Introduction

AppropriatingHobbesinContexts

HobbesmighthavesatforaportraitofPlato,andis,Ithink,thebestlookingphilosopherknowntome.1

Insteadofseeing Leviathan asatextthatworkedto fixHobbes’sidentity, itmightbebettertoseeitasatextthatworkedtoconfoundawholerange ofprejudicesaboutthecharacterofhisproject.2

Thefactthatthehermeneuticaltaskcanneverbecompletedentailsthatthe meaningcontainedwithintexts,monuments,andfragmentsisconstantly rebornthroughlifeandisforevertransformedinachainofrebirths.3

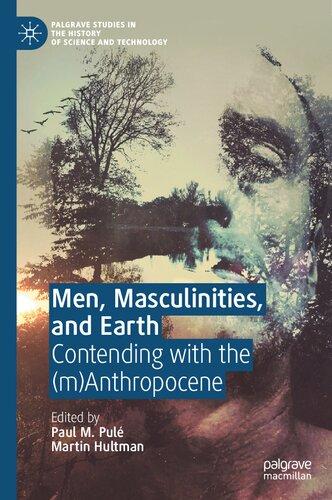

WhathasbeensaidofMachiavellimaywithequalvaliditybesaidofThomas Hobbes,namelythatheis ‘achameleon:hetakesonthecolorationofhis critics’ . 4 Hobbes’snamehasbecomesynonymouswithsomanyvividimages thatthevocabularyofpoliticsandinternationalrelationswouldbeimpoverishedwithoutthem.Hischaracterizationofthestateofnatureasawarofall againstall;thelifeofmansolitary,nasty,brutish,andshort;thenecessity foranall-powerfuldomesticabsolutesovereign;andtheinternationalrealm anarchicanddevoidofhumanity,whereforceandfraudistheprudentcourse tonavigate,areallcharacterizationsendlesslyrepeatedandgiventheprefix Hobbesian.Somuchsothatforexilesfromaturbulentwar-torntwentiethcenturyEuropehebecameafellowColdWarriorwithhis fingeronthe pulseofwhatpoliticswasallabout: ‘thephilosopherofpowerparexcellence’ . 5

1 SirLeslieStephen, Hobbes (London:Macmillan,1928[firstpublished1904]),64.

2 JonParkin, TamingtheLeviathan:TheReceptionofthePoliticalandReligiousIdeasof ThomasHobbesinEngland1640–1700 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2007),101.

3 EmilioBetti, ‘HermeneuticsastheGeneralMethodologyofthe Geisteswissenschaften ’,in HermeneuticsasMethod,PhilosophyandCritique ,ed.JosefBleicher(London:Routledge andKeganPaul,1980),69.

4 J.H.Geerken, ‘Machiavelli:Magus,TheologianorTrickster?’ MachiavelliStudies,vol.3 (1990),95.

5 CarlJ.Friedrich, TheAgeofBaroque (NewYork:Harper,1952),27.

Therecanbefewscholarswhowouldnotmodifythis ‘realist’ evocationof Hobbesbyaddingqualificationsandnuancesthatliftthemistfromthisbleak Hobbesianlandscape,yettheimageryistooalluringtodiscardentirely,evenif thenecessityforqualificationormodificationisoftenrelegatedtofootnotes.6 It maybetoolatenowtoinfluenceorchangetheemblematicHobbes.Hewastoo greatanexponentofrhetorical flourishandmasterofoverstatementforhis owngood.

Hobbeshasbecomesomethingofacaricature,anemblematicstrawman, whomaybecasuallyinvokedtorepresentextremepositionsin,forexample, politics,law,andinternationalrelations.Inpoliticsheistypicallytheapologist forabsolutemonarchyinwhichpowerandauthorityareinseparable;inlaw, heisthearchetypalproponentoflegalpositivismequatingthelegitimacyof lawwiththecommandofasuperior;and,ininternationalrelations,heisthe archrealisttheoristofanarchy.Thereisnothingintrinsicallywrongwith populatingthelegendarylandscapewithemblematic figureswhoactassymbolsonthemaptohelpusnavigatecomplexandconfusingterrains.We cannotlegislateagainstit,butbeingawareofitstenuouscharacterhelpsusto appreciatethatthemanandhisworksarewhathehascometorepresent, ratherthanwhatisintrinsicor ‘fixed’ inthetext.

Theaimofthisbookisnottotracethechangingfortunesoftheinterpretation ofoneofthemostsophisticatedandfamouspoliticalphilosopherswhoever lived,butinsteadtoglimpsehereandtherehisplaceindifferentcontexts,and howhisinterpretersseetheirownimagesreflectedinhim,ordefinethemselves incontrasttohim.AhistoryofthereceptionofHobbesoverthecenturiesis certainlyworthwhile,andthereareanumberofattemptstotracehowdifferent audienceshavereactedtohisthoughtinstrictlydelimitedperiodsoftime.7

InthisintroductionIbeginbylocatingHobbesinhisowntime,andgivean indicationofthevarietyofsubsequentinterpretations,attemptingtoexplain thephenomenonwithreferencetohermeneutics,contendingthatthrougha processofdistanciationhiswritingshavebeenappropriatedandcommandeeredtodoserviceindivergentcontextsovertime.Iwanttoexploreand explicatetheimportanceofcontextsinreadingandunderstandinghowand whyparticularinterpretationsofHobbeshaveemerged.Thereisnoone perfectcontextthatenablesustogetatwhatHobbesreallymeant,because hebecomesalmostindistinguishablefromthecontextinwhichheisread.

6 NicholasRengger, JustWarandInternationalOrder:TheUncivilConditioninWorld Politics (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2013),ix,x.

7 JohnBowle, HobbesandHisCritics:AStudyinSeventeenthCenturyConstitutionalism (London:JonathanCape,1951);Parkin, TamingtheLeviathan;NoelMalcolm, ThomasHobbes Leviathan.1.Introduction (Oxford:ClarendonPress,2012),146–58.Forageneraloverviewof idiomsofHobbesinterpretationseeW.H.Greenleaf, ‘Hobbes:TheProblemofInterpretation ’ , in HobbesandRousseau: ACollectionofCriticalEssays,ed.MauriceCranstonandRichard S.Peters(NewYork:DoubledayAnchor,1972),5–32.

Iillustratethecapacityofatexttotakeonthecolourationofitssurroundings withreferencetorationalchoicetheory.I finishbybrieflyindicatingthe varietyofHobbesianinterpretations,outliningtheorderofenquirypursued inthisvolume.

