CurrentDevelopments inBiotechnology andBioengineering

FilamentousFungiBiorefinery

Editedby

MohammadJ.Taherzadeh

SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s,Sweden

JorgeA.Ferreira

SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s,Sweden

AshokPandey

CentreforInnovationandTranslationalResearch,CSIR-IndianInstitute ofToxicologyResearch,Lucknow,India SustainabilityCluster,SchoolofEngineering,UniversityofPetroleumand EnergyStudies,Dehradun,India

Elsevier

Radarweg29,POBox211,1000AEAmsterdam,Netherlands

TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates

Copyright©2023ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearance CenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher (otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroadenour understanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusing anyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationormethods theyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhavea professionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeanyliability foranyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceorotherwise,or fromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

ISBN:978-0-323-91872-5

ForinformationonallElsevierpublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: SusanDennis

EditorialProjectManager: HelenaBeauchamp

ProductionProjectManager: KiruthikaGovindaraju

CoverDesigner: MatthewLimbert

TypesetbySTRAIVE,India

Contributors

RuchiAgrawal TheEnergyandResourcesInstitute,TERIGram,GwalPahari,Haryana, India

HamidAmiri DepartmentofBiotechnology,FacultyofBiologicalScienceand Technology;EnvironmentalResearchInstitute,UniversityofIsfahan,Isfahan,Iran

K.Amulya BioengineeringandEnvironmentalSciences,DepartmentofEnergyand EnvironmentalEngineering,CSIR-IndianInstituteofChemicalTechnology,Hyderabad, India

ElisabetAranda InstituteofWaterResearch;DepartmentofMicrobiology,Universityof Granada,Granada,Spain

MohammadtaghiAsadollahzadeh SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,Universityof Bora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s,Sweden

AparnaBanerjee Centrodeinvestigacio ´ nenEstudiosAvanzadosdelMaule(CIEAM), Vicerrectorı´adeInvestigacio ´ nYPosgrado,UniversidadCato ´ licadelMaule,Talca, Chile

ParameswaranBinod MicrobialProcessesandTechnologyDivision,CSIR-National InstituteforInterdisciplinaryScienceandTechnology(CSIR-NIIST), Thiruvananthapuram,Kerala,India

KamalpreetKaurBrar DepartmentofCivilEngineering,LassondeSchoolofEngineering, YorkUniversity,Toronto,ON;IndustrialWasteTechnologyCenter,AbitibiTemiscamingue, QC,Canada

G € ulruBulkan SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s, Sweden

GustavoCabrera-Barjas UniversidaddeConcepcio ´ n,UnidaddeDesarrolloTecnolo ´ gico (UDT),Coronel,Chile

MartaCebria ´ n AZTI,FoodResearch,BasqueResearchandTechnologyAlliance(BRTA), ParqueTecnolo ´ gicodeBizkaia,Derio,Bizkaia,Spain

Chiu-WenChen DepartmentofMarineEnvironmentalEngineering,NationalKaohsiung UniversityofScienceandTechnology,KaohsiungCity,Taiwan

EduardoCoelho CEB—CentreofBiologicalEngineering,UniversityofMinho,Braga, Portugal

GabrielaA ´ ngelesdePaz InstituteofWaterResearch,UniversityofGranada,Granada, Spain

CedricDelattre UniversiteClermontAuvergne,ClermontAuvergneINP,CNRS,Institut Pascal,Clermont-Ferrand;InstitutUniversitairedeFrance(IUF),Paris,France

RatihDewanti-Hariyadi DepartmentofFoodScienceandTechnology,IPBUniversity, Bogor,Indonesia

Lucı´liaDomingues CEB—CentreofBiologicalEngineering,UniversityofMinho,Braga, Portugal

Cheng-DiDong DepartmentofMarineEnvironmentalEngineering,NationalKaohsiung UniversityofScienceandTechnology,KaohsiungCity,Taiwan

PascalDubessay UniversiteClermontAuvergne,ClermontAuvergneINP,CNRS,Institut Pascal,Clermont-Ferrand,France

LaurentDufosse ChemistryandBiotechnologyofNaturalProducts(CHEMBIOPRO), UniversityofReunionIsland,ESIROIFoodScience,Saint-DenisCedex9,Reunion Island,France

JorgeA.Ferreira SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s, Sweden

ShakuntalaGhorai DepartmentofMicrobiology,RaidighiCollege,Raidighi,India

DanielG.Gomes CEB—CentreofBiologicalEngineering,UniversityofMinho,Braga, Portugal

ShararehHarirchi SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s, Sweden;DepartmentofCellandMolecularBiology&Microbiology,Facultyof BiologicalScienceandTechnology,UniversityofIsfahan,Isfahan,Iran

JoneIbarruri AZTI,FoodResearch,BasqueResearchandTechnologyAlliance(BRTA), ParqueTecnolo ´ gicodeBizkaia,Derio,Bizkaia,Spain

SajjadKarimi SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s,Sweden

VinodKumar SchoolofWater,Energy,andEnvironment,CranfieldUniversity,Cranfield, UnitedKingdom

PatrikRolandLennartsson SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s, Bora ˚ s,Sweden

HanifahNuryaniLioe DepartmentofFoodScienceandTechnology,IPBUniversity, Bogor,Indonesia

SaraMagdouli DepartmentofCivilEngineering,LassondeSchoolofEngineering,York University,Toronto,ON;IndustrialWasteTechnologyCenter,AbitibiTemiscamingue, QC,Canada

Manikharda DepartmentofFoodandAgriculturalProductTechnology,Universitas GadjahMada,Yogyakarta,Indonesia

PhilippeMichaud UniversiteClermontAuvergne,ClermontAuvergneINP,CNRS,Institut Pascal,Clermont-Ferrand,France

MarziehMohammadi SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s, Sweden

RafaelLeo ´ nMorcillo InstituteofWaterResearch,UniversityofGranada,Granada, Spain

SoumyaMukherjee UniversityofToledo,Toledo,OH,UnitedStates

VivekNarisetty SchoolofWater,Energy,andEnvironment,CranfieldUniversity, Cranfield,UnitedKingdom

SeyyedVahidNiknezhad BurnandWoundHealingResearchCenter;Pharmaceutical SciencesResearchCenter,ShirazUniversityofMedicalSciences,Shiraz,Iran

AshokPandey CentreforInnovationandTranslationalResearch,CSIR-IndianInstitute ofToxicologyResearch,Lucknow;SustainabilityCluster,SchoolofEngineering, UniversityofPetroleumandEnergyStudies,Dehradun,India

MohsenParchami SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s, Sweden

AnilKumarPatel DepartmentofMarineEnvironmentalEngineering;InstituteofAquatic ScienceandTechnology,NationalKaohsiungUniversityofScienceandTechnology, KaohsiungCity,Taiwan

GuillaumePierre UniversiteClermontAuvergne,ClermontAuvergneINP,CNRS,Institut Pascal,Clermont-Ferrand,France

EndangSutriswatiRahayu DepartmentofFoodandAgriculturalProductTechnology, UniversitasGadjahMada,Yogyakarta,Indonesia

G.Renuka DepartmentofMicrobiology,PingleGovernmentDegreeCollegeforWomen, Warangal,India

SaddysRodriguez-Llamazares CentrodeInvestigacio ´ ndePolı´merosAvanzados(CIPA), EdificioLaboratorioCIPA,Concepcio ´ n,Chile

NedaRousta SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s, Sweden

TanerSar SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s,Sweden

BehzadSatari DepartmentofFoodTechnology,CollegeofAburaihan,Universityof Tehran,Tehran,Iran

UlisesConejoSaucedo InstituteofWaterResearch,UniversityofGranada,Granada, Spain

ZohresadatShahryari SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s, Sweden;AvidzymeCompany,Shiraz,Iran

PoojaSharma EnvironmentalResearchInstitute,NationalUniversityofSingapore; EnergyandEnvironmentalSustainabilityforMegacities(E2S2)PhaseII,Campusfor ResearchExcellenceandTechnologicalEnterprise(CREATE),Singapore,Singapore

RuiSilva CEB—CentreofBiologicalEngineering,UniversityofMinho,Braga,Portugal

RaveendranSindhu MicrobialProcessesandTechnologyDivision,CSIR-National InstituteforInterdisciplinaryScienceandTechnology(CSIR-NIIST), Thiruvananthapuram,Kerala,India

ReetaRaniSinghania DepartmentofMarineEnvironmentalEngineering,National KaohsiungUniversityofScienceandTechnology,KaohsiungCity,Taiwan

MohammadJ.Taherzadeh SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s, Bora ˚ s,Sweden

JoseA.Teixeira CEB—CentreofBiologicalEngineering,UniversityofMinho,Braga, Portugal

SunitaVarjani GujaratPollutionControlBoard,Gandhinagar,Gujarat,India

S.VenkataMohan BioengineeringandEnvironmentalSciences,DepartmentofEnergy andEnvironmentalEngineering,CSIR-IndianInstituteofChemicalTechnology, Hyderabad,India

RachmaWikandari DepartmentofFoodandAgriculturalProductTechnology, UniversitasGadjahMada,Yogyakarta,Indonesia

AkramZamani SwedishCentreforResourceRecovery,UniversityofBora ˚ s,Bora ˚ s,Sweden

Preface

AdvancesinFilamentousFungiBiorefinery isabookintheElsevierserieson Current DevelopmentsinBiotechnologyandBioengineering (Editor-in-Chief:AshokPandey).This bookexploresvariousfundamentalandindustrialaspectsoffilamentousfungiforthe manufactureofdifferentproductsusedinoursociety.

