Aquaculture

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/aquaculture

Co-cultivation of Isochrysis galbana and Marinobacter

sp.

can enhance algal growth and docosahexaenoic acid production

Ying-Ying Wang a , Si-Min Xu a , Jia-Yi Cao a, * , Min-Nan Wu a , Jing-Hao Lin a , Cheng-Xu Zhou a , Lin Zhang a , Hai-Bo Zhou b , Yan-Rong Li d , Ji-Lin Xu a, * , Xiao-Jun Yan c

a Key Laboratory of Applied Marine Biotechnology, Ningbo University, Ministry of Education of China, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315211, China

b Fujian Dalai Seed Science and Technology Co. LTD, Ningde, Fujian 352101, China

c Collaborative Innovation Center for Zhejiang Marine High-Efficiency and Healthy Aquaculture, Ningbo University, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315211, China

d Ningbo Institute of Oceanography, Ningbo, Zhejiang 315832, China

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Isochrysis galbana

Marinobacter sp.

Growth-promoting bacteria

DHA

ABSTRACT

Isochrysis galbana, an important diet microalgal species, is widely used in aquaculture and rich in docosahexaenoic acid (DHA). Currently, no efficient strategies are available to steadily enhance the production of its biomass and DHA. It has been reported that algae-associated bacteria can affect the yield of algae and the production of high-value compounds. Here, we identified a growth-promoting bacterial strain Marinobacter sp., which could enhance the growth, the content of chlorophyll a, the maximal photochemical efficiency of PS II (Fv/Fm), and soluble protein content of I. galbana when they were co-cultured, while superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity was decreased. Besides, Marinobacter sp. promoted the production of DHA and up-regulated the expressions of genes involved in DHA synthesis pathway of I. galbana Our study clearly suggested that co-cultivation of I. galbana and Marinobacter sp. could effectively enhance the quality and quantity of microalgae, showing promising applications in improving productivity and sustainability of aquaculture algal rearing systems.

1. Introduction

Microalgae have potential applications as food, medicine, health products, biomass energy, industrial materials, bait in aquaculture and so on (Harun et al., 2010; Hemaiswarya et al., 2011; Matos et al., 2017). Microalgae are rich in nutrients, including proteins, amino acids, pigments, carbohydrates, lipids, vitamins, and some minerals (Buono et al., 2014; Matos et al., 2017; Pradhan et al., 2021). Among them, docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) are the most valuable functional components in microalgal lipids, which have been widely believed to benefit human health (Romieu et al., 2005). Besides, these microalgal nutrients have also been widely used in aquaculture. Microalgae as bait or bait supplements can alleviate the barriers to fish meal farming and have been proved to be a successful replacement for fish meal (Dineshbabu et al., 2019). Some microalgae, such as Thalassiosira pseudonana, are widely cultivated to feed the Pacific oyster Crassostrea gigas and rock scallops (Yaakob et al., 2014). Therefore, the

cultivation of high-quality microalgae and improving their high-value substances are very important for aquaculture.

As one of the most important bait microalgae, I. galbana belongs to the class of Prymnesiophyceae (Matos et al., 2019). Extensive research has shown that I. galbana is widely used to feed bivalve larvae, such as mussels, scallops, clams, and bivalve larvae (Dineshbabu et al., 2019; Tremblay et al., 2007), because it is small in size, easy to be digested, and rich in essential nutritional constituents, such as DHA and EPA. As a potential algal strain with abundant DHA and EPA, it has been observed that I. galbana is not only a good bait for aquaculture seedling but also an important raw material for the development of bioactive substances (Liu et al., 2013). Meanwhile, it is considered to have the potential to achieve industrialization. Therefore, a great deal of attention has been paid to the study of I. galbana recently

To improve the wide application of I. galbana, it is of great significance to enhance its biomass yield. Studies have found that the growth of I. galbana is affected by many abiotic factors, such as light,

Abbreviations: DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; SOD, superoxide dismutase; EPA, eicosapentaenoic acid; BCA, bicinchoninic acid; FAMEs, Fatty acid methyl esters; RT-qPCR, Real-time quantitative PCR; rbcL, ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase; d4FAD, delta-4 desaturase gene; ASE2, delta-9 elongase gene; SFAs, saturated fatty acids; MUFAs, monounsaturated fatty acids; ROS, reactive oxygen species; VF, vibrioferrin. * Corresponding authors.

E-mail addresses: caojiayi@nbu.edu.cn (J.-Y. Cao), xujilin@nbu.edu.cn (J.-L. Xu).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738248

Received 14 December 2021; Received in revised form 21 March 2022; Accepted 8 April 2022

Availableonline11April2022

0044-8486/©2022ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

temperature, salinity, CO2, and nutrients (Alkhamis and Qin, 2013; Cao et al., 2020; Picardo et al., 2013; Sayegh and Montagnes, 2011; Zhang et al., 2014). However, even if the main abiotic factors of the growth environment of I. galbana are controlled under optimal conditions, there are still many problems under large-scale outdoor conditions, reminding us that the growth is also impaired by other factors in addition to the above-mentioned abiotic factors. Algae will release a large number of carbohydrates, amino acids, enzymes, lipids, and other metabolites into the environment during the growth process to form a unique “phycosphere” , which will attract a lot of bacteria-dominated microorganisms (Bell and Mitchell, 1972). In this environment, the extracellular products of algae will stimulate bacterial growth and vice versa. Therefore, the interactions between these two groups and the influence of their interaction on each other are areas of recent research interest. Besides the influence on growth, it has been reported that bacteria also affect the production of high-value compounds of microalgae. For example, Pseudomonas composti promoted the increase in biomass yield and lipid of Characium sp. 46–4 by releasing some unidentified extracellular compounds (Berthold et al., 2019). In addition, Liu et al. (2020) have found that co-culture with probiotic algae-associated bacteria significantly enhances the EPA production of Nannochloropsis oceanica. In the case of I. galbana, Sandhya and Vijayan (2019) have shown that some I. galbana-associated bacteria play a role in promoting algal growth. Moreover, the interaction between them is regulated by various growthstimulating compounds, such as antioxidants, siderophores, and indole3-acetic acid, which can have a significant positive impact on algal growth. However, the relationship between this microalgae and bacteria remains largely unexplored. Therefore, it is urgently necessary to explore the growth-promoting bacteria and their effects on the physiology and metabolism of I. galbana, as well as the interaction mechanism between them.

In the present study, we preliminarily applied different initial algae/ bacteria ratios to explore the effects of I. galbana-associated bacteria Marinobacter sp. on the growth of I. galbana We further evaluated the physiological and biochemical effects of Marinobacter sp. on I. galbana. Collectively, our current findings not only improved the understanding of bacteria-microalgae interactions but also provided an alternative strategy to improve algal production and culture stability.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Culture of microalgae and bacteria

I. galbana 3011 was obtained from the Marine Biotechnology Laboratory of Ningbo University, China. As a culture medium, the seawater was filtered through 0.22-μm cellulose acetate membranes and then sterilized by autoclaving. NMB3 medium used in this study was composed of KNO3 (100 mg/L), KH2PO4 (10 mg/L), MnSO4 H2O (2.5 mg/L), FeSO4 7H2O (2.5 mg/L), EDTA-Na2 (10 mg/L), vitamin B1 (6 μg/ L), and vitamin B12 (0.05 μg/L) (Yang et al., 2016). A photoperiod of 12/ 12-h day/night was applied with a light intensity of 100 μmol photon m 2 s 1 using a cool light fluorescent lamp. The temperature was controlled at 25 ◦ C throughout the experiment. Marinobacter sp. used in this study was isolated from I. galbana culture and preserved in the Marine Biotechnology Laboratory of Ningbo University. Marinobacter sp. was freshly cultured on a 2216E marine medium at 28 ◦ C before experiments.

2.2. Co-culture experiments

Before co-culture experiments, Marinobacter sp. was plated freshly on a 2216E agar medium, and single colonies were grown in the 2216E liquid medium overnight (25 ◦ C, 180 rpm). The freshly prepared bacterial culture broth was centrifuged at 5000 ×g for 5 min, washed twice, and finally resuspended in sterile NMB3 medium. The axenic I. galbana was obtained and maintained as previously described (Cao et al., 2019).

When axenic I. galbana was cultured to an exponential phase (initial cell density of about 1 × 106 cells/mL), the bacterial suspension was added into the algal culture to achieve an algae/bacteria ratio of 1:1, 1:50, or 1:100 (cell counts: cell counts). Axenic I. galbana cultured alone was denoted as the control group.

2.3. Physiological and biochemical determinations of microalgae

To study the physiological and biochemical effects of Marinobacter sp. on I. galbana, the algae/bacteria ratio in the co-culture was 1:100. The content of chlorophyll a, the maximal photochemical efficiency of PS II (Fv/F), soluble protein content, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity of I. galbana in the co-culture and mono-culture systems were measured every 2 days. The content of chlorophyll a was measured as previously described (Bruckner et al., 2008). The absorbance was determined at wavelengths of 630, 664, and 750 nm. The content of chlorophyll a was then calculated using the following equation:

Chl a (μg/mL) = 11.47 × (OD664 OD750 ) 0.4 × (OD630 OD750 )

Fv/Fm was measured by AquaPen, which is a lightweight, hand-held fluorometer intended for quick and reliable measurements of photosynthetic activity in algae. The measurement was performed with a dark-adapted sample. Soluble protein was extracted and analyzed using the bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay with bovine serum albumin as the standard according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration of soluble protein was calculated based on the standard curve drawn. The SOD activity was determined by the xanthine oxidase method at a wavelength of 550 nm according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.4. Fatty acid analysis

For fatty acid analysis, the samples from mono-culture of I. galbana, mono-culture of Marinobacter sp., and their co-cultures were collected on the 14th day post-co-culturing by centrifuging at 10,000 rpm for 10 min. The obtained I. galbana and Marinobancter sp. pellets were prefrozen in liquid nitrogen and dried by the vacuum freeze-drying system for further analysis.

Fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) were purified following the methods with modifications as previously described (Okuyama et al., 1992). Briefly, samples (20 mg) of lyophilized cells were accurately weighed and transferred to culture tubes. Next, 1 mL n-hexane, 15 μL internal standard nonadecanoic acid (1 mg/mL), and 1.5 mL freshly made pyromrcyl chloride (prepared by slowly adding 10 mL of acetyl chloride to 100 mL of anhydrous methanol) were added to each sample in a culture tube and vortexed for 1 min at a slow speed. The tightly capped tubes were heated at 70 ◦ C in a water bath for 2 h. After samples were cooled to room temperature, 2.5 mL of 6% K2CO3 was added, followed by the addition of 1 mL n-hexane. The tubes were vortexed 30s and the upper phase was collected in 2-mL sample bottle, then centrifugated at 3000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was filtered by an organic phase filter membrane, and the filtrate was collected into a 2-mL screw-capped sample bottle. The purified fatty acids were subjected to methylations.

The methyl esters were analyzed using an Agilent 7890B–7000C gas chromatography system equipped with an EI detector. A 100-m-long capillary column CD-2560 (Germany, CNW) was used. The column had an inside diameter of 0.25 mm and a film thickness of 0.2 μm. The temperature program was set as follows. The initial oven temperature was maintained at 140 ◦ C for 5 min, then the temperature was increased to 240 ◦ C at an increment of 4 ◦ C/min; and finally, the oven was maintained isothermally for 30 min. The injector temperature was set at 250 ◦ C. Helium was used as the carrier gas at a constant flow rate of 2.25 mL/min. In each analysis, 1 μL of methyl ester solution was injected into the chromatograph. Fatty acids were identified by comparison of

Y.-Y.

retention times to those of known standards and expressed as % of FAMEs identified. The concentration of each fatty acid was calculated using Qualitative Analysis, B.07.00 software.

2.5. Total RNA extraction

Microalgae were harvested through centrifugation at 10,000 rpm and 4 ◦ C for 10 min. Algal cells were ground into powder in liquid nitrogen. Total RNA was isolated from each sample using an E. Z. N. A.® Plant RNA Kit (OMEGA Bio-Tek) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The concentration and quality of the purified RNA were determined using a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop One spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA).

2.6. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

Briefly, purified RNA was reversely transcribed into cDNA using PrimeScript™ RT reagent Kit with gDNA Eraser (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa, Japan). Gene expression was analyzed through RT-qPCR using a LongGene Q2000A qPCR system (Hangzhou) and TB Greer® Premix Ex Taq™ II (Tli RNaseH Plus) (TaKaRa, Japan). The large subunit gene of ribulose-1,5-bisphosphate carboxylase/oxygenase (rbcL) was used as the reference gene (Han et al., 2019). Primers for delta-4 desaturase gene (d4FAD), d5FAD, d6FAD, and d8FAD were synthesized as previously reported (Huerlimann et al., 2014). The primers for the delta-9 elongase gene (ASE2) were designed using Primer 5. All the PCR primers were listed in Table S1. The relative expressions of target genes were calculated using the 2^-ΔΔCt method as previously described (Cao et al., 2016).

3. Results

3.1. The effects of Marinobacter sp. on the growth of I. galbana

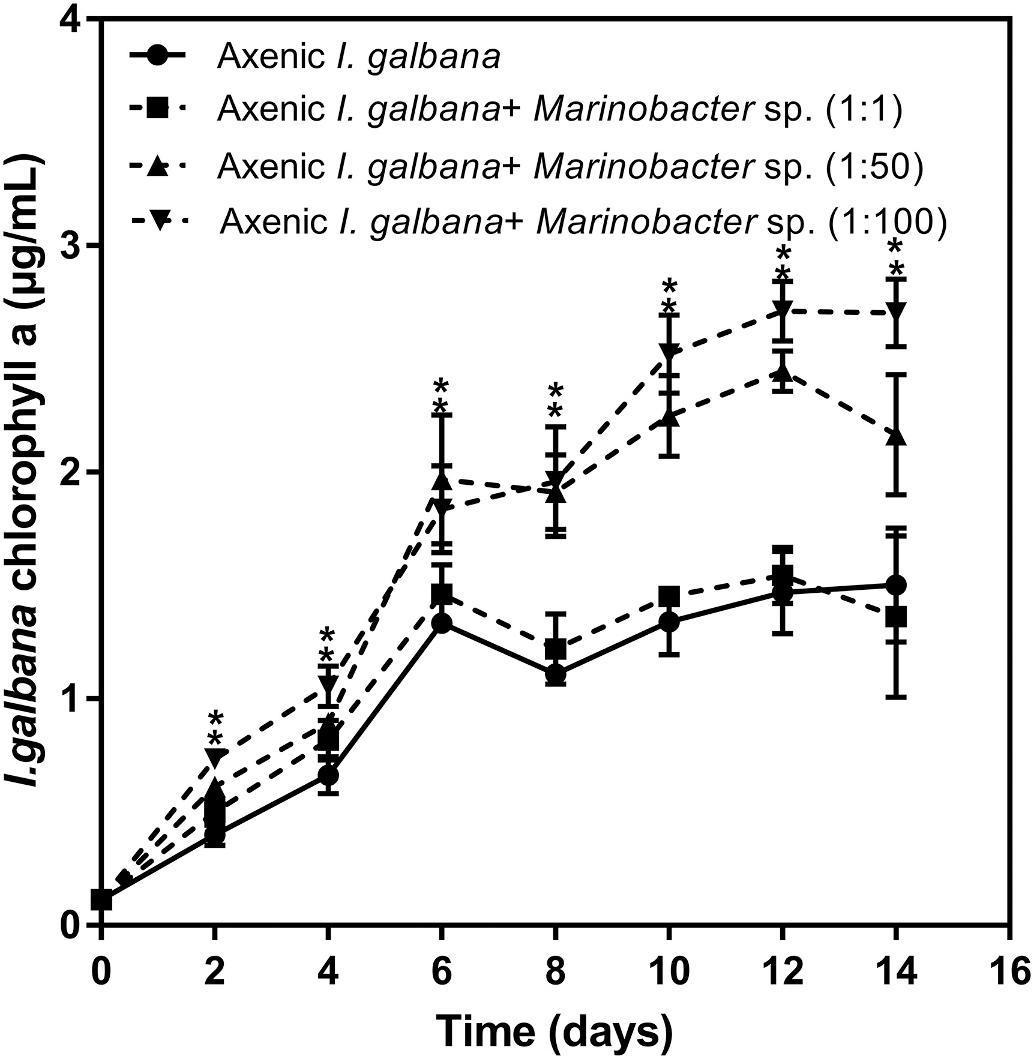

The axenic strain of I. galbana was cultured in the presence of Marinobacter sp. to investigate the effect of Marinobacter sp. on microalgal growth. Fig. 1 shows the effects of Marinobacter sp. with different algae/ bacteria ratios (1:1, 1:50, and 1:100) on the content of chlorophyll a of I. galbana over a period of 14 days. When we explored the effects of Marinobacter sp. on the growth of I. galbana, we found that Marinobacter sp. exerted a growth-promoting effect on I. galbana depending on the population density of the bacteria. Besides, the growth-promoting effects were enhanced with the increase of the treatment duration of bacteria. The presence of bacteria under ratios of 1:50 and 1:100 significantly increased the cell growth of I. galbana compared with the control group. We further detected the cell growth of these two strains during the co-cultivation. The cell growth of I. galbana was enhanced by Marinobacter sp., while the growth of Marinobacter sp. was decreased when compared with pure culture of bacteria from day 4 (Fig. S1). Moreover, no significant effect on the morphology of Marinobacter sp. was found in co-cultivation. For I. galbana, at a later stage of the growth, a large number of deformed algal cells were observed in the monoculture, while no deformation of algal cells was observed in the cocultures (Fig. S2).

