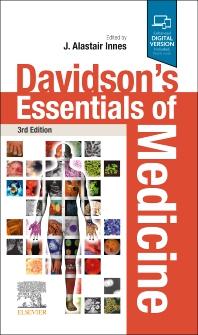

Contributors to Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine, 23rd Edition

The core of this book is based on the contents of Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine, with material extracted and re-edited to make a uniform presentation to suit the format of this book. Although some chapters and topics have, by necessity, been cut or substantially edited, contributors of all chapters drawn upon have been acknowledged here in recognition of their input into the totality of the parent textbook.

Brian J Angus BSc, DTM&H, FRCP, MD, FFTM(Glas)

Associate Professor, Nuffield Department of Medicine, University of Oxford, UK

Quentin M Anstee BSc(Hons), PhD, MRCP

Senior Lecturer, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne; Honorary Consultant Hepatologist, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Leslie Burnett MBBS, PhD, FRCPA, FHGSA

Medical Director, Garvan Institute of Medical Research, Sydney; Conjoint Professor, St Vincent’s Clinical School, Faculty of Medicine, University of New South Wales; Honorary Professor in Pathology and Genetic Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Sydney Medical School; Honorary Associate of the School of Information Technologies, University of Sydney, Australia

Mark Byers OBE, MRCGP, MCEM, MFSEM, DA(UK)

General Practitioner, Ministry of Defence, Royal Centre for Defence Medicine, University Hospitals Birmingham, UK

Harry Campbell MD, FRCPE, FFPH, FRSE

Professor of Genetic Epidemiology and Public Health, Centre for Global Health Research, Usher Institute of Population Health Sciences and Informatics, University of Edinburgh, UK

Gavin PR Clunie BSc, MD, FRCP

Consultant Rheumatologist and Metabolic Bone Physician, Cambridge University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge, UK

Lesley A Colvin BSc, FRCA, PhD, FRCPE, FFPMRCA

Consultant, Department of Anaesthesia, Critical Care and Pain Medicine, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh; Honorary Professor in Anaesthesia and Pain Medicine, University of Edinburgh, UK

Bryan Conway MB, MRCP, PhD

Senior Lecturer, Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh; Honorary Consultant Nephrologist, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, UK

Nicola Cooper FAcadMEd, FRCPE, FRACP

Consultant Physician, Derby Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Derby; Honorary Clinical Associate Professor, Division of Medical Sciences and Graduate Entry Medicine, University of Nottingham, UK

Alison L Cracknell FRCP

Consultant, Medicine for Older People, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Leeds; Honorary Clinical Associate Professor, University of Leeds, UK

Dominic J Culligan BSc, MD, FRCP, FRCPath

Consultant Haematologist, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, Aberdeen; Honorary Senior Lecturer, University of Aberdeen, UK

Graham G Dark FRCP, FHEA

Senior Lecturer in Medical Oncology and Cancer Education, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Richard J Davenport DM, FRCPE, BMedSci

Consultant Neurologist, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh and Western General Hospital, Edinburgh; Honorary Senior Lecturer, University of Edinburgh, UK

David H Dockrell MD, FRCPI, FRCPG, FACP

Professor of Infection Medicine, Medical Research Council/University of Edinburgh Centre for Inflammation Research, University of Edinburgh, UK

Emad El-Omar BSc(Hons), MD(Hons), FRCPE, FRSE

Professor of Medicine, St George and Sutherland Clinical School, University of New South Wales, Sydney, Australia

Marie Fallon MD, FRCP

St Columba’s Hospice Chair of Palliative Medicine, University of Edinburgh, UK

David R FitzPatrick MD, FRCPE

Professor, Medical Research Council Human Genetics Unit, Institute of Genetics and Molecular Medicine, University of Edinburgh, UK

Neil R Grubb MD, FRCP

Consultant in Cardiology, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh; Honorary Senior Lecturer in Cardiovascular Sciences, University of Edinburgh, UK

