1

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2018

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

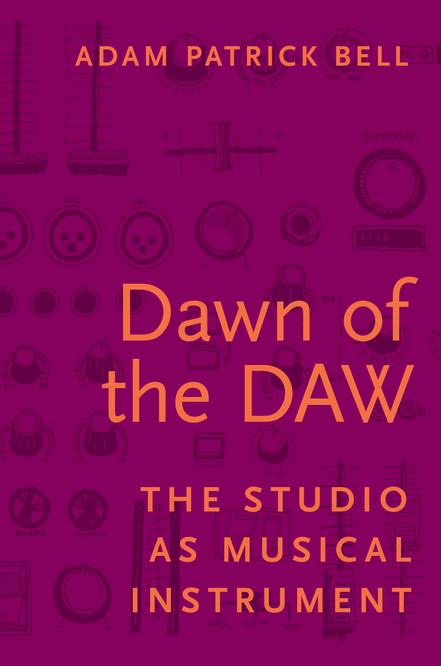

Names: Bell, Adam Patrick, author.

Title: Dawn of the DAW : the studio as musical instrument / Adam Patrick Bell.

Description: New York : Oxford University Press, [2018] |

Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017025068 (print) | LCCN 2017034672 (ebook) |

ISBN 9780190296629 (updf) | ISBN 9780190296636 (epub) | ISBN 9780190296605 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780190296612 (pbk : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Sound recordings—Production and direction. | Popular music—Production and direction.

Classification: LCC ML3790 (ebook) | LCC ML3790 .B33 2018 (print) | DDC 781.49—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017025068

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Paperback printed by WebCom, Inc., Canada

Hardback printed by Bridgeport National Bindery, Inc., United States of America

Thanks, libraries

I could learn audio technology. But where?

I’d start at home.