Fungiarepartoftheecosystem,andtheworldwouldlooktotallydifferentwithout them.Mostpeopleknowonlymushroomsandtheirfruitingbodiesasfungi.However, themainfungalbiomassistheirfilaments,whichcanhavemanyapplications.Filamentousfungicangrowonalargevarietyofmaterialsthatcontaincarbohydrates,proteins, fats,etc.,bydegradingthemacromoleculesandthenassimilatingthemonomerstogrow andproducevariousenzymesandmetabolites.Thismeansthattherearealargenumber ofsubstratesonwhichtogrowfungi,fromagriculturalandforestresidualstoindustrial residualsandproducts,tohouseholdwastesandwastewaters.Dependingontheecosystemandtheenvironmentalorcultivationconditions,fungicangrowinvariousmorphologies,andmanyfungalstrainsaredimorphic,meaningthattheycangrowbothlikeyeast andfilaments.Inaddition,theycangrowinvariousenvironmentalconditions,suchas aerobicoranaerobic.Theyadapttheirenzymemachineryasrequiredtotheseconditions, producingavarietyofmetabolitesthatarenecessaryforthefungitogrow.

Asfungigrowonalargenumberofsubstrates,theycanproducevariousextracellular enzymessuchashydrolyticenzymestodegradebiopolymers.Therefore,fungiarean industrialsourceofenzymeproduction.

Ultimately,weshouldnotforgetthattheonlygoaloffungiistogrow.However,incertainconditionstheycanproduce,forexample,enzymesand/orvariousmetabolites, whichcanbeusedasproducts.Bearinginmindthesinglegoaloffungi,oneoftheirmajor productsisalwaysfungalbiomassormycelium.Thisbiomassnormallycontainsprotein, fat,andotherbiopolymerssuchaschitosanorbeta-glucaninitscellwall,andavarietyof bioactivecompounds.Asaresult,thebiomassofmanyfilamentousfungicanbeagood sourceforfoodandfeed.Someofthesefungi,particularlyamongthezygomycetesand ascomycetes,areedibleandcanbeusedfordifferentfoodpreparationssuchastempeh, oncom,andkoji.However,thereisalsoaninterestnowadaysindevelopingnewfoodand feedsuchasfishfeedfromfungiasanenvironmentallyfriendlyandhealthyalternativeto meat,chicken,orevensoy-basedvegetarianproducts,forexample.However,assome fungiproducemycotoxins,thefungalstrainandtheprocessconditionsshouldbechosen carefullyinordertoavoidanyriskstohumansoranimals.

Theaimofthisbookistoexplorecomprehensivelytheadvancesinusingfilamentous fungiasthecoreofindustrialbiorefinery.Thebookprovidesathoroughoverviewand

understandingoffungalbiology,biotechnology,andecosystems,andcoversavarietyof industrialproductsthatcanbedevelopedfromfungi.

Thecontentsofthisbookareorganizedin18chapterstocover:(a)thefungalecosystem,biology,andbiotechnology;(b)thefungalgrowthandprocessinsolidstateandsubmergedfermentation,particularaspectsofbioreactors,andsampling,preservation,and processmonitoring;(c)mycotoxinsasanimportantaspecttochoosethefungalstrainsfor processes;(d)productsofbiorefinerythatthefungiincludingfood,feed,organicacids, alcohols,bioactivepigmentedcompounds,andantibiotics;and(e)fungiinnovel processes.

Wearegratefultotheauthorsforcompilingthepertinentinformationintheirchapters,whichwebelievewillbeavaluableresourceforboththescientificcommunityand readersingeneral.Wearealsogratefultotheexpertreviewersfortheirusefulcommentsandscientificinsights,whichhelpedshapethebook’sorganizationandwhich improvedthescientificdiscussionsandoverallqualityofthechapters.TheEditors (MohammadJ.TaherzadehandJorgeA.Ferreira)acknowledgesupportfromthe SwedishAgencyforEconomicandRegionalGrowth(Tillvaxtverket)throughaEuropean RegionalDevelopmentFund“Ways2Tastes.”Finally,oursincerethanksgotothestaff atElsevier,includingDr.KostasMarinakis(formerSeniorBookAcquisitionEditor), Dr.KatieHammon(SeniorBookAcquisitionEditor),andBernadineA.Miralles(Editorial ProjectManager),andtheentireElsevierproductionteamfortheirsupportinpublishing thisbook. Editors

MohammadJ.Taherzadeh

Worldoffungiandfungal ecosystems

GabrielaA ´ ngelesdePaza,UlisesConejoSaucedoa, RafaelLeo ´ nMorcilloa,#,andElisabetArandaa,b

a INSTITUTEOFWATERRESE ARCH,UNIVERSITYOFG RANADA,GRANADA,SPAIN

b DEPARTMENTOFMICROBIO LOGY,UNIVERSITYOFG RANADA,GRANADA,SPAIN

1.Introduction

Fungi,belongingtoEukarya,arehighlydiverseandlessexplored.Theyarecosmopolitan andplayimportantecologicalrolesassaprotrophs,mutualists,symbionts,parasites,or hyperparasites.Advancesinmolecularphylogenyhaveallowedtoclarifythecomplex relationshipsofanamorphicfungi(fungiimperfecti)andtoplacesomeofthemoutside thefungi.Exitingprogresshavebeenmadeindevelopingfungiformodernandpostmodernbiotechnology,suchasobtainingenzymes,alcohols,organicacids,pharmaceuticals, orrecombinantdeoxyribonucleicacid(DNA).Filamentousfungiandyeastsareextensivelyusedasefficientcellfactoriesintheproductionofbioactivesubstancesandmetabolitesorfornativeorheterologousproteinexpression.Thisisduetotheirmetabolic diversity,secretionefficiency,high-productioncapacity,andcapabilityofcarryingout post-translationalproteinmodifications.Thecommercialexploitationoffungihasbeen reportedformultipleindustrialsectors,suchasthoseinvolvedintheproductionofantibiotics,simpleorganiccompounds(citricacids),fungicidesorfoodandbeverages.

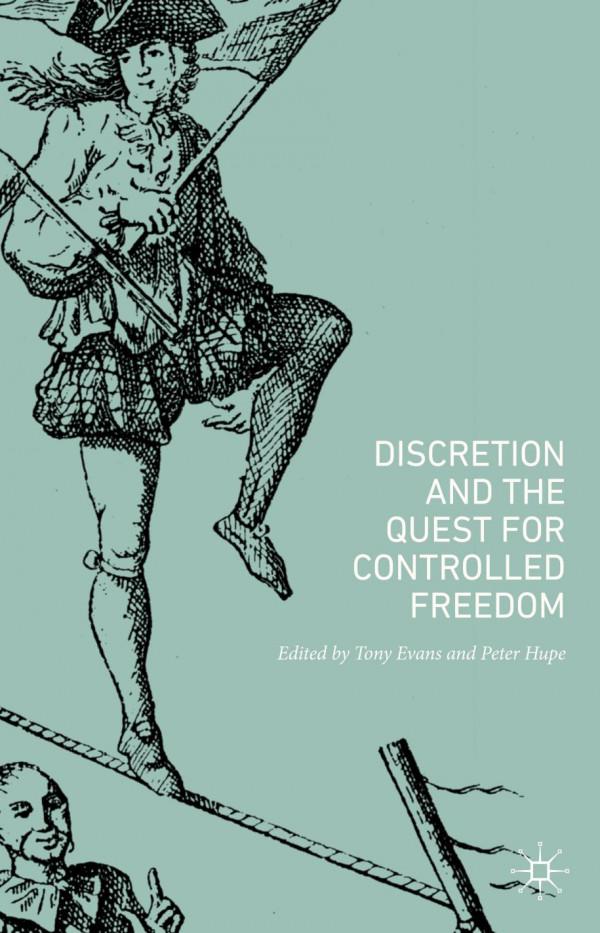

2.Fungalmorphology

Fungicancolonizenewplacesbygrowingasasystemofbranchingtubes,knownas hyphae,whoseaggregatesformthe mycelium (filamentousfungi).Myceliumcanbefound inthesubstrateswherethefungigrowthorbelowgroundandplayanimportantrolein obtainingnutrientsforgrowthanddevelopment.Thehyphaearecharacterizedbythepresenceorabsenceofsepta,cross-wallsthataredistinctiveamongdifferenttaxonomicgroups. TheyareabsentinOomycotaandZygomycota,knownas coenocytichyphae (koinos ¼ shared,kytos ¼ ahollowvessel).ThepresenceofseptaisacommonfeatureofBasidiomycotaandAscomycota,inwhichtheexchangeofcytoplasmororganellesisensuredbyseptal

#Currentaffiliation:InstituteforMediterraneanandSubtropicalHorticulture“LaMayora”(IHSM),CSICUMA,CampusdeTeatinos,Ma ´ laga,Spain.

