The Climate Question: Natural Cycles, Human Impact, Future Outlook Eelco J. Rohling

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-climate-question-natural-cycleshuman-impact-future-outlook-eelco-j-rohling/

ebookmass.com

Orphic Tradition and the Birth of the Gods Dwayne A Meisner

https://ebookmass.com/product/orphic-tradition-and-the-birth-of-thegods-dwayne-a-meisner/

ebookmass.com

iPhone Portable Genius Paul Mcfedries

https://ebookmass.com/product/iphone-portable-genius-paul-mcfedries/

ebookmass.com

Gestão estratégica de pessoas: Evolução, teoria e crítica 1st Edition André Ofenhejm Mascarenhas

https://ebookmass.com/product/gestao-estrategica-de-pessoas-evolucaoteoria-e-critica-1st-edition-andre-ofenhejm-mascarenhas-2/

ebookmass.com

Handbook for Laboratory Safety Benjamin R. Sveinbjornsson

https://ebookmass.com/product/handbook-for-laboratory-safety-benjaminr-sveinbjornsson/

ebookmass.com

Textbook of Basic Nursing Eleventh Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/textbook-of-basic-nursing-eleventhedition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Cybersecurity in Humanities and Social Sciences

Cybersecurity Set coordinated by Daniel

Ventre

Cybersecurity in Humanities and Social Sciences

A Research Methods Approach

Edited by

Hugo Loiseau

Daniel Ventre

Hartmut Aden

First published 2020 in Great Britain and the United States by ISTE Ltd and John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, this publication may only be reproduced, stored or transmitted, in any form or by any means, with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction in accordance with the terms and licenses issued by the CLA. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside these terms should be sent to the publishers at the undermentioned address:

ISTE Ltd

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

27-37 St George’s Road 111 River Street London SW19 4EU Hoboken, NJ 07030

UK USA

www.iste.co.uk

www.wiley.com

© ISTE Ltd 2020

The rights of Hugo Loiseau, Daniel Ventre, Hartmut Aden to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted by them in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020935380

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A CIP record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978-1-78630-539-8

2.4.

2.4.3.

2.4.4.

2.5.

2.5.1.

2.5.2.

2.5.3.

Chapter 3. Cybersecurity and Data Protection – Research Strategies and Limitations in a Legal and Public Policy Perspective

Hartmut ADEN

3.1.

3.2.

3.2.1.

3.2.2.

3.3.

3.3.1.

3.3.2.

3.3.3.

3.4.

3.5.

Chapter

4.1.

4.2. Taxonomies of cyber-threats

4.3. The structure of this chapter

4.4. The significance of state-sponsored cyber-espionage

4.5. Research themes in state-sponsored cyber-espionage

4.6.

4.7. Research methodologies into state-sponsored cyber-espionage

4.8. Intellectual precision and objectivity in state-sponsored cyber-espionage research

4.9. Detecting state actors in cyber-espionage research.............

4.10. Identifying specific state actors in cyber-espionage research

4.11. Conclusion: researching a transformational

4.12.

Chapter

Michel DACOROGNA and Marie KRATZ

5.1.

5.2. The scientific approach to move from uncertainty to

5.3. Learning about the

5.4. Data

5.5. Statistical exploration on the various variables of the dataset

5.6. Univariate modeling for the relevant

5.7. Multivariate and dynamic

5.7.1.

5.7.2.

5.7.3.

5.8.

5.9.

Brett VAN NIEKERK and Trishana RAMLUCKAN

6.1.

6.2.

6.3. Researching

6.4. Qualitative

6.4.1.

6.4.2.

6.4.3.

6.4.4. Text

6.4.5.

6.5. An analysis

6.5.1.

6.5.2.

6.5.3.

6.6. An analysis of the alignment of South Africa’s Cybercrimes Bill to international legislation

6.6.1. Background to the documents

6.6.2.

6.6.3.

6.7. An analysis of the influence of classical military philosophy on seminal information warfare texts

6.8. Reflections on qualitative document analysis for information warfare and cybersecurity

6.9.

6.10.

Chapter 7. Anti-feminist Cyber-violence as a Risk Factor: Analysis of Cybersecurity Issues for Feminist Activists in France ........

Elena WALDISPUEHL

7.1.

7.2.

7.2.1.

7.2.2.

7.3.

7.4.

7.5.

7.6.

Why a methodology book?