3.2. The physiological and biochemical effects of Marinobacter sp. on I. galbana

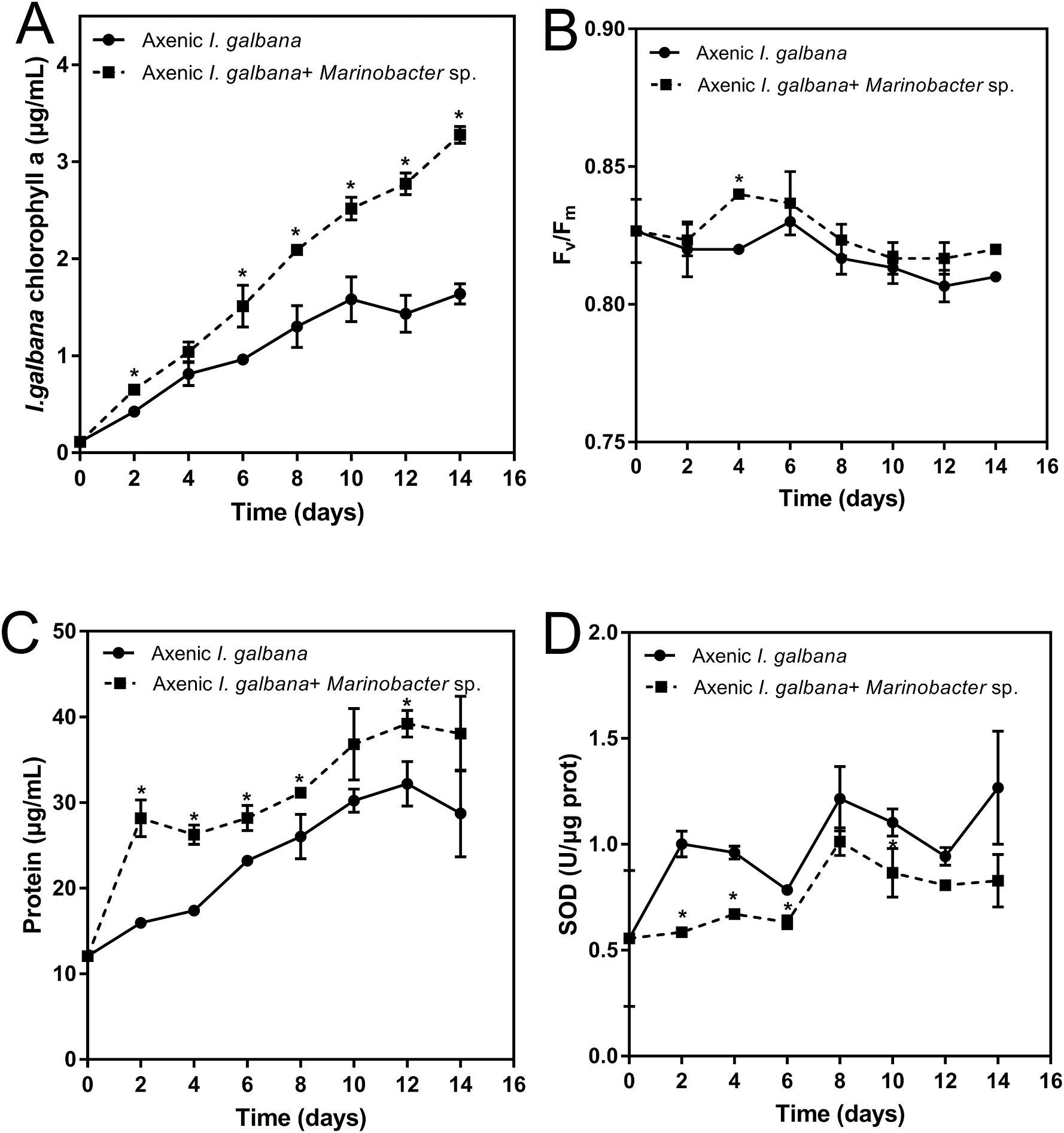

To study the physiological and biochemical effects of Marinobacter sp. on I. galbana, the content of chlorophyll a, Fv/F, soluble protein content, and SOD activity of I. galbana in the co-culture and monoculture systems were compared (Fig. 2). During 14 days of monitoring, the content of algal chlorophyll a in co-cultures was significantly higher compared with the I. galbana mono-culture (Fig. 2A). The chlorophyll fluorescence parameter, Fv/Fm, was used to monitor the effect of Marinobacter sp. on the photosynthetic property of I. galbana. Fig. 2B

Fig. 1. Co-culture results of Isochrysis galbana and Marinobacter sp. with three different initial algae/bacteria ratios (1:1, 1:50, 1:100) expressed as chlorophyll a content over the period of 14 days. Significance of the differences between mean values was determined with Student’s t-test. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate with standard error as error bar, while asterisks (*) indicate significant difference at p value <0.05.

shows that Fv/Fm was higher in the co-culture system during the whole culture process compared with the mono-culture. The results revealed that the photosynthetic property of I. galbana was improved in the presence of Marinobacter sp. The total concentration of soluble protein in the microalgal cells was increased steadily over time (Fig. 2C), showing that the presence of Marinobacter sp. significantly increased the synthesis of soluble protein in I. galbana. The SOD activity in I. galbana was decreased in the co-culture system compared with the mono-culture (Fig. 2D). The presence of Marinobacter sp. inhibited the SOD activity in microalgae during the entire study period. On the 8th day of the experiment, the highest SOD activity was observed in the co-culture, while it was still lower compared with the mono-culture at the corresponding time point. The peak value in the mono-culture on the last day was 1.27-fold higher compared with the co-culture group.

3.3. The effects of Marinobacter sp. on the fatty acid composition of I. galbana

The difference in fatty acid composition of I. galbana in the co-culture and mono-culture systems was analyzed (Table 1-3, Table S2). The most abundant saturated fatty acids (SFAs) in both axenic and co-cultured I. galbana were myristic acid (C14:0) and palmitic acid (C16:0). The specific SFAs obtained from the mono-culture of Marinobacter sp. consisted of dodecanoic acid (C12:0) and tridecanoic acid (C13:0). Additionally, the main SFAs in Marinobacter sp. were C12:0 (22.81 ± 0.66%) and C16:0 (29.91 ± 1.03%). Moreover, we found that the contents of pentadecanoic acid (C15:0), stearic acid (C18:0), and behenic acid (C22:0) were significantly decreased in I. galbana when co-cultured with Marinobacter sp. The levels of total monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) in axenic (27.75 ± 0.62%) and co-cultured (28.46 ± 0.28%) I. galbana were similar. The most abundant MUFA in both axenic and cocultured I. galbana was elaidic acid (C18:1n-9 t). The specific MUFA obtained from mono-cultured Marinobacter sp. was myristoleic acid (C14:1n-5). Besides, the content of heptadecenoic acid (C17:1n-7) was

Y.-Y.

2. Chlorophyll a content (A), Fv/Fm (B), protein content (C) and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity (D) for Isochrysis galbana co-culture and mono-culture during 14 d exposure time. Significance of the differences between mean values was determined with Student’s t-test. All the experiments were carried out in triplicate with standard error as error bar, while asterisks (*) indicate significant difference at p value <0.05.

Table 1

Saturated fatty acid composition (as a percentage of total fatty acids) of Isochrysis galbana co-cultured with Marinobacter sp. for 14 days.

Saturated fatty acids (SFA’s) Axenic I. galbana Axenic I. galbana + Marinobacter sp. Marinobacter sp.

C12:0 ND ND 22.81 ± 0.66

C13:0 ND ND 1.10 ± 0.08

C14:0 8.9 ± 0.13 10.68 ± 0.07* 1.36 ± 0.16

C15:0 1.29 ± 0.09 0.87 ± 0.00* 0.32 ± 0.02

C16:0 15.09 ± 0.37 14.55 ± 0.05 29.91 ± 1.03

C18:0 2.24 ± 0.26 1.14 ± 0.20* 4.36 ± 0.30

C20:0 0.73 ± 0.37 0.24 ± 0.00 ND

C22:0 2.16 ± 0.10 1.20 ± 0.02* ND

± 0.34

ΣSFA

Asterisks (*) indicate significant difference at p value <0.05. ND = not detected.

Table 2

Monounsaturated fatty acid composition (as a percentage of total fatty acids) of Isochrysis galbana co-cultured with Marinobacter sp. for 14 days.

Monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFA’s) Axenic I. galbana Axenic I. galbana + Marinobacter sp. Marinobacter sp.

C14:1n-5 ND ND 0.49 ± 0.02

C16:1n-7 4.22 ± 0.16 5.15 ± 0.06* 7.47 ± 1.50

C17:1n-7 1.13 ± 0.06 0.75 ± 0.01* 1.01 ± 0.18

C18:1n-9 t 19.02 ± 0.22 18.68 ± 0.16 14.80 ± 0.22

C18:1n-9c 2.29 ± 0.09 2.62 ± 0.03* 3.55 ± 0.75

C22:1n-9 1.09 ± 0.09 1.26 ± 0.02 ND

ΣMUFA 27.75 ± 0.62 28.46 ± 0.28 27.32 ± 2.67

Asterisks (*) indicate significant difference at p value <0.05. ND = not detected.

significantly decreased in co-cultured I. galbana The levels of total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) were not significantly changed in axenic I. galbana (40.38 ± 1.78%) compared with the co-cultures (42.05

Fig.

Table 3

Polyunsaturated fatty acid composition (as a percentage of total fatty acids) of Isochrysis galbana co-cultured with Marinobacter sp. for 14 days.

Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA’s) Axenic I. galbana Axenic I. galbana+ Marinobacter sp. Marinobacter sp.

C16:2n-6 0.89 ± 0.08 1.13 ± 0.03* ND

C18:2n-6 5.21 ± 0.54 3.47 ± 0.01 ND

C18:3n-3 6.90 ± 0.10 6.07 ± 0.06* ND

C18:4n-3 10.99 ± 0.41 13.91 ± 0.05* ND

C20:2n-6 0.74 ± 0.07 0.39 ± 0.07* ND

C20:3n-3 0.38 ± 0.04 0.21 ± 0.02* ND

C20:4n-6 0.33 ± 0.06 0.17 ± 0.00 ND

C20:4n-3 0.41 ± 0.08 0.15 ± 0.00* ND

C20:5n-3 1.13 ± 0.12 1.16 ± 0.02 ND

C22:5n-6 2.22 ± 0.14 1.96 ± 0.03 ND

C22:6n-3 11.18 ± 0.14 13.43 ± 0.10* ND

ΣPUFA 40.38 ± 1.78 42.05 ± 0.39 ND

Asterisks (*) indicate significant difference at p value <0.05. ND = not detected.

