https://ebookmass.com/product/an-integrated-index-engramsplace-cells-and-hippocampal-memory-travis-d-goode-kazumasaz-tanaka-amar-sahay-thomas-j-mchugh/

Instant digital products (PDF, ePub, MOBI) ready for you

Download now and discover formats that fit your needs...

Elsevier Weekblad - Week 26 - 2022 Gebruiker

https://ebookmass.com/product/elsevier-weekbladweek-26-2022-gebruiker/

ebookmass.com

Jock Seeks Geek: The Holidates Series Book #26 Jill Brashear

https://ebookmass.com/product/jock-seeks-geek-the-holidates-seriesbook-26-jill-brashear/

ebookmass.com

The New York Review of Books – N. 09, May 26 2022 Various Authors

https://ebookmass.com/product/the-new-york-review-ofbooks-n-09-may-26-2022-various-authors/

ebookmass.com

Gentrifier John Joe Schlichtman

https://ebookmass.com/product/gentrifier-john-joe-schlichtman/

ebookmass.com

Portfolio Selection and Asset Pricing: Models of Financial Economics and Their Applications in Investing Erol Hakanoglu

https://ebookmass.com/product/portfolio-selection-and-asset-pricingmodels-of-financial-economics-and-their-applications-in-investingerol-hakanoglu/ ebookmass.com

Socio-Economic Environment and Human Psychology: Social, Ecological, and Cultural Perspectives Ay■e K. Üskül

https://ebookmass.com/product/socio-economic-environment-and-humanpsychology-social-ecological-and-cultural-perspectives-ayse-k-uskul/

ebookmass.com

Communication Between Cultures 8th Edition, (Ebook PDF)

https://ebookmass.com/product/communication-between-cultures-8thedition-ebook-pdf/

ebookmass.com

Wings Once Cursed & Bound Piper J. Drake

https://ebookmass.com/product/wings-once-cursed-bound-piper-j-drake/

ebookmass.com

Teaching ELLs Across Content

Areas (NA) https://ebookmass.com/product/teaching-ells-across-content-areas-na/

ebookmass.com

https://ebookmass.com/product/whispers-of-the-deep-deep-watersbook-1-emma-hamm/

ebookmass.com

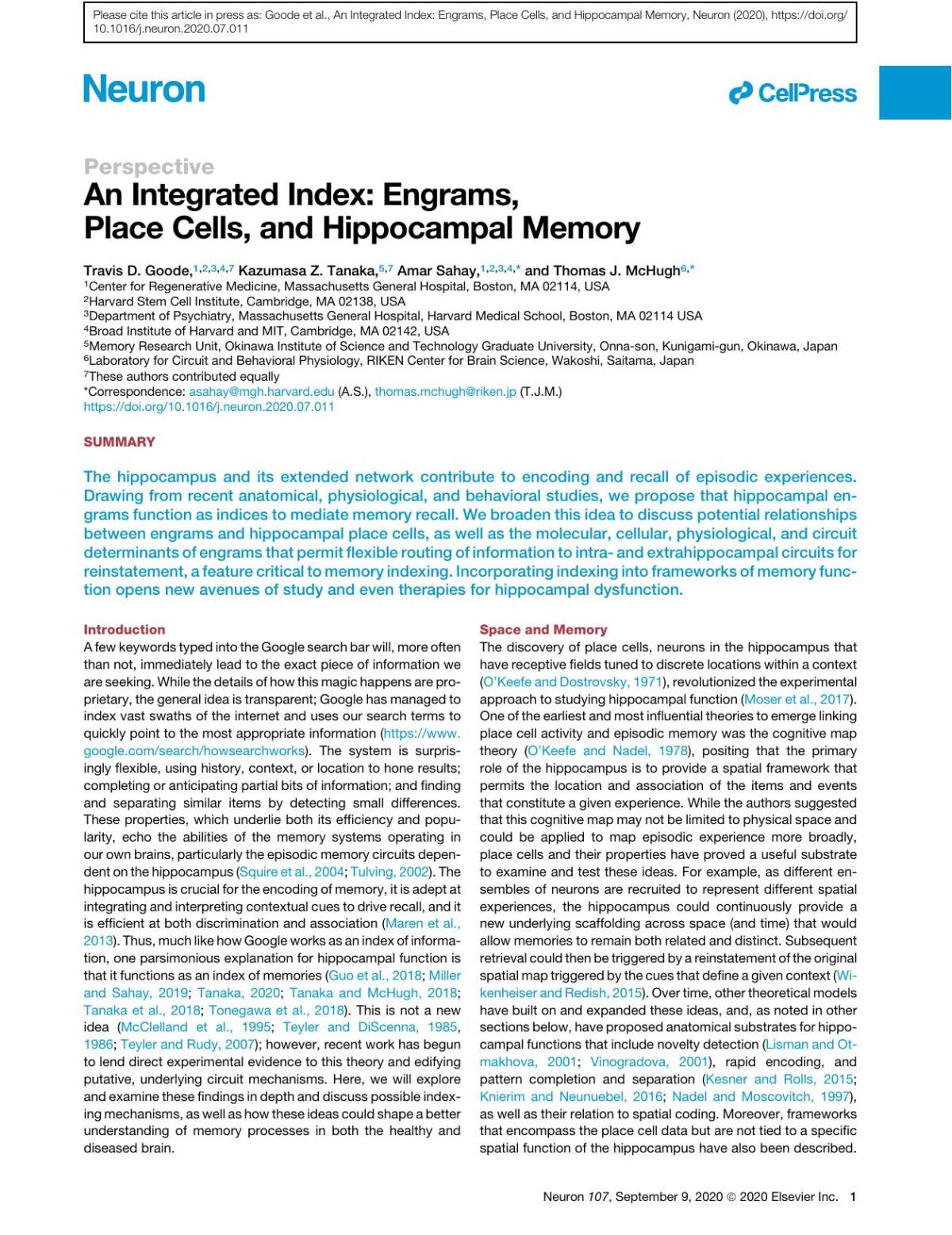

AnIntegratedIndex:Engrams, PlaceCells,andHippocampalMemory TravisD.Goode,1,2,3,4,7 KazumasaZ.Tanaka,5,7 AmarSahay,1,2,3,4,* andThomasJ.McHugh6,* 1CenterforRegenerativeMedicine,MassachusettsGeneralHospital,Boston,MA02114,USA 2HarvardStemCellInstitute,Cambridge,MA02138,USA 3DepartmentofPsychiatry,MassachusettsGeneralHospital,HarvardMedicalSchool,Boston,MA02114USA 4BroadInstituteofHarvardandMIT,Cambridge,MA02142,USA

5MemoryResearchUnit,OkinawaInstituteofScienceandTechnologyGraduateUniversity,Onna-son,Kunigami-gun,Okinawa,Japan 6LaboratoryforCircuitandBehavioralPhysiology,RIKENCenterforBrainScience,Wakoshi,Saitama,Japan 7Theseauthorscontributedequally *Correspondence: asahay@mgh.harvard.edu (A.S.), thomas.mchugh@riken.jp (T.J.M.) https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuron.2020.07.011

SUMMARY

Thehippocampusanditsextendednetworkcontributetoencodingandrecallofepisodicexperiences. Drawingfromrecentanatomical,physiological,andbehavioralstudies,weproposethathippocampalengramsfunctionasindicestomediatememoryrecall.Webroadenthisideatodiscusspotentialrelationships betweenengramsandhippocampalplacecells,aswellasthemolecular,cellular,physiological,andcircuit determinantsofengramsthatpermitflexibleroutingofinformationtointra-andextrahippocampalcircuitsfor reinstatement,afeaturecriticaltomemoryindexing.Incorporatingindexingintoframeworksofmemoryfunctionopensnewavenuesofstudyandeventherapiesforhippocampaldysfunction.

Introduction

AfewkeywordstypedintotheGooglesearchbarwill,moreoften thannot,immediatelyleadtotheexactpieceofinformationwe areseeking.Whilethedetailsofhowthismagichappensareproprietary,thegeneralideaistransparent;Googlehasmanagedto indexvastswathsoftheinternetandusesoursearchtermsto quicklypointtothemostappropriateinformation(https://www. google.com/search/howsearchworks ).Thesystemissurprisinglyflexible,usinghistory,context,orlocationtohoneresults; completingoranticipatingpartialbitsofinformation;andfinding andseparatingsimilaritemsbydetectingsmalldifferences. Theseproperties,whichunderliebothitsefficiencyandpopularity,echotheabilitiesofthememorysystemsoperatingin ourownbrains,particularlytheepisodicmemorycircuitsdependentonthehippocampus(Squireetal.,2004; Tulving,2002).The hippocampusiscrucialfortheencodingofmemory,itisadeptat integratingandinterpretingcontextualcuestodriverecall,andit isefficientatbothdiscriminationandassociation(Marenetal., 2013).Thus,muchlikehowGoogleworksasanindexofinformation,oneparsimoniousexplanationforhippocampalfunctionis thatitfunctionsasanindexofmemories(Guoetal.,2018; Miller andSahay,2019; Tanaka,2020; TanakaandMcHugh,2018; Tanakaetal.,2018; Tonegawaetal.,2018).Thisisnotanew idea(McClellandetal.,1995; TeylerandDiScenna,1985, 1986; TeylerandRudy,2007);however,recentworkhasbegun tolenddirectexperimentalevidencetothistheoryandedifying putative,underlyingcircuitmechanisms.Here,wewillexplore andexaminethesefindingsindepthanddiscusspossibleindexingmechanisms,aswellashowtheseideascouldshapeabetter understandingofmemoryprocessesinboththehealthyand diseasedbrain.

SpaceandMemory Thediscoveryofplacecells,neuronsinthehippocampusthat havereceptivefieldstunedtodiscretelocationswithinacontext (O’KeefeandDostrovsky,1971),revolutionizedtheexperimental approachtostudyinghippocampalfunction(Moseretal.,2017). Oneoftheearliestandmostinfluentialtheoriestoemergelinking placecellactivityandepisodicmemorywasthecognitivemap theory(O’KeefeandNadel,1978),positingthattheprimary roleofthehippocampusistoprovideaspatialframeworkthat permitsthelocationandassociationoftheitemsandevents thatconstituteagivenexperience.Whiletheauthorssuggested thatthiscognitivemapmaynotbelimitedtophysicalspaceand couldbeappliedtomapepisodicexperiencemorebroadly, placecellsandtheirpropertieshaveprovedausefulsubstrate toexamineandtesttheseideas.Forexample,asdifferentensemblesofneuronsarerecruitedtorepresentdifferentspatial experiences,thehippocampuscouldcontinuouslyprovidea newunderlyingscaffoldingacrossspace(andtime)thatwould allowmemoriestoremainbothrelatedanddistinct.Subsequent retrievalcouldthenbetriggeredbyareinstatementoftheoriginal spatialmaptriggeredbythecuesthatdefineagivencontext(WikenheiserandRedish,2015).Overtime,othertheoreticalmodels havebuiltonandexpandedtheseideas,and,asnotedinother sectionsbelow,haveproposedanatomicalsubstratesforhippocampalfunctionsthatincludenoveltydetection(LismanandOtmakhova,2001; Vinogradova,2001),rapidencoding,and patterncompletionandseparation(KesnerandRolls,2015; KnierimandNeunuebel,2016; NadelandMoscovitch,1997), aswellastheirrelationtospatialcoding.Moreover,frameworks thatencompasstheplacecelldatabutarenottiedtoaspecific spatialfunctionofthehippocampushavealsobeendescribed.

Thesepositthatplacecellsmayreflectabroaderfunctionality relatedtogeneral-purposesequencegeneration(Buzsakiand Tingley,2018)orrelationalmemory(CohenandEichenbaum, 1993; Eichenbaumetal.,1994),allowingtheextensionofboth hippocampalmemoryandphysiology(Aronovetal.,2017; MacDonaldetal.,2011; Pastalkovaetal.,2008)beyondthedomain ofphysicalspace.

Handinhandwiththegrowingcharacterizationofplacecell physiology,theredevelopedadeeperunderstandingofthe anatomical,behavioral,andcomputationalpropertiesofthehippocampalcircuit.Thisresultedinspecificmnemonicfunctions beinglinkedtotheanatomicandphysiologicalpropertiesof discretesubregionsofthestructure(FanselowandDong,2010; Nadeletal.,2013; Strangeetal.,2014).Inthisframework,the classicmodelofsequentialprocessingalongthetrisynaptic loophasthelargenumberandsparseactivityofgranulecellsin thedentategyrus(DG)providingorthogonalizationofsimilar corticalinputsleadingtopatternseparation(HainmuellerandBartos,2020; LealandYassa,2018; McHughetal.,2007),theDG providinginputtotherecurrentCA3networktofacilitateautoassociationandpatterncompletion(Cayco-GajicandSilver,2019; KesnerandRolls,2015; KnierimandNeunuebel,2016; McHugh etal.,2007; Nakazawaetal.,2002),andfinally,CA1broadcasting theresultsbacktothecortex(SolteszandLosonczy,2018; Valero anddelaPrida,2018).Thisframeworkhasservedasthebackboneofrelatingplacecellactivitytomemoryprocessing,insofar asplacecellsmaycoordinatethepatternseparation,completion, andreinstatementpropertiesnotedabove.

