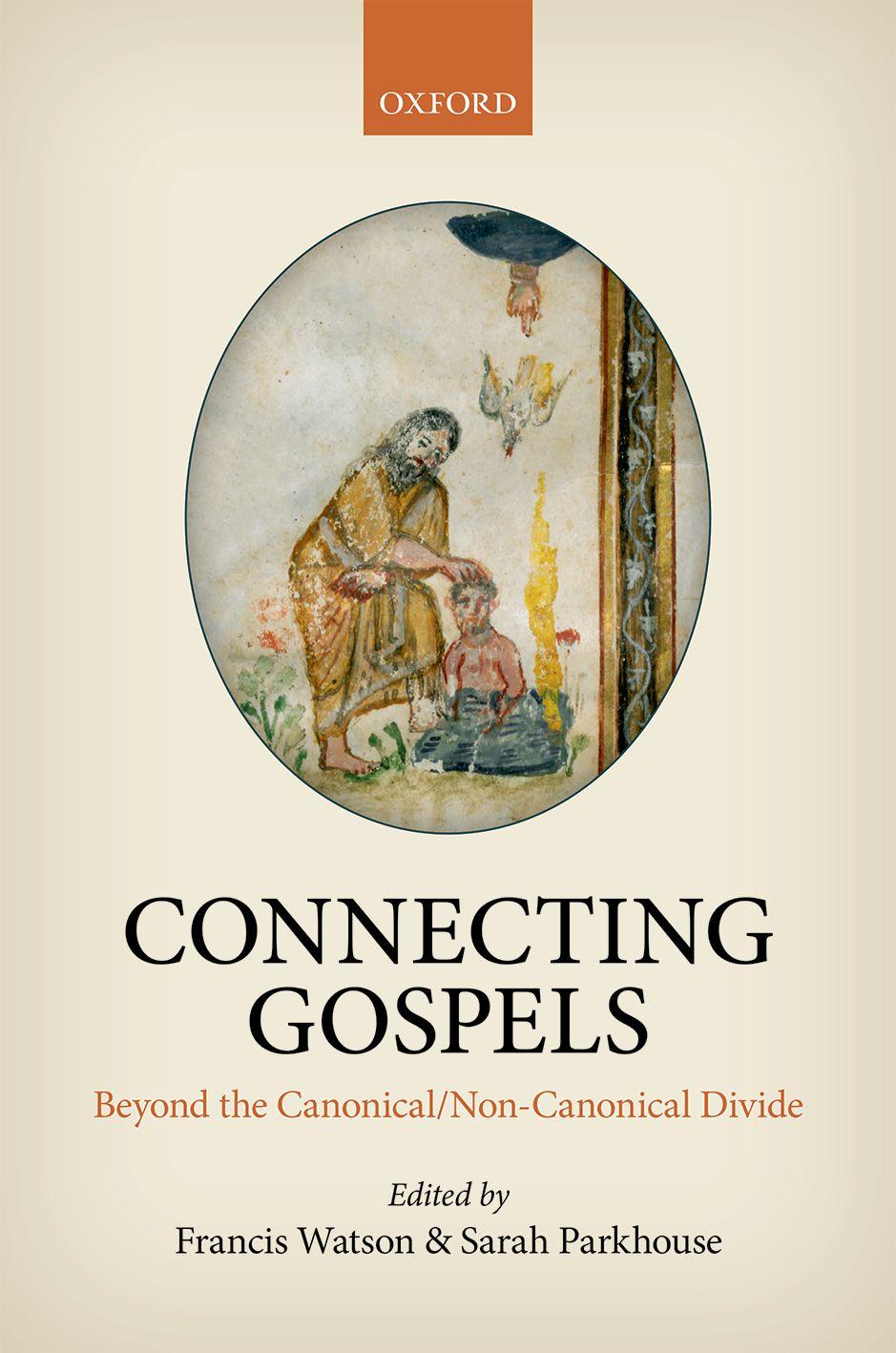

ConnectingGospels

BeyondtheCanonical/Non-CanonicalDivide

Editedby FRANCISWATSON AND SARAHPARKHOUSE

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©OxfordUniversityPress2018

Themoralrightsoftheauthorshavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2018

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2017950110

ISBN978–0–19–881480–1

Printedandboundby CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

Contents

Abbreviations vii

ListofContributors xi

Introduction1

FrancisWatsonandSarahParkhouse

PARTI:BEGINNINGS

1. PraeparatioEvangelica inEarlyChristianGospels15

SimonGathercole

2.Prophets,Priests,andKings:OldTestamentFiguresin Marcion’ s Gospel and Luke 41

DieterT.Roth

3.The ProtevangeliumofJames andtheCreativeRewriting of Matthew and Luke 57

MarkGoodacre

4.Jesus’ Body:ChristologyandSoteriologyintheBody-Metaphors ofthe GospelofPhilip 77

ChristineJacobi

PARTII:MINISTRY

5.RejectionatNazarethinthe GospelsofMark, Matthew, Luke and Tatian 97

MatthewR.Crawford

6.JesusandJudaism:InsideorOutside?The GospelofJohn,the EgertonGospel,andtheSpectrumofAncientChristianVoices125 TobiasNicklas

7.Womeninthe GospelsofMark and Mary 142

ChristopherTuckett

PARTIII:PASSIONANDAFTERMATH

8. ‘MyPower,Power,YouHaveLeftMe’:Christology inthe GospelofPeter 163 HeikeOmerzu

9.AGospeloftheEleven:The EpistulaApostolorum and theJohannineTradition189

FrancisWatson

10.MatterandtheSoul:TheBipartiteEschatologyofthe GospelofMary 216

SarahParkhouse

11.JesusandEarlyChristianIdentityFormation:Reflectionson theSignificanceoftheJesusFigureinEarlyChristianGospels233 JensSchröter

