List of Maps and Illustrations

1.1. Map of the Polish-lithuanian commonwealth, 1569–1619. courtesy of Béla nagy, hungarian academy of sciences, Budapest.

21

1.2. Map of transylvania, c.1570. courtesy of Béla nagy, hungarian academy of sciences, Budapest. 26

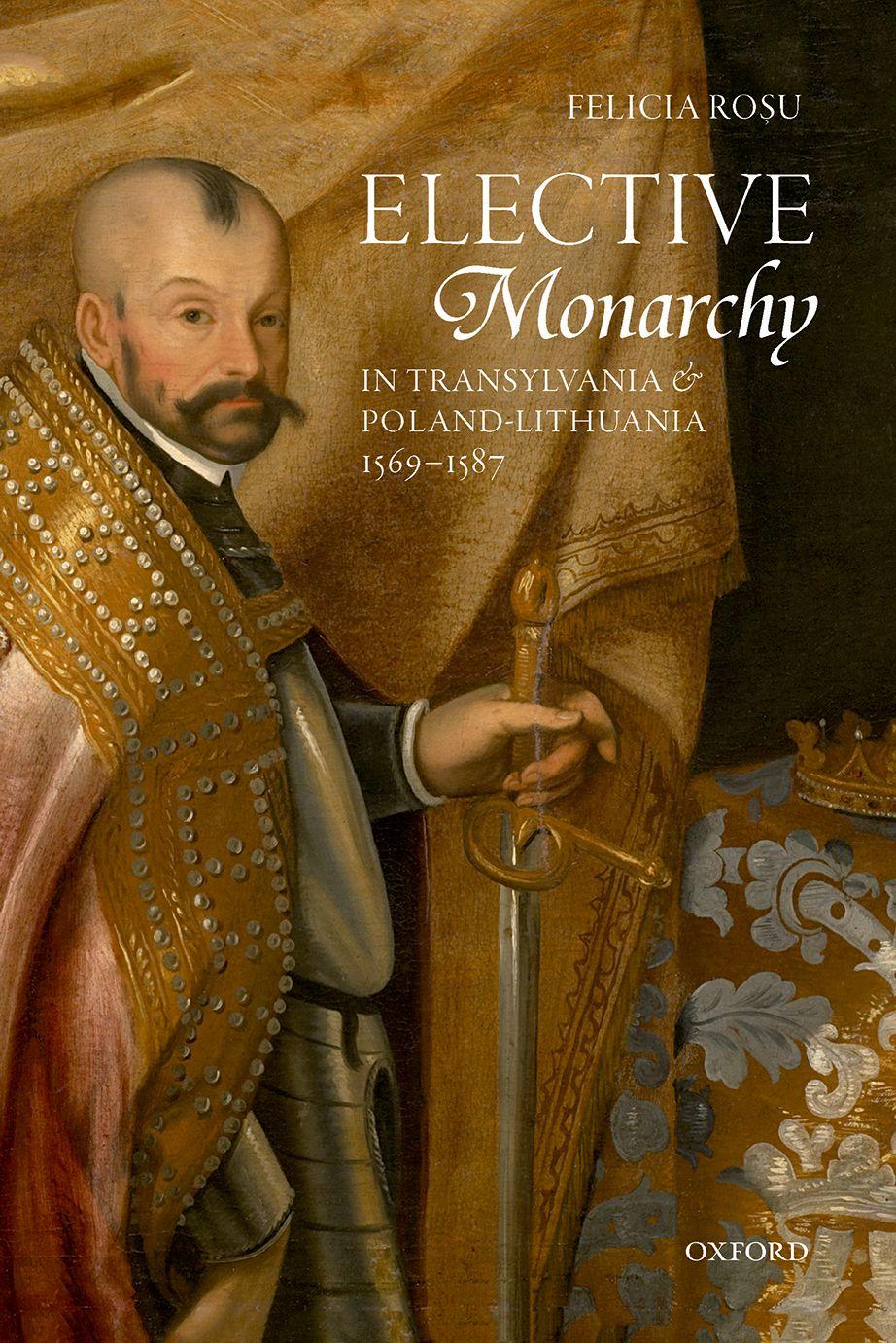

1.3. Portrait of stephen Báthory, late sixteenth century. anonymous. czartoryskich Museum, cracow.

1.4. Portrait of anna Jagiellon in coronation clothes, 1576. Martin Kober. Wawel cathedral, cracow.

1.5. Portrait of henry valois in Polish hat, c.1580–6. attributed to François Quesnel. Muzeum narodowe, Poznań.

1.6. Portrait of sigismund iii vasa, c.1626. Pieter claesz. alte Pinakothek, Munich.

2.1. ‘Effigies illustrissimi principis nec non serenissimi electi regis Poloniae, etc., stephani Batori’, december 1575–May 1576. anonymous. sächsisches staatsarchiv, hauptstaatsarchiv dresden, 10024 Geheimer rat (Geheimes archiv), loc. 10697/03, Bl. 368b–369a.

28

36

37

38

88

List of Abbreviations

a rchival Mat E rial

aGad archiwum Główne akt dawnych, Warsaw aradz. archiwum radziwiłłów aZam. archiwum Zamoyskich

MK ll Metryka Koronna, libri legationum ZBran. Zbiór Branickich z suchej asv archivio segreto vaticano asven. archivio di stato di venezia aPconst. archivio proprio constantinopoli aPcontarini archivio proprio contarini sen. dispacci degli ambasciatori al senato Bczart. Biblioteka im. ks. czartoryskich, cracow tn teki naruszewicza

BnF Bibliothèque nationale de France, Paris

