Culture, Identity, and Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987), 152–65.

of intelligibility and plausibility from it without actually being accountable to it. Our world is glued together by the principle of sufficient reason but the other world is not answerable to it. The other world wants to have its cake and eat it too. Angels can hear without having ears, as it were. But one can’t have it both ways. To the extent that terms such as holiness seem to require an ontological rootedness in another world, they are highly suspect from an ideal-typical modern point of view. One might always say, so much the worse for the moderns, but such a reply diminishes the genuine religiosity of many modern Jews, as well as Jewish rationalists in the past, who sought an expression of faith that didn’t require the sacrifice of intellect. Maimonides believed in both the Torah and physics. This remains, for some modern Jews, at least, an ideal. Nonetheless, the strong concept of holiness retains an appeal. Wrestling with it helps drive the theological inquiry in several of the chapters.

The metaphysically deflated, axiological approach—holiness as a status or a value—does not commit us to ontological promiscuity but it is also problematic. Isn’t it the case that thick, particular standards are ultimately to be justified, indeed, to be explained, by their compliance with thinner universal standards? (As Christine Korsgaard has argued, the claim that belonging to a thick, particular culture is good for persons is a universal claim.8) The cross-cultural intelligibility of holiness, which first seems to be a strength of this approach, soon becomes a problem. Deuteronomy promises, for example, that Israel will be known as a wise and discerning people (Deut 4:6) due to its exemplary way of life. The standards for wisdom and discernment are not intrinsic to the Torah; the Torah itself is answerable to extrinsic standards here. Again, if the standards of holiness were only internally constituted, that is, merely conventional such that holiness = compliance with the statutes of the Torah, then holiness would be circular, perhaps viciously circular. This would seem a diminution of holiness. A virtuoso chess player has mastered the game but we find his virtuosity valuable because we find the game valuable—we evaluate the game according to standards that go beyond its own rules. Could that be less true of Judaism? If it is the case with religion in general and Judaism in particular that even outsiders can find value in “the game,” that is, that they can sense the value of holiness that emerges from its way of life,

8 Christine Korsgaard, The Sources of Normativity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996), 119.

Introduction: Holiness and Jewish Thought

then we return to thin moral evaluation as the controlling criterion. To the extent that particularity is answerable to meta-particular standards, doesn’t the second approach collapse the meaning of holiness into generic value? Wouldn’t Heschel or Berkovits, if pressed, have to give a rational explanation of why they find belief in God compelling? That God anchors and orients the holy life, but not necessarily the moral life, does not relieve the religious from giving an intelligible account of their faith.

As we have seen, the ontological and the axiological approaches to holiness need not conflict with or exclude one another. The Jewish tradition has often sought to harmonize them. In the Bible, even without consideration of Deuteronomy, Leviticus itself includes “moral” considerations in the midst of priestly, ritualistic ones. The Holiness Code of Leviticus, chapters 17–26, subtly augments the meaning of the holy from the “effervescence of the Presence of the LORD” to the task of the Israelite people, who “can and must attain” it.9 Holiness shifts from a seeming property of things in God’s presence or possession to an ideal that ought to transform lives. “You shall be holy, for I, the LORD your God am holy,” signifies more than being in a state of ritual purity in the cultic center.

Building on this fused view of holiness, the Talmud, in Bavli Avodah Zarah 20b, integrates holiness into a “ladder of virtues.” R. Pinchas ben Yair asserts that “Torah leads to watchfulness; watchfulness leads to zeal; zeal leads to cleanliness; cleanliness leads to separation; separation leads to purity; purity leads to saintliness; saintliness leads to humility; humility leads to fear of sin; fear of sin leads to holiness; holiness leads to the holy spirit, and the holy spirit leads to the revival of the dead.” Here, moral considerations and metaphysical ones are interlaced. Priestly concerns for ritual purity and impurity, as in Leviticus, blend seamlessly with moral virtues.

The holy has a long history of development in the Jewish tradition. This book seeks to illumine some of its major episodes. Yet it does so under a partial shadow. In the last chapter, Sharon Portnoff asks whether holiness is possible after the Holocaust, whether holiness can, with full intellectual and spiritual honesty, be restored to a history of absolute desecration. Exploring the work of Emil Fackenheim, she argues both that we must seek holiness in response to Auschwitz

9 Adele Berlin and Marc Zvi Brettler, eds., The Jewish Study Bible (New York: Oxford University Press, 2004), 253.

and that it may well be impossible to do so. That is not the only paradox that the student of holiness encounters, but it may be the most unsettling.

