Preface

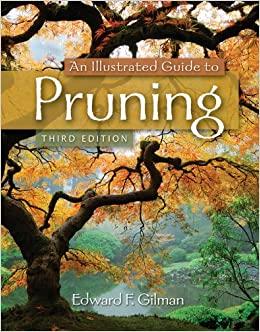

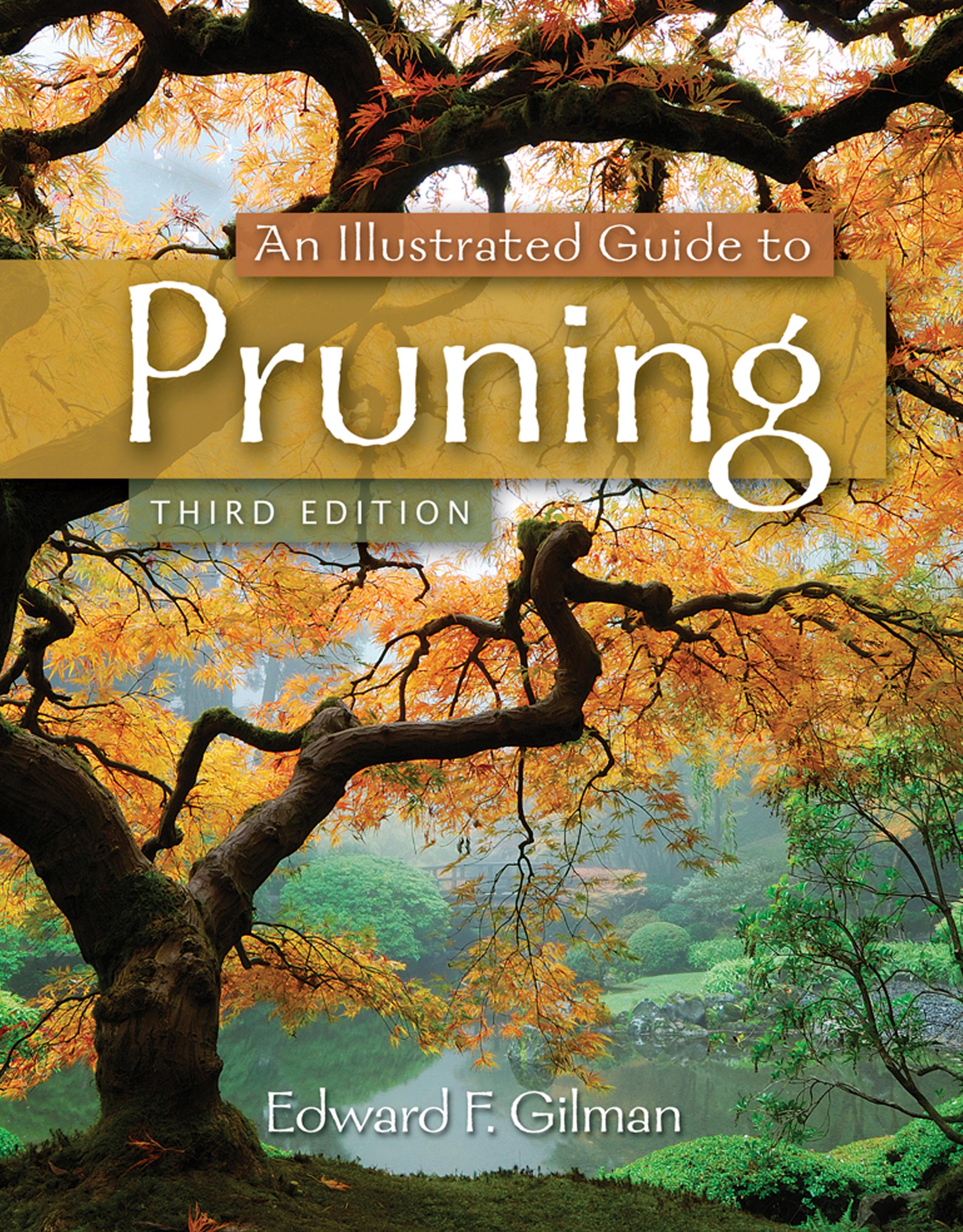

In a broad sense, the main objective of pruning is to extend the serviceable life of trees. Although this has not changed much, the techniques of pruning are ever changing as more professionals incorporate science-based research into their practice of tree and shrub pruning. The green revolution that has become popular in the past decade is driving some of the change, as people have become more aware of the benefits of durable, healthy trees. This third edition illustrates how new research and experience on structural pruning provides a basis for creating this durability. Now with more than 500 color photographs and illustrations, this edition provides an enhanced understanding of how pruning can guide tree growth into a form consistent with sustainable landscapes, resulting in strong trees with relatively-low inputs.

A thoroughly revised Introduction (Chapter 1) and Chapter 2 show designers, contractors, and horticulturists how to implement preventive strategies in the early stages of projects to reduce costly pruning later. Enhanced illustrative and photographic detail of tree structure explained in Chapter 3, in conjunction with response of wood to standard and substandard pruning in Chapter 4, provides a complete understanding of how and why small pruning cuts made often in the correct locations protect trunks against decay and other defects. Chapter 3 also incorporates a new understanding of tree failure patterns. The importance of pruning at planting to correct structural defects is strongly emphasized as well as pruning’s impact on disease transmission in the thoroughly revised Chapter 7.

Foremost in Chapters 8 through 13 is an examination of which stems and branches to remove from trees and shrubs to effect change in their architecture. This is the essence of pruning and the cornerstone of preventive arboriculture. Special care has been taken to present highly technical topics such as nursery pruning and mature-tree pruning in the landscape in a comprehensive yet understandable manner. A great deal of effort is put forth in the nursery production chapters, Chapters 8 and 9, to develop an appreciation in growers’ minds for why arborists prefer trees with exceptionally dominant leaders to the very top of the tree. The new Chapter 14 on mature-tree pruning and restoration addresses many scenarios commonly encountered in the field on large trees. Less focus is placed on fruit tree production, conifer, and shrub pruning because there are fewer pruning issues or many of the issues are similar to other plants.