BPanc Biblioteka Polskiej akademii nauk, cracow tP teki Pawińskiego

BuW Biblioteka uniwersytetu Warszawskiego, Warsaw dJanc direcţia Judeţeană a arhivelor naţionale, cluj

FBistr. Fond Primăria oraşului Bistriţa

FKem. Fond Familia Kemény

dJans direcţia Judeţeană a arhivelor naţionale, sibiu

aF acte fasciculare

Bruk. colecția Brukenthal dE documente episcopale hhsta haus-, hof- und staatsarchiv, vienna

Mol Magyar országos levéltár, Budapest

osZK országos széchényi Könyvtár, Budapest

PBath. Protocollum Bathorianum

WaPc Wojewódzkie archiwum Państwowe, cracow asang. archiwum sanguszków

Print E d s ourc E s adr sokołowski, ed., Archiwum domu Radziwiłłów aJZ sobieski, ed., Archiwum Jana Zamoyskiego

Bethlen Bethlen, Historia de rebus Transsylvanicis caligari caligari, Epistolae et acta czubek czubek, Pisma polityczne z czasów pierwszego bezkrólewia dudith dudith, Epistulae

EoE szilágyi, ed., Erdélyi országgülési emlékek

Forgách Forgách, Magyar historiája

heidenstein heidenstein, Dzieje Polski laureo Wierzbowski, ed., Vincent Laureo

xvi List of Abbreviations

lescalopier lescalopier, ‘călătoria în Țara românească și transilvania’ noailles noailles, ed., Henri de Valois, vol. 3 orzelski orzelski, Interregni Poloniae libros

Possevino Possevino, Transilvania szádeczky szádeczky, ed., Báthory István lengyel királylyá választása szamosközy szamosközy, Történeti maradványai spannochi spannochi, ‘discours de l’interregne’ vc Grodziski, dwornicka, and uruszczak, eds, Volumina Constitutionum vl Konarski and Kaczmarczyk, eds, Volumina Legum