Abbreviations

GOSPELTITLES

EpAp(EpAp)EpistulaApostolorum

GEgerton(GEger) EgertonGospel

GEgyptians(GEgy) GospeloftheEgyptians

GHebrews(GHeb) GospeloftheHebrews

GJohn(GJn) GospelofJohn

GJudas(GJud) GospelofJudas

GLuke(GLk) GospelofLuke

GMarcion(GMcn) Marcion’sGospel

GMark(GMk) GospelofMark

GMary(GMary) GospelofMary

GMatthew(GMt) GospelofMatthew

GPeter(GPet) GospelofPeter

GPhilip(GPhil) GospelofPhilip

GThomas(GTh) GospelofThomas

GTruth(GTr) GospelofTruth

PJames(PJas) ProtevangeliumofJames

OTHERGREEKANDLATINSOURCES

adAutol. Theophilus, AdAutolycum

Adv.Haer. Irenaeus, AdversusHaereses

Adv.Ioan. Jerome, AdversusIoannemHierosolymitanumliber Adv.Marc. Tertullian, AdversusMarcionem

Adv.Pelag.Dial. Jerome, AdversusPelagianosDialogiIII Ant. Josephus, AntiquitatesJudaicae

1Apol. Justin, FirstApology

c.Cels. Origen, ContraCelsum

Comm.inIoh. Origen, CommentaryonJohn Comm.inMatt. Origen, CommentaryonMatthew

viii

Abbreviations

DeCarn.Chr. Tertullian, DeCarneChristi

DeBapt. Tertullian, DeBaptismo

Dial. Justin, DialoguewithTrypho

Exc.Theod. ClementofAlexandria, ExcerptaexTheodoto

Hist.Eccl. Eusebius, HistoriaEcclesiastica

Hom.inLuc. Origen, HomiliesonLuke

Or.Graec. Tatian, OratioadGraecos

Pan. Epiphanius, Panarion

Ref. Hippolytus, Refutatioomniumhaeresium(Philosophoumena)

Strom. ClementofAlexandria, Stromata

Tim. Plato, Timaeus

Vit.Phil.DiogenesLaertius, VitaePhilosophorum

OTHERCOPTICSOURCES

Ap.Jas. ApocryphonofJames

Ap.John ApocryphonofJohn

CGLCopticGnosticLibrary

Dial.Sav. DialogueoftheSaviour

Exeg.Soul ExegesisontheSoul

NHCNagHammadiCodices

Trim.Prot. TrimorphicProtennoia MODERNSOURCES

ABAnchorBible

ABRLAnchorBibleReferenceLibrary

AJBIAnnualoftheJapaneseBiblicalInstitute

AnBibAnalectaBiblica

ARWAWAbhandlungenderRheinisch-WestfälischenAkademieder Wissenschaften

AugAugustinianum

BBRBulletinforBiblicalResearch

BCNHTBibliothèquecoptedeNagHammadi,Textes

BECNTBakerExegeticalCommentaryontheNewTestament

BETLBibliothecaephemeridumtheologicarumlovaniensium

BTBBiblicalTheologyBulletin

BZNWBeiheftezurZeitschriftfürdieneutestamentlicheWissenschaft

CBQCatholicBiblicalQuarterly

CSCOCorpusscriptorumchristianorumorientalium

DCLSDeuterocanonicalandCognateLiteratureStudies

ECEarlyChristianity

EKKEvangelisch-katholischerKommentarzumNeuenTestament

ETLEphemeridesTheologicaeLovanienses

ExpTExpositoryTimes

GCSDiegriechischenchristlichenSchriftstellerderersten[drei] Jahrhunderte

HNTHandbuchzumNeuenTestament

HTBHistoiredutextebiblique

HTRHarvardTheologicalReview

ICCInternationalCriticalCommentary IntInterpretation

JBLJournalofBiblicalLiterature

JECSJournalofEarlyChristianStudies

JEHJournalofEcclesiasticalHistory

JRTheJournalofReligion

JSNTJournalfortheStudyoftheNewTestament

JSNTSuppJournalfortheStudyoftheNewTestament,SupplementSeries

JTSJournalofTheologicalStudies

JTSAJournalofTheologyforSouthernAfrica

KEKKritisch-exegetischerKommentarüberdasNeueTestament

LNTSLibraryofNewTestamentStudies

NHMSNagHammadiandManicheanStudies(formerlyNHS)