Grandmaster Flash

Preface xiii

Part I DO-IT-YOURSELF

1. A History of DIY Recording: Striving for Self-Sufficiency 3

The Difficulty of Defining DIY 3

DIY Recording Before Records 5

Tinfoil Revolutions: The First DIY Audio Recording 6

Mechanical Recording (Pre-1925) 8

The Electrical Era (Post-1925) 10

Les Paul’s Legacy of Overdubbing 11

Les Paul and the Tale of Tape (Post-1945) 12

Craft-Union Mode: 30th Street Studio 14

DIY Recording Post-1945: Sticking to the Tape Mentality 16

The Escalating Expenses of Equipment and the DIY Hi-Fi/Lo-Fi Dichotomy 18

DIVIDE-AND-ISOLATE 19

DIY HI-FI AND THE MULTITRACK REEL-TO-REEL TAPE RECORDER 22

DIY LO-FI AND THE MULTITRACK CASSETTE TAPE RECORDER 24

DIGITAL DIY: ADAT 26

Space-Less Studios: Dawn of the DAW (1990–Present) 27

Tracking the Twenty-First-Century DIY-er 29

2. The Studio: Instrument of the Producer 31

What Is a Producer? 31

Instrumentality: The Studio as Musical Instrument 33

Using the Studio as a Musical Instrument with Others 37

EARLY INCARNATIONS OF USING THE STUDIO AS A MUSICAL INSTRUMENT: ELVIS, LEIBER AND STOLLER, AND ALDON MUSIC 38

PHIL SPECTOR’S “WALL OF SOUND” 40

BRIAN WILSON AND THE BEACH BOYS’ SOUND 41

BERRY GORDY AND THE MOTOWN SOUND 44

THE JOE MEEK SOUND 46

Producing Without Producers 47

PRODUCED, ARRANGED, COMPOSED, AND PERFORMED BY PRINCE 50

BRIAN ENO AND IN-STUDIO COMPOSITION 51

HAPPY ACCIDENT #1: DUB AND ITS LEGACY OF PRIVILEGING TIMBRE IN PRODUCTION 54 TWEAKING TIMBRES 55

HAPPY ACCIDENT #2: HIP-HOP AND ITS SAMPLING LEGACY 58

The Contemporary Collaborative Producer: Max Martin 63

Different But the Same: Conclusions 67

Part II MADE IN BROOKLYN

Brooklyn: The Cultural Capital of DIY 71

3. Track 1: Michael 75

The Car Stereo Classroom: Learning History 76

CASSETTE CREATIVITY SINCE 1977: SELF-LED EXPLORATIONS IN OVERDUBBING 77

GOING CLASSICAL 78

GOING ELECTRIC AND DIGITAL 80

THE SKEUOMORPHIC ADVANTAGE: NEW TECHNOLOGIES, OLD CONCEPTS 83

On the Road . . . Again 85

Alone at the Kitchen Table: Learning Ableton 86

EXPLETIVES! FIRST ENCOUNTERS WITH ABLETON 87 READY, AIM, MISFIRE: CLICKS OF INTENT 89

THE TIMBRE TRAIL: TWEAKING SOUNDS 92

Lonely Learning: Conclusions 95

4. Track 2: Tara 97

From Scoring Points to Scoring Films: Learning Background 97

“I JUST LEARNED AS I HAD TO”: KARAOKE COMPOSITION AND REFLEXIVE RECORDING WITH LOGIC 98

Walking and Writing: Distinguishing the Song from the Recording 101

Packing Blankets and Piano Tuners: Converting the Home to Studio 102

Preparation (Saturday and Monday Morning) 102

HOME STUDIO HEADACHES 103

Hypercritical: In Pursuit of the Pristine Piano Performance (Monday Afternoon, Tuesday, and Wednesday) 105

FINDING FAULTS WITH FELIX 107

Recording the Piano for “Chesterfield” (Wednesday) 108

“TRAINS AND STUFF”: BATTLING ENVIRONMENTAL NOISE 111

FELIX AS PRODUCER? DEFINING ROLES IN THE RECORDING PROCESS 111

Technical Difficulties (Thursday) 113

Manufacturing Vocal Perfection: Repeated Takes and Comping (Friday) 114

TECHNICAL DETAILS 116

SELF-CONSCIOUSNESS IN RECORDING 116

“GOTTA HIT THAT”: SINGING PERFECTION 117

Comping (Saturday) 117

Ongoing: Shopping for a Mixer 121

To Be Continued: Conclusions 123

5. Track 3: Tyler 125

“Just Learned It From Doing It”: Learning History 125

“I WOULD GET TOGETHER WITH MYSELF”: MAKING MUSIC WITH ACID PRO 126

TECHNICAL TANGENT #1: MICROPHONE MATTERS 127

“I LEARNED THE HARD WAY”: SELF-TEACHING WITH DAWS 129

The Cartographic Composer: Mapping a Musical Existence 130

AUTODIDACTICISM AND ABLETON LIVE 132

A Guided Tour Through Tyler’s Bedroom Studio 133

TECHNICAL TANGENT #2: MIXING MATTERS 134

STEMS 136

The Apple Doesn’t Fall Far from the Social Network: Growing a Fictional Family Tree 137