CurrentDevelopmentsinBiotechnologyandBioengineering. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-91872-5.00010-7

Copyright © 2023ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

pores.Theseporescanbesimpleordolipores,poreswithadistinctivemorphologythat haveabarrel-shapedswellingthatsurroundsthecentralpore(Fig.1).Undersenescence processes,differentiationorsimplyundermechanicalbreakingoff,differentorganelles actasseptalporeplugs,preventingthedetrimentaleffectoftraumasenescenceorpermittingdifferentiationprocesses.TheyincludeWoroninbodies,hexagonalcrystals,elongated crystallinebodies,nuclei,mitochondria,ordenovodepositionofpluggingmaterial (Markham,1994).Theseptumrepresentsaspecializedstructureforcelldivision.

Notallfungigrowashyphae;someoccurasyeasts(yeast-likefungi).Theyusually growonsurfaceswherepenetrationisnotrequired(suchasthedigestivetract).Suchfungi haveattractedtheattentionofbiotechnologistsbecausetheygrowrapidlyandcaneasily bemanipulated.Otherfungicanswitchbetweenyeast-likefungiandfilamentousfungi; theyareknownas dimorphicfungi andincludesomepathogenssuchastheplantpathogen Ustilagomaydis orthehumanpathogen Candidaalbicans.Thisattributeishighly importantasamodelofdifferentiationineukaryoticorganisms(Bosscheetal.,1993). Dimorphismisacommontreatinpathogenicfungi(animalsandplantspathogen)and usuallyisregulatedbydifferentfactorssuchastemperature,glucose,pH,nitrogensource, carbondioxidelevels,chelatingagents,transitionmetalsandinoculumsizeorinitialcell density(Romano,1966).However,anumberoffungiwithunknownpathogenicactivity haveimportantindustrialapplicationssuchastheproductionofchitosan,chitinfrom Saccharomyces,bioremediationprocessby Yarrowia,ethanolorenzymeproduction (Doiphodeetal.,2009).Thisfactisofspecialinterestinindustry,since(i)itispossible toovercometheoperationalproblemsgeneratedduringhyphalgrowthinbioreactors, (ii)morphologycouldbeanindicatorofbiotechnologicalprocess(enzymessecretion orproliferationvspenetration),or(iii)canbeanadvantageforbiocontrolformulations (Doiphodeetal.,2009).

Fromapointofviewofbiotechnology,themorphologyoffungihasanimportant implicationsincetheadaptationofthecultivationsystemmustbeoptimized.

FIG.1 Septumtypesinfungalhyphae.

Filamentousfungicangrowthasdispersemycelialorpellets,dependingonthemechanicalconditionsofthecultivation.Industrialcultivationprocesseswithfungihavebeen optimizedoverdecadestoincreaseproductivity( WalkerandWhite,2017).

Thefungal cellwall isadynamicandcomplexstructureandusuallybasedonglucans andchitin(Ruiz-Herrera,1991).However,thechemicalcompositionvariesamongdifferenttaxonomicgroups,withimplicationsforbiotechnologicalprocessessincedifferent enzymaticactivitiesoccurinthecellwall.Thebalancebetweenwallsynthesisandlysis couldinfluencehyphalmorphologyandcellgrowth,withimpactsontheretentionof chemicalcompoundsthroughbio-adsorptionprocesses,enablingthesuccessfulindustrialfermentationoffilamentousfungi.Inaddition,somecomponentsofthecellwall, suchaschitosanandchitinareconsideredhigh-valueproductsfortheiruseinbiomedicine,agriculture,papermaking,foodindustry,andtextileindustrythatcanbeeasily extractedusingdifferenttechnologies(Nweetal.,2011; Table1).

2.1Generalaspectsofreproduction

Fungicanreproducesexuallyorasexually(vegetativereproduction).Thesetworeproductionmodesdifferaccordingtothefungalmorphologyandtaxonomicgroup(yeast,filamentous,ordimorphicfungi)(Hawker,2016).Inyeasts,themostfrequentmodeof vegetativereproductionisbudding,whichhasbeenstudiedindetailfor Saccharomyces cerevisiae.Thismodecanbemultilateral,bipolar,unipolar,ormonopolarbudding.However,fissionbyformingaseptumcanalsooccurinyeastssuchas Schizosaccharomyces pombe (hostforheterologousexpression).Thisfissioncanbebinaryorabudfission, inwhichacross-wallatthebaseofthebudseparatesbothcells.Ballistoconidiogenesis isaspecificvegetativereproductioninspeciessuchas Bullera (β-galactosidase)or Sporobolomyces (carotenoidsandfattyacids).Pseudomyceliaaretypicalindimorphicspecies inwhichasinglefilamentisproducedwhencellsfailtoseparateafterbuddingorfission ( WalkerandWhite,2017).Infilamentousfungi,suchasbasidiomycetes,thisvegetative reproductioncanoccurbyfragmentationofthehyphae;insomeascomycetes,theformationofmitoticsporeshasbeenobserved.Sexualreproductionisacomplexmechanism anddiffersaccordingtothetaxonomicgroups;itinvolvestheformationofameioticspore byplanogameticcopulation,gametangialcontact,gametangialcopulation,spermatization,andsomatogamia.

Table1 Percentagesofdryweightofthetotalcellwallfractionofthemain components(chitin,cellulose,glucans,protein,andlipids)indifferentgroupsoffungi.

GroupChitinCelluloseGlucansProteinLipids

Oomycota0256542

Chytridiomycota5801610n/a Zygomycota904468

Ascomycota1–39029–607–136–8

Basidiomycota5–33050–812–10n/a n/a(Datanotavailable).

DataadaptedfromRuiz-Herrera,J.,Ortiz-Castellanos,L.,2019.Cellwallglucansoffungi.Areview.CellSurf.5,100022.

2.2Fungalnutrition

Filamentousfungiandyeastsarechemo-organotrophmicroorganismswithrelativelysimplenutritionalneeds.Fungiareheterotrophicorganismssincetheylackphotosynthetic pigments.Mostfungiareaerobes,butwecanfindrepresentativesofobligateanaerobes (Neocallimastix )orfacultativeanaerobes(Blastocladia).Inaerobicrespiration,theterminalelectronacceptorisoxygen;however,basedonoxygenavailability,wecanfindobligate fermentativeorfacultativefermentativefungi,includingCrabtree-positive(Saccharomyces cerevisiae),Crabtree-negative(Candidautilis),non-fermentative(Phycomyces,Rhodotorularubra)orobligateaerobes(mostfungi)( WalkerandWhite,2017).

2.2.1Nutrientuptake

Filamentousfungiandfewyeastspeciesobtaintheirnutrientsviaextracellularenzymes; theyabsorbsmallermoleculesproducedafterextracellulardigestion.Theseenzymescan bewall-bound-enzymesormaydiffuseexternallyintotheenvironment,dependingonthe lifestyleofthefungus(Section3).Nutrientdistributionthroughthehyphaemightoccur bypassive(diffusion-driven)oractivetranslocation(metabolicallydriven)throughthe protoplasm(OlssonandGray,1998; Perssonetal.,2000).Inbothcases,nutrienttranslocationallowsfilamentousfungitogrowthinhabitatswherethespatialdistributionof nutrientsandmineralsisirregularandvariable,includingenvironmentswithlownutrient concentrationsorpollutedareas,byexploitingtheresourcesavailableinotherpartsofthe mycelium(Boswelletal.,2002).

