https://ebookmass.com/product/enhancing-disaster-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Engaged Research for Community Resilience to Climate Change 1st Edition Shannon Van Zandt https://ebookmass.com/product/engaged-research-for-communityresilience-to-climate-change-1st-edition-shannon-van-zandt/ ebookmass.com

Social support from bonding and bridging relationships in disaster recovery: Findings from a slow-onset disaster Kien Nguyen-Trung

https://ebookmass.com/product/social-support-from-bonding-andbridging-relationships-in-disaster-recovery-findings-from-a-slowonset-disaster-kien-nguyen-trung/ ebookmass.com

From Babylon to the Silicon Valley : the origins and evolution of intellectual property : a sourcebook Nuno Pires De Carvalho

https://ebookmass.com/product/from-babylon-to-the-silicon-valley-theorigins-and-evolution-of-intellectual-property-a-sourcebook-nunopires-de-carvalho/ ebookmass.com

Enter the Multi-Vers: A Villain/Villains MMM Romance (Villainous Things Book 4) C. Rochelle

https://ebookmass.com/product/enter-the-multi-vers-a-villain-villainsmmm-romance-villainous-things-book-4-c-rochelle/ ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/original-pdf-ethical-dilemmas-anddecisions-in-criminal-justice-10th-edition/

ebookmass.com

Solomon's Treasure SOURCEBOOK Timothy Schwab

https://ebookmass.com/product/solomons-treasure-sourcebook-timothyschwab/

ebookmass.com

Agatha Christie and the Guilty Pleasure of Poison Sylvia A. Pamboukian

https://ebookmass.com/product/agatha-christie-and-the-guilty-pleasureof-poison-sylvia-a-pamboukian/

ebookmass.com

Mad for a Mate Maryjanice Davidson

https://ebookmass.com/product/mad-for-a-mate-maryjanice-davidson-2/

ebookmass.com

Learning to Live Naturally: Stoic Ethics and its Modern Significance Christopher Gill

https://ebookmass.com/product/learning-to-live-naturally-stoic-ethicsand-its-modern-significance-christopher-gill/

ebookmass.com

Meet Me at the Mountain : Whitespell Series - Book 1 Laney

https://ebookmass.com/product/meet-me-at-the-mountain-whitespellseries-book-1-laney-lockett/

ebookmass.com

ENHANCING DISASTER PREPAREDNESS FROMHUMANITARIAN ARCHITECTURETOCOMMUNITY RESILIENCE Editedby

A.NUNO MARTINS

CIAUD,ResearchCentreforArchitecture,UrbanismandDesign, FacultyofArchitecture,UniversityofLisbon,Lisbon,Portugal

MAHMOOD FAYAZI TheInstituteforDisasterManagementandReconstruction, SichuanUniversityandtheHongKongPolytechnicUniversity,Chengdu,Sichuan,China

FATEN KIKANO Facultédel’Aménagement,UniversitédeMontréal,Montreal,Quebec,Canada

LILIANE HOBEICA RISKam(ResearchgrouponEnvironmentalHazardandRiskAssessmentandManagement), CentreforGeographicalStudies,UniversityofLisbon,Lisbon,Portugal

Elsevier

Radarweg29,POBox211,1000AEAmsterdam,Netherlands

TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates

Copyright © 2021ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearance CenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher (otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthis fieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroaden ourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingand usinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationor methodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhom theyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeany liabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceor otherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthe materialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN:978-0-12-819078-4

ForinformationonallElsevierpublicationsvisitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: CandiceJanco

AcquisitionsEditor: MarisaLaFleur

EditorialProjectManager: PatGonzalez

ProductionProjectManager: BharatwajVaratharajan

CoverDesigner: MatthewLimbert

TypesetbyTNQTechnologies

Contributors KristjanaAdalgeirsdottir

AaltoUniversity,Helsinki,Finland

LaraAlshawawreh

FacultyofEngineering,MutahUniversity,Karak, Jordan

AnouckAndriessen

KULeuven,Leuven,Belgium

AdityaBarve

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology,Urban RiskLab,Cambridge,MA,UnitedStates

PabloBenetti

Post-GraduationPrograminUrbanism,Facultyof ArchitectureandUrbanism,FederalUniversityof RiodeJaneiro,RiodeJaneiro,Brazil

LisaBornstein

SchoolofUrbanPlanning,McGillUniversity, Montreal,Quebec,Canada

LizBrogden

QueenslandUniversityofTechnology,Brisbane, Queensland,Australia

GeorgiaCardosi

Facultédel’Aménagement,UniversitédeMontréal,Montreal,Quebec,Canada

SandraCarrasco

FacultyofArchitecture,Building,andPlanning, UniversityofMelbourne,Melbourne,Victoria, Australia

SolangeCarvalho

Post-GraduationPrograminUrbanism,Facultyof ArchitectureandUrbanism,FederalUniversityof RiodeJaneiro,RiodeJaneiro,Brazil

RaquelColacios

SchoolofArchitecture,UniversitatInternacional deCatalunya,Barcelona,Spain

MauroCossu

Facultédel’Aménagement,UniversitédeMontréal,Montreal,Quebec,Canada

DianeE.Davis

HarvardUniversityGraduateSchoolofDesign, Cambridge,MA,UnitedStates

MahmoodFayazi

TheInstituteforDisasterManagementand Reconstruction,SichuanUniversityandtheHong KongPolytechnicUniversity,Chengdu,Sichuan, China

EefjeHendriks

DepartmentofArchitecture,EindhovenUniversity ofTechnology,Eindhoven,TheNetherlands

AdibHobeica

Independentconsultant,Coimbra,Portugal

LilianeHobeica

RISKam(ResearchgrouponEnvironmental HazardandRiskAssessmentandManagement), CentreforGeographicalStudies,Universityof Lisbon,Lisbon,Portugal

RosemaryKennedy

SubTropicalCitiesConsultancy,Brisbane, Queensland,Australia

SusanN.Kibue

DepartmentofArchitecture,JomoKenyattaUniversityofAgricultureandTechnology,Juja,Nairobi,Kenya

FatenKikano

Facultédel’Aménagement,UniversitédeMontréal,Montreal,Quebec,Canada

ChetanKrishna

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology,Urban RiskLab,Cambridge,MA,UnitedStates

JiaLu

UniversityofToronto,CentreforLandscape Research,Toronto,Ontario,Canada

KellyLeilaniMain

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology,Urban RiskLab,Cambridge,MA,UnitedStates

A.NunoMartins

CIAUD,ResearchCentreforArchitecture, UrbanismandDesign,FacultyofArchitecture, UniversityofLisbon,Lisbon,Portugal

FadiMasoud

UniversityofToronto,CentreforLandscape Research,Toronto,Ontario,Canada

MihoMazereeuw

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology,Urban RiskLab,Cambridge,MA,UnitedStates

DavidO’Brien

FacultyofArchitecture,Building,andPlanning, UniversityofMelbourne,Melbourne,Victoria, Australia

MayankOjha

MassachusettsInstituteofTechnology,Urban RiskLab,Cambridge,MA,UnitedStates

AngelikiPaidakaki KULeuven,Leuven,Belgium

JudithI.RodríguezPortieles DepartmentofArchitecture,HarvardUniversity GraduateSchoolofDesign,Cambridge,MA, UnitedStates

HelenaSandman AaltoUniversity,Helsinki,Finland

BenjaminSchep

BuildtoImpact,Group5ConsultingEngineers B.V.,TheHague,TheNetherlands

MiiaSuomela AaltoUniversity,Helsinki,Finland

CynthiaSusilo KULeuven,Leuven,Belgium

PietervandenBroeck KULeuven,Leuven,Belgium

AlexandervanLeersum

BuildtoImpact,Group5ConsultingEngineers B.V.,TheHague,TheNetherlands

Foreword DianeE.Davis HarvardUniversityGraduateSchoolofDesign,Cambridge,MA,UnitedStates

Themultiplyingdisastersofthe21stcenturyremindusthatweliveinaworldatrisk. Vulnerabilitiesassociatedwithenvironmentaldegradation,climatechangeandextreme weatherevents,earthquakes,healthepidemics,andcivilwarsorotherviolentconflictshave destabilizedfragileecosystems,intensifiedsocialinequalities,fueledmigration,andthrown themostdisadvantagedamongusintoadownwardspiralofprecarity.TheglobalCOVID-19 pandemicismerelythelatestdisastertodrivethispointhome.The “risksociety” thatUlrich Beckwarnedaboutinthe1990sisourreality.Recurringdisasterisnownormalized.Tothe extentthatnopartoftheworldcanescapethisfuture,riskmayendupbeingthegreatglobal equalizer evenifsocialclasses,neighborhoods,cities,andnationswillcontinuetounevenly experiencetheeffectsandtraumaofanygivendisaster.Althoughthetraumaticimpactsofa singledisastereventmaybehardtopredictinform,timing,andintensity,thestarkrealityis thattherewillalwaysbeanother.Thisisexactlywhydisasterpreparednessmustbethenew modusoperandiofourtimes,andwhythisvolumearrivesattherightmoment.

Thecontributionsinthesepagescanbeseenaspartofanessentialtoolkitfortherisk society,asoriginallyconceptualizedby Beck(1992,p.21),becausetheydooffera “wayof dealingwithhazardsandinsecuritiesinducedandintroducedbymodernisationitself.” Focusingonnaturallytriggeredandhuman-madedisastercontexts,andwith anunderstandingofthespatialandsocialcomplexitiesthatmediateanygivendisaster ’ s overallimpacts,theauthorsinthiscollectivevolumereviewbothsuccessfulandfailedstrategiestorecoverfromdisastrousevents,aswellasinitiativesrelatedtodisasterriskreduction. Drawingoncasestudiesfromaroundtheworld,theyexaminetheroleofdesignthinking, communityinvolvement,governmentpolicies,andexpertinterventionsinenablingor constrainingeffectivedisasterpreparednessandresponse.Thelargeraimofanycloseanalysis ofwhatworksandwhatdoesnotistobeabletolearnfrommistakes,soastobepreparedto confrontthenextdisasterdowntheroad.Thisvolumetakesamuch-neededstepinthat direction.

