EmotionMeasurement

SecondEdition

Editedby HerbertL.Meiselman

WoodheadPublishingisanimprintofElsevier

TheOfficers ’ MessBusinessCentre,RoystonRoad,Duxford,CB224QH,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OX51GB,UnitedKingdom

Copyright 2021ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans, electronicormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorage andretrievalsystem,withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowto seekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandour arrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyright LicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions .

Thisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightby thePublisher(otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthis fieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchand experiencebroadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professional practices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgein evaluatingandusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribed herein.Inusingsuchinformationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafety andthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,or editors,assumeanyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatter ofproductsliability,negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods, products,instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN:978-0-12-821125-0

ForinformationonallWoodheadPublishingpublicationsvisitour websiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: CharlotteCockle

AcquisitionsEditor: MeganR.Ball

EditorialProjectManager: AndreaDulberger

ProductionProjectManager: SuryaNarayananJayachandran

CoverDesigner: MarkRogers

TypesetbyTNQTechnologies

Contributors

KathrynAmbroze,HCDResearch,Inc.,Flemington,NJ,UnitedStates

Gasto ´ nAres,Sensometrics&ConsumerScience,InstitutoPoloTecnolo ´ gicodePando, FacultaddeQuı´mica,UniversidaddelaRepu ´ blica,Montevideo,Uruguay

LisaFeldmanBarrett,DepartmentofPsychology,NortheasternUniversity,Boston, MA,UnitedStates;DepartmentofPsychiatry,TheAthinoulaA.MartinosCenter forBiomedicalImaging,MassachusettsGeneralHospital/HarvardMedical,Charlestown,MA,UnitedStates

LinaCa ´ rdenasBayona,DepartmentofDesign,UniversidaddeChile,Santiago,Chile

MoustafaBensafi,LyonNeuroscienceResearchCenter,CNRSUMR5292,INSERM U1028,ClaudeBernardUniversityLyon1,Lyon,France

GaryG.Berntson,DepartmentofPsychology,TheOhioStateUniversity,Columbus, OH,UnitedStates

He ´ le ` neBeuchat,UniversityofLausanne,Lausanne,Switzerland

ArmandV.Cardello,U.S.ArmyNatickSoldierCenter,Natick,MA,UnitedStates

I.Cayeux,FirmenichSA,Geneva,Switzerland

D.Cereghetti,FirmenichSA,Geneva,Switzerland

RafahChaudhry,ColumbiaUniversityVagelosCollegeofPhysiciansandSurgeons, InstituteofHumanNutrition,NewYork,NY,UnitedStates

CarolinaChaya,DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,StatisticsandBusiness Management,UniversidadPolite ´ cnicadeMadrid,Madrid,Spain

YuliaE.ChentsovaDutton,GeorgetownUniversity,Washinton,DC,UnitedStates

TobyCoates,MMRResearchWorldwide,PrestonCrowmarsh,Oxfordshire,United Kingdom

Ge ´ raldineCoppin,SwissCenterforAffectiveSciences,UniversityofGeneva, Geneva,Switzerland;FormationUniversitairea ` Distance(UniDistance),Brig, Switzerland

S.Delplanque,SwissCenterforAffectiveSciences,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva, Switzerland

PieterM.A.Desmet,DepartmentofHuman-CenteredDesign,DelftUniversityof Technology,Delft,theNetherlands

HansDeSteur,DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,GhentUniversity,Ghent, Belgium

Rene ´ A.deWijk,ConsumerScience&Health,WageningenUniversity&Research, Wageningen,theNetherlands

JohnS.A.Edwards,FoodserviceandAppliedNutritionResearchGroup,BournemouthUniversity,Poole,Dorset,England

CharisEisen,DarmstadtUniversityofAppliedSciences,Darmstadt,Germany

KellyFaig,DepartmentofPsychology,TheUniversityofChicago,Chicago,IL,United States

C.Ferdenzi,CentredeRechercheenNeurosciencesdeLyon,CNRSUMR5292, INSERMU1028,Universite ´ ClaudeBernardLyon1,CentreHospitalierLe Vinatier,BronCedex,France

StevenF.Fokkinga,EmotionStudio,Rotterdam,theNetherlands

ArnaudFournel,LyonNeuroscienceResearchCenter,CNRSUMR5292,INSERM U1028,ClaudeBernardUniversityLyon1,Lyon,France

N.Gaudreau,FirmenichSA,Geneva,Switzerland

AllanGeliebter,DepartmentofPsychiatry,IcahnSchoolofMedicineatMountSinai, Mt.SinaiMorningsideHospital,NewYork,NY,UnitedStates;Departmentof Psychology,TouroCollegeandUniversitySystem,NewYork,NY,UnitedStates

XavierGellynck,DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,GhentUniversity,Ghent, Belgium

AgnesGiboreau,InstitutPaulBocuseChateauduvivier,EcullyCedex,France

LorisGrandjean,UniversityofLausanne,Lausanne,Switzerland

DanielGru ¨ hn,DepartmentofPsychology,NorthCarolinaStateUniversity,Raleigh, NC,UnitedStates

HeatherJ.Hartwell,FoodserviceandAppliedNutritionResearchGroup,BournemouthUniversity,Poole,Dorset,England

HyisungC.Hwang,SanFranciscoStateUniversity,SanFrancisco,CA,UnitedStates; Humintell,ElCerrito,CA,UnitedStates

KeikoIshii,GraduateSchoolofInformatics,NagoyaUniversity,Nagoya,Japan

Rube ´ nJacob-Dazarola,SchoolofDesign,UniversidaddeChile,Santiago,Chile

SaraR.Jaeger,TheNewZealandInstituteforPlant&FoodResearchLimited, Auckland,NewZealand

GerryJager,DivisionofHumanNutritionandHealth,WageningenUniversityand Research,Wageningen,TheNetherlands

HarryR.Kissileff,Diabetes,Obesity,andMetabolismInstitute,IcahnSchoolof Medicine,MountSinaiMorningsideHospital,NewYork,NY,UnitedStates

RebeccaR.Klatzkin,DepartmentofPsychology,RhodesCollege,Memphis,TN, UnitedStates

KellyA.Knowles,DepartmentofPsychology,VanderbiltUniversity,Nashville,TN, UnitedStates

UeliKramer,UniversityofLausanne,Lausanne,Switzerland;UniversityofWindsor, Windsor,ON,Canada

StefanieKremer,WageningenURFood&BiobasedResearch,ConsumerScience& Health,Wageningen,theNetherlands

SamuelH.Lyons,UniversityofPennsylvania,Philadelphia,PA,UnitedStates

MarylouMantel,LyonNeuroscienceResearchCenter,CNRSUMR5292,INSERM U1028,ClaudeBernardUniversityLyon1,Lyon,France

DavidMatsumoto,SanFranciscoStateUniversity,SanFrancisco,CA,UnitedStates; Humintell,ElCerrito,CA,UnitedStates

SaifM.Mohammad,NationalResearchCouncilCanada,Ottawa,ON,Canada

ElizabethNecka,DepartmentofPsychology,TheUniversityofChicago,Chicago,IL, UnitedStates

MichelleMurphyNiedziela,HCDResearch,Inc.,Flemington,NJ,UnitedStates

LaurenceJ.Nolan,DepartmentofPsychology,WagnerCollege,StatenIsland,NY, UnitedStates

LucasP.J.J.Noldus,DepartmentofBiophysics,DondersInstituteforBrain,Cognition &Behavior,RadboudUniversity,Nijmegen,theNetherlands

GregJ.Norman,DepartmentofPsychology,TheUniversityofChicago,Chicago,IL, UnitedStates

AnnaOgarkova,SwissCentreforAffectiveSciences,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva, Switzerland

BunmiO.Olatunji,DepartmentofPsychology,VanderbiltUniversity,Nashville,TN, UnitedStates

JuanCarlosOrtı´zNicola ´ s,InstituteofArchitecture,DesignandArt,Autonomous UniversityofCiudadJuarez,CiudadJuarez,CH,Me ´ xico

DegerOzkaramanli,FacultyofEngineeringTechnology,UniversityofTwente, Twente,theNetherlands

EvaR.Pool,DepartmentofPsychology,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva,Switzerland; SwissCentreforAffectiveSciences,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva,Switzerland

C.Porcherot,FirmenichSA,Geneva,Switzerland

CatherineRouby,LyonNeuroscienceResearchCenter,CNRSUMR5292,INSERM U1028,ClaudeBernardUniversityLyon1,Lyon,France

DavidSander,SwissCenterforAffectiveSciences,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva, Switzerland;LaboratoryfortheStudyofEmotionElicitationandExpression, DepartmentofPsychology,FPSE,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva,Switzerland

JoachimJ.Schouteten,DepartmentofAgriculturalEconomics,GhentUniversity, Ghent,Belgium

NeikaSharifian,DepartmentofPsychology,NorthCarolinaStateUniversity,Raleigh, NC,UnitedStates

SaraSpinelli,UniversityofFlorence,Florence,Italy

xxiv Contributors

DavidM.H.Thomson,MMRResearchWorldwide,PrestonCrowmarsh,Oxfordshire, UnitedKingdom

LouisedenUijl,WageningenURFood&BiobasedResearch,ConsumerScience& Health,Wageningen,theNetherlands

HannelizevanZyl,HEINEKENGlobalInnovationandResearch,Zoeterwoude,the Netherlands

RuutVeenhoven,ErasmusUniversityRotterdam,Rotterdam,TheNetherlands,ErasmusHappinessEconomicsResearchOrganizationandNorth-WestUniversity SouthAfrica,OpentiaResearchProgram

MeganViar-Paxton,DepartmentofPsychology,VanderbiltUniversity,Nashville,TN, UnitedStates

LeticiaVidal,Sensometrics&ConsumerScience,InstitutoPoloTecnolo ´ gicode Pando,FacultaddeQuı´mica,UniversidaddelaRepu ´ blica,Montevideo,Uruguay

ChristianaWestlin,DepartmentofPsychology,NortheasternUniversity,Boston,MA, UnitedStates

JungKyoonYoon,CollegeofHumanEcology,CornellUniversity,NewYork,NY, UnitedStates

Preface

Thestudyofemotionshasbeenalargeandcomplexfieldforalongtime,andthe fieldkeepsgettinglargerandmorecomplex.Firstandmostbasic,whatare emotions,andwhatarethelimitsonbeingincludedasanemotion?Questionson thebestway(s)tomeasureemotionspersistandevengetmorecomplicated: shouldwemeasurethemwithself-reportquestionnaires(withwordsoremojior interviews),behaviorally(facial,bodymovements)orphysiologically?Should westudymainlynegativeemotionsasisdoneclinically,althoughthisis beginningtochange,orshouldwestudymainlypositiveemotionsasisdone commercially?