Theenzymaticsysteminfungidependsonthetaxonomicgroup.Someecophysiological artificialgroupshavebeenestablishedbasedonthecapabilitytoproduceenzymes.These groupsincludetheformerligninolyticfungibecauseoftheirabilitytosecreteasetofenzymes involvedinthedegradationoflignin.Theseenzymesplayasignificantroleinbiotechnology sincetheycanbeusedinbiorefineries.Theyincludelipasesproducedbysomeyeasts (Candida, Yarrowialipolytica),hydrolyticenzymessuchasglycosidehydrolases(GHs),polysaccharidelyases(PLs),glycosyltransferases(GTFs),carbohydrateesterases(CEs),lyticpolysaccharidemonooxygenases(LPMOs),non-catalyticcarbohydrate-bindingmodules (CBMs)andenzymeswith“auxiliaryactivities,”includingallenzymesinvolvedinlignocellulosicconversionsuchaslaccases,peroxidases,manganeseperoxidase,ligninperoxidases, versatileperoxidases,DyP-typeperoxidases(Levasseuretal.,2013).TheseenzymesareclassifiedintheCAZymesdatabase,whichdescribesthefamiliesofstructurallyrelatedcatalytic andCBMsofenzymesthatdegrade,modify,orcreateglycosidicbonds(http://www.cazy. org/).Theseenzymesareimportantinbiotechnology,particularlyinbiorefineries,forthe deconstructionofplantbiomassintosimplesugarstoobtainfermentation-basedproducts andfortherecoveryofvalue-addedcompounds(Contesinietal.,2021).

3.Lifestylesoffungi

Fungi,asheterotrophiceukaryoticmicroorganismsandefficientproducersofenzymes, canliveindifferenthabitatsandondifferentorganicsubstrates.Ingeneralterms,fungi

areeither saprophytic—theyfeedonnutrientsfromorganic,non-livingmatterinthesurroundingenvironment-, symbiotic—theyshareamutuallybeneficialrelationshipwith anotherorganism-, parasitic—theyfeedoffalivinghostthatmaysurvive(biotrophs) ordie(necrotrophs)-or hyperparasitic—theyliveattheexpenseofanotherparasites.

Saprotrophicfungi areimportantfortherecyclingofnutrients,especiallyphosphate mineralsandcarbonincorporatedinwoodandotherplanttissues.Theirroleasdecomposersoforganicmatterisfundamental,sincetogetherwithbacteria,theypreventthe accumulationoforganicmatter,ensurethedistributionofnutrientsandplayacrucialrole intheglobalcarboncycleinterrestrialandaquaticecosystems(KjøllerandStruwe,2002; Cebrian,2004; Mooreetal.,2004).Besides,filamentousfungiplayothersignificantrolesin naturalecosystems.Forinstance,interrestrialsystems,fungimaintainthesoilstructure duetotheirfilamentousbranchinggrowthandparticipateinthetransformationofrocks andminerals(Gadd,2008),incorporatingnewelementsintotheecosystemthatmaybe usedbyotherorganisms.

Inadditiontotheimportantroleinnaturalprocesses,andasstatedbefore,thedecompositionoforganicmatterbyfungirepresentsanimportanttraitforbiotechnologicalpurposesduetothepotentialuseofindividualmicrobialstrainsorenzymesfortheuseof renewableresources,suchasplantbiomass.Ingeneralterms,saprotrophicbasidiomycetescandegradeplantlitterandwoodmorerapidlythanotherfungibecauseoftheir highcapacitytodecomposeligninandotherplantpolymers,allowingthemtospreadrapidlyintheenvironment(OsonoandTakeda,2002; Martı´nezetal.,2005; Baldrian,2008). Nevertheless,litterandwooddecompositionisasuccessiveprocess,ofwhichbasidiomycetesandascomycetesgoverndifferentphases(Osono,2007; Vorı´s ˇ kova ´ andBaldrian, 2013).Thiscapacityhasbeenwidelyusedinatindustrialscaleinvariousapplications becauseoftheoxidationofphenolicandnon-phenoliclignin-derivedcompounds.Few examplesarefungallaccases,ligninolyticenzymeswhichdegradecomplexrecalcitrant ligninpolymersandarewidelyusedinthefoodindustry(Minussietal.,2002; MayoloDeloisaetal.,2020),incosmetic,pharmaceutical,andmedicalapplications(Golz-Berner etal.,2004; Niedermeyeretal.,2005; Huetal.,2011; Uedaetal.,2012; Sunetal.,2014),in thepaperandtextileindustry(Bourbonnaisetal.,1995;OzyurtandAtacag,2003; Rodrı´guezCoutoandTocaHerrera,2006;Virketal.,2012)orinthenano-biotechnology (Lietal.,2017; Kumarietal.,2018).Apartfromindustrialapplications,thepotentialcapacityofsaprophyticfungalintra-andextracellularenzymestodegrade/transformcomplex polymers,suchaslignin,isusedinthebiodegradationoforganicxenobioticpollutants. Amongthem,oxidoreductasesrepresentthemostimportantgroupofenzymesusedin xenobioticbioremediationtransformations,includingperoxidases,laccases,andoxygenases,andcancatalyzeoxidativecouplingreactionsusingoxidizingagentstosupport thereactions(Sharmaetal.,2018; Bakeretal.,2019).Theseenzymesareproducedbya widediversityoffungi,whicharesomeofthemostextensivelyfungiusedtodetoxify xenobioticcompounds;theybelongtothebasidiomycetesgroupcalled“whiterotfungi” andincludethegenera Trametes, Pleurotus,and Phanerochaete spp.(Aust,1995; Pointing, 2001; Baldrian,2003; Asifetal.,2017),butalsoascomycetesgenerasuchas Aspergillus or Penicillium (Aranda,2016; Arandaetal.,2017).

Pathogenicandparasiticfungi virtuallyattackallgroupsoforganisms,includingbacteria,otherfungi,plants,andanimals,includinghumans.Accordingtotheirnutritional relationshipwiththehost,parasiticfungicanbedividedintobiotrophicparasites,which obtaintheirsustenancedirectlyfromlivingcells,andnecrotrophicparasites,whichfirst destroytheparasitizedcellandthenabsorbitsnutrients.Besides,fungimightbefacultativeparasites,whicharecapableofgrowinganddevelopingondeadorganicmatter andartificialculturemedia,orobligateparasites,whichcanonlyobtainfoodfromliving protoplasmand,therefore,cannotbeculturedinnon-livingmedia(Brian,1967;Lewis, 1973)Fungipossessthebroadesthostrangespectrumofanygroupofpathogens.For instance,thefilamentousascomycetousfungus Fusariumoxysporum causesvascularwilt onmanydifferentplantspecies(Pietroetal.,2003),butitisalsoresponsibleforcausing life-threateningdisseminatedinfectionsinimmunocompromisedhumans(Boutatiand Anaissie,1997).Nonetheless,therearemanyexamplesoffungalpathogensthatinfect onlyonehost(ShivasandHyde,1997; ZhouandHyde,2001),highlightingthehighhost specificityofdiseasesproducedbycertainfungalinfections.Toexplainthisdualaspectof fungalinfectionspecificity,thepathogenicstrainsofparasiticfungiaredividedinto formaespeciales,definingtheexistenceofdifferentsubgroupswithinspeciesbasedontheir hostspecificity(ArmstrongandArmstrong,1981; Anikster,1984).

Intermsofagriculture,theestimatedcroplossesduetofungaldiseaseswouldbesufficienttofeedapproximately600millionpeopleayear(Fisheretal.,2012).Tocolonize plants,fungisecretehydrolyticenzymes,includingcutinases,cellulases,pectinasesand proteasesthatdegradethesepolymersandpermitfungalentrancethroughtheexternal plantstructuralbarriers.Theseenzymesarealsorequiredforthesaprophyticlifestyle offungi.Asmentionedabove,somefungiarefacultativeparasitesandmayattackplant rootsfromasaprophyticbaseinthesoilthroughthemycelium,progressivelycausingthe deathofthehostandthereafterlivingassaprophytes(ZhouandHyde,2001).Somefungi havedevelopedothermechanismstocolonizeplanthosts,suchasviaspecializedpenetrationorgans,calledappressoria,orviapenetratingthroughwoundsornaturalopenings, suchasstomata(Knogge,1996).

Fungalpathogensareresponsiblefornumerousdiseasesinhumansandfortheextinctionofamphibianandmammalpopulations(Brownetal.,2012; Fisheretal.,2012).For example, Batrachochytriumdendrobatidis,anaquaticchytridfungusthatattackstheskin ofover500speciesofamphibians,and Geomycesdestructans,aascomycetefungusthat attacksnumerousbatspecies,seriouslythreatenthesurvivaloftheseanimalsandmight leadtothedeclineinthepopulationsofotherspecies(Colo ´ n-Gaudetal.,2009; Fisher etal.,2009; Lorchetal.,2011).