SINGING ROBOTS 139

Audio Avatars: Otter, Sumac, and Totem 141

“THIS IS ME WATCHING ME TALKING ABOUT ME”: STIMULATED RECALL 142

EDITING MIDI 143

EQUALIZING BEATS 145

MAKING LOOPS 146

SHIFTING PITCH 147

“IF I CAN GET MYSELF FEELING GOOD ABOUT IT”: REFLEXIVE LISTENING 148

“AND THAT’S IT FOR NOW”: CONCLUDING THE SESSION 150

“Technology is the Reason”: Conclusions 150

6. Track 4: Jimmy 153

From Scratching to Picking: Learning History 155

“I JUST FOUND IT SO HARD”: LEARNING TO PLAY THE GUITAR 157

THREE HOURS A DAY: PRACTICE 158

“IT WAS NEVER, NEVER, NEVER SERIOUS”: LEARNING THE STUDIO BY OSMOSIS 159

“I Woke Up With the Melody”: The Making of “Lost and Found” 160

“EVERY DAY’S A STRUGGLE”: WRITING LYRICS 161

“IT JUST HAPPENS”: RECORDING = SONGWRITING 162

FINGER DRUMMING 163

TRACKING, LAYERING, AND TWEAKING GUITARS 164

DO IT AGAIN: LAYERING VOCALS 166

“Me and Him Have This Synergy”: Mixing with Bill 167

ANALOG VERSUS DIGITAL ACCORDING TO JIMMY 169

GETTING GUITAR SOUNDS: EQUALIZING AND COMPRESSING 170

“I NEVER THOUGHT I WOULD BE A SINGER”: VOCAL DOUBLING AND PROCESSING THE VOICE 173

FINAL MIX? 174

Recording as Second Nature: Conclusions 175

Part III LEARNING PRODUCING | PRODUCING LEARNING

Going Green: DIY Recording and Informal Learning Strategies 180

7. Mixing the Multitrack: Cross-Case Analyses 185

Conceptualizing the Multiple Case Study as a Multitrack Recording 185

Classifying DIY Studios 186

DIA STUDIOS 186

DIWO STUDIOS 188

Music-Making Models and Digitally Afforded Techniques 189

THE THIRD DIMENSION: BREAKING FROM THE HORIZONTAL AND VERTICAL PLANES 190

KARAOKE COMPOSITION AND REFLEXIVE RECORDING 191

PRESET CULTURE 192

UNDO THE UNDUE 193

Producer Pedagogies: Acquiring Skills and Know-How 193

AURAL EMULATION 194

PEER-GUIDED LEARNING 195

SELF-TEACHING 195

TAPE TRAVAILS 195

DOMAIN OF THE DAW 196

IMMERSIVE LEARNING AND HOLISTIC LEARNING 197

Summing the Tracks: Conclusions 198

8. Mastering the Multitrack: Conclusions 199

Implications for Music Education 199

BY-PROCESSES: TACIT LEARNING 199

MAKING WAVES: MUSIC-INVENTING 202

FORGED WITH ONES AND ZEROES: DIGITAL AUDIO MUSIC-MAKING TOOLS 203

TRIAL-AND-ERROR LEARNING: A NEW SPIN ON AN OLD FAVORITE 204

SONG-MAKERS: MAKING AS LEARNING 206

The Les Paul Legacy of the Producer 207

Bibliography 209 Index 221

Preface

Home Recording Revelations

I was fifteen years old when I first became skeptical that my favorite album was a compilation of real-time performances. Up until this time I credulously believed that this music, which bleated daily through my earbuds, was the byproduct of talented and practiced musicians collaborating in a studio to commit their best performances to permanence. I knew that microphones were involved in the recording process, and that there was usually a man (often with a cigarette dangling from his mouth) sitting behind a big board of lights and knobs who was obliged to utter catchphrases such as “Let’s take it from the top” and “We’re rolling.”

My favorite album during this time was by a four-piece band whose roles were listed on the back cover as follows:

• guitar, vocals

• vocals, guitar

• bass, vocals

• drums

Whenever I listened to this album, I pictured the band playing together in a recording studio, resembling what Geoffrey Stokes describes as the typical recording processes of rock and roll in the mid-1950s and early 1960s:

Recording was a relatively simple process in which a band lined up in front of microphones, each one controlled for volume from the control booth, and played their music. Generally it went right from the microphones to the final tape . . . when the recording session was over, the record was finished.1

1 Stokes, Star-Making Machinery, 136.

With each passing play audiotape gradually erodes, and paralleling this reality, my adolescent illusion of the studio recording as a real-time event began to disintegrate as I studied the guitar parts of my favorite album. With only two guitarists in the band, how was it possible that they played three different and distinct guitar parts simultaneously? I deduced that either a ringer was enlisted—a mystery third guitarist—or some kind of recording wizardry was invoked. Thumbing through my local library’s card catalogue in search of literature on audio recording proved to be a fruitless endeavor, and the “information superhighway” I had heard rumblings about had yet to make a detour to my rural hometown. Lacking the informational resources to answer my query, I retreated to the basement and took matters into my own hands.

