Introduction

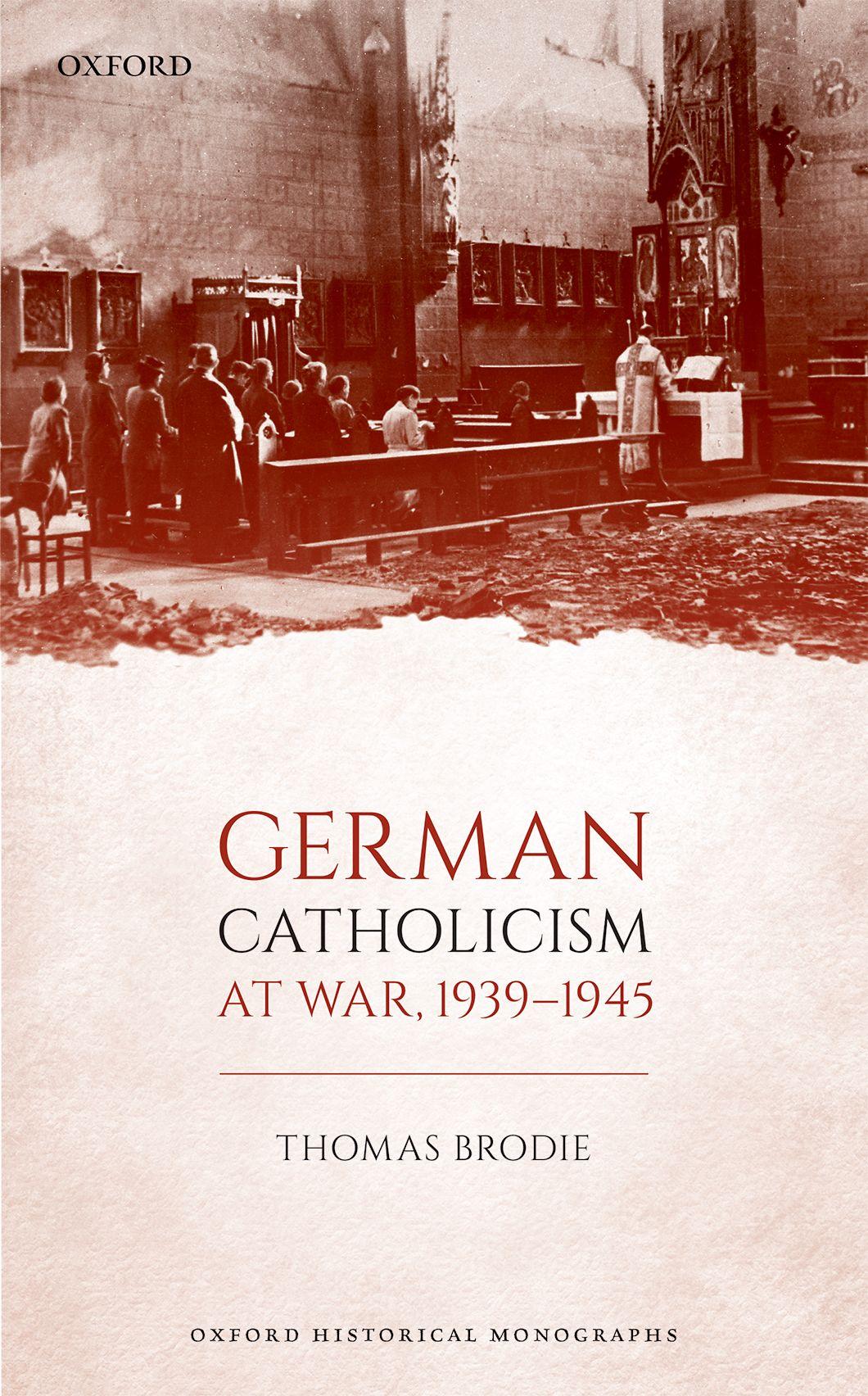

On 27 August 1944, Robert Grosche, a 56-year old parish priest in Cologne, preached to his congregation on Revelation, verses 22: 6–10, concerning the imminence of Christ’s return to pass judgement on the living and the dead. This service did not mark a departure from his usual pastoral practice— Grosche had begun to take Revelation as the basis of his sermons two years earlier, in August 1942. In his diary entry of 27 August 1944, he noted that, ‘The coming of the Lord always means downfall . . . therefore the Book of Revelation is a book of downfalls.’1 As this biblical focus implies, for Grosche, the suffering imposed by the Second World War represented the apocalyptic means chosen by God to return a sinful humanity to divine grace.2 Nevertheless, contained within Grosche’s understanding of the war as a universal penance lay a keen sense of German victimhood. The devastation which loomed largest in his mind was that wrought by Allied bombing on Cologne, with Grosche’s preaching on the Book of Revelation coinciding with this bombardment’s escalation as of summer 1942. As he stated in a letter that June following a heavy raid: ‘my heart bleeds at the sight of such terrible destruction’.3

In marked contrast to Grosche’s reflections on Cologne’s victimhood, in recent decades historians have focused on the ways in which the Nazi state’s war effort involved German society in imperial conquest, colonization and genocide on a vast scale, with ‘ordinary Germans’ acquiring complicity in their regime’s crimes. There is a vast literature on the Wehrmacht’s repeated perpetration of atrocities against enemy populations and prisoners of war, especially in eastern Europe and the occupied Soviet territories. It is now also generally accepted that there was widespread knowledge on the German home front of the Nazi regime’s extermination of European Jews.4