Sally H Ibbotson BSc(Hons), MD(with commendation), FRCPE

Professor of Dermatology, University of Dundee, UK

J Alastair Innes BSc, PhD, FRCPE

Consultant, Respiratory Unit, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh; Honorary Reader in Respiratory Medicine, University of Edinburgh, UK

Sara J Jenks BSc(Hons), MRCP, FRCPath

Consultant in Metabolic Medicine, Department of Clinical Biochemistry, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, UK

Sarah L Johnston FCRP, FRCPath

Consultant Immunologist, Department of Immunology and Immunogenetics, North Bristol NHS Trust, Bristol, UK

David EJ Jones MA, BM, PhD, FRCP

Professor of Liver Immunology, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne; Consultant Hepatologist, Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Peter Langhorne PhD, FRCPG

Professor of Stroke Care, Institute of Cardiovascular and Medical Sciences, University of Glasgow, UK

Stephen M Lawrie MD(Hons), FRCPsych, FRCPE(Hon)

Professor of Psychiatry, University of Edinburgh, UK

John Paul Leach MD, FRCPG, FRCPE

Consultant Neurologist, Institute of Neuroscience, Southern General Hospital, Glasgow; Head of Undergraduate Medicine and Honorary Associate Clinical Professor, University of Glasgow, UK

Gary Maartens MBChB, FCP(SA), MMed

Professor of Medicine, University of Cape Town, South Africa

Lucy Mackillop BM, MA(Oxon), FRCP

Consultant Obstetric Physician, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Oxford; Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer, Nuffield Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, University of Oxford, UK

Michael J MacMahon FRCA, FICM, EDIC

Consultant in Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, Victoria Hospital, Kirkcaldy, UK

Rebecca Mann BMedSci MRCP, FRCPCh

Consultant Paediatrician, Taunton and Somerset NHS Foundation Trust, Taunton, UK

Lynn M Manson MD, FRCP, FRCPath

Consultant Haematologist, Scottish National Blood Transfusion Service, Edinburgh; Honorary Clinical Senior Lecturer, Department of Transfusion Medicine, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, UK

Sara E Marshall FRCP, FRCPath, PhD

Professor of Clinical Immunology, Medical Research Institute, University of Dundee, UK

Amanda Mather MBBS, FRACP, PhD

Renal Staff Specialist, Department of Renal Medicine, Royal North Shore Hospital, Sydney; Conjoint Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney, Australia

Simon R Maxwell BSc, MD, PhD, FRCP, FRCPE, FHEA

Professor of Pharmacology, Clinical Pharmacology Unit, University of Edinburgh, UK

David A McAllister MSc, MD, MRCP, MFPH

Wellcome Trust Intermediate Clinical Fellow and Beit Fellow, Senior Clinical Lecturer in Epidemiology, and Honorary Consultant in Public Health Medicine, University of Glasgow, UK

Rory J McCrimmon MD, FRCPE

Reader, Medical Research Institute, University of Dundee, UK

Mairi McLean MRCP, PhD

Senior Clinical Lecturer in Gastroenterology, School of Medicine, Medical Sciences and Nutrition, University of Aberdeen; Honorary Consultant Gastroenterologist, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, UK

Francesca EM Neuberger MRCP(UK)

Consultant Physician in Acute Medicine and Obstetric Medicine, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, UK

David E Newby BA, BSc(Hons), PhD, BM DM DSc, FMedSci, FRSE, FESC, FACC

British Heart Foundation John Wheatley Professor of Cardiology, British Heart Foundation Centre for Cardiovascular Science, University of Edinburgh, UK

John DC Newell-Price MA, PhD, FRCP

Reader in Endocrinology, Department of Human Metabolism, University of Sheffield, UK

John Olson MD, FRPCE, FRCOphth

Consultant Ophthalmic Physician, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary; Honorary Reader, University of Aberdeen, UK

Ewan R Pearson PhD, FRCPE

Clinical Reader, Medical Research Institute, University of Dundee, UK

Paul J Phelan BAO, MD, FRCPE

Consultant Nephrologist and Renal Transplant Physician, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh; Honorary Senior Lecturer, University of Edinburgh, UK