BIOGRAPHICALSKETCH

HobbeswasbornprematurelyonGoodFriday,5April1588anddiedatthe ageof91on4December1679.Heclaimsinhisverseautobiography,with dramaticeffect,thatitwastherumouroftheimminentthreatoftheSpanish Armadathatprecipitatedhispetrifiedmother ‘tobringforthTwinsatonce, bothMe,andFear’ 8 Hislonglifeencompassedthemosttumultuoustimesin modernhistory.Intheyearsbeforehewasborntheseedsofsubsequent conflictsweresown.MaryIofEngland,whoreignedfrom1553to1558, reversedtheconsolidationoftheProtestantfaithpursuedduringtheshort reignofherbrotherEdwardVI(1547–53)byrestoringpapalauthorityand abjuringtheActofSupremacythatherfather,HenryVIII,institutedin1534. Marypresidedovertheburningof280religiousheretics.ElizabethI,in1559, reassertedthesupremacyoftheChurchofEngland.Duringthelatterpartof Elizabeth’sreignParliamentgrewincreasinglyinconfidence.Religiousand politicalintrigueswerethewatermarkthatranthroughthemachinationsover whichHobbes’slifespanned.WiththeendoftheTudorline(1603),JamesVI ofScotland(andIofEngland)heraldedtheStuartsuccession,onehead presidingovertwokingdoms.

Hobbes,likeJames,intenselydislikedPresbyteriansbecausetheyagitated forsignificantchangestotheChurchofEngland,includingtheabolitionof episcopacy,andtheintroductionofademocraticformofchurchgovernment. Hobbes’sobjectionwasthatthePresbyterians,aboutwhomheisdismissivein Leviathan,wishedtosubordinatetheauthorityofthekingtochurchcouncils. OntheeveoftheCivilWarwhenabolitionwasonceagainbeingdiscussed Hobbesconcededthatalternativeformsofchurchgovernancemaybeacceptable,andduringtheinterregnumhesupportedindependency,thatis,relativelyautonomouscongregations.Episcopacywassuspendedin1642and abolishedin1646.9

JamesIhadnopatiencewithconstitutionalconstraints,andwasoneofthe principalexponentsofthedoctrinethatsubjectsmustobeythecommandsof theirmonarch,exceptincontradictionofGod,andeventhentheycouldnot

8 ThomasHobbes, TheLifeofThomasHobbesofMalmesbury (Exeter:Rota,1979).

9 A.P.Martinich, ‘ThomasHobbesinStuartEngland’,in AHobbesDictionary,ed.A.P.Martinich (Oxford:Blackwell,1995),2–3,and13. Introduction:AppropriatingHobbesinContexts 3

activelyresisthim.Jamesarguedinhis TheTrewLawofFreeMonarchies,the mostabsolutistofhiswritings,thattheking’spoweroverthekingdomwas comparabletothatofGod’sintheuniverse,andthereforenosubjecthadthe righttolimitorresistthewillofthesovereign.Tyrants,althoughevil,were similarlyabsolute,andsentbyGodasinstrumentstopunishwickedpeoples. Nevertheless,James,asHobbeswastodoinhisownpoliticaltracts,gave considerableemphasistothedutiesofrulers.10 Hobbeswasalsoatone ‘with ourmostwiseKingJames’11 inobjectingtotheviewsofCardinalBellarmine,whoarguedthatthepopehadauthoritytodeposemonarchs.12 Neitherthepopenorhisbishopshavejurisdictionwheretheyarenotcivil sovereigns.Hobbesarguesthatjurisdictionisthepowertohearanddeterminedisputesbetweenmen,anddoesnotbelongtoanyonewhodoesnot ‘haththePowertoprescribeRulesofRightandWrong;thatis,tomake Laws;andwiththeSwordofJusticetocompelmentoobeyhisDecisions.’ 13 LikeKingJames,HobbesrejectedtheviewofChiefJusticeEdwardCokethat thecommonlawstandsabovetheauthorityoftheking.14 Hobbesargues thatthereisnouniversalreasonagreeduponinanynation,andinthe absenceofwhich ‘ourKingistoustheLegislatorbothofStatute-Law,and Common-Law’ . 15

JamesIwassucceededbyCharlesIin1625untilhisexecutionin1649. HispoliciesimmediatelyexhibitedcontemptforParliamentandeventually precipitatedthetwocivilwars.Forexample,hefoundhimselfattheoutsetin disputeover financingintendedwars,andwasforcedbyParliamentin1628 toconsenttothePetitionofRight,introducedbyEdwardCoke,beforeit waspreparedtoappropriatemoney.ThreeyearsintoCharles’sreign,when increasinglytheKingwaschallengedby ‘democratic’ tendencies,Hobbes’ s royalistinterestsinwar,civilwar,andpoliticsbecomesevident.In1629,the yearCharlesIdissolvedParliamentandruledforelevenyearsalone,heputhis classicalscholarshipinLatinandGreek16 togoodeffectwiththepublicationof histranslationofThucydides’ HistoryofthePeloponnesianWar inwhich manyoftheobservationshemakesabouthumannatureandpsychologyform

10 KingJamesVIandI:PoliticalWritings,ed.J.P.Sommerville(Cambridge:Cambridge UniversityPress),64and80.

11 ThomasHobbes, Leviathan,ed.RichardTuck(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1991), firstpublishedAprilorearlyMay1651,p.138[101].Originalpaginationinparentheses.

12 JamesVI, PoliticalWritings,e.g.85,98–9,108–19,and129–30.

13 Hobbes, Leviathan,391[311]–392[311].

14 James,VI, PoliticalWritings,261.

15 ThomasHobbes, ADialogueBetweenaPhilosopherandaStudent,oftheCommonLawsof England,inThomasHobbes, WritingsontheCommonLawandHereditaryRight,ed.Alan CromartieandQuentinSkinner(Oxford:ClarendonPress,2005).

16 HobbesbeganlearningLatinandGreekattheageofsixatWestportchurchschoolandat eightcontinuedhisstudiesinGreekunderRobertLatimer,aGreekscholar,ataprivateschoolin Malmesbury.

thebasisofhislaterpoliticalwritings.17 InhisverseautobiographyHobbes suggeststhatThucydidestaughthim ‘Democracy’safoolishthing.Thana republicwiserisoneking.’18 HeagreedwithThucydidesthatthepurposeof thehistorianwastoselectsignificantlessonsfromthepasttoinformpresent conduct,andguidefutureprovidence.Thucydides,forHobbes,wasthemost politicallyconscioushistorianwhohadeverwritten.

AtatimewhenHobbeswasimmersedinscientificstudieshewasdistracted in1637,onhisreturntoEnglandfromthecontinent,bytheshipmoneycrisis whichbroughttotheforetheextentoftheKing’spower.TheKing’snormal powerscouldbeextendedinexceptionalcircumstances,anditwastheKing himselfwhowastobethejudgeofthosecircumstances.Shipmoneywasone ofthetaxeshecouldlevyinexceptionalcircumstanceswithouttheconsentof Parliament.JohnHampden,aparliamentarian,rosetonationalfamein1637 forrefusingtopaythetax.AlthoughtheKing’srighttoimposethetaxwas upheld,adversepublicopinionforcedHampden’sreleasefromprison.