Yet,becausethearrayofdisastersexaminedhereisrelativelybroad rangingfrom housingissuesinthecontextofforceddisplacement,hurricanes,andearthquakestovolcano eruptions ,noone-size-fits-allstrategyfordisasterpreparednessemergesfromthesepages. Rather,bysharingawiderangeofresponses,thisvolumechallengesthereadertothink criticallyaboutdisastermitigation,includingcertainstrategiesthathavebecomemore popularinrecentyears,aswellastheirshort-andlong-termimpacts.Amongthemostnovel contributionsinthisregardarethechaptersthatfocusondesigncompetitionsaswellason theshiftingterminologydeployedbyhumanitarian-shelterspecialists.

Onethreadthatdoesrunthroughallthechaptersisthefocusondesign,albeitdeployed onavarietyofscales.Giventheurgencyofhousinginmanydisastercontexts,the

contributingauthorspaidconsiderableattentiontoinnovationsinsheltertypologiesandthe largerhumanitariandiscourseofarchitects.Yet,becausedisastersfrequentlyrequirethe reconstructionofsocialrelationshipsthatunfoldontheneighborhoodscale,andnotmerely thebuildingscale,urban-designthinkingisnecessarytoreconfigurecommercialactivitiesor community-basedcollectivespaces.Equallyimportant,thesensitivitytobothbuildingand urban-designthinkingthatpermeatesthisvolumeisnestledwithinanappreciationfor variationsintheterritorialscalesofdisasterresponse,fromthelocaltotheregionaltothe global.

Inadditiontowhatthisvolumeoffers,itisalsoworthnotingwhatitastutelyavoids.With afocusondisasterpreparednessinitstitle,theeditorsdonotcatertotheobsessionwith resilience(althoughthewordresiliencedoesmanagetoappearinsomeofthechaptertitles andsectionheadings).Somemightseethisasanill-consideredmove,ifonlybecausethe notionofresiliencehastakenthedisaster-relatedpolicy,design,andurban-planningworlds bystorm.However,resilienceisatrickyword,readilyveeringintotheideological.Defined astheabilitytocopeandadaptsothatindividualsorcommunitiessurviveandthrive, resilienceisallabout bouncingbacktonormal afteradisaster.Someauthorsuseresilienceto refertothereestablishmentofsystemequilibriumafterashock.Othersuseitastherationale foranewandexpandingrepertoireoftools fromnoveltechnologiestorecon figured mappingandbuildingproducts thatguideustoasecureurbanandglobalfuture.Whateveritsapplication,thosewhoemphasizeresiliencehavefaiththatwithenoughattention andeffort,thefuturecanbebetter.

Yet,inadditiontoundervaluingifnotignoringthestarkrealityofacceleratingrisks,noted intheoutsetofthisessay,manyofthosewhoembracetheconceptofresiliencetendto overlooktheinter-relationalitiesofrisk.Therearetrade-offsamongformsandpatternsof resilience,notjustamongdifferentresidentsorbetweenlocationsinthesamecity,butalsoin termsofimmediateversuslong-termgainsinlivability.Indeed,copingstrategiesinsome domains(sayenvironment)mayactuallyreinforcestructuralproblemsthatcreaterisksin otherdomains(sayinequality).Urban,social,economic,andenvironmentalecologiesare connectedlocallyandacrossscalesthatlinkcitiestoregionsandbeyond.Therefore,any resiliencestrategymustbegroundedinanappreciationoftheentirelandscapeofacityand itspropertiesasasystemembeddedinalargerregionalorevenglobalecology.

Totheeditors ’ credit,itispreciselytheselatterinsightsthatthreadthroughthechaptersof thisbookandmakeitsuchawelcomeadditiontothedisasterliterature.Thesesensibilities are,forinstance,wellrepresentedinthechapterthatlaysoutaclusteringmethodologyfor land-useplanningbuiltaroundanuancedunderstandingofecology.Beyondindividual contributions,aconcernwithinter-relationalityacrossscalesisalsoseeninthevolume’ s overallorganization,whichmovesfromafocusonshelterinthe firstsectiontoanexaminationofhousing’sembeddednessincommunitycontextsinthesecondsection.Thethird sectioncarriesforwardthethreadofhousingandcommunities,butexaminesthemthrough thelensoftheglobaldynamicsthatkeepmanydisaster-responseagenciesfocusedonshelter. Thewholeexerciselandswithoneofthevolume’smostsyntheticpieces,builtarounda purposefulexplorationoflinksbetweenvulnerabilities,poverty,anddisaster.

Giventheirprofessionalbackgrounds,thisvolume’seditorsknowquitewellthatdesign thinkingcanbeatoolforunpackinginter-relationalcomplexities.Thankstotheirpractical experience,theyareawarethatadequatedisasterpreparednessisbuiltaroundanunderstandingthatanysingledesignprojectorinterventionwillhaveimplicationsfarbeyondits

targetedscope,bothinscalarandsectorialterms.Yet,toenableconstructiveactionina contextofmultiplyingandinterconnectedvulnerabilities,itisalsoimportanttoreturntothe ideaofrisk,andtodesign,build,andplanforaworldofprevalentriskasmuchasfor resilience.Wemustalwaysstaypreparedforthenextdisaster.Thiswillrequiremorethanan ongoingengagementwithnewbuildinganddesigntechniques.Disasterexpertswillalso needanewwayofthinkingabouttheconnectivityofpeople,places,andspacesthatallows communitiestorecoverfromonedisasterwhilepreparingforthenext.Doingsosuccessfully mustinvolveinterdisciplinaryinteractionanddialogamongthevariousdesign,planning, andarchitectureprofessionalsrepresentedhere,whowillinevitablyneedalliesinthesocial sciences,biological,engineering,technology,andpublic-healthprofessionstopreparefora futureofpermanentrisk.Thereisstillmuchtobedone,yetthepathwayforwardisalready beingcharted,incrementally,throughthegroundedeffortsandscholarlyreflectionscontainedinthistimelyvolume.

Reference Beck,U.(1992). Risksociety:Towardsanewmodernity.BeverlyHills,CA:Sage.

Introduction A.NunoMartins1,MahmoodFayazi2, FatenKikano3,LilianeHobeica4 1CIAUD,ResearchCentreforArchitecture,UrbanismandDesign,FacultyofArchitecture, UniversityofLisbon,Lisbon,Portugal; 2TheInstituteforDisasterManagementand Reconstruction,SichuanUniversityandtheHongKongPolytechnicUniversity,Chengdu, Sichuan,China; 3Facultédel’Aménagement,UniversitédeMontréal,Montreal,Quebec, Canada; 4RISKam(ResearchgrouponEnvironmentalHazardandRiskAssessmentand Management),CentreforGeographicalStudies,UniversityofLisbon,Lisbon,Portugal

Inmid-August2020,whenwewritethesewords,theworldisgoingthroughanunprecedentedemergencysanitarycrisis.Inabouteightmonthsafterthe firstcasewasreported inChina,thenewCoronaviruscontaminatedmorethan21millionpeople,tookmorethan 760thousandlives,andcausedthecollapseofhealthcaresystems(WHO,2020a).Ithas imposedtheclosureofbordersandthelockdownofcities,aswellashomequarantineand social-distancingpracticesonascaleneverseenbefore.Further,theCOVID-19pandemichas severelyaffectednationaleconomies,decreasedGDPs,andcausedthelossofmorethan300 millionjobsworldwide.Giventheabsenceofeffectivedrugs,epidemiologistspredictthatthe pandemicwouldcontinueforseveralmonths,ifnotyears,untilthedevelopmentand implementationofavaccine.

Likeinotherdisastersituations,thepandemichasexacerbatedregionalandinternational inequalities.Althoughthesanitarycrisishasaffectedindividualsfromallsocialgroups,the WorldHealthOrganizationconsidersthatthemostvulnerablepopulationsinurbansettings includedwellersofinformalsettlements,homelesspersons,familieslivingininadequate housingconditions,forciblydisplacedpeople,andmigrants(WHO,2020b).Atthispoint,itis possibletoanticipatetheconvergenceofthispandemicwithclimate-relatedandhumaninducedcrisesinmanygeographies,whichwilleventuallycallforadequatecrossanalyses.Whenvulnerabilityandpovertyincreasinglygohandinhand,andhazardsshift frompredictedpatterns,extremeeventsshouldbetakenasthenewnormal(UNDRR,2019). Thepresentcontextindeedhighlightsthatpreparednessshouldbedulyentrenchedinboth regulardevelopmenteffortsandpost-disastersettings,makingthepublicationofthisbook evenmorepertinent.

TogetherwiththreeotherElsevierbookseachrelatedtooneofthefourprioritiesofthe SendaiFrameworkforDisasterRiskReduction(UNISDR,2015),thispublicationisanoutput oftheeightheditionoftheInternationalConferenceonBuildingResilience,heldinLisbonin November2018.Itgathersoriginalcontributionsbyauthorsfromaroundtheglobe,mostof themwithabackgroundinarchitectureandresearch.Nearlyhalfofthechaptersfocuson humanitariandesignwhereastheothersdiscusscommunityresilience.Together,theypresent

awideunderstandingofthefourthSendaipriority: “Enhancingdisasterpreparednessfor effectiveresponseandto ‘BuildBackBetter’ inrecovery,rehabilitationandreconstruction” (UNISDR,2015,p.14).

