https://ebookmass.com/product/filthy-material-modernism-and-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Philosophy in the Condition of Modernism Ana Falcato

https://ebookmass.com/product/philosophy-in-the-condition-ofmodernism-ana-falcato/

ebookmass.com

Modernism and the Meaning of Corporate Persons Lisa Siraganian

https://ebookmass.com/product/modernism-and-the-meaning-of-corporatepersons-lisa-siraganian/

ebookmass.com

The Art of Hunger: Aesthetic Autonomy and the Afterlives of Modernism Alys Moody

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-art-of-hunger-aesthetic-autonomyand-the-afterlives-of-modernism-alys-moody/

ebookmass.com

The Serious Leisure Perspective: A Synthesis 1st ed. Edition Robert A. Stebbins

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-serious-leisure-perspective-asynthesis-1st-ed-edition-robert-a-stebbins/

ebookmass.com

The Benefit of Hindsight Susan Hill

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-benefit-of-hindsight-susan-hill/

ebookmass.com

La última muerte en Goodrow Hill Santiago Vera

https://ebookmass.com/product/la-ultima-muerte-en-goodrow-hillsantiago-vera-5/

ebookmass.com

Geography: Realms, Regions, and Concepts, 16th Edition

https://ebookmass.com/product/geography-realms-regions-andconcepts-16th-edition/

ebookmass.com

Intermediate English Grammar for ESL Learners, 3rd ed 3rd Edition Robin Torres-Gouzerh

https://ebookmass.com/product/intermediate-english-grammar-for-esllearners-3rd-ed-3rd-edition-robin-torres-gouzerh/

ebookmass.com

Failure Analysis of Engineering Materials (McGraw Hill Professional Engineering) 1st Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/failure-analysis-of-engineeringmaterials-mcgraw-hill-professional-engineering-1st-edition-ebook-pdf/ ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/god-guns-and-sedition-bruce-hoffman/

ebookmass.com

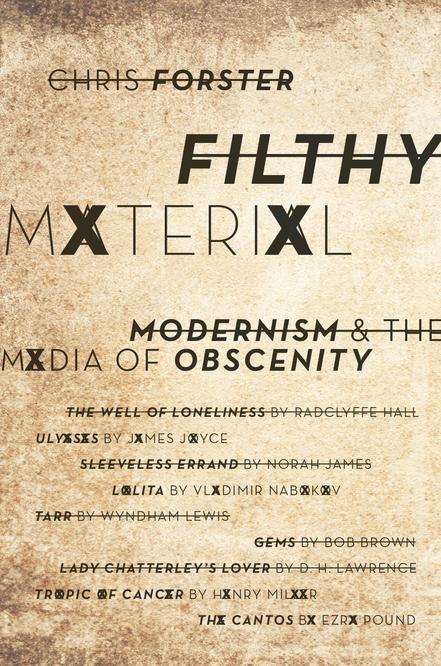

i Filthy Material

Modernism and the Media of Obscenity

1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2019

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Forster, Chris, 1981– author.

Title: Filthy material : modernism and the media of obscenity / Chris Forster.

Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2019] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018008303 (print) | LCCN 2018043124 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190840884 (updf) | ISBN 9780190840891 (epub) | ISBN 9780190840860 (cloth : qalk. paper) | ISBN 9780190840877 (paperback : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: English fiction—20th century—History and criticism. | Modernism (Literature)—Great Britain. | Fiction—Censorship—Great Britain—History—20th century. | Mass media—Social aspects—Great Britain. | Popular culture—Great Britain. | Obscenity (Law)—Great Britain.

Classification: LCC PR888.C45 (ebook) | LCC PR888.C45 F67 2019 (print) | DDC 820.9/3538—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018008303

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback printed by WebCom, Inc., Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

i Contents

Acknowledgments ix

Introduction 1

1. Modernism and the Media History of Obscenity 11

2. The Pornometric Gospel: Wyndham Lewis, Walter Sickert, and the Collapse of the Ideology the Nude 39

3. Skirmishing with Jolly Roger: D. H. Lawrence, Obscenity, and Book Piracy 61

4. Very Serious Books: The Circulation and Censorship of The Well of Loneliness and Sleeveless Errand 89

5. Obscenity and the Voice: Eliot’s Bawdry 125

6. Materializing Ulysses: Obscenity and the Work of Print in the Age of Film 151

Coda. The Next Lawrence or Joyce: The Obelisk and Olympia Presses 181

Works Cited 193 Index 207

Acknowledgments

This book began as a dissertation at the University of Virginia, and though it has traveled considerably from its inception, it would not exist without the early support of its advisers. Michael Levenson encouraged the project even when it was an inchoate mess, and I hope it has grown sufficiently to merit the encouragement he offered. Jennifer Wicke was likewise relentless in her support; my realization that media are a key agent in the history of obscenity can be charted to a meeting in her office. Rita Felski has a clarity of thinking that continues to be a model to which I aspire. Many other readers and audiences helped improve my thinking. Robert Spoo kindly helped to clarify some of the legal questions surrounding copyright and obscenity.