Personal and Place Names

There is no easy answer when it comes to personal and place names in east-central European history, but a compromise must be made between historical precision, faithfulness to the sources, and readability. to facilitate comprehension, i have used English versions for the first names of rulers and their immediate families (stephen Báthory instead of istván Báthory; John sigismund szapolyai instead of János Zsigmond szapolyai), but where a satisfying English equivalent does not exist and for persons of lesser rank, i have kept the versions most commonly used in their respective native or dominant languages (Jan Zamoyski, istván Werbőczi). For place names, i have used English equivalents where they exist (Warsaw, cracow, vienna) and the most recognizable modern versions for major towns (vilnius, Kiev). For German towns throughout the region, i have used the German versions of their names (hermannstadt, danzig). The solution is not perfect, but for uniformity’s sake and also to reflect the prevailing tendency in my sources, i have used hungarian and Polish names for smaller places in transylvania and Poland-lithuania respectively, and i have adopted the Polish spelling of provinces and palatinates in Poland-lithuania (Bracław, for instance), except when a latinized or English version exists (Mazovia, Podolia, or lesser and Greater Poland). Furthermore, i have used the latinized ‘ruthenia’ or ‘ruthenian’ to indicate the ruś palatinate (województwo ruskie) in southern Poland, but also in reference to the wider cultural and religious identity of the population comprising the territories of modern-day ukraine and Belarus (also referred to as ‘ruś’ in Polish and ‘russia’ in latin). The distinction between the palatinate and the wider region is not always clear in the sources, but i have indicated when it is. lastly, i have occasionally used ‘Poland-lithuania’ as a short form for the commonwealth of Poland-lithuania (informally called by its inhabitants ‘the republic’, formally ‘the Polish crown and the Grand duchy of lithuania’). ‘Poland-lithuania’ does not appear as such in the sources, but i have found it expedient to adopt this shortcut here and there, in order to increase readability. translations are my own, unless otherwise indicated.

Introduction

The Right of electing Kings was vested in, and belong’d only to such of the People, who were eminent for their Goodness and Love of Liberty. Such only who stood possess’d of this high Character, were look’d upon as the properest Persons to call those Kings to an Account, who were declared Enemies to Vertue; and to execute Vengeance upon Tyrants Those Nations, which are govern’d by Kings, in an unalterable and uninterrupted Succession, are (in the Judgment of us Polanders) either such, whose People were heretofore of a barbarous and savage Disposition, or much addicted to Tumults and Seditions: And of these we now see many still laboring under heavy Yoke of absolute Dominion and Tyranny.1

In the early modern period, the closest precursor of the modern presidential suffrage were the thirteen elections for king that were held between 1573 and 1764 in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. The only other place in Europe with similar succession rules was Transylvania, where twenty-five elections for ‘voivode’ (as the Transylvanian ruler was called) took place between 1571 and 1704. These experiments in large-scale suffrage were noisy, uncertain, and hazardous affairs that threatened public stability and were highly susceptible to inner divisions and outside influence. And yet, regardless of the dangers and abuses involved, the Transylvanian and Polish-Lithuanian estates insisted on their right to ‘free elections’, generation after generation, until outside powers put an end to their autonomous existence. According to some observers, the elective system was the cause of their undoing.

Without purporting to cover the development of elective monarchy across the whole early modern period, this book is an examination of why and how the elective principle, already established in Transylvanian and Polish political culture in the late medieval period, was transformed in the 1570s. It does so by focusing on the foundational and experimental character of the first elections of 1571, 1573, and 1575–6. In May 1571, Stephen Báthory was elected by the estates of Transylvania to be their ‘free prince’. His election marked a decisive moment in Transylvania’s history as well as Hungary’s. The estates of the newly autonomous province chose to elect, for the first time in their history, a ruler separate from and with no claim to the Hungarian crown: a ‘free prince’. Even though the Transylvanians had participated in elections of rulers before, those had always been

1 Wawrzyniec Goślicki, The Accomplished Senator (1568), 1733 English edition (Miami, 1992), 29.

Elective Monarchy in Transylvania and Poland-Lithuania kings of Hungary and not autonomous rulers of Transylvania alone. Several factors determined such a development, chief among them the Ottoman presence in the region, which had separated Transylvania from Hungary in the first place. Equally significant was the insistence of two Transylvanian estates, together with the nobility from a few adjoined Hungarian counties, on the right to elect their ruler. Báthory’s election was the first of many power transfers that, despite frequent irregularities, occasional violence, and constant fear, set the stage for the reenactment of the Transylvanians’ right to self-government, until its abolition in 1711. The two successions that followed Báthory’s election—that of his older brother Christopher, then of his nephew Sigismund, both orchestrated by their incumbents and the political establishment—taught the estates a lesson and paved the way for the gradual introduction of the right of resistance in Transylvania’s electoral conditions from 1599 onward.

