1 Introduction

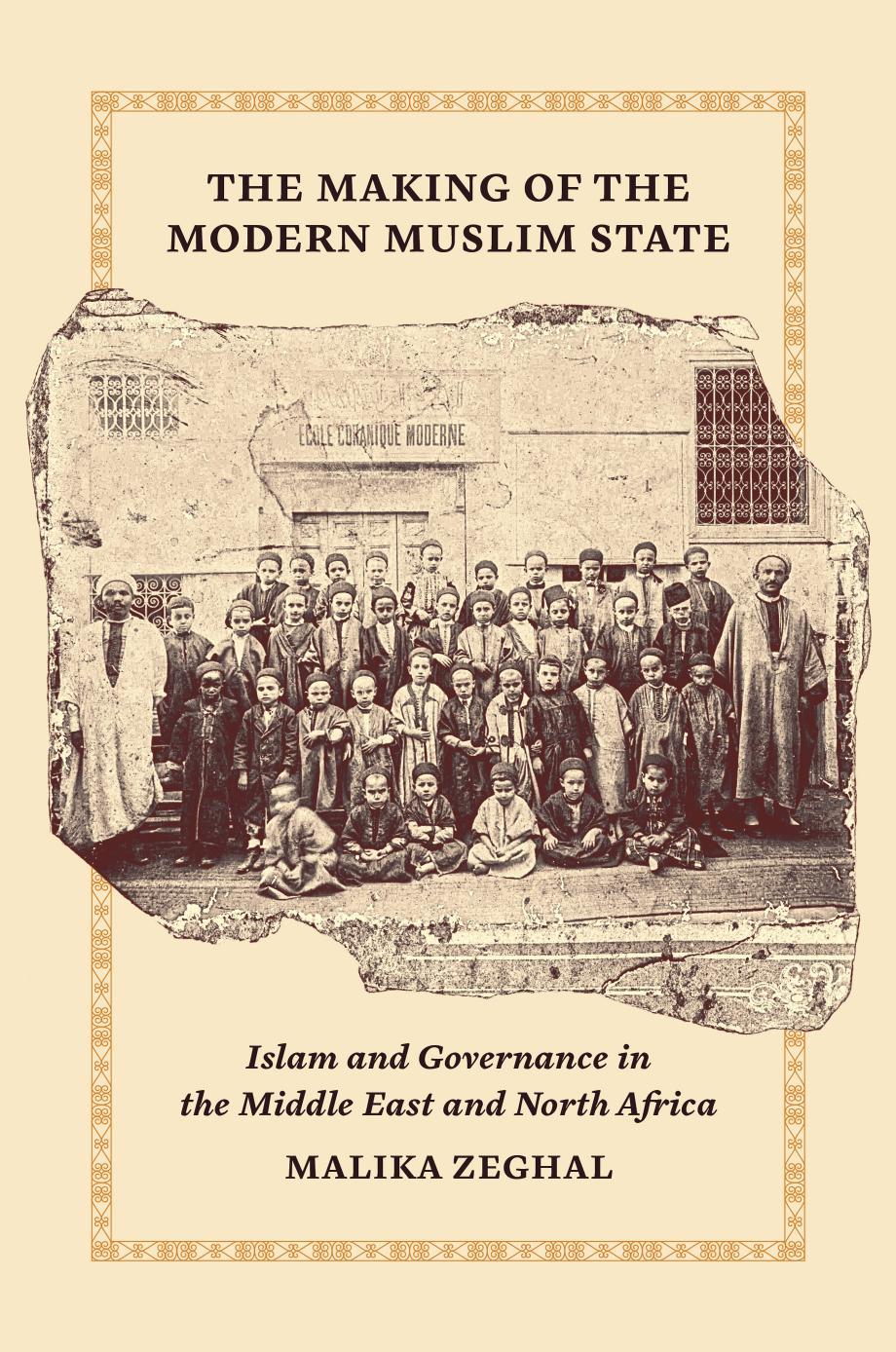

Onyourwaytothesewords,youprobablyskimmedpastafewpages containingtheusualperfunctorytextthatbeginsanybook,whatpublisherscallthe ‘frontmatter. ’ Withinthefamiliarblurof fineprintsitsa strikingstatement: “Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted.” There,amidtheformulaiclanguageannouncingpublisher’saddress, assertionsofcopyright,ISBN,andotheressentialpiecesoflegalboilerplate,thebookmakesaquietdemandofitsreader.Itaskshimto recognizethattheauthorofthebookhascertainrightswithrespectto itscontent.Moralrightsprotectthespecialintereststhatanauthorhasin herworkinsofarasitisherpersonalcreationandexpression,andthey aremaintainedevenwhentheauthorhassurrenderedhereconomic rightstoit.Underthedoctrineofmoralrights,thework beitan artwork,anovel,orevenapieceofacademicscholarship servesasa distalextensionoftheauthorasitleavesherhandsandpassesintoyours. Sheistherebyentitledtoretainacertaindegreeofcontroloverits disposition,presentation,andtreatment.

Consideredintheseterms,authorshipseemstoentailastrangeand powerfulbondbetweencreatorandwork.Thisisparticularlythecase withart,whichincontemporaryWesterncultureisseenasprimarilyif notpurelythepersonalexpressionoftheartist.Andyetwetendtotake theconceptofauthorshipforgranted.Peopleengagewithauthored worksallthetime.Theybuypaintings,readbooks,anddownload songs.Theymightevenbeartiststhemselves.Thebasicideathatan artistasauthormaintainssomekindofclaimtohiscreation,evenasit circulatesintheworldatlarge,seemsnatural.Inourfamiliaritywiththe functionsandtrappingsofauthorship,wepassoverthebookpublisher’ s frontmatterunlesssomereasoncompelsustoconsultit.Similarly,we acceptwithoutquestionthefundamentalconceptsuponwhichthoselegal declarationsarebased authorship,copyright,moralrights unlessan

unusualsetofcircumstances,suchasalawsuitorcontroversy,brings themtoourattention.

