FundamentalsofBrain NetworkAnalysis

AlexFornito MonashUniversity,Australia

AndrewZalesky

TheUniversityofMelbourne,Australia

EdwardTBullmore

UniversityofCambridge,UnitedKingdom

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier

125LondonWall,London,EC2Y5AS,UK

525BStreet,Suite1800,SanDiego,CA92101-4495,USA

50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,USA

TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UK

Copyright © 2016ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic ormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem, withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformation aboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchasthe CopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher (otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroaden ourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluating andusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuch informationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,including partiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assume anyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability, negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideas containedinthematerialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN:978-0-12-407908-3

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublications visitourwebsiteat www.elsevier.com

PrintedinUSA

AuthorBiographies

AlexFornito

AlexFornitocompletedaPhDintheDepartmentsofPsychologyandPsychiatryattheUniversityofMelbourne,Australia,followedbyPost-Doctoral trainingattheUniversityofCambridge,UK.Heisanassociateprofessor,AustralianResearchCouncilFutureFellow,andDeputyDirectoroftheBrainand MentalHealthLaboratoryintheMonashInstituteofCognitiveandClinical Neurosciences,Australia.Alex’sresearchusescognitiveneuroscience,network science,andgraphtheorytounderstandbrainnetworkorganizationinhealth anddisease.Hehaspublishedover100scientificarticles,muchofwhichare focusedonthedevelopmentandapplicationofnewmethodstounderstand howbrainnetworksdynamicallyadapttochangingtaskdemands,howthey aredisruptedbydisease,andhowtheyareshapedbygeneticinfluences.

AndrewZalesky

AndrewZaleskycompletedhisPhDintheDepartmentofElectricalandElectronicEngineeringattheUniversityofMelbourne,Australia.Heworkswith neuroscientists,utilizinghisengineeringexpertiseinnetworkstounderstand humanbrainorganizationinhealthanddisease.Hehasdevelopedwidelyused methodsformodelingandperformingstatisticalinferenceonbrainimaging data.Hismethodsareutilizedtoinvestigatebrainconnectivityabnormalities indisease.Heidentifiedsomeofthefirstevidenceofconnectomepathology inschizophrenia.AndrewcurrentlyholdsafellowshipfromtheNational HealthandMedicalResearchCouncilofAustralia.HeisbasedattheUniversity ofMelbourneandholdsajointappointmentbetweentheMelbourne NeuropsychiatryCentreandtheMelbourneSchoolofEngineering.Heleads theSystemsNeuropsychiatryGroup.

EdwardBullmore

EdBullmoretrainedinmedicineattheUniversityofOxfordandStBartholomew’sHospital,London,andtheninpsychiatryattheBethlemRoyaland MaudsleyHospital,London.In1993,hewasaWellcomeTrust(Advanced) ResearchFellowattheInstituteofPsychiatry,King’sCollegeLondon,where hecompletedaPhDinthestatisticalanalysisofMRIdata,beforemovingto CambridgeasProfessorofPsychiatryin1999.Currently,heisco-ChairofCambridgeNeuroscience,ScientificDirectoroftheWolfsonBrainImagingCentre, andHeadoftheDepartmentofPsychiatryintheUniversityofCambridge.Heis alsoanhonoraryConsultantPsychiatrist,andDirectorofR&DinCambridgeshireandPeterboroughFoundationNHSTrust.Since2005,hehasworked half-timeforGlaxoSmithKline,currentlyfocusingonimmuno-psychiatry. HehasbeenelectedasaFellowoftheRoyalCollegeofPhysicians,theRoyal CollegeofPsychiatrists,andtheAcademyofMedicalSciences.Hehaspublishedabout500scientificpapers,andhisworkhasbeenhighlycited.He hasplayedaninternationally-leadingroleinunderstandingbrainconnectivity andnetworksbygraphtheoreticalanalysisofneuroimagingandotherneuroscientificdatasets.

Foreword

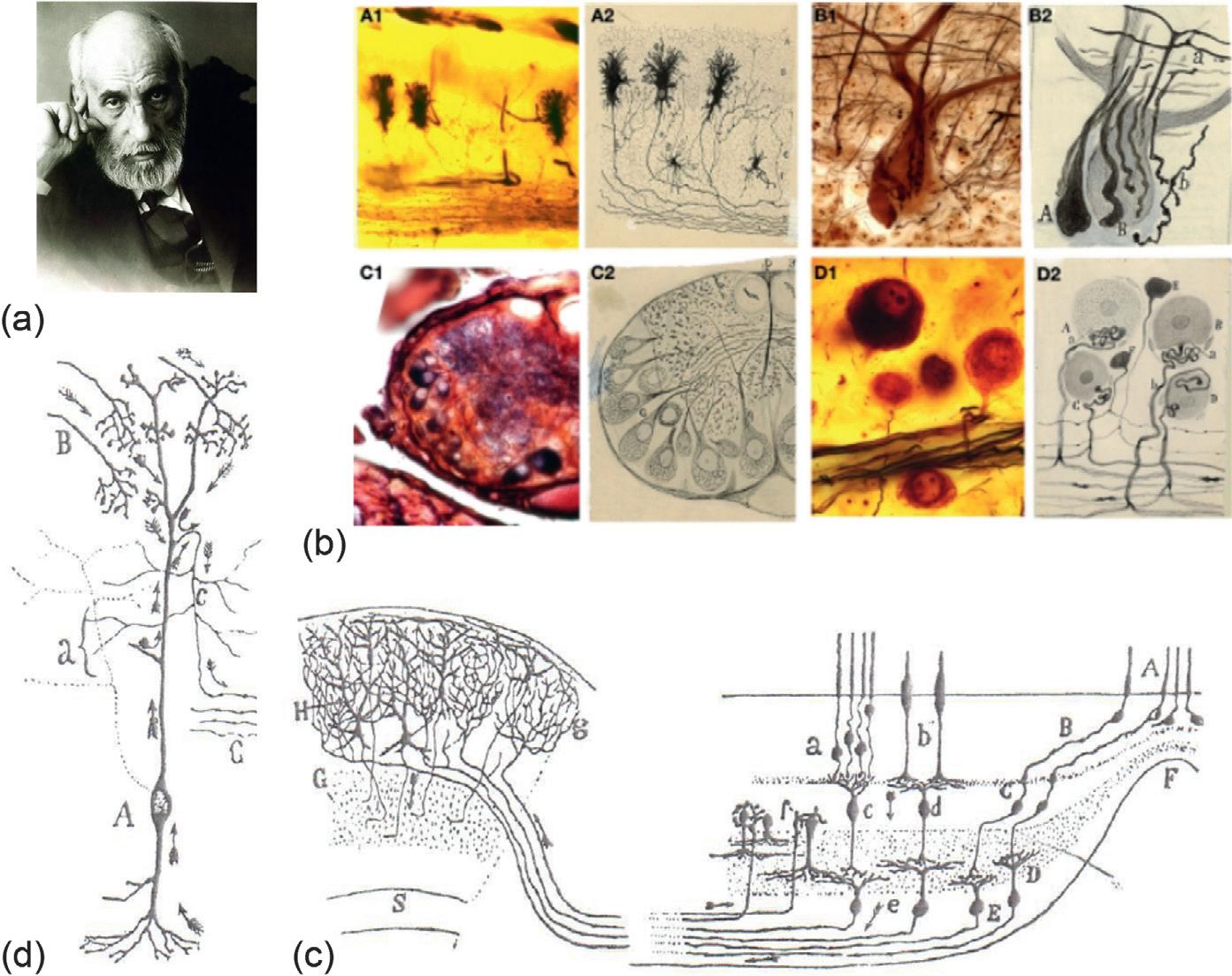

Foroveracentury,thenotionthatindividualnervecellsorneuronsarethe basicstructuralandfunctionalunitsofthenervoussystemhasbeenthebedrockofneuroscience.Probablythemostinfluentialcontributioncamefrom theworkofRamo ´ nyCajalonbrainanatomyandhistology,whichrevealed astaggeringdiversityofneuronalcelltypesandmorphologiesarrangedinto intricatecircuitry.Withastoundingintuition,andprecedingthediscoveryof thebasicphysiologicalmechanismsofneuronalcommunication,Ramo ´ ny Cajalnotonlysketchedtheanatomicalarrangementofthecellularelements ofneuronalcircuits,healsodevisedfunctional“wiringdiagrams”thatspecified thedirectionandflowofneuralsignals.Ramo ´ nyCajalisnowrecognizedasa majorarchitectofthe“neurondoctrine,”whichcontinuestobefoundational forallofmodernneuroscience.

Averydifferentalternativeframeworkwasthereticulartheory,whosemain proponentwasCajal’santagonistCamilloGolgi.Thetheorywasbasedon analternativemodelofhowneuronswereanatomicallyandfunctionally related—insteadofformingdiscreteelements,Golgi’sviewwasthatneurons formedacontinuum,bybeingphysicallyconjoinedintoasingle“network” (orreticulum).Evenastheevidencesupportingtheneurondoctrineaccumulated,Golgiperseveredinthisview,ashecouldnotfathomhowdiscreteelementscouldsupportintegrativefunction.Ashestatedinhis1906Nobel lecture,“Howeveropposeditmayseemtothepopulartendencytoindividualizetheelements,Icannotabandontheideaofaunitaryactionofthenervous system.”

Aswenowknow,Golgi’sconceptionofneuronsasformingacontinuoussyncytiumwaswrong.Andyet,inpointingtothegapbetweentheorganizationof thebrainintoindividualnervecellsononesideanditsintegrativeactivityon theother,Golgiarticulatedafundamentalproblemthathasanimatedtheoreticalneuroscienceeversince.Inasense,Golgi’sreticulartheorywasanearly antecedentofmodelsthatattemptedtoaccountforneuralintegrationand computation,asexemplifiedinthespeculativeideasofearlyconnectionists

andlaterinmathematicaltheoriesofneuralnetworks.Whilenetworks,oftenin theguiseof“neuralcircuits,”havebeenalong-standingintellectualcurrentin theoreticalneuroscience,untilfairlyrecentlyitwasquitedifficult,ifnotimpossible,todirectlyobserveandmeasuretheanatomicalandfunctionalnetworks ofthebrain.Thenecessarysophisticatedtoolsformappingextendedanatomicalnetworksandforrecordingfunctionalbrainactivityacrosslargeneuronal populations,oreventhewholebrain,wereslowtoemerge.

Allthishaschangedinrecentyears.Newtechnologiesformappingandrecordinglarge-scaleneuronalsystemshavefinallyarrived,creatinganabundanceof dataontheanatomicallayoutandfunctionaldynamicsofneuralsystems.Asa result,neuroscienceisrapidlytransitioningintoaneraof“bigdata.”Thistransitioncreatesanumberofnewopportunities.Forexample,thedevelopmentof newmethodsformappinganatomicalconnectionsinentirenervoussystems nowallowstheconstructionofcomprehensivestructuralnetworksorconnectomes,acrossspeciesandindividuals.Inparallel,thedevelopmentofabroad rangeofneurophysiological,optical,andmagneticresonanceimagingtechniquesnowenablescontinuousrecordingofthedynamicsofneuralactivity acrosshundredsofneurons,orindeedthewholebrain.Howcanwemake senseoftheserichandcomprehensiveanatomicalandphysiologicaldatasets? Howcanweextractprinciplesofhowbrainsarestructurallyanddynamically organized?

Thesearethechallengesthatthisvolumeattemptstoaddress.Itsfocusisonthe applicationofthetoolsandmethodsofnetworkscience,whichhasalready provenextraordinarilyfruitfulandhasgatheredsignificantmomentumover thepastdecade.Thisvolumeisthefirsttoofferacomprehensiveoverview ofnetworkmodelingandanalysistechniquestobraindata,bothstructural andfunctional.Thebookfillsthegrowingneedforasystematicanddidactic treatmentofthemajortypesofnetworkmeasuresandmodelsthatarerelevant toneuroscienceresearch.