Poland-Lithuania’s first two elections were equally crucial for the subsequent development of elective monarchy in the commonwealth. In 1573, the first election took place. The votes favoured Henry Valois—brother of Charles IX of France—but Henry ruled Poland-Lithuania for only four months after his coronation. When, in June 1574, he learned about the death of his brother, he snuck out of the royal castle in Cracow and rushed to France in order to become Henry III of France. A new election was organized to replace him. After a tense campaign and several confusing voting sessions, two simultaneous winners were declared: Maximilian II Habsburg—Holy Roman emperor and king of Hungary; and Stephen Báthory—the same man who had been chosen to rule Transylvania five years before. Báthory was eventually crowned king of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Although his older brother assumed formal control of Transylvania after his departure to Poland-Lithuania, Báthory continued to use the title of prince of Transylvania. He set up a chancery for Transylvanian affairs in Cracow, and he ruled the two countries until his early death in 1586.

While this book examines aspects of both of Poland-Lithuania’s first two elections, it pays particular attention to the second. As the reign of Henry Valois barely went beyond his coronation, Stephen Báthory was the first elected PolishLithuanian king who actually governed his voters. As interesting as Báthory’s reign was, his election was even more so. It ended a long and tumultuous interregnum during which the citizens of the commonwealth were forced to de facto depose their first elected king—thus applying the right of disobedience they had inscribed in their public records only two years before.

The second Polish-Lithuanian election raised important questions about the ideal of consensual politics that governed decision-making in Poland-Lithuania. On 12 December 1575, Maximilian II—Holy Roman emperor, head of the Habsburg dynasty, and king of Hungary—was proclaimed king of Poland-Lithuania by the archbishop of Gniezno and the majority of the senate. Two days later, Stephen Báthory, ruler of Transylvania, vassal of the Ottomans, and, incidentally, secret liegeman of Maximilian II because of his position as ruler of Transylvania, was hailed winner of the same election by the greater part of the nobility, who bitterly resented the senators’ preference for a Habsburg king. The complications created

by this situation threatened public peace after the election and lingered on for almost a year after Báthory’s coronation. The tensions and divisions of the second election, together with the conflicts generated by Báthory’s governing strategies, left a long-lasting mark on future elections and the relationship between king and nobility in the commonwealth.2 The third Polish-Lithuanian interregnum, which ended with another double election and eventually the coronation of Sigismund III Vasa in December 1587, is not discussed at length in this book, but some of its debates and general patterns—characteristic for the early elective period—are included in the analysis.

The dominant characteristics of these elections are explored thematically: campaigning strategies, voting procedures, legitimacy issues after enthronement, and the contract between voters and their elected rulers are discussed in turn, while giving equal share to empirical detail and theoretical interpretation. The events of 1571 were much more than an election: they were the culmination of a power struggle among the Transylvanian estates, the German emperor, and the Ottoman sultan, all of whom attempted to assert their authority in the region. The result of that election—and the mere fact that it took place—not only determined the identity of a new ruler, but it also marked the separation of Transylvania from Hungary and the appearance of a new political entity on the map of Europe, one in which the estates sought to carve and maintain an enhanced political role. The PolishLithuanian elections of 1573 and 1575–6 were equally foundational in character: not only did they redraw the constitutional framework of the commonwealth, but they also opened the Polish-Lithuanian throne to foreign candidates. Although less vulnerable than Transylvania to outside threats, royal elections in Poland-Lithuania were just as susceptible to outside influence. The rivalry between sultan and emperor was felt there as well, while the eligibility of foreign candidates involved a myriad of European interests in the electoral race. Candidates were both native and foreign contenders and the elections were a major event that was closely followed abroad, since almost every major power in the region had a candidate in the game or a stake in the outcome. The system stayed in place until the dissolution of the commonwealth at the end of the eighteenth century, and its peculiarities would attract the attention of major political thinkers throughout its existence, from Jean Bodin in the sixteenth century to Jean-Jacques Rousseau and Thomas Jefferson in the eighteenth.

Elective monarchy was not unique to Transylvania and Poland-Lithuania. It was in fact the predominant form of succession in northern and east-central Europe from the late Middle Ages until the seventeenth century. Sweden, Denmark, Bohemia, Hungary, and medieval Poland had all been elective systems. However, the form that elections took in early modern Transylvania and Poland-Lithuania went much further than the earlier semi-dynastic versions they had shared with their neighbours. First, unlike the rest of Europe’s elective monarchies, they distanced

2 Gebei Sandor, ‘Az erdélyi fejedelmek és a lengyel királyválasztások’ (Ph.D. dissertation, Hungarian Academy of Sciences, 2004), 43–4; Ewa Dubas-Urwanowicz, O nowy kształt Rzeczypospolitej: kryzys polityczny w państwie w latach 1576–1586 (Warsaw, 2013).