Myinterestinmoralrightsandthenatureofauthorshipbeganin 2007,whenabitterdisputebetweenanartistandamajormuseum locatedthirtymilesfrommyhometurnedintoalawsuitthatattracted internationalattention.Putsimply,thecasehingedonthequestionof whohadtherighttodeterminethefateofanabandoned,unfinished workofinstallationartinthemuseum ’slargestgallery.Themuseum wantedtoshowittothepublic;theartistinsistedthatitbedismantled anddiscardedwithouttheunfinishedworkbeingshown.AsIbeganto followthecaseclosely,Irealizedthatbothsideswereclaimingownership overthesamesetofphysicalobjects,butindifferentrespects:theartist wasassertingthattheunfinishedinstallationwas,inanimportantsense, his insofarasitwasanartworkthatheconceivedanddesigned,whereas themuseum,whichhadprovidedallofthe financialandlogistical supportforitsconstruction,claimedthatithadtherighttoshowthe abandonedobjectsassembledonitsproperty.Themuseumownedthe materials,buttheirpresencewaslargelytheresultoftheartist’schoices. Tothatextent,theyembodiedsomethingthatbelongedonlytohim:his artisticvision,hisintentions.Whiletheinstallationwasleftunfinished andunrealized,itwasneverthelessinmanyrespectshiscreation.But whohadtherighttodecidethefateofthese ‘materials,’ asthecourts,in anattemptatneutrality,calledthem?Howdoweparsethecompeting claimsoverthecorpseofthisunfinishedworkofart?Doesitmatterthat theartistnevergavetheworkthecarapaceofcompletionbydeclaringit ‘done’?Asartexperts,journalists,andjudgesweighedinonthe fiasco, Irealizedthatthedualnatureoftheartwork,asbothamaterialobject, andanauthoredcreation,isametaphysicaldistinctionthatcanleadto someveryconcretebattles.

Myfascinationwiththecasebetweentheartistandthemuseumalso becameaturningpointinmythinkingaboutphilosophicalaesthetics. Inoticedthatthedisputegeneratedalotofimpassionedclaimsbythe litigantsandbycommentatorsaboutthenatureofartandwhatitmeans tobeanartist.Whatseemedtobealegalwrangleovercontractsand propertybecameachargeddebateaboutontology,ethics,andthenature ofartisticauthorship.Thesearesubjectsthatphilosophersofarthave consideredingreatdetailforsometime.ButwhenIturnedtothe scholarlyliteraturetohelpclarifymythinkingaboutthecase,Inoticed

thatverylittleofitaddressedmyquestionsdirectly.Certainly,thereisno shortageoftheoreticalmaterialaddressingthesamegeneralareasof interestthatthiscasetouchedon.Philosophershavedevotedagreat dealofattentioninthepast fiftyyearstothedefinitionofart,itsnature, andontology.ArthurDantorevolutionizedthe fieldbymakingsomeof thetwentiethcentury ’smostchallengingartworksthecenterpieceofhis philosophicalreflectionsonartandaesthetics.Andinliterarycircles,the conceptofauthorshiphascomeunderagreatdealofscrutinyinrecent decades,inspiredbyBarthes’ andFoucault’snotoriousandhighlyinfluentialpolemicsagainstit.Allofthesewerehighlyrelevanttotheissues raisedbythecase.

AsIcontinuedtothinkandwriteabouttheseeminglydualcharacter oftheartworkasaphysicalembodimentoftheartist’simmaterialideas, choices,andexpressions,however,Isoonfoundmyselfataloss. Idiscoveredthattherewasverylittlewrittenaboutthenatureofthe relationbetweenartistandartwork,andwhatrightsorobligationsmight followfromthatrelation.Themessinessandhighstakesofthelawsuit gavethephilosophicalideasanewkindofurgencyandpotencythatare oftenmissingfromthetheoreticaltreatmentsofthesetopics.Butit becameincreasinglydifficultto findgenuinelyphilosophicalreflection onthequestionsraisedbythecaseamidtherhetoricalposturingofthe playersinvolved.

Hencethebookyouholdinyourhands.Itisaphilosophicalessayon artisticauthority:itssources,nature,andlimits.Unlikemanyworksof academicphilosophy,however,thisinquirydrawsuponreal-worldcases andcontroversiesincontemporaryart.Artworks,itiswidelyagreed,are theproductsofintentionalhumanactivity.Andyettheyaredifferent fromotherkindsofartifacts;theyareunderstoodtobefundamentally andprimarilytheexpressionofsomemeaningintendedbytheirmakers. Forthisreasonitisoftenpresumedthatartworksareanextensionof theirauthors’ personalitiesinwaysthatotherkindsofartifactsarenot. Thisismanifestinourrecognitionthatanartistcontinuestoownhisor hercreationevenoncetheartobjectbelongstoanother.IfIbuya handmadewoodentable,IcandowhateverIwishtotheartifactin mypossession.Icanleaveitoutsideintherain,useitfor firewood,or paintitpurple.NotsowithawoodenMartinPuryearsculpture.The VisualArtists’ RightsAct(VARA),whichistheUSstatutegoverningthe moralrightsofartists,protectsartworksof “recognizedstature” from

intentionaldestruction.1 Italsoenjoinstheownersofartworksfrom mutilating,distorting,orfalsifyingtheauthorshipoftheworksintheir possession.Copyrightpreventstheownerfrommakingandselling derivativeworkssuchasfacsimilesoftheartworkorcoffeemugs adornedwithitsimage.Thelawtherebygrantsartistsadegreeofcontrol overtheircreationsthattheproducersofotherkindsofartifactsdo notenjoy.

Butitisfarfromclearhoworwhyartistsacquirethisauthority,and whetheritoriginatesfromaspecial,intimatebondbetweenartistand work,asthetraditionaljustificationofartisticmoralrightswouldhaveit. Thesequestionsareparticularlypointedinourcontemporaryculture. Thelegaldoctrineofartisticmoralrightshasgainedinternational recognitionandstrength.Andyettherhetoricofpostmodernism, whichhasbeensoinfluentialinbothartandtheory,criticizesand evendisavowstheRomanticideologyofauthorshipthatvalorizesthe solitarycreator-genius,uponwhichthatdoctrineisbased.Thistension becomesparticularlypointedinrecentcontroversiesinvolvingcontemporaryvisualart,becausethatiswherethesetwoworldscollidemost explosively:thelegalandtheideal.

Thus,ourunderstandingofthenatureandextentofartisticauthority issignificantformanyreasons.Ithasphilosophicalimportanceinsofar asitbearsonontologicalquestionsconcerningtherelationbetweenthe artobjectandtheartwork.Wheredoestheobjectendandthework begin,suchthattheartistcanlegitimatelyclaimauthorityandownership overthework,evenastheobjectthatembodiesitbelongstoamuseum orcollector?Itisalsorelevanttotheproblemofhowtheartobject expressestheintentionofitsmaker.Howandtowhatextentdoesartistic authorityextendbeyondtheboundariesoftheartworkandtoitsinterpretation?Howdoesthisshiftinthecaseofontologicallyinnovative works,inwhichweareunusuallydependentonstatementsfromthe artisttoindicatewhat,precisely,constitutesthefeaturesoftheworkthat arerelevanttointerpretation?Andhowdowereconcileourrecognition oftheauthorshiprightsofartistswiththeadvancesincontemporaryart

1 Whiletheprecisedefinitionof “recognizedstature” hasneverbeenclarifiedforthe purposesofthislaw,Puryear’swork,whichiswidelycollectedbyandexhibitedinmajor internationalartmuseums,wouldmostcertainlyqualify.

thathavesoughtpreciselytoproblematize,deny,andchallengethevery assumptionsthatgroundthoserights?