Before the concept of cybersecurity was introduced, in the 1960s, computer security was referred to as the “protection of computer programs and data against unauthorized access” [PAY 83]. In the 1990s, the concept of “cybersecurity” emerged. This mainly refers to computer protection in its technical dimension, and some even see it as one of the major challenges for security policies for the coming decades: “One of the biggest challenges for strategic leaders in the 21st Century will be cyber security – protecting computers and the links between them” [JOH 95]. In much of the literature, “cyber” or “computer” technologies are first and foremost imperfect objects, which must be repaired to produce security. However, cybersecurity has a broader remit than computers: the security of cyberspace.

For the past 10 years or so, the human and social sciences (HSS) have been concerned with cybersecurity. Political [DEI 10, QUI 12, CAV 19], legal [GRA 04], strategic and economic readings have been proposed. Journals dedicated to the study of cybersecurity provide human and social science disciplines with spaces for discussing research from multiple viewpoints. These include the Journal of Cybersecurity (Oxford University Press)1, the Journal of Cybersecurity Research (JCR)2, the International Journal of Cybersecurity Intelligence and Cybercrime (IJCIC)3, the National Journal of

Introduction written by Daniel VENTRE, Hugo LOISEAU and Hartmut ADEN.

1 https://academic.oup.com/cybersecurity/pages/About.

2 https://clutejournals.com/index.php/JCR.

3 https://vc.bridgew.edu/ijcic.

Cyber Security Law4 and the Journal of Intelligence and Cyber Security5, to name a few. Most of these academic journals have only recently been founded. Cybersecurity, in any case, is in the process of becoming a fully fledged subject of research in the human and social sciences, if it has not already become this. Notwithstanding this observation, research still appears to be relatively scattered and heterogeneous, with each discipline within HSS grasping the issues and posing research questions based on its own approaches, using its own theoretical and methodological apparatus.

Our contribution to this wave of international cybersecurity productions will be a reflection on methodological aspects in the human and social sciences for cybersecurity research. This book therefore poses the following central question: what methods and theoretical tools can mobilize HSS researchers to address cybersecurity? This methodological dimension seemed essential to us for several reasons:

– Publications produced in recent years generally pay little attention to the methodological dimension. Research books and articles naturally address this methodological dimension in the formal framework of their development. However, they generally focus on the treatment of the subject matter of the particular publication. To date, there has been little effort to offer reflections centered on questions of methods and theories specific to the human and social sciences.

– The topic of cybersecurity can be confusing at first glance for young (and sometimes not so young) researchers. The purpose of cybersecurity seems to require mobilization and mastery of multiple fields of knowledge (that of the field specific to the HSS researcher, combined with knowledge of informatics, networks, communication, etc.). It is therefore a question of gathering knowledge that is essential to the researcher, thus a question of methodology.

– Once it has been defined, explained and deconstructed, cybersecurity will quickly appear as a complex object, with multiple components that will each be objects of research (cybercrime, cyberattacks, cyber threats, cyber risk, intelligence issues in cyberspace, etc.). Each of these objects may require specific knowledge, distinct theoretical frameworks and adapted

4 http://stmjournals.com/Journal-of-Cybersecurity-Law.html.

5 https://www.academicapress.com/journals.

methodologies. The chapters in this book eloquently demonstrate the complexity of the cybersecurity object.

– Moreover, another very important question arises when considering cybersecurity as being composite and complex: what can or should be the place of multidisciplinarity or interdisciplinarity in its study? As a discipline, cybersecurity is under two forms of pressure which are fertile for its development. The first is, of course, the willingness of researchers who see themselves as part of this discipline (in terms of knowledge, methods or techniques) to specialize in order to distinguish the cybersecurity object from the multitude of objects or dimensions that comprise it in the real world, as well as the ability to distinguish this field of research from other contiguous fields such as computer security, data protection and computer engineering. The second pressure is pushing the discipline to broaden its horizons towards HSS, since it is now accepted that cybersecurity is also a social phenomenon. This pressure thus pushes research towards interdisciplinarity or multidisciplinarity to take account of the human and social dimensions of cybersecurity.

– Is cybersecurity relevant to all HSS disciplines? This question implies that the human and social aspects of cybersecurity are potentially intersectional when the HSS address cybersecurity. In other words, theories, methods and analytical frameworks as much as variables from psychology, anthropology, sociology or any other HSS discipline, can contribute in some way to explaining or understanding the phenomenon of cybersecurity. Mobilizing these different research tools and methodological heritages seems beneficial for an integrated analysis of cybersecurity and an unsuspected wealth of knowledge.