1 AEK, Nachlaß Grosche, 134, diary entries of 27 August and 17 September 1944.

2 AEK, Nachlaß Grosche, 285: Briefe an Frau J., p. 88, letter of 24 March 1944.

3 Ibid., pp. 60–1, letter of 9 June 1942.

4 Peter Longerich, ‘Davon haben wir nichts gewusst!’: Die Deutschen und die Judenverfolgung 1933–1945 (Munich, 2006); Jochen Böhler, Auftakt zum Vernichtungskrieg: Die Wehrmacht in Polen 1939 (Frankfurt am Main, 2006); Ben Sheperd, War in the Wild East: The German Army and Soviet Partisans (Cambridge, MA, 2004); Sonke Neitzel and Harald Welzer,

Given that awareness of these crimes permeated German society as a whole, it is crucial to examine how individuals reconciled them with their pre-existing systems of morality and belief.5 This study analyses what roles religion, and specifically Catholicism, played in shaping Germans’ understandings and experiences of the Second World War. It explores both sides of this problem: how Catholics responded to the genocidal dimensions of the Reich’s war effort, and how they grappled with the challenge of ascribing meaning to personal and communal loss, as attempted by Robert Grosche in his sermons on the Book of Revelation between 1942 and 1944.

Religious belief and practice mattered in wartime Germany. Around 95 per cent of Germans formally belonged to either the Roman Catholic or Protestant Churches during the Nazi era, and beliefs derived from Christian tradition continued to exert a profound influence on popular conceptions of gender roles, sexual morality, and—perhaps most influentially during the Second World War—understandings of death and afterlife.6 As leading Nazis such as Hitler and Goebbels themselves abundantly appreciated, Christian ideas and rituals were far too deeply engrained within German society and culture to contemplate their abolition, and the Catholic and Protestant Churches dominated the provision of life-cycle rituals, such as weddings and funerals, throughout the Third Reich.7 Church attendance remained vigorous in many regions during the 1930s, and, according to one estimate, it was in 1936 that levels of popular participation in Catholic ecclesiastical life (Kirchlichkeit) peaked in twentieth-century Germany.8 As Theo Hurtz, a 19-year old Catholic from Holzweiler, a Rhenish village to the south of M o nchengladbach, noted in his diary on 14 May 1939:

Soldaten—on Fighting, Killing and Dying: The Second World War Transcripts of German POWS (London, 2012).

5 Doris Bergen notes that perpetrators’ religious backgrounds remain understudied, in Doris. L Bergen, ‘Nazism and Christianity: Partners and Rivals? A Response to Richard Steigmann-Gall, The Holy Reich. Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945’, in The Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 42, (1), (2007), p. 32.

6 For formal church membership, see, Doris L. Bergen, ‘Catholics, Protestants, and Christian Antisemitism in Nazi Germany’, in Central European History, Vol. 27, (3), (1994), p. 330.

7 Elke Frohlich (ed.), Die Tagebücher von Joseph Goebbels, Teil II, Diktate 1941–1945, Vol. 6, Oktober–Dezember 1942 (Munich, 1996), p. 131, entry for 16 October 1942, Vol. 3, Januar–März 1942 (Munich, 1994), pp. 545–6, entry for 25 March 1942. See also, Monica Black, Death in Berlin: From Weimar to Divided Germany (Cambridge, 2010); Alon Confino, ‘Death, Spiritual Solace and Afterlife: Between Nazism and Religion’, in Paul Betts, Alon Confino, and Dirk Schumann (eds), Between Mass Death and Individual Loss: The Place of the Dead in Twentieth Century Germany (New York, 2008), pp. 219–31.

8 Thomas Großbolting, Der verlorene Himmel: Glaube in Deutschland seit 1945 (Gottingen, 2013), p. 31; Ziemann, ‘Zur Entwicklung christlicher Religiosität in Deutschland und Westeuropa, 1900–1960’, in Christof Wolf and Matthias Koenig (eds.), Religion und Gesellschaft, Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie, Vol. 65, (1), (2013), p. 112.

‘I very much enjoy attending our local church and a Sunday without mass would be unthinkable for me.’9

During the Second World War, religious faith served as a customary source of consolation and meaning for many on the home and battle fronts.10 As Agnes Neuhaus, a 23-year old Catholic in Münster, wrote to her conscripted husband, Albert, on 18 January 1942:

It is now almost a year since we saw one another, and I sometimes don’t know how it was possible to cope. But the Lord God gives a great deal of strength and I must say that, had I not had prayer and the Church, I would sometimes have despaired.11

At an institutional level, moreover, following the Nazi regime’s abolition of rival political parties and takeover of the previously independent media in 1933, the Christian clergy became the only independent social actor in Germany possessing a public platform to publicize its views concerning current affairs in the form of sermons and pastoral letters. The regime’s intelligence agencies, such as the SS Security Service, (Sicherheitsdienst— SD) accordingly devoted much attention to monitoring the Churches’ activities during the war years, as institutions capable of shaping popular opinion. Revealingly, the SD’s reports of summer 1943, outlining popular reactions to knowledge of the Holocaust, suggest that such feelings of guilt as were present in the population often reflected the influence of religious belief.12