Forhumans,fungalinfectionsarerarelylife-threatening;however,superficialfungal infectionsoftheskin,hairandnailsarecommonworldwideandaffectapproximately one-quarterofthehumanpopulation(Schwartz,2004).Airbornepathogenicfungican alsocausedifferentrespiratorydiseasesandalsobelethalinimmunocompromised patients(Mendelletal.,2011).Theinfectionprocessis,generally,similartothatinplants. However,andcontrarytoplantinfections,appressoriahavenotbeendescribedfor

animal-pathogenicfungi,exceptforafewsimilarlyshapedstructuresformedby Candida albicans (Krizniketal.,2005).Insteadtoappressoria,inanimals,fungalpathogensuse othermechanisms,suchasthebindingofspecificreceptorsthatfacilitatetheendocytosis ofhostcellsand,therefore,theirentranceintothelivingtissue( Woods,2003; N € urnberger etal.,2004).Nonetheless,andsimilartofungalinfectionsinplantsandotherfungallifestylessuchassaprophytes,thisprocessmayalsobemediatedbylyticenzymes,suchas proteases,thatdegradethesurfaceofthehostcellsandpermitfungalpenetrationintothe livinghost(N € urnbergeretal.,2004; Schalleretal.,2005).

Aspecialtypeofparasiticfungiisrepresentedby hyperparasites,fungithatliveatthe expenseofanotherparasite,whichishighlycommonamongfungi( JeffriesandYoung, 1994).Hyperparasitismisoftenusedinagricultureforplantprotectionasanalternative tochemicaltreatments(Broz ˇ ova ´ ,2004).Aclassicexampleis Trichodermaharzianum,a fungusextensivelyusedasbiologicalagentagainstawiderangeoffungalparasites.Nonetheless,itisestimatedthat90%ofallfungiusedinplantprotectionproductsbelongtothe genus Trichoderma (Benı´tezetal.,2004).

Fungimayalsoliveas mutualisticsymbionts, associatingwithotherorganismswith benefitsforbothparties.Remarkableexamplesofthesesymbiosesaremycorrhizaeand lichens.Mycorrhizaearethesymbioticassociationofsoilfungiwiththerootsofvascular plants.Generally,fungicolonizeplantrootsandprovidenutrientsandwater,whichare capturedfromthesoilthroughtheexternalhyphalnetwork,whereasplantssupply organicmoleculesderivedfromphotosynthesis,suchassugarsorfattyacids,totheobligatebiotrophicfungi(Harrison,1999; Keymeretal.,2017).Thisrepresentsauniversal symbiosis,notonlybecausealmostallplantspeciesaresusceptibletoformthesymbiosis, butalsobecausesuchsymbiosescanbeestablishedinthemajorityofterrestrialecosystems,evenunderhighlyadverseconditions(Mosseetal.,1981).Moreover,thissymbiosis contributestoglobalcarboncyclesasplanthostsdivertupto20%ofphotosynthatesto thehostfungi(SmithandRead,2010).Therearethreedifferenttypesofmycorrhizae: endomycorrhizae,ectomycorrhizae,andectendomycorrhizae.

Endomycorrhizaearecharacterizedbythepresenceofhyphaeinsidethecellsofthe rootcortex.Itisestimatedthatatleast90%ofallknownvascularplants,(about 300,000species),formthistypeofmycorrhizae.Ontheotherhand,intheectomycorrhizaesymbiosis,thehyphaeofthefungusdonotpenetratethecellsofthecortexoftheroots andformadensehyphalsheath,knownasthemantle,surroundingtherootsurface.Itis believedthatatleast3%ofvascularplantsdevelopthistypeofmycorrhizae,including almostallspeciesofthemostimportantforesttreegenera.Finally,theectendomycorrhizaepresentcharacteristicsofbothendo-andectomycorrhizae,namelyamantlesurroundingtheplantrootsandfungalhyphaethatpenetratetherootcells(Smithand Read,2010).

Mycorrhizalsymbiosisplaysanessentialroleintheestablishmentandfunctioningof terrestrialecosystems,beinginvolvedinnaturalprocessessuchasnutrientcyclingand,in part,inthestructureanddynamicsofpopulationsandplantcommunities(Newman, 1988; Klironomosetal.,2011).Intermsofagriculture,mycorrhizaeimprovethe

productivecapacityofpoorsoils,suchasthoseaffectedbydesertification,salinization, andwinderosion,becauseofthefungalcapacitytoobtainandtranslocatenutrients andwatertothehostplants(George,2000).Inaddition,thesymbiosisenhancessoil aggregationandstructure(MillerandJastrow,2000)andcontributestodefenceagainst diverseplantpathogens(Elsenetal.,2001; Azco ´ n-Aguilaretal.,2002; Garcı´a-Garrido andOcampo,2002)andabioticstresses,suchasdroughtorsalinity(Ruiz-Lozanoetal., 1996; Ruiz-Lozano,2003).

Anotherformofsymbioticassociationoffungiisrepresentedby lichens,whichare compositeorganismscomposedofalgaeorcyanobacteria,called photobionts,living amongfilamentsofafungus,theso-called mycobiont.Thealgae,asanautotrophicorganism,providesthefunguswithorganiccompoundsandoxygenderivedfromitsphotosyntheticactivity,whereasthefungus,asaheterotroph,suppliesthealgaewithcarbon dioxide,mineralsandwater,sincecontrarytoplants,lichenslackvascularorgansto directlycontroltheirwaterhomeostasis(ProctorandTuba,2002; LutzoniandMiadlikowska,2009).Mostofthelichenizedfungalspecies(98%approximately)belongtothe phylumAscomycota,whereasonlyfewordersareinthephylumBasidiomycotaand mitosporicfungi(Hawksworthetal.,1996).Althoughsomelichensinhabitpartially shadedareasandforests(NeitlichandMcCune,1997),mostlichensoftenliveinhighly exposedplacesunderintenselightintensities,suchasdesertsorarcticandalpineecosystems.Forthisreason,themycobiontnormallyproducessecondarycoloredcompounds, called lichencompounds,thatstronglyabsorbUV-Bradiationandpreventdamagetothe algae’sphotosyntheticapparatus(Fahselt,1994).Thesecompoundsareasourceofstructurallydiversegroupsofnaturalproducts,withawiderangeofbiologicalactivitiesincludingantibiotic,analgesic,andantipyreticactivities( Yousufetal.,2014)andhave traditionallybeenusedinthecosmeticanddyeindustryaswellasinfoodandnatural remedies(Oksanen,2006).

Innature,lichensareimportantasearly-stageprimarysuccessionorganisms.For instance,theyarethepioneersinthecolonizationofrockyhabitatsand,afterdying,their organicmattermightbeusedbyotherorganisms(LutzoniandMiadlikowska,2009; Muggia etal.,2016).Aspoikilohydricorganisms,theirwaterstatuspassivelyfollowstheatmospherichumidity(Nash,1996),andtheycantolerateirregularandextendedperiodsof severedesiccation.Thisallowsthemtocolonizehabitsthatcannotbecolonizedbymost plants.Despitethis,manylichensalsogrowasepiphytesonplants,mainlyonthetrunks andbranchesoftrees.However,theyarenotparasitesorpathogenssincetheydonotconsumeorinfecttheholdingplant(Ellis,2012).Inaddition,lichensadsorbandaresensitiveto heavymetalsandpollutants(Garty,2001),makingthemperfectenvironmentalindicators.

4.Taxonomyoffungi

Understandinghowfungihaveadaptedtosomanyecosystems,thewayinwhichthey haveevolved,butaboveall,taxonomicclassification,hasnotbeenaneasytask.Fungi, afterplantsandanimals,areoneofthemostdiverseanddominantgroupsinalmost

allecosystems.Itisestimatedthattherearebetween1.5and5.1millionspecies.However, anewestimationofthenumberoffungirangesbetween500,000andalmost10million (HawksworthandL € ucking,2017),althoughonlyalmost10%havebeenidentifiedsofar (Blackwell,2011;Hibbettetal.,2016)

Inthemiddleofthe18thcentury,thescientistCarlvonLinnaeusimplementedabinomialsystemtoclassifylivingbeings(Systemanaturae).Thissystemisbasedontheclassificationoforganismsaccordingtotheirmorphologicalcharacteristicsandphenotypic traits.Fungiwereconsideredaspartoftheplantkingdom(Linnaeus,1767).Someyears after,Whittakerclassifiedthefungiasanindependentgroup,whichhecalled“truefungi” (Eumycota)( Whittaker,1969).Then,differenttaxonomicclassificationscontinueduntil themiddleofthe19thcentury.Advancesintheclassificationoffungihavealwaysgone handinhandwiththedevelopmentofnewtechnologies,suchaselectronmicroscopy, newbiochemical,andphysiologicalanalysismethods,thestudyofsecondarymetabolites,cellwallcompositionandfattyacidcomposition,aswellasmoleculartechnologies, amongothers(Guarroetal.,1999).

