ADVANCESINECOLOGICAL RESEARCH

SeriesEditor

GUYWOODWARD

ProfessorofEcology

ImperialCollegeLondon

SilwoodParkCampus

BuckhurstRoad

AscotBerkshire

SL57PYUnitedKingdom

MikeChristie

SchoolofManagementandBusiness,AberystwythUniversity,Aberystwyth,United Kingdom

B.JackCosby

CentreforEcologyandHydrology,Bangor,Gwynedd,UnitedKingdom

JamesE.Cresswell

CollegeofLifeandEnvironmentalSciences,UniversityofExeter,Exeter,UnitedKingdom

LynnV.Dicks

DepartmentofZoology,UniversityofCambridge,Cambridge,UnitedKingdom

IsabelleDurance

CardiffSchoolofBiosciences,CardiffWaterResearchInstitute,Cardiff,UnitedKingdom

DarrenM.Evans

SchoolofBiological,BiomedicalandEnvironmentalSciences,UniversityofHull,Hull,and SchoolofBiology,NewcastleUniversity,NewcastleuponTyne,UnitedKingdom

Marı´aR.Felipe-Lucia

InstituteofPlantSciences,UniversityofBern,Bern,Switzerland,andInstitutoPirenaicode Ecologı´a-CSIC,Av.NuestraSen ˜ oradelaVictoria,s/n,Jaca,Spain

VirgilFievet

INRA,UMR1202,BIOGECO,Cestas,andUniversityofBordeaux,UMR1202, BIOGECO,Pessac,France

ColinFontaine

Centred’EcologieetdesSciencesdelaConservation(CESCOUMR7204),Sorbonne Universites,MNHN,CNRS,UPMC,CP51,55rueBuffon,Paris,France

MichelleT.Fountain

EastMallingResearch,Kent,UnitedKingdom

MichaelP.D.Garratt

CentreforAgri-EnvironmentalResearch,SchoolofAgriculture,PolicyandDevelopment, UniversityofReading,Reading,UnitedKingdom

RichardJ.Gill

DepartmentofLifeSciences,SilwoodPark,ImperialCollegeLondon,Ascot,Berkshire, UnitedKingdom

LeonieA.Gough

DepartmentofLifeSciences,SilwoodPark,ImperialCollegeLondon,Ascot,Berkshire, UnitedKingdom

MikeGreen

NaturalEngland,Worcester,UnitedKingdom

ChrisM.Hartfield

NationalFarmersUnion,AgricultureHouse,StoneleighPark,UnitedKingdom

MartinHarvey

DepartmentofEnvironmentEarthandEcosystems,TheOpenUniversity,WaltonHall, MiltonKeynes,UnitedKingdom

CorinneVacher

INRA,UMR1202,BIOGECO,Cestas,andUniversityofBordeaux,UMR1202, BIOGECO,Pessac,France

JessicaVallance

UniversitedeBordeaux,ISVV,UMR1065SanteetAgroecologieduVignoble(SAVE), BordeauxSciencesAgro,andINRA,ISVV,UMR1065SAVE,Villenaved’Ornon,France

AdamJ.Vanbergen

NERCCentreforEcology&Hydrology,Edinburgh,UnitedKingdom

AlfriedP.Vogler

DepartmentofLifeSciences,SilwoodPark,ImperialCollegeLondon,Ascot,Berkshire,and DepartmentofLifeSciences,TheNaturalHistoryMuseum,London,UnitedKingdom

AndrewWeightman

CardiffSchoolofBiosciences,CardiffWaterResearchInstitute,Cardiff,UnitedKingdom

PiranC.L.White

EnvironmentDepartment,UniversityofYork,York,UnitedKingdom

GuyWoodward

DepartmentofLifeSciences,SilwoodPark,ImperialCollegeLondon,Ascot,Berkshire, UnitedKingdom

LearningEcologicalNetworks fromNext-Generation SequencingData

CorinneVacher*,†,1,AlirezaTamaddoni-Nezhad{ , StefaniyaKamenova},},NathaliePeyrardk,YannMoalic#, RégisSabbadink,LoïcSchwaller**,††,JulienChiquet{{,M.AlexSmith} ,

JessicaVallance}},}},VirgilFievet*,†,BorisJakuschkin*,† ,

DavidA.Bohankk

*INRA,UMR1202,BIOGECO,Cestas,France †UniversityofBordeaux,UMR1202,BIOGECO,Pessac,France

