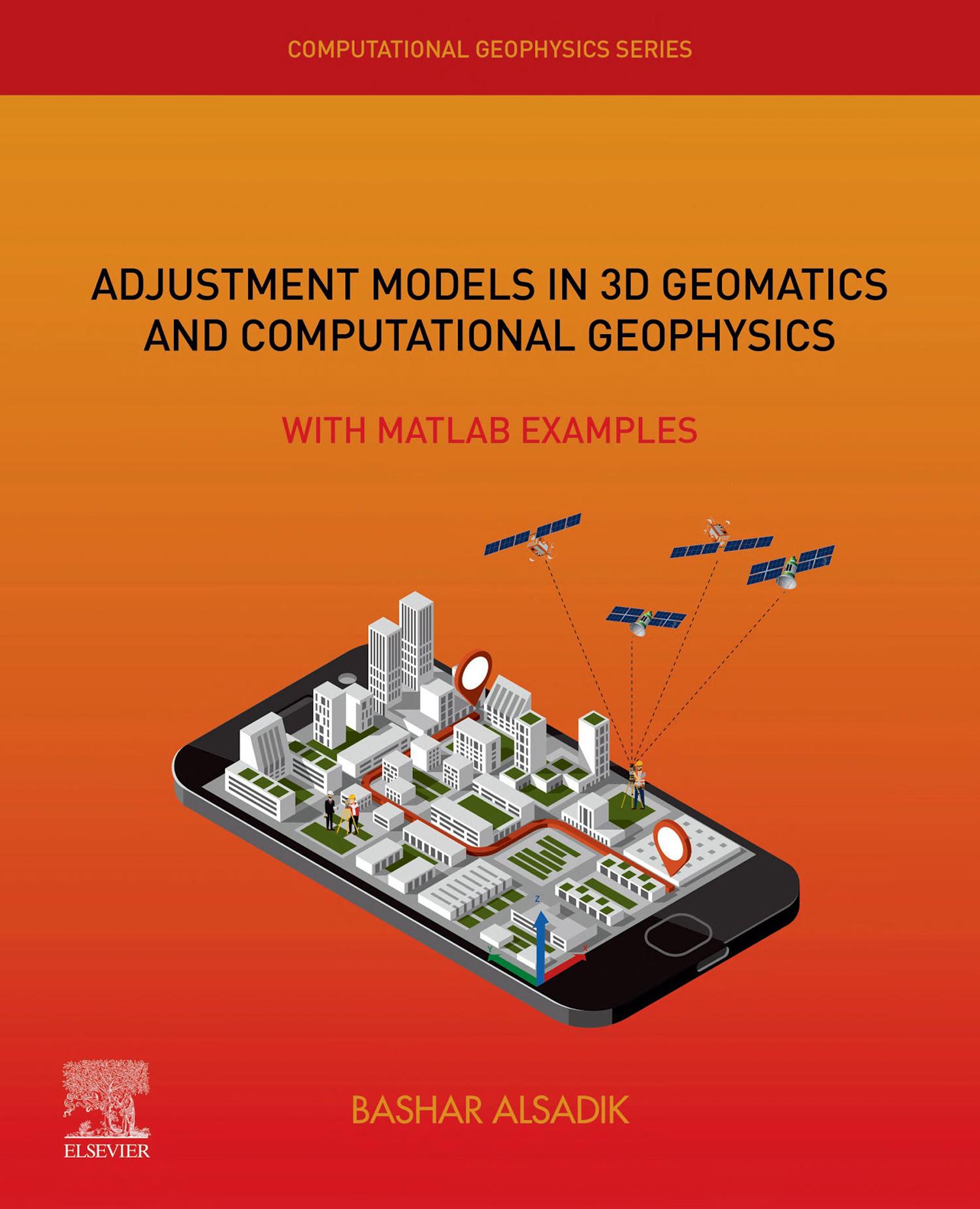

GEOPHYSICS WithMATLABExamples

VOLUME 4

BASHAR

ALSADIK

FacultymemberatBaghdadUniversity–CollegeofEngineering–Iraq(1999–2014) ResearchassistantatTwenteUniversity–ITCfaculty–TheNetherlands(2010–2014) MemberoftheInternationalSocietyforPhotogrammetryandRemoteSensingISPRS

Elsevier

Radarweg29,POBox211,1000AEAmsterdam,Netherlands

TheBoulevard,LangfordLane,Kidlington,OxfordOX51GB,UnitedKingdom 50HampshireStreet,5thFloor,Cambridge,MA02139,UnitedStates

# 2019ElsevierInc.Allrightsreserved.

Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproducedortransmittedinanyformorbyanymeans,electronicor mechanical,includingphotocopying,recording,oranyinformationstorageandretrievalsystem,without permissioninwritingfromthepublisher.Detailsonhowtoseekpermission,furtherinformationaboutthe Publisher’spermissionspoliciesandourarrangementswithorganizationssuchastheCopyrightClearance CenterandtheCopyrightLicensingAgency,canbefoundatourwebsite: www.elsevier.com/permissions

ThisbookandtheindividualcontributionscontainedinitareprotectedundercopyrightbythePublisher (otherthanasmaybenotedherein).