Inthelasttwodecades,thedevelopmentofPCRtechniquesand,later,genome sequencing,hassignificantlycontributedtotheadvanceinfungaltaxonomy.Thispromotedrapidchanges,andtherefore,differentproposalsforthereclassificationoffungi havebeenmade,triplingthenumberofphylafrom4tomorethan12.However,lessthan 5%oftheidentifiedspecieshavebeentaxonomicallyclassified( Jamesetal.,2020).Nextgenerationsequencingtoolshaveallowedfungalgenomesequencing,transcriptomes, andmitochondrialgenomesthatprovidedrelevantinformationforphylogeneticstudies infungi.Additionally,specificregionsofribosomalRNA(rRNA),suchasinternaltranscribedspacers(ITSs),largesubunit(LSU),smallsubunit(SSU)andintergenicspacer ofrDNA,aswellasvariousmarkersincludingtranslationelongationfactor1(TEF1), glycerol-3-phosphatedehydrogenase(GAPDH),histones(H3,H4),calmodulingene, RNApolymeraseIIlargestsubunit(RPB1)genesandmitochondrialgenes(cytochrome c oxidaseIandATPasesubunit6),haveplayedanimportantroleinthedevelopment ofthefungaltaxonomy(Zhangetal.,2017).

Theorganizationofsuchinformation(genomes)bythescientificcommunityhas requireddifferentefforts.Ontheonehand,theY1000+projectaimstosequencethe genomesof1000yeastspecies(https://y1000plus.wei.wisc.edu),andontheotherhand, the1000FungalGenomesproject(http://1000.fungalgenomes.org/home)hastheobjectiveofsequencing1000fungalgenomes.ThedatabaseUNITEisarecentdatabasethat concentratesthesequencesoftheITSribosomalregionoffungiincludedintheInternationalNucleotideSequenceDatabase(http://www.insdc.org/).Thisdatabaseresulted fromthecollaborationofresearchersandtaxonomicspecialistswhocollectedand depositedfungalsequences,specificallywiththepurposeofbuildingadatabasethat registers,analyses,andsharesthisinformationwiththescientificcommunity(Koljalg etal.,2020).

Inthelast14years,thetaxonomyoffungihasbeenundermajorchanges.Thekingdom offungi,proposedby Hibbettetal.(2007),includesonesubkingdom(Dikaria)andseven

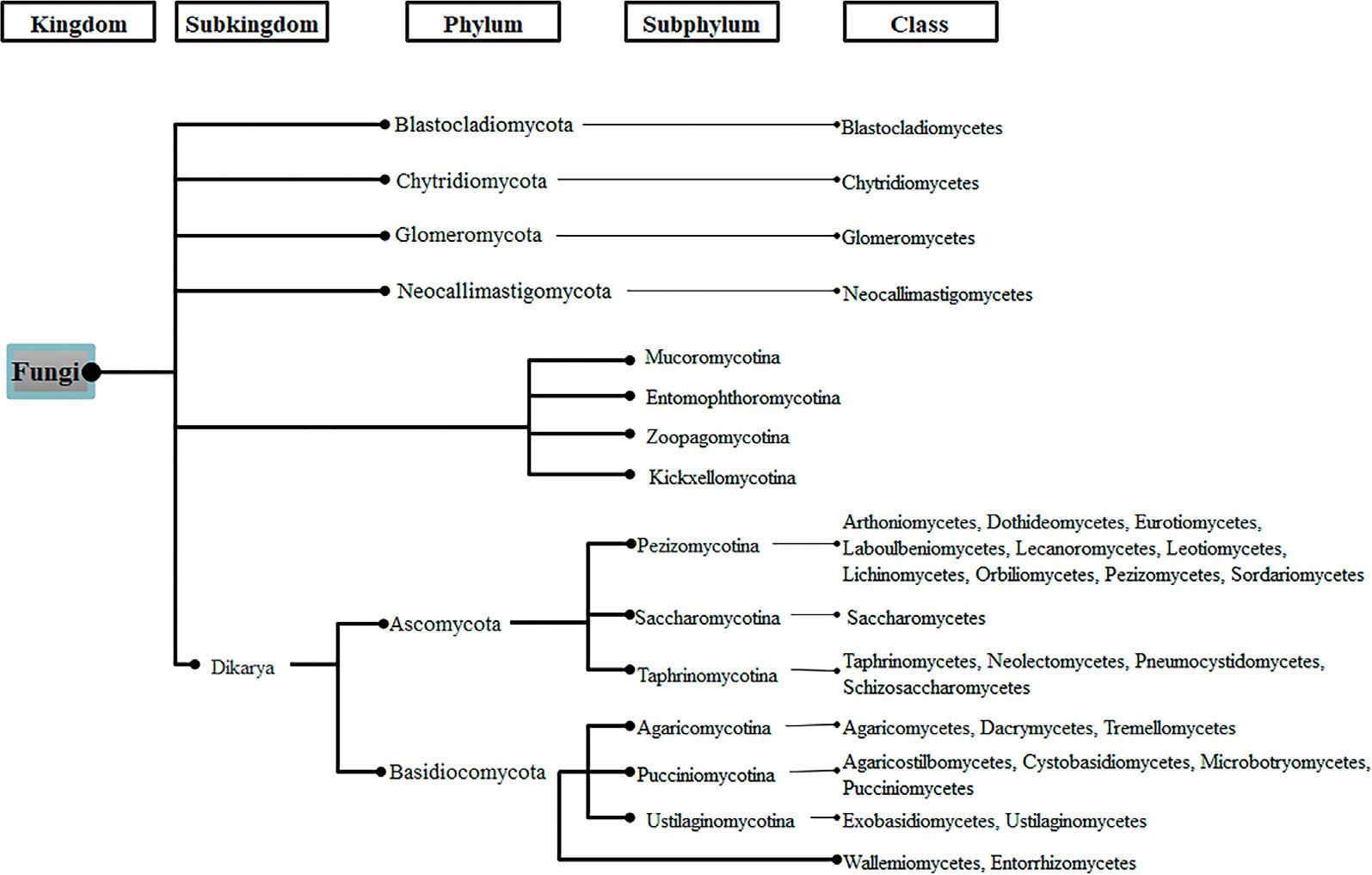

Fungalclassificationproposedby Hibbettetal.(2007)

phyla:Blastocladiomycota,Glomeromycota,Chytridiomycota,Neocallimastigomycota, Microsporidia,Ascomycota,andBasidiomycota;foursubphyla,namelyEntomophthoromycotina,Kickxellomycotina,Mucoromycotina,Zoopagomycotina,andatotalof31classes(Hibbettetal.,2007)(Fig.2).Overthelastfewyears,differentapproaches, reclassifications,andupdatesonfungaltaxonomyhavebeenmade(Gryganskyietal., 2012; Hydeetal.,2013; Slippersetal.,2013; Phookamsaketal.,2014; Ariyawansaetal., 2015; Lietal.,2016; Spataforaetal.,2016; Marin-Felixetal.,2017,2019; Reblova ´ etal., 2018; Voglmayretal.,2019; Mitchelletal.,2021).

