Introduction

Nam quis nescit, primam esse prima est historiae legem, ne quid falsi dicere audeat? Deinde ne quid veri non audeat? Ne qua suspicio gratiae sit in scribendo? Ne quae simultatis?

For who does not know history’s first law to be that an author must not dare to tell anything but the truth? And its second that he must make bold to tell the whole truth? That there must be no suggestion of partiality anywhere in his writings? Nor of malice?1

Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Oratore [On the Orator], 55 bc

Forgetting, I would even say historical error, is an essential factor in the creation of a nation and it is for this reason that the progress of historical studies often poses a threat to nationality. Historical inquiry, in effect, throws light on the violent acts that have taken place at the origin of every political formation, even those that have been the most benevolent in their consequences. Unity is always brutally established.2

Ernest Renan, French philosopher and historian, in a lecture delivered at Sorbonne University titled “What is a Nation?,” March 11, 1882

Słynny z mordów i grabieży

Known for murder and for looting

Dziewiętnasty pułk młodzieży. The Nineteenth is now recruiting. Lance do boju, szable w dłoń, Grab your lance and sabre quick, bolszewika goń, goń, goń! Chase, chase, chase the Bolshevik!

Dziewiętnasty tym się chwali: The whole regiment feels pride Na postojach wioski pali. When it’s torched the countryside. Gwałci panny, gwałci wdowy Raping to its heart’s content, Dziewiętnasty pułk morowy. Is the Nineteenth Regiment.

Same łotry i wisielce Gallows-birds and villains, then, To są Jaworskiego strzelce. Join Jaworski’s riflemen. Bić, mordować—nic nowego Maiming, killing—nothing new Dla ułanów Jaworskiego. For Jaworski’s mounted crew.

1 Quote and translation from Marcus Tullius Cicero, De Oratore: In Two Volumes, edited by Harris Rackham, with translations by Edward William Sutton (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1957), 242–5.

2 Ernest Renan, Qu’est-ce qu’une nation?: Conférence faite en Sorbonne, le 11 mars 1882 (Paris: Calmann Lévy, 1882), 7–8. Translation from Ethan Rundell, https://www.academia.edu/33769892/ What_is_a_Nation, accessed May 1, 2018.

Civil War in Central Europe, 1918–1921

Wroga gnębić, wódkę pić, Fighting foes and drinking sprees, Jaworczykiem trzeba być. That’s Jaworski’s cavalry.3

Popular contemporary song on the soldiers serving the Second Polish Republic under the command of Feliks Jaworski during the Polish–Ukrainian conflict 1918–19 and the Polish–Soviet War 1919–20