My colleagues at Syracuse University have provided a truly hospitable place to continue working on this project and on others. I could not ask for a better situation.

My debts to librarians (both intellectual and monetary) are enormous. I must offer a blanket thanks to the staffs of both Alderman Library at the University of Virginia and Bird Library at Syracuse University, who indefatigably helped with a whole range of queries. Early in my research I spent some brief time at the Kinsey Archive at Indiana University and the Beinecke at Yale. Although the project progressed elsewhere, those early visits nevertheless shaped my thinking and its direction. In addition, I’d like to thank the British National Archive and the British Library. Christopher Wittick at the East Sussex Record Office helped me try to track down a letter between William JoynsonHicks and H. A. Gwynne. We didn’t find it, but he was enormously helpful and generous.

Acknowledgments

Susan Mizruchi generously helped this book find a home. Norm Hirschy at Oxford University Press has been delightful to work with. Ginny Faber’s copyediting improved the prose of this book enormously.

An earlier version of Chapter 1 was published in The Journal of Modern Literature (Summer 2011). My thanks to Indiana University Press for allowing that material to appear here.

Finally, I should thank my family. My two brothers, Jeremy and Nick, are the intellectuals I most wish to impress, even as they pursue very different objects of study. My parents, Shawn and James, never questioned my decision to study literature. But my greatest thanks must be extended to my partner, Kristen, to whom I owe pretty much everything. To her I promise that, with this sentence, my work on this book ends. (Really.)

Introduction

Think of an obscene or pornographic work of literature. Unless your tastes run to the obscure, the work you selected is probably available at the nearest research library or even bookstore. Whether you imagined the poems of Catullus or Rochester, Nabokov’s Lolita, Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, James Joyce’s Ulysses, or Fifty Shades of Grey, all are readily accessible. If obscene means legally impermissible, then it would seem there are no longer any obscene works of literature. I’ll go further: an obscene work of literature, in the strict sense,1 is, in the United States and England, unimaginable. However sexually explicit, however “prurient” the interests such a work manages to arouse, however shocking or “deviant” it may seem, it is simply not possible to imagine a work of literature that would become the object of an obscenity prosecution.2 As Charles Rembar claimed a half-century ago, “So far as writers are concerned, there is no longer a law of obscenity” (490).

If a half-century separates us from Rembar’s realization that the period of “literary obscenity” had ended, another half-century takes us back to a moment when such obscenity seemed an urgent, pressing problem—a freedom to be fought for or a tide to be turned back. During the height of modernism, major works of literature were routinely

1 By strict sense I mean not protected by the First Amendment in the United States (under the provisions described in Miller v. United States) or, in the United Kingdom, not falling under the protections for works of artistic value outlined in the 1959 Obscene Publications Act. I mean, in short, a work that could be successfully prosecuted for the crime of obscenity.

2 My argument here does not deny that various actors—copyright holders, school districts, individual library systems—may work to prevent access to works (and in some cases may even invoke the language and traditions of obscenity); but such censorship operates very differently, and is motivated by very different concerns, than in the trials and controversies surrounding works of literature in the first part of the twentieth century.

censored or suppressed. How are we to understand that shift? As Elisabeth Ladenson frames the question, “How is it that so many of the works once designated as obscene have ended up on required reading lists? Or, to take up the question from the other end, how is that so many of the works on today’s required reading lists were once prosecuted as obscene? In short: How does an obscene work become a classic?” (xiii). This book argues that this question can only be answered by locating literature within a media environment. Modernist obscenity lies at the intersection of the history of media technology and the history of literature.3

The scandals of modernist literature, including its obscenity trials, are central to our sense of the period. Nothing better captures modernism’s power to upset convention and tradition than obscenity. For those who celebrate modernist literature’s subversive potential, obscenity offers invaluable evidence. It confirms the things we most like to believe about modernism as a radical rejection of the stultifying power of the status quo. In Peter Gay’s popularizing account, modernism is defined by “the lure of heresy.” In Kevin Birmingham’s recent study of Ulysses, the obscenity trials illustrate why Joyce’s novel is “the most dangerous book.” The Playboy riots, the outrage at the first performance of the Rite of Spring, or the scandal of the Armory Show all offer similar narratives of scandal; yet it is obscenity that seems to best capture the subversive power of modernist literature. There is no surer evidence that you’re épatering la bourgeoisie than being hauled into court or accused of corrupting the youth. This tale, of the classic in the courtroom, is often retold to excite skeptical students or to insist on the importance of literature. Yet such celebrations of modernist transgression risk a certain hollowness. Like the “cheap enjoyment” described by Freud in Civilization and Its Discontents “obtained by putting a bare leg from under the bedclothes on a cold winter night and drawing it in again” (40)— it is a thrill purchased without real cost, a celebration of the transgressing of rules that no one cares to enforce any longer. What is at stake? Retellings of modernism’s provocations access the transgressive histories and potentials of works that have long since received the sanction of both the law and the classroom. As Ladenson notes, “By the end of the twentieth century, countercultural aesthetics had thoroughly filtered into such mainstream media as advertising . . . subversion and transgression had become positive values in themselves” (xix–xx). Such narratives threaten to devolve into mere self-congratulation. At worst, they distort the complexity of the period. As Sean Latham suggests, “An almost obsessive focus on the famous obscenity trials of Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover” has been “part of a liberal romance of art’s ever-expanding freedom. These now iconic texts have assumed a status that exceeds their considerable artistic merit precisely because they