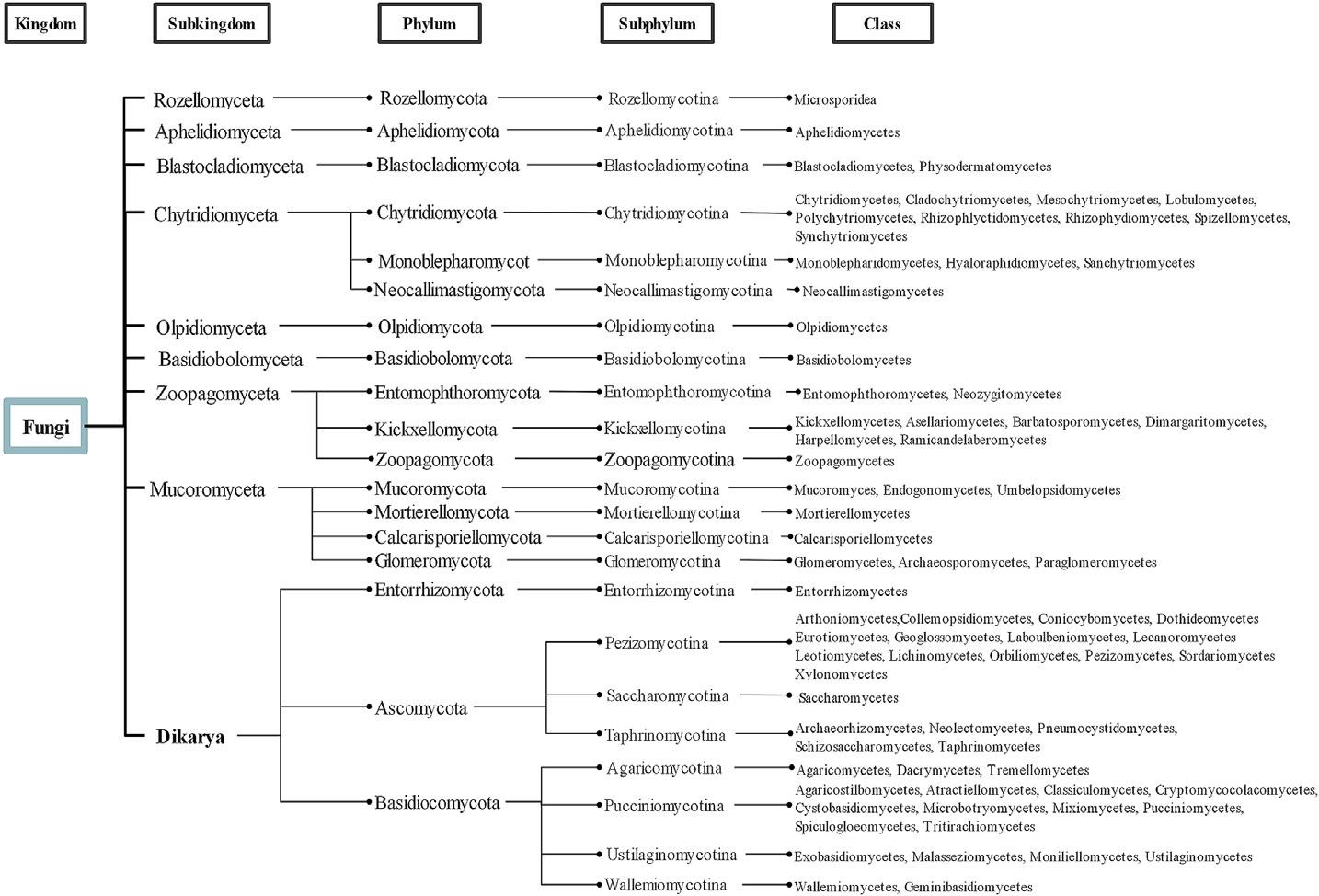

Tedersooetal.(2018) describedandproposedanupdatedclassificationforthefungal kingdombasedondivergencetimeandphylogeniesofparticulartaxa.Underthispointof view,ninesubkingdomshavebeenproposed(1Rozellomyceta, 2Aphelidiomyceta, 3Blastocladiomyceta, 4Chytridiomyceta, 5Olpidiomyceta, 6Basidiobolomyceta, 7Zoopagomyceta, 8Mucoromycetaand 9Dikarya);eachsubkingdomsdividesintooneormorephyla (18phyla-1Rozellomycota, 2Aphelidiomycota, 3Blastocladiomycota, 4Chytridiomycota, 4Monoblepharomycota, 4Neocallimastigomycota, 5Olpidiomycota, 6Basidiobolomycota, 7Entomophthoromycota, 7Kickxellomycota, 7Zoopagomycota, 8Mucoromycota, 8Mortierellomycota, 8Calcarisporiellomycota, 8Glomeromycota, 9Entorrhizomycota, 9Basidiomycota,and 9Ascomycota).Additionally,eachphylumdividesintooneormoresubphyla

FIG.2

FIG.3 Fungalclassificationproposedby Tedersooetal.(2018).

(20subphyla—1Rozellomycotina, 2Aphelidiomycotina, 3Blastocladiomycotina, 4Chytridiomycotina, 4Monoblepharomycotina, 4Neocallimastigomycotina, 5Olpidiomycotina, 6Basidiobolomycotina, 7Entomophthoromycotina, 7Kickxellomycotina, 7Zoopagomycotina, 8Mucoromycotina, 8Mortierellomycotina, 8Calcarisporiellomycotina, 8Glomeromycotina, 9Entorrhizomycotina, 9Agaricomycotina, 9Pucciniomycotina, 9Ustilaginomycotina, 9Wallemiomycotina, 9Pezizomycotina, 9Taphrinomycotina, 9Saccharomycotina),and76classes areincluded(Fig.3).

Analternativeclassificationwasproposedby Naranjo-OrtizandGabaldo ´ n(2019), basedonninemainlines:Opisthosporidia,Neocallimastigomycota,Blastocladiomycota, Chytridiomycota,Mucoromycota,Glomeromycota,Zoopagomycota,Ascomycota,and Basidiomycota.Themaindifferenceswithrespecttootherproposalscanbefoundin theincorporationofOpisthosporidia.Thisgroupincorporatesthreelineages:Rozellidea, Aphelidea,andMicrosporidia.Inturn,thegroupofChytridiomycotawasdividedinto threeclasses:Monoblepharidomycetes,Hyaloraphidiomycetes,andChytridiomycetes, whereasMucoromycotaincludesthetwosubphylaMucoromycotinaandMortierellomycotina.Additionally,BasidiomycotacomprisedPucciniomycotina,Ustilagomycotina, Agaricomycotina,Wallemiomycotina,andBartheletiomycetes.Finally,Ascomycotacontainsthreemainclades:Taphrinomycotin a,Saccharomycotina,andPezizomycotina. Mostrecently,theclassificationoffungiproposedby Wijayawardeneetal.(2020) hascoincided,formanyclades,withtheproposalof Tedersooetal.(2018).Thesubkingdomtaxonomicrankwasremoved,and16 phylawererecognized:Rozellomycota,

Blastocladiomycota,Aphelidiomycota,Monoblepharomycota,Neocallimastigomycota, Chytridiomycota,Caulochytriomycota,Basidiobolomycota,Olpidiomycota,Entomophthoromycota,Glomeromycota,Zoopagomycota,Mortierellomycota,Mucoromycota,Calcarisporiellomycota,andthreehigherfungi(Dikarya-Entorrhizomycota, Basidiomycota,Ascomycota).Inthisstudy,onlyfoursubphylawereproposed (MucoromycotaMortierellomycota,Entomo phthoromycota,andCalcarisporiellomycota);inthecaseofDycaria(AscomycotaandBasidiomycota),sevensubphylaare described(Fig.4).

Somechangesandadditionshavealsobeendescribed,includingthecreationofthe phylumRozellomycotawhichcontainstheclassesRudimicrosporeaandMicrosporidea. TheorderMetchnikovellidawasmovedtotheclassRudimicrosporea,andthemostsignificantchangesoccurredinthephylaAscomycotaandBasidiomycota;theclassBartheletiomycetes,whichwasincludedinthephylumBasidiomycota,waschangedtothe subphylumAgaricomycotina.Moreover,Agaricomycetes,Dacrymycetes,TremellomycetesandBartheletiomycetesweregroupedtogether.FromtheclassCollemopsidiomycetes,thesubphylumPezizomycotinawaseliminated,andnewclasseswereincluded (CandelariomycetesandXylobotryomycetes).TheorderCollemopsidialeswasmoved totheclassDothideomycetes.IntheclassGeminibasidiomycetes,thesubphylumWallemiomycotinawasexcluded,andonlytheclassWallemiomycetesremained.

FIG.4 Fungalclassificationproposedby Wijayawardeneetal.(2020).

Despitetheseefforts,therearelargenumbersofgenera,ordersandfamiliesthathave notyetbeenclassified.OnlyinthephylaAscomycotaandBasidiomycota,remainnot assignedfamiliesfor876genera( Wijayawardeneetal.,2018).Accordingtoacompilation fromtheRoyalBotanicGardens,inthelast10years,350newfamilieshavebeendescribed, includingPucciniaceaewith5000species,Mycosphaerellaceaewith6400species,CortinariaceaeandAgaricaceaeconsistingof3000species.Ontheotherhand,about30%ofthe newincorporationsarebasidiomycetes,whereas68%areascomycetes.Untilnow,the continuouscontributionofdifferentgroupsofresearchers,whichhasresultedinthe growthofdatabases,andthedevelopmentofnewtechnologiesandmoleculartoolshave helpedtoestablishauniversalclassificationforfungi.