Armed with a guitar, two tape recorders, and two audiocassettes, I devised my battle plan to create an audio illusion all my own. I commenced my experiment by pressing the red record button on one tape recorder and proceeded to play a four-chord progression that I repeated for a couple of minutes until the monotony of this exercise begged a quick cadence. I stopped the recording and rewound the tape to the beginning. On the second tape recorder I pressed record, and then pressed play on the first tape recorder. The rhythm guitar part that I had just finished recording now played the role of rhythmic accompaniment; I joined in on the jam by improvising a guitar solo along with it, all of which was recorded by the second tape recorder. What I stumbled upon was a crude form of overdubbing. It forever transformed my musical practices, aiding me in developing my instrumental skills and songwriting ideas. Ignorant of the history of recorded music and oblivious to the existence of multitrack tape recorders, I did not realize one person could play multiple parts on a recording, and that the technology to make this possible had existed for more than half of a century. By the mid-1960s the recording process had changed drastically in popular music, with musicians harnessing recording technology to move the conception of recording beyond that of an audio snapshot capturing a moment in time. Referencing the increasingly elaborate studio productions of the Beach Boys, Virgil Moorefield writes:

Already in 1966, then, the composer, arranger, and producer are melded into one person . . . Brian Wilson was at the controls himself, making onthe-spot decisions about notes, articulation, timbre, and so on. He was effectively composing at the mixing board and using the studio as a musical instrument.2

Since the mid-1960s, most recorded music has not been made by a group of people playing together in the same room at the same time. Instead, like Brian Wilson,

2 Moorefield, The Producer as Composer, 19.

musicians have used the studio as a musical instrument, either working alone,3 or in teams.4

Digital DIY-er

Shuffling forward a few years to the more digitally dependent musical milieu of the twenty-first century, my early adulthood years coincided with a critical period of transition in the music-recording industry: digital technologies were quickly usurping their analog predecessors. This change trickled down to the consumer, giving me access to similar recording technology. A fifty-dollar computer program that I purchased at a local mall afforded me to overdub as many as sixteen tracks, opening the portal to a new incarnation of the one-man band. By routing a few inexpensive Radio Shack microphones to my computer through a battered mixing console acquired from a thrift shop, I patched together a humble recording studio of my own. In my parent’s basement, I diligently recorded myself track-by-track playing drums, bass, and guitar to shape the foundations for my not-so-original pop songs. My recordings were not intended for others to listen to; rather they served as sonic sketches, an aural alternative to writing down musical ideas with pencil and paper. As I developed my recording skills in tandem with my musical skills, what started as a hobby evolved into a more serious endeavor. Aside from the skimpy manual that accompanied the music-recording software, I had no form of instruction. My music education took place outside of the classroom, after school, and consisted of a self-directed approach to making music with recording technology. I learned to use the studio as a musical instrument by teaching myself, much of which entailed a trial-and-error approach.

Music Education and Recording

Researchers in music education,5 and popular music,6 have opined that recordings constitute the primary texts from which popular musicians learn.7 For example, Susan McClary and Robert Walser assert: “What popular music has instead of the score is, of course, recorded performance—the thing itself, completely fleshed

3 See for example Bell, “Trial-by-Fire”; Butler, Playing with Something That Runs; Schloss, Making Beats; Rambarran, “DJ Hit That Button.”

4 See for example Hennion, “The Production of Success”; Seabrook, The Song Machine; Warner, Pop Music.

5 See for example Campbell, “Of Garage Bands and Song-Getting”; Green, How Popular Musicians Learn; Jaffurs, “The Impact of Informal Music Learning Practices in the Classroom.”

6 See for example Bennett, On Becoming a Rock Musician; Schwartz, “Writing Jimi.”

7 This section paraphrases parts of Bell, “The Process of Production | The Production of Process.”

out with all its gestures and nuances intact.”8 “Learn by listening to and copying recordings” is the second tenet of Lucy Green’s Music, Informal Learning, and the School: A New Classroom Pedagogy, a model of popular music pedagogy that has been hugely influential on the field of music education.9 It is undoubtedly true that popular musicians learn from recordings, but this is not the complete picture because popular musicians also learn by making recordings. This book aims to shed some light on the making and learning processes entailed in recording. Understanding how music-recording processes work can help music educators to facilitate learning experiences that reflect this important aspect of how popular musicians learn.

