https://ebookmass.com/product/brain-computer-interfacesvolume-168-handbook-of-clinical-neurology-volume-168-1st-

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Trapped: Brides of the Kindred Book 29 Faith Anderson

https://ebookmass.com/product/trapped-brides-of-the-kindredbook-29-faith-anderson/

ebookmass.com

Neuroscience for Neurosurgeons (Feb 29, 2024)_(110883146X)_(Cambridge University Press) 1st Edition Farhana Akter

https://ebookmass.com/product/neuroscience-for-neurosurgeonsfeb-29-2024_110883146x_cambridge-university-press-1st-edition-farhanaakter/

ebookmass.com

Cardiology-An Integrated Approach (Human Organ Systems) (Dec 29, 2017)_(007179154X)_(McGraw-Hill) 1st Edition Elmoselhi

https://ebookmass.com/product/cardiology-an-integrated-approach-humanorgan-systems-dec-29-2017_007179154x_mcgraw-hill-1st-editionelmoselhi/

ebookmass.com

Lazy Manu2019s Guide to Enlightenment https://ebookmass.com/product/lazy-mans-guide-to-enlightenment/

ebookmass.com

Henke’s Med-Math: Dosage Calculation, Preparation, and Administration 8th Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/henkes-med-math-dosage-calculationpreparation-and-administration-8th-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Samuel Beckett and the Politics of Aftermath James Mcnaughton

https://ebookmass.com/product/samuel-beckett-and-the-politics-ofaftermath-james-mcnaughton/

ebookmass.com

Spectacles in the Roman World: A Sourcebook Siobhán Mcelduff

https://ebookmass.com/product/spectacles-in-the-roman-world-asourcebook-siobhan-mcelduff/

ebookmass.com

American government : institutions and policies Sixteenth Edition Bose

https://ebookmass.com/product/american-government-institutions-andpolicies-sixteenth-edition-bose/

ebookmass.com

Population and Community Health Nursing (6th Edition –Ebook PDF Version) 6th Edition – Ebook PDF Version

https://ebookmass.com/product/population-and-community-healthnursing-6th-edition-ebook-pdf-version-6th-edition-ebook-pdf-version/

ebookmass.com

Constitutional Change in the European Union: Towards a Federal Europe Andrew Duff

https://ebookmass.com/product/constitutional-change-in-the-europeanunion-towards-a-federal-europe-andrew-duff/

ebookmass.com

BRAIN-COMPUTER INTERFACES HANDBOOKOFCLINICAL NEUROLOGY SeriesEditors MICHAELJ.AMINOFF,FRANÇOISBOLLER,ANDDICKF.SWAAB

VOLUME168

ELSEVIER

Radarweg29,POBox211,1000AEAmsterdam,Netherlands TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates

Copyright©2020ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearanceCenter andtheCopyrightLicensingAgencycanbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher(other than asmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroadenour understanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecome necessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusingany information,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationormethodsthey shouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessional responsibility.

Withrespecttoanydrugorpharmaceuticalproductsidentified,readersareadvisedtocheckthemostcurrent informationprovided(i)onproceduresfeaturedor(ii)bythemanufacturerofeachproducttobeadministered,to verifytherecommendeddoseorformula,themethodanddurationofadministration,andcontraindications.Itis theresponsibilityofpractitioners,relyingontheirownexperienceandknowledgeoftheirpatients,tomake diagnoses,todeterminedosagesandthebesttreatmentforeachindividualpatient,andtotakeallappropriate safetyprecautions.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditorsassumeanyliability foranyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceorotherwise,or fromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthematerialherein.

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

ISBN:978-0-444-63934-9

ForinformationonallElsevierpublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: Nikki Levy

EditorialProjectManager: KristiAnderson

ProductionProjectManager: SujathaThirugnanaSambandam

CoverDesigner: AlanStudholme

TypesetbySPiGlobal,India

vHandbook of Clinical Neurology 3rd Series Available titles

Vol. 79, The human hypothalamus: basic and clinical aspects, Part I, D.F. Swaab, ed. ISBN 9780444513571

Vol. 80, The human hypothalamus: basic and clinical aspects, Part II, D.F. Swaab, ed. ISBN 9780444514905

Vol. 81, Pain, F. Cervero and T.S. Jensen, eds. ISBN 9780444519016

Vol. 82, Motor neurone disorders and related diseases, A.A. Eisen and P.J. Shaw, eds. ISBN 9780444518941

Vol. 83, Parkinson’s disease and related disorders, Part I, W.C. Koller and E. Melamed, eds. ISBN 9780444519009

Vol. 84, Parkinson’s disease and related disorders, Part II, W.C. Koller and E. Melamed, eds. ISBN 9780444528933

Vol. 85, HIV/AIDS and the nervous system, P Portegies and J. Berger, eds. ISBN 9780444520104

Vol. 86, Myopathies, F.L. Mastaglia and D. Hilton Jones, eds. ISBN 9780444518996

Vol. 87, Malformations of the nervous system, H.B. Sarnat and P Curatolo, eds. ISBN 9780444518965

Vol. 88, Neuropsychology and behavioural neurology, G. Goldenberg and B.C. Miller, eds. ISBN 9780444518972

Vol. 89, Dementias, C. Duyckaerts and I. Litvan, eds. ISBN 9780444518989

Vol. 90, Disorders of consciousness, G.B. Young and E.F.M. Wijdicks, eds. ISBN 9780444518958

Vol. 91, Neuromuscular junction disorders, A.G. Engel, ed. ISBN 9780444520081

Vol. 92, Stroke Part I: Basic and epidemiological aspects, M. Fisher, ed. ISBN 9780444520036

–

Vol.93,Stroke – PartII:Clinicalmanifestationsandpathogenesis,M.Fisher,ed.ISBN9780444520043

Vol.94,Stroke – PartIII:Investigationsandmanagement,M.Fisher,ed.ISBN9780444520050

Vol.95,Historyofneurology,S.Finger,F.BollerandK.L.Tyler,eds.ISBN9780444520081

Vol.96,Bacterialinfectionsofthecentralnervoussystem,K.L.RoosandA.R.Tunkel,eds.ISBN9780444520159 Vol.97,Headache,G.NappiandM.A.Moskowitz,eds.ISBN9780444521392

Vol.98,SleepdisordersPartI,P.MontagnaandS.Chokroverty,eds.ISBN9780444520067 Vol.99,SleepdisordersPartII,P.MontagnaandS.Chokroverty,eds.ISBN9780444520074

Vol.100,Hyperkineticmovementdisorders,W.J.WeinerandE.Tolosa,eds.ISBN9780444520142 Vol.101,Musculardystrophies,A.AmatoandR.C.Griggs,eds.ISBN9780080450315 Vol.102,Neuro-ophthalmology,C.KennardandR.J.Leigh,eds.ISBN9780444529039

Vol.103,Ataxicdisorders,S.H.SubramonyandA.Durr,eds.ISBN9780444518927

Vol.104,Neuro-oncologyPartI,W.GrisoldandR.Sofietti,eds.ISBN9780444521385 Vol.105,Neuro-oncologyPartII,W.GrisoldandR.Sofietti,eds.ISBN9780444535023 Vol.106,Neurobiologyofpsychiatricdisorders,T.SchlaepferandC.B.Nemeroff,eds.ISBN9780444520029 Vol.107,EpilepsyPartI,H.StefanandW.H.Theodore,eds.ISBN9780444528988 Vol.108,EpilepsyPartII,H.StefanandW.H.Theodore,eds.ISBN9780444528995

Vol.109,Spinalcordinjury,J.VerhaagenandJ.W.McDonaldIII,eds.ISBN9780444521378

Vol.110,Neurologicalrehabilitation,M.BarnesandD.C.Good,eds.ISBN9780444529015

Vol.111,PediatricneurologyPartI,O.Dulac,M.LassondeandH.B.Sarnat,eds.ISBN9780444528919

Vol.112,PediatricneurologyPartII,O.Dulac,M.LassondeandH.B.Sarnat,eds.ISBN9780444529107 Vol.113,PediatricneurologyPartIII,O.Dulac,M.LassondeandH.B.Sarnat,eds.ISBN9780444595652

Vol.114,Neuroparasitologyandtropicalneurology,H.H.Garcia,H.B.TanowitzandO.H.DelBrutto,eds. ISBN9780444534903

Vol.115,Peripheralnervedisorders,G.SaidandC.Krarup,eds.ISBN9780444529022 Vol.116,Brainstimulation,A.M.LozanoandM.Hallett,eds.ISBN9780444534972

Vol.117,Autonomicnervoussystem,R.M.BuijsandD.F.Swaab,eds.ISBN9780444534910

Vol.118,Ethicalandlegalissuesinneurology,J.L.BernatandH.R.Beresford,eds.ISBN9780444535016 Vol.119,NeurologicaspectsofsystemicdiseasePartI,J.BillerandJ.M.Ferro,eds.ISBN9780702040863 Vol.120,NeurologicaspectsofsystemicdiseasePartII,J.BillerandJ.M.Ferro,eds.ISBN9780702040870 Vol.121,NeurologicaspectsofsystemicdiseasePartIII,J.BillerandJ.M.Ferro,eds.ISBN9780702040887 Vol.122,Multiplesclerosisandrelateddisorders,D.S.Goodin,ed.ISBN9780444520012 Vol.123,Neurovirology,A.C.TselisandJ.Booss,eds.ISBN9780444534880

Vol.124,Clinicalneuroendocrinology,E.Fliers,M.KorbonitsandJ.A.Romijn,eds.ISBN9780444596024

V1 AVAILABLE TITLES (C研tinuoo)

Vol. 125, Alcohol and the nervous system, E.V. Sullivan and A. PfelTerbaum, eds. ISBN 9780444626196

Vol. 126, Diabetes and the nervous systen1, O.W. Zochodne and R.A. Malik, eds. ISBN 9780444534804

Vol. 127, Traumatic brain injury P'art I, J.H. Grafman and A.M. Salazar, eds. ISBN 9780444528926

Vol. 128, Traumatic bmin injury Part U, J.H. Grafman and A.M. Sala纽, eds. ISBN 9780444635211

Vol. 129, The human auditory system: Fundamental organization and c血cal disorders, G.G. Celesia and G. Hickok, eds. ISBN 9780444626301

Vol. 130, Neurology of sexual and bladder disorders, O.B. Vodu如k and F. Boller, eds. ISBN 9780444632470

Vol. 131, Occupational neurology, M Lotti and M.L. Bleecker, eds. ISBN 9780444626271

Vol. 132, Neurocu比neous syndromes, M.P. Islam and E.S. Roach, eds. ISBN 9780444627025

Vol. 133, Autoimmune neurology, S」Piuock and A. Vincent, eds. ISBN 9780444634320

Vol. 134, Gliornas, M.S. Berger and M. Weller, eds. ISBN 9780128029978

Vol. I35, Neuroimaging Part I, J.C. Masdeu and R.G. Go迅lez, eds. ISBN 9780444534859

Vol. I36, Neuroimaging Part II, J.C. Ma吐eu and R.G. Gon动lez.. ed.s. ISBN 9780444534866

Vol. 137, Neuro-otology, J.M. Furman and T. Lempert, eds. ISBN 9780444634375

Vol. I38, Neuroepidemiolo切, C. Rosano, M.A. Ucram and M. Ganguli, eds. ISBN 9780I28029732

Vol. 139, Functional neurologic disorders, M. Hallett, J. Stone 叩d A. Carson, eds. ISBN 9780128017722

Vol. 140, Critical care neurology Part I, E.F.M. Wij小cks and A.H. Kramer, eds. ISBN 9780444636003

Vol. 141, Critical care neurolo窃Part U, E.F.M. Wijdicks and A.H. Kramer, eds. ISBN 9780444635990

Vol. 142, Wilson disease, A. Czlonkowska and M.L. Schilsky, eds. ISBN 9780444636003

Vol. 143, Arteriovcnous and cavemous malformations, R.F. Spet2ler, K. Moon and R.O. Almefly, eds. ISBN 9780444636409

Vol. 144, Huntington disease, A.S. Feigin and K.E. Anderson, eds. ISBN 9780128018934

Vol. 145, Neuropathology, G.G. Kovacs and I. Alafuzoft; eds. ISBN 9780128023952

\bl. 146, Cerebrospinal fluid in neurologic disorders, F. Oeisenhammer, C.E. Teunissen and H. Tumani, eds. ISBN 9780128042793