{DepartmentofComputing,ImperialCollegeLondon,London,UnitedKingdom

}INRA,UMR1349IGEPP,LeRheu,France

}DepartmentofIntegrativeBiology,UniversityofGuelph,Guelph,Ontario,Canada kINRA,Toulouse,France

#LaboratoiredeMicrobiologiedesEnvironnementsExtre ˆ mes(LM2E),InstitutUniversitaireEurope ´ endela Mer(IUEM),Universite ´ deBretagneOccidentale,Plouzane ´ ,France

**INRA,UMR518MIA,Paris,France

††AgroParisTech,Paris,France

{{LaMME,UMRCNRS8071,Universite ´ d’Evry-Vald’Esonne,Evry,France

}}Universite ´ deBordeaux,ISVV,UMR1065Sante ´ etAgroe ´ cologieduVignoble(SAVE),BordeauxSciences Agro,Villenaved’Ornon,France

}}INRA,ISVV,UMR1065SAVE,Villenaved’Ornon,France kkUMR1347Agroe ´ cologie,AgroSup/UB/INRA,Po ˆ leEcologiedesCommunaute ´ setDurabilite ´ desSyste ` mes Agricoles,DijonCedex,France

1Correspondingauthor:e-mailaddress:corinne.vacher@pierroton.inra.fr

Contents

1. Introduction2

1.1 EcologicalInteractionsAreDriversofEcosystemFunctioning 2

1.2 EcologicalInteractionsAreAlteredbyAnthropogenicActivity 4

1.3 Next-GenerationSequencingCanBeUsedforMonitoringEcological Interactions 5

2. WhyLearningEcologicalNetworksfromNGSData? 7

2.1 LimitationsofClassicalMethodsforResolvingEcologicalInteractions7

2.2 AdvantagesofNGSforIdentifyingSpeciesandTheirInteractions 8

3. ExamplesofNGS-BasedEcologicalNetworksandTheirApplications 10

3.1 DecipheringPathobiomesUsingNGS-BasedMicrobialNetworksforImproving BiologicalControl 10

3.2 StudyingtheHologenomeTheoryofEvolutionUsingNGS-BasedMicrobial Networks 12

AdvancesinEcologicalResearch,Volume54 # 2016ElsevierLtd ISSN0065-2504Allrightsreserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/bs.aecr.2015.10.004

3.3 TestingtheNichePartitioningTheorywithNGS-BasedTrophicNetworks14

3.4 ChallengestoBeAddressedtoGetPredictiveInsightsfromNGS-Based Networks17

4. TheoreticalMethodsforDecipheringEcologicalNetworksfromNGSData18

4.1 TheInputData18

4.2 InferringEcologicalInteractionsUsingStatisticalModels21

4.3 LearningEcologicalInteractionsUsingLogic-BasedMachine-Learning Algorithms23

Speciesdiversity,andthevariousinteractionsthatoccurbetweenspecies,supportsecosystemsfunctioningandbenefithumansocieties.Monitoringtheresponseofspecies interactionstohumanalterationsoftheenvironmentisthuscrucialforpreserving ecosystems.Ecologicalnetworksarenowthestandardmethodforrepresentingand simultaneouslyanalyzingalltheinteractionsbetweenspecies.However,deciphering suchnetworksrequiresconsiderabletimeandresourcestoobserveandsamplethe organisms,toidentifythematthespecieslevelandtocharacterizetheirinteractions. Next-generationsequencing(NGS)techniques,combinedwithnetworklearningand modelling,canhelpalleviatetheseconstraints.Theyareessentialforobservingcryptic interactionsinvolvingmicrobialspecies,aswellasshort-terminteractionssuchasthose betweenpredatorandprey.Here,wepresentthreecasestudies,inwhichspecies associationsorinteractionshavebeenrevealedwithNGS.Wethenreviewseveralcurrentlyavailablestatisticalandmachine-learningapproachesthatcouldbeusedfor reconstructingnetworksofdirectinteractionsbetweenspecies,basedontheNGS co-occurrencedata.Futuredevelopmentsofthesemethodsmayallowustodiscover andmonitorspeciesinteractionscost-effectively,undervariousenvironmentalconditionsandwithinareplicatedexperimentaldesignframework.