Notices

Knowledgeandbestpracticeinthisfieldareconstantlychanging.Asnewresearchandexperiencebroadenour understanding,changesinresearchmethods,professionalpractices,ormedicaltreatmentmaybecomenecessary.

Practitionersandresearchersmustalwaysrelyontheirownexperienceandknowledgeinevaluatingandusing anyinformation,methods,compounds,orexperimentsdescribedherein.Inusingsuchinformationormethods theyshouldbemindfuloftheirownsafetyandthesafetyofothers,includingpartiesforwhomtheyhavea professionalresponsibility.

Tothefullestextentofthelaw,neitherthePublishernortheauthors,contributors,oreditors,assumeany liabilityforanyinjuryand/ordamagetopersonsorpropertyasamatterofproductsliability,negligenceor otherwise,orfromanyuseoroperationofanymethods,products,instructions,orideascontainedinthe materialherein.

LibraryofCongressCataloging-in-PublicationData

AcatalogrecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheLibraryofCongress

BritishLibraryCataloguing-in-PublicationData

AcataloguerecordforthisbookisavailablefromtheBritishLibrary

ISBN:978-0-12-817588-0

ForinformationonallElsevierpublications visitourwebsiteat https://www.elsevier.com/books-and-journals

Publisher: CandiceJanco

AcquisitionsEditor: AmyShapiro

Editorialprojectmanager: HilaryCarr

Productionprojectmanager: PaulPrasadChandramohan

CoverDesigner: GregHarris

TypesetbySPiGlobal,India

Preface

Therapiddevelopmentindifferentareas ofscienceandtechnologyinthelastdecades transferredengineeringapplicationsintoa newerawherethemajorareasofdesignation,analysis,prototyping,andimplementationarebeingappliedincomputerizedor automatedways.Thismeansthatalarge numberofcomputationsthatwasdifficult orcomputationallyexpensivetoperformin thepastaretodayeasilyhandledandsignificantlyautomatedorprogrammed.

Animportantdivisionofengineering, namely,traditionalsurveyingand/orgeodeticengineering,ispositivelyaffectedby thedevelopmentsoradventsofsatellitenavigation,digitalmapping,informationtechnology,robotics,remotesensing,computer vision,sensorsfusion,andotherfieldsrelated toGeo-wiseapplications.

Accordingly:

– Paper-basedcartographicplottinghas changedtosoft-copyordigitalmapping, webmapping,andgeographic informationsystems(GIS).

– Traditionalphotogrammetryisaffected bycomputerormachinevisiontechniques anddigitalimageprocessingadvents. Further,satelliteremotesensingwith differentimageresolutionsand/or spectralarereplacingtraditionalaerial photographyinmanyapplications.

– Fieldsurveyingequipmentare developingawayfromtraditional theodolitesandelectronicdistance measurements(EDM)towardrobotictotal stationsandglobalnavigationsatellite

system(GNSS)-basedpositioning,asan example.

Hence,theterminologyofsurveyingis changinginmanyeducational,academic, andgovernmentalinstitutionstogeomatics, geoinfomatics,orgeospatialengineering, wherethree-dimensionalobservationsare moreapplied.

Consequently,theauthorcametotheidea ofwritingthisbookthatfocusesontheadjustmentof3Dgeomaticalobservations, whichinspirestraditionaltechniquesand putstheminamodernformsupportedby solvedexamples.Further,thebookisfocusedonpresentingboththeoreticaland practicalcontexttoensureaclearunderstandingofadjustmentcomputationstopic tothereaders.Manynumericalexamplesas mentionedareintroducedandsupportedby MATLABcodestofullyunderstandthetopics. Theauthorshouldmentionthatheisnot aprofessionalprogrammer,andhedeveloped thecodesmainlyforeducationalpurposes. Thebookisintendedforstudents,lecturers, andresearchersinthefieldofgeomaticsand itsdivisions.Thereaderscanfindthefull listofthecodeexamplespublishedinthislink https://nl.mathworks.com/matlabcentral/ fileexchange/70550-adjustment-models-in3d-geomatics.

Thestructureofthebookisdesignedin12 chapterstocoveressentialpreliminaryand advancedadjustmenttopics. Chapter1 introducesstatisticaldefinitions,concepts,and derivations.Themostimportantmethodof theadjustmentusingtheleastsquares

principleanditsmathematicalderivationis alsointroduced.Then,in Chapter2,error propagationtechniqueispresentedandthe variance-covariancematrixofobservations andunknownsisdescribed.Similarly,the preanalysisprocedureispresented.In Chapter3,theadjustmentusingtheconditionequationsandtheobservationequations isintroducedand,attheend,theconceptof thehomogeneousleastsquaresmethodis presented.Forabetterunderstanding,differentadjustmentmodelsareshownin Chapter4 suchasintersectionandresection eitherin2Dor3Dusingobserveddistances, angles,azimuths,differenceinheights,or computationsfromimages.Attheendof Chapter4,animportantcomputationalgeophysicsapplicationisshownofearthquake locationdetermination.Thegeneraladjustmentapproachispresentedin Chapter5 whenthereismorethanoneobservationin themathematicalmodelrelatedtoseveralunknowns.Theimportanttopicofadjustment withconstraintsisintroducedin Chapter6. Threemaintopicsarepresentedinthischapter:adjustmentwithconstraints,adjustment withadditionalparameters,andtheadjustmentwithinnerconstraints(freenets).