3 I will use the admittedly imprecise phrase “modernist obscenity” to refer to the broad discourse of obscenity in the modernist period, best exemplified by the controversy surrounding Ulysses, The Well of Loneliness, and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, among others.

fit so well into a progressive historical narrative that couples sexual liberation to artistic innovation” (72).

If, despite Latham’s warning, Filthy Material returns our attention yet once more to the obscenity trials of Ulysses and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, it does so to see them anew, outside the terms of that now well-established liberal romance. In so doing, it joins other accounts of obscenity in the modernist period, which have complicated the triumphalist narrative. Deana Heath, for instance, notes the ways in which the liberalization narrative recapitulates what Foucault famously described as the “repressive hypothesis,” and with it a freedom/ censorship dialectic which ignores the more complex ways that power operated through censorship (48–52). Important accounts by Adam Parkes, Allison Pease, Celia Marshik, Elisabeth Ladenson, Loren Glass, and Rachel Potter have all complicated the simple “struggle for expression” narrative. Marshik, for instance, provocatively suggests that censorship, far from being a uniformly repressive force, provoked many of modernism’s “trademark aesthetic qualities—such as self-reflexivity, fragmentation, and indirection” (British Modernism 6).4

This book follows the lead of those others by seeking to complicate modernist obscenity, to offer an account of obscenity’s role in modernism as something more than a conflict between writers and “the grey elderly ones” or “the censor morons” (both phrases, unsurprisingly, come from D. H. Lawrence). Rather than rehearse the narrative of the struggle and triumph of heroic artists over repressive governments and ignorant philistinism, Filthy Material argues that modernist obscenity might valuably be understood as a proxy war between different media, at a moment when the mediatechnological landscape inherited from the nineteenth century (itself already riven with changes and shifts) underwent rapid change. This is not to deny the genuinely subversive power of modernist literature, or the truly heroic roles played by such figures as Sylvia Beach and Morris Ernst in the publication of modernism. Rather, I want to insist that modernist obscenity is not only a cultural struggle (concerning say, how to represent sexuality or the freedom and value of art), but a response to the shifts in the technological infrastructure of culture.

This book brings together two traditions of thinking about modernism: a long line of thinking about obscenity as crucial to the production and reception of modernism, and a more recent tradition of seeing modernism as an expression of the changing media technologies of the early twentieth century. This latter tradition draws on the work of Friedrich Kittler, Marshall McLuhan, Lisa Gitelman, and others. Such a shift in attention is not a matter of denying the narrative of “transgressive modernism” described above. Nor need it offer a “media deterministic” account that will simply identify shifts in media technology as the “real” force behind, or explanation of, the range of cultural expressions

4 Marshik separates out Joyce as a sort of exception which proves the rule, and follows Katherine Mullin’s suggestion that obscenity debates and social purity movements may very well have prompted Joyce to make his works more combative and controversial.

now represented as modernist.5 It is however necessary to recognize the materiality of modernist literature and how this materiality shaped, and was shaped by, the discourse of obscenity in ways that are not reducible to the questions of “literary value” that were at the center of courtrooms, juries, and what Parkes calls the broader “theater of censorship” (xi). Such a recognition is not simply a matter of adding one more context to the long list of vital contexts through which we read modernism.6 Instead, a media history of modernist obscenity invites us to treat literature as a media object—one whose “medial identity,” as John Guillory notes, has long been ignored.7 Literature’s medial identity is not simply one more context that can be added to our understanding of modernism. It is not a series of events or texts that can simply be ranged alongside some “primary” texts to expose their mutual influence and relationship. The medial identity of literature is intrinsic to those very texts, “baked in” in ways that their authors and initial readers may not have recognized.

The changes in obscenity across the long twentieth century, of which this book examines only a subset, provide a way to think through the medial identity of modernist literature. Obscenity is foremost a media crime. Understanding obscenity and its relationship to works of art and literature in the modernist period requires attention to literature’s medial identity, and how this identity is a function of the broader media ecology of the period. I follow Mark Wollaeger and others in describing the relationship of interdependence among cultural media as a sort of ecology (xvii). This notion of “media ecology” insists that it is not enough to acknowledge that “literature is a medium”; one cannot simply pay more attention to the medium of literature, as if it were a matter of adding materiality on to, or back in to, the object of a more conventional close readerly attention. Nor is recalling the “medial identity” of literature simply a question of situating literature within a wider cultural context (a procedure which is now de rigueur in literary studies generally), as if questions of media were simply so many more contexts within which a work can be situated. No medium exists in a vacuum, so one must understand that the media of literature are always shaped by other, surrounding media. Moreover, media, as the infrastructure of culture, subtend works and their contexts.

