Contents

Preface xi

Acknowledgments xiii

1. Cancer biology and pathology

The distress of cancer 1

Extrinsic influences on cancer 3

Features of cancer development and progression 9

Cancer processes 10

Sources of cancer 13

Treatment resistance 20

Metastases 21

Ingredients for cancer growth and metastasis 23

Impact of hormones and hormone receptors on cancer processes 28

Inflammatory factors in the cancer process 29

Intrinsic vs extrinsic contributions to cancer occurrence 33

Summary and conclusions 34

References 34

2. Cancer and immunity

Changing times concerning diseases 39

Fundamentals of immunity 40

Innate and adaptive components of the immune system 43

Anatomy of the immune system: The lymphoid system 52

Adaptive (acquired) immunity 53

Cytokines 60

Inflammasome 63

Immune tolerance 65

Summary and conclusions 66

References 66

3. Microbiota and health

How it began 69

Features of microbiota 70

An evolutionary perspective 72

Microbiota development 75

Microbiota and immune functioning 80

Microbiota and illness comorbidities 83

Identifying good and bad microbes 87

The influence of environmental toxicants 88

Summary and conclusions 89

References 89

4. Genetic and epigenetic processes linked to cancer

Genetics and natural selection: The good and the bad 93

From Mendelian genetics to molecular biology 94

DNA and RNA 98

Epigenetic processes 110

Complex gene × environment interactions 119

Population-level genetics 121

Precision (personalized) medicine 125

Summary and conclusions 129

References 130

5.

Stressors:

Psychological and neurobiological processes

Attributions and misattributions of stressor effects on illness 135

Features of stressors 136

Chronic stressors and allostatic load 137

Stress sensitization 139

Identifying and responding to stressors 139

Resilience and vulnerability 145

Neurobiological actions of stressors 147

Growth factors 157

Cellular stress responses 164

Prenatal and early-life stressor effects 165

Summary and conclusions 171

References 172

6. Stress, immunity, and cancer

Blame it on stressor experiences 178

Brain and immune system interactions 178

Stressor influences on immunity 182

Cytokine variations associated with stressors 187

Stress and microbiota 191

Stressful events and cancer 195

Influence of psychosocial stressors on immunity and cancer 202

Prenatal and early-life stressors in relation to cancer 204

Influence of diverse life stressors 207

Psychological factors associated with cancer treatment 212

Linking neuropsychiatric and neurodegenerative disorders to cancer 217

Summary and conclusions 218

References 219

7. Eating and nutrition links to cancer

Then and now 225

The digestive process 227

Hormonal and brain processes underlying eating 229

Diets and weight loss 234

Diet and nutrition in relation to cancer 239

Summary and conclusions 248

References 249

8. Dietary components associated with being overweight, having obesity, and cancer

Being overweight or having obesity as a health risk 253

Linking the development of obesity to cancer 254

Relations between obesity, immunity, inflammation, and cancer 257

Genetic influences on obesity 260

Dietary components in relation to cancer and its treatment 262

Summary and conclusions 274

References 275

9. Microbiota in relation to cancer

Finding the right microbial mix 279

Microbiota in relation to cancer 282

Short-chain fatty acids 288

Influence of specific microbiota in diverse forms of cancer 292

Parasites and cancer 298

The inflammatory link between microbiota and cancer 298

Impact of the prenatal and perinatal diet 301

The other side of microbiota: Is there value to prebiotic and probiotic supplements? 304