The basic and advanced techniques presented in hundreds of real-world illustrations and color photographs will bring a new technical understanding to students and professionals alike. Many readers will find that they can gain tremendous insight simply by reviewing the illustrations, photos, and charts. Nursery operators, arborists, and landscape maintenance professionals will find this an indispensable guide for training employees and for sales. In addition to all of the common techniques, instructors will find that this text presents many new ideas and technology that are just beginning to emerge in the green industry. For example, the new Chapter 16 on root pruning brings an enormous amount of new information to the practical horticulture world on pruning and managing root systems in the nursery, at planting, and in established landscapes.

Many changes and additions have been made to the third edition of An Illustrated Guide to Pruning Most changes suggested by current users of this text were incorporated. Two new chapters were added, Chapters 14 and 16. A new Appendix 9 has been added on nursery stock specifications to help readers prepare a specifications document that calls for high-quality plants from the nursery. This description can serve as a model-tree for nurserymen to grow to, contractors to specify to, and researchers to research to. Appendix 9 also contains handy guides for root pruning, tree training, and planting. Through his extensive travel around the world, the author presents a global approach to pruning by including examples from temperate and tropical climates. The third edition of An Illustrated Guide to Pruning is a step closer to the complete pruning book.

ADDED FEATURES

• Two new chapters (Chapters 14 and 16) that detail mature tree pruning and root pruning, including their restoration following storms

• More than 200 new color photographs to provide examples of pruning trees in real-world situations

• More than 50 new illustrations for clarifying pruning cuts, tree structure, and specialized pruning techniques

• More than 100 citations of primary-source scientific articles to support concepts

• Additional tables for easy comparisons of treatments and response

• A clear picture of how trees respond to the different pruning methods, especially on large trees

• Numerous species examples of all pruning methods in all chapters

• Greatly expanded veteran tree care section

• Expanded shrub pruning chapter

• Improved writing style to make for easy reading

ENHANCED CONTENT

• Glossary entries now totaling nearly 300 terms

• A new approach to teaching mature tree care that includes structural pruning and retrenchment pruning