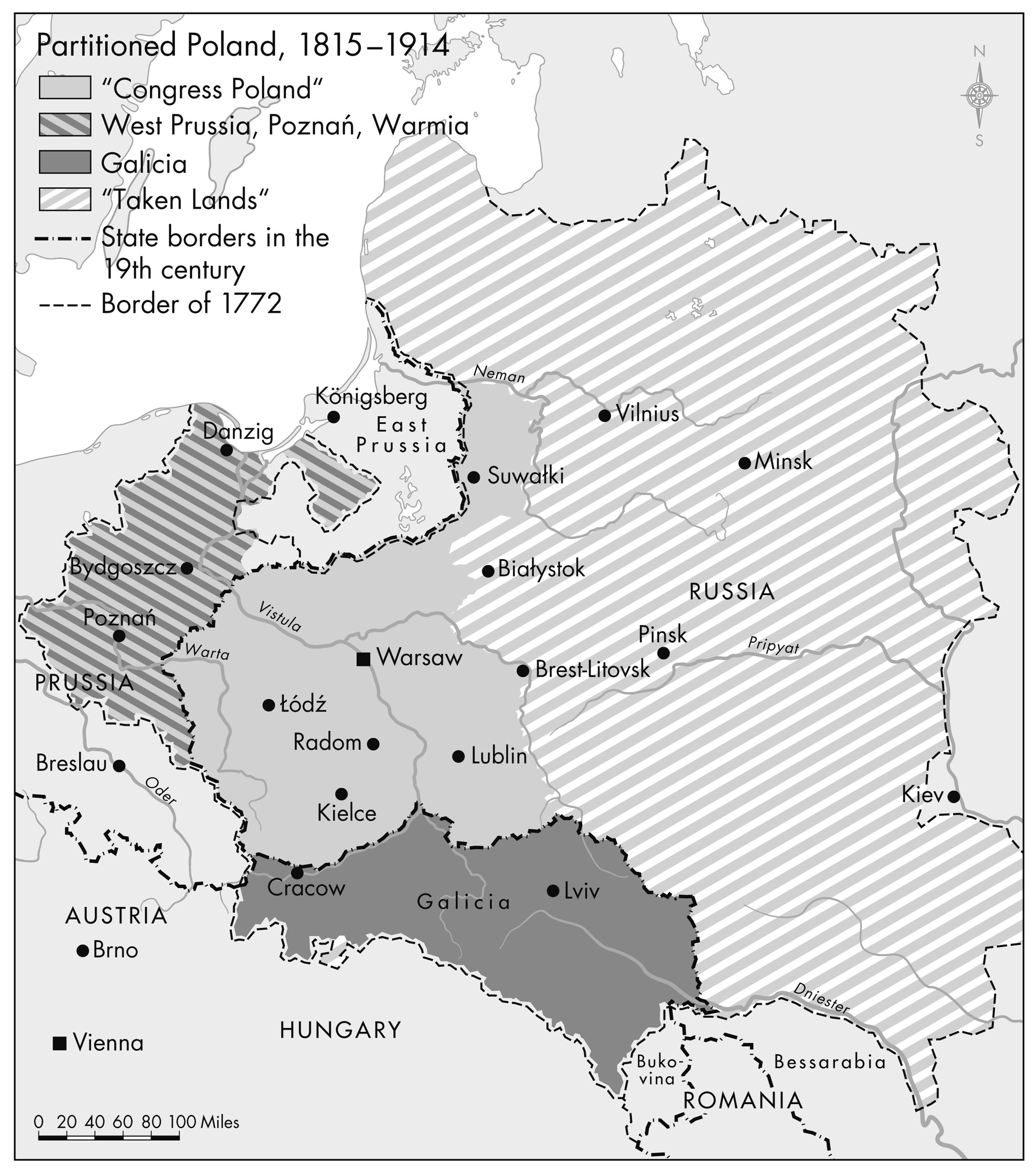

In 1919, the year following the Polish declaration of independence, the famous writer Maria Dąbrowska asked her audience an emotive question: “Where is Poland?” By that time, this was all but a rhetorical question, and it has continued to puzzle generations of students of Central and Eastern European history ever since. Recently Włodzimierz Borodziej has added a follow-up to this conundrum: “What is Poland?”4 Both questions, pointing at a period when the country’s geographical and political shape was in flux, seem highly appropriate. Poland, a state that had been erased from the European map more than one hundred years earlier, would only reappear at the very end of the First World War, and consolidate its geographical and political shape in its after-battles of 1918–21. Our study is concerned with this process of reconstructing and forging the Polish nation and state in the fires of war and civil war. And in this context, a third question imposes itself: “What is a Pole?” This question will occupy the reader throughout this volume. To build a state necessitates defining not only its shape and constitution, but also its population. Being a Pole meant something completely different at the turn of the nineteenth than in the twentieth century. As the censuses conducted around 1900 in Central Europe vividly demonstrate, people living in one of the three parts of former Poland then occupied by foreign powers had as much of a problem defining their “nationality” as had their respective governments. Was a Pole a person speaking Polish, in contrast to a person speaking Ukrainian, Latvian, German, Czech, or Yiddish, or was a Pole a Roman Catholic, in contrast to a Greek Catholic, a Protestant or Orthodox Christian, or a Jew? Was a Pole someone belonging to a certain class, such as a wealthy landlord in the eastern parts of the former Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, in contrast to the “Ukrainian” peasant working for him? Was being Polish a political statement, making it impossible to be a Bolshevik at the same time? Or was a Pole just someone born into a Polish cultural environment and identifying with the goal of re-erecting a Polish nation state, regardless of language, religion, profession, social status, or politics? Conscious of the shortcomings of this approach, but unable to find a more convincing one, in the following the term “ethnic” will illustrate rather than solve the problem. When applied (far from consistently, to preserve a certain level of readability) to “Poles,” “Jews,” “Ukrainians,” “Lithuanians,” etc., it means people who regarded themselves—or were regarded by contemporaries—as such, characterized by a specific compound of cultural, linguistic, and religious features

3 After numerous transformations, in late 1920 the unit secured the Polish–Soviet demarcation line as ‘Nineteenth Volhynian Cavalry Regiment’ (19 Pułk Ułanów Wołyńskich). Piotr Zychowicz, Sowieci (Poznań: Rebis, 2016), 253, published the song for the first time, apparently as an illustration of the unit’s unconditional devotion for the Polish state and without any sign of unease. The brilliant translation is authored by Artur Zapalowski and Mark Bence.

4 Włodzimierz Borodziej, Geschichte Polens im 20. Jahrhundert (Munich: Beck, 2010), 13–15.

and traditions which eludes precise distinction. Although this definition regards ancestry as a constitutive element of ethnicity, it rejects the Darwinist notion of biological determination.

THE FLAWED POPULAR NARRATIVE

Such reflections are of crucial importance for this book, which deals with the erection of an independent Polish nation state after its absence from the European map that had lasted more than a century. It seems that the history of this important moment in European history has been told already countless times. But taking a closer look at the most relevant publications on this topic, one cannot help feeling a certain disappointment. Too many questions have been either left open so far, or, if answers on certain aspects have been given, they have often not been woven into the fabric of the overall story of the reconstruction of the Polish state which dominates the public discourse until today.