To the credit of the field, music educators have written about using the studio as a musical instrument, at least inadvertently, since the late 1960s.10 For example, in 1970 John Paynter and Peter Aston advocated using tape recorders to “make music,” recognizing the technology’s potential to not only record but to edit, make loops (literally), shift pitches via speed changes, layer sounds, and play sounds backward.11 Under the umbrella of “composition,” several music education researchers investigated the music-making process with computers,12 all of which resemble the practice of using the studio as a musical instrument. More recent studies have reported on music-making and learning practices in which studio technology serves as the instrument, occurring in a broad range of formal and informal learning settings.13 Despite the significance of these contributions to our understanding of the studio as instrument in music education, the practices of production that typify how popular music is made remain largely absent in popular music pedagogies. Music education needs to espouse the processes of recording as opposed to the products of recording, and focus on how popular music is made to create pedagogies that are more reflective of real world practices.

8 McClary and Walser, “Start Making Sense!,” 282.

9 In a review of eighty-one articles from 1978 to 2010 related to popular music pedagogy, Roger Mantie reported that over half of these cited Lucy Green. See his “A Comparison of ‘Popular Music Pedagogy’ Discourses.”

10 See for example Ellis, “Musique Concrète at Home”; Ernst, “So You Can’t Afford an Electronic Studio?”

11 Paynter and Aston, Sound and Silence, 134.

12 See for example Bamberger, “In Search of a Tune”; Folkestad, Hargreaves, and Lindström, “Compositional Strategies in Computer-Based Music Making”; Hickey, “The Computer as a Tool in Creative Music Making”; Stauffer, “Composing with Computers”; Wilson and Wales, “An Exploration of Children’s Musical Compositions.”

13 See for example Egolf, “Learning Processes of Electronic Dance Music Club DJs”; Finney, “Music Education as Identity Project in a World of Electronic Desires”; King, “Collaborative Learning in the Music Studio”; Lebler, “Popular Music Pedagogy”; Lebler and Weston, “Staying in Sync”; Mellor, “Creativity, Originality, Identity”; Tobias, “Composing, Songwriting, and Producing”; Tobias, “Crossfading Music Education.”

A History of DIY Recording

Striving for Self- Sufficiency

The Difficulty of Defining DIY

DIY. Do- it-yourself. In the context of recorded music, what does it mean? 1 For some, DIY is the story of independent distribution, embodied by entrepreneurs like Leonard Chess, 2 Berry Gordy, 3 and Rick Hall, 4 stocking their vehicles’ trunks with records and driving them to radio DJs and stores to promote their respective stables of artists. Perhaps no one in the history of music distribution has been more DIY than Ian MacKaye, who founded Dischord Records and with his peers put together the labels’ first ten thousand records by hand. 5 The determination to distribute music— exemplified by Lookout! Records’ Chris Applegren and Patrick Hynes pushing boxes of seven- inch records on their skateboards through the turnstiles of the San Francisco transit system— is a hallmark of the DIY- er. 6 For others DIY is about an aesthetic, a quality of sound that signifies an authenticity that is void in the recordings disseminating from professional recording studios. R. Stevie Moore, the “Godfather of Home Recording,” who is reported to have produced and distributed over four hundred albums, 7 “celebrated the unburnished, the intimate, the vulnerable, and the deranged.” 8 Oftentimes such an aesthetic is associated with a conception of

1 Parts of this chapter were first published in Bell, “DIY Recreational Recording as Music Making.”

2 Cohen, Record Men, 64.

3 Posner, Motown, 36.

4 Gillett, Making Tracks, 204.

5 Cook with McCaughan and Balance, Our Noise, 6.

6 Boulware and Tudor, Gimme Something Better, 330.

7 Carson, “R. Stevie Moore.”

8 Ingram, “Here Comes the Flood.”

what constitutes a professional studio and working in opposition to it, such as these New York- based examples:

• Mantronix recording The Album (1985) in Al Cohen Studio, an apartment in the Chelsea Hotel.9

• Marley Marl producing members of the Juice Crew in his “House of Hits,” which was the living room in his sister’s Queensbridge apartment.10

• Russell Simmons and Rick Rubin cutting LL Cool J’s “I Need a Beat” in Rubin’s New York University dorm room.11