• Ways to describe the benefits of preventive structural pruning to customers

• Greatly expanded restoration pruning section, due to the tremendous damage caused by storms in the past decade

• Greatly expanded palm pruning section

• Addition of common and scientific names consistently throughout text

• Dozens of illustrations added and modified to include color photographs that expand understanding of important terms, concepts, and techniques

• Extensive coverage of the skills needed to conduct all the pruning methods for trees and shrubs in urban and suburban landscapes

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Dr. Gilman received his Ph.D. from Rutgers University in 1980 in forest plant pathology and is on the faculty as professor in the Environmental Horticulture Department at the University of Florida in Gainesville. He has assembled a unique urban tree teaching program for helping municipalities, contractors, arborists, educators, growers, landscapers, and others design and implement programs for promoting better tree health in cities. He conducts educational programs in tree selection, nursery production, and urban tree management nationwide for a large variety of audiences. Since 1990, he has received the Gunslogson Award in 2001 for his extension education programs and books from the American Society for Horticultural Science, one from the Florida Nursery and Growers Association for his contribution to the growers, one from the Florida Urban Forestry Council for his educational efforts in urban forestry and arboriculture, the Authors Citation Award in 1999 from the International Society of Arboriculture (ISA), the ISA Educators Award in 2003, and the ISA research award in 2007 for sustained excellence in research, publishing, and teaching timely information on tree care. Dr. Gilman is a Florida chapter ISA past-president. He has published more than 96 scientific, peer-reviewed journal articles in his 30 years in academia and industry. His research emphasizes tree pruning, nursery production, tree anchorage, and establishment techniques. He has published more than 150 technical articles in newsletters and trade magazines and annually presents research results to colleagues at professional meetings across the United States and in many other countries. He is the author of six books and maintains a complete website on urban trees. Dr. Gilman enjoys life in Gainesville, Florida, where he and his wife Betsy have raised two daughters, Samantha and Megan.

Introduction to Pruning

OBJECTIVES

Develop an understanding of how trees benefit from pruning. Present a protocol for inspecting, evaluating, and pruning trees. Introduce tree pruning objectives and strategies. Show the importance of improving trunk and branch structure.

Contrast faults in trees that are correctable and not correctable with pruning.

KEY WORDS

abiotic change biotic agent border tree codominant stem (branch) defect

growth regulator mature tree medium-aged tree poor structure (form) pruning dose pruning objective

root defect stage of life strong structure tree evaluation tree inspection young tree

INTRODUCTION

Pruning is the selective removal of plant parts to meet specific goals and objectives. One of the most compelling goals for many trees, planted or naturalized, is a long life span made possible by optimum trunk and branch structure (Figure 1-1). Poor structure (the arrangement and attributes of stems, trunk, branches, and roots), decay, and cracks in wood shorten the life of many trees, yet timely pruning can prevent premature tree failure and extend useful life span. This positions pruning at the heart of tree care and as one of the most efficient tree inputs. Proactive pruning before problems arise, or even after the tree has slight to moderate defects, requires fewer resources than tree removal which may be necessary when defects are severe. However, trees should always be pruned with a thorough understanding of what is to be accomplished, and why.

Tip: Proper pruning is one of the best things that can be done for a tree; improper pruning is one of the worst things that can be done to a tree (Dr. Alex Shigo).

Historically, pruning was performed in response to short-term desires of people, with less attention to effects on tree and shrub structure, stability, and health. These factors can be managed well, however, when tree biology and growth patterns are understood. This book examines basic elements (the science) before presenting the management principles and training (the techniques of pruning). A high-quality pruning program incorporates science and techniques to craft trees and shrubs that are healthy, structurally strong, and aesthetically pleasing.

Some think pruning trees is wasteful and unnecessary because, after all, trees in the forest grow just fine without it. What may not be obvious is only one in a billion seeds in the forest grows into a mature tree. In contrast, in urban and suburban landscapes, we expect almost every tree planted to grow old. Science-based pruning helps trees reach maturity, but misdirected pruning can shorten service life.