1.INTRODUCTION

1.1EcologicalInteractionsAreDriversofEcosystem Functioning

Foraconsiderablepartofthehistoryofecology,ecologistshavetriedto observeandexplaintherelationshipsbetweenbiodiversityandecosystem functioning(BEFrelationship)andhowthesechangewithenvironmental conditionsandhuman-derivedstressors(see Bohanetal.,2013;Cardinale

dynamicsandcascadingeffectsonsupportingecosystemservices’byMulder etal.).Thereis,however,littleagreementon,orclearunderstandingof,the bestpracticesforpreventinglossesinspeciesdiversity,andofhownetworks ofinteractingspeciesmayberestored(butsee Pococketal.,2012).Whatwe do haveareexpectationsregardinghownetworksmaychangewithenvironmentalstressors,suchasagriculturalintensification(Albrechtetal., 2007;Laliberte ´ and Tylianakis,2010; Tylianakisetal.,2007)orbiological invasions (Aizenetal.,2008;Albrechtetal.,2014;Helenoetal.,2009; Lopezaraiza-Mikel etal.,2007;Vacheretal.,2010).However,predicting a priori exactlyhowaparticularecologicalnetworkmetric(e.g.speciesrichness,numberoflinks,interactionstrength,connectance,modularity, nestedness)willchangeinresponsetoaparticularstressorremainsdifficult (Helenoetal.,2012).Definingecologicallyrelevantnetworkmetrics (Bluthgen etal.,2008;Fortunaetal.,2010;Joppaetal.,2010;Leger etal.,2015)andpredictinghowtheyaffectnetworkstructuralstability and thepersistenceofthespecieswithinit(Bascompteetal.,2003; Montoya etal.,2006;Rohretal.,2014;Saavedraetal.,2011;The ´ bault andFontaine,2010)isalsoverychallenging.

Simply reducingorremovinganthropogenicstressorsmaynotbe enoughtorestorethestructureofecologicalnetworksandthefunctioning ofecosystems.Forexample,inarecentgrasslandexperiment,plantdiversity inplotsthatreceivedhighratesofnitrogenfor10yearshadnotrecoveredto controllevels20yearsafterthenitrogeninputshadstopped(Isbelletal., 2013).Thissuggeststhat‘turningbacktheclock’toamorebenignsetof management practices,evenwherethisisfeasible,mightnotachieverestorationgoals.Thereis,indeed,increasingevidencethatnetworkstructure anddynamicsmodulatesthetrajectoryandrateofchangeoftheresponse tostressors,withtimelagsandthepresenceofmultiplealternativestable states,duetoecologicalinertiainthefoodweb.Alternativestablestateshave beensuggestedasthereasonsfortheslowornon-existentbiologicalrecoveryofcommercialmarinefisheriesfollowingreductionsinfishingeffort,and offreshwatersfollowingacidification(Layeretal.,2010,2011)andeutrophication (Schefferetal.,2001).

1.3Next-GenerationSequencingCanBeUsedforMonitoring EcologicalInteractions

Whileecologicalnetworksplayacentralroleinthedevelopmentofbasic andappliedecologicalscience,most empiricalnetworksremainatbest

2.1LimitationsofClassicalMethodsforResolving EcologicalInteractions

Networkecologyprimarilyemergedbasedontheobservationofinteractionsbetweenmacro-organisms(e.g.plant–pollinator,plant–herbivore, plant–seeddisperser,anemone–fish;seeIWDB, https://www.nceas.ucsb. edu/interactionweb/resources.html). Theseobservationsrequireconsiderabletimeandresourcesandhavelimitations.Smallerspecies,suchas microbesandparasites,haveoftenbeenoverlooked(Laffertyetal.,2008) despitetheirimportanceforecosystemfunctioning(Ducklow,2008; GilbertandNeufeld,2014;Hudsonetal.,2006).Asaconsequence,integrationofmacro-organismsandmicro-organismsresolvedatthespecieslevel intothesamenetworksisfarfromthenorm(butsee Vacheretal.,2008, 2010).Short-terminteractionssuchasthosebetweenpredatorandprey arealsodifficulttoobserve.Thislackofcompletenessandintegrationof ecologicalnetworkscriticallylimitsourunderstandingofBEFandshould beresolved(Fontaineetal.,2011).