5 Though I share the frustration described by John Durham Peters, that accusations of “technological determinism” often assume a “voluntarism” that does not fully acknowledge how thoroughly abstractions like literature or culture are grounded in specific technologies (89–90). Rather than whether technology determines history/culture—as if it were a question of identifying the single strongest determinant of history/culture—it would be more valuable to talk about how technology determines culture—alongside what other forces, against what countervailing trends, and subject to what resistances.

6 Without wishing to reduce the value of such work, the “Modernism and . . .” formula signals the triumph of a mode of historicist contextualism so thorough and complete, that it reminds us of the need to press our theorizations beyond a sort of flat historicism.

7 “The repression of the medial identity of literature and other ‘fine arts’ is rightly being questioned today. The aim of this questioning should be to give a better account of the relation between literature and later technical media without granting to literature the privilege of cultural seniority or to later media the palm of victorious successor” (Guillory 322n3).

They are not simply a set of events or representations contemporaneous with a work that can be placed alongside them. A new media technology does not arrive on an otherwise static historical scene to which it can be added. Media do not accumulate, but restructure how other technologies are understood. This description of the relationship among media is meant to recall Eliot’s description of the work of art: “The existing monuments form an ideal order among themselves, which is modified by the introduction of the new (the really new) work of art among them” (“Tradition” 38). A new technology shifts the existing balance of technologies and their relationships to one another.

Because, as this book will show, debates about obscenity involved reckoning with the materiality of literature—its physicality; its technologies of production and reproduction; its networks and means of circulation, distribution, and sale—modernist obscenity offers an opportunity to reflect on the medial identity of literature. What may look to be chiefly a matter of sexual liberation or aesthetic transgression, is also a moment of intense medial self-consciousness. What appears in the period, and since, as debates about “literary value” are often implicitly debates about the value of “literature” or “the literary” in relation to other media. Revealing the ways textual materiality affects determinations of literary value does not evacuate “literary value” of meaning. The goal of this argument is certainly not to uncover the hollowness or suspect politics of a discourse of literary value that achieved particular prominence in debates about modernist obscenity. Other studies have indeed shown that “literary value” often obscured other social interests, and the analysis offered here will, in part, confirm that increasingly evident claim.8 Filthy Material attempts to see the history of modernist obscenity anew, as a moment where modernist literature was particularly aware of its own medial identity.

It is no coincidence that the period of modernism’s obscenity trials also saw the continued emergence and adoption of new technologies of cultural reproduction (most dramatically in film and photography, but also in techniques of textual reproduction such as halftone printing). Increased vigilance about obscenity and pornography, evident in the activities of anti-vice societies, government censorship, and obscenity trials, resulted from new technologies which changed the audiences for works of art and literature and the patterns by which these works circulated. Raymond Williams suggests that any explanation of modernist literature and its ideology “must start from the fact that the late nineteenth century was the occasion for the greatest changes ever seen in the media of cultural production. Photography, cinema, radio, television, reproduction and recording all make their decisive advance during the period identified as Modernist, and it is in response to these that there arise what in the first instance were formed as defensive cultural groupings, rapidly if partially becoming competitively self-promoting” (33). Despite

8 Christopher Hilliard’s excellent account of the Chatterley trial, for instance, reveals that rather than inaugurating the counterculture of the 1960s, the trial largely played out in very conventional terms of social class.

Williams’s suggestion, however, the importance of modernism’s changing media landscape has not been central in accounts of modernism’s relationship to censorship.

The following chapters bring Williams’s conviction about the importance of the changing technological landscape of the twentieth century for modernist literature to bear on the historical fact of modernism’s encounter with censorship and the discourse of obscenity. Following critics like Mark Wollaeger, Julian Murphet, Mark Goble, Michael North, and others, this book insists on the importance of locating modernism within the shifting media ecology of the early twentieth century. As Murphet notes,

For what the “new media” made clear was the degree to which all media were, from this point onward, charged with the responsibility for their own propagation as channels of communication in a violently competitive market. What literary criticism needs above all to grasp, I want to suggest, is the logic whereby “literature” was obliged in the second industrial revolution to become a phatic argument on behalf of its own propagation. (9)

Nowhere is this argument more evident than in debates around obscenity. This book offers something akin to what Wollaeger has called “intermedial analysis” (xxi), or a comparative media studies approach along the lines of what Jessica Pressman and Katherine Hayles describe as “comparative textual media.” Filthy Material attempts to maintain what Pressman and Hayles call “an awareness that national, linguistic, and genre categories (typical classifications for text-based disciplines) are always already embedded in particular material and technological practices with broad cultural and social implications” (x).