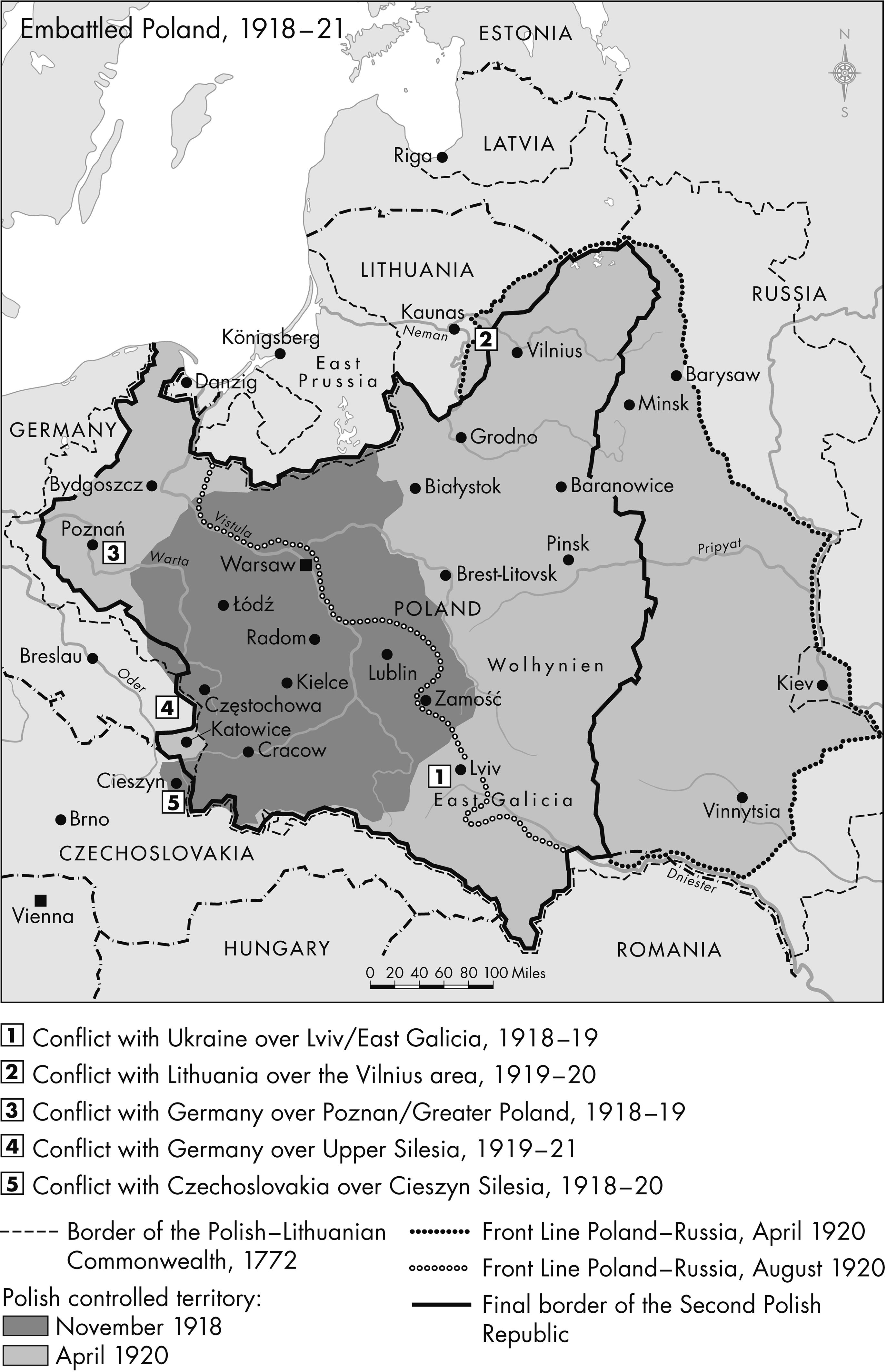

A century after Józef Piłsudski, Poland’s legendary political leader and military commander, arrived at the Warsaw train station to take over state business in November 1918, this story still rather reads like a mythological than a historical narrative which withstands critical analysis: After the three European land empires Prussia, Russia, and Austria had dismantled the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth at the end of the eighteenth century, the Polish nation, united in spirit and unbowed, had contested the brutal tsarist reign in the Russian partition zone in several failed and brutally suppressed uprisings. In the second half of the nineteenth century, two historical figures rose who further propelled the project of a future Polish nation state: Roman Dmowski, who set his ideological foundations from the political right; and Józef Piłsudski, who propagated armed action against its opponents from the political left. When the First World War broke out, Piłsudski led his famous Polish Legions into battle, thus forming the nucleus of a Polish Army whose military audacity assured that Poland would have a say in the reorganization of the European map after the war. In the meantime, Dmowski had emigrated to France and secured a place for Poland at the international conference table through negotiations. But from the first days of independence, the Second Polish Republic had to fight against its hostile neighbors: the Ukrainians, the Lithuanians, the Germans, the Czechs, and the Russians, the latter just having replaced their tsarist regime with a Soviet one, but nevertheless longing to reconquer Poland. The Polish nation, finally reunited, stood together as one, fighting all enemies on all borders, and at the end—although it sometimes seemed a virtual impossibility—emerged victorious from these battles.

To be clear, there is more than a grain of truth in all of this, but it is only part of the story, and it is full of distortions and contradictions. Many of these have already been pointed out by prominent historians.5 The black and white image of imperial suppression and national heroic struggle in the three partition zones, for

5 The following overview is far from comprehensive. More literature is to be found in the respective chapters of this book.

Civil War in Central Europe, 1918–1921

example, has lately been convincingly colorized. Although without a doubt the Polish-speaking parts of the respective population were largely treated as secondclass citizens and submitted to programs of denationalization, the contact between the ruling elites and the ruled masses can be described as a process of negotiation and the balancing of imperial versus national aspirations—with the notable exception of the short periods of armed uprising and brutal reaction by tsarist troops.6 By no longer limiting the role of the Polish population of partition times to that of a nation of tragic heroes and martyrs, such works attest to a certain agency and room to maneuver under imperial rule which for a long time had been widely neglected or ignored in historiography.