Theconceptofartisticauthorityalsodemandsourphilosophical attentionbecauseitentailsprovocativemetaphysicalandontological assumptionsaboutthenatureofauthorship.Theseclaimsinturn shapethelegallandscapesurroundingcopyrightandartisticmoral rights.Andyet,asIhavementioned,ithasgonelargelyunexaminedin thephilosophicalliteratureonartandaesthetics.Perhapsthisisbecause thefoundationalideassurroundingthenatureofauthorshipareassumed tobetheproperprovinceofoneortheotheroftwoalientribes:onthe onehand,culturalandliterarytheoristshavelongexpoundedthetheory ofthe ‘deathoftheauthor.’ Onapurelytheoreticallevel,atleast,they havesoughttodismantletheconceptofauthorship.Ontheotherhand, scholarsofintellectualpropertyandcopyrightlawdealinthelegal manifestationsofauthorship.Thepostmoderncritiqueoftheconcept ofauthorshipseemsnottohavetouchedthelegalrealminanysignificantsense.Inthislatterbodyofliterature,we findmanyimpassioned advocatesforartists’ rights,buttheauthorsdonotalwayssubmittheir arguments’ assumptionstocriticalreflection. Againstthebackdropofthisscholarlylandscape,somearguethat philosophershavenoplaceoneitherterrain.Theyareusuallynot qualifiedtocommentonmattersrequiringlegalexpertise.2 Andanalytic philosophersdonotgenerallyhavemuchpatiencefororinterestinthe post-structuralistattacksontheconceptofauthorshipthathavebeen inspiredbyFoucault.3 Itmayseemasthoughthereisnousefulphilosophicalworktobedoneontheconceptofartisticauthorship,andthat wearebetteroffcontinuingtofocusonitsendproduct:artandartworks. However,asDarrenHudsonHickpointsout,thefoundationalideas underpinningtherightsofauthorsintheirworksaremostdefinitely philosophical,andtheconceptualconfusionthatsurroundsthemis

2 RogerShiner, “Ideas,Expressions,andPlots,” JournalofAestheticsandArtCriticism 68,no.4(2010).

3 SeePeterLamarque, “TheDeathoftheAuthor:AnAnalyticalAutopsy,” British JournalofAesthetics 30,no.4(1990).SeealsothedebatebetweenJohnSearleandJacques Derridasurroundingthelatter’sattempttodeconstructcopyrightinJacquesDerrida, LimitedInc,trans.JeffreyMehlmanandSamuelWeber(NorthwesternUniversityPress, 1988).

preciselythekindof ‘housekeeping’ (intheWittgensteiniansense)that philosophyisgoodfor.AsHickputsit:

Copyrightlawisrifewithmetaphysicalassumptionsaboutitsobjects beginning withtheprinciplethatauthoredworksareabstractratherthanmaterialobjects. Thelawgoesfurtherinsuggestingthatideasarethingsthemselves embodied in authoredworks.Theseareontologicaldistinctions,andinopeningthedoorto ontology,thelawinvitesinthephilosopher.Introducingintocopyrightlawa centraldistinctionbetweenideasandexpressionsislikeembossingtheinvitation ingold.Andwhenthelawisconceptuallyconfused,whetheraboutitsown technicalconceptsorthoseofordinaryusage,Iwouldarguenotonlythatthe doorisopen,butalsothatitisthephilosopher’ s duty tostepthroughit.4

Thelegaldomainisafertilesitefortheoreticalinvestigationofartistic authoritybecauseitisthemeetingpointofthemetaphysicalandthe everyday.Anditisthere,wherethesetwomakecontact,thatabetter accountcanbegiven.

Incasesoflegalcontestregardingtherightsofauthorsintheirworks, thehithertoimplicitvalues,norms,andassumptionssurroundingartistic authorityarerenderedexplicit.Theroleofthephilosopherwithrespectto artworldcontroversiesisnotnecessarilytotakesides,particularlywhen suchcaseshingeonlegaljudgments.Thephilosophercan,however, criticallyexaminetheargumentsgiveninsupportofeachsideand determinewhethertheyarecoherentorconfused.Shecanalsoexamine conceptssuchas ‘artisticfreedom’ thatarebothrhetoricallyloadedand semanticallyvagueinordertoseekgreaterclarityabouttheprinciples theyuphold.Moreover,thephilosopherhastheabilitytosuspendjudgmentonthespecificlegalquestionsthatariseinagivencasesoastofocus onthelargerprinciplesorculturalvaluesatstakeintheconflict.

Somemightarguethatorganizingone’sinquiryaroundreal-world casesmaydeflectenergyandattentionfromthephilosopher’ sproper taskofpureconceptualanalysis.Butwhileanalyticaestheticsisnot concernedwithsimplyprovidingadescriptiveaccountoftheartworld’ s activity,itcannotignoreactualartworksandtheculturalnormsand practicessurroundingartinthenameofpuretheory,either.Isharethe viewofphilosopherssuchasAmieThomasson,SherriIrvin,andDavid Daviesthatartisticpracticeisfoundationaltoanyadequatephilosophical

4 DarrenHudsonHick, “ExpressingIdeas:AReplytoRogerA.Shiner,” Journalof AestheticsandArtCriticism 68,no.4(2010):407.

reflectiononart.AsIrvinputsit, “onlybylookingcarefullyatparticular, realworkscanwedevelopadequatetheoriesofcontemporaryart,and, indeed,ofartingeneral.”5 Thesameistrueforartisticauthorship a conceptthatisassumedbyallphilosophersofartasanecessarycondition forsomethingtobeanartwork,butwhichgenerallygoesunexamined. Thisbookseeksto fillthatgap.

InChapterTwo,Iconsiderthenatureofartisticfreedomandmoral rights.Ishowthattheseconceptshavetheirsourceinaconceptionof authorshipthatisassumedbutincorrectlyaccountedforinboththelegal andphilosophicalliterature.Ithenpresentmy ‘dual-intentiontheory’ of authorship.Iarguethatartisticauthorshipentailstwoordersofintention:the first, ‘generative’ moment,involvestheintentionsthatguidethe actionsthatleadtotheproductionofanartwork.Thesecondmomentis theevaluativemoment,inwhichtheartistdecideswhetherornotto acceptandowntheartworkshehasmadeas ‘hers.’ Thissecondmoment oftengoesunnoticedinthetheoreticalaccountsofauthorshipbecauseit onlybecomesexplicitwhenchallenged:hencetheimportanceofusing real-worldcontroversiesasalensthroughwhichwecanbetterunderstandthenatureofartisticauthority.