Elective Monarchy in Transylvania and Poland-Lithuania

themselves from the dynastic principle by allowing it to be overridden by other factors. In that, they can be seen as similar to Venice, Genoa, and the papal states— although the differences in scale and political structure make the comparison rather limited. Second, their voters were more numerous than elsewhere—especially in the Polish-Lithuanian case. The Holy Roman emperor was elected by seven electors, the Danish king by approximately twenty councilmen, the Venetian doge by forty-one electors, and the pope by about seventy cardinals. In Poland-Lithuania, however, elections became open to all members of the nobility (szlachta), who could participate in person (viritim) next to the members of the senate and delegates from the most important towns. Not everybody who had a right to vote showed up, but the thousands who did spent weeks debating (and sometimes fighting) about the best candidate, following interregna that could last two years. Transylvanian elections were much more limited from this perspective, but the two to three hundred estate delegates who attended the 1571 election were still more numerous than voters elsewhere.

Large-scale elections do not necessarily imply democratic procedures. Birth, office, and fortune made some votes count more than others, and in both countries the nobility dominated all other social groups. Still, this system created opportunities for innovative political arrangements. The nobility—especially its lower echelons— had a particularly dynamic role in the second half of the sixteenth century, as has also been noted by scholars of early modern France.3 The Transylvanian and PolishLithuanian cases problematize the Weberian assumption that citizenship was by necessity an urban phenomenon; their versions of constitutional monarchy propose a different but comparable model from the ones developed in the Low Countries or England. Furthermore, the dominance of the noble estate in sixteenth-century Polish-Lithuanian and Transylvanian elections was not absolute. Not only ecclesiastical corporations and urban delegates, but also the landless nobility participated in the decision-making process. Since decisions were based on public deliberations and sealed with explicit expressions of consensus, the agreement of all participants— or at least their abstention from disagreement—had to be secured for each resolution. The public character of elections, combined with the efforts at persuasion that took place both on and behind the scenes, resulted in the inclusion of more than the privileged few.

Royal and princely elections were not business as usual in early modern politics. Intense affairs that only occurred every few years—and sometimes every few decades— they disrupted everyday life for many months at a time. Rivalries, alliances, compromises, and struggles took place at a faster pace and with greater force than during calmer times. They were a form of ‘exceptional politics’ that served to re-establish, after the death of each ruler, the basis of the political community.4 They were constitutionally regulated recalibrations of the balance of power between rulers and estates. Such moments reflected the goals and interests animating citizens to

3 J. Russell Major, From Renaissance Monarchy to Absolute Monarchy: French Kings, Nobles, and Estates (Baltimore, 1994), xix.

4 Giorgio Agamben, State of Exception (Chicago, 2005), 4.

a greater degree than the periods of ‘normal politics’, precisely because elections were times of choice Even more, they were times of discursive choice—due to the widely used system of public voting—which inextricably linked political speech to political action. Voting for one candidate implied justifying that choice abstractly and exercising the power to implement it practically; speech was action.5 These choices often had to be made under duress. When the threat of civil war or external intervention put the community under extraordinary pressure, its members had a choice not only between alternative value systems (a ‘powerful’ ruler vs. a ‘weak’ ruler, a Habsburg vs. a Hungarian, an emperor vs. a minor prince) but also between political principles and mere pragmatism (liberty and self-government vs. fear of the ‘Turk’). Such choices were not always ‘either–or’ situations: sometimes, contradictory elements were seamlessly reconciled, not only at the level of conflicting interests but also at the level of diverging values.