NHSNagHammadiStudies

NICNTNewInternationalCommentaryontheNewTestament

NIGTCNewInternationalGreekTestamentCommentary

NovTNovumTestamentum

NovTSuppNovumTestamentum,Supplements

NTSNewTestamentStudies

NTTSDNewTestamentTools,StudiesandDocuments

PLMigne,PatrologiaLatina

RBLReviewofBiblicalLiterature

SBLSocietyofBiblicalLiterature

SBLDSSocietyofBiblicalLiteratureDissertationSeries

SBRStudiesoftheBibleandItsReception

SEPTSeptuagintCommentarySeries

SNTSMSStudiorumNoviTestamentiSocietasMonographSeries

SNTUStudienzumNeuenTestamentundseinerUmwelt

STACStudienundTextezuAntikeundChristentum

StPatStudiaPatristica

StPatSuppStudiaPatristicaSupplements

TANZTexteundArbeitenzumneutestamentlichenZeitalter

TENTTextsandEditionsforNewTestamentStudy

TQTheologischeQuartalschrift

TUTexteundUntersuchungen

TUGALTexteundUntersuchungenzurGeschichtederaltchristlichen Literatur

VCVigiliaeChristianae

VCSuppSupplementstoVigiliaeChristianae

WMANTWissenschaftlicheMonographienzumAltenundNeuen Testament

WUNTWissenschaftlicheUntersuchungenzumNeuenTestament

ZACZeitschriftfürAntikesChristentum

ZNTZeitschriftfürNeuesTestament

ZNWZeitschriftfürdieneutestamentlicheWissenschaft x Abbreviations

Introduction

FrancisWatsonandSarahParkhouse

Itisnormal,anditseemsentirelynatural,tospeakof ‘thegospels’ or ‘thefour gospels’.Inanimportantsensetheseexpressionsarefullyjustifiedandshould notbetoohastilydismissedasarbitrary,restrictive,orconfessionallybiased. ThattheNewTestamentcanonicalcollectionincludesfour ‘gospels’—accounts ofJesus’ ministry,teaching,andtheoutcomeofhislife isastatementnot offaithbutoffact,andthisfactisrootedinalongandunbrokenhistoryof communalusethatmaybetracedbacktothesecondcentury.Likeall historicalfacts,however,thecomingintobeingofafour-gospelcollection wasa contingent event:itmighthavebeenotherwise,itwasnotinevitable. Alternativewaysofconstructingthechurch’sdefinitivegospelwereavailable, whetherbyacceptingonetextonlyorbyacknowledgingtheauthenticvoiceof Jesusinanindefiniterangeofliteraryembodiments.Nodoubtmanyfactors wereinvolvedinthewidespreadadoptionofthefourfoldgospelandthe resultingrejectioninprincipleofothergospelsorgospel-liketexts.Only fragmentaryevidencesurvivesofwhatmusthavebeenagradualtrend towardsrelativeuniformity,butitseemslikelythatacommunitymaking primaryuseofthe GospelofMatthew intheearlysecondcenturywouldhave adoptedthefour-gospelcollectionbythemiddleofthethird.Reasonsforthis collectivedecisionforalimitedpluralitycannolongerbetracedindetail,and that ‘decision’ mayhaveconsistedsimplyinagradualtendencytoassimilate andharmonizecommunalusage.Itislikelythatthoseearlytheologianswho explicitlydefendedtheconceptofafourfoldgospelwereproposingaconsensuswithsomebasisinexistingpractice.Thecounter-intuitiveideathat ChristiancommunitieseverywhereshouldformallyacknowledgefourinterrelatedyetdivergentrenderingsofthecoreChristianstorycouldhardlyhave beenpureinvention.Equallycounter-intuitiveforsome,nodoubt,wasthe exclusionofpopulargospelsorgospel-liketextsapartfromthecanonicalfour. Modernscholarlystudyofthegospelshasgenerallybeencontenttofollow thecanonicaldecision,ontheassumptionthatthecanonical/non-canonical

dividehasitsobjectivebasisinfundamentalcharacteristicsofthetexts themselves.Thatmayperhapsbethecase.Yet,givenanintenseshared focusonthe figureofJesus,thedifferenceisunlikelytobesoabsoluteasto precludecomparisonandcontrast.Ratherthanfocusingprimarilyon ‘thefour gospels’,perhapswithjustapassingmentionofnon-canonicaltextsortextfragmentssuchasthe GospelofThomas,the GospelofPeter,orthe Egerton Gospel,wemightenvisageabroaderobjectofstudy,thatofearlyChristian gospelliteratureviewedasasinglethoughdifferentiated field.Framedinthis way,thefourfoldcanonicalgospelwouldbeseentoemergeoutofamore extensiveliteraryactivityinwhichtraditionsaboutJesus’ earthlylifeand teachingwereshapedandcreated presumablyinresponsetopopulardemand forgospel-likeworksfromaburgeoningChristianreading-and-listening public.Itmaybethatthefoursoon-to-becanonicalgospelswerecomposed significantlyearlierthantheirnon-canonicalcounterparts,thatthecanonical gospelsalonepreserveauthenticrecollectionsofthehistoricalJesus,and thatthedistinctionbetweencanonicalandnon-canonicalgospelsrefl ects fundamentaldifferencesofformorcontent.Evenifthesepointsareconceded(andtheymightnotbe),itremainsthecasethatproductionofgospels orgospel-liketextscontinueduncheckedduringtheintervalbetween thecompletionofthelatestofthecanonicalgospels the GospelofJohn or perhaps Luke andIrenaeus ’ proposalthatafourfoldgospelcouldand shouldbeacknowledgedbyall.

Ifwetakeaselectionofnon-canonicaltexts forexamplethe ProtevangeliumofJames,the GospelofMary,andthe MarcioniteGospel threepoints areimmediatelyclear.The firstisthatthesetextsaremorediverseandless homogeneousthanthecanonicalcollection,wherethereisbroadagreement aboutformandcontentinspiteofallthewell-knowndifferences. PJames is partofatrendperceptiblealreadyin GLuke,balancingtheprimitiveemphasis ontheendofJesus’ earthlylifewithanequalandoppositeemphasisonits beginning,whichistracedbackheretotheconceptionandbirthofhismother Mary.In GMary,anotherMary presumablytheMagdalene emergesoutof thecircleofdespairingmaledisciplesfollowingJesus’ departure,communicatingarevelationaboutthedestinyofthesoulthatleavesheraudience divided. GMarcion iscloselyrelatedto GLuke,butopensnotwithanarrative accountofthecircumstancesofJesus’ birthbutwithhissuddenandunheraldeddescentfromheaveninthe fifteenthyearoftheEmperorTiberius.These arethreeverydifferenttextswithlittleifanyoverlapbetweenthem,andtheir differencesshowthatgeneralizationsaboutthecharacterofnon-canonical gospelsshouldbeventuredonlywithcaution.1

1 Thepresentvolumeemploysauniformformatfortitlesofbothcanonicalandnoncanonicalgospels: GMatthew (GMt), GThomas (GTh), PJames(PJas),etc.

