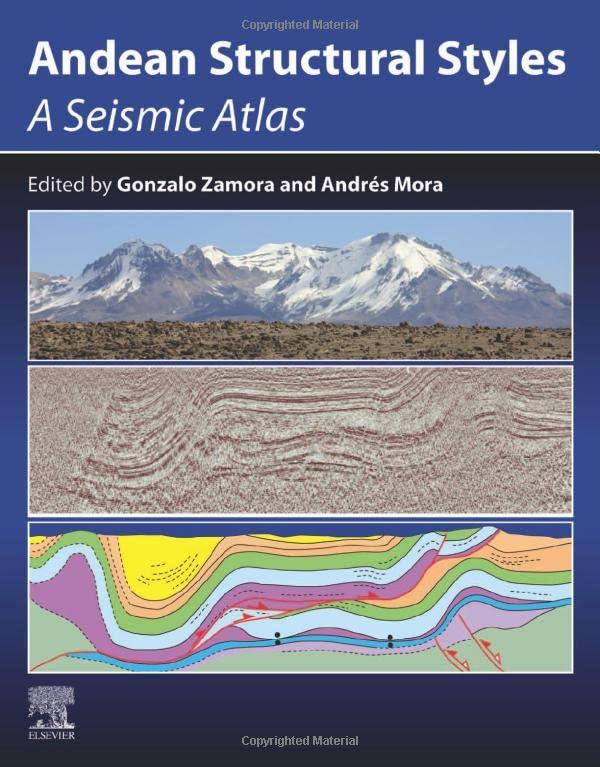

Tectonicframework

Modernconfiguration

ThemodernplatetectonicconfigurationofwesternSouthAmerica(Fig.1.1)involvesanocean-continentconvergentplate boundarywithasubductionzonedefinedbytheeast-dippingoceanicNazcaslab.Thetrench-parallelAndeanmagmaticarc iscomposedoffourdiscontinuoussegments(thenorthern,central,southern,andaustralvolcaniczones)dividedby separateregionsoflateCenozoic flat-slabsubductionorslab-windowgeneration,includingtheColombian/Bucuramanga flatslab(2 8 N),Peruvian flatslab(5 15 S),Chilean/Pampean fl atslab(27 33 S),andthePatagonianslabwindow adjacenttotheNazca-Antarcticaspreadingridge(45 48 S)(BarazangiandIsacks,1976; Jordanetal.,1983; Ramos, 1999; BreitsprecherandThorkelson,2008; RamosandFolguera,2009; Wagneretal.,2017).TheAndesMountainsforma continuoustopographicbarrierthatistheproductofretroarccrustalthickeningdrivenbyhorizontalshorteningina compressionaltectonicregime.Thisshorteninghasbeenaccommodatedintheretroarcfold-thrustbeltbyprincipallydipslipcontractionalstructures,asreflectedinearthquakefocalmechanismsandmodernstressmeasurements (e.g., Assumpçãoetal.,2016).Manythrust-beltstructuresaregeometricallyandkinematicallylinkedtoamiddletoupper crustaldécollementthatisconsideredtounderlietheentireAndeanorogenicbelt(Babyetal.,1997; McQuarrie,2002a; Giambiagietal.,2012, 2015).

TheAndeantopographicfrontmarksthesharpboundarybetweenthefold-thrustbeltandthelowplainsoftheforeland basinsystem,inwhichregionalisostatic(flexural)subsidencehasgeneratedaccommodationspaceforlargevolumesofclastic sedimenterodedfromtheAndeanorogen(HortonandDeCelles,1997; Moraetal.,2010a).Additionally,isolatedtopographic highswithinthebroadforelandlowlands,althoughdisconnectedfromAndeantopography,representtheeasternmost expressionofcrustalshortening(i.e.,theforelanddeformationfront),suchasinthewesternAmazonianforelandofPeru (5 15 S)andtheSierrasPampeanasofcentralArgentina(27 33 S).Inmanyregions,Andeanstructuralandstratigraphic recordsindicatealong-termcratonwardadvanceofarcmagmatism,fold-thrustdeformation,andforelandbasinsubsidence (Rutland,1971; Isacks,1988; DeCellesandHorton,2003; Gómezetal.,2005; Haschkeetal.,2006; CarrapaandDeCelles, 2008; Bayonaetal.,2008; FolgueraandRamos,2011; Hortonetal.,2020; Capaldietal.,2020, 2021).Thissystematicpattern, however,isnotwelldevelopedinotherregions(particularlywithinnarrowsegmentsoftheorogensuchasthenorthernAndes ofEcuadorandsouthernColombiaat2 N 5 SandthesouthernAndesofChileandArgentinaat34 44 Sand50 55 S) wherenonuniformandunsteadyprocesseshavebeenpromotedbychangesinslabdynamics, fluctuationsintectonicregime, orvariationsimpartedbytectonicinheritance(e.g., MpodozisandRamos,1990; Cooperetal.,1995; Collettaetal.,1997; Charrieretal.,2002; Parraetal.,2012; McGroderetal.,2015; Folgueraetal.,2015).Furthercomplexitiesareintroducedby spatiallyvariableclimaticconditionsthatcansetupinternalfeedbacksbetweenerosionanddeformationstylethatvaryalong thelengthofthe w8000kmlongorogenicbelt(Maseketal.,1994; Horton,1999; Montgomeryetal.,2001; Streckeretal., 2007; McQuarrieetal.,2008; Moraetal.,2008; Ghiglioneetal.,2019).

Orogenichistory

Mesozoic CenozoicsubductionalongthewesternedgeofSouthAmericangeneratedalong-livedcontinentalmagmatic arcandretroarcregionwithdiversestructuresandbasinsystems.Afundamentalshiftat w100Mafromextensionalor neutraltectonicregimestochiefl yretroarcshorteningfollowed w130 120MaopeningofthesouthAtlanticOceanand westwardadvanceoftheSouthAmericanplateawayfromtheAfricanplate(ConeyandEvenchick,1994; Horton,2018a; Giannietal.,2018).AfterthisstageofGondwanabreakup,plateconvergenceinvolvedwestwardabsolutemotionofSouth Americanabovesubductedeast-dippingoceaniclithosphere,withlimitedaccretionofoceanicmaterialsalongthe northernmostandsouthernmostAndeanmargin(Dalziel,1986; Megard,1989).

ConstructionoftheAndesisattributedtoLateCretaceous-Cenozoicretroarccrustalshorteninginwhichtheinboard (eastward)advanceofthedeformationfrontdemonstratesthetime-transgressivehistoryofcrustalthickeningandassociated flexuralforelandbasindevelopment.Nazca-SouthAmericanplateconvergencewasgenerallyorthogonaltothe roughlynorth-trendingplatemargin(Maloneyetal.,2013; Mulleretal.,2016).Obliquecomponentsofplateconvergence havebeenlargelyaccommodatedinthearcandforearcregions(e.g., Fitch,1972),withmoststructuresintheretroarcfoldthrustbeltrecordingplane-strainconditionsmarkedbythrust/reversefocalmechanismswithminimalstrike-slip displacement(Fig.1.1).Similarly,extensionhasbeenconfinedtoeitherthehighestsegmentsoftheorogenicbelt, wheregravitationalcollapseispossible(e.g., DalmayracandMolnar,1981),orthethrustbelthinterlandtoforearcregion wherediminishedmechanicalcouplingalongthesubductioninterfacemayallowextensionduringslabrollback(Meade andConrad,2008; Martinodetal.,2010).

Time-spacevariability

DespitethesharedMesozoic Cenozoicplatetectonichistoryofroughlyorthogonalconvergenceandnoncollisional processesalongthelengthofwesternSouthAmerica,Andeanorogenesishasinvolvedsubstantialvariabilityintectonic regime,deformationmagnitude,andbasinevolution.LateCretaceous-Cenozoicvariationsintectonicregimeinclude alternationsbetweensustainedregionalcompressionandshorterepisodesofminorextensionorneutralstressconditions (Ramos,2010; Horton,2018b).Additionaltemporalvariationsmaybemanifestasdiscreteepisodesofacceleratedor deceleratedAndeandeformationandforelandsubsidence(e.g., Verganietal.,1995; Jaillardetal.,2000; Gómez etal.,2005; Onckenetal.,2006; Bayonaetal.,2008; Parraetal.,2009; BufordParksandMcQuarrie,2019; Echaurren etal.,2019).SpatialvariationsarereadilyapparentinthemodernAndeanorogen(Fig.1.1)andincludealong-strike fluctuationsintopography(heightandwidthoftheorogen),crustalthickness,shorteningmagnitude,andarcmagmatism.

SeveralspatialvariationsintheAndescorrelatewiththecurrentplatetectonicconfiguration.Alongthelengthofthe platemargin,themoderndistancesfromthetrenchto(A)theAndeantopographicfront(thethrustbelt-forelandbasin boundary)and(B)theforelanddeformationfront(easternmostsurfaceorsubsurfaceexpressionofCenozoicshortening) arehighlyvariablealongstrike(Fig.1.2)(Hortonetal.,2022).Thetrench-normaldistancesspanfrom300to800km,with themostpronouncedinboardpositionofthetopographicanddeformationfrontsrecognizedinfourseparateprovinces. ThemaximuminboardadvanceoftopographyanddeformationisdefinedinthecentralAndes,wheretheAndeanorogen attainsitsgreatestwidth,crustalthickness,totalhorizontalshortening,andmeanelevation.Theotherthreeprovinces overlapwiththePeruvian flatslab(5 15 S),theChilean/Pampean flatslab(27 33 S),andthePatagonianslabwindow wheretheNazca-Antarcticaspreadingridge(ChileRidge)intersectstheAndeanmargin(45 48 S).