Stuart H Ralston MRCP, FMedSci, FRSE

Arthritis Research UK Professor of Rheumatology, University of Edinburgh; Honorary Consultant Rheumatologist, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Peter T Reid MD, FRCPE

Consultant Physician, Respiratory Medicine, Lothian University Hospitals, Edinburgh, UK

Jonathan AT Sandoe PhD, FRCPath

Associate Clinical Professor, University of Leeds, UK

Gordon R Scott BSc, FRCP

Consultant in Genitourinary Medicine, Chalmers Sexual Health Centre, Edinburgh, UK

Alan G Shand MD, FRCPE

Consultant Gastroenterologist, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh, UK

Robby M Steel MA, MD, FRCPsych

Consultant Liaison Psychiatrist, Department of Psychological Medicine, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh; Honorary (Clinical) Senior Lecturer, Department of Psychiatry, University of Edinburgh, UK

Grant D Stewart BSc(Hons), FRCSE(Urol), PhD

University Lecturer in Urological Surgery, Academic Urology Group, University of Cambridge; Honorary Consultant Urological Surgeon, Department of Urology, Addenbrooke’s Hospital, Cambridge; Honorary Senior Clinical Lecturer, University of Edinburgh, UK

Peter Stewart MBBS, FRACP, FRCPA, MBA

Associate Professor in Chemical Pathology, University of Sydney; Area Director of Clinical Biochemistry and Head of the Biochemistry Department, Royal Prince Alfred and Liverpool Hospitals, Sydney, Australia

Mark WJ Strachan BSc(Hons), MD, FRCPE

Consultant Endocrinologist, Metabolic Unit, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh; Honorary Professor, University of Edinburgh, UK

David R Sullivan MBBS, FRACP, FRCPA, FCSANZ

Clinical Associate Professor, Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney; Physician and Chemical Pathologist, Department of Clinical Biochemistry Royal Prince Alfred Hospital, Sydney, Australia

Shyam Sundar MD, FRCP(London), FAMS, FNASc, FASc, FNA

Professor of Medicine, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University, Varanasi, India

Victoria R Tallentire BSc(Hons), DipMedEd, MRCP, MD

Consultant Physician, Western General Hospital, Edinburgh; Honorary Senior Lecturer, University of Edinburgh, UK

Katrina Tatton-Brown BA, MD, FRCP(Paeds)

Consultant and Reader in Clinical Genetics and Genomic Education, South West Thames Regional Genetics Service, St George’s Universities Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK

Simon HL Thomas MD, FRCP, FRCPE

Professor of Cellular Medicine, Institute of Cellular Medicine, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK

Henry G Watson MD, FRCPE, FRCPath

Consultant Haematologist, Aberdeen Royal Infirmary, UK

Julian White MB, BS, MD, FACTM

Head of Toxinology, Women’s and Children’s Hospital, North Adelaide; Professor, University of Adelaide, Australia