• Vampire Weekend recording parts of their debut album in the music rooms of Columbia University.12

The sound, the space, the selling, and sharing; these are all critical components of what constitutes DIY, but for the purposes of this book, when DIY is invoked it refers to making music, specifically with a focus on how music is made in the recording process and the learning that occurs therein. The history of DIY recording that I present in this chapter is a purposefully skewed one. While it is important to know what people use to make music, more emphasis is placed on how recording as a music-making practice is conceptualized and performed. Therefore, this is a story about ease of access and ease of use, the two most critical conditions in determining whether or not a practice can be self-sufficient, which is the essence of DIY. At present, the digital audio workstation (DAW) is the bedrock of music production, DIY or otherwise. DAW is a generic software categorization that has evolved since its origins as simply an audio editing application that ran on specialized workstation computers. Most DAWs now share in common the capability to sequence, record, and mix music, but increasingly can be played using software-based synthesizers that emulate existing instruments or create new tones and timbres with no existing referent. As a tech-dependent music-making society, have we adapted our recording practices in parallel, if at all, with the development of our recording technologies? In this first chapter, I aim to shine a light on DIY practices since the inception of recording itself, and trace its path to the present. What ought to be evident is that relatively soon into the history of recording, an industry is established and DIY practices coexist in a world with professional protocols, conventions, and equipment. DIY-ers and professionals inform and influence each other, and at times distinguishing one from another is a difficult task. I attribute “professional” to the music industry, meaning that professional practices exist to produce recordings to be commodities. DIY covers the spectrum, as some DIY-ers set out to

9 Coleman, Check the Technique Volume 2, 351.

10 Gonzales, “The Juice Crew,” 103.

11 Considine, “The Big Willies,” 155.

12 Eells, “Vampire Weekend.”

make money, while others simply see recording as recreation. What these DIY-ers share in common is a desire to be self-sufficient; to engage in recording as musicmaking. “Recording,” as this history will demonstrate, is a moving target, and over time comes to mean increasingly more than the literal act of recording sound to a medium. As the acts associated with recording change and evolve, so too do the roles of the people that engage with these practices. The music-making and learning practices of the contemporary DIY-ers profiled in this book are not the result of a twenty-first century DIY recording revolution; rather, they are exemplary of a DIY recording evolution that started before audio existed.

DIY Recording Before Records

It was not until 1877 that Thomas Edison succeeded in playing back a recording of himself, but many of the concepts present in the modern DAW predate the phonograph by hundreds of years. By extension, DIY recording practices predate audio recording itself. David Bowers details that there are historical records dating to the era of 1500 to 1800 of automatic musical instruments in Europe, typically reserved for royalty, such as flute-players and mechanical birds. By the early 1800s, music boxes that played melodies using tuned steel combs were being produced by Swiss and German workshops.13 Handel, C. P. E. Bach, Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven all composed for small self-playing organs,14 which suggests that they were not just composing for this medium, but programming it, too. This last point is particularly pertinent to the development of the DIY studio because long before the arrival of audio recording, composers were bypassing performing musicians to interpret and play their works in favor of a more direct and self-sufficient approach.

Even more intriguing from the history of Bowers’ automatic instruments is the evidence to support the theory that the drum machine predates the drum set. By the mid-nineteenth century tuned bells and drums were added to music boxes,15 which effectively meant that a drum pattern could be programmed. Furthermore, there is evidence of miniature drum machines—essentially a trap kit triggered by a small scroll of paper akin to a piano roll—in existence in the early twentieth century,16 which is around the same time the modern trap kit began to take shape as an instrument unto itself.17 But of all the marvels of automatic mechanical music technology, the most complex operations were afforded by the player piano, which for a time rivaled audio recording in the early twentieth century as the preferred

13 Bowers, Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments, 10.

14 Hocker, “My Soul is in the Machine,” 84.

15 Bowers, Encyclopedia of Automatic Musical Instruments, 29.

16 Ibid., 749.

17 Avanti, “Black Musics, Technology, and Modernity.”

method by performers to record the piano. The significance of these perforatedscroll-dependent instruments is that in theory, one could independently record and reproduce their own musical performance. Making a DIY recording was possible before “recordings” in the modern sense existed, exemplifying that “the growth, persistence in our culture, and technological improvement of sound recording reflect its evolutionary, not revolutionary nature.”18