Rationale:tectonicinheritance

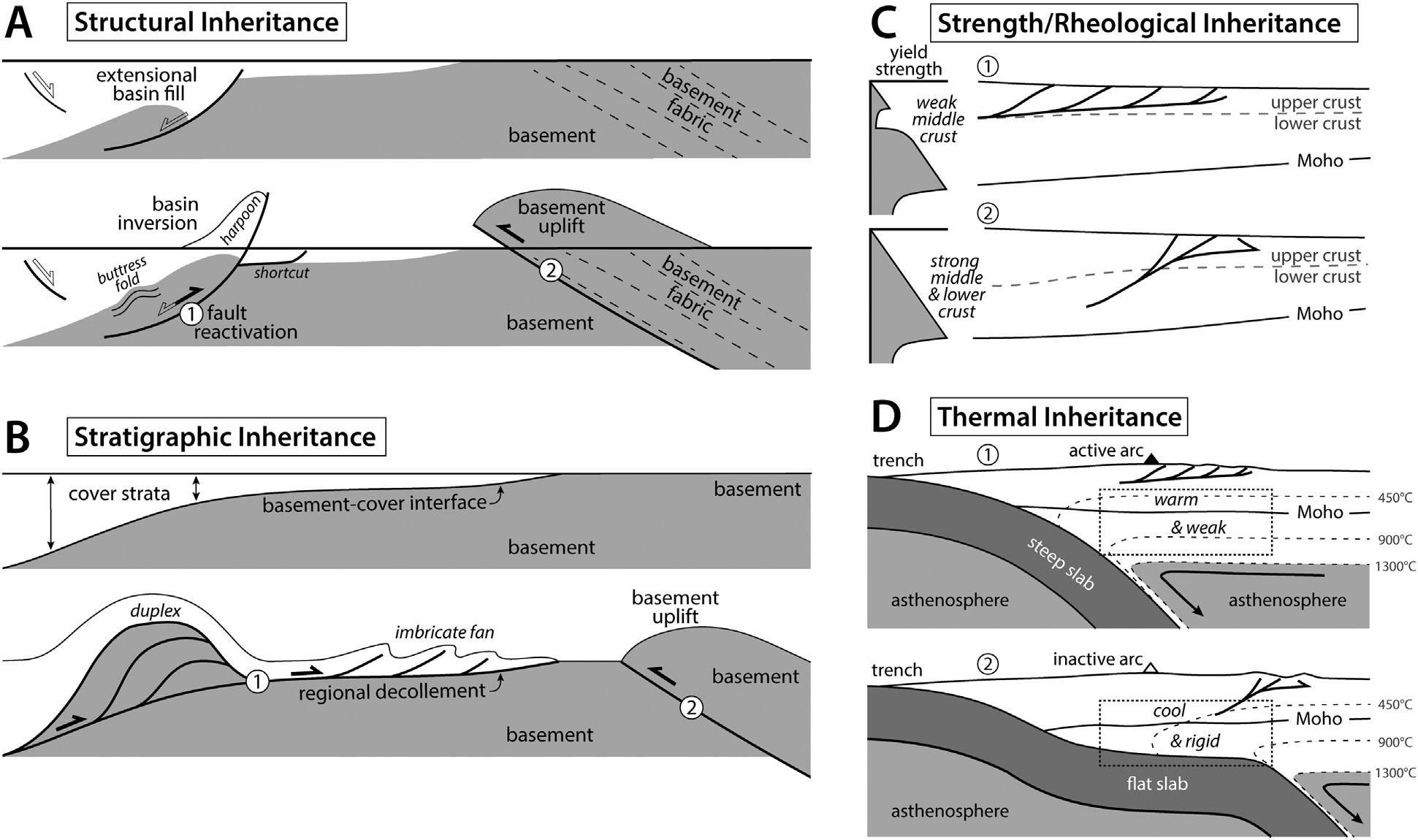

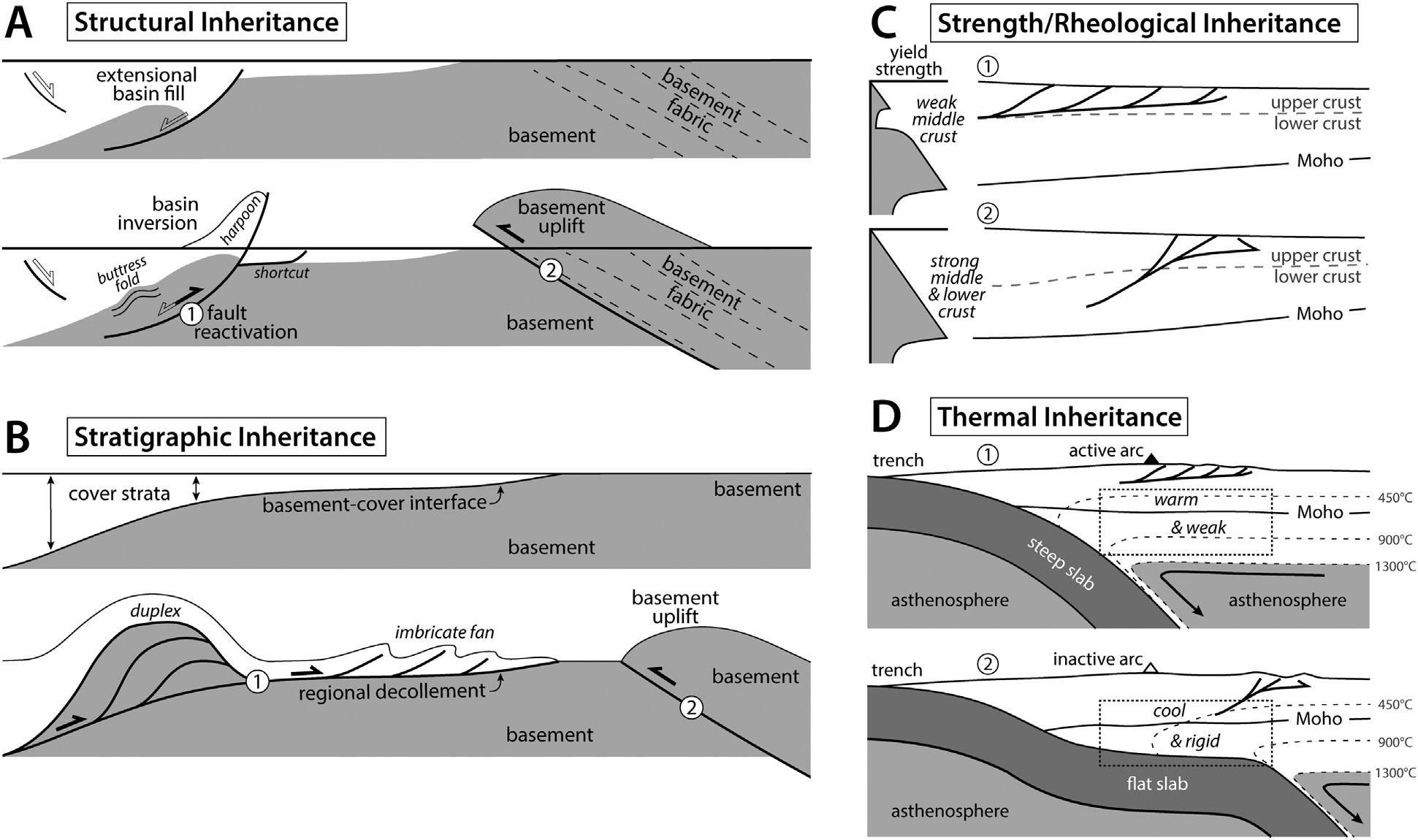

WeproposethatstructuralstylesintheAndesandmanycontractionalorogenicbeltsmaybeconsideredinthebroad contextof tectonicinheritance (Fig.1.3).Thisrationalehighlightstheinfl uenceoffourparameters:(1)preexisting structures,(2)precursorstratigraphicarchitecture,(3)rheologicalandstrengthproperties,and(4)crustal/lithospheric thermalconfiguration.Thesecategoriesarenotmutuallyexclusive,butarespeci fiedhereinordertoappreciatetherangeof potentialexplanationsfordifferencesinstructuralstyle.Inthisrationale,theconceptofinheritanceneednotbelimited strictlytocasesofstructuralinheritancethatinvolvefaultreactivationandinversionofformersedimentarybasins. Wesuggestthatthefourtypesofinheritancepresentedheremayapplyatdifferentspatialandtemporalscales.This approachrecognizescontrastingprocessesin(a)upperversuslowercrustalregions,(b)supracrustalcoverstrataversus mechanicalbasement,(c)morefelsic(weaker)versusmorema fic(stronger)composition,and(d)earlyorogenic(thin crust)versuslateorogenic(thickcrust)conditions.

Structuralinheritance

Structuralinheritancerepresentstheinfluenceofpreexistingfaultsorbasementfabricsonstructuralstyle(Fig.1.3A). Structuralinheritanceisreadilyrecognizedincasesoffaultreactivationandbasininversioninuppercrustallevels (e.g., McClay,1995; Lowell,1995; CooperandWarren,2010; Boninietal.,2012).ManyAndeanfaultsarespatially colocatedorcloselyparalleltopreexistingfaultsandbasementfabrics.AfrequentAndeansituationinvolvesthereactivationofMesozoicextensionalfaultsasthrustorreversefaultsduringCenozoicshortening.Insuchcases,apre-Andean structurallowdelineatedbyahangingwallextensionalbasinbecomeslaterelevatedduringAndeanshortening,inverting theoriginalbasin.BasininversionisprevalentinsurfaceandsubsurfaceexamplesthroughouttheAndes,particularlyin theeasternfoothillsofColombia(2 7 N; Cooperetal.,1995; Moraetal.,2009; Tesónetal.,2013; Teixelletal.,2015; Moraetal.,2020; Costantinoetal.,2021),theforelandprovincesofEcuadorandPeru(0 13 S; Balkwilletal.,1995; Babyetal.,2013; McGroderetal.,2015; ZamoraandGil,2018; McClayetal.,2018),theSaltariftsystemofnorthernmost Argentina(22 27 S; Grieretal.,1991; ComínguezandRamos,1995; KleyandMonaldi,2002; Kleyetal.,2005; Carrera etal.,2006; Monaldietal.,2008);andtheNeuquénBasinofcentralArgentina(34 40 S; MancedaandFigueroa,1995; MosqueraandRamos,2006; Giambiagietal.,2008, 2022; Mescuaetal.,2014; Fuentesetal.,2016).

Contractionalinversionofanancestralextensionalbasincanberecognizedby:asharpcontrastbetweenthick hangingwallstratigraphicunitsandthinnercorrelativefootwallstrata;thepresenceoffault-proximalfacies(including coarse-grainedalluvialfanorfan-deltadeposits)preferentiallydevelopedinhangingwallareasadjacenttotheoriginal normalfault;andthespatialcoincidence,intersection,oroverlapofoldernormalandyoungerthrust/reversefaults. Unequivocaldemonstrationoffaultreactivationcanbechallenging,inthatnewlyformedthrustfaultsmayalsonucleate withintheextensionalbasinincloseproximitybutnotpreciselyalongoriginalnormalfaults.

FIGURE1.2 Acomparativeplotshowingalong-strike(latitudinal)variationsinAndeanorogenicwidthandretroarcshortening.Orogenicwidthis definedasthetrench-normal(cross-strike)distancebetweentheSouthAmericansubductiontrenchandtheAndeandeformationfront,withdelineationof threeseparateprovincesofbasement-involvedforelanddeformation:(1)Peruvianforeland(5 15 S),(2)SierrasPampeanasforeland(27 33 S),and(3) northernPatagonianforeland(45 48 S). From Hortonetal.(2022).