Thegoalof EmotionMeasurement,firstedition(2016),wastocombinethe academicstudyofemotionswiththeappliedandcommercialstudyofemotions, sincetheyexistedinsomewhatisolatedstates.Thechallengefor Emotion Measurement,secondedition,isthatthesituationhasnotchangeddramatically. TheSocietyforAffectiveSciencehasaspecialpreconferencesessiononpositive emotionsbecausenegativeemotionsdominatetheregularprogram.Butthereare alsosignsofchange,aswhenaleadingconsumerresearchconferencehadakey academicemotionresearchertalkaboutemotiontoover1000conferencedelegates.Thatsparkedtheappliedconsumerresearcherstolookmorecloselyinto whatdefinesemotionsandhowemotionsshouldbeapproachedinapplied research.Eachside,basicandapplied,hassomethingofvaluefortheotherside, anditishopedthatthisbookwillcontributetothedialoguebetweenbasicand appliedresearchonemotion.

Intheprefacetothefirsteditionof EmotionMeasurement,InotedthatIwas warnedthatthetopicwastoobroad,butthebookprovedthatwecancombinea lotofdiverseelementsofemotionmeasurementintoonebook.Thesecond editionof EmotionMeasurement increasesthatvarietyanddiversitywithmore chaptersonmoretopics.Somenewacademicresearchtopics,questionnaire methodsofemotionmeasurement,andphysiologicalmethodsandapplications havebeenaddedand,mostimportantly,agrowingperspectiveonhowself-report methodsandphysiologicalmethodsshouldworktogetherhasbeenincluded.

EmotionMeasurement,secondedition,continueswiththetraditionofthe firsteditioninpresentingaverybroadvarietyofpointsofviewandmethods.We arenottryingtopresentasinglepointofview,andhaveencouragedtheauthors topresenttheirownmethodsandpointsofview.Ifyouarelookingforcomplete agreementontheimportantquestionsofemotionmeasurement,youwillnotfind

thathere.Butyouwillfindtheleadingexpertsinemotionmeasurementpresentingtheirpointsofviewandtheirmethods.Insomecases,authorsand chaptersagree,andinothercasestheydisagree.Butthatistheideaof Emotion Measurement tosharethatrangeofopinionsandmethodswiththereader.

WoodheadPublishing(animprintofElsevier)continuestosupportthisbook, anditwasWoodheadwhosuggestedasecondedition.SpecificallyIwishto thankMeganBall(SeniorAcquisitionsEditor,FoodScience)forenthusiasmand support,andAndreaDulberger(EditorialProjectManager)fordealingwiththe myriaddetailsofproducingalargebookwithmultipleauthors.Ialsothankthe authorsforrespondingpositivelytothesecondeditionofthisbookandproviding updatedchaptersornewchapters.Andpersonally,Ithankmywife,Deborah PrescottMeiselman,forhersupportduringthebookeditingprocess.

Ihopeyouenjoythissecondeditionof EmotionMeasurement.

HerbertL.Meiselman

Theoreticalapproachesto emotionanditsmeasurement

Ge´raldineCoppina, b,DavidSandera, c aSwissCenterforAffectiveSciences,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva,Switzerland; bFormation Universitairea` Distance(UniDistance),Brig,Switzerland; cLaboratoryfortheStudyofEmotion ElicitationandExpression,DepartmentofPsychology,FPSE,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva, Switzerland

1.2.2.2Isemotionanactiontendency?

1.2.2.3Isemotiona

Wehopethischapterwillprovideanoverviewoncurrenttheoreticalapproachesto emotionanditsmeasurement,withoutneglectingtheirhistoricalroots.Simultaneously, ourgoalistobringthemajorconceptualfoundationsfortheworkdescribedinthe followingchapters.Wehavegroupedtheoriesofemotioninthreefamilies,ataxonomy groundedinhistoricalandconceptualreasonsthatishelpfultograsptheoretical developmentsinaffectivesciences,andtosystematicallypresentkeyconceptsand theoriesinthefield.Suchaclassificationprovidesthereaderswithanorganized descriptionoftheoreticalrootsandmajorconceptualdistinctionsinaffectivesciences.

1.1Introduction

Thetopicofemotionrarelyleavesindividualsunemotional.Philosophersin theWesthavediscusseditasearlyasSocrates’times(470-399BC),andmany contemporaryresearchtraditionsfindtheirrootsinphilosophicalapproaches developedoverthecenturies(see Deonna&Teroni,2012).Duringthe20th century,advancesinexperimentalpsychologyandneuroscienceallowedfor theempiricaltestingofcriticalideas,andthedevelopmentofnewmodelsof emotion.Sincethe1980s,therehasbeenanexplosionofthescientificstudyof emotion,andthetopichassetoffseveralvibrantdebates.Experimentaldatais accumulatingshowingthatemotioncanimpactmostdomainsofanimaland humancognitionandbehavior:emotionguidesperception,attention,learning, memory,decision-makingandaction(see Brosch,Scherer,Grandjean,& Sander,2013).Researchhasledtomodelsdescribinghowemotioniselicited andhowtheemotionalresponseisorganized(see Sander,2013).Researchers haveproposedconceptualclarificationsandtheoreticaldevelopments regardingemotion(see Scarantino,inpress),andvariousmethodological developmentshaveallowedadvancesinthemeasurementofemotion,andof itsconstitutiveprocesses(e.g., Coan&Allen,2007; Meiselman,2016, in press).“Affectivesciences”emergedasanewintegrativeandinterdisciplinary domaininvestigatingemotionandotheraffectivephenomena(see Davidson, Scherer,&Goldsmith2003; Gross,Levenson,&Mendes,2020; Sander& Scherer,2009)asaresultofmanydisciplinestakingan“affectiveturn”during thelastfewdecades.Thisdomainincludesdisciplinessuchaspsychology, neuroscience,philosophy,economics,literature,history,sociology,ethology, andcomputersciences,whichtakentogetheraimatunderstanding,measuring, modeling,andpredictingaffectivereactions.

Inthischapter,wewillstartbydiscussingsomeofthedifferentdefinitions ofemotionandpresentwhatcanbeconsideredasaconsensualview,namely thatemotionisbestdefinedasamulti-componentconcept.Wewillthen describeeachofthesecomponents,thekeydifferentindicatorsusedtomeasurethem,andtheirrelationtothemajorcurrenttheoreticalapproachesof emotion.Finally,wewillsummarizethekeypointswehavediscussedand raisesomequestionsforfuturework.Adiscussionofaffectiveneuroscience, andhowknowledgeabouttheemotionalbrainhasimpactedmodelsof emotionisbeyondthescopeofthischapter,andhasbeenpresentedand discussedelsewhereindetail(see Armony&Vuilleumier,2013; Sander, 2013).Forthepurposeofthepresentchapter,letusmentionthatresearchon theemotionalbrainwenthandinhandwiththedevelopmentoftheconceptual approachestoemotion.Thus,thethreetheoriesofemotiondiscussedinthe currentchapterhaveallbeenlinkedtotheemotionalbrain(Adolphs& Anderson,2018; Kragel,Sander,&Labar,inpress; Hamman,2012; Sander, 2013; Sander,Grandjean,&Scherer,2018; Sander,Grafman,&Zalla,2003; Skerry&Saxe,2015),withparticularfocusontheamygdala,theinsula,the

orbitofrontalcortex,somatosensorycortices,basalganglia,butalsothe dorsolateralprefrontalcortex,andthesuperiortemporalsulcus.Although someattemptstolinkdiscreteemotionswithdedicatedbrainstructures(e.g., fearwiththeamygdala,anddisgustwiththeinsula)havebeenmade,current approachestendtofocusonhowbrainnetworksmayunderliedimensionsor components(e.g., Brosch&Sander,2013; Namburietal.,2015; Pessoa,2018; Pessoa&Adolphs,2010; Sander,Grandjean,&Scherer,2018).

Wehopethischapterwillprovideanoverviewoncurrenttheoretical approachestoemotionanditsmeasurement,withoutneglectingtheirhistorical roots.Simultaneously,ourgoalistobringthemajorconceptualfoundations fortheworkdescribedinthefollowingchapters.Wehavegroupedtheoriesof emotioninthreefamilies,ataxonomygroundedinhistoricalandconceptual reasonsthatishelpfultograsptheoreticaldevelopmentsinaffectivesciences, andtosystematicallypresentkeyconceptsandtheoriesinthefield.Sucha classificationprovidesthereaderswithanorganizeddescriptionoftheoretical rootsandmajorconceptualdistinctionsinaffectivesciences.Boundaries betweencategoriesoftheoriesarealwaysfuzzy,butitdoesnotmeanthatsuch categoriesdonotexistandarenotuseful.