Buildingonthisframework,advancesingeneticapproaches haveledtoactivity-dependentmemorytaggingsystemsin rodentmodels,whichallowfortheexaminationandartificialreactivationorinhibitionofdistinctmemorytraces(Josselynand Tonegawa,2020).Thesetracesfulfillthepropertiesofthememoryengram,amonikerforthephysicalbasisofmemoryfirstproposedbyzoologistandbiologistRichardSemon(Schacteretal., 1978; Semon,1921),inthattheycanbeviewedasthephysical instantiationofanexperienceregisteredinenduringchanges insynapticconnectivityandphysiologyofanensembleof neurons.Taggingsystemsemployedincludethetetracyclineregulatedtranscriptionalactivationsystem,inwhichtime-locked expressionofactuatorssuchasopsinsorchemogeneticreceptorsareinducedviaactivity-dependentpromoters(e.g.,c-FosorArc-expressing; Liuetal.,2012)orimmediateearlygene (IEG)-bindingelements(Sunetal.,2020),aswellastheCreERT(estrogenreceptorT2)transcriptionsystem(targeted recombinationinactivepopulations[TRAP]mice),whichutilizes atamoxifen-sensitivemodifiedestrogenreceptortodriveexperience-drivenexpressionofCre-dependentconstructsinactivatedcells(Guenthneretal.,2013).Suchmethodshaveallowed fortheartificialtriggeringofmemory-relatedbehaviorevenin contextswherenosuchbehaviorwouldbeexpected.While thesemethodsarenotwithouttheircaveats(discussedfurther insectionsbelow),engram-labelingstudieshaveshownthatoptogeneticorchemogeneticstimulationorinhibitionofexcitatory neuronsintheDG(e.g., Guoetal.,2018; Lacagninaetal.,2019; Liuetal.,2012),CA3(e.g., Dennyetal.,2014),orCA1(e.g., Ghandouretal.,2019; Ryanetal.,2015; Tanakaetal.,2014)reinstatesorimpedes(respectively)behavioralrecallofthatexpe-

Perspective rience.Whilemanyengramstudieshavefocusedonmeasures ofconditionedfear,theseandotherstudiesreporthippocampal engram-drivenbehaviorforavarietyofcontext-specificbehaviors,includingplace(e.g., Ramirezetal.,2013)orsocialavoidance(e.g., Zhangetal.,2019),aswellasappetitiveconditioning andplacepreference(e.g., Redondoetal.,2014).

Thesefindingsraiseseveralkeyquestions.First,howcana smallnumberofexperience-taggedhippocampalengramcells, muchfewerinfractionthanthatofactiveplacecells(e.g., Tanaka etal.,2018),encodeacomplexbehavioralexperience?Indeed, activationofaverysmallpercentage(2%–3%)ofDGgranule cellslabeledduringlearningcanreproducecontext-appropriate behaviors(forexamples,see Liuetal.,2012).Further,activation intheDGcouldharnessthepatterncompletionabilitiesofthe downstreamCA3networktoamplifytheiractivityviaattractor dynamics(Colginetal.,2010; KnierimandNeunuebel,2016) andleadtoarobustbrain-widereinstatementofamemoryrelatedensemble.However,reactivationofasubsetofCA1 neurons,whichlackrecurrentconnectivity,canalsotrigger behavioralreinstatementandpresumablymemoryrecall(e.g., Ryanetal.,2015).Itisplausiblethatdownstreamactivationof theentorhinalcortex(EC)and/orre-entrantexcitationofthe DGandCA3addthesefeatures,therebyfunctioninglikearecurrentnetwork,althoughexperimentalevidencesupportingthis interpretationislacking.

Additionally,50yearsofhippocampalphysiologyinrodents hasrevealedthatplacecellactivityisexquisitelystructured acrossnotonlyspacebutalsotime(HowardandEichenbaum, 2015).Duringexploration,thedominantthetaoscillationinthe hippocampallocalfieldpotential(LFP)organizesensemblesof placecellswithspatiallyadjacentreceptivefieldsintosequences,expressedonthetimescaleofasinglethetacycleof 125ms(BurgessandO’Keefe,2011).Thesesequencescan bere-expressedduringsharp-waveripples(SWRs)thatoccur duringpausesinmovementonanevenshortertimescale,compressedintofasteventslastingonly10sofmilliseconds(Foster, 2017).Thisprecisetemporalarrangementofactivityhasmade thegapbetweenplace-cell-andengram-basedmemorystudies difficulttobridge,asthelatterhavedemonstratedthat simultaneousoptogeneticactivationofensemblesofneurons intemporalandspatialpatternsthatarenotobservedundernaturalphysiologicalconditionsaresufficienttoevokebehaviors mimickingmemoryrecall.Onecaninterpretthisgapinthetemporaldynamicsbetweenopticallyinducedbehavioralreinstatementandplacecellactivityasreflectingthedispensabilityof thesetemporalpatternforbehaviorsdrivenbycontextualrecognition,orperhapsthisdisconnectcouldsimplybeduetotechnicallimitationsintheplacecellrecording,astheretrievalofa hippocampal-dependentmemorycanoccurveryrapidlyandin theabsenceoftheexplorationneededtodriveextensiveplace cellactivity,precludingarobustsamplingofactivity.For instance,whenrodentsreceiveafootshockimmediatelyafter placementinapreviouslyexposedchamber,contextexplorationmaybeminimal,yetanimalssuccessfullyretrievethe contextualmemoryandassociateitwithshock,resultingin context-dependentbehaviorduringsubsequentmemorytests (Wiltgenetal.,2001).Onepossibilityisthatreinstatementof evenasingleplacefieldissufficientformemoryreinstatement.

Figure1.ComparingandContrastingHippocampalPlaceCellsand Engram-Tagged(ImmediateEarly-Gene-Expressing)Neurons Placecellactivityhasprecisetemporalstructureduringbothexplorationand rest,whereasengram-taggedneuronsaresimultaneouslyandexperimentally reactivated.Placecelldensityappearsmoderate,andthisdensityofactive placecellsisrelativelystableinanygivencontext.Conversely,engram-tagged cellsinthehippocampusaresparse,withfamiliarcontextsexhibitinglow levelsoftaggedexpression.Engramcellsexhibitconsiderablylessstabilityin theircontext-dependentreinstatementovertimeascomparedtoplacecells, althoughbotharehighlyunstablewithtime.Remotetimepointsforreactivationofexperience-dependentengramcellsremainunknown.While thereareoverlappingbehavioralcorrelatesofplaceandengramcellactivity, placecellresearchhasledthefieldinitscorrelationtobehavior.

However,long-termmonitoringofthestabilityofplacecell representationsacrossrepeatedvisitsonthetimescaleof weeks,nowpossibleduetoadvancesin invivo imagingapproachesinmice,suggeststhatthereexistsahithertounappreciatedhighdegreeofinstabilityinthespatialrepresentationofa familiarenvironment(Zivetal.,2013;but,alsosee(Gonzalez etal.,2019).Ifonlyafraction( 15%)ofplacecellsshowstability

acrossseveralweeks,itbecomesmoredifficulttodrawadirect connectionbetweenmemoryrecallandacompletelystable spatialrepresentation.Itispossiblethatasmallfractionofstable placecellscanserveasapartialcuetoreinstatethefullrepresentationofmemorythroughaprocessofpatterncompletion indownstreamregions;however,thisviewischallengedbya recentstudyexaminingthephysiologicalnatureofengramcells inthehippocampus,whichisdiscussedbelow(Tanakaetal., 2018).Thus,whileplacecellstudieshaveprovidedinsightinto theanatomicalorganizationandpotentialmemorymechanisms ofthehippocampus,we,likemanyothers,struggletoreconcile thesepotentialspatialcodingpropertieswiththecoreroleofthe systemasamemorystoragedevice(Tanaka,2020).Further,itis important,boththroughhypothesisandexperiments,toattempt toidentifytherulesoftransformationthatallowsimultaneous activationofhippocampalengramstogenerateappropriatepatternsofdownstreamactivationandbehavior(Lismanetal., 2017).Perhapsthen,weshouldreconsiderwhattheactivityof hippocampalneuronsduringmemoryformationandrecalltruly representsandhowplacecellsthathavedrivenmuchofthe thinkinginthefieldforthelast50yearscaninformusabout thehippocampusasamemorysystem(Figure1).

InstantiatingtheHippocampalIndex

Thehippocampalmemoryindexingtheorypositsthatthehippocampusdoesnot‘‘contain’’theepisodicmemoryitself;rather,it generatesacodeor‘‘index’’thatbindsneuronalactivitypatterns underlyinganexperientialevent,whichisstoredacrossdistributedneocortical(andpotentiallysubcortical)modules(Teyler andDiScenna,1985, 1986; TeylerandRudy,2007).Inother words,thehippocampusencodesalinkedrepresentationof brainactivityatthetimeofanexperienceorepisode,which cansubservesubsequentrecallviaactivationofthathippocampalrepresentation.Whatispresumedtomakethesepatternsof activityuniquefromotherexperience-inducedpatternsinthe brain,suchasensembleactivityinthesensorycortexactivated byastimulus,istheirconjunctiveandassociationalnatureand theabilityofthehippocampalensembletoreinstatetheoriginal spatialandtemporalpatternsofcortical/subcorticalactivityofan experience(McClellandetal.,1995; TeylerandRudy,2007). Importanttonoteisthattheindexingtheoryisnotmutually exclusivetothecognitivemaptheory.Instead,itsimplyremains agnostictowhat,ifanything,thehippocampalneuronsinvolved inmemoryindexingmustrepresentintermsofbehaviorallyrelevantinformation;spatialcodingwouldbeacceptableifthese neuronshadpropertiesconsistentwiththatofanindex,assummarizedandpresentedin Figure2.Inthefollowingandsubsequentsections,weelaborateonthesefeaturesanddiscuss howthebrain’scircuitarchitecturesupportsaviewofhippocampalfunctionthroughthelensofindexing.

EngramsasIndices

Numerousstudieshavenowshownthatphotoactivationofa sparsehippocampalengramdrivesIEGactivityinselectdownstreambrainregionsthoughttobeinvolvedintheoriginal learning(e.g., Ramirezetal.,2013, 2015; Royetal.,2017). Suchobservations,togetherwiththereinstatementofbehavior followingoptogeneticengramstimulation,supporttheidea thatthehippocampusiscapableofindexingandtriggering

memoryrecallbyreinstatinglearning-dependentactivityin memory-relatedextrahippocampalbrainsystems.However, increasedIEGinductioninextrahippocampalstructures followingartificialactivationofengram-bearinghippocampal cellsdoesnotnecessarilyindicatethatthesearethepreciseextrahippocampalneuronsinvolvedintheoriginallearning.Moreover,specificcontrols,suchasuntagged,context-exposed andnonreinforcedanimals,areoftenessentialtoaddressissues ofmemoryversusperformance;indeed,animalsmaybeableto usealternativelearningorgeneralizationstrategiestoachieve task-dependentbehavior(e.g., Wiltgenetal.,2010),evenin theabsenceofthehippocampus(fordiscussion,see Maren etal.,2013).So,whatistheevidenceforlearning-specificand hippocampus-dependentreinstatementofneuralactivity?To thisend,onestudyhasshownthatphotoinhibitionoflearningtaggedCA1pyramidalcellsresultedinthereductionoffear behaviorinashock-associatedcontextandthatthiscoincided withreducedreinstatementofc-Fosexpression,specificallyin otherc-Fos-taggedand,presumably,engram-bearingcortical andsubcorticalcellsofthebrain(Tanakaetal.,2014).Inaseparatestudy(Guoetal.,2018),itwasfoundthatcontextualfear

Perspective Figure2.KeyFeaturesofHippocampal MemoryIndexingTheory

learningincreasedmossyfibersynaptic contactsoftaggedengram-bearingdentategranulecells(DGCs)withparvalbumin-positive(PV+)stratumluciduminhibitoryneurons(SLINs)toasignificantly greaterextentthanarandompopulation ofDGCs.Thisengram-dependent recruitmentofPV+ SLINsreturnedto pre-learninglevelswithtime-dependent memorygeneralization.Bygenetically enhancingthecouplingofengrambearingDGCswithPV+ SLINs,theauthorsincreasedfeed-forwardinhibition inDG-CA3circuitryandstabilizedthe hippocampalengram.Critically,thiswas showntoconferoptogeneticbehavioral reinstatementandcontext-specificreactivationofadistributedfearmemorytrace inhippocampal-cortical-subcorticalnetworksatremotetimepoints.Collectively, thesefindingsmirrornaturalrecall,insofarascontextualfearmemoryretrieval intheoriginallearningcontextisassociatedwiththespecificreactivationof learning-dependenttagginginthehippocampusandsomeextrahippocampaltargets.However,formaldemonstrationfor howhippocampusmayinfactcoordinate extrahippocampalreinstatementinan experience-dependentmannerisabsent.