While the central chapters turn to particular authors and works, the first chapter begins by offering a media history of obscenity. Since the 1868 Regina v. Hicklin decision, the prevailing definition of obscenity describes it in terms of effects on readers and viewers; obscenity is material that has “the tendency to deprave and corrupt.” As a category, it is equally applicable to codices and films, to comic books and recorded sound. This chapter surveys the history of obscenity law before the modernist period in order to recover its grounding in a media history that the Hicklin definition obscures. If only implicitly, not all media are imagined to be equally powerful bearers of obscenity. To mention only the most obvious distinction, images have typically been imagined to have a power that printed words do not. During the period of modernism’s censorship struggle (in the 1910s and 1920s), a major shift in the balance among media was occurring. The status of print itself was changing, shaped by divisions between book and periodical printing, between small, avant-garde and elite presses, and mass publishing. New technologies for the reproduction of images and photographs, likewise, shifted the ecology of such images, and their place in culture. Alongside these developments proceeded the most important shifts in the media ecology of the period—the emergence of recorded sound and moving images. Although debates about modernist obscenity in the period sometimes addressed these questions directly, they always did so implicitly. The question of obscenity, as a

question of literature’s effects on its readers, necessarily entailed imagining the uses and effects of literature in ways that implicitly located literature within a wider ecology of media objects. Yet obscenity’s definition in terms of effects has often obscured these connections.

Each subsequent chapter examines a particular nexus between modernism, obscenity, and media. The second and third chapters examine how changing technologies of textual reproduction are reflected in works of art and literature respectively. The second chapter argues that the changing meanings of the nude in art, under the pressure of cheaply reproduced photographic nudes, become a key point for the articulation of modernist aesthetics in both the paintings of Walter Sickert and Wyndham Lewis’s novel Tarr While Lewis rejects the nude outright as an appropriate subject for modern art, Sickert’s nudes seek to rehabilitate and modernize it. Both responses, however, are shaped by the collapse of traditional justifications of the nude’s role in art as a consequence of massreproduced nudes in Salon catalogues, postcards, and other forms. The third chapter continues a focus on materialities of textual reproduction, but in text rather than image, by examining the piracy of D. H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover. The obscenity of Lady Chatterley’s Lover, like that of Joyce’s Ulysses, left it unprotected by US copyright and open to piracy. Lawrence’s response to this condition, however, contrasts sharply with Joyce’s better known response. Unlike Joyce, Lawrence does not insist on his rights as owner and author of his novel. Instead, he appeals to the superior materiality of the authentic text—on the quality of its paper and printing, and contrasts it with the filthy counterfeit. Lawrence recasts a debate about intellectual property as a matter of printing technology, and in so doing leverages Lady Chatterley’s Lover’s critique of industrialization into an implicit critique of piracy.

The fourth chapter traces the tension between obscenity and the imagined social agency of the book as a medium in the late 1920s. At the chapter’s heart is the censorship of two texts by women: Radclyffe Hall’s The Well of Loneliness and Norah James’s Sleeveless Errand. While often less central to narratives of modernist subversion than the scandals surrounding Lawrence and Joyce, the suppression of James’s and Hall’s novels is, I suggest, a high-water mark of British literary censorship in the twentieth century. The chapter moves backward, beginning in the aftermath of the novels’ suppression, back through the 1929 suppression of Sleeveless Errand, and then to Hall’s 1928 novel. This backward trajectory is meant to retrace the short-lived precedent established by Hall’s novel, without which the censorship of James’s novel is unthinkable. This precedent, in turn, is best understood as a product of the interaction between postwar anxiety about women’s sexuality and Hall’s (and her publisher’s) deliberate attempt to market The Well as a “serious” novel. The chapter argues that Hall’s novel was suppressed not simply because of its account of same-sex desire between women, but because of the ways its narrative represents, and its own marketing and format mobilized, the authority of the book as a medium at a moment of heightened concern by the British state over postwar sexuality. Hall’s attempt to write a book with the power to radically reorient postwar gender and

sexual norms helps explain the otherwise puzzling censorship of James’s novel. The suppression of both novels reveals a short-lived, biopolitical mode of book censorship which sought to protect not individual readers from being “depraved and corrupted” but the British population itself.

Chapter 5 explores the relationship between orality and obscenity in the work of T. S. Eliot. Eliot is unique in this book for his active defense of obscenity as offering a limited access to a sense of cultural unity he imagines has otherwise disappeared from modern life. The chapter argues that the obscene doggerel contained in Eliot’s notebooks and shared in his letters reflects a fascination with the power, and disappearance, of practices of collective singing. This fascination with song as a medium of social collectivity is evident elsewhere in his work—both in his essays and his poetry. The racist and obscene doggerel poems in Eliot’s letters and elsewhere are not Eliot’s own creations, but pieces of obscene folk song that circulated in the period. Eliot imagines that, like music hall, bawdy folk songs provide access to a unified, shared, collective voice—a shared voice that is, however, exclusively masculine. The bawdy sexuality of the obscene folk song contrasts sharply with the failure of heterosexual romance in his poetry, just as the unified voice of collective singing is at odds with Eliot’s poetry of fragmentation. In this particular medium, obscenity offers a vision of social wholeness precisely because of its exclusion.