This study dedicates itself to exploring Catholicism’s social, cultural, and political roles in German society during the Second World War. Taking the home front—and most specifically, the Rhineland and Westphalia— as its core focus, it asks how far Catholics supported their nation’s war effort as its genocidal dimensions unfolded, and whether they were able to reconcile national, political, and religious loyalties over the tumultuous

9 DTBA, 425, 496, Tagebuch von Theo Hurtz, 2, p. 124, entry for 14 May 1939.

10 See, Dietmar Süß, Death from the Skies: How the British and Germans Survived Bombing in World War II (Oxford, 2014), pp. 239–99; Nicholas Stargardt, ‘The Troubled Patriot: German Innerlichkeit in World War II’, in German History, Vol. 28, (3), (2010), pp. 326–42. For religion’s considerable influence in Germany during the First World War, Benjamin Ziemann, War Experiences in Rural Germany 1914–1923 (Oxford, 2007 edn); Patrick J. Houlihan, Catholicism and the Great War: Religion and Everyday Life in Germany and Austria-Hungary, 1914–1922 (Cambridge, 2015).

11 Karl Redemann (ed.), Zwischen Front und Heimat: Der Briefwechsel des münsterischen Ehepaares Agnes und Albert Neuhaus 1940–1944 (Münster, 1996), p. 410, letter of 18 January 1942.

12 See, Longerich, ‘Davon haben wir nichts gewusst!’, p. 283; Nicholas Stargardt, ‘Rumours of Revenge in the Second World War’, in Belinda Davis, Thomas Lindenberger, and Michael Wildt (eds), Alltag, Erfahrung, Eigensinn: Historisch-anthropologische Erkundungen, (Frankfurt am Main, 2008), pp. 377–9.

years from 1939 to 1945.13 I analyse how Catholics responded to outbreaks of church–state conflict during the war years, and their reactions to both mounting German defeats at the fronts and Allied bombing over the period 1942–5. In so doing, this project contributes to contemporary debates examining how German society fought on until ‘total defeat’ in the spring of 1945.14 It compares the attitudes of various constituencies within the Catholic ‘milieu’, such as the higher and lower clergy, and the laity, and uses this as a means to test the confession’s internal coherence under the mounting strains of ‘total war’.15 The regional approach adopted provides a practical template for this purpose, in addition to facilitating exploration of the social and cultural histories of religious belief and practice.

The roles of the Christian Churches during the Third Reich have, of course, attracted considerable historiographical interest since the Nazi seizure of power in January 1933. As early as the 1930s, Christian observers outside Germany, such as in Great Britain, devoted much attention to the position of co-religionists under Nazi rule.16 It is nevertheless striking how little scholarly attention has been devoted over the decades since 1945 to the roles played by the churches, laypeople, and religious faith in Germany during the Second World War.17 As recently as 2007, Christoph Kösters could observe that, ‘Until a few years ago the Second World War did not represent an independent topic of investigation within contemporary church history.’18 In 2002, Wilhelm Damberg smilarly noted that, ‘the relationship of German Catholics to the Jews and the Second World War’ was ‘peculiarly weakly illuminated’.19 Ulrich Hehl’s discussion of the years 1939–45 in forty-three pages of his study, The Catholic Church and National Socialism in the Archbishopric of Cologne, is entirely in keeping with this wider historiographical trend, which lasted long after this work’s publication

13 For an appeal for such an approach, Alon Confino, Foundational Pasts: The Holocaust as Historical Understanding (Cambridge, 2012), p. 133.

14 Key works on this issue are Nicholas Stargardt, The German War: A Nation under Arms (London, 2015); Ian Kershaw, The End: Hitler’s Germany, 1944–45 (London, 2011).

15 For ‘total war’ as an analytical concept, see Roger Chickering and Stig Forster (eds), A World at Total War: Global Conflict and the Politics of Destruction, 1937–1945 (Cambridge, 2005); Roger Chickering, The Great War and Urban Life: Freiburg 1914–1918 (Cambridge, 2007), pp. 1–5.

16 See Nathaniel Micklem, National Socialism and the Roman Catholic Church: Being an Account of the Conflict between the National Socialist Government of Germany and the Roman Catholic Church 1933–1938 (Oxford, 1939).

17 Bergen, ‘Nazism and Christianity’, pp. 31–2. An early exception is Gordon Zahn, German Catholics and Hitler’s Wars: A Study in Social Control (London, 1963)—its focus on state coercion is representative of this era’s historiography.

18 Karl-Joseph Hummel and Christoph Kösters (eds), Kirchen im Krieg: Europa 1939–1945 (Paderborn, 2007), p. 9.

19 Wilhelm Damberg, ‘Kriegserfahrung und Kriegstheologie 1939–1945’, in Theologische Quartalschrift, Vol. 182, (2002), p. 321.

in 1977.20 The weakness of specialist literature concerning religion in German society during the war years is indeed reflected in even the finest wider studies of the period. Ian Kershaw’s The End, and Richard Bessel’s Germany 1945, provide little analysis of popular religious mentalities during the final months of Nazi rule.21 It is only in the very recent past that religious belief and community during the war years have attracted increased scholarly attention, with 2014 and 2015 witnessing the publication of two excellent institutional histories of the Wehrmacht’s Catholic chaplaincy.22 Even so, much work on religion during the Nazi era continues to focus primarily on the 1920s and 1930s.23