Young trees, such as those in a nursery, are in the early stage of life, rapidly growing in size and changing shape, so they benefit from routine training to guide branches into a strong structure. Pruning trees in the early stages of life helps reduce the risk of parts failing. Medium-aged trees, those in the middle stage of life, grow slower and expend considerable resources defending themselves against attacks from biotic agents such as disease, and responding to abiotic changes such as storm damage and poor pruning practices. Old and mature trees continue to grow in girth very slowly, and crown dimensions may actually shrink as decayed parts are removed or fall. Pruning treatments should be prescribed according to these three stages of life.

Planting nursery trees with good structure makes it easier for caretakers of trees in the landscape to guide the trees through this decades-long training process. Unfortunately, trees are sometimes pruned in the nursery in a manner that causes structural defects. These require pruning when planted into the landscape. The same goes for established trees in the landscape that are pruned incorrectly. Nursery operators, horticulturists, landscape managers, landscape architects, and arborists all have a responsibility to their customers to learn how to prune young trees to minimize expensive and destructive corrective measures later. Homeowners also should have a basic understanding of pruning to ensure that it is performed according to the highest standard. Pruning young trees every few years to prevent problems later is a simple process that does not require much time. It can be viewed as analogous to preventive medicine, which also is designed to prevent major problems by making minor adjustments often. Although pruning can provide structural improvements, it may not directly improve health.

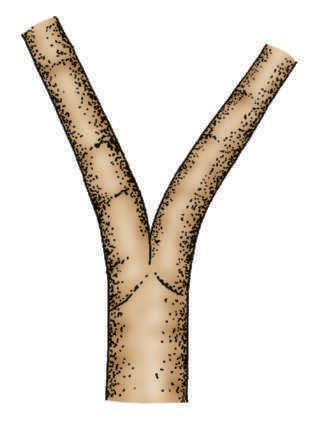

FIGURE 1-1. Ideal structure in a temperate willow oak (Quercus phellos) and white oak (Quercus alba) and tropical royal poinciana (Delonix regia). Note that branch diameters are considerably smaller than the trunk diameter.

© Cengage Learning, 2012.

Some people have difficulty accepting new pruning practices, or even grasping the concept of tree growth. Unlike anything else people encounter in their daily lives, trees must continue to grow larger every year in order to thrive, and yet branches remain in the same location on the tree. This confuses many people. Some can “see” what needs to be done after learning some

White oak Willow oak

Royal poinciana Ideal tree structure—dominant trunk with smaller branches

basic principles, while others need much more detail and many examples before grasping the concepts. This book teaches the concepts, strategies, and detail needed to understand, deliver and perform quality pruning.

Pruning that creates near-optimum structure, called structural pruning, results in trees better able to withstand stresses such as ice, snow, and wind storms. Homeowners, communities, and organizations that have implemented this method of pruning have found trees better able to withstand storms. Pruning live branches, including those in the upper part of the crown, is a big component of preventive tree care. Unfortunately, this is the part left unpruned by most contractors. A preventive program places trees under the care of a professional who develops a plan that includes a pruning program designed to meet these and other specific objectives. Specific pruning objectives should be defined with each pruning. Once objectives are established, each tree or group of trees is placed on a pruning cycle (discussed in Chapter 7) such as every two years.

Tip: Live branch pruning on the most aggressive branches to guide structure is crucial on young and medium-aged trees, and can be applied to mature trees as well.

The absence of a pruning book that includes enough detailed illustrations and photographs to be useful to students and professionals has led to this effort. Illustrations and photographs are of real trees and experiences from across the world. They serve as the basis for teaching because many find it difficult to learn from words alone. Despite the detail in these pages, the only way to really understand how to train trees with pruning is to learn basic tree growth and biology, and then go prune and watch how trees respond.