Characteristicstructuresaccompanyingbasininversion(Fig.1.3A )includearrowheadorharpoonthrust-fold geometriesde fi nedbyreactivatedfaultswithsynextensionalstrat alwedge(half-graben)geometriespreservedin hangingwallanticlines;andbuttress-relatedfoldsformed inhangingwallswheresteeplydippingfaultsegmentsand/or rigidfootwallbasementrocksimpedeslipalongthereactivatedfaultsurface(Badleyetal.,1989 ; McClay,1995 ; Carrera etal.,2006; GranadoandRuh,2019 ; Martínezetal.,2021).Listricnormalfaultsarepronetopartialreactivationwith

FIGURE1.3 Aseriesofcrosssectionsdepictingfourmodesoftectonicinheritance.(A)Structuralinheritance,inwhichshorteninginvolves(1) reactivationofapreexistingnormalfaultwithaccompanyingbasininversion,and(2)faultnucleationalongigneousand/ormetamorphicbasementfabrics. (B)Stratigraphicinheritancerepresentedby(1)upper-crustalshorteningaccommodatedbyinterconnectedramp-flat(décollement-style)thin-skinned structuresinvolvingcratonward-taperingcoverstrataversus(2)basement-involvedthick-skinnedshorteningalongisolatedfaultstructuresthatpenetratetodeepercrustallevels.(C)Rheologicalinheritance,inwhichvariationsinyieldstrengthprofiles(aswellasmineral/rockcomposition, fluidcontent/ pressure,andresultingheterogeneitiesandanisotropies)promote(1)aweakmid-crustaldécollementwithassociatedthin-skinnedfold-thrustbeltversus (2)auniformlystrongprofilewiththick-skinnedcrustal-scalebasementfaults.(D)Thermalinheritance,showingthethermalstructurealonganoceancontinentconvergentmargininvolving(1)asteepsubductionzonewithawarm,weakoverridingplateundergoinghigh-magnitudehorizontalshortening inaretroarcfold-thrustbeltand(2)a flatslabsubductionzoneinvolvingacool,rigidoverridingplateinwhichcrustal-scalecontractionalstructures developtowardthecratonwithintheplateinterior.

shortening-induceddisplacementfocusedalongthegentlydipping,deepersegmentsofthefaultratherthanthesteeper shallowsegments.Insuchcases,deformationatshallower levelsmaybemanifestinnewlyformedfootwallsplayor shortcutfaultsgeometricallylinkedt othedeeperreactivatedmasterfault( MoraandParra,2008; Amilibiaetal.,2008 ; CarreraandMuñoz,2013; Tesónetal.,2013 ; Fuentesetal.,2016 ; Moraetal.,2020 ).Severalexamplesoffault reactivationandbasininversionarepresentedinthisvolume(e.g., ZamoraandCarter,2022 ; MartínezandFuentes, 2022 ; Giambiagietal.,2022; Cortésetal.,2022).

AndeanstructuralreactivationisnotrestrictedtoMesozoicnormalfaults,asinheritedPaleozoicandPrecambrian structureshavealsobeenreactivated(e.g., CarreraandMuñoz,2013; Giambiagietal.,2014; Perezetal.,2016a).AlesscommonillustrationofstructuralinheritanceinvolvesstrainlocalizationofAndeanstructuresalongmetamorphicand/or igneousfabrics(Fig.1.3A).Thesefabricsconstitutepreexistingplanesofweakness(suchasfoliation,schistosity,or cleavageplanes)thatarepreferentiallyactivatedduringregionalshortening.MostexamplesofthisprocessinvolvepreAndeanweaknesseswithincrystallinebasementorintrusivebelts(GonzálezBonorino,1950; MosqueraandRamos, 2006; Hongnetal.,2010; Giambiagietal.,2011),butPaleozoicfoliationorcleavagefabricswithinsedimentaryrocksalso havebeeninferredtoguidelaterAndeanstructures(Laubacher,1978; Dalmayracetal.,1980; Martinez,1980).

Animportantadditionalformofstructuralinheritanceinvolveslarge-scaleAndeanreactivationofregionalmid-to upper-crustalextensionaldetachments.Forexample,thebasementdetachmentandaffiliatednormalfaultswithinthe w250kmwideCretaceousSaltariftsystemwerereactivatedduringCenozoicshortening,creatingaseriesofparallel rangeswithinthePunaandSantaBarbararegionsofnorthernmostArgentina(22 27 S; Grieretal.,1991; Kleyand Monaldi,2002; Pearsonetal.,2013).Theregionalintegrationandgeometriclinkageofthesestructuresruleoutoversimplifiedinterpretationsofthesefeaturesasisolated,independentbasementupliftsanalogoustocrustal-scalestructuresof theSierrasPampeanasprovince(27 33 S)(e.g., Montero-Lópezetal.,2018).

Stratigraphicinheritance

Stratigraphicinheritancereferstotheimpactofpredeformationalstratigraphicarchitectureonstructuralstyle(Fig.1.3B). Incontractionalsystems,aspatialcorrespondencehasbeenobservedbetweentheinheritedstratigraphicframeworkand theexistenceandgeometryofregionaldécollementsandinterconnectedramp- flatstructuresdevelopedinpreexisting supracrustalcoverstrata(LagesonandSchmitt,1994; Lawtonetal.,1994; Boyer,1995; Mitra,1997; Espurtetal.,2008; YonkeeandWeil,2015; ParkerandPearson,2021).Speci fically,anasymmetricforeland-taperingstratigraphicprismthat isthickerinthehinterlandandthinnerintheforelandroutinelycorrelateswithadeformationalstyleinvolvingamaster regionaldécollementbeneathafold-thrustbeltcommonlycharacterizedbyaleadingimbricatefanandtrailingzoneof duplexstructures(Fig.1.3B).Forsuchstratigraphicwedges,theprincipaldécollementissituatedatornearthebasementcoverinterface,withpotentialadditionaldetachmenthorizonspresentathigherstructurallevelswithinthecover succession.InnearlyallAndeancases,themaindécollementislinkedtoamajorfootwallrampinthetrailingpartofthe fold-thrustbeltthatpenetratesintotheunderlyingbasement,althoughthesebasementrocksmayremainatdepthwithno surfaceexposure(e.g., Kley,1996; AllmendingerandZapata,2000).

Twokeyexamplesincludeforeland-directed(east-vergent)structuresoftheInterandeanandSubandeanfold-thrustbelt inthecentralAndesofsouthernPeru,Bolivia,andnorthernmostArgentina(13 23 S; Mingrammetal.,1979; Babyetal., 1995, 1997; Dunnetal.,1995; Kley,1996; Morettietal.,1996; Echavarriaetal.,2003; Andersonetal.,2017, 2018; Fuentesetal.,2018; RojasVeraetal.,2019),andretroarcthruststructuresinthePrecordilleraofthesoutherncentral Andesofwest-centralArgentina(29 33 S; vonGosen,1992; Ramosetal.,1996; CristalliniandRamos,2000; AllmendingerandJudge,2014).Thesezonescontainhinterland-thickeningPaleozoicstratigraphicpackagesinwhichagently west-dippingdécollementformsalonginheritedstratigraphiccontactswithinthePaleozoicsuccessionandalongthebasal interfacewithPrecambrianbasementrocks.

InselectedAndeanregions,comparablegeometriesareexpressedinMesozoicstratacappingmechanicalbasementof latePaleozoicage.Suchcasesincludeanarrayofimbricatefan,duplex,andbackthruststructures,asrecognizedinthe TierradelFuegoregionofthesouthernmostAndes(53 56 S; Alvarez-Marrónetal.,1993; Kraemer,2003)andinthe hinterlandAconcaguaandLaRamadasegmentsofthesoutherncentralAndes(CegarraandRamos,1996; Giambiagi etal.,2003).

Acomplexpre-AndeanhistoryresultedinanirregularspatialdistributionofPaleozoicandMesozoicstratigraphic packagessuitableforaramp-flatstructuralstyle.PaststudieshaveshownthataninheritedPaleozoicorMesozoicstratigraphicprismisanecessaryconditionfortheregionalemergenceofsuchorganizedthin-skinneddeformationalbelts (Allmendingeretal.,1983; McQuarrie,2002b; McGroderetal.,2015).Theaforementioneddistrictsalsorecordedthe highestmagnitude(>100 200km)ofhorizontalshorteningintheAndes(KleyandMonaldi,1998; Kleyetal.,1999; AllmendingerandJudge,2014).Inthesesegments,thepositionoftheretroarcdeformationfront(Fig.1.2)maybelargely regulatedbytheoriginalstratigraphicarchitecture thatis,thedeformationfrontcorrespondstotheinboard(eastern) pinchoutofPaleozoicorMesozoicbasin fill.Similarly,themajorfootwallrampinthethrust-belthinterlandmaycoincide withthesharpstratigraphictransitionbetweenthinshelf/platformfaciesintheeastandthickerslopedepositsinthewest.

Afundamentalcorollarywithintheframeworkofstratigraphicinheritancepertainstozonesofbasementdeformation definedbyisolatedcrustal-scalereversefaults(Fig.1.3B).ExamplesofthisclassicstructuralstyleinwhichbasementinvolvedreversefaultspenetratetodeepercrustallevelsincludetheSierrasPampeanasofcentralArgentina(27 33 S) andtheLaramideprovinceinthewesternUSA(31 46 N)(JordanandAllmendinger,1986; YonkeeandWeil,2015).In theseforelandregionssituated >500 1500kminboardofthetrench(Fig.1.2),thepredeformational(pre-Andean) stratigraphicpackageiseitherabsentorofverylimitedthickness(<500m)andexhibitsnopronouncedlateralthickness variations.Therefore,thelackofathick,wedge-shapedsedimentarysuccessionvirtuallyguaranteedthatanycompressionalstressesthatpropagatedsuf ficientlytosuchintracontinentalsettingswouldresultinshorteningthatpreferentially affectedtheunderlyingcrystallinebasement(Allmendingeretal.,1983; YonkeeandWeil,2015).Inotherwords, shorteningthatisconfinedmostlytothebasementdomaincanbeconsideredanaturalconsequenceofthevolumetric dominanceofbasementrocksrelativetothincoverstrata.Nevertheless,thelackofathickstratigraphicpackageshouldnot beviewedastheonlypotentialdriverofbasement-involveddeformation.

Rheologicalinheritance

Rheologicalpropertiesarecriticalindefiningstructuralgeometries,strainlocalizationpatterns,anddeformationkinematics ofcontractionalorogenicbelts(Fig.1.3C).Atthelithosphericscale,structuralstylemaycorrelatewithoverallintegrated strengthorwithverticalstrengthvariations,asrepresentedbycontrastingyieldstrengthprofi lesforthecrustandupper

mantle(Faríasetal.,2010; Barrionuevoetal.,2021; Ibarraetal.,2021).Auniformincreaseinyieldstrengthwithdepth mayimpartahighdegreeofmechanicalcouplingbetweentheupperandlowercrust,andthereforethegenerationof disconnectedcrustal-scalestructuresthatpenetrateintothedeepercrust(Fig.1.3C).Incontrast,averticalstrengthprofile withaweakmiddlecrustwouldpromotedecouplingbetweentheupperandlowercrust(Fig.1.3C),thusfavoring developmentofadécollementwithaseriesofgeometricallylinkedthrustfaults(e.g., JammesandHuismans,2012; Jammesetal.,2014; Giambiagietal.,2015; Wolfetal.,2021).Theseopposingrheologicalcircumstancesaredistinguishedfromtheprecedingcasesofstructuralandstratigraphicinheritancebytheirapplicationtonewlyformedratherthan strictlyreactivatedstructuresandtodeeperzonesbelowsupracrustalsedimentaryrocks.