This neglect of the war years, in addition to the social and cultural history of religious practice and mentality, reflects the institutional approaches and moralizing arguments long dominant within the historiography of religion in Nazi Germany.24 During the early post-war decades, research concerning both major Christian Churches focused on topics such as Nazi anticlericalism, church–state conflict, and acts of resistance by clergymen and laypeople against the regime’s policies. Allied prosecutors at Nuremberg themselves influentially claimed that the Nazis had aimed to ‘eliminate the Christian Churches in Germany’, and conservatives in the Federal Republic sought to consolidate the Churches’ rejuvenated influence in post-war society by portraying them as opponents and victims of the regime.25 In 1968, a key early work by John Conway, revealingly entitled The Nazi Persecution of the Churches, encapsulated both the institutional focus and overall argument characteristic of this early historiography.26 Hehl’s

20 Ulrich Hehl, Katholische Kirche und Nationalsozialismus im Erzbistum Köln (Mainz, 1977), pp. 197–240.

21 Kershaw, The End, p. 72; Richard Bessel, Germany 1945: From War to Peace (London, 2009), pp. 312–18.

22 Martin Row, Militärseelsorge unter dem Hakenkreuz: Die katholische Feldpostal (Paderborn, 2014); Lauren Faulkner Rossi, Wehrmacht Priests and the Nazi War of Annihilation (Cambridge, MA, 2015).

23 See Derek Hastings, Catholicism and the Roots of Nazism: Religious Identity and National Socialism (Oxford, 2010); Kevin P. Spicer, Hitler’s Priests: Catholic Clergy and National Socialism (Illinois, 2008).

24 Note the emphasis on ‘Socio-Theological Implications’ in Zahn, German Catholics, pp. 312–37. For a wonderful historicizing account of why moral arguments have long dominated writing on the Catholic Church during the Nazi era, Mark Edward Ruff, The Battle for the Catholic Past in Germany, 1945–1980 (Cambridge, 2017).

25 The Trial of German Major War Criminals: Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal sitting at Nuremberg, Part I: 20th November to 1st December, 1945 (London, 1946), p. 5; Neil Gregor, Haunted City: Nuremberg and the Nazi Past (London, 2008), p. 123; Martin Brockhausen, ‘ “Glauben im Widerstand”: Zur Erinnerung an den Nationalsozialismus in der CDU 1950–1990’, in Andreas Holzem and Christoph Holzapfel (eds), Zwischen Kriegs und Diktaturerfahrung: Katholizismus und Protestantismus in der Nachkriegszeit (Stuttgart, 2005), pp. 203–34.

26 John Conway, The Nazi Persecution of the Churches (London, 1968).

Catholic Church and National Socialism primarily focuses on areas of institutional conflict between church and state, and does little to explore popular religious beliefs or practices, or potential overlaps in cultural and political attitudes between Catholics and the regime in the Cologne region.27 Areas of conflict and opposition between church and state dominated historiographical interpretations of the relationship between German Catholicism and Nazism during the early post-war decades, not only in Germany itself, but also internationally. Catholics’ responses to the Second World War occupied a peripheral position within this historiography, with Conway’s study dedicating under a third of its pages to the years 1939–45.28

Such approaches and interpretations furthermore remain influential in the subject’s German-language literature, and particularly works of church history (Katholizismusforschung). Catholic history remains a distinct sub-field within German academia, and one extensively separated from ‘profane’ topics.29 To this day, church historians—overwhelmingly members of the religious confession whose history they are writing—frequently work in close cooperation with ecclesiastical patronage.30 In a clear manifestation of this tendency, Norbert Trippen’s biography of Cologne’s Cardinal Frings (1942–69) was commissioned by the latter’s successor, Cardinal Josef Höffner.31 Marginalized by the dominant national-Protestant historical school in Imperial Germany, Catholic historians committed themselves to scholarly defence of their confession’s reputation during that era’s culture wars, a trend consolidated after 1945 by the post-war need to maintain the Church’s status as a victim and resister of Nazism.32 Historians attached to the Commission for Contemporary History (Kommission für Zeitgeschichte) in Bonn continue to focus primarily on Nazi anti-clericalism in their accounts of the years 1933–45, and oppose more critical interpretations, which emphasize forms of Catholic complicity.33 Paradoxically, the lack of

27 Hehl, Katholische Kirche und Nationalsozialismus, pp. 241–8.

28 Conway, Nazi Persecution, pp. 232–327, note also the lack of focus on the war years in Guenther Lewy, The Catholic Church and Nazi Germany (New York, 1964).

29 Oded Heilbronner, ‘From Ghetto to Ghetto: The Place of German Catholic Society in Recent Historiography’, in The Journal of Modern History, Vol. 72, (2), (2000), pp. 454–6.

30 Wolfgang Tischner, ‘Neue Wege in der Katholizismusforschung: von der Sozialgeschichte einer Konfession zur Kulturgeschichte des Katholizismus in Deutschland?’, in Karl-Joseph Hummel (ed.), Zeitgeschichtliche Katholizismusforschung: Tatsachen, Deutungen, Fragen: Eine Zwischenbilanz (Paderborn, 2004), p. 198.

31 Norbert Trippen, Josef Kardinal Frings, Vol. I, Sein Wirken für das Erzbistum Köln und die Kirche in Deutschland (Paderborn, 2003), Vorwort.