InChapterThree,Ilookattherelationbetweenthesecondmomentof authorship,inwhichtheauthorratifiestheworkashisorherown,and anothercrucialbutoftenoverlookedaspectofauthorship,whichis artworkcompletion.Thesetwomomentsarelogicallyseparatebut oftencollapsed,bothintheoryandinpractice.Iexplainwhatisatstake forauthors,audiences,andphilosophersindeterminingwhetheran artworkis finishedornot.ClementGreenberg’scontroversialdecision tostripthepaintfrom fiveofthelateDavidSmith’ sunfinishedsculptures servestoillustratehowunfinishedworkscomplicateanyclaimstoa moralrightofintegritywithrespecttoartworks.Finally,Iturntothe philosophicaldebatesurroundingthenecessaryandsufficientconditions forartworkcompletion.WhileI findmuchtoagreewithintheirwork, I findthatbothHickandLivingston,thechiefinterloctorsinthisdebate, commitafundamentalerrorinontologywhenreasoningaboutartwork completion.Becausebeing finishedisarelationalpropertyofanartwork

5 SherriIrvin, “TheArtist’sSanctioninContemporaryArt,” JournalofAestheticsand ArtCriticism 63,no.4(2005).SeealsoDavidDavies, “ThePrimacyofPracticeinthe OntologyofArt,” JournalofAestheticsandArtCriticism 67,no.2(2009).

thatistiedtothepotentiallyvacillatingattitudes,beliefs,anddispositions oftheartist,thereisnosinglemomentwhenaworkcanbesaidtocross thethresholdfromincompletetocompletesuchthatitsformalfeatures areirrevocablylockedin.Artworkcompletionisultimatelyprovisional.

InChapterFour,IprovideananalysisoftheaforementionedcontroversybetweentheMassachusettsMuseumofContemporaryArt(Mass MoCA)andtheartistChristophBüchel.Thiscaseprovidesaclear exampleofasituationinwhichthesecond,evaluativemomentofart authorshipisthrownintohighrelief,astheartistrefusedtorecognizeas ‘his’ aworkthatheneverthelesssawhimselfashavingauthoredinthe generativesense.Thisexplainstheseeminglyparadoxicalsituationthat arose,inwhichheclaimedthattheunfinishedartworkwasnota ‘Büchel,’ andyetheneverthelessinsistedonhisrightasauthortodetermineits fate.Inmyview,theMassMoCAcaserepresentsasignificantchallenge tothewidespreadartworldintuitionthatthecreativefreedomoftheartist shouldbegivenvirtuallyabsoluteprecedenceindecisionsaboutthe creation,exhibition,andtreatmentofartworks.Iarguethatthisviewis incorrect:respectfortheartist’smoralrightsdoesnotrequiredeferringto theartist’swishesineverycase.Ishowthatthedistinctionbetween artifactualownershipandartisticownershipthatunderliesthenotionof artisticmoralrightsalsoservestoestablishlimitsonthoserights.

InChapterFive,IreconsiderIrvin’stheoryofthe ‘artist’ssanction,’ whicharticulatestheauthorityofartiststodeterminetheboundariesof ontologicallyinnovativeworksofartthroughtheirpublicdeclarations. Whilethistheorysharessomesimilaritieswithmy ‘dual-intentiontheory ’ ofartauthorship,itisimportantlydifferentinscope.Iarguethatthis principleeffacestheboundarybetweentheartist’sauthoritytodetermine,ontheonehand,thedispositionoftheworkasanobject-to-beinterpretedand,ontheotherhand,theproperinterpretationofthe work.Iturntotheexampleofsite-specificartworkstoillustratethe theoreticalandpracticaldifficultiesthatcanarisewhenartistsusetheir authoritytobestowfeaturesofanartworkthroughtheirdeclarations.

ChapterSixexaminestheproblemofappropriationartasaseemingly paradoxicalrenunciationandreinforcementofartisticauthority.Ithen turntotheestablishedphilosophicaldebatesurroundinginterpretive intentionalisminlightofthe2008lawsuitbetweenphotographerPatrick CariouandthecontemporaryappropriationartistRichardPrince.This caseillustratestheessentialrolethatintentionalismplaysindeciding

copyrightsuits.Ithenconsiderthephilosophicalproblemssurrounding thelegalstatusofappropriationart.Anumberofscholarshaveproposed waysforthecourtstoaccommodateappropriationartwithouteroding copyrightprotectionsforauthors.Iconsidersomerecentproposalsand rejectthem.Ithenarguethatappropriationartshouldbeconsidered derivativeandhencepresumptively unfair.Thisisactuallymorein accordwithappropriationart’stheoreticalpurposetoundermineoriginalityasanidealofauthorship.

IntheConclusion,Iarguethatthechallengestoartisticauthorityby contemporaryartpracticehavecertainlyenlargedoursenseofwhatkinds ofthingscountasartworks,andbyextensiontheyhavealteredoursense ofwhoartistsareandwhattheydo.However,whilethelandscapeofart haschanged,theseidealorrhetoricalchallengestothemodernistideologyofartisticauthorityhavenotinfactpenetratedourmostdeeplyheld culturalbeliefsandpracticessurroundingtheartist’sspecialrelationship tohisorherwork.Theconceptoftheartistservesasaregulativeideal, andthegesturesbytheavant-gardetodemystifyordestroythisideal servealargelyrhetoricalfunction.However,thisisnotacondemnationof contemporaryartistsashypocritesorcharlatans,assomemighthaveit, butratheranacknowledgementthatourcurrentsystemforrecognizing andvaluingartworksdependsontheconceptionofartworksasprimarily theexpressionoftheirmakers,andhenceasuniquelytiedtothem.Truly ontologicallyinnovativeworksthatdonotaccommodatethemselvesto thisconceptionrisknotbeingrecognizedasartworksatall.

Inthechaptersthatfollow,Idonotofferanabstract,universal definitionofauthorship,nordoIattemptasociological ‘thickdescription’ ofauthorshipasitfunctionsintheartworldcontext.Myapproach stakesoutanintermediatepositionbetweentherarefiedairofthehighaltitudetheoristandtheboots-on-the-grounddescriptivistinorderto provideaphilosophicalaccountofthebasicstructureofthemomentin whichauthorshipemerges.6 Iintendforthisbooktobeanexampleof thekindofreflectiveequilibriumbetweendescriptionandanalysisthata robust,culturallyrelevantphilosophyofartaimstocultivate.