Vol. 147, Neurogenetics Part l, O.H. Gescbwind, H.L. Paulson and C. Klein, eds. ISBN 9780444632333

Vol. 148, Neurogenetics Part U, D.H. Geschwind, H.L. Paulson and C. Klein, eds. ISBN 9780444640765

Yol. 149, Metastatic diseases of the nervous system, 0. Schiffand M.J. v叩 den Bent, eds. ISBN 9780128111611

Yol. 150, Brain banking in ncurologie and psychiatrie diseases, L Huitinga and M.J. Webster, eds ISBN 9780444636393

Vol. 151,.几e parietal lobe, G. V;tllar and H.B. Coslett, eds. ISBN 9780444636225

Vol. 152, The neurology ofHIV infection, BJ. Brew, ed. ISBN 9780444638496

Vol. 153, Human prion diseases, M. Pocchiari and J.C. Manson, eds. ISBN 9780444639455

Yol. 154, The cerebellum: From embryol处;y to diagnostic investigations, M. Manto and T.A.G..M. Huisman, eds ISBN 9780444639561

Vol. 155, The cerebellum: Disorders and treatn1ent, M. Manto and T.A.G.M. Huisman, eds. ISBN 9780444641892

Yol. 156, Thermoregulation: from basic neuroscience to clinical neurology Part I, A.A. Romanovsky, ed. ISBN 9780444639127

Vol. 157,Thermoregulation: From basic neuroscience to clinical neurology Part II, A.A Romanovsky, ed ISBN 9780444640741

Vol. 158, Sports neurology, B. Hainline and R.A. Stern, eds. ISBN 9780444639547

Vol. 159, Balance, gait, and falls, B.L. Day and S.R. Lord, eds. JSBN 9780444639165

Vol. 160, Clinical neurophysiology: Basis and technical a平ctS, K.H. Levin ,md P. Chauvel, eds. ISBN 9780444640321

Vol. 161,Clinical neurophysiology.: Diseases and disorders, K.H. Le\'in and P. Chauvel, eds. ISBN 9780444641427

Vol. 162, Neonatal neuroloi,,y, L.S. Oe Vries and H.C. Glass, eds. ISBN 9780444640291

Vol. 163, The fron也I lobes, M. O'Esposito and J.H. Grafrnan, eds. ISBN 9780128042816

Vol. 164, Smell and taste, Richard L. Doty, ed. ISBN 9780444638557

Vol. 165, Psychopharmacology of neurologic disease, V.I. Reus and D. Lindqvist, eds. ISBN 9780444640123

Vol. 166, Cingulatc cortex, BA Vogt, 叫ISBN 9780444641960

Vol. 167, Geriatric neurology, S.T. OeKosky and S. Asthana, eds. ISBN 9780128047668

All volumes in the 3rd Series ofthe Handbook of Clinical Neurology are published electronically, on Science Oir忱t: h1tp://www.sciencedircc1.co111'science/lrnndbooks/00729752

Foreword Amongthefeaturesdifferentiatinghumansfromotherspecies,onestandsout:theabilitytomanufactureanduse complextoolsandinstruments,manyofwhichhavetrulyrevolutionizedourwayoflife.Twoofthesearethestarting pointofthisvolume.First,computers,theinventionofwhichmaygoback500yearstoLeonardodaVinci(orperhaps othersbeforehim)and,inthemodernage,toAlanTuring.Certainly,50orsoyearsago,fewwouldhavepredictedthat insomeformtheywouldbeinthehandsofhalfthepeopleonourplanet.Secondistheabilitytorecordbrainactivity, whichcanbetracedbacktoHansBerger ’sworkontheelectroencephalogram(EEG)almost100yearsago.Theconjunctionoftheseapproacheshasgivenrisetoabrandnewfieldofresearch:thebrain-computerinterface(BCI).Itis traditionallythoughtthatthemainfunctionofthebrainisthatoftransformingsensoryinputintomotorandhormonal output.Tothis,wecannowaddthefactthatBCIutilizesnoveltypesofoutputfromthebraintomonitor,restore,or enhancethenaturalfunctioningofthecentralnervoussystem,includingitsthinking.Theemergenceofthistrulynew fieldofneurosciencepromptedustoproposeforthefirsttimeavolumeofthe HandbookofClinicalNeurology entirely dedicatedtoBCI.

Asexpected,thevolumecoversawidevarietyoftopics.ItopenswithtwochaptersdefiningBCIanditsprinciples. ThefollowingchaptersexplorethewaysthatBCIscanguiderehabilitationeffortsinconditionssuchasstrokesand spinalcordlesionsbyimprovingthecapacityofonlinemonitoringofbrainactivity.TheyshowhowBCIcansignificantlyimpactneurologicrehabilitation.OneofthemainpotentialapplicationsofBCIisinimprovingcommunications.Thisisillustratedmostsignificantlyinpatientswithlocked-insyndromeorwithslowlyprogressiveamyotrophic lateralsclerosis.Intheselatterpatients,BCIhelpscommunicationinend-of-lifecircumstances,whichisparamountin preservingpatientautonomyanddignity BCIsemploytheperson’sneuralsignalstoaidcommunicationinsteadof relyingonmuscleactivity.AchapterontraumapresentstheresultsofstudiesusingBCIinconsciouspatientswith traumaticbraininjuriesandinanimalmodelsofinjurytoshowthatBCIcanimprovecognitiveimpairmentsinboth animalmodelsandpatients.AchapterdedicatedtochronicneuropathicpainafterspinalcordinjuriesshowsthatBCI mayhaveasubstantialinfluenceoncorticaltopographicorganization.Anotherchapterdiscussestheuseofimagined movementsofparalyzedbodypartsandneurofeedbackforthepreventionortreatmentofchronicneuropathicpain. ThevolumeincludeschaptersdealingwithBCIapplicationstovirtualrealitydevicesandvideogames,andhowto monitortheperformanceofprofessionalandoccupationaloperators,forinstance,whiledriving.Techniquesthatare nowstandardsuchasEEGandfunctionalmagneticresonanceimagingarerevisited,showinghowtheycanbestbe usedinBCIresearchapplications.

Thefinalchaptersofthevolumedealwithimportantgeneralprinciples,specificallywithethicalaspectsofthese newtechniquesastheyentermedicalpractice.BCIcansatisfyseveralgoalsoftraditionalmedicine,suchashelping patientstolivewiththeirdisabilitiesandmaintaindignityandself-esteem.OtheraspectsofBCIareconsideredbut arenotentirelyresolved,forinstance,makingsurethatpatientscanmaintaincompleteprivacyorclarifyingthe decision-makingprocess.Thevolumeendswithareviewofindustrialperspectivesanditaddressesthetranslational gapconcerningtheknowledgeofhowtobringBCIsfromthelaboratorytothefield.Thereiscurrentlyalackofutility andaccessibilityofmanyBCIdevices;effortsareunderwaytoadoptuser-centereddesignsforBCIresearchand development.

Wehavebeenfortunatetohaveaseditorsofthisvolumetwodistinguishedscholars:NickF.Ramsey,BrainCenter, UniversityMedicalCenterUtrecht,Utrecht,theNetherlands,andJosedelR.Millán,CarolCockrellCurranEndowed Chair,DepartmentofElectricalandComputerEngineering&DepartmentofNeurology,UniversityofTexasatAustin, UnitedStates.Bothhavebeenattheforefrontofresearchinneuroscienceformanyyears.Theyhaveassembledatruly internationalgroupofauthorswithacknowledgedexpertisetoproducethisauthoritative,comprehensive,and up-to-datevolume.TheavailabilityofthevolumeelectronicallyonElsevier ’sScienceDirectsiteaswellasinprint formatshouldensureitsreadyaccessibilityandfacilitatesearchesforspecificinformation.

Wearegratefultothetwovolumeeditorsandtoallthecontributorsfortheireffortsincreatingsuchaninvaluable resource.Asserieseditorswereadandcommentedoneachofthechapterswithgreatinterestandareconfidentthat cliniciansandresearchersinmanydifferentdisciplineswillfindmuchinthisvolumetoappealtothem.

And,finally,wethankElsevier,ourpublisher,and,inparticular,MichaelParkinsoninScotland,NikkiLevyand KristiAndersoninSanDiego,andSujathaThirugnanaSambandamatElsevierGlobalBookProductioninChennaifor theirunfailingandexpertassistanceinthedevelopmentandproductionoftheseHCNvolumes.

MichaelJ.Aminoff

Franc ¸ oisBoller

DickF.Swaab

Preface Brain-computerinterface(BCI)technologyhasincreasinglyfounditswayintothenews.Largecompanies,including FacebookandNeuralink,havebecomeinterestedintheprospectofofferingtheircustomersawaytocommunicate withoutakeyboardandhavestartedtheirownresearchprogramsonBCI.Scientistsclaimthatbrainsignalscan beinterpretedwellenoughtocontrolroboticarmsandwheelchairs,andeventospeakthroughacomputer.Yet,as isoftenthecasewithnewfrontiersinscience,actualachievementsandwhattheymeanforpeopleandsocietyare difficulttoassess.TheBCIfieldisparticularlydifficulttoappraisebecausemultipledisciplinesareinvolved,andeach reportsonperformanceandutilityaccordingtoitsownstandards.TheeditorsofthisvolumehavebeeninvolvedinBCI researchandarewellpositionedintheBCIcommunityasleadersoftheinternationalBCISociety.Wefeltthatitisthe righttimefortheBCIcommunitytoinformcliniciansofthestateofaffairsinBCIresearch,andtogiveawell-informed impressionofwhatwecanexpecttoseeinclinicalcontextsincomingyears.

MostbooksonBCIaddressthetechnicalaspects,anddescriberesearchandperformanceinhealthyvolunteers. Indeed,applicationsthatbenefithealthypeoplewouldmarkasignificantstepintranslatingwhathasbeendiscovered inbrainresearch,toapplicationsforthecommunityatlarge.Interfacingwithcomputers,forinstance,couldextend beyondkeyboardsandvoicecontrol,perhapsincreasingthespeedofinteractionandliberatinghandsandspeech forotheractivities.Or,BCImayenhancesafetyintheoperationofmachineryandvehicles.Aroadmapcomposed fortheEuropeanUnionin2015bytheBCIcommunitydetailsthevariousdomainsthatstandtobenefitfromresearch anddevelopmentofBCIsystems.* Theauthorsenvisionedmultipleapplicationstomatureinthecomingyearsand formulated thisvisionasfollows:

In2025,awidearrayofapplicationswillusebrainsignalsasanimportantsourceofinformation.Wewillsee routineapplicationsinprofessionalcontext,personalhealthmonitoring,andmedicaltreatment.Weenvision afuturewherehumansandinformationtechnologyareseamlesslyandintuitivelyconnectedbyintegrating variousbiosignals,particularlybrainactivity.Peoplewillbesupportedinchoosingthebesttimeformaking difficultandimportantdecisions.Peopleworkinginsafety-relevantfieldswillbecapableofanticipating fatigue,andauthoritiesmayfindgood(evidence-based)reasonstoincorporatesuchapplicationsinregulations.Game,health,education,andlifestylecompanieswilllinkbrainandotherbiosignalswithuseful applicationsforabroadcommunity.Peoplewillwanttomonitortheirbrainstatestoprovidethemwithreliable estimatesoftheirmentalcapacityandperformancelevel.RehabilitationwillbenefitfromBCI-based treatmentsinthecomingyears.Strokerehabilitationwillbenefitfromplugandplayhomeuseofnon-invasive BCIsystems.Restorationoflostmotorfunctionswilllikelyrequirefullyimplantableneuralrecordingand stimulationdevices.Inthelongerrun,newtreatmentsofbraindisordersmayincludeelectroceuticals,where BCIsareusedtoprovidecorrectiveneurostimulationforepilepsy,depression,Parkinson’sdisease,andschizophrenia.RestorationofmobilityinpeoplewithparaplegiawillbeachievedwithBCI-basedlocomotion systems,wheredecodedbrainsignalseithercontrolanexoskeletonoractivatelimbmusclestimulation programsforwalking.

