Introduction

TheLegacyofHermannCohen

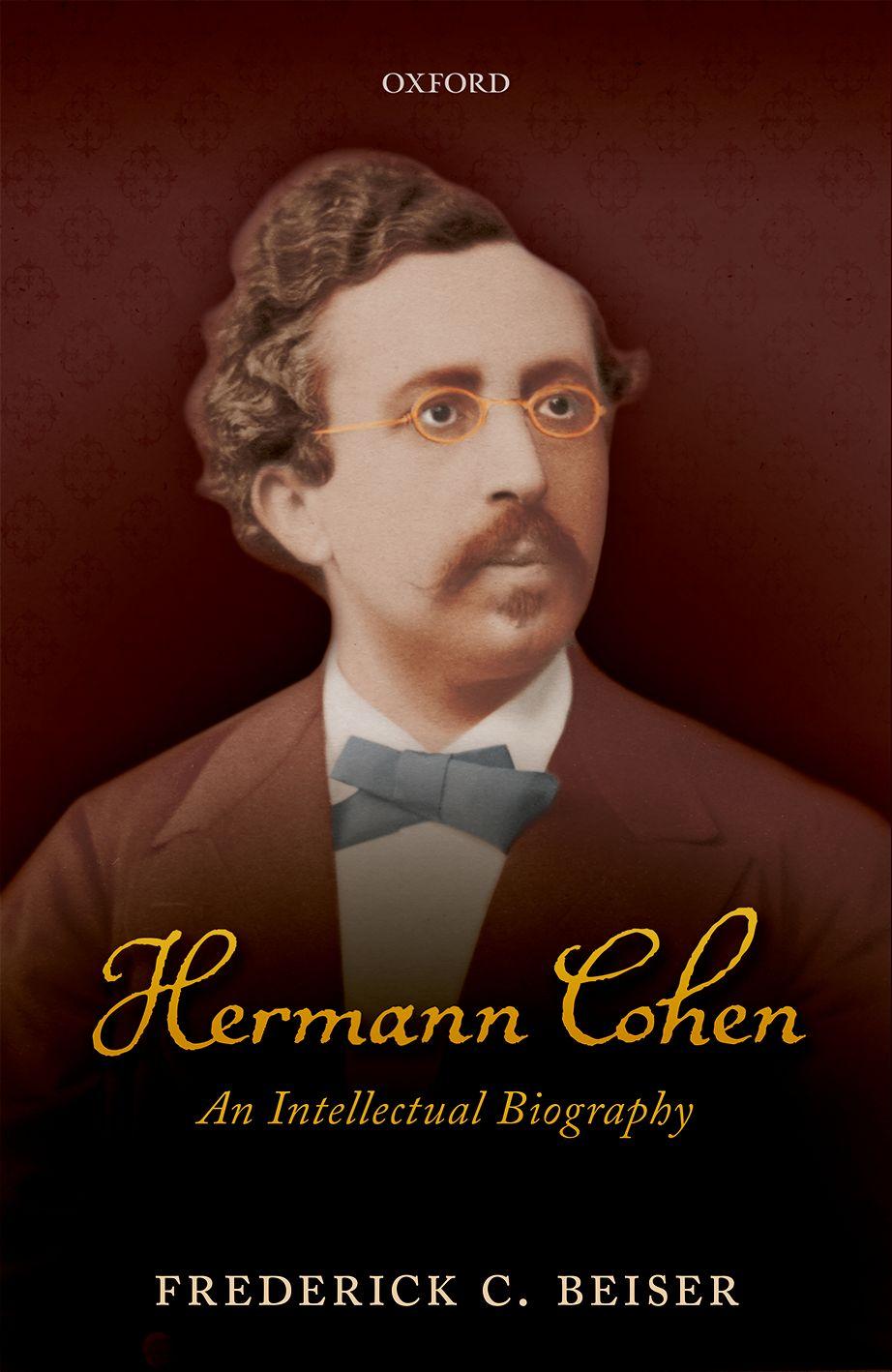

HermannCohenwasthelastgreatthinkerintheGermanidealisttradition.Hewas the finalspokesmanforthechiefintellectualvalueofthistradition:thesovereigntyof reason,thepreeminenceofreasonnotonlyinthespheresofepistemologyand metaphysics,butalsointhoseofethics,politics,andreligion.CohenwastheselfconsciousheiroftheEnlightenment,andhestrivedtomaintainitscardinalvalues criticalrationality,toleration,andhumanity inaworldwhichhadreactedincreasingly againstthem.Asthelastidealist,Cohenstoodapartfromhisageandmadeabrave standagainst(whatheperceivedas)itsmanyirrationalistmovements:historicism, materialism,nationalism,pessimism,antisemitism,existentialism,andZionism.His standwasheroicbuttragic:heroic,becauseitrepresentedthehighestmoraland intellectualideals;buttragic,becauseallhiscausesweredefeatedbyhistory.

CohenisbestknowntodayastheleaderoftheMarburgschoolofneo-Kantian philosophy,which flourishedfrom1875,thedateofCohen’sappointmentasafull professor,until1912,thedateofhisretirement.UnderCohen’sleadership,Marburg becameknownworldwideasoneofthebestuniversitiestostudyKant’sphilosophy. StudentscamefromallovertheworldtostudyunderCohen,amongthemBoris PasternakfromRussia,JoséOrtegayGassetfromSpain,andWladyslawTartarkiewicz fromPoland.AmongCohen’smostfamousstudentswereKurtEisner,PaulNatorp, andErnstCassirer.

Cohen’sintellectualachievementswereimmense,andtheyarestillnotfully appreciatedbyphilosophersandscholarstoday.Theytookplaceinfourmajor areas,justoneofwhichwouldbesufficienttogivehimaclaimtoimmortality. Eachareadeservesalittleexplanation.

First,intheareaofKantscholarship,Cohenspearheadedtheepistemological interpretationofKant’sphilosophy,accordingtowhichitscentralproblemisthe logicaljustificationof,ratherthanpsychologicalexplanationfor,syntheticapriori judgments.ThoughCohenhimselfdidnotcompletelyabandonapsychological interpretationofKant’sphilosophy,heplacedthechiefemphasisonKant’sepistemologicalproblem.ThiswasamajorbreakwiththepsychologicalandphysiologicalinterpretationsofKant,whichhadbeentheprevalentinterpretationbefore Cohen.InthisrespectcontemporaryKantscholars,especiallythoseintheAngloAmericantradition,standinCohen’sdebt.