When it comes to the Polish agents of national struggle, they were far from acting in concert. Sometimes they were more at odds with each other than with the respective imperial regime whose rule they challenged. In the wake of the 1905 Revolution in the Russian realm of power, armed bands of the Polish Socialist and the National Democratic parties killed each other in street fights in their hundreds. The major underlying disagreement was that the left aimed at an armed overthrow of the old order, while the right regarded this as a hazardous game, and instead favored the politics of, in the parlance of the time, “organic change.”7

Therefore, it was Piłsudski, not Dmowski, who had managed to organize a substantive shadow army of paramilitary fighters in eastern Galicia (within the Austrian partition zone) on the eve of the First World War. But these famous “Legions” failed to mobilize the Polish-speaking masses. Over the course of the war, they remained a numerically negligible force which, although earning fame in battle, had no substantial influence on its outcome. Furthermore, they were allied with the Central Powers (Germany and Austria), which, following their occupation of Russian Poland and the Baltic coast in 1915, were increasingly detested by the local population.8 Separate Polish legionnaire units, similar to Piłsudski’s Legions, although less popular, rarely described, and therefore almost forgotten

6 For the German Empire see Hans-Erich Volkmann, Die Polenpolitik des Kaiserreichs: Prolog zum Zeitalter der Weltkriege (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2016); for the Habsburg Empire see Pieter M. Judson, The Habsburg Empire: A New History (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016); for the Russian Empire see Malte Rolf, Imperiale Herrschaft im Weichselland: Das Königreich Polen im russischen Imperium (1864–1915) (Munich: Oldenbourg, 2015); Malte Rolf, “Between State Building and Local Cooperation: Russian Rule in the Kingdom of Poland, 1864–1915,” Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History 19, no. 2 (2018): 385–416.

7 Ignacy Pawłowski, Geneza i działalność organizacji spiskowo–bojowej PPS, 1904–1905 (Wrocław: Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich, 1976); Waldemar Potkański, Odrodzenie czynu niepodległościowego przez PPS w okresie rewolucji 1905 roku (Warsaw: DiG, 2008); Stefan Garsztecki, “Dmowski und Piłsudski: Nationale Idee zwischen Föderationsgedanke und nationaler Verengung,” in Deutsche und Polen im und nach dem Ersten Weltkrieg, edited by Steffen Menzel and Martin Munke (Chemnitz: Universitätsverlag, 2013), 9–27. For the two options which split the Polish political activists of the time—resistance or acceptance—see Mieczysław B. Biskupski, Independence Day: Myth, Symbol, and the Creation of Modern Poland (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012), 1, referring to Tomasz Nałecz, Irredenta polska: Myśl powstańcza przed I wojna światowa (Warsaw: Uniwersytet Warszawski, 1987), 1–10.

8 Arkadiusz Stempin, Próba “moralnego podboju” Polski przez Cesarstwo Niemieckie w latach I wojny światowej (Warsaw: Neriton, 2013); Jesse Kauffman, Elusive Alliance: The German Occupation of Poland in World War I (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015).

today, were also built within the Russian Army from the outset of the war onwards.9 But in reality, the overwhelming majority of Polish-speaking soldiers who fought in the Great War were simply cannon fodder in the ranks of one of the three partitioning powers’ armies rather than a formation with a national agenda.10

When out of this whole motley crew a Polish Army had to be built in 1918, it not only lacked armament, munition, uniforms, and a common language of command, but also discipline and an overarching spirit of comradeship. In fact, many of these soldiers had stood on opposing sides of the trenches shooting at each other only a couple of months before. The political divide between their respective military idols—Józef Piłsudski on the side of the first left-wing government in Warsaw, Józef Haller and Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki on the side of the National Democratic opposition in Paris and the Polish–German borderlands—heightened these animosities.

There is also, to a certain degree, reason to question Piłsudski’s role as a spotless hero of Polish independence which he doubtlessly still plays in our day. In his youth, he had been a terrorist and train robber. He used the socialist party as a vehicle to come to power and abandoned it as soon as his military success and his charisma made it superfluous. Whereas the resurrection of a Polish state was without a shadow of a doubt the driving force behind all his actions before and after 1918, it was not at all set in his mind that it had to be a democratic nation state. Although he endorsed a rather open concept of the Polish nation which encompassed its large minorities, the alleged unselfishness of his federal concept which foresaw a political union with Lithuanians, Belarusians, and Ukrainians does not bear close examination. In reality, like many Polish politicians of his time, Piłsudski took a future Polish hegemony in Central Europe for granted, and any offers of cooperation with other nations were only valid as long as they did not antagonize the country’s rather imperialistic ambitions.11 “I want to be neither a federalist nor an imperialist,” he wrote to a friend in 1919, “until I can talk about these matters

9 Henryk Bagiński, Wojsko polskie na wschodzie 1914–1920 (Warsaw: Główna Księgarnia Wojskowa, 1921); Waldemar Bednarski, “Legion Puławski,” Wojskowy Przegląd Historyczny 33, no. 3 (1988): 100–24; Kazimierz Krajewski, “Nie tylko Dowborczycy,” in Niepodległość, edited by Marek Gałęzowski and Jan M. Ruman (Warsaw: Instytut Pamieci Narodowej, 2010), 195–209.

10 Ryszard Kaczmarek, Polacy w armii kajzera na frontach pierwszej wojny światowej (Cracow: Wydawnictwo Literackie, 2014); Alexander Watson, “Fighting for Another Fatherland: The Polish Minority in the German Army, 1914–1918,” English Historical Review 126, no. 522 (2011): 1137–66. A study of the Poles who served in the ranks of the tsarist army—and not in special Polish units—is still a desideratum. For the postwar fate of Polish veterans from the imperial armies see Marcin Jarząbek, “The Victors of a War that Was Not Theirs: First-World-War-Veterans in the Second Republic of Poland and Their European Peers,” Acta Poloniae Historica 111 (2015): 83–105.