6 Ontheaimandmethodologyofanalyticaesthetics,seealsoNicholasWolterstorff, “PhilosophyofArtafterAnalysisandRomanticism,” JournalofAestheticsandArtCriticism 46(1987);LydiaGoehr, TheImaginaryMuseumofMusicalWorks,Reviseded.(NewYork: OxfordUniversityPress,2007).

2 Art,Authorship,and Authorization

Alargepartofourpracticeis,andquitecommonlythroughthe historyandtraditionofWesternart(towhichweareconstantly adjuredtoattend)hasbeen,preciselynottotreatvisualworksas physicalobjects.1

I.TheDramaoftheGiftedArtist

InDecember1897, TheNewYorkTimes reportedthatthelawsuit betweenartistJamesMcNeillWhistlerandSirWilliamEdenhad endedinwhattheartistdeclareda “triumph”:theParisCourtofAppeal determinedthatWhistlercouldnotbeforcedtohandoveracommissionedportraitofLadyEdenagainsthiswishes.Thedisputearoseover Whistler’spiquedresponsetoEden’spaymentforthepicture.Theyhad agreedthatthepricefortheportraitwouldbebetween100and150 guineas,butWhistlerwasinsultedwhenSirEdengavehima “valentine” onFebruary14,1894containing100guineasforthepicture,theminimumamount.The Times articlepointsoutthat “Whistlerisapeculiarly sensitivepersonality,aseverybodyknows. ”2 Theartistrefusedtohand overthepainting,Edensued,andtheappellatecourtruledthatWhistler couldbemadetopayEdendamages,butcouldnotbeforcedtogive Edenthepainting,whichWhistlerinanycasehadalteredbypainting overLadyEden’sface.

1 FrankSibley, ApproachtoAesthetics:CollectedPapersonPhilosophicalAesthetics,ed. JohnBenson,BettyRedfern,andJeremyRoxbeeCox(Oxford:ClarendonPress,2001),266.

2 “Whistler’sParisSuitEnded:HeMayKeepthePictureofLadyEdenandDeclaresHis Triumph,” TheNewYorkTimes,December18,1897.

Theartist’slawyersarguedthatthebreachofcontractwasaninstance oftheartist’sabsoluterighttorefusetodeliverhisartwork,forany reason.Asl’AvocatGénéralBulotputit, “whatheprotestsagainstinthe nameofpersonalfreedom,thefreedomoftheartist,theindependence andthesovereigntyofart,isthejudgmentwhichcondemnshimto deliverthepictureinitspresentstate. ” ThecaseistakenbyFrench scholarstobealandmarkdecisionintheartist’smoralrightofdisclosure. 3 (The firsttechnicaluseoftheFrenchterm ‘droitmoral’,ormoral right,occurredjusttwentyyearsbefore Edenv.Whistler).4 Therightof disclosure,alsoreferredtoastherightofdivulgation,protectstheartist’ s righttodecidewhenorwhethertoreleaseanartworktothepublic.5 Moralrightsareacollectionofrightsdesignedtorecognizeandprotect thenon-economicrightsofartistsintheirworks.Inadditiontotheright ofdisclosure,theserightstypicallyincludetherightofintegrity,whichis theobligationnottodistortordismemberanartwork,andtherightof attributionor ‘paternity’,whichistherightoftheartisttohavehisorher nameattachedtothework.InEurope,ithasincludedtherightof withdrawal,whichundercertainconditionsentitlestheartisttoalter ortakebackanartworkthathasenteredthepublicsphere.

Justoveracenturylater,inanother NewYorkTimes article,artcritic RobertaSmithexpressedheroutrageattheMassachusettsMuseumof ContemporaryArt(MassMoCA)forattemptingtoshowSwissartist ChristophBüchel’sartinstallationagainsthiswill.6 Theexhibition wassupposedtohaveopenedinDecember2006,butfounderedover

3 CyrillRigamonti, “DeconstructingMoralRights,” HarvardInternationalLawJournal 47,no.2(2006):373.Whilepointingoutthatithasbeeninterpretedasafoundationalcase fortheartist’srightofdisclosureintheFrenchscholarshiponmoralrights,Rigamonti arguesthatthiscaseisbetterunderstoodmoresimplyasarisingfromageneralruleabout servicecontracts.

4 CyrillRigamonti, “TheConceptualTransformationofMoralRights,” TheAmerican JournalofComparativeLaw 55(2007).

5 OneoftheironiesofthiscaseisthatWhistlerhadexhibitedthepaintingattheSalon duChampsdeMars,soithadinthatsensealreadybeendisclosedtothepublic.Whatwas atissueinthelawsuitwaswhetherhecouldbecompelledtohandoverthepaintingtoEden oncehedecidedthat100guineaswastoolowaprice(thoughhehadcashedEden’scheck).

JohnHenryMerryman, “TheRefrigeratorofBernardBuffet,” in ThinkingAbouttheElgin Marbles:CriticalEssaysonCulturalProperty,Art,andLaw (AlphenaandenRijn:Kluwer LawInternational,2009),407.

6 RobertaSmith, “IsItArtYet?AndWhoDecides?,” TheNewYorkTimes,September16, 2007.

disagreementsbetweentheartistandthemuseumoverthebudgetand construction,eventuallyleadingtoBüchel’sabandonmentoftheproject. Themuseum,whichhadinvestedover$300,000ofitsownmoneyand ninemonthsoflaborinthework,wasunwillingsimplytodiscardthe assembledobjectsthat filleditsfootball-fieldsizedGallery5.Itsought permissioninfederalcourttoshowtheun finishedworktothepublic.At issueinthelawsuitwaswhetherthe1990VisualArtists’ RightsAct,a subsetofUScopyrightlawthatprotectsthemoralrightsofartists, appliedtounfinishedworksofart.Unlike Edenv.Whistler,theoutcome ofthiscasewasnottriumphantforeitherparty.Afteranappellatecourt partiallyoverturnedthedistrictcourt’srulinginfavorofthemuseum, thetwopartiessettledquietly,andtheassembledobjectsofGallery5 werenevershowntothepublic.