Summary and conclusions 304

References 305

10. Exercise

The broad effects of exercise 311

Immune and cytokine changes associated with exercise 312

Cytokine changes associated with exercise 314

Exercise and cancer prevention 316

Impact of exercise on existent cancers 318

Impact of exercise on cancer features and side effects of treatments 322

Fueling cancer progression 327

Exercise and microbiota 329

Sedentary behaviors 332

The social element 334

Roadblocks to exercise and how to get around them 334

Summary and conclusions 336

References 337

11. Sleep and circadian rhythms

A brief history of thoughts and research related to sleep 341

Functions of sleep 343

Links between sleep and other lifestyle factors 345

Neurobiological aspects related to sleep and circadian rhythms 347

Circadian rhythms: Immune and cytokine changes 349

Sleep, circadian rhythms, and cancer progression 352

Occupations associated with altered sleep cycles and cancer occurrence 358

Sleep disruption and diurnal variations in relation to microbiota 361

Implications of circadian rhythmicity to cancer treatments 363

Summary and conclusions 364

References 365

12. Adopting healthy behaviors: Toward prevention and cures

Understanding counterproductive behaviors 369

A brief look back 370

Intervention approaches 372

Changing attitudes and behaviors and barriers to change 374

Psychosocial and cognitive approaches to enhance health behaviors 378

Positive psychology 390

Social support 392

Summary and conclusions 396

References 396

13. Cancer therapies: Caveats, concerns, and momentum

Promises, promises 401

Cancer screening 402

Cancer screening in common types of cancer 403

Caveats concerning screening and early cancer detection 406

Unintended consequences and unintended benefits 411

Progress in cancer treatment development 412

Complementary and alternative medicine 416

Precision treatment: Obstacles and challenges 419

Summary and conclusions 426

References 427

14. Traditional therapies and their moderation

The role of serendipity 431

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy 432

The challenge of treatment resistance 438

Nutrients related to treatment resistance 443

Manipulating energy and metabolism 444

Microbiota in relation to chemotherapy 451

Summary and conclusions 455

References 455

15. Immunotherapies and their moderation

Immunotherapeutic approaches 462

Stem cell therapy 464

Nonspecific immunotherapies 467

Treatment vaccines 471

Antibody-based therapies 474

Enhancing immunotherapy’s effectiveness 479

Side effects of checkpoint inhibitors and CAR T therapy 482

Use of biomarkers 485

Influence of microbiota on treatment responses to cancer therapies 489

Prebiotics and probiotics in cancer treatment 495

Summary and conclusions 497

References 497

16. Moving forward—The science and the patient

Where we stand 503

Moving forward 504

Prevention vs treatment 506

Living with dignity 509

Dying with dignity 512

Summary and conclusions 514

References 515

Index 517

Cancer biology and pathology

Henning Mankell, the Swedish author most notable for the creation of the fictional (and somewhat morose) detective, Kurt Wallander, offered the following reflection after being diagnosed with lung and neck cancer: “I remember that time as a fog, a shattering mental shudder that occasionally transmuted into an imagined fever. Brief, clear moments of despair. And all the resistance my willpower could muster. Looking back, I can now think of it all as a long drawn-out nightmare that paid no attention to whether I was asleep or awake.”a

a https://www.theguardian.com/lifeandstyle/2014/feb/12/henning-mankell-diagnosed-cancer.

Cancer is a frightening illness. It is an intractable, often incurable disease with a history of treatments that are experienced as brutal, dehumanizing, and distressing. Even when patients are designated “cancer survivors,” they may be acutely aware that if the disease recurs, further treatment may be worse and less tolerable. Indeed, patients typically undergo repeated testing to determine whether the cancer has recurred, experiences that can raise questions of treatment-related damage, and the uncertainty of waiting for the “other shoe to drop.” To extend Mankell’s thoughts, it is not only a nightmare to process the diagnosis, but one that can extend into the postdiagnosis treatment and recovery phase.

It is not uncommon for people to believe that they have been afflicted with cancer due to factors outside their control. Perhaps unwitting exposure to environmental toxicants, inheriting mutated genes, or eating the wrong foods and not being a better or calmer person have placed them at risk—any manner of theories will pass through a person’s thoughts as they fathom the reasons for their condition. With the exception of environmental disasters—such as the Chernobyl nuclear meltdown or, more recently, the Fukushima nuclear disasters—it can be difficult to make causal links between any number of factors and the appearance of cancer. In effect, in many ways, cancer occurrence is outside an individual’s control, most especially if it is inherited. Yet in other respects, individuals do have a say in determining their destiny and can take preventative measures: not smoking, limiting sun exposure, avoiding certain foods, not becoming overweight, engaging in exercise, not becoming dependent on alcohol, being vaccinated against carcinogenic viruses—all courses of action that can reduce cancer risk.

Once an individual becomes a patient—which in and of itself is a distinction that may be significant—he or she may have some control in the selection of treatments; but often this is illusory, as they likely know and understand little about the therapies being discussed with them and often simply follow the advice of the treating oncologist. In recent years, this blind trust on the part of patients has been replaced, to a modest extent, by patients wanting to understand more about the disease and its treatment, so that they can make informed choices. It is not unusual for patients to opt for unsubstantiated alternative treatments (e.g., herbal medicines gleaned from the internet) or complementary adjunct treatments (e.g., natural treatments to supplement standard medications) either because of their mistrust or fear of traditional treatments. It is not uncommon for people to display skepticism toward medical care, and in the face of multiple alternative points of view (legitimate and illegitimate), it can leave a patient confused and open to exploitation.b

When an individual suspects the presence of cancer, this triggers a cascade of perceived and actual threats. The anticipation and anxiety related to a cancer diagnosis are invariably distressing, most notably among individuals who are less adept at dealing with uncertainty, which only

b At the time of this writing, the historic repercussions of the COVID-19 pandemic have highlighted deep class, race, and political divisions, as well as a profound distrust of the biomedical scientific community, whose urgent calls for social isolation have promoted economic hardship due to business closures. With societies subjected to unrelenting stress, crackpot theories and treatments are being given equal weight with more traditional, tried, and true approaches (viz., safe use of effective vaccines) that have withstood the rigor of scientific scrutiny. To think that the range of options open to a cancer patient may not leave them bewildered and helpless is unrealistic. This would be especially the case when people are disadvantaged by a lack of adequate knowledge and/or insufficient social support networks that might help them make an informed decision.

leaves them more vulnerable to psychological disturbance. The distress is exacerbated with frequent delays in obtaining treatment, especially as this might allow the cancer to progress to stages of pathology that could predict undesirable treatment outcomes. These factors, together with the treatment itself, may result in patients experiencing cognitive disturbances as well as chronic anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Cordova et al., 2017).

Overall, the diagnosis and treatment of cancer envelop the individual in a cloud of uncertainty, physical discomfort, and overwhelming psychological imbalance. The therapy itself may precipitate such problems, but it is important to note that the extreme distress of knowing, living, and even surviving cancer can contribute further to these problems. The individual’s holistic mind-body state needs to be addressed, taking into account that the person’s psychosocial relations with others also need to be considered if their battle with cancer is to have outcomes that positively impact both physical and psychological well-being.