Between1637and1640,thetimeoftheShortParliament(13Aprilto5May 1640)whichCharlesIdissolvedbecauseoftheimminentdebateoverthe deterioratingpositioninScotland,theresultofArchbishopLaud’sattemptto imposetheAnglicanliturgyontheScottishPresbyterians,Hobbesbegan thinkingaboutasystematicexpositionofhisphilosophy.Hetentativelybegan withamaterialisticmetaphysicwhichwastobedevelopedandpublishedin 1655as DeCorpore,theconclusionsofwhichwereappliedtoman,published in1658as DeHomine.His findingsinmaterialisticmetaphysics,andnatural philosophy,however,wereearlierappliedtotherightsanddutiesofmenas citizensincivilsociety,whichhepublishedwhileinexileinParisin1642as DeCive,astheCivilWareruptedinEngland. DeCive wasaLatinandexpanded versionofpartof TheElementsofLaw,composedin1640,19 andwhichsurfaced in1655as DeCorporePolitico. 20 TheElementsofLaw standsasHobbes’smost succinctstatementofthemainlinesofhispoliticalphilosophy.21

17 ThomasHobbes, Thucydides,HistoryofthePeloponnesianWar,trans.ThomasHobbesin TheEnglishWorksofThomasHobbes,vol.VIII(London:Bohn,1843).Therelationshipis exploredfullyinChapter6.

18 ThomasHobbes, ‘VerseAutobiography’,in LeviathanwithSelectedVariantsfromthe LatinEditionof1668,ed.EdwinCurley(Indianapolis,IN:Hackett,1994),liv.

19 NoelMalcolm, ‘ASummaryBiography’,in AspectsofHobbes (Cambridge:Cambridge UniversityPress,2002),14–15.

20 RichardPeters, Hobbes (Harmondsworth:Penguin,1967),28.Thesignificantdatesareas follows, ElementsofLaw,EnglishMs,1640,andpublishedinEnglish1650(London); DeCive Latin1642(Paris),English1651(Amsterdam); Leviathan,English1651(London),Latin1668 (Amsterdam); DeCorpore Latin,1655(London),English,1656(London).SeeJ.C.A.Gaskin, ‘Introduction’ , TheElementsofLaw:HumanNatureandDeCorporePolitico (Oxford:Oxford UniversityPress,1994),xliv.

21 ItwasinthesecondLatineditionof DeCive,1647,towhichHobbesadded ‘APrefaceto theReader’,thattheorderofphilosophicalstudiesoutlinedabovewassuggested.Themannerof enquirydidnothavetoproceedsequentiallybecausethemethodheemployedwasboth

Hobbeshad fledtoParisin1640,wheresixyearslaterhebecameacquainted with,andtutored,thePrinceofWales,thefutureCharlesII.In1641theEarl ofStrafford,CharlesI’ sclosestadvisor,wasimpeachedandexecuted.The LongParliament(1640–60)wasalsoatpainstocondemnroyalistswho preachedabsolutemonarchy.Theseeventsleadinguptoandduringthe civilwarsimpresseduponHobbesnotonlythecatastrophicconsequences ofdissentandcivilwar,butalsothefollyofimprudent,precipitous,and incautiousrule. 22

Itwasin TheElementsofLaw,1640,thatHobbeselaboratedtheremarkshe madeinhisintroductiontoThucydides.Basinghisargumentonhuman psychologyhemaintainedthatitwasinthenatureofsovereigntyandthe reasonsforinstitutingitthatabsoluterulewasanecessity.Themanuscript wasprivatelycirculatedbutnotpublished,untiltenyearslaterastwoseparate treatises,underthetitles OfHumanNature and DeCorporePolitico.

Duringthecourseofthetwocivilwarsabout100,000Britishmenwere killed,about10percentoftheadultmalepopulation.Thousandswereinjured andmaimed.Citiesweresacked,andcathedrals,churches,andlibrarieswere destroyed.InIrelandmanythousandsofpeopleweremassacredbyCromwell’sarmy,orsimplydiedofstarvation.23 TheinterregnumofOliverand RichardCromwell,1648–60,beganaspeacebrokeoutinEurope,endingthe ThirtyYears’ War,thedevastationofwhichHobbeshadwitnessedduringhis residenciesonthecontinent.TheThirtyYears’ Warhasbeendescribedas moredestructivethananythathadgonebeforebecauseofmoderninnovationsinmilitarydisciplineandstrategy.24 Thewarcausedeconomicdevastation.InGermanyaloneitspopulationdeclinedbetweenoneandtwothirds duringthewar.Itcametoanend,notbecauseofmilitarydefeat,butbecause theenduranceofthepartieshadbeenstretchedtoitslimits.25

ThePeaceofWestphaliawhichhasbecomeemblematicininternational relations,whilenotestablishingtheprincipleofstatesovereignty,atleast synthetic,dependingonreasoning,and ‘analytic’,relyinguponsenseexperience,orintrospection.Gaskin, ‘Introduction’,xvi–xvii.

22 ThomasHobbes, BehemothorTheLongParliament (Chicago:ChicagoUniversityPress, 1990).Themanuscriptwascompletedabout1668,butalthoughpiratededitionsappearedinthe late1670s,anauthorizededitionwaspublishedposthumouslyin1682.

23 MauriceAshley, CharlesII:TheManandtheStatesman (London:HistoryBookClub,1971), 7–9;CharlesWilson, England’sApprenticeship1603–1763 (London:Longmans,1971),108;Trevor Royle, CivilWar:TheWaroftheThreeKingdoms1638–1660 (London:Abacus,2005).

24 GuntherE.Rothenberg, ‘MauriceofNassau,GustavasAdolphus,RaimondoMontecuccoli andthe “MilitaryRevolution” oftheSeventeenthCentury’,in MakersofModernStrategyfrom MachiavellitotheNuclearAge,ed.PeterParet(Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress,1986), 32–63.

25 KaleviJ.Holsti, PeaceandWar:ArmedCon fl ictandInternationalOrder1648–1989 (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,1991).

Introduction:AppropriatingHobbesinContexts 7

paveditsway.26 ItwasduringtheinterregnumthatHobbes’smostfamous politicaltract,theEnglishversionof Leviathan,waspublishedin1651,when Hobbesplayfullysuggestedhehadamindtobehome.27 Itfollowedcloseon theheelsofthepublicationin1650–1oftwopartsofhisearlier Elementsof Law as HumanNature and DeCoporePolitico.TheEnglishversionof DeCive (TheCitizen)hadbeentranslatedintoEnglishin1651underthetitleof PhilosophicalRudimentsConcerningGovernmentandSociety. Leviathan was theresultofHobbes’slongprocessofconsideringthenecessaryconditions forastablesociety.Inithepropoundedapoliticaltheorythatostensibly groundedpoliticalobligationinconsent,whichcouldnotbewithdrawnunless themonarchwasunabletofulfilitsprincipalfunctionofgoverningeffectively. Ifthisconditionwasnotmetthesubjectcouldlegitimatelysecurehisorher lifebysubmittingtoarulerwhocouldprovideprotection.Inotherwords, Hobbesputforwardthedefactojustificationofpoliticalobligation,which accountsforwhyhewasabletoreturntoEnglandandpresenthis Leviathan toOliverCromwellwithoutrecrimination.Despitethis,in1660therestored monarchCharlesIIwelcomedHobbestohiscourtandgrantedhimasmall pension.Hobbescommentsinthethirdperson: ‘hewasblessedintheopenhandednessofhispatrons,andparticularlyfavouredbythegenerosityofKing CharlestheSecond’ . 28 Twootheraspectsofthe Leviathan mayaccountforthis. ItincludesastrongdefenceagainstthoseParliamentarianswhohadmaintained thatthelawsofEnglandarepartofanancientconstitutionthatconstitute theCommonLaw,andwhichhaveanauthorityindependentofthesovereign. Itwasthesovereign’swillthatgavelegitimacyandauthoritytolaw,notthe higherreasoningpowersofthecommonlawyers.Furthermore,hemaintained thattheChurchshouldnotbearivaltothestate,butsubordinatetoit.