Mostlybasedon fieldresearchconductedintheGlobalSouth,thisbookdealswithresilient responsesandbuildingcapacitiesinrelationtohazardousevents,bringingsometimely practicalexperiencesandtheoreticalinsightsinthisregard.Itisorganizedinthreeparts.PartI, devotedtohumanitarianarchitecture,putstogethersixcontributionsthataddressemergency shelteringandhousing,disasterriskreduction(DRR),andpost-disasterinterventions (rebuildingandrecovery).Thesecontributionsanalyzecommunicationandeducationalstrategieswiththeaimofconsolidatingthis fieldofknowledge.Asawhole,theydisclosethe meaninganddefinethescopeofhumanitarian-architecturepractice.Theriskandresilience pair,aswellasthenotionofcommunitydesign,permeatestheassignmentofarchitects engagedinboththedisasteranddevelopmentarenas.Thechangingroleofarchitectsand urbandesignersintimesofclimatechangeandtheincreasingnumberofvulnerablecommunitiesworldwidearetherebyabottomlinetorethinkarchitecturaleducationandtraining.

Exploringhumanitariandesignandunderstandingresilienceasasocioecologicalcapacity thatcanbefosteredthroughandwithincommunity-basedDRRprocesses,PartIIconcentratesonhumanitariandesignandresiliencebuildingasameanstoenhancecommunity preparedness.Inthisregard,architecture,urbandesign,andcommunitypreparednessare addressedtofacenotonlystandalonedisastrouseventsbutalsomoreregularurbanthreats andrisks,suchaseviction,gentrification,precarioushousing,andhealthinequality.Thefour contributionsinthispartemphasizearchitects ’ diverserolesinsupportingsuchcapacitybuildingprocessesintheGlobalSouth,ineitherDRR,post-disaster,ordevelopmentcontexts. Theseroleseventuallypromotethefullexerciseofthe “righttothecity” (Lefebvre,1968/ 1995),asstatedinthecomprehensivevisionofthe NewUrbanAgenda (UN-Habitat,2017).As such,theauthorscallforarchitectsandotherbuilt-environmentprofessionalstonotonly fostertheactiveparticipationofcommunitiesinDRRbutalsoengage,withaspiritof consensusandcompromise,in(aided)self-helpdesignandconstructionprocesses.The chaptersofPartIIIrevealthattheseprocessescanbene fitfromtakingplaceinaframework thatalsoacknowledgestheresponsibilitiesofgovernmentalactors.

PartIIIbringsnewinsightsand finenuancesforconceptssuchasinclusivegovernance andcommunityresilience.Forinstance,theauthorshereemphasizethelinkbetweenglobal dynamics,whethereconomicorpolitical,andnationalandlocalsystems,withthevulnerabilityofcommunities.Thisawarenesspositivelyaffectstheadoptedpoliciesandresponsesin themanagementofcrisesatdifferentlevelsofgovernance.Moreover,throughanumberof casestudies,thefourcontributionsinthispartrevealnovelaspectsofcommunityresilience. Strategiessuchasstakeholders’ participationandtheempowermentofcommunitiesaffected bydisasters,oftendepictedaskeyelementsforDRR,arereassessed.Themainmessagesof PartIIIimplythattheseapproachesprovetobelessbene ficialiftheyarenotconcomitant withsupervisionbystateof ficials,andguidancefromexperts.

InChapter1,LizBrogdenandRosemaryKennedydelveintotheinconsistenciesand contradictionsfoundinthehumanitarian-shelterterminology.Theauthorsconsiderthatthe plethoraofterms,someofwhichbeingappliedonlyinparticularorganizationsor geographicalcontexts,inhibitstheengagementofnewpractitionersandresearchersinthe humanitariansphere.Thus,basedonthereviewof65keydocuments,theauthorsdevelopeda comprehensiveshelter-terminologyframework.The8categoriesand25subcategoriesgather 347shelterterms,whichconcernbothmaterialandtechnical-supportelements.Sucha

frameworkisatimelycontributiontopromoteclearerunderstandingamongstakeholdersand thesteadydevelopmentofhumanitarianarchitecture,planning,andengineering.

JudithI.RodríguezPortieles’sChapter2presentsatypicalhumanitarian-architecture experience.Theauthorfocusesonthejointrecoveryeffortsofvolunteersandcommunity membersinPuertoRicointheaftermathofhurricanesIrmaandMariain2017.Sheportrays theshelteringinitiativeundertakenbytheTechoNGO,which,basedonaparticipatory approach,supportedaffectedcommunitiesby fillingthegapofadeficientgovernmental response.RodríguezPortieleshighlightstheroleplayedbylocalarchitectureprofessionalsto adaptatimbermoduletoresisthurricanesandtomeettheneedsandpreferencesofbeneficiaryfamilies.Herchapterpinpointssomebestpracticesandareasofpotentialimprovementindisasterrecovery.

EefjeHendriks,BenjaminSchep,andAlexandervanLeersum,inChapter4,alsocovera post-disasterreconstructionprocess,focusedonthe2015earthquakesinNepal.Basedon extensive fieldworkandresortingtosocialnetworkanalysis,theirstudyshedslighton favorableconditionsfortheassimilationbylocalconstructionactorsofknowledgeonstructuralresistancetoearthquakes.Comparingtwodistrictsthatreceiveddissimilarreconstruction technicalassistance,theauthorsidentifythatcommunitiesinwhichexternalengineershada majorroledisplayedlowerlevelsofunderstandingthanthoseinwhichassistanceprovision involvedastrongernetworkoflocalactors.Thishumanitarian-engineeringstudyalsoemphasizestheneedofincreasingthedialogamongthestakeholdersinreconstructionprocesses.

InChapter3,KristjanaAdalgeirsdottirhighlightslessonslearnedfromthesuccessfulshelter responsetoavolcanoeruptioninIcelandinthe1970s.Anationalbodythenimported479 prefabricatedhousesdonatedbytheNordiccountriestofulfillthetemporaryhousingneeds. Theauthor’sdetailedaccountdemonstrateshowtheresilienceofthesetemporarystructures enabledthemtoremaininresidentialuseevenaftertheiroriginalusersresettledback,in contrastwithmanyotherrecoverycasesworldwide(Lizarralde,Johnson, & Davidson,2010). Throughthenewinhabitants’ adaptations,extensions,andtechnicalupgrading,thesetransitionalhousessucceededtoultimatelybecomepermanenthomes.Thelocalmanagementofthe reliefoperations,theinvolvementofevacueesindecision-makingprocesses,andthe flexibility inherenttothestructureswereallfactorsthatcontributedtotheenduranceofthehouses.

Thethemeofcommunityinvolvementwithinhumanitarianarchitectureisalsorecurrentin Chapter5,whichcarefullydetailsanexperimentofparticipatorydesignledbyLaraAlshawawrehintheSyrianrefugeecampsofZaatariandAzrakinJordan.Theexperimentaimedat identifyingtherefugees’ shelterneedsintermsofspace,functions,andcirculation.Refugees weresolicitedtodesigntheir “ideal” sheltersbyhandling3Dmockups.Alshawawreh’ s findingsrevealdifferencesintheproposeddesignsaccordingtotheparticipants’ gender,an oftenoverlookedissueinshelter-provisionoperations.Shealsohighlightsthepositiveimpacts ofadaptedbuiltenvironmentsonrefugees’ wellbeing,especiallythoseinprotractedsituations.

InChapter6,basedontheirpedagogicalexperiencesandparticipationintheorganization ofdesigncontests,A.NunoMartins,LilianeHobeica,AdibHobeica,andRaquelColacios analyzethe2018and2019editionsofaninternationalhumanitarian-architecture competition theBuilding4HumanityDesignCompetition(B4H-DC).Toidentifydesign patternsandexploreprevioussuccessfulexperiencesinbridgingthegapbetweenarchitectural educationanddisaster-recoveryandreconstructiontraining,theauthorsalsoreviewtheDRIA (DesigningResilienceinAsia)andi-Rec(InformationandResearchforReconstruction)internationalcontests.Throughanin-depthanalysisoftheB4H-DCwinningprojects,their researchdelvesintothedesigntoolsemployedbythecompetitionparticipantstoapproachthe

involveddesignchallenges,whetherinDRRscenarios,post-disasterrebuildingandrecovery, orforcedlydisplacedpopulations’ settings.

AnouckAndriessen,AngelikiPaidakaki,CynthiaSusilo,andPietervandenBroeck addressinChapter7themultiplerolesplayedbyarchitectsinpost-disastersettingstofoster resilience,understoodasasociallytransformativecapacitythatsupportsbouncingforward intheaftermathofashock.Afterconceptualizingtheseroles,theauthorsexplorethemin threereconstructionprogramscarriedoutfollowingthe2010eruptionoftheMerapiVolcano inIndonesia.Theyidentifythegovernancestructureanditsinstitutionalandprogramming rigiditiesasthemajorconditioningfactorsforarchitects’ performanceinreconstructioninterventions.Toovercomesuchlimitations,theauthorsadvocatethatarchitectsbecomemore politicizedtobeabletoexercisethefullarrayoftheircompetencesinresilience-building processes.

Incontrast,resilienceistackledinChapter8fromaprismotherthanthatofdisastersand conflicts.HelenaSandmanandMiiaSuomelaexploredesignprobingasamethodtofoster empathicengagementbetweencommunitiesandarchitectsinprocessesofrapidand extensivespatialtransformationsintheGlobalSouth.Acknowledgingthechallengesthat architectsfacewhenworkingwithinformalneighborhoodsandthekeyrolesofcommunities’ activeparticipationinsupportingthemtowithstandshocksandalsothrive,theauthors presenttwoexamplesoftheirownpracticeinZanzibar,Tanzania.Theircarefuldescription andanalysisofthetwoexperimentsshowhowdesignstrategiescanenhancecommunities’ preparednessandenablethemtodealwiththeirdailystruggles.

InChapter9,GeorgiaCardosi,SusanKibue,andMauroCossualsodiscussthevalueof designinbuildingresilience,thistimeconsideringtheeffortsofnonprofessionalsinasetting characterizedbythelackoftenureandurbanfacilities.Theauthorstakeanoriginalstandpointtoqualifyasdesignactionsthespatialtransformationscarriedoutbythetradersofthe ToiMarket,oneofthelargestinformalmarketsinNairobi,Kenya.Theyarguethatdesign thinkingandensuingpracticeshaveallowedthetraderstoadapttoandthrivebetween disturbingevents,andillustratehowconsolidationdesignhashelpedtheseslumdwellersto dealwithrisks,whilestrengtheningtheirlivelihoodmeans.