Extrinsic influences on cancer

The etiology of disease now encompasses models that combine genetic factors with environmental chemicals, as described in Fig. 1.1. The figure illustrates the concept of an “exposome,” an aggregation of numerous nongenomic factors that provoke biological changes that

• Psychosocial

Social support & connectivity, social capital, culture, socioeconomic level, stressors, coping ability

Built environment, natural environment, access to walking trails and gyms, safe spaces

• Ecosystems

• Lifestyles

Diet, exercise vs sedentary behavior, sleep, substance use, population density

Environmental (air, water, soil, food) contamination, pollutants, noise, odors, light, climate change

• Physical & chemical factors

FIG. 1.1 Both good health and illness are determined by intrinsic factors (e.g., biological processes) and extrinsic factors. These extrinsic factors, sometimes referred to as exposome, comprise psychosocial factors, lifestyles endorsed, ecosystems, and encounters with physical-chemical stimuli. Some of the many components of each sector of the exposome are provided in the figure. These are not independent of one another, and their dynamic interactions influence one another and influence biological processes that affect quality of life and health. Based on Vermeulen, R., Schymanski, E.L., Barabási, A.L., Miller, G.W., 2020. The exposome and health: where chemistry meets biology. Science 367, 392–396.

create the circumstances for disease (Vermeulen et al., 2020). The development and progression of many types of cancer, as well as the response to cancer treatments, can be influenced by numerous environmental and lifestyle factors (diet, exercise, sleep). These may exert their effects through hormonal changes, inflammatory immune events, microbial colonization, and other biological mechanisms.

Cancer is often considered as a disease of cellular aging and prevention of this disease could be achieved, in a sense, by turning back the clock. One of the factors that may contribute to cellular aging is the accumulation of epigenetic changes in which the actions of genes are altered (suppressed or enhanced) without frank alterations of the genome. Thus, it is fascinating that a lifestyle manipulation that comprised an 8-week program in which individuals engaged in healthy eating, exercise, enhanced sleep, and relaxation training, supplemented by foods that provide probiotics and phytonutrients, was sufficient to diminish DNA-related epigenetic variations. Even this relatively short-term intervention seemed to turn back the DNA clock by about 3 years and thus could have profound implications for age-related diseases (Fitzgerald et al., 2021). Lifestyle and environmental influences are also intertwined with stress responses and behavioral and psychosocial functioning, which can affect immune and neurobiological processes. These varied factors may collectively impact cancer progression or recurrence and, importantly, may undermine the efficacy of cancer treatments.

Maintaining a healthy diet, engaging in exercise, avoiding sedentary behaviors, and diminishing stressful experiences may have benefits in preventing the occurrence of diseases, and there is reason to believe that these lifestyle choices can diminish the progression of some forms of cancer. For all its limitations standard cancer therapies have been effective in diminishing mortality stemming from many forms of cancer, but there has been considerable criticism of how slowly such advances have been made. This has encouraged the view that the answer to limit cancer deaths will largely come from modifications of lifestyles and the adoption of remedies; however, in many instances these remedies are simply too far out to be credible. Perhaps some of these approaches may have some value, but such perspective needs to be matched by convincing and reliable data that far too often haven’t been provided. So, patients are often faced with the dilemma of following the science that hasn’t uniformly provided cures on the one hand and adopting entirely untested and uncertain remedies on the other.

Within most developed countries, about 35% of people will be affected by some form of cancer, although rates in certain countries are appreciably lower (e.g., in Japan, Israel, Poland, Iceland), and nearly 30% of patients eventually develop a secondary metastatic tumor. According to the World Health Organization, cancer is the second leading cause of death globally (heart diseases are at the top) with 9.6 million deaths being attributable to some form of cancer. Of these deaths, about 70% occur in low- and middle-income countries, with various lifestyle factors (cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, diet and obesity, poor food choices, and lack of exercise) being the greatest contributors. In ensuing chapters, we will consider these and other risk factors in greater detail, along with the possibility that avoiding or modifying these risks can be done through sensible prevention strategies.

The frequency of cancer occurrences coupled with the difficulties so often encountered during and after treatment led to altered patient care strategies. Among other things, this required continued surveillance regarding the individual’s well-being and the recurrence of illness, and because of the protracted effects of cancer and its treatment, the development of other health problems needed to be considered. This entailed the involvement of specialties

other than oncology (e.g., endocrinologists, dieticians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, and specialists to deal with pain management), and greater patient engagement in selecting their treatment. There was also an obvious need for patient mental health to be considered in much greater depth than it had been previously, which encouraged the inclusion of clinical psychologists and/or psychiatrists in attending to patient needs. The availability of such broad treatment teams was thought to improve quality of life for patients, and there was the belief—albeit still debatable—that this would enhance the effectiveness of chemotherapy and radiation therapy.