– What benefits does cybersecurity derive from its encounter with the human and social sciences? The answer to this question is based on what characterizes the humanities and social sciences and what ultimately distinguishes them from other sciences. The main distinction lies in their ability to analyze complex human phenomena both qualitatively and quantitatively. As a result, a multitude of tools and methodological approaches exist and make it possible, in particular, to refine cybersecurity knowledge and to strongly qualify techno-determinism (or “solutionism” as Morozov calls it [MOR 14]). This dual qualitative and quantitative capacity enables the HSS to identify issues in cybersecurity in three ways. First of all, in a macro way where the globality of the cybersecurity phenomenon is revealed in its structural, systemic and environmental aspects. For example,

international geopolitics is being transformed by the importance of cybersecurity in international relations today [DOU 14]. Secondly, in a meso way, where decision-making processes, the roles of the different institutional actors and private organizations are highlighted. We need only think of the formulation of a foreign or defense policy that cannot disregard hybrid threats in terms of cybersecurity. Finally, in a micro way, where the uniqueness and particularity of this same cybersecurity phenomenon are observable in individual behavior or thought, such as the victim of a phishing campaign, for example.

The contribution of HSS is also evident in its capacity to generate social debate on cybersecurity issues and to force the discipline to popularize its basic concepts. The transmission of knowledge and social awareness about cybersecurity issues is thus facilitated. Finally, it provides a context for cybersecurity-related problems or risks by giving historical depth to otherwise impossible to find reflection or debate.

– A final question is, in our opinion, methodologically and theoretically necessary: is it necessary to mobilize pre-existing theoretical frameworks, or is it possible to envisage their renewal? The nature of the cybersecurity object certainly favors multidisciplinarity, but nevertheless creates two obstacles blocking its analysis. On the one hand, cybersecurity combines a technical dimension with a human dimension, which makes this a hybrid and complex research object, as mentioned above. Moreover, few theoretical or methodological frameworks currently exist to address the full human and technical dimensions of cybersecurity so as to gain a holistic or integrated perspective on cybersecurity. On the other hand, the speed of IT development (technical dimension) and the adoption of new technologies (human dimension) make existing analytical frameworks quickly obsolete. These two obstacles must be taken into account in mobilizing existing theoretical frameworks, as well as, and more importantly, in developing new comprehensive analytical frameworks. In order to achieve this, a study on research methods and theoretical tools of the human and social sciences in the study of cybersecurity seemed necessary to us.

Contributions to the book

The seven chapters of this book offer different perspectives on particular aspects of cybersecurity and provide some answers to the various questions outlined above.

In his chapter, Hugo Loiseau discusses the scientificity of cybersecurity studies. This still needs to be defined and demonstrated in the human and social sciences. Among the abundance of research in cybersecurity, in all sciences combined, only a few studies are devoted to the methodological and scientific problems of this emerging discipline. Indeed, in the human and social sciences, from an epistemological point of view, studies on cybersecurity require methodological criticism to improve their scientificity and credibility in relation to computer sciences and engineering. In this chapter, research methods, access to data and the development of a cybersecurity discipline in the humanities and social sciences are thus assessed. The objective of this chapter is to lay the epistemological foundations for proposing an operationalizable definition of “cybersecurity” for the human and social sciences.

Daniel Ventre deals specifically with definitions of concepts and ways of expressing and grasping them. Definition, typology, taxonomy and ontology (grouped under the acronym DTTO) can be used to express cybersecurity, to represent it, understand it and draw its domain and its perimeter. The literature most often postulates that there is no consensus on DTTO. In this chapter, the author attempts to identify sufficiently strong and significant trends in each of the approaches to cybersecurity in order to study this premise.

Hartmut Aden analyzes tensions and synergies between cybersecurity and data protection from the perspective of legal science and public policy analysis, with a focus on the transdisciplinary links between the two. This shows that the combination of legal methods of interpreting norms emerging in the field of cybersecurity and qualitative and quantitative social science methods used for public policy analysis can contribute to a better understanding of the various facets of the tensions and synergies between cybersecurity and data protection.

Joseph Fitsanakis is interested in the methods, tools and theories that the researcher can mobilize and the specific obstacles that may be encountered in studying the challenges of State-sponsored cyber-espionage. He provides a survey of current research on the subject in the human and social sciences, focusing on the strategic, tactical and operational dimensions of the phenomenon. He identifies and discusses the relevant theoretical and conceptual tools to conduct this research.