Second,inthesphereofpolitics,Cohenwasthefatherofethicalsocialism,which, towardtheendofthenineteenthcenturyandbeginningofthetwentieth,becamethe chiefcompetitortoorthodoxMarxismastheideologyofsocialism.AlthoughCohen

formulatedthisdoctrineinaroughandsketchyform,itwasdevelopedingreater detailbyhisdisciples,whothenpromulgateditthroughoutGermany.Among Cohen’sdisciplesweresomeveryillustriousnames,suchasRudolfStammler (1856–1935),FranzStaudinger(1849–1921),KarlVorlander(1860–1928),and KurtEisner(1867–1919).Sadly,ethicalsocialismdidnotmeetwithmuchpractical orpoliticalsuccessinitsday.ItsideaswereadoptedbyEduardBernstein (1850–1932),whoattemptedtomakeethicalsocialismtheofficialideologyofthe SPD,themainsocialistpartyinGermany.Bernstein’seffortsweredefeatedbythe MarxistsattheDresdenpartyconferencein1902.Butethicalsocialismwasnot forgotten;itscauselivedontobecomethepartydoctrineoftheSPDinthe1950s.In thisindirectandlongdrawn-outway,Cohen’sphilosophycouldbesaidtohavehad animportantinfluenceonGermanpolitics.

Third,intheareaofthephilosophyofreligion,Cohen’sphilosophyisthelastgreat representativeoftherationalistJewishtradition.Cohen’ s ReligionderVernunft isone ofthegreatmasterpiecesinthattradition,onaparwithMaimonides’ Guideforthe Perplexed,Spinoza’ s Ethics,andMendelssohn’ s Jerusalem.ThoughCohen’sbook verymuchfallswithinaJewishtradition,bothphilosophicallyandculturally,it wouldbeamistaketothinkthatitwaswrittenforJewsandthatitisonlyabout them.Coheninsistedthathisreligionofreasonwasanidealwhich any historical religioncouldrealizemoreorless.TheonlypriorityCohengavetoJudaismwastoits historicalorigins:thesourcesofthereligionofreasoncamefromtheOldTestament. ButthiswasaclaimthattheothertwoAbrahamicreligions IslamandChristianity couldreadilyaccept.

Itmightseemarchaic,orevenreactionary,toformulateareligionofreasoninthe earlytwentiethcentury.Afterall,deismwasaneighteenth-centuryfashion,whose fortunesrapidlydeclinedundertheweightofhistoricismandKantiancriticism.Itis importanttosee,however,thatCohen’ s ReligionderVernunft isverymuchamodern rationalism,onewhichtakesintoaccountthemostrecentdevelopmentsinlogicand epistemologysinceLotzeandKant.Thisistrueintworespects.Firstofall,truetohis Kantianprinciples,Cohenthinksthatsomeofthefundamentalideasofreligion shouldbegivenastrictlyregulativereading,accordingtowhichtheyprescribetasks forlife.Theyshouldnotbeinterpreted,therefore,asconstitutiveprinciples,asifthey describesomekindofontologicalrealmorentitybeyondthenaturalworld.Thisis true,forexample,forideaslikethekingdomofGod.ThekingdomofGodisfor Cohennotasupernaturalrealmwheresoulsdwellinpeaceandharmonybutanideal foraction,thegoaltobetterourlifeinthisworldsothatpeaceandjusticeendure amonghumanbeingsonearth.WhatallthismeansisthatCohen’sreligiousidealis verymuchthis-worldly,inthatitenvisionsitsidealsbeingrealizedhereonearth ratherthaninsomeimaginaryheaven.Second,Cohendoesnotthinkthatthe philosophyofreligionrestsuponanew,moresubtleproofoftheexistenceofGod. Heacceptsthecritiquethathasbeenmadeagainsttheseproofs.Thereasonthat CohendoesnotresthisfaithonaprooffortheexistenceofGodisthathedoesnot thinkthatGod exists inthe firstplace.Existence,heinsists,isjustnotanappropriate concepttoapplytoGod.Cohenmakesthispointbecauseheverymuchacceptsthe distinction,whichwas firstmadebyLotze,betweenexistenceandvalidity,sothatitis onethingtoaskifapropositionisvalidortrueandquiteanothertoaskwhetherit

correspondstoanythingthatexists.Followingthatdistinction,Cohencontendsthat theideaofGodhasvaliditybutthatitdoesnothaveexistence.Thevalidityofthe ideaofGodrestsuponitsbasisintheprinciplesofmorality,whichhaveanormative statusandwhichdonotdescribeexistenceinanyway.Theseprinciplesstillhave validity,however,becauseeveryrationalperson should givehisorherassenttothem.

Fourthlyand finally,theleastunderstoodbutperhapshismostimportantachievement,CohenreinvigoratedtherationalismoftheEnlightenmentthroughthephilosophicalmethodologyofhiscriticalidealism.Rationalismwouldnolongerseekits foundationinallegedlyself-evidentaxioms, firstprinciplesorintuitions,butinthe rigorousemploymentofamethodofenquiry.Cohen’snewrationalismgrewoutofhis logicistinterpretationofKant’sidealism,whichisthesourceofhisnewmethod.Since Cohen’srationalismgrewoutofhisidealism,itisnecessarytosayafewwordsaboutit. Cohen’sidealismisverymuchasynthesisofPlatoandKant.Thissynthesis consistsinCohen’sKantianinterpretationofPlato,whichhe firstputforwardin 1866,andwhichhespenttherestofhislifeelaboratingandrefining.Accordingto thisinterpretation,thePlatonicideaisbestunderstoodintermsofKant’scritical methodorwhatCohenalsocalled “themethodofhypothesis”.Thismethod,as Cohenexplainsit,consistsintwobasictasks: first,givingananalysisofaconcept,i.e., breakingitdownintoitssimplerelements;and,second,justifyingorprovidinga foundationforit.Itistheveryessenceofthecriticalmethod,Coheninsists,thatit hasnostoppingpoints,thatthedemandforjustificationmustalwaysbemade,andthat itnevercomestoanend.Nomatterhowobvious,simple,orbasicaprincipleappearsto be,itisstillnecessarytoseekitsgrounds,itshigherjustification.Itistheverynatureof reasontodemandareason,anaccountorjustificationforourbeliefs;anditisa violationofreasontorefusetoanswer,atanypoint,thesimplequestion ‘Why?’