Thesecondpointarisingfromoursampleofthreeisthatthedistinction betweencanonicalandnon-canonicalgospelsisrelativetothecommunitiesin whichtheyareregardedassuch.Marcionitecommunitiescontinuedto flourishlongafterthedeathoftheirfounder,andinthatcontextthecanonical gospelwastheoneinwhichtheLorddescendeddirectlyfromheavento embarkonhisministryofhealing,teaching,andrevealingtheunknown Father.Atextreveredasauthoritativeinoneuser-communitymayseemto embodyfalsehoodandheresyforanother.The GospelofJudas mayhavebeen understoodbyitsearlyusersasimpartingahigherwisdomthatsetthemapart fromtheordinaryChristiansofthemainstreamchurchwithitsfourfold gospel.Conversely, GJudas isspecificallysingledoutforcriticismbyIrenaeus, the firstgreatadvocateofthefourfoldgospel.2 Evenwithinasinglecommunity,thedistinctionbetweenthecanonicalandthenon-canonicalmaynot havecorrespondedtoactualpractice.Throughitsnarrativeofthe ‘holy family’,thenon-canonical PJames hashistoricallyexercisedafarwiderand deeperinfluenceoverChristianpietyandpracticethanthecanonical GMark.

Third,alltextswithamoreorlesscredibleclaimtobecountedas ‘gospels’ haveafundamentalpointincommon:theyareallcommittedtooneversion oranotheroftheabsolutistclaimthatJesusisthedefinitiveand finalembodimentofthedivinepurposesforhumankind.Noearlygospelorgospel-like textdeviatesforamomentfromthisimperiousclaim,forexamplebypresentingJesusasjustonepropheticvoiceamongothersorasdecisively significantonlywithinalimitedcontext.Intheirdifferentwaysthesetexts allarticulatethebasicChristianaffirmationthatJesusisLordofall.Gospels canonicalandnon-canonicalcomposeasetofvariationsonthiscommon theme.The fieldofearlyChristiangospelliteratureisdiverseanddivided,yet thesharedterms ‘Christian’ and ‘gospel’ gesturetowardsanunderlying coherencethatsetsthesetextsapartbothfromotherliterarygenresdeployed ordevelopedbyChristianwritersandfromnon-Christiandiscourseonthe divine–humanrelationship.Acriticalpaganreaderofaselectionofearly Christiangospelsmightwellhaveconcludedthattheyallsharethesameset of(dubiousandirrational)convictions.

Thisraisesthefurtherquestionsofwhatconstitutesthe ‘gospel’ genreand whatthecriteriaareforassigningatexttothisgenreratherthananother.Ifthe criteriaarebasedonthecanonicalfour,thena ‘gospel’ isanarrativeaccountof theministryofJesusasthebringerofsalvation,culminatinginhisdeath, burial,andresurrection.ThisdefinitionhasitsrootsinthePaulinesummary ofthepreachedgospelinitsearliestform:thatChristdiedforoursins,thathe wasburiedandthenraisedonthethirdday,thatheappearedrepeatedlyto hisfollowers,andthattheseeventswereallanticipatedintheholyscriptures

Adv.Haer. 1.31.1.

(1Cor15.3–7).IfthisPaulineviewisallowedtocontrolthedefinitionof ‘gospel’,somemightarguethatatextsuchas GThomas isnot ‘really’ agospel atall,sinceitlacksthenarrativecharacterandtheemphasisoncrossand resurrectionthatarethehallmarksof ‘real’ gospelssuchastheonesattributed toMatthew,Mark,Luke,andJohn.Itmightalsobearguedthatauthentic gospelsexemplifythegenericconventionsoftheGraeco-Roman bios or vita, the ‘biography’ oftheindividualthatwilloftenproceedinchronological fashionfromthebeginningofsomesignificantindividual’slifetoitsend. Thatwouldeliminatefromthegospelgenreboth PJames,concernedonlywith thebeginningsofJesus’ earthlylife,and GMary,concernedonlywithits(postresurrection)end.EventheMarcionitegospelmightbeexcluded,closethough itistoLuke’s,onthegroundsthatitrejectsthescripturalrootssoimportantto Paulandthecanonicalevangelists.Thusasharpdistinctionhasoftenbeen drawnbetweenthe ‘genuine’ gospelsfoundintheNewTestamentand ‘ apocryphal’ so-calledgospelsthatarenotreallygospelsatall.

Thiscanonicallybaseddefinitionof ‘gospel’ isnotwithoutitsdifficulties, however.First,thefamousPaulinesummaryin1Corinthians15isnotfully representativeevenofPaulhimself:withtheexceptiononlyofthephrase, ‘for oursins’ (v.3),itscreed-likerehearsalofbarefactsomitsanyreferenceto salvation.YetthePaulinegospelismostfundamentally soteriological discourse.Itis ‘thepowerofGoduntosalvation’ (Rom1.16),itscontentand goalbeingthesalvationofitshearersasembodiedinthe figureofJesus. Second,theoralproclamationofthedeathandresurrectionofChristisnotat allthesameasanarrativetextinwhichmuchmoreissaidaboutJesusthan thathediedandwasraised.ThereisoverlapbetweenthePaulinegospeland thefourwrittengospels,butthedifferencesofmediaandcontentarenot negligible.Third,withtheexceptionof GMark (cf.1.1,etc.)thecanonical evangelistsshowlittleinterestintheterm ‘gospel’,whichisindeedentirely absentfrom GLuke and GJohn. IfMarkisconcernedtorelatehistexttothe Paulineproclamation,theothercanonicalevangelistsarenot.Onlyatalater stagearethesetextsdescribedas ‘gospels’ andequippedwithcoordinatedtitles usingthe ‘gospelaccordingto... ’ formulation.