Rheologyisstronglyconnectedtovariationsinthethickness,composition,age, fluidcontent,andpore fluidpressureof continentalcrustandlithosphere(Ruhetal.,2012; Mouthereauetal.,2013; P fiffner,2017; Martinodetal.,2020).These parameters,whichhelpshapethemechanicalandcompositionalheterogeneitiesandanisotropiesattheregionalscale(as opposedtoinheritedstructuresatthelocalscale),arelargelyinheritedfromtheprecedingtectonichistoryalongthe continentalmargin.Forexample,disparitiesinregionalthinningofpre-AndeancrustandlithosphereduringMesozoic extensionhelpeddeterminetherheologicalframeworkpriortowidespreadCenozoicshortening(Dalziel,1981; Sempereetal.,2002; Fosdicketal.,2014).AdditionalrheologicaldissimilaritiesintheAndescanbeattributedtospatial compositionalvariationsduetoPrecambrian Paleozoicaccretionofcompositionallydistinctbasementblocks(Ramos etal.,2004; Mescuaetal.,2016; Ramos,2018)andMesozoicadditionofmafi cigneousmaterialswithinthemagmaticarc andadjacentbackarcregion(e.g., Atherton,1990; Lucassenetal.,2004).

Inadditiontotheseinheritedpredeformationalproperties,changesinthicknessandcompositionofcontinentalcrust andlithosphereinevitablyoccur during orogenesis.Processessuchasprogressivecrustalthickening,basalticunderplating, andincrementalorepisodicremovalofdenselowercrustorlithospherewillaffecttheoverallcrustalandlithospheric architecture(Allmendingeretal.,1997; PopeandWillett,1998; Haschkeetal.,2006; DeCellesetal.,2009; Garzioneetal., 2017).Synorogenicvariationsintheseprocessesarecapableofinducingpivotalshiftsfromonedeformationstyleto another.Insystemsgovernedbylarge-magnitudeshortening,regionalcrustalthickeningandgrowthofcontinentalplateausgenerallyresultsinprogressivelylowervaluesofintegratedcrustalstrength.Thismechanicalweakeningenhances strainlocalizationand/orductile flowwithinthickenedcrust,affectingdeformationalprocessesintheinteriorandlateral marginsoftheorogen(Babeykoetal.,2006; Barrionuevoetal.,2021; Ibarraetal.,2021; Wolfetal.,2021).Incontrast, otherstudieshavesuggestedthatstrainhardeningormechanicalstrengtheningoccurswithintheorogenicinteriorduring progressiveshortening,promotingoutwardadvanceofdeformationtoorogenic flanks(e.g., Nemcoketal.,2013; Mora etal.,2013).

TherheologicalstructureandyieldstrengthprofilesforparticularsegmentsofwesternSouthAmericawillhave evolveddifferentlyaccordingtoboththeinheritedpre-Andeanframeworkandsynorogenicchangesinthethickness, composition,andothermechanicalpropertiesofcrustandlithosphereduringAndeanorogenesis.TheeffectsofsynorogenicshiftsinrheologyaremostacuteinthecentralAndean(Altiplano-Puna)plateau,whereextremecrustalthickeningandpartialremovalofthelowerlithospherehasgeneratedmechanicalweakeningandamorefelsicbulkcomposition (BeckandZandt,2002; Tassaraetal.,2006),whichhavefurtherpromotedadditionalshorteninganddeformationadvance (SobolevandBabeyko,2005).

Thermalinheritance

Thethermalconfigurationofcrustandlithosphereinfl uencesstructuralgeometriesandorogenicdeformationalpatternsat differentscales(Beaumontetal.,2006; JamiesonandBeaumont,2013; Fossenetal.,2017).Atthelocalscale,temperature variationsintheuppercrustimpacttheyieldstrengthandfrictioncoef ficientofpreexistingfaults,alongwithassociated fluidpropertiesandporepressures,thusinfluencingtheirsusceptibilitytoreactivation(Sibson,1977; Boninietal.,2012; Lafosseetal.,2016; RattezandVeveakis,2020).Attheregionalscale,thethermalstructureofcrustandlithospherehelps dictatetheintegratedstrengthofrockmaterials,whichaffectsbroaderpatternsofstrainlocalization(Buiteretal.,2009; LacombeandBellahsen,2016).Overtime,regionalheatingorcoolingwillhelpdeterminedeformationstylethroughthe progressiveweakeningorstrengtheningofcontinentalcrustalmaterials.Asinthecaseofrheologicalinheritance (Fig.1.3C),contrastsintheverticalyieldstrengthprofi lewillinfluencecouplingbetweentheupperandlowercrust,and thusfavorisolatedcrustal-scalestructuresordécollement-styledeformationwithlinkedthrustfaults.

Alongsubductionmargins,spatialvariationsingeothermalgradientarelikelytofosterdifferentstructuralstylesin forearc,magmaticarc,andretroarcregions.Forexample,rapidheatingepisodesrelatedtopulsesofarcmagmatism, delamination,orremovaloflowercontinentallithosphere,asthenosphericupwelling,and/orslabwindowformationmay triggerdistinctdeformationresponses(BeckandZandt,2002; RamosandKay,2006; BreitsprecherandThorkelson,2008; TectonicinheritanceandstructuralstylesintheAndeanfold-thrustbeltandforelandbasin

DeCellesetal.,2009; KayandCoira,2009; Folgueraetal.,2015; Garzioneetal.,2017; GianniandPérezLuján,2021).In thispresentation,wefocusonthecontrastingthermalprofilesinheritedfromsteepversus flat-slabsubduction(Fig.1.3D) (Gutscher,2002).Whereassteepsubductioncorrelateswitharelativelywarmretroarcsysteminvolvingadecoupledupper crustalfold-thrustbelt, flatsubductioncools(refrigerates)theplatemargin,extinguishesthemagmaticarc,andpromotes rigid,crustal-scaledeformationfarthertowardthecraton(Fig.1.3D).Thelattersituationisobservedalongthemodern Andeanmargin,wherethePeruvian(5 15 S)andChilean/Pampean(27 33 S)zonesof flat-slabsubduction(Jordan etal.,1983; Ramosetal.,2002; RamosandFolguera,2009; Bishopetal.,2018)spatiallycorrelatewithbasement shorteningprovincesandinboardpenetrationoftheforelanddeformationfront(Fig.1.2).

Intheancientrecord,shallowingorsteepeningofthesubductingslabwouldabruptlyalterthethermalconfiguration andpromptashiftinstructuralstyle(e.g., Jordanetal.,1983; KayandCoira,2009).Wherepastphasesof fl atsubduction havebeenfollowedbyslabresteepeningandattendantheating(andlithosphericthinning),pervasivethermalweakeningis envisionedtopromotedecouplingwithinthecrustandgenerationoflarge-magnitudethrust-beltshortening(Isacks,1988; WdowinskiandBock,1994; Tassara,2005).Similarlyrapidphasesofheatingmayaccompanytheremovalorfoundering ofdenseorogenicroots,furtherpromotingupper-crustaldeformationandadvanceoftheretroarcfold-thrustbelt (e.g., DeCellesetal.,2009; Garzioneetal.,2017).Bothoftheseprocesses slabresteepeningandlithospheric removal mayhelpexplainhowthecentralAndesattainedanexceptionalwidth(Fig.1.2),accommodatedlargemagnitudeshortening(Schmitz,1994; Babyetal.,1997; McQuarrie,2002a),andgeneratedaforelandbasinthat advancedfartowardthecraton(DeCellesandHorton,2003; Horton,2018a).

Althoughitcanbediffi culttoseparatetherolesofthermalandrheologicalinheritance,theaforementionedexamples focusoncasesofthermaltriggering,whererapidcoolingorheatingfavorsaparticularstructuralstyle.Intheabsenceof suchabruptepisodes,thethermalconditionsattheonsetofAndeanorogenesiswerelargelygovernedbythelocationand relativemagnitudeofearliercrustalandlithosphericthinningduringMesozoicextension.Thereafter,Cenozoicshortening wouldhaveinducedthickeningandbuildupofanorogenicroot,whichprogressivelymodi fiedthethermalstructureand ledtoslowwarmingofretroarcregions.Inthesecases,thethermalconfigurationwaslikelysubordinatetootherformsof tectonicinheritance.