Poland-Lithuania and Transylvania had much in common, but the validity of comparing such different entities deserves explanation. As a Polish commentator noticed around 1680, ‘everything similar is also dissimilar’ and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth and Transylvania are no exception.6 Poland-Lithuania was a large independent country with a history of monarchic rule going back several centuries. Transylvania, by contrast, was not a monarchy, but rather the offshoot of one—an experiment in elective rulership that struggled with a dubious identity throughout its century and a half of autonomous existence. The Ottoman conquests of the 1520s and 1540s had cut it off from the old Hungarian kingdom to which it formerly belonged and placed it under the suzerainty of the Ottoman sultans who, following a clever divide-and-rule strategy, supported the Transylvanian estates’ insistence on the right to elect their rulers. The western remainder of the Hungarian monarchy—from which Transylvania inherited its basic structures, including the elective principle—might have provided a better comparison for Poland-Lithuania had it not been reduced to a shadow of its former self by the simultaneous advance of the Ottomans, who took advantage of its internal divisions, and the Habsburgs, who gradually weakened its constitutional make-up after their assumption of the Hungarian crown in 1526.7

Meanwhile, Transylvania went through a phase of political reinvention closer to Polish-Lithuanian than to Hungarian trends. The adoption of the elective system there marked the beginning of a dynamic that lasted until 1711, in which the estates periodically offered electoral support to their rulers in exchange for legislative influence. There was no lack of autocratic rulers who tried, and at times succeeded, to make their power more independent of the estates, but the

5 Kolja Lichy, ‘How to Do Politics with Words: Oratory, Ceremonial and Procedure in the Sejm and the Reichstag (c.1500–1570)’, Parliaments, Estates and Representation 29, no. 1 (1 January 2009): 67–84.

6 Igor Kąkolewski, ‘Comparatio dwóch monstrów: Rzeczpospolita polsko-litewska a Rzesza Niemiecka w XVI–XVIII wieku’, in Rzeczpospolita-Europa XVI–XVIII wiek. Próba konfrontacji, ed. Michał Kopczyński and Wojciech Tygielski (Warsaw, 1999), 143.

7 See Robert J. W. Evans, ‘The Poland-Lithuanian Monarchy in International Context’, in The Polish-Lithuanian Monarchy in European Context c.1500–1795, ed. Richard Butterwick (Houndmills, 2001), 29–31.

Monarchy in Transylvania and Poland-Lithuania

constitutional instruments used by the latter to restrain the power of the former were periodically revised at each election and became increasingly complex in time. A similar phenomenon occurred in the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, where the conditions imposed on newly elected kings allowed the estates and especially the lower nobility to enforce upon their rulers their vision of the political community to a degree never experienced before. In short, the two polities adopted constitutional arrangements different in depth and scope but based on the same fundamental principles: elective thrones, state-sanctioned religious pluralism, and constitutional guarantees for the right of disobedience. There were important variations in their regulation and application, but the ex-Hungarian province and the newly created Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth had one essential thing in common: they were the only two polities in early modern Europe whose political systems secured the succession of their rulers through large-scale elections in which the dynastic principle, although still important, was not binding. The Transylvanians’ attachment to what they called ‘free election’, regardless of the irregularities and abuses involved in the process, was strikingly similar to the insistence of the Polish-Lithuanian nobility on their right to elect their kings.

The uniqueness of the Polish-Lithuanian and Transylvanian elective systems does not mean that the problems they attempted to address—the uncertainties of royal succession, religious diversity, and the bottom-up push for representation— were unique in sixteenth-century Europe. In the 1570s and 1580s, most of Europe’s dynastic monarchies were undergoing major succession crises, while political and religious turmoil questioned the legitimacy of their reigning and future monarchs. The authority of the Spanish king was being dismantled in the Low Countries; the death of Sebastian I opened the Portuguese succession crisis of 1578–80; England was led by an unmarried queen, which made it possible for the elective solution to be contemplated in the 1590s; and in Scotland, George Buchanan powerfully argued that the Scottish throne was elective in nature. In France, constitutional solutions were feverishly sought by members of all major factions in response to the religious, political, and dynastic crises of the late Valois period, and the elective principle was seriously considered by Huguenot and later by Catholic monarchomachs, especially at the time of Henri III’s assassination.8

Meanwhile, the heirs of late medieval elective systems were experiencing their own phases of constitutional experimentation, clarification, and redefinition. Throughout the Reformation wars, the Holy Roman Empire retained its composite character and elective principle, although succession to the imperial throne was in practice dynastic. After the dissolution of the Kalmar Union, the Scandinavian monarchs were able to strengthen their position to the point of being able to impose hereditary succession in 1544 (Sweden) and 1660 (Denmark). Bohemia

