ADVANCESIN PARASITOLOGY

Editedby

DAVIDROLLINSON

LifeSciencesDepartment

TheNaturalHistoryMuseum, London,UnitedKingdom

RUSSELLSTOTHARD

DepartmentofTropical DiseaseBiology

LiverpoolSchoolofTropical Medicine,Liverpool,UnitedKingdom

AcademicPressisanimprintofElsevier 125LondonWall,LondonEC2Y5AS,UnitedKingdom TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates 525BStreet,Suite1650,SanDiego,CA92101,UnitedStates

Firstedition2022

Copyright©2022ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronic ormechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem, withoutpermissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,further informationaboutthePublisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuch astheCopyrightClearanceCenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions.

Thisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythe Publisher(otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperience broadenourunderstanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedical treatmentmaybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluating andusinganyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuch informationormethodstheyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,including partiesforwhomtheyhaveaprofessionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assume anyliabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability, negligenceorotherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideas containedinthematerialherein.

ISBN:978-0-323-98949-7

ISSN:0065-308X

ForinformationonallAcademicPresspublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: ZoeKruze

AcquisitionsEditor: LeticiaLima

DevelopmentalEditor: CindyAngelitaGardose

ProductionProjectManager: AbdullaSait

CoverDesigner: ChristianBilbow

TypesetbySTRAIVE,India

1.Themicroscopicfiveofthebigfive:Managingzoonoticdiseases withinandbeyondAfricanwildlifeprotectedareas1

AnyaV.Tober,DannyGovender,Isa-RitaM.Russo,andJoCable

1. Introduction2

2. The ‘MicroscopicFive’ 4

3. ChallengesofBTbcontrolatthewildlife-livestockinterface:TheSouth Africancasestudy10

4. Driversofdisease:TheKrugerNationalParkcasestudy13

5. DiseaseknowledgegapsandlessonslearntfromAfricanprotectedareas28

6. Communitiesandconservation33

7. Conclusions35 Acknowledgements37 References37

2.Improvingtranslationalpowerinantischistosomaldrug discovery47

AlexandraProbst,StefanBiendl,andJenniferKeiser

1. Fillingthedrugpipelineforschistosomiasis48

2. Evaluatingtheimportanceof S.mansoni isolateoriginforearly antischistosomaldrugdiscovery49

3. The S.mansoni mousemodelfordrugefficacytesting51

4. Infectionintensityofthepatent S.mansoni mousemodel54

5. Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic(PK/PD)relationshipofselecteddrugs56

6. Concludingremarks68

Acknowledgementsandfunding69 References69

3.Uniquethiolmetabolismintrypanosomatids:Redox homeostasisanddrugresistance75

VahabAli,SachidanandaBehera,AfreenNawaz,AsifEqubal, andKrishnaPandey

1. Introduction77

2. Trypanothionemetabolism80

3. Effectorproteinsoftheantioxidantdefence:Oldandnewactors90

4. Trypanothionemetabolismislinkedtocysteine,polyamine, andpentosephosphatepathway103

5. Theroleofredoxactivecompoundsandtheirmechanism inparasitessurvival110

6. Roleofthiolmetabolismindrugresistance118

7. Anti-parasiticpotentialofmoleculestargetedagainstredoxmetabolism123

8. Unsolvedquestionsandfutureprospects131

Acknowledgements132 References132

Contributors

VahabAli

LaboratoryofMolecularBiochemistryandCellBiology,DepartmentofBiochemistry, ICMR-RajendraMemorialResearchInstituteofMedicalSciences(RMRIMS),Patna, Bihar,India

SachidanandaBehera

LaboratoryofMolecularBiochemistryandCellBiology,DepartmentofBiochemistry, ICMR-RajendraMemorialResearchInstituteofMedicalSciences(RMRIMS),Patna, Bihar,India

StefanBiendl

SwissTropicalandPublicHealthInstitute,DepartmentofMedicalParasitologyand InfectionBiology;UniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

JoCable

SchoolofBiosciences,CardiffUniversity,Cardiff,Wales,UnitedKingdom

AsifEqubal

LaboratoryofMolecularBiochemistryandCellBiology,DepartmentofBiochemistry, ICMR-RajendraMemorialResearchInstituteofMedicalSciences(RMRIMS),Patna; DepartmentofBotany,ArariaCollege,PurneaUniversity,Purnia,Bihar,India

DannyGovender

SANParks,ScientificServices,SavannaandGrasslandResearchUnit,Pretoria;Department ofParaclinicalSciences,UniversityofPretoria,Onderstepoort,SouthAfrica

JenniferKeiser

SwissTropicalandPublicHealthInstitute,DepartmentofMedicalParasitologyand InfectionBiology;UniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

AfreenNawaz

LaboratoryofMolecularBiochemistryandCellBiology,DepartmentofBiochemistry, ICMR-RajendraMemorialResearchInstituteofMedicalSciences(RMRIMS),Patna, Bihar,India

KrishnaPandey

DepartmentofClinicalMedicine,ICMR-RajendraMemorialResearchInstituteofMedical Sciences(RMRIMS),Patna,Bihar,India

AlexandraProbst

SwissTropicalandPublicHealthInstitute,DepartmentofMedicalParasitologyand InfectionBiology;UniversityofBasel,Basel,Switzerland

Isa-RitaM.Russo

SchoolofBiosciences,CardiffUniversity,Cardiff,Wales,UnitedKingdom

AnyaV.Tober

SchoolofBiosciences,CardiffUniversity,Cardiff,Wales,UnitedKingdom

Themicroscopicfiveofthebig five:Managingzoonoticdiseases withinandbeyondAfricanwildlife protectedareas

AnyaV.Tobera,∗,DannyGovenderb,c,Isa-RitaM.Russoa,† , andJoCablea,†

aSchoolofBiosciences,CardiffUniversity,Cardiff,Wales,UnitedKingdom bSANParks,ScientificServices,SavannaandGrasslandResearchUnit,Pretoria,SouthAfrica cDepartmentofParaclinicalSciences,UniversityofPretoria,Onderstepoort,SouthAfrica