John PH Wilding DM, FRCP

Professor of Medicine, Obesity and Endocrinology, University of Liverpool, UK

Miles D Witham PhD, FRCPE

Clinical Senior Lecturer in Ageing and Health, University of Dundee, UK

List of abbreviations

ABGs arterial blood gases

ACE angiotensin-converting enzyme

ACTH adrenocorticotrophic hormone

ADH antidiuretic hormone

AIDS acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

ANA antinuclear antibody

ANCA antineutrophil cytoplasmic autoantibody

ANF antinuclear factor

ANP atrial natriuretic peptide

APECED Autoimmune polyendocrinopathycandidiasis-ectodermal dystrophy

APS Antiphospholipid syndrome

APTT activated partial thromboplastin time

ARDS acute respiratory distress syndrome

ASO antistreptolysin O

AST aspartate aminotransferase

AXR abdominal X-ray

BCG Calmette–Guérin bacillus

BMI body mass index

BP blood pressure

CK creatine kinase

CNS central nervous system

CPAP continuous positive airways pressure

CRH corticotrophinreleasing hormone

CRP C-reactive protein

CSF cerebrospinal fluid

CT computed tomography/tomogram

CVP central venous pressure

CXR chest X-ray

DEXA dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry

DIC disseminated intravascular coagulation

DIDMOAD diabetes insipidus, diabetes mellitus, optic atrophy, deafness

dsDNA double-stranded deoxyribonucleic acid

DVT deep venous thrombosis

ECG electrocardiography/ electrocardiogram

ELISA enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

ERCP endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

ESR erythrocyte sedimentation rate

FBC full blood count

FDA Food and Drug Administration

FEV1/FVC forced expiratory volume in 1 sec/forced vital capacity

FFP fresh frozen plasma

5-HT 5-hydroxytryptamine; serotonin

FOB faecal occult blood

GI gastrointestinal

GMC General Medical Council

GU genitourinary

HDL high-density lipoprotein

HDU high-dependency unit

HIV human immunodeficiency virus

HLA human leucocyte antigen

HRT hormone replacement therapy

ICU intensive care unit

IL interleukin

IM intramuscular

INR International Normalised Ratio

IV intravenous

IVU intravenous urogram/ urography

JVP jugular venous pressure

LDH lactate dehydrogenase

LDL low-density lipoprotein

LFTs liver function tests

MRA magnetic resonance angiography

MRC Medical Research Council

MRCP magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

MRI magnetic resonance imaging

MRSA meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

MSU mid-stream sample of urine

NG nasogastric

NICE National Institute for Health and Care Excellence

NIV non-invasive ventilation

NSAID non-steroidal antiinflammatory drug

PA postero-anterior

PCR polymerase chain reaction

PE pulmonary embolism

PET positron emission tomography

PTH parathyroid hormone

RBC red blood count

RCT randomised controlled clinical trial

SPECT single-photon emission computed tomography

STI sexually transmitted infection

TB tuberculosis

TFTs thyroid function tests

TNF tumour necrosis factor

U&Es urea and electrolytes

USS ultrasound scan

VTE venous thromboembolism

WBC/WCC white blood/cell count

WHO World Health Organization

Clinical decision making

How doctors think, reason and make decisions is arguably their most critical skill. Knowledge is necessary, but not sufficient, for good safe care.

The problem of diagnostic error

It is estimated that the diagnosis is wrong in 10% to 15% of cases in many specialties, causing much preventable morbidity.

Diagnostic error has been defined as ‘a situation in which the clinician has all the information necessary to make the diagnosis but then makes the wrong diagnosis’. Root causes include:

• No fault—for example, rare or atypical presentation.

• System error—for example, results not available, poorly trained staff.

• Human cognitive error—for example, inadequate data gathering, errors in reasoning.

Clinical reasoning

‘Clinical reasoning’ describes the thinking and decision-making processes associated with clinical practice. Errors may occur because of lack of knowledge, misinterpretation of diagnostic tests and cognitive bias (e.g. accepting another’s diagnosis unquestioningly). Other key elements include patient-centred evidence-based medicine and shared decision making with patients and/or carers.

Clinical skills and decision making

Despite diagnostic technology, the history remains crucial; studies show that physicians make a diagnosis in 70% to 90% of cases from the history alone.

Additional knowledge is needed for correct interpretation of the history and examination. For example, students learn that meningitis presents with headache, fever and meningism (photophobia, nuchal rigidity). However, the frequency with which patients present with particular features and the diagnostic weight of each feature are important in clinical reasoning.

The likelihood ratio (LR) is the probability of a finding in someone with a disease (judged by a diagnostic standard, e.g. lumbar puncture in meningism) divided by the probability of that finding in someone without disease.

An LR greater than 1 increases the probability of disease; an LR of less than 1 reduces that probability. For example, in a person presenting with headache and fever, the clinical finding of nuchal rigidity (neck stiffness) may carry little diagnostic weight, because many patients with meningitis do not have classical signs of meningism (LR of around 1).