1.2Whatisanemotion?

1.2.1Definitions

1.2.1.1Thecomplexityofdefiningemotion

FehrandRussell(1984) appropriatelystatedthat“everyoneknowswhatan emotionis,untilaskedtogiveadefinition.Then,itseems,nooneknows” (p.464).Inoneofthemostfamousarticlesonemotion, James(1884) raised thequestionofwhatanemotionis,highlightingthatmanydefinitionshave beensuggestedbeforeheproposedhistheory.Butthevarietyofapproachesof emotiondidnotstopwithJames’seminalpaper:emotionhasbeendefinedin variouswayssincethebeginningofthe20thcenturyaswell.Thenumerous characterizationsofemotionvaryasafunctionofmanyfactors,suchasthe historicalandculturalcontexts,aswellasthedifferenttheoreticalapproaches theyareembeddedin.

Toexplicitlyaddressthedefinitionalquestion, KleinginnaandKleinginna (1981) havereviewedalmostahundreddefinitionsofemotion.Theyfound thatdefinitionshaveemphasizeddifferentaspectsofit,aspectsthatcanbe classifiedintoelevencategories.Forinstance,whilesomedefinitionsof emotionhavefocusedonthephysiologicalaspectsofemotion,othershave insistedonexpressivebehaviors.Somehavefocusedonemotionasa disturbingfactor(e.g.,relatedtopsychopathology)whileothershaverather focusedonthefunctionsofemotion(e.g.,relatedtoevolutionaryadvantages). Thedifficultyofdefiningemotion,anddelineatingitsboundariestoother affectivephenomena(e.g.,mood,preference,attitude,passion,affect)isnot

theonlychallenge.Itisalsonotstraightforwardtoclassifydifferentemotions (asnegative,aspositive,asprimary,asmoral,associal,asaesthetic,as epistemic,asself-reflectiveetc.;foradiscussionontheclassificationissue,see Sander,2013).Theseconceptualproblemsarealsoevidentinappliedfields (e.g., Meiselman,2015).Theissueofdefiningemotionisstillacontemporary one(Russell,2012),andstronglyimpactscurrentmodelsofemotion(Sander, 2013; Scarantino,inpress).

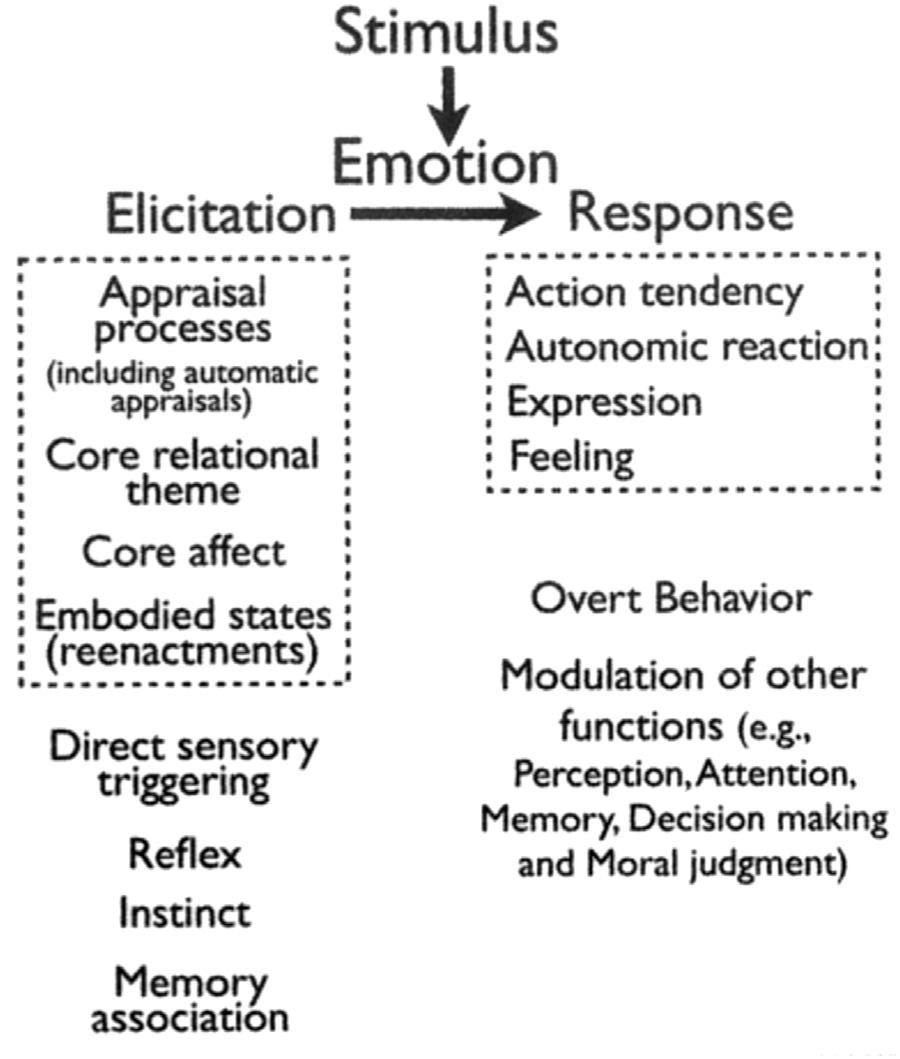

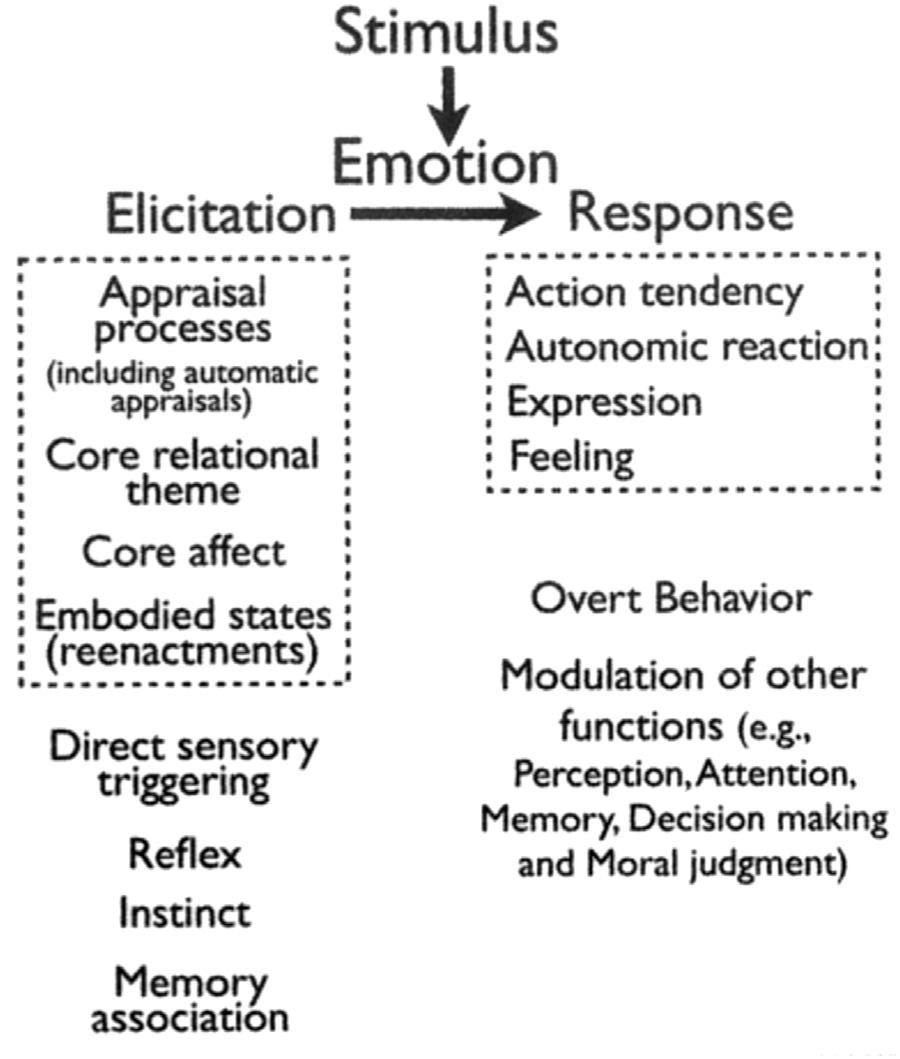

Aconsensualdefinitionthatemergesfromananalysisoftheliteratureis thefollowingone:anemotionisan“event-focused,two-step,fastprocess consistingof(1)relevance-basedemotionelicitationmechanismsthat(2) shapeamultipleemotionalresponse(i.e.,actiontendency,automaticreaction, expression,andfeeling”(Sander,2013,p.23).Themechanismsinvolvedin emotionelicitationandtheireffectsonemotionalresponsearerepresented Fig.1.1.Wewillconsequentlyrestrictthetermemotiontobriefepisodes

FIG.1.1 Mechanismsinvolvedinemotionelicitationandtheireffectsonemotionalresponse. Dashedlines aroundsomeofthemechanismsrepresenttheassumptionmadeinsometheoriesof emotionthatthesemechanismsarepartoftheemotionprocess.Appraisalprocessesmainlyrefer tothesubjectiveevaluationoftheevent’significance.Corerelationalthemesarecategoriesof emotion-elicitingappraisals.Coreaffectis“aneurophysiologicalstateconsciouslyaccessibleasa simpleprimitivenonreflectivefeeling”(Russell&Feldman-Barrett,2009).Embodiedstates(reenactments)refertothereactivationofvariousbodily-relatedsystems,inwhichhigh-level cognitionisgrounded.Appraisalprocesses,corerelationalthemes,coreaffectandembodied statesarediscussedinmoredetailelsewhere(Sander,2013,pp.18 19).

duringwhichseveralcomponents(i.e., actiontendency,automaticreaction, expression,andfeeling)aresynchronizedbytheevaluationofaneventthatis appraisedasrelevantwithrespecttomajorconcerns(suchasneeds,goalsand/ orvalues)ofanindividual.Notethatthisdefinitionemphasizesthefactthatin additiontoanemotionalresponse,thereareelicitingmechanisms,whichare consideredasbeingpartofemotionandnotjustantecedenttoit.Another importantaspectofthisdefinitionisthefactthatsomeemotionalprocesses (e.g.,aparticularappraisalorafacialexpression)canbeinvestigatedassuch, typicallyusinglaboratoryexperiments,evenwhenno“fullblownemotion”is elicitedinthelaboratory.Keyissues,suchaswhetheranemotioncanbe unconscious,canbestudiedbyaskingforinstancewhethersomeemotion components(e.g.,appraisal)canfunctionatanunconsciouslevel.Thus,there arewaystoprovideworkingdefinitionsofemotionasacomplexphenomenon.