Theterm ‘gospel’ speaksoftheannouncementofsalvationthroughJesus, andthisisnotrestrictedtoasinglemediumorformat.Onthiscriterion GThomas isnolessagospelthan GMatthew.Thisispurelyamatterofgeneric classification,anddoesnotimplyanyclaimtoequalstatusorvalidity.The historicChristiancommunityhasjudgedthatthestatusandvalidityofthese twotextsisquitedifferent,andithaseveryrighttodoso,justasanyonehasan equalrighttoquestionitsjudgement;andyettheclassificationofbothtextsas ‘gospels’ remainsunaffected.Ifancientscribesappendedtobothtextsthetitle, ‘Gospelaccordingto... ’,itistoolatetoeraseit.Sinceliterarygenresare fluid setsofconventionswhichtendtooverlapandinterminglepromiscuously, anomalousorborderlinecasesareonlytobeexpected. GPhilip isacollection

oflooselyconnectedmeditations,onlysomeofwhichhaveanycloselinksto thecontenttypicalofothergospels.The EpistulaApostolorum (EpAp)has muchstrongerlinkstosuchcontent,yetpresentsitselfintheformofaletter. TheboundaryseparatingearlyChristiangospelsfromotherearlyChristian literaturewillbemuchlesssharplydefinedthanthecanonicalboundary.Some textsshouldclearlyberegardedasgospels,othersasgospel-like,othersstillas textswithsomegospel-likefeatures.Thepointisnottocreateanewboundary butrathertoacknowledgethat,withthecanonicalembargolifted,textsas diverseas GPeter, GTruth,andtheso-called Diatessaron allfallwithinthe scopeofearlyChristiangospelliteratureasawhole.Indeed,itisprecisely withinthatwider fieldthatthefourfoldcanonicalgospelcomesintobeingas anewcompositetextinitsownright,greaterthanandotherthanthesum ofitsparts.

EarlyChristiangospelliteraturemaybestudiedasasingle field.Suchan endeavourwouldnot flattenoutdifferences.Itdoesnotimplyequalvalidity foreverytextthatpresentsitselfasagospel.Itisnotmotivatedbyanimus againstthegospelsoftheNewTestamentorbyapartisandesiretochampion theirmarginalizedrivalsattheirexpense.Itdoesnotattempttoundothe canonicaldecision.Yetviewingearlygospelliteratureasawholedoesrequire onetogetbehindthatdecisionandnottoberestrictedbyit.Oneoutcomeof suchaparadigmshiftwillbetodiscovernewperspectivesonthecanonical textsthemselves perspectivesinaccessibletoascholarshipconfinedtothe familiarrepertoireofissuesandapproachesthathavedevelopedaroundthe Synopticgospelsand GJohn.

Theaimofthepresentbookistoexplorewaysinwhichthestudyofearly Christiangospelsmightproceed.Theapproachtakenistoseek connections acrossthedividebetweencanonicalandnon-canonicalgospelsbywayof thematiccomparisons. Thusfarnon-canonicalgospelshavetypicallybeen studiedinrelativeisolationfromeachother,anddiscussionoftheirrelation totheircanonicalcounterpartsisnormallyconfinedtoissuesofsource criticism.ManyscholarshavedoneandcontinuetodooutstandingpioneeringworkonthegospelsattributedtoJudas,Mary,Peter,orThomas,onthe MarcionitegospelortheTatianic Diatessaron;yettheinterconnectionsbetweenthesetextsandtheircanonicalcounterpartsarerarelyexplored.Study ofthecanonicalgospelstypicallyproceedsasthoughnoothergospelsexisted, secureinthequestionableassumptionthatnon-canonicaltextsaretoolate andtoodifferenttoimpingeontheroutinesofnormalgospelscholarship.

Aspractisedhere,theprojectof connectinggospels doesnotimplyanybias towardssimilarityattheexpenseofdifference.A ‘connection’ simplymarksa pointatwhichonegospelmayusefullybereadinthelightofanother.In Saying52of GThomas,Jesuscriticizeshisdisciples’ appealtoprophetic scripture: ‘Youhaveomittedtheonelivinginyourpresenceandhavespoken ofthedead.’ In GMatthew repeatedappealismadetopropheticscriptureto

confirmandilluminatewhatissaidaboutJesus.Thispointofcontrastremains a ‘connection’ inthesenseemployedhere.Juxtaposedinthisway,thetwo textshighlightacrucialissueonwhichearlyChristiansdisagreed,thequestion whethertheclaimofJesusisself-authenticatingorwhetheritscredibility dependsonthesupportofnormativeancienttexts.Dividedintheanswers theygive,thetwoevangelistsneverthelessengagewiththesamequestion: whatrole,ifany,shouldthepropheticscripturesplayinthepresentationof Jesusasbringerofsalvation?ThereisnoneedtoclaimthatThomas’ negative answertothisquestionisrespondingdirectlytoMatthew’spositiveone, thoughsuchaclaimmightnotbeimplausible.Thepointissimplytodismantlethebarrierthatsooftenseparatescloselyrelatedtextsandtoreadeachfrom thestandpointoftheother.That,inessence,iswhatcontributorstothis volumeareallattemptingtodo.

ThevolumehasbeenorganizedtofollowtheoutlineofJesus’ career,from itsantecedentsthroughtheministrytohisdeathandresurrection anoutline onwhichcanonicalandsomenon-canonicaltextsarebasicallyagreed.It compriseselevenchapterstracingthemesacrossearlyChristiangospels;each contributorevaluatesthemes,motifs,andconnectionsbetweengospelsoneither sideofthecanonical/non-canonicaldivide.Thethematicapproachcanaccommodatewidedifferencesofmethodologyandperspective.Ratherthandictating eitherasynchronicoradiachronicapproach,orpresupposinganyparticular stanceonthestatusofthefourfoldgospel,orprivilegingeithersimilaritiesor differencesacrossthecanonical/non-canonicaldivide,allthatwehaveasked fromourcontributorsisanappreciationoftheintertextualconnectednessof earlyChristiangospels.Wewillherehighlightafewofthethemesthatrecur throughoutthevolume andthroughoutearlyChristiangospelliterature.