Hobbes’sownaccountofthecivilwarsandinterregnumisinformedbythe principleshedevelopedinhispoliticalphilosophy.Hecompleteditin1668, butwiththeexceptionofsomepiratededitionsinthelate1670s,itwasnot authorizeduntil1682becauseCharlesIIrefusedtoissuealicense,probably becauseof Behemoth’sexplicitanticlericalism.Themoststrikingconclusionat whichHobbesarrivesis ‘Thepowerofthemightyhathnofoundationbutin theopinionandbeliefofthepeople’ . 29 Inotherwords,therulerderiveshis righttogovernfromtheauthorityofthoseoverwhomherules,andthelesson

26 DavidBoucher, ‘ResurrectingPufendorfandCapturingtheWestphalianMoment’ , Reviewof InternationalStudies,vol.27(2002).AndreasOsiander, TheStatesSystemofEurope,1640–1990: PeacemakingandtheConditionsofInternationalStability (Oxford:OxfordUniversityPress,1994), andD.Croxton, Westphalia:TheLastChristianPeace (London:Palgrave,2016).

27 Malcolm, ‘ASummaryBiography’,19.

28 ThomasHobbes, ‘TheProseLife’,in TheElementsofLaw,ed.Gaskin,253.Aubreysuggests thatKingCharles ‘alwaysdelightedinhiswitandrepartees’.Aubrey, ‘BriefLife’,in TheElements ofLaw,ed.Gaskin,237.

29 Hobbes, Behemoth,16.

ofthecivilwarwasthattheseditiousopinionsofrepresentativesofreligious institutions,alongwithlegal,educational,military,andordinarycitizens fomentrebellionanddestroythestate.Beliefintheking’sauthoritywas underminedfromallsides,includingfromthepeoplethemselveswhofailed tocomprehendtheirimperativedutytoobeytheking.30

Farfromtheportraitofautilitymaximizerthatrationalchoicetheorists paintHobbes’scharacterizationofhumannature,in Behemoth heemphasizes towhathehadalreadyintroducedusinhispoliticalphilosophy;thegullible, duplicitous,destructive,andrecklessrisk-takingopportunistcharacterof man,readytofollow ‘impudenceandvillainy’,andperpetuallysusceptibleto ‘flattery’ . 31 Becauseonehasthepowertooverthrowtheking,doesnotgiveone theright(authority)todoso.Onlythekingcanrenouncehisright.32 This,of course,isnotentirelyconsistentwiththeviewoutlinedabovethatHobbeswas adefactotheoristofpoliticalobligation,thatis,allegianceisowedtowhoever iscapableofprotectingus.33

TheRestorationwasnotwithoutsocialunrestandsuspicion,withthefear ofthereturnofCatholicismconstantlyagitatingtheProtestantestablishment, culminatingafterHobbes’sdeathin1679,intheconversionofJamesII,and ultimatelyhisdownfallintheGloriousRevolutionof1688,followedbythe accessionofWilliamIIIoftheHouseofOrangeandMaryII,daughterof JamesII.

Hobbes’sexperiencepriortohisexilein1640wasnotconfinedtoEngland. InallHobbestravelled,orlived,fourtimesonthecontinent,totallingalmost twentyyears,mainlyinFrance,butalsoinGermanyandItaly.Duringhistime onthecontinentHobbeswasacquaintedwith,ormixedinthehighest philosophicalandscientificcircles.Althougharatherdesultorystudentat MagdalenHall,Oxford(1603–8),thelittlescholasticismandnaturalphilosophyhehadabsorbedwasheldincontemptandwaschallengedfromall directions.Hehadtravelledtothecontinentonathree-yeartourasthe companionandtutorofWilliamCavendish’seldestsonin1610,which inspiredHobbestoreignitehisliterarystudiesandperfecthisGreekand Latin,34 onhisdiscoverythattheAristotelianismwhichhehadbeentaughtas astudentwasnowdiscreditedbythelikesofKepler’ s AstronomiaNova publishedin1607.Again,asthetutorofthesonofSirGervaseClifton,Hobbes returnedtothecontinentin1629.Itwasthenheencounteredforthe firsttime, attheageof41,Euclid’sgeometry,whichhadaprofoundandlastinginfluence

30 Hobbes, Behemoth,4. 31 Hobbes, Behemoth,86and110.

32 Hobbes, Behemoth,74and178.

33 QuentinSkinner, ‘ConquestandConsent:HobbesandtheEngagementControversy’,in QuentinSkinner, VisionsofPolitics,vol.III, HobbesandCivilScience (Cambridge:Cambridge UniversityPress,2002),287–307. Behemoth,ofcourse,waswrittenduringthereignofCharlesII anditspublicationhadtobelicensedbyhim.

34 Hobbes, ‘TheProseLife’,246.

onhisphilosophicalreasoning.Itisnowwellestablished,however,thatthe politicalconclusionswhichHobbescouchedinthegeometricmethodpredate hisdiscoveryofEuclid. 35 Hereturnedtothecontinent,withthethirdEarlof Devonshire,between1634and1636.Hehadbecomehistutorin1631atthe requestofthewidowofhisformerpupilthesecondEarlofDevonshire,who hadbeenhisfriendandclosecompanionfortwentyyears. 36 Itwasduring thistimethatheencounteredthegreatnaturalphilosopherswhowere systematicallyreconstructingscience.HebecameafrequenteroftheintellectualcirclesurroundingtheAbbéMersenne,whichincludedDescartesand Gassendi.HobbestravelledtoItalyin1636tovisitGalileo,whoattained fameforrevolutionizingnaturalphilosophy.37

In1660theRoyalSocietywasestablishedinBritain,andin1662itbecame formallyincorporated,butHobbesneverreceivedaninvitationtojoinits fellowship.Hobbeswasdeeplywoundedbythesleight,complainingbitterly thatsomeofitsmembers,suchasJohnWallisandRobertBoyle,withwhom hehadbeenindispute,werehisenemies.However,Hobbeswasviewedasa dogmaticcontroversialistwhomaybringthesocietyintodisrepute,andwhose absence,whileregrettable,wascertainlyagreeable.Speculationastothe reasonsforhisexclusioncontinue.Ithasbeensuggestedthatinitsearly daystheRoyalSocietywasmoreofagentleman’sclubthanaprofessional society,andtherewaslittleenthusiasmtoencourageanirascibleclubbore.He was,however,consideredapersonofsoundscientificmind,andhadmany friendsamongthefellowship.Itmaythereforehavebeenthestigmaattached tohimbyreputationregardinghisirreligiositythatpreventedhiselection.38