SlumsarelikewisethefocusofChapter10,inwhichPabloBenettiandSolangeCarvalho dealwiththelimitsofgovernment-ledslum-upgradingprocessesandtheirDRRmeasures. PresentingseveralBraziliancasesofurbandesigninfavelas,theauthorsclaimthatthelackof effectivecommunityparticipationandownership,andtheshortageinadequatemaintenance bythemunicipalauthoritieshavepreventedthecollectivespacesensuingfromthese initiativesfromsustainingtheirstatusandconditions.Fortheseprojectstoeffectivelymeet DRRobjectives,theauthorsproposetheadoptionofmechanismsthatrecognizethelogicin favelas’ expansion,givingvoiceandempoweringlocalactors,andentrustingthemwiththeir roleastheactualdriversoftheurbandevelopmentintheirneighborhoods.

Participatoryapproachesdonotcompriseonlypositiveoutcomes.Drawbacksmayoccur whencommunitiesareleftoutwithoutdueinformationaboutdisasterrisksandproper designguidanceregardingincremental-housingissues,eveninformalsettlements.These shortcomingsarepresentedbyDavidO’BrienandSandraCarrascoinChapter12.TheauthorsexaminethecaseoftheVillaVerdesettlementinChile designedbyElemental whosedevelopmentcoincidedwiththe2010earthquakeandtsunamithatdevastatedthecity ofConstitucion.Withoutdenyingthebene fitsoftheempowermentofresidentswhowere

encouragedtoincrementallydeveloptheirhousesaccordingtotheirneeds,theauthorsreveal thatcertaintypesofhousingextensionsadverselyaffectedthesettlement’slivabilityand possiblyincreasedwildfirerisk.Toavoidthesedownsides,theyrecommendabalancebetweenparticipatoryapproachandcollectivegovernanceinincremental-housingstrategies.

InChapter13,KellyLeilaniMain,MihoMazereeuw,FadiMassoud,JiaLu,AdityaBarve, MayankOjha,andChetanKrishnaproposeaninnovativeresponseforadaptationtoclimate changeconsistinginbuildingresiliencethroughland-useplanningrootedinecomorphologicalattributes.Basedongeospatialand flood-riskdata,aswellasclustering analysis,theirexperimentalmethodentailsthedelineationofclimaticactionzones.Theseare thengroupedintothreecategories high-risk,low-risk,anduncertainty-orientedzones eachrequiringparticularmanagementstrategieswhosegovernanceextrapolatessimple institutionalboundaries.Theclusters’ environmentalspeci ficitiesareintendedtoguidefuture land-useplanningandurbandesign,keepinginpacewithrapidlychangingecological conditions,oneofthemostpressingdilemmasofourcentury.

InChapter11,FatenKikanoexploreshowglobalandlocaldynamicsintertwineand impactoncommunityresilience,focusingparticularlyonthecaseofrefugees.Considering theprotractedsituationofSyrianrefugeesinLebanonandbasedonextensive fieldwork,the authorportraysthelivingconditionsoftheseincomersanddiscussessomeoftherelated drawbackstothehostcountry.Kikanoclaimsthatthepolicyofexclusionadoptedbythe LebaneseGovernmentcannonethelessbealteredinsuchawayastobene fitbothrefugees andlocalcommunities.Shepresentstwokeyrecommendationsinthisregard:areorientation intheuseofhumanitarianfundsandthetemporaryregularizationofrefugees’ situation.

TheinterrelationshipbetweenlocalandglobaldynamicsisfurtherexploredbyMahmood FayaziandLisaBornsteininChapter14.Basedonthereviewofanumberofcasestudies,the authors firstdemonstratethelinkbetweenglobaltrendsandtheeconomicvulnerabilityof societies.Thentheyskillfullyidentifythecorrelationbetweenvulnerabilitytonaturalhazards andeconomicvulnerabilityandpoverty.Fromatheoreticalperspective,their findingshighlightthelinkbetweendifferentformsofvulnerability.Theirconceptualapproachcanhelp practitionersanddecision-makers,throughtheirunderstandingofthemultipleoriginsof vulnerability,indevelopingadaptedsolutionstomitigatetheimpactsofdisastersonfragile communities.

Overall,thechaptersinthisbookpinpointtomultipleinterlinkagesbetweenhumanitarian design,communityresilience,andgovernancemechanismsregardingdisasterpreparedness, post-disasterrebuilding,andurbandevelopment.Despitetheirspecificities,theyshareafew importanttake-homemessages.Oneoftheseisthatthemostsuccessfulhumanitarian-architectureandurban-designinterventionsarealwayscapacity-buildingprocessesinvolving localcommunitiesandeffectivegovernancestructures.Anotherlessonisthattheseprocesses bene fitfrombalancingurban,architectural,social,andculturaldimensions.Theserecognitionsshedlightontheprominenceofintrinsichumancomponentsindisastersandon growingvulnerabilitiestopovertyaswellastoclimatechangeinourincreasinglyunequal andunfairsocieties.Concomitantly,theselessonscallforadditionalcollectiveendeavors towardsmoreequitable,safe,resilient,andclimate-changeadaptedresponsesinourrapidly urbanizingworld.

Acknowledgments

TheeditorswouldliketothankAdibHobeicaforhisinvaluablecontributionstothereviewprocess.

References Lefebvre,H.(1995/1968).Righttothecity.InE.Kofman,&E.Lebas(Eds.), Writingsoncities (pp.61 181).London: Blackwell.

Lizarralde,G.,Johnson,C.,&Davidson,C.(Eds.).(2010). Rebuildingafterdisasters:Fromemergencytosustainability Oxford:SponPress.

UNDRR(UnitedNationsOfficeforDisasterRiskReduction).(2019). GlobalAssessmentReportonDisasterRisk Reduction.Retrievedfrom https://gar.unisdr.org

UN-Habitat.(2017). NewUrbanAgenda.Retrievedfrom http://habitat3.org

UNISDR(UnitedNationsInternationalStrategyforDisasterReduction).(2015). SendaiFrameworkforDisasterRisk Reduction2015 2030.Retrievedfrom https://www.preventionweb.net/files/43291_sendaiframeworkfordrren. pdf

WHO(WorldHealthOrganization).(2020a). Coronavirusdisease(COVID-19).Weeklyepidemiologicalupdate1 Retrievedfrom https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200817-weeklyepi-update-1.pdf?sfvrsn¼b6d49a76_4

WHO(WorldHealthOrganization).(2020b). StrengtheningpreparednessforCOVID-19incitiesandotherurbansettings: Interimguidanceforlocalauthorities.Geneva:WHO.Retrievedfrom https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/ 331896

1 Ahumanitarianshelterterminology framework LizBrogden1,RosemaryKennedy2 1QueenslandUniversityofTechnology,Brisbane,Queensland,Australia; 2SubTropicalCities Consultancy,Brisbane,Queensland,Australia OUTLINE

1.Introduction3

2.Literaturereview4

2.1Along-standingproblem7

2.2Termsdescribingphasesofashelter process7

3.Researchmethodsandmaterials8

4.Theshelterterminologyframework13

4.1Immediateshelter14

4.2Intermediateshelter14

4.3Permanentshelter15

4.4Preemptiveshelter15

4.5Nonspecificshelterterms17

4.6Shelteritems17

4.7Alternativestrategies17

4.8Multiphaseshelter18

5.Discussion19

6.Conclusions21 References21

1.Introduction

Organizationswithinanoverwhelmedhumanitariansystemareincreasinglyturningto theprivatesectorinsearchofcollaborativepartnershipstodevelopsheltersolutionsfor displacedpopulations.However,theproliferationofshelterterminologyanditsinconsistent useinthesheltersectorimpedesdevelopmentandobstructnewactors.Terminologyin fluencestheimplementationofcoherentsectorprinciplesandinconsistentuseisabarrierto

meaningfulengagementfromnewpartnersseekingtoaccessshelter-sectorknowledge. Further,misunderstoodterminologylimitsthedevelopmentofnewstrategicapproaches andinnovation. ZyckandKent(2014,p.18) highlightedthat “exclusionaryvocabularies” areevidentacrossthehumanitariansectorasanobstacletocollaboration. Bennett,Foley, andPantuliano(2016) arguedthatcertaintermsandconceptsrepresentabodyoflanguage thatisonlyavailabletoasmallhandfulofWesternuniversitieswhohavearesearchfocuson humanitarianaffairs.This “retinueofanecdotes” (Bennettetal.,2016,p.64)excludesandobscuresaccesstoknowledgeandunderstandingofhumanitarianshelterfromthosesituated beyondthesheltersectoritself.

Therearecallstomoveawayfromacentralizedandbureaucraticconceptionofthehumanitariansystemtoonethatismoreopen, flexible,andexpansive.Anopennetworkofactorscouldaccommodatenewinterpretationsofwhatconstituteshumanitarianaction,aswell astherecognitionofnewtypesofhumanitarianactors. Bennettetal.(2016) describedthehumanitariansystemasonethatlacksasingle,easilyaccessibleentrypointfornewactors.This researchexplorespatternsofshelterterminology,meaning,anduse,whichimpedeaccessto sectorknowledge.

A GoogleImages searchfor “emergencyshelter” returnsanarrayofshelterprototypes,most ofwhichareconceptualexperimentsdevelopedinresponsetoahumanitariancrisisthatis rarelydescribed.Theimagesincludeexpandingaccordion-stylestructures,cocoons, teardrops,pods,tessellatinghexagonalforms,andglowing “beaconsofhope” showninpostapocalypticlandscapes(Google,2018).Itisuncommontosee who thesesheltersareintended tohouse, where theyaretobelocated,for howlong theywillbeoccupied,orfor whattype of crisis.Well-meaningbutmisinformeddesignproposalsarerarelygroundedintherealityofa crisisortheneedsofacommunity.Further,thesheervolumeofinformationabouthumanitarianshelterthatisdispersedacrosswebsitesanddatabasesworldwideisdifficulttonavigate,creatingopportunitiesfor “duplication,disagreementandinef ficiency” (KnoxClarke & Campbell,2015,p.10).