The concepts presented in the illustrations provide enough guidance to begin pruning trees quickly and efficiently. The photographs show that these concepts, when put into action, really can work as described. They are based on research and extensive experience of many individuals in nursery, landscape, and arboriculture professions. Some are new, experimental, and still under development. After reading portions of this book, apply a technique that you have not used before; this is challenging, and it can be a fun way to learn how trees react. To build confidence, first try the techniques on a small number of trees. Continue to prune the same trees over time and observe their response. Adjust your practices according to what you see. Then incorporate the techniques into your operation and teach others as you learn.

OBJECTIVES OF PRUNING

There are multiple objectives when it comes to pruning trees (Table 1-1). They range from improving the appearance of trees (aesthetics) to improving the tree structure. Each has a place in certain landscapes, depending on many factors including tree age and size, location, position of nearby objects, tree health, and others. One of the most important objectives of pruning trees is to reduce risk of failure and long-term maintenance by creating, maintaining, and developing or restoring strong structure. This is accomplished by guiding the tree’s architecture to produce a strong, functional, and pleasing form, and by removing conditions that increase risk of failure. To accomplish this and many of the other objectives, pruning should be performed at regular intervals, starting when the tree is young and continuing into maturity.

TABLE 1-1. Objectives of Pruning.

Reduce risk of failure

Provide clearance

Reduce shade and wind resistance

Maintain or improve health

© Cengage Learning, 2012.

Influence flower and fruit production

Improve view

Improve aesthetics

Increase life span

Early training prevents lateral branches and stems from growing too fast and spoiling good structure. It corrects substandard structure at planting. Like the time it takes to promote good behavior in children, it may take twenty to forty years of pruning at regular intervals to develop good trunk and branch structure in a shade tree, but only a small number of branches needs to be removed at each pruning cycle. With every pruning, live branches are removed to encourage growth in the moredesirable nonpruned parts of the tree. Pruning reduces growth on the pruned parts in proportion to the amount of foliage and live wood removed. More specific pruning objectives will be discussed in detail in later chapters.

In many ways, pruning corrects defects (Table 1-2). The pruner recognizes them early and decides on treatment. Young trees are pruned to develop strong structure by directing future growth so trees can live many years without creating unreasonable risk. Older trees are pruned to reduce risk by maintaining good structure, and to treat poor structure and other conditions that could place the tree, people, or property at risk (Figure 1-2). All defects in trees may not be correctable with pruning (Table 1-2; Figure 1-3).

Regardless of the stage of life, there is no harm in removing the portion of branches that are dead, broken, split, dying, diseased, or rubbing against others. However, indiscriminately removing branches with live foliage can reduce tree health and encourage development of weak structure. Anytime live branches are removed, some live wood transitions to nonliving wood behind even a well-executed pruning cut. This must be balanced against the improved structure that results from structural pruning. Removing a few small-diameter branches typically has little effect.

When discussing objectives with the client, the arborist should determine if the tree can tolerate removal of live branches. Very old trees, trees in poor health or on the decline, and trees with large sections of bark missing should only be cleaned to remove dead, dying, and diseased branches unless the tree poses excess risk by nature of its position in the landscape or its condition. Retaining live foliage and wood provides the most leaf tissue and can help trees maintain or regain health. Removing live branches slows recovery by reducing top and root growth. As an example, instead of pruning live branches from a historic tree with special importance to a community, consider other alternatives such as cabling, bracing, or propping to help keep the tree together, or consider application of growth regulators to arrest growth. Consider rerouting wires and other utilities instead of reducing a large tree to provide clearance.

Tip: Before removing any part of a tree, complete the following sentence, “I am removing this part because (your justification).” (Dr. Rex Bastian)

TABLE 1-2. Tree Defects and Pruning.