Hobbeswasacontroversialphilosopher,exhibitinglittleofthefearhe claimedinherentinhisnature,whenpropoundingprovocativedoctrinesat variancewiththoseoftheestablishment.Hewasfrequentlyattackedforhis allegedatheismandmoralrelativismduringthe1660sand1670s.39 Hewasnot averse,however,todisavowinghisopinionswhencalledtoaccount.Therewere seriousenoughrumoursofthepossibilityofHobbesbeingindictedforheresy, togalvanizehimintodestroyingsomeofhismoreincriminatingpapers.40 In

35 MostfamouslybyLeoStrausswhoattemptedamoresystematicexplorationbuildingon theremarksofG.C.Robertson.Strauss, ThePoliticalPhilosophyofHobbes:ItsBasisandGenesis (Chicago:ChicagoUniversityPress,1952[firstpublished1936]);andGeorgeCroomRobertson, Hobbes (Edinburgh,Blackwood,1901),57.

36 Robertson, Hobbes,26. 37 Peters, Hobbes,21.

38 QuentinSkinner, ‘HobbesandthePoliticsoftheEarlyRoyalSociety’ , VisionsofPolitics, vol.III, HobbesandCivilSociety (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2002),324–45.Noel MalcolmtakesadifferentviewbasedonHobbes’sincreasinglycontroversialreligiousand politicalreputationtowardstheendofthe1650sandbeginningofthe1660s, ‘Hobbesandthe RoyalSociety’ , AspectsofHobbes,317–35.Cf.Malcolm, ‘ASummaryBiography’,23.

39 S.Mintz, TheHuntingofLeviathan (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2017).

40 JohnAubrey, ‘BriefLives’,ChieflyofContemporaries,SetDownbyJohnAubrey,Between theYears1669–1696,ed.AndrewClark,2vols(Oxford:ClarendonPress,1898),I,394.

1666Hobbes’ s Leviathan wascitedinconnectionwiththeintroductionofabill againstatheismandprofaneness,andin1668–9hebecameinadvertently embroiledinadisputeoccasionedbyDanielScargill,whodefendedatCambridgeUniversityanumberofHobbesianpropositionswhichhelaterrecanted. Hobbes’sdiscussionsofheresyin ADialoguebetweenaPhilosopheranda Student,oftheCommonLawsofEngland,andespeciallyhiscriticismofEdward Coke’sattitudetowardsthelawofheresy,betrayhishostilitytocommonlaw judicialprecedentsandthepoliticalassertionsofcommonlawyersclaiming authorityindependentlyoftheKing.Hefearedthatsuchlawyersmayposea threattohisownsafety.41 Permissionwasrefusedin1670forthereprintingof Leviathan andOxfordUniversityandtheRomanCatholicChurchproscribed thereadingofHobbes’sbooks.Hediedin1679andafewyearslaterOxford Universitypubliclyburntcopiesof DeCive and Leviathan 42

THEAUTHORANDDISTANCE

Agreatdealofthephilosophicalliteratureconsideringtheargumentsof Hobbesinterpretnotonlywhathesays,butalsothe ‘truth’ ofhisarguments. Inotherwords,someinterpretersbelievethatwecanchoosebetweenthe philosophicalandcontextualist,orhistorical,studyoftexts.Kavka,for example,suggeststhatHobbes ’ s ‘insightsonmoralsandpoliticsareastrue asthoseofanyphilosopher’,andaddsthatifheistobetakenseriously todayhisargumentsmustbemodifiedinvariousways.Particularlywemust rejectHobbes’ sthreebasicassumptions;thathumanactionsaremotivated solelybyself-interest;thatthesovereign’sinterestswillcoincidewiththose ofthepeople;and,divisionof,orlimitationsonsovereignpowerinevitably leadtowar.43 Otherscontendthatthemeaningofargumentsmaybe achievedbyphilosophicalanalysisofthetexts,independentlyofhistorical andcontextualconcerns.HowardWarrander,forinstance,declaresthathe waslessconcernedwithhowHobbes ’ s ‘theoryoriginated,orhowitistobe explained,thanwiththepriorquestionofwhathistheoryis ’ . 44 While

41 AlanCromartie, ‘Introduction’ , ThomasHobbes:WritingsonCommonLawandHereditary Right,ed.AlanCromartieandQuentinSkinner(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress,2005), xlv–lxii.

42 BernardGert, Hobbes (Cambridge:Polity,2010),1.

43 GregoryS.Kavka, HobbesianMoralandPoliticalTheory (Princeton,NJ:PrincetonUniversityPress,1986),xii.

44 HowardWarrander, ThePoliticalPhilosophyofHobbes:HisTheoryofObligation (Oxford: ClarendonPress,1957),ix.MorerecentlyS.A.Lloydassertsthatthephilosophicalinterpretation ofthemeaningof Leviathan isattainablelargelyindependentlyofhistoricalconsiderations. Ideas

F.C.HoodproudlyannouncesthathisinterpretationofHobbesisbased ‘solelyonthetexts’ . 45

Historicalconsiderations,whilenotcompletelydevoidofcondemnatory tones,aremoreapttosuspendjudgementsaboutthetruthofanargument infavourofunderstandingitsefficacyinrelationtothecontextsinwhich theywereformulated.DeborahBaumgoldwarnsthatweseriouslymisunderstandHobbesifwedonotrealizethatmanyofhisargumentsforthe politicalcovenantwerenotmerelyabstract,butdirectedatunderminingthe justi ficatoryconstitutionalclaimstotherightofresistancebytheparliamentarians. 46 Withthesuccessoftheparliamentarianstheunquestioned assumptionthatEnglandwasahereditarymonarchynolongerheldsway andHobbesmovedfromanabstractargumentforcontractin ElementsofLaw togroundhisprinciplesinhistoricaldetailinthe Leviathan,whichlogically requiredreferencetotheNormanConquest.47 Inaddition,JonParkin,for example,warnsusthatthelargelynegativeviewsaboutHobbes’sabsolutism andtotalitarianism,asurvivalfromseventeenth-centurycriticalcommentary whichportrayedhimasalonerenegade,maybedispelledbecause ‘lookedatin context,Hobbes’sviewsseemalotlessoutlandishthanhiscriticsoftenclaim’ . 48 HobbeshasbeeninextricablylinkedtotheturmoiloftheFrenchWarsof Religionand,inparticular,totheEnglishCivilWar.Whiletheseeventsmay havebeentheoccasionforhisphilosophicalspeculationsonpolitics,formost ofhisinterpretershisconclusionsarebynomeansofrelevanceonlytothose occasions.Hisavowedaimwastoidentifyinparticulartheuniversalpredicamentofmankind.Whenhediscussesobediencetolaws,forexample,itisnot inrelationtomembersofaparticularcommonwealth,buttoanycommonwealth.Itisnotthephilosophicaltheoryofasovereign,butofsovereigntyin whichheisinterested.49

ThecontentionofthisbookisthatinterpretersofHobbesshouldnotbe understoodaspenetratingintotheverydepthsofhismind,butinstead gazingintoamirrorinwhichtheyseetheirownre flectionsastheshadowy presenceofHobbeslooksback.IneachofthecontextsinwhichweencounterHobbes,heacquiresdifferentpersonae,andwhatinoneisregardedof

asInterestsinHobbes’sLeviathan:ThePowerofMindoverMatter (Cambridge:Cambridge UniversityPress,2003),3–4.