Andeanstructuralstyles

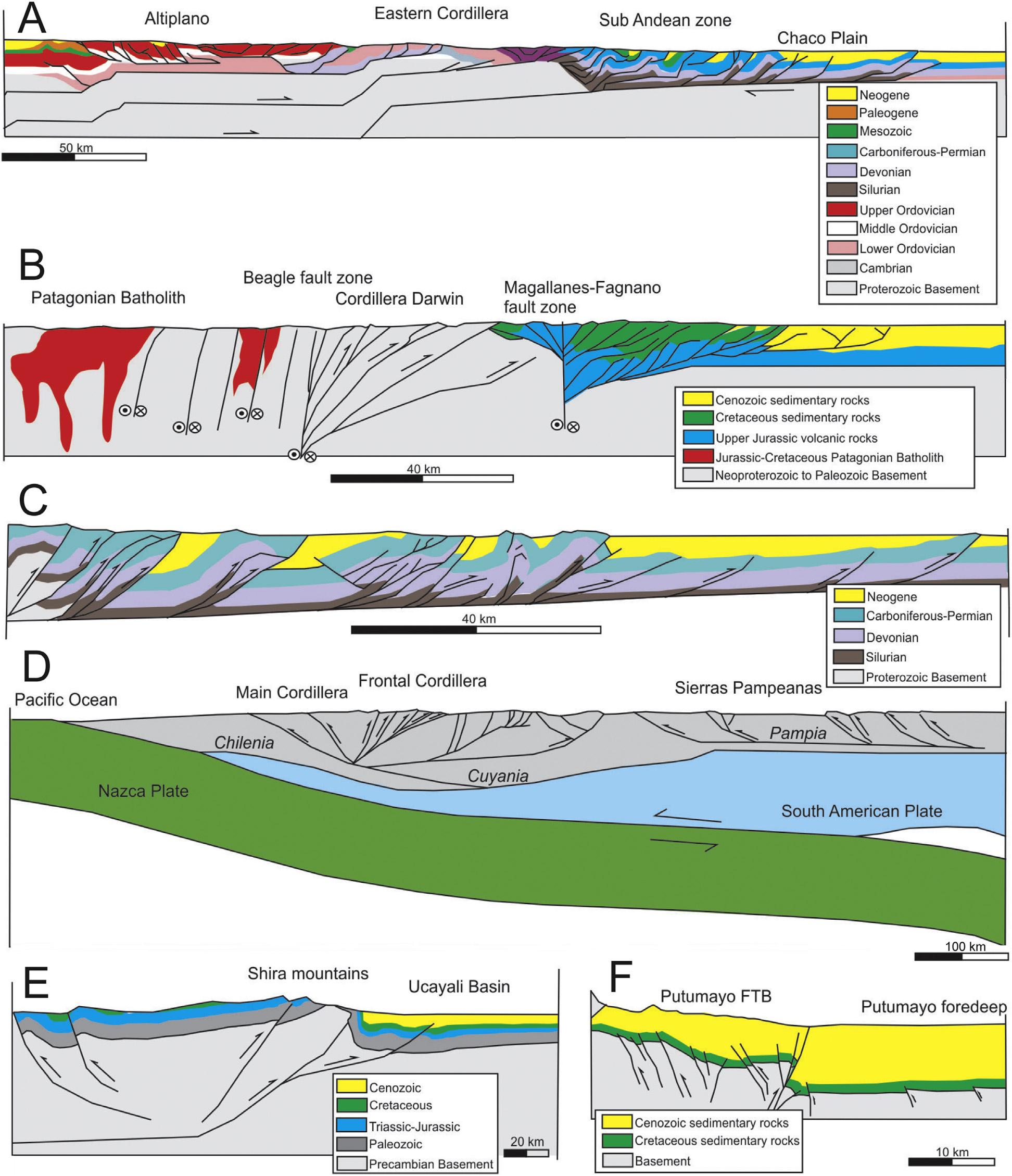

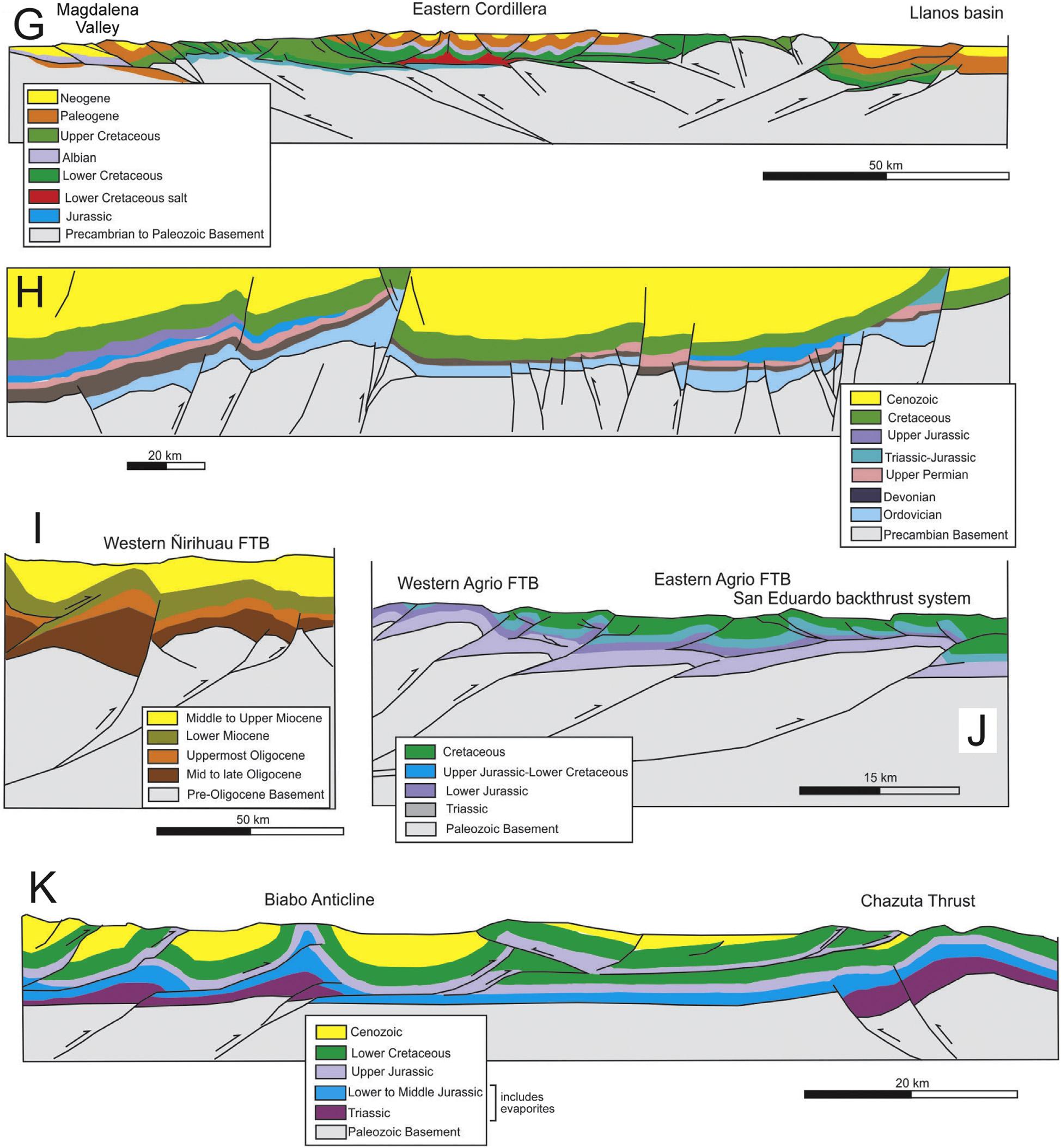

ManystudieshavecategorizedcontrastingtypesofretroarcstructuralsystemswithintheAndesinordertofacilitate comparisonamongdifferentorogenicsegments,developconceptualmodels,andgeneratetestablepredictions(including hydrocarbonplays)(e.g., Kleyetal.,1999; Jacques,2003; Ramosetal.,2004; MacellariandHermoza,2009; McGroder etal.,2015; Zamoraetal.,2019).Hereweidentifyaseriesofrepresentativedeformationalmodes(orstyles)expressed withinretroarcsegmentsoftheAndeanorogenicbelt(Fig.1.4).Thesemodesarenotmutuallyexclusive,asmanyregions havefeaturesemblematicofseveraldifferentstylesandmaybeconsidered “hybrid” systems(e.g., ZamoraValcarceetal., 2006; RojasVeraetal.,2015; Fuentesetal.,2016; McClayetal.,2018; Mackaman-Loflandetal.,2020).Becausethe Andesaredominatedbycoverstrata,withlimitedexposureofigneousormetamorphicbasement,theidenti fiedstylestend tofocusonstructuralrelationshipswithincoverstrata.However,weemphasizethatallofthesedeformationalmodes involvebasementrocks,albeitcommonlyatdepthtowardmoreinternal(hinterland)segmentsoftheorogenicsystem. Further,theselectedexamplescenterondip-slipsystemsbecauseobliquedeformationintheAndeshasbeenaccommodatedpredominantlywithinmagmaticarcandforearcregions.Itisworthnotingthatthisclassi ficationschemedoesnot reducetoasimplebinarythin-skinnedversusthick-skinnedinterpretationofdeformationalprocessesintheAndean orogenicbeltandforelandbasinsystem.