1.2.1.2Themulti-componentcharacterofemotion

Thethreemajortheoriesofemotion basicemotion,dimensionaland appraisaltheories alldescribeemotionasaphenomenonwithmultiple components(thisisnotanewidea;seee.g., Irons,1897).Importantly,this multi-componentviewistypicalofappraisaltheories(seeabove)butisnot specifictothisfamilyoftheories.Forinstance,asmajorrepresentativesof basicemotiontheories, MatsumotoandEkman(2009,pp.69) describedthe emotionprocessasfollows:“Iftheperceivedschemasdonotmatchthosein theemotionschemadatabase,noemotioniselicitedandtheindividual continuestoscantheenvironment.Amatch,however,initiatesagroupof responses,includingexpressivebehavior,physiology,cognitions,andsubjectiveexperience.Thegroupofresponsesiscoordinated,integrated,and organized,andconstituteswhatisknownasanemotion.Emotionalresponses, inturn,affectthescanningcomponentofthesystem.Inourview,theterm ‘emotion’isametaphorthatreferstothisgroupofcoordinatedresponses.”As arepresentativeofanotherkeytraditionisemotionresearch psychological constructivism Russell(2009,p.1259)alsoemphasizedtheconceptof “components”whendescribingtheemotionprocess:“Psychological constructionisnotoneprocessbutanumbrellatermforthevariousprocesses thatproduce:(a)aparticularemotionalepisode’s‘components’(suchas facialmovement,vocaltone,peripheralnervoussystemchange,appraisal, attribution,behavior,subjectiveexperience,andemotionregulation); (b)associationsamongthecomponents;and(c)thecategorizationofthe patternofcomponentsasaspecificemotion.”

Tosummarize,this“multi-component”perspectivetypicallycharacterizes emotionintermsoffivecomponents:(1)expression,(2)actiontendency,(3) bodilyreaction,(4)feeling,and(5)appraisal.Thismultiplecomponentsapproach hasprovenusefulnotonlytoconceptualize(Sander,Grandjean,&Scherer,2005) butalsotomeasure(Mauss&Robinson,2009)emotions.Wewilldefineanddetail eachofthesecomponentsinthefollowingsectionsofthechapter.

Beforedoingso,letusconsiderthatbesidesthismulti-component character,emotionsaretypicallyconsideredwithrespecttothreeadditional criteria.First,emotionsaretwo-stepprocesseswhereemotionelicitation mechanismsgenerateemotionalresponses.Second,“relevant”or“significant” objects,whichrefertobothevolutionaryandidiosyncraticconcernsor situations,arerequiredforemotionstooccur.Third,emotiondurationisbrief andemotionhasaquickonset(see Chapter13 ofthisvolume).Morespecifically,andalthoughrarelystudied(see Nu ¨ bold,Kuppens,&Verduyn,2020; Verduyn,VanMechelen,&Tuerlinckx,2011),emotiondurationisthoughtto beshorterthanotheraffectivephenomena(e.g.,moodsorpreferences,which aretypicallyconceptualizedasmorestable;seee.g., Beedie,Terry,Lane,& Davenport,2011).

Wewillnowdescribeeachofthefiveemotionalcomponentsandaddress theirmeasurement.Asdifferentapproachesofemotionhavefocusedon differentcomponents,wewillpresentthesetheoriesinthesectionsdealing withthecomponentsthattheyparticularlyemphasize.

1.2.2Emotioncomponents

1.2.2.1Isemotionanexpression?

Darwin’searlywork

Atypicalcharacteristicofemotionsthatisoftenusedtorecognizeemotionsin othersisthecomponentofemotionalexpressionthatcanbedisplayedfor instancewithfacialexpressions(e.g.,frowns,clenchedteeth),vocalexpressions(prosody,seee.g., Castiajo&Pinheiro,2019,andalsolaughter,screams orsobbings,seee.g., Scott,Sauter,&McGettigan,2010),bodyactionsand postures(e.g.,forwardwholebodymovementinhotanger).Bodycuesplayan importantroleinexpressingandperceivingemotionsandareincreasingly studied(e.g., Aviezeretal.,2008; Dael,Mortillaro,&Scherer,2012). However,sofar,facialexpressionshavebeenbyfarthemoststudiedsub-type oftheseexpressions.

Inthisrespect,Darwin’sinterestswerenoexception.Hewasinspiredby DuchennedeBoulogne,whostimulatedindividualfacialmusclestodetermine theirspecificexpressivevalues,andcreatedafacialmusclescartography publishedin 1862.However,Darwin’sapproachofemotionalfacialexpressionswasinnovative Darwin(1872/1998) describedthemasinnateand universalandconceptualizedtheminthecontextofevolutionandnatural selection.Heproposedthattheyhaveevolvedthroughinteractionwithour physicalenvironment.Morespecifically,hebelievedthatemotionalfacial expressionshavederivedfrompurposefulanimalactions(e.g.,showingthe teethbeforeattacking).Thus,Darwin’sperspectiveassumesthatemotionsare survivaltoolsandfocusesontheirfunctions.Forinstance,hesurmisedthatthe emotionalexpressionofdisgustwasoriginallyassociatedwiththeactionof spittingspoiledfooditems(see Chapter25).

Sincethen,ithasbeenexperimentallyshownthatsomeemotionalexpressionsdoindeedhaveafunctionalrole forinstance,theexpressionof fearenhancessensoryacquisitionwhereastheexpressionofdisgustdampens it(Susskindetal.,2008).AccordingtoDarwin,emotionalfacialexpressions consequentlydidnotdirectlyderivefromthepurposeofcommunicating emotions.Thisperspectivehadconsiderableimpactontheemotionliterature, inparticularonthebasicemotionapproach,oneofthethreemajorcurrent approachesofemotion(butforotherinfluences,seealsoPlutchik’sevolutionaryperspectivetheoryofemotions; Plutchick,1980).

Basicemotiontheories

Asmentionedabove,thebasicemotiontheorieshavebeenextensively(though notexclusively)inspiredbyworkonfacialexpressionsofemotion.This approachismoregenerallyrootedinevolutionarypsychology.Thus,emotions aredefinedhereas“transient,bio-psychologicalreactionsdesignatedtoaid individualsinadaptingtoandcopingwitheventsthathaveimplicationsfor survivalandwell-being”(Matsumoto&Ekman,2009,p.69).Thereisa limitednumberof“basic”,“primary”,“fundamental”or“discrete”emotions, whichhaveanevolutionarystatus.Notethisideaofbasicemotionisnotnew. Forinstance,inthe17thcentury, Descartes(1649/1996) alreadyidentifiedsix “primitivepassions”(“passion”formerlybeingusedasatermfor“emotion”): wonder(admiration),desire,love,joy,hatred,andsadness.