The broad landscape

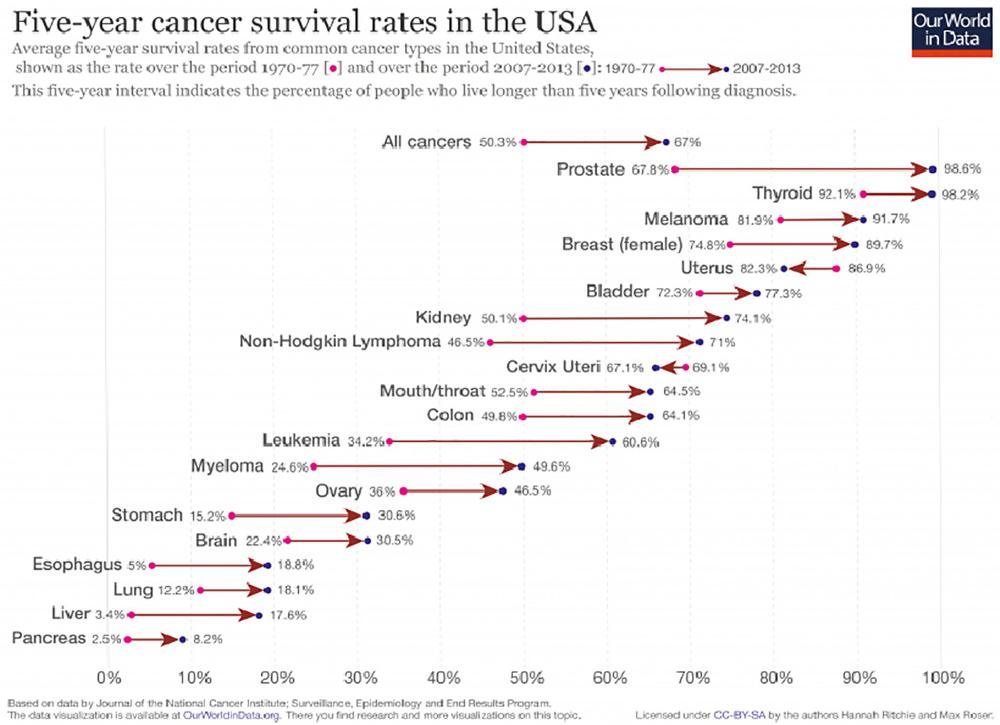

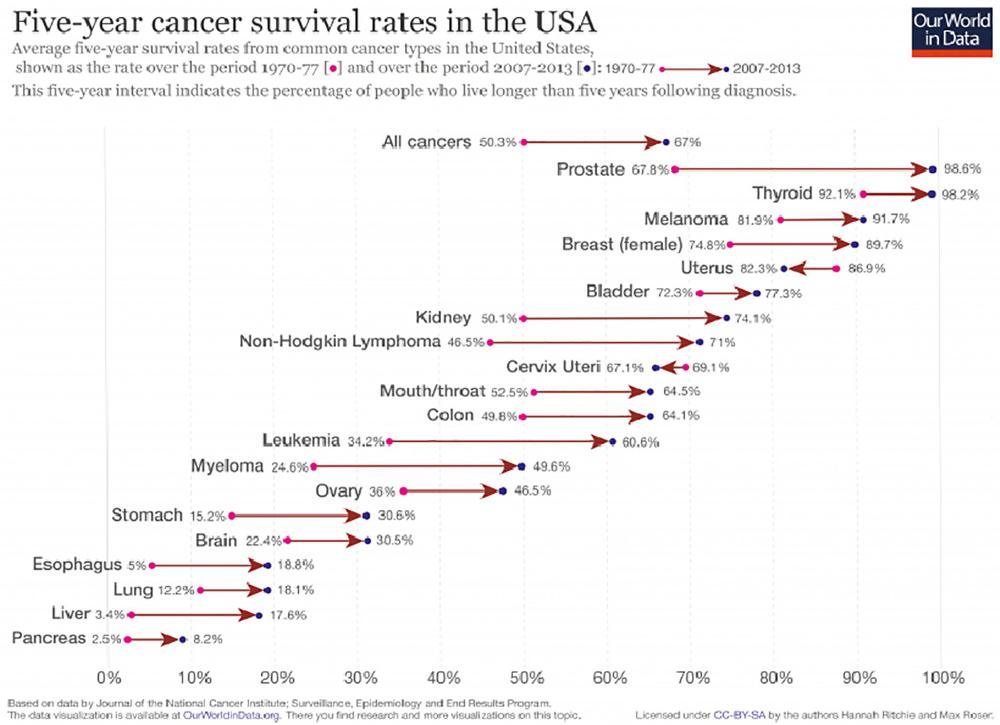

As depicted in Fig. 1.2, efforts to keep cancer patients alive longer have improved markedly over the past four decades, although for some cancers the advances have been limited. These data reflect the situation in the United States but are matched by data from the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and much of the European Union (EU) (Carioli et al., 2020). In developing countries, the situation has been improving, but still lags Western countries. What

FIG. 1.2 Five-year survival rates determined over a 36–37-year period increased appreciably for several types of cancer (e.g., leukemia, myeloma) or have become highly treatable (prostate, thyroid cancer) or moderately treatable illnesses (melanoma, breast, uterine, bladder, and kidney cancer). Some improvements were also realized with esophageal, lung, liver, and pancreatic cancer, but the outlook for these forms of cancer have generally been grim. Figure and caption from Roser, M., Ritchie, H., 2018. Our World in Data: Cancer. https://ourworldindata.org/cancer. Retrieved Jan 2020.

this figure does not show is that no matter which country is examined, disparities exist with sex, ethnicity (race), and socioeconomic status (e.g., Ginsburg et al., 2017). Likewise, it does not portray the physical and mental cost of the illness and its treatment, nor what life is like for cancer survivors. This can vary with the treatments received, the individual’s age, and a constellation of psychosocial factors. Typically, life span might not be the only or even the most important issue that preoccupies cancer patients. Instead, they may be more concerned with health span following treatment, which essentially amounts to the years lived without further illness or disability, defining the capacity to which they are happy and fulfilled.