The final chapter finds a new perspective on the most discussed example of modernist obscenity by contrasting the cases of Joyce’s Ulysses with Joseph Strick’s 1967 film adaptation. Joyce’s work consistently notes the materiality of textual objects, and Ulysses carries this fascination further, highlighting its own materiality in a number of ways. By foregrounding its own materiality, Ulysses mitigated its obscenity in ways that recall other less-sophisticated devices of print censorship. Yet, if Joyce’s novel’s ability to foreground its printedness mitigates its obscenity, the language of that same novel could become newly obscene when transposed into another medium. This transformation is evident in the reception of Strick’s film, which faced censorship in the United Kingdom three decades after the novel had been legally published there. This asymmetry reflects the different potential each of these media—film and print—had for obscenity in 1967.

A coda examines the Obelisk and Olympia Presses as institutions of modernism which emerged in response to the censorship discussed throughout this book. In providing a home for transgressive literature in English, these presses shaped the reception of the works they published. Yet how they shaped that reception shifted, as evident in the contrast between two works of late modernism published by Obelisk and Olympia respectively: Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita. These two novels entered print through similar channels, yet they offer very different versions of the fate of modernism in the wake of modernist obscenity.

By approaching the question of modernist obscenity in various texts, and across a variety of media, Filthy Material traces the interactions between the end of obscenity for literature and modernism. The exculpatory power of literary value that emerged from debates about modernist obscenity, it suggests, is a shadow cast by the new media of the

modernist period. If “literary value” is often taken to suggest a value that a particular work may or may not have, a value that elevates a piece of writing to the status of “literature,” the media history of the twentieth century suggests that “literary value” in fact names literature’s particular identity within a regime of competing media forms. Neither modernism nor modernist obscenity are reducible to this skirmish within and between media. However, neither are they intelligible outside such a history. As I hope the chapters which follow show, a media history of the twentieth century provides particularly rich ground for understanding modernist obscenity.

1

Modernism and the Media History of Obscenity i

Would Lady Chatterley’s lover be more, or less, obscene if it were read in an uncomfortable wooden chair? This was among the perplexities facing a British court in 1960, when D. H. Lawrence’s controversial novel was on trial. Penguin Books, inspired by the 1959 reform of England’s Obscene Publications Act and the novel’s successful defense against obscenity charges in the United States, was attempting to publish Lady Chatterley’s Lover. Under the reformed Obscene Publications Act, prosecutions for obscenity were required to consider the work “as a whole.” As a logistical matter, this meant that the jurors had to be allowed to read the novel before arguments could proceed.

Yet the question arises, What precisely does it mean to read a novel? Gerald Gardiner, an attorney for Penguin, asked jurors to “read [Lady Chatterley’s Lover] as you would read an ordinary book,” but offered detailed instructions about what such ordinary reading would entail: “begin[] at the beginning and end[] at the end,” he explained. And do “not say[] to your wife or your husband when you have read it, and still less when you are half way through, ‘This is a jolly good book’ or ‘This is a perfectly awful book?’ ” (Rolph, Trial 37). The normal reading experience, in Gardiner’s account, is linear and private, and it withholds judgment until the work is complete.

This concern with how to read extended to where one read.1 Lawyers for Penguin suggested that the jurors be sent home with copies of the novel, but the prosecution asked

1 Place where a book was purchased/sold, to say nothing of the complicated question of where it was published— also entered into judgments of obscenity. Lynda Nead discusses the reputation of Holywell Street as a key source for obscene texts in chapter 3 of Victorian Babylon. In the case of the 1960 Chatterley trial, the prosecution had initially planned to institute proceedings by purchasing a copy of Lady Chatterley’s Lover in Charing Cross Road because of its association with indecent books. Rolph explains that “this much-slandered thoroughfare”

that the jurors simply read in the jury room. The judge could not allow the jurors to simply take their copies of Lawrence’s novel home—they would be, after all, handling an agent of social corruption. The suggestion of the prosecution that the jury simply read in the jury room, however, was equally unacceptable.

“The Jury rooms are jolly uncomfortable places,” [Gardiner] urged. “There are hard wooden seats, and anything more unnatural than twelve men and women sitting round a table on hard wooden chairs with a book is hard to imagine. It is to read it in wholly different circumstances from those in which an ordinary person who bought the book would read it . . .”

[Justice Byrne responded,] “And the learned Clerk for the Court says he cannot agree with the observation that conditions in the Jury room are uncomfortable.”

“I am told there are hard chairs,” persisted Mr. Gardiner. (Rolph, Trial 38)

The judge offered a compromise: “The jury were given a special room,” Rolph reports, “with deep leather armchairs, and read in comfort” (Rolph, Trial 39). This concern about furniture reflects just how uncertain the borders of the experience called reading are. Reading in a hard wooden chair might not allow a fair assessment of a novel’s obscenity because it would be reading “in wholly different circumstances from those in which an ordinary person who bought the book would read it.”