32 Heilbronner, ‘From Ghetto to Ghetto’, pp. 455, 495.

33 Oded Heilbronner, ‘The Place of Catholic Historians and Catholic Historiography in Nazi Germany’, in History, Vol. 88, (290), (2003), p. 283. See Wolfgang Dierker, Himmlers Glaubenskrieger: Der Sicherheitsdienst der SS und seine Religionspolitik 1933–1941 (Paderborn, 2002), p. 95; Annette Mertens, Himmlers Klostersturm: Der Angriff auf katholische Einrichtungen im Zweiten Weltkrieg und die Wiedergutmachung nach 1945 (Paderborn,

interest displayed by much ‘profane’ German historiography in religion as a topic of inquiry has also perpetuated its extensive monopolization by church historians, with the recent wave of publications exploring the meanings of ‘national community’ (Volksgemeinschaft) during the Nazi era, containing little discussion of religious confession or identity.34 As a consequence, as Manfred Gailus puts it, ‘the in-house version of the Catholic Church’s historiography’ continues to predominate within much German language literature concerning the Third Reich, with the topic typically analysed through the prism of ‘resistance’.35

Suffice it to say, these traditional accounts of Catholic resistance have been subjected to considerable critique since the 1990s, especially within Anglophone scholarship. With the Holocaust moving to the centre of Third Reich historiography during this period, revisionist works by scholars such as Saul Friedländer, Doris Bergen, Robert Ericksen, and Susannah Heschel have provided us with a host of important insights into the antiSemitic beliefs of many Catholic and Protestant clergymen, and their support of, or lack of resistance to, the Nazi regime’s persecution of the Jews.36

Beth Griech Polelle’s study of Bishop Galen of Münster, a churchman long portrayed during the post-war period as an outright opponent of Nazism for his protests of summer 1941, highlights his passionate commitment to the German war effort against the Soviet Union, and, above all, lack of protest against Nazi Anti-Semitic policies.37 Omer Bartov neatly summarizes this revisionist historiography’s arguments by stating that:

. . . at both the top and lower echelons of the Christian hierarchy, the German Churches, facilitated genocide by a combination of vehement approval, silent

2006); Karl Joseph Hummel and Michael Kissener (eds), Die Katholiken und das Dritte Reich (Paderborn, 2010).

34 Heilbronner, ‘From Ghetto to Ghetto’, pp. 454–5. For the neglect of Germans’ religious beliefs within the Volksgemeinschaft literature, see Michael Wildt and Frank Bajohr (eds), Volksgemeinschaft: neue Forschungen zur Gesellschaft des Nationalsozialismus (Frankfurt am Main, 2009); Martina Steber and Bernhard Gotto (eds), Visions of Community in Nazi Germany: Social Engineering and Private Lives (Oxford, 2014). A useful exception is Manfred Gailus and Armin Nolzen (eds), Zerstrittene ‘Volksgemeinschaft’: Glaube, Konfession und Religion im Nationalsozialismus (Göttingen, 2011).

35 Manfred Gailus, ‘A Strange Obsession with Nazi Christianity: A Critical Comment on Richard Steigmann-Gall’s The Holy Reich’, in The Journal of Contemporary History, Vol. 42, (1), (2007), p. 42; Gailus and Nolzen (eds), Zerstrittene ‘Volksgemeinschaft’, p. 13.

36 Saul Friedländer, The Years of Persecution, 1933–1939: Nazi Germany and the Jews (New York, 1997); Friedländer, The Years of Extermination, 1939–1945: Nazi Germany and the Jews (London, 2008 edn); Robert P. Ericksen and Susannah Heschel (eds), Betrayal: German Churches and the Holocaust (Minneapolis, MN, 1999); Robert P. Ericksen, Complicity in the Holocaust: Churches and Universities in Nazi Germany (Cambridge, 2012); Doris L. Bergen, Twisted Cross: the German Christian Movement in the Third Reich (London, 1996).

37 Beth A. Griech-Polelle, Bishop von Galen: German Catholicism and National Socialism (New Haven, CT, 2002), p. 135.

indifference, or narrow-minded concentration on religious piety resulting in moral numbing 38

Since the 1990s, new scholarship has challenged the emphasis on church–state conflict dominant in older narratives of the Nazi era, (and much recent church history), replacing it with a greater focus on areas of compliance and consensus, above all in relation to the Holocaust.39 This development bears similarity to the overall development of Third Reich historiography since the 1990s, which has increasingly emphasized the German population’s support of the regime and many of its policies, critiquing earlier emphases on popular discontent and opposition.40

Nevertheless, it is discernible that the social and cultural histories of religious belief, community and practice—especially during the war years— have received little attention within this wave of revisionist works. Crucially, their focus on examining the German Churches’ institutional relationship with the Holocaust has underpinned a preoccupation with religious leaders and theologians, and produced an often-moralizing argumentative tone.41 As its title implies, Daniel Goldhagen’s, A Moral Reckoning: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair, represents an extreme manifestation of this trend.42 Less polemical works are nevertheless not immune from this impulse to judge. Beth Griech-Polelle’s fine biography of Bishop Galen claims that, ‘I believe von Galen should be held to a higher standard of accountability because of the office he held and the beliefs he affirmed.’43 Richard Stegimann-Gall’s The Holy Reich also argues that, beyond the immediate historical context of the Third Reich: ‘Christianity, in other words, may be the source of some of the same

38 Omer Bartov and Phyllis Mock (eds), In God’s Name: Genocide and Religion in the Twentieth Century (New York, 2001), pp. 5–6.