The most recent update regarding the overall occurrence of cancer indicated that incidence rates for cancer among males have been stable, whereas that among women increased somewhat between 2013 and 2017, and this was also apparent among children, adolescents, and young adults (Islami et al., 2021). As depicted in Fig. 1.3, these statistics vary appreciably across different forms of cancer. In contrast, in both sexes, cancer-related deaths declined during this period, although again this depended on the nature of the cancer and varied between sexes. Among males, cancer-related death rates declined in 11 of the 19 forms of cancer, and in females, a decline was reported in 14 of the 20 types of cancer, including some of the deadliest cancers (e.g., melanoma, lung cancer).

As encouraging as it is to see increased survival among cancer patients, one should not assume that cancer elimination equates with full health restoration. In destroying cancer cells, standard cytotoxic treatments also kill healthy cells and may engender inflammation in many neighboring cells. Aside from the possibility of the cancer recurring, treatments may cause organ damage (including the heart, lung and airways, liver, and kidney), osteoporosis, persistent pain, sexual dysfunction and infertility, lymphedema (lymphatic fluid buildup in tissues, which produces painful inflammation, swelling, and restricted movement), and in response to some treatments, urinary or bowel (fecal) incontinence. Some of these consequences may not appear until years later. For instance, among individuals who survived childhood cancer (e.g., leukemia), it was common (80%) for a severe illness to occur before survivors reached 45 years of age. The protracted effects of therapies range broadly. Some were not life-threatening and were often being as “manageable,” such as hearing loss (62%), memory problems (25%), male infertility (66%), and female infertility (12%). Others, however, comprised serious life-threatening conditions, including cardiac disturbances (in 63% of individuals), abnormal lung functioning (65%), and endocrine dysfunction (61%). In some instances, a second cancer appeared, possibly owing to genetic factors that favor the emergence of different types of cancer or perhaps due to the initial cancer treatment. Gentler treatments are thought to diminish these long-term side effects, and a personalized treatment approach may offer the hope of diminished proactive effects.

The cancer treatment landscape has been changing over the past decade, but it is certain that much more needs to be achieved. Historically, the focus of most research had been on factors related to cancer diagnosis and treatment with less attention devoted to cancer prevention. But it is now common knowledge that behavior is a common mode of facilitating the onset of some cancers—e.g., to avoid lung, throat, and skin cancer the prescription is don’t smoke and avoid prolonged direct exposures to the sun. It would be rare to find people who would consider such advice as inappropriate, although it wasn’t always accepted that smoking caused cancer or that certain rays of the sun can promote melanoma. Indeed, until a few decades ago children and teenagers spent as much time as possible in the sun, smothered in lotions that would

Cancer incidence, males

Melanoma of the skin

Kidney and renal pelvis

Pancreas

Oral cavity and phar ynx

Testis

Liver and intrahepatic bile duct

Myeloma

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Thyroid

Brain and other ner vous system

Colon and rectum

Stomach

Urinar y bladder

Lar ynx Lung and bronchus

Cancer incidence, females

Liver and intrahepatic bile duct

Melanoma of the skin

Kidney and renal pelvis

Myeloma

Corpus and uterus, NOS

Oral cavity and phar ynx

Stomach

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Brain and other ner vous system

Urinar y bladder

Colon and rectum

Lung and bronchus

Thyroid

FIG. 1.3 Average annual percent change (AAPC) in age-standardized, delay-adjusted incidence rates for the period 2013–17 for all sites and the 18 most common cancers in men and women of all ages, all races/ethnicities combined. The AAPC was a weighted average of the annual percent change (APCs) over the fixed 5-year interval (incidence, 2013–17) using the underlying joinpoint regression model, which allowed up to three different APCs, for the 17-year period 2001–17. AAPCs were significantly different from zero (two-sided P < .05), using a t-test when the AAPC laid entirely within the last joinpoint segment and a z-test when the last joinpoint fell within the last 5 years of data, and are depicted as solid-colored bars; AAPCs with hash marks were not statistically significantly different from zero (stable). Abbreviations: NOS, not otherwise specified. From Islami, F., Ward, E.M., Sung, H., Cronin, K.A., Tangka, F.K.L., et al., 2021. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, part 1: national cancer statistics. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. djab131.