Thisresearchexploresaparticulardomainofhumanitariandiscourseemergingfrom44 partnersthatmakeupthe GlobalShelterCluster(2018a),aswellastheSphereProject (Sphere,2018).Theaimistoprovideanoverviewofpublicationsinthe field,summarizing thearrayofshelterterminologyinuseacrossthesheltersector.Ashelterterminologyframeworkwasdevelopedusingtheseterms,facilitatingacommon,systematic,andcomprehensiveunderstandingofshelter-speci fictermsandactivities.Significantly,thisresearch providesaninterpretivetooltoaidinaccuratelyconceptualizingtheproblemoftheshelter itself.Thistoolisintendedtoenabletargetedengagementfrompractitionersandtofacilitate research,practice,andeducationinthisarea.Additionally,theshelterterminologyframeworkaimstocontributetotheprogressionofthespecialized fieldsofhumanitarianarchitecture,planning,andengineering.

2.Literaturereview Itisoftenassumedthattermsforshelterareimplicitlyunderstandabletacitknowledge. Further,publicationsrelatingtohumanitarianshelterarisefromacademicinstitutions,privateindustry,andavastnumberoforganizationsacrossthehumanitariansector.This bodyofknowledgerevealsawiderangeoftermsthatdescribeacomparablysmallvariety

ofsheltertypesandapproaches.Evenwheneffortsaremadetoexplainashelterterm,definitionsarerarelyinterpretablebeyondthecontextofaparticularprojectororganization.For example,theglossaryoftermsin Shelterafterdisaster:Strategiesfortransitionalsettlementand reconstruction providesdefinitionsforshelterandsettlements,butthesearetheonlyterms thatincludethecaveat: “Forthepurposesoftheseguidelines” (DFID & ShelterCentre, 2010,pp.305 324).

Sector-wide,acacophonyoftermscontinuestomultiplyinanever-growingnumberofreports.The2011 SphereHandbook outlinedcorehumanitarianstandardsas “apracticalexpressionofthesharedbeliefsandcommitmentsofhumanitarianagenciesandthecommon principles,rightsanddutiesgoverninghumanitarianaction” (Sphere,2011a).Yet,thepublication ’ s “Minimumstandardsinshelter,settlementsandnon-fooditems ” sectionreadsasfollowsintheintroductionchapter:

Non-displaceddisaster-affectedpopulationsshouldbeassistedonthesiteoftheiroriginalhomeswith temporaryortransitionalhouseholdshelter,orwithresourcesfortherepairorconstructionofappropriate shelter.Individualhouseholdshelterforsuchpopulationscanbetemporaryorpermanent,subjecttofactors includingtheextentoftheassistanceprovided,land-userightsorownership,theavailabilityofessential servicesandtheopportunitiesforupgradingandexpandingtheshelter[.]Whensuchdispersedsettlementis notpossible,temporarycommunalsettlementcanbeprovidedinplannedorself-settledcamps,alongwith temporaryortransitionalhouseholdshelter,orinsuitablelargepublicbuildingsusedascollectivecenters (Sphere,2011a,p.249).

Inoneparagraph,sixdifferenttermsareusedtodescribeformsofshelter(originalhome, temporaryshelter,transitionalshelter,individualhouseholdshelter,transitionalhousehold shelter,andpermanentshelter);twodescriptors(upgradableandexpandable);aswellas fivetermsforsettlement(dispersedsettlement,temporarycommunalsettlement,planned camp,self-settledcamp,andcollectivecenter).Throughoutthe SphereHandbook, additional sheltertermsareintroducedwithoutdefinition,whereastransitionalshelteristheonly typedefinedinthehandbook’stext.

Furthermore,theaccompanyingonlineglossaryforthe SphereHandbook omitsanyreferencetoshelteranditstypologiesaltogether(Sphere,2011b).Afterthisresearchcommenced, the2018versionofthe SphereHandbook wasreleased,whichhasamoreconsolidated approachinitsuseofshelterterminology.Definitionsforshelterkits,sheltertoolkits,tents, temporaryshelters,transitionalshelters,andcorehousingareprovidedinAppendix4ofthe document(Sphere,2018,pp.282 283).

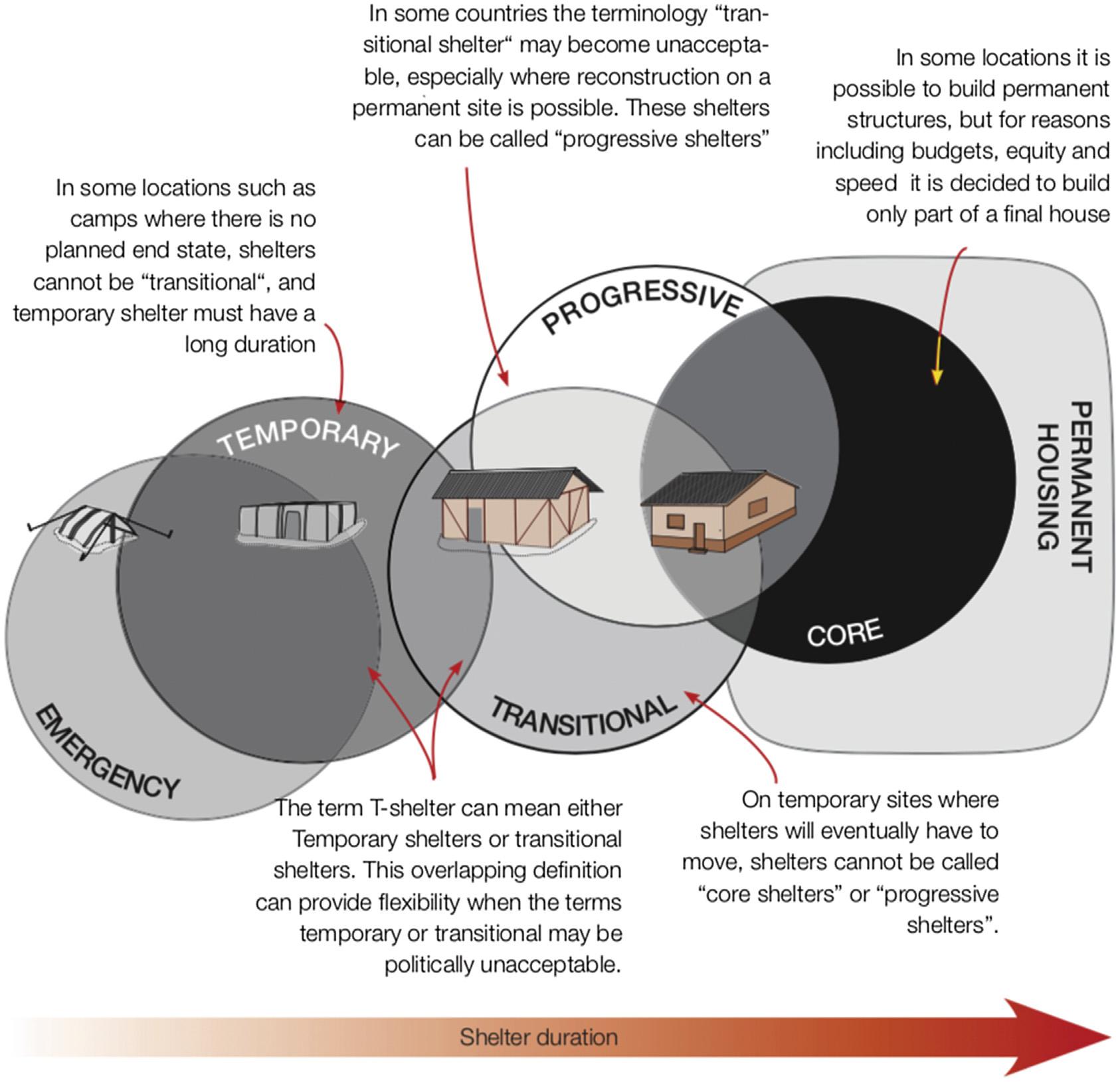

TheInternationalFederationofRedCrossandRedCrescentSocieties(IFRC),aleadpartnerintheGlobalShelterCluster,describedthe “overlappingdefinitions ” shownin Fig.1.1. Thediagramisintendedtoidentifyandstructuredifferingshelterterminologies(IFRC,2013, p.9),whilealsoillustratingtheassociatedqualitiesofeachdwellingtype(tent,module,simplehouse,establishedhouse).

AccordingtotheIFRC,sheltertermsfrequentlyrelatetoan “ approachratherthana phaseofresponse” ( IFRC,2013 ,p.8).TermsforshelterintheIFRC’ sdocumentsdescribe anoverallprocessinwhichaffectedpopulationsmaybuild,upgrade,ormaintainshelter inawaythatchangesitsoriginallyde fi nedtypology.Theterms “ progressive” and “incremental” haveemergedtocapturethisphenomenon,yettheoverlapsdepictedin Fig.1.1 arguablyincreaseconfusionratherthanprovidingclarityforthoseunfamiliarwith

FIGURE1.1 Overlappingdefinitionsforshelter. ReproducedwithpermissionfromIFRC.(2013). Post-disaster shelter:Tendesigns.Retrievedfrom http://www.sheltercasestudies.org/files/tshelter-8designs/10designs2013/2013-10-28Post-disaster-shelter-ten-designs-IFRC-lores.pdf.Geneva:IFRC,p.9.

shelter-sectoractivities.TheIFRCdoesde fi nesheltertypes,asrevealedinthereviewcarriedoutin Shelterafterdisaster,butthede finitionsprovidedarestatedonly “ forthe purposesofthisbook ” (IFRC & UN-OCHA,2015,p.8).Thisisalsothecasefortermsoutlinedinthe2018 SphereHandbook,inwhichde fi nitionscannotbeappliedcon fi dently beyondthecontextofthedocument.