The “Science” of Cybersecurity in the Human and Social Sciences: Issues

and Reflections

The scientificity of cybersecurity studies is yet to be demonstrated in the humanities and social sciences. Among the plethora of cybersecurity research, few studies are devoted to the methodological and scientific problems of this emerging knowledge. Indeed, from an epistemological point of view, cybersecurity studies require a methodological critique to improve their scientificity and credibility in relation to computer science and engineering. In this chapter, research methods, access to data and the contributions of the human and social sciences to cybersecurity studies are assessed. The objective of this chapter is to lay the epistemological foundations for an operationalizable definition of cybersecurity for the human and social sciences.

1.1. Introduction

How can human and social sciences (HSS) studies in cybersecurity claim to be scientific? Several answers to this question come to mind, and based on these, it is necessary to clarify the debate through an epistemological approach to the contribution of HSS to cybersecurity studies, particularly in terms of methodology, all within the framework of the empirical–analytical paradigm and post-positivism, both of which are currently dominant in science.

Indeed, according to the principles of the scientific method advocated by these paradigms, it is the method used that distinguishes science from nonscience [NØR 08]. In order to make this distinction, the use of epistemology

Chapter written by Hugo LOISEAU

is unavoidable. The critical study of science enlightens us about the value and significance of science and its results. So, what is the scientific value of human and social sciences studies in cybersecurity?

It could be argued that the HSS perspective on cybersecurity is peripheral, if not unimportant, to the issues raised by this field. Risks and threats from cyberspace directly affect national security and public safety through the deep penetration of computer networks into societies and their reliance thereon. The first reflex of societies is therefore to militarize and securitize 1 these issues, and this is what the vast majority of states throughout the world has done.

It could also be argued that HSS research results are very abstract and ideal compared to the results of computer science and engineering that propose concrete software or hardware “solutions” to cybersecurity issues. The contribution of HSS to cybersecurity would therefore be marginal since it would not be immediately applicable to urgent technical or technological problems. What HSS produces in cybersecurity would mobilize too many resources (social awareness, political will, legislative changes, mental representations, etc.) to be qualified as useful. Overall, the contribution of HSS to cybersecurity studies would contribute little to knowledge and its real-world application. In other words, the explanatory and practical scope of the research produced in cybersecurity by HSS would be weak.

Moreover, in the cyber field in general, while Saleh and Hachour praise the merits of a multidisciplinary opening towards cyber-issues in HSS [SAL 12], Bourdeloie invites the community of HSS researchers to a vast epistemological effort for the positioning and constructive criticism of cyberissues [BOU 14]. There is therefore a need for epistemological reflection on the place of HSS in cybersecurity studies. Once this need is recognized, contemporary epistemology teaches us that the social and human sciences alternate between two references for scientificity, an external one in the natural sciences and an internal one for HSS [BER 12]. Cybersecurity studies are an exemplary example of the tension between these two references, which is revealed in the methodological preferences of researchers. For some, the causality of cyber phenomena can be demonstrated and explained, which is an

1 Securitization corresponds to the idea of dealing, in political discourse, with an issue predominantly from the security angle, to the detriment of other angles (social, health, etc.). The “war on drugs” is a perfect example.

external reference for scientificity where the possibility of issuing general laws is attainable (positivist approach). Whereas for others, social actors and their behavior are more relevant scientifically, which is an internal reference for scientificity within the HSS, and they must be understood in all their subjectivities (constructivist approach and the related heterogeneity). The debate is not closed and can be seen in cybersecurity studies.

This rapid diagnosis may seem to show a lack of scientificity in HSS studies on cybersecurity, as epistemological issues are poorly addressed in the face of the immediate need for results on issues. A large part of the problem stems from the inability of HSS in cybersecurity studies to reach a level of internal scientificity sufficient to be considered scientific by the computer and engineering sciences, and therefore, by implication, socially credible to the research community that has developed a body of knowledge based on the reference of scientificity used by the natural sciences.

In short, there is a lack of reflection on the epistemology of the HSS in relation to cybersecurity. Yet many research studies and research methods exist and are published under the name of science without any real epistemological contribution. Yet again, there is an astonishing similarity between cybersecurity and the phenomena analyzed by HSS. The nature of cybersecurity and cyber objects, like the vast majority of the objects of HSS, is characterized by hybridity, multi-causality, ephemerality, interpretative ambiguity, etc. Taking these common characteristics into account, we can therefore ask whether it is possible and even desirable to move from cybersecurity studies (essentially descriptive and empirical studies) to a science of cybersecurity (nomothetic and more theoretical studies) in which the HSS would be fully considered as contributors of research results meeting the principles of the scientific method? If this is not the case, then what is lacking in HSS to achieve a sufficient level of consideration both scientifically and socially?