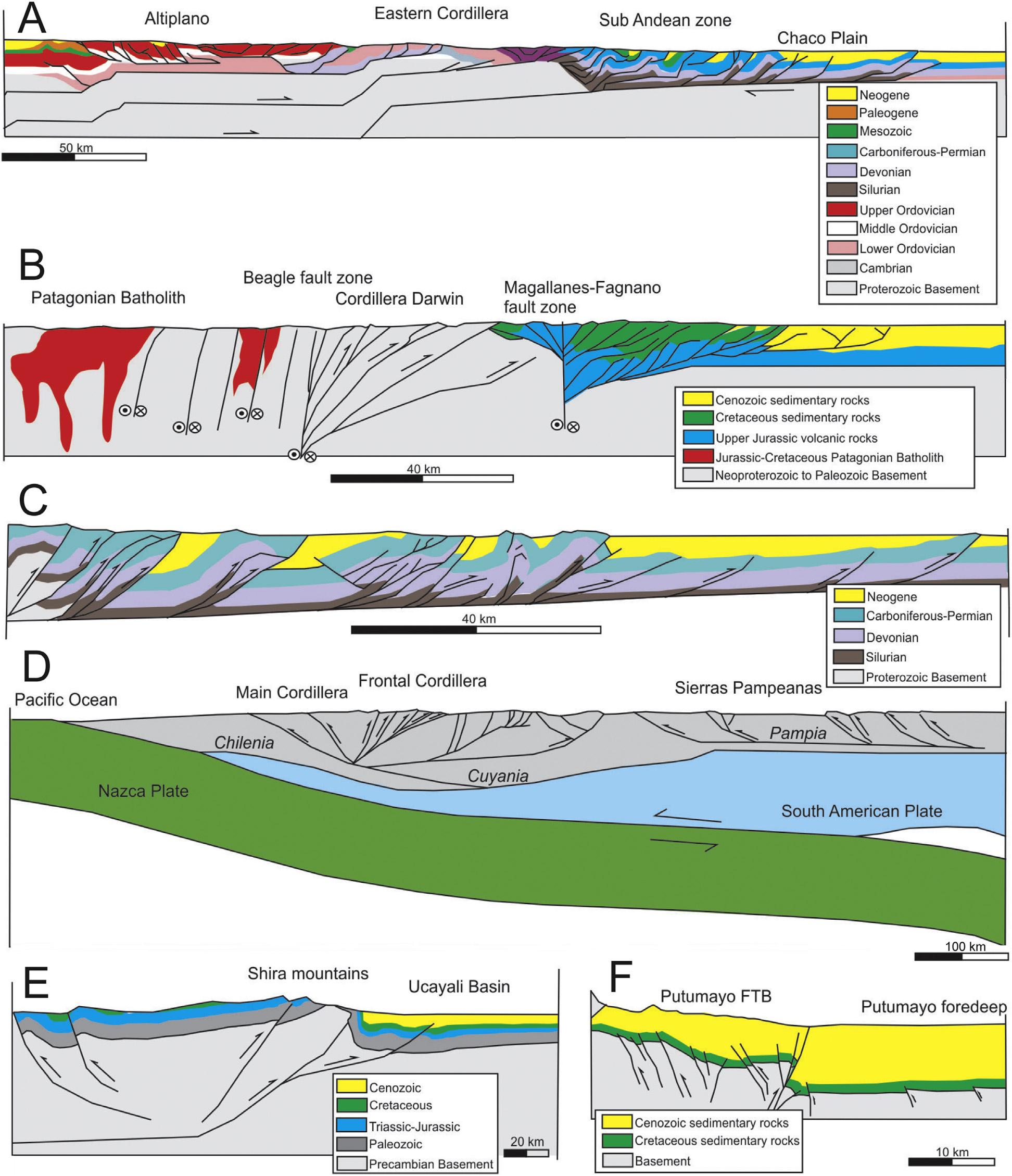

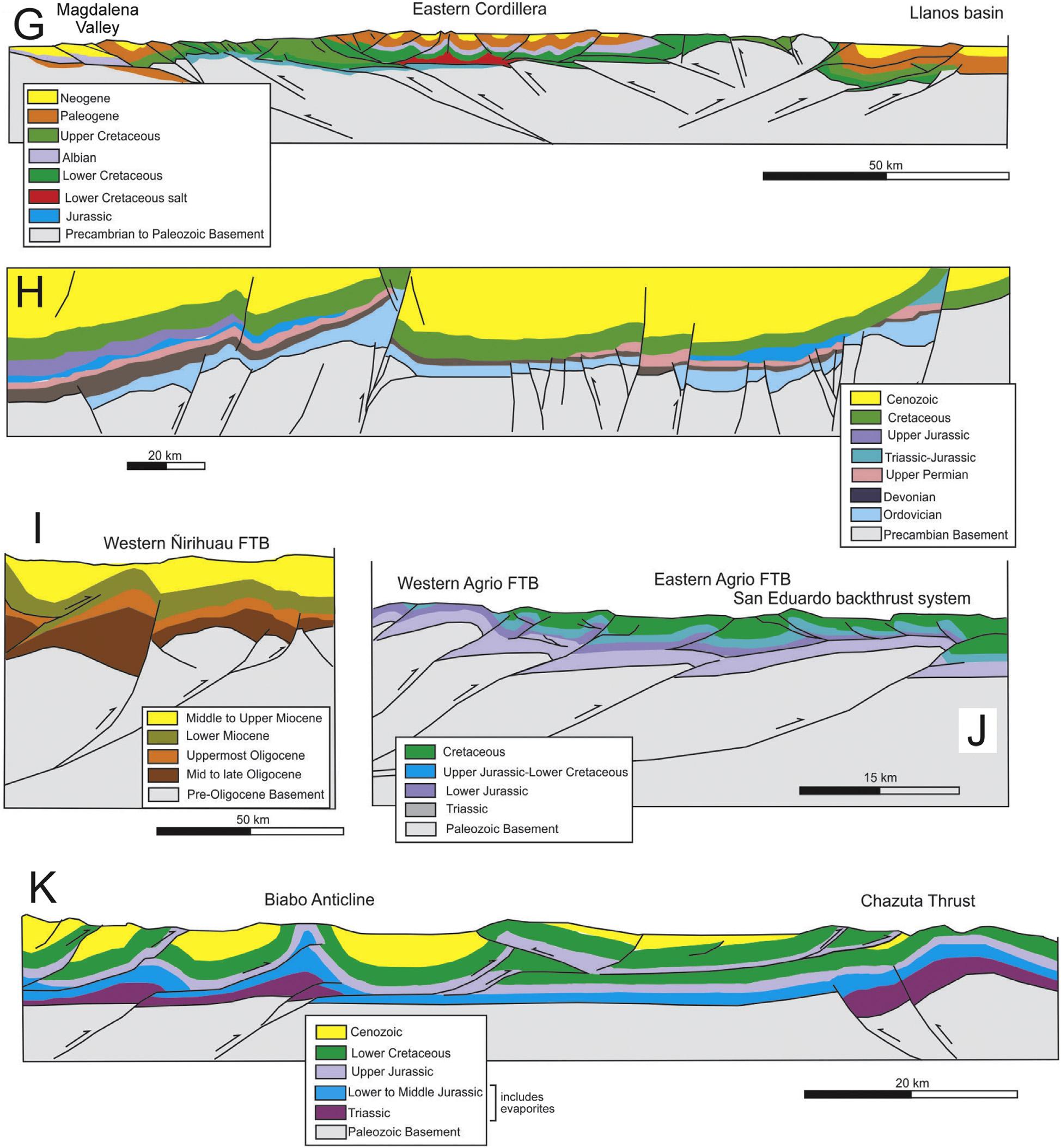

De ´ collement-stylefold-thrustsystems

Adécollement-stylefold-thrustsystem(Fig.1.4A C)involvesmultiplethrustfaultswithramp-flatgeometriesinwhich majorfaultshavelargestrikelength(> 10 50km)andregularlyexhibitlargedip-slipdisplacement(>10km).The principalstructuresincludecraton-directed(east-vergent)thrustfaultsarrangedintoimbricatefansinthefrontalorfoothills zones,withduplexsystemsconcentratedintrailinghinterlandsectors(Fig.1.4AandB)(Babyetal.,1997, 2018; McQuarrie,2002a; Echavarriaetal.,2003; Espurtetal.,2008, 2011; Ghiglioneetal.,2010; Andersonetal.,2017, 2018; Fuentesetal.,2018; McClayetal.,2018; GallardoJaraetal.,2019).Thesefold-thrustsystemsmostlyinvolvesedimentary coverstrata,typicallyawedge-shapedstratigraphicprismthatthickenstowardthewesternmargin.IntheAndes,this inheritedasymmetricwedgemayconstitutedepositsofaPaleozoicpassivemargin,Paleozoicforelandbasin,Mesozoic extensionalbasin,orMesozoicpostextensional(sag)basin.GiventhedominanceofPhanerozoicsedimentaryrocks,these

FIGURE1.4 AseriesofcrosssectionsdepictingAndeanstructuralstyles.(A)Orogenicsectionoftheretroarcfold-thrustbeltinthecentralAndes, southernBolivia,21.5 S(Andersonetal.,2017, 2018).(B)Orogenicprofileoftheretroarcfold-thrustbeltinthesouthernmostAndes,TierradelFuego, ChileandArgentina,53 56 S(GallardoJaraetal.,2019;after Ghiglioneetal.,2010).(C)Crosssectionofthethin-skinnedSubandeanZone,southern Bolivia,21.5 S(Fuentesetal.,2018).(D)OrogenicprofileacrossthecentralChile-Argentina(Pampean) flat-slabsegmentshowingtheretroarcfold-thrust beltofthesoutherncentralAndesandtheadjacentforelandbasementdeformationprovincedefinedbytheSierrasPampeanas,31 S(Pfiffner,2017;after Ramosetal.,2002).(E)Seismic-basedprofileofthebasement-involvedShiraupliftintheproximal(western)forelandbasinofcentralPeru,10 12 S (McClayetal.,2018).(F)Seismic-basedprofileofthetranspressionalbasement-involvedOritosupliftalongtheAndeandeformationfrontandproximal (western)Putumayobasin,southernColombia,1 N(MacellariandHermoza,2009).(G)Orogenicsectionofaninversion-dominatedsegmentofthe EasternCordillera,centralColombia,5 N(Teixelletal.,2015).(H)SeismicinterpretationshowingfaultreactivationandinversionofseveralMesozoic extensionalbasins,Ucayalibasin,centralPeru,8 9 S(McClayetal.,2018).(I)Seismicinterpretationshowingfaultreactivationandinversionofa Cenozoicextensionalbasin,ElMaitenbelt,northernPatagonia,southernArgentina42 S(Ortsetal.,2015).(J)Crosssectionofhinterland-directed backthrustbelt,Agriofold-thrustbelt,westernNeuquénBasinregionwithinthetransitionbetweenthesoutherncentralAndesandnorthernPatagonianAndes,southernArgentina,37.5 S(Lebinsonetal.,2020).(K)Seismicinterpretationshowingsalt-involvedfold-thruststructures,withinterpreted anticlinalthickeningandlarge-scalethrustduplicationofpanelsinvolvingseveralPermian,Triassic,andJurassicevaporiteunits,Huallagabasin,northern Peru,5 7 S(Zamoraetal.,2019; ZamoraandCarter,2022).

systemsarereferredtoas “thin-skinned.” Nevertheless,thesesystemsdoaffecttheupperlevelsofmechanicalbasement (includingPrecambrianandlocallyPaleozoicigneousandmetamorphicrocks),particularlyinhinterlandregions (Fig.1.4AandB)(Schmitz,1994; Kley,1996; SchmitzandKley,1997; Elgeretal.,2005).IntheAndes,withfew exceptions,mostbasementrocksinvolvedinthefold-thrustbeltremainburiedatdepth.

Incontrast,theleadingedgesoftheseramp-flatfold-thrustsystemsinvolveyoungdepositsoftheAndeanforeland basin(Babyetal.,1995; HortonandDeCelles,1997; Echavarriaetal.,2003).Incasesoflarge-scalesubsidenceand sedimentaccumulation,thedeformationfrontisroutinelyburiedbycoarseclasticdepositsoftheproximal(westernmost) forelandbasin(Fig.1.4C).Thefrontalfold-thrustbeltalsoencompassestheregionwherebackthrustandpassive-roof duplexesarebestdeveloped(e.g., Babyetal.,1992; Moraetal.,2014).

FIGURE1.4cont’d

ExamplesincludetheInterandeanandSubandeanzonesofthecentralAndes(Fig.1.4AandC),includingsouthernPeru, Bolivia,andnorthernmostArgentina(Mingrammetal.,1979; Babyetal.,1995, 1997; Dunnetal.,1995; Kley,1996; Moretti etal.,1996; Echavarriaetal.,2003; Andersonetal.,2017, 2018; Fuentesetal.,2018; RojasVeraetal.,2019),andthe PrecordillerainthesoutherncentralAndesofwest-centralArgentina(vonGosen,1992; Ramosetal.,1996; Cristalliniand Ramos,2000; AllmendingerandJudge,2014).Theseeast-directedfold-thrustbeltscontainaseriesofthruststructures involvingmainlyPaleozoicsedimentaryrocksabovearegionaldécollementsituatedinlowerPaleozoicrocksatornearthe basement-coverinterface.Comparablethin-skinnedbeltsinvolvingMesozoicstrataincludefold-thrustsystemsintheTierra delFuegoregionofthesouthernmostAndes(Fig.1.4B)(Alvarez-Marrónetal.,1993; Kraemer,2003)andthenarrow hinterlandAconcaguaandLaRamadasegmentsofthesoutherncentralAndes(CegarraandRamos,1996; Giambiagietal., 2003).Totalhorizontalshorteningmayexceed100 200km,leadingtomajorcrustalthickeningandisostaticsurfaceuplift.

Basement-involvedblockuplifts

Thisstructuralstyleinvolvesisolatedbasementfaults,principallyinforelandregions,thatpenetrateintothemiddleor lowercrust(Fig.1.4D F).Displacementalongsteeplydippingfaultsresultsinaseriesofdisconnectedtopographichighs butmarkedlylimitedhorizontalshortening(generallylessthan20 30km).Crystallinebasementrockscomposemostof thesesystems,withminorinvolvementofathin(<1 2km)sedimentarycover.Thesesystemsarecommonlyreferredto as “thickskinned,” withtheLaramideprovinceofNorthAmericaconsideredtobeanancientanalog(JordanandAllmendinger,1986; YonkeeandWeil,2015).

Individualstructuresareusuallydefinedbysingleisolatedfaultsthatpenetratedowntomiddleorlowercrustallevels (>15 20kmdepth).Thereisnegligibleconnectivityamongindividualbasement-involvedstructures,althoughsplay faultsareobservedintheuppermostcrust.Faultorientationsandvergencedirectionsarehighlyvariable,asmaybe expectedfordeformationofrelativelyhomogeneousgraniticbasementwiththincoverstrata.Thesebasement-involved structuresmayreactivateinheritedpre-Andeannormalfaults,leadingtobasininversion.Inaddition,preexistingbasementfabricsandothermechanicalheterogeneitiesoranisotropiesmayalsoguidestrainlocalizationandfaultnucleation.