Micro-organismshavenotbeenfullyintegratedinnetworkecology la rgelyduetotheenormousdifficultyassociatedwithidentifyingtheinteractingmicrobes.Microbialinteractionshavelongbeenstudiedusinglaboratoryculture-dependentmethods.However,testingthehundredsof combinationsofculturecondition snecessarytofindtheconditions requiredtogrowsuccessfullyasinglemicrobialspeciesisoftenprohibitive (Lok,2015 ).Asaconsequence,anestimated85 – 99 %ofbacteriaand archaeacannotyetbegrowninthelab, drasticallylimitingourknowledge ofmicrobiallife.Culturingisnotonly a(inadvertently)selectiveenvironment,butalsoalabourintensiveandtedioustaskthatcannotbeextended tothewholemicrobialcommunityin agivenenvironment.Co-culture experimentsaretraditionallyusedto detectantagonisticormutualistic interactionsbetweenmicrobialtaxabut theextrapolationofresultstonaturalconditionsisrisky( Sheretal.,2011).High-throughputcultivation platf orms,suchasmicrofluidicchip sandiChips,arecurrentlyrevolutionizingthisfieldofresearch.Theyarebasedoncomplexcultivationmedia, closertothoseofthenaturalenvironmentandmaysupportmultiple microbialspecies(Lok,2015).Culturingandco-culturingmicrobes

neverthelessremainacomplicatedtask( Harutaetal.,2009).Manyscienti stshave,therefore,chosentobypassitentirelyandmovetosequencing directlymicrobialDNA.

Manyscientistsstudyingtrophicnetworkshavealsochosentouse DNAsequencingforcharacterizingpredator–preyorhost–parasitoid interactions.Thevisualandmicroscopicexaminationofguts,faeces,or pellets(Hengeveld,1980;Pisanuetal.,2011)andtherearingofparasitoids from hosts(Eveleighetal.,2007;Mu ¨ lleretal.,1999)areindeedtimeconsuming,labourintensiveandhighlydependentontheobserver’sexperience.Theytendtooverlookcrypticspeciesandareverydifficultto comparebetweensystemsorresearchers(reviewedby Symondson, 2002).Directmethodshaveexpandedrecentlytoincludetheanalysisof ratios ofnaturallyoccurringstableisotopes(mostlycarbonandnitrogen), permittingtheintegrationoftrophicinformationoveranextendedtimescale(severaldaystoseveralmonths)(Boecklenetal.,2011).Nevertheless, thetechniquecanonlybeappliedtoasmallnumberofpreyspecies(Moore and Semmens,2008)andoftendoesnotpermitobtainingaccuratetrophic data atindividuallevel(VanderkliftandPonsard,2003).Otherbiomarkers, such asfattyacids(reviewedby Traugottetal.,2013)havesimilar constraints.

2.2AdvantagesofNGSforIdentifyingSpeciesandTheir Interactions

TheemergenceofNGStechniquesandassociatedbioinformaticpipelines hasboostedthecharacterizationofspeciesandtheirinteractionsoverthelast 10years.Inparticular,ithasboostedthecharacterizationofmicrobialcommunities(DiBellaetal.,2013;Hibbettetal.,2009)andfacilitatedthequantification oftrophiclinks(Smithetal.,2011;Staudacheretal.,2015).NGS indeed overcomesthelimitationsofculture-dependentmethodsandprovidesamorethoroughdescriptionofmicrobialcommunities.Weare now,inprinciple,abletodetectanymicrobialorganisminnature,even thosethatcannotbeisolatedorgrowninthelab.Thefirststepistocollect environmentalsamples(e.g.samplesofsoilorwater,tissuesofplant,animal, etc.)andextracttotalDNAfromthesesamples.Thetaxonomicdescription ofmicrobialcommunitieswithNGStechniquesthenreliesontheamplificationandsequencingofDNAbarcodes(Chakrabortyetal.,2014).Similarly, thesequencingoffaeces,pellet,orgutcontentgivesaninsightintothe dietofanorganismwithlittleornoneedfor apriori informationaboutthe

targetpreyspecies(e.g. Boyeretal.,2013;Brownetal.,2012;Que ´ me ´ re ´ et al.,2013;Shehzadetal.,2012).Moreover,theuseoftags(i.e.unique identifiers) torecoverdatafromeachsampleaftersequencing(Clarke et al.,2014;Taberletetal.,2012)facilitatesthemassscreeningofseveral hundreds ofindividualsamples(e.g. Kartzineletal.,2015;Mollot et al.,2014).