Inlightofunderstandinghippocampal engramfunctionsthroughthelensofindexing,itisimportanttoemphasizethatalthoughbehavioral reinstatementdoesnotequatetoneuralreinstatement,the behavioraloutcomesofoptogeneticmanipulationsofhippocampalengramsappearexperiencedependent.Forexample, asnotedabove,stimulationofcontextualfear-conditioningtaggedcellsintheDGresultsinincreasedfreezinginasafe (noshock)context(e.g., Liuetal.,2012).However,ifsuchstimulationoftheDGoccursforneuronsthatweretaggedfollowing theextinctionoffearinashock-associatedcontext,thenthis manipulationresultsinreducedfreezinginashock-associated contextanddecreasedspontaneousrecoveryofcontextual fear(Lacagninaetal.,2019).Likewise,inhibitionofcontextfear-taggedDGcellsattenuatesfreezinginashock-associated context(Tanakaetal.,2014),butinhibitionofextinction-tagged DGcellscanincreasedefensiverespondinginapreviouslyextinguishedcontext(Lacagninaetal.,2019).Theseexperience-specificfindingsarecomplementedbyotherstudieswherethe behavioralresponse(beyonddefensivebehavior)ofDGengram reactivationreflectsthevalenceofthereinforcingstimuliassociatedthecontextorengram(e.g., Ramirezetal.,2015; Redondo etal.,2014).Also,considerthatsimplyreactivatingengramcells

thatweretaggedduringhomecageexplorationorexposuretoa contextinwhichshockneveroccurreddoesnotappearto induceabnormallocomotionorovertdefensivebehaviors(e.g., Ghandouretal.,2019).

Whileindexingmayexplainthecapacityforphotoactivationof taggedhippocampalengramcellstotriggermemory-specific behaviorindifferentcontexts,reinstatementofbehaviorisoften notablylessthanwhatwouldbeexpectedthroughnaturalrecall (i.e.,returningtheanimaltotheoriginaltrainingcontext).Inthe frameworkofindexing,weproposetherearenumberofreasons whythismaybethecasebeyondthefactthatnaturalrecallis presumablymosteffectiveinreactivatingtheindex.Importantly, theabovementionedtaggingsystems,whileexperimentallytime locked,arestillthoughttoopenawindowoftaggingthatmaybe ontheorderofatleastseveralhours.Thus,whenartificiallyreactivatingthesecells,itispossiblethattheexperimentermayalso betriggeringactivationofothernonspecificindicesand/or experiencessuchasactivityinthehomecageandpre-or post-traininghandling.Thesepatternsarenotspecifictotheprimarylearningepisodeinquestionandthusmaycompetefor behavioralexpression.Contextualstimulipresentinthetest contextmayalsotriggerinterferenceaswell,actingasexternal inhibitors.Thereby,anumberofcontrols(e.g.,nonreinforced, homecage)forbetterisolatingandassessingthedegreeof experienced-dependentbehavioralreinstatementshouldbe performed.Additionally,hippocampalindicesnotonlyareproposedtoencodetherelevantbrainsystemsactivatedduring anexperiencebutalsomayrepresentthesequentialpatterns ofsuchactivation(BuzsakiandTingley,2018).Currentmethods ofoptogeneticreactivationofhippocampalengramcellslack suchsequence-basedreactivation(Carrillo-Reidetal.,2019), beyondwhatisinherentlystructuredinthelinkageofhippocampalengram-bearingcircuits.Furthertechnologicaladvancements,whichmaybetterconstrainthewindowoftaggingtoa particularexperienceormaybeabletoreactivatecellsin sequence-dependentmanners,arecrucialtoimprovethereadoutsandinterpretationofthisreinstatement.

Isthehippocampusaloneinitspotentialcapacityforindexing?Associationcorticessuchasthesensoryassociationcortex andECmayalsoexhibitindexingpropertiesduetotheirconvergenceofsensoryinput,therebycontributingtoahierarchicalindexingscheme(McClellandetal.,1995).Thus,thehippocampus mayservetosomeextentasanindexofindicesintheECand otherinputstructuresasinformationisroutedinandthenback outagain.Assumingsuchhippocampalsignalscanbedecompressedtoreinstateactivityincorticalandsubcorticalnuclei (asnotedabove),anexactone-to-onerepresentationinthehippocampusofcorticalmodules(forexample)seemsunlikelyand maynotbenecessary.Infact,convergenceofneuralactivityinto thehippocampusmightbeessentialforitsabilitiestoform conjunctivecontextualrepresentations(RudyandO’Reilly, 1999).Othercriticaltargetsofthehippocampus,suchastheretrosplenialcortex(RSC)(Cowansageetal.,2014; Maoetal., 2018)orlateralseptum(LS)(Benderetal.,2015; Besnard etal.,2019; TingleyandBuzsa ´ ki,2018),mayalsomaintain suchconvergenceofprocessingandmaytherebybepartofa hierarchicalindexingscheme,assumingthesestructuresare capableofreinstatingpatternsofexperience-specificassembly

patterns.Indeed,onestudyfoundthatreactivationofcellsofthe RSCthatweretaggedatconditioningissufficienttoinduce behavioralexpressionoffear,evenintheabsenceofafullyfunctionalhippocampus(Cowansageetal.,2014).Importantly,this studyshowedthatoptogeneticactivationoftheRSCengram, likenaturalrecall,recruitedoverlappingdownstreamcircuitsin theamygdalaandEC,demonstrativeofreinstatementofexperientialactivity.Thus,indexingmaynotnecessarilybeuniqueto thehippocampus;however,thehippocampusmaybeuniquely positionedtoindexepisodicevents,giventhesignificantly greaterextenttowhichitintegratescomplexandhierarchical sensoryinformationfromacrossthebrain(seesectionsbelow), aswellasduetoitsdiscriminativecodingandcircuitarchitecture.Unpublishedfindingsindicatingthatreactivationof engram-taggedneuralstructures,outsidethehippocampus, doesnotequallyreinstatebehaviormaysupporttheparticular importanceofhippocampalindexing(Royetal.,2019).

MemoryIndexinginHumans?

Electrophysiologicalstudiesinhumanshavesuggestedthatthe humanhippocampusalsopossessespropertiesconsistentwith indexing.Forexample,inepilepticpatientswithdepthelectrodesimplantedintothemedialtemporallobe,freerecallof anaudiovisualexperiencewasshowntofollowtheselectivereactivationofhippocampalandECcellsthatwereactiveduring thepriorexperience(Gelbard-Sagivetal.,2008).Likewise, successfulretrievalinanobjectassociationtaskcoincided withreinstatementofspikingactivityinhippocampalandEC cells,hippocampalactivityprecedingECfiring,anddecoding analysesofECactivitypredictingtheidentityoftherecalledobject(Staresinaetal.,2019).Otherintracranialrecordingshave shownthatbehavioralrecallwaslinkedtocoordinatedhippocampal-lateraltemporalcorticalrepresentationalreinstatement ofitem-contextassociations(PachecoEstefanetal.,2019).In thisstudy,hippocampalreinstatementprecededthatseenin theneocortex,andhippocampal-corticalgammaphasesynchronyduringhippocampalreinstatementpredictedneocortical reinstatement.Moreover,thesefindingsaremirroredinadditionalstudiesthathavefoundmemory-relatedreinstatementin thehumanhippocampusisunderscoredbyasparseanddistributedsetofactivecells(Wixtedetal.,2014, 2018).

Humanfunctionalmagneticresonanceimaging(fMRI)studies supportasimilarinterpretation.Forexample,onefMRIstudy (Harandetal.,2012)reportedthathippocampalBOLD(bloodoxygen-level-dependent)activityduringanepisodiclearning experiencematcheditsactivityatrecall(i.e.,recognitionofpreviouslyshownvisualcues),particularlywhensubjectsreported therememberingofepisodicdetailsofthelearningevent.Interestingly,thisepisodicreinstatementofhippocampalactivity occurredforrememberedcuesat3daysandeven3months followinglearning.Moreover,forsuccessfulretrievalofexperientialmemory(intaskssuchasobjectrecallandrecognition), regionsincludingtheRSC,parahippocampalcortex(PHC),perirhinalcortex(PRC),andprefrontalcortex(PFC)haveallbeen showntoexhibitrecall-dependentreinstatementalongwithor inclosetemporalproximitytohippocampalreinstatement,suggestiveofhippocampal-dependentrouting(e.g., Arnoldetal., 2018; Jonkeretal.,2018; Schultzetal.,2019).Again,whilereinstatementandtemporalpatternsofactivationalonedonot

Figure3.Hippocampal(DG-CA3-CA2-CA1)CircuitArchitectureand AnatomicalLoopsPermitFlexibleIntegrationandRoutingof ExperientialInformation

(A)Examplesofhippocampalinputs(bluearrows). (B)Examplesofhippocampaloutputs(orangearrows).Notethattheprojectionsshownarenotexhaustive.

Brainregionsincludetheanteriorcingulatecortex(ACC),bednucleusofthe striaterminalis(BNST),basolateral/basomedialamygdala(BLA/BMA),central amygdala(CEA),dentategyrus(DG),dorsalraphenucleus(DRN),entorhinal cortex(EC),cornuammonisregions(CA1–CA3),infralimbiccortex(IL),locus coeruleus(LC),anterior/lateralhypothalamicarea(A/LHA),lateralseptum(LS), medialseptum(MS),nucleusaccumbens(NAC),orbitalfrontalcortex(OFC), prelimbiccortex(PL),nucleusreuniens(RE),retrosplenialcortex(RSC),subiculum(SUB),supramammillarynucleus(SUM),andventraltegmentalarea (VTA).BrainregionimagesweregeneratedusingBrainExplorer2.0(Lein etal.,2007).

demonstrateindexing,thesefindingsareconsistentwithdata fromrodentsandleaveopenthepossibilitythatfutureexperimentsmaydirectlytestthisideainhumans.

AnIntegratedCircuitModeloftheHippocampalIndex Inthedecadessincetheintroductionofthehippocampalmemoryindexingtheory,considerableadvanceshavebeenmadein ourunderstandingofthecomplexityanddiversityofhippocampalcircuits.Ifexperience-taggedhippocampalengramsserve asepisodicindices,howmightthecircuitarchitectureofthe brainbeemployedforencodingandrecall?Totheseends, theconjunctive,sparse,andcompressedcodegeneratedin theDGviapatternseparationwouldsupportindexingbyminimizingmemoryinterference(Figure2,featurei)(Cayco-Gajic andSilver,2019; HainmuellerandBartos,2020; Knierimand Neunuebel,2016; McHughetal.,2007),whileDGoutputs, togetherwithdirectECinputs(alongsidethediverseafferents describedbelow),ontoCA3cellswouldbiasattractordynamics intherecurrentnetworktostoreanexperienceasanewmemory,orcatalyzetheretrievalorupdatingofapreviouslyencoded memorybypatterncompletion(Figure2,featuresii–iv).Accordingly,theexperienceisregisteredinasparsehippocampalcode orengramcomposedofprincipalcells(andinhibitoryneurons [INs])acrossthedifferentsubregions(DG,CA3,CA2,and CA1),withtheircoordinatedactivitypermittingintra-andextrahippocampalreinstatementoftheoriginalexperiencethrough dynamicrouting(Figure2,featuresv–vii; Figures3 and 4).We elaborateonthisideawithrecentexamplesinthenextsections. DynamicRouting:HippocampalAfferents

Inthisframework,theDG-CA3-CA2-CA1circuitcanbeperceived asatemplateofnodes,witheachnodereceivingdiverseintra-and extrahippocampalinputsallowingfortheintegrative,dynamic, andflexibleincorporationofcognitiveandvisceralinformation intomemoryrepresentations(Figure3A).Thesepropertieswould enablethehippocampustoparticipateinmany‘‘types’’ofmemories—spatial,goal-oriented,social,future-planning—allwhich maycomprisediverseepisodicexperiences.Forexample,direct long-rangeGABAergicprojectionsfromthelateralhypothalamus (LH)toCA3havebeenrecentlyidentified(Zhouetal.,2019a); theseneuronssynapseontoCA3interneuronsandappearto havecriticalfunctionsintasksofobjectrecognitionanddiscrimination,revealingadirectpathwaybywhichCA3mayintegrate endocrinesignalsinlearningandmemoryprocesses.CA3neuronsalsoincorporatelocuscoeruleus(LC)input,andonestudy foundthatLCprojectionstodorsalCA3(dCA3;butnottoCA1 orDG)arerequiredforencoding(butnotretrieval,whichmaybe mediatedbyCA3-CA1[seebelow])ofacontextualrepresentation (asassessedbydistancetraveledinapreviouslyexploredcontext orviasingle-trialcontextualfearconditioning)(Wagatsumaetal., 2018).Additionally,parallelcircuitsprojectingfromneuronsin thesupramammillarynucleus(SUM)totheDGandCA2have beenfoundtocarrycontextualandsocialnoveltysignals,respectively,allowinghypothalamicsculptingofhippocampalmemoryin atask-specificmanner(Chenetal.,2020;seealso Lietal.,2020; Hashimotodanietal.,2018).Theserecentdiscoveriesbroadenour understandingofthediversityofmammalianhippocampalafferentsandpointtomultiplesourcesviawhichthehippocampus mayintegratesignalsformemoryformationorrecall.Activityof thesedistinctsetsofinputs(alongsideotherimportantinputs, includingfromtheamygdalaandanteriorcingulatecortex),recruitedbasedonongoingexperience,maygovernwhichhippocampalroutesaredeployedforencodingand/orrecall.