45 F.C.Hood, TheDivinePoliticsofThomasHobbes:AnInterpretationofLeviathan (Oxford: ClarendonPress,1964),viii.

46 DeborahBaumgold, Hobbes’sPoliticalTheory (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1988),3–4.

47 DeborahBaumgold, ContractTheoryinHistoricalContext:EssaysonGrotius,Hobbes,and Locke (Leiden:Brill,2010),xi.

48 Parkin, TamingtheLeviathan,2.

49 Hobbes, Leviathan,183[137]. ‘ByCIVILLAWS,IunderstandtheLawes,thatmenare thereforeboundtoobserve,becausetheyareMembers,notofthis,orthatCommon-wealthin particular,butofaCommon-wealth.’

crucialimportance,inanotherisdismissedasirrelevant.Forexample, whereasformodern-dayrealistsininternationalrelations,discussedin Chapter6,Hobbes ’ scharacterizationofthestateofnatureisimportantand significantinordertounderstandtherelationsbetweenstates,fortheclassic jurists,andlegalpositivists,discussedinChapters4and5,Hobbes’sdepictionofhumannatureandthenaturalconditionofmankindborderedonthe ridiculousandprofane.

ThemannerofenquiryIwishtoundertakemaybroadlybecharacterizedas hermeneutic,recognizing,ofcourse,thatthetermencompassesawidevariety ofassumptionsandprocedures.Generallyspeaking,eventhosewhowishto maintaintheautonomyofthetext,thatisan ‘it’ independentofinterpretation, acknowledgethatwhenitcomestoachievinganunderstandingofitsmeaning,textandinterpretationare,indifferingdegrees,extremelydifficult,ifnot impossible,toseparate.Forthosewhoequatethemeaningofatextwiththe psychologyorintentionoftheauthor,therearewaysofmitigatingthe problem.Hobbes,forexample,indiscussinghowlanguageisusedtowork upononeanother’sminds,remindsusthatwordsaretheevidencewehaveof oneanother’sopinionsandintentions,butitisneverthelesswithgreatdifficultythatweunderstandtheirmeaning.Thisisbecausewordsarefrequently usedequivocally,indiversecontextsandinrelationtothecompanyinwhich theyarespoken.Withthepresenceofthespeaker,includinghisorher gestures,wemayinfer,or ‘conjecture’ themeaningofthewords,butthe problemsofinterpretationarecompoundedwhenthetextisseparatedbytime fromtheauthor.Hobbesremarks:

itmustbeextremehardto findouttheopinionsandmeaningsofthosementhat aregonefromuslongago,andhaveleftusnosignificationthereofbuttheirbooks; whichcannotpossiblybeunderstoodwithouthistoryenoughtodiscoverthose aforementionedcircumstances,andalsowithoutgreatprudencetoobservethem.50 Hobbes,then,isacknowledgingtheproblemofdistanciation,thedistancing ofthetextfromitsauthorandhistoricalcontext,whichlaterhermeneutic theoristssuchasWilhelmDilthey,E.D.Hirsh,andEmelioBetticoncede,and likethemHobbesbelievesthatwithdifficulty,andtherightmethods,the problemmaybeovercome.Whileinthe Geisteswissenschaften itis ‘completely nonsensical’ toattempttoridoneselfofsubjectivity,51 Hirsch,borrowing Piaget’sideaofacorrigibleschemata,maintainsunderstandingshouldbe conceivedasa ‘validating,self-correctingprocesswhichtestsandmodifies theschemataintheveryprocessofcomingtounderstandanutterance’ . 52

50 Hobbes, ElementsofLaw,ed.Gaskin,76–7.

51 Betti, ‘HermeneuticsastheGeneralMethodologyofthe Geisteswissenschaften’,62.

52 E.D.Hirsch,Jr., TheAimsofInterpretation (NewHaven,CT:YaleUniversityPress,1967), 34.Cf.32.

InDilthey’sviewthismaybeachievedonlyiftheexpressionsofotherpersons containnothingthatisnotalsofamiliartotheobserver,orinterpreter: ‘The samefunctionsandelementsarepresentinallindividualsandtheirdegreeof strengthaccountsforthevarietyinthemake-upofdifferentpeople.Thesame externalworldismirroredineveryone’sideas.’53

Thisepistemologicalhermeneuticsassumesthatweareabletoreconcilethe intentionsoftheauthorwiththemeaningofthetextbyrecognizingand exploringthehistoricityofthetext.Therequirementtounderstandthetextas theauthorunderstoodit,thatis,toequatemeaningwithintentions,isnotonly anepistemologicalrequirement,butalsoamoralimperative.Thetextisthe mindoftheauthorobjectifiedinwords,anddespitetheacknowledgement thatbothauthorandinterpreterarechildrenoftheirtimes,thelattermust surrenderandsubordinatehimself,orherself,whenattemptingtounderstand another-self.Theinterpreterisdutyboundtoenterintothe ‘closestharmony’ withtheauthorofatext,allowingtheirrespectiveindividualitiestoresonatein theattainmentof ‘re-cognition’ . 54 Anythinglessthanthereconciliationof meaningwithintention,itissuggested, ‘isnotinterpretationbutauthorship’ . 55

Istheassumptionthatwecanovercomeourownhistoricity,andsurrender ourselvestotheobjectofourunderstandingwarranted?Todenythepossibilityofrecoveringauthorialintentions,raisesquestionsoftheontologyofthe text,itsauthor,andinterpreter.Thequestionisnolongerhowweknow,with anemphasisonmethods,techniques,andcorrigibleschemata,butmore fundamentally,ofinsistingwithHeidegger,that verstehen,understanding,is primarilytheperson’sway,ormode,ofbeingintheworld,56 andwhose languageprojectsamultiplicityofmeanings.Theimplicationforthosewho challengeepistemologicalhermeneuticsis,agreeingwithPaulRicoeur,that thereisa ‘surplusofmeaning’,whichimpliesthatlanguageisnotmediation betweenmindsandthings,butinsteadconstitutiveofitsownworld,inwhich utterancesorexpressionsrefertoothersin ‘aself-sufficientsystemofinner relationships’ . 57 Thissurplusofmeaningdoesnotoccasionally,butalways, surpasstheauthor.Wearebeingswhosebeingconsistsinunderstanding,58 whichisnotaprocedureofreproducingmeaning,butisalwaysproductive ofit,goingbeyondDilthey’sdictumthat ‘inordertounderstand,onemust