The challenge to the contributors to this volume was to think about the problems and potential implicit in Judaic concepts of holiness, to make them explicit, and to try to retrieve the concepts for contemporary theological and philosophical reflection. Not all of the contributors pushed into philosophical and theological territory, but all of the contributions provide resources for the reader to do so. Holiness is elusive but it need not be opaque. It is the hope of the editor and the contributors that this volume makes Jewish concepts of holiness lucid, accessible, and intellectually engaging.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Berkovits, Eliezer, 2002, “The Concept of Holiness,” in Eliezer Berkovits, Essential Essays on Judaism, ed., David Hazony (Jerusalem: Shalem Press).

Berlin, Adele and Brettler, Marc Zvi eds., 2004, The Jewish Study Bible (New York: Oxford University Press).

Gellner, Ernest, 1987, Culture, Identity, and Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Heschel, Abraham Joshua, 2001, “The Meaning of Observance,” in Jacob Neusner, ed., Understanding Jewish Theology: Classical Issues and Modern Perspectives (Binghamton: Global Publications).

Jenson, Philip P., 1992, Graded Holiness: Key to the Priestly Conception of the World, JSOT Sup 106, Sheffield.

Korsgaard, Christine, 1996, The Sources of Normativity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Mittleman, Alan, 2015, “The Problem of Holiness,” The Journal of Analytic Theology, Vol. 3: 29–46.

Regev, Eyal, 2001, “Priestly Dynamic Holiness and Deuteronomic Static Holiness,” Vetus Testamentum, Vol. 51, Fasc. 2.

Schechter, Solomon, 1961, Aspects of Rabbinic Theology (New York: Schocken Books).

Reclaiming the Priestly Theology

Elsie R. Stern

The Pentateuchal texts ascribed to the priestly source have been the subject of substantial scholarly attention. Their dating, their subdivision into discrete sources, and the nature and meaning of the rituals they describe have been amply and insightfully explored. At the same time, however, the priestly source has not figured prominently in constructive biblical theology. When scholars and theologians are attempting to demonstrate how biblical sources can resonate with contemporary beliefs and serve as spiritual and theological resources for contemporary Jews and Christians, the book of Leviticus, with the exception of the so-called Holiness Code in chapters 17–26, rarely receives top billing. In this chapter, I will explore the central reasons for the low profile of the priestly texts in contemporary biblical theology and will make a case for reclaiming Leviticus as a theological resource, particularly for contemporary Jews.

Like any work of biblical theology, this is ultimately a creative exercise grounded in analytic and critical work. In it, I do not pretend to articulate definitively the idea of God held by the authors of the priestly texts of the Torah. Rather, I intend to articulate a set of theological possibilities that is generated by immersion in these texts and contemporary scholarly commentaries on them. This set of possibilities is inherently composite—constructed out of the insights articulated by various texts and various scholars. While I hope it is coherent and internally consistent, it does not derive from any single priestly text or scholarly perspective. My intuition, which is backed up by years of teaching this material to various audiences, is that the theological directions pointed to by the priestly texts are potentially resonant and

useful for contemporary non-Orthodox Jews who are looking for theological language that resonates with their own experiences and ideas about the divine. In addition, as I will argue more fully in this chapter, a theology that is grounded in the priestly texts avoids many of the theological and philosophical problems encountered by contemporary Jews who are trying to construct a compelling theological portrait out of more commonly referenced biblical perspectives.

In the context of an interdisciplinary volume such as this, it is important to ask why such a project is necessary or desirable. Such a challenge would underscore the following: the goal of the project is not to prove that a theology derived from the priestly sources is “right” or is even more plausible than other theologies derived from other biblical sources or other sources, be they literary or experiential. Rather, the goal of the project is to offer up a set of theological possibilities that have the potential to resonate with the beliefs and experiences of some contemporary Jews. If the project aims to be theologically resonant, rather than theologically persuasive, why is it necessary? Why does it matter if one can articulate a reading of Leviticus that resonates with what readers already believe, experience, or intuit? Does this exercise function only to authorize beliefs and convictions that have already been formed on the basis of experience? If so, why would such biblical authorization be necessary for Jews who do not recognize, in any concrete way, the authority of the biblical texts?