Perspective DynamicRouting:HippocampalEfferents

Furtherarguingagainstasimplesequentialprocessingloop,itis clearthateachnodewithintheDG-CA3-CA2-CA1circuitprojectstodistinctoutputs(Figure3B).Intheframeworkofindex theory,theseoutputsmaybeflexiblydeployedbyengramcells toreinstateanexperience(whetherthatexperienceisappetitive, aversive,etc.).Anexampleofthispotentialselectiveroutingcan befoundinventralCA1(vCA1)neurons(Ciocchietal.,2015).In thisstudy,vCA1cellsweretrackedbasedontheirprojectionsto thePFC,nucleusaccumbens(NAc),andamygdaladuring behavior,revealingthatactivityintheseneuronsweretaskand pathwaydependent.ThesefindingscriticallysuggestthatsignalsoutofCA1arenotuniformlytransmittedtoitstargets; rather,itsupportstheideaofthatefferenthippocampalsignals areroutedbasedontaskandmnemonicdemands.Withparticularrelevancetoindexing,dorsalCA1(dCA1)tetroderecordings pairedwithcircuit-specificoptogeneticshaveshownthat expressionofconditionedplacepreference(CPP)dependson thereinstatementofdCA1representationsthatwereactiveduringtraining(Troucheetal.,2019).Furthermore,CPPexpression islostifdCA1terminalsinNAcarephotoinhibited,despitedCA1 pyramidalcellsmaintainingtheircontext-dependentcellassembliesduringtesting(seealso Zhouetal.,2019b).

ThisroutingabilityisnotrestrictedtoCA1;CA3outputneuronsmayrouteinformationviaprojectionstoCA1,CA2,orthe DLS(dorsolateralseptum).Indeed,brain-wideanalysesofcoactivatedcircuitsaccompanyingcontextualfeardiscrimination identifiedaCA3-DLSmodule(Besnardetal.,2019).This pathwayappearstorecruitsomatostatin(SST)+ DLScellsto gateconditionedfreezing,as invivo calciumimagingfound SST+ DLScellactivityreliablydiscriminatedshock-associated versussafecontexts.Insupportofthesefindings,optogenetic-terminal-specificsilencingofdCA3terminalsindCA1 andDLShassuggesteddistinctrolesfordCA3-CA1and dCA3-DLSprojectionstocontextualfearlearning(orconsolidation)anddiscrimination,respectively(Besnardetal.,2020).

ForCA2,itsefferentnetworkpositionsitstronglyformemories involvingsocialrecognition,discrimination,andaggression(MiddletonandMcHugh,2019).Indeed,CA2(andCA3)efferentsdo notuniformlyregulatediscrimination(Raametal.,2017).OptogeneticexperimentshavedemonstratedthatanteriorCA2/dCA2 neuronstargetingdCA1areessentialfornovelobjectrecognition, butnotfordiscriminationbetweennovelandfamiliarconspecifics. TheoppositewastruefordCA2/dCA3projectionstoposterior CA1.PhotoinhibitionofdCA2/dCA3projectionstotheDLSwere insteadshowntosomewhatenhancesocialdiscrimination,but withnoeffectonobjectdiscriminationorrecognition.Insocialbehaviors,axonsfromdCA2neuronstargetingventralhippocampus wereshowntobecriticallyinvolvedinmaintainingmemoryofa familiaranimal(Meiraetal.,2018; Raametal.,2017),whilepharmacogeneticinhibitionofCA2terminalsintheDLSattenuatessocialaggression(Leroyetal.,2018),apathwaythat,whenactive, appearedtoinvokeDLS-innervationoftheventromedialhypothalamustodriveattackbehavior.

Intotal,multiplenonoverlappingengramswithinthesediverse hippocampalroutesmaycompetethroughupdatingorongoing learningtomodifybehavioraloutput.Forexample,two-photon (2P)imagingofDGandCA3engrams invivo revealedthatthe

updatingofarewardlocationpromotedactivityremappingin CA1andCA3,butnotintheDG(HainmuellerandBartos, 2018).Recentworkhasalsodemonstratedthatcontextualfear extinctionrecruitsadistinctDGengramfromthatencodingthe originalcontext-shockassociation,whichreduceslevelsof freezinginthetrainingcontextbutcanbeovercomebytheoriginalengramtoinducerelapse(Lacagninaetal.,2019).Likewise, prolongedoptogeneticorchemogeneticreactivationofaDG fearmemoryengraminthetrainingcontextwithouttheunconditionedstimuluspromotedextinctionoftheconditionedresponse (Khalafetal.,2018).Ofcourse,thehippocampusisnotuniquein thistypeofbroadconnectedness;otherhubsinthebrain, includingtheclaustrum(Jacksonetal.,2020)andthethalamus (HalassaandSherman,2019),maysurpassitintermsoftotal connectivity.However,thesedatasuggestthatthehippocampusiscapableofintegratingandroutingcomplexinformation fromavarietyofsourcestructures,supportingitsroleinthebindingofcognitionandemotiontosubservememory(Figure4A).

DynamicRouting:InhibitoryMicrocircuits

Howmightthesediversecommunicationchannelsrunning throughthehippocampusbemanaged?HippocampalINsare wellpositionedtofunctionasarbitersofinformationflowinthe hippocampus,astheytargetdifferentcellularcompartmentsof principalneurons,arereciprocallyconnectedwithotherinterneurons,andprojectlocallywithinandacrossdifferentsubregions andlamellaeandoutofthehippocampustoassociationcortices andsubcorticalcircuits(long-rangeINs)(Caroni,2015).Moreover, hippocampalINsmodulateneuronalexcitability,summationof excitatoryinputs,andneuronalfiringinadditiontogenerationof networkoscillations(thetaandgammaoscillations)andassuch arethoughttoplaycriticalrolesinlocalcircuitcomputationsunderlyingexplorationandencoding,actionselection,memory consolidation,retrieval,andreinstatement(Cardin,2018; Makino etal.,2019; RouxandBuzsaki,2015; Sosaetal.,2018).Indeed, recentstudieshaveuncoveredadiversepopulationofINsin CA1andCA3thatexertperisomaticanddendriticinhibitionon DGCsandaremodulatedbySWRs.

LocalINsmayregulateinformationflowwithinahippocampal subregionbybiasingrecruitmentofprincipalcells,thereby creatingparallelchannelsasevidencedinastudythatidentified biasedPV+ basketcell(BC)connectivitywithdeepandsuperficialCA1neuronsoftheventralhippocampus(Leeetal.,2014). TheauthorsfoundthatPV+ BCspreferentiallyinnervateddeep CA1pyramidalneuronsbutreceivedgreaterexcitatoryinputs fromsuperficialCA1pyramidalneurons.Atthelevelofoutput, PV+ BCsexertgreaterinhibitionontobasolateralamygdala (BLA)-projectingdeepCA1neuronsthanthosethatprojected tothePFCand,inturn,receivedgreaterexcitatoryinputfrom PFCthanBLA.ThesedatasuggestthatPV+ BCsdonotuniformlyinhibitCA1;instead,itislikelythatPV+ BC-principalcell microcircuitsbiasinformationflowtodistinctvCA1outputs, includingPFC,BLA,NAc,DLS,andLH(servingdynamicand flexiblerouting).LocalINsmayalsodifferentiallyregulatetheta phase-lockingandburstfiringofCA1neuronsthroughsomatic ordendriticinhibition,respectively(Royeretal.,2012).Because burstfiringofpyramidalcellsisthoughttoincreasesynaptic communicationbyincreasingexcitationofdownstreamtargets, localINsmaymodulateCA1outputsthroughthismechanism ll

AB

(Gravesetal.,2012; Lisman,1997; TakahashiandMagee,2009). Importantly,rhythmicoptogeneticactivationofPV+ INsinCA1to mimicthatseenduringlearningenhancedtheta,delta,andripple oscillations;stabilizedfunctionalconnectivitybetweenCA1neurons;andreliablypromotedensemblereactivation(Ognjanovski etal.,2014).Theexactroletheseoscillationsplayintheabilityof anindextoreactivatedownstreamtargetsremainslargelyuntested;however,evidencesuggeststhecoherenceorcoordinationofactivitytheyprovidemayfacilitateboththeencodingand recallofmemoriesacrossvariousstructuresbyensuringtemporalcoordinationofactivity(Buzsaki,2015; Corcoranetal.,2016; Igarashietal.,2014; JooandFrank,2018; Linetal.,2017; Makinoetal.,2019; WirtandHyman,2019).

Pioneering invivo recordingsandimagingstudiesinratsidentifiedextensivelyconnectedINswithextrahippocampal(septum, subiculum,para-andpre-subiculum,andRSC)projectionsthat coordinatenetworkoscillations(Bonifazietal.,2009; Jinno, 2009).Long-rangeinhibitoryprojectionneuronsoftheLECsup-

Figure4.HippocampalEngramsMayIndex ExperiencetoReinstateExperiential Memory

(A)Distinctexperiencesarethoughttobeencoded withinDG-CA3-CA2-CA1connections,with engram-bearingcellsbeingfunctionallylinkedto otherneuronsforthesameepisode.Recallcan thenbedrivenbypartialinput(cues)thatreinstate activity(filled-incircles/squares)withinhippocampalcircuitstodriveextrahippocampalreinstatementviaitsdiverseoutputsandconnectivity tootherengram-bearingcells.PCs,principalcells; INs,inhibitoryneurons.

(B)Hippocampalcellsmayregistermorethanone experienceindistinctpatternsofconnectivity prescribedbyactivity-dependentgeneexpression(shownhereascombinationsof1sand0s).

pressCA1cholecystokinin-positive (CCK+)interneuronsthatrelayfeed-forwardinhibitionfromCA3toCA1 exvivo (Basuetal.,2016).Thisdisinhibitionof CA1interneuronsinducedenhanceddendriticspikingwithinaspecifictemporal window,amechanismbywhichsensory informationandmnemonicinformation arrivingfromexcitatoryLECinputsand CA3,respectively,maybeintegrated. Morerecently,aclassoflong-rangeinhibitoryneuronalnitricoxidesynthase (nNOS)-expressingcellsinCA1(LINCneurons)hasbeenidentifiedthatprojectboth locallyandextra-hippocampally(ChristensonWicketal.,2019).Theseneurons inhibitsuperficialanddeepprincipalcells andotherINsinCA1andproject todiverseextrahippocampaltargets, includingtheteniatecta,subiculum,hypothalamus,olfactorybulb,andEC.OptogeneticactivationofLINCneuronsentrained hippocampaloscillationsandhippocampal-frontalcortex(teniatecta)coherence. Thus,convergingevidencehasbeguntoilluminatehowcellphysiology,activity-dependentgeneexpression,andmicrocircuitconnectivitysupporthippocampalengram-cell-dependentindexing (i.e.,encodingofexperiencesandroutingofinformationtomediate reinstatement).Wediscussthesefeaturesofengramcellidentitynext.