LRs do not determine the prior probability of disease, only how a single clinical finding changes it. Clinicians have to take all available information from the history and physical examination into account. If the prior probability is high, a clinical finding with an LR of 1 does not change this.

‘Evidence-based history and examination’ is a term used to describe how clinicians incorporate knowledge about the prevalence and diagnostic weight of clinical findings into the history and physical examination.

Use and interpretation of diagnostic tests

No diagnostic test is perfect. To correctly interpret test results requires understanding of the following factors:

Normal values

Many quantitative measurements in populations have a Gaussian or ‘normal’ distribution, in which the normal range is defined as that which includes 95% of the population (±2 SD around the mean). Because 2.5% of the normal population will be above, and 2.5% below the range, it is better described as the ‘reference range’ rather than the ‘normal range’.

Results in abnormal populations also have a Gaussian distribution, with a different mean and standard deviation, although sometimes there is overlap with the reference range. The greater the difference between the result and the limits of the reference range, the higher the chance of disease.

Clinical context can affect interpretation. For example, a normal PaCO2 in the context of a severe asthma attack indicates life-threatening asthma. A low ferritin level in a young menstruating woman is not considered to be pathological.

Factors other than disease that influence results

These include: • age • ethnicity • pregnancy • sex • technical factors (e.g., high K+ in haemolysed sample).

Operating characteristics

Tests may be affected or rendered nondiagnostic by: • Patient motivation and technique (e.g. spirometry) • Operator skill • Patient’s body habitus and clinical state (e.g. echocardiography) • Paroxysmal illness (e.g. normal EEG between fits in epilepsy) • The incidental discovery of a benign abnormality

Test results should always be interpreted in the light of the patient’s history and examination.

1.1 Sensitivity and specificity

Disease No disease

Positive test A B (True positive) (False positive)

Negative test C D (False negative) (True negative)

Sensitivity = A/(A+C) × 100

Specificity = D/(D+B) × 100

Sensitivity and specificity

Sensitivity is the ability to detect true positives; specificity is the ability to detect true negatives. Even a very good test with 95% sensitivity will miss 1 in 20 people with the disease. Every test therefore has ‘false positives’ and ‘false negatives’ (Box 1.1).

A very sensitive test detects most cases of disease but generates abnormal findings in healthy people. A negative result reliably excludes disease, but a positive result does not mean disease is present. Conversely, a very specific test may miss significant pathology, but can firmly establish the diagnosis if positive. Clinicians need to know the sensitivity and specificity of the tests they use.

In choosing how a test is used, there is a trade-off between sensitivity and specificity. This is illustrated by the receiver operating characteristic curve of the test (Fig. 1.1).

An extremely important concept is this: the probability that a person has a disease depends on both the pretest probability and the sensitivity and specificity of the test. In a patient whose history suggests a high pretest probability of disease, a normal test result does not exclude the condition, but in a low-probability patient, it makes it very unlikely. This principle is illustrated in Fig. 1.2.

Prevalence of disease

The prevalence of disease in the patient’s population subgroup should inform the doctor’s estimate of pretest probability. Prevalence also influences the chance that a positive test result indicates disease. Consider a test with a false- positive rate of 5% for a disease whose prevalence is 1:1000. If 1000 people are tested, there will be 51 positive results: 50 false positives and one true positive. The chance that a person found to have a positive result actually has the disease is only 1/51, or 2%.

Predictive values combine sensitivity, specificity and prevalence, allowing doctors to address the question: ‘What is the probability that a person with a positive test actually has the disease?’. This is illustrated in Box 1.2.

Sensitivity

Fig. 1.1 Receiver operating characteristic graph illustrating the trade- off between sensitivity and specificity for a given test. The curve is generated by ‘adjusting’ the cut- off values defining normal and abnormal results, calculating the effect on sensitivity and specificity and then plotting these against each other. The closer the curve lies to the top left- hand corner, the more useful the test. The red line illustrates a test with useful discriminant value, and the green line illustrates a less useful, poorly discriminant test.