11 Benjamin Conrad, “Vom Ende der Föderation: Die Ostpolitik Piłsudskis und des BelwederLagers 1918–1920,” in Kommunikation über Grenzen Polen als Schauplatz transnationaler Akteure von den Teilungen bis heute, edited by Lisa Bicknell, Benjamin Conrad, and Hans-Christian Petersen (Münster: Lit, 2013), 11–31. Since the Belarusian case did not include an armed engagement with Poland, it is not dealt with in this book. As a small compensation—rather hinting at the complexity of the problem than exploring it—the reader is referred to Andrej Czarniakiewicz and Aleksander Paszkiewicz, “Kwestia białoruska w planach Oddziału II Sztabu Generalnego Wojska Polskiego w latach 1919–1923,” Przegląd Historyczno–Wojskowy 12, no. 3 (2011): 43–56; Janusz Odziemkowski, “Organizacja i ochrona zaplecza Wojsk Polskich na Litwie i Białorusi (luty 1919–lipiec 1920),” Przegląd Historyczno–Wojskowy 14, no. 4 (2013): 25–44; Joanna Gierowska-Kałłaur, “Straż

Civil War in Central Europe, 1918–1921

somewhat seriously—with a gun in my pocket.”12 In 1926, when the quarrels of parliamentary democracy had tired him out, Piłśudski launched a coup d’état and until his death led the country for almost a decade with authoritarian style. Nevertheless, the Piłsudski myth, which was already emerging in 1918, is still so much at work today that Polish historians rarely have challenged it.13

Roman Dmowski for his part is with great justice commonly described as antiSemite—a verdict which he would most probably have readily assigned himself.14 However, this should not make us blind to the strong influence he had on the political fate of the young Polish republic, even beyond its difficult relations with the Jewish minority. Often concealed in the shadow of Piłsudski or reduced to his role as head of the Polish National Committee in Paris from 1917 onwards, his agency in Polish domestic affairs as the leader of the right-wing counterweight to the “Belweder-camp” (named after Piłsudski’s residence as Chief of State near Warsaw’s Łazienki Park) can hardly be overlooked.15 That his embittered feud and rivalry with Piłsudski almost led to a domestic civil war in late 1918 is a historical fact which, although sometimes cursorily mentioned, has been almost ignored so far in historiography.16

It was not only the political leadership of Poland that lacked unity when the Polish Republic was restored. Contradicting public perception, there is a consensus in the academic community that a Polish nation, clearly defined and encompassing, did not exist prior to independence. Even after 1918, the rural masses of the Second Polish Republic had not been won over by the prophets of national unity. An estimated 80 percent of the Polish-speaking population did not identify with the project of the Polish national state during the first years of its fragile existence.17 As a result, the Second Polish Republic lacked the backing

Kresowa wobec kwestii białoruskiej: Deklaracje i praktyka,” Studia z Dziejów Rosji i Europy ŚrodkowoWschodniej 44 (2009): 21–63.

12 Paul Brykczynski, “A Poland for the Poles?: Józef Piłsudski and the Ambiguities of Polish Nationalism,” Pravo: The North American Journal for Central European Studies 1, no. 1 (2007): 2–21, quote: 15.

13 Heidi Hein, Der Piłsudski-Kult und seine Bedeutung für den polnischen Staat 1926–1935 (Marburg: Herder-Institut, 2002); Biskupski, Independence Day. A recent example of unreflecting hero worship, though apart from that well informed, is Peter Hetherington, Unvanquished: Joseph Pilsudski, Resurrected Poland, and the Struggle for Eastern Europe (Houston, TX: Pingora Press, 2012). A notable exeption is Kazimierz Badziak, W oczekiwaniu na przełom: Na drodze od odrodzenia do załamania państwa polskiego, listopad 1918–czerwiec 1920 (Łódź: Ibidem, 2004). The polemic of Rafał A. Ziemkiewicz, Złowrogi cień marszałka (Lublin: Fabryka Słów, 2017), asks thought-provoking questions, but is an extended essay and not an academic treatise on the topic.

14 Grzegorz Krzywiec, Chauvinism, Polish Style: The Case of Roman Dmowski (Beginnings: 1886–1905) (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2016); Andreas Kossert, “Founding Father of Modern Poland and Nationalistic Antisemite: Roman Dmowski,” in In the Shadow of Hitler: Personalities of the Right in Central and Eastern Europe, edited by Rebecca Haynes and Martyn C. Rady (London, New York: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 89–105.

15 Krzysztof Kawalec, Roman Dmowski (Poznań: Zysk i S-ka, 2016).

16 More on the skirmishes between the Polish left and right between the wars most recently in Wolfgang Templin, Der Kampf um Polen: Die abenteuerliche Geschichte der Zweiten Polnischen Republik 1918–1939 (Paderborn: Schöningh, 2018).

17 Jan Molenda, Chłopi, naród, niepodległość: Kształtowanie się postaw narodowych i obywatelskich chłopów w Galicji i Królestwie Polskim w przededniu odrodzenia Polski (Warsaw: Neriton, 1999).

of large parts of its population and therefore faced a severe shortage of recruits when, in the summer of 1920, the Polish–Soviet War brought Poland to the brink of disaster.18

This lack of unity also applies to the relations with its neighbors in the first thousand days of regained independence, when, immediately after the armistices of the Great War, the Poles met the other heirs of the European land empires in armed battle. This clash of arms lasted almost as long as the conventional war itself. Why is it then that we know so little about it? It is stunning that almost a century after the events one looks in vain for a comprehensive history of the conflicting Central European nation states in the years between 1918 and 1921. True enough, a plethora of monographs and articles in Eastern European (and a handful in Western) languages has already dealt with the entangled history of the Second Republic of Poland and its neighbor states in that period, but most surprisingly, none of them tells the whole story.