TheSierrasPampeanasofcentralArgentina(Fig.1.4D)aretheclassicexampleofthisforelandstructuralstyle,where topographicallyisolated,N-toNNW-trendingbasementhighsaretheproductoflateMiocenetoactivereverse displacementalongindividualfaultsthatpenetratetodeepcrustallevels(Ramosetal.,2002; Cristallinietal.,2004; Vergés etal.,2007; Devlinetal.,2012; Martinoetal.,2016).Thesedisconnectedstructuresinvolvecrystallinebasementrocks, almostexclusively,withthinPhanerozoiccoverstratathathasbeenremovedbysynorogenicerosion.Althoughitis unclearwhetherthedifferentstructuresaregeometricallylinkedatdepth,apotentiallowercrustaldécollementhasbeen depictedinregionalcrustalcrosssections(e.g., Ramosetal.,2002; Giambiagietal.,2015).

Withinupperbasementlevels,therange-boundingfaultsdisplaybothwest-andeast-vergenceandincludetectonic wedgegeometries(Cristallinietal.,2004; Vergésetal.,2007)comparabletoancientLaramideexamplesinwesternNorth America(e.g., Erslev,1993; YonkeeandWeil,2015).Atuppermostcrustallevels,severalreversefaultshavereactivated Cretaceousnormalfaults(e.g., Schmidtetal.,1995; Martinoetal.,2016).Asimilarsetofbasement-involvedstructures characterizetheforelandprovinceofcentralPeru(Fig.1.4E),includingemergentrangessuchastheShiraarch,Contaya arch,andMoaDivisor,aswellasstructuralhighsthatarelargelyburiedbeneathCenozoicbasin fillsuchastheFitzcarrald archandManuarch(Hermoza,2004; Hermozaetal.,2005; Espurtetal.,2007, 2008; AlemánandLeón,2008; Macellari andHermoza,2009; McClayetal.,2018; Babyetal.,2018; Bishopetal.,2018; Zamoraetal.,2019).Inthislow-elevation region,steepbasement-involvedreversefaultsinthesubsurfacehavereactivatedaninheritedsuiteofpre-Cenozoic structuresrelatedtovariableextensional,contractional,and/orstrike-slipdeformation.Animportantsubsetofthis structuralstyleinvolvestranspressionalstructures(Fig.1.4F)inwhichobliquedeformationisaccommodatedbyasingle masterfaultandlinkedsplayfaults,including flowerstructuregeometries.SuchstructuresarewellexpressedinnorthwesternSouthAmerica,wherebasementmassifsareexposedintheEasternCordilleraofColombiaandMeridaAndesof westernVenezuela(Collettaetal.,1997; Velandiaetal.,2005; MacellariandHermoza,2009; Saeidetal.,2017; Kellogg etal.,2019; Moraetal.,2020).

Manyparametersinfluencethedegreeofbasementinvolvementanddeformationadvancetowardthecraton,including therheology,compositionofbasementandcoverrocks,andthegeometryofthesubductingoceanicslab.Theforeland positionsofboththePeruvian(5 15 S)andPampean(27 33 S)basementdeformationalprovinces,whichrepresentthe maximuminboardpenetrationofshorteningtowardtheSouthAmericancraton,correlateremarkablywellwithzonesof lateCenozoic flat-slabsubduction(Figs.1.1and1.2).However,anotherprominentzoneofbasementdeformation the Patagonianbrokenforeland(41 50 S; Echaurrenetal.,2016, 2019; Folgueraetal.,2018) overlapsspatiallywiththe slabwindowgeneratedbyintersectionoftheAntarctic-Nazcaplateboundary(ChileRidge)withthesubductiontrench (Figs.1.1and1.2).

Inversionofpre-Andeanbasins

ReactivationofinheritedMesozoicnormalfaultsandassociatedpre-Andeanextensionalbasinsisaprevalentstructural styleinlargesegmentsoftheAndes.Inmanycases,basin-boundingmasternormalfaultsarereactivatedasthrust/reverse faultsthatinduceupliftandinversionoftheformerlysubsidinghangingwallbasinanditsasymmetrichalf-grabenor symmetricfull-grabengeometries(Fig.1.4GandH)(e.g., Babyetal.,2013; Teixelletal.,2015; McClayetal.,2018; ZamoraandGil,2018).ThisprocessisfundamentalindictatingthepositionofAndeanshorteningandcrustalthickening. Partialorselectivereactivationoftheoriginalextensionalstructuresislargelyrelatedtotheirorientationrelativeto regionalstressdirections(Kleyetal.,2005; Perezetal.,2016a).Andeanshorteningdidnotreactivateallpre-Andean structuresintheirentirety;therefore,someoftheoriginalextensionalstructuresarepreserved,allowingforreconstructionofthedistributionofMesozoicstructuresandextensionalbasins(e.g., McGroderetal.,2015).

Multiplesurfaceandsubsurfaceexamplesoffaultreactivationandbasininversionhavebeenreportedindetail.The northernAndesstandoutasaregionwherepreexistingnormalfaultshaveinfluencedlaterdeformationinareasspanning fromthemagmaticarctodistalforeland(Fig.1.4G).Hinterland-andforeland-directedcontractionalstructuresthat reactivateMesozoicnormalfaultsaredocumentedacrossthethrust-belthinterland,frontalfold-thrustbelt(foothills),and forelandbasinofColombia,Ecuador,andnorthernPeru(Babyetal.,2013).

Inadditiontostrictreactivationofnormalfaultsandinversionofindividualhalfgrabenbasins(Fig.1.4H),thereare alsoexamplesofregionaltectonicinversionofintegratedextensionalbasinsystems.Large-scalereactivationalongthe lengthofmid-crustaldetachmentsinheritedfromMesozoicextensionhelpedshapethesubsequentAndeanstructuralstyle fortheSaltariftsystemofnorthernmostArgentina(22 27 S; Grieretal.,1991; KleyandMonaldi,2002; Pearsonetal., 2013)andtheNeuquénBasinofcentralArgentina(Ramosetal.,2004; ZamoraValcarceetal.,2006; Mescuaetal.,2014; RojasVeraetal.,2015).

Less-commonexamplesinvolvereactivationofpre-AndeanstructuresobliquetothemainAndeantrend,including transverse/transferfaultswithincoverstrata,tearfaultswithinbasement,andcrustalsutures(e.g., Kleyetal.,2005; MosqueraandRamos,2006; Giannietal.,2015; Navarreteetal.,2015).Similarly,someregionspresentlyinforearc positionshaveexperiencedreactivationofMesozoicextensionalandstrike-slipsystems,includingsurfaceandsubsurface examplesintheCoastalCordilleraandCentralDepressionofcentralandnorthernChile(Bascuñánetal.,2016; Boyce etal.,2020; Martínezetal.,2021).

InversionofAndeanextensionalbasins

InversionofCenozoicextensionalbasinsduringsubsequentshorteningaffectedselectedsegmentsoftheAndes.The reactivatedstructuresoriginallyformedinmid-Cenozoicextensionalortranstensionalsettings(Fig.1.4I)withinthe magmaticarcoralongits flanks,ineithertheadjacentarc-forearctransitionorretroarcthrust-belthinterland.Thebestunderstoodexamplesaredefinedbyreactivatedwest-andeast-dippingstructuresinthecentraltosouthernAndesof ChileandwesternmostArgentina,includingtheAbanico,LaRamada,Loncopué,Cura-Mallín,ElMaitén,andTraiguén basinsat28 46 S(Jordanetal.,2001; Charrieretal.,2002; RamosandKay,2006; Amilibiaetal.,2008; Folgueraetal., 2010; Ortsetal.,2012, 2015; Encinasetal.,2016; HortonandFuentes,2016; Mackaman-Lo flandetal.,2019).Such structuresarenotwelldocumentedfarthereastinthefrontalfold-thrustbeltorforelandbasin.

Theseinversionstructureshaveescapeddetectionformanyyears.Fewifanyoftheoriginalextensionalstructuresare preservedatthesurface,suggestingthatnearlyalloftheupper-crustalnormalfaultshavebeenreactivatedasthrust/reverse faults(Fig.1.4I).Suchpervasivereactivationcanbeattributedtothefavorableorientationoftheoriginalnorth-strikingnormal faultsparalleltoregionalAndeantectonicstrikeandperpendiculartoE-Wcompressivestresses(Jaraetal.,2015).Surfaceand subsurfaceexamplesarerecognizedonthebasisofthickmid-Cenozoic(principallyupperEocenetolowerMiocene)basin fill thatdisplaysasharpthicknesscontrastonopposing fl anksofmappedorimagedthrust/reversefaults(e.g., Ortsetal.,2015; Echaurrenetal.,2016; Folgueraetal.,2018).Relativelythickhangingwallversusthinfootwallstratigraphicpackagesattestto earliernormaldisplacementpriortoreversedisplacementandbasininversion.ItmaybespeculatedthatcomparableAndean intraarcorhinterlandsectorsmayhaveexperiencedsimilarmid-Cenozoicextensionfollowedbyinversionduringsubsequent shortening(e.g., Vallejoetal.,2016; Horton,2018a; Georgeetal.,2021).

Backthrustbelts

BackthrustbeltsareasignificantcomponentofhinterlandzonesintheAndeanretroarcfold-thrustbelt.Thesehinterlanddirectedfold-thrustsystemstypicallyinvolveaprincipaldécollementsituatedwithinPaleozoic Mesozoicstrataoratthe

basement-coverinterface(Fig.1.4J)(Kleyetal.,1997; McQuarrieandDeCelles,2001; Armijoetal.,2010; Lebinsonetal., 2020).Thesesystemsinvolvestandardelementsoflargerthrustbelts,withimbricatefangeometriesatshallowlevels commonlyconnectedtotrailingramporduplexstructures.Atdepth,thesebackthrustsystemsaregeometricallylinkedto deeper,basement-involveddeformationunderlyinghinterlandregions(Fig.1.4J)(e.g., McQuarrie,2002a ; Elgeretal., 2005; Riesneretal.,2018).

ThecentralAndeanbackthrustbeltconstitutesthemost-contiguousandhighest-magnitudebackthrustsysteminthe Andes.Thiswest-directedthrustsystemoccupiestheeasternmarginofthecentralAndean(Altiplano-Puna)plateau, persistsalongstrikefor w1200km,from14 Sto25 S,andaccommodated100 200kmofhorizontalshortening (McQuarrieandDeCelles,2001; Carreraetal.,2006; Perezetal.,2016b).Apotentiallysimilarrelationshipisexpressedin Colombia,wherewest-directedthrustfaultsoftheEasternCordilleravergetowardtheMagdalenaValleyhinterlandbasin. Inthiscase,however,thesefaultsdonotclearlymergeintoasingledécollement,butratherrootintodifferentlevelsof crystallinebasement,andlikelyreactivatepre-Andeanextensionalstructures(Moraetal.,2010b; Parraetal.,2012; Sánchezetal.,2012; Tesónetal.,2013; Teixelletal.,2015).