Becauseitgivescentralitytothecriticalmethod,Cohenoftencalledhisidealism “criticalidealism ”,thetermoncepreferredbyKanthimself.Acriticalidealismwas onethatappliedthecriticalmethodconsistentlyandradically,sothataphilosophy hadnoarbitrarystoppingpoint,andthereforenoelementofdogmatism.Butthis criticalmethod,whichrepresented “thespirit” ofKant’sphilosophy,alsomeant turningagainstits “letter”,sothatonnoaccountdidCohen’scriticalidealism resemblethatofKant,evenifitwasinspiredbyit.Cohen’scriticalidealismturned againstthoseaspectsofKant’sphilosophythatseemedtorepresentanartificialand dogmaticstoppingpointforenquiry.Asbestrepresentedbyhis1902 Logikder reinenErkenntnis,Cohen’scriticalidealismisanidealismwithoutapassivesensibility,withouttheaprioriintuitionsofmathematics,withoutagivenmanifold,and withoutathing-in-itself.Itisanidealismofpurethoughtbecauseonlythatisa thoroughgoing critical idealism.

ItwastheveryessenceofCohen’srationalismthatreasonconsistsnotinany specificaxioms,principles,orintuitionsbutinamethod,the searchforthereasons foraxioms,principles,orintuitions.Theproblemwithtraditionalformsofrationalismisthattheyclaimedto findself-evidenceincertainaxioms,principles,or intuitions,asiftheserepresentedthe neplusultra beyondwhichenquirycouldnot go.Theseclaimswereproblematic,however,becausetheycouldnotsettleskeptical doubtsorgiveanaccountofthemselves.Cohenadvisesustodropthedemandfor certaintyandfoundationsandtoengageinsteadinthe search or quest forthem.

Cohen’srationalismisthereforeaformofanti-foundationalism,thoughitdoesnot leaveusinaboatontheopensea;forthereisalwaysagoalbehindthissearchor quest,theattempttoclimbeverhigherinthenever-endingladderofjustification.

AsimportantasthecriticalmethodisforCohen’sphilosophy,thetrendinrecent interpretationsofhisworkistoignoreitandtostresstheapparentmystical dimensionofhisphilosophy.ScholarsseeinCohen’sinterpretationofKantthe influenceofFichte’stheoryofintellectualintuition(Köhnke),orinCohen’sinterpretationofPlatotheinfluenceofJewishmysticism(Adelmann).Thefatherofthese recentmysticalinterpretationsofCohenwasnolessthanFranzRosenzweig,who sawCohen’slatereligiousphilosophyasanabandonmentoftheidealistlegacyanda turntowardamoreexistentialistphilosophy.Theweaknessofalltheseinterpretations,Ibelieve,isthattheydonotseethefullsignificanceofCohen’scritical method,whichmadehim,explicitlyandemphatically,rejectallformsofmysticism. Instressingthemysticalovertherational,theseinterpretations,Ithink,betraythe criticalspiritofCohen’sidealism.TheinterpretationofCohen’sthoughtofferedhere isthereforeastrictlyandthoroughlyrationalisticone,repudiatingallitsapparent elementsofmysticism.

Primafacie thereweretwodifferentintereststhatpreoccupiedCohenthroughout hisintellectualcareer:onewasphilosophyandtheotherwasJewishcultureand religion.Thesecondwasjustasimportantforhimasthe first.CohenwasbornaJew, andthathesteadfastlyremainedforhisentirelife,rejectinganythoughtofconversion,evenwhenitseemedcrucialforhisacademiccareer.TheinterestinJewish cultureandreligionbeganearlyanditpersisteddespitehisdecisionnottopursuea rabbinicalcareer;indeed,itonlyintensifiedwithage,sothatthelastdecadeofhislife wasalmostentirelydevotedtoJewishtopics.

Itismisleadingtotalkaboutthesetwointerestsasiftheywerereallydistinct,oras ifCohen’sJewishwritingsmarkasubsidiary fieldtohisphilosophy.Cohensawthe twointerestsasessentiallyone.TheinterestinJewishreligionandculturewaspart andparcelofhisphilosophy,oneapplicationofhiscriticalidealismtothecultural andreligioussphere.ButJudaismwasmorethanjustoneofhisinterests,one applicationofhiscriticalmethod.ItwasalsothemotiveforcebehindCohen’ s philosophy,theinterestfromwhichhisphilosophysprang.Thepointofhiscritical idealism,ashelatersaid,wastoexplainanddefendJewishmonotheism.Critical idealismwasforCohenoneandthesameas “Jewishidealism ” .

Forthesereasons,inthisbookwewilldevoteourselvesespeciallytoanexaminationofCohen’smanyJewishwritings,takingintoaccountthefullscopeoftheir developmentfrom1868until1918.TheJewishwritingsarecentraltounderstanding notonlyCohen’sJewishfaithbutalsohisphilosophicalprinciples.Asithappens, someoftheclearestaccountsofhisidealistprinciplesareinthelaterJewishwritings whenCohenwasforcedtoexplainhisideastostudentsorabroaderpublic.The historianofphilosophythereforehastostudytheJewishwritingswithasmuchzeal andeffortasthelargerphilosophicaltreatises.

NowhereisthetragedyofCohen’sidealismmoreapparentthaninhisviewson Judaism.CohensawJudaismasthesourceofandmodelforthereligionofreason; thoughitwasnotthe only rationalreligion,itwasthe first suchreligion,andindeed theparadigmforallotherreligionsinsofarastheywererational.Astheadvocateof

thereligionofreason,CohenstoodfortheEuropeanidealofJewishthought, accordingtowhichJewsplayedavitalroleasthepreserversandpropagators ofenlightenedandhumanistvalues.Enlightenmentandhumanismwerecore Europeanvalues;buttheywerealsocentraltotheJewishtradition.Zionism,therefore,wasamovementthatCohenopposedheartandsouleversinceitemergedon theGermanintellectualsceneattheendofthenineteenthcentury.Cohenbelieved thatGermany,notPalestine,wastheproperfatherlandofGermanJews.Hewas confidentintheforcesofassimilationinGermanculture,andbelievedthatfurther intellectualandculturalprogresswouldendwithasymbiosisofGermanandJew. Weallknownow,withthebene fi tofhindsight,thatCohen’soptimismwas mistaken.Arguably,though,itwasnotC ohenwhowasmistaken;herepresented thebestidealswhichhumanitycouldachieve;thedeepererrorlaywithhumanity forfailingtorealizethem.

Cohen’sintellectualdevelopmentwasremarkablystableandsteady,movingin onedirectionfromhisearliesttohislastyears.Thereisnothingliketheconstantly shiftingpositionsofKant’spre-criticalyears,whenKantwouldmovefromempiricism,toskepticism,andthentorationalism.Thereisalsonothingontheorderofthe dramaticreversalsinpositioncharacteristicofFichte’sorHegel’sintellectualdevelopments,whichmovefromanearlycriticalpositiontowardafull-blownmetaphysics.Comparedtohisidealistpredecessors,Cohen’sintellectualdevelopmentshows muchmorestabilityandunity.Thisisnottosay,however,thatCohen’sintellectual developmentisentirelyconsistent,thegrowthofasinglegermwithoutreversalor retraction.TheunityinCohen’sintellectualdevelopmentismoreinitsdirection thaninitsdoctrine.Withoutacknowledgmentoradmission,Cohenwouldsometimescontradicthisearlierviewsandmoveoffinanapparentlynewdirection.But evenwhenthishappens,onecanseethatthenewdirectionwasalreadyimplicitand inchoateintheold,adevelopmentofwhatlaydormantandobscureinearlierideas.