± 0.39%). Our study clearly suggested that PUFAs were absent in Marinobacter sp. The contents of hexadecadienoic acid (C16:2n-6), stearidonic acid (C18:4n-3), and DHA (C22:6n-3) in the co-cultured I. galbana were significantly increased compared with the axenic I. galbana However, the contents of α-linolenic acid (C18:3n-3), eicosadienoic acid (C20:2n-6), eicosatrienoic acid (C20:3n-3) and eicosatetraenoic acid (C20:4n-3) were significantly decreased compared with the axenic I. galbana.

3.4. The effects of Marinobacter sp. on the expressions of genes involved in DHA synthesis pathway

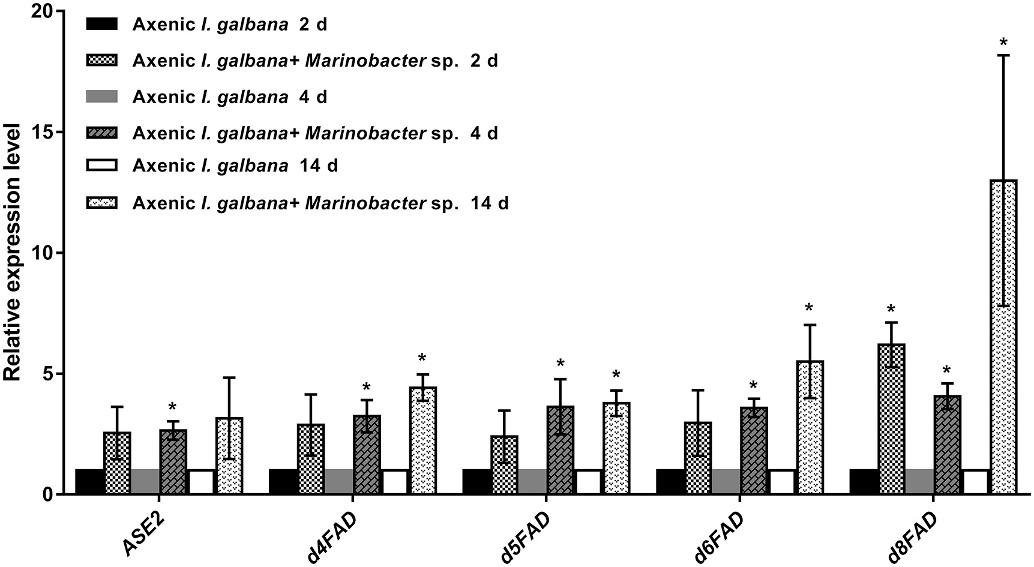

ASE2, d4FAD, d5FAD, d6FAD, and d8FAD are key genes involved in the addition of double bonds and carbon atoms to the growing fatty chain in the DHA synthesis pathway (Fig. S3). Based on RT-qPCR analysis, the expressions of these five genes were all up-regulated in co-cultures compared with the mono-cultures on all three time points (2 d, 4 d and 14 d after co-cultivation) (Fig. 3). Among them, the expression of d8FAD was mostly enhanced (fold change = 12.99) on 14 d.

4. Discussion

I. galbana, as a high-quality bait microalgae species, has been widely used in aquaculture (Tremblay et al., 2007). However, mass cultivation of I. galbana is often impaired by different environmental factors.

Fig. 3. Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis of the expression of genes involved in DHA synthesis pathway (ASE2, d4FAD, d5FAD, d6FAD and d8FAD) in co-culture and mono-culture on three time points (2 d, 4 d and 14 d). RT-qPCR data represent the mean ± standard error of three independent experiments, while asterisks (*) indicate significant difference at p value <0.05.

Therefore, it is necessary to find strategies to improve its production. In our study, we identified a growth-promoting bacterial strain Marinobacter sp. and DHA production of I. galbana can be enhanced by this bacterium. As we known, this was the first study to find a bacterium that can both enhance the algal biomass and DHA production in I. galbana Our results lay a foundation for studying the interaction between algae and bacteria and help improve the yield and quality of bait-microalgae in aquaculture.

When we explored the effects of Marinobacter sp. on the growth of I. galbana, we found that the growth-promoting role of Marinobacter sp. to I. galbana depends on the population density of the bacterium. With the increase of bacterial density, the growth-promoting effects became more obvious (Fig. 1). It is crucial to note that in cultures with a high density of bacterial cells, the availability of light and nutrients to microalgae cells is lower, and the growth rates and yields of valuable compounds, such as carotenoids and fatty acids, decrease (Fuentes et al., 2016). Possibly Marinobacter sp. cell density in our study was not sufficiently high to affect the availability of light and nutrients. Our results also suggested that an appropriate algae/bacteria ratio was a crucial factor to achieve high I. galbana growth in the co-cultivation system. Similarly, the growth-promoting effect of Alteromonas macleodii on I. galbana also depends on the population density of the bacteria (Cao et al., 2021).

Our results also indicated in the presence of Marinobacter sp., the content of chlorophyll a was always significantly higher than that of axenic algal culture (Fig. 2). This finding was consistent with a previous study that Marinobacter sp. has positive effects on the growth of seven microalgal species (Ling et al., 2020). Besides, the co-cultivation of Rhizobium sp. and Ankistrodesmus sp. results in an increment of up to 30% in chlorophyll (Do Nascimento et al., 2013). Likewise, a similar study has shown that the co-immobilization of Chlorella vulgaris and Azospirillum brasilense leads to increments of up to 35% in chlorophyll a (Gonzalez and Bashan, 2000). The increase in the content of chlorophyll a was indeed a manifestation of the algal growth promoted by Marinobacter sp.

Stresses usually lead to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROS). ROS are extremely harmful when their production exceeds the buffering capacity of the antioxidant system (Wang et al., 2019). It is well known that SOD plays a key role in the removal of ROS. We found that the SOD activity of I. galbana was always lower compared with the control group during the co-culture period (Fig. 2). Similarly, co-culture with A. macleodii severely inhibits the SOD activity of I. galbana compared with the control group during the entire study period, which may be related to the ability of A. macleodii to produce extracellular antioxidants (Cao et al., 2021). Whether Marinobacter sp. can produce antioxidants is worthy of further study.

When we explored the effects of Marinobacter sp. on the fatty acid composition of I. galbana, it is interesting to find that the production of DHA was significantly improved by Marinobacter sp. DHA is one kind of important nutrient for aquatic animals. It was reported that higher protein synthesis in microalgae results in elevated expressions of omega3/6 fatty acid biosynthetic genes, namely desaturase and elongase, which subsequently synthesize long-chain PUFAs, such as EPA and DHA (Jeyakumar et al., 2020). As higher protein synthesis was found in coculture, we conjectured that the high protein content might be one reason for the increased content of DHA. Similarly, the proportion of unsaturated fatty acids of C. vulgaris-Mesorhizobium sangaii co-culture was significantly increased compared with the pure algae culture (Wei et al., 2019). They explained that this enhancement in co-cultures might be due to the metabolic regulation and nutrient exchange between microalgae and bacteria.

To further explore the reason for the enhancement of DHA production, the effects of Marinobacter sp. on the expressions of genes involved in DHA synthesis pathway were studied. Our study showed that the expression of ASE2, d4FAD, d5FAD, d6FAD, and d8FAD in the DHA synthesis pathway significantly up-regulated in co-cultures. Therefore,

Y.-Y. Wang

the increased content of DHA in co-cultures might be attributed to that Marinobacter sp. stimulated the expressions of genes involved in the DHA synthesis pathway. Phosphorus, as a major growth-limiting nutrient for microalgal growth, is necessary for synthesizing vital biomolecules, such as DNA, RNA, and phospholipids (including DHA) (Liu et al., 2017). Besides, it is interesting to find that Marinobacter sp. has the ability to decompose and mineralize organic phosphorus. Therefore, we proposed another hypothesis that Marinobacter sp. decomposed and mineralized organic phosphorus by the alkaline phosphatase enzyme to inorganic phosphorus that could be taken up by I. galbana The increased phosphorus intake might be the reason for the increased DHA synthesis. However, additional studies are required to validate this hypothesis.

Marinobacter sp. exists in a wide range of environments, playing an important in the biochemical cycles of the earth, and it can use a variety of carbon sources to interact with metals (Singer et al., 2011). It has been reported that Marinobacter sp. can promote the growth of dinoflagellates and coccolithophores (Amin et al., 2009b). This Marinobacter strain is capable of producing vibrioferrin (VF), an unusual lower-affinity dicitrate siderophore. With the help of VF, the bacteria promote algal assimilation of iron by facilitating photochemical redox cycling of iron (Amin et al., 2009a). However, it has been reported that the VFproducing strains are a small number of strains in the genus Marinobacter, and most strains do not produce VF (Amin et al., 2007; Vraspir and Butler, 2009). It was worth mentioning that we attempted to determine the ability to produce VF of this bacterial strain. However, we did not detect the production of VF in Marinobacter sp. (data not shown). We also attempted to amplify the VF biosynthetic genes, while we didn’t obtain the expected PCR product. Therefore, the mechanism for Marinobacter sp. to promote the growth of I. galbana was not dependent on the VF produced by Marinobacter sp. as reported in dinoflagellates and coccolithophores. It is well studied that bacteria can secrete hormones, e.g. indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), that stimulate the growth and metabolism of microalgae (Amin et al., 2015; De Bashan et al., 2008). Our study showed the potential of Marinobacter sp. to release IAA which might have a significant positive impact on algal growth (Fig. S4). Whether Marinobacter sp. enhances the growth of I. galbana by providing it with IAA merits further study. Taken together, we are sure that the metabolic regulation and nutrient exchange happened between Marinobacter sp. and I. galbana What kind of metabolic regulation and what substances are exchanged merits further investigations.