enhance their tans, rather than blocking the harmful ultraviolet rays. Equally, the influence of diet, exercise, stress, and sleep on cancer occurrence had frequently been ignored or simply neglected, despite these lifestyle factors receiving attention in the context of heart disease and type 2 diabetes. It ought to go without saying that preventive strategies are largely an individual’s responsibility, but community-level preventive approaches might facilitate the adoption of methods to limit cancer development. Remarkably, however, until about a decade ago most people were unaware of the linkages between many lifestyle factors (e.g., diet, exercise) and cancer. c At that time it was not uncommon for people to believe that cancer was caused by injury, or that irreligiosity in some manner contributed to cancer occurrence. As well, there was limited awareness that diet or exercise was linked to cancer, and it was not unusual for people to believe that alternative medicines were as effective as standard therapies in cancer treatment

c It isn’t our intention to stand on a soap box preaching about what should or shouldn’t be done in relation to cancer prevention. Nobody likes the reformed sinner who takes every opportunity to hector others. Instead, as we deal with specific topics, we’ll simply present some of the data and describe the suspected reasons for certain agents or behaviors having the effects that they do. Changing people’s minds and behaviors in some instances is exceptionally difficult, witness for instance the ongoing debate between the antivaccine community and knowledgeable scientists who base their opinions on evidence (but who nonetheless seem to be banging their heads against a brick wall). Nevertheless, in Chapter 12, we will provide information relevant to behavior change strategies.

(Lord et al., 2012). Since then, there has been greater awareness of the sources of cancer occurrence, but a significant number of people are still unaware of the cancer risks associated with obesity or alcohol consumption (e.g., Meyer et al., 2019).

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews

The rate of scientific output has increased exponentially over the years, and as much as this ought to be advantageous, it is not unusual for inconsistent findings to be reported. This could occur owing to subtle or pronounced procedural differences between studies, or the findings of some studies may simply be unreliable for any number of reasons. Thus, it has become increasingly desirable to have cogent reviews of the literature that both synthesize the available literature and facilitate conclusions regarding where the bulk of evidence lies. Meta-analyses became a progressively more popular way of organizing and then reviewing large swaths of research while taking into account the effect size in each study (i.e., the strength of associations that exist between variables) and the number of participants in these studies (studies with a small number of participants are usually seen as being more prone to unreliable outcomes). Ordinarily, before undertaking the analyses, investigators specify inclusion and exclusion criteria for studies. This may entail the type of participants or research approach adopted in the studies, such as whether they involved retrospective or prospective approaches or whether they consisted of random controlled trials. By rigorously following sets of criteria, estimates can be determined as to how reliable and meaningful the results are, and what key variables could moderate the observed relationships.

Another approach of summarizing large amounts of data has entailed systematic reviews. These analyses follow rigorous guidelines concerning the specific issues to be addressed, the identification of the relevant work that should be included or excluded, and how to assess the quality of the research considered. Often, the data come from quantitative analyses, but qualitative analyses (e.g., individual narratives) can be included, and meta-analyses can be incorporated as part of a systematic review. It is of great importance that not all studies are given equivalent weight in that methodological issues might be considered by independent raters who determine the goodness of studies and hence the weight attributed to them. Numerous clinical conditions have been assessed using these approaches, including therapeutic methods to treat illnesses, the side effects of various treatments, and the effectiveness of social and public health interventions, as well as cost-benefit analyses related to the risks associated with particular treatments relative to what could be expected if treatments had not been applied.

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have been remarkably effective in summarizing large sets of studies to bring order and understanding disparate findings. However, these analyses can also be misleading. These reviews are only as good as the inclusion and exclusion criteria that are used in the analyses. For instance, a given analysis might include both observational studies and randomized controlled studies whereas another analysis might only include the latter, thus they may provide different conclusions. Likewise, some analyses might ignore certain variables, such as sex differences, and hence biased or inexact conclusions may be derived. Another serious shortcoming of these analyses is that they can only include the available reports, which are typically those that have been published in peer-reviewed journals. Most often, however, published reports comprise those that showed significant outcomes, whereas studies in which significant effects are not obtained are often never published. As a result, one could easily be misled to believe that a given treatment is effective when, in fact, many more experiments indicated otherwise. It may unfortunately take many years of research before it becomes apparent that certain treatments weren’t as effective as initially claimed.

Features of cancer development and progression

Cancers are characterized by uncontrolled cell growth, culminating in tumor development that can destroy surrounding tissue and spread promiscuously to other regions. Cancer cells are typically considered to be cells that can escape the main tumor mass (i.e., the primary tumor), migrate to remote sites via the vascular or lymphatic systems, and establish a new cancer colony (a metastasis or secondary tumor). For example, a biopsy on a lung tumor might reveal that the cells are actually from another organ (say, the pancreas), thereby establishing the tumor as a secondary tumor, and evidence of metastatic spread from the primary source (the pancreas). Such metastasizing cells present with a unique gene signature, which distinguishes them from more stable, nonmigrating cells that remain in the primary tumor. To a large degree cancer cells display unprogrammed and/or mutated behavior characterized by runaway mitosis, which becomes biologically threatening when unrestrained. The persistent cell division is a result of numerous cellular pathways being coopted to enable cells to avoid or disregard the inherent constraints on cell growth that are observed in healthy cells. In so doing, they modify their microenvironment to favor their survival and proliferation, drawing on energetic processes needed by normal cells and avoiding surveillance by cytotoxic immune cells. In short, cancer cells are capable of breaking through barriers that might otherwise restrict their growth and can spread to other organs. Such a situation is malignant because it impairs the function of colonized tissues and organs. In contrast, benign tumors do not invade or infiltrate into the cellular network of surrounding tissues or organs. These tumors grow as an isolated mass with their own capsule and, with some exceptions, lack metastatic capacity. Benign tumors do grow, but slowly, and in the best-case scenario, simply stop growing. And while they do not interfere with the physiological and biochemical functions of intrinsic cells in a tissue, they do compress nearby structures, thereby causing pain or other medical complications that will warrant their removal. Otherwise, benign tumors are sometimes judged to be better left alone.