Sincepublicationofthisroadmap,severaldevelopmentshaveemergedthatstrengthenthisvision.Researchwith implantableBCIsystemsinpeoplewithsevereparalysishasincreaseddramatically,accompaniedbyasteepincrease inreportsinrespectedmedicaljournals.Separately,severallargecompanieshavestartedwell-fundedresearch programsonBCI,hopingtodevelopsolutionsforable-bodiedpeopletocommunicatefaster.Withthelarge

*RoadmapBNCI,2015. TheFutureinBrain/Neural-ComputerInteraction:Horizon2020.ISBN:978-3-85125-379-5,https://doi. org/10.3217/978-3-85125-379-5.

investmentsmadetodevelopBCIsystems,wecanexpectasteadyincreaseinpublicreportsonthetopic,and applicationsarelikelytoentertherecreationalandmedicalmarketsinthecomingdecade.

Inthecurrentvolume,theauthors,representingthefullspectrumoftheinternationalBCIcommunity,focus primarilyonmedicalapplications.MediacoverageofBCIapplicationshasmadeitdifficultforclinicianstoassess theutilityfortheirpatients,notablybecauseresearchfindingspublishedinscientificandmedicaljournalstendto berathertechnicalandevokeoverlypositiveinterpretationsbyreporters.Withthepresentin-depthcoverageofmedical applications,theeditorshopetoinformreaderswithamedicalbackgroundorinterestofthecurrentcapabilities, realisticpromises,challenges,andpitfallsofhumanBCIsolutions.SincemuchBCIresearchhasbeen,andstillis, conductedinhealthypopulations,researchoutsidethemedicalarenaislikelytoberelevantformedicalapplications also,leadingtheeditorstoincludethemostrelevantmaterialinthisvolume.Moreover,forreaderstofullyunderstand BCIanditsapplications,theprinciplesofmeasurementandanalysisofbrainsignalsdeserve,andreceive,attention. Finally,thevariousstakeholdersneedtoberecognizedandheard,especiallysinceBCIresearchtouchesupon unchartedterritoryintermsofethics,involvementof(andimpacton)projectedusers,andindustrialinvolvement. Theeditorshavecomposedthevolumewiththeseconsiderationsinmind.

ThefirsttwochaptersaddressthedefinitionsandprinciplesofBCIandformtheconceptualframeworkfortherest ofthevolume.Next,thevariousneurologicdisordersthatmaybenefitfromBCIaredetailed(Chapters3–6),followed by the typesofapplicationsthatarerelevantfordifferentdisorders(Chapters7–14).In Chapters15–17,theapplication of BCI tohealthypeopleandforresearchonbrainfunctionisexplained.Theprinciplesofvarioustypesofbrainsignals andmeasurementsareaddressedin Chapters18–23,includingprocessingofthesignalstoenableBCIinbothpatients and healthy volunteers.Thefinalchapters(Chapters24–26)addressethicalandindustrialconsiderationsandthe importance ofinvolvingtargetuserpopulations,especiallypatientsandpeoplewithdisabilities,fordevelopment ofBCIsystems.

ThetimelineofBCIresearchisofinterest.TheBCIfieldisamere50yearsold,withitsbeginningattributedto nonhumanprimatestudiesinthelate1960s.Monkeyswereatthattimeshowntobeabletoregulatefiringratesof singleneurons,usingfeedback.WhenEEGrecordingsystemsbecamewidelyavailableandelectricalrhythmswere showntorespondtobehavior(suchasthemagnitudeofthemurhythm,whichdeclinesduringmotoractions),arapidly increasingnumberofresearchteamsbecameengagedindevelopingtechnologiestoextractbrainsignalsforBCI.With increasingcomputingpower,machinelearningalgorithmsandcomplexsignalmodelsfoundtheirwayintothefield. Afteryearsofresearchwithnonhumanprimates,andseveralpioneeringinitiativesintheUnitedStates,peoplewith severeparalysiswereincludedinhumanBCIstudieswithelectrodesimplantedundertheskull.In2019,closeto 30peoplewereimplantedwithelectrodes(Chapters8and13)orcompletesystems(Chapter7),andthisnumber is increasing steadilyinanincreasingnumberofcountries.Asofyet,ahandfulofresearchteamshavesucceeded inbringingBCItechnologyintothehomesofparalyzedpeople,andtoenabletheuserstocommunicatewiththeir caregivers.Inparallel,internationalBCIcompetitionsinvolvingpeoplewithsevereparalysis,suchasCybathlon, arepowerfulvehiclestobringBCItechnologyoutsideofthelaboratoryandadvancethefield.Thesestudieshave generatedproofofprincipleofclinicalutilityofBCIandheraldedincreasedinstitutionalandindustrialeffortsto developimplantableandnoninvasivesystemsforcommercialexploitation.LargecompaniessuchasNeuralink, Kernel,andFacebookenteredthefraywithrecreationalapplicationsinmind.Thesewell-fundedindustrialactivities arelikelytogeneratetechnologiesthatcanalsosupportmedicalapplications.

Thisvolumeofferscliniciansandclinicalresearchersacomprehensiveperspectiveonthestateofaffairsinthefield ofBCIformedicalapplications.Thepitfalls,challenges,andpromisesareexplainedanddiscussed,allowingreadersto getasolidgraspofthetopicandtoassessprofessionalandpublicreportsonBCI.

NickF.Ramsey JosedelR.Millán

Contributors J.Annen

ComaScienceGroup,GIGA-Consciousness;Centredu Cerveau,UniversityHospitalofLiège,Liège,Belgium ComaScienceGroup,GIGA-Consciousness,University ofLiègeandUniversityHospitalofLiège,Liège, Belgium

P.Aricò

DepartmentofMolecularMedicine,SapienzaUniversity ofRome;Brainsignssrl,Rome,Italy

F.Babiloni

DepartmentofMolecularMedicine,SapienzaUniversity ofRome;Brainsignssrl,Rome,Italy

A.P.Batista

DepartmentofBioengineering,UniversityofPittsburgh, Pittsburgh,PA,UnitedStates

D.Bavelier

FacultyofPsychologyandEducationSciences;Campus Biotech,UniversityofGeneva,Geneva,Switzerland

G.Borghini

DepartmentofMolecularMedicine,SapienzaUniversity ofRome;Brainsignssrl,Rome,Italy

C.E.Bouton

CenterforBioelectronicMedicine,FeinsteinInstitutefor MedicalResearch,NorthwellHealth,Manhasset,NY, UnitedStates

T.Brandmeyer

OsherCenterforIntegrativeMedicine,University CaliforniaSanFrancisco(UCSF),SanFrancisco,CA, UnitedStates

C.Cannard

CentredeRechercheCerveauetCognition,PaulSabatier University,Toulouse,France;InstituteofNoetic Sciences,Petaluma,CA,UnitedStates

R.Chavarriaga

CenterforNeuroprosthetics, EcolePolytechnique FederaledeLausanne,Geneva;InstituteofApplied InformationTechnology(InIT),ZurichUniversityof AppliedSciencesZHAW,Winterthur,Switzerland

J.Collinger

DepartmentofBioengineering;DepartmentofPhysical MedicineandRehabilitation,UniversityofPittsburgh, Pittsburgh,PA,UnitedStates

V.Conde

DanishResearchCentreforMagneticResonance, CopenhagenUniversityHospitalHvidovre, Copenhagen,Denmark;ClinicalNeuroscience Laboratory,DepartmentofPsychology,Norwegian UniversityofScienceandTechnology,Trondheim, Norway

J.delR.Millán

DepartmentofElectricalandComputerEngineeringand DepartmentofNeurology,TheUniversityofTexasat Austin,Austin,TX,UnitedStates

A.Delorme

CentredeRechercheCerveauetCognition,PaulSabatier University,Toulouse,France;InstituteofNoetic Sciences,Petaluma;SwartzCenterforComputational Neuroscience,InstituteofNeuralComputation(INC), UniversityofCaliforniaSanDiego,SanDiego,CA, UnitedStates

T.J.Denison

MedtronicRTGImplantables,Minneapolis,MN, UnitedStates;MRCBrainNetworkDynamicsUnit, UniversityofOxford,Oxford,UnitedKingdom

G.DiFlumeri

DepartmentofMolecularMedicine,SapienzaUniversity ofRome;Brainsignssrl,Rome,Italy

R.Gaunt

DepartmentofBioengineering;DepartmentofPhysical MedicineandRehabilitation,UniversityofPittsburgh, Pittsburgh,PA,UnitedStates

R.Goebel

DepartmentofCognitiveNeuroscience,Maastricht University;MaastrichtBrainImagingCenter(M-BIC), Maastricht,TheNetherlands

O.Gosseries

ComaScienceGroup,GIGA-Consciousness;Centredu Cerveau,UniversityHospitalofLiège,Liège,Belgium ComaScienceGroup,GIGA-Consciousness,University ofLiègeandUniversityHospitalofLiège,Liège, Belgium

D.A.Heldman

GreatLakesNeuroTech,Cleveland,OH,UnitedStates

D.Hermes

DepartmentofPhysiology&BiomedicalEngineering, MayoClinic,Rochester,MN,UnitedStates;Department ofNeurology&Neurosurgery,UMCUtrechtBrain Center,UniversityMedicalCenter,Utrecht,The Netherlands

A.Herrera

DepartmentofBioengineering,UniversityofPittsburgh, Pittsburgh,PA,UnitedStates

L.R.Hochberg

SchoolofEngineeringandCarneyInstituteforBrain Science,BrownUniversity;CenterforNeurorestoration andNeurotechnology,VeteransAffairsMedicalCenter, Providence,RI;CenterforNeurotechnologyand Neurorecovery,MassachusettsGeneralHospital, HarvardMedicalSchool,Boston,MA,UnitedStates

C.Hughes

DepartmentofBioengineering,UniversityofPittsburgh, Pittsburgh,PA,UnitedStates

I.Iturrate

CenterforNeuroprosthetics, EcolePolytechnique FederaledeLausanne,Geneva,Switzerland

B.Jarosiewicz

BrainGate,BrownUniversity,Providence,RI, UnitedStates

S.Kleih

InstituteofPsychology,UniversityofWurzburg, Wurzburg,Germany

E.Klein

DepartmentofNeurology,OregonHealthandScience University,Portland,OR;DepartmentofPhilosophy, UniversityofWashington,Seattle,WA,UnitedStates

A.Kubler InstituteofPsychology,UniversityofWurzburg, W€ urzburg,Germany

S.Laureys

ComaScienceGroup,GIGA-Consciousness;Centredu Cerveau,UniversityHospitalofLiège,Liège,Belgium ComaScienceGroup,GIGA-Consciousness,University ofLiègeandUniversityHospitalofLiège,Liège, Belgium

R.Leeb MindMazeSA,Lausanne,Switzerland

M.Masciullo DepartmentofNeurorehabilitation,FondazioneSanta LuciaIRCCS,Rome,Italy

D.Mattia NeuroelectricalImagingandBrainComputerInterface Laboratory,FondazioneSantaLuciaIRCCS,Rome, Italy

K.J.Miller DepartmentofNeurosurgery,MayoClinic,Rochester, MN,UnitedStates

K.T.Mitchell DepartmentofNeurology,DukeUniversity,Durham, NC,UnitedStates

M.Molinari DepartmentofNeurorehabilitation,FondazioneSanta LuciaIRCCS,Rome,Italy

D.W.Moran BiomedicalEngineering,WashingtonUniversity, St.Louis,MO,UnitedStates

G.R.Muller-Putz InstituteforNeuralEngineering,LaboratoryofBrainComputerInterfaces,GrazUniversityofTechnology, Graz,Austria

M.Nahum

SchoolofOccupationalTherapy,FacultyofMedicine, HebrewUniversityofJerusalem,Jerusalem,Israel

F.Nijboer

FacultyofElectricalEngineering,Mathematicsand ComputerScience,UniversityofTwente,Enschede, TheNetherlands

D.Perez-Marcos MindMazeSA,Lausanne,Switzerland

F.Pichiorri

NeuroelectricalImagingandBrainComputerInterface Laboratory,FondazioneSantaLuciaIRCCS,Rome, Italy

C.L.Pulliam

MedtronicRTGImplantables,Minneapolis,MN, UnitedStates

N.F.Ramsey

BrainCenter,UniversityMedicalCenterUtrecht, Utrecht,TheNetherlands

V.Ronca

DepartmentofMolecularMedicine,SapienzaUniversity ofRome;Brainsignssrl,Rome,Italy

R.Rupp

ExperimentalNeurorehabilitation,SpinalCordInjury Center,HeidelbergUniversityHospital,Heidelberg, Germany

H.R.Siebner

DanishResearchCentreforMagneticResonance, CopenhagenUniversityHospitalHvidovre;Department ofNeurology,CopenhagenUniversityHospital Bispebjerg,Copenhagen,Denmark