Collectively, co-cultures of I. galbana and Marinobacter sp. altered the metabolism and fatty acid contents of microalgal cells and increased the levels of DHA. Therefore, such an approach could be applied in highvalue compound production and mariculture of microalgae.

5. Conclusion

In our present study, we selected a bacterial strain with a strong ability to promote microalgal growth and DHA production in I. galbana Co-cultures of I. galbana and Marinobacter sp. altered the growth, the content of chlorophyll a, Fv/Fm, soluble protein content, and SOD activity of I. galbana Besides, the presence of Marinobacter sp. promoted the production of DHA and up-regulated the expressions of genes involved in DHA synthesis pathway. Taken together, our current findings provided valuable insights into the interaction between algae and bacteria and helped improve the yield and quality of microalgae.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ying-Ying Wang: Investigation, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Si-Min Xu: Data curation, Writing – review & editing, Validation, Visualization. Jia-Yi Cao: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing –original draft, Writing – review & editing. Min-Nan Wu: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. Jing-Hao Lin: Validation, Visualization. Cheng-Xu Zhou: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Lin Zhang:

Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing. Hai-Bo Zhou: Writing – review & editing. Yan-Rong Li: Writing – review & editing. Ji-Lin Xu: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Supervision. Xiao-Jun Yan: Conceptualization.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2018YFD0900702; 2018YFA0903003; 2018YFD0901504; 2019YFD0900400), Ningbo Science and Technology Research Projects, China (2019B10006; 2019C10023), Zhejiang Major Science Project, China (2019C02057), China Agriculture Research System of MOF and MARA, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31801724), Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo, China (2019A610416), the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (LY22C190001) and the Natural Science Foundation of Ningbo Government (2021 J114).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi. org/10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738248

References

Alkhamis, Y., Qin, J.G., 2013. Cultivation of Isochrysis galbana in phototrophic, heterotrophic, and mixotrophic conditions. Biomed. Res. Int. 2013, 983465

Amin, S.A., Kupper, F.C., Green, D.H., Harris, W.R., Carrano, C.J., 2007. Boron binding by a siderophore isolated from marine bacteria associated with the toxic dinoflagellate Gymnodinium catenatum J. Am. Chem. Soc. 129, 478–479

Amin, S.A., Green, D.H., Hart, M.C., Kupper, F.C., Sunda, W.G., Garrano, C.J., 2009a. Photolysis of iron-siderophore chelates promotes bacterial-algal mutualism. P. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 17071–17076

Amin, S.A., Green, D.H., Kupper, F.C., Carrano, C.J., 2009b. Vibrioferrin, an unusual marine siderophore: iron binding, photochemistry, and biological implications. Inorg. Chem. 48, 11451–11458

Amin, S.A., Hmelo, L.R., van Tol, H.M., Durham, B.P., Carlson, L.T., Heal, K.R., Armbrust, E.V., 2015. Interaction and signalling between a cosmopolitan phytoplankton and associated bacteria. Nature 522, 98–101

Bell, W., Mitchell, R., 1972. Chemotactic and growth responses of marine bacteria to algal extracellular products. Biol. Bull. 143, 265–277.

Berthold, D.E., Shetty, K.G., Jayachandran, K., Laughinghouse, H.D., Gantar, M., 2019. Enhancing algal biomass and lipid production through bacterial co-culture. Biomass Bioenergy 122, 280–289

Bruckner, C.G., Bahulikar, R., Rahalkar, M., Schink, B., Kroth, P.G., 2008. Bacteria associated with benthic diatoms from Lake Constance: phylogeny and influences on diatom growth and secretion of extracellular polymeric substances. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 7740–7749

Buono, S., Langellotti, A.L., Martello, A., Rinnaa, F., Fogliano, V., 2014. Functional ingredients from microalgae. Food Funct. 5, 1669–1685

Cao, J.Y., Xu, Y.P., Zhao, L., Li, S.S., Cai, X.Z., 2016. Tight regulation of the interaction between Brassica napus and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum at the microRNA level. Plant Mol. Biol. 92, 39–55

Cao, J.Y., Kong, Z.Y., Zhang, Y.F., Ling, T., Xu, J.L., Liao, K., Yan, X.J., 2019. Bacterial community diversity and screening of growth-affecting bacteria from Isochrysis galbana following antibiotic treatment. Front. Microbiol. 10, 994

Cao, J.Y., Kong, Z.Y., Ye, M.W., Ling, T., Chen, K., Xu, J.L., Yan, X.J., 2020. Comprehensive comparable study of metabolomic and transcriptomic profiling of Isochrysis galbana exposed to high temperature, an important diet microalgal species. Aquaculture. 521, 735034

Cao, J.Y., Wang, Y.Y., Wu, M.N., Kong, Z.Y., Lin, J.H., Ling, T., Xu, J.L., 2021. RNA-seq insights into the impact of Alteromonas macleodii on Isochrysis galbana Front. Microbiol. 12, 711998

De Bashan, L.E., Hani, A., Yoav, B., 2008. Involvement of indole-3-acetic acid produced by the growth-promoting bacterium Azospirillum spp. in promoting growth of Chlorella vulgaris J. Phycol. 44, 938–947

Dineshbabu, G., Goswami, G., Kumar, R., Sinha, A., Das, D., 2019. Microalgae-nutritious, sustainable aqua- and animal feed source. J. Funct. Foods 62, 103545

Do Nascimento, M., Dublan, M.D., Ortiz-Marquez, J.C.F., Curatti, L., 2013. High lipid productivity of an Ankistrodesmus-Rhizobium artificial consortium. Bioresour. Technol. 146, 400–407

Fuentes, J.L., Garbayo, I., Cuaresma, M., Montero, Z., Gonzalez-del-Valle, M., Vilchez, C., 2016. Impact of microalgae-bacteria interactions on the production of algal biomass and associated compounds. Mar. Drugs. 14, 100

Gonzalez, L.E., Bashan, Y., 2000. Increased growth of the microalga Chlorella vulgaris when coimmobilized and cocultured in alginate beads with the plant-growthpromoting bacterium Azospirillum brasilense Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 66, 1527–1531

Han, X.T., Wang, S., Zheng, L., Liu, W.S., 2019. Identification and characterization of a delta-12 fatty acid desaturase gene from marine microalgae Isochrysis galbana Acta Oceanol. Sin. 38, 107–113

Harun, R., Singh, M., Forde, G.M., Danquah, M.K., 2010. Bioprocess engineering of microalgae to produce a variety of consumer products. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 14, 1037–1047

Hemaiswarya, S., Raja, R., Kumar, R.R., Ganesan, V., Anbazhagan, C., 2011. Microalgae: a sustainable feed source for aquaculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 1737–1746

Huerlimann, R., Steinig, E.J., Loxton, H., Zenger, K.R., Jerry, D.R., Heimann, K., 2014. Effects of growth phase and nitrogen starvation on expression of fatty acid desaturases and fatty acid composition of Isochrysis aff. Galbana (TISO). Gene. 545, 36–44

Jeyakumar, B., Asha, D., Varalakshmi, P., Kathiresan, S., 2020. Nitrogen repletion favors cellular metabolism and improves eicosapentaenoic acid production in the marine microalga Isochrysis sp. CASA CC 101. Algal Res. 47, 101877

Ling, T., Zhang, Y.F., Cao, J.Y., Xu, J.L., Kong, Z.Y., Zhang, L., Yan, X.J., 2020. Analysis of bacterial community diversity within seven bait-microalgae. Algal Res. 51, 102033

Liu, J., Sommerfeld, M., Hu, Q., 2013. Screening and characterization of Isochrysis strains and optimization of culture conditions for docosahexaenoic acid production. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 97, 4785–4798

Liu, Y., Liu, Y.Q., Cao, X.Y., Zhou, Z.J., Wang, S.Y., Xiao, J., Zhou, Y.Y., 2017. Community composition specificity and potential role of phosphorus solubilizing bacteria attached on the different bloom-forming cyanobacteria. Microbiol. Res. 205, 59–65

Liu, B.L., Eltanahy, E.E., Liu, H.W., Chua, E.T., Thomas-Hall, S.R., Wass, T.J., Schenk, P. M., 2020. Growth-promoting bacteria double eicosapentaenoic acid yield in microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 316, 123916

Matos, J., Cardoso, C., Bandarra, N.M., Afonso, C., 2017. Microalgae as healthy ingredients for functional food: a review. Food Funct. 8, 2672–2685. Matos, J., Cardoso, C., Gomes, A., Campos, A.M., Fale, P., Afonsoa, C., Bandarraa, N.M., 2019. Bioprospection of Isochrysis galbana and its potential as a nutraceutical. Food Funct. 10, 7333–7342

Okuyama, H., Morita, N., Kogame, K., 1992. Occurrence of octadecapentaenoic acid in lipids of a cold stenothermic alga, Prymnesiophyte strain B. J. Phycol. 28, 465–472

Picardo, M.C., de Medeiros, J.L., Araujo, O.D.F., Chaloub, R.M., 2013. Effects of CO2 enrichment and nutrients supply intermittency on batch cultures of Isochrysis galbana Bioresour. Technol. 143, 242–250

Pradhan, B., Nayak, R., Patra, S., Jit, B.P., Ragusa, A., Jena, M., 2021. Bioactive metabolites from marine algae as potent pharmacophores against oxidative stressassociated human diseases: a comprehensive review. Molecules. 26, 37

Romieu, I., Tellez-Rojo, M.M., Lazo, M., Manzano-Patino, A., Cortez-Lugo, M., Julien, P., Holguin, F., 2005. Omega-3 fatty acid prevents heart rate variability reductions associated with particulate matter. Am. J. Resp. Crit. Care. 172, 1534–1540

Sandhya, S.V., Vijayan, K.K., 2019. Symbiotic association among marine microalgae and bacterial flora: a study with special reference to commercially important Isochrysis galbana culture. J. Appl. Phycol. 31, 2259–2266.