Defects in Young and Medium-Aged Trees Wholly or Partially Correctable with Pruning

Multiple leaders and codominant stems

Flat-topped crown

Branch or stem unions with bark inclusions

Rubbing branches

Insect- or disease-infested branches

Deformed branches

Upright growth from close nursery spacing

Dense crown

Branch stubs

Fast-growing branches on young trees

Dips in permanent limbs

Dead or weak branches

Circling and stem-girdling roots

Clustered branches

Unwanted flower or fruit production

Topped and storm-damaged trees

Interior branches removed

Structural root decay

Dense branch ends

Branchless trunks

Side branches taller than leader

Watersprouts

Defects in Medium-Aged and Mature Trees Partially Correctable with Pruning

Branch unions with bark inclusions

Branches with cracks

Dead branches

Branches blocking a view

Branches hanging over a building

Branches rubbing each other

Long branches with poor taper

Dense crown shading turf

Dense branch ends

Defects in Mature Trees Difficult to Correct with Pruning

Root loss, as during construction

Decayed large roots near trunk

Topped trees

Codominant stems

Trees with extreme dieback

Localized vascular wilt diseases

Trees topped through sapwood only

Lions-tailed trees

Storm-damaged trees

Leaning trees

Heavy branches with large diameter

Multiple branches clustered together

Unbalanced crown

Circling roots

Hollowed or decayed trunks

Heavy top

Crack in main branch or trunk

Sunken bark on underside of branch base

Large-diameter limbs clustered together

© Cengage Learning, 2012.

FIGURE 1-2. Trees with abundant, rapidly growing low branches eventually develop a form unsuitable for most landscapes (top left). The same tree fourteen years later had to be cleared of low branches because they were in the way (top right, arrow). A large 9-inch-diameter pruning wound resulted. Forks with bark inclusions are weak and break (center left). Trees with several main trunks emerging from the same point are weak (center right). Trees with many upright limbs emerging from the same point and with too many branches removed from the wrong crown position are prone to failure (bottom left). Some stormdamaged trees, such as this one, have correctable defects (bottom right).

© Cengage Learning, 2012.

Low, aggressive branches

Same tree 14 years later requires a 9" pruning cut

Codominant stem with bark inclusion

All limbs grow from one spot

All limbs growing upright

Damaged branches from hurricane

FIGURE 1-3. Horizontal cracks in the trunk like this one in a silver maple (Acer saccharinum) are difficult to remediate with pruning. This tree is leaning over a historic building, posing a fairly high risk.

© Cengage Learning, 2012.

PRUNING TREES TO IMPROVE STRUCTURE

Tree structure is the arrangement of stems and branches on the tree. Trees vary in their ideal structure. Some evolved in savannah areas to have broad-spreading crowns, while others evolved in forest settings where height growth was a key factor in species survival. Fruit trees have been grown under thousands of years of human cultivation with the desire to produce large amounts of fruit in a limited area. Therefore, tree form can be highly variable, but it is usually consistent within a range for a species or cultivar. A tree’s current form must be considered, along with the client’s objectives, when developing a pruning plan. For example, it is of paramount importance that shade and ornamental trees in urban areas have a strong structure, as it will result in fewer branch or whole-tree failures.

Trees that mature at a height of about 35 feet or more, such as many of the elms (Ulmus spp.), eucalyptus (Eucalyptus and Corymba spp.), oaks (Quercus spp.), and mahogany (Swietenia spp.) are trained so they develop branches adequately spaced along one dominant trunk perform best in storms (Duryea, Kampf, and Little, 2007). Optimum branch spacing depends on tree age and size. Branches considerably smaller in diameter than the trunk (preferably less than half) provide a strong connection to the tree (Gilman, 2003) and help the main trunk remain dominant (Gilman and Grabosky, 2009). Small-maturing, ornamental trees can be trained with one or several trunks, depending on the landscape situation and the wishes of the property owner. Fruit trees are pruned to create a trunk and branch architecture capable of holding easy-to-pick healthy fruit. Large, transplanted trees are pruned lightly for clearance and to correct structural problems.

PRUNING STRATEGIES

Pruning strategies should be matched with stage of life (Table 1-3). In the nursery, routine shortening or removal of certain live branches encourages durable structure suitable for urban landscape customers. The largest amount of foliage should be retained to maximize growth rate. Many growers remove too many branches in the lower 4 feet of the trunk too soon, resulting in slow

Young Trees in the Nursery

Reduce amount of circling roots with specially designed containers and/or root pruning

Establish strong structure by developing one dominant trunk and horizontal branches

Shorten or remove aggressive branches

TABLE 1-3. Strategies for Pruning Trees of Different Life Stages in Approximate Order of Importance.