A DNAbarcode,initssimplestdefinition,isoneorsmallnumberof shortgeneticsequencestakenfromastandardizedportionofthegenome thatareusedtoidentifyspecies(SchlaeppiandBulgarelli,2015).Different barcode regionsareusedfordifferenttaxonomicgroups.Themostpopular DNAbarcodeforidentifyingfungalspeciesistheinternaltranscribedspacer (ITS)regionofthenuclearribosomalrepeatunit(Schochetal.,2012), except forGlomeromycota( € Opik etal.,2014;Stockingeretal.,2010). The 16Ssmallribosomalsubunitgene(16SrRNA)isthe‘goldstandard’ forcharacterizingbacterialcommunitycomposition(Sunetal.,2013), although otherbarcoderegionshavebeenproposed(Chakrabortyetal., 2014).The16SrRNAgenecontainsconservedregionsaswellasnine hypervariable regions(V1–V9).Oneormoreofthesehypervariableregions areusuallysequenced(Glooretal.,2010;Sunetal.,2013).Universal barcode genesarealsoavailableforalgaeandprotozoa,but,toourknowledge,notforviruses(Chakrabortyetal.,2014).Thestandardizedbarcode region foreukaryoticanimalsispartofthecytochrome c oxidase1(CO1) mitochondrialgeneandagrowinglibraryofidentifiedspecimensexists(see BOLD, http://www.boldsystems.org/; Ratnasingham andHebert,2007). Inthecaseoftrophicecology,thebestbarcodedependsuponthemodel organism,itslikelypreys,andthequestionbeingaddressed(Pompanon etal.,2012).Generally,asdietarysamplesarecomplexmixturesofhighly degradedDNA,thebestbarcodeshouldtargetveryshortDNAfragments withthesameamplificationefficiencyacrossverydistantlyrelatedtaxa. Theseconstraintssometimesprecludespecies-leveltaxonomicassignment ofpreysastheprobabilitytoencountervariablesitesdecreaseswiththe sequencelength.Therefore,classicalDNA-basedmethodssuchdiagnostic PCRfollowedbySangersequencingremainsveryusefulforthequantitative assessmentofpredator–prey(Clareetal.,2009;Rougerieetal.,2011)and host–parasitoidinteractions(Condonetal.,2014;Kaartinenetal.,2010; Smithetal.,2008).Thesemolecular-basedtechniqueshavebeenusedsuccessfullytorevealpreviouslyunseentrophicinteractions(Deroclesetal., 2015;Wirtaetal.,2014).