B.Sorger DepartmentofCognitiveNeuroscience,Maastricht University;MaastrichtBrainImagingCenter(M-BIC), Maastricht,TheNetherlands

S.R.Stanslaski MedtronicRTGImplantables,Minneapolis,MN, UnitedStates

P.A.Starr DepartmentofNeurosurgery,UniversityofCalifornia, SanFrancisco,SanFrancisco,CA,UnitedStates

M.J.Vansteensel BrainCenter,UniversityMedicalCenterUtrecht, Utrecht,TheNetherlands

T.M.Vaughan NationalCenterforAdaptiveNeurotechnologies, WadsworthCenter,NewYorkStateDepartmentof Health,Albany,NY,UnitedStates

M.Vilela SchoolofEngineeringandCarneyInstituteforBrain Science,BrownUniversity,Providence,RI, UnitedStates

A.Vozzi DepartmentofMolecularMedicine,SapienzaUniversity ofRome;Brainsignssrl,Rome,Italy

H.Wahbeh InstituteofNoeticSciences,Petaluma,CA, UnitedStates

J.R.Wolpaw NationalCenterforAdaptiveNeurotechnologiesand StrattonVAMedicalCenter,WadsworthCenter,Albany, NY,UnitedStates

Foreword vii

Pref.tee ix

Contributors xi

1. Human brain function and brnin�omputcr interfaces

1 N.F. Ra11tsey {Utrecht. The Netherlands)

2. Brain-computer interfaces: Definitions nod priocip厄

15 J.R. iv.。/pall\ J. def R. Mil/011, and N.F. Ra1nsey {Albany and Austin, U11ited States; a,1d Utrecht, The Netherlands)

3. Stroke and potential benefits ofbrain-computer interface

25 M. Moliriari mid M. Masci11/lo {Rome, Italy)

4 B . p . f . ram-com uter mter aces for people with amyotropbic lateral 艾lerosis

33 T.M. Vaughan (Albany. U11i回Stat动

5. Brain damage by trauma

39 V. Cc11de皿d H.R. Sieb11er (Cope11l,age11, Denmarkand Tro,uJheim, Norwa_刃

6. Spinal cord lesions

51 R Rupp (Heidelberg. Ge11na11y)

7. Brain-computer interfaces for comn1unication

67 M.J. Va,,stee,isel a11d B.Ja,-osiewicz (U11动t, The Netherla11ds a11d Provide,1ce, U11ited States)

8. Applications of brain-computer interfaces to the control ofrobotic and prosthetic arms

87 M. V,/e/a a叫L.R. Hochberg (Providence a11d Bosto11, UnitedStates)

9. Brain-computer interfaces in ncurologic rehabilitation practice

101 F. Pichiorri QJld D. Mattia (Rome, Italy)

10. Video games as rich cn\'ironments to foster brain plasticity

117 M. Nahum and D. Bavelier (Jerusalem, Israeland Geneva, Switzer/a吵

11. Brain•computer interfaces forconsciousness assessment and communication in severely brain-injured pa ticnts

137 J. Anne,�S. la旷句s, and 0. Gwserics (Liege, Be/g/11111)

12, Smart ncuromodulation in movement disorders

153 K.T. Mitchell and P.A. Starr (Durham and San Francisco, United States)

13. Bidirectional brain-computer interfaces

163 C.Hugh邸, A.Her,切ra, R. Gaunt, and J. Co/linger (Pittsbw-gh, United States)

HandbookofClinicalNeurology, Vol.168(3rdseries)

Brain-ComputerInterfaces

N.F.RamseyandJ.delR.Millán,Editors

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-63934-9.00001-9

Copyright©2020ElsevierB.V.Allrightsreserved

Humanbrainfunctionandbrain-computerinterfaces NICKF.RAMSEY∗

BrainCenter,UniversityMedicalCenterUtrecht,Utrecht,TheNetherlands

Abstract

Humanbrainfunctionresearchhasevolveddramaticallyinthelastdecades.Inthischaptertheroleof modernmethodsofrecordingbrainactivityinunderstandinghumanbrainfunctionisexplained.Current knowledgeofbrainfunctionrelevanttobrain-computerinterface(BCI)researchisdetailed,withan emphasisonthemotorsystemwhichprovidesanexceptionallevelofdetailtodecodingofintendedor attemptedmovementsinparalyzedbeneficiariesofBCItechnologyandtranslationtocomputer-mediated actions.BCItechnologiesthatstandtobenefitthemostofthedetailedorganizationofthehumancortex are,andfortheforeseeablefuturearelikelytobe,reliantonintracranialelectrodes.Theseevolvingtechnologiesareexpectedtoenableseverelyparalyzedpeopletoregainthefacultyofmovementandspeechin thecomingdecades.

INTRODUCTION Withtheadventoftechniquestorecordandimage humanbrainfunction,hugestrideshavebeenmadein locatingfunction-specificbrainregionsandinterpreting theiractivity.Functionalmagneticresonanceimaging (fMRI)inparticularhasledtoincreasinglydetailed mapsoffunctions,withthelatestscannersoperatingat amagneticfieldof7Tandmakingsubmillimeterimagingpossible(Fracassoetal.,2018).Inthischapter I addressthevarioustechniquesusedcurrently,andin thepast,torelatebrainregionstospecificfunctions andbetterunderstandthehumanbrain.Ourunderstandingofhumanbrainfunctionisofparticularinterest forbrain-computerinterface(BCI)research,which standstobenefitfromusingthisknowledgeforoptimal decodingofneuralactivity.

BCIsstandtobenefitfromtheaccruedknowledge offunctionaltopography,andinparticularimplantable BCIsthatarestartingtomeetthedailyneedsofseverely paralyzedpeople(Vansteenseletal.,2016).Electroencephalography (EEG)(Chapter18)andfunctional near infrared spectroscopy(fNIRS)(Chapter21)carry

promise as noninvasivetechniques,buttheirinherent lowspatialresolutionpreventsthemfromcapitalizing onthedetailedtopographicalorganizationofthecortex. Giventhatthedetailedorganizationprovidesopportunitiestodiscriminatedetailedactionsandperceptions, suchasmovementofindividualfingersorperception ofdifferentauditoryinputs,intracranialBCIsolutions carrythemostsignificantpromisefortranslating intendedlimbmovementsandspeechtoactuatorssuch asroboticlimbsandsyntheticspeech,respectively. Peoplewhomaybenefitthemostfromcurrentdevelopmentsinthisareaareprimarilypeoplewithlocked-in syndrome(LIS)duetobrainstemstrokeoradegenerativemotorneurondiseasesuchasamyotrophiclateral sclerosis(ALS)(Chapter4),butwithmaturationof the technology,intracranialBCIsmaywellbecome attractiveforpeoplewithspinalcordlesion(Chapter6) or cerebralpalsy.

Animportantlimitationtothedevelopmentof fullyimplantableintracranialBCIsforhumansisthe hardware.Currently,systemsthatmaybeusedforBCI (e.g., Vansteenseletal.,2016)aredesignedforthe purpose of closed-loopbrainstimulationformovement

∗Correspondenceto:N.F.Ramsey,PhD,Heidelberglaan100,RoomG.03.130,Utrecht,3584CX,TheNetherlands. Tel:+31-88-755-6863,Email:n.f.ramsey @umcutrecht.nl

disorders(e.g.,Parkinson’sdisease)(Swannetal.,2018) orepilepsy (Skarpaasetal.,2019)andcontainonlyafew channels (amplifiers).Forfullexploitationofthedetailed braintopography,manymorechannelsarerequired,but intheabsenceofotherclinicalapplicationsthatwould justifythecostofhardwaredevelopment,thesedevices needtobedesignedforBCIspecifically.Sincethe BCIfieldisinitsinfancy,themarketsizeisunknown, whichplaceshighcommercialriskswithpotentialmanufacturers.Asaresult,suchdevicesarenotyetavailable. Nevertheless,researchontranslatingbrainactivityto specificactionswithmultiplechannelsisongoing,providingabasisfor(near)-futuremultichannelintracranial BCIsystems.

HISTORYOFLINKINGBRAINTO BEHAVIOR Thenotionthatthehumanbrainexhibitsamodularorganizationwasputforwardasearlyasthe17thcentury, whenWillisclaimedthatfunctionsoriginatedfrom thebrain(Finger,2005).Itwasnotuntiltheearly 19th centurythatresearchintotopographyofbrainfunctionstookholdintheresearcharena,whenphysicians triedtolinkspecificfunctionstolocationsontheskull. Althoughthisartofphrenology(Combe,1851)lacked the systematicorderinganddefinitionofbrainfunctions thatis,inmodernday,firmlyembeddedinrelated disciplines,itdidarguablyheraldthebeginningofbrain functionresearch.Theearly20thcenturywitnessedthe beginningofneuropsychology,whenitbecamepossible tostudypeoplewithspecificbrainlesionsdueinpart toadvancedweaponryinwar.Theinvestigationinto therelationshipbetweensuchlesionsandbehaviorled toincreasinglyrefinedmethodsformeasuringbehavior. ExamplesofpioneersincludeBrocaandWernicke (Broca,1865; Wernicke,1974).Inthe1930s,Penfield and colleagues initiatedthefieldofhumanbrainmappingwithdirectelectricalstimulation(ESM)ofthe cortexduringsurgery,adevelopmentthatmadeprogress intheareaofunderstandingbrainfunctionnolonger dependentonbrainlesions(PenfieldandBoldrey, 1937).Muchoftheirworkhasbeenthebasisofour understandingoflanguageandmotorfunction.ESMin awakepatientsiseventodayusedwidelyinneurosurgery todeterminewhereimportantfunctions,notablymovementandlanguage,thatneedtobesparedduringbrain tissueremovalforthetreatmentofpatientswithbrain tumorsorepilepsyarelocated.ESMcausesabrief sensationordisruptionoffunctioninsensoryandassociativecortex,avirtuallesionasitwere,andaslow musclecontractioninmotorcortex.Withtheadventof computers,inthe1960s,combinedwithEEGwhich wasdiscoveredinthe1920s(Berger,1931),functional

mapping no longerdependedonrealorvirtuallesions. Yetthedeeperbrainstructuresresisteddetectionof neuralelectricalsignals.Thiswasnolongeralimitation whenmethodssuchaspositronemissiontomography (PET)intheearly1980s,andfMRIin1992became availabletoimagebloodflow,andinparticular,changes inbloodflowfollowingexecutionofspecifictasks (Ogawaetal.,1992).Thelatterrapidlybecameapreferred instrumentformappingbrainfunctions,inpart becauseMRIscannersprovedtobeveryusefulin radiologyand,asaresult,becamewidelyavailable. Twomoretechniquesfoundtheirwaytohumanresearch: single-cellrecordingswithmicroelectrodesandelectrocorticography(ECoG)withdiscelectrodesembeddedin asiliconsheetforcorticalsurfacerecordings.

Inthischapter,anoverviewisgivenofhowthe describedtechniquesimprovedourunderstandingof thecorticalsubstrateofhumanbehavior.Whatwenow knowabouttheorganizationofbrainfunctionsdirectly affectsBCIresearchnotonlyinunderstandingmechanismsbutalsointhedesignofaBCIsystem.

MEASUREMENTOFBRAINFUNCTIONS Brainfunctionexperimentscanbedividedinto(virtual) lesionstudiesandimagingstudies.Forlesionstudies, emphasisliesondescribingthedirectbehavioralconsequenceindetailsoastodistinguishfromindirectconsequences.Oneexampleisinabilitytospeak,whichcould resultfrominabilitytoactivatemuscles,tocomprehend, ortoformulatewords,eachofwhichinvolvesadifferent, albeitmutuallyconnected,brainregion.Thechallengein lesionstudiesistonarrowdownthebehavioralmeasure andtherebyreducethenumberofindirectlyrelatedbrain regionsinordertomapfunctiontoanatomy.Imaging studiesrequireahighdegreeofselectivityinthefunction thatisevoked,andtheydosobydesigningtasks(called “paradigms”)forparticipants.Mostoften,paradigms consistoftwotasksthatareadministeredinanalternatingscheme.Onetaskisdesignedtoactivatebrainregions thataredirectlyrelatedtothefunctionofinterestbutwill inevitablyalsoactivateregionsthatarenot,suchasthose involvedinseeingtheinstructionsorpressingaresponse button.Todistinguishdirectfromindirectregions,a secondtaskisdesignedtoengageonlythelatterregions. Theparticipantperformstheparadigmwhileimage dataareacquiredcontinuously,generatingaseriesof dataframes.Insubsequentanalyses,eachpartofthe brain(channelsorbraintissuevolumeelementscalled “voxels”)istestedforitsresponsivenesstothealternatingtask.Onlythoseregionsthatresponddifferentlyto thetasksareconceptuallyrelatedtothefunctionof interestsinceallotherregionseitherdonotrespondat allorrespondtobothtasksinthesameway.