53 WilhelmDilthey, SelectedWritings,ed.H.P.Rickman(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press,1976),261.

54 Betti, ‘HermeneuticsastheGeneralMethodologyofthe Geisteswissenschaften’,46,57, and58.

55 Hirsch, TheAimsofInterpretation,49.

56 MichaelErmarth, ‘TheTransformationofHermeneutics’ , Monist,vol.64(1981),184.

57 PaulRicoeur, InterpretationTheory:DiscourseandtheSurplusofMeaning (FortWorth, TX:TexasChristianUniversityPress,1973).

58 PaulRicoeur, HermeneuticsandtheHumanSciences,ed.JohnB.Thompson(Cambridge: CambridgeUniversityPress,1981),54.

alreadyhaveunderstood’ , 59 tothecontentionthat ‘oneunderstands differently whenoneunderstandsatall’ . 60 IntheviewofRicoeur,takingonboardthe shiftofemphasisinauguratedbyHeidegger,andcontinuedbyGadamer: ‘Understandingisthusnolongeramodeofknowledgebutamodeofbeing, themodeofthatbeingwhichexiststhroughunderstanding.’61

InGadamer’sview,thesituatednessoftheauthorandoftheinterpreter necessarilyentailsintheactofunderstandingwhatGadamercallsafusionof horizons.Gadamercontendsthatevery finitepresent,orsituation,islimited byhorizonsofaparticularstandpoint.HisdiscipleReinhartKoselleckextends themetaphorofhorizonfurtherbydistinguishingconceptswhichare embodiedinthesources(historical)andthosethatarecognitivecategories (metahistorical).Amongmetahistoricalcategories,forexample,are ‘spaceof experience’ and ‘horizonofexpectation’.Theexpressions ‘experience’ and ‘expectation’ areformalcategoriesthatdonotinthemselvesconveyany substantivecontentinthewaythat,forexample,suchdesignationsasthe ‘FrenchRevolution’ ,or ‘1812’ do.Whatisexperiencedandwhatisexpected maynotbededucedfromthecategoriesthemselves.Koselleckcontendsthat thecategoriesofthespaceofexperienceandthehorizonofexpectationare anthropologicalconditionswithoutwhichnointerpretationofhistorical entitiesispossible.Theconceptsareofthehighestgenerality,andinthis respectresemblethoseoftimeandspace.Unlikeconceptsembodiedinthe sourcesandwhichpresupposealternatives,suchasworkimpliesleisure,or masterimpliesslave,theconceptsexperienceandexpectationpresupposeno alternatives.Theyaremutuallydependent: ‘Noexpectationwithoutexperience,noexperiencewithoutexpectation.’62 Koselleckargues: ‘experienceand expectationaretwocategoriesappropriateforthetreatmentofhistoricaltime becauseofthewaythattheyembodypastandfuture’ . 63 Inbrief,experience positsarelationbetweenthepastandpresent.Theeventsofthepastare somehowincorporatedinthepresentthrougharationalreworking,or throughmodesofconductofwhichweneednotbeaware.Thereisaresidue,

59 QuotedinWilliamKluback, WilhelmDilthey’sPhilosophyofHistory (NewYork:Columbia UniversityPress,1956),27.

60 CitedbyDavidE.Linge, ‘Introduction’,Hans-GeorgGadamer, PhilosophicalHermeneutics (Berkeley,CA:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,1976),xxv.Thereferenceistopage280of WahrheitundMethode:GrundzügeeinerphilosophhischenHermeneutik (Tübingen:Mohr, 1960).ThequotationislesselegantlytranslatedintheEnglisheditionofHans-GeorgGadamer, TruthandMethod (NewYork:Crossroads,1981),264.

61 PaulRicoeur, TheConflictofInterpretations (London:Continuum,2011),7.Hewas neverthelesscriticalofHeidegger’sfailuretoexploreadequatelytheroleofhistoryininterpretationandtherelationbetweenphilosophyandhistory.PaulRicoeur, Memory,Historyand Forgetting (Chicago:ChicagoUniversityPress,2004),376.

62 ReinhartKoselleck, FuturesPast:OntheSemanticsofHistoricalTime (NewYork:ColumbiaUniversityPress,2004),257.

63 Koselleck, FuturesPast,258.

orsurvivalofthepastinthepresent,conceivedasalienexperiencetransmitted throughgenerationsandinstitutions.Expectation,whichisconstitutedby hopesandfears,wishesanddesiresaswellascares,concerns,andrational analysis,positsarelationbetweenpresentandfuture,itisthepresentmade futurethroughourhopesanddreamsdirectedtowardsthe ‘notyet,tothe nonexperienced’ . 64 Koselleckreferstothe ‘spaceofexperience’ andthe ‘horizonofexpectation’ inordertodistinguishbetweenthepresenceofthepast (experience)andthepresenceofthefuture(expectation).Withoutaspiring tocertaintythereareboundariesbeyondwhichthehorizonofthetextandof theinterpretercannotextend,thatis,beyondthespaceofexperienceandthe horizonofexpectation.65

Whilewemaynotbeabletopindownthepreciseintentionoftheauthor, weareabletoidentifyavocabulary,avernacular,whichheorsheusedto advanceanargument.AlasdairMacIntyreandMichaelSandel,forinstance, indicatehowthecontextoftheauthorlimitsexpectationsbecausecommunal valuessetthehorizonsofthegoalsthatitispossibletoset.Thesituation contributestothesortsofpersonstheyareandputslimitsontherangeof goalstheythinkitlegitimatetopursue.Theselfisnotpriortotheendsit pursuesandisinfactconstitutedbythem.Bybeingembeddedinsomeshared socialcontextmanyoftheendsthatconstituteusarenotchosen,butgiven.66

Languageisaself-referentialsystemofsigns,symbols,andcodeswhichhas noworld,time,orsubject,butwhichisanecessaryconditionofcommunication.Languageisrealizedindiscourse.Discourseisdistinguishablefrom languageinhavingasubject:itisalwaysaboutsomething.67 Discourseisa language-eventrequiringaspeakerandasubjectaboutwhichtospeak.In additiontowhichitisaddressedtosomeone,aninterlocutor.

GiventhatourbusinessistounderstandHobbes’swritingsappropriated andmanifestindifferentcontextsatdifferenttimes,wemustbeatpainsto identifywhatitisaboutwritten,asopposedtospoken,discoursethatfacilitatesappropriation.Spokendiscourseentailsadialogicalrelationshipinthatit isface-to-facecommunicationinstantiatingsenseandreference(locution), illocutionaryforce(apoint,purpose,intention),andaperlocutionaryeffect (consequencesoverwhichwehavelittlecontrol).68 Theseelementsareidentifiableevenintheleastarticulatedprosodicelementsofspeech,suchasthe pitch,tone,andrhythmwithwhichsomethingissaid,conveyingdifferent meanings,buttheyarewithincreasinglevelsofdifficultyalmostincapableof

64 Koselleck, FuturesPast,259. 65 Gadamer, TruthandMethod,269.

66 AlasdairMacIntyre, AfterVirtue (London:Bloomsbury,2013),chapter9;and,Michael Sandel, LiberalismandtheLimitsofJustice,2ndedition(Cambridge:CambridgeUniversity Press,2010),chapters1and4.