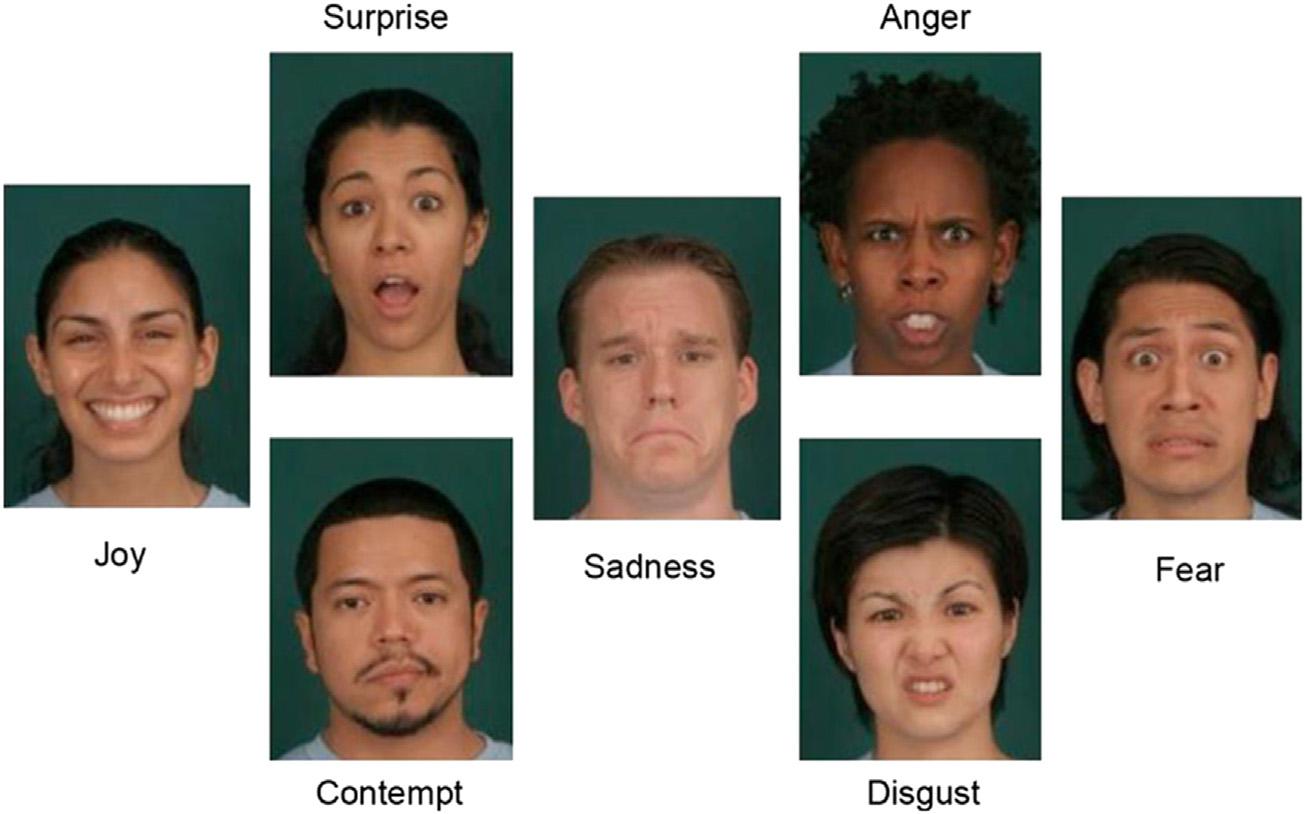

Accordingto Ekman(1994),eightcriterianeedtobefulfilledforan emotiontobeconsideredbasic:presenceinotherprimates;distinctiveuniversalsignals(whichcanbeuniversallyrecognized;see Fig.1.2);distinctive physiology;distinctiveuniversalsinantecedentevents;rapidonset;brief duration;automaticappraisal;unbiddenoccurrence.Fewyearslater, Ekman (1999) addedthreeadditionalcriteria:distinctiveappearancedevelopmentally; distinctivethoughts,memories,images;anddistinctivesubjectiveexperience.

Fear,disgust,anger,sadness,surpriseandenjoyment(“theBigSix”, Prinz, 2004,whicharetypicallyagreedupon,see Ortony&Tuner,1990)aretypicallylabeledasbasicemotionsinthistheory(seealso Matsumoto&Ekman, 2009).However,theestablishmentofwhichemotionsqualifyasbasicemotionsisatopicofdisagreementbetweenauthorswhoadvocatethisapproach. Forinstance, Izard(1977) enumeratedtenprimaryemotions:fear,disgust, anger,distress-anguish,surprise,interest-excitement,joy,contempt,shame andguilt.Bycontrast,complexemotions(e.g.,shame,pride)arethoughttobe theresultofamixturebetweenbasicemotions(e.g., Tomkins,1963).

Inthecontextofevolutionaryadaptiveness, OhmanandMineka(2001) haveevenproposedthatamoduleforfearelicitationandfearlearninghas evolved.Thismoduleispurportedly(i)selective,i.e.onlyactivatedbyfearrelevantstimuli;(ii)automatic;(iii)relativelyindependentfromcognitive processes,and(iv)itoriginatesinadedicatedneuralcircuitrycenteredaround theamygdala. Theoreticalapproachestoemotionanditsmeasurement Chapter|1 9

FIG.1.2 Theuniversalfacialexpressionsofemotionaccordingto MatsumotoandEkman (2009) ThisfigureisreproducedbypermissionofOxfordUniversityPress.

Althoughveryfruitful,thisapproachhasbeencriticized,notablybecause facialexpressionsofemotionarenotimmutableandtheirrecognitionmaynot beasuniversal(e.g., Russell,1994)aspreviouslythought(e.g., Ekman,1972; Ekman&Friesen,1971).Forinstance,cultureplaysanimportantrolein emotionrecognition(e.g., Elfenbein&Ambady,2002; Gendron,Roberson, vanderVyver,&Feldman-Barrett,2014),andsodoes,moregenerally,social information(e.g., Manstead&Fischer,2001; Mumenthaler&Sander,2012, 2015).Accordingtosomeresearchersadoptingaconstructivistapproach(e.g., Russell,Bachorowski,&Fernandez-Dols,2003),facialexpressionsof emotionareactuallynotcausedbyspecificemotions,butreflectamixtureof valenceandarousal,orsocialmessages.Theirinterpretationshouldconsequentlybeundertakencautiously.Similarly,accordingtoappraisaltheorists, emotionalexpressionsshouldbeunderstoodinthecontextofthesituation’s evaluation(deMelo,Carnevale,Read,&Gratch,2014).

Basicemotiontheorieshavebeenandarestillhighlyinfluentialinaffective sciences(Hutto,Robertson,&Kirchhoff,2018; Scarantino&Griffiths,2011). Theyinspiredmanyempiricalstudies,andstillaretoday(e.g., Guetal.,2019). Regardingemotionexpression,recentstudiessuggestthatthereareseveral emotions(upwardsof20)withdistinctmultimodalexpressions(Keltner, Sauter,Tracy,&Cowen,2019).Moreover,somecriticismsofbasicemotion theoriesoftenmisrepresentthemandcriticizespecificandfrequentlyoutdated aspectsofthem(seee.g., Keltner,Tracy,Sauter,&Cowen,2019).

Measuringemotionalexpressions

Tomeasurefacialexpressionsofemotion,severaltoolsexist.First,itis possibletousetheFacialActionCodingSystem(FACS)developedby Ekman

Theoreticalapproachestoemotionanditsmeasurement Chapter|1 11

andFriesen(1978).Thistoolisastandardizedfacialmovementcodingsystem thataimstospecifythemusclemovementsinvolvedinhumanfacialexpressionsofemotion.44musclemovementssuchastighteningofthelipsare covered.Foragivenemotionalexpression,avalueisassignedtoeachaction unitaccordingtocontractionstrength.Unfortunately,oneofitsmain disadvantagesisthatitistime-consumingtobothlearnanduse(i.e.,atrained FACScodercantakeupto100mintocode1minofvideo; Cohn,Ambadar,& Ekman,2007).TheFACShasbeenadaptedtobabies(seeBabyFACS, Oster, 2004)aswellasotheranimalsthanhumanssuchaschimpanzees(see ChimpFACS, Vick,Waller,Parr,SmithPasqualini,&Bard,2007).Oneofits advantagesisthatitisnotdependentuponaparticulartheoryofemotion. AlthoughEkmanandhiscolleagueshavedevelopedthistool,itcanbeusedto describefacialexpressionsintheframeworkofallemotiontheories.In contrasttotheFACS,theSpecificAffectCodingSystem(SPAFF; Coan& Gottman,2007)doesnotusemicroanalyticcodingbutspecificaffectcoding.

Second,electromyography(EMG)allowstheactivitymeasurementof musclesinvolved(besidesotherfunctions)infacialemotionalexpressions (e.g., Bradley,2000).Itisverydiscriminating,asitcanmeasuremuscular activityevenwhennofacialcontractionisvisible(e.g., Dimberg,Thunberg,& Grunedal,2002).Thecorrugatorsupercilii(responsibleforfurrowingone’s brow)andthezygomatic(responsibleforraisingthecornersofthelips) musclesarethemostcommonlymeasured.However,itrequirestheplacement ofsensorsontheface,whichmaypartiallyinhibitexpression.

Third,itispossibletouseautomatedfacialimageanalysismeasurement, thedevelopmentofwhichisencouragingdespiteanumberoftechnical challenges(foradiscussionofthesetwotechniques,seee.g., Coan&Allen, 2007; Mare ´ chaletal.,2019,pp.307 324, Martinez&Valstar,2016, Chapters 12and13 ofthisvolume).Althoughfurthervalidationstudiesareneeded, researchsuggeststhatsomeoftheseautomaticsoftwarescanprovideemotion detectionasreliableashumancodingforsomeexpressions(e.g., Sto ¨ ckli, Schulte-Mecklenbeck,Borer,&Samson,2018).TheAffectivaAffdexemotion recognitionsoftware(iMotions,2015)havebeensuggestedforinstanceto identifyemotionalfacialexpressionssuchashappinessandangerina comparablefashiontoEMG(Kulke,Feyerabend,&Schacht,2020).

Fourth,thermalanalysisoffacialmusclecontractions(e.g., Jarlieretal., 2011; Nguyen,Chen,Kotani,&Le,2014; Pavlidis,Eberhardt,&Levine,2002) isalsosometimesused.Bothoftheselasttwotechniqueshavetheadvantageof notrequiringsensorsontheface,thusnotrestrictingfacialexpression. Independentlyofthetoolusedtomeasurefacialexpressions,itisimportant tokeepinmindthatlargecorrelationsexistbetweentheseexpressionsandthe emotionalstate’svalenceofthepersonexpressingthem(e.g., Mauss, Levenson,McCarter,Wilhelm,&Gross,2005).Forinstance,thezygomatic muscleactivitycorrelatespositivelywiththepleasantnessofstimuli(e.g., Larsen,Norris,&Cacioppo,2003).