Severaldifficultchallengesinlinkingbrainregionsto specificfunctionslimitthestrengthofevidenceofbrain functionexperiments.Forone,theclassicalviewofthe brainasbeingorganizedmodularly,withspecificregions beingresponsibleforspecificfunctionsandthereby allowingformappingoneontotheother,isflawed.It isnowrecognizedthatnetworksunderliefunctions,with feedforward,feedback,andmodulatingconnections. Accordingly,itisnotpossibletoidentifyallthenetwork nodes(regions)becauselevelsofdetectableactivityare continuousratherthandiscrete(onvsoff).Moreover, regionsmayactivateatdifferentpointsintimeduring executionofatask,suchasgeneratingandspeakinga word,andmayactivatetoobrieflytodetect.Asimaging techniquesbecomebetteratmeasuringinmoredetailand faster,improvingspatialandtemporalresolution,the complexityofbrainfunctionsintermsofunderlyingneuronalmechanismsisbecomingmoreevident.Another dilemmaisthatlesionandimagingstudiesoftendo notagree.Thedominantexplanationisthatwhereas lesionstudiesidentifyregionsthatareindispensable forafunction,imagingstudiesidentifyadditional regionsthatplayarolebutarenotindispensable.For instance,fMRImapsoflanguageinpatientsplanned forsurgerytypicallydisplaytwiceasmanyregionsas subsequentlyfoundduringESM(Ruttenetal.,2002).

The concept ofneuralnetworkssupportingfunctions accommodatesthisphenomenon,inthatnetworkscan consistofbothcentralnodesthatactasbottleneckfor informationtransfer(acommontermforneurons influencingeachotherbymeansofactionpotentials) andperipheralnodesalongparallelpathways(Oliveira et al., 2017).Theformerareindispensablewhereasthe latter constituteredundancyinprocessinginformation. Redundancymostlikelyexiststoimprovebothperformancebysimultaneouslyprocessinginformationin differentwaysandresiliencetotissuedamageordysfunction(Oliveiraetal.,2017).Athirdchallengeis spatial resolution.Asimagingbecomesbetteratmeasuringindetail,thedenseinterconnectednessofthecortex requiresustorethinkfunctionaltopography.

Virtuallesiontechniquesarecurrentlysparselyused forresearch.ESMisusedmainlyduringsurgeryin awakepatientsforclinicalpurposestoidentifybothgray andwhitemattertobespared(Ritaccioetal.,2018). Recording exactlocationsofstimulationformapping researchisrarelydoneduetotheworkflowandtime constraints.ESMisalsoperformedinECoGpatients whospend1–2weekswiththeimplantfordiagnostic purposes.ItisperformedthroughtheECoGelectrodes, allowingfordetermininglocationsofelectrodes(onpresurgicalMRI)andthusforlinkingfunctiontolocationin asystematicmanner.Usingthisprocedure,comparisons canbemadebetweenneuralactivityandeffectsof

stimulationinthesameelectrodes(Baueretal.,2013). Transcranialmagneticstimulation(TMS)isanoninvasivetechniqueforperturbingbrainfunction(ValeroCabre et al.,2017).Effectsofbriefmagneticpulsesor trains of pulsesonongoingactivityofasubjectcanbe quitelocalized,dependingonthestimulationcoilused. Formappingofthemotorcortex,TMShasshownsimilar resultsasESM,and(toalesserdegree)asmagnetoencephalography(MEG,seefollowingparagraphs) (Taraporeetal.,2012).

Electricalrecording Recentdecadeshaveseenasurgeinnoninvasiveimagingtechniques.ApartfromEEG,whereincreasing numbersofelectrodesareusedtoincreasesensitivity andarguablyspatialresolution,MEGcanbeusedtoinfer electricalactivity(Baillet,2017).Itdoessobyrecording the electrom agneticcorrelateofcurrentsinthebrain.By this,giventheorthogonalorientationofelectricaland magneticfields,EEGandMEGcanberegardedascorrelatedbutcomplimentarymodalities.MEGishardly affectedbytheinsulatingpropertiesofboneandtissue and,assuch,isbetteratlocalizingcurrentsourcesthan EEG.This,however,comesatthepriceofsensitivity becausethemagneticfieldsgeneratedbybrainactivity areweak.Specificneuralevents,generallyinvokedwith specificparadigms,canbecharacterizedinspaceand time.SpatialresolutionislimitedforEEGandMEGto centimeter,anddecreaseswithdistancetothesensors duetoarapiddecreaseofsignalstrength(signaldrops withdistancesquaredorcubed).Temporalresolution isquitehighsincetheelectricalpotentialsvaryrapidly withbrainactivity.Eventscanbedeterminedintime uptotensofmillisecondsaccurately,allowingfor sequencingpotentialstodescribeaneventsuchasthe positivepotentialpeakaround300msafterstimuluspresentation(P300,see Chapter18).Sincethesensorsare relatively far awayfromneuraltissue,theysamplefrom largevolumesoftissueand,assuch,recordcoherent electricaleventsacrosscentimetersofcortex.Although isolatedactivityofasmallpatchofseveralmillimeters couldconceptuallybedetected,theactualresolution remainsintheorderofcentimetersbecausesurrounding tissueisalsoactiveanddilutestheisolatedsignal.

Toincreasespatialresolution,sensorsneedtobe closertothebrain.Thiscanbeachievedbysurgically positioningelectrodesonthesurfaceof,ordeepinside, thebrain.ECoGisclinicallyusedinpatientswith intractableepilepsywhenthesourceofseizuresand thelocationoftheeloquentcortex(brainareasrequired forprimarysensory,motor,andlanguagefunction) needstobedeterminedaccurately(andEEGdoesnot providesufficientinformation)(Keeneetal.,2000).

Thestandardelectrodegridsconsistoftwosandwiched siliconsheetswithsmallsteelorplatinumdiscs(2–4mm diameterspaced1cmapart)inbetween.Theelectrodes recorddirectlyfromthecorticalsurfacethroughholes punchedinthebrain-facingsiliconsheetandcoverthe partofthecortexthatissuspectedtoharbortheseizure source(s).Depthelectrodeshaveasimilarsurfaceper electrode,butheretheyconsistofringsalongasilicon wireofabout1mmthickandareusedwhensources aresuspectedtobelocatedinsubcorticalstructures. Intracraniallyrecordedsignalsarequitedifferentfrom EEGbecauserecordingsaredominatedbysignalgeneratedbytheneuraltissueimmediatelyunderneathor aroundtheelectrodes,andmoreremotesourcesbarely contributeduetotherapidsignaldrop(sameprinciple asEEG).Clinicalgrids,duetotheir1cmspacing,record onlyfrom4%oftissueunderneath,butgridsusedfor research,withspacingof3mm(smallestpossiblefor traditionalmanufacturing),capturemoreofthedetailed topographicalorganizationof,forexample,sensoryand motorcortices.Smallerspacingispossiblebutsuchgrids requirenewmanufacturingtechniques,whichareslow toobtainregulatoryapprovalforhumanuse.Depthelectrodemeasurefromdistributedpatchesofdeepbrain structureandarelocatedonthebasisofdiagnosticneeds and,assuch,arelessinformativeformappingfunctions incorticaldetail.

Recordingsatthelevelofsingleneuronscapturethe mostdetailbutrequireindwellingmicroelectrodeelectrodes.Microelectrodearraysareavailableforhuman use(Blackrockarrays)withabout100electrodesona 4mmby4mmcorticalpatch(Chapter8).Sinceeach electrode canrecordseveralneurons,thisarraycaptures activityfromseveralhundredsofneurons.

Sizeanddistanceofelectrodesfromneuraltissue affectssignalfeatures,mainlyduetoaveragingacross neurons.Whereasmicroelectrodearrayscandetect actionpotentialsor “spikes,” ECoGsamplesfromseveralhundredthousandneuronsandEEGfrom10million ormore.Thefrequencycontentdiffersaccordingly,with thepowerofhighfrequenciesdroppingwithnumberof recordedneurons.Frequencymattersinelectrophysiologysincebandsarethoughttorepresentdifferentpropertiesofcorticaltissue.Lowerfrequenciesuptoabout 30Hz,thedominantfeaturesofEEG,representmodulatingoscillationsoriginatingfrombasalstructures(notably thethalamus),whicharethoughttoregulatecortical excitability(Milleretal.,2012).Between30Hzand about 200 Hz,arangecapturedwellwithECoG,there arenoclearfrequenciespresent,exceptforspecific stimulusmanipulations(Hermesetal.,2015),butthe power averagedacrossthefrequencyrangerepresents localizedneuralactivity.This “high-frequencyband” (HFB)signalcorrelateswithfiringratesofpyramidal

cellsmeasuredwithindwellingelectrodes,buttheunderlyingmechanismisthoughttocorrelatewithdendritic membranepotentials(Milleretal.,2012; Chapter19). HFB signalaccordinglyreflectsnotonlyfiringratebut alsointracorticalactivity.Frequenciesintheorderof 1000Hzanduprepresentactionpotentialsgenerated bypyramidalcells.

Cerebrovascularrecording Thehumanbrainpossessesahighlyregulatedvascular supplysystem.Asimagingmethodsbecomemore detailedandaccurate,itisbecomingclearthatblood supplyiscloselytitratedtolocalmetabolicdemand,a principlecalledneurovascularcoupling.Asaconsequenceofthiscoupling,imagingbloodflowwhilea participantisperformingaparadigmallowsonetoobtain arepresentationofassociatedneuralactivitychanges. Bloodflowchangesonlyatandnearcorticaltissuethat isactivatedbythetask.

fMRIisthemostwidelyusedtechniquetomapbrain activity,anddoessowithincreasingdetail.Studieswith MRIscannersthatoperateatamagneticfieldstrengthof 7Teslahaveshownthatbloodflowchangescanbe confinedtosubmillimeter-sizedvoxels,confirmingtight neurovascularcoupling(Fracassoetal.,2018).Images acquired at lowerresolutions,suchas3–4mmat3T, aremoresensitivetoconfoundingvascularproperties relatedtosupplyinganddrainingvessels,whichcause someblurringoftheresultingactivitymaps.fMRIutilizesthedifferentmagneticpropertiesofoxygenated anddeoxygenatedhemoglobin(Glover,2011).Whereas the forme rdoesnotaffectthesurroundingmagnetic field(imposedbythescanner),thelattercausesasmall disturbancethatreducesthesignalrecorded.Sinceneural activityinducesalocalincreaseinoxygendemand,the localconcentrationofdeoxyhemoglobinincreases brieflyandthesignaldecreasesslightly.However,the arterialsupplyandbloodflowrapidlyincrease,causing drainageofthedeoxyhemoglobin,whichinturncauses thesignaltoincrease.Thisincreaseexceedsthesignal presentwhenthelocaltissueisatrest(baselinedeoxyhemoglobinconcentration),resultinginanactivity-related increaseinMRIsignal.Ofnote,asingleneuralevent canbedetectedthroughbloodflow,butsincethevascularresponsetoachangeinmetabolicdemandstartsto riseafter2sandtakes15stofullyreturntobaseline, fMRIcannotdistinguisheventsthatfolloweachother withinabout1s,althoughsometypesofanalyses suggestshortertimescanbedistinguishedwithspecific paradigms(Menonetal.,1998).

fNIRS likewiseutilizesthemetaboliceffecton oxy-anddeoxyhemoglobinconcentrationbutdoes sobypassinginfraredlightthroughthecortex

(VillringerandChance,1997; FranceschiniandBoas, 2004).Thiscanbedonenoninvasivelyduetothefact thatinfraredlightpassesthoughscalpandskullsufficientlytoreachcorticaltissue,andcanbedetectedupon exit(throughskullandscalp).Thetwostatesofhemoglobinabsorbdifferentinfraredfrequenciescausinga slightdropindetectedintensitywheneitherchanges. fNIRScarriesthebenefitofbeingportableandaffordable,butitsuffersfromlowspatialresolution,small signalchanges,andalimitedrangeofcorticalaccess (intheorderof1–2cmfromtheskull).