Thebook’sbasicplangoesfromabriefintroductionofmajorconceptsand termstoamorein-depthconsiderationofmeasuresthatcapturenodalstatistics (degreeandstrength),tootherwaysofexpressingcentralityandinfluenceina network(centrality),andcharacterizingimportantnetworkelements(hubs). Then,thebookturnstoadiscussionofhownetworkelementscooperateasnetworkcoresorrichclubs,beforeintroducingmodelsthatcharacterizetheefficiencywithwhichneuralinformationiscommunicatedinbrainnetworks, accordingtodifferentmodelsbasedonshortestpathrouting,diffusion,and greedynavigation.Itthenexamineshownodesandedgesformstereotypicprocessingunits(motifs),andhownetworkorganizationisshapedbyprinciples relatedtotheconservationoftime,space,andmaterial;principlesthatwere firstdescribedbyRamo ´ nyCajaloveracenturyago.Amajoravenuein

contemporarynetworkanalysisisthedecompositionoflargenetworksinto smallercommunitiesormodules,usuallyonthebasisoftheirdenseinternal connectivity.Here,thebookgoesintoconsiderabledepthbyprovidingan overviewofsomeoftheclassicaswellastheverylatestapproachesforidentifyingnetworkmodules.Finally,importantchaptersaddressissuesrelatedto nullmodels(anemergingmethodologicalfocusinnetworkscience)and methodsforcomparingandclassifyingnetworks.Thelatterwillbeparticularly appreciatedbyreadersinterestedinapplyingnetworkapproachestocharacterizingdifferencesinnetworkorganizationassociatedwithdevelopmental changesorclinicalconditions.

Thebookdoesmuchmorethansurveythemethodologicalunderpinningsof theburgeoningfieldofconnectomics.Importantly,itmanagestotranslatethe oftenhighlytechnicaljargonofnetworksintolanguagethatconnectswiththe practiceandterminologyofempiricalneuroscience.Whilecomprehensivein itstreatmentofeachspecifictopic,thematerialispresentedinastylethat makesnetworkmethodsaccessibletotheaverageneuroscientistwhoisinterestedintappingintotheenormouspotentialofnetworkscienceforunlocking principlesofbrainorganization.Thebooknotonlymakesnetworkscience approachable,itaddressesthemanydomain-specificissuesthatsurroundbrain networkssuchastheconstructionofnetworksfromappropriatelychosen nodalpartitionsandedgemeasures,ortheconstructionofnullmodelsthat arebothrigorousandbiologicallyplausible.Thesediscussionsaregenerally missingfromothermoreabstractaccountsofcomplexnetworks,andyetthey arecriticallyimportantforgeneratingandanalyzingneurobiologicallymeaningfulnetworkmodels.Thisfocusonnetworkneurosciencewillbeespecially appreciatedbystudentswhoareeagertolearnthebasicsofthisrapidlyevolving newfield.

Asneurosciencedatacontinuetogrowinvolumeandcomplexity,thisbook fillsanimportantgapbyprovidingasetoftheoreticallygroundedtoolsthat canaddressatleastsomeofthebigdatachallengesfacingthedisciplinetoday. Iamcertainthatthismuch-neededprimeronbrainnetworkswillbecomean indispensableadditiontothebookshelvesofallneuroscientistsinterestedin theorganizationandfunctionofnervoussystems,fromcellulartosystems scales.

OlafSporns,PhD

DistinguishedProfessor,RobertH.ShafferChair IndianaUniversity

AnIntroductiontoBrainNetworks

Itisoftensaidthatthebrainisthemostcomplexnetworkknowntoman.A humanbraincomprisesabout100billion(1011)neuronsconnectedbyabout 100trillion(1014)synapses,whichareanatomicallyorganizedovermultiple scalesofspaceandfunctionallyinteractiveovermultiplescalesoftime.This vastsystemisthebiologicalhardwarefromwhichallourthoughts,feelings, andbehavioremerge.Clinicaldisordersofhumanbrainnetworks,likedementiaandschizophrenia,areamongthemostdisablingandtherapeuticallyintractableglobalhealthproblems.Itisthereforeunsurprisingthatunderstanding brainnetworkconnectivityhaslongbeenacentralgoalofneuroscience,and hasrecentlycatalyzedanunprecedentederaoflarge-scaleinitiativesandcollaborativeprojectstomapbrainnetworksmorecomprehensivelyandingreater detailthaneverbefore(Bohlandetal.,2009;Kandeletal.,2013;VanEssen andUgurbil,2012).Aswewillsee,oneoftheimplicationsofmodernbrain networkscienceisthatthehumanbrainmaynot,infact,beauniquelycomplexsystem.However,itiscertainlytimely,challengingandimportantto understanditsorganizationmoreclearly.

Centraltocurrentthinkingaboutbrainnetworksistheconceptofthe connectome.Thiswordwasfirstcoinedin2005byOlafSporns,GiulioTononi,and RolfK € otter (2005) andindependentlyinaPhDdissertationby PatricHagmann (2005) todefinea matrix representingallpossiblepairwiseanatomicalconnectionsbetweenneuralelementsofthebrain(Figure1.1).Thetermconnectome, inthefirstandstrictestsenseoftheword,thusstandsforanidealorcanonical stateofknowledgeaboutthecellularwiringdiagramofabrain.Thetrulyexponentialgrowthofresearchinthisareainthelast10yearshasledtoinvestigationsofamoregeneralconceptoftheconnectomethatincludesthematrixof anatomicalconnectionsbetweenlarge-scalebrainareasaswellasbetweenindividualneurons;andthematrixoffunctionalinteractionsthatisrevealedbythe analysisofphysiologicalprocessesunfoldingasslowlyasthefluctuationsof cerebralbloodoxygenationmeasuredwith functionalmagneticresonance imaging (MRI;spanningfrequenciesbelow0.1Hz),orasfastasthehighfrequencyneuronaloscillationsdetectablewithinvasiveandnoninvasiveelectrophysiology(over500Hz;seealso Chapter2).Aconsistentconceptualfocus onquantifying,visualizing,andunderstandingbrainnetworkorganization