Inthe110yearsbetweenthesetwolawsuits,ourunderstandingof whatartis,whatitcanlooklike,howitismade,anditsproperroleand functioninsocietyhasundergoneaprofoundtransformation.Whistler wasavirtuosoeaselpainterwhomadeportraitsofwealthypatrons’ wives,whereasBüchelisaninstallationartistwhomakesedgy,politically chargedenvironmentsusingassemblagesofjunk.Andyettherearesome tellingsimilaritiestothecases.Bothartistsrenegedontheirverbal agreementstodeliveranartworkandyetclaimedthatthey,notthe commissioners,werethevictimsinthetransaction.WhistlerandBüchel werecastbytheirsupportersasmakingaprincipledstandfortheir freedomasartistsnottobeboundbypriorcontractsoragreements. JustasWhistlerhadareputationforbeing ‘sensitive,’ Büchelwasknown tohaveadifficult,mercurialpersonality,whichwastreatedbysomeasa signofhisauthenticity.AsSmithputit: “MaybeMr.Büchelwasbehavinglikeadiva.Butwhatsomecalltempertantrumsareoftenanartist’ s last,furiousstandforhisorherart.”7

LikeWhistler’slawyer,Smithsawadeepersignificanceinwhat,onthe surface,mightseemtobeasimplecontractdispute.Thiswasnota matteroffailedcommunicationorunmetexpectations:whatwasreally atstakewastheabsoluterespectforBüchel’sartisticfreedomthatthe museumfailedtoheed.Thisviewimpliesthatthenatureofartistic creationissomethingspecial,outoftheordinary,suchthatartistscannot 7 Ibid.

berequiredtoproduceartworksinthesamewaythatotherkindsoffeefor-servicelaboriscarriedout.Theunspokenpremiseinbothcasesis thatthedemandsofartsupersedevenalconcernsovermoney,contracts, orprofessionalobligation.Thedoctrineofartisticfreedompermitsthe artisttooperateoutsideoftheusualrulesandobligationsentailedby sucheconomicarrangements.Thisisundoubtedlyrelatedtotheideals thatwehaveinheritedfromtheRomantictradition,inwhichartand artistsgenerallyareseentooperateoutsideofrulesandconvention.8 But whileagreatdealofefforthasbeenexpendedbothwithinartistic movementsandintheoreticalcirclestorejectthisRomanticheritage, ourbeliefsandbehaviorssurroundingartandartistsshowthatthis disavowalhasinmanyrespectsbeenmorerhetoricalthanreal.

II.ArtisticFreedomandMoralRights

Onaculturallevel,thereisawidespreadintuitionthatthecreative freedomoftheartistshouldbegivenvirtuallyabsoluteprecedencein decisionsaboutthecreation,exhibition,andtreatmentofartworks.But theconceptofartisticfreedom,likethatofacademicfreedom,isas slipperyasitispotent.Itsindeterminacymayinfactlendtheconcept somepower,sinceitcanbeuncriticallyappliedtomanydifferentkinds ofsituationsinvolvingartistsandtheircreations.PhilosopherPaul Crowtherhasobservedthattheprevailingconceptionofartisticfreedom isessentiallynegativeincharacter:itisbased “purelyontheabsenceof ideologicalorconceptualrestraint.”9 Thisidealofartisticfreedomstems fromtheconceptionoftheartistasoutsider,visionary,sufferer,andrebel thatwasconsolidatedinthelatenineteenthcenturyandwhich,Iwill argue,wearestillinthralltotoday.10

Insomecases,thenotionofartisticfreedomistakentomeanthatan artistshouldbeabletodictatehiscreativevisionforaworknomatter

8 Kant’sdefinitionofgeniusisthe locusclassicus fortheexpressionofthisidea. Adorno’sunderstandingofartashavingafundamentallydualcharacter,inwhichit participatesinandyetisdistantfromthesocialworld,isalsoanimportantoutgrowthof thistradition.Hisideathatartisticfreedomisavehicleforcriticalreflection fitswithhis understandingofart’sliminalstatus.TheodorAdorno, AestheticTheory,trans.Robert Hullot-Kentor(Minneapolis:UniversityofMinnesota,1997).

9 PaulCrowther, “ArtandAutonomy,” BritishJournalofAesthetics 21(1981):12.

10 SeeAlexanderSturgisetal., RebelsandMartyrs:TheImageoftheArtistinthe NineteenthCentury,ed.NationalGallery(London:YaleUniversityPress,2006).

howmuchitcosts,whoispaying,andwhomitaffects.11 Inreality,most artistswhotrytomakealivingfromtheircreationsstrugglewiththe veryrealconstraintsofbudgets,commissions,andgalleryfees.They mustconstantlycompeteforclients,theattentionofcurators,and publicityinadenselycrowded fieldofwould-beWhistlersandBüchels. Inalllikelihood,onlythetinyminorityofartworldsuperstarscanreally besaidtoenjoycreativefreedominanypracticalsense.12 Nevertheless, therhetoricsurroundingartisticfreedominboththepopularcultureand inthelegalsystemcanhavepowerfuleffects.Forexample,despite initiallywinningitssuittounveilBüchel ’sabandoned,unfinishedinstallationtothepublic,MassMoCAdecidedtodismantleit,inpartfrom fearofthebacklashthatwasstokedbytheartworld’soutragededitorials. Amuseumdevotedtotheproductionofnewworksofcontemporaryart cannotbeseenbythepublicanditsdonorsasanenemytoartists.

Thephrase ‘artisticfreedom ’ oftencallstomindtheproblemof censorship,thatis,casesinwhichartistsarenotfreetoexpresscontroversialideaspubliclywiththeirart.Thisisthemainaspectofartistic freedomthatphilosophershavegiventheirattentionto,presumably becauseitinvolvesethicalandpoliticalquestionsaboutthenatureof freespeechandtherightofthestatetolimitthatspeech.13 Inthemass media,aswell,theideathatartisticfreedomisprimarilyaproblemof censorshipisreinforcedwhenevercontemporaryartistsprovokepopular outragewiththecontentoftheirworks.TheCorcoranGallery’scancellationofaMapplethorperetrospectivein1989duetohisincendiary photographsofnudegaymen,SenatorJesseHelm’soutrageover Serrano’ s PissChrist (1987),whichfeaturesthephotographofacruci fix submergedintheartist’surine,andOfili’ s HolyVirginMary (1996), whichincorporatedpornographicimagesandelephantdung,andwas denouncedbyNewYorkmayorRudyGuliani,arethreenotoriouscases

11 Foradetailedandwonderfullyentertainingautopsyofsuchacase,seeStevenBach, FinalCut:Art,Money,andEgointheMakingofHeaven’sGate,theFilmThatSankUnited Artists,updateded.(NewYork:NewmarketPress,1999).

12 SeeHenryFinney, “MediatingClaimstoArtistry:SocialStratificationinaLocal VisualArtsCommunity,” SociologicalForum 8,no.3(1993).