Under the pressure of an obscenity trial, silent assumptions about how media operate suddenly become apparent. Because obscenity was defined not by simple criteria against which the book could be measured but in terms of its effects on readers,2 evaluating whether the obscenity of Lawrence’s novel “tend[s] to deprave and corrupt” required re-creating a “natural” reading experience. Questions like how, where, and with whom one sat while reading suddenly required attention. It was not simply a matter of furniture; one had to take into account all the processes and infrastructures of reading. The media of reading, its technologies and its techniques,3 both in the Chatterley case and throughout was made to sound disreputable by prosecutors for “its undeserved fame as a spring-board for all the big dirtybook prosecutions” (Trial 1). Indeed, Charing Cross played a historical role in obscenity prosecutions: Edmund Curll was pilloried there (Peakman 40); in 1911, a Charing Cross bookseller was prosecuted for selling Balzac’s Droll Stories (Cox 86). The prosecution’s plan was forestalled when Penguin provided the copies directly and agreed to postpone sale of the novel until the trial was over (Rolph, Trial 1).

2 Justice Cockburn, in his decision in Regina v. Hicklin (1868), defined “obscenity” under the 1857 Obscene Publications Act. The so-called Hicklin test became the most influential test for obscenity in Anglo-American jurisprudence: “The test of obscenity is whether the tendency of the matter charged as obscenity is to deprave and corrupt those whose minds are open to such immoral influences and into whose hands a publication of this sort might fall” (Thomas 264).

3 John Durham Peters helpfully distinguishes between the materiality of “techniques” and “technologies”; both are material, but the latter are durable whereas the former may include things like know-how or the bodily techniques described by Marcel Mauss (91).

the history of obscenity, have tended to be flattened, simplified, and ignored. Gardiner’s request that one read linearly (from the beginning to the end), privately, and to withhold judgment (avoid discussing the book) in order to preserve the purity of one’s response, suggests how fragile such reading really is. The peculiar argument over where the Chatterley jurors should sit illustrates an uncertainty not simply about Lawrence’s novel or how one defines obscenity. It suggests a deeper uncertainty about what exactly reading is

The trials stage the most fundamental work of Kantian judgment—subsuming a particular work under a general category. When obscenity is imagined as a category of what is read, as it typically is, obscenity trials appear to be matters of determining whether a particular work should be subsumed under the category of “the obscene.” Yet such decisions always assume, if only implicitly, a theory of what reading is. In an obscenity trial, the jury operates as a sort of black box—books go in and judgments about obscenity come out. The question of how, precisely, those judgments are reached— which passages sparked what feelings, according to what criteria—is short-circuited. When Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously wrote of hardcore pornography, “I know it when I see it,” he was offering precisely this sort of black-box judgment based not on criteria but on his experience of a text—in that case, Louis Malle’s 1958 film The Lovers. 4 Such judgments, in fact, are aesthetic judgments—relating to aesthesis, or the senses—rather than conceptual judgments. As Kant insists, “[A] judgment of taste is not a cognitive judgment and so is not a logical judgment but an aesthetic one, by which we mean a judgment whose determining basis cannot be other than subjective” (44, original emphasis). Even while the pornographic and the obscene are clearly disqualified from the realm of the Kantian aesthetic for their interested character (the pleasure taken in such representations would be, one imagines, a matter of what Kant calls agreeableness, not disinterested aesthetic pleasure), they share with the aesthetic an apparent immediacy that bypasses cognitive criteria.5

The jurors reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover could, like Justice Stewart evaluating Malle’s The Lovers, judge its obscenity without being able to explain that judgment. This process substitutes immediate perception (seeing) for the mediated, conceptual process of judgment (knowing). Stewart’s “I know it when I see it” pithily sums up the shared logic behind judgments of both obscenity and aesthetics. Yet making sure this black box operates properly requires the careful construction of a scene of normal, and normative, reading that allows the text to be experienced by “normal readers.”6 Many of the criteria

4 Stewart’s famous declaration was anticipated by James Douglas in 1928, in the wake of the suppression of The Well of Loneliness: “It may be difficult to define obscenity. Somebody once said that he could not define an elephant, but he knew one when he saw it. The common law is based on common sense. The ordinary citizen knows an obscene book when he reads it” (Douglas, “The Well of Loneliness”).

5 Allison Pease discusses Kant extensively in her examination of modernist obscenity (22ff).

6 The imaginary figure of the homme moyen sensuel conjured by Woolsey in the trial of Ulysses where no jury was involved—provides a similar norm, without the hassle of provisioning reading chairs.

for determinations of obscenity—both explicit statutory rules (that the work be treated “as a whole”) and less formal ad hoc criteria decided in the course of the proceedings (where to read)—are not criteria about obscenity so much as guides to ensure proper reading or viewing of the work. The black box of the jury room offers a legally convenient simplification of the unruly processes of cultural meaning and textual use. Exactly what goes on in that box, or how it works, may be difficult, even impossible, to describe or define, but it is also irrelevant. The judgment itself is immediate—the jurors will know it when they read it.