Sayegh, F.A.Q., Montagnes, D.J.S., 2011. Temperature shifts induce intraspecific variation in microalgal production and biochemical composition. Bioresour. Technol. 102, 3007–3013

Singer, E., Webb, E.A., Nelson, W.C., Heidelberg, J.F., Ivanova, N., Pati, A., Edwards, K. J., 2011. Genomic potential of Marinobacter aquaeolei, a biogeochemical “opportunitroph” Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 2763–2771

Tremblay, R., Cartier, S., Miner, P., Pernet, F., Quere, C., Moal, J., Samain, J.F., 2007. Effect of Rhodomonas salina addition to a standard hatchery diet during the early ontogeny of the scallop Pecten maximus Aquaculture. 262, 410–418

Vraspir, J.M., Butler, A., 2009. Chemistry of marine ligands and siderophores. Annu. Rev. Mar. Sci. 1, 43–63

Wang, W.J., Li, X.L., Zhu, J.Y., Liang, Z.R., Liu, F.L., Sun, X.T., Shen, Z.G., 2019. Antioxidant response to salinity stress in freshwater and marine Bangia (Bangiales, Rhodophyta). Aquat. Bot. 154, 35–41

Wei, Z.J., Wang, H.N., Li, X., Zhao, Q.Q., Yin, Y.H., Xi, L.J., Qin, S., 2019. Enhanced biomass and lipid production by co-cultivation of Chlorella vulgaris with Mesorhizobium sangaii under nitrogen limitation. J. Appl. Phycol. 32, 233–242

Yaakob, Z., Ali, E., Zainal, A., Mohamad, M., Takriff, M.S., 2014. An overview: biomolecules from microalgae for animal feed and aquaculture. J. Biol. Res. 21, 6

Yang, F., Chen, S., Miao, Z., Sheng, Z., Xu, J., Wan, J., Yan, X., 2016. The effect of several microalgae isolated from East China Sea on growth and survival rate of postset juveniles of razor clam, Sinonovacula constricta (Lamarck, 1818). Aquac. Nutr. 22, 846–856

Zhang, L.T., Li, L., Liu, J.G., 2014. Comparison of the photosynthetic characteristics of two Isochrysis galbana strains under high light. Bot. Mar. 57, 477–481.

Other documents randomly have different content

of a redder countenance. His manner was as cordial as before, but his mood was not so jovial.

"I am always worrying about something or other, and just now it is my health," he told Hemming. "You don't know what I'd give, captain, for a life like yours—and a good hard body like yours. But I can't drop this job now. It's the very devil, I can tell you, to have one's brain and nerves jumping and twanging all the time, while one's carcass lolls about and puts on fat. I'm sorry I was so smart when I was a kid. Otherwise the old man would not have sent me to college, and I'd never have hustled myself into this slavery. My father was a lumberman, and so was my grandfather. They had big bodies, just like mine, but they lived the right kind of lives for their bodies."

Hemming felt sorry for him. He saw that the gigantic body was at strife with the manner of life to which it was held, and that the same physique that had proved itself a blessing to the lumberman, was a menace to the desk-worker.

"Better take a few months in the woods," he suggested.

Dodder laughed bitterly. "You might just as well advise me to take a few months in heaven," he said.

Hemming asked for news of O'Rourke.

The manager's face lighted.

"O'Rourke," he exclaimed, "is a man wise in his generation. Shackles of gold couldn't hold that chap from his birthright of freedom. He did us some fine work for a time,—rode with Gomez and got his news out somehow or other,—but went under with enteric and left Cuba. We kept him on, of course, but as soon as he could move around again he resigned his position. He said he had some very pressing business affair to see to."

"Is he well again?" asked Hemming, anxiously.

"Oh, yes, he's able to travel," replied Dodder. "He was here only a week ago. He seems to be making a tour of the Eastern cities. I guess he's looking

for something."

"An editor, likely, who has lost some of his manuscripts," remarked Hemming.

"Or a girl," said the other.

"Why a girl?" asked the Englishman.

Dodder smiled pensively. "I like to think so," he said, "for though I am nothing but a corpulent business slave myself, I've a fine active brain for romance, and the heart of a Lochinvar."

Hemming nodded gravely. Dodder laughed at him. "You are thinking what a devilish big horse I need," he said.

They dined together that evening at the Reform Club, and Hemming was amazed at the quantity of food the big man consumed. He had seen O'Rourke, the long, lean, and broad, sit up to some hearty meals after a day in the saddle, but never had he met with an appetite like Dodder's. It was the appetite of his ancestral lumbermen, changed a little in taste, perhaps, but the same in vigour.

War was in order between the United States of America and Spain. General Shafter's army was massing in Tampa, Florida, and Hemming, with letters from the syndicate, started for Washington to procure a pass from the War Office. But on the night before his departure from New York came news from London of his book, and the first batch of proof-sheets for correction. He worked until far into the morning, and mailed the proofs, together with a letter, before breakfast. Arriving in Washington, he went immediately to the War Department building, and handed in his letters. The clerk returned and asked him to follow to an inner room. There he found a pale young man, with an imposing, closely printed document in his hand.

"Captain Hemming?" inquired the gentleman.

Hemming bowed.

"Your credentials are correct," continued the official, "and the Secretary of War has signed your passport. Please put your name here."

Hemming signed his name on the margin of the document, folded it, and stowed it in a waterproof pocketbook, and bowed himself out. He was about to close the door behind him when the official called him back.

"You forgot something, captain," said the young man, holding a packet made up of about half a dozen letters toward him.

"Not I," replied Hemming. He glanced at the letters, and read on the top one "Bertram St. Ives O'Rourke, Esq."

"O'Rourke," he exclaimed.

"How stupid of me," cried the young man.

"Where is he? When was he here?" inquired Hemming. "He is a particular friend of mine," he added.

The official considered for a second or two.

"Tall chap with a yellow face and a silk hat, isn't he?" he asked.

"Tall enough," replied Hemming, "but he had neither a yellow face nor a silk hat when I saw him last—that was in Jamaica, about a year ago."

At that moment the door opened and O'Rourke entered. Without noticing Hemming he gave a folded paper to the clerk.

"You'll find that right enough," he said—and then his eye lighted upon his old comrade. He grasped the Englishman by the shoulders and shook him backward and forward, grinning all the while a wide, yellow grin.

"My dear chap," protested Hemming, "where have you been to acquire this demonstrative nature?"

"Lots of places. Come and have a drink," exclaimed O'Rourke.

"I'll mail that to your hotel," called the pale young man after them, as they hurried out.

"What are you up to now, my son?" inquired Hemming, critically surveying the other's faultless attire. "You look no end of a toff, in spite of your yellow face."

"Thanks, and I feel it," replied his friend, "but my release is at hand, for to-night I shall hie me to mine uncle's and there deposit these polite and costly garments. Already my riding-breeches and khaki tunic are airing over the end of my bed."

"But why this grandeur, and this wandering about from town to town?" asked Hemming. He caught the quick look of inquiry on his friend's face. "Dodder told me you'd been aimlessly touring through the Eastern States," he added.

"Here we are—come in and I'll tell you about it," replied O'Rourke. They entered the Army and Navy Club, and O'Rourke, with a very-much-athome air, led the way to a quiet inner room.

"I suppose we'll split the soda the same old way—as we did before sorrow and wisdom came to us," sighed O'Rourke. He gave a familiar order to the attentive waiter. Hemming looked closely at his companion, and decided that the lightness was only a disguise.

"Tell me the yarn, old boy—I know it's of more than fighting and fever," he said, settling himself comfortably in his chair.

O'Rourke waited until the servant had deposited the glasses and retired. Then he selected two cigars from his case with commendable care, and, rolling one across the table, lit the other. He inhaled the first draught lazily.

"These are deuced fine cigars," remarked Hemming. O'Rourke nodded his head, and, with his gaze upon the blue drift of smoke, began his story.

"I was in a very bad way when I got out of that infernal island last time. I had a dose of fever that quite eclipsed any of my former experiences in

that line—also a bullet-hole in the calf of my left leg. Maybe you noticed my limp, and thought I was feigning gout. A tug brought me back to this country, landing me at Port Tampa. Some patriotic Cubans were waiting for me, and I made the run up to Tampa in a car decorated with flags. I wore my Cuban uniform, you know, and must have looked more heroic than I felt."

Hemming raised his eyebrows at that.

"I'm a major in the Cuban army—the devil take it," explained O'Rourke.