First of all, the examples where authors tackled the encompassing geographical and chronological setting of this struggle are few and far between.19 In the interwar period, case studies of Polish military formations, organizations, and deployments prevailed, mainly produced by the Office of Military History (Wojskowe Biuro Historyczne), often written by veterans themselves, enriched by memoirs, and therefore only presenting a limited view on the overall course of events. Although not totally undisputed, they laid the foundation for a narrative predominantly told from the perspective of Piłsudski’s former legionnaires. In the Polish People’s Republic after 1945, works on the war between Poland and Soviet Russia were, of course, highly ideologically biased, and the same goes for its battles with other neighbors.20

Soon after the system change in 1989, within the former conflicting states, books on the frontier battles of 1918–21 mushroomed in Poland. It is not surprising that roughly half a century after the country had lost its hard-won independence in the turmoil of the Second World War and the ensuing Soviet reign, some authors tended to glorify the wars of independence after the Great War. In hindsight, these battles were often, rather unreflectingly, seen exclusively as times of national bravado and the overcoming of imperial patronization.21 Apart from

18 Janusz Szczepański, Społeczeństwo Polski w walce z najazdem bolszewickim 1920 roku (Warsaw: Naczelna Dyrekcja Archiwów Państwowych, 2000).

19 Adam Przybylski, La Pologne en lutte pour ses frontières 1918–1920 (Paris: Gebethner & Wolff, 1929); Mieczysław Wrzosek, Wojny o granice Polski Odrodzonej, 1918–1921 (Warsaw: Wiedza Powszechna, 1992).

20 For a concise overview on literature on and sources of the Polish military engagements 1914–21 published up to 1989 see Przemysław Olstowski, “O potrzebach badań nad dziejami walk o niepodległość i granice Rzeczypospolitej (1914–1921),” in Z dziejów walk o niepodległość, edited by Marek Gałęzowski (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2015), 90–107, here: 93–7.

21 See, for example, Mieczysław Pruszyński, Wojna 1920: Dramat Piłsudskiego (Warsaw: BGW, 1994); Piotr Łossowski, Jak Feniks z popiołów: Oswobodzenie ziem polskich spod okupacji w listopadzie 1918 roku (Łowicz: Mazowiecka Wyższa Szkoła Humanistyczno-Pedagogiczna, 1998); Adam Zamoyski, The Battle for the Marchlands: A History of the 1920 Polish–Soviet War (New York: Columbia University Press, 1981); Adam Zamoyski, Warsaw 1920: Lenin’s Failed Conquest of Europe (London: HarperPress, 2008).

Civil War in Central Europe, 1918–1921

that, a growing trend to produce high-quality overviews of the Polish–Soviet, Polish–Ukrainian, and Polish–Lithuanian conflict can be noticed lately.22 Other authors paid meticulous attention to specific military units’ missions, composition, armament, and uniforms.23 Given the abundance of secondary literature at our disposal, it is stunning that a broader analysis of the emergence of the Polish nation and state through the fires of all its border conflicts and inner struggles which complies with scientific standards is still a desideratum.

A STORY UNTOLD

Even if one takes all books that have been published so far on the reconstruction of Poland, there is still a huge gap which historians have hesitated to deal with so far. As a younger generation of academics has painstakingly shown and continues to do so, the whole continent did not come to a rest at the end of 1918 but was hit by a wave of paramilitary violence.24 The new obscurity of politics and power relations produced new agents and victims of violence and left ample space for the abuse of force. “Some veterans,” states Peter Gatrell, “believed they had a duty to ‘beat the world into new shapes,’ even if this meant trampling over noncombatants. For this reason, as well as the high stakes created by the virulent ideologies of revolutionary socialism and nationalism, conflict frequently assumed a particularly brutal form, with civilians often numbered among the casualties.”25 Contentiousness after the armistices meant that the strains of civil war were witnessed even in such a distant “western” country as Great Britain, or down to the southeast, in Greece and Turkey.26

22 For example Norman Davies, White Eagle, Red Star: The Polish–Soviet War, 1919–20 (London: Orbis Books, 1983) (first pub. 1973); Michał Klimecki, Polsko–ukraińska wojna o Lwów i Galicję Wschodnią 1918–1919 (Warsaw: Volumen, 2000); Michał Klimecki, Lwów 1918–1919 (Warsaw: Bellona, 2000); Antoni Czubiński, Walka o granice wschodnie polski w latach 1918–1921 (Opole: Instytut Śląski, 1993); Maciej Kozłowski, Między Sanem a Zbruczem: Walki o Lwów i Galicję Wschodnią 1918–1919 (Cracow: Znak, 1990); Szczepański, Społeczeństwo Polski w walce z najazdem bolszewickim; Jerzy Borzęcki, The Soviet–Polish Peace of 1921 and the Creation of Interwar Europe (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2008); Stanisław Buchowski, Konflikt polsko–litewski o Ziemię Sejneńsko-Suwalską w latach 1918–1920 (Sejny: Sejneńskie Towarzystwo Opieki nad Zabytkami, 2009); Lech Wyszczelski, Wojna polsko–rosyjska, 1919–1920, 2 vols (Warsaw: Bellona, 2010); Janusz Odziemkowski, Piechota polska w wojnie z Rosja bolszewicka 1919–1920 (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Kardynała Stefana Wyszyńskiego, 2010); Janusz Odziemkowski, Polskie formacje etapowe na Litwie i Białorusi 1919–1920 (Cracow: Wydawnictwo i Poligrafia Kurii Prowincjonalnej Zakonu Pijarów, 2011).