Besidesmeasuringfacialexpressionsofemotion,toolsalsoexistto measurerecognitionofemotioninfacialexpressions.Forinstance,facial emotionalexpressionscanbesystematicallymanipulatedusingtoolssuchas FACSGen(Roeschetal.,2011),offeringadvancedcontroloverthedisplayed expressions,andtheemotionalrecognitionthenmeasured(asusedine.g., Mumenthaler,Sander,&Manstead,2020).Finally,differenttoolshavebeen developedtomeasuremulti-modal(e.g.,facial,vocalandpostural)emotion recognition(seee.g., Ba ¨ nziger,Grandjean,&Scherer,2009; Schlegel, Grandjean,&Scherer,2014).

Besidesfacialexpressions,emotionisobviouslyexpressedinothermodalities forinstance,throughvoicesourceparameters(e.g., Bachorowski, 1999; Scherer,Johnstone,&Klasmeyer,2003).Theseparametersbelongto eithergeneralvoicequalityvariables(i.e.,tensionstateofspecificmusclesin thelarynx)orprosodicparameters(i.e.,voluntarychangesinthetensionof specificmusclesinthelarynxduringspeechproduction)(see Schereretal., 2003,and Section2.2.5.3).Themostcommonmeasuresarethevoice amplitude(i.e.,howloudthevoiceis)andthefundamentalfrequency(i.e.,the lowestfrequencyofaperiodicwaveform).Higherfundamentalfrequenciesare associatedwithhigherlevelsofarousal(e.g., Kappas,Hess,&Scherer,1991).

Emotionalcouldalsobeexpressedthroughchemosensorycuescontained insweat(e.g., Calvietal.,2020; Coppin,Parma,&Pause,2016).Suchsignals havebeenshowntoinfluenceemotionalrecognition(e.g., Pause,2012)and influencebehavioralandcerebralresponsestoemotionalstimuli(e.g., MujicaParodietal.,2009).

Formoreinformation,werecommendreading Chapter8.

1.2.2.2Isemotionanactiontendency?

Statesofactionreadiness

Dewey(1895) submittedtheideathatemotionsimply“areadinesstoactin certainways”(p.17)andsuggestedthatangerforinstance“meansatendency toexplodeinasuddenattack,notamerestateoffeeling”.Acenturylater, Frijda(1986) suggestedthatemotionshaveevolvedtoprepareandguide actionsinthedifferentenvironmentshumansface.Morespecifically,Frijda proposedthatemotionsinvolvedifferentprocessingstagesinducedby evaluatingeventsasimportanttotheindividual’smajorconcerns,leadingtoa preparationforaction.Inhisownwords,“differentactiontendenciesarewhat characterizedifferentemotions”(Frijda,Kuipers,&terSchure,1989,p.213). Arnold(1960) wasactuallythefirstresearchertoexplicitlyusethisconstruct asacentralpartofemotion.Inherwords,anactiontendencyrefersto“thefelt tendencytowardanythingintuitivelyappraisedasgood(beneficial),oraway fromanythingintuitivelyappraisedasbad(harmful).Thisattractionor aversionisaccompaniedbyapatternofphysiologicalchangesorganized towardapproachorwithdrawal.Thepatternsdifferfordifferentemotions” (p.82).Thus,emotionsarefordoing.

Theseactiontendencies(e.g.,approach,avoidance,domination,submission)preparetheindividualtoactwithspecificrelationalaims(e.g.,proximity, protection,regainingcontrol).Theyarealsothoughttounderlieovertbehavior suchasrunningaway(Frijda,2009).Similarlytofacialexpressions,some authorsarguethatthereareuniversaladaptiveactiontendencies(e.g., Shaver, Wu,&Schwartz,1992).Inrecentconceptualdevelopments,actiontendencies havealsobeenlinkedtootherbehaviors,suchasimpulsiveactions,i.e.a non-deliberateactionaimingatchangingone’srelationtoanobjectasmoreor lesspleasant(Frijda,Riddenrinkhof,&Rietveld,2014).

Twoopposingactiontendencieshavebeenmostlystudied:approachand avoidance.“Approachmotivationreferstoanurgeoractiontendencytogo towardanobject,whereaswithdrawalmotivationreferstoanurgeoraction tendencytomoveawayfromanobject”(Gable&Harmon-Jones,2008, p.476).Accordingto Davidson&Irwin(1999),twodistinctsystemsunderlie theseactiontendencies:anapproachandanavoidancesystem.Crucially,the approach-avoidanceandthepositive-negativedimensionsarenotidentical, becausebothapproachandavoidancetendenciescanleadtobothpositiveand negativeemotions(e.g., Carver,2004).Forinstance,angerisanegative emotionthatcanleadtoapproachtendencies,andadmirationisapositive emotionthatcanneverthelesstriggeravoidancetendencies.

Measuringactiontendencies

Actiontendencieshavebeenoftenmeasuredusingpushandpullreactions. Earlyresultsfrom Solarz(1960) suggestedthatparticipantswerefastertopull cardswithpleasantwordstowardthemselves(whichisassumedtoreflect approach),andtopushcardswithunpleasantwordsawayfromthemselves (whichisassumedtoreflectavoidance).SinceSolarz,othermorerecent studieshaveemployedrelateddesigns(seee.g., Cacioppo,Priester,& Berntson,1993; Phaf,Mohr,Rotteveel,&Wicherts,2014; Seideletal.,2010; Swinkels,Gramser,Becker,&Rinck,2019; Zech,Rotteveel,vanDijk,&van Dillen,2020).

Otherauthors(e.g., Kriegimeyer,&Deutsch,2010)haveuseddifferent apparatus,suchasajoystickthatparticipantshadtopulltowardthemselves (approachmovement)ortopushawayfromthemselves(avoidancemovement).Notehoweverthatinsomesituations,theassociationpull-approachand push-avoidancemaybereversed(seee.g., Phafetal.,2014 foradiscussionon thisaspect).

Thesedifferencesmayreflectdifferencesinsubordinategoals(Bossuyt, Moors,&DeHouwer,2014).Forinstance,toreachthesuperordinategoals relatedtoanger(i.e.,dominance/aggression),approach(asubordinategoal)is oftenfunctional.Butaccordingtothishypothesis,theassociationbetween angerandapproachisonlyfoundwhenapproachreflectsthegoalstoaggress orhurtsomeone.Byeliminatingthefunctionalityofapproachforthesuperordinategoalsofdominance/aggression(e.g,bymakingavoidanceserves

dominance/aggressionexperimentally),therelationbetweenangerand approachisnolongerpresent(see Bossuytetal.,2014),suggestingthat consideringsubordinategoalsisimportantwhenmeasuringactiontendencies.

Itmayseemsurprisingthattheactualactionofaparticipantisnot measuredasanindicatorofhis/heractiontendencies.However,although actiontendenciesareprecursorstoanactualbehavior,theydonotimplythata specificactionwilloccur(e.g., Elliot,Eder,&Harmon-Jones,2013). Accordingly,measuringactualbehaviorisnotnecessarilythemostinformativemeasurebecauseactiontendenciesmayoftennotbecomeactualactions, andbecausenonemotion-basedactionsmaytakepriorityinbehavior(e.g., socialnormsmayinfluencesomeonetowardshakingthehandofsomeone evenifsheisafraid).Instead,self-reportsofactiontendencieshavebeenused (e.g., Frijdaetal.,1989).Forinstance,tomeasuretheapproachandavoidance actiontendencies,itemslike“Iwantedtoapproach,tomakecontact”and“I wantedtohavenothingtodowithsomethingorsomeone,tobebotheredbyit aslittleaspossible,tostayaway”wereused,respectively.

Finally,indirectmeasuresofactiontendencieshavebeenused,inparticular the“frontalasymmetry,”whichreferstothecontrastinalphapower(8 13Hz band)foundusingElectroencephalography(EEG)intheleftversustheright frontalregion(e.g., Davidson,Ekman,Saron,Senulis,&Friesen,1999; Zhao etal.,2018).Thisasymmetryhasbeenusedasreflectingapproach(left hemisphereactivation)andavoidancemotivation(righthemisphereactivation). Forinstance,anger,anapproach-relatedemotion,hasbeenlinkedtogreat left-hemisphericactivation(Harmon-Jones&Allen,1998; Zhaoetal.,2018).

Asmentionedbefore,EMGcanmeasureactivityinmuscleswhose contractionsarenotvisible,sobeforeactionsareinitiated.Thesensitivityof thismeasureallowsthedetectionofslightcontractionsovertime,andpossibly ofsimultaneousalthoughcontradictoryactiontendencies.

Thewayanactioniscarriedoutcanalsobeusedasanindirectmeasureof actiontendencies.Forinstance,participantsafraidofspidersmovedmore directlyawayfromaspiderpictureandlessdirectlytowardaspiderpicture thancontrolparticipants(Buetti,Juan,Rinck,&Kerzel,2012; Wirth,Foerster, Kunde,&Pfister,2020).Thischangeinactiontrajectoriescanbeseenasa measureoftheactiontendencyofwithdrawingfromathreateningstimulusin spider-fearfulparticipants.

1.2.2.3Isemotionabodilyreaction?