Moreadvancedtopicsarepresentedinthe secondhalfofthebook,suchastheunified approachofleastsquaresadjustmentof Chapter7.Thisisanadvancedadjustment techniquewheretheunknownshaveuncertaintiesandarethenprocessedasobservationsinthemodel.

Chapters8and9 presentmorerelatedapplicationsingeomatics,namelythetopicof fitting3Dgeometricprimitivesandthe3D transformationcomputationsrespectively. Thenthebookcontinuestogiveintroduction tootheradvancedtopicssuchastheKalman filterin Chapter10 andthenonlinearleast squaresusingLevenberg-Marquardtin Chapter11.Finally,inthe Chapter12 of thebook,thedetection,identification,and adaptation(DIA)ofthepostadjustment techniquesisintroduced.Thechapterpresentstheblunderdetectionmethodsof datasnooping,robustestimation,andthe randomsampleconsensus(RANSAC).In thebook’sAppendix,aMATLABcodeis givenfortheadjustmentofhorizontal geodeticnetworks.

BasharAlsadik TheNetherlands

StatisticalIntroduction

1.1INTRODUCTION

Ingeomatics,differentkindsofmeasurements(termedas observations inthebook)are applied.Theimperfectionsininstrumentation,weatherconditions,andlimitationsofthe operator0 sskillsproducefieldobservationsthatencompassdifferentkindsoferrors.Accordingly,understandingtheadjustmentofobservationsandtheoryoferrorsareessentialto processandsolvegeomaticalproblems.Becauseweneedconfidenceinappliedengineering orascientificproject,statisticalmeasuresofaccuracy,precision,andreliabilityshouldbe computedand/orstandardized.Itshouldbenotedthatfulfillingtherequiredaccuracystandardswilltakemoretimetoimplement,moreprofessionallabor,advancedinstrumentation, andmorecomputingpower.

Togivereallifeexamplesabouttheimportanceofthischapter’sperspectiveandtopics relatedtoadjustmentofobservations,welisttwoexamplesin

Fig.1.1.Thefirstexample, shownin Fig.1.1A,isaboutanengineeringconstructionproject.Severalquestionscome tomind:Whichendofthebridgeisthecorrectlypositioned/alignedone?Howaccurateit is?Andwhaterrortypemightbeoccurredinthecalculationsandexecutions?

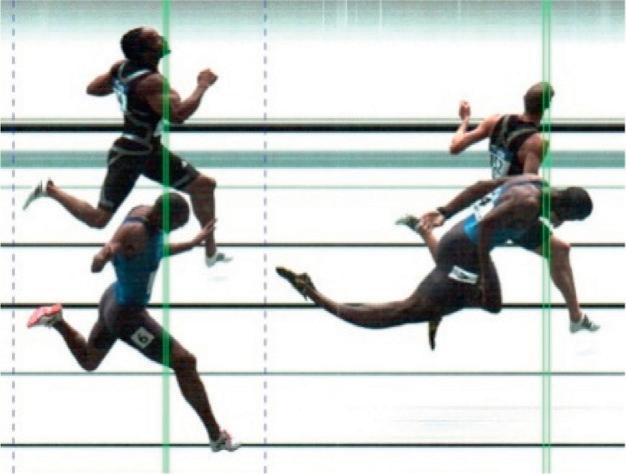

Thesecondexample,shownin Fig.1.1B,showsracingathletesatthefinishlinewherethe timedifferencebetweenthemiswithinfractionsofasecond.Sowhichofthetwocompetitors isthewinner?Howaccurateisthismeasuringimagesystem?Isthecameracalibratedand wellpositioned?

FIG.1.1 (A)Whichendofthebridgeisthecorrectlyalignedone?(B)Whichathleteisthegoldmedalwinner?

Allofthesequestionsaskedof Fig.1.1 canbeansweredwhenweunderstanddifferentconceptsandindicesinadjustmentofobservationsandtheoryoferrorssuchas:accuracy,precision,reliability,calibration,standarddeviation,weightedmean,residualerror,most probablevalue(MPV),redundancy,etc.