23 Pars pro toto Bartosz Kruszyński, Poznańczycy w wojnie polsko–bolszewickiej 1919–1921 (Poznań: Rebis, 2010); Jerzy Kirszak, Armia Rezerwowa gen. Sosnkowskiego w roku 1920 (Warsaw: Instytut Pamięci Narodowej, 2013).

24 The various contributions in Robert Gerwarth and John Horne (eds), War in Peace: Paramilitary Violence in Europe after the Great War (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012) and Robert Gerwarth and Erez Manela (eds), Empires at War, 1911–1923 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2014) represent the state of the art and geographical coverage.

25 Peter Gatrell, “War after the War: Conflicts, 1919–1923,” in A Companion to World War I, edited by John Horne (Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010), 558–75, here: 559.

26 Julia Eichenberg, “The Dark Side of Independence: Paramilitary Violence in Ireland and Poland after the First World War,” Contemporary European History 19, no. 3 (2010): 231–48; Uğur Ümit Üngör, “Paramilitary Violence in the Collapsing Ottoman Empire,” in Gerwarth and Horne (eds), War in Peace, 164–83.

Poland, though, is still a blind spot in this regard. With the notable exception of the anti-Jewish excesses by Polish soldiers (we will return to this phenomenon in a while), the very experience of civil war and paramilitary violence during its formative years 1918–21 has not been made the subject of academic studies yet. This experience, though, is crucial if one tries to understand the dynamics of and connections between the inner and outer conflicts the Second Polish Republic had to deal with during the first years of its threatened existence. Poland’s border struggles have hitherto been described firstly as isolated from each other, and secondly rather as conventional wars, fought out respectively between the Polish and another nation state, that of the Ukrainians, the Lithuanians, the Germans, the Czechs and the Slovaks, or with the new global player in the east, Soviet Russia. But, as will be elaborated in more detail in Chapter 3, they constituted a common realm of experience which is far better understood if seen as one encompassing “war of nations,” which we call the Central European Civil War. Of course, it cannot be denied that in all cases, the nascent Polish Republic had to deal with armed forces of another republic—or, in the case of Russia, with the Red Army. But all the military formations involved in these conflicts, without exception and including the Polish ones, were far from being full-grown and organized armies. Rather, they had to be put together from scratch and dealt with enormous problems of supply, discipline, and desertion. Furthermore, next to these armies-in-the-making, paramilitary, warlord, and criminal bands emerged, competing for the control of the areas in which they were active, and harassing the civil population. This is important to realize because, as a result, the wars fought along the borders of the Second Polish Republic featured forms of violence which are far more typical for intrastate than interstate wars. The very fact that the population of the embattled borderlands was ethnically mixed added to a confusing situation where it was sometimes hard to tell friend from enemy, and to draw a clear line between combatants and civilians.

As said, the available literature only cursorily touches questions of the dynamics and experiences of military and paramilitary violence as a side-product of the nationalist struggles for independence, if at all. To what extent the depiction of a “pure” nationalist struggle for independence departs from the soldierly experience in the field is highlighted by published diaries such as Jerzy Konrad Maciejewski’s “Swashbuckler” (Zawadiaka), who bluntly reports on brutal crimes committed by Polish and other troops deployed in the eastern parts of the Second Republic. When his unit broke into Jewish houses after two shots had been fired at night in a Ukrainian village, he noted on December 28, 1918: “What kind of inspection was that? It was more of a formal pogrom and robbery. Is that how one should search a house to find the one who fired? Such a search should be carried out calmly, systematically, during the day, under the watchful supervision of the officers! I remember [the Polish soldiers] bursting into every room, eating all that was edible In the apartment of some lawyer or doctor, they raped his daughter or sister, supposedly with her consent and to her great satisfaction; she allegedly said in ecstasy that it was ‘romantic’ to be violated in such circumstances.”27

27 Jerzy Konrad Maciejewski, Zawadiaka: Dzienniki frontowe 1914–1920 (Warsaw: Ośrodek Karta, 2015), 122.

Civil War in Central Europe, 1918–1921

Only the pogroms in eastern and central Poland in 1918–19—the only form of collective violence of Polish soldiers beyond the battlefields which resulted in the killing of several hundred people—initiated an overproportioned output of articles dealing with this dark chapter in Polish history. But measured by the enormous relevance of the topic, most of them display a striking lack of analytical depth. They limit themselves to referring, often erroneously, to the seemingly well-known facts in order to either brand or whitewash the soldiers who perpetrated a given incident.28 But two more extensive treatises of this highly sensitive topic have just been completed, substantially deepening our understanding of the dynamics of such pogroms and their underlying social, cultural, and ethnic dynamics.29