Inthe fieldofepistemology,thereisaveryvisiblebreakbetweenCohen’searlyand laterwritings.ThisprimarilyconcernsthestatusoftheKantiandualismbetween understandingandsensibility.Inhiswritingsupuntil1896Cohenexplicitlyupheld thisdualism;butafterthatitisabandoned;andinhis1902 Logikderreinen Erkenntniss heexpresslyrepudiatesit.Theargumentcanbemade,however,that thedualismalwayshadatenuousholdonCohen’sthinking,andthatfromthevery beginningtheseedsofitsdestructionhadalreadybeensown.Thefundamental principleofCohen’s1870 KantsTheoriederErfahrung thatweknowapriori onlywhatwecreate foreshadowshislaterprincipleoforigin,accordingtowhich allknowledgehastobepositedandgroundedinpurethought.

Inonerespect,though,CohendidremainloyaltoKant’sdualisms.Althoughhe eventuallyrejectedthedualismbetweenunderstandingandsensibility,heaffirmed thedualismbetweenthenormativeandthefactual,valueandexistence.Buthecame toaffirmthislatterdualismonlybyrejectinghisearlySpinozism,whichinvolveda monismthatfusedtherealmsofvalueandexistence.By1872,Cohenabandonedhis pantheismandcametoaccepttheKantiandualismbetweenvalueandexistence,a positionwhichheclungtofortherestofhislife.Cohen’sshiftingattitudestoward Spinoza,whichmovefromdeepadmirationtouttercontempt,representoneofthe mostdramaticdevelopmentsinhisotherwisestablephilosophicalcareer.

ThebreakbetweenCohen’searlyandlaterwritingshasledsomescholarstoseea directioninCohen’sthoughtfromcriticaltoabsoluteidealism,asifCohen’srejection oftheKantiandualismscamefromhisaffirmationofasupra-rationalistdoctrinelike thatofHegel.WewillseeinChapter11,however,thatthisinterpretationcomesfrom amisconceptionofCohen’slaterlogic,whichcannotbeinterpretedinmetaphysical terms.Cohen’slaterprincipleofpurethoughthastobeunderstood,soIwillargue,in strictlyregulativeterms,asanidealforenquiry.Fromthebeginningtotheendofhis intellectualdevelopmentCohenstressedthefundamentalimportanceofaregulative ratherthanconstitutiveinterpretationoftheprinciplesofreason.Onlysuchareadingis consistentwithCohen’sphilosophicalmethodofhypothesisasoutlinedabove.

InhisthinkingonJewishissuesCohen’sthoughtwas,atleastingeneralandonthe whole,consistentandstable.AllhislifeCohenrepresentedaliberalreformist standpoint;hestoodforthesamehumanistandcosmopolitanideals.Heretoo, though,itwouldbeamistaketothinkthatCohenneverreversedhimselforchanged hismind.Inhisearly1880essay EinBekenntniβ inderJudenfrage Cohenstrivedto findthecommondenominatorbetweenJudaismandChristianity,asiftheywere essentiallyonereligion;butinlateryearsheabandonedtheseecumenicalefforts, whichlednowhere,andstressedinsteadthedoctrinaldifferencesbetweenChristianityandJudaism.CohenneverceasedtostresstheracialaffinitiesbetweenJewsand Germans;butinhislateryears,inthefaceofincreasinglyvocalracialantisemitism, hedeclaredthatracewasnotarelevantorimportantfactorintheJewishquestion.

ItisoftenthoughtthatthegreatestintellectualriftinCohen’sintellectualdevelopmenttakesplaceinthe fieldofphilosophyofreligion.FranzRosenzweigfamously arguedthat,inhis finalyears,Cohencompletelyabandonedtheidealisttraditionfor areligiousphilosophythatfocusedontheexistenceoftheindividual.Theindividual,so Rosenzweigargued,felloutoftheconfinesofCohen’ssystem;butitwaspreciselythe needsoftheindividualthathadtobeaddressedinaphilosophyofreligion.Weshallsee inChapter18,however,thatRosenzweig’scasenotonlylacksevidencebutisalso flatly contrarytodoctrinesthatCohenneverabandoned.ThebestwaytounderstandCohen’ s doctrineofcorrelation,whichiscentraltohisphilosophyofreligion,is,yetagain,asa regulativeideal.Cohen’sphilosophyofreligion,aswewillportrayitinChapter18,is nottheabandonmentbuttheincarnationofhiscriticalidealism.

DespitethesporadicshiftsinCohen’sintellectualdevelopment,therewasalways oneconstantthemethroughout:theaffirmationof,andallegianceto,criticalreason. CohenneverceasedtobeloyaltothefundamentalvaluesoftheEnlightenment: tolerance,cosmopolitanism,humanism,andfreedom.But,aswehaveseen,his allegiancetotheEnlightenmentwasbynomeansuncriticalordogmatic.True Enlightenment,asCohensowellunderstood,isaself-criticalEnlightenment,one thatdoesnotallowreasontoeverrestanddemandsthatitalwaysexamineitself.Itis chieflyforthisreason,Iwouldsuggest,thatCohen’sphilosophywillremainwithus forsometime.Justasthevalueofacriticalreasonistimeless,soshouldbethelegacy ofHermannCohen.

EarlyYears,1842–1865

1.HomeandFamily

At8:00inthemorning,July4,1842,¹HermannJescheskelCohenwasborninthe littletownofCoswig,Germany.LyingonthewestbankoftheElbe,12kilometers westofWittenberg,whichwasthebirthplaceoftheReformation,and15kilometers eastofDessau,whichwasthebirthplaceofMosesMendelssohn,Coswigwasasmall, sleepytowninAnhalt,Saxony.AlthoughCohenleftthetownin1853togotoschool inneighboringDessau,hismemoriesandloyaltiesforeverremainedtiedtoCoswig. Thiswashishome,thiswashis Vaterstadt,thiswaswherehisbelovedparentslived. Whentherewereholidaysatschooloruniversity,Cohenwouldhappilyreturnto Coswig.Inlateryearshefondlyrememberedhishometownasanalmostidyllicplace forchildhood. “Ioftenhavethoughtthatonlyasmalltowncanbeahome,becauseonly therecanonegotopublicschool[Volksschule],growupwithchildrenfromthemiddle andworkingclasses,andbecauseonlytheredoesthecountryside flowintothecity.”²