1.2STATISTICALDEFINITIONSANDTERMINOLOGIES

• Errors arethedifferencesbetweenobservedvaluesandtheirtruevalues.Anerroriswhat causesvaluestodifferwhenameasurementisrepeated,andnoneoftheresultscanbe preferredovertheothers.Althoughitisnotpossibletoentirelyeliminateerrorina measurement,itcanbecontrolledandcharacterized.Wesummarizedtheterminologies relatedtoerrorsasfollows:

• Grosserrors: Thesearelargeerrors(blunders,mistakes,oroutliers)thatcanbeavoidedin theobservations;however,theydon0 tfollowamathematicalorphysicalmodelandmay belargeorsmall,positiveornegative.Withdevelopmentsininstrumentationand automatedprocedures,themainsourceofgrosserrorsishuman-related,forexample, recordingandreadingerrors,orobservingadifferenttargetthantheintendedone. Carefulreadingandrecordingofthedatacansignificantlyreducegrosserrors.Itshouldbe notedthatsomereferencesdon0 tcountmistakesasanerrortype[1].

• Systematicerrors

Systematicerrors(orbiaswhenhavingmanyobservations)occurwhenfollowing somephysicalmodelsandthereforecanbechecked.Systematicerrorsareeitherpositiveor negative;usingpropermeasuringprocedurescaneliminatesomeofthem,whereas somearecorrectedbyusingmathematicalmethods.Systematicerrorsourcesare recognizableandcanbereducedtoagreatextentbycarefuldesignationoftheobservation systemandtheselectionofitscomponents.Inpractice,theprocessof calibration of instruments,suchascamerasinphotogrammetry,istodetectandremovesystematic errors.

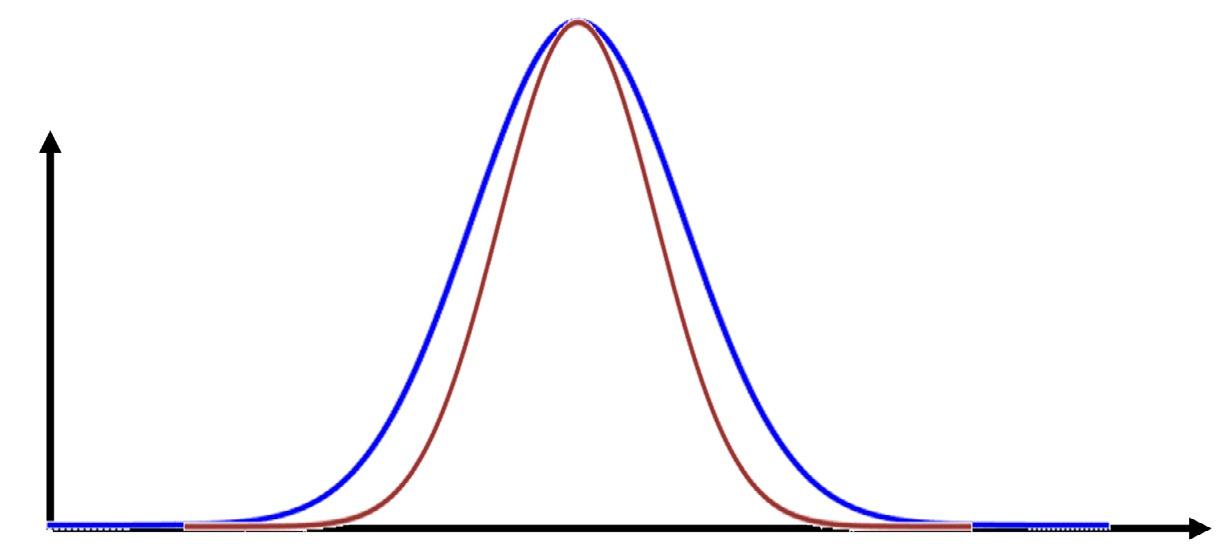

• Fig.1.2 illustratesasystematicerror-freeobservation(redcurve)biasedinacertain directionandamount(thebluecurve).

(A)(B)

Systematicerror(bias)illustration.