39 Important German contributions to this literature, chiefly focusing on Protestantism, are Manfred Gailus, Protestantismus und Nationalsozialismus: Studien zur nationalsozialistischen Durchdringung des protestantischen Sozialmilieus in Berlin (Cologne, 2001); Manfred Gailus (ed.), Täter und Komplizen in Theologie und Kirchen 1933–1945 (Gottingen, 2015); Gailus and Nolzen (eds), Zerstrittene ‘Volksgemeinschaft’; for Catholicism, Olaf Blaschke, Die Kirchen und das Dritte Reich (Stuttgart, 2014); Antonia Leugers, Jesuiten in Hitlers Wehrmacht: Kriegslegimitation und Kriegserfahrung (Paderborn, 2009).

40 Robert Gellately, Backing Hitler: Consent and Coercion in Nazi Germany (Oxford, 2002); Eric Johnson, Nazi Terror: The Gestapo, Jews and Ordinary Germans (London, 2000); Wildt and Bajohr (eds), Volksgemeinschaft; Elizabeth Harvey, Women and the Nazi East: Agents and Witnesses of Germanization (London, 2003).

41 An important early work establishing this trend is, Lewy, Catholic Church and Nazi Germany; more recently see, Michael Phayer, The Catholic Church and the Holocaust, 1930–1965 (Bloomington, 2000); David Cymet, History vs Apologetics: The Holocaust, The Third Reich and The Catholic Church (Lanham, 2010).

42 Daniel Jonah Goldhagen, A Moral Reckoning: The Role of the Catholic Church in the Holocaust and its Unfulfilled Duty of Repair (London, 2003), p. 311.

43 Griech-Polelle, Galen, p. 169.

darkness it abhors.’44 Although this revisionist scholarship has provided us with important insights into areas of church–state cooperation in Nazi Germany, its elite focus and often moralizing arguments have directed focus away from the social history of lived religious community and practice, especially during the war years.45 The revived interest in debates concerning Nazism’s status as a political religion during the 2000s further consolidated this tendency.46

By contrast, this study forms part of contemporary attempts to incorporate religion into the wider social and cultural histories of German society between 1939 and 1945, exploring Catholicism’s roles in shaping its adherents’ responses to, and understandings of, the Second World War. In so doing, it derives conceptual inspiration from two important recent studies of wartime German society. In a groundbreaking chapter of his social and cultural history of the air war, Death from the Skies, Dietmar Süß outlines the influential roles played by the Catholic and Protestant Churches on the German home front in the face of Allied bombing, such as the provision of pastoral care to laypeople and the burial of air raid victims.47 Nicholas Stargardt’s illuminating work on German society between 1939 and 1945, The German War, also affords considerable room to examination of Germans’ religious beliefs and practices, demonstrating their influential role in shaping many individuals’ perceptions of the conflict.48 Both these studies highlight that religious mentality and practice belong at the centre of work on wartime German society—not a distinct sub-field at its historiographical margins. By providing a dedicated regional investigation of Catholic belief, community, and practice in the Rhineland and Westphalia, I build upon these important insights and provide a comprehensive account of how religiosity in its personal and communal forms shaped lay and clerical responses to the Second World War, in addition to the conflict’s own impact on popular piety and devotion. This study argues that Catholics’ attitudes towards the unfolding persecution and murder of the Jews are best comprehended in these contexts, with Stargardt’s research demonstrating that Germans’ responses to

44 Richard Steigmann-Gall, The Holy Reich: Nazi Conceptions of Christianity, 1919–1945 (Cambridge, 2003), p. 267.

45 For a helpful volume embodying this focus on theological anti-Semitism, see Kevin Spicer (ed.), Antisemitism, Christian Ambivalence, and the Holocaust (Bloomington: Indiana, 2007), especially pp. XIII–XXI.

46 See Michael Burleigh, The Third Reich: A New History (New York, 2000), pp. 263–7; Beth A. Griech-Polelle, ‘Der Nationalsozialismus und das Konzept der “politischen Religion” ’, in Gailus and Nolzen (eds), Zerstrittene ‘Volksgemeinschaft’, pp. 204–26.

47 Süß, Death from the Skies, pp. 239–99.

48 Stargardt, German War; Stargardt, ‘The Troubled Patriot’.

the Holocaust between 1939 and 1945 were primarily informed by their own experiences of the war itself.49

The regional (and confession-specific) approach I have adopted confers a range of analytical advantages. Most importantly, it provides a manageable scale for in-depth research concerning the social and cultural histories of wartime religious belief and practice at the local level, in addition to the complex relationships between the higher and lower clergy and the laity. Recent studies of religion during the war years have, moreover, largely focused on the Wehrmacht’s military chaplaincies, rather than the home front, whose religious histories remain largely unwritten.50 It was nevertheless the latter which stood at the centre of German society’s religious practices and engagement during the Second World War. As the recent research concerning the Wehrmacht chaplaincies itself clearly demonstrates, Nazi anti-clerical policies severely restricted the religious provision available to devout soldiers serving in the armed forces, with many going extended periods without the opportunity to participate in either Catholic or Protestant services.51 As Albert Neuhaus, a conscripted Westphalian Catholic, wrote to his wife Agnes, in Münster, in July 1940:

You ask, whether I can go to church on Sundays. I can only tell you that we were led to church on the first Sunday here, but since then not at all. Here, religion is a minor consideration, or a matter which perhaps does not fit into the agenda at all. For that reason, you’ll have to say the Lord’s Prayer for me a few times.52