In my experience teaching the priestly material to a wide range of Jewish adults, I have found that many adults have intuitions and convictions that are still works in progress. Many adults have theological intuitions about the nature of God as they experience it and equally strong, if not stronger, resistance to theological assertions that do not resonate with their personal experience or understanding of history and the human condition. However, they often do not have a theological language that can help them explore and express the complexities and nuances that comprise, undergird, and complicate their intuitions and convictions. For these adults, the articulation of a set of theological possibilities, which, in this case, are derived from a reading of the priestly material and the scholarship on it, can offer a language for their experience. It can help them to describe and further explore their own theological experiences and convictions.

In addition, I hope that the explication and mediation of priestly texts that I perform here will give non-professional readers of biblical texts a more balanced portrait of the theologies of the Pentateuch.

Reclaiming

By accident of genre, the anthropomorphic and covenantal theologies that are articulated in the Pentateuch are far more accessible to contemporary readers than the priestly theology of Leviticus. Most adults come to the biblical texts as experienced readers of prose narrative and expository prose. As a result of these competencies, they are quite able to understand the theological “messages” of the prose narratives and prose sermons of Genesis, Exodus, much of Numbers and Deuteronomy without mediation by professional readers. In contrast, the priestly texts clustered in Leviticus are nearly incomprehensible to contemporary lay readers. Thus, these lay readers, even those who have read widely in the Pentateuch, tend to walk away with an understanding of Torah theology (or Torah theologies) in which the anthropomorphic and covenantal theologies are over-represented and the priestly theology is largely absent. As I will argue below, these more accessible theologies are often less resonant for contemporary readers than the far more opaque theology implied by the ritual prescriptions of the priestly texts.

1.1 EARLY FORMULATIONS OF PRIESTLY THEOLOGY: WELLHAUSEN AND KAUFFMANN

Although it holds an important place in traditional Jewish study, the book of Leviticus is not readily accessible to most contemporary readers. Chapters 1–16 of the book are comprised of instructions regarding the sacrificial cult and its personnel, the categories of purity and impurity and the systems for dealing with the latter. Chapters 17–27 articulate a more comprehensive and eclectic set of mandates that deal with a wide range of ritual and social-ethical issues. Not only is the genre uninviting, but the central topic—the sacrificial cult, is totally foreign to contemporary Jewish sensibilities. This, in fact, is the great paradox of the priestly texts. While there are certainly aspects of Israelite religion that would have appeared distinctive to other ancient near eastern peoples, the sacrificial cult, the special role of the priests, and the construction of categories of purity and impurity would have been entirely recognizable as common, cross-cultural religious behavior. It is precisely these elements, which would have been most familiar to ancient near eastern audiences, that have proven theologically alienating to many modern Jewish and Christian readers. The sense of

alienation or inscrutability engendered by the priestly texts has figured prominently in scholarly historical and theological treatments of them.

The most prominent example is Julius Wellhausen, the German, Protestant scholar of the nineteenth century whose work Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel became one of the most important works of modern biblical scholarship. Building on the work of earlier scholars, who had already identified different literary strands within the Pentateuch, Wellhausen articulated a chronology of these sources that began with the largely narrative texts of the Yahwist and Elohist sources, continued with the texts of the Deuteronomy and ended, in the post-exilic period, with the texts of the priestly source, which Wellhausen identified as including the legal material in the book of Leviticus as well as other units of texts located throughout the books of Genesis, Exodus, and Numbers. While the articulation of this chronological scheme is the raison d’eˆtre of the work, Wellhausen notes that the project was born out of a particular theological experience—a sense of profound alienation from the legal, and in particular, the priestly texts of the Pentateuch:

In my early student days, I was attracted by the stories of Saul and David, Ahab and Elijah; the discourses of Amos and Isaiah laid a strong hold on me, and I read myself well into the prophetic and historical books of the Old Testament. Thanks to such aids as were accessible to me, I even considered that I understood them tolerably but at the same time was troubled with a bad conscience, as if I were beginning with the roof instead of the foundation; for I had no thorough acquaintance with the Law, of which I was accustomed to be told that it was the basis and postulate of the whole literature. At last I took courage and made my way through Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and even through Knobel’s Commentary to these books. But it was in vain that I looked for the light which was to be shed from this source on the historical and prophetical books. On the contrary, my enjoyment of the latter was marred by the Law; it did not bring them any nearer me, but intruded itself uneasily, like a ghost that makes a noise indeed, but is not visible and really effects nothing.1

Wellhausen’s anxiety is palpable here. He is a serious, thoughtful Protestant reader who is confronted with a theoretically fundamental part of the Christian canon—“which [he] was accustomed to be told

1 Julius Wellhausen, Prolegomena to the History of Ancient Israel (New York: Meridian, 1957), 3.