This chapter will address this issue in three parts. The first will address the central question of the methodology used in the HSS to analyze the cybersecurity object. The second part will cover the thorny issue of the data available to the HSS for analyzing cybersecurity. The third part will present a proposed definition of cybersecurity that can be operationalized for and by the HSS in order to clarify the nature of the subject matter dealt with by the HSS. The real purpose of this chapter, beyond epistemological debates, is to reflect on the ideal framework within which cybersecurity studies in the HSS could reach the highest levels of scientificity, according to the rules of the art.

1.2. A method?

The humanities and social sciences are characterized by the diversity of methodological approaches they use for their analyses. The diversity of these methods corresponds to a necessity: that of the diversity and fragmentation of their object of research. For the social sciences, this object comes down to the social relationships that humans have with each other. For the social sciences together with humanities, the scope of their analyses is even broader and represents everything that has to do with human beings. These sciences are also characterized by their disciplinary porosity within their own sciences, where interdisciplinarity (or multidisciplinarity) is the key to the validation of knowledge. The political phenomenon can be explained through the many sub-disciplines of political science, to take just one example. The same is true for all disciplines in the social sciences. The humanities are subject to the same interdisciplinarity. This porosity is also increasingly apparent at the fringes of the HSS. The human causes or consequences of biological, physical and technological phenomena are becoming central in the natural, computer and life sciences. We need to only think of studies on global warming and its anthropogenic causes or of public health to be convinced of this. In short, in the HSS, there is not a precise core of well-circumscribed phenomena that would mobilize a community of researchers towards a growing accumulation of valid knowledge.

HSS have arrived at this diversity through epistemological reflections that have, throughout the 20th and 21st Centuries, highlighted the ontological differences of HSS in relation to other sciences. This has resulted in the development of a whole series of ethical, theoretical, methodological and etiological reflections on the objects of HSS. These are thus nonreproducible in time (we speak of the uniqueness of the object), which prevents the strict application of the experimental method. They are also very limited in terms of predictability, and, to overcome this limitation, HSS research turns to comparative analysis and ex post research. They also correctly develop new criteria of scientificity that form a common epistemic space, according to Berthelot, and define them as a science in their own right [BER 12]. In other words, in HSS, a diversity of theories, methods and paradigms coexist within the same field of knowledge (human and social), to the benefit of the validity of the knowledge produced by disciplines, research programs and communities of researchers.

Without entering too much into this epistemological debate, and beyond the discussion on the very notion of criteria, the issues in HSS concerning the criteria of scientific validity can be summarized in the relevance of transposing criteria from the natural sciences to the social sciences (external reference) and especially how to adjust them to make them consistent with the specific nature of HSS (internal reference) [KEM 12]. For Proulx, generativity, i.e. the

“…capacity for qualitative research to stimulate and participate in the production of new objects, new perspectives, new methods of gathering, etc…” [PRO 19 pp. 63–64]

allows the debate to be decided. The generativity of research does not imply evaluating the value of research only on the basis of fixed, pre-existing and independent criteria. Instead, generativity proposes assessing the value of research based on its fertility, in terms of new ideas, new methods or new data or results generated [PRO 15 pp. 25–27]. In our view, cybersecurity studies, especially for the HSS, would deserve to be evaluated according to this generativity criterion, since it is from the diversity of methods, theories and knowledge relevant to cybersecurity that we can draw conclusions.

This methodological diversity and these epistemological reflections are therefore a source of intelligibility and credibility for the HSS, as they demonstrate the added value of these sciences in traditional cybersecurity studies and their claim to scientificity. As Corbière and Larivière put it:

“In a world of research that is becoming increasingly open and broad, it is becoming desirable to have an inclusive perspective, capable of integrating the contributions of various methodological approaches, while recognizing their own particularities.” [COR 14 p. 1]

In our view, this is exactly the case for cybersecurity studies, which benefit from combining their research efforts in a multidisciplinary manner using a variety of research methods.

In order to grasp the diversity of cyber phenomena, the HSS have developed an analytical corpus, concepts and representations that make it possible to theorize cyber-attacks, cyber operations, cybercrime, etc. Efforts

to establish a typology were made very early on by cybersecurity studies in order to name phenomena taking place in cyberspace and their consequences in reality [VEN 11]. In this sense, idiographic research or description of the observed phenomena, the first step in any emerging science, has been successfully undertaken. Logically, for the HSS, this emergence must first be descriptive, i.e. identify the cybersecurity object and its social and human specificity. This stage is already well underway and is producing interesting results that feed into scientific and political debates.