Theintendedmeaningofsheltertermsmaybeapparenttothoseembeddedwithinthe sheltersector,butcaveatsaroundshelterdefinitionsrevealhowcomplexthedecipheringprocesscanbeforthosewhoarelessfamiliar.Forexample,todevelopaprojectbrief,an

architect,engineer,orplannermustfullyunderstandthenatureoftheproblem.A firmgrasp ofcrucialterminologyacrossasectororindustryisessentialtoaneffectivedesignorplanningprocessandoutcome.Further,inresearch,anunderstandingofkeytermsisalsoa fundamentalcomponentofarigorouslydesignedproject.

2.1Along-standingproblem DavisandAlexander(2016) statedthatshelterhasnotbeensummarizedadequatelyasthe effortsof Davis(1978) in Shelterafterdisaster.Overtwodecadesago, Quarantelli(1995,p.44) highlightedtheproblemof “multipleandambiguous” meaningssurroundingshelterterms, resultingin “contradictorybaggages[sic]ofconnotationsanddenotationswhichdonot allowforknowledgeandunderstandingofthephenomenainvolved.” Quarantelli(1995) observedthattermsforthesheltercamewiththeimplicitassumptionthattheywereselfexplanatory.Assuch,hesoughttodefinesheltertermsaccordingtofour “idealtypes” :emergencysheltering,temporarysheltering,temporaryhousing,andpermanenthousing.Inthe yearssince,thenumberofshelterdescriptorshascontinuedtogrow,oftenpermutated witharbitraryinterchangesbetween “shelter” and “housing.”

Almostadecadelater,duringareviewofthe SphereHumanitarianCharter,theissueofshelterterminologybecamemorewidelyrecognizedinsectorpeerreviewsandwasidentifiedas asigni ficantobstacletosectordevelopment(ShelterCentre,2017).Saunderselaborated furtherobservingthattheabsenceofacommonandcoherentlanguageforshelterandsettlementweakenedthesheltersectorandwasresultingin “majordifferencesofopinion ” (Saunders,2004,p.163).Saunders’sdiscussionextendedtoquestionthenameofthesectoritself: “Isitshelter?Isithousing?Isithumansettlements?” (Saunders,2004,p.161).

Morerecently, BoanoandHunter(2012,p.3) referredtoshelterandreconstructionpracticesinemergenciesasre flectinga “profoundlysemanticconfusion,” arguingthat,whenit comestoterms, “decipheringtheirnuancesshouldbeanecessity,astheconsequencesofconceptualconfusionmaycreateunwelcomeresults.” Theproblemofunwelcomeorinappropriateshelterhasbeenobservedbyexpertsworldwideandiswidelydocumented (Charlesworth,2014; Davis,2011; DuyneBarenstein,2011; Fitrianto,2011; Lizarralde, Johnson, & Davidson,2010; Shaw,2015). BoanoandHunter(2012) arguedthatconceptual confusionmust firstberemovedtoavoidpoorshelteroutcomesthatareinappropriateto localconditions.Theystatethatthisdecipheringismorethananacademicexercise.

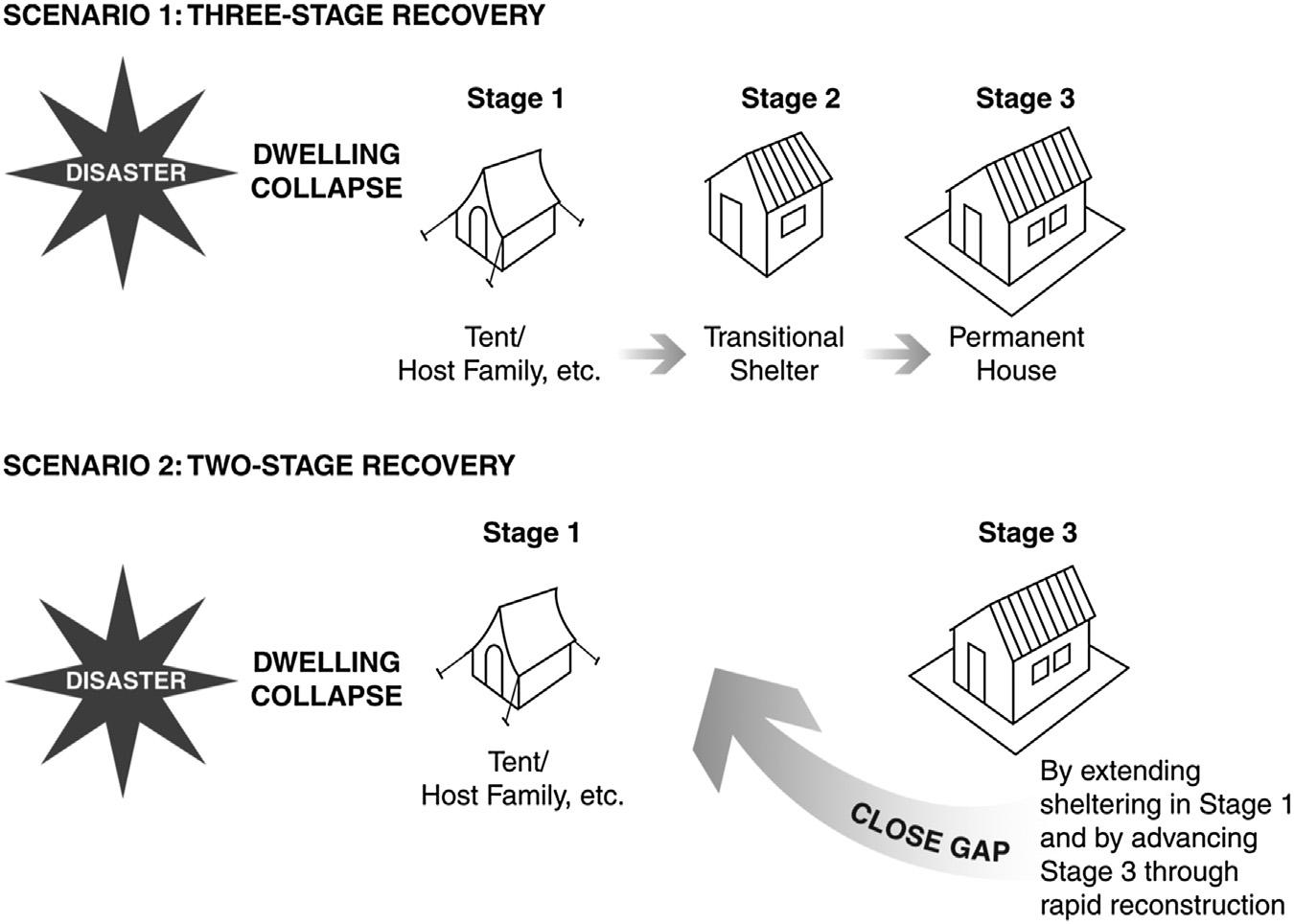

2.2Termsdescribingphasesofashelterprocess Mostcommonly,sheltertermsareintendedtobeinterpretedaspartofa “three-stage recovery ” model(Davis & Alexander,2016).Thesestagesbeginwith first-responseemergencyshelter,followedbymedium-termtemporaryortransitionalsolutions,and finally permanenthousing.Someexpertshaveadvocatedforatwo-stagemodel,removingthe needfortransitionalshelterasabridgingphasebetweenemergencyshelterandpermanent reconstruction,asseenin Fig.1.2.The figureillustratesthethree-stageversustwo-stage conceptualizationofshelterresponse,whichisgenerallyacceptedinthesheltersector.

Noteveryoneagreesonastagedapproachtoreconstruction,thoughthetermsemployed todescribealternativeapproachesremainsimilar.The ShelterCentre’s(2012) interpretation

FIGURE1.2 Three-stageandtwo-stagerecoveryscenarios. Copyright2016FromRecoveryfromdisasterbyDavid AlexanderandIanDavis.ReproducedbypermissionofTaylorandFrancisGroup,LLC,adivisionofInformaplc.

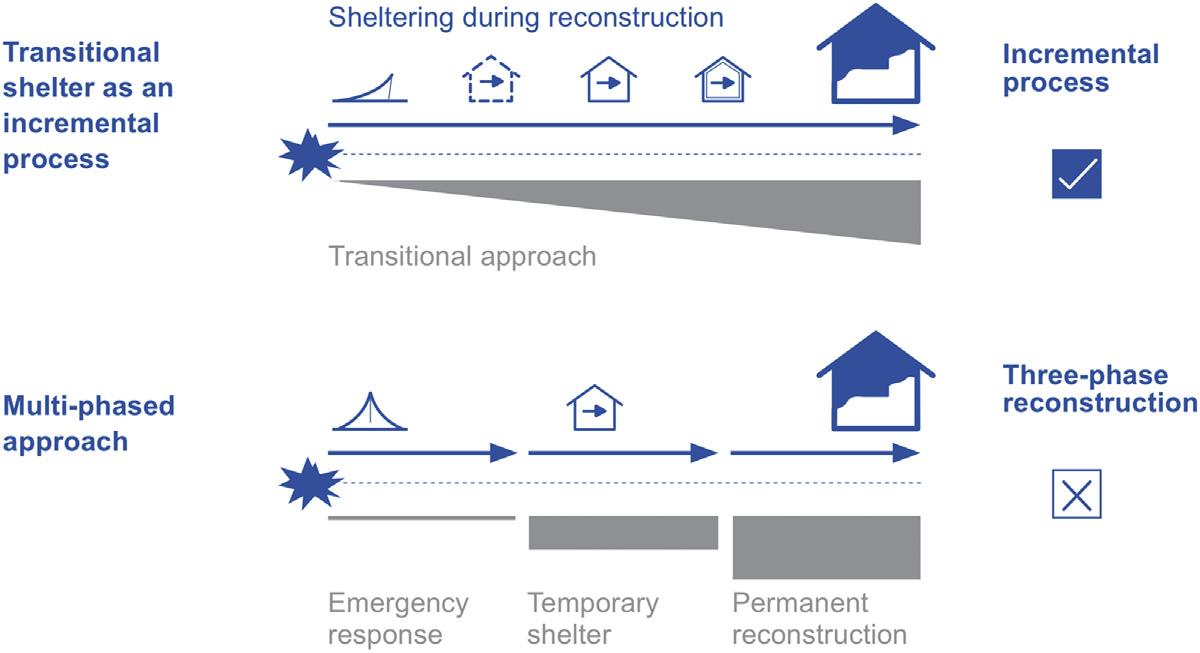

ofrecoverydistinguishesbetweenincrementalprocessesandamultiphasedapproachwhile advocatingforincrementalshelter.TheShelterCentre’sidealconceptualizationisanincrementaltransitionthroughacontinuumfromtheimmediateemergencytopermanenthousing.ThemultiphasemodelincludesthreediscretephasesasshowninDavisand Alexander’sthree-stagerecoverymodel,buttheShelterCentreusestheterm “temporary shelter” ratherthan “transitionalshelter” (see Fig.1.3).