TheJames-LangeversusCannon-Barddebate

JamesandLange’speripheralistapproach James(1884) and Lange (1885)’spositiongoesagainsttheclassicideaaccordingtowhichwefirst imagineorperceiveanemotion-elicitationevent,experienceanemotionand thenexperiencebodilyreactions.Theyclaimthatbodilyreactionselicit emotionsinconsciousnessandareconsequently primary totheemotional

Theoreticalapproachestoemotionanditsmeasurement Chapter|1 15

experience.InJames’words,“ifwefancysomestrongemotion,andthentryto abstractfromourconsciousnessofitallthefeelingsofitscharacteristicbodily symptoms,wefindthatwehavenothingleftbehind”(James,1884,p.193). Accordingtothisview,we first experiencethebodilyreactionsdirectly elicitedbytheimaginationorperceptionofanemotion-elicitationevent. Jamesfamouslystated“Mytheory isthatthebodilychangesfollowdirectly theperceptionoftheexcitingfact,andthatourfeelingofthesamechangesas theyoccurIStheemotion” (James,1884,pp.189 190).NotethatJames assumesthatthisappliestowhathethoughtofas standard emotions (e.g.,surprise,fear,anger)that,heassumes,havedistinctbodilyexpressions, buthistheoryisnotmadetoapplytootheremotions(e.g.,aestheticinterest) thatmaynothavesuchadistinctsetofbodilyreactionsaccordingtohim.

This“peripheralist”approachtoemotionwasinfluentialbecauseofits originalityandbecauseitwasempiricallytestable.Thiscontroversyregarding the“sequenceproblem”(Candland,1977)hasbeennicelysummarizedby Lange(1885):“IfIbegintotremblebecauseIamthreatenedbyaloadedpistol, doesfirstaphysicalprocessoccurwithinme,doesterrorarise,isthatwhat causesmytrembling,palpitationoftheheart,andconfusionofthought;orare thesebodilyphenomenaproduceddirectlybytheterrifyingcause,sothatthe emotionconsistsexclusivelyofthefunctionaldisturbancesinmybody?”.

CannonandBard’scentralistapproach Cannon(1927) and Bard(1928) reactiontoJames’sperspectivewasinsharpcontrastwiththeclassicalviewin the1920sofemotionaspresentedbytheperipheralistview.Accordingto CannonandBard,emotionsarefirstelicitedbytheprocessingofastimulusin thecentralnervoussystem,inparticularthethalamus.Bodilyreactionsarenot consideredtobecausalinemotionelicitation,notablybecauseoftheirlackof specificity thebodilyreactionselicitedbyverydifferentemotionscanbe similartooneanother,aswellastheonespresentinnon-emotionalstates.

Cannon(1927) conductedseveralempiricaltestsinanimalstodisprovethe peripheralistapproach.Forinstance,hereportedthatabolishingvisceral afferentsdidnotpreventemotionsandthattheartificialinductionofthebodily reactionsassociatedwithagivenemotiondidnotelicitthisemotion.But Cannon’stestshavealsobeencriticized(e.g., Fehr&Stern,1970).James’ theoryfocusedontheconsciousexperientialaspectofemotion.Thisaspect cannotcurrentlybestudiedinanimalsothersthanhumansbylackof appropriatemethods.ThisinabilityconstitutesamajorlimitationofCannon’s workonanimals.

Areviewof134publicationsontheexistenceofpatternsofbodily reactionsspecifictoaparticularemotionhasconcludedthatthereisevidence for“considerableautonomicnervoussystemresponsespecificityinemotion whenconsideringsubtypesofdistinctemotions”(see Kreibig,2010,p.394; seealso; Moreira,Chaves,Dias,Costa,&Almeida,2018; Siegeletal.,2018). Responsepatternscangenerallybediscriminatedbetweenbasicemotions.

However,thisneitherdemonstratesautonomicspecificity,nordoesitexplain thefactorsthatcouldunderliethesedifferences.Forinstance,ifangerandfear areassociatedwithadifferentpatternofbodilyreactions,thismaybebecause angerelicitsanapproachtendencywhilefearevokesawithdrawaltendency.

Theconsequencesofthisdebateformodelsofemotion Thehistorical James-Lange/Cannon-Barddebatehasbeenandisstillimportantinemotion research.Aspointedoutby Ellsworth(1994),itishoweverimportanttokeep inmindthatJames’stheoryhasbeensimplifiedandthatbodilyreactionswere nottheonlyimportantaspectofit-theinterpretationofthestimuluswas,too. Importantly,thisdebatehasinitiatedempiricalresearchregardingthe temporalsequenceofemotion.Letusmentionbrieflythreelinesofwork derivedfromthis.

First, Allport(1924) andlater Tomkins(1962) suggestedthatfeedback fromthefacialexpressionsplayanimportantroleinthedifferentiationof emotions knownasthefacialfeedbackhypothesis(Laird,1974; Tourangeau &Ellsworth,1979),whichmayextendtoposturalfeedbackalso(e.g., Stepper &Strack,1993).Thus,fromthisperspective,emotionsarethoughttobe “sets ofmuscleandglandularresponseslocatedintheface” (Tomkins,1962).

Second,embodiedtheoriesofemotion(Niedenthal,2007)havesuggested thatembodiment(reenactmentsofemotionalexpressionsbutalsoofa particularphysiologicalstate)isakeyelementtotakeintoaccountwhen consideringemotionelicitation.Inlinewiththefacialfeedbackhypothesis, contractingfacialmusclesrecruitedinagivenemotionalexpressioncould intensifyorelicitthecongruentemotion,evenwhenparticipantsarenotaware ofthiscontraction’sgoal(e.g., Soussignan,2002; Strack,Martin,&Stepper, 1988).Suchresultsarehowevercontroversialandcurrentliteraturelacksclear replicationofsuchfindings(see Wagenmakersetal.,2016).

Third,thisdebatehasinfluencedseveralmajorauthorsinemotionresearch, notablySchachterinpsychologyandDamasioinneurosciences.

InlinewithJames-Lange’sidea, SchachterandSinger(1962) have presentedanewtheoryofemotionaswellanexperimentdesignedtosupport it.Thetwo-factortheorytheyconceivedemphasizestheroleofphysiological arousal(i.e.,whatJamescalledbodilyreactions)butalsoofcognition. Schachterbelievedthatphysiologicalarousalwasnotenoughtoproducean emotion.Similarly,hebelievedthatcognitionwithoutphysiologicalarousal wouldnotproduceanemotion.

SchachterandSinger’sexperimentisfamous,despiteitscritics(e.g., Maslach, 1979; Plutchik&Ax,1967)andthenon-systematicreplicationofitsmainresults (e.g.,see Reisenzein,1983).Moregenerally,whilethetheoryhasgeneratedalot ofinterestingwork,datatendsnottosupportit(e.g., Cotton,1981).Itishowever stillinfluentialforitsemphasisontheroleofcognitivefactors.

Damasio’sperspectiveisaneo-Jamesiantheoryofemotion.Hehassuggestedtheexistenceof“somaticmarkers,”i.e.physiologicalreactions

associatedwithpastemotionalevents(Damasio,1994).Whenaneweventis encountered,thesemarkersareactivatedandinfluencedecision-making.For instance,whenanindividualisexposedtoanobjectpreviouslyassociatedwith pleasantexperiences(e.g.,achocolatecakeassociatedwiththeingestionof nutrients),thesesomaticmarkersorbodilysensationsbiastheevaluationsand decisionsofthisindividual(makinghim/hermorelikelytoapproachand possiblyconsumethiscake).Theconceptofsomaticmarkershasnotablybeen testedintheIowagamblingtask(see Bechara,Damasio,Damasio,& Anderson,1994).

Currenttheoreticaldebatesinaffectivesciencesstillconcernthespecificity ofsomebodilyreactionsforsomespecificemotions,andthecausalroleof bodilyfeelingsintheconsciousexperienceofemotion.

Measuringbodilyreactionsandbodilyfeeling

Tothebestofourknowledge,allcurrentmajortheoriesofemotionconsider bodilyreactionsasanaspectofemotion.Forinstance,accordingtoappraisal theories,physiologicalreactionssupportadaptedresponsesfortheexpression ofemotionandproductionofactiontendencies.Consequently,measuring themisimportant.Whenstudyingemotions,manypsychophysiological indicatorscanbemeasuredandcombined(seee.g., Kreibig,2010, Chapter4 ofthisvolume).Theyallhavetheadvantagetoeliminateself-reportbiases (e.g., Orne,1962).Webelievethattheirchoiceshouldbemotivatedbythe questionofinterestandnotbysimply“measuringagivenemotion”.

Mostofthesemeasuresarecardiovascular(i.e.,bloodcirculatorysystem; e.g.,heartrate,heartratevariability,systolicanddiastolicbloodpressure, pre-ejectionperiod,totalperipheralresistance),electrodermal(i.e.,sweat gland;e.g.,skinconductancelevel,skinconductanceresponses),respiratory activity(e.g., Stevenson&Ripley,1952),inadditiontothepostauricularreflex (e.g., Stussietal.,2018)orthestartlereflexmeasurement(e.g., Lang,Bradley, &Cuthbert,1990).Whileheartrate(e.g. Delplanqueetal.,2009)andstartle reflexamplitude(e.g., Bublatzky,Guerra,Pastor,Schupp,&Vila,2013)are relativelygoodindicatorsofvalence,skinconductance(e.g., Boucsein,2012) andpupildiameter(e.g., Bradley,Miccoli,Escrig,&Lang,2008)aremore arousal-related.Someofthesemeasuresprimarilyreflectsympatheticactivity (e.g.,skinconductancelevel),acombinationofsympatheticandparasympatheticactivity(e.g.,heartrate),orprimarilyparasympatheticactivity (e.g.,heartratevariability).

Asstatedby Kreibig(2010,pp.29),thephysiologicaladjustmentsthatare elicitedbyemotionconsistofanintegratedpatternofresponses.Itisconsequentlyimportanttojudiciouslychoosethepsychophysiologicalindicator(s) relevantforaparticularstudyandanalyzethemproperly.Notethatseveral guidelinesareavailableontheSocietyforPsychophysiologicalResearch website(e.g.,forthestartlereflex: Blumenthaletal.,2005;forheartrate: Jenningsetal.,1981).