This is not, of course, to deny the presence of religious belief within the Wehrmacht; but it does indicate that German society’s devotional practices and confessional communities were most in evidence on the home front.53 Parishes in the Aachen Diocese held dedicated ‘Soldier’s Masses’ during the war years, with male congregation members serving in the Wehrmacht often expressing their thanks ‘for the eucharistic sacrifice and prayer in the Heimat’.54 Taking the home front as the study’s core geographic focus also permits exploration of religiosity among wider sections of the German population than those serving in the armed forces; the old

49 Stargardt, German War, p. 6.

50 Row, Militärseelsorge unter dem Hakenkreuz; Rossi, War of Annihilation. Important existing publications on the home front include, Dietmar Süß, Death from the Skies, pp. 239–99; Süß, ‘Glaube und Religiosität an der “Heimatfront”: Seelsorge und Luftkrieg 1939–1945’, in Gailus and Nolzen (eds), Zerstrittene ‘Volksgemeinschaft’, pp. 227–56.

51 Row, Militärseelsorge unter dem Hakenkreuz, pp. 83–5, 123, 279–85.

52 Redemann (ed.), Zwischen Front und Heimat, p. 37, letter of 10 July 1940.

53 For personal piety within the Wehrmacht, Nicholas Stargardt, Witnesses of War: Children’s Lives under the Nazis (London, 2005), pp. 141–60.

54 BAA, GVD Gemünd 1, II, 18248, pp. 102–3, report of 15 January 1943.

as well as young, and, perhaps most significantly, women in addition to men.55 Exploring the Second World War’s impact on Catholics’ patterns of devotion and observance moreover promises to enrich historiographical debates concerning religious change in twentieth-century Germany, which overwhelmingly focus on the decades following 1945.56

My selection of the Rhineland and Westphalia, and most specifically, the Archbishopric of Cologne and the Bishoprics of Aachen and Münster, is also not arbitrary. These regions represented heartlands of German Catholicism, with Cologne nicknamed the ‘German Rome’ and its archbishopric featuring the largest Catholic population of any in the Reich.57 During the Weimar Republic, electoral patterns in Cologne reflected this strong Catholic influence, with the Centre Party gaining a consistently large popular vote. Even in the face of Nazi intimidation during the 5 March 1933 election campaign, it received 35.9 per cent of the vote in the Cologne-Aachen district.58 Bishop Galen bore the same family name as one of Münster’s early modern prince-bishops, underlining the resilient strength of aristocratic Catholic conservatism in northern Westphalia.59 Pairing the Rhineland and Westphalia within a single regional study also replicates contemporary perceptions: agencies as diverse as the SD and socialist underground (SOPADE) did likewise in their ‘mood reports’ during the Nazi era.60 Certain Catholic contemporaries, such as the Cologne native Heinrich Böll, could joke that Westphalians were somewhat dour in comparison to Rhinelanders, but in reality the groups had much in common.61

The Rhineland and Westphalia furthermore provide a particularly illuminating viewpoint on the war’s impact on Catholic life in Germany

55 For the gendering of religious faith and practice during the First World War, Houlihan, Catholicism and the Great War, pp. 153–85.

56 See, Großbolting, Der verlorene Himmel; Benjamin Ziemann, Encounters with Modernity: The Catholic Church in West Germany, 1945–1975 (New York, 2014); Wilhelm Damberg, Abschied vom Milieu?: Katholizismus im Bistum Münster und in den Niederlanden, 1945–1980 (Paderborn, 1997). Ziemann, ‘Zur Entwicklung christlicher Religiosität’, pp. 113–14, underlines the neglect of the years before 1945.

57 AEK, K.A.1944, (Z 80 84), p. 23, article of 10 January 1944; Mertens, Himmlers Klostersturm, p. 195.

58 Mertens, Himmlers Klostersturm, p. 192. 59 Griech-Polelle, Galen, p. 9.

60 E.g. Deutschland-Berichte der Sozialdemokratischen Partei Deutschlands, (Sopade), Vol. 7, (1940), (Frankfurt am Main, 1980), p. 94, report of 6 February 1940, Heinz Boberach (ed.), Meldungen aus dem Reich: Die geheimen Lagenerichte des Sicherheitsdienstes der SS 1938–1945 (Berlin, 1984), Vol. 15, p. 5886, report of 18 October 1943.

61 Heinrich Böll, Briefe aus dem Krieg 1939–1945, Vol. I (Munich, 2003 ed.), p. 105, 25 August 1940. Local histories include Elmar Gasten, Aachen in der Zeit der nationalsozialistischen Herrschaft 1933–1944 (Frankfurt am Main, 1993); Horst Mazerath, Köln in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus, 1933–1945 (Cologne, 2009); Jost Dülffer and Margit Szöllösi-Janze (eds), Schlagschatten auf das ‘braune Köln’: die NS-Zeit und danach (Cologne, 2010).

between 1939 and 1945.62 The local presence of the Ruhr industrial belt, as well as large cities such as Cologne and Düsseldorf, ensured that the Rhineland and Westphalia were both heavily bombed by the western Allies. Cologne suffered heavier bombardment than any German city other than Berlin itself, with the Rhineland metropolis targeted by 262 air raids during the war, and 78 per cent destroyed by its end.63 These regions are accordingly perfectly suited to examination of Catholics’ responses to bombing, as well as its practical consequences for parish life on the ground. The Allies’ staggered conquest of the Rhineland and Westphalia, beginning with that of Aachen as early as October 1944, and continuing into March and April 1945, facilitates analysis of popular opinion in these regions during the final phases of Nazi control. In focusing on the Rhineland and Westphalia, this study considers German regions unusual for the length of time they constituted a combat zone between 1939 and 1945. As Archbishop Frings of Cologne’s pastoral letter of 27 May 1945 evocatively stated, ‘our Catholic Rhineland has, as a borderland, been forced to bear the full force of the war’.64