13 SeeHaigKhatchadourian, “ArtisticFreedomandSocialControl,” JournalofAesthetic Education 12,no.1(1978);E.LouisLankford, “ArtisticFreedom:AnArtworldParadox,” JournalofAestheticEducation 24,no.3(1990);JulieVanCamp, “FreedomofExpressionat theNationalEndowmentfortheArts:AnOpportunityforInterdisciplinaryEducation,” JournalofAestheticEducation 30,no.3(1996).

fromthepastfewdecadesinwhichtheartist’sfreedomtoexpress controversialcontentinapublicforumwascalledintoquestion.

Whilecensorshipoftheartsiscertainlyanimportantissue,itisnot thedimensionofartisticfreedomthatIamconcernedwithhere.The questionoftheartist’srighttoshowobsceneoroffensiveartworksin publicinvolvesever-shiftingpopularstandardsofdecency,aswellas governmentaltoleranceforartisticexpressionthatitdeemsinappropriateorthreatening.Inshort,ithastodowithartisticexpressionsthat challengethenormsofwhatcanandcan’tbesaidinpublic.Butthis aspectofartisticfreedomleavesuntouchedthequestionsofwhatit meanstoauthoranartworkinthe firstplace,whatthenatureofthe relationisbetweenartistandwork,andinwhatwaysartworkshave expressivecontentakintoverbalutterances.

TheWhistlerandBüchelcasesinvolvewhatIseeasadeeper,more fundamentalsenseofartisticfreed om,becausetheyinvolvetheartist ’ s assertionofhisrightnottoproduceordeliverapromisedworkofart. Ratherthantouchingonthepoliticalquestionofacommunity’ s responsetoanartwork ’ scontent,thesecaseshingedonthenotion thatartistsretainaspecialdegreeofcontrolovertheircreations preciselybecausetheyare artworks andnotsomeotherkindofcommissionedartifact,suchasatableorashed.Thesecasesarepowerful illustrationsoftheculturalvaluethatweattachtoartists,thefascinationthattheyholdforusaspersonalities,andthedif fi cultiesthatcan arisewhenwetrytounderstandthenatureofartisticlabor assuming weshouldunderstanditaslaboratall.WhenWhistlerinsiststhathe hastherighttowithholdhispaintingofLadyEdenfromthemanwho commissionedit,orBüchelclaimsthathehastherighttonotonly abandonhisun fi nishedartinstallationinMassMoCA ’slargestgallery, buttoinsistthattheyremoveanddiscarditattheirownexpense,their argumentsarepremisedontheideathatartworksarespecialcreations. Artisticfreedominthiscontextdoesnotconcernobjectionablecontent,butratherpointstothenotionthatartworkshaveauniquestatus asextensionsoftheirmakersinsofarastheyaretheirpersonalexpressions.Theprincipleofartisticfreedomsuggeststhatsuchexpressions cannotbecompelled,evenwhentheartisthadpreviouslyindicatedthat hewouldproducethework.

Thisbasicidea thatartworks,unlikeotherkindsofartifacts,are extensionsoftheartist’spersonhood isthepremisethatunderliesthe

legalrecognitionofartisticmoralrights.14 Behindthisstrange-sounding phrase(howcananobjectbeanextensionofitsmaker?howliterallyare wesupposedtotakethisexpression?)liestherecognitionthat1)inthe Westernartworld,artisticreputationisaformofwealth;2)artworksare seenastheexpressionoftheirmakers,overwhichtheyhavetotalcontrol andresponsibility;3)artistsshouldthereforehavetherighttocontrol howandwhenthoseexpressionsarepermittedtocirculatebecause 4)theirreputationsdependonhowthoseartworksareseenandunderstood.Totakeanexamplefromtheater,SamuelBeckettwasnotoriously sensitivetoanydeviationfromhisdirectionsintheproductionofhis plays.HebroughtlegalactionagainstaDutchtheatercompanyfor mountingaproductionof WaitingforGodot withanall-femalecast, becausehefeltthatitmisrepresentedhisintentions. 15 Inanothercase,he denouncedanAmericanproductionof Endgame becauseitwassetina subwaystationratherthanthe “bareinterior” hespecifiedinthestage directions.16 Inbothepisodes,hewasobjectingtoaperceivedviolation ofhismoralrightsasanauthortohavehisartisticintentionsaccurately representedintheplaysthatborehisname.

Whilemoralrightsandcopyrightbothprotecttheinterestsof authors,theyareconceivedasprotectingdifferentkindsofinterests. Asconventionalwisdomhasit,copyrightprotectstheeconomicinterestsofauthorsintheproductionanddistributionofcopies,versions,or reproductionsofartworks.Copyri ghtisalienable:itcanbewaived, exchanged,ortransferred.Moralrights,ontheotherhand,areunderstoodasrightsofpersonality:accordingtotheorthodoxview,theyare inalienablebecausetheyfollowfromthe “ presumedintimatebond betweenartistsandtheirworks.”17 (Inpractice,thelegalalienability ofmoralrightsdiffersbycountry.)Therearedifferingaccountsofthis bondinthetheoreticalliterature,b utthebasicideaisthattheartwork isnotjustafungiblepropertyoftheartist,butanextensionofhisorher

14 Forcomprehensivetreatmentsofmoralrightsincaselawandinnon-Western countriesrespectively,seeElizabethAdeney, TheMoralRightsofArtistsandPerformers (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2006);MiraSundaraRajan, MoralRights:Principles, PracticeandNewTechnology (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,2011).

15 MoralRights:Principles,PracticeandNewTechnology,366–7.

16 CharlesRBeitz, “TheMoralRightsofCreatorsofArtisticandLiteraryWorks,” The JournalofPoliticalPhilosophy 13,no.3(2005):340.

17 Rigamonti, “DeconstructingMoralRights,” 355.

veryself. 18 Thisuniquebondentitlesartiststoacertaindegreeof controlovertheirworks,evenwhentheartifactsthatembodythose creationshavebeensoldtoanother.TheWhistlerandBüchellawsuits happentobookendthecentury-longdevelopmentofthelegislation surroundingtheserightsthatbeganinContinentalEuropeandwhich hasbecometheglobalnorm.19 Thedesignationoftheserightsas ‘moral ’ (asopposedtoeconomic thereareno ‘immoral’ rights)points totheideathatanartistretainsaspecialauthorityoverherworksasa matterofherautonomy,becausetheyareseenasanextensionofher personality.