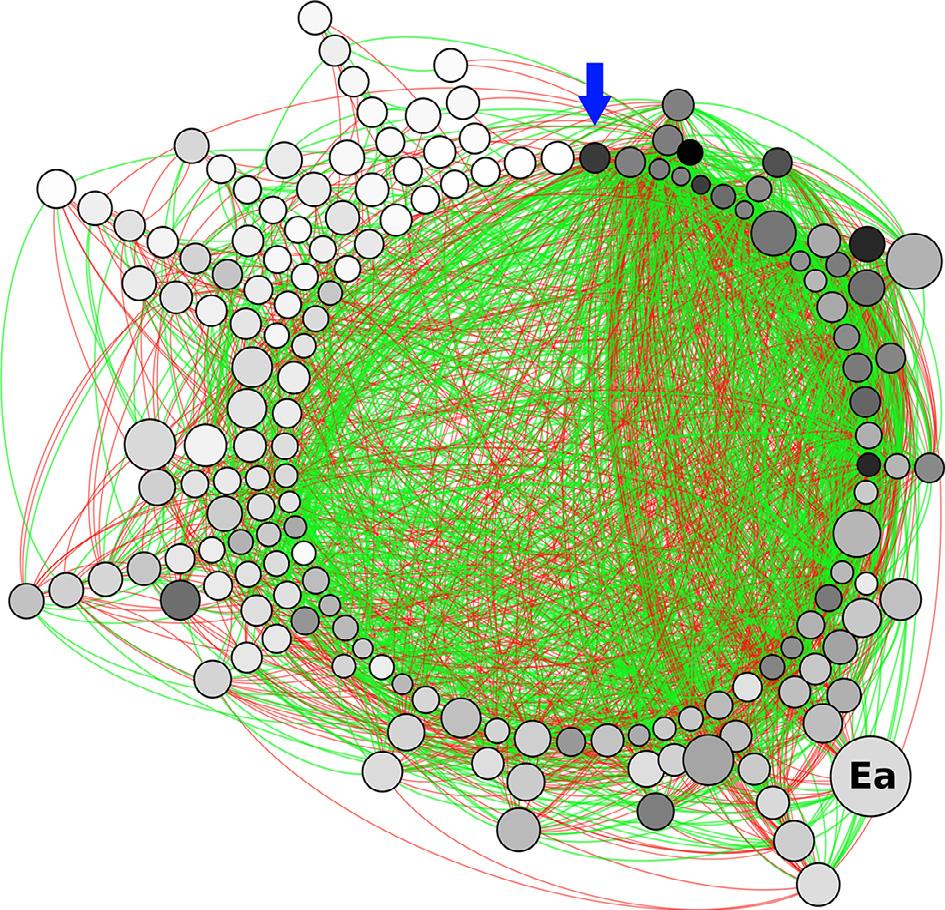

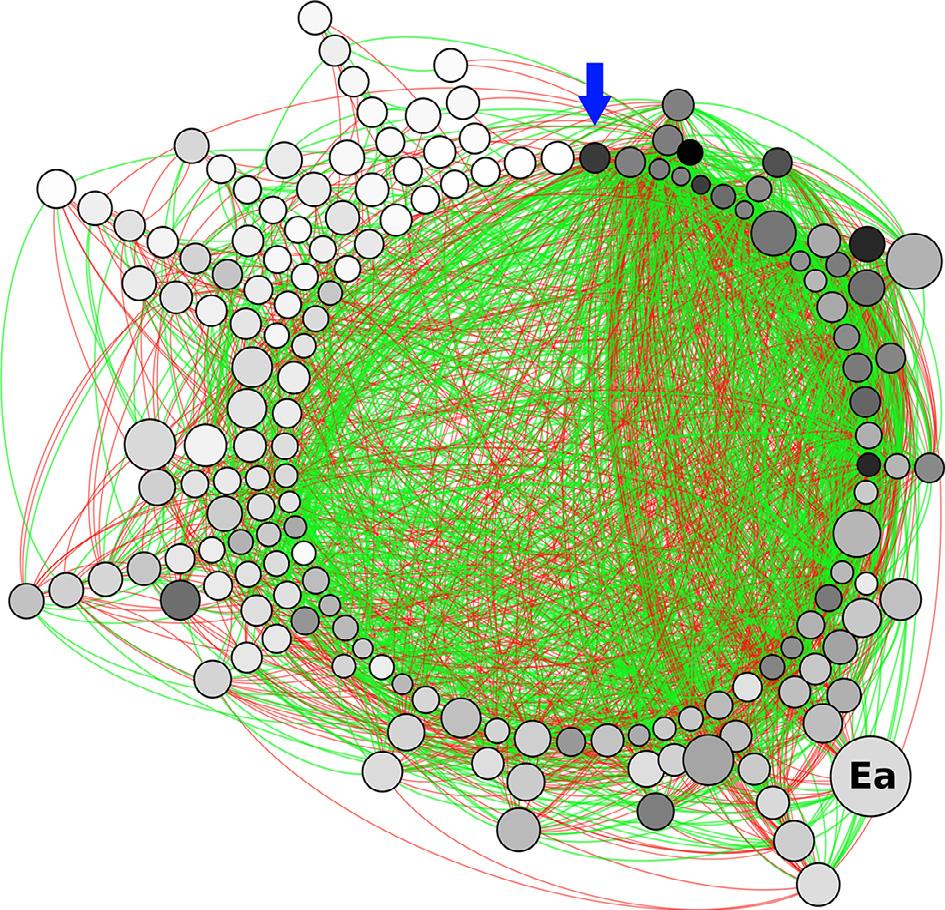

Figure1 Microbialassociationnetworkoftheleavesofanoaktree(Q.robur L.)susceptibletothefoliarfungalpathogen E.alphitoides (Ea).Eachnoderepresentsamicrobial taxon(eitherbacterialorfungal)andeachlinkrepresentsasignificantcorrelation betweentheirabundances.Red(greyintheprintversion)andgreen(greyintheprint version)linksindicateco-exclusionsandco-associations,respectively.Thearrowindicatesthenodewiththehighestdegree(i.e.thehighesttotalnumberoflinks).Degree decreasesclockwise,withnodesstackedonthesamelinehavingthesamedegree.The sizeofthenodesisinverselyproportionaltothesumofthecorrelationcoefficients: largernodeshavemorenumberand/orstrongernegativeassociations.Darkernodes havehigherbetweennesscentrality(calculatedontheabsolutevaluesofassociations), suggestingthattheyaretopologicalkeystonetaxa. E.alphitoides ispredominantlyconnectedtothenetworkthroughstrongnegativelinks(co-exclusions)butisnotagood candidatefortopologicalkeystonespecies.

Schwalleretal.,2015).Suchnetworkwouldallowustoidentifythemicrobialspeciesthatdirectlyimpedeorfacilitatepathogendevelopment.

3.2StudyingtheHologenomeTheoryofEvolutionUsing NGS-BasedMicrobialNetworks

Humansaredrasticallyandrapidlyalteringtheenvironment,includingclimate,andmanyspeciesmaynotbeableofadaptingquicklyenoughtothese newconditions(Carrolletal.,2014).Themismatchbetweenthephenotype ofagriculturallyimportantplantsandnewclimateisanoverarching

niches(HectorandHooper,2002;MacArhur,1958).Thisdifferentiationof ecological nichesreducescompetitionandpromotesco-existencebetween species(Chesson,2000;LevineandHilleRisLambers,2009).NGStechniques promisetobringsignificantchangesinourunderstandingofniche partitioningbecausetheyprovideinformationabouttheentiredietrange ofaspecies,whilealsohighlightingnewandunexpectedtrophiclinks. Forinstance, Ibanezetal.(2013) carriedoutatrait-basedestimationof the trophicnichewidthoffourspeciesofgrasshoppersthroughchoice experimentsandNGSstudyoftheirdiet.Theyshowedthatobservedtrophicnichebreadthingeneralistherbivorousinsectsdependsonboth species-specificfoodpreferencesandhabitatdiversity,andthatitisnotan intrinsicpropertyofthespeciesasusuallyconsideredintheoreticalstudies.