The methodological threshold that remains to be crossed for HSS cybersecurity studies, in our opinion, lies in the development and relevant use of nomothetic methods, such as the comprehensive and explanatory approach, in order to achieve the theorizing claim of the empirical–analytical paradigm. The use of these two research approaches thus reduces the tension between the two sources of scientificity discussed above. The first approach seeks to understand the cyber behavior of individual and collective social actors, while the second attempts to identify relevant and valid variables to form theories to be subjected to empirical verification. The scientific process then follows a sequence of trial and error to improve research protocols and knowledge. However, this requires valid data, the creation of a discipline and the development of a common definitional basis, as discussed below. The ultimate goal of this phase is to answer with confidence the fundamental epistemological question: “Do we know whether we know adequately what we claim to know?” [NØR 08]. In other words, this question allows a critical look at the scientific value of the methods used in HSS to analyze cybersecurity.

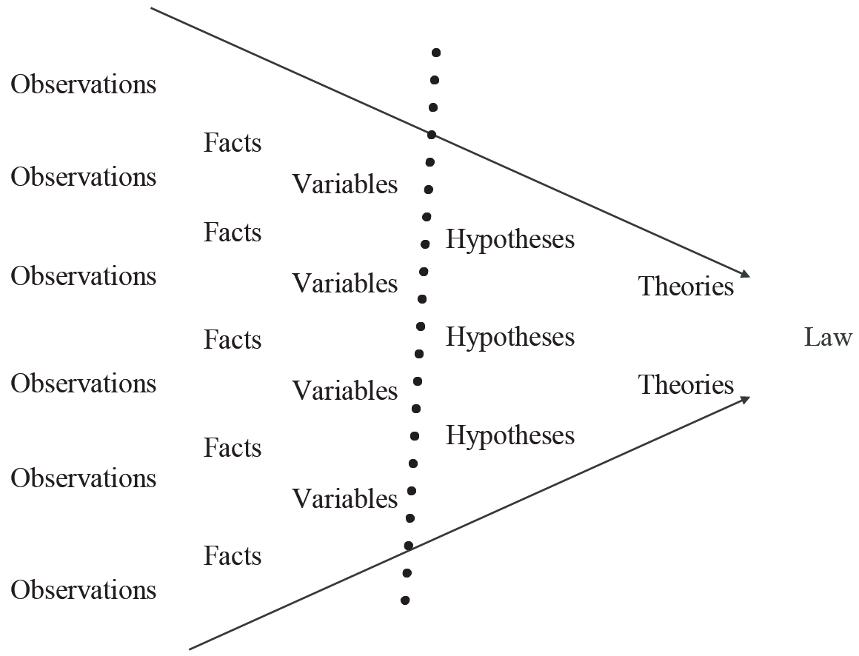

Figure 1.1 sets out the scientific process that filters observations, transforms them, in fact, operationalizes them into variables and links them into hypotheses that can form the basis of theories, which sometimes produce scientific laws. Cybersecurity studies are, in our opinion, where the dotted line is located, i.e. in the passage from variables to hypotheses. Of course, the teleological nature of such a graph must be qualified, as it is only used here to illustrate what is being said, knowing full well that this process is marked by major jolts and setbacks. Finally, this graph illustrates the magnitude of labor ahead for the HSS, in terms of explanatory work to reach a level of external scientificity equivalent to that of the natural and computer sciences.

1.1. From observations to scientific laws

From an epistemological point of view, the following stage of this emergence manifests itself through the development of proven HSS research methods in cybersecurity. The advantage is that cybersecurity studies can draw on the vast methodological heritage of the HSS to adapt it to its purposes. This stage involves a more subjectivist and sociological look, through the empirico-inductive (comprehensive) approach, to understand the motivations and behaviors of cybersecurity actors. The major contribution of the HSS to cybersecurity studies is found in this type of method. Indeed, they allow the development of concepts and variables with very strong internal validity, because they are anchored in social reality. This heuristic phase of observations and reflections precedes a confirmation phase to verify the validity of the hypotheses put forward [DEK 09].

In this subsequent step 2 , the concepts and variables studied are linked together in cause-and-effect relationships, in order to discover the explanatory factors and consequences of cybersecurity. Hypotheticodeductive methods put the different hypotheses in competition with reality

2 In this chapter, for lack of space, we will not deal with the abduction phase, which is between the heuristic phase and the confirmatory phase.

Figure

and are validated, or not, by this test of facts. These hypothetico-deductive methods also allow, where ethically possible, the deployment of experimental or quasi-experimental research in the HSS.