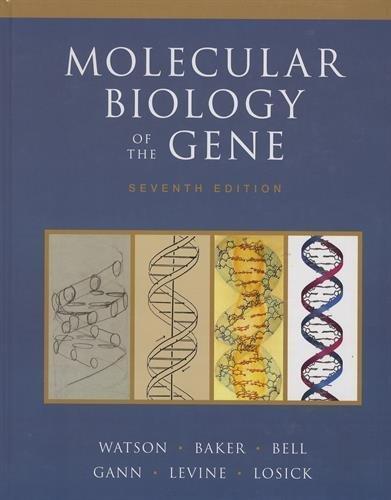

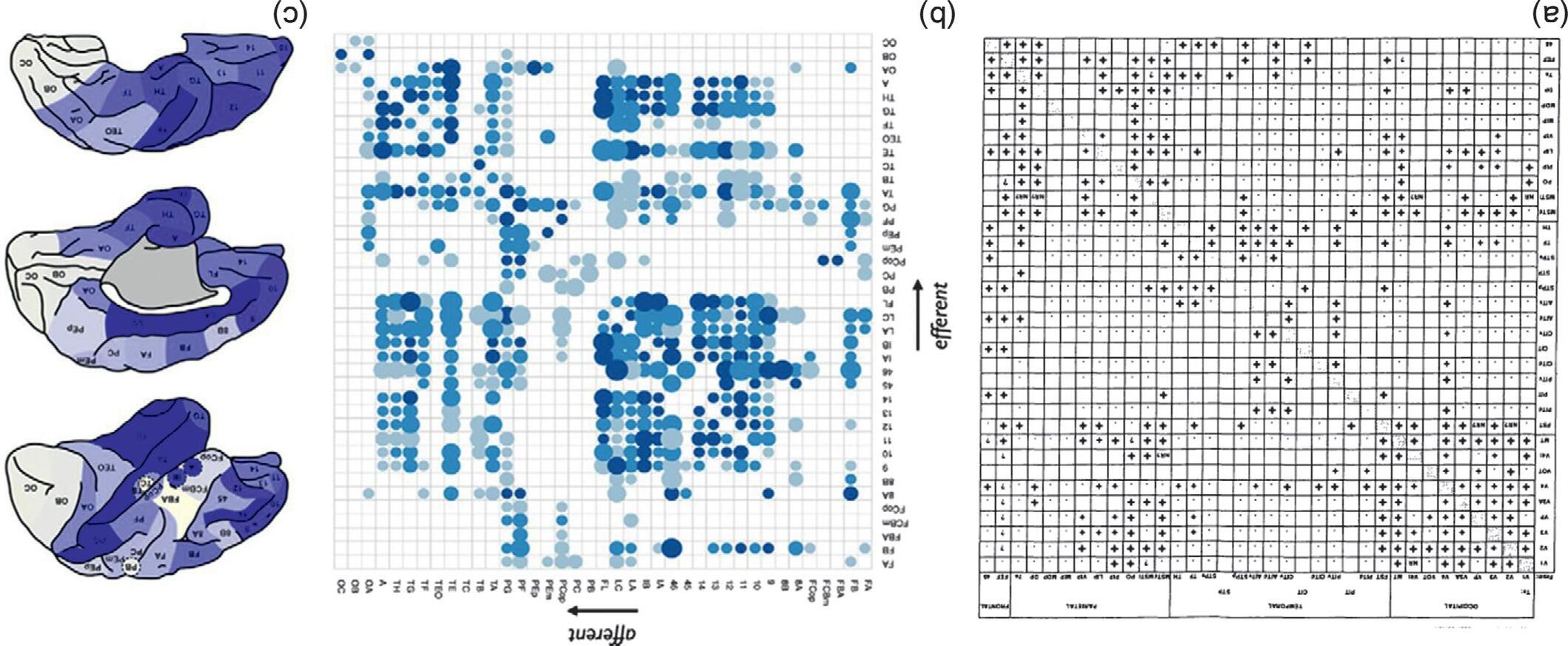

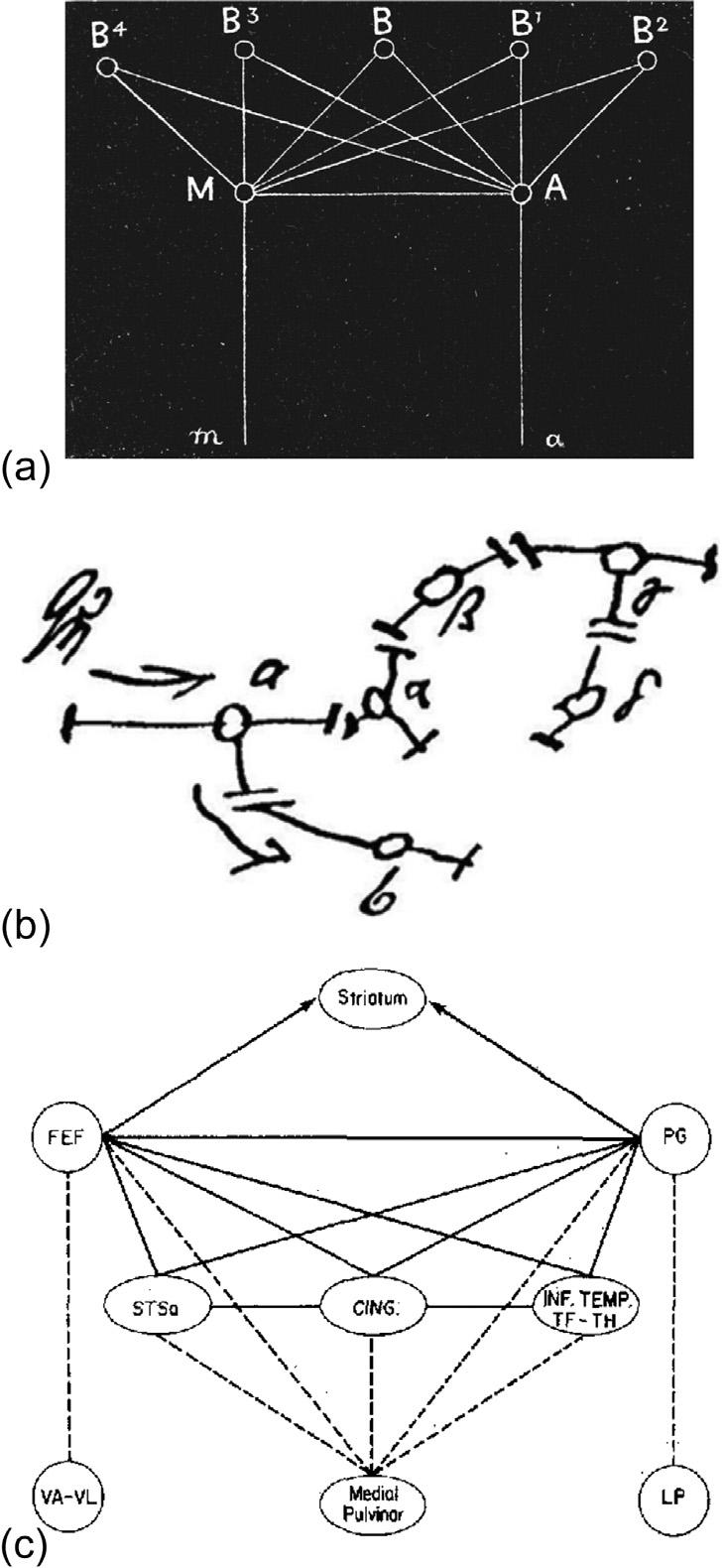

FIGURE1.1 Theconnectomeasamatrix. (a) Oneofthefirsteffortstosystematicallygenerateaconnectivitymatrixforthebrain(FellemanandVanEssen,1991). Thismatrixrepresentstheconnectivityof32neocorticalareasinvolvedinvisualfunctioninthemacaquemonkey,constructedbycollatingtheresultsofalargenumberof published tract-tracing studiesinthisanimal.Inthismatrix,ablackcrossindicatesanoutgoingprojectionfromtheregionlistedintherowtotheregionlistedin thecolumn. (b) Anupdatedconnectivitymatrixofthemacaquecomprising39corticalareas,asreconstructedfromanonlinedatabaseoftract-tracingstudies. Thismatrixisorganizedsuchthatcoloredelementsrepresentaprojectionfromtheregionlistedinthecolumntotheregionlistedintherow(see Chapter3).Thesizeof thedotsineachmatrixelementisproportionaltotheprojectiondistanceanddarkercolorsindicatestrongeraveragereportedconnectivitystrength. (c) Theanatomical locationsoftheareaslistedinthematrixin (b).Darkercolorsidentifyregionswithhighertotalconnectivitytotherestofthenetwork. (a) Reproducedfrom Fellemanand VanEssen(1991) and (b,c) from Scholtensetal.(2014) withpermission.

acrossmultiplescalesofspaceandtimeisafundamentalcharacteristicofthe burgeoningfieldof connectomics (BullmoreandSporns,2009).

Therelativelyrecentbirthofconnectomicsshouldnotbeinterpretedasevidenceofapriorlackofneuroscientificinterestinbrainnetworks.Infact,many nineteenthandtwentiethcenturyneuroscientists—likeRamo ´ nyCajal,Golgi, Meynert,Wernicke,Flechsig,andBrodmann—werewellawareoftheimportanceofconnectivityandnetworksinunderstandingnervoussystems.These andotherfoundationalneuroscientistsmadeseminaldiscoveriesandwrote downenduringconceptualinsightsthathavesinceunderpinnedthewaythat wethinkaboutnervoussystems.

So,what’snew?Whydoweneednewwordstolabelaneuroscientificprogram thatisarguablyasoldasneuroscienceitself?Whynowfortheconnectomeand connectomics?Isitjustapassingfad,afashionableblipinprofessionaljargon? Oraretheremorefundamentalfactorsthatcanexplainwhytheconnectome hasexplodedasadistinctivefocusforneuroscienceinthetwenty-firstcentury?

Inourview,therearetwoconvergentfactorsdrivingthescientificascendancyof connectomics.First,recentyearshavewitnessedrapidgrowthinthescienceof networksingeneral.Sincethe1980stherehavebeenmajorconceptualdevelopmentsinthestatisticalphysicsofcomplexnetworksandever-widerapplications ofnetworksciencetotheanalysisandmodelingofbigdata.Newwayshavebeen foundofquantifyingthetopologicalcomplexityoflargesystemsofinteracting agents,andstrikingcommonalitieshavebeenobservedintheorganizational propertiesofabroadarrayofreal-lifenetworks,including,butnotlimitedto, airtransportationnetworks,microchipcircuits,theinternet,andbrains.

Thesecondfactordrivingthegrowthofconnectomicsisthetechnologicalevolutionofmethodstomeasureandvisualizebrainorganization,acrossmultiple scalesofresolution.Sincethe1990stherehasbeensignificantprogressin humanneuroimagingscience,especiallyusingMRItomapwholebrainanatomicalandfunctionalnetworksatmacroscopicscale( 1-10mm3,orderof 10 2 m)inhealthyvolunteersandpatientswithneurologicalandpsychiatric disorders(BullmoreandSporns,2009;Fornitoetal.,2015).Inthelast10years, therehavealsobeenspectacularmethodologicaldevelopmentsin tracttracing, opticalmicroscopy,optogenetics,multielectroderecording,histological geneexpression,andmanyotherneurosciencetechniquesthatcannowbe usedtomapbrainsystemsatmesoscopic( 10 4 m)andmicroscopicscales ( 10 6 m),undermorecontrolledexperimentalconditions,andinawider rangeofspecies(Kennedyetal.,2013;Ohetal.,2014;Chungand Deisseroth,2013;Fennoetal.,2011).

Theconvergenceofthesetwopowerfultrends—(1)themathematicalandconceptualdevelopmentsincomplexnetworkscience;and(2)theevolutionof

technologiesformeasuringnervoussystems—isthecruxofwhatmotivatesand isdistinctivelycharacteristicofthenewfieldofconnectomics.Thisbookis abouthowwecanapplythescienceofcomplexnetworkstounderstandbrain connectivity.Inparticular,wefocusontheuseof graphtheory tomodel,estimateandsimulatethe topology anddynamicsofbrainnetworks.Graphtheory isabranchofmathematicsconcernedwithunderstandingsystemsofinteractingelements.Agraphisusedtomodelsuchsystemssimplyasasetof nodes linkedby edges.Thisrepresentationisremarkablyflexibleand,despiteitsformalsimplicity,canbeusedtoinvestigatemanyaspectsofbrainorganizationin diversekindsofdata.

Inthisintroductorychapter,weprovideamotivationforwhygraphtheoryis usefulforunderstandingbrainnetworks,andofferabriefhistoricaloverviewof howbraingraphshavebecomeakeytoolinsystemsneuroscience.Thisbackgroundprovidescontextforthesubsequentchapters,whichconcentratein moretechnicaldetailonspecificaspectsofgraphtheoryandtheirapplication toconnectomicanalysisofneuroscientificdata.

1.1GRAPHSASMODELSFORCOMPLEXSYSTEMS

Complexsystemshavepropertiesthatareneithercompletelyrandomnor completelyregular,insteadshowingnontrivialcharacteristicsthatareindicativeofamoreelaborate,orcomplex,organization.Suchsystemsareallaround us,andrangefromsocieties,economies,andecosystems,toinfrastructuralsystems,informationprocessingnetworks,andmolecularinteractionsoccurring withinbiologicalorganisms(Baraba ´ si,2002).Theseareallbigsystems—often comprisingmillionsofagentsinteractingwitheachother—andtheyarerepresentedbyverydiversekindsofdata.Itisonlyinthelast20yearsorsothatithas becomemathematicallytractableandscientificallyinterestingtoquantifythis dauntingcomplexity.

Asmethodshavebeendevelopedtodealwithsuchdata,andasthesemethods havebeenappliedmorewidelyindifferentdomainsorfields,ithasbecome clearthatsuperficiallydifferentsystems—suchasfriendshipnetworks,metabolicinteractionpathways,andverylarge-scaleintegratedcomputercircuits—canexpressremarkablygeneralpropertiesintermsoftheirnetwork organization(AlbertandBaraba ´ si,2002;Newman,2003a).Fromthesedevelopments,aninterdisciplinaryfieldofnetworksciencehasformedaroundthe useofgeneralanalyticmethodstomodelcomplexnetworks,andtoexplorethe scopeofcommonornear-universalprinciplesofnetworkorganization,function,growth,andevolution.Principalamongthesegeneralmethodsisgraph theory.

1.1.1ABriefHistoryofGraphTheory

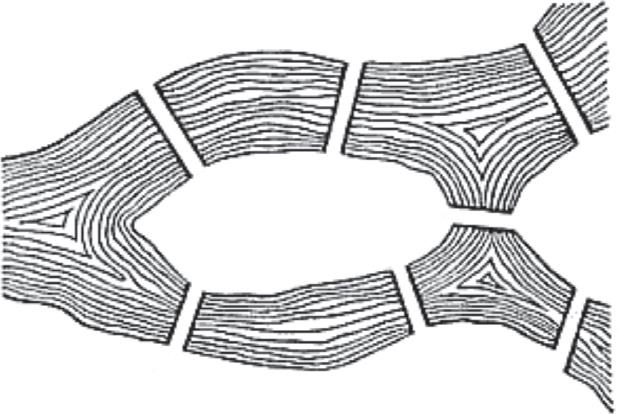

Thefirstuseofagraphtounderstandareal-worldsystemiswidelycreditedto theSwissmathematicianLeonhardEuler(1707-1783).In1735,Eulerlived inthePrussiantownofKonigsberg(nowtheRussiancityofKaliningrad), whichwasbuiltaroundsevenbridgesacrosstheriverPregel,linkingthetwo mainriverbanksandtwoislandsinthemiddleoftheriver(Figure1.2a).An unresolvedproblematthattimewaswhetheritwaspossibletowalkaround thetownviaaroutethatcrossedeachbridgeonceandonlyonce.Eulersolved thisproblembyrepresentingthefourlandmassesdividedbytheriverasnodes, andthesevenbridgesasinterconnectingedges(Figure1.2b).Fromthisprototypicalgraph,hewasabletoshowthatnomorethantwonodes(thestartand endpointsofthewalk)shouldhaveanoddnumberofedgesconnectingthem totherestofthegraphforsuchawalktobepossible.Infact,allfournodesin theKonigsberggraphhadanoddnumberofedges,meaningthatitwasimpossibletofindanyroutearoundthecitythatcrossedeachandeverybridgeonly once.Inthisway,Eulerprovedonceandforallthatthesystemofbridgesand islandsthatcomprisedthecitywasorganizedsuchthatthe“Konigsbergwalk” wastopologicallyprohibited.

FIGURE1.2 Theoriginsofgraphtheory:thefirsttopologicalanalysisbyEuler. (a) Simplified geographicmapofthePrussiantownofK€ onigsberg,whichcomprisedfourlandmasses(markedA–D) linkedbysevenbridges(markeda–f).ThespecificproblemthatEulersolvedwaswhetheritwaspossibleto finda path thatcrossedeachbridgeonceandonlyonce.Thegeographicalmaplavishesdetailonfeatures liketheshapeoftheislands,andthecurrentsintheriver,thatarecompletelyirrelevanttosolvingthis problem. (b) Graphicalrepresentationoftheproblem.Euler’stopologicalanalysissuccessfullysimplified thesystemasa binarygraph—withnodesforlandmassesandedgesforbridges—andfocusedon the degree,ornumberofedges,thatconnectedeachnodetothegraph. (a) Reproducedfrom Kraitchik (1942) withpermission.

TheimportanceofEuler’sanalysisis not inthedetailsofthegeographyofeighteenthcenturyKonigsberg;ratheritisimportantpreciselybecauseitsuccessfullyignoredsomanyofthosedetailsandfocusedattentiononwhatlater becameknownasthetopologyoftheproblem.Thetopologyofagraphdefines howthe links betweensystemelementsareorganized.Indeed,thisisexactly whatEuler’sgraphfocuseson;thenetworkofbridgesconnectingislands andriverbanks.ItisnotinformedbyanyotherphysicalaspectofK € onigsberg, suchasthephysicaldistance(length)ofthebridges,thedistancesbetween them,andsoon.Moregenerally,theresultsofthisandanyothertopological analysiswillbeinvariantunderanycontinuousspatialtransformationofthe system.Toseethis,imaginetakingthephysicalmapofKonigsbergdepicted in Figure1.2a andincreasingordecreasingitsphysicalscale,orrotatingit, orreflectingit,orstretchingit.Noneofthese(oranyother)continuousspatial transformationswillhaveanyeffectonthenumberofbridgesconnectingany particularislandtotherestofthetown.