Behind that immediacy, however, are the assumptions, habits, and techniques that jurors bring into the jury room with them. Although, from the perspective of the law, one simply reads (or otherwise experiences) the work, reading itself is not a static category—it has a history. As Walter Benjamin insists, “Just as the entire mode of existence of human collectives changes over long historical periods, so too do their mode of perception. The way in which human perception is organized—the medium in which it occurs—is conditioned not only by nature but by history” (Work of Art 23, original italics). Understanding this history requires us to peer into the process that obscenity law deliberately compartmentalizes, to undo the simplification of “knowing it” by seeing it and recovering instead some sense of what John Guillory has called the “repressed medial identity of literature” (322n3). Such recovery requires seeing the Chatterley jury not only as readers (however naturally they seem to be reading, however comfortable they are), but as participants in a media history that includes but is not limited to that of the book.

One can begin to approach the medial identity of literature in at least two ways. One is to note the affordances of the medium—what particular uses does a medium make available? Carol Levine, adapting the term from design theory, has described form in terms of affordances. An affordance “describe[s] potential uses or actions latent in materials and designs” (6). By looking at the affordances of particular media—such as print or the codex—one can “grasp the constraints on form that are imposed by materiality itself” (9). Levine’s importation of the language of affordances into literary criticism provides a valuable vocabulary for registering the ways in which textual materiality shapes meaning.7

The history of the senses that Benjamin describes complicates this attention to the affordances of a medium or form. Levine notes that examining affordances brings aspects of materiality that might be overlooked to our attention. “Glass affords transparency and brittleness. Steel affords strength, smoothness, hardness, and durability. Cotton affords

7 Levine’s interest in the affordances of literature recalls the long history of bibliographical criticism and book history that insists on the materiality of texts as a crucial element of their meaning. Jerome McGann has recently suggested that such concerns are best addressed through a return to an expanded “philology” (McGann, “Philology in a New Key”). Levine’s discussion of form and affordance has the benefit of making the relevance of issues of textual materiality more easily legible to a discipline that has long focused on “form” without paying a similar attention to medium. Levine may even overstress the importance of materiality when she insists that “form and materiality are inextricable, and materiality is determinant” (9).

fluffiness, but also breathable cloth when it is spun into yarn and thread. Specific designs, which organize these materials, then lay claim to their own range of affordances” (Levine 6). Levine is right that one must be resensitized to affordances, of text as much as of other materials, which have become so habitual as to be nearly invisible. Such attention reveals the material, and medial, infrastructure that undergirds particular works. Yet such materiality is not itself enough to understand their meaning or use. Those same affordances—the fluffiness of cotton, the smoothness of steel, the transparency of glass—are often afforded by other materials (e.g., wool, plastic, mica). Any particular use of a material is also a function of a context of uses that exceeds the brute materiality of a substance considered in isolation. If the affordances of such materials as cotton, steel, and glass play a crucial role in their history, so, too, do their identities as commodities. (Cotton may afford fluffiness—but not necessarily to those picking it.)

This is especially true of materials that provide the media of culture. In such an environment, not only do rag paper and wood-pulp paper both afford a surface for print, but paper itself competes with wax cylinders or encoded digital files as a medium for language. “No medium,” Marshall McLuhan insists, “has its meaning alone or in isolation from other media” (qtd. in Mangold 75). The term media ecology captures the way that media form a whole so that changes in any one medium have the potential to impact others.8 Changes in other media therefore affected the way that literature was read, valued, or judged obscene. In Friedrich Kittler’s theorization, for instance, the arrival of “technological media” broke up the monopoly of the book on the representation of what Kittler describes, with deliberate anachronism, as “serial data flows”:

As long as the book was responsible for all serial data flows, words quivered with sensuality and memory. It was the passion of all reading to hallucinate meaning between lines and letters: the visible and audible world of Romantic poetics. (10)

Technological media, such as film and the gramophone, put an end to what Kittler calls “the visible and audible world of Romantic poetics,” which the monopoly of the book had enabled. The biggest change to the literary, in this account, has nothing to do with literature itself but reflects the arrival of alien technologies of inscription.

Marshall McLuhan’s account of media change offers a similar narrative, grounded in what he calls the “sense ratios” of a culture. The human sensorium, in this account, provides a unified totality that gets extended or reshaped (McLuhan will at one point say massaged)9 by technological media. It is the human body (rather than Kittler’s more

8 I am indebted to Mark Wollaeger’s Modernism, Media, and Propaganda, where I first encountered the notion “media ecology.” Wollaeger writes, “[W]hen the problem of text and context involves a wide range of media, a thorough rethinking of contextualization also requires a fine-grained attention to the distinct signifying practices and modes of address of different media” (xxi).

9 See McLuhan, The Medium is the Massage.