One problem remains, however, in applying this range of research methods. Indeed, how can we distinguish the individual from the community and vice versa? In other words, how can the agency-structure debate be resolved 3 with these different methods? The simplest answer is to use qualitative analyses (for individuals or small groups of individuals) and quantitative analyses (for communities). Indeed, the phenomena arising from the vast field of observation of cybersecurity lend themselves advantageously to quantitative analyses (the number of cyber-attacks over a given period of time, the extent of the cyber threat, the amount of personal data leaked, the number of actors involved, etc.) as well as to qualitative analyses (the nature of the codes developed, whether militarized or not, the nature of the targets, the nature of the personal data compromised, the nature of the actors involved, etc.). As long as cybersecurity studies benefit from a substantial body of valid data and information, it is possible to choose the right methods, i.e. those adapted to the nature of the object, the state of the literature and the resources available to the researcher.

This diversity of methods can be envisaged along two fundamental lines, making it easier to construct a typology of the methods commonly used in HSS. The first axis corresponds to qualitative and quantitative analyses. These identify what is quantifiable and present in large numbers. Qualitative analyses, on the other hand, apprehend what is related to words, the nature of the phenomena observed and their context. The contribution of the HSS, particularly with regard to qualitative analyses, is very important, in order to grasp the role of individuals, their interpretation of the meaning they give to their actions, as well as the role of institutions and the results of their actions. For example, in the HSS, a quantitative analysis could estimate the costs of a cyber-incident to industry or government [ROM 16]. A qualitative study, on the other hand, would seek to describe the objectives, the processes for formulating proposals, the roles assigned to each of the actors involved and the results of the negotiations for the governance of cyberspace within the United Nations Group of Governmental Experts on Information Security [HEN 19].

3 In other words, what is the predominant variable in explaining or understanding a social phenomenon? Is it the social actor, the social structure that surrounds it or the fusion of the two that is predominant?

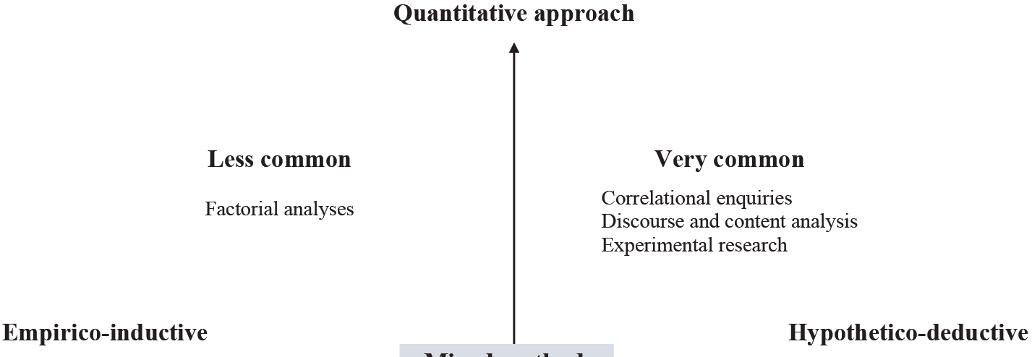

The second axis distinguishes between hypothetico-deductive approaches (explanatory approach) and empirico-inductive approaches (comprehensive approach) and reflects the tension between explaining and understanding arising from the internal and external references of scientificity in HSS. These two axes cover the majority of research strategies that can be implemented in the HSS. They cover both individual and community interpretive efforts, as well as attempts to discover the causes of phenomena. Naturally, qualitative analyses are more common in empirico-inductive research, as they are deployed with individuals or small groups with the aim of interpreting behaviors. Therefore, in the lower left quadrant of Figure 1.2, there are many research strategies that can be used to achieve this goal.

Figure 1.2. Quantitative and qualitative approaches and empirico-inductive and hypothetico-deductive approaches in the human and social sciences

In the opposite quadrant (top right) are the quantitative and hypotheticodeductive methods used to identify trends and causalities between two cybersecurity phenomena or between other phenomena and cybersecurity. In the HSS, these methods mainly use correlational research strategies, discourse or content analysis and experimental or quasi-experimental research.

Of course, thanks to theoretical and methodological triangulation, taken in a broad sense, several crossovers, overlaps and convergences between quadrants or methods are allowed. This corresponds to mixed methods, located in the center of the graph, which take advantage of the crossover of qualitative and quantitative methods, analyses and data [PAQ 10].