∗Correspondingauthor:e-mailaddress:tobera@cardiff.ac.uk

Contents

1. Introduction2

2. The ‘MicroscopicFive’ 4

2.1 Bovinetuberculosis7

2.2 RiftValleyfever7

2.3 Brucellosis8

2.4 Cryptosporidiosis8

2.5 Schistosomiasis9

3. ChallengesofBTbcontrolatthewildlife-livestockinterface:TheSouthAfrican casestudy10

3.1 Controlinlivestock10

3.2 Controlinwildlife10

4. Driversofdisease:TheKrugerNationalParkcasestudy13

4.1 Pastandpresentdiseasemanagement13

4.2 KrugerNationalPark’scurrentadaptivemanagementapproach14

4.3 Environmentaldriversofdiseasetransmission15

4.4 Anthropogenicdriversofdiseasetransmission:Wildlife-livestock-human interface23

5. DiseaseknowledgegapsandlessonslearntfromAfricanprotectedareas28

6. Communitiesandconservation33

7. Conclusions35 Acknowledgements37 References37 † Authorscontributedequallytothiswork.

AdvancesinParasitology,Volume117Copyright # 2022ElsevierLtd ISSN0065-308XAllrightsreserved. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.apar.2022.05.001

Abstract

Africanprotectedareasstrivetoconservethecontinent’ sgreatbiodiversitywitha targetedfocusontheflagship ‘ BigFive’ megafauna.Thoughoftennotconsidered, thisbiodiversityprotectionalsoextendst othelesser-knownmicrobesandparasites thataremaintainedinthesediverseecosyst ems,ofteninasilentandendemicallystablestate.Climateandanthropogenicchange,andassociateddiversityloss,however, arealteringthesedynamicsleadingtoshiftsinecologicalinteractionsandpathogen spilloverintonewnichesandhosts.AsmanyAfricanprotectedareasareborderedby gameandlivestockfarms,aswellasvillages,theyprovideanidealstudysystemto assessinfectiondynamicsatthehuman-live stock-wildlifeinterface.Herewereview fivezoonotic,multi-hostdiseases(bovinetuberculosis,brucellosis,RiftValleyfever, schistosomiasisandcryptosporidiosis) the ‘ MicroscopicFive’— anddiscussthe bioticandabioticdriversofparasitetransmissionusingtheiconicKrugerNational Park,SouthAfrica,asacasestudy.Weidentifyknowledgegapsregardingtheimpact ofthe ‘ MicroscopicFive ’ onwildlifewithinparksandhighlighttheneedformore empiricaldata,particularly forneglected(schistosomiasis)andnewlyemerging(cryptosporidiosis)diseases,aswellaszoonoticdiseaseriskfromtherisingbushmeat tradeandgamefarmindustry.Asprotectedareasstrivetobecomefurtherembedded inthesocio-economicsystemsthatsurroundthem,providingbenefitstolocalcommunities,OneHealthapproachescanhelpmaintaintheecologicalintegrityofecosystems,whileprotectinglocalcommunitiesandeconomiesfromthenegative impactsofdisease.

1.Introduction

Asweenterthesixthmassextinction,protectingtheworld’sbiodiversityhasneverbeenmorecritical.Protectedareas,includingnational parks,coverover18.8millionkm2 andareattheforefrontofaglobaleffort tosafeguardbiodiversity(Chapeetal.,2003).Managersoftheseprotected areasmuststrikeabalancebetweenprotectingtheecologicalintegrityof ecosystemsandpreventingexploitationoflocalresourceswhilepromoting theiruseineducationandrecreation(Chapeetal.,2003).Ifmanaged correctly,protectedareascanbebeneficialtowildlifeconservationand thecountry’seconomythroughpromotingecotourismandcreatinglocal employmentopportunities(Cheung,2012; Spiesetal.,2018).However, themanagementofprotectedareasischallenging,particularlyinthe Anthropoceneeraofhumanmediatedglobalchange,andincreased emergenceandre-emergenceofinfectiousdiseases(reviewedby Cable etal.,2017).Thesediseasescanreducefitness,alterwildlifepopulation

structure/sizeandevenalterecosystemfunction(Holdoetal.,2009; Prins andWeyerhaeuser,1987; Scott,1988).Therefore,toeffectivelymanage wildlifepopulationsandecosystems,itisessentialtounderstandthethreats posedbypathogensandthediseasestheycause.

Ofthe3881terrestrialandmarinenationalparksintheworld,almosthalf areinsub-SaharanAfrica,withterrestrialparksherecovering1million km2 (4%ofthetotallandarea; Chapeetal.,2003; Muhumuzaand Balkwill,2013).TheseparksaimtoconserveAfrica’suniqueandiconicecosystemsrangingfromopensavannasandgrasslandstodenseforest.Thisvarietyofhabitatssupportshighlevelsofbiodiversity,drawingnumerous touristswhoaspiretospotthe‘BigFive’megafauna:Africanbuffalo(hereafterreferredtoasbuffalo),lion,Africanelephant(hereafterreferredtoas elephant),rhinocerosandleopard(DubeandNhamo,2019).However, hiddenandoftenforgottenbiodiversitywithinprotectedareasincludes pathogens,whichmodulateanimalabundance,fitnessandbehaviour (Go ´ mezandNichols,2013).Itiscrucialtobetterunderstanddriversforpast andcurrentwildlifediseaseoutbreakswithinprotectedareas,tofindnew approachestopredictandpreventfutureoutbreaks.Areviewofallinfectiouswildlifediseaseswithinprotectedareaswouldbetoolargeatask. Instead,wefocusonfivediseasesreferredtohereasthe‘Microscopic Five’,whichareimportantatthehuman-livestock-wildlifeinterfacedue totheirbroadhostrangeandzoonoticpotential.Theseinterfacediseases wouldallbenefitfroma‘OneHealth’approachtomanagement(Fawzy andHelmy,2019; Innesetal.,2020; Websteretal.,2016).Wetherefore purposefullyincludedhighprofilediseases(bovinetuberculosis(BTb), RiftValleyfeverandbrucellosis)aswellasneglecteddiseases(cryptosporidiosisandschistosomiasis)forstudy.UsingKrugerNationalPark,oneofthe mostresearchedparksinAfrica(vanWilgenetal.,2016),wewillreviewthe keyfactorsthatcaninfluenceoutbreaksandtransmissionofthe‘Microscopic Five’withinandaroundprotectedareas(Fig.1).Byfocusingonaselect groupofpathogenswithinaspecificparkourintentionistohighlightdrivers ofdiseasecommonamongmanyprotectedareasandtheimportanceof consideringallinfectiousdiseasesinwildlifemanagementplans.Wewillfirst giveabriefintroductiontothe‘MicroscopicFive’andthengiveexamplesof theenvironmentalandanthropogenicfactorsdrivingthedynamicsofthese diseaseswithinandaroundKrugerNationalPark.Wewillthendiscussthe keyknowledgegapsandfuturechallengesformanagingthe‘Microscopic Five’andotherimportantdiseasesandtouchondifferentmanagement approachesfollowedinvariousparks.