The Transitionalshelterguidelines (ShelterCentre,2012)soughttoclarifyshelterandsettlement termswhilealsoaddressingissuesofconceptualoverlap.Thepublicationprovidedanswersto questionssuchas “areprefabricatedshelterstransitionalshelters?” and “whatisthedifference betweentransitionalshelterandcorehousing?” (ShelterCentre,2012,p.8).Despitethis,thedefinitionsprovidedinthepublicationhavenotbeenuniversallyadopted,afactevidencedbythe continuedproliferationofconflictingandcontradictorysheltertermsinthesector.

3.Researchmethodsandmaterials Thisstudyinvolvedasystematicreviewofkeypublicationsandwebsitesfromtheshelter sector.Thefocuswasspeci ficallyontheGlobalShelterCluster(GSC),comprisingorganizationsacrossallthemajorpartnersinthesector,includingUN,RedCross/RedCrescent,government,academia,andnongovernmentalentities.TheGSCwastargetedfordatacollection tofulfilltheobjectiveofgainingacomprehensivesector-wideoverviewoflanguagesurroundinghumanitarianshelterinbothpost-disasterandrefugeeresponse.

FIGURE1.3 Transitionalshelterasanincrementalprocess. ReproducedwithpermissionfromShelterCentre.(2012). Transitionalshelterguidelines.Retrievedfrom https://www.sheltercluster.org/resources/documents/transitional-shelterguidelines.Geneva:ShelterCentre,p.3.

Inall,65publicationsfromtheGSCandpartnerorganizationswereselected.Inadditionto thesesources,theresearchincludedthethreemostrecent Shelterprojects publications(Global ShelterCluster,2013, 2015, 2017),the2015versionofthe SphereHumanitarianCharter (Sphere, 2015),andthreedocumentsfromeachGSCpartnermember,asoutlinedin Table1.1.The documentsweresourcedfromwebplatforms,suchasHumanitarianResponse(UNOCHA,2017a),ReliefWeb(UN-OCHA,2017b),andPreventionWeb(UNDRR,2017),and includedreports,onlinearticles,websites,guidancematerials,andresearchpublications.

Weappliedqualitativecontentanalysisasamethodinviewofitssuitabilityfordatain whichmanifestandlatentmeaningiscontextdependent(Elo & Kyngäs,2008; Kohlbacher, 2006; Pickering,2011; Schreier,2013).Acategorizationtechniquewasusedtosummarize, explain,andstructuredata(Kohlbacher,2006). Schreier(2013) describedtheoutcomeof thismethodasa “codingframe” inwhichmaincategoriesandsubcategoriesaregenerated andstructuredandthenpopulatedwithreferencesasencounteredinthedata,effectively definingthosecategories.

Alistofsheltertermswasbuiltthroughthemeta-analysisofthethemesbothinthesector andintheliterature.Termswerethenclassifiedandmappedtoaterminologyframework andthemaincategoriesnamed.Throughthisprocess,areasofconceptualoverlaporambiguitywithinthatframeworkwereidentifiedandfurtherclassi fiedintosubcategories.Manual codingwassupportedby NVivo softwaretoef ficientlysearcheveryinstanceoftheword “shelter” anditsassociatedsynonyms:house,housing,andstructure.

Manycombinationsoftermsindicatedasimplereorderingoruseofasynonym for instanceinterchangingtheoperand “shelter,”“house,” or “structure.” Frequently,thiswas seentohavenoimpactontheintendedmeaning,forinstance,where “transitionalshelter” and “transitionalhouse” describethesameshelterstrategy.However,thesepermutations sometimesimpactedupontheintendedmeaning.Anexampleofthisis “durableshelter,” atermthatisappropriateforboth first-andsecond-stageshelters,whereas “durablehouse ” usuallyonlydescribesathird-stage(permanent)solution.Forthisreason,weoptedto includeallthetermsintheframework,despitetheapparentrepetition.

TABLE1.1 FulllistoftheGSCpartners’ publicationssourced.

GlobalShelterClusterpartner'sdocuments

ACTED2010Asheltertorecover

2010Shelterprovisionto flood-affectedpopulations

2014Annualreport

AustralianRed Cross 2011Genderandshelter

2015Annualreview

2016Emergencyshelter

BritishRedCross2011Haitioneyearon:Fromrubbletoshelter

2014Trusteesreportandaccounts

2016Whatisshelter?

CARE2008Internationalpolicybriefonshelter

2015Emergencyshelterteamannualreview

2016Post-disastershelterinIndia:Astudyofthelong-termoutcomesofpost-disaster shelterprojects

Cordaid2012Finalshelterreport

20152014annualreport

2015Shelter2Habitat:Developingresilienthabitatsafteradisaster

CRS2012LearningfromtheurbantransitionalshelterresponseinHaiti

2014Annualreport

2016Shelterandsettlements

DFID2011Humanitarianemergencyresponsereview

2015ShelterfromthestormbyDFIDUK:Exposure

2015Annualreport2014 2015

DRC20152014annualreport

2016DanishRefugeeCouncilprovidesemergencyresponseafterlargescaledestructionin Malakal,SouthSudan

2016Whatwedo

ECHO20152014annualreport

2016Emergencyshelter

2016Givingshelter

Emergency Architects Foundation

2014Annualreport2013

FoundationThisfoundationhasofficesinFranceandCanada;theirAustralianofficeisnow closed.NoEnglishpublicationswereavailablethatmettheselectioncriteria.

TABLE1.1 FulllistoftheGSCpartners’ publicationssourced. cont’d

GlobalShelterClusterpartner'sdocuments

GermanRedCross2011Bangladesh:DRRinvulnerablecommunities

2012Disasterriskreductioninsevenparticularlyvulnerablecommunities 2015Annualreview2014

Global Communities 2010CHFbuildspilottransitionalshelter 20142013annualreport

2015Betterapproachesneededforrapidrehousingafterdisasters

Habitatfor humanity 2012Disasterresponsesheltercatalog 2015Annualreport 2016Shelterreport

IFRC2012Shelterlessonslearned

2013Post-disastershelter:Tendesigns 2014Annualreport

IMPACTAworkinggroupoftheGSC.Nopublicationoutputsfound. InterAction2014Annualreport

2015Modules1 5notes,shelterandsettlementtraining 2016Shelter

IOM2013Reviewofactivitiesindisasterriskreductionandresilience 2015Oneroomshelter:Buildingbackstronger 2015Shelterhighlights

IRC2005Sheltermanual

2013Annualreport

2014GrowinghumanitariancrisisinIraqleavesthousandsinneed LuxembourgRed Cross DocumentsareinFrench.

Medair2013MedairexpandsshelterreliefprogrammeinthePhilippines 2014Annualreport 2016Shelterandinfrastructure

NRC2012Urbanshelterguidelines 2013Shelter 2014Annualreport

OFDA2012Humanitarianshelterandsettlementssectorupdate 2013Humanitarianshelterandsettlementsprinciples 2014Descriptionofhumanitarianshelterandsettlementactivities

OxfordBrookes, CENDEP

2011Gooddesigninurbanshelterafterdisaster 2013Changingapproachestopost-disastershelter 2016Shelterafterdisaster:Descriptionofresearcharea

(Continued) Ahumanitarianshelterterminologyframework

TABLE1.1 FulllistoftheGSCpartners’ publicationssourced. cont’d

GlobalShelterClusterpartner'sdocuments

ProAct2005Emergencyshelterenvironmentalchecklist

2009Environmenttrainingmodulesforemergencyshelter 2011Annualreview

ReliefInternational2014Annualreport

2016Haiti:Emergencyandtransitionalshelter

2016Pakistan:Constructionof2000temporarysheltersforIDPs

SavetheChildren UK n.d.Protectionofchildreninemergencyshelters 2014Annualreport

2015Iraq:Nowindows,noroof.Butfornow,thisishome

ShelterCentre2010Annualreport2009 2010 2012Transitionalshelterguidelines

ShelterforLife International 2006TransitionalshelterassistanceinTajikistan 2014Annualreport

2016Whatwedo:Shelter

ShelterBox2014Annualreport

2016DeadlyearthquakestrikesinEcuador 2016DesperateneedforshelterinFijiinthewakeofcycloneWinston

SwedishRedCross2012Annualreport SeepublicationsforIFRC.

UN-Habitat2005Financingurbanshelter:Globalreportonhumansettlements 2011Enablingshelterstrategies

2013Globalactivitiesreport

UNHCR2014Globalreport

2014Globalstrategyforsettlementandshelter

2016Whatwedo:Shelter

UN-OCHA2005Humanitarianresponsereview 2015Shelterafterdisaster

2016Keythingstoknowabouttheemergencysheltercluster

WorldVision International 2012Minimuminter-agencystandardsforprotectionmainstreaming 2014Annualreport

2016ShelterandwarmclothesforElNiñoaffectedpeople

Astermswereencounteredinthedata,theintendedcontextualorlatentmeaningwas interpretedpragmatically.Theshelterterminologyframework(orcodingframe)wasmaintainedasdynamicandadjustablethroughoutthecodingprocess.