8 Jean Bodin, ‘Apologie de Rene Herpin pour la Republique’, in Les six livres de la république, ed. Christiane Fremont, Marie-Dominique Couzinet, and Henri-Marie Rochais, 6 vols. (Paris, 1986), 6:313–409, 319; and Les six livres, bk 6, chap. 5, p. 213; James B. Collins, The State in Early Modern France, 2nd ed. (Cambridge, 2009), 1–2; Dorota Pietrzyk-Reeves, Ład rzeczypospolitej: Polska myśl polityczna XVI wieku a klasyczna tradycja republikańska (Cracow, 2013), 404–6; Howard Nenner, The Right to Be King: The Succession to the Crown of England, 1603–1714 (London, 1995), 1–6.

and one third of Hungary came under Habsburg control after 1526; they too would eventually be forced to accept the hereditary solution (in 1627 and 1647/1687). In Transylvania, the estates defended the elective principle more successfully, at least until the Habsburg takeover, which abolished elections in 1688. Finally, between 1569 and 1609, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth underwent a process of legal reconstruction and invention that resulted in the longest-lived and most constitutionally elaborate system of royal elections in early modern Europe.

As far as the crises of royal succession and authority were concerned, three solutions were generally applied in early modern Europe. One was to forgo kingly rule altogether, whether by design or by accident, as was the case in the Dutch republic, mid-seventeenth-century England, and the Swiss and Italian republics. Another was the effort to legally regulate hereditary rule: the role of the French Salic law, from this perspective, was to provide an overarching principle that transcended the whims of individual kings and prevented them from treating the realm as their private property. The third solution was elective and conditional rulership, which ultimately sought to accomplish the same thing as the Salic law, i.e. control the dangers related to hereditary succession and personal rule, but by radically different means than those envisaged by the proponents of strong and undivided monarchic sovereignty.

The common denominator of such disparate processes was a widely shared concern for legal codification. Political struggles certainly revolved around the distribution (or accumulation) of power, but power’s most important means of expression in late medieval and early modern Europe was the law. ‘We are slaves to the law in order that we may be free,’ wrote Sebastian Petrycy of Pilzno in his 1605 addenda to Aristotle’s Politics, citing Cicero’s famous phrase.9 Bernard Connor, the Irish physician who, at the end of the seventeenth century, produced one of the first detailed descriptions of Poland-Lithuania available to the Anglophone public, wrote that for ‘the Polish gentry . . . “lex est rex”, the law is their king’.10 Because in early modern Europe precedents were valued in all legal dealings—from matters of inheritance to fundamental constitutional principles—the innovations of the late sixteenth century were almost always accompanied by efforts to connect them to distant roots. For example, the English were obsessed with their ‘ancient constitution’ and the Huguenots attempted to prove that the French throne had originally been elective—an argument seized by the Catholic League (and abandoned by the Huguenots) as soon as Henry of Navarre became heir apparent.11 Similarly, the political treatises leading

9 Sebastian (z Pilzna) Petrycy, Pisma wybrane: przydatki do etyki, ekonomiki i polityki arystotelesowej (Warsaw, 1956), 2:252.

10 Bernard Connor, The History of Poland in Several Letters to Persons of Quality Giving an Account of the Ancient and Present State of That Kingdom (London, 1698), 1:6. See also Wacław Uruszczak, ‘Le principe “lex est rex” dans la théorie et dans la pratique en Pologne au XVIe siècle’, in Aequitas— Aequalitas—Auctoritas: Raison théorique et légitimation de l’autorité dans le XVIe siècle européen, ed. Danièle Letocha (Paris, 1992), 119–26; ‘In Polonia lex est rex: Niektóre cechy ustroju Rzeczypospolitej XVI–XVII w.’, in Polska na tle Europy XVI–XVII wieku (Warsaw, 2007), 14–26; Historia państwa i prawa polskiego, t. I (966–1795), 3rd ed. (Warsaw, 2015), 142, 212–14.

11 Francis Oakley, The Watershed of Modern Politics: Law, Virtue, Kingship, and Consent (1300–1650) (New Haven; London, 2015), 173; Sarah Hanley, ‘The French Constitution Revised: Representative