Theorganizationofthisenormousamountofinformationthroughtaxonomyallows tocorrelatethedifferentstylesoflifeaswellasthestructural,genetic,andmetabolic characteristics,which,asmentionedhere,areusedtoclassifyfungi.Thistaxonomicpanoramaallowsustoshowthegreatdiversityofspeciesthatexistonearth,studytheirevolutionand,insomecases,takeadvantageofcertainmetabolicfunctionsthatcanbe appliedindifferentindustrialprocesses;mostofthefungiusedbelongtothephylaAscomycotaandBasidiomycota.Thesefungiplayanimportantroleintheproductionofvariousproductsorintermediatesinthegenerationofbioethanol(fungifromthesubphyla Agaricomycotina,Pezizomycotina,andMucoromycotina),biodiesel(fungifromthesubphylaPezizomycotina,Ustilaginomycotina,andSaccharomycotina),biogas(fungifrom thesubphylaMucoromycotina,Agaricomycotina,Pucciniomycotina,Pezizomycotina, Saccharomycotina),thepre-treatmentoflignocellulosicbiomass(fungifromthesubphylaBasidiomycotinaandclassAgaricomycetes),applicationsinthepulpandpaper industry(Agaricomycotina,Pezizomycotina),xylitolproduction(Saccharomycotina), andlacticacidproduction(Mucoromycotina,Saccharomycotina),amongothers (Kumarietal.,2018).

5.Fungaldiversity

Anincreasingnumberofstudiesareaddressingfungaldiversity.Thetotalrichnessand diversityoffungaltaxaacrossthestudiespublishedmainlyinvolveAscomycota(56.8% ofthetaxa)andBasidiomycota(36.7%ofthetaxa),withatotalfungaldiversityofaround 6.28milliontaxa.Thesestudiosrepresentaconservativeestimateofglobalfungalspecies richness(Baldrianetal.,2021).Inthelargeststudyoffungaldiversity,around45,000operationaltaxonomicunits(OTUs)wererecoveredfrom365sitesworldwide,using1.4millionITSsequences( Tedersooetal.,2014).One-thirdofthetotalOTUsshowed97%of similaritycomparedwithothersreportedinpublicdatabases;thereby, 30,000new anddifferentOTUshavebeendetected.Theseresultsgreatlycontributedtothediscovery ofnewfungalspecies.

ThesubkingdomDikarya(AscomycetesandBasidiomycetes)containsmostofthefungaldiversityonearthintermsofdescribedspecies,butissmallcomparedtothesizeofthe totalfungalkingdom.Recently,moretaxahavebeendescribed,suchasCryptomycota

( Jonesetal.,2011;Laraetal.,2010),achytridgroup,Archaeorhizomycetesandothersoil ascomycetegroups(Porteretal.,2008;Roslingetal.,2003;SchadtandRosling,2015).Furthermore,around150generahavebeenestimatedasbeingapartofthefungalgroup calledMicrosporidia,with1200–1300species(Leeetal.,2009);theactualfiguresarepresumablyhigherthanthefiguresforthehostdiversity.However,moleculardiversitystudieshavenotbeendetailedenoughtoelucidatethisinformation(Krebesetal.,2010; McClymont,etal.,2005).

ThoseapproximationshavebeenmadepossibleduetoDNAsequencingandthewidespreaduseoftheformalfungalbarcodeNuclearribosomalInternalTranscribedSpacer ITS1–2.Itisrecognizedastheofficialmolecularmarkerofchoicefortheexploration offungaldiversityinenvironmentalsamples(Ko ˜ ljalgetal.,2013)andcountswithavast andup-to-datedatabase,whichisnecessaryfordataanalysis(Schochetal.,2012).Nevertheless,itcannotdifferentiatebetweenallgroupsandcrypticspecies.Therefore,identificationanddiversityanalysisoffungiisstillgreatlychallenging(DeFilippisetal.,2017). Moreover,therelationshipsbetweenfungaldiversityandtheirenvironmentshavenot beencompletelydescribed,whichisalsothecasefortheprocessesandmechanisms involved(Branco,2019).

Asaconsequence,twodisciplineshavebeenrecognizedtounderstandtherelationship betweenfungaldiversityandtheirenvironment,communityecology,andpopulation genetics(Branco,2019).Communityecologystudiesfocusonthespecieslevel,addressing bothecologicalandbiologicalquestions,withahighlevelofaccuracyandreliability.In contrast,populationgeneticsstudieshavedeterminedspeciesassembliesandranges, comprehendingfungalintra-specificvariation,dispersion,andestablishmentandincludingtheidentificationofkeytraitsinfluencingfitness(MittelbachandSchemske,2015).

Crypticspeciesarebiologicalentitiesthathavealreadybeennamedanddescribed; however,theyaremorphologicallydifferent,andmolecularstudiesareneededtoelucidate,detectandenumeratethesedifferencesatthealphadiversitylevel(Bickfordetal., 2007; HortonandBruns,2001; RappeandGiovannoni,2003; Soginetal.,2006).These studieshighlighttheirdiversitypotential,proposingthemeasurementbygeneticdistancestoknowhowhyper-diversetheyareandtodeterminetheirspecies-leveldifferencesinmanymulticellulargroups.Althoughnovelmoleculartoolsandnewmethods ofidentificationhavebeenusedovertheyears,fungaldiversityisbarelyknown.Thisis mainlyduethespecieswithdifferentmorphologicalandecologicalfeatures (Hawksworth,2004).

6.Fungalecosystems

Asmentionedabove,fungiarehighlydiverseandconstituteamajorportionofvarious ecosystemsintermsofbiomass,geneticdiversification,andtotalbiosphereDNA (Bajpaietal.,2019).Theirdistributionisextraordinarilydiverseandshowsbiogeographicalpatternsdependinguponlocalandglobalfactors,suchasclimate,latitude,dispersal limitation,andevolutionaryrelationships(Bajpaietal.,2019).Intermsofdiversity,the

highestalphadiversityoffungihasbeenfoundinsoilsandterrestrialenvironments, mainlyinplantshoots,plantroots,anddeadwood(Baldrianetal.,2021).Theseassociationswithplantsleadustoinferthatfungiplayadominantroleinterrestrial environments.

6.1Terrestrialecosystems

Fungiinterrestrialhabitatsexhibitdifferentpreferencesrelatedtotheedaphiccondition, withahigherdiversityintropicalecosystems.Fungalendemicityisespeciallystrongin suchregions.Nevertheless,thisdistributiondependsonthegroupofthefungiandtheir features;forinstance,ectomycorrhizalfungiandotherclassesaremostdiverseintemperateorborealecosystems.Ingeneral,severaltaxashowacosmopolitandistribution throughouthabitats( Tedersooetal.,2014).

Sequencingstudieshavebeenperformedindifferentterrestrialenvironments,revealingseveralnumbersofnovelsequencesclusteredconservatively.Forexample,inforest soil,fungaldiversityshowedaround830OTUsthatwerenotmatchedtoanyfungaltaxon previouslydescribedwhenblastedagainstNCBI(http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/)or UNITE(http://unite.ut.ee/) Bueeetal.(2009).Thisanalysisresultedinanestimateddiversityof2240(71.5%)byusingChao1,anon-parametricrichnesstool.Theauthorsalso comparedthesequenceswithacurateddatabaseofrobustlyidentifiedsequencesand foundthat11%ofthetotalsequences,excludingall“unculturedfungi,”remainedunclassifiedandafurther20%belongedtotheunclassifiedDikarya(Bueeetal.,2009).

Fungaldiversityinforestsoilishighlyassociatedwithplants.Theirsymbiosisplaysan importantroleinvegetationdynamics.Moreover,strongrelationandsimilaritiesinfungal alphaandbetadiversitystudies(Hooperetal.,2000; Wardleetal.,2004; GilbertandWebb, 2007)havebeenreportedsince HawksworthandMound(1991) estimatedaround1.5Mof fungalspeciesonlyinthishabitat.Mycorrhizalandsaprotrophicfungiareusuallytheprimaryregulatorsofplant-soilfeedbacksacrossarangeoftemperategrasslandplantspecies;themostabundantfamiliesareParaglomeraceae,Glomeraceae,and Acaulosporaceae,whereasthemostabundantgeneraofsaprotrophicfungiare Mortierella and Clavaria (Semchenkoetal.,2018).

6.2Aquaticecosystems

Aquaticecosystemscomprisethelargestportionofthebiosphereandincludebothfreshwaterandmarineecosystems.Numerousstudiesindifferentaquatichabitatshaveindicatedthatfungiareabundanteukaryotesinaquaticecosystems(Grossartetal.,2019; Money,2016).Theycanreachrelativeabundancesof >50%infreshwaterandabout >1%insalinehabitats(Comeauetal.,2016; Monchyetal.,2011).However,theseresults canbeextremelyvariableanddependontherespectivehabitatanditsenvironmental settings.

Thepredominantfungiinaquatichabitatsaremostlydeterminedbycultivation methods.This,coupledwithtemporaldynamics,spatialconnectivity,andvectorssuch