Topologydevelopedstronglyasafieldofmathematicsfromthelatenineteenth century,precedingimportantdevelopmentsinthestatisticalanalysisofgraphs inthetwentiethcentury.Inthe1950s,thisworkwasspearheadedbyPaulErd € os andAlfredRe ´ nyi,whointroducedaninfluentialstatisticalmodelforgenerating randomgraphsandforpredictingsomeoftheirtopologicalproperties(Erdos andRe ´ nyi,1959;see Bolloba ´ s,1998 foroverview).Inan Erd € os-Re ´ nyigraph, thereare N nodesandauniformprobability p ofeachpossibleedgebetween them.If p isclosetoone,thegraphisdenselyconnectedandif p isclosetozero, thegraphissparselyconnected.Erd € osandRe ´ nyishowedthatmanyimportant propertiesofthesegraphs,suchasthemeannumberofconnectionsattachedto anysinglenode(alsocalledthemeandegreeofthegraph),andwhetherthe graphisasingle connectedcomponent orcontainsisolatednodes(which arenotconnectedtoothernodes),couldbepredictedanalyticallyfromtheir generativemodel (Chapters 4, 6,and 10).

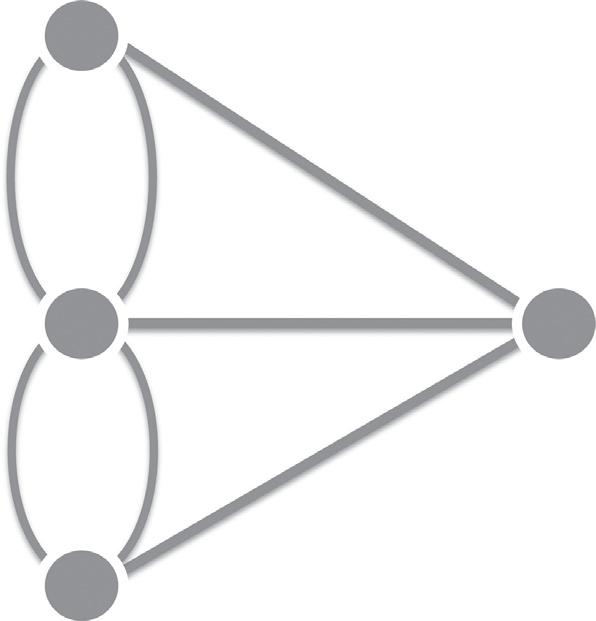

BoththeKonigsberggraphinventedbyEulerandtherandomgraphsgenerated bytheErdos-Re ´ nyimodelareexamplesofthesimplestclassofgraphs:binary undirectedgraphs.Theyarebinarygraphsbecausetheedgesareeitherabsentor presentor,equivalently,theedgeweightiseitherzeroorone.Theyare undirectedgraphs becausetheedgesconnectnodessymmetrically;nodistinctionis madebetweenthesourceandtargetofaconnection.Theprinciplesoftopologicalanalysishavesincebeenextendedtomoresophisticatedgraphsthat includebothweightedanddirectedconnectivity(Chapter3).Aswewillsee inlaterchapters,theseextensionsareparticularlyimportantforcharacterizing certainkindsofbrainnetworkdata.

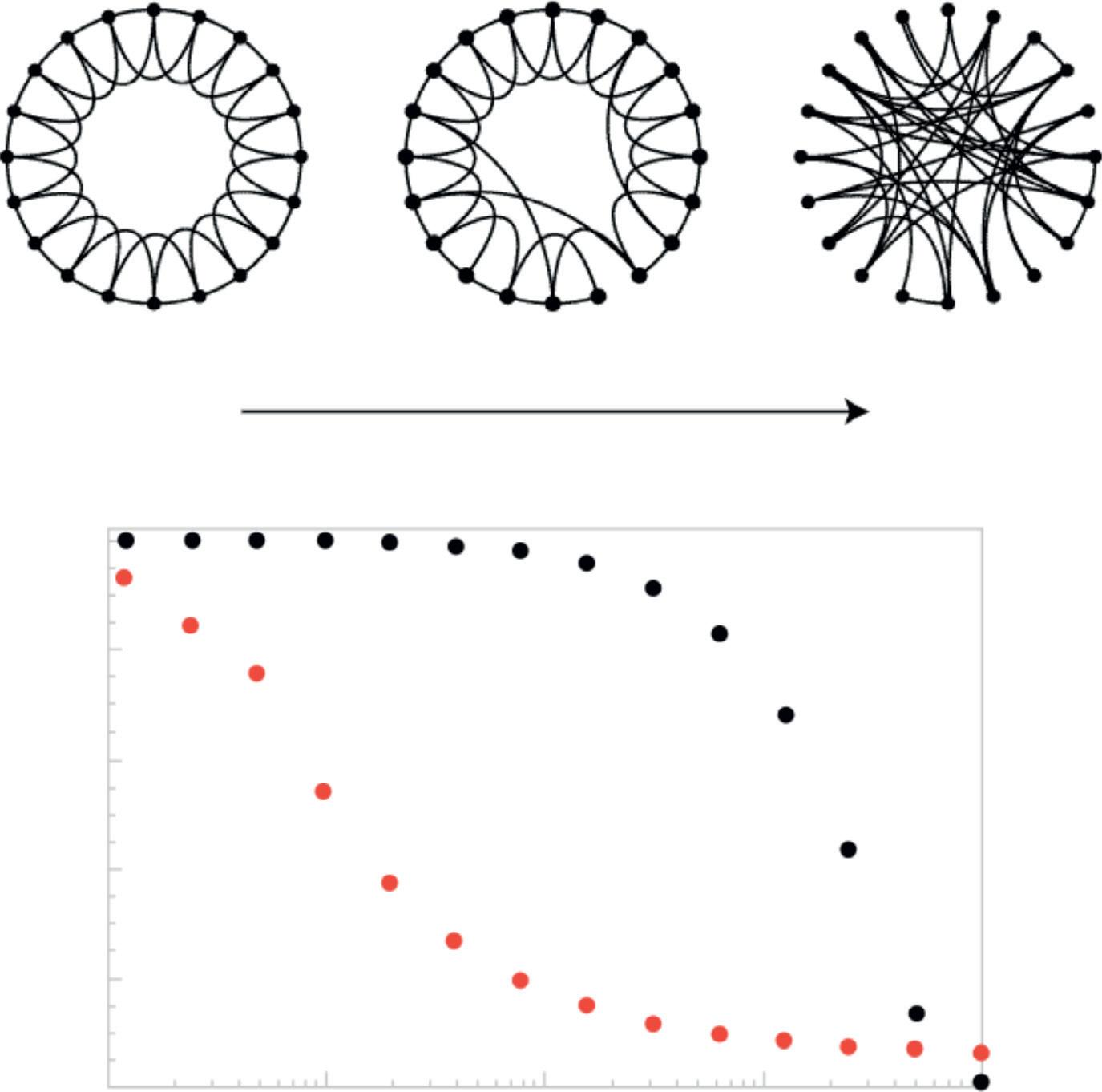

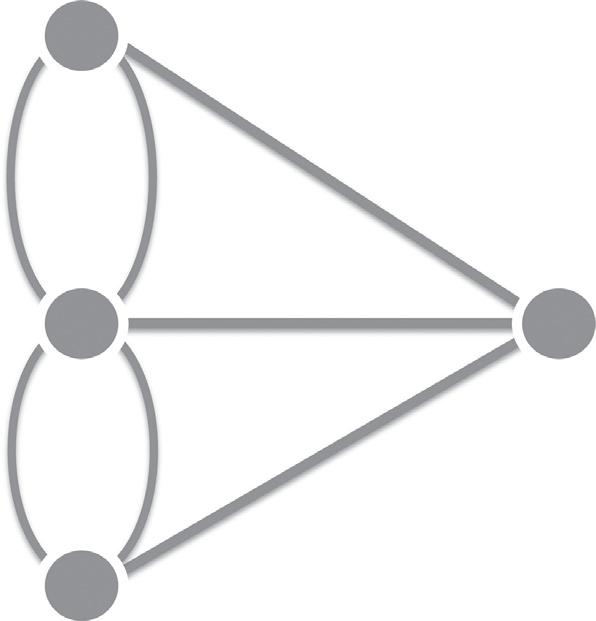

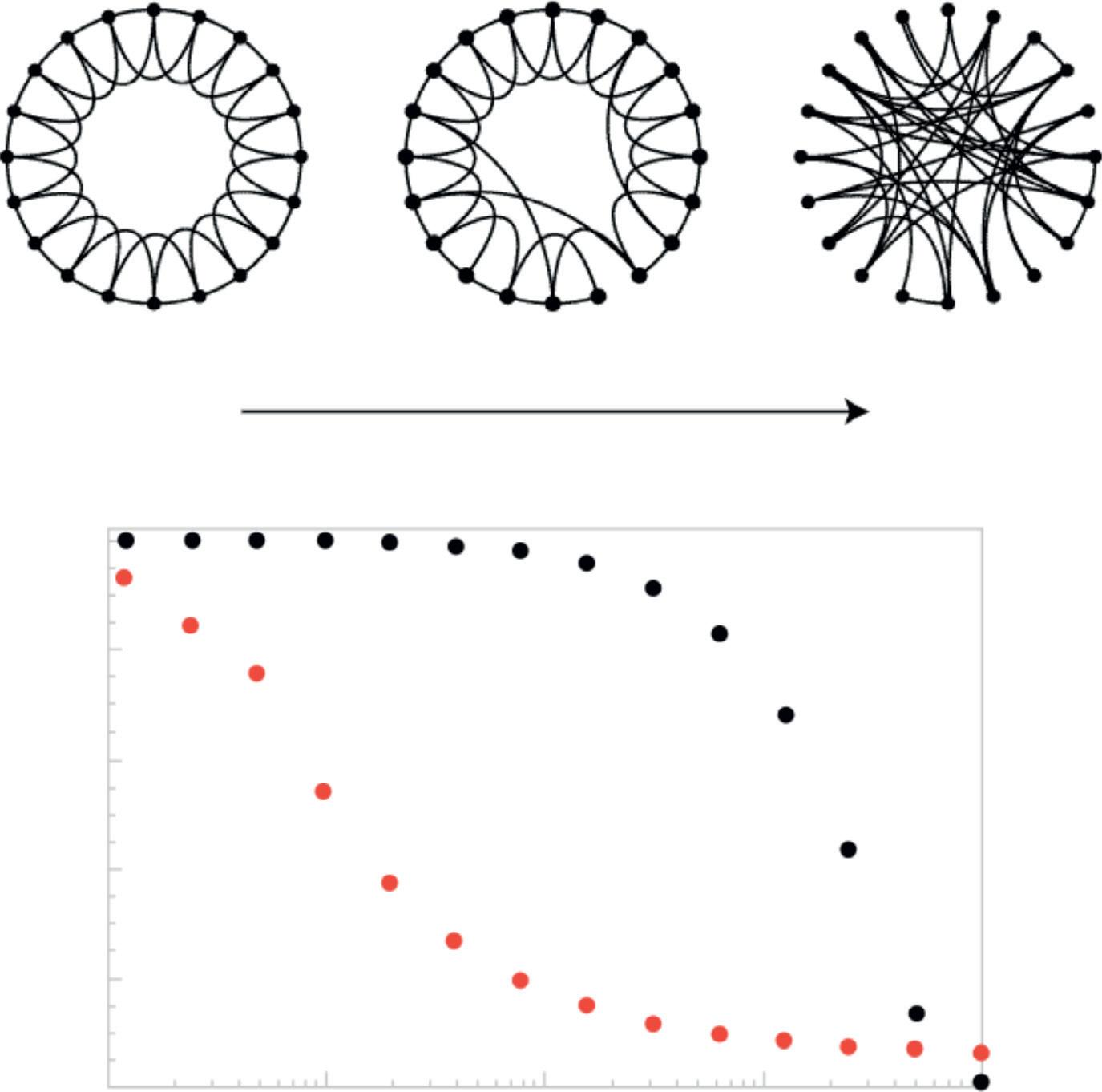

Acriticalstepfromthemathematicsofrandomgraphtheorytothephysicsof complexnetworkswastakenbyDuncanWattsandStevenStrogatz(Wattsand Strogatz,1998; Figure 1.3).LikeErdosandRe ´ nyi,theydefinedagenerative

modelforgraphs;buttheybegantheiranalysiswithasimpleregular lattice of N nodes,eachconnecteddirectlytoanarbitrarynumberofothernodes. The Watts-Strogatzmodel thenrandomlyselectsanedgeconnectingnodes i and j inthelatticeandincrementallyrewiresthegraphsothatthisedge nowconnectsnode i toanotherrandomlyselectednode, h,suchthat h 6¼ j.This generativeprocessofrandommutationofconnectivitycanbeappliedtoeach edgewithanarbitraryprobabilityofrewiring pWS,sothatwhen pWS ¼ 1,allthe edgeshavebeenrandomlyrewiredandthelatticehasbeentopologicallytransformedtoanErdos-Re ´ nyirandomgraph(furtherdetailsofthesemodelsare consideredin Chapter10).