Retain some shortened branches along lower trunk until about 12 months (warm climates) to 24 months (cooler climates) before marketing

Space main branches along trunk by shortening some and removing others

Eliminate rubbing and touching branches

Establish a pleasing form and full crown

Young Trees in the Landscape

Eliminate circling roots near the soil surface by cutting them so new roots grow away from the trunk

Establish strong structure by developing and maintaining one dominant trunk

Remove or shorten aggressive branches, especially those growing vertically

Space main branches along trunk by shortening some and removing others

Eliminate touching branches

Medium-Aged Trees

Cut girdling roots and other roots that circle close to the trunk so new roots grow away from trunk

Maintain or establish one dominant trunk by reducing length of others

Shorten branches below the lowest permanent limb

Shorten aggressive branches that will be in the way later

Prevent stems on low branches from growing up into the permanent crown

Space main branches 18 to 36 inches apart along the trunk by removing some and shortening others

Reduce length of overextended branches or those with bark inclusions

Remove dead branches where desirable

Eliminate rubbing or touching branches

Direct growth to fill gaps in the crown as desired

Mature Trees

Remove dead branches where desirable

Reduce length of overextended limbs or those with bark inclusions and cracks

Thin or reduce certain branches from the edge of the crown to reduce wind load

Remove as little live tissue as possible to accomplish objectives

Restore trees damaged by storms or overpruning

© Cengage Learning, 2012.

growth and in weak roots and trunk. Some will head the leader without follow-up pruning, resulting in undesirable multiple, upright leaders. Root defects in the nursery, at planting, and even on established trees are pruned away so the root system can maintain tree health and anchor the tree. Root pruning removes as few roots as possible to accomplish the goal of maintaining health and promoting anchorage to the soil.

Tip: It is better to remove a small amount of live foliage often than a lot all at once.

On medium-aged, large-maturing trees, regularly removing and/or shortening branches growing along the lower 25 feet of the trunk keeps the lower branches small and horizontal, which prepares the tree for the eventual removal of these branches. Pruning mature trees focuses on reducing conditions that place people or property at risk by removing dead branches and by reducing length on very long branches or those that are poorly attached, weak, or in the way.

Certain pruning practices, such as flush cuts, removing large branches and large codominant stems (equal-diameter stems growing from one point), and removing too many branches at once are well-known causes of decay, cracks, and other internal wood defects. This book illustrates how this happens and how to prevent it. It explains strategies that develop and maintain sound trunk and branch structure by removing small-diameter live branches, where practical, so large-branch removal becomes unnecessary. However, large-branch removal, as well as reduction in length of large branches, is also described because it is sometimes necessary.

INSPECT THE TREE BEFORE CLIMBING

Arborists should inspect trees before climbing or pruning to check for potentially unsafe conditions (Table 1-4). Tree inspection is the careful process of identifying conditions that could lead to tree failure while climbing. These conditions could result in a climber getting injured or killed while in the tree. Root defects are often the cause of tree failure, so be thorough in your inspection and understand your limits as a climber. Many pruning scenarios are beyond the capabilities of the typical homeowner and certain arborists. If in doubt about the condition of a tree, seek the assistance of an ISA Certified Arborist, a Registered Consulting Arborist, or Board Certified Master Arborist.

A climber’s weight and motion can lead to failure of defective tree parts initiated by trunk and branch decay, cracks, or a poor root system. Dead or broken hanging branches can become dislodged. Sprouts on a previously topped tree can fail if a climber secures a climbing line to them. Trees left standing alone following removal of surrounding trees can be unstable and fail from the added weight of a climber. Tree climbers abiding by all safety standards have the best chance of coming home every night. In the United States, the pertinent standard is American National Standards Institute (ANSI) Z133.

EVALUATE THE TREE BEFORE PRUNING

After inspecting the tree to determine if it is safe to climb, step away from it and walk around it before pruning the tree. This process of tree evaluation is crucial to providing quality tree care. Be sure to look at it from the most common viewing angle. Ask yourself what functions the tree