IndexCellIdentity Giventhelong-standingfocusonrodenthippocampalplace cells,anobviousquestioniswhataspectofcontextualmemory isencodedwithinthehippocampalengram.Behavioralstudies usingvariationsofcontextualfearconditioningsuggestthat thehippocampusgeneratesaconjunctiverepresentationof multimodalsensoryinformationformedthroughphysicalexplorationofacontext(Fanselow,2000;seealso Krasneetal.,2015). Forexample,onestudypreexposedratstoeithertheconditioningcontextorindependentfeaturesofthatcontextandfound contextfearafteranimmediateshockisfacilitatedonlywhen

Perspective thesemultimodalcuesarepresentedtogether,suggestingthat thehippocampusrepresentstheconjunctionofthecues definingthecontext(RudyandO’Reilly,1999).Indeed,temporarypharmacologicalinactivationofthehippocampusduring thecontextpreexposurepreventsthecontextualfearconditioningofimmediateshock(Matus-Amatetal.,2004).Paststudiesof IEGexpressioninthehippocampussupportthisthisview(e.g., Huffetal.,2006; Zhuetal.,1997);thestrongestIEGresponse isachievedwhenanovelcombinationofmultimodalcuesispresentedtotheanimal.Conversely,hippocampalIEGexpression isweakornonexistentwhenahighlyhabituatedstimulusis given.Notethatimmediateshockuponcontextentryinthe absenceofpreexposure(andextensivepostexposure)does notappeartoelevatelevelsofIEGsinthehippocampusrelative toahabituatedhomecage(seealso Erwinetal.,2020).These datasuggestthatIEG-expressingengramneuronsmaynot necessarilyorexclusivelystorespatialinformation,asrodents willhaveactiveplacecellseveninthemostfamiliarofcontexts, butratherhippocampalcircuitsdetectnoveltyinthecombinationofsensorycuesandencodeitasacontextualrepresentation supportingtheepisodicexperience.Indeed,optogeneticstimulationofCA1neuronstaggedinanovelcontextthedaypriorto immediateshockdeliveryinthesamecontext,butnotadifferent context,resultedinretrievalofthecontextualfearmemory (Ghandouretal.,2019;seealso Ramirezetal.,2013).Thus,a memoryengram,definedbyactiveprincipalcellsduringcontextuallearning,maypreferentiallyencodeconjunctivecontextual information,asopposedtospecificlocationsthatcouldbe biasedbyaspecificcueorsubsetofcues.

Physiology

Keyinsightsintothepreciseidentityofengram-bearingcells camefrom invivo recordingofCA1neuronsinamouseinwhich c-Fos-positiveneuronslabeledduringanovelcontextexposure weretaggedwithchannelrhodopsin2(ChR2)andsubsequently opticallyidentified(Tanakaetal.,2018).Asexpected, 50%of allCA1pyramidalcellscouldbeclassifiedasplacecells;however, onlyone-quarteroftheseplacecellsalsoexpressedc-Fos(optogeneticallyidentified).Inshort,engramcellswereplacecells,but onlyone-quarterofplacecellswereengramcells.Duringmemory encoding,theseengram-bearing(c-Fos)cellsaredistinguishedby highermeanfiringrates(asalsoseeninacalciumimagingstudy; Ghandouretal.,2019),repetitiveburstsofactionpotentialsatthe thetafrequency,andhigherentrainmentbythelocalfastgamma oscillationcomparedtothenon-c-Fos-expressingplacecells, againhighlightingtheroleinhibitorycircuitsandoscillationsmay playintheformationoftheindex.Interestingly,whenmicewere returnedtothecontextthenextday,c-Fos-positiveengramneurons,whileremainingplacecells(meaningtheystilldemonstrated areliablein-sessionspatiallyreceptivefield),showedamuch higherdegreeofspatialinstabilitycomparedtotheencodingsession(remapping)thanthec-Fos-negativeplacecellpopulation. Thesedatacanbeseenasparadoxical;howisitthattheneurons showntobecapableofreinstatingcontext-appropriatebehavior showrelativelylowerspatialspecificitythantheremainingactive cells?Importantly,whenonlyfiringrate(andnotlocation)was considered,itwasclearthattheengramcellsfaithfullyencoded contextualidentity,butnotspecificlocation.Areturntotheencodingcontextresultedinc-Fos-positiveneuronsreinstatingtheir

averagefiringrates,whichwerehighlycorrelatedbetweenthefirst andsecondvisits,whilethefiringratesinadistinctcontextwere stronglyaltered.Itworthnotingthatthisstrongcorrelationofactivityemergesassoonasanimalisplacedintheenvironment, suggestingtheiractivitycouldsupportrapidretrievalofcontextual memory,consistentwiththeindexingtheory.Further,thesefindingsofauniquephysiologysuggesttheimportanceofthetemporalrelationshipbetweeninputfromCA3andtheECintriggering CA1pyramidalcellplasticityandactivity invivo (Bittneretal., 2017; Ketzetal.,2013).

Complementaryresultswerealsofoundinaphysiologicalstudy inwhichc-Fos-positiveCA1neuronswereinhibitedduringrecall (Troucheetal.,2016).Inthisstudy,engramneurons,definedby c-Fosexpressionassociatedwiththeacquisitionofacocaine-rewardedCPP,werelabeledwithaninhibitoryopsin.Inactivationof thisensembleduringasubsequentrecallsessionreducedCPP behaviorand,interestingly,ledtoaglobalremappingofthe c-Fos-negativeactiveplacecellpopulation.Together,these datasuggestthattheroleofthec-Fos-positiveplacecellsisto serveasacontext-specificmemoryindexandthattheiractivity iscrucialforthestablereinstatementofamoredetailedspatial map,consistingoftheremainderoftheplacecellpopulation, thatwouldpermitanimalsprecisenavigation.

Whileitmayseemoddatfirstthattheneuronsindispensable forinducingmemoryrecallinCA1showspatialinstability,recent computationalmodelinglendssupporttothisview(Bennaand Fusi,2019).Basedonanassumptionthatthehippocampusencodescorrelationsofincomingsensoryinformation,similarto theinterpretationfromcontextualconditioningandIEGstudies, themodelpredictedinstabilityinthespatialrepresentationof thehippocampus.Theirultrametrictree-likenetworkgenerated sparseandcompressedrepresentationsofinputstoefficiently storeuncorrelatedpatternsinahippocampal-likenetwork. Whenspatialnavigationina2Dopenfieldissimulated,activities ofhippocampalcellsinthemodelexhibitstrongmodulationby theanimal’slocationwithintheenvironment(i.e.,placecells). However,similartotheexperimentalobservationsabove,these placefieldssignificantlyremappedbetweenepochsinthe sameenvironment,suggestinginstabilityoffiringlocationasa reflectionofcorrelationcodingratherthanspatialcoding.Taken together,thesestudiessupportaviewthatactivityofthehippocampalengramreflectsmorethanjustspaceandsuggestatleast asubsetofneuronsarededicatedtocapturingtheconjunctive correlationsthatdefinethelargercontextoftheexperience. Activity-DependentRegulationofGeneExpressionand Connectivity

Hippocampalengramsaregeneratedandmaintainedby strengtheningormodificationofsynapsesamongactivatedcells withinandacrosssubregions.Onestudyfoundthatc-Fos-tagged CA3cellspreferentiallyrespondedtostimulationofengramtaggedDGCs(Ryanetal.,2015),resultsindicativeofexperience-drivenconnectivityofDG-CA3.Likewise,context-feardependentincreasesinthenumberandsizeofspinesin engram-bearingcellsofCA1coincidewithdirectinputfrom engram-taggedcellsfromCA3(Choietal.,2018).Additionally, DGengramcellswereshowntoexhibitgreaterconnectivity withstratumlucidumPV+ INsthannon-engramDGcells(Guo etal.,2018).Theseobservationshavemotivatedinvestigations

intohowdevelopmentalprogramsandactivity-dependentgene expressionprescribeengramformation.First,principalneurons mayhavedifferingpropensitiestowardrecruitmentintoengrams basedondevelopmentallyprogrammedintrinsicfiringproperties andconnectivity(CembrowskiandSpruston,2019; Solteszand Losonczy,2018).Second,activity-dependenttranscriptionfactorsandcombinationsthereofenableneuronstoread patternsofneuralactivityandtranscribemolecularspecifiersof connectivitytofacilitatestrengtheningormodificationofsynapses(Tyssowskietal.,2018).Forexample,cyclicadenosinemonophosphate(cAMP)-response-element-bindingprotein(CREB)overexpressionstudieshaverevealedthatenhancingbasal activityandexcitabilityofprincipalcellsinthehippocampus(or subsetsofamygdalarneurons,etc.)priortolearningcanbias theallocationandtaggingprocesstothesecellswithoutaltering theoverallsizeoftheengramperse(JosselynandFrankland, 2018; JosselynandTonegawa,2020).Arecentreportusing RNAsequencingofengram-taggedDGcells(followingcontextual fearconditioning)identifiedauniquelearning-dependentgenetic profileforengram-bearingcells,withCREB-dependenttranscriptionnetworksbeingdifferentiallyregulatedandrequiredfor consolidation(Rao-Ruizetal.,2019).Interestingly,manyofthese geneswerepreviouslyshowntoregulatesomaticinhibition(e.g., neuronalPASdomainprotein4[NPAS4],proenkephalin[Penk], andbrain-derivedneurotrophicfactor[BDNF])(Bloodgood etal.,2013).Consistentwiththesefindings,withintheDG, contextualfearlearningregulatesCREB-dependentlevelsofneuropeptideY(NPY)inSST+ hilarperforantpath-associated(HIPP) interneurons,whichmayregulateSST+ HIPP-mediatedfeedback andfeed-forwardinhibitionintheDGtogovernthesizeofthe engram(Razaetal.,2017; Stefanellietal.,2016).Notsurprisingly, differentIEGtranscriptionfactors(includingNPAS4)havebeen functionallyimplicatedinlinkingprincipalcellswithdistinctINnetworkstosupportengramformation(Sunetal.,2020).Thus,experientialinputmaydriveuniqueIEGexpressiontogovernfunctional allocationofengram-bearingcellstoworkinconcertformemory expression(Figure4B).

HippocampalIndexStabilityandMemoryFidelity Memoryconsolidationisthoughttoinvolvetransformationand reorganizationofhippocampal-linkedcognatecorticalrepresentationsandagradualdecayofthehippocampalengramover time(DeNardoetal.,2019; Guskjolenetal.,2018; Kitamura etal.,2017; Royetal.,2017; Tayleretal.,2013; Winocuretal., 2007).Consolidatedmemorieshavebeenshowntogeneralize orlackdetail,includingtheextenttowhichtheymayelicit visceralorphysiologicalreactions,leadingtothesuggestion thattherolethehippocampusplaysinmemoryistocontribute episodicdetail(Yonelinasetal.,2019).Ifthiscontributionrelies ontheinitialmemorytraceornotremainsacontestedtopic. Forexample,ithasbeenarguedthathippocampalmemory tracesremain,evenforoldermemories(MoscovitchandNadel, 2019),butothershavearguedthereisashiftintherolethehippocampusfromoneofrecalltoreconstructionintheabsenceof theoriginaltrace,withtheactivityservingtoindexconsolidated neocorticaltraces(BarryandMaguire,2019a, 2019b).These observationsraisethefollowingquestions:Isthehippocampal indexalwaysnecessaryformemoryretrieval,ordocorticalin-

dexesacquirethisfunctionovertime?Isthecorticalindexequivalenttothehippocampalindex?

Severallinesofevidencesupportthenotionthatthehippocampalindexmaybenecessaryformaintenanceandretrieval ofonlyhighlyprecisememories.First,althoughhippocampal damageatremotetimepointsmaystillpermitretrievalof detailedcontextualrepresentations,theextentofmemory retrievalisoftenmuchlessrobust(Wangetal.,2009),suggesting thatextrahippocampalindicesmaynotfullycompensateforthe lossofthehippocampalindex.Indeed,whileasimilardegreeof hippocampalactivationisseenforrecentandremotememories, thereactivationpatternsaredifferent(Tayleretal.,2013;seealso Guskjolenetal.,2018).Second,artificiallystabilizingtheengram withinDG-CA3decreasesremotememorygeneralization(and maintainsbehavioralreinstatementofremoteDGengramstimulation; Guoetal.,2018),providingadirectlinkbetweenmaintenanceofthehippocampalindexandremotememoryprecision. However,maintenanceofseparatehippocampalindicesforall episodicmemoriesisthoughttorequiresignificantlygreatercapacitythanisavailabletoavoidmemoryinterference(McClellandetal.,1995; MillerandSahay,2019; SkaggsandMcNaughton,1992).InCA1,thevariousmethodsemployedtogenetically labelengramneuronstypicallycapture 20%ofthepyramidal cellsintheregion(Tanakaetal.,2018),and invivo imagingsuggestedthattheidentityoftheseallocatedneuronsshiftsoverthe timescaleofhours(Caietal.,2016);thus,itappearsthatnatural decayofhippocampalindicesensuresthetime-dependentreorganizationofmemorytracestosupportdifferentdegreesof generalizationandgenerationofschematofacilitatenew learning.Itmaybethatsomehippocampalindexes,perhaps forsalientlifeevents,aremaintainedforlongerperiodsoftime, therebypermittingrecallofremotememorieswithhighfidelity.