WattsandStrogatz(1998) focusedontwokeypropertiesoftheirnetworkmodel: the clusteringcoefficient andthe characteristicpathlength.Theclusteringcoefficientprovidesanindexofthecliquishnessorclusteringofconnectivityina graph,andistheprobabilitythattwonodeseachdirectlyconnectedtoathird nodewillalsobedirectlylinkedtoeachother(Chapter8).Thecharacteristicpath lengthiscommonlyusedtoindextheintegrativecapacityofanetworkandisa measureofthetopologicaldistancebetweennodes,computedastheminimum numberofedgesrequiredtolinkanytwonodesinthenetwork,onaverage (Chapter7).Theintuitionisthatashorteraverage pathlength resultsinmore rapidandefficientintegrationacrossthenetwork(LatoraandMarchiori,2001). Randomgraphshaveashortcharacteristicpathlengthandlowclustering.Onthe otherhand,theregularlatticeanalyzedbyWattsandStrogatzhashighclustering andlongcharacteristicpathlength(Figure1.3).

ThefirstcriticaldiscoveryrevealedbycomputersimulationsoftheWattsStrogatzmodelwasthattherateofchangeinpathlengthwasmuchfaster thantherateofchangeinclustering,astheprobabilityofrewiringanedge inthelatticewasprogressivelyincreasedfromzerotowardsone.Specifically, changingjustafewedgesinthelatticedramaticallydecreasedthecharacteristicpathlengthofthegraph,butdid notgreatlyreducethehighaverage clusteringthatcharacterizedthelattice.Inotherwords,therewasarange ofrewiringprobabilitiesthatgeneratedgraphswithahybridcombination oftopologicalproperties:shortpathlength,likearandomgraph,andhigh clustering,likealattice.Byanalogytothequalitativelysimilarproperties ofsocialnetworks,firstexploredby Milgram(1967),thesenearly-regular andnearly-randomgraphswerecalled small-world networks.Thesecond maindiscoveryreportedbyWattsandStrogatzwasbasedonempiricalanalysis.Theymeasuredthepathlengthan dclusteringofgraphsrepresenting threereal-lifesystemsandfoundthatthesmall-worldcombinationof greater-than-randomclusteringwithnearly-randompathlengthwascharacteristicofallthree:asocialnetwork(costarringmovieactors),aninfrastructuralnetwork(anelectricalpowergrid),andtheneuronalnetworkof thenematodeworm, Caenorhabditiselegans

FIGURE1.3 Small-worldnetworks. (a) Theseminalworkof WattsandStrogatz(1998) identifieda continuumofnetworktopologiesrangingfromcompletelyregularandlattice-like(left)tocompletely random(right).Interposedbetweentheseextremesisaclassofnetworkswithaso-calledsmall-world topology,whichcanbegeneratedbyrandomlyrewiring(withprobability, p WS)anarbitraryproportionof edgesinaregularnetwork. (b) WattsandStrogatzfoundthatrewiringjustafewedges(small p WS)ledto adramaticreductioninpathlength(redline),whereashighclusteringwasmoreresilienttorandom rewiring(blackline),resultinginaregimeofrewiringprobabilityinwhichthenetworkshowedhigh clustering,likealattice,andlowpathlength,likearandomnetwork.Theredandblacklinescorrespondto theaverageclusteringcoefficientandaveragepathlength,respectively,ofthegraphatagiven p WS, dividedbythecorrespondingvaluecomputedinacomparablelattice.Thecombinationofhighclustering andshortpathlengthisthedefiningcharacteristicofsmall-worldnetworksandhassincebeendescribedin manyreal-worldsystems. Imagesreproducedfrom WattsandStrogatz(1998) withpermission.

9 1.1GraphsasModelsforComplexSystems

Ataboutthesametime, Baraba ´ siandAlbert(1999) introducedanothergenerativemodelthatbuiltacomplexgraphbyaddingnodesincrementally (Chapter10).Inthismodel,aseachnewnode i isaddedtothegraph,the probabilitythatitwillformaconnectionoredgetoanyothernode, j,isproportionaltothenumberofconnections,ordegree,ofnode j.Inotherwords, newnodesconnectpreferentiallytoexistingnodesthatalreadyhavealarge numberofconnectionsandthusrepresentputativenetwork hubs.Bythis generativeprocessof preferentialattachment,the“richgetricher,”ornodes thathavehighdegreeinitiallytendtohaveevenhigherdegreeasthegraph growsbyiterativeadditionofnewnodes.Asaresult,thedistributionofdegree acrossnetworknodesisnottheunimodalPoisson-likedistributionthatis characteristicoftheErdos-Re ´ nyimodel;insteaditischaracteristicallyfat-tailed, conformingtowhatiscalleda scale-free orpower-lawdistribution.Ascale-free degreedistribution meansthattheprobabilityoffindingaveryhighdegree hubnodeinthegraphisgreaterthanwouldbeexpectedifthedegree distributionwasunimodal,likeaPoissonorGaussianfunction.Moresimply, itislikelythatascale-freenetworkwillcontainatleastafewhighlyconnected hubnodes(Chapters 4 and 5).Baraba ´ siandAlbertalsofoundevidenceof power-lawdegreedistributionsinseveralempiricallyobservedcomplex systems.

Liketheapparentubiquityofsmall-worldness,thefactthatsomanysubstantivelydifferentsystemssharethepropertyofscale-freedegreedistributions suggestedthatsomekeytopologicalprinciplesmightbenearlyuniversal foralargeclassofcomplexnetworks(Baraba ´ siandAlbert,1999).However, itisimportanttoappreciatethattheempiricalubiquityofsmall-worldnessor scale-freedegreedistributionsdoesnotbyitselfmeanthatrandomedge rewiringorpreferentialattachmentisthegenerativemechanismthat builtallthesesystemsinreallife.Systemswithcomplextopologicalproperties,likesmall-worldsandhubs,canbegeneratedbymanydifferentgrowth rules.