Dealing with uncertainty

Clinicians must frequently deal with uncertainty. By expressing uncertainty as probability, new information from diagnostic tests can be incorporated more accurately. However, intuition and subjective estimates of probability can be unreliable.

Knowing the patient’s true state is often unnecessary in clinical decision making. The requirement for diagnostic certainty depends on the penalty for being wrong. Different situations require different levels of certainty before starting treatment. How we communicate uncertainty to patients will be discussed later in this chapter (p. 8).

The treatment threshold combines factors such as the risks of the test and the risks versus benefits of treatment. A less effective or high risk test increases the treatment threshold.

Cognitive biases

Human thinking and decision making are prone to error. Cognitive biases are subconscious errors that lead to inaccurate judgement and illogical interpretation of information.

Humans have two distinct types of processes when it comes to thinking and decision making: type 1 and type 2 thinking.

34.6% chance of having the disease if the test is negative

90% chance of having the disease before the test is done

Patient A

50% chance of having the disease before the test is done

5.6% chance of having the disease if the test is negative

Patient B

98.3% chance of having the disease if the test is positive

86.4% chance of having the disease if the test is positive

Fig. 1.2 The interpretation of a test result depends on the probability of the disease before the test is carried out. In the example shown, the test being carried out has a sensitivity of 95% and a specificity of 85%. Patient A has very characteristic clinical findings, which make the pretest probability of the condition for which the test is being used very high—estimated as 90%. Patient B has more equivocal findings, such that the pretest probability is estimated as only 50%. If the result in Patient A is negative, there is still a significant chance that he has the condition for which he is being tested; in Patient B, however, a negative result makes the diagnosis very unlikely.

Type 1 and type 2 thinking

Cognitive psychology identifies two distinct processes when it comes to decision making: intuitive (type 1) and analytical (type 2). This has been termed ‘dual process theory’. Box 1.3 explains this in more detail.

Psychologists estimate that we spend 95% of our daily lives engaged in type 1 thinking—the intuitive, fast, subconscious mode of decision making. Learning to drive involves moving from the deliberate, conscious, slow and effortful first lesson to the automatic, fast and effortless process of an experienced driver. The same applies to medical practice, and intuitive thinking is highly efficient in many circumstances; however, in others it is prone to error.

1.2 Predictive values:

‘What is the probability that a person with a positive test actually has the disease?’

Disease

No disease

Positive test A B

(True positive) (False positive)

Negative test C D (False negative) (True negative)

Positive predictive value = A/(A+B) × 100

Negative predictive value = D/(D+C) × 100

1.3 Type 1 and type 2 thinking

Type 1

Intuitive, heuristic (pattern recognition)

Automatic, subconscious

Fast, effortless

Low/variable reliability

Vulnerable to error

Highly affected by context

High emotional involvement

Low scientific rigour

Type 2

Analytical, systematic

Deliberate, conscious

Slow, effortful

High/consistent reliability

Less prone to error

Less affected by context

Low emotional involvement

High scientific rigour

Clinicians use both type 1 and type 2 thinking. When encountering a familiar problem, clinicians employ pattern recognition and reach a differential diagnosis quickly (type 1 thinking). When encountering a problem that is more complicated, they use a slower, systematic approach (type 2 thinking). Both types of thinking interplay—they are not mutually exclusive in the diagnostic process. Errors can occur in both type 1 and type 2 thinking; for example, people can apply the wrong rules or make errors in their application while using type 2 thinking. However, it has been argued that the common cognitive biases encountered in medicine tend to occur when clinicians are engaged in type 1 thinking.

Common cognitive biases in medicine

These include:

• Overconfidence bias—the tendency to believe we know more than we actually do • Availability bias—the likelihood of diagnosing recently seen conditions • Ascertainment bias—seeing what we expect to see • Confirmation bias—only looking for evidence to support a theory, not to refute it