Theintegrityandcompositionofthecorticalindicesdepends onhowcompetitionforrepresentationofepisodicmemoriesand abstractionofstatisticalcommonalitiesacrossensembles dictatethebalancebetweenpreservationofdetailsversusgenerationofschematofacilitatememorygeneralization.Thismay involvetime-dependentchangesintheexactnumberofcells andpatternsofefferentconnectivityofcorticalensemblesand linkageofdistinctengramsofseparateexperiencesviasome degreeofoverlappingandsynchronousactivation(duringrecall orreconsolidation)ofengram-bearingcells(Abdouetal.,2018; DeNardoetal.,2019; Kitamuraetal.,2017; Ohkawaetal., 2015; Oishietal.,2019; Pignatellietal.,2019; Ramirezetal., 2013; Redondoetal.,2014).

Whilenoonemodelcanexplainallthecurrentdata,fromthe perspectiveofengramsandindexing,wefavorthehypothesis ofatime-dependentshiftintheindexingfunctionfromthehippocampustocorticaltracesconcurrentwithasilencingorlossof theoriginalhippocampalindex(Tonegawaetal.,2018).Ultimately,time-dependentshiftsinhippocampus-dependent episodicdetailmaybeusefulinthedevelopmentofexperiential schemasandbroaderknowledge.

HippocampalDysfunction Indexopathies Memorydeficitsandhippocampaldysfunctionaccompany traumaticbraininjury,epilepsy,age-relatedcognitivedecline,

Alzheimer’sdisease(AD),andnumerousotherpsychiatricdisorders,includingposttraumaticstressdisorder(PTSD)andschizophrenia(BesnardandSahay,2016; Habermanetal.,2017; Small etal.,2011).Canthesedisordersofexperientialmemorybeclassifiedas‘‘indexopathies,’’insofarastheyaremarkedbyan inabilitytoaccuratelyorpreciselyencodeoreffectively implementhippocampus-dependentroutingofinformation (i.e.,indexing)?Forexample,recentworkdocumenteddeclining hippocampalandcorticalreinstatementinagingindividuals (Trelleetal.,2020).Disease-oraging-inducedexcitation-inhibitoryimbalanceinhippocampalcircuits,whichmayimpedeindexing,mayunderliemuchofthesememorydysfunctions. Indeed,excitation-inhibitionimbalance(hypo-orhyperactivity) atthelevelofCA1(e.g., Ohetal.,2013)andCA3(e.g., Simkin etal.,2015; Wilsonetal.,2005)andlossoffeed-forwardinhibitioninDG-CA3(e.g., Guoetal.,2018)areassociatedwithmemoryimprecisioninpreclinicalmodelsofagingandmemorydisorders.Humanimagingstudieshavefurtherreportedsimilar activitychanges(e.g.,hyperactivity)ofhippocampalstructures (Habermanetal.,2017),suchasinpresymptomaticfamilialAD (FAD)individuals(Quirozetal.,2010)orpatientswithamnestic mildcognitiveimpairment(Bakkeretal.,2012).

Suchcellular,circuit,andnetwork-levelalterationsmay disruptthebalancebetweenpatternseparationandpattern completion,therebypromotingaberrantindex-dependentreinstatementandrecall.WhatpreviouslymayhavebeensubthresholdtotriggerCA3-dependentmemoryrecallpriortodiseasemay besufficientafterdiseaseonset,therebypromotingexcessive reinstatementandmemoryexpressionincontextsthatmay notbeoptimal.Forexample,aberrantorexcessiveretrievalof pastexperienceshasbeensuggestedtounderliepsychosisin schizophrenia(Tammingaetal.,2010).Additionally,degradation offlexibleroutingtoextrahippocampaltargets,duetoconnectivitylossesindiseaseorinjury,mayalsoimpedetheabilitiesofthe hippocampustoeffectivelyintegratecorticalandsubcorticalinformationforproperencodingandretrieval.Perhapsrelatedto

suchcircuitloss,ADisconsidered,inpart,adiseaseofmemory retrievalfailure(LealandYassa,2018; Royetal.,2016). PromotingIndexing:NewDirectionsinTherapy

Recentadvancesintechnologyandmedicinehaveledtoanumberofnewtherapeuticavenuesformemorydisorders—strategiesthatmaybeeffective,inpart,becausetheypromoteor reestablishhippocampalindexingfunctions.Forexample, growinginteresthascenteredondeep-brainandclosed-loop feedbackneuroprostheticsforsymptommanagementinindividualswhenotherlinesoftreatmenthavefailed(Grosenicketal., 2015; TakeuchiandBerenyi,2020).Perhapsbyrestoring context-dependentrouting(andtherebyindexing),theserealtimeelectrophysiological(oropto-orchemogenetic,potentially) methodscoulddynamicallynormalizeaberrantactivityorrestore cellexcitabilityinperturbedbraincircuits(e.g.,inhippocampalamygdalarorhippocampal-prefrontalloops).Additionally, recentdevelopmentsintargetedgene-editingapproaches (KnottandDoudna,2018)maypermitmolecularreallocationor respecificationofconnectivityaimedatpromotingmemoryprecisionandaccuracy.Indeed,quietingdisease-relatedhyperexcitedCA3pyramidalcellsmayinvolvetargetingfeed-forward inhibitorymechanismsofDG-CA3(Guoetal.,2018; Vianada Silvaetal.,2019)orCA2-CA3connections(Boehringeretal., 2017)orinhibitingaberrantLH-CA3activity(Zhouetal., 2019a),forexample.Otherpharmaco-orgenetherapiesthat promoteneurogenesisinagingordiseasestatesmayalsoexist asbeneficialtherapeuticavenuesformemoryimpairments (MillerandSahay,2019).

Noveltreatmentsformemoryimpairmentsmaynotbelimited toinvasivetechniquesandmayinvolvesupplementingexisting procedurestobesttapintotheindexingpropertiesofthehippocampus.Forexample,althoughtheuseofmnemonicdevicesfor memorytreatmentsisnotnew,recentdevelopmentsintechnology,suchasaugmentedrealityor3Dinteractiveenvironments, mayprovidenovelavenuesforimprovingmemoryrecallwithin andbeyondtheclinic.Indeed,thegrowingubiquityofpersonal

Figure5.OutstandingChallengesforHippocampalIndexingandMemoryResearch

handhelddevicesmaymakemobileremindersormnemonic cues(tofacilitatereinstatementofmemory)fortreatmentsor symptommanagementformemoryimpairmentsmoreaccessibleorspecialized.Whencombinedwithpsychologicaltreatmentsintheclinic,theseandtheabovementionedpossibilities mayyieldnewsuccessesintreatment-resistantmemorydisorders.Movingforward,indexingmaybeausefulframeworkfor improvingclinicaltherapiesformemorydysfunction.

Conclusions:MovingMemoryForward

Perhapsthebrain’smostpowerfulsearchengine,thehippocampus,sitsatthecenteroftheacquisitionandrecallof episodicmemory.Whilethemechanismsofhowthisis achievedhavebeenthefocusofdecadesofresearchacross manyspeciesanddisciplines,itisoftenchallengingtorelate disparatelinesofinquiry.Here,wehavehighlightedhuman andanimalworkbasedonrecentgenetic,physiological, anatomical,andcomputationalapproachesthattogethersupportanexpandedviewofthehippocampalmemoryindexing theory.Inparticular,wearguethat(1)thefunctionalrolesofputativehippocampalengramcellsincludeindexing,whichmay facilitatedetailedrecallofepisodicexperiences;(2)this episodicrecallisfacilitatedbythereinstatementofengram cellactivityandintheirexperience-sculptedconnectivity;(3)indexingmaynotbeuniquetothehippocampus,butthehippocampusmaybeuniquelypositionedtoindexexperientialmemory;and(4)diseaseofthehippocampusmayimpedetruly episodicmemorybydisruptingitscapacityforprecise context-specificreinstatement.Nonetheless,thereremaina numberofoutstandingquestionsforthefieldandforfuture work(Figure5).Futureworkthatintegratestheselevelsofanalyseswillberequiredtounderstandhowthedynamicsofinformationflowinthehippocampalcircuitcontributestotheencodingandrecallprocessesitsupports.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS T.D.G.acknowledgessupportfromHarvardBrainScienceInitiative.K.Z.T.acknowledgessupportfromMEXTGrant-in-AidforYoungScientists (19K16305),Grant-in-AidforJSPSfellows(19J00974),andaNakajimaFoundationresearchgrant.A.S.acknowledgessupportfromNIHBiobehavioral ResearchAwardsforInnovativeNewScientists(BRAINS)1-R01MH104175, NIH-NIA1R01AG048908-01A1,NIH1R01MH111729-01,theJamesandAudreyFosterMGHResearchScholarAward,theEllisonMedicalFoundation NewScholarinAging,theWhitehallFoundation,theInscopixDecodeAward, theNARSADIndependentInvestigatorAward,EllisonFamilyPhilanthropic support,theBlueGuitarFund,aHarvardNeurodiscoveryCenter/MADRC Centerpilotgrantaward,anAlzheimer’sAssociationresearchgrant,theHarvardStemCellInstitute(HSCI)developmentgrant,andanHSCIseedgrant. T.J.M.acknowledgessupportfromMEXTGrant-in-AidforScientificResearch (19H05646),MEXTGrant-in-AidforScientificResearchonInnovativeAreas (17H05591,17H05986,and19H05233),andtheRIKENCenterforBrain Science.

REFERENCES Abdou,K.,Shehata,M.,Choko,K.,Nishizono,H.,Matsuo,M.,Muramatsu,S.I.,andInokuchi,K.(2018).Synapse-specificrepresentationoftheidentityof overlappingmemoryengrams.Science 360,1227–1231.

Arnold,A.E.G.F.,Ekstrom,A.D.,andIaria,G.(2018).Dynamicneuralnetwork reconfigurationduringthegenerationandreinstatementofmnemonicrepresentations.Front.Hum.Neurosci. 12,292.

Perspective Aronov,D.,Nevers,R.,andTank,D.W.(2017).Mappingofanon-spatial dimensionbythehippocampal-entorhinalcircuit.Nature 543,719–722.

Bakker,A.,Krauss,G.L.,Albert,M.S.,Speck,C.L.,Jones,L.R.,Stark,C.E., Yassa,M.A.,Bassett,S.S.,Shelton,A.L.,andGallagher,M.(2012).Reduction ofhippocampalhyperactivityimprovescognitioninamnesticmildcognitive impairment.Neuron 74,467–474.

Barry,D.N.,andMaguire,E.A.(2019a).Consolidatingthecasefortransient hippocampalmemorytraces.TrendsCogn.Sci. 23,635–636.

Barry,D.N.,andMaguire,E.A.(2019b).Remotememoryandthehippocampus:aconstructivecritique.TrendsCogn.Sci. 23,128–142.

Basu,J.,Zaremba,J.D.,Cheung,S.K.,Hitti,F.L.,Zemelman,B.V.,Losonczy, A.,andSiegelbaum,S.A.(2016).Gatingofhippocampalactivity,plasticity,and memorybyentorhinalcortexlong-rangeinhibition.Science 351,aaa5694.

Bender,F.,Gorbati,M.,Cadavieco,M.C.,Denisova,N.,Gao,X.,Holman,C., Korotkova,T.,andPonomarenko,A.(2015).Thetaoscillationsregulatethe speedoflocomotionviaahippocampustolateralseptumpathway.Nat.Commun. 6,8521.

Benna,M.K.,andFusi,S.(2019).Areplacecellsjustmemorycells?Memory compressionleadstospatialtuningandhistorydependence.bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/624239

Besnard,A.,andSahay,A.(2016).Adulthippocampalneurogenesis,fear generalization,andstress.Neuropsychopharmacology 41,24–44.

Besnard,A.,Gao,Y.,TaeWooKim,M.,Twarkowski,H.,Reed,A.K.,Langberg, T.,Feng,W.,Xu,X.,Saur,D.,Zweifel,L.S.,etal.(2019).Dorsolateralseptum somatostatininterneuronsgatemobilitytocalibratecontext-specificbehavioralfearresponses.Nat.Neurosci. 22,436–446.

Besnard,A.,Miller,S.M.,andSahay,A.(2020).DistinctdorsalandventralhippocampalCA3outputsgoverncontextualfeardiscrimination.CellRep. 30, 2360–2373.e5.

Bittner,K.C.,Milstein,A.D.,Grienberger,C.,Romani,S.,andMagee,J.C. (2017).BehavioraltimescalesynapticplasticityunderliesCA1placefields. Science 357,1033–1036.