67 Ricoeur, HermeneuticsandtheHumanScience,198.

68 J.L.Austin, HowtoDoThingswithWords,2ndedition(Cambridge,MA:HarvardUniversity Press,1975).

beinginscribedinwrittendiscourse,compoundingtheproblemofretrieving authorialmeaning.Thisisbecausethetext,spokenandwritten,distancesitself fromitsauthor.Gadamerconteststheassumptionthatwecanovercome temporaldistancebetweenthenandnow.UnlikeHobbes,whowesaw conceiveddistanceasahindrancetointerpretation,Gadamerbelievesthatit providesthe ‘positiveandproductivepossibilityofunderstanding’ . 69 Thereis noabysstobeovercomebetweenthenandnow.Thedistance ‘is filledwiththe continuityofcustomandtradition,inthelightofwhichallthatishanded downpresentsitselftous’ . 70 Genuinehistoricalthinkingrequirestaking accountofitsownhistoricality.Distancereinforcesandaccentuatesthe differencesbetweenspokenandwrittendiscourse,andthesameprinciplesdo notapplytoboth.ElaboratingGadamer, 71 Ricoeurcontendsthatspoken discoursealreadycontainsanascentformofdistance.Languageisrealizedin theeventofdiscourse,butthesayingofitisitself fleetingandmomentary, surpassedinwhatissaid.Theeventofsayingdoesnotendure,butthe meaningofwhatissaiddoes.72 Ricoeurcontendsthatdistanciationisnot somethingextrinsicorparasitic,butisconstitutiveofthetextaswritten discourse,andmoreoveritistheveryconditionofunderstanding,without whichitisnotcapableofbeingappropriatedbythereader.73 Indistanciation themeaningofthetextreleasesitselffrom,andbreaksfreeof,theprosodic featuresofspeech,thatis,therestrictedhorizonandpsychologyofitsauthor. Distancedecontextualizesthetextfromitscontext,andprocuresnewreaders andinterpretations.74 Incontrastwithspeechthewrittentextisnotaddressed toaninterlocutorinadialogicalsituation,butpotentiallytoanyonewhocan read.Thetextescapesitsostensiblesenseandreference,andreplacesitwith whatGadamerreferstoasthe ‘matterofthetext’,andwhatRicoeurcallsits ‘world’ , 75 whichisthemodeofbeingconjuredupbyandprojectedinfront ofthetext,its ‘referentialmoment’ orthe ‘referential dimension’ . 76 Atthe momentofdistancingoneselffromtheself,ordispossession,thetextenters andextendsourownhorizon.Gadamermaintainsthatthecontextofinterpretationforthisimmanenttextistheinterpreter’scontext.Theinterpreter’ s contextisitselfconditionedbythetraditionthroughwhichithasbeenformed andtowhichboththetextandinterpreterarerelated.Theimmanenttextis atoncecontextfreeandcontext-bound.Freeinthesensethatthetextisits ownreference,boundinthesensethatthereaderencountersthetextinan

69 Gadamer, TruthandMethod,264.

70 Gadamer, TruthandMethod,204–5.

71 Gadamer, TruthandMethod,263–7.

72 Ricoeur, HermeneuticsandtheHumanSciences,134.

73 PaulRicoeur, ‘HistoryandHermeneutics’ , JournalofPhilosophy,vol.19(1976),691.

74 Ricoeur, HermeneuticsandtheHumanSciences,139,192,and201.

75 Ricoeur, HermeneuticsandtheHumanSciences,93.

76 Ricoeur, HermeneuticsandtheHumanSciences,112.

Introduction:AppropriatingHobbesinContexts

horizonofinterest,thatis,acontextwhichthereaderimplicitlybringswith himorher.77 Horizonsarenotaccidentalbecausetheyareconstitutedin traditionswhichdevelopwithinanhistoricalprocess. 78 AsGadamerfamouslycontended, ‘theprejudicesoftheindividual,farmorethanhisjudgments,constitutethehistoricalrealityofhisbeing’ . 79 Thisdoesnotmean thatoneinterpretationisasgoodasanother,orthatinterpretationis subjectiveandarbitrary.Thelanguagestructureofthetextlimitsthepotential world itisabletoproject,thatiswhatKoselleckcalledthespaceof experienceandthehorizonofexpectation,andultimately,asRicoeurinsists, itisalwaysopentoustoaf firmordenyinterpretations,confrontthem, arbitratebetweenthem,andaspiretoagreementevenwhenitisbeyondour immediategrasp. 80 Interpretersoftexts,inwhatevercontexts,havetoframe theirinterpretationsintermsofwhatcountsasaworthwhileinterpretation whichcannotbeseparatedfromnormativeexpectationsofwhatcountsasa rational,reasonable,defensible,andsuccessfulcontributiontoknowledge.81 Theknowledgeachievedresemblesalogicofprobabilityratherthanempiricalveri fication.Giventhatweknowaparticularconclusionismorelikely, ratherthan ‘true’,ithastobeconsistentwithestablishedproceduresof validationandinvalidation.KarlPopper’sprincipleoffalsi ficationisserved bythecon flictbetweencompetinginterpretationsoftexts.Ricoeurcontends: ‘Aninterpretationmustnotonlybeprobable,butmoreprobablethan anotherinterpretation.Therearecriteriaofrelativesuperiorityforresolving thiscon flict,whichcaneasilybederivedfromthelogicofsubjective probability.’ 82

Ifwearelookingforaqualifiednotionofthe ‘truth’ intheinterpretations weencounteroftextsindifferenthistoricalcontextswemayrefertoJohn Dewey’sideaofwarrantedassertability.Inquiry,heargued,isthe ‘controlled ordirectedtransformationofanindeterminatesituationintoonethatisso determinateinitsconstituentdistinctionsandrelationsastoconvertthe elementsoftheoriginalsituationintoaunifiedwhole’ . 83 Theend,orpurpose, ofinquiry,then,isthe ‘resolutionofanindeterminatesituation’ bywhatis warrantablyassertable.84 Whiledescribinghistheoryasaversionofthe

77 DavidCouzensHoy, TheCriticalCircle (Berkeley,CA:UniversityofCaliforniaPress,1982).

78 GuyA.M.Widdersshoven, ‘HermeneuticsandRelativism:Wittgenstein,Gadamer, Habermas’ , TheoreticalandPhilosophicalPsychology,vol.12(1992),6.

79 Gadamer, TruthandMethod,245.

80 Ricoeur, InterpretationTheory,79.

81 HilaryPutnam, RealismwithaHumanFace (Cambridge:CambridgeUniversityPress, 1990),33.

82 Ricoeur, InterpretationTheory,79.

83 JohnDewey, Logic:TheTheoryofInquiry (NewYork:HenryHolt,1938),104.

84 JohnDewey, ‘Propositions,WarrantedAssertability,andTruth’ , JournalofPhilosophy, vol.38(1941),180.