What most of these publications on violence against the Jewish minority—as well as the above-mentioned relevant literature—ignore is that Polish soldiers often did not respect the physical integrity and property of other civilians either, and sometimes not even that of their comrades. Such cases were not exceptions, but contributed to a mass phenomenon which their superior military officers and local civil authorities never tired of deploring. But books that mention acts of criminality, desertion, insubordination, rape, or terrorism exerted by Polish soldiers or paramilitaries can still be counted on one hand.30 At least we have two extensive case studies on paramilitary and terrorist violence (perpetrated by both sides involved) in Upper and Cieszyn Silesia.31 Extremely insightful also is a detailed study on the Polish military jurisdiction in Lviv during the street fights between Ukrainian and Polish forces in November 1918.32 Those works amply prove that paramilitary violence was not negligible, but omnipresent between 1918 and 1921. It also indicates that the Polish military higher echelons not only knew about it, but in some cases encouraged and supported it, while in many other cases they condemned and prosecuted it. There is an abundance of archival material, allowing for deeper insights into the extent and reality of paramilitary violence and banditry

28 Notable exceptions are Jerzy Tomaszewski, “Pińsk, Saturday 5 April 1919,” in Poles and Jews: Renewing the Dialogue, edited by Antony Polonsky (Oxford: Littman Library of Jewish Civilization, 2004), 227–51; Alexander Victor Prusin, Nationalizing a Borderland: War, Ethnicity, and Anti-Jewish Violence in East Galicia, 1914–1920 (Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 2005); Jerzy Borzęcki, “German Anti-Semitism à la Polonaise: A Report on Poznanian Troops’ Abuse of Belarusian Jews in 1919,” East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 26, no. 4 (2012): 693–707; Eva Reder, “Praktiken der Gewalt: Die Rolle des polnischen Militärs bei Pogromen während des polnisch–sowjetischen Krieges 1919–1920,” Czasy Nowożytne 27 (2014): 157–84; William W. Hagen, “The Moral Economy of Popular Violence: The Pogrom in Lwów, November 1918,” in Antisemitism and its Opponents in Modern Poland, edited by Robert Blobaum (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2005), 124–47.

29 Eva Reder, “Pogrome im Schatten polnischer Staatsbildung 1918–1920 und 1945/46: Auslöser, Motive, Praktiken der Gewalt” (PhD, Universität Wien, 2017); William W. Hagen, Anti-Jewish Violence in Poland, 1914–1920 (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2018).

30 Much more detailed is Włodzimierz Borodziej and Maciej Górny, Nasza Wojna, vol. 2: Narody, 1917–1923 (Warsaw: Foksal, 2018).

31 Tim Wilson, Frontiers of Violence: Conflict and Identity in Ulster and Upper Silesia 1918–1922 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010); Edward Długajczyk, Polska konspiracja wojskowa na Ślasku Cieszyńskim w latach 1919–1920 (Katowice: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Ślaskiego, 2005).

32 Leszek Kania, W cieniu Orląt Lwowskich: Polskie sądy wojskowe, kontrwywiad i służby policyjne w bitwie o Lwów 1918–1919 (Zielona Góra: Uniwersytet Zielonogórski, 2008).

within and along the frontlines of embattled Poland. Warsaw alone boasts three vast and relevant collections.33

Nevertheless, in the first three chapters of this work which give a fresh outline of the prehistory and course of the postwar conflicts, the reader will look in vain for archival sources which provide new and groundbreaking evidence. They are almost entirely based on secondary literature. This surely comes as a surprise, given the fact that this study radically challenges the conventional view of the reconstruction of Poland 1918–21. The explanation is stunningly simple: There is no need to present new evidence, the related facts are already described in the history books and publications of sources. The problem is that their bits and pieces are scattered all over tens of thousands of book pages, like the pieces of a giant puzzle a child has dropped on the floor, and nobody yet has taken the effort to put these pieces together. It seems as if historians who knew about the dark sides of the Polish struggle for independence and statehood hesitated to confront their audience with them and referred to them only in passing, if at all. Therefore, anyone who doubts the accurateness and diligence of this study can check most of the presented facts in a public library.

However, Polish soldiers’ acts of desertion, insubordination, banditry, and violence against fellow soldiers and civilians are not totally unknown to the historical guild (the few books and articles that deal with them having just been mentioned). Some of these are exemplarily described and analyzed in Chapter 4, and backed mainly by archival material. Many of the hundreds of files of the Polish military commands, courts, and police which contain crucial evidence are stored in the Central Military Archive in Warsaw-Rembertów, and their user’s registers bear the signatures of known colleagues who have consulted them, but obviously decided not to publish about the criminal acts they record.

Since the Polish case is at the center of this study, this volume will by definition focus on the experience of violence connected to the making of the Second Polish Republic during that period. This should not obscure the fact that military and paramilitary violence was an omnipresent phenomenon all over postwar Europe, and, therefore, the Polish example is by no means an exception, but a case in point.34 It should also not be overlooked that building up the Polish nation amid the rubble of a devastating world war and civil war was an enormous achievement against all odds. It required the efforts of many and claimed the lives of many more on the way to securing freedom, self-determination, and peace for millions. Most probably the Red Army would not have had the power to invade Western Europe in the summer of 1920, but was anyone living there really eager to find out? Nevertheless, it was Polish soldiers only, without assistance from the West, who stopped it at the outskirts of Warsaw. Whereas in Polish historiography and

33 The Central Military Archive, the Archive of the New Files, and the manuscript department of the Warsaw Public Library. For relevant record groups see “Archives Consulted” at the end of this volume.

34 See Robert Gerwarth, The Vanquished: Why the First World War Failed to End, 1917–1923 (London: Allen Lane, 2016), Tomas Balkelis, War, Revolution, and Nation-Making in Lithuania, 1914–1923 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2018), and the forthcoming book of Serhy Yekelchyk (on Ukraine) in this OUP series “The Greater War.”