• Randomerrors

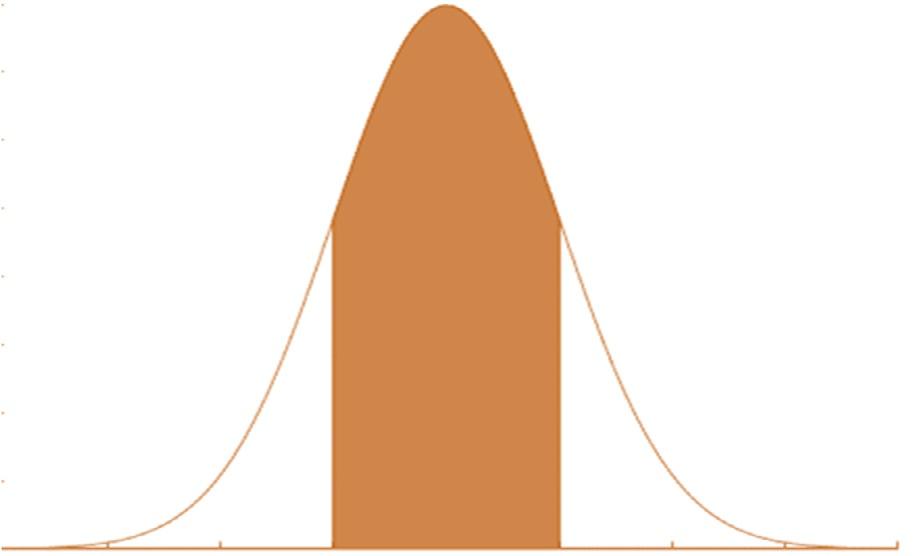

Randomoraccidentalerrorsareunavoidableerrorsthatrepresentresiduals afterremovingallothertypesoferrors.Thistypeoferroroccursinobservationsbecause oflimitationsinthemeasuringinstrumentsorduetolimitationsrelatedtotheoperator, amongotheraffectingundeterminedfactors.Itshouldbenotedthatrandomerrors canbepositiveornegative,andtheydon0 tfollowaphysicalmodel.Therefore,theyare processedstatisticallyusingtheprobabilitytheorembecausethemajorityfollowsnormal distribution.Inrepetitiveobservations,theaverageormeancanbeusedastheMPV. Asshownin Fig.1.3,greaterrandomerrorscauseagreaterdispersionofnormally distributedobservationsaroundthemean.Thedispersionismeasuredbythestandard deviationsatacertainprobabilityaswillbeshowninEq. (1.6).

Observationshavinganormalprobabilitydistribution.(A)Withrandomerrors.(B)Withoutrandom errors.

• Uncertainty

Allobservationshaveuncertainties,whichisarangeofvaluesinwhichthetrueobservationcouldlie.Anuncertaintyestimateshouldaddressbothsystematicandrandomerrors,andthereforeisconsideredthemostpropermeasureofexpressingaccuracy. However,inmanygeomaticsproblems,thesystematicerrorisdisregarded,andonlyrandomerrorisincludedintheuncertaintyobservation.Whenonlyrandomerroriscounted intheuncertaintyevaluation,itisanexpressionoftheprecisionoftheobservation.

FIG.1.2

The normal distribution of X without random errors

The normal distribution of X with random errors

FIG.1.3

• AccuracyandPrecision

Accuracy istheclosenessbetweenanobservedvalueanditstruevalue(trueness).When theobservationsfollownormalprobabilitydistribution,accuracycanbeillustratedas shownin Fig.1.4.Therefore,removingsystematicerrorsimprovesaccuracy.

Precision istheclosenessbetweenindependentobservationsofaquantityunderthesame conditions(Fig.1.4).Itisameasureofhowwellavalueisobservedwithoutreferencetoa theoreticalortruevalue.Thenumberofdivisionsonthescaleofthemeasuringdevicegenerallyaffectstheconsistencyofrepeatedobservationsand,therefore,theprecision.Because precisionisnotbasedonatruevalue,thereisnobiasorsystematicerrorinthevalue,but ratheritdependssolelyonthedistributionofrandomerrors.Theprecisionofameasurementisusuallyindicatedbytheuncertaintyorfractionalrelativeuncertaintyofavalue. Anotherusefulillustrationabouttheconceptofprecisionandaccuracyisshownin Fig.1.5 usinganarcherytargetfieldinthreecases.

FIG.1.4 Accuracyandprecision.

FIG.1.5 Relationbetweenaccuracyandprecision.

Therefore:

– Reducingsystematicerrorsimprovesaccuracy.

– Reducingrandomerrorsimprovesprecision.

Anincorrecttermissayingthatyoucanreducerandomerrorsbychoosing amoreaccurate measuringdevice.Thecorrecttermistosay amoreprecisemeasuringdevice.Forexample,smaller scaledivisionsmeanasmallerspread,whichleadstohigherprecisionwhereasamoreaccuratedevicewouldbeonethatreadstruevalues.

• Reliability

Reliabilityisanimportantterminadjustmentcomputations.Reliabilityreferstothedegreeofconsistency,orreproducibility,ofobservations.Inotherwords,reliabilitydefines byhowmuchtheadjustedobservationsmustagreewithreality.Itshouldbenotedthat errorsinobservationscanresultinpoorreliability. Fig.1.6 showsexamplesofreliable andunreliableobservations.ThethreelinesAB,CD,andEFintersectatpointP;however, theleftplotshowslessreliableobservationswhereastherightplotshowsreliableobservationswherethethreelinesintersectalmostexactlyatP.

(Left)lessreliableobservations;(right)reliableobservations.