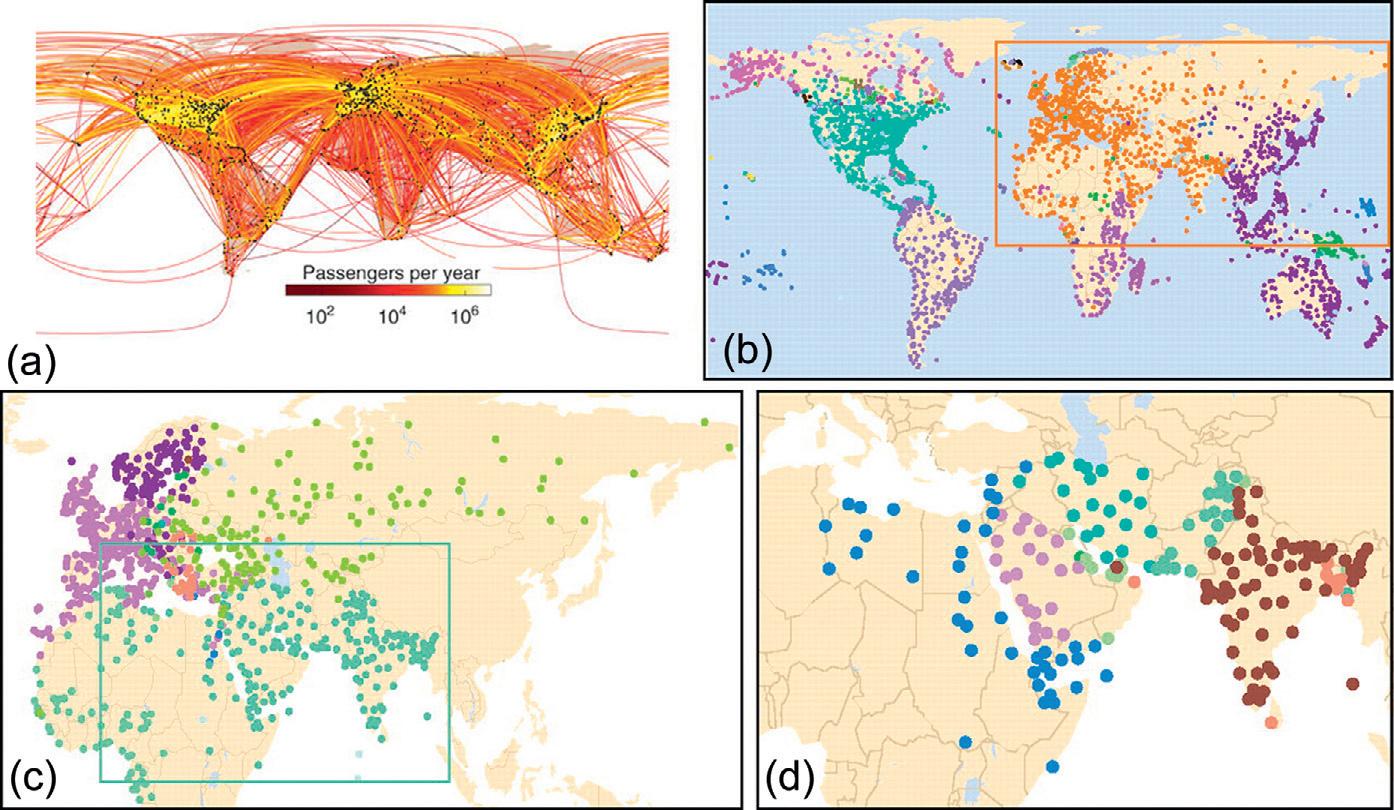

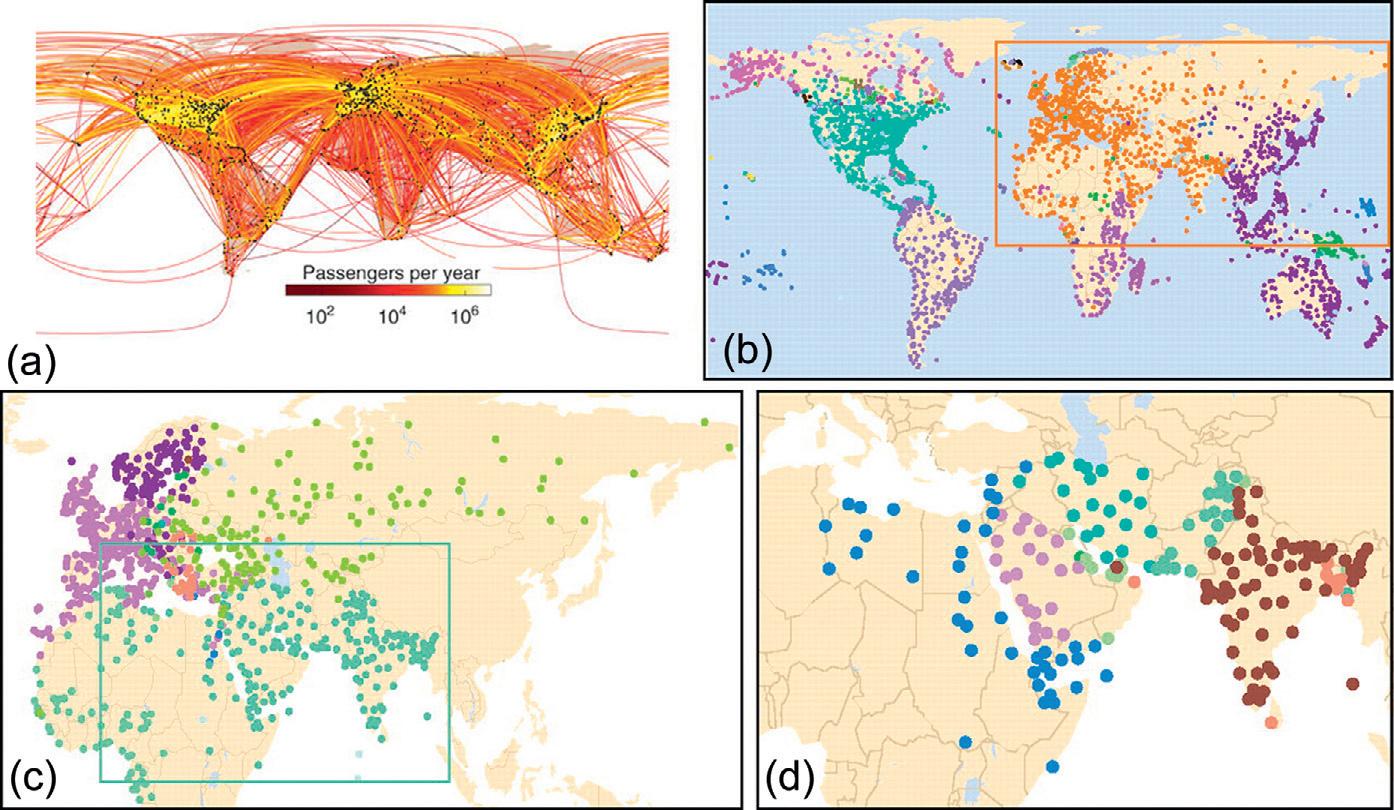

Athirdmajordevelopmentintheapplicationofgraphtheorytoreal-worldsystemshasbeenthediscoverythatsuchnetworksaremodular—theycanbe nearlydecomposedintosubsetsofnodesthataremoredenselyconnected toeachotherthantonodesinanyother modules (Simon,1962).Following workbyMarkNewman,MichelleGirvan,others(GirvanandNewman, 2002;NewmanandGirvan,2004;Newman,2004c;2006;foradetailedreview, see Fortunato,2010),thequantificationofnetwork modularity hasbecomea largeandrapidlydevelopingareaofcomplexnetworkscience(Chapter9).For example,theglobalairlinenetwork,wherenodesareairportsandedgesare directflightsbetweenthem,hasahierarchicalmodularstructure,inwhich modulescanbefurtherdecomposedintosubmodulesandsoon(Guimerà etal.,2005; Figure1.4).Eachtopologicalmoduleoftheairlinenetworkcorrespondsapproximatelytoageographicalcontinentorpoliticalterritory,likethe

FIGURE1.4 Hierarchicalmodularorganizationoftheglobalairtransportationnetwork. (a) A geographicalrepresentationoftheworldwideairlinenetwork.Blackdotsrepresentairports(nodes),and coloredlinesrepresentpassengertrafficbetweenairports(edges). (b) Thisnetworkhasahierarchical modularstructure,suchthatmodulescanbefurtherdividedintosubmodulesandsoon.Shownhereisthe highestlevelofthemodulehierarchy,plottedonageographicmapoftheworld.Colorscorrespondto differentmodules.Themodularorganizationisstronglydominatedbygeographiclocation,suchthat airportsinthesamecontinentareinthesamemodule.Thisisconsistentwiththefactthatmostflightslink airportsinthesamecountryorcontinent. (c) Thenextlevelinthehierarchy,focusingontheorange Eurasianmodule(box)in (b).Thismodulenowsplitsintodifferentsubmodules,suchasScandinavia, centralEurope,WesternRussia,theMiddleEast,andNorthAfrica. (d) Thenextlevelinthehierarchy, focusingontheMiddle-Easternsubmodulein (c).Again,weseeatendencyforairportstosegregateinto sub-submodules(likeIndia)accordingtotheirgeographiclocationsandpoliticalaffiliations. (a) Reproducedfrom Gradyetal.(2012) withpermission. (b-d) reproducedfrom Sales-Pardoetal. (2007),Copyright(2007)NationalAcademyofSciences,U.S.A.,withpermission.

UnitedStatesortheEuropeanUnion.Thisrepresentsthefamiliarexperience thatmostflightsfromaUSorEUairportaretootherairportsinthesameterritoryorcontinentallandmass;onlyafewbigairports,correspondingtohigh degreehubs,suchasNewYorkJFKandLondonHeathrow,havemanyintercontinentalflights.Inanetworkwithhightopologicalmodularity,thedensity ofintramodularconnectionsismuchgreaterthanthedensityofintermodular connections.Typicallymostoftheintermodularcommunicationsaremediatedbyafewso-calledconnectorhubsthatlinkdifferentmodules(Guimerà etal.,2005).Itturnsoutthatmanyreal-lifesystemssharethistopologicalpropertyofmodularity,againsuggestingthatitrepresentsanearuniversalcharacteristicofcomplexnetworks(Simon,1962).

Thesethreekeyconceptsofgraphtopology—small-worldness,degreedistribution,andmodularity—arethetipofanicebergofcomplexnetworkscience. Additionally,therehasbeengrowinginterestinthedyadicsubdivisionofanetworkintoarelativelysmallcoreor richclub ofhighlyinterconnectedhigh degreehubsandalargerperipheryofsparselyinterconnectedlowerdegree nodes(Colizzaetal.,2006; Chapter6).Therehasalsobeenimportantwork toidentifythetopological motifs ofanetwork:basicbuildingblocksofconnectionprofilesbetweensmallsetsofthreeorfournodesthatrecurinanetworkwithafrequencythatisgreaterthanexpectedbychance(Chapter8). Graphsfurtherprovideapowerfulapproachforsimulatingtheeffectsofdamage toanetworkbystudyinghowglobaltopologicalproperties,suchasnetworkconnectednessorcharacteristicpathlength,areaffectedasthenodesoredgesofa grapharecomputationallydeleted(Chapter6).Mostcomplexnetworksarefairly resilienttorandomattackontheirnodes,butaremuchmorevulnerabletoatargetedattackthatprioritizesthehighestdegreehubnodes(Albertetal.,2000).For example,iftheglobalairlinenetworkwasattackedoneairportatatime,butthe choiceofwhichnodetoattacknextwasmadeatrandom,averylargenumberof airportswouldneedtobedisabledbeforeintercontinentaltrafficwasaffected. Thisisbecauseonlyasmallnumberofairportsservicelong-haulflights.However, iftheattacksweretargetedonthosefewmajorhubairports,likeJFKorLondon Heathrow,thiswouldbeequivalenttoremovingmostoftheintermodularflights betweentheUSandEUmodules.Theresultwouldbeadramaticincreaseinthe numberofflightsrequiredtolinktwocitiesondifferentcontinents(i.e.,increased pathlength)andpotentiallya fragmentation ofthenetworkintotwoormore completelyisolatedmodules.Inthisway,hubscanincreasethevulnerability ofmanycomplexnetworkstotargetedattack(Chapter6).

1.1.2Space,Time,andTopology

Asishopefullybecomingclear,topologyisanimportantaspectofhowmany networksareorganized;butotherdimensionsmustalsobeconsideredinthe analysisofmost,ifnotall,typesofnetworks.Somecomplexnetworks,like theWorldWideWeborthesemanticwebofShakespeare’ssonnets(Motter etal.,2002),arequitepurelytopological:theydon’treallyexistinspace(the web),orspaceandtime(sonnets).Thereare,however,manyothercomplexnetworks,particularlybiologicalnetworkssuchasthebrain,thatareembeddedin spatialdimensionsandaredynamicallyactiveovertime.Forbrainnetworkanalysis,thefamiliarthree-plus-onedimensionsofspaceandtimemustthusbe incorporatedwiththemorenovelfifthdimensionoftopology.

Forspatialnetworksgenerallytherewillbeinevitableconstraintsonhowthe topologicalplancanactuallybebuiltinthethreedimensionsoftheworld (Barthe ´ lemy,2011).Forexample,tobuildahigh-performancecomputerchip,

eachprocessingnodeorlogicgatemustbephysicallywiredtoanumberof othernodesaccordingtoatopologicallycomplexdesignforhighperformance. Itisalsoimportantthatthetotalamountofwiringusedshouldbeassmallas possible,becausewiringisexpensiveandgeneratesthermalnoise.Furthermore,itisusuallymandatedthatthetopologymustbeembeddedinonly twodimensions,onthesurfaceofasiliconchip.Empiricalanalysisandgenerativemodelingofcomputercircuitsandotherspatialnetworkshasindicated thatconservationofwiring cost isanimportantfactorinnetworkformation thatoftendrivesthephysicallocationandconnectivityofnodes,suchthatspatiallyproximalnodeshaveahigherprobabilityofconnectivitythanspatially distantnodes(ChristieandStroobandt,2000).However,minimizationofwiringcostisclearlynottheonlyselectionpressure,otherwiseallspatialnetworks wouldbelow-dimensionallatticeswithtopologicallyclusterednodesembeddedasclosetoeachotheraspossibleinphysicalspace.Accordingly,generative modelsthatpositatrade-offorcompetitionbetweencostminimizationand someothertopologicalfactorthatprovidesfunctionalbenefits,havebeenmore successfulinsimulatingtheorganizationofspatialnetworks(Ve ´ rtesetal.,2012). Sucheconomicalprinciplesofcompetitionbetweenphysicalcostandtopologicalvaluemaybegenerallyinfluentialintheformationofnetworksembeddedin space(LatoraandMarchiori,2001;AchardandBullmore,2007; Chapter8).

Mostnetworkswillalsobeactiveovertimewithdynamicsthatarerelatedtothe functionalperformanceofthesystem.Perhapsunsurprisingly,thestructural topologyofanetworkhasanimportantinfluenceonthefunctionaldynamics thatemergefrominteractionsbetweennodesovertime.Networkswith complextopologyhavecomplexdynamics,broadlyspeaking.Forexample, networksdisplayinghighdynamicalcomplexity—thatis,dynamicswhich areneitherfullysegregatednorfullyintegrated—showacomplex,small-world topology(Spornsetal.,2000;see Chapter8).

Ithasalsobeenshownthatsmall-worldandscale-freenetworktopologiesare associatedwiththeemergenceofso-calledcriticaldynamics(Chialvo,2010). Self-organizedcriticaldynamicsareofteninferredwhenfunctionalinteractions betweennodesexistatallscalesofspaceandtimeencompassedbythesystem andarestatisticallydistributedaspowerlaws(Chapter4).Topologically complexnetworkshavebeenlinkedtotheemergenceofsuchscale-invariant networkdynamics,whichareconsistentwiththesystembeinginaselforganizedcriticalstatethatisinterposedbetweencompletelyorderedanddisordereddynamics(Baketal.,1987).Criticaldynamicshavebeenshowncomputationallytohaveadvantagesforinformationprocessingandmemory,and experimentallytheyhavebeeninferredfrompower-lawscalingofdynamicsin manynervoussystems,fromculturedcellularnetworkstowholebrainelectrophysiologicalandhaemodynamicrecordings(Linkenkaer-Hansenetal.,2001; BeggsandPlenz,2003;Kitzbichleretal.,2009).Ingeneral,networktopology

playsanimportantroleinconstrainingsystemdynamics;and,reciprocally, systemdynamicscanoftendrivetheevolutionordevelopmentofnetwork topology.