Co-infections

Reservoir hosts

Mixing at waterholes

Fig.1 The ‘BigFive’ and ‘MicroscopicFive’,andthedriversofdiseaseatthewildlifelivestock-humaninterface.Arrowsrepresentanthropogenicdriversfrombeyond KrugerNationalPark. CreatedwithMicrosoftPowerPoint(version2109)andAdobe Photoshop(2021).

2.The ‘MicroscopicFive’

The‘BigFive’areundoubtedlyoneofthebiggestattractionsfortouristsvisitingSouthAfrica’sprotectedareas(DubeandNhamo,2019).To conservetheseandotherwildlife,andtoreducetransmissionofinfectious diseasesamongwildlife,domesticanimalsandhumans,wefocusonthe lesserknown‘MicroscopicFive’.Thesecomprisezoonoticdiseasescaused bypathogensthathavemultiplehosts,includinghumans,andareofparticularimportanceatthehuman-livestock-wildlifeinterface.Althoughwe focusonfivespecificdiseases,therearemanymoreofimportancewithin protectedareas(Table1)butbyhighlightingadistinctfewweaimtoraise theprofileofallinfectiousdiseasesandpossibledrivers.Thefirstthreeofthe ‘MicroscopicFive’(bovinetuberculosis,brucellosisandRiftValleyfever) arehighprofileorstate-controlleddiseasesinSouthAfricaandanyoutbreaksmustbereportedtotheWorldOrganisationofAnimalHealth (OIE).Allthreeofthesediseasesaretrade-sensitivediseasesandmaychange thetradingstatusofacountryanditsabilitytotradeontheglobalmarket. Theremainingtwo(schistosomiasisandcryptosporidiosis)areneglectedin

Microscopic Five

Big Five

trade

Table1 SomediseasesoflargeherbivoreswithinKrugerNationalParkwhichmayposeathreattolivestockand/orhumans.

Disease.Pathogen

Bacteria

Transmission modes Transmission routesDrivers

Spatial distributionin KNP Known susceptible hostsReservoirhosts

Anthrax Bacillusanthracis Vector, environmental, directcontact, fomites Ingestionof contaminated vegetationor carcasses Calciumsoil content,drought Northernand centralregions Most mammals including humans Maintained inenvironment

BovineTb Micobacteriabovis AerosolRespiratorytractWildlife/livestock interface,host density South,central, movingnorth Cattle, buffalo, humans Capebuffalo

Virus

Footandmouth Aphtovirus Aerosol, fomites RespiratorytractWildlife/livestock interface,host density North,central, south Cloven hooved animals Capebuffalo

Africanhorse sickness Orbivirus Mosquito vector,direct contact Cutaneous penetration Introducedhorses, season CentralZebra, domestic horses Culicoides mosquito, possiblyzebra

RiftValleyfever Phlebovirus Mosquito vector,direct contact Cutaneous penetration Climatechange, drought,rainfall Higherin southand centralregions Cattle, buffalo Aedes mosquito Capebuffalo

Continued

Table1 SomediseasesoflargeherbivoreswithinKrugerNationalParkwhichmayposeathreattolivestockand/orhumans.—cont’d

Disease.Pathogen

Protozoa

Transmission modes Transmission routesDrivers Spatial distributionin KNP Known susceptible hostsReservoirhosts

Bovine brucellosis Brucellaabortus DirectcontactIngestionof infected dischargesduring birth,milk,mucus membranes

Cryptosporidiosis Cryptosporidium spp.

HostdensityNorth,central, south Cattle, buffalo,wild animals, humans Capebuffalo

EnvironmentalFaecal-oralvia contaminationof foodandwater Dependanton speciesandhost range UnknownWild animals, humans, domestic animals Unknown

Piroplasma

Corridordisease Theileriaparva TickvectorCutaneous penetration Wildlife/livestock interface North,central, south CattleCapeBuffalo

Babesiosis Babesiaspp. TickvectorCutaneous penetration

Digenea

Fascioliasis Fasciola spp.EnvironmentalContactwith infectedwater Dependanton speciesandhost range

Schistosomiasis Schistsoma spp.EnvironmentalContactwith infectedwater Dependanton speciesandhost range

UnknownRhinoceros, lions Unknown

UnknownRuminantsUnknown

UnknownWild animals, humans Unknown

comparison,particularlyinwildlife.Byincludingtheseinthe‘Microscopic Five’,weaimtobringgreaterattentiontooverlookedyethighlyimportant diseases(see WHO,2020).Inthefollowingaccount,webrieflycovereach ofthe‘MicroscopicFive’discussingtheirhostspecificity,transmission pathwaysandknownimpactsonwildlife,livestockandhumans.