Inthe1860sCoswighadonly4000inhabitants.Ofthese,theJewswereaverytiny minority.Some fiftyorsixtylivedinCoswig,aroundtwelvefamilies.Therewasonlyone synagogueintown,andthecongregationwassometimestoosmalltoholdservices.The JewsseemtohavebeenwellintegratedintoCoswig.Thelocalroyaltywereveryfriendly towardthem,whoseresidencetheynotonlytoleratedbutcultivated.³

HermannwastheonlychildofGersonCohen(1797–1879)andFrederikeSolomon(1801–1873).Thesonhadalovingrelationshipwithbothparents,whoadored, supported,andencouragedhim.TheCohenfamilywasverypoor,becauseGerson’ s onlysourceofincomewashisscantysalaryasaschoolteacherandcantorofthelocal synagogue.ThefamilygotbyonlybecausetheveryresourcefulFrederikeranfrom herhomeasmallbusinesssellinghatsandfashionaccessories.Thisgavethefamily justenoughmoneytoprovidefortheirson’seducation.

Theformative figureinHermann ’slifewashisfather,GersonCohen.After receivinghistrainingina Yeshiva inEastPrussia,Gersonbecamenotonlythe cantorintheCoswigsynagogue,butalsoateacherofHebrewandreligioninthe smallschoolbuiltfortheJewishcommunity.Gersonwasnotonlywelleducatedin

¹Thebirthdateandhourisstatedinthe PersonenstandsregisterderjüdischenGemeindeCoswig.Itis reproducedin HermannCohen(1842–1918),ed.FranzOrlik(Marburg:UniversitätsbibliothekMarburg, 1992),p.13.

²LettertoKurtEisner,August14,1902,inHermannCohen, AusgewählteStellenausunveröffentlichen Briefen,ed.BrunoStrauβ (Berlin:AkademieVerlag,1929)(unpaginated).

³AccordingtothetestimonyofSalomonSteinthal, ‘AusHermannCohensHeimat’ , AllgemeineZeitung desJudenthums,Jahrgang82,Nr.19(Mai10,1918),222–5,herep.223.

theTalmudictradition,buthewasalsoself-taughtinsecularsubjects.Hewould oftenreadGermanandFrenchliterature;anditwassaidthathecouldread Maimonides’ GuideforthePerplexed as fluentlyinFrenchasinHebrew.According toSalomonSteinthal,oneofhisstudents,Gersonwasamuchlovedandeffective teacher.⁴ HisHebrewlessonsweresosuccessfulthatallhisstudents,eventheleast talented,learnedtotranslatethePentateuchbeforetheyleftschoolat14.Gerson’ s favoritepupilwas,ofcourse,hisson,whomhetaughtHebrewandtheTalmudatan earlyage.WhenHermannwasastudentinDessau,Gersonwouldvisithimevery SundaysothathecouldteachhimtheTalmudanddiscussreligion.Cohenlatersaid that,thankstohisfather,hedevotedmorethantenyearsofhisyouthtothestudyof theTalmud.⁵

Hermann’sdebtstohisfatherwerenotonlyinreligion.Justasimportantforhis educationwashisfather’spolitics.Gersonstoodpoliticallyontheleft,justashisson wouldlaterdo.Gersonwasastrongdemocrat areaderofthe BerlinerVolkszeitung andasocialist.Hisegalitariansympathiesweresostrongthatthe Dienstmädchen wouldsitatthefamilydinnertable.GersonalsoimpartedhisGermannational sympathiestohisson.In1870,withthestartofthewarwithFrance,hewenttopray forthetroopsintheEvangelicalchurchbecausehisownsynagoguewastoosmallto holdservices.

GersonCohenwasmuchappreciated,byChristiansandJewsalike,asapillarof theCoswigcommunity.Christianpastorsadmiredhimforhiswisdomandlearning. In1876theeldersofCoswigwantedtonamehiman Ehrenbürger,thoughthisfailed onlybecauseonevotewascastagainsthim.WhenHermannbroughthiselderly fathertoMarburgforhis finaldays,themedicalspecialistinchargeofhiscarestated: “Wheneveroneisgreetedbyyourfather,onehasthefeelingthatonehasjustbeen blessed.”⁶ PerhapsthegreatesttributeofallcamefromLudwigGeiger,thefatherof reformedJudaism,whocalledGerson “thesoulandconscienceofJudaism ” . ⁷

JusthowmuchGersonCohenmeantforhissonwassummedupbyHermann himselfafterhisfather’sdeathin1879.HewrotehisfriendandstudentAugust Stadler,August4,1879: “LetmetellyouthatwhatIammorally,andstillstrivetobe, Iowetomyfather;butIalsorecognizeasdefinitelyrootedinhimmuchofmy spirituallife,thefoundationofmyreligiousviews.”⁸

OfhismotherCohenspokewithnolessreverence.Shewasdevotedtohersonand sacri ficedmanythingsforhim.Herson,sheseemedconvinced,wouldbesuccessful. “Myson,youarenoSchlemihl”,sheusedtosaytohim.⁹ In1885,sometwelveyears afterherdeath,Cohenwroteabouther: “Andmydearmotherwasapurenature which,everyCoswigerwouldconfirm,wastobedescribedwiththesingleword:love.

⁴‘AusHermannCohensHeimat’,p.223.

⁵ HermannCohen, ‘DieNächstenliebeimTalmud’,in JüdischeSchriften,ed.BrunoStrauβ (Berlin: Schwetschke&Sohn,1924),I,145.

⁶ Steinthal, ‘AusHermannCohensHeimat’,p.224. ⁷ Ibid.

⁸ HermannCohen, BriefeanAugustStadler,ed.HartwigWiedebach(Basel:SchwabeVerlag,2015), p.121.

⁹ AnMathildeBerg,January14,1886, Briefe,AusgewähltundherausgegebenvonBerthaundBruno Strauβ (Berlin:Schocken,1939),p.58.

Fromher17thyearshelovedmyfatherand12yearslatershecouldmarryhim.And untilher72ndyearsheworkedtirelesslyandproudlysothatheronlysoncouldbe independentandrompandplayuntilhisyearsofmaturity.”¹⁰

Untilhewasten,HermannattendedprimaryschoolinCoswig.Therehelearned Germangrammar,history,andliterature.TheprincipaloftheschoolwasJulius Hoffmann,whowasawell-knownauthorofchildren’sbooks.RobertFritzsche,Cohen’ s laterfriend,wrotethatHoffmannoncetoldtheschoolchildrenthestoryofhow,after thebattleofMühlberg,PrinceWolfgangvonAnhalt-Köthenhadtoleavehisland becausehenolongerfeltsecureamonghisownpeople.¹¹CohentoldFritzscheofhis reactiontothestory: “Icriedbitterly.Thiseventmadethesameimpressiononmeasthe saleofJosephbyhisbrothers.” ForFritzsche,thestoryrevealedhowmuchCohen’ s educationhadfusedJewishandGerman-Protestantculture.