Bloodgood,B.L.,Sharma,N.,Browne,H.A.,Trepman,A.Z.,andGreenberg, M.E.(2013).Theactivity-dependenttranscriptionfactorNPAS4regulates domain-specificinhibition.Nature 503,121–125.

Boehringer,R.,Polygalov,D.,Huang,A.J.Y.,Middleton,S.J.,Robert,V.,Wintzer,M.E.,Piskorowski,R.A.,Chevaleyre,V.,andMcHugh,T.J.(2017).Chronic lossofCA2transmissionleadstohippocampalhyperexcitability.Neuron 94, 642–655.e9.

Bonifazi,P.,Goldin,M.,Picardo,M.A.,Jorquera,I.,Cattani,A.,Bianconi,G., Represa,A.,Ben-Ari,Y.,andCossart,R.(2009).GABAergichubneurons orchestratesynchronyindevelopinghippocampalnetworks.Science 326, 1419–1424.

Burgess,N.,andO’Keefe,J.(2011).Modelsofplaceandgridcellfiringand thetarhythmicity.Curr.Opin.Neurobiol. 21,734–744.

Buzsa ´ ki,G.(2015).Hippocampalsharpwave-ripple:acognitivebiomarkerfor episodicmemoryandplanning.Hippocampus 25,1073–1188.

Buzsaki,G.,andTingley,D.(2018).Spaceandtime:thehippocampusasa sequencegenerator.TrendsCogn.Sci. 22,853–869.

Cai,D.J.,Aharoni,D.,Shuman,T.,Shobe,J.,Biane,J.,Song,W.,Wei,B., Veshkini,M.,La-Vu,M.,Lou,J.,etal.(2016).Asharedneuralensemblelinks distinctcontextualmemoriesencodedcloseintime.Nature 534,115–118.

Cardin,J.A.(2018).Inhibitoryinterneuronsregulatetemporalprecisionand correlationsincorticalcircuits.TrendsNeurosci. 41,689–700.

Caroni,P.(2015).Inhibitorymicrocircuitmodulesinhippocampallearning. Curr.Opin.Neurobiol. 35,66–73.

Carrillo-Reid,L.,Han,S.,Yang,W.,Akrouh,A.,andYuste,R.(2019).Controllingvisuallyguidedbehaviorbyholographicrecallingofcorticalensembles. Cell 178,447–457.e5.

Cayco-Gajic,N.A.,andSilver,R.A.(2019).Re-evaluatingcircuitmechanisms underlyingpatternseparation.Neuron 101,584–602.

Pleasecitethisarticleinpressas:Goodeetal.,AnIntegratedIndex:Engrams,PlaceCells,andHippocampalMemory,Neuron(2020),https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuron.2020.07.011

Cembrowski,M.S.,andSpruston,N.(2019).Heterogeneitywithinclassicalcell typesistherule:lessonsfromhippocampalpyramidalneurons.Nat.Rev.Neurosci. 20,193–204.

Chen,S.,He,L.,Huang,A.J.Y.,Boehringer,R.,Robert,V.,Wintzer,M.E.,Polygalov,D.,Weitemier,A.Z.,Tao,Y.,Gu,M.,etal.(2020).Ahypothalamicnovelty signalmodulateshippocampalmemory.Nature,inpress.

Choi,J.-H.,Sim,S.-E.,Kim,J.-I.,Choi,D.I.,Oh,J.,Ye,S.,Lee,J.,Kim,T.,Ko, H.-G.,Lim,C.-S.,andKaang,B.K.(2018).Interregionalsynapticmapsamong engramcellsunderliememoryformation.Science 360,430–435.

ChristensonWick,Z.,Tetzlaff,M.R.,andKrook-Magnuson,E.(2019).Novel long-rangeinhibitorynNOS-expressinghippocampalcells.eLife 8,e46816.

Ciocchi,S.,Passecker,J.,Malagon-Vina,H.,Mikus,N.,andKlausberger,T. (2015).Braincomputation.SelectiveinformationroutingbyventralhippocampalCA1projectionneurons.Science 348,560–563.

Cohen,N.J.,andEichenbaum,H.(1993).Memory,Amnesia,andTheHippocampalSystem(MITPress).

Colgin,L.L.,Leutgeb,S.,Jezek,K.,Leutgeb,J.K.,Moser,E.I.,McNaughton, B.L.,andMoser,M.-B.(2010).Attractor-mapversusautoassociationbased attractordynamicsinthehippocampalnetwork.J.Neurophysiol. 104,35–50.

Corcoran,K.A.,Frick,B.J.,Radulovic,J.,andKay,L.M.(2016).Analysisof coherentactivitybetweenretrosplenialcortex,hippocampus,thalamus,and anteriorcingulatecortexduringretrievalofrecentandremotecontextfear memory.Neurobiol.Learn.Mem. 127,93–101.

Cowansage,K.K.,Shuman,T.,Dillingham,B.C.,Chang,A.,Golshani,P.,and Mayford,M.(2014).Directreactivationofacoherentneocorticalmemoryof context.Neuron 84,432–441.

DeNardo,L.A.,Liu,C.D.,Allen,W.E.,Adams,E.L.,Friedmann,D.,Fu,L., Guenthner,C.J.,Tessier-Lavigne,M.,andLuo,L.(2019).Temporalevolution ofcorticalensemblespromotingremotememoryretrieval.Nat.Neurosci. 22, 460–469.

Denny,C.A.,Kheirbek,M.A.,Alba,E.L.,Tanaka,K.F.,Brachman,R.A.,Laughman,K.B.,Tomm,N.K.,Turi,G.F.,Losonczy,A.,andHen,R.(2014).Hippocampalmemorytracesaredifferentiallymodulatedbyexperience,time,and adultneurogenesis.Neuron 83,189–201.

Eichenbaum,H.,Otto,T.,andCohen,N.J.(1994).Twofunctionalcomponents ofthehippocampalmemorysystem.Behav.BrainSci. 17,449–472.

Erwin,S.R.,Sun,W.,Copeland,M.,Lindo,S.,Spruston,N.,andCembrowski, M.S.(2020).Asparse,spatiallybiasedsubtypeofmaturegranulecelldominatesrecruitmentinhippocampal-associatedbehaviors.CellRep. 31, 107551.

Fanselow,M.S.(2000).Contextualfear,gestaltmemories,andthehippocampus.Behav.BrainRes. 110,73–81.

Fanselow,M.S.,andDong,H.-W.(2010).Arethedorsalandventralhippocampusfunctionallydistinctstructures?Neuron 65,7–19.

Foster,D.J.(2017).Replaycomesofage.Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 40,581–602. Gelbard-Sagiv,H.,Mukamel,R.,Harel,M.,Malach,R.,andFried,I.(2008). Internallygeneratedreactivationofsingleneuronsinhumanhippocampus duringfreerecall.Science 322,96–101.

Ghandour,K.,Ohkawa,N.,Fung,C.C.A.,Asai,H.,Saitoh,Y.,Takekawa,T., Okubo-Suzuki,R.,Soya,S.,Nishizono,H.,Matsuo,M.,etal.(2019).Orchestratedensembleactivitiesconstituteahippocampalmemoryengram.Nat. Commun. 10,2637.

Gonzalez,W.G.,Zhang,H.,Harutyunyan,A.,andLois,C.(2019).Persistence ofneuronalrepresentationsthroughtimeanddamageinthehippocampus. Science 365,821–825.

Graves,A.R.,Moore,S.J.,Bloss,E.B.,Mensh,B.D.,Kath,W.L.,andSpruston, N.(2012).Hippocampalpyramidalneuronscomprisetwodistinctcelltypes thatarecountermodulatedbymetabotropicreceptors.Neuron 76,776–789.

Grosenick,L.,Marshel,J.H.,andDeisseroth,K.(2015).Closed-loopandactivity-guidedoptogeneticcontrol.Neuron 86,106–139.

Guenthner,C.J.,Miyamichi,K.,Yang,H.H.,Heller,H.C.,andLuo,L.(2013). PermanentgeneticaccesstotransientlyactiveneuronsviaTRAP:targeted recombinationinactivepopulations.Neuron 78,773–784.

Guo,N.,Soden,M.E.,Herber,C.,Kim,M.T.,Besnard,A.,Lin,P.,Ma,X., Cepko,C.L.,Zweifel,L.S.,andSahay,A.(2018).Dentategranulecellrecruitmentoffeedforwardinhibitiongovernsengrammaintenanceandremote memorygeneralization.Nat.Med. 24,438–449.

Guskjolen,A.,Kenney,J.W.,delaParra,J.,Yeung,B.A.,Josselyn,S.A.,and Frankland,P.W.(2018).Recoveryof‘‘lost’’infantmemoriesinmice.Curr. Biol. 28,2283–2290.e3.

Haberman,R.P.,Branch,A.,andGallagher,M.(2017).Targetingneuralhyperactivityasatreatmenttostemprogressionoflate-onsetAlzheimer’sdisease. Neurotherapeutics 14,662–676.

Hainmueller,T.,andBartos,M.(2018).Parallelemergenceofstableanddynamicmemoryengramsinthehippocampus.Nature 558,292–296.

Hainmueller,T.,andBartos,M.(2020).Dentategyruscircuitsforencoding, retrievalanddiscriminationofepisodicmemories.Nat.Rev.Neurosci. 21, 153–168.

Halassa,M.M.,andSherman,S.M.(2019).Thalamocorticalcircuitmotifs:a generalframework.Neuron 103,762–770.

Harand,C.,Bertran,F.,LaJoie,R.,Landeau,B.,Me ´ zenge,F.,Desgranges,B., Peigneux,P.,Eustache,F.,andRauchs,G.(2012).Thehippocampusremains activatedoverthelongtermfortheretrievaloftrulyepisodicmemories.PLoS ONE 7,e43495.

Hashimotodani,Y.,Karube,F.,Yanagawa,Y.,Fujiyama,F.,andKano,M. (2018).Supramammillarynucleusafferentstothedentategyrusco-release glutamateandGABAandpotentiategranulecelloutput.CellRep. 25,2704–2715.e4.

Howard,M.W.,andEichenbaum,H.(2015).Timeandspaceinthehippocampus.BrainRes. 1621,345–354.

Huff,N.C.,Frank,M.,Wright-Hardesty,K.,Sprunger,D.,Matus-Amat,P.,Higgins,E.,andRudy,J.W.(2006).Amygdalaregulationofimmediate-earlygene expressioninthehippocampusinducedbycontextualfearconditioning. J.Neurosci. 26,1616–1623.

Igarashi,K.M.,Lu,L.,Colgin,L.L.,Moser,M.-B.,andMoser,E.I.(2014).Coordinationofentorhinal-hippocampalensembleactivityduringassociative learning.Nature 510,143–147.

Jackson,J.,Smith,J.B.,andLee,A.K.(2020).Theanatomyandphysiologyof claustrum-cortexinteractions.Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 43,231–247.

Jinno,S.(2009).Structuralorganizationoflong-rangeGABAergicprojection systemofthehippocampus.Front.Neuroanat. 3,13.

Jonker,T.R.,Dimsdale-Zucker,H.,Ritchey,M.,Clarke,A.,andRanganath,C. (2018).Neuralreactivationinparietalcortexenhancesmemoryforepisodically linkedinformation.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 115,11084–11089.

Joo,H.R.,andFrank,L.M.(2018).Thehippocampalsharpwave-ripplein memoryretrievalforimmediateuseandconsolidation.Nat.Rev.Neurosci. 19,744–757.

Josselyn,S.A.,andFrankland,P.W.(2018).Memoryallocation:mechanisms andfunction.Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 41,389–413.

Josselyn,S.A.,andTonegawa,S.(2020).Memoryengrams:recallingthepast andimaginingthefuture.Science 367,eaaw4325.

Kesner,R.P.,andRolls,E.T.(2015).Acomputationaltheoryofhippocampal function,andtestsofthetheory:newdevelopments.Neurosci.Biobehav. Rev. 48,92–147.

Ketz,N.,Morkonda,S.G.,andO’Reilly,R.C.(2013).Thetacoordinatederrordrivenlearninginthehippocampus.PLoSComput.Biol. 9,e1003067.

Khalaf,O.,Resch,S.,Dixsaut,L.,Gorden,V.,Glauser,L.,andGraff,J.(2018). Reactivationofrecall-inducedneuronscontributestoremotefearmemory attenuation.Science 360,1239–1242.

Neuron 107,September9,2020 13

Kitamura,T.,Ogawa,S.K.,Roy,D.S.,Okuyama,T.,Morrissey,M.D.,Smith, L.M.,Redondo,R.L.,andTonegawa,S.(2017).Engramsandcircuitscrucial forsystemsconsolidationofamemory.Science 356,73–78.