Exploring the wartime outlook of this region’s Catholic population also casts new light on the emergence of Christian Democracy in West Germany after 1945. As Maria Mitchell insightfully notes, the Rhenish CDU represented ‘the polestar of German Christian Democracy’, and ‘exuded influence far beyond the Rhineland’.65 Many of this book’s dramatis personae—especially Archbishop Frings and the Cologne clergyman Robert Grosche (1888–1967)—were personal friends of Konrad Adenauer, who, after all, had been the city’s mayor during the Weimar era.66 The urban iconography of wartime Cologne moreover featured prominently within early Christian Democratic portrayals of German (and Catholic) victimhood over the years following 1945. The image of the city’s Cathedral towering victoriously over a moonscape—interpreted by many clergymen as reflecting Catholicism’s victory over the decadence of secular modernity—quite

62 For a wonderful overview of the war’s impact on local life, Martin Rüther, Köln im Zweiten Weltkrieg: Alltag und Erfahrungen zwischen 1939 und 1945 (Cologne, 2005).

63 Beate Eickhoff, St Agnes: Ein Viertel und seine Kirche (Cologne, 2001), p. 82; Ulrich Krings and Otmar Schwab (eds), Köln: Die Romanischen Kirchen: Zerstörung und Wiederherstellung (Cologne, 2007), p. 12; Richard Overy, The Bombing War: Europe, 1939–1945 (London, 2013), p. 472.

64 Wilhelm Corsten (ed.), Kölner Aktenstücke zur Lage der katholischen Kirche in Deutschland 1933–1945 (Cologne, 1949), p. 314, 27 May 1945.

65 Maria D. Mitchell, The Origins of Christian Democracy: Politics and Confession in Modern Germany (Ann Arbor, 2012), p. 39.

66 See Paul Betts, ‘When Cold Warriors Die: The State Funerals of Konrad Adenauer and Walter Ulbricht’, in Confino, Betts, and Schumann (eds), Mass Death and Individual Loss, pp. 156–7; Robert Grosche, Kölner Tagebuch 1944–46 (Cologne, 1992 ed.), pp. 48–51, entries for 23 and 30 October 1944, p. 127, entry for 20 March 1945.

literally loomed large in this context.67 In August 1948, at celebrations commemorating the 700th anniversary of the beginning of the cathedral’s construction, many speeches dwelt upon its ‘manifestation of westernChristian thought’. With Catholic representatives from the Netherlands, Belgium, France, Switzerland, Great Britain, Australia, and the United States in attendance, this ceremony served to symbolically re-integrate the Rhineland into the ‘West’.68 The continuities of geography and personnel between the regions central to this study during the Second World War, and those which would subsequently prove pivotal to the development of Christian Democracy in West Germany, ensure that my findings cast new light on the so-called ‘hour of the Church’ after 1945.

This study gathers a wide range of source material produced by various contemporary actors. It uses documents held in church archives in the Rhineland and Westphalia, such as pastoral letters, sermons, and internal administrative reports to gain insight into the clergy’s attitudes and activities during the war years.69 These reveal senior clergymen’s theological perspectives on the conflict, and provide a wealth of information concerning religious life at a local level, such as through visitation reports and clerical discussions of popular opinion. Archival collections concerning individual clergymen, such as Robert Grosche in Cologne, provide diaries and letters facilitating exploration of their private thoughts and aspects of emotional subjectivity.70 In a similar vein, the published diaries and letters of Rhenish and Westphalian Catholics, such as Heinrich Böll and the Neuhaus family, offer fascinating glimpses into the outlook and mentalities of laypeople.71 I augment these ecclesiastical and personal sources with archival and published documentation produced by various Nazi agencies, from Party and Gestapo officials at the local level to central SD reports. This ensures that my analysis is not solely reliant on materials produced by either state or church officials, and can compare their observations concerning popular attitudes and morale.

I also employ the extensive reports produced by clergymen in the employment of the Gestapo in the Rhineland, which provide detailed information concerning their opinions, mood, and discussions at private meetings.72 These sources permit investigation of clerical morale and

67 Benjamin Städter, Verwandelte Blicke: Eine Visual History von Kirche und Religion in der Bundesrepublik 1945–1980 (Frankfurt am Main, 2011), pp. 38–51.

68 Markus Schmitz and Bernd Haunfelder (eds), Humanität und Diplomatie: Die Schweiz in Köln 1940–1949 (Münster, 2001), p. 290; Patrick Thaddeus Jackson, Civilizing the Enemy: German Reconstruction and the Invention of the West (Ann Arbor, MI, 2006), p. 186.

69 See the AEK, BAA, BAM collections—see abbreviations.

70 AEK, Nachlaß Grosche, 134,135, 284, 285, 311, 469

71 Böll, Briefe aus dem Krieg, Vols I and II; Redemann (ed.), Zwischen Front und Heimat.

72 LNRW. ARH, RW 34, 01, 02, 03, 08, RW 35, 08, 09.