Besidesmeasuringbodilyreactionsperse,onemaywanttomeasurethe subjectiveperceptionofbodilysensations.Nummenmaa’steam(e.g., Volynets etal.,2014; Hietanen,Glerean,Hari,&Nummenmaa,2016; Nummenmaa, Hari,Hietanen,&Glerean,2018)havedevelopedanindirecttoolofbodily reactions,calledthe“emBODYtool”.Itmeasuresthefeelingofincreasedand decreasedactivitiesindifferentbodyregionsduringanemotionalepisode.The participantisaskedtocolorregionswhoseactivitybecomesstrongerorfaster, andregionswhoseactivitybecomesweakerorslower. Nummenmaaetal. (2014) havemeasuredthesemapsofbodilysensationsforbasicemotionsin differentculturesandfoundthattheywereconcordantacrosscultures. Hietanenetal.(2016) showedthatthistoolcanbeusedinadultsaswellasin children.Interestingly,thesebodilymapscanbecorrelatedwithpsychophysiologicalmeasurestoassesswhetherthesubjectiveperceptionofbodily sensationsandtheactualsensationsarematching.

Finally,inamoresocialperspective,itisworthmentioningthatchemosignals(forinstance,signalspresentinsweat(e.g., Prehn,Ohrt,Sojka,Ferstl, &Pause,2006)tears(Gelsteinetal.,2011)orexchangedduringhandshaking (Fruminetal.,2015)maybeinvolvedinmodulatingphysiologicalreactionsin others(inthefirsttwoexamplesquoted,effectswereshownonthestartle reflexanddifferentpsychophysiologicalindicatorsofsexualarousalaswellas testosteronelevelsinmen,respectively).

1.2.2.4Isemotionafeeling?

Dimensionaltheoriesofemotion

Incurrenttheoriesofemotion,“feeling”oftenreferstothesubjectiveexperience,typicallyconscious,thattakesplaceduringanemotionalepisode.With thisrespect,feelingsareoftenthoughtwithrespecttodiscreteemotions (e.g.,feelinghappy),butcomponentsofemotions(e.g.,appraisal)ordimensions ofemotion(e.g.,valenceorarousal)havealsobeenlinkedtofeelingsinvarious perspectives:researchersdiscuss“feltappraisals”or“feltarousal”forinstance. “Emotion”and“feeling”areoftenusedinterchangeablyineverydaylanguage. Thiswasalsooftenthecaseinearlyscientificstudyofemotion,tothepointthat onecouldarguethatmostearlytheoriesofemotion(e.g.,Wundt’sandJames’) wereactuallytheoriesofwhatisnowadaysratherconsideredasfeeling.

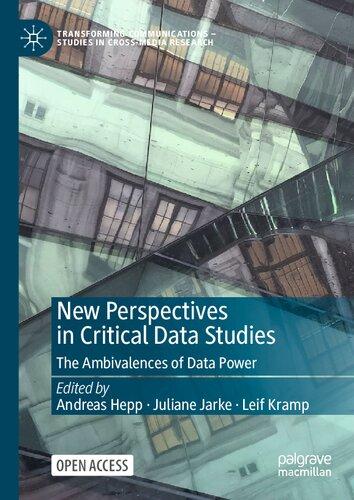

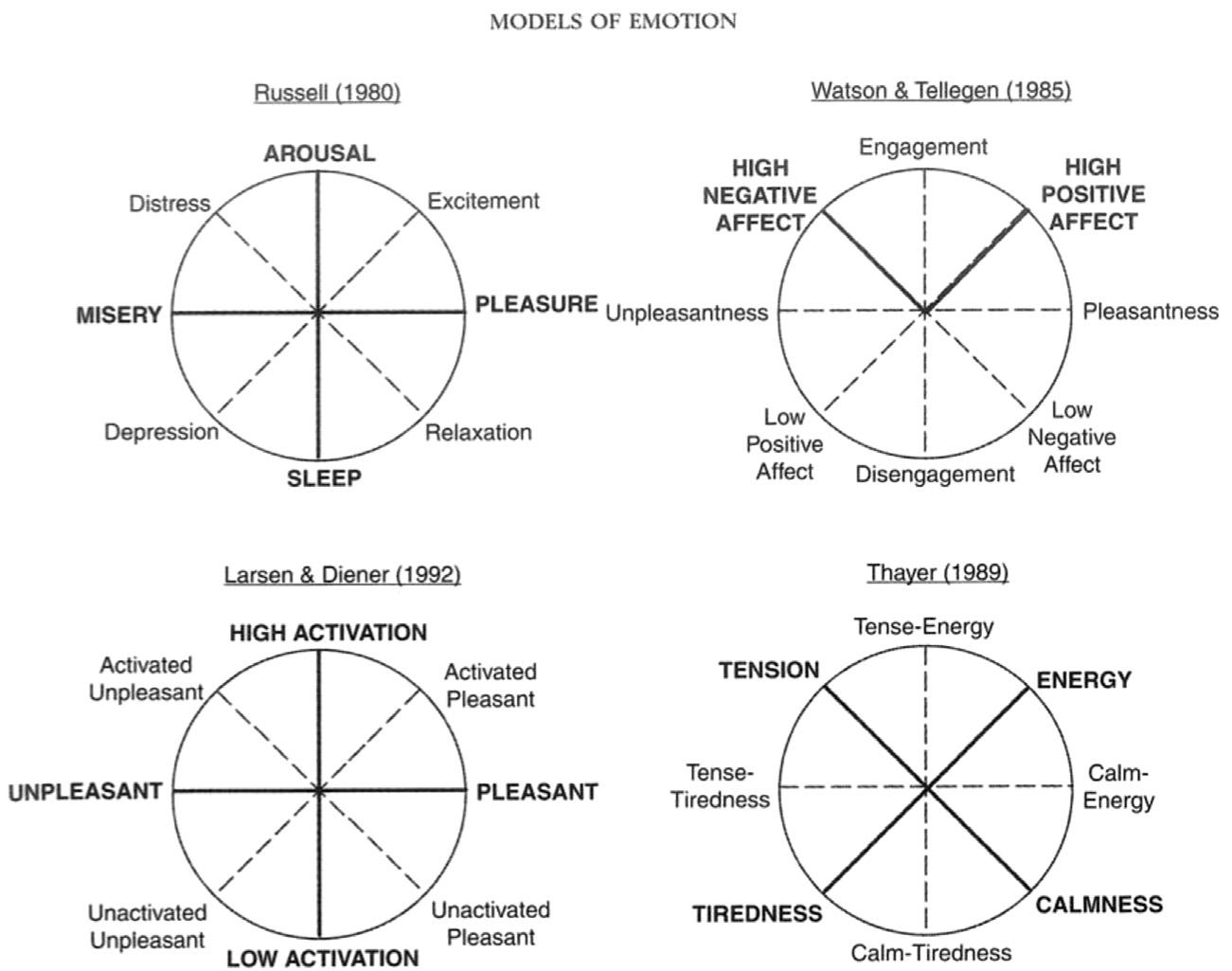

Severalmodelshavedescribedfeelingwithdifferentdimensions.For instance,morethanacenturyago,theWundt’smodelsuggestedthreebasic dimensions(pleasure/displeasure,excitement/inhibition,andtension/relaxation)(Wundt,1905).Bi-dimensionaltheoriesofemotiontypicallyconsider feelinginnotthreebuttwoelementarydimensions. Russell(1980) notably suggestedacircumplexmodelofemotion(see Fig.1.3 forachart).Thismodel representsemotionsusingacirclewithtwoaxes:thevalencedimension indicatingpleasure/displeasure(thatalmostallcurrentmodelsconsider necessary,see Colombetti,2005)andanotherdimensionindicatingarousal.

Theoreticalapproachestoemotionanditsmeasurement Chapter|1 19

FIG.1.3 Representationoffourtypesofaffectivecircumplexmodelsofemotion. Thisfigureis reproducedbypermissionofOxfordUniversityPress.

Later(e.g., Barrett,Mesquita,Ochsner,&Gross,2007; Russell,2005),this circumplexmodelhasbeenlinkedtowhatiscalled“coreaffect”(Russell, 2003),i.e.theneurophysiologicalstate,alwaysaccessible,offeelinggoodor bad,energizedorrelaxed.Accordingtotheconceptualactmodelofemotion (Feldman-Barrett,2006),emotionsemergefromcoreaffectandcategorization.Thus,psychologicalconstructiontheoriesalsosurmisethatvalenceand arousalarethemajorcharacteristicsofemotions(see Chapter2).

Currently,thisapproachisprobablythemostcommonlyusedformeasuring subjectiveemotionalexperience,althoughithasbeencriticized.First,considering valenceandarousalasthetwomaindimensionsoffeelingiscontroversial.Second, thinkingofthesedimensionsasaunidimensionalcontinuumisalsocontroversial (seee.g., Cacioppo&Berntson,1994; Robbins,1997, Chapter4).Third, disentanglingphysiologicalarousalfromotherdimensionssuchastheintensityof theemotionalexperienceortheintensityoftheemotion-elicitingstimulusis important.Fontaineandcolleaguesshowedthatfourdimensions evaluationpleasantness,potency-control,activation-arousalandunpredictability capture appropriatelytheemotionalexperience(Fontaine,Scherer,Roesch,&Ellsworth, 2007).Thus,twodimensionsonlymaynotofferasatisfactorilyrepresentationof emotioncomplexity.