PETtracesradioactivitythatisattachedtomolecules ortracers(CherryandPhelps,2002).Apartfrom themanyreceptortracers,watercanbelabeledwith oxygen-15,aradioactivecompoundwitharapiddecay time(half-life2min).Whenlabeledwaterisbrought intothebloodstream,itpassesthroughthebrainwhere almostallofitisexchangedwithwaterinthetissue. Sincemorewaterisexchangedwheremetabolicdemand ishigh,theresultingimagesprovideamapofactivity muchlikefMRI,albeitwithamuchlongeracquisition time.Asingleimagetakesabout1minwithPET, whereasfMRIrequiresonlyasecondortwo.Water PETisrarelyusedforbrainactivityresearch,being replacedbyfMRIforavarietyofreasonsincluding affordability,wideavailability,lackofradioactive compounds,andfasterimageacquisition.

Howdoimagingtechniquescompare? Thedifferentbrainimagingtechniqueshavebeencomparedtoeachotherintryingtobetterunderstandthe natureandsourcesofacquiredsignals.Comparison makesmostsenseifthecomparedtechniquesmeasure atsimilarspatialresolutionsandthusmeasurethesame volumeofcorticaltissue.Comparisonsacrossdifferent resolutionsaredifficulttointerpretgiventhefactthat theyarelikelytomeasuredifferentphenomenasuchas describedforEEGversusECoG.Nevertheless,studies havebeenconductedtocomparefMRItoEEG(with

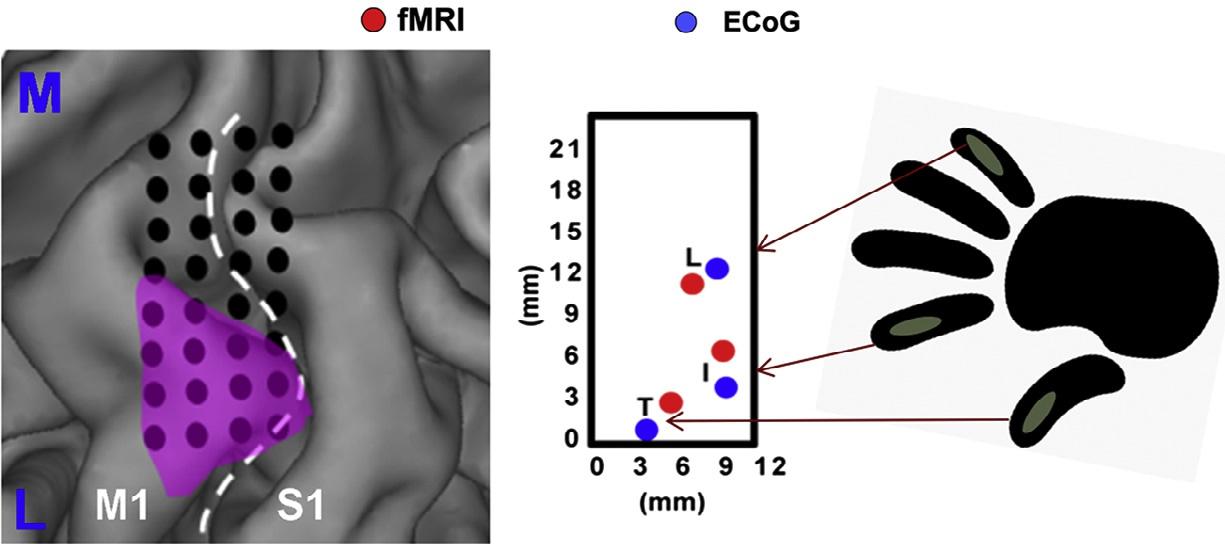

limitedspatialdetail),andtheygenerallyrevealanegativecorrelationbetweenfMRIandlowfrequencyoscillationssuchasthe a (8–12Hz)(Laufsetal.,2003), b (12–30Hz)(Ritteretal.,2009),and y ranges(3–7Hz) (Scheeringaetal.,2008).ComparisonsbetweenfMRI andECoGhaveshownsignificantagreementinspatial terms,especiallyfor7TMRI.Inastudyby Sieroetal. (2014),twoepilepsypatientsplannedforanECoG procedurewerescannedat7Tduringperformanceofa paradigmwheretheymovedthumb,index,andlittlefingersseparately.Duringsurgery,eachhadahigh-density gridplacedoverthesensorimotorhandregionwithelectrodesspaced3mmapart.Intheweekofdiagnosticprocedures,theyperformedthesametask,andthechanges inHFBpowerweremappedonthegrid.Theresulting ECoGactivitypatternwasthencomparedtothe7T fMRIresults,whichhadaresolutionof1.6mm,after coregistrationofgridandfMRIonthesameanatomical scan(Hermesetal.,2010).Thestudyrevealedtwofindings.First,thecentersofactivityforthethreefingers werelocatedwithinapatchof1cm2 onthemotorhand knob(Fig.1.1),confirmingtheexistenceofhandtopography.Second,thecentersforfMRIandECoGwereless than3mmawayfromeachother,whichconfirmsthe correlationbetweenHFBpowerandfMRIsignal.In anotherstudy,Hermes(Hermesetal.,2012)alsocomparedfMRI(at3T)toECoGandfoundthattheamplitudesofsignalchangesinthehandregionduringa simplefingertappingparadigmweresignificantlycorrelatedforthehigh-frequencybandbutmuchlesssoforthe 12–30Hzoscillations.AgreementsbetweenHFBand fMRIhavealsobeenreportedinseveralstudiesaddressingdifferentbrainfunctionssuchasmotionperception (Gaglianeseetal.,2017),workingmemory(Ramsey etal.,2006; Vansteenseletal.,2010),andaudiovisual processing(Haufeetal.,2018).Yetnotallstudiesfind highagreements,indicatingthatinsomebrainregions therelationshipisnotasstraightforward(Ojemann etal.,2013).Highcorrelationshavealsobeenfound betweenfMRIandlocalfieldpotentialsrecordedwith

indwellingmicroelectrodeelectrodes(Mukameletal., 2005; Niretal.,2007).Localfieldpotentials,likeECoG, measure fluctuationsofelectricalpotentialsurrounding theindwellingelectrodes(Chapters19 and 20).Ofnote, in animalresearch, Logothetis(2003) elegantlyshowed that the fMRIsignalcorrelatesbestwithincoming signalsandlocalprocessing(localfieldpotentials measuredwithindwellingmicroelectrodeelectrodes) asopposedtooutgoingactionpotentials,afindingthat resonateswiththenotionthatECoGalsodetectslocal processing(Milleretal.,2012)and,thereforecorrelates, well withfMRI.

FUNCTIONALORGANIZATION Thelastseveraldecadeshaveprovidedawealthof knowledgeaboutthefunctionalorganizationofthe humancortex,withtheadventofaccessibleMRI scannersandstudieswithECoGinepilepsypatients. YearsofresearchwithfMRIinhealthyvolunteers increasedinterestinfunctionalatlases,buildingonearlieratlasesmadeonthebasisofcytoarchitecturesuch asBrodmann(Brodmann,1908; Loukasetal.,2011) and coordinatesystemssuchastheonedevelopedby Talairach(TalairachandTournoux,1988).Withsoftware for processing MRIimagesbecomingavailable(Cox, 1996; Ashburner,2012; Jenkinsonetal.,2012),and the adoption ofacommonanatomicalreferenceframe (astandardanatomicalimageaveragedacrossmany healthyvolunteerssuchasonefromtheMontrealNeurologicalInstitute),itbecamepossibletoprojectastandard atlastoanindividualbrain.Thenewatlasesaredefinedon thecommonanatomicalreferencebrain,basedmainlyon cytoarchitectureandspatio-anatomicalborders(sulciand gyri)orfMRI,andcanbeprojectedontoanindividual brainafterwarpingonetotheother(Tzourio-Mazoyer et al.,2002; Mandaletal.,2012; Jamesetal.,2016).

Connections betweenregionsareinvestigatedby mappingfibertractsusingdiffusiontensorimaging andcorrelatedactivitybetweenregionsusingfMRI(resting-statefMRI).Thelatterinparticularledtoidentificationofmultiplelarge-scalenetworksbasedonfunctional connectivity,withawidearrayofanalyticalapproaches (Leeetal.,2013; Smithaetal.,2017).Thiswaslateralso applied toECoG,wherethehightemporalresolution allowedfordeterminingdirectionofinformationflow betweenregions(Korzeniewskaetal.,2008; Wang et al., 2014).Althoughquiteinterestingfromascientific pointof view,large-scalenetworkinformationisnotyet exploitedinBCIresearch,giventhatthemostprogressis beingmadewithimplantedelectrodearraysorgridsthat coveronlyconstrainedcorticalregions(sincetheyare placedformedicaldiagnosticreasons).However,recent worksuggeststhatconnectivitycanalsobeobserved

withinspecificbrainregionssuchasthevisualcortex (Raemaekersetal.,2014),whichcouldbeusefulfor decoding methods.

Inwhatfollows,thebrainfunctionsandcorrespondingbrainregionsarediscussedthatarerelevantforBCI.

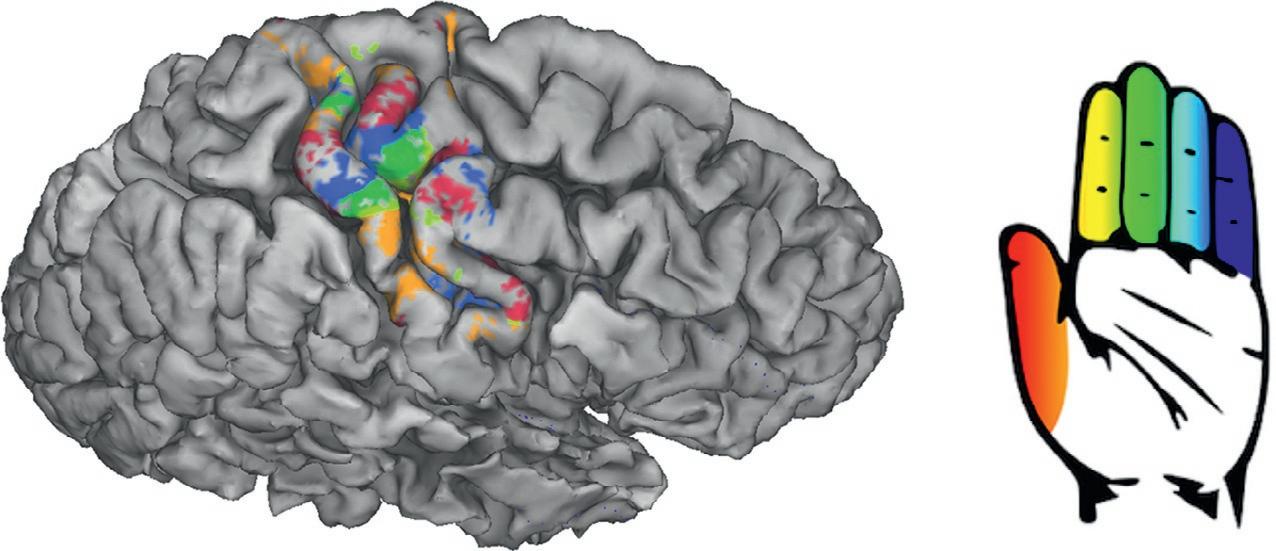

Motorcortex ThefirstfunctionofrelevanceformostBCIapplications isthemotorcortex.Movementisindispensableforinteractingwiththeoutsideworldandforcommunicating one’sdesires,ideas,andneeds.Allthoseareexpressed viathemotorcortex,whethertheyconcernreaching andgraspingorspeaking.Themotorcortexexhibitsa well-describedrelationshipwithbodyparts,asfirst describedby PenfieldandBoldrey(1937).Detailsof the hand weremappedwithinthehandregionofthe motorcortexwithfMRI(Kleinschmidtetal.,1997; Olmanetal.,2012)andECoG(Milleretal.,2009), and a combined7TfMRI–ECoGstudysubsequently showedthatallfingersarerepresentedinacorticalpatch of1–2cm(Sieroetal.,2014).Detectingindividual fingers is, however,notstraightforwardasthereissignificantoverlapinactivityacrossfingers.Thiswasrecently capturedbyusingananalyticalmethodfromvision researchcalledthepopulationreceptivefield(PrF) method(DumoulinandWandell,2008)thattakesinto account the possibilitythateachdetailedpatchofcortex canrespondtomultiplestimulisuchasadjacentpositions ofadiscretelightsourceinthevisualfieldoradjacent fingersofthehand.Eachstimulusactivatesaparticular focusinacorticalregion,butadjacentstimulialsoactivatethisfocusalbeitlessstrongly.ForPrFmappingin eachfocus(voxel)aGaussiandistributionofresponses acrossstimuliiscomputed.Thevoxelisthenassigned tothestimulusitrespondsstrongestto.Howstronglya voxelrespondstoadjacentstimuliiscapturedasthe widthoftheGaussiandistribution.Awidedistribution meansavoxelrespondstoawiderangeofadjacentstimuli,andanarrowdistributionmeansitrespondsonlyto immediatelyadjacentstimuli.UsingPrF,Schellekens etal.showedaclearsomatotopicorganizationofthe fingers(Schellekensetal.,2018),ascanbeseenin Fig.1.2,whichpersistsintotheprimarysomatosensory cortex. A plausibleexplanationoffocirespondingto multiplefingersisthateachfingeractivatesthefociof allotherfingers,eitherdirectlyorindirectlyvialateral connections,toinformthemofplannedandexecuted movements.Giventhatallfingersessentiallyalways operatetogether,passingoninformationaboutindividualfingermovementislikelytobenefitmanualdexterity.