Tinfoil Revolutions: The First DIY Audio Recording

The first audio recording that could be played back was a DIY job by Thomas Edison. This inaugural phonograph recording from 1877 was a spoken rendition of “Mary Had a Little Lamb.”19 With this sonic selfie, Edison set a precedent that you could record yourself. Initially, Edison did not envision music recording as the phonograph’s primary purpose; he had other designs in mind than entertainment, such as office dictation.20 Nevertheless in 1878, listing potential uses of the phonograph, Edison included recording music:

The phonograph will undoubtedly be liberally devoted to music. A song sung on the phonograph is reproduced with marvelous accuracy and power. Thus a friend may in a morning-call sing us a song which shall delight an evening company, etc. As a musical teacher it will be used to enable one to master a new air, the child to form its first songs, or to sing him to sleep.21

Although the earliest phonographs produced were equipped to record, low public demand for this feature in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries pushed the phonograph and its competing devices toward being used solely for sound reproduction. Up until approximately 1900, the phonograph could both record and reproduce, and the manufacturers “expected their customers to make their own recordings.”22 One such example of DIY recording during this era is presented in How We Gave a Phonograph Party, distributed by the National Phonography Company in 1899.23 This party is depicted as a fun-filled evening, with anecdotes such as: “The most effective records we made during the entire evening were two

18 Jones, Rock Formation, 14.

19 Digital restorations of similar tinfoil recordings from 1878 reveal that these recordings were quite noisy and distorted, making the sound source, such as the voice in this case, difficult to discern.

20 Morton, Sound Recording, 18.

21 Cited in Taylor, Katz, and Grajeda, Music, Sound, and Technology in America, 35.

22 Morton, Off the Record, 14.

23 Reproduced in Taylor, Katz, and Grajeda, Music, Sound, and Technology in America

chorus records. All stood close together in a bunch about three feet from the horn and sang ‘Marching through Georgia’ and it came out fine. Our success lead us to try another ‘Onward Christian Soldiers’ and it was every bit as good.”24

During the phonograph’s infancy, people could record themselves. Although the role of “recordist” existed in professional recording studios, in domestic life the people operating the recording equipment were the same people performing for it. Recording in this context was a self-sufficient process that was intended to be fun. Despite some critics’ concerns that recording technology would replace recreational music-making, “in good part it [music-making] flourished in response to the possibilities of these technologies.”25 Emulating Edison—most likely unknowingly— people self-produced their own recordings in their homes decades before “home recording” became a household term.

Based on these accounts it seemed that DIY recording was off to a formidable start in the twentieth century, but with Emile Berliner’s disc-based gramophone design supplanting Edison’s cylinder-based phonograph system—due to the fact that it was easier to mass-produce discs than cylinders—came a major conceptual shift. The inability to record on discs

introduced a structural and social division between making a recording and listening to it. With Edison’s design, access to one assumed access to the other as well; sound recording was something people could do. With Berliner’s design, a wedge was driven between production and consumption; sound recording was something people could listen to. 26

As a consequence of this conceptual shift, “recordings would be made solely by manufacturers, not by consumers.”27 The act of recording was no longer participatory, it was proprietary. The story of DIY recording does not end in the early twentieth century with the demise of recording cylinders, but it does drop off the radar of most accounts of the history of recording, only to resurface mid-century with the advent of tape recording. In part, DIY recording’s absence from the annals of recording history can be explained by the overshadowing presence of the professionalization of recording—what would eventually come to be known as audio engineering. This was a critical juncture: the beginning of the parsing of the technological from the musical, which over time came to be further entrenched as recording practices evolved in tandem with the music industry. To understand DIY recording in its current state, it must be contextualized within the broader culture and history of sound recording, commencing with the mechanical era.

24 Ibid., 51.

25 Katz, “The Amateur in the Age of Mechanical Music,” 460.

26 Suisman, Selling Sounds, 5.

27 Morton, Sound Recording, 32.