• Residualerror

Residualerror v meansthedifferencebetweenthetruevalueanditsobservedvalue. However,becausethetruevalueisimpossibletoreach,itisstatisticallycompensated bythe MPV.Therefore:

Itshouldbenotedthatthe MPV valueofrepetitiveobservationsisthearithmeticmean, whereasforotherobservations,itistheoptimalvaluethatofferstheminimalofthesquared residualerrors.Thisconceptwillbeexplainedintheleastsquaresprincipleof Section1.7.Itis importanttonotethatthe MPV intheconceptoftheleastsquaresrepresentstheadjusted valuesofobservations.Fornonlineargeomaticalproblems,theadjustedvaluesarecomputed byrunningthesolutionwithinitialvalues.Accordingly:

FIG.1.6

1.3STATISTICALINDEXES

• Arithmeticmean x:whenobservingaquantity x for n timesunderthesameconditions,the mean x iscomputedasfollows:

• Variance σ 2:thetheoreticalmeanofthesquaredresidualerrorsthatcanbecomputedas follows:

Thedenominator n 1iscalledthe redundancyr orthe degreeoffreedom.Theminimum observationsweneedtodeterminethevarianceisonly1value,whichistermedas no;accordingly,therestoftheobservationsareredundant,and r canbeformulatedas:

• Standarddeviation σ :thesquarerootofthevariancethatexpressesbyhowmuchthe observationsdifferfromthe MPV orthemeanvalue.Further,itisameasureofhowspread outtheobservationsare.Therefore,standarddeviationisanexpressionofprecision computedas:

Whenthereferencevaluesareavailable,thestandarddeviationistermedasthe RootMean SquaredError (RMSE),whichindicatesbyhowmuchtheobservedorderivedquantitiesdeviatefromthereference(true)values.

• Standarderror σx :representsthestandarddeviationofthemean,whichiscomputedas:

EXAMPLE1.1

Given

AbaselineABisobservedinmeters10timesasfollows:

Required

26.34226.34926.35126.34526.348

26.35026.34826.35226.34526.348

Findthe MPV,thestandarddeviation,andstandarderroroflineABtothenearestmm.

Solution

The MPV forrepetitiveobservationsisthemean:

Thestandarddeviationiscomputedas:

Thestandarderroriscomputedas:

Then

1.4NORMALDISTRIBUTIONCURVE

Inliteraturerelatedtogeomatics,itispresentedthatallobservationstakenbysurveyors, suchasobserveddistancesandangles,orobservationsappliedbyphotogrammetristsand geodesistscomplywithorfollowprobabilitylows.Further,randomerrorsthatexistinthe observationsarenormallydistributed(Example1.2).Accordingly,statisticaltechniques canbeappliedinpostprocessingandanalysisoftheobservations.

Thenormaldistributioncurveorthegaussiancurvecanbecalculatedandthenplotted usingthefollowingEq. (1.9).

where

y:thenormalprobability,

K ¼ nI σ 2π p , h2 ¼ 1 2σ 2 calledtheaccuracyindex,

v:theresidualerror,

σ :thestandarddeviation,

I:anyselectedintervaloftheresidualerrors, e:exponentialfunction.

EXAMPLE1.2

Given

Anangleisobserved50timesindegreesasillustratedin Table1.1:

TABLE1.1 MeasuredAngle

40.342937040.341490840.337339040.336326940.340057740.3441110

40.341491540.337323740.335234940.339877340.341659440.3419747

40.336662040.338515440.341211540.343357940.345241240.3384449

40.336543940.338117940.340168540.339742940.337749040.3466756 40.342422240.343478740.340189240.345627040.339416140.3384703

40.338226340.342224240.337428940.340199740.340215240.3411796

40.343206240.340539040.341966540.339315440.340931640.3441452

40.336849540.343576640.341385640.336439840.341194740.3443333

40.337197640.3395228

Required

– Computethe MPV oftheangleanditsstandarddeviation.

– Computeandplotthenormalprobabilitydistributioncurveofresidualerrors.

Solution

The MPV oftheangleissimplythearithmeticmean,therefore: MPV ¼ meanofangles ¼ 40.3404387degrees

whereasthestandardsdeviationiscomputedas:

Tocomputetheprobability y ofthenormaldistributioncurve,thefollowingelementsare computed:

Thecomputedresidualsaregroupedbetweentwomaximum/minimumlimitsof 22.4500 .Then, tohave20regularintervalsfortheplottingissue,intervalIiscomputedtobe2.24500 asillustratedin thefollowingMATLABcode.

Table1.2.illustratesthedetailsofthecomputationstorelatetheresidualerrorsinsecondstothe computedprobability y ofthenormaldistributioncurve.