"The patriots escorted me to a hotel," he continued, "but the manager looked at my banana-hued face and refused to have anything to do with me at any price. Failing in this, my tumultuous friends rushed me to a wooden hospital, at the end of a river of brown sand which the inhabitants of that town call an avenue. I was put to bed in the best room in the place, and then my friends hurried away, each one to find his own doctor to offer me. I was glad of the quiet, for I felt about as beastly as a man can feel without flickering out entirely. I don't think my insides just then would have been worth more than two cents to any one but a medical student. The matron— at least that's what they called her—came in to have a look at me, and ask me questions. She was young, and she was pretty, and her impersonal manner grieved me even then. I might have been a dashed pacifico for all the interest she showed in me, beyond taking my temperature and ordering the fumigation of my clothes. I wouldn't have felt so badly about it if she had not been a lady—but she was, sure enough, and her off-hand treatment very nearly made me forget my cramps and visions of advancing landcrabs. During the next few days I didn't know much of anything. When my head felt a little clearer, the youthful matron brought me a couple of telegrams. I asked her to open them, and read them to me. Evidently my Cuban friends had reported the state of my health, and other things, for both telegrams were tender inquiries after my condition.

"'You seem to be a person of some importance,' she said, regarding me as if I were a specimen in a jar.

"'My name is O'Rourke,' I murmured. For awhile she stared at me in a puzzled sort of way. Suddenly she blushed.

"'I beg your pardon, Mr. O'Rourke,' she said, and sounded as if she meant it. I felt more comfortable, and sucked my ration of milk and limewater with relish. Next day the black orderly told me that the matron was Miss Hudson, from somewhere up North. He didn't know just where. I gave him a verbal order on the hospital for a dollar.

"Presently Miss Hudson came in and greeted me cheerfully. 'Why do you want Harley to have a dollar?' she asked.

"'Just for a tip,' I replied, wearily.

"'He is paid to do his work, and if some patients fee him, the poorer ones will suffer,' she said.

"'But I want him to have it, please. He told me your name,' I said.

"She paid no more attention to this foolish remark than if I had sneezed. Indeed, even less, for if I had sneezed she would have taken my pulse or my temperature. I watched her as she moved about the room seeing that all was clean and in order.

"'Miss Hudson,' I said, gaining courage, 'will you tell me what is going on in the world? Have you a New York paper?'

"'Yes, some papers have come for you,' she answered, 'and I will read to you for a little while, if you feel strong enough to listen. There is a letter, too. Shall I open it for you?'

"She drew a chair between my bed and the window, and, first of all, examined the letter.

"'From the New York News Syndicate,' she said.

"'Then it's only a check,' I sighed.

"'I shall put it away with the money you had when you came,' she said. She opened a paper, glanced at it, and wrinkled her white brow at me.

"'Are you the Bertram St. Ives O'Rourke?" she asked.

"'No, indeed,' I replied. 'He has been dead a long time. He was an admiral in the British navy.'

"'I have never heard of him,' she answered, 'but there is a man with that name who writes charming little stories, and verses, too, I think.'

"'Oh, that duffer,' I exclaimed, faintly.

"She laughed quietly. 'There is an article about him here—at least I suppose it is the same man.' She glanced down the page and then up at me. 'An angel unawares,' she laughed, and chaffed me kindly about my modesty.

"After that we became better friends every day, though she often laughed at the way some of the papers tried to make a hero of me. That hurt me, because really I had gone through some awful messes, and been sniped at a dozen times. The Spaniards had a price on my head. I told her that, but she didn't seem impressed. As soon as I was able to see people, my friends the Cuban cigar manufacturers called upon me, singly and in pairs, each with a gift of cigars. These are out of their offerings. The more they did homage to me, the less seriously did Miss Hudson seem to regard my heroism. But she liked me—yes, we were good friends."

O'Rourke ceased talking and pensively flipped the ash off his cigar. Leaning back in his chair, he stared at the ceiling.

"Well?" inquired his friend. O'Rourke returned to the narration of his experience with a visible effort.

"After awhile she read to me, for half an hour or so, every day. One evening she read a ballad of my own; by gad, it was fine. But then, even the Journal sounded like poetry when she got hold of it. From that we got to talking about ourselves to each other, and she told me that she had learned nursing, after her freshman year at Vassar, because of a change in her father's affairs. She had come South with a wealthy patient, and, after his recovery, had accepted the position of matron, or head nurse, of that little hospital. In return, I yarned away about my boyhood, my more recent adventures, my friends, and my ambitions. At last my doctor said I could

leave the hospital, but must go North right away. My leg was healed, but otherwise I looked and felt a wreck. I was so horribly weak, and my nights continued so crowded with suffering and delirium, that I feared my constitution was ruined. I tried to keep myself in hand when Miss Hudson was around, but she surely guessed that I loved her."

"What's that?" interrupted Hemming.

"I said that I loved her," retorted O'Rourke, defiantly.

"Go ahead with the story," said the Englishman.

"When the time came for my departure," continued O'Rourke, "and the carriage was waiting at the curb, I just kissed her hand and left without saying a word. I came North and got doctors to examine me. They said that my heart and lungs were right as could be, and that the rest of my gear would straighten up in time. They promised even a return of my complexion with the departure of the malaria from my blood. But I must live a quiet life for awhile, they said; so to begin the quiet life I returned to Tampa, and that hospital. But I did not find the girl."

"Was she hiding?" inquired Hemming. "Perhaps she had heard some stories to your discredit."

"No," said O'Rourke, "she had resigned, and left the town, with her father. Evidently her troubles were ended—just as mine were begun."

"What did you do about it?" asked Hemming, whose interest was thoroughly aroused.

"Oh, I looked for her everywhere—in Boston, and New York, and Baltimore, and Washington, and read all the city directories," replied the disconsolate lover, "but I do not know her father's first name, and you have no idea what a lot of Hudsons there are in the world."

Hemming discarded the butt of his cigar, and eyed his friend contemplatively.

"I suppose you looked in the registers of the Tampa hotels?" he queried. "The old chap's name and perhaps his address would be there."

O'Rourke started from his chair, with dismay and shame written on his face.

"Sit down and have another," said Hemming; "we'll look it up in a few days."

CHAPTER X. LIEUTENANT ELLIS IS CONCERNED

By the time Hemming and O'Rourke reached Tampa, about thirty thousand men had gone under canvas in the surrounding pine groves and low-lying waste places. There were Westerners and Easterners, regulars and volunteers, and at Port Tampa a regiment of coloured cavalry. Troops were arriving every day. Colonel Wood and Lieutenant-Colonel Roosevelt, with their splendid command of mounted infantry, had just pitched their sheltertents in a place of scrub palmetto, behind the big hotel. Taken altogether, it was an army that made Hemming stare.

The friends went to a quiet hotel with wide verandas, cool rooms, open fireplaces, and what proved equally attractive, reasonable rates. They inquired of the clerk about Mr. Hudson. He remembered the gentleman well, though he had spent only two days in the place. "He had a daughter with him," the man informed them, and, turning to the front of the register, looked up the name. "There's the signature, sir, and you're welcome to it," he said. The correspondents examined it intently for some time.

"We know that that means Hudson," remarked O'Rourke, at last, "and I should guess John for the other sprawl."

"Sprawl is good," said Hemming, straightening his monocle, "but any one can see that Robert is the name."

"I've put a lot of study on it," said the clerk, "and so has the boss, and we've about agreed to call it Harold."

"Take your choice," said O'Rourke, "but tell me what you make of the address."

"Boston," cried the clerk.

They stared at him. "You were all ready," said Hemming.

"Yes, sir," he replied, "for I've been thinking it over for some time."

"Why the devil didn't you ask him?" inquired O'Rourke, fretfully.

"Lookee here, colonel," said the hotel man, "if you know Mr. Hudson, you know darn well why I didn't ask him where he came from."

"High and haughty?" queried O'Rourke.

The clerk nodded.

"You had better reconsider your course, old chap," laughed the Englishman.

His friend did not reply. He was again intent on the register.

"I make seven letters in it," he said, "and I'll swear to that for an N."

"N nothing," remarked the clerk; "that's a B."

"Yes, it is a B, I think, and to me the word looks like—well, like Balloon," said Hemming.

O'Rourke sighed. "Of course it is New York; see the break in the middle, and a man is more likely to come from there than from a balloon," he said.

"Some men go away in balloons, sir," suggested the clerk.

Just then the proprietor of the hotel entered and approached the desk. He Was an imposing figure of a man, tall and deep, and suitably dressed in the roomiest of light tweeds. His face was round and clever. He shook hands with the new arrivals.

"Military men, I believe," he said.

"Not just now," replied Hemming.

"Do you know where Mr. Hudson is at present?" asked O'Rourke, in casual tones.

"Mr. Hudson, of Philadelphia? Why, no, sir, I can't say that I do," answered the big man.

"How do you know he's of Philadelphia?" asked the Englishman.

"He wrote it in the register; look for yourself," was the reply.

"No," said O'Rourke, mournfully, "but it is a very dry evening, and if you will honour us with your company as far as the bar, Mr.—"

"Stillman,—delighted, sir," hastily replied the proprietor.

The three straightway sought that cool retreat, leaving the clerk to brood, with wrinkled brow, above the puzzle so unconsciously donated to him by a respectable one-time guest.

The weary delay in that town of sand and disorder at last came to an end, and Hemming and O'Rourke, with their passports countersigned by General Shafter, went aboard the Olivette. Most of the newspaper men were passengers on the same boat. During the rather slow trip, they made many friends and a few enemies. One of the friends was a youth with a camera, sent to take pictures for the same weekly paper which O'Rourke represented. The landing in Cuba of a part of the invading forces and the correspondents was made at Baiquiri, on the southern coast. The woful mismanagement of this landing has been written about often enough.