The firsttheme tostartatthebeginningoftheChristianmessageandthe beginningofthevolume isthequestionof wherethegospelstorybegins.Fora numberofgospelwriters,theJesuseventswereconsideredtobethefulfilment ofscripture;forothers,Jesus’ comingwasunheraldedbyanysuchpreparation.Thosewhopenned GEgerton, GMatthew,and GPeter belongtothe formercamp;Marcion,tothelatter.SimonGathercoleaddressesthisquestion toothergospels,arguingthat GTruth prefacesthe evangelium witha praeparatioevangelica intheformofaprotologicalmyth;thatthe Gospelofthe Egyptians undercutsscripturebymeansoftheeven-more-ancientSeth;and that GPhilip understandsChristiansalvationtohavebeenanticipatedthroughouthistoryinsacramentalimagesandsymbols,suchasthehumankissingthat depictstheholykissthatconceivesgrace. GMarcion,conversely,makesitclear thattheOldTestament/HebrewBibleforetoldnothingofthesavingactivityof Jesus;and,aswehaveseen, GThomas isequallyforthrightinitsrejectionofany antecedentrevelation,referringtotheprophetsofIsraelas ‘dead’ .

Inlaterchapters,DieterRothandChristineJacobifocuson GMarcion and GPhilip respectively.Rothshowswhyandhow GMarcion,withallits

similaritiesto GLuke,doesnotcontainthe ‘childhoodgospel’ (GLk 1–2)and genealogy(GLk 3.23–38)thattracesthebeginningofJesus’ storybacktothe storyofIsraelandapiouscommunitythatawaitsthecomingoftheMessiah. ThisaccordswithMarcion’swell-knowninsistencethattheFatherofJesusis tobedifferentiatedfromthedeityoftheOldTestamentandhisconsequent rejectionofanypositivecorrelationbetweenJesusandIsrael.Jacobiexplores GPhilip’sclaimthatMary’sconceptionbytheHolySpirit(cf. GMt 1, GLk 1)is erroneous:JesushasahumanfatherandtheSpiritonlycomesintoplayatthe Jordan.Philip’sversionofthegospelstoryiscomparabletoMark’sinatleast onerespect thatitbeginsatthebaptism.Thisquestionofthebeginningof thegospelappearsagaininMarkGoodacre’sexaminationof PJames,which takesyetanotherstanceonthisissue:ratherthanstartingfromthebirthofthe Messiah(GMt 1.18)ortheparentsofJohntheBaptist(GLk 1.5–7),this gospel-liketextplacesthebirthofMary,herperpetualvirginity,andher DavidiclineageattheoutsetoftheJesusstory.

Acloselyrelatedthemeistheissueof whereJesusstandsinrelationto Judaism,andthisisaddressedbyTobiasNicklaswithafocuson GJohn and GEgerton.Nicklasnotesaconvergencebetweenthetwointhat,forboth evangelists,JesusisclearlyaJewish figurewhoisunderstoodthroughtraditionalJewishcategories;yetneithergoasfarastodepicthimteachingTorah, as GMatthew does.Nicklasconstructsa ‘spectrumofJewishness’,stretching from GJudas, GThomas,and GMary onthenon-(orevenanti-)Jewishside, and GEbionites and GMatthew ontheotherside,withtheirdemonstrationof Jewishconcernssuchasfoodlawsandgenealogy. GJohn and GEgerton togetherfallinamiddleposition.RothexploreshowMarcion,ratherthan rejectingJewishtraditionoutright(whichwouldbealltoosimpleandstraightforward),reinterpretsthe figuresofcertainOldTestamentprophets,priests, andkings althoughhisreadingcontinuestodifferemphaticallyfromthatof Luke.Rothfocusesonthetransfigurationscene(GLk/GMcn 9.28–36),arguing that,whereasLuke’sintentionistobringJesus,Moses,andElijahintocontact, Marcionintendsconflict:Jesusistheonetobeheard,asopposedtothe ancientJewishprophetandthelawgiverwithwhomJesusmustnegotiate theredemptionofthecreator-deity’senslavedsubjects.ThequestionofJesus andJudaismalsocomesintoplayinHeikeOmerzu’sexaminationof GPeter, andheretootherelationshipisoppositional.Thisnon-canonicalpassion narrativecontinuesthetrajectoryofitscanonicalcounterpartsinassigning blameforJesus’ deathtotheJewishleadersandcrowds.JensSchröterunderstands ‘theJews’ in GPeter torepresentalaterstageoftheJesustradition,the polemicsuggestingasecond-centurycompositionasopposedtotheearlier inner-JewishdebatebetweenthosewhodidanddidnotprofessJesusasthe Christ,asstillin GMatthew.

Afurtherthemevariouslytreatedacrosstheentirerangeofearlygospel literatureisthatofthecoreidentityofJesushimself, thechristologicalquestion.

ItisoftenassumedthattheJesusofthenon-canonicalgospelsattributedto Mary,Thomas,Peter,orPhilipisradicallyatoddswiththecanonicalJesusof Matthew,Mark,Luke,andJohn.Thisvolumesuggeststhatsuchanassumptionneedsnuancing.Omerzu’sexplorationofthechristologyof GPeter questionswhethertheoften-claimed ‘docetic’ tendenciesareactuallypresent, andconcludesthattheyarenot:thesilentandpassiveJesusof GPeter is comparabletotheJesusofcanonicalgospels,asisevidentwhenthechristologicaltitlesemployedinthistext-fragment(Lord,KingofIsrael,SonofGod) areunderstoodwithintheirnarrativecontext. GPeter expandsthecanonical storiesbyrecountingtherisenLord’semergencefromthetomb,showinga specialinterestinhisresurrectionbody athemesharedwith EpAp,asdiscussedbyFrancisWatson,whoemphasizestheextenttowhichtheevangelist behind EpAp isinvestedinconfirmingthe fleshlinessofJesus’ resurrectedbody, inwhichheengagesinasinglecontinuousinteractionwithhisfemaleand maledisciplesratherthan ‘appearing’ totheminaseriesofdiscreteepisodes. While EpAp hasmuchincommonwith GJohn 20,theemphasisfallsonthe physicalexaminationofJesus’ woundsratherthanonthecommand, ‘Donot touchme’ (GJn 20.17).