TABLE1.2 ComputedProbabilityoftheMeasured Angle

22.45504.002.6113.600.33

20.20408.042.118.250.55

17.96322.561.675.310.86

15.72247.121.283.601.26

13.47181.440.942.561.78

11.22125.890.651.922.37

8.9880.640.421.523.00

6.7445.430.231.263.61

4.4920.160.101.114.10

2.245.020.031.034.42

0.000.000.001.004.55

2.245.020.031.034.42

4.4920.160.101.114.10

6.7445.430.231.263.61

8.9880.640.421.523.00

11.22125.890.651.922.37

13.47181.440.942.561.78

15.72247.121.283.601.26

17.96322.561.675.310.86

20.20408.042.118.250.55

22.45504.002.6113.600.33

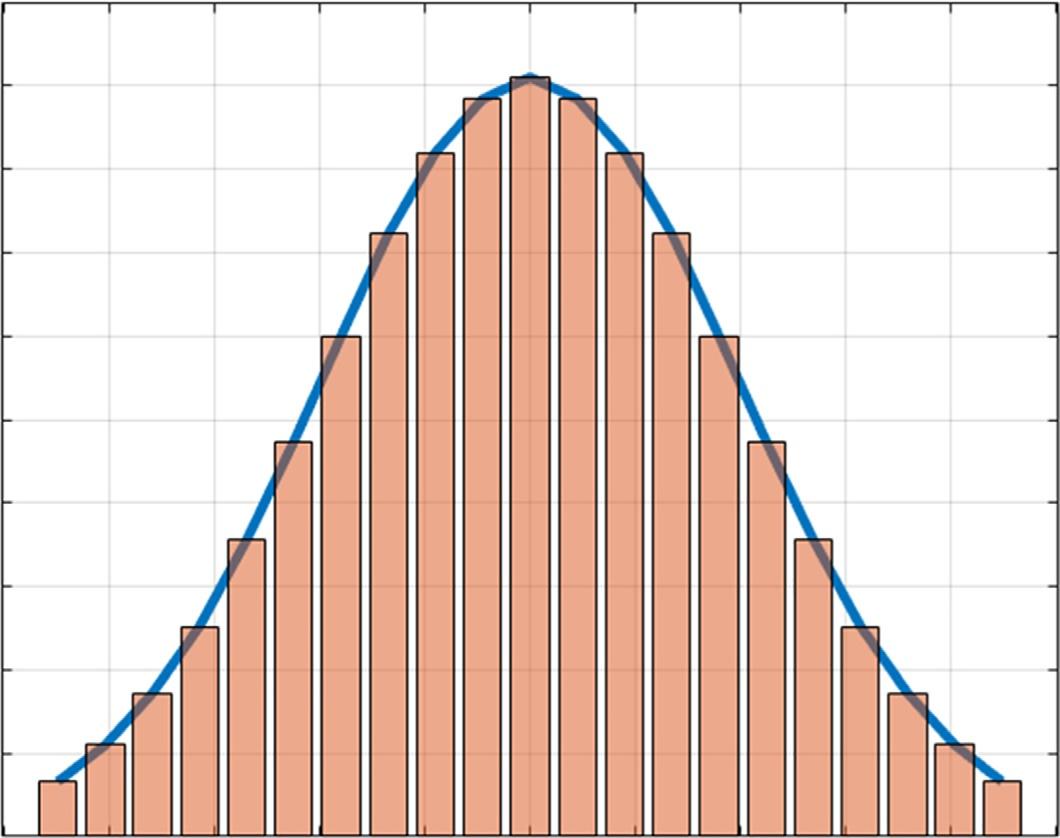

Thenthenormaldistributioncurveandhistogramcanbeplottedasshownin Fig.1.7

–25–20–15–10–50 Residualssec. Probability

FIG.1.7 Thenormaldistributionofresidualsinseconds.

MATLABcode

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%chapter1-example1.2%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% clc,clear,closeall

%%%%%%%%%%%%%createnormallydistributedobservedangles%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% ang=40.34+10*(randn(50,1)/3600);%%addingrandomnormalnoiseof10sec.

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% %%computeresiduals resid=3600*(ang-mean(ang)); Resid=unique(round(resid*100)/100); m=max(abs(Resid));%%makeequalintervals I=((2*m)/20)%20intervals%canbechangedbytheuser v=-m:I:m;v=round(v’*100)/100;%sampletheresidualsequallyinseconds v2=round(v.^2*100)/100;%squaredresiduals sigma=std(ang);sigma=sigma*3600;%standarddeviationinseconds n=size(ang,1);%totalnumberofobservations

k1=(n*I)/(sigma*sqrt(2*pi));%k1ofthenormalprobab.distribution k2=1/(2*sigma^2); %k2ofthenormalprobab.distribution

k2v2=round(k2*v2*100)/100; exp_k2v2=round(exp(k2v2)*100)/100; y=round((k1./exp_k2v2)*100)/100;%Yprobability

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% plot(v,y,’-’,’linewidth’,3);holdon;%plotthenormalcurve

xlabel(’RESIDUALSsec.’)

ylabel(’PROBABILITY’)

gridon

disp(’SUMMARIZEDCALCULATIONS’)

disp(’-————————————————————’)

T=table(v,v2,k2v2,exp_k2v2,y)

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% bar(v,y);alpha(.5);%plotthebars

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% 1.5CUMULATIVEDISTRIBUTIONFUNCTION

Asetofobservationsthatarenormallydistributedcanberepresentedasahistogramor distributioncurveasshowninExample1.2.

Ontheotherhand,the CumulativeDistributionFunction (CDF)showsthepercentageor relativecountofthesortedobservationvaluesovertheobservationsthemselves[2].This is,infact,theintegralofthenormaldistributionhistogram.