Salt-involvedbelts

Thedistributionofevaporiterockunitshasastronginfluenceontectonicstyleincontractionalsettings.Althoughnot widelydistributed,evaporiteunitsoflatePaleozoictoearlyCenozoicagearepresentinselectedregionsoftheAndean fold-thrustbeltandAndeanforeland.Theseweaksaltunitspreferentiallyformdécollementhorizons,withlateral fl ow resultinginsaltwithdrawalfromsynclinesandaccumulationinthickenedanticlinalstructures(Fig.1.4K,leftmargin). Purelyverticaldiapiricgeometriesarerarelyreported(e.g., Benavides,1968).TheoriginalevaporiteunitsformedpreferentiallyinMesozoicextensionalorpostextensional(sag)settingswithdisconnectedbasins,yieldingadiscontinuous distributionofevaporitefaciesofvariablethicknessandlithology(includinggypsum,anhydrite,andhalite).

MostAndeansalt-involvedstructuresaredocumentedinsurfaceandsubsurfacedatafromthefrontal(eastern)segment ofthefoldthrustbeltoradjacentforelandbasin.InnorthernPeru,theUcayali,Huallaga,Marañon,andSantiagobasins containPermianthroughJurassicsalthorizonsthatactasdécollementhorizonsforseveraltensofkilometersinthedirectionoftectonictransport(AlemánandMarksteiner,1993; GilRodriguezetal.,2001; Morettietal.,2013; Zamoraand Gil,2018; Witteetal.,2018; Zamoraetal.,2019; Carrilloetal.,2021; ZamoraandCarter,2022).Severalconflicting interpretationshavebeenofferedforasubsurfaceexampleassociatedwithhigh-magnitudeshorteningalongtheChazuta thrustfaultintheHuallaguawedge-topbasinofnorthernPeru(Fig.1.4K).Whereassomeproposethata >1kmthicksalt unitofinferredPermianagehasfacilitatedlargelateraltranslationofthesalt-fl ooredChazutathrustsheet w50kmtoward theforeland(Hermozaetal.,2005; Eudeetal.,2015; Calderónetal.,2017; Babyetal.,2018),amoreconservative interpretationinvolvesdiminishedshorteningaccommodatedaboveseveraldifferentsalthorizonsofTriassic-Jurassicage (e.g., McClayetal.,2018; Zamoraetal.,2019).Ineithercase,thenear-surfacemanifestationofstructuralstyleinthis systemisdistinguishedbynarrowdetachmentfoldsandfault-propagationfoldscoredbyevaporites(Fig.1.4K).

Notallevaporitehorizonswithinpre-Andeansuccessionformregionaldécollements.InColombia,Mesozoicevaporite faciesarepresentlocallybutdonotformregionallycontinuouslayerssuitableforstrainlocalizationataregionalscale (Moraetal.,2020).Nevertheless,thesubsurfaceevidenceforsalt-involveddeformationduringlateCenozoicshortening hasbeenreportedalongthedeformationfrontintheEasternCordilleraofColombia.Thisexampleinvolveslocalized inversionofaLateJurassic-EarlyCretaceoushalf-grabenbasin,with flowofweakevaporitesintoahangingwallanticline alongthereactivatedbasin-boundingfault(Parravanoetal.,2015).Althoughthinandspatiallylimitedevaporitehorizons maynotformregionaldécollementsorfosterlargelateral flow,theymayservetocompartmentalizedeformationsuchthat geometriccontrastsinfaultspacingandstructuralwavelengthareexpressedaboveandbelowtheevaporiteunit (e.g., ZamoraValcarceetal.,2006; Fuentesetal.,2016).

Summaryanddiscussion

Differentmodesoftectonicinheritance

ArangeofAndeanstructuralstylescanbeascribedinvaryingdegreestofourdifferentmodesoftectonicinheritance (Fig.1.3).Theseinclude(a) structuralinheritance withstrainlocalizedalongbasementfabricsandpreexistingfaults (includingtheprocessofbasininversion);(b) stratigraphicinheritance inwhichtheprecursorbasinarchitecturepromoteseitherinterconnectedramp-flatstructuresorisolatedsteepfaultspenetratingtodeepcrustallevels;(c) rheological inheritance wherenewstructuresareguidedbythestrength,composition, fluidcontent,andaccompanyingheterogeneitiesandanisotropieswithinthepreorogeniccrustal/lithosphericcolumn;and(d) thermalinheritance suchthatinitial thermalstatesandrapidthermalperturbationsinfluencethedeformationalresponse.

DistinctstructuralstylesintheAndescanbeassociatedwithinheritedstructural,stratigraphic,rheological,orthermal conditions.Forexample,theemergenceoframp-fl atdécollement-stylefold-thrustsystemsinvariablyinvolvessuitable stratigraphicgeometrieswithinheritedanisotropiesinthestratalsuccession,alongthebasement-coverinterface,and/or withinupperbasementlevels.Inadditiontotheactivationofdécollementlevelsalongrelativelyweakerrockunits(notably shalesandevaporites),thepositionofmajorrampsiscommonlylinkedtoinheritedstratigraphicarchitecture,including lateralthicknessvariations(suchasthetransitionfromthinshelffaciestothickslopefacies)andthelateralpinchoutof weakerhorizons.Incontrast,thedevelopmentofdisconnectedreversefaultsdefinedbycrustal-scalerampsisenhancedin provinceswithlimitedcoverstrata,fewersupracrustalanisotropies,andrelativelyhomogeneousbasementmaterial.

ManyindividualAndeanstructurescannotbeuniquelyassignedtoasinglemodeoftectonicinheritance.Giventhe complexpre-AndeanhistoryofthewesternmarginofSouthAmerica,thefourdifferentmodesoftectonicinheritancehave likelyoverlappedintimeandspace.Moreover,temporalandspatialassociationsbetweenspeci ficinheritedelementsand anobservedstructuralstyledonotnecessarilyconstitutesimplecause-effectrelationships.Inmostcases,itwouldbean overstatementtostatethatasingleinheritedfeatureexclusivelydictatedthedeformationstyleofaparticulararea.

Insightscanbegainedthroughconsiderationoftheexpectedvariationsinstructuralreactivationandstrainlocalization duringprogressiveorogenesis.Severalstudieshavesuggestedthatcontractionalinversionofpreexistingextensional structuresmayberegionallywidespreadandmostpronouncedduringtheearliestphasesoforogenesis,priortothe establishmentofgeometricallyandkinematicallylinkedfold-thruststructures(e.g., Ziegleretal.,1995; Beaumontetal., 2000; KleyandVoigt,2008; Babyetal.,2013; Ghiglioneetal.,2014; Wolfetal.,2021).Others,however,havesuggested adelayinstrainlocalizationalonginheritedextensionalstructuresinwhichthelocusofshorteningshiftsfromaprincipal décollementalongthebasement-coverinterfacetomidcrustallevelsinfl uencedbytherheologicalframeworkinherited fromearlierextension(e.g., LacombeandMouthereau,2002; Nemcoketal.,2013; LacombeandBellahsen,2016; Tavani etal.,2021).Thesecontradictoryperspectivesunderscoretheneedforimprovedlong-termgeologicrecordsthatwill illuminatetemporalshiftsindeformationstyle,expandcomparativestudyoflow-versushigh-shorteningorogens,and improvecomparisonsoforogenichistorieswithpredictionsfromnumericalandthermo-mechanicalmodels (e.g., Beaumontetal.,2000, 2006; Babeykoetal.,2006; JamiesonandBeaumont,2013; JammesandHuismans,2012; Jammesetal.,2014; Tavanietal.,2021; Barrionuevoetal.,2021; Ibarraetal.,2021; Wolfetal.,2021).

Inpractice,considerationofthepredeformationalcontextforaparticularregioncanhelpidentifythecollectionoflocal andregionalattributesthataffecteddeformationintheAndesanditadjacentforeland.Asapotentialworkflow,apurposefulidentificationofthepredecessorstructuralframework,predeformationalstratigraphicarchitecture,crustal/lithosphericrheology,andthermalstructureislikelytoyieldagreaterappreciationforthecontrolsonstructuralstyle,intime andspace,andthusaidinthecreationofviableanalogsandtestablepredictionsforcontractionalorogenicsettings.

Tectonicdriversandcontrols

Andeanorogenesisisroutinelylinkedtoexternaldriversorcontrolssuchastherateanddirectionofocean-continentplate convergence,mechanicalcouplingalongthesubductingplateinterface,thedipofthesubductingslab,interactionswith subductingridges,accretionofoceanicmaterials,andtheinfluenceofarcmagmatism(e.g., James,1971; Rutland,1971; Pardo-CasasandMolnar,1987; Mégard,1989; AlemanandRamos,2000; Jordanetal.,2001; KayandCoira,2009; Maloney etal.,2013).Althoughtheseprocessesplayimportantroles,therearealsointernalcrustalandlithosphericelementsthat shapedtheconstructionoftheAndes(e.g., Nemcoketal.,2013; McGroderetal.,2015).Speci fically,suchintrinsicor inheritedpropertiesmayhelpexplainsomeoftheprominentspatialvariationsalongthe w8000kmlengthoftheorogen.

To firstorder,theentireAndeanmarginhasexperiencedaremarkablysimilarplatetectonichistoryoverthepast w120 Myr,withSouthAmericabreakingawayfromAfricaandadvancinguniformlywestwardwithminimaltectonicrotation andnegligiblelatitudinalvariation(Silveretal.,1998; SomozaandGhidella,2012).Despitethissharedhistory,the westernedgeofSouthAmericadisplayssharpchangesintopography(includingtheaverageorogenicelevationand width),magnitudeofdeformation(withvariedlow-,moderate-,andhigh-shorteningregimes),andaremarkablydiverse arrayofstructuralstyles(Kleyetal.,1999; Jacques,2003; Ramosetal.,2004; MacellariandHermoza,2009; Ramos, 2009; Moraetal.,2010a; Giambiagietal.,2012; Horton,2018a; McClayetal.,2018; Zamoraetal.,2019).

Along-strikevariationsintheinboardextentofcontractionaldeformation(Figs.1.1and1.2)arepronounced,butnot entirelyclearintheirorigin.Twozonesof flat-slabsubduction thePeruvian flatslab(5 15 S)andtheChilean/Pampean flatslab(27 33 S) correlateremarkablywellwithfarinboard(trench-perpendicular)penetrationofcrustaldeformation (Fig.1.2).Ifspatialcolocationisregardedascausality,thentheseprovincesofforelandbasementdeformationcanbe geneticallyattributedtoslabdip(e.g., Jordanetal.,1983; Ramos,1999, 2009; RamosandFolguera,2009; Bishopetal., 2018).Nevertheless,despitetheappealofthisinterpretation,severalobservationssuggestthat flat-slabsubductionaloneis neithernecessarynorsuffi cientforthedevelopmentofinboardbasementdeformationorextremeorogenicwidth.First, basement-involveddeformationinthePatagonianforeland(41 50 S; Echaurrenetal.,2016, 2019; Folgueraetal.,2018)