2.1Bovinetuberculosis

Bovinetuberculosis(BTb)iscausedbythebacterium Mycobacteriumbovis andpredominantlyinfectsbovines,suchasAfricanbuffalo(Synceruscaffer caffer)andcattle(Bostaurus),yetmostwarm-bloodedanimalsincluding humanscanbeinfected(Ayeleetal.,2004).Transmissionmainlyoccurs throughinhalationofinfectiousparticles,whichisparticularlyproblematic whenlivestockarekeptathighdensities(Ayeleetal.,2004).Though thoughttohavespilledoverfromcattletobuffalointheearly1960sin SouthAfrica(Bengisetal.,1996),buffalonowserveastheprimarymaintenancehostforBTbwithinKrugerNationalParkandHluhluwe-iMfolozi Park,spillingoverintovariousspeciesofwildlifeandlivestock(Micheletal., 2006).AlthoughBTbisacontrolleddiseasewithinSouthAfrica,itscontrol isbecomingincreasinglychallengingduetothepresenceofwildlifereservoirs,difficultyincontrollingdiseaseincommunalherdsandlackofpracticalcontroloptionsinwildlife(see Section3).TheWHOestimated 147,000newcasesofzoonoticTbinhumansin2016with12,500deaths globallybutmostlyinAfrica(Sichewoetal.,2019b).Humanscanbecome infectedthroughdrinkingunpasteurisedmilk,eatingundercookedmeatand viaaerosolsinhaledfrominfectedcattle(DAFF,2016; Sichewo etal.,2019a).

2.2RiftValleyfever

RiftValleyfever(RVF)iscausedbyazoonotic,vectorborneviruspredominantlyspreadby Aedes mosquitoes(Clarketal.,2018).Theviruswasfirst reportedinSouthAfricain1950andsubsequentoutbreakshaveoccurred sporadicallyevery7–11yearsinfectingmainlydomesticlivestockbutalso arangeofwildmammalsandhumans(Beechleretal.,2015a; Metras etal.,2015).Humaninfectionoccursmainlythroughdirectcontactwith bloodortissuefrominfectedanimalsorthroughconsumingunpasteurised milkbutcanalsoresultfromaninfectedmosquitobite.Symptomsvaryfrom mild,flu-liketoseverehaemorrhagicfeverthatcanbefatal(Clarketal., 2018).Over4000humancasesandaround1000deathshavebeenreported

inthelast20years,predominantlyinAfricaandSaudiArabia(Petrovaetal., 2020).Littleisknownabouthowthepathogenismaintainedduring inter-epidemicperiods.Onesuggestionisverticaltransmissionfrommosquitoestotheirova,whichhasbeendemonstratedwith Aedes mosquitoes underlaboratory-controlledconditions(Romoseretal.,2011).Another possibilityisthatitismaintainedinwildanimalpopulations(Beechler etal.,2015a;see Section4.3.4).Commercialvaccinesareavailableforlivestockbutthereiscurrentlynolicensedhumanvaccine(Petrovaetal.,2020).

2.3Brucellosis

Brucellosis,causedbybacteriaofthe Brucella genus,isrankedamongthe mosteconomicallyimportantzoonoticdiseasesglobally.Althoughitisan OIEnotifiabledisease,outbreaksarethoughttobegreatlyunder-reported inAfrica(McDermottetal.,2013).Thespeciesofmedicalandveterinary importanceare Brucellaabortus, Brucellamelitensis and B.suis (see Ducrotoy etal.,2017).Infectioninhumanscanleadtoadebilitatingillnessknown as‘Mediterranean’or‘undulant’feverandiscommonlymisdiagnosedas malaria(Ducrotoyetal.,2017; Godfroidetal.,2011).Humaninfection occursthroughdirectcontactwithorconsumptionofaninfectedanimal. Consumptionofun-pasteurisedmilkcausesmosthumaninfections,while humantohumantransmissionisrare(Godfroid,2018).SeveralwildlifespecieshavebeenreportedasseropositiveforthisdiseaseandAfricanbuffaloare thoughttobeareservoirfor B.abortus (see Godfroidetal.,2013).Infection cancauseabortionsinlivestockreducingfarmproductivity,howeverthe effectsofthediseaseonwildlifearelargelyunknownandmaydifferbetween species(Gorsichetal.,2015).Vaccinesareavailableforlivestockandsmall ruminantsbutnotyetforhumans(Ducrotoyetal.,2017).

2.4Cryptosporidiosis

Cryptosporidiosis,causedbyseveralspeciesoftheprotozoan Cryptosporidium genus, canleadtoseverediarrhoeainhumansandanimals globally.Infectiousdiarrhoeaisamajorcauseofdeathinchildrenunderfive inAfricaand Cryptosporidium issecondonlytorotavirusasacontributorto thisdisease(Kotloffetal.,2013; SquireandRyan,2017).Transmission occursthroughthefaecaloralrouteviaclosecontactwithinfectedhumans, animalsorcontaminatedfoodandwater(Innesetal.,2020).Currentlythere areatleast40recognisedspecieswithvaryinghostspecificitiesbutthemost importanttwospeciesinfectinghumansandlivestockare C.hominus and

C.parvum. Thelatteristhepredominantcauseofdiarrhoeainyoungcalves andisthemostimportantzoonoticspecies. Cryptosporidiumparvum ismore geneticallydiversethan C.hominus withseveralsubtypeswithdifferinghost specificities,thereforeanintegratedgenotypingapproachhasbeenadvocatedtodifferentiatethesesubtypes(Innesetal.,2020). Cryptosporidium specieshavebeenidentifiedinarangeofwildlife,yetmoststudiesfocus onhumansandlivestock(Zahedietal.,2016). C.parvum,C.ubiquitum andC.bovis wererecentlyidentifiedinwildlifewithinKrugerNational Parkinelephant(Loxodontaafricana),buffalo(Synceruscaffer)andimpala (Aepycerosmelampus;see Samraetal.,2011).Oocystsof Cryptosporidium spp.havealsobeendetectedinzebra(Equuszebra),buffaloandwildebeest (Connochaetesgnou)faecesinMikumiNationalPark,Tanzania(Mtambo etal.,1997).Thereiscurrentlynoavailablevaccineforcryptosporidiosis yetthereispotentialtodeveloponeforcattle(Innesetal.,2020).