Thechristologicalquestionisintimatelyrelatedtoagospel’sunderstanding of thesignificanceofJesus’ resurrection:itisastherisenonethathisidentity ismostfullydisclosed.Gospelssuchas GPhilip and GMary understand theresurrectedSaviour-figureinwaysthatdiffersharplynotonlyfrom theircanonicalorproto-orthodoxcounterpartsbutalsofromeachother.In GPhilip,Jesus’ resurrectionispre-ratherthanpost-mortem,forhimselfasitis fortheelect.AlongsidethedescentoftheSpiritatthebaptism,Jacobiconsiders thePhilipevangelist’sunderstandingofthetransfigurationscene comparable totheSynopticaccountsinthatJesustakeshisdisciplesupamountain,but withtheemphasisonhismanifestationofhistrueheavenlynatureratherthan histransfiguredandshiningface(cf. GMt 17.2andpars.).TheJesusof GPhilip existsindisguise:heappearssmalltothesmall,asanangeltotheangels,and asanordinaryhumantoordinarypeople;histrueformcanonlybeseenby thosewhoareworthy(57.28–58.10).AninspectionofJesus’ post-mortem resurrected fleshwouldhardlysitwellwith GPhilip’schristology.AsJacobi shows,thechristologyofthisarguablylatesecond-centurygospelimpliesa looserelationshipbetweenthehumanandthedivineandcollapsesthe distinctionbetweenJesus’ pre-andpost-Easterexistence.Apost-Eastersetting isclearlyenvisagedin GMary,however,andSarahParkhouse’schaptershows howtheMaryevangelistpresentstherisenSaviourastherevealerofdefinitive eschatologicalandsoteriologicaltruths,communicatedinpersonpriortohis finaldepartureandindirectlythroughMaryafterit.Theresultisa ‘bipartite eschatology’ focusinginturnonthequitedistinctdestiniesofMatterandthe Soul. Theindividualcomponentsofthematerialcosmospresentlyexistin unstablecombinationsbutwilleventuallydissolvebackintothe ‘roots’ from

whichtheyoriginated.MeanwhiletheSoulisunaffectedbythedemiseof heavenandearthbutmustnegotiateherwaypastthegatekeepersofthelower heavensuntilsheattainstheRestofherheavenlyorigin aRestthatmaybe anticipatedhereandnowinvisionaryorsacramentalexperience.Distinctive thoughthis ‘bipartiteeschatology’ mayseem,itslinkstoandanalogieswith Jesus’ eschatologicalinstructionascommunicatedelsewhereinearlygospel literaturearemanyandvarious.ThusthecommonChristianunderstanding ofJesusasthesolemediatorandrevealerofthewayto finalsalvationbranches outintoarangeofdifferentappropriations,yetwithunexpectedconvergences manifestingthemselvesacrossapparentlydivergentideologicalstances.

Theportrayalofthedisciples likewiseundergoesalterationsandrevisionsby eachevangelist.Peteristherockof GMatthew, theevangelistof GPeter,heacts asan ‘adversary’ in GMary,andissubordinatetotheBelovedDisciplein GJohn.ChristopherTuckettcomparestheMaryof GMary withthefemale disciplesin GMark.Throughoutthesetwogospels,heargues,womenprovide positiveexamplesofdiscipleship.In GMark,Peter’smother-in-lawandthe haemorrhagingwomanaredescribedinlanguagethatechoesJesus’ actions, suchasrising,serving,andsuffering(1.29–31;5.26).Itisawomanwho anointshim,recognizinghistruestatus(14.3–9).Themaledisciples,onthe otherhand,failtounderstandJesus,desert,betray,anddenyhim,andarethen absentatthecruciallocationsofthecrossandthetomb.Atthetomb,itisthe womenwhoaregreetedbyadivinemessengerwhoinstructsthemtotellthe disciplesthatJesushasrisenandisonhiswaytoGalilee.Butherethewomen fail insteadofrunningtotellthedisciples,they fleefromthemaninwhite andtellnoone(GMk 16.8). GMary followsasimilarpattern:Maryrecognizes thetruthwherethemenfail.SherecallsaprivatevisionfromtheSaviour,in responsetowhichPeterandAndrewaccuseheroflyingandthusputtheir ownsalvationatrisk.Yet,towardstheendofbothgospels,thewomenare portrayedasfallible.Intheoriginalendingof GMark, thewomenatthetomb fleefromtheangelicbeingtheyencounterthere,ignoringhisinstruction becausetheyareafraid(16.8).In GMary,Maryfallssilentandweepswhen shehearsPeter’sandAndrew’saccusationsagainsther,andhastorelyon Levi,anothermaledisciple,forsupport.Attheirculmination,then,both gospelsmakeaU-turn:thewomen’sfallibilityishighlightedalongsidethe men ’s.In GMark,themessageofChrist’sresurrectionisreceiveddespitethe womenbeingsilent;Mary’sweaknessin GMary isdefendedandhergospelis preached.Tuckettconcludesthatboth GMark and GMary sharethekey motifsofhumanfallibility,forgiveness,and,ultimately,discipleship.