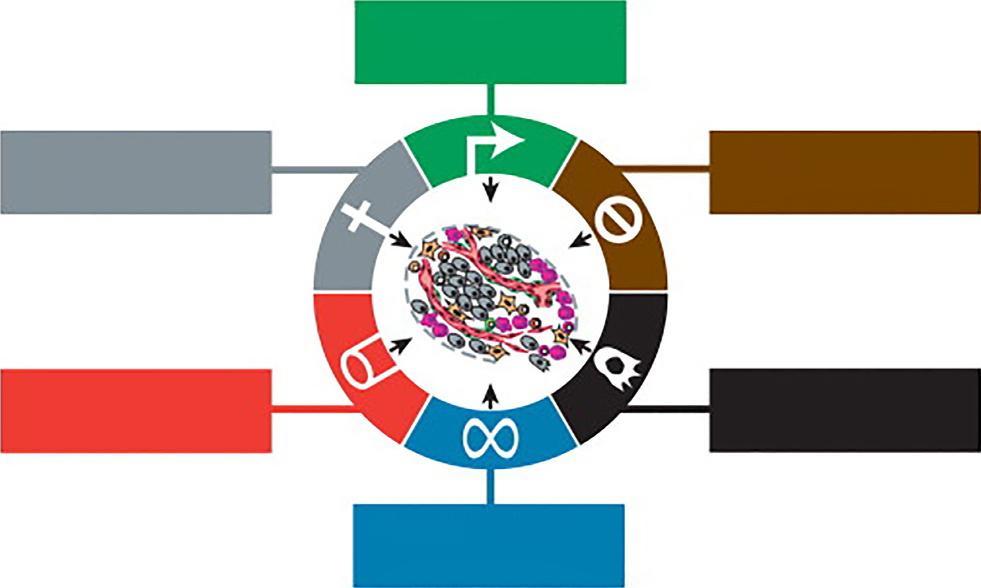

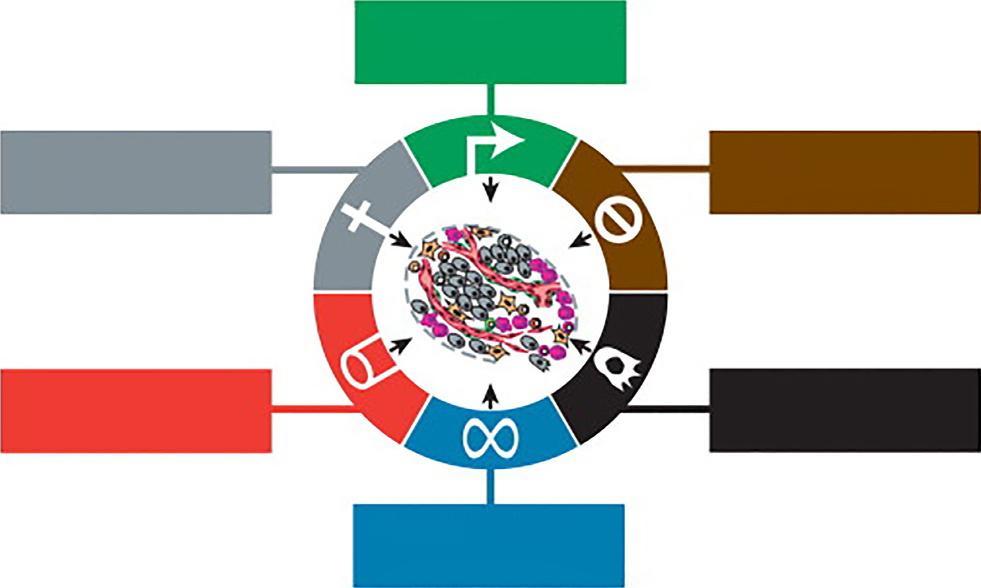

In their analysis of the elements that make for cancer development and spread, Hanahan and Weinberg (2011) identified six characteristics that are common among many forms of cancer. These hallmarks of cancer are shown in Fig. 1.4. Cancer cells are seen as self-sufficient in being able to respond to cell growth signals and insensitive to signals that inhibit growth. Moreover, in addition to being able to evade apoptosis (programmed cell death to eliminate cells that are damaged or contain potentially dangerous mutations), they have a remarkable capacity to replicate and to promote and sustain their growth. They can stimulate blood flow to themselves (angiogenesis), evade attempts of the immune system to destroy them, and can invade local tissues and metastasize. Beyond these features, inflammatory processes, and the ensuing genetic dysregulation, might represent a seventh essential characteristic that supports cancer processes.

In addition to these fundamental processes, several biomechanical features of tumors may sustain and enhance their growth and spread. Specifically, owing to permeable blood vessels in tumors that leak blood plasma into tissues surrounding the tumor, together with limited drainage of lymphatic fluid, elevated interstitial fluid pressure may be created that causes edema, the release of growth factors, and the facilitation of cancer cell invasion of nearby and distal tissues. As well, the proliferating and migrating cancer cells compress blood and lymphatic vessels, thereby disturbing blood flow and hence diminish immune cell presence and limit oxygen to the region and may concurrently hinder drug presence that would otherwise limit tumor growth. At the same time, the immune microenvironment surrounding a tumor may limit the access of immune cells, and interactions between cancer cells and their

FIG. 1.4 The six hallmarks of cancer that facilitate their growth and survival. From Hanahan, D., Weinberg, R.A., 2011. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell 144, 646–674.

microenvironment may be disturbed, consequently affecting signaling pathways that may affect cancer cell invasion and metastasis.