1.2GRAPHTHEORYANDTHEBRAIN

Aswehaveseen,graphtheoryhasplayedanintegralroleinrecenteffortsto understandthestructureandfunctionofcomplexsystems.Nervoussystems areundoubtedlycomplex,soitisnaturaltoassumethatgraphtheorymayalso proveusefulforneuroscience.Importantly,graph-basedrepresentationsof brainnetworks—braingraphs—caneasilybeconstructedfromneuralconnectivitymatrices,suchastheonesdepictedin Figure1.1.Eachroworcolumn representingadifferentbrainregioninthematrixisdrawnasanodeinthe graph,andthevaluesineachmatrixelementaredrawnasedges.Infact,as wewillseethroughoutthisbook,matrixandgraphrepresentationsofanetworkareformallyequivalent,andmuchofthemathematicsofgraphtheory isappliedthroughtheanalysisofmatrices.Inthissection,weconsiderhow graphtheoryhasbeenappliedtounderstandbrainnetworksandhowithas emergedasapowerfulanalytictoolforconnectomics.

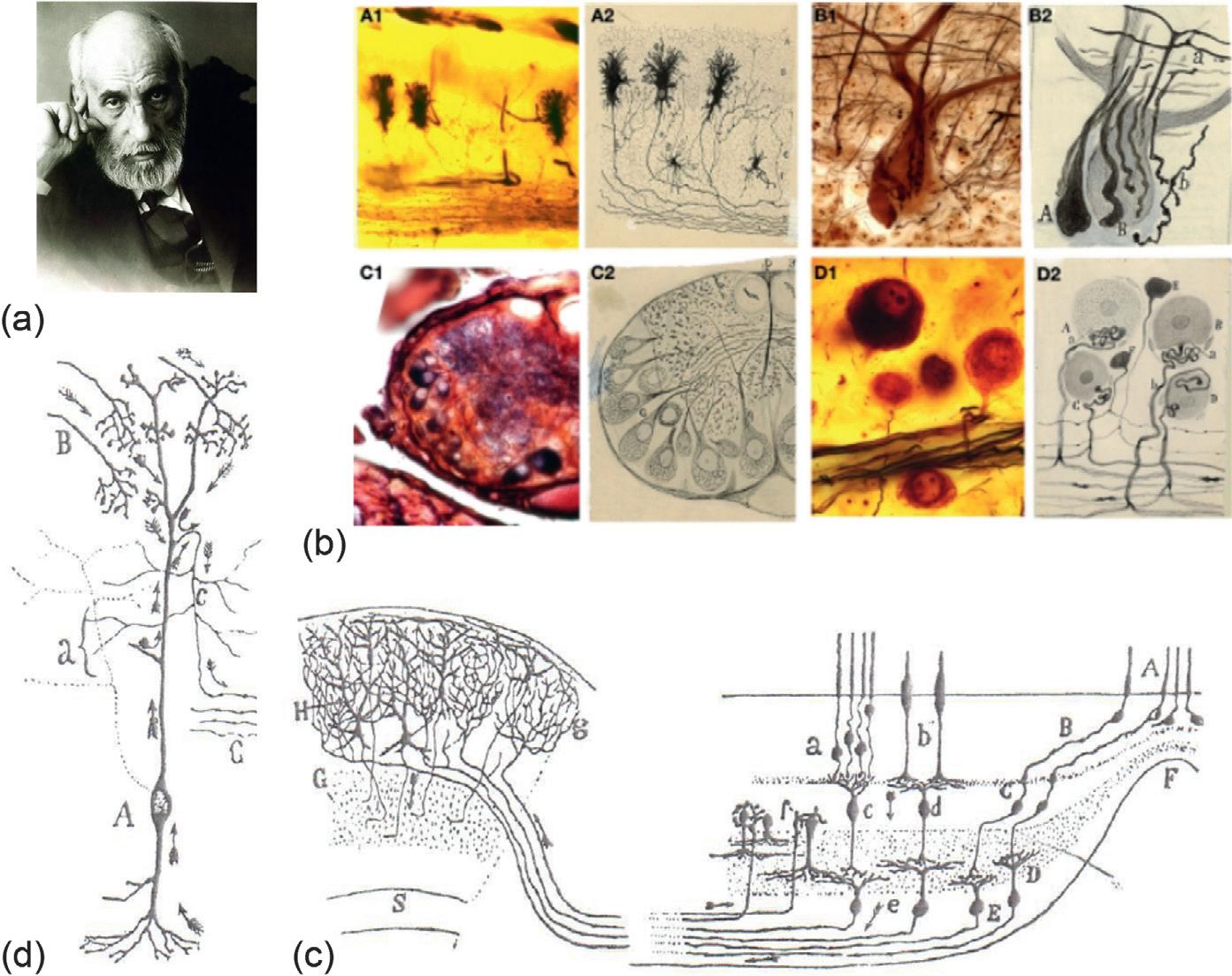

1.2.1TheNeuronTheoryandConnectivityattheMicroscale Whendidtheideasofgraphtheoryandnetworksciencefirstbegintopermeate neuroscience?Formally,thefirstapplicationsofgraphtheorytoneuroscientific datawerenotpublisheduntiltheendofthetwentiethcentury(Fellemanand VanEssen,1991;Young,1992;WattsandStrogatz,1998).However,theseminal neurontheory,establishedbyRamo ´ nyCajal’sbrilliantmicroscopicstudiesand theoreticalthinkinginthelatenineteenthandearlytwentiethcentury(Ramo ´ ny Cajal,1995),setthesceneforgraphtheorytolatermakesenseasamodelofnervoussystems(Figure1.5).Ramo ´ nyCajalandsomeothers,usingthethenrevolutionarytechniqueofsilverimpregnationtovisualizethecomplexbranchingprocessesofindividualneurons,claimedthatneuronswerediscretecellsthat contactedeachotherverycloselybysynapticjunctions.Thismodelcontradicted theprincipalalternativeparadigm,thereticulartheoryadvocatedbyCamille Golgi,whoinventedtheneuronalstainingmethodusedbyRamo ´ nyCajal. AccordingtoGolgi,therewasacontinuoussyncytialconnectionbetweenthecell bodiesofthenervoussystem.BothmensharedtheNobelPrizein1906,butit wasnotuntilthe1950swhen electronmicroscopy finallyresolvedthetheoreticalquestioninfavorofRamo ´ nyCajal(DeRobertisandBennett,1955). Itisnowacceptedbeyonddoubtthatsynapticjunctionsaregenerallypointsof closecontiguity,butnotcontinuity,betweenconnectedneurons.Ramo ´ ny Cajal’smodelofdiscreteneuronsinterconnectedbysynapsesisnaturallysuited

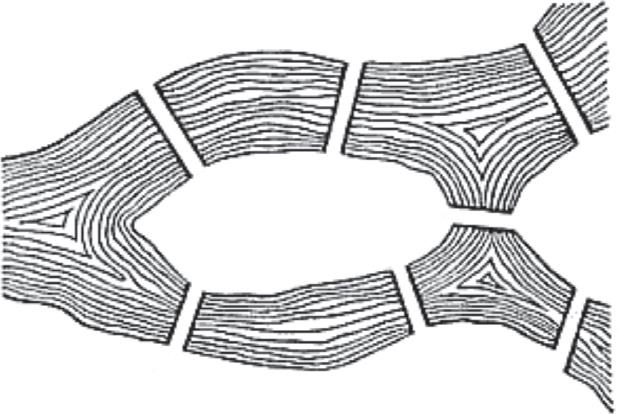

FIGURE1.5 ThepioneeringworkofRamo ´ nyCajal(1852-1934). (a) SantiagoRamo ´ nyCajal madecountlessmicroscopicslidepreparationsofnervoustissue(coloredslidesin (b)),andrecordedthe dataforpublicationbypenandinkdrawings(monochromepanelsin (b)).Morethanacenturyafter thepublicationofhiswork,itiseasytorecognizemanyexamplesofclosecorrespondencebetween stainedcellsanddrawncells. (c) Fromtheseobservations,Ramo ´ nyCajalevolvedneurontheory.For example,heshowedhowactivityinretinalconecells(marked A inthedrawing)passedviasynaptic junctionstofovealbipolarandganglioncells(C )andwasthenprojectedtoaxonalarborizations(g ) terminatingincloseproximitytoneuronsinthesuperiorcolliculus(H ).RamonyCajalalsoformulated lawsofconservationofspace,time,andmaterialtoexplainthemorphologicaladaptationsof individualneurons. (d) Theso-calledshepherd’scrookcellofthereptilianopticlobe,forexample, hadtheunusualcharacteristicthattheaxon(marked C onthedrawing)didnotemergeclosetothe cellbody(A).Ramo ´ nyCajalarguedthatthisapparentlyoddaxonallocationwasmandatedbythe conservationofmaterialorcytoplasm(inmodernparlance,minimizationofwiringcost).Assuming correctlythatelectricalactivitymustflowfromallotherpartsoftheneurontowardstheaxonandits collateralramifications(markedbyarrows),hereasonedthatallotherpossiblelocationsofthe axonalhillockwouldbeassociatedwith“wasteofmaterial”or“unnecessarylengthening”of theaxonalprojection. (b) Reproducedfrom Garcia-Lopezetal.(2010) and (c,d) from Ramo´nyCajal(1995) withpermission.

toagraphtheoreticrepresentation,wherebyneuronsarerepresentedbynodes andaxonalprojectionsorsynapticjunctionsarerepresentedbyedges.Inthis way,onemightargue,Ramo ´ nyCajalwasthegiantonwhoseshouldersgraph theoreticanalysisofneuralsystemsformallyemergedsome100yearslater.

OneothertheoreticalcontributionbyRamo ´ nyCajalthatremainsinfluential inconnectomicsishisproposalofafewapparentlysimplegenerallawstogovernmost,ifnotall,aspectsofnervoussystemanatomy.Hesummarizedthese rules,alsocalledCajal’sconservationlaws,inthefollowingwords:

Doubtforusisunacceptable,andallofthemorphologicalfeaturesdisplayed byneuronsappeartoobeypreciserulesthatareaccompaniedbyuseful consequences.Whataretheserulesandconsequences?Wehavesearchedin vainforthemoverthecourseofmanyyears Finallyhoweverwerealized thatallofthevariousconformationsoftheneuron… aresimply morphologicaladaptationsgovernedbylawsofconservationfortime,space andmaterial whichmustbeconsideredthefinalcauseofallvariationsin theshapeofneurons,[and]shouldinourviewbeimmediatelyobviousto anyonethinkingaboutortryingtoverifythem.

Ramo ´ nyCajal(1995),p.116,VolumeI.

Inmoremodernlanguage,Ramo ´ nyCajalanticipatedthatmanyaspectsof brainnetworkorganizationwouldbedrivenbothbyminimizationofaxonal wiringcost,whichconservescellularmaterialandspace;andbyminimization ofconductiondelayinthetransmissionofinformationbetweenneurons, whichconservestime(Figure1.5;seealso Chapter8).

Itturnsoutthatmanyaspectsofbrainnetworkorganizationdoindeedseem tohavebeenselectedtominimizewiringcostand/ortominimizemetabolic expenditure(NivenandLaughlin,2008).Topologicalfeatureslikemodules andclustersareoftenanatomicallycolocalized,whichconservesmaterial.Other aspectsoftheconnectomethatpromotetheefficientintegrationofinformation acrossthenetwork,suchasshortcharacteristicpathlength,mayhavebeen selectedtominimizeconductiondelay,thusincreasingthespeedatwhichinformationcanbeexchangedbetweenneuronsorconservingtime.Connectomics hasthusbeguntorestateandrefineRamo ´ nyCajal’sconservationlawsinterms ofacompetitionbetweenminimizationofwiringcostandmaximizationofintegrativetopology(BullmoreandSporns,2012;BuddandKisva ´ rday,2012).