EpAp toooffersadistinctiveportrayalofthedisciples.Elevenapostles arelistedascollectiveauthors,yetthenamesareatoddswithotherlists.As Watsonnotes,Peterloseshisprimacy,PeterandCephasareregardedas separateindividuals,andthereisa ‘JudastheZealot’.Likewise,theidentities ofthewomenatthetombdifferfromthecanonicalgospelaccounts.Inthe

Ethiopicversion,thewomenwhovisitthetombarenamedas ‘Sarah,Martha andMaryMagdalene’,whereasthe ‘threewomen’ intheCopticmanuscript arenamedas ‘MarywhoisofMarthaandMaryMagdalene’.Thenarrative makesitclearthatthereareindeedthreewomen,despiteonlytwonames,and theyaremostprobablytobeidentifiedasthesistersMaryandMartha(GJn 11) andMaryMagdalene(GJn 20).Theevangelist,then,hasremovedMaryand MarthafromtheirJohanninecontextofLazarus’ deathandplacesthemat Jesus’ tomb(EpAp 9.2).Thesistersstillbelongatasiteofresurrection,butthe subjectoftheresurrectionhaschanged.Furthermore,inbeingnamedlast MaryMagdalenerelinquishesherleadingroleintheemptytombnarrativesof GMatthew, GMark, GLuke, GJohn,and GPeter.

Athemethatrecursfrequentlythroughoutthisvolumeisthatof theprocess ofgospelcomposition.Eachevangelistdrawsonknowntextsortraditions, creativelyinterpretingandrewritingthem aprocessnotedespecially byCrawford,Goodacre,Roth,andWa tson.MatthewCrawfordapplies aredaction-criticalapproachtothe DiatessaronGospel ( τ ὸ δι ὰ τεσσάρων εὐαγγέλιον),3 withafocusonJesus’ preachinginNazareth,showingthat Tatianadoptsasimilarlycriticalviewofhissourceashispredecessors Matthew,Luke,andMarcion incontrasttotherelativelyfreecomposition of PJames, GPeter,or GThomas.Tatian,then,isasmuchanevangelistasthe canonicalgospelauthor–editors andthe Diatessaron wasandshouldstillbe regardedasagospel.Withasimilarfocusoncompositionalprocess,Goodacre showshow PJames knew,used,andimaginativelyandresourcefullyreworked theinfancyaccountsin GMatthew and GLuke.Atsomepoints, PJames parallelsthecanonicalmaterial;atothers,itisradicallydifferent.Thisevangelistomits,conflates,andexpandsonhissourcematerial,andusesdisagreementsbetween GMatthew and GLuke asaplatformforanewtellingofthe storyofJesus’ birth.Goodacreshowsthatthisevangelistfollowstheexample ofhisSynopticpredecessorsinomittingmaterialthatwouldseemto fitwell intohisownstory:theLukanshepherds(2.8–10)mighthavebeenplaced outsideofthecavein PJames,buttheyarereducedtovanishingpoint.Creative engagementwithearliersourcematerialcanbeexpressedthroughomissionas wellasexpansion. Rothfocusesonthefactthat,forbothMarcionandLuke, theissueisnotsimplyomissionorretentionbutratheracreativeprocess ofinterpretation:bothevangelistsareintheirownwaygrapplingwith theimplicationsofthecomingandmissionofJesus,andeachversionof thegospelshouldbeunderstoodonitsowntermsandnotonlyinrelation totheother.Gospel-writersorauthorsofgospel-likeworksexerciseauthorial freedomtoemend,expand,oromitastheysee fit.AsWatsonshows,this appliesequallytotheauthorof EpAp,especiallyinrelationto GJohn

3 Eusebius, Hist.Eccl. 4.29.6(

Schröterconcludesthevolumewithanoverviewofthedevelopmentof canonicalandnon-canonicalgospelliteratureinearlyChristianitythatdifferentiatesbetweentheformalrecognitionofthefour-gospelcollectionand actualearlyChristianreadingpractices.Hearguesthatthefourgospelswhich weretobecomecanonicalareconnectedonbothliteraryandtheological levels,andthatthisconnectionwasdevelopedatanearlystage.Itisobvious that GMatthew, GMark,and GLuke shareagreatdealincommon,andthat GJohn toorevealsknowledgeoftheSynoptictradition;thelateradditionsof thelongerendingof GMark andthe finalchapterof GJohn strengthenthe convergenceofthefour.Thustheantecedentsofthefour-gospelcollection extendbackbeyonditsexplicitadvocacybywriterssuchasIrenaeusinthelate secondcenturyandOrigeninthethird,accompaniedbyanequallyexplicit rejectionofallothergospels.Inspiteofthisapparentlycleardemarcationof thecanonicalfromthenon-canonical,however,earlyChristianreadingpracticeswerenotsostrict.Somegospels(like GPeter and GHebrews)maynot havebeensimply ‘rejected’;itisjustthattheyultimatelyfailedtogainthesame statusasthefour.Schrötersuggeststhat,whilenon-canonicalgospelsarefor themostpartlaterthanthecanonicalfour,thatdoesnotmaketheminherentlyanddesignedlysubordinatetothem.Rather,thelatertextsrepresent ongoingdevelopmentwithinthegospeltradition,andtheyweregenerally conceivedasalternative,competing,orsupplementaryportrayalsofJesus.

AsSchröternotes,acodexcontainingacanonicalgospelalongsideanoncanonicalonehasneverbeenfound.YetatOxyrhynchusafragmentof GThomas inGreek(POxy1)wasfoundincloseproximitytoafragment of GMatthew (POxy2= P1).Indeed,thetwogospel-booksmayevenhave beenthepropertyofasingleowner.Ifso,thatownermayhavereadeach gospelinfullknowledgeandawarenessoftheother,valuingeachinitsown wayeventhoughonlyoneofthemwasregardedassuitableforliturgical readinginchurch.Suchareadingofcanonicalandnon-canonicalgospels acrossthecanonicalboundaryisalso,inessence,theprojectofthisvolume. Thepointisnottoquestionthesignificanceorintegrityoftheboundary,orto promotetheviewthatallearlygospelliteratureissomehowequalinvalue bothfutileundertakings.Itistosuggestthatnewperspectivesmaybegained notleastonthecanonicalgospelsthemselvesifearlygospelliteratureisviewed asasinglethoughdifferentiated fieldofstudy.