2.5Schistosomiasis

Schistosomiasisisawaterborne,zoonoticdiseaseofveterinaryandmedical importance,causedbydigeneanparasitesofthegenus Schistosoma. Schistosomiasisisamajorpublichealththreatwithanestimated207million peopleinfectedand779millionpeopleatriskglobally,with90%ofthese infectionsinAfrica(Steinmannetal.,2006).Likealldigeneans,schistosomes haveanindirectlifecycle.Theyrequireanintermediatefreshwatersnailhost withinwhichtheyreproduceasexuallyultimatelyproducingcercariae, whicharefree-swimminglarvalstagesthatsubsequentlyinfectadefinitive mammalianhost(Cribbetal.,2003).Definitiveanimalorhumanhostscan becomeinfectedwithschistosomiasisbyenteringinfestedwaters—the water-bornelarvaeburrowthroughtheskinofthenewhost(Cribb etal.,2003).Thereareatleast12knownschistosomespeciesinAfricaof which5areknowntoinfecthumans(S.haematobium,Schistosoma mansoni,S.intercalatum,S.guineensis and S.mattheei). Schistosomamattheei isofnoteasalthoughpredominantlyaparasiteofcattle,ithasalsobeen foundinwildlifeandhumanswhereitisknowntohybridisewith S.haematobium (see Pitchford,1961).Theotherspeciesinfectawiderange ofdomesticandwildanimalsincludingcattle,horses,buffalo,baboons, zebra,hippopotamusandrodents(Standleyetal.,2012).Traditionally,malacologicalmonitoringprogrammeshaveonlytargetedsnailspeciesknown toharbourhumaninfectingschistosomes,butawiderapproachisclearly neededaswebecomeawareofwiderhostranges(Pennanceetal.,2021)

thatarelikelytoshiftwithincreasingenvironmentalstressors.Thereis currentlynovaccineforschistosomiasisandthemaincontrolstrategyfor humansispreventativechemotherapy,improvedwater,sanitationand hygieneandsnailcontrol(WHO,2022).

3.ChallengesofBTbcontrolatthewildlife-livestock

interface:TheSouthAfricancasestudy

SouthAfricahasbeenchallengedwiththecontrolofBTbsincethe diseasewasfirstreportedinthecountryin1880,initiallyfocusingonlivestock,andnowincludingcontrolinwildlife(DAFF,2016).

3.1Controlinlivestock

EarlyBTbsurveillanceincludedtheintroductionoftuberculinskintesting incattlein1905,followedbyitsdeclarationasanotifiablediseasein1911 andtheinitiationoftheDivisionofVeterinaryServicesBTbschemein1969 (DAFF,2016; Micheletal.,2019).Thisschemefocusedoncompulsory testingofcommercialcattleherdssuspectedtobeinfected,withslaughter ofpositiveindividuals,quarantineanddisinfectionoffarms.Initially,great progresswasmade,reducingprevalenceto0.04%by1991(1.1millioncattle tested);however,thenumberoftestshavesincedeclinedduetobudgetcuts andadecreasedworkforce(DAFF,2016; Micheletal.,2019).Currentprevalenceincommunallivestockisvariable(<0.5%to >15%)(Musokeetal., 2015; Sichewoetal.,2019b).

In2021thenationalcattleherdwasestimatedat12million,consistingof commercialdairyherds(20%)andbeefanddual-purposeherds(80%) (DAFF,2021).Testingofcattleisnolongercompulsoryandcurrentcontrol ofBTbisguidedbytheInterimBTbManualfromtheDepartmentof Agriculture,ForestryandFisheries(DAFF),SouthAfrica,whichproposes theuseoffourtestingprogrammes(Table2; DAFF,2016).Allprogrammes arevoluntaryapartfromtheinfectedherdprogram,whichcanbeenforced bytheAnimalDiseasesAct,1984(ActNo.35of1984)(DAFF,2016).The approvedtestisthecervicalintradermaltuberculin(CIT)test(DAFF,2016).

3.2Controlinwildlife

ThecontrolofBTbinwildlifeisbecomingincreasinglyimportantasmany farmsswitchfromlivestocktogamefarming,andwildbuffaloreservoirs hindercontroleffortsincattle(Micheletal.,2019).BovineTbhasbeen

Table2 FourlevelsofBovineTbsurveillanceprogrammesinSouthAfrica.

Surveillanceherd programme

Maintenanceherd programme

Oneoffsurveyusedbystateofficialstodeterminethe prevalenceofBTbwithinanareaorbyastockowner conductingaself-assessment

Tojointhisprogramme,herdsarerequiredto undergotwoconsecutivetestswith100%negative resultsatleast3monthsapart.TheseBTbfreeherds arethentestedevery2years.Ifanindividualtests positive,thentheentireherdismovedtotheinfected herdprogramme

InfectedherdprogrammeCompulsoryprogrammeforherdsthathavetested positivewiththeCITtest,aswellasthosedetected frommeatandmilkinspection,post-mortemsor clinicalcases.Theseherdsareplacedunder quarantineandkeptundersupervisionofastate veterinarian,whowillordertheslaughterofinfected animals.Therestoftheherdistestedevery3months andisonlyletoutofquarantineoncetheherdhas undergonetwoconsecutivenegativetests

Diagnostictesting programme(individuals)

Individualcattledestinedtobeimportedorexported. Importedcattlearekeptinquarantineandmust undergoacompulsoryCITtest.Beforeexport,cattle mustalsoreceiveacomparativeCITtest—a requirementformanyimportingcountries

identifiedin21differentwildlifespeciesinSouthAfrica,includingmost recentlygiraffe(Hlokweetal.,2019).Thecurrentcontrolschemeisfocused ondomesticcattleandalthoughsometestshavebeenadjustedforuseinbuffalo,thisisnotthecaseforotherwildlifespecies.TheBuffaloVeterinary ProceduralNotice(VPN)waspublishedin2017outliningtheprocedures fordiseasetesting,movementandcontingencyplanningfordiseaseoutbreaksinbuffalo(DAFF,2017).ThebuffaloVPNstatesthatformovement purposes,buffalomusthaveanegativeCITtestasoutlinedinthemanualfor cattle.Importantly,theinterpretationofCIThasbeenbasedoncattle thresholdsduetothelackofspecies-specificcut-offvaluesforAfricanbuffaloes.ThegammainterferontestisalsoaneffectivediagnostictoolforbuffalobutisnotapprovedbyDAFFformovementpurposes.Thereis currentlynoguidanceoncontrolofBTbinotherwildlifespeciesandthere arelimitedverifieddiagnostictestsinthesespecies(DAFF,2017).