HermannleftCoswiginearly1853,whenhewasonlyten,tobeginhighschoolin Dessau.¹²Inthe1850sthe HerzoglicheHauptschule,astheschoolwasthenknown, wasdividedintotwohalves:a Gymnasium,whichfocusedonancientlanguages;and a Real-Schule ,whosecurriculumwasEnglishandnaturalhistory.Cohenwas enrolledasastudentinthe Gymnasium,wherehestudiedforfouryears.Hewas oneof45students,whoconsistedoverwhelminglyofthesonsofwell-to-doDessauer bourgeoisie.Cohenwasprobablyoneofthe firstJewishstudentstoattendtheschool. ShortlyafterhisarrivalinDessau,Hebrewwasdroppedfromthecurriculum.Itwas perhapsnotleastforthisreasonthatGersonCohenwasanxioustoteachhisson HebrewandtheTalmudonweekends.

Aftercompletinghis Sekunda,hismid-levelexams,Cohenleftthe Gymnasium.He stillhadfouryearstogobeforehis Abitur,his finalexambeforeuniversity.ButCohen, asweshallsee,hadotherplansthantheuniversity.The Abitur wouldhavetowait.

SuchwereCohen’ s firstyears.Alovingfamily,anidyllichometown,theabsence ofethnicandreligioushatred thesewerethestuffofaprotectedandhappy childhood.Thesheerinnocenceofhisearlylifewouldseemtomakehimnaïve andvulnerable;butitprovedtobeinsteadthesourceofhisstrength,self-confidence, andcreativity.HermannCohenwasaluckychild;buthislaterlifewouldnotbeso fortunate.Whathehadbeengivenasachild tranquilityandtoleration hewould haveto fightforasanadult.

2.TheBreslauSeminary

InOctober1857,atthetenderageof15,theyoungHermannCohenwenttoBreslau tobeginhistrainingasarabbi.Heattendedtherecentlyfounded JüdischtheologischesSeminarFraenckelscherStiftung,¹³whichopeneditsdoorsinAugust

¹⁰ AnMathildeBerg,November25,1885, Briefe,p.57.

¹¹RobertArnoldFritzsche, HermannCohenauspersönlicherErinnerung (Berlin:BrunoCassirer Verlag,1922),p.7.

¹²OntheDessauschool,seeOrlik, Cohen,pp.17–18.

¹³Onthefoundingandhistoryoftheinstitutionforits firsttwenty-fiveyears,seeJacobFreudenthal, Dasjüdisch-theologischeSeminarFränckelscheStiftungzuBreslau.AmTageseinesfünfundzwanzigjährigen Bestehens,den10.August1879 (Breslau:Grass,Barth&Comp,1879);andforits first fiftyyears,M.Brann,

1854.Thisinstitution,whichwasthemodelforfutureseminariesinHungary, Austria,andtheUnitedStates,wouldhaveanillustrioushistory.Amongitsfaculty weresomeofthebestmindsinJewishlearningofthenineteenthcentury:thehistorian HeinrichGraetz(1817–1891),thephilologianJakobBernays(1824–1881),andthe historianofphilosophyManuelJoël(1826–1890).Allofthemwouldbeteachersof Cohen.Itwasespeciallyfortunateforhimtohavebeeneducatedbysuchfaculty,andto havestudiedatsuchaninstitutioninitsformativeyears.

TheBreslauseminarywasfoundedbyJonasFränckel,arichbachelorandprominentphilanthropistwhoseestateheldgenerousprovisionsfortheestablishmentofa seminaryinBreslau.ItwasFränckel ’sintentionthatthe firstheadoftheseminary shouldbeAbrahamGeiger(1810–74),theleaderofthereformmovementinJewish theology.ButtheexecutorsofFränckel’swillbelievedthatGeigerwastooradicalto gaintheconfidenceoflocalcongregations.So,insteadofGeiger,theyappointed ZachariasFrankel(1810–1875),¹⁴ whohadgainedrenownasthechiefrabbiof DresdenandastheleadingspokesmanforconservativeJudaism.Frankelwould remaininthepostuntilhisdeathin1875.

ThesloganofFrankel’sadministrationwas “moderatereform”.Inthegreatbattle betweenorthodoxandreformersinnineteenth-centuryJudaism,Frankelstruggled to findamiddlepath,astancesomewherebetweentheextremes.Hefoundeda positionhecalled “positive-historical” Judaism,wherethe “positive ” stoodforthe revealedlaw,andwherethe “historical” referredtothelaw’sdevelopmentinhistory. WhiletherevealedlawiseternalandgivenbyGoddirectlytoMosesonSinai,the historicallawchangesthroughhumaninnovationandinterpretation.Regardingthe historicaldimensionofthelaw,Frankelbelievedthatitwasdesirable,indeed necessary,tostudyitusingcriticalandhistoricalmethods.Hewasdevotedto LeopoldZunz’sidealofthe WissenschaftdesJudentums,thestudyofJudaismusing moderncriticalandhistoricalmethods;¹⁵ buthewasalsoconfidentthatthisstudy wouldleadnottodoubtbuttoapurerfaith,thediscoveryofthespiritualcoreof Judaism.Frankel’sidealwasthustowed,asheputit, “theseriousnessoffaithwith thesacredseriousnessofscience”.¹⁶ Hehopedthathisseminarywouldembodythis ideal,thatitcouldsomehowcombinefreedomofscientificresearchwithfaithin traditionalJudaism.TheyoungCohensharedFrankel’sideal.

ThecurriculumoftheBreslauseminaryconsistedmainlyinreligioussubjects,but itwasnotableforalsoincludingsecularones.Thereligioussubjectswerebiblical exegesis,Hebrewgrammar,Jewishhistory,Talmudiccivilandcriminallaw,homiletics,pedagogics,andphilosophyofreligion;thesecularoneswereLatinandGreek

Geschichtedesjüdisch-theologischenSeminarsinBreslau.FestschriftzumfünfzigjährigenJubiläumder Anstalt (Breslau:Th.Schatzky,1904).

¹⁴ OnZachariasFrankel,seeBrann, Geschichte,pp.28–40;MichaelMeyer, ResponsetoModernity: AHistoryoftheReformMovementinJudaism (Detroit:WayneStateUniversityPress,1988),pp.84–9;and IsmarSchorsch, FromTexttoContext:TheTurntoHistoryinModernJudaism (Hanover,NH:Brandeis UniversityPress,1994),pp.13–15,190–1,255–63.