Kartzineletal.(2015) alsousedNGStechniques,incombinationwithstable isotope analyses,toinvestigatetrophicnichepartitioningamongsympatric largemammalianherbivoresinKenya.Theyobservedunsuspectedfinescaleresourcepartitioningevenbetweenspecieswithinthesametrophic guild.Consequently,throughthisstudy,NGSmethodsilluminatedmechanismsbehindthelargediversityofco-existingherbivorousmammalspecies observedinAfricansavannas.

Here,weusedNGStechniquestoresolvethetrophicinteractionsina communityofcarabidbeetlesinhabitingEuropeanarablelandscapes.These beetlessignificantlycontributetothebiologicalcontrolofpests(Kromp, 1999)buttheircontributionisunpredictablegiventheirbroaddietspectrum including alternativepreyssuchasothernaturalpestenemies.WeusedNGS approachinordertoinvestigatechangesincarabiddietamong14common arablespeciesbyanalyzingthepreyDNAcontainedintheirguts.Thecarabidbeetlesweresampledinsixarablefieldsintwodifferentagroecosystems inBrittany,France.Tocoverthewholecarabiddietspectrum,fourbarcode geneswerecombined,includingmitochondrial16SandCOIforcharacterizinganimalprey(Bienertetal.,2012;DeBarbaetal.,2014)andthechloroplast trnLfordetectingconsumedplantspecies(Taberletetal.,2007).We obtained bipartiteecologicalnetworksshowinganextensivedegreeofniche overlappingbetweencarabidspecies(Fig.3),confirmingtheirgeneralist feeding behaviour.TheuseofNGSalsoallowedusforthefirsttimeto quantifycarabidcommunitycontributiontoecosystemservices(theconsumptionofseveralanimalandplantpestspecies)anddis-services(theconsumptionofotherservice-providingorganisms)(Fig.4).Thesefindings suggest thatimportantecologicalfunctionsaspestregulationandintraguild predationmaynotbeassociatedwiththeidentityofparticularspeciesbutare