Hence,ifwearetounderstandtheconceptofartisticfreedominits mostfundamentalsense,weneedtohavesomegrasponthenatureof artisticauthorship.Ofcourse,iti snotimmediatelyclearwhyanartist shouldhaveaspecialinterestinhisartworkasopposedtootherthings hemightmake,likebreakfast,adoghouse,orashoppinglist.Wecan beginbypointingoutthewidespreadphilosophicalagreementthat artworksareintentionalobjects.20 BythisImeanthatartworksare deliberatelymadesoastocommunicateorexpresssomeformof meaning.Thisexcludesfromconsiderationasartsuchthingsasnaturallyoccurringphenomena,or paintingsmadebyelephants.21 But sincethedesignation ‘intentionalobjects ’ coversnon-artartifacts the shoppinglistalsocommunicatesacontent wemustseekfurther clari fi cationifwearetounderstandthenatureofthespecialbond betweenartistandartworkthatgivesrisetothelegalrecognitionof moralrights.Weseektounderstandwhatmakesanartworkadifferent kindofthingfromotherkindsofcommunication,suchthatartists

18 “Themoralrightoftheartistisusuallyclassifiedincivillawdoctrineasarightof personality,andinparticularisdistinguishedfrompatrimonialorpropertyrights.Copyright,forexample, isapatrimonialorpropertyrightwhichprotectstheartist’specuniaryinterestintheworkofart.Themoralright,onthecontrary,isoneofasmallgroupof rightsintendedtorecognizeandprotecttheindividual’spersonality.Rightsofpersonality includetherightstoone’sidentity,toaname,toone’sreputation,one’soccupationor profession,totheintegrityofone’sperson,andtoprivacy.” Merryman, “TheRefrigeratorof BernardBuffet,” 408.

19 Rigamonti, “TheConceptualTransformationofMoralRights.”

20 ChristyMagUidhir, ArtandArt-Attempts (OxfordUniversityPress,2013),2–3.

21 Thisnecessaryconditionofintentionalitydoesnotentailthattheobjectwasmade withtheintentionthatitbeanartworkinourmodernsenseoftheterm,forthiswould excludepremodern,non-Western,orOutsiderartifactsthatwevalueasartworks.

arepresumed,bothculturallyandlegally,tohaveaspecialinterestin theirworks.Suchalineofinquirythreatenstoleadusdownthe philosophicalrabbitholeofthe ‘ whatisart? ’ question,which Ideclinetodo.Mytheoryofartisticauthorshipdoesnotdependon anyparticularde fi nitionofart,andthereaderisinvitedtosupply whicheveraccountshe fi ndsmostplausible.

Inwhatfollows,Igiveabriefoverviewofthehistoryofourcontemporaryunderstandingofauthorshipasaformofintellectualproperty. Ithenturntothetwodominantaccountsofartauthorshipinthe relevantscholarshippertainingtoartisticfreedomandmoralrights: thelegalandthephilosophical.Eachcapturessomethingimportant aboutourintuitionsandvaluessurroundingartauthorship,butboth ultimatelyfailtoaccountforthenatureofthebondbetweenauthorand work.Ithenpresentmydual-intentiontheoryofartisticauthorship,in whichIarguethatauthorshipentailstwomomentsofintention.The artworkisnotonlyintentionallymade,butmustalsoberatifiedand affirmedbytheauthorasfulfillingherartisticandexpressiveintentions. Itisinthissecondmomentthatartisticfreedomandtheownership relationthatgroundsmoralrightscanbefound.

III.TheModernAuthor

AsHickhaspointedout,authorialrightsrestonametaphysicaldistinctionbetweentwokindsofpropertythatcaninhereinoneandthesame object:thematerialartifactandtheimmaterial,intellectualcontentthat itexpresses.22 We findthismaterial/immaterialdistinctionrepeatedyet againwithinthelegalrealmofauthors’ rights:whilecopyrightissaidto protecttheeconomicrightsofartistsintheircreations,moralrightsare frequentlyunderstoodasnon-economicrightsof ‘personality.’23 Andyet itisfarmoredifficulttodisentangletheeconomicandthenon-economic aspectsofartworksthanthedistinctionbetweencopyrightandmoral rightswouldmakeitseem.Infact,theyarepractically,conceptually,and

22 Hick, “ExpressingIdeas:AReplytoRogerA.Shiner,” 407.

23 JohnHenryMerryman,AlbertE.Elsen,andStephenK.Urice, Law,Ethics,andthe VisualArts,Fifthed.(AlphenaandenRijn,TheNetherlands:KluwerLawInternational, 2007),422.

historicallyboundtogether.AsRigamontiexplains,moralrightslegislationhasalwaysbeenlinkedtocopyright:

Thedecision[byFrance,Germany,Italy]toinsertmoralrightsintothecopyright statuteswasnotasimpleaccidentoramatterofpurelegislativeconvenience,but insteadtheexpressionoftheideathatmoralrightsarerightsofauthorsintheir worksandthereforeoughttobeformallyregulatedasapartofcopyright law Itispreciselytheformalandconceptualunityofmoralandeconomic rightsasrightsofauthorsintheirworksthatistheessenceofthe ‘droitd’auteur’ approachtocopyright,whichisgenerallyviewedasthedefiningfeatureof ContinentalEuropeancopyrighttheory.24

Copyrightlawsaroseatatimewhenagrowingmarketforprintedbooks madeitpossibleforauthorstomakealivingfromtheirwork.25 Butin additiontotheseeconomicandsocialchanges,theconceptionofauthorshipuponwhichcopyrightisbasedrequiredatheoreticalshiftaswell. Whilewemaytakeitforgrantednow,theideaofintellectualpropertyis arelativelyrecentdevelopment.AsWoodmanseeputsit, “Thenotion thatpropertycanbeidealaswellasreal,thatundercertaincircumstancesaperson’sideasarenolesshispropertythanhishogsandhorses, isamodernone.”26 Itaffirmstheideathatauthors’ contributions,even whenidealandimmaterial,areneverthelesssubstantive.Ittransformed theunderstandingofauthorsaspassivevehicles,eitherofdivineinspirationoroftraditionalskills,andreplaceditwiththenotionthatauthorshipinvolvestheuniquecontributionoftheauthor’sselfinthework.27 Asanotherhistorianofcopyrightputsit, “Theattempttoanchorthe notionofliterarypropertyinpersonalitysuggeststheneedto finda transcendentsignifier,acategorybeyondtheeconomictowarrantand groundthecirculationofliterarycommodities.”28 Inotherwords,the claimthatauthorshadarighttoeconomiccompensationfortheir intellectuallaborrequiredatransformationintheunderstandingof whatthatlaborwas.Bothcopyrightandartisticmoralrightsarerooted intheideaofintellectualproperty.

24 Rigamonti, “DeconstructingMoralRights,” 360.

25 MarthaWoodmansee, TheAuthor,Art,andtheMarket:RereadingtheHistoryof Aesthetics (NewYork:ColumbiaUniversityPress,1994),36.

26 Seeibid.,42. 27 Ibid.,36.

28 MarkRose, AuthorsandOwners:TheInventionofCopyright (Cambridge:Harvard UniversityPress,1993),128.