O'Rourke and Hemming, unable to procure horses, set off toward Siboney on foot, and on foot they went through to Santiago with the ragged, hungry, wonderful army. They did their work well enough, and were thankful when it was over. Hemming admired the American army—up to a certain grade. Part of the time they had a merry Toronto journalist for messmate, a peaceful family man, who wore a round straw hat and low shoes throughout the campaign. During the marching (but not the fighting), O'Rourke happened upon several members of his old command. One of the meetings took place at midnight, when the Cuban warrior was in the act of carrying away Hemming's field-glasses and the Toronto man's blanket.

After the surrender of Santiago, Hemming received word to cover Porto Rico. He started at the first opportunity in a gunboat that had once been a harbour tug. O'Rourke, who was anxious to continue his still hunt for the lady who had nursed him, returned to Florida, and from thence to New York.

In Porto Rico Hemming had an easy and pleasant time. He struck up an acquaintance that soon warmed to intimacy with a young volunteer lieutenant of infantry, by name Ellis. Ellis was a quiet, well-informed youth; in civil life a gentleman-at-large with a reputation as a golfer. With his command of sixteen men he was stationed just outside of Ponce, and under the improvised canvas awning before his door he and Hemming exchanged views and confidences. One evening, while the red eyes of their green cigars glowed and dimmed in the darkness, Hemming told of his first meeting with O'Rourke. He described the little boat tossing toward them from the vast beyond, the poncho bellied with the wind, and the lean, undismayed adventurer smoking at the tiller. Ellis sat very quiet, staring toward the white tents of his men.

"Is that the same O'Rourke who was once wounded in Cuba, and later nearly died of fever in Tampa?" he asked, when Hemming was through.

"Yes, the same man," said Hemming, "and as decent a chap as ever put foot in stirrup. Do you know him?"

"No, but I have heard a deal about him," replied the lieutenant. It did not surprise Hemming that a man should hear about O'Rourke. Surely the good

old chap had worked hard enough (in his own daring, vagrant way) for his reputation. He brushed a mosquito away from his neck, and smoked on in silence.

"I have heard a—a romance connected with your friend O'Rourke," said Ellis, presently, in a voice that faltered. Hemming pricked up his ears at that.

"So have I. Tell me what you have heard," he said.

"It is not so much what I've heard, as who I heard it from," began the lieutenant, "and it's rather a personal yarn. I met a girl, not long ago, and we seemed to take to each other from the start. I saw her frequently, and I got broken up on her. Then I found out that, though she liked me better than any other fellow in sight, she did not love me one little bit. She admired my form at golf, and considered my conversation edifying, but when it came to love, why, there was some one else. Then she told me about O'Rourke. She had nursed him in Tampa for several months, just before the time old Hudson had recaptured his fortune."

"O'Rourke told me something about it," said Hemming. "He thought, at the time, that he was an invalid for life, so he did not let her know how he felt about her. Afterward the doctors told him he was sound as a bell, and ever since—barring this last Cuban business—he has been looking for her."

"But he does not know that she loves him?" queried Ellis.

"I really couldn't say," replied Hemming.

Ellis shifted his position, and with deft fingers rerolled the leaf of his moist cigar. In a dim sort of way he wondered if he could give up the girl. In time, perhaps, she would love him—if he could keep O'Rourke out of sight. A man in the little encampment began to sing a sentimental negro melody. The clear, sympathetic tenor rang, like a bugle-call, across the stagnant air. A banjo, with its wilful pathos, tinkled and strummed.

"Listen! that is Bolls, my sergeant. He is a member of the Harvard Glee Club," said the lieutenant.

Hemming listened, and the sweet voice awoke the bitter memories. Presently he asked: "What is Miss Hudson's address?"

"She is now in Europe, with her father," replied his companion. "Their home is in Marlow, New York State."

"May I let O'Rourke know?" asked Hemming.

"Certainly," replied Ellis, scarce above a whisper. He wondered what nasty, unsuspected devil had sprung to power within him, keeping him from telling that the home in Marlow was by this time in the hands of strangers, and that the Hudsons intended living in New York after their return from Europe.

O'Rourke had asked Hemming to write to him now and then, to the Army and Navy Club at Washington, where the letters would be sure to find him sooner or later; so Hemming wrote him the glad information from Porto Rico.

CHAPTER XI.

HEMMING DRAWS HIS BACK PAY

Hemming walked down Broadway on the morning of a bright November day. The hurrying crowds on the pavements, however weary at heart, looked glad and eager in the sunlight. The stir of the wide street got into his blood, and he stepped along with the air of one bound upon an errand that promised more than money. He entered a cigar store, and filled his case with Turkish cigarettes. Some newspapers lay on the counter, but he turned away from them, for he was sick of news. Further along, he glanced into the windows of a book-shop. His gaze alighted upon the figure of a Turkish soldier. Across the width of the sheet ran the magic words,

"Where Might Is Right. A Book of the Greco-Turkish War. By Herbert Hemming."

As one walks in a dream, Hemming entered the shop. "Give me a copy of that book," he said.

"I beg your pardon, sir?" inquired the shopman.

Hemming recovered his wits.

"I want a copy of 'Where Might Is Right,' by Hemming," he said. He laid aside his gloves and stick, and opened the book with loving hands. His first book. The pride of it must have been very apparent on his tanned face, for the man behind the counter smiled.

"I have read that book myself," ventured the man. "I always read a book that I sell more than twenty copies of in one day."

Hemming glowed, and continued his scrutiny of the volume. On one of the first pages was printed, "Authorized American Edition." The name of the publishers was S——'s Sons.

"Where do S——'s Sons hang out?" he asked, as he paid for the book.

"Just five doors below this," said the man.

"I'll look in there," decided Hemming, "before I call on Dodder."

The war correspondent was cordially received by the head of the great publishing house. He was given a comprehensive account of the arrangements made between his London and New York publishers, and these proved decidedly satisfactory. The business talk over, Hemming prepared to go.

"I hope you will look me up again before you leave town," said the head of the firm, as they shook hands.

Arrived in the outer office of the New York News Syndicate, Hemming inquired for Mr. Dodder. The clerk stared at him with so strange an

expression that his temper suffered.

"Well, what the devil is the matter?" he exclaimed.

"Mr. Dodder is dead," replied the youth. Just then Wells came from an inner room, caught sight of the Englishman, and approached.

"So you're back, are you?" he remarked, with his hands in his pockets. Hemming was thinking of the big, kind-hearted manager, and replied by asking the cause of his death. "Apoplexy. Are you ready to sail for the Philippines? Why didn't you wait in Porto Rico for orders?" he snapped.

"Keep cool, my boy," said Hemming's brain to Hemming's heart. Hemming himself said, with painful politeness: "I can be ready in two days, Mr. Wells, but first we must make some new arrangements as to expenses and salary."

"Do you think you are worth more than you get?" sneered Wells. "Has that book that you wrote, when we were paying you to do work for us, given you a swelled head?"

Hemming was about to reply when an overgrown young man, a bookkeeper, who had been listening, nudged his elbow roughly.

"Here's your mail," he said.

Hemming placed the half-dozen letters in his pocket. His face was quite pale, considering the length of time he had been in the tropics. He took the overgrown youth by the front of his jacket and shook him. Then he twirled him deftly and pushed him sprawling against his enraged employer. Both went down, swearing viciously. The other inmates of the great room stared and waited. Most of them looked pleased. An office boy, who had received notice to leave that morning, sprang upon a table. "Soak it to 'em, Dook. Soak it to 'em, you bang-up Chawley. Dey can't stand dat sort o' health food."

Wells got to his feet. The bookkeeper scrambled up and rushed at Hemming. He was received in a grip that made him repent his action.

"Mr. Wells," said Hemming, "I shall hold on to this gentleman, who does not seem to know how to treat his superiors, until he cools off, and in the meantime I'll trouble you for what money is due me, up to date. Please accept my resignation at the same time."

"I'll call a copper," sputtered Wells.

The door opened, and the head of the publishing house of S——'s Sons entered.

"Good Lord, what is the trouble?" he cried.

"I am trying to draw my pay," explained Hemming.

The new arrival looked at the ruffled, confused Wells with eyes of contempt and suspicion.

"I'll wait for you, Mr. Hemming, on condition that you will lunch with me," he cried.

A few minutes later they left the building, and in his pocket Hemming carried a check for the sum of his back pay.

"In a month from now," said his companion, "that concern will not be worth as much as your check is written for. Even poor old Dodder had all he could do to hold it together. He had the brains and decency, and that fellow had the money."

By the time lunch was over, Hemming found himself once more in harness, but harness of so easy a fit that not a buckle galled. The billet was a roving commission from S——'s Sons to do articles of unusual people and unusual places for their illustrated weekly magazine. He spent the afternoon in reading and writing letters. He advised every one with whom he had dealings of his new headquarters. He had a good collection of maps, and sat up until three in the morning pondering over them. Next day he bought himself a camera, and overhauled his outfit. By the dawn of the third day after his separation from the syndicate, he had decided to start northward, despite the season.

The clamour of battle was no longer his guide. Now the Quest of the Little-Known was his. It brought him close to many hearths, and taught him the hearts of all sorts and conditions of men. In the span of a few years, it made him familiar with a hundred villages between Nain in the North and Rio de Janeiro in the South. He found comfort under the white lights of strange cities, and sought peace in various wildernesses. Under the canvas roof and the bark, as under the far-shining shelters of the town, came ever the dream of his old life for bedfellow.

END OF PART I.