¹

⁵ OnZunzandhisidealofa WissenschaftdesJudentums,Schorsch, TexttoContext,pp.205–32;and Meyer, ResponsetoModernity,75–7,and TheOriginsoftheModernJew:JewishIdentityandEuropean CultureinGermany,1749–1824 (Detroit:WayneStateUniversityPress,1967),pp.144–82.

¹⁶ Brann, Geschichte,p.39.

classics.¹⁷ Usually,thestudenthadtoattendlecturesforsixteenhoursaweek.To receiveadegree,thecourseofstudytooksevenyears,alongtimeevenbythe standardsoftheday.

WithallthefamousprofessorsintheBreslauseminary Bernays,Graetz,and Joël Cohenhadespeciallyformativerelationships.Helaterrecalledthat “the spiritualbond” whichunitedtheseprofessorswas “anextraordinarydiligence” (ein Riesenfleiβ).¹⁸ Theywerecompletelydevotedtotheirstudies,buttheyalsobelievedin theirsocialimportance,whichinspiredthemtobringtheirworktothepublicat large.Theywereindependentmindswhourgedtheirstudentstothinkalongwith them.Inthatway,Cohensaid,thestudentwasmorethansomeonewholearned;he becameateacherhimself.

WithBernays,Cohenhadasomewhatfraughtrelationship.Alreadyinthe1850s BernayshadacquiredareputationasoneoftheleadingphilologistsinGermany. SuchwashisrenownthatTheodorMommsen,thegreatclassicalhistorian,entrusted Bernaysalonetoedithismanuscripts.¹⁹ ButnoneofBernays’ standingintheworld helpedtheyoungCohen.Never,helaterwrote,²⁰ didhegainBernays’ favoror recognition.Herememberedfondlythemanylessonsinclassicalphilologythathe learnedfromhisformerteacher;buthecouldnevergetoverBernays’ coldnessand indifference.Bernayshadanimmenselearning;butheseemedtohavenosoul. “Therewasnoliving,creative,constructivethinkingthatworkedinthispowerful machine. ”²¹CohendislikedBernays’“Schellingianmysticism”;andhefoundhis “deepestdeficiency” inhisattitudetowardphilosophy.Bernaysknewphilosophy, andheunderstoodit,butonlyasaphilologianandhistorian.Cohencouldnot fathomwhyBernayshadnointerestinexplainingtheideasofJudaismtohis Christianfriends.AlthoughBernays,averyorthodoxman,wasproudofhisJudaism, hewasnotdiscreetabouthowheshowedthisinsociety.Therelationshipwith BernaysmusthavebeenespeciallydifficultforCohenbecauseFrankeltoldhimmany yearsafterhelefttheseminary: “IfBernaystreatedyoubetter,youwouldhave perhapsstayedwithus.”²²

WithGraetz,Cohenhadanothertryingrelationship.Duringthe1850swhenhe wasteachingattheseminary,Graetzhadalreadypublishedfourvolumesofthebook thatwouldeventuallymakehimfamous: GeschichtederJuden.²³Partofthesourceof Cohen’sfrictionwithhisteacherlaywithGraetz’spricklypersonality,butanother partrestedwithhisorthodoxy.Inhisearlyyears,Graetzhadbeenastudentof

¹⁷ Accordingtotheprogramoutlinedbythegoverningboardoftheseminary, ‘ZurGeschichtedes jüdisch-theologischenSeminars’ in ProgrammzurEröffnungdesjüdisch-theologischenSeminarszuBreslau, August10,1854(Breslau:Korn,1854),p.5.

¹⁸ SeeCohen, ‘EinGruβ derPietätandasBreslauerSeminar’,in JüdischeSchriften II,418–24,esp.p.422.

¹⁹ OnBernays’ relationshipwithMommsen,seeUffaJensen GebildeteDoppelgänger:BürgerlicheJuden undProtestantenim19.Jahrhundert (Göttingen:Vandenhoeck&Ruprecht,2005),pp.64–7.

²⁰ OnCohen’srelationshipwithBernays,seeCohen’sownaccountinhis ‘EinGruβ derPietätandas BreslauerSeminar’,in JüdischeSchriften II,418–24,esp.pp.419,420–1.

²¹Ibid,p.421.²²Ibid,p.419.

²³HeinrichGraetz, GeschichtederJudenvondenältestenZeitenbisaufdenGegenwart (Leipzig:Leiner, 1897–1911),11vols.OnGraetz,seeSchorsch, FromTexttoContext,pp.191–3,278–93;andtheportraitin HansLiebeschütz, DasJudentumimdeutschenGeschichtsbildvonHegelbisMaxWeber (Tübingen: J.C.B.Mohr,1967),pp.132–56.

SamsonRaphaelHirsch(1808–1888),oneofthechiefspokesmenfortheorthodox cause.ThoughGraetzbegantodriftawayfromHirschduringhisstayinthe seminary,hestillhadhisdifferenceswiththeliberals,whichhedidnothesitateto expressopenly.DuringhislecturesCohenoftenfeltuncomfortable.Hetellsushow Graetz’sgazewould fixonhimduringhislectures,andhowheoncequestioned Graetz,muchtohisteacher’sdispleasure.Cohen’sdisapprovalofGraetz’sorthodoxy becameevidentlaterduringtheBerlinantisemitismcontroversy.Inhisfamous article ‘UnsereAussichten’,²⁴ whichbeganthatcontroversy,HeinrichvonTreitschke hadsingledoutGraetzforcriticismasaJewunwillingtoassimilateintoGermanlife. RatherthandefendingGraetz,CohenurgedTreitschketoregardhimmoreasan exceptionthananexample.²⁵ ItwasnotperhapsCohen’ s finestmoment.Buthefelt thatGraetz’suncompromisingattitudewasprovidingstimulusandammunitionfor theantisemiticcause.Despitethedifferencesbetweenthem,Cohenlaterrecalled withpleasurehow,in1879afterachancemeetinginKarlsbad,Graetzhadgreeted himwarmlyandhadbeenveryfriendlytowardhim.²⁶ In1917,forthecentenaryof Graetz’sbirth,Cohenwroteatributetohisoldteacher,²⁷ whomheneverceasedto criticizeforhispartisanship,butwhomheneverceasedtoadmireforhisscholarship. HesummeduphisrelationshipwithGraetzthus: “Myrelationshiptothisgreat teacherIcanbestcharacterizeasanunhappylove.”²⁸