The tumor microenvironment is complex, typically being distinct from that of normal cells with respect to oxygen availability, metabolic processes, acidity, and interstitial fluid pressure. This environment, the battlefield between the cancer cells and a person’s defenses, holds considerable sway over tumor progression and the efficacy of various treatments. Cancer cells can influence and be influenced by the lymphocytes that had infiltrated the area as well as by the presence of stromal cells that make up connective tissues, fibroblasts (a type of cell present in connective tissue), blood vessels, and the extracellular matrix. The latter, a noncellular component present in tissues and organs, comprises the scaffolding for cells. Accordingly, approaches could be adopted to take advantage of the microenvironment to enhance the efficacy of varied therapeutic strategies.

Cancer processes

More than 200 forms of cancer have been identified, involving different organs and different cell types. In general, these cancers fall into distinct classes (see Table 1.1) and are also described by their stage of progression (the size of the tumor and how extensively it has spread). Cancers can also be distinguished from each other based on their genetic and epigenetic signatures, as well as the speed of expansion (viz., slow vs fast growth). They are also differentiated according to sensitivity to immune and hormonal mechanisms, such as whether they are influenced by certain hormones or inflammatory processes. Each type of cancer may contain multiple subtypes. Breast cancer, for instance, may comprise ductal, lobular, tubular, invasive, infiltrating,

Resisting cell death

Inducing angiogenesis

Enabling replica tive immor tality

Activating invasion and metastasis

Evading growth suppressors

Sustaining proliferative signaling

TABLE 1.1 Cancer classification.

Cancers are broadly classified within six main categories that affect different organs, such as breast, lung, prostate, or hematological cancers, or they may affect muscles or connective tissue (fat, cartilage, bone, fibrous tissue). Each of these broad classes can be broken down further into multiple subcategories.

• Carcinoma: involves the epithelial cells of tissues that line body surfaces and cavities. Cancers that affect skin and other organs, including the breast, prostate, colon, and lung are frequently carcinomas.

• Sarcoma: a cancer of connective tissues that includes cartilage, bone, tendons, adipose tissue, lymphatic tissue, and components of blood cells.

• Myeloma: a cancer that originates in the plasma cells of bone marrow.

• Lymphoma: These develop in the nodes or glands of the lymphatic system, the network of vessels, nodes, and organs, that serve to purify bodily fluids and produce white blood cells (lymphocytes) to fight infection. Lymphomas are broadly categorized as Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, as well as multiple myeloma and immunoproliferative diseases.

• Melanoma: This cancer originates in cells that contain melanin (melanocytes) and are primarily found on the skin, but can be found elsewhere (pigmented tissue, including the eye).

• Leukemia: a diffuse type of cancer (as opposed to a solid cancer) that originates in the bone marrow, culminating in abnormal white blood cells appearing in excessively high numbers (e.g., leukemia cells)

• Blastoma: a type of cancer that involves “blasts,” which are primitive and incompletely differentiated precursor cells. Several types of blastoma appear in children, and some forms—such as glioblastoma multiforme, which is the most aggressive brain tumor—appear in middle-aged adults.

• Brain and spinal cord tumors: these involve different types of cells and are named accordingly. These comprise astrocytic tumors, gliomas, oligodendroglial tumors, medulloblastomas, ependymal tumors, meningeal tumors, and craniopharyngioma.

• Germ cell tumor: a cancer involving germ cells (i.e., sperm or egg that unite during sexual reproduction). In essence, this type of cancer most often occurs within the ovaries or testis and can occur in babies and children.

• Mixed type: These may come from a single category or may span different categories (e.g., carcinosarcoma, adenosquamous carcinoma)

Modified from Anisman, H., 2021. Health Psychology: A Biopsychosocial Approach. SAGE, London.

mucinous, and medullary types, and can also be classified based on whether certain receptors are present, such as those for estrogen, progesterone, and HER2 (as in the case of triple-negative breast cancer). By virtue of this heterogeneity of cell types, each form of cancer requires a specific therapy, and even within a given cancer type, differences might prompt specialized treatments.

Classification

Cancer subtypes are classified based on the tissue affected, features of the cancer, and the extent to which the cancer has progressed (i.e., stage of the disease). These serve as prognostic indicators for the probability of successful treatment or life expectancy and guide the choice of treatment. For instance, when the cancer is localized, surgery may be selected, but chemotherapy may be adopted as an adjuvant therapy to eliminate cancer cells that might persist following surgery. The general diagnosis of cancer involves the use of a staging system that ranges from abnormal but not immediately dangerous cellular states to those that have advanced to a life-threatening pathological condition. These are summarized as follows:

• Stage 0, also referred to as carcinoma in situ, refers to cancer cells having been detected that have the potential to spread.

• Stage I, or early-stage cancer, refers to the cancer being small and localized to a specific area.