KrugerNationalParkandHluhluwe-iMfoloziParkaretheonlytwo parkswithinSouthAfricathatcontainbuffaloherdsmaintainingBTbyet theyhaveadopteddifferentcontrolapproaches.BovineTbwasfirst detectedinHluhluwe-iMfoloziParkin1986andatestandculldiseaseprogrammewasinitiatedin1999.Thisprogrammeinvolvedamobilecapture unittocorralbuffaloindifferentareasofthepark,testthembymeansof theCITtestandcullingpositiveindividuals.Between1991and2006, 4733buffaloweretested,withherdprevalencerangingfrom2.3%to 54.7%.Subsequent,dataanalysissuggestedthattheprogrammewaseffective atreducingBTbprevalence,particularlyinareaswithintensivetestandcullingoperations(LeRoexetal.,2016).KrugerNationalParktookadifferent approachtomanagingBTbinitsbuffalopopulationafterthediseasewas detectedinthishostspeciesin1990.Theyaimedtobreeddiseasefreebuffalo fromFootandMouthDiseaseinfectedparentswithintheparkinorderto conservethegeneticpoolofKrugerbuffaloinanex-situpopulation (LaubscherandHoffman,2012).Thisapproach,whichuseddairycows asfosterparentsforbuffalocalvesinitially,andlaterswitchedtohaving thebuffalomothersreartheiryoung,washighlysuccessfulandalsopopular withfarmers,eventuallyshiftingfromafewgovernmentfundedprojectsto hundredsofprivatebuffalobreedingfarms(LaubscherandHoffman,2012). Additionally,KrugerNationalParkdidextensiveBTbmonitoringsurveys between1993and2007,toassessthespreadandimpactofBTbinherds,and determineifthediseasewashavingpopulationleveleffects.Sinceitentered thepark,BTbhasbeendetectedin12spill-overspecies(Micheletal.,2006) andremainsaconcerninlowdensityspecies,suchaswilddogandblack rhinoceros(Higgittetal.,2019).

Withthediseasecurrentlynotshowntobeaffectingpopulationrecruitmentorgrowthinbuffalo,therealconcernbecomesspill-overtoother hostsandthereforefindinganeffectivevaccinethatlimitsdiseaseseverity andspill-overisapriority.Currentlythereisonlyoneregisteredvaccine forBTbcontrol.TheBCGvaccineispredominantlyusedinhumansbut hasyieldedpromisingresultsforuseindomesticcattle(Arnotand Michel,2020).However,whentrialledinwildbuffalowithintheKruger NationalPark,theBCGvaccineprotectionwasinsufficientanddidnot limitbacterialshedding(DeKlerketal.,2010).Thiswasthoughttohave resultedfromprimingwithenvironmentalnon-TBmycobacteria,which hasbeenshowntoreducetheprotectiveefficacyoftheBCGvaccine (Brandtetal.,2002;DeKlerketal.,2010).Importantlysimilarstudiesin badgersintheUKfoundtheBCGvaccinetobeeffectiveinlimitingdisease

severity(andthereforebacterialload; Chambersetal.,2011),meaning thatdefiningtheclinicalendpointforvaccineefficacytrialsisimportant. Anothervaccinationtrialinbuffaloiscurrentlyunderway,testingboth BCGandDNA-sub-unitvaccines.

4.Driversofdisease:TheKrugerNationalPark

casestudy

4.1Pastandpresentdiseasemanagement

KrugerNationalParkfirstopenedastheSabiGameReservein1898 (10,364km2)asaresponsetocampaignsfortheconservationofwildanimals subjectedtouncontrolledhuntingandtothe1896rinderpestepidemic (Mabundaetal.,2003).In1926,theSabiGameReservewascombinedwith theSingwitsiReserve(5000km2 regionnamedaftertheShingwedziRiver) andlaterrenamedKrugerNationalPark.JamesStevenson-Hamilton,who wasappointedwardenin1902,wastaskedwithmanagingtheaftermathof therinderpestepidemicwhich,alongwithprevioushuntingactivities,decimatedthegamepopulation,leavingelephantandwhiterhinoceros (Ceratotheriumsimum)locallyextinct(Mabundaetal.,2003).Therinderpest epidemicalsoseverelyaffectedbuffalo,eland(Tragelaphusoryx)andgreater kudu(Tragelaphusstrepsiceros; hereafterreferredtoaskudu),whereaswildebeestandzebrawereunaffected(Stevenson-Hamilton,1957).Thefirst 60yearsofparkmanagement(1900–1960)focusedonprotecting,preserving,andpropagating,aimingtoincreasegamenumbersthroughintroductionsoflargeherbivores,provisionofwatersourcesandcullingofpredators (Venteretal.,2008).

ColonelJ.A.BSanderbergtookoverfromStevenson-Hamiltonas Wardenin1946and8yearslaterthefirstcaseofanthraxwasconfirmed inthenorthofthepark(Mabundaetal.,2003).Thiswasfollowedby repeatedoutbreaksin1959–60,1970and1990–91,andoutbreaksinthe centralpartoftheparkin1993and1999(Bengisetal.,2003; DeVos andBryden,1996).The1959–60outbreaklastedjust4monthsandyet withinthistimeover1000mammalsdied:kudu,waterbuck(Kobusellipsiprymnus)androan(Hippotragusequinus)beingthemostaffected(Pienaar, 1961).Simultaneously,BTblikelyenteredthepark,transmittedfromcattle tobuffaloonthesouthernborder,althoughitwasnotdetectedinthepark until30yearslater(Bengisetal.,1996).Atthistime,parkmanagement shiftedtoa‘managementbyintervention’approachandthenext30years (1960–1990)focusedonmeasuring,monitoringandmanipulation