1.2.2ClinicopathologicalCorrelationsandConnectivityat theMacroscale

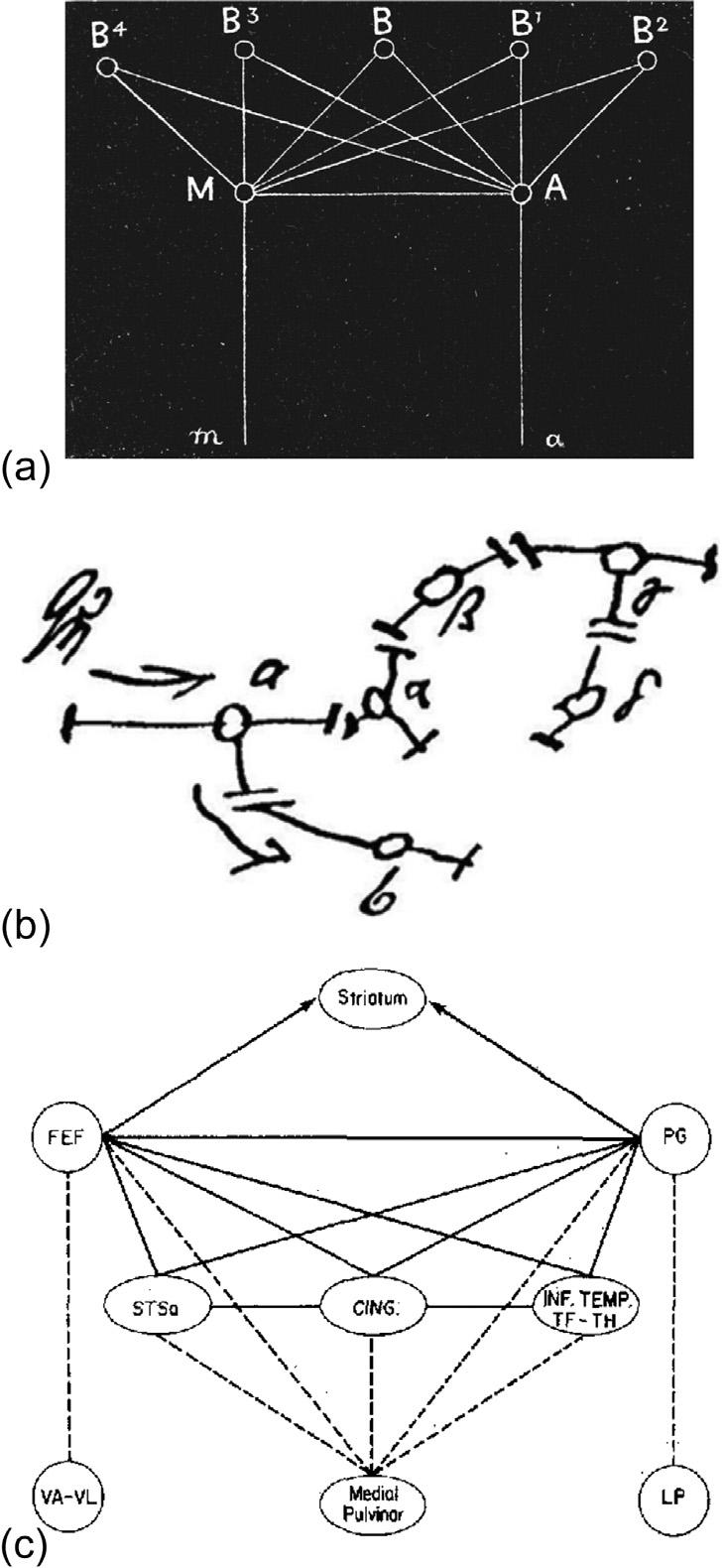

ThefirstattemptstounderstandmacroscopicnetworksofinterconnectedcorticalareasroughlyparalleledRamo ´ nyCajal’sseminalworkonmicroscopic neuronalconnectivity.Networkdiagramsweredrawnbyclinicalpioneerslike

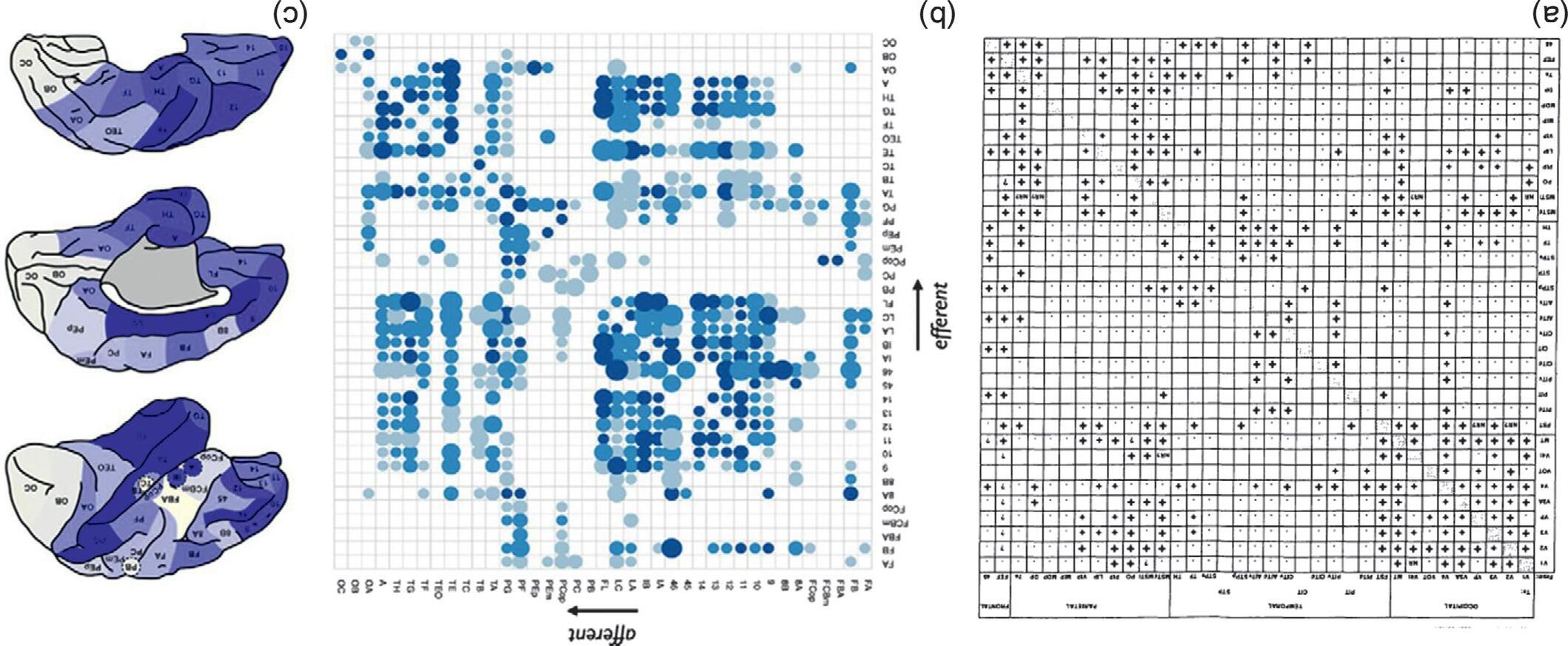

TheodorMeynert,CarlWernicke,andLudwigLichtheimtosummarizewhite matterconnectionsbetweencorticalareas,andtoexplainhowthesymptoms ofbraindisordercouldberelatedtopathologicallesions.TheWernickeLichtheimmodeloflanguageremainsthemostsuccessfuloftheseearlymodels ofmacroscalebrainnetworkorganization,linkingalanguageproductionarea inthefrontalcortextoalanguagecomprehensionareainthetemporalcortex (aswellasamorevaguelylocatedassociationarea).Someaspectsofthismodel wereabletoaccountconvincinglyforthegenerationofspecificsymptoms:in particular,alesionofthearcuatefasciculuslinkingfrontalandtemporallanguageareaswaspredictedandshowntocauseaninabilitytorepeatheard wordsdespiteotherwiseapparentlynormallanguage,so-calledconduction aphasia(Lichtheim,1885; Figure1.6a).Wernickegeneralizedtheseideasas anassociativetheoryofbrainfunction,inwhichhigher-ordercognitiveabilities (andtheirdisorders,suchaspsychosis)werethoughttoemergefromtheintegration(orpathologicaldisintegration)ofanatomicallydistributedyetconnectedcorticalareas(Wernicke,1906).Thenineteenthcenturydiagramsof large-scalebrainnetworkorganizationdrawnbythesepioneers,comprising afewspatiallycircumscribedareas(nodes)interconnectedbywhitematter tracts(edges),setthesceneforgraphtheoreticalanalysisofnervoussystems atthemacroscopicscale,justastheneurontheorylaidthefoundationfor graph-basedmodelsatmicroscopic(cellular)scales.

Oneimportantdifferencebetweenthemacroscopicdiagrammakers,like WernickeandLichtheim,andthemicroscopicanatomists,especiallyRamo ´ ny Cajal,wasthequalityofthedataavailabletothem.Benefittingfromcontemporary technicaldevelopmentsinopticsandtissuestaining,Ramo ´ nyCajal,Golgi,and otherswereabletoproduceverydetailed,high-qualityimagesofneuronsand microscopiccircuits(Figure1.5).Incontrast,themacroscopicdiagrammakers workedwithpoorerqualitydata.Forexample,Wernicke’sworkwasbasedonclinicopathologicalcorrelation,linkingthepatternofsymptomsandsignsexpressed byafewpatientsintheclinicwiththepostmortemappearanceoftheirbrains (Wernicke,1970).Evenatthetime,theunreliabilityofthismethodandthediagnosticformulationsthatfollowedweresharplycriticizedbycontemporaries, including SigmundFreud(1891; Figure1.6b)

Partlyasaresultofthemethodologicalweaknessofpostmortemclinicopathologicalcorrelations,large-scalenetworkconceptsofneurologicalandpsychiatricdisordersweresomewhateclipsedforthefirsthalfofthetwentiethcentury bymorelocallyanatomicalorpurelypsychologicalmodelsofcognitivefunctionandbraindisorders(Shallice,1988).Thelocalizationistambitionpredominantlyfocusedonhowspecificpsychologicalprocessesarosefromthe functionofdiscretebrainregions;orhowspecificfacetsofcognition,emotion, andbehaviorwereanatomicallylocalizedandsegregatedinthebrain. AlthoughthistraditionhasconceptualrootsinGall’sdiscreditedphrenology

FIGURE1.6 Earlybraingraphsbasedonclinicopathologicalcorrelations. (a) Lichtheim’ssketch ofalarge-scalehumanbrainnetworkforlanguage.Broca’sandWernicke’sareas,andthearcuate fasciculuswhichdirectlyconnectedthem,wereanatomicallylocalizedintheleftinferiorfrontalandsuperior temporalcortex.However,thenumberofassociationareasthatshouldbeincludedinthenetworkwas notknown,norwastheiranatomicallocation.Inthismap,Lichtheimspeculatedthattheremaybemany associationareasandthatBroca’sandWernicke’sareaswerethemostdenselyconnectednodesinthe network.Arepresentsanauditoryarea(i.e.,Wernicke’sarea),Mamotorarea(i.e.,Broca’sarea),and Botherassociationareas. (b) AnetworkdiagramdrawnbyFreud,whowasacriticofcontemporaryefforts tomapclinicaldisordersontolarge-scalebrainnetworks.Nonetheless,heoriginallyframedhisnascent theoryofpsychoanalysisintermsofaneuronalnetwork.Thelibido,designatedbyanenigmaticQ-like glyph,flowsacrossweightedsynapticjunctionsbetweenchargedcells,engenderingprimary(id)or secondary(ego)processthinkingaccordingtotheanatomicalpathofcathexis(orchargeoflibidinalenergy) inthenetwork.Psychoanalysissubsequentlymovedawayfromsuchanexplicitlyneuronalmodel, althoughlibidoretainedabiologicalmeaninginFreud’sworkuntilabout1910. (c) Mesulam’slaterand moreanatomicallyaccurate“hubandspoke”modelofspatialattention,whichcomprisesmultiplecortical andsubcorticalareasinterconnectedbywhitemattertracts;thefrontaleyefields(FEF)andposterior parietalcortex(PG)arethemostdenselyconnectedhubsofthenetwork. Panels (a), (b),and (c) reproduced from Lichtheim(1885), Freud(1891,1895),and Mesulam(1990),respectively,withpermission.