ApartfromtheclearBCIapplicationofrecordingindividualfingersforcontrolofaroboticarm,useofhand areasignalshasbeeninvestigatedforcommunication.

Fig.1.2. PrFmapofthe lefthand obtainedwith7TfMRIinahealthyvolunteer.Each color indicatesthepreferredresponsefora particularfingerindicatedonthe right (Schellekensetal.,2018).

BleichnershowedthatfourhandgesturesoftheAmerican SignLanguagethatrepresentlettersofthealphabetcould bedecodedwith7TfMRIfromsensorimotorcortex,with anaccuracyof63%atachancelevelof25%,usingactivitypatternanalysis(Bleichneretal.,2014).Subsequent researchwithhigh-densityECoGincreaseddecodingto 85%(Bleichneretal.,2016; Brancoetal.,2017).Bruurmijnreplicatedthe7Tresultswithsixgestures,achieving almost75%correctdecoding(Bruurmijnetal.,2017)in healthyvolunteers.Inthesamestudy,agroupofaboveelbowamputeeswasalsoincludedtoassessfeasibilityof decodingattemptedgestures(asaproxyforparalysis)in theabsenceofmovementandsomatosensoryfeedback. Decodingperformancewas64%,andfurtheranalysis showedthatthesomatotopicdistributionofthehand wasunaffected.TheseresultssuggestthatattemptedgesturesmaybedecodableinpeoplewithLISforspelling. Decodingofhandmovementsmayfurtherimproveonce theexactrelationshipbetweensensorimotorcortex,individualmuscles(kinetics),andgestures(kinematics)is betterunderstood.Branco,inareviewoftheseissues, concludedthatmultiplekineticandkinematicparameters mapontosensorimotoractivityandrecommendedtaking theseintoaccountincontrolmodelstoimprovedecoding forBCI(Brancoetal.,2019).

Somatotopyofthemotorcortexextendstotheface area,althoughlessobviousthanthehandarea.Asrecent as2013,articulatorsincludingtongue,lips,jaw,and larynxwereforthefirsttimemappedusinghigh-density ECoGgrids(Bouchardetal.,2013).Directclassification ofthefourarticulatorswaslatershownwithfMRI (Bleichneretal.,2015).Severalgroupsutilizedtheconceptofsomatotopytodecodeelementsofspeech,with highdensityECoGfromthefaceareaortheinferior sensorimotorcortex.HerefMRIdoesnotperformwell atdiscriminatingspeechelements(datanotpublished), whichmaywellbeduetothelowtemporalresolutionin thatthevascularresponseistooslowforfMRItodetect individual,rapidlysequenced,articulatormovement

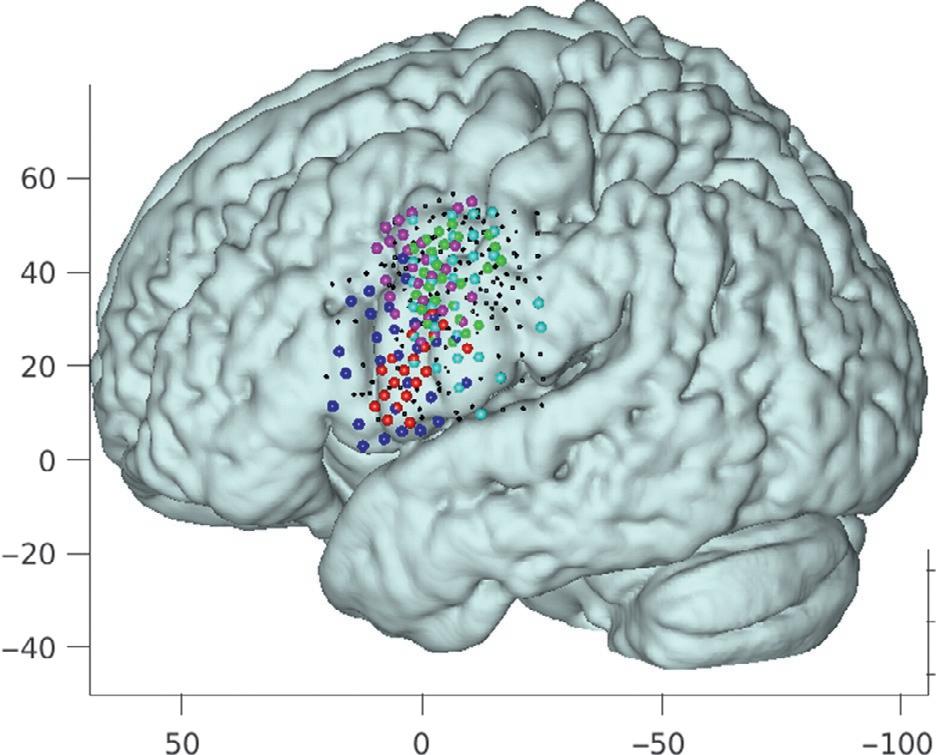

Fig.1.3. ElectrodesrecordinganHFBactivityresponseinthe sensorimotorfaceareaduringproductionofphonemes. Colors indicateeachoffiveparticipants(epilepsypatients). Black and coloreddots representelectrodes(allhigh-densityECoGgrids) inMNIspace(projectedontoanaverageof12normalbrains) (Ramseyetal.,2018).

fromthearticulationofphonemes,syllables,orwords. ECoGstudiesusingbothspatialandtemporalinformationhaverevealeditispossibletodistinguishphonemes (Mugleretal.,2018; Ramseyetal.,2018)fromtheface area(see Fig.1.3).Asingesturedecoding,decoding (attempted)speechfromthefaceareamaybenefit frombetterunderstandingoftherelationshipbetween articulatormovementsandcorticalactivity.Salari,for instance,reportedthattheHFBresponseinthefacearea duringpronunciationofasinglephonemeisaffectedby previousphonemes,timebetweensequentialphonemes, anddurationofpronunciation(Salarietal.,2018a,b, 2019),suggestingthatmodelsoftheneuralresponses maybenefitaccuracyofdecodingspeech.Decoding of “attempted” speechinpeoplewithLISiscurrentlyan attractiveapproachforcommunicationBCI(Mesgarani etal.,2014; Martinetal.,2016; Mugleretal.,2018; Anumanchipallietal.,2019).

Somatosensorycortex Muchliketheprimarymotorcortex,theprimarysomatosensorycortexexhibitsdetailedsomatotopy.Individual digitscanbediscriminated(Kolasinskietal.,2016), and even alongthephalangesofasinglefingerexhibit topographicaldistinction(Sanchez-Panchueloetal., 2012).Importantly,inthelatter,multiplefociwere observed similartoreportsforauditory(Formisano et al., 2003)andvisualcortex(ArcaroandKastner, 2015).Thesomatosensorycortexrespondstoexternal input, butitalsoactivatesaheadofplannedmovements, reflectingfeed-forwardactivationfrommotorplanning areas,aswasalsoshownbyBruurmijninthestudy withamputees(Bruurmijnetal.,2017).Somatotopyin humans hasbeenfurtherinvestigatedwithindwelling electrodearrays,whichshowedlimbandfingerspecific responsesuponstimulationofsingleelectrodesinprimarysomatosensorycortex(Flesheretal.,2016).As descri bed in Chapter13,decodingsensoryfeedbackis of great interestforcontrolofaroboticarm.

Visualcortex ThevisualcortexhasbeenatargetforEEG-basedBCI, whereaparticularpropertyofthevisualcortexisutilized. Whengazingataflickeringlight,thecortexrespondsby activatingatthesamerate,andthiscanbedetectedwith scalpEEG(Muller etal.,1998). Thesteadystatevisual evokedpotentialcanbeusedtodeterminetowhichof severalpositionsofthevisualfieldthesubjectisattendingto,byplacingflashinglightsofdifferentfrequencies inthosepositions(Allisonetal.,2008).Thefrequency recorded fromthescalpindicatesthepositionthatwas attendedto.Thevisualcortexcanalsobeusedtodetect visuospatialattentiondirectly.Anderssonsucceededin decodingdirectionofvisualattentionwithgazefixed atthecenterofthevisualfieldwith7TfMRIinrealtime (Anderssonetal.,2011)andshowedthatdecodingwas also feasible withonlyvoxelsatthesurfaceofthebrain thatcanbeaccessedwithECoGgrids(Anderssonetal., 2013b).DirectproofofapplicabilityforBCIwasprovided by havingsubjectsnavigatearobotinrealtime (inanotherroomwithcamerafeedbacktothesubject) whileintheMRIscanner(Anderssonetal.,2013a). The robot wascontrolledbyattendingtotheleftorright ofascreentorotatetherobotandtothetoptomakeit moveforward.Subjectssucceededindirectingtherobot alonganindicatedtrajectory,indicatingfeasibilityof movingawheelchairinBCIapplicationsbysimply attendingtothedesireddirectionofmotion.Similar resultswereobtainedwithEEGandtwodirectionsof covertattention(Toninetal.,2013)andEEGcombining covert attentiontospatial,color,andshapefeaturesof itemstobeselectedonascreen(Trederetal.,2011).With

a different approach, Sendenetal.(2019) succeededin distinguishing fourimaginedlettersusing7TfMRIfrom primaryvisualcortex(V1–3),utilizingvisualtopography(Polimenietal.,2010).Althoughthisisanearlystep, one can imagineavisualcortexBCIsystemforpeople withLISwhocoulduseittospelllettersandwords. Howsuchasystemwouldignoreactualvisualinputis yettobedetermined.

Auditorycortex Decodingauditoryinputhasmainlybeeninvestigated withECoG.Theauditorycortexisonlypartlyexposed atthesurfaceaccessibletoECoG,butseveralgroups haveshownthatspectro-temporalaspectsofspeech andmusiccanbereconstructedfromperisylviancortex toacertaindegree.Martinmanagedtoreconstructboth heardandimaginedmusicplayedbyoneparticipanttoa promisingdegree(Martinetal.,2018),findingpartial overlap of theregion’sresponsetoboth.Decodingimaginedspeechwasalsostudiedbythesamegroup,but hereperformancewasratherlimitedcomparedtodecodingofheardorspokenwords(Martinetal.,2016).Others have focusedonauditorycortextoreconstructspeechby translatingbrainsignalsdirectlyorindirectlytoauditory output(spectrograms),withconsiderableperformance rates(Pasleyetal.,2012; Mesgaranietal.,2014; Akbarietal.,2019).Changandcolleaguesstudiedfeasibilityofdecodingspeechfromlargehigh-densitygridscoveringfrontal,parietal,andtemporallobes(Anumanchipalli et al.,2019).Theyusedasophisticatedanalysistomap brainactivitytoarticulatormovementsderivedfrom theaudiosignalandthen,fromthere,translatedsignals toaspeechsynthesizer.Whenlistenerswereaskedtotranscribewordsinsentencessynthesizedfromthebrainsignal decoders,havingalimitedsetofwordstochoosefrom, theycorrectlydidsoinalmosthalfofthesentences. However,sincetheauditorycortex(whichresponds tothesubjects ’ ownvoice)wasincludedindecoding, thereissomeworktodobeforearealBCIapplication canbeachieved.Nevertheless,theappealofbeingable todecodeattemptedspeechincommunication-disabled peoplewillinspirefurtherresearch.