This graph therefore provides a global picture of the possibilities of research methods available to the HSS in the study of cybersecurity. This design offers the advantage of being able to analyze cybersecurity at micro, meso (with mixed methods) and macro levels, according to the objectives of explaining or understanding phenomena. It also facilitates the triangulation of theories and research methods, as it marks out the universe of methodological possibilities with regard to these objects.

However, a major problem remains in the use of this collection of research methods. The first relates to the notion of Ceteris paribus sic stantibus, or in English, “all things otherwise equal”. In other words, cybersecurity studies must accept the existence of a gap between the analysis of reality at time X and reality at time X+1, since X is totally different from X+1, as cyberspace changes very rapidly [KAR 12]. Indeed, the context, the environment, i.e. cyberspace, is constantly changing, through the introduction of new technologies, new protocols, the arrival of new players or the transformation of existing players, or through the nature of the information that circulates, or through the transformation and ultra-rapid dissemination of information observed qualitatively by researchers. This has the consequence of very quickly invalidating any knowledge developed through a scientific process and makes research very difficult to reproduce. Cyberspace is therefore a very special field of research that needs to be explored.

The issue at stake is that every effect has a cause4, and cybersecurity and its study cannot escape this truth. This constraint therefore diminishes the possibility of achieving a complete and valid knowledge of cyberspace and cybersecurity for both natural sciences and the HSS. In the face of this impasse, qualitative and comprehensive research finds all its relevance.

Methodologically speaking, in summary, cybersecurity studies can and should navigate the four quadrants of the table and continue efforts to describe cybersecurity-related phenomena. Ideally, these studies would

4 According to the principle ex nihilo nihil fit (nothing comes of nothing).

apply and refine all of these methods to achieve a high level of general knowledge, within the limits of what is possible, with the aim of providing scientifically informed recommendations and thus promote the well-being of humankind, which is the ultimate goal of all science. One challenge remains, however, that of the validity of the data.

1.3. Data?

The implementation of research methods in all sciences requires access to information and data relevant to those sciences. This is the empirical basis on which the theoretical constructions that generally result from application of the various research methods are built. According to Gauthier and Bourgeois, in scientific research, researchers must apprehend reality according to “an integral conception of the facts, on the refusal of the prior absolute and on the awareness of [their] own limits. [...] It is an objective quest for knowledge on factual issues” [GAU 16 p. 8].

In this respect, cybersecurity studies, and not only cybersecurity in the HSS, face two problems. The first is intrinsic to the nature of the object itself, i.e. the hidden aspect of the actors, their intentions and actions in cyberspace and, more specifically, in relation to threats to cybersecurity.

The second issue is the privacy of data for cybersecurity studies. These data are of a private nature (personal data, strategic company information, national security data, etc.). They come from individuals, from the private and public sectors, and the vast majority of them are subject to the seal of confidentiality. Finally, very often, these data are analyzed by private cybersecurity companies in a contractual framework where the disclosure of information, which is very often sensitive, is greatly restricted. The quest for profit, not knowledge, is the main driver of this market, which encourages the appearance of conflicts of interest. Taken together, these problems delay or impede improvements in cybersecurity, cyber resilience or post-incident de-escalation because the victim of the cyber-attack or cyber operation cannot know exactly what really happened, in the way that researchers do.

However, there is a latent imprecision in the data (and consequently in the research results), even with large public surveys produced in a professional manner. For example, Statistics Canada recently conducted a

survey entitled: “Canadian Cyber Security and Cyber Crime Survey” [STA 18] covering the year 2017.

“The purpose of the Canadian Cyber Security and Crime Survey is to collect data on the impact of cybercrime on Canadian businesses, including such aspects as investment in cyber security measures, cyber security training, the number of cyber security incidents and the costs associated with responding to these incidents.” [STA 18]

To this end, Statistics Canada created and submitted a 35-question questionnaire to the information technology managers or senior managers responsible for computer and network security in the companies surveyed. The sample size was 12,597 Canadian companies, and the response rate was 86%.

Among the 35 questions, several dealt with cybersecurity threats and digital risks related to cybercrime to Canadian businesses of all sizes.

For example, question 22 asked:

“In your opinion, what was the method used to compromise cybersecurity? Select all that apply.

Incident(s) to disrupt or disfigure the business or its web presence

Incident(s) to steal personal or financial information

Incident(s) to steal money or to demand payment of a ransom

Incident(s) to steal or improperly use intellectual property or business data

Incident(s) to access unauthorized or privileged access areas

Incident(s) to monitor and track business activities

Incident(s) without known motive.” [STA 18]

The results generated by this question are misleading. First, asking this question assumes that the respondent is aware of the intentionality of the