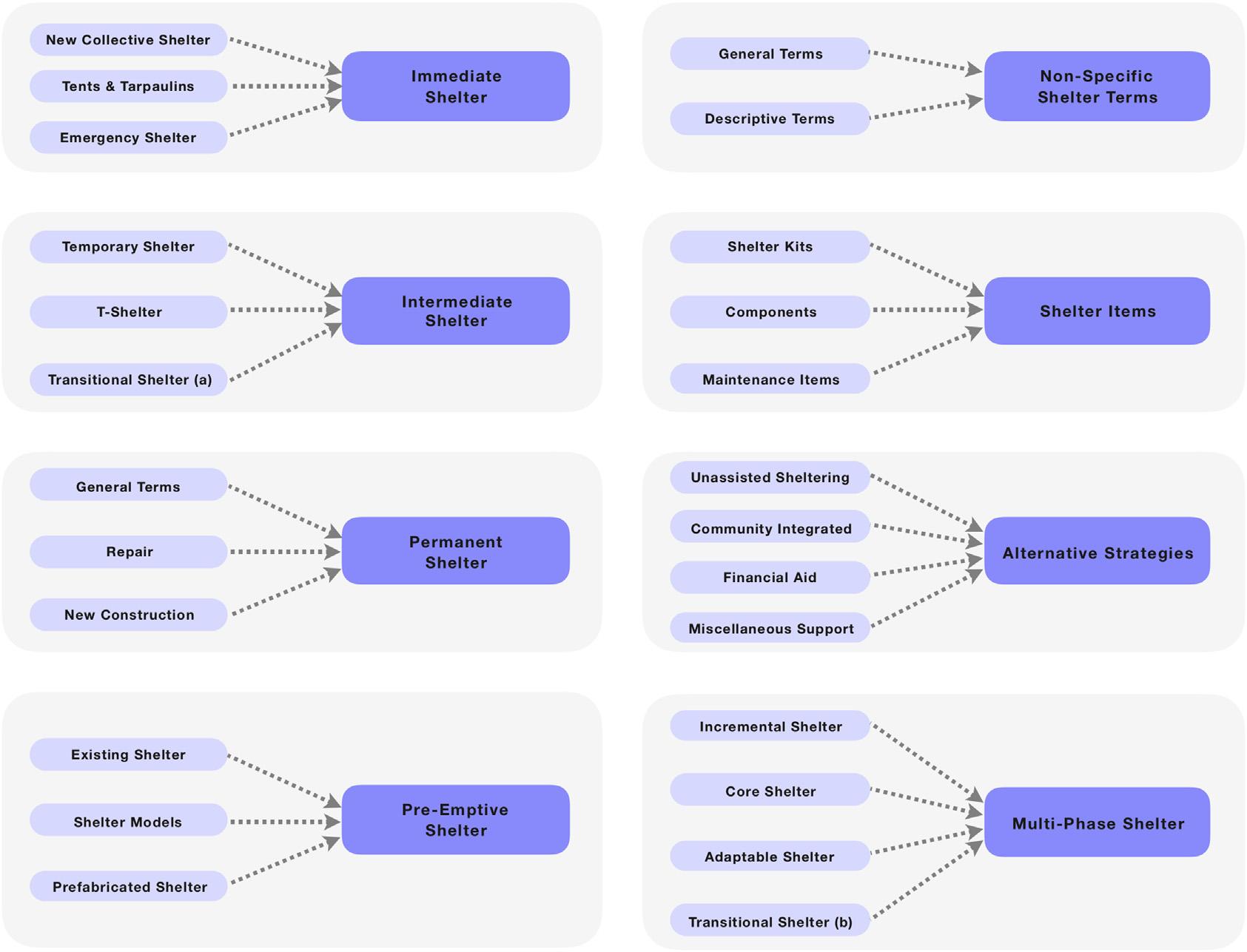

4.Theshelterterminologyframework Datasaturationwasreachedat347termsdescribingshelter.The finalframeworkconsistsof eightmaincategories:immediateshelter;intermediateshelter;permanentshelter;preemptive shelter;nonspecificshelterterms;shelteritems;alternativestrategies;andmultiphaseshelter. Eachcategoryisexplainedbytwo-to-foursubcategories,resultingin25waystodescribeshelter strategies,stages,types,andartifacts.Thefullshelterterminologyframeworkisshownin Fig.1.4 Inconstructingtheshelterterminologyframework,weidentifiedthattheterm “transitional shelter” isasignificantsourceofterminologicalconfusion.Asindicatedin Fig.1.4,two

FIGURE1.4 Theshelterterminologyframework. Credit:Theauthors.

subcategoriesoftransitionalsheltersarerepresented.The firstisinthe “second-stageshelter” category(typea),andthesecondinthe “multiphaseshelter” category(typeb).Thesereflecta distinctionthatisdiscussedextensivelyinthe Transitionalshelterguidelines (ShelterCentre, 2012)andalsotheupdatededitionof Shelterafterdisaster (IFRC & UN-OCHA,2015).Thesubcategory “transitionalshelter(a)” denotesadesignedproductintendedtoserveapurposewithina discreetsecondreconstructionphase.Thesubcategory “transitionalshelter(b)” describesanincrementalprocess.

4.1Immediateshelter Thiscategorysummarizestermsassociatedwiththe firstresponse(see Table1.2).Shelter termsincorporatedinthiscategoryrefertostrategiesinwhichminimalresponsetimeisthe prioritytoprovidelife-savingassistance.Theseshelterstrategiesareusuallyintendedonlyto serveashort-termpurpose.Thiscategoryincludesnewcollectivesheltercenters,lightweight tentsandtarpaulins,andbasicstructuralmaterialsthatarefrequentlyalsocalledasemergencyshelters.

4.2Intermediateshelter Thiscategoryincorporatessemipermanentshelterstrategiesintendedtoserveamediumtermpurpose,oranaverageofthreeto fiveyears(see Table1.3).Itincludesthesubcategories: temporaryshelter,product-focusednotionsoftransitionalshelter,andsometypesoftransportableshelter.Allofthesecanbedescribedas “T-shelters” dependingonthecontext.These “T-words ” areoftenusedinterchangeablytodescribeintermediatesheltersbyGSCpartners, evenwithinthesamedocument.

TABLE1.2 Category1 Immediateshelter.

TotalTermsSubcategoryCategory

3Collectivecenter;transitcenters;returncentersNewcollectiveshelter

13Familytent;government-suppliedtent;makeshifttent;phantom tent;plasticsheeting;sheltertent;tarp;tarpaulinsheeting; tarp-cladshelter;tentstructure;tentonconcrete;emergencytent; shelter-gradeplasticsheeting

20Emergencyshelter;earlyshelter;emergencyhousing;emergency shelter(temporary);emergencystructure;immediateshelter; initialshelter;phase-oneshelter;rapidshelter;short-term emergencyshelter;temporaryemergencyshelter;urgentshelter; emergencyfamilyshelter;recoveryshelter;emergency-shelterkit; specialemergencyshelter;earlyrecoveryshelter;immediate emergency-responseshelter;rapidlydeployableshelter; short-termshelter

Tentsandtarpaulins

Emergency shelter

1

Immediate shelter

TABLE1.3 Category2 Intermediateshelter.

TotalTermsSubcategoryCategory

9Temporaryshelter;temporaryaccommodation;temporaryhome; temporaryhouse;temporaryresettlementsite;temporarystructure; temporaryemergencyshelter;shelter(temporary); temporary-shelterkit

7Two-storeyT-shelter;ruralT-shelter;urbanT-shelter;transitionalshelter (T-shelter);T-shelterphase;transitionalshelter(T-shelter); T-shelterkit

12Transitionalhome;transitionalhouse;transitionalshelter(semipermanent); transitionalshelter(T-shelter);upgradedtransitionalshelter;urban transitionalshelter;expandabletransitionalhousing;transitionalnight shelter;semipermanenttransitionalshelter;transitional-shelterkit; transitionalindividualhouseholdshelter;transitionalhouseholdshelter

T-shelter

Temporary shelter 2 Intermediate shelter

Transitional shelter product(a)

TABLE1.4 Category3 Permanentshelter.

TotalTerms

18Permanentshelter; finalhouse;lifetimehouses;long-termhousing;long-term shelter;durablestructure;durablebuilding;integratedhousing;permanent durablehouse;permanentdurableshelter;permanenthome;permanent house;durablehome;durablehouse;permanentstructure;post-disaster house;durablesolution;long-termshelter

SubcategoryCategory

Generalterms (thirdstage)

5Repairedhousing;as-builtshelter;shelterin-kind;rehabilitatedshelters; repaireddwelling Repair

8Concretehouse;contractor-builthouses;concreteshelter;permanentcore house;newhouseconstruction;permanentreconstructionhousing; permanentreconstruction;mud-brickshelter

4.3Permanentshelter 3 Permanent shelter

New construction

Thiscategorydenotesshelterstrategies associatedwithlong-termrecovery(see Table1.4).These includedescriptivewordssuchasdurableandconcreteshelter.Threesubcategoriesareidentified withinthiscategory:generaltermsdescribinga permanentshelteroutcome,termsassociatedwith therepairofdamagedhousing,andtermsindicatingnewconstructionorreconstruction.

4.4Preemptiveshelter Thiscategoryoutlinessheltertermsdescribingstrategiesconceivedbeforeacrisisevent (see Table1.5).Subcategoriesincludeexistingshelter,sheltermodels,andprefabricatedshelter.Existingsheltersincludelocationsinthecommunityintendedasevacuationpointssuch ascycloneshelters,andalsoexistinghousing.Termsinthesheltermodel’ssubcategory