Cognition MostoftheBCIapproachesfocusontheprimarycortex, asdescribedintheprecedingparagraphs.Conceptually, decodingcognitiveprocesseswouldbeattractivesince theymayprovideawindowtodetectintendedactions. SomeofthenoninvasiveapproachesutilizecognitionrelatedbrainactivitysuchastheP300EEGBCIand theerrordetectionprinciple(Chapter18).Sinceboth P300 andtheerrorpotentialonlyoccurwhenaperson isengagedinadeliberatetask,theyareregardedas

cognitiveprocesses.P300isapotentialthatfollows perceptionofanunexpectedandinfrequentstimulus (aflashorsound)andreliesonfocusedvisualorauditory attention.Thesourceisthoughttolieintheparietal cortex,althoughothersourceshavebeenreported. P300isaresponsethatlooksthesameonmultiple EEGorECoGelectrodesand,assuch,canbeusedas aselectioneventforthestimulusbeingobservedin BCI.(Inamatrixoficons,typicallyletters,eachicon flashesatadifferentmomentintime.)Theerrorpotential constitutesaresponsetoanunexpectedoutcomeofa cognitiveactionandisgeneratedwhenamistakeis perceived(Buttfieldetal.,2006).Itisthoughttooriginate from theanteriorcingulatecortexandcanbeused tocorrecterrorsmadeduringBCI-basedspelling. Anotherapproachistorecordsignalsfromregions involvedincognitiondirectly,suchasthoseforming thecognitivecontrolnetwork.Inparticular,thedorsolateralprefrontalcortexisregardedastheprimaryregion responsibleforallocatingcognitiveresources.Damage tothisregionleadstoaninabilitytochangemental strategy.Itisalsoinvolvedinworkingmemory,where itisthoughttocoordinateinformationflowandmaintain short-termmemoryofthatinformationintheauditory andvisualcortices.Itwasshownthatactivityinthis regioncanbewellregulatedbyperformingmentalarithmetic(Ramseyetal.,2006).Moreover,specificfocithat become activeduringarithmeticandthatsupportBCI inECoGpatientscanbefoundinthedorsolateral prefrontalcortex(Vansteenseletal.,2010).Inanindividual with LISduetolate-stageALS,electrodeswere placedonDLPFCtoprovideabackupincasethe electrodesonthemotorcortexfail(ALSaffectsthe motorneurons)(Vansteenseletal.,2016).BCIcontrol proved to bepossiblewiththeseelectrodes,supporting thenotionofcontrollabilityofthetargetedregion (manuscriptinpreparation).

FUTUREPERSPECTIVE WithintracranialBCIsystems,thedetailedcortical organizationofthehumanbraincanbecapturedto translateintentionstoactioninmoredetailthanwith noninvasivesystems.Multipleregionsarecurrently beinginvestigated,andwithadvanceddataanalysis, suchasneuralnetworks,deeplearning,andsupportvectormachines,performancecanbeexpectedtoimprove. BothindwellingmicroelectrodearraysandECoGgrids haveproducedpromisingresults,withdifferentprinciplesunderlyingeachapproach.Microelectrodearrays capitalizeondecadesofnonhumanprimateresearchinto mainlymotorandvisualregions,explainingafocuson decodinglimbmovementsforBCI.ECoGcapitalizes onthewealthofknowledgeaccruedwithnoninvasive imagingofthehumanbrainand,assuch,canreadily

targetanyregionaccessibleatthesurface.Itisunlikely thatoneapproachwillprevailoverothers,beitnoninvasiveorimplantable,sincedifferentsolutionsmaywell servedifferentneedsofendusers,andtheywilllikely appreciateachoiceofsolutions.Itwillalsotaketime forendusers,theircaregivers,andthemedicalprofession toadoptnewBCIsolutions,allowingtimeforprototype BCIsystemstobetestedinhumansandindustryto becomemoreengaged.Atanyrate,needsforBCI solutionsarelikelytorisewithaprojectedincreasein populationageandtheassociatedriskofneurologic deficits(Ramseyetal.,2014).Thefuturewillseeincreasinglysophisticateddecodingofbrainactivity,someof whichwillsatisfyend-userneedswhileotherapproaches maynot.OfparticularinterestareBCIsthatrestore communicationabilities(Chapter7)andBCIsthatclose the loopbetweenbrainandlimbwithsomatosensory feedback(Chapters13 and 22).Onafinalnote,alternative braininterfacingtechniques,suchasoptogenetics(Kim et al.,2017)orfocusedultrasound(Legonetal.,2014; Dizeuxetal.,2019)mayproveusefulforBCI,butas with manytechnologies,thetranslationtosafehuman useisanuncertainpath.

REFERENCES AkbariH,KhalighinejadB,HerreroJLetal.(2019).Towards reconstructingintelligiblespeechfromthehumanauditory cortex.SciRep 9:874. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598018-37359-z

Allison BZ, McFarlandDJ,SchalkGetal.(2008).Towards anindependentbrain-computerinterfaceusingsteadystate visualevokedpotentials.ClinNeurophysiol 119:399–408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2007.09.121

Andersson P, PluimJPW,SieroJCWetal.(2011).Real-time decodingofbrainresponsestovisuospatialattentionusing 7TfMRI.PLoSOne 6:e27638. https://doi.org/10.1371/ journal.pone.0027638

Andersson P, PluimJPW,ViergeverMAetal.(2013a). Navigationofatelepresencerobotviacovertvisuospatial attentionandreal-timefMRI.BrainTopogr 26:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-012-0252-z

Andersson P, RamseyNF,ViergeverMAetal.(2013b).7T fMRIrevealsfeasibilityofcovertvisualattention-based brain-computerinterfacingwithsignalsobtainedsolely fromcorticalgreymatteraccessiblebysubduralsurface electrodes.ClinNeurophysiol 124:2191–2197. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.clinph.2013.05.009.

AnumanchipalliGK,ChartierJ,ChangEF(2019).Speechsynthesisfromneuraldecodingofspokensentences.Nature 568:493. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1119-1

Arcaro MJ, KastnerS(2015).Topographicorganizationof areasV3andV4anditsrelationtosupra-arealorganization oftheprimatevisualsystem.VisNeurosci 32:E014. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952523815000115

Ashburner J (2012).SPM:ahistory.Neuroimage 62 – 248: 791 – 800. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011. 10 .025

BailletS(2017).Magnetoencephalographyforbrainelectrophysiologyandimaging.NatNeurosci 20:327–339. https://doi.org/10.1038/nn.4504

BauerPR,VansteenselMJ,BleichnerMGetal.(2013). Mismatchbetweenelectrocorticalstimulationandelectrocorticographyfrequencymappingoflanguage.BrainStimul 6: 524–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brs.2013.01.001

Berger H (1931). UberdasElektrenkephalogrammdes Menschen.ArchPsychiatrNervenkr 94:16–60. https:// doi.org/10.1007/BF01835097

Bleichner MG, JansmaJM,SellmeijerJetal.(2014).Giveme asign:decodingcomplexcoordinatedhandmovements usinghigh-fieldfMRI.BrainTopogr 27:248–257. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10548-013-0322-x

Bleichner MG, JansmaJM,SalariEetal.(2015). Classificationofmouthmovementsusing7TfMRI. JNeuralEng 12:066026. https://doi.org/10.1088/17412560/12/6/066026

Bleichner MG, FreudenburgZV,JansmaJMetal.(2016). Givemeasign:decodingfourcomplexhandgesturesbased onhigh-densityECoG.BrainStructFunct 221:203–216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00429-014-0902-x

Bouchard KE, MesgaraniN,JohnsonKetal.(2013). Functionalorganizationofhumansensorimotorcortex forspeecharticulation.Nature 495:327–332. https://doi. org/10.1038/nature11911

Branco MP, FreudenburgZV,AarnoutseEJetal.(2017). Decodinghandgesturesfromprimarysomatosensorycortexusinghigh-densityECoG.Neuroimage 147:130–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.12.004

Branco MP, deBoerLM,RamseyNFetal.(2019).Encoding ofkineticandkinematicmovementparametersinthesensorimotorcortex:abrain-computerinterfaceperspective. EurJNeurosci 50:2755–2772. https://doi.org/10.1111/ ejn.14342

Broca P (1865).Surlesie ` gedelafacultedulangagearticule. BullMemSocAnthropolParis 6:377–393. https://doi.org/ 10.3406/bmsap.1865.9495

BrodmannK(1908).Beitrage zur histologischenLokalisation derGrosshirnrinde,JohannAmbrosiusBarth,Leipzig. BruurmijnMLCM,PereboomIPL,VansteenselMJetal. (2017).Preservation ofhandmovementrepresentation inthesensorimotorareasofamputees.Brain 140: 3166–3178. https://doi.org/10.1093/brain/awx274

Buttfield A, FerrezPW,MillanJdR(2006).Towardsarobust BCI:errorpotentialsandonlinelearning.IEEETrans NeuralSystRehabilEng 14:164–168. https://doi.org/ 10.1109/TNSRE.2006.875555

CherrySR,PhelpsME(2002).18—imagingbrainfunctionwith positronemissiontomography.In:AWToga,JCMazziotta (Eds.),Brainmapping:themethods,secondedn.Academic Press,485–511. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0126930191/50020-4.

Combe G (1851).Asystemofphrenology,BenjaminB. Mussey&Company,Boston.Retrievedfrom, http:// archive.org/details/systemofphrenolo00combuoft Cox R W(1996).AFNI:softwareforanalysisandvisualizationoffunctionalmagneticresonanceneuroimages.

ComputBiomedRes 29:162 – 173. https://doi.org/ 10.1 0 06/cbmr.1996.0014

Dizeux A, GesnikM,AhnineHetal.(2019).Functionalultrasoundimagingofthebrainrevealspropagationoftaskrelatedbrainactivityinbehavingprimates.NatCommun 10:1400. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-09349-w Dumoulin SO, WandellBA(2008).Populationreceptivefield estimatesinhumanvisualcortex.Neuroimage 39:647–660. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.09.034.

Finger S (2005).ThomasWillis:thefunctionalorganizationof thebrain.Retrievedfrom, https://www.oxfordscholarship. com/view/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195181821.001.0001/ acprof-9780195181821-chapter-7.

Flesher SN, CollingerJL,FoldesSTetal.(2016).Intracortical microstimulationofhumansomatosensorycortex.Sci TranslMed 8:361ra141. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf8083.

Formisano E, KimD-S,DiSalleFetal.(2003).Mirrorsymmetrictonotopicmapsinhumanprimaryauditory cortex.Neuron 40:859–869. https://doi.org/10.1016/ S0896-6273(03)00669-X.

Fracasso A, LuijtenPR,DumoulinSOetal.(2018).Laminar imagingofpositiveandnegativeBOLDinhumanvisual cortexat7T.Neuroimage 164:100–111. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.02.038.

FranceschiniMA,BoasDA(2004).Noninvasivemeasurement of neuronalactivitywithnear-infraredopticalimaging.Neuroimage 21:372–386.

GaglianeseA,VansteenselMJ,HarveyBMetal.(2017). Correspondence between fMRIandelectrophysiology duringvisualmotionprocessinginhumanMT. Neuroimage 155:480–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. neuroimage.2017.04.007.

Glover GH (2011).Overviewoffunctionalmagneticresonanceimaging.NeurosurgClinNAm 22:133–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nec.2010.11.001

Haufe S, DeGuzmanP,HeninSetal.(2018).ElucidatingrelationsbetweenfMRI,ECoG,andEEGthroughacommon naturalstimulus.Neuroimage 179:79–91. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.016

Hermes D, MillerKJ,NoordmansHJetal.(2010).Automated electrocorticographicelectrodelocalizationonindividually renderedbrainsurfaces.JNeurosciMethods 185:293–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2009.10.005

Hermes D, MillerKJ,VansteenselMJetal.(2012). NeurophysiologiccorrelatesoffMRIinhumanmotorcortex.HumBrainMapp 33:1689–1699. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/hbm.21314

Hermes D, MillerKJ,WandellBAetal.(2015).Gammaoscillationsinvisualcortex:thestimulusmatters.TrendsCogn Sci 19:57–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2014.12.009