Knierim,J.J.,andNeunuebel,J.P.(2016).Trackingtheflowofhippocampal computation:patternseparation,patterncompletion,andattractordynamics. Neurobiol.Learn.Mem. 129,38–49.

Knott,G.J.,andDoudna,J.A.(2018).CRISPR-Casguidesthefutureofgenetic engineering.Science 361,866–869.

Krasne,F.B.,Cushman,J.D.,andFanselow,M.S.(2015).ABayesiancontext fearlearningalgorithm/automaton.Front.Behav.Neurosci. 9,112.

Lacagnina,A.F.,Brockway,E.T.,Crovetti,C.R.,Shue,F.,McCarty,M.J.,Sattler,K.P.,Lim,S.C.,Santos,S.L.,Denny,C.A.,andDrew,M.R.(2019).Distinct hippocampalengramscontrolextinctionandrelapseoffearmemory.Nat. Neurosci. 22,753–761.

Leal,S.L.,andYassa,M.A.(2018).Integratingnewfindingsandexamining clinicalapplicationsofpatternseparation.Nat.Neurosci. 21,163–173.

Lee,S.-H.,Marchionni,I.,Bezaire,M.,Varga,C.,Danielson,N.,Lovett-Barron, M.,Losonczy,A.,andSoltesz,I.(2014).Parvalbumin-positivebasketcells differentiateamonghippocampalpyramidalcells.Neuron 82,1129–1144.

Lein,E.S.,Hawrylycz,M.J.,Ao,N.,Ayres,M.,Bensinger,A.,Bernard,A.,Boe, A.F.,Boguski,M.S.,Brockway,K.S.,Byrnes,E.J.,etal.(2007).Genome-wide atlasofgeneexpressionintheadultmousebrain.Nature 445,168–176.

Leroy,F.,Park,J.,Asok,A.,Brann,D.H.,Meira,T.,Boyle,L.M.,Buss,E.W., Kandel,E.R.,andSiegelbaum,S.A.(2018).AcircuitfromhippocampalCA2 tolateralseptumdisinhibitssocialaggression.Nature 564,213–218.

Li,Y.,Bao,H.,Luo,Y.,Yoan,C.,Sullivan,H.A.,Quintanilla,L.,Wickersham,I., Lazarus,M.,Shin,Y.I.,andSong,J.(2020).Supramammillarynucleussynchronizeswithdentategyrustoregulatespatialmemoryretrievalthrough glutamaterelease.eLife 9,9.

Lin,J.-J.,Rugg,M.D.,Das,S.,Stein,J.,Rizzuto,D.S.,Kahana,M.J.,andLega, B.C.(2017).Thetabandpowerincreasesintheposteriorhippocampuspredict successfulepisodicmemoryencodinginhumans.Hippocampus 27, 1040–1053.

Lisman,J.E.(1997).Burstsasaunitofneuralinformation:makingunreliable synapsesreliable.TrendsNeurosci. 20,38–43.

Lisman,J.E.,andOtmakhova,N.A.(2001).Storage,recall,andnoveltydetectionofsequencesbythehippocampus:elaboratingontheSOCRATICmodel toaccountfornormalandaberranteffectsofdopamine.Hippocampus 11, 551–568.

Lisman,J.,Buzsaki,G.,Eichenbaum,H.,Nadel,L.,Ranganath,C.,andRedish,A.D.(2017).Viewpoints:howthehippocampuscontributestomemory, navigationandcognition.Nat.Neurosci. 20,1434–1447.

Liu,X.,Ramirez,S.,Pang,P.T.,Puryear,C.B.,Govindarajan,A.,Deisseroth, K.,andTonegawa,S.(2012).Optogeneticstimulationofahippocampal engramactivatesfearmemoryrecall.Nature 484,381–385.

MacDonald,C.J.,Lepage,K.Q.,Eden,U.T.,andEichenbaum,H.(2011).Hippocampal‘‘timecells’’bridgethegapinmemoryfordiscontiguousevents. Neuron 71,737–749.

Makino,Y.,Polygalov,D.,Bolanos,F.,Benucci,A.,andMcHugh,T.J.(2019). physiologicalsignatureofmemoryageintheprefrontal-hippocampalcircuit. CellRep. 29,3835–3846.e5.

Mao,D.,Neumann,A.R.,Sun,J.,Bonin,V.,Mohajerani,M.H.,andMcNaughton,B.L.(2018).Hippocampus-dependentemergenceofspatialsequence codinginretrosplenialcortex.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 115,8015–8018.

Maren,S.,Phan,K.L.,andLiberzon,I.(2013).Thecontextualbrain:implicationsforfearconditioning,extinctionandpsychopathology.Nat.Rev.Neurosci. 14,417–428.

Matus-Amat,P.,Higgins,E.A.,Barrientos,R.M.,andRudy,J.W.(2004).The roleofthedorsalhippocampusintheacquisitionandretrievalofcontextmemoryrepresentations.J.Neurosci. 24,2431–2439.

McClelland,J.L.,McNaughton,B.L.,andO’Reilly,R.C.(1995).Whythereare complementarylearningsystemsinthehippocampusandneocortex:insights

Perspective fromthesuccessesandfailuresofconnectionistmodelsoflearningandmemory.Psychol.Rev. 102,419–457.

McHugh,T.J.,Jones,M.W.,Quinn,J.J.,Balthasar,N.,Coppari,R.,Elmquist, J.K.,Lowell,B.B.,Fanselow,M.S.,Wilson,M.A.,andTonegawa,S.(2007). DentategyrusNMDAreceptorsmediaterapidpatternseparationinthehippocampalnetwork.Science 317,94–99.

Meira,T.,Leroy,F.,Buss,E.W.,Oliva,A.,Park,J.,andSiegelbaum,S.A. (2018).AhippocampalcircuitlinkingdorsalCA2toventralCA1criticalforsocialmemorydynamics.Nat.Commun. 9,4163.

Middleton,S.J.,andMcHugh,T.J.(2019).CA2:ahighlyconnectedintrahippocampalrelay.Annu.Rev.Neurosci. 43,55–72.

Miller,S.M.,andSahay,A.(2019).Functionsofadult-bornneuronsinhippocampalmemoryinterferenceandindexing.Nat.Neurosci. 22,1565–1575.

Moscovitch,M.,andNadel,L.(2019).Sculptingremotememory:enduringhippocampaltracesandvmPFCreconstructiveprocesses.TrendsCogn.Sci. 23, 634–635.

Moser,E.I.,Moser,M.-B.,andMcNaughton,B.L.(2017).Spatialrepresentationinthehippocampalformation:ahistory.Nat.Neurosci. 20,1448–1464. Nadel,L.,andMoscovitch,M.(1997).Memoryconsolidation,retrograde amnesiaandthehippocampalcomplex.Curr.Opin.Neurobiol. 7,217–227. Nadel,L.,Hoscheidt,S.,andRyan,L.R.(2013).Spatialcognitionandthehippocampus:theanterior-posterioraxis.J.Cogn.Neurosci. 25,22–28.

Nakazawa,K.,Quirk,M.C.,Chitwood,R.A.,Watanabe,M.,Yeckel,M.F.,Sun, L.D.,Kato,A.,Carr,C.A.,Johnston,D.,Wilson,M.A.,andTonegawa,S.(2002). RequirementforhippocampalCA3NMDAreceptorsinassociativememory recall.Science 297,211–218.

O’Keefe,J.,andDostrovsky,J.(1971).Thehippocampusasaspatialmap. Preliminaryevidencefromunitactivityinthefreely-movingrat.BrainRes. 34,171–175.

O’Keefe,J.,andNadel,L.(1978).TheHippocampusasaCognitiveMap(OxfordUniversityPress).

Ognjanovski,N.,Maruyama,D.,Lashner,N.,Zochowski,M.,andAton,S.J. (2014).CA1hippocampalnetworkactivitychangesduringsleep-dependent memoryconsolidation.Front.Syst.Neurosci. 8,61.

Oh,M.M.,Oliveira,F.A.,Waters,J.,andDisterhoft,J.F.(2013).Alteredcalcium metabolisminagingCA1hippocampalpyramidalneurons.J.Neurosci. 33, 7905–7911.

Ohkawa,N.,Saitoh,Y.,Suzuki,A.,Tsujimura,S.,Murayama,E.,Kosugi,S., Nishizono,H.,Matsuo,M.,Takahashi,Y.,Nagase,M.,etal.(2015).Artificialassociationofpre-storedinformationtogenerateaqualitativelynewmemory. CellRep. 11,261–269.

Oishi,N.,Nomoto,M.,Ohkawa,N.,Saitoh,Y.,Sano,Y.,Tsujimura,S.,Nishizono,H.,Matsuo,M.,Muramatsu,S.-I.,andInokuchi,K.(2019).ArtificialassociationofmemoryeventsbyoptogeneticstimulationofhippocampalCA3cell ensembles.Mol.Brain 12,2.

PachecoEstefan,D.,Sanchez-Fibla,M.,Duff,A.,Principe,A.,Rocamora,R., Zhang,H.,Axmacher,N.,andVerschure,P.F.M.J.(2019).Coordinatedrepresentationalreinstatementinthehumanhippocampusandlateraltemporalcortexduringepisodicmemoryretrieval.Nat.Commun. 10,2255.

Pastalkova,E.,Itskov,V.,Amarasingham,A.,andBuzsaki,G.(2008).Internally generatedcellassemblysequencesintherathippocampus.Science 321, 1322–1327.

Pignatelli,M.,Ryan,T.J.,Roy,D.S.,Lovett,C.,Smith,L.M.,Muralidhar,S.,and Tonegawa,S.(2019).Engramcellexcitabilitystatedeterminestheefficacyof memoryretrieval.Neuron 101,274–284.e5.

Quiroz,Y.T.,Budson,A.E.,Celone,K.,Ruiz,A.,Newmark,R.,Castrillon,G., Lopera,F.,andStern,C.E.(2010).HippocampalhyperactivationinpresymptomaticfamilialAlzheimer’sdisease.Ann.Neurol. 68,865–875.

Raam,T.,McAvoy,K.M.,Besnard,A.,Veenema,A.H.,andSahay,A.(2017). Hippocampaloxytocinreceptorsarenecessaryfordiscriminationofsocial stimuli.Nat.Commun. 8,2001.

Ramirez,S.,Liu,X.,Lin,P.-A.,Suh,J.,Pignatelli,M.,Redondo,R.L.,Ryan, T.J.,andTonegawa,S.(2013).Creatingafalsememoryinthehippocampus. Science 341,387–391.

Ramirez,S.,Liu,X.,MacDonald,C.J.,Moffa,A.,Zhou,J.,Redondo,R.L.,and Tonegawa,S.(2015).Activatingpositivememoryengramssuppresses depression-likebehaviour.Nature 522,335–339.

Rao-Ruiz,P.,Couey,J.J.,Marcelo,I.M.,Bouwkamp,C.G.,Slump,D.E.,Matos,M.R.,vanderLoo,R.J.,Martins,G.J.,vandenHout,M.,vanIJcken, W.F.,etal.(2019).Engram-specifictranscriptomeprofilingofcontextualmemoryconsolidation.Nat.Commun. 10,2232.

Raza,S.A.,Albrecht,A.,C¸alıs¸kan,G.,Muller,B.,Demiray,Y.E.,Ludewig,S., Meis,S.,Faber,N.,Hartig,R.,Schraven,B.,etal.(2017).HIPPneuronsin thedentategyrusmediatethecholinergicmodulationofbackgroundcontext memorysalience.Nat.Commun. 8,189.

Redondo,R.L.,Kim,J.,Arons,A.L.,Ramirez,S.,Liu,X.,andTonegawa,S. (2014).Bidirectionalswitchofthevalenceassociatedwithahippocampal contextualmemoryengram.Nature 513,426–430.

Roux,L.,andBuzsa ´ ki,G.(2015).Tasksforinhibitoryinterneuronsinintact braincircuits.Neuropharmacology 88,10–23.

Roy,D.S.,Arons,A.,Mitchell,T.I.,Pignatelli,M.,Ryan,T.J.,andTonegawa,S. (2016).Memoryretrievalbyactivatingengramcellsinmousemodelsofearly Alzheimer’sdisease.Nature 531,508–512.

Roy,D.S.,Muralidhar,S.,Smith,L.M.,andTonegawa,S.(2017).Silentmemoryengramsasthebasisforretrogradeamnesia.Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.USA 114,E9972–E9979.

Roy,D.S.,Park,Y.-G.,Ogawa,S.K.,Cho,J.H.,Choi,H.,Kamensky,L.,Martin, J.,Chung,K.,andTonegawa,S.(2019).Brain-widemappingofcontextualfear memoryengramensemblessupportsthedispersedengramcomplexhypothesis.bioRxiv. https://doi.org/10.1101/668483