(Mabundaetal.,2003).FencingoftheparkwasorderedbytheNational DepartmentofAgricultureinordertopreventthespreadofdiseaseto surroundinglivestock,suchasfootandmouth(FMD)endemicinbuffalo (Bengisetal.,2003).Fenceconstructionstartedintheearly1960swith thewesternboundaryfollowedbytheeasternboundaryinthelate1960s, by1980allboundariesoftheparkwereenclosed.Thefences(over 360kminlengthand65kminwidth)restrictedmovementofwildlifeleadingtoincreasednumbersoflargeherbivores,suchaselephantandbuffalo, whichweresubsequentlycontrolledbycullingoperationsandintheearly 1970s,acertifiedabattoirwasbuiltwithintheparktooptimiseuseofthe culledmeat(Mabundaetal.,2003).From1990to2010management shiftedagaintofocusonintegration,innovationandinternationalisation. Theseveredroughtof1992–93followedbytheFebruaryfloodsin2000 aswellasthecatastrophicwildfireinSeptember2001,whichkilledboth peopleandanimalswithinthepark,wereindicativeoftheneedformanagementtobecomemoreadaptivetotheincreasinglyunpredictableenvironment(Mabundaetal.,2003).Since1995,Krugerhasusedastrategic adaptivemanagementapproach,whichinvolvesmanagementdecisions andactionsguidedbyresearchandmonitoringwhilelearningfromunexpectedeventsoroutcomes.Thisapproachalsoaimstomaximiseheterogeneityoftheparkandledtoitsexpansionacrossnationalboundariescreating theGreaterLimpopotransfrontierconservationarea(GLTFCA)spanning theLimpopo(Mozambique),Kruger(SouthAfrica)andGonarezhou (Zimbabwe)NationalParks.Aportionoffencesofapproximately45km wasremovedbetweenLimpopoandKrugerin2002(Caronetal.,2016; Venteretal.,2008).

4.2KrugerNationalPark’scurrentadaptivemanagement approach

Inthepast,mostmanagementissuesinKrugerNationalParkwerefocused withintheparkboundaries;however,sincetherecognitionthatthreatsand driverstobiodiversityconservationoftenoccuroutsideofthefootprintof theNationalParks,managementissuesareextendingbeyondthepark boundariesandbecomingmoresocio-economicinnature(Venteretal., 2008).ThecreationoftheGreaterLimpopotransfrontierconservationarea shiftedtheparkfrombeingsingleuseforwildlifetoamulti-usepark,sharing itslandwithcommunitiesandtheirlivestock.Thepark’scurrentstrategic adaptivemanagementaimstoincreaseunderstandingofcomplexecosystems andbroadersocietalneedsoflocalcommunities.Thisprocessisguidedby

settingappropriatethresholdsofpotentialconcern(TPC),asetofadaptive managementgoalsandendpointsthatdefineupperandlowerlevelsof acceptablechange,enablingmanagementtodeterminehowmuchasystem canbeallowedtofluctuatebeforeitbecomesaconcernandrequiresmanagementaction.AlthoughTPCsproveusefulforsimplemetricslikeinvasive plantsandriverflows,theyhaveprovenmorechallengingforcomplexsystemssuchasdiseasewheredriversandrespondersarenotalwaysknown (GaylardandFerreira,2011; Venteretal.,2008).

KrugerNationalPark’s2018–28managementplanincludesadisease managementprogrammeasasupportingobjectivetothehigher-level objectiveofbiodiversityconservation.Thisprogrammeacknowledges endemicwildlifediseaseswithintheparkasakeycomponentofbiodiversity yethighlightstheneedtopreventandmitigatethespreadofdiseaseatthe wildlife-livestock-humaninterfaceandlimittheintroductionorimpactof novelinfectiousdiseases(Spiesetal.,2018).

4.3Environmentaldriversofdiseasetransmission

4.3.1Spatialheterogeneityandthenorth/southdivide Topography,climate,geologyandtheassociatedsoilandvegetationpatterns canexertabottom-upcontrolonecosystems.Thecombinationofthese abioticfactorscaninfluencefirepatternsandanimalbehaviours,aswellas diseasedynamics(Venteretal.,2003).

KrugerNationalParklieswithinpartofthenorth-easternSouthAfrican lowveld,whichgenerallyhasplainsoflowtomoderatereliefwithsomelow mountainsandhills.Thegeologyoftheparkcanbecrudelydividedinto graniteplainsonthewestandbasaltplainsontheeast,separatedbya north-southstripofsedimentaryrock(Venteretal.,2003).Rainfallin theparkincreasesalonganorthtosouthgradientwithannualmeanrainfall of350mminthenortheastto750mminthesouthwest.Geologyandrainfall haveinfluencedthedifferenceinsoilandvegetationtypesbetweenthe northandthesouthofthepark.Thesouthgenerallyconsistsofdeeper andmorediversesoiltypeswithpredominantlyopencanopyacaciatree bushveldandsavannahwithawellwoodedareainthesoutheast.Incontrast, thenorthtendstohavelessdiverse,thinnersoilswithahighercalciumcontent.Vegetationisdominatedbymopanetreeswithrarelowveldriverine forestoccurringalongtheriversinthenortheastandsandveldvegetation typeinthenorthwest(Gertenbach,1983; Spiesetal.,2018).Thenorthern mostsectionoftheparkisuniqueasitcontainsavariedassemblageofrock formationswithassociatedsoilandvegetationtypes.Italsocontainstheonly