OfallhisteachersCohenadmiredmostJoël.²⁹ Hepraisedhimforhisgreat learningandhumanity,forhisopennessandgenerosity,forhisbroadmindedness andphilosophicalcastofmind.JoëlwasfortheyoungCohentheverymodelofwhat aphilosophershouldbe.Whenhejoinedtheseminaryin1854Joëlwasalready famousforhiselegantsermons;buthelaterbecamebetterknownforhisworkasan historianofphilosophy.³⁰ JoëldidpioneeringworkonSpinoza,showingforthe first timetheimportantinfluenceuponhimoftheJewishphilosophyoftheMiddleAges. HistwobooksonSpinoza,³¹whicharestillreadtoday,weremilestonesinSpinoza scholarship.Joëllatergavethelecturesonphilosophyofreligionintheseminary, thoughthisseemstohavebeenafterCohen’stimethere.ItwasperhapsfromJoël thatCohen firstlearnedofKant’sphilosophy.JoëlwasaJewishKantian,seeingin KanttheoneGermanphilosopherofthemodernagewhocouldprovideabasisfor religion.³²ButitisextremelyunlikelythatCohenlearnedanythingaboutKant

²⁴ HeinrichvonTreitschke, ‘UnsereAussichten’ , PreussischeJahrbücher 44(1879),559–76.

²⁵ Cohen’sopinionaboutGraetzappearsinaletterhewrotetoTreitschke,December27,1879.This letterwaspublished,alongwithanearlieronetoTreitschke,byHelmutHolzhey, ‘ZweiBriefeHermann CohensanHeinrichvonTreitschke’ , BulletindesLeoBaeckInstituts 12,Nos.46–7(1969),183–204. Seeesp.p.198.

²⁶‘EinGruβ derPietät’,p.420.

²⁷‘ZurJahrhundertfeierunseresGraetz’ , JüdischeSchriften II,446–53.

²⁸ Ibid,p.453.OnCohen’slaterdiscussionofGraetz,seeChapter17,section8.

²⁹ OnJoël,seeDieterAdelmann,see ‘ManuelJoël’ in »ReinigedeinDenken«,Überdenjüdischen HintergrundderPhilosophievonHermannCohen (Würzburg:Königshausen&Neumann,2010), pp.107–19.

³

⁰ ManuelJoël, BeiträgezurGeschichtederPhilosophie (Breslau:Schletter,1876).

³¹ManuelJoël, SpinozasTheologischer-politischerTraktataufseineQuellengeprüft (Breslau:Schletter, 1870);and ZurGenesisderLehreSpinoza (Breslau:Schletter,1871).

³²SeeManuelJoël, Religiös-philosophischeZeitfragen (Breslau:Schletter,1876).

interpretationfromJoël.HisbookonKantappeared fifteenyearsafterCohen’s,and itadvancesaninterpretationofKantcompletelyatoddswithhisformerstudent.³³

3.TheEndofaRabbinicalCareer

In1861,afteronlyfouryears,CohenlefttheBreslauseminar.Hestillhadthreeyears ofstudyleftto finishhisrabbinicaltraining.Atleasthedepartedongoodtermswith histeachers,whowroteacertificatetovouchforhisperformanceandbehavior.But hisrabbinicalcareerwaseffectivelyover.

WhydidCohengo?Whydidheleavesoearly?ManyyearsthereafterCohen recalledthat “theexternaloccasion” forhisdeparturewas “thedisputeovertradition, whichwasthenstartedbyHirschagainstFrankel”.³⁴ Cohenwasreferringtothe controversybetweenSamsonRaphaelHirschandFrankelwhichbeganinJanuary 1861.Thatdispute,whicharoseafterthepublicationofFrankel’scommentaryonthe Mishna,³ ⁵ concernedtheveryheartofFrankel ’sprogram:whetherthemethodsof criticalandhistoricalscholarshipshouldbeappliedtotheJewishtradition?Although FrankelwascarefultoexceptfromcriticalscrutinythePentateuch,whichhebelieved tobedivinelyrevealedtoMosesonMt.Sinai,heheldthatthemajorsourcesof rabbinicJudaism theMishna,Talmud,Midraschim wereofonlyhumanorigin andthereforecouldandshouldbesubjecttocriticism.ForHirsch,however,thiswas todegradethesetextsbydeprivingthemoftheirdivineauthority.³⁶ Hemaintained thattheentireJewishtradition notonlythewrittenbutalsotheorallaw,notonly thelawitselfbutalsoitsinterpretationasformulatedbyrabbisoverthecenturies wasdivineininstitution,ultimatelygoingbacktoGod’srevelationtoMoseson Mt.Sinai.Inotherwords,theentiretyofthelawwasgivenbyGodtoman;noneofit wascreatedbymanalone.Thelawthereforestoodabovethetribunalofcritique, whichhadcompetenceonlyinjudginghumanreasoning.

Duringthedispute,Hirschbecameverysensitivetothechargethathewasan irrationalist.Althoughhewasindeedattemptingtolimitthepowersofcriticism,he believedthathehadrationalgroundstodoso,giventhatthetribunalofcritiqueheld onlyforthecreationsofmanand “humanthoughtoperations”.Who,afterall,was willingtoquestionthecreationsofGod?Furthermore,heassuredhisreaders,³⁷ the bestauthoritiesinJudaismagreedwithhimthatnotonlythewrittenlawbutalsothe oralinterpretationofthelaworiginatedfromSinai.Ifanyonewasguiltyofirrationalism,Hirschreasoned,itwasFrankelandhisallieswhosimplyassumed,without anyfurtherargumentandcontrarytoallwrittentestimony,thatthelawafterthe

³³Joëlarguesin Zeitfragen,pp.34,37,thatKant’sgreatservicetoreligionwashisthesisthatthethingin-itselfexistsandstandsbeyondhumanknowledge.HearguesagainstapositionlikeCohen’s(pp.38–9).

³⁴‘EinGruβ derPietät’,p.423.³⁵ Darkheiha-Mishnah (Leipzig:Hunger,1859).

³⁶ Hirschexpoundshispositionintwoarticlesinhisjournal Jeschurun,EinMonatsblattzurFörderung jüdischenGeistesundjüdischenLebensinHaus,GemeindeundSchule. See ‘AnmerkungderRedaktion’ , Jeschurun 7(1860/61),Februar1861,pp.252–69;and ‘VorläufigeAbrechnung’ , Jeschurun 7(1860/61), März1861,pp.347–77.OnthebasisofHirsch’sposition,whichcannotbeexploredhere,seeMichah Gottlieb, ‘OralandWrittenTrace:SamsonRaphaelHirsch’sDefenseoftheBibleandTalmud’ , Jewish QuarterlyReview 106.3(2016),316–51.

³⁷ Hirsch, ‘AnmerkungderRedaktion’,p.261.