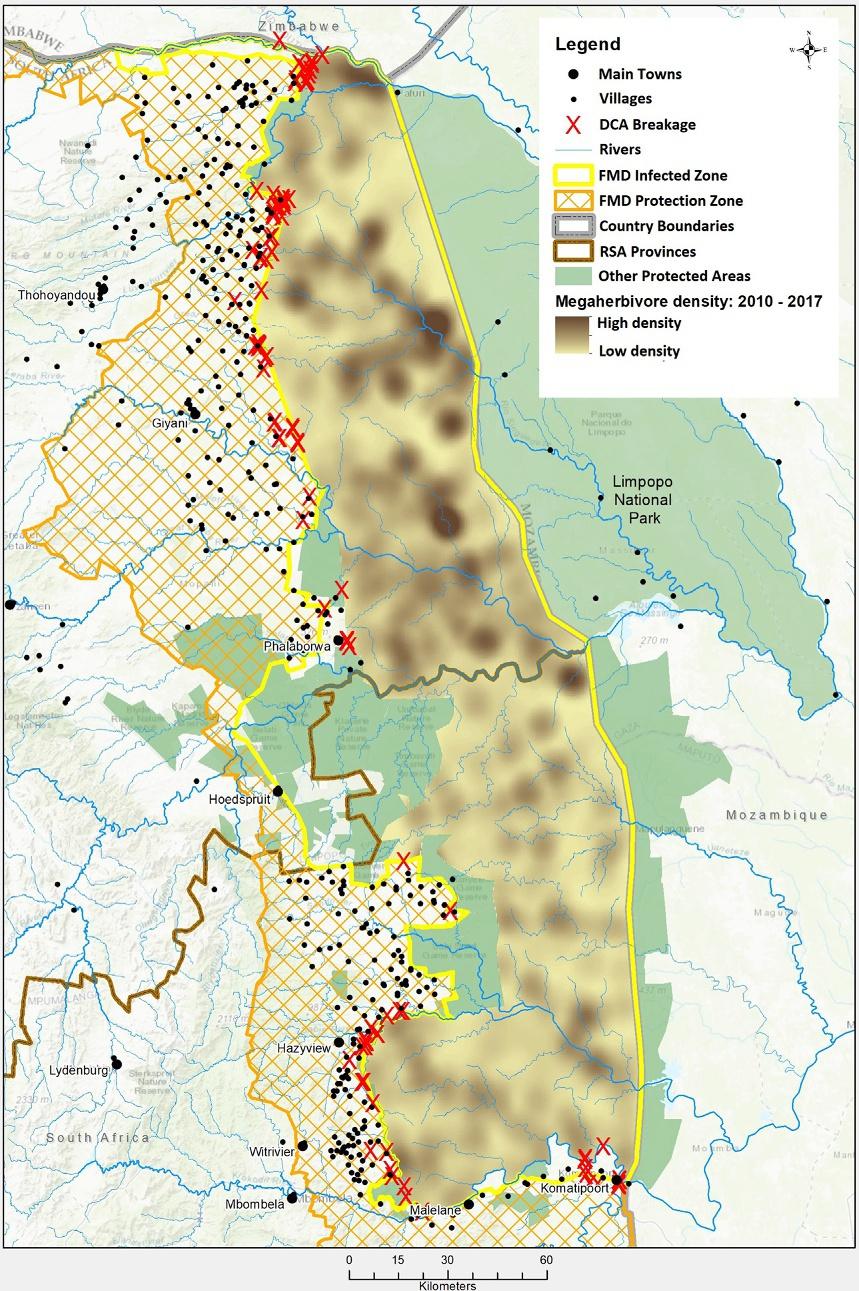

truefloodplaininKruger(Venteretal.,2003).Formanagementpurposes, KrugerNationalParkhasbeenpartitionedinto35landscapesdepending ongeomorphology,vegetation,soil,climatetypesandassociatedfauna (Gertenbach,1983; Venteretal.,2003).Asocial-economicgradientexists alongthenorthernandsouthernboundariesofthepark.Denseperi-urban tourbandevelopmentsliealongthesouthwesternborder,includingsugarcaneplantations,forestryandthenearbycityofMbombela(previously knownasNelspruit; Fig.2).Thecentralandnorth-westernboundaries arebufferedbyprivatenaturereservesandcommunitysubsistencefarming, andfurthernorthbecomesmoreruralwithlargeagriculturalareasandpoor villageswithlimitedeconomicopportunities(Spiesetal.,2018).Wildlife densitiesalsodifferacrosstheparkwithmegaherbivore(elephantand buffalo)densitieshigherinthenorththanthesouth(Fig.2).

Thisecologicalheterogeneitywithintheparkcancreatespatialheterogeneityindiseasedynamics.AparkwidesurveyofRVFinbuffaloin1998 showedsignificantlyhigherseroprevalenceofbuffaloherdsinthesouthand centralregionsoftheparkcomparedtothenorth(Beechleretal.,2015a). Thiswasattributedtolowerrainfallanddifferentvegetationinthenorth leadingtolesssuitablebreedinghabitatsformosquitovectors(Beechler etal.,2015a).Brucellosisprevalenceinbuffalowassignificantlyassociated withparksectionandsoiltype(Gorsichetal.,2015).Buffalocapturedon theresourcepoorgraniticsoilsweretwiceaslikelytobeseropositivefor brucellosiscomparedtothoseontheresourcerichbasalticsoils(Gorsich etal.,2015).Moreover,buffaloongraniticsoilshadhigherprevalencein thesouthernsectionoftheparkcomparedtothecentralsection(Gorsich etal.,2015).Thiswasattributedtonutrientpoorvegetationinthesouthwesterngraniticsoilsandgenerallowerbodyconditionofbuffalointhe southofKrugerNationalPark(Caronetal.,2003; Gorsichetal.,2015). Theeffectofbrucellosisinfectionwasalsodependantontheseasonalheterogeneityofthepark,brucellosisinfectionwassignificantlyassociatedwith lowerbodyconditionbutonlyinthedryseason(Gorsichetal.,2015). Knowledgeofthisheterogeneityofdifferentdiseasedynamicsandhow thelandscapeandenvironmentaffectthisisofgreatimportanceandcanhelp targetmonitoringandmanagementofdiseaseswithinthepark.

4.3.2Climatechangeandsevereweatherevents

Africaisconsideredoneofthemostvulnerableareastoglobalclimate change(Serdecznyetal.,2017).Averagetemperaturereadingsfromthe SkukuzaweatherstationinKrugerNationalParkhaveshowna2 °C

Fig.2 Megaherbivore(Africanbuffaloandelephant)densityacrossKrugerNational Parkandfencebreakages(redcross)fromdamagecausinganimals(DCAs).Elephant causemostbreakagesenablingdiseasedbuffalotoescape.Footandmouth(FMD)veterinarycontrolzonesandnearbyvillagesarealsoshown. MapproducedbytheSkukuza GISOffice.