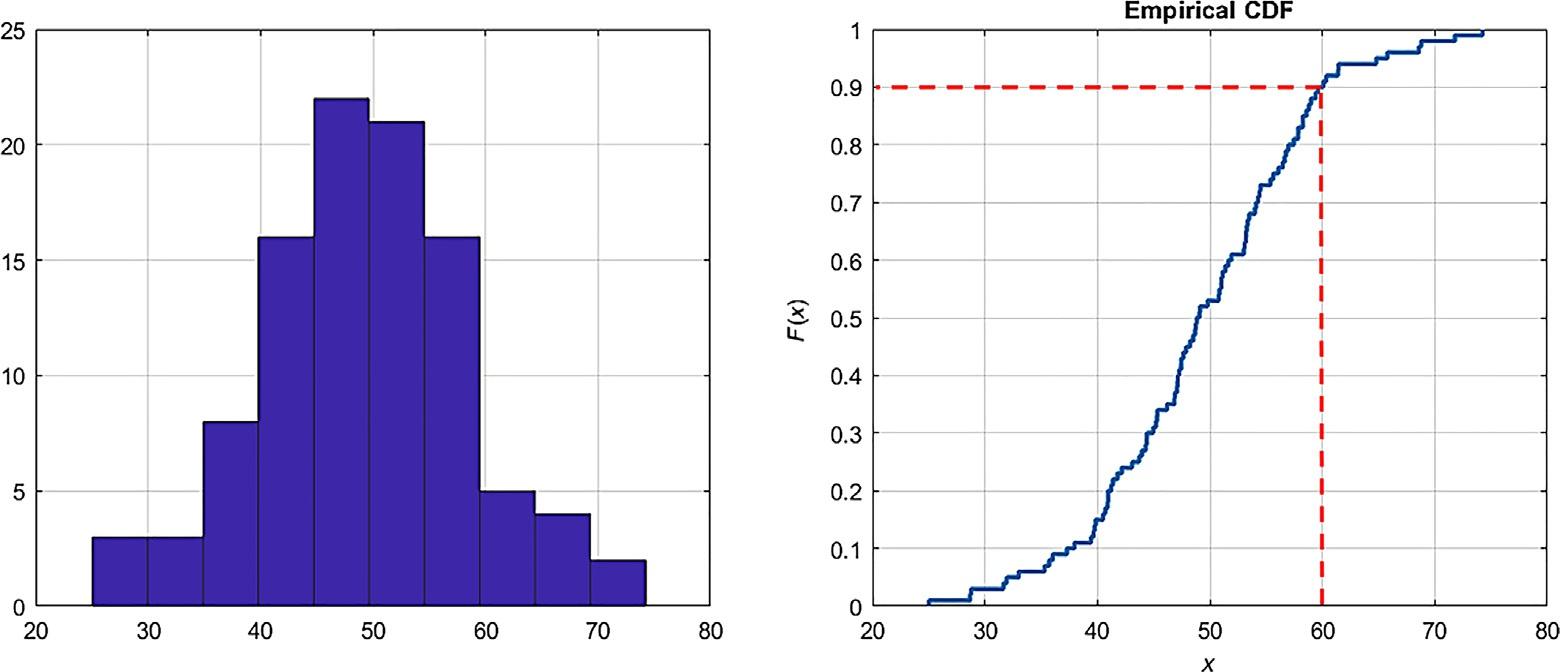

Let’sassumewehave100observationsofananglewherethemeanis50degreeswitha precisionof 10degrees.Wecanrepresenttheobservedvalueseitherinahistogramorin aCDFplotasfollows:

MATLABcode

%anglexbiasedrandomly

x=randn(100,1)*10+50 subplot(1,2,1) hist(x) subplot(1,2,2) cdfplot(x)

TheCDFplotin Fig.1.8Bexplainsthat90%oftheobservedanglesarelessthanorequalto 60degrees.Thispropertyiseasytointerpretevenforanonprofessional.Therefore,keyvalues suchasminimum,maximum,median,percentiles,etc.canbedirectlyreadfromthediagram. Accordingly,CDFisanefficientdescriptionforrandomvariableuncertaintyandisauseful toolforcomparingthedistributionofdifferentsetsofdata.

Let’sassumethatthreeobserversA,B,andCmeasuredthesameangle300timeseach.To comparetheskillofthethreeobserversinobservingtheangle,wecanusetheCDFplotas shownin Fig.1.9.

FIG.1.8 (A)Normaldistributionhistogram,(B)ThecorrespondingCDFplot.

FIG.1.9 TheCDFplotsoftheangleobservedbythreesurveyors.

MATLABcode clear;clc;closeall %anglebiasedrandomly A=randn(300,1)*10+50 hA=cdfplot(A);holdon set(hA(:,1),’Linewidth’,3); B=randn(300,1)*10+48

hB=cdfplot(B);holdon set(hB(:,1),’Linewidth’,3);

C=randn(300,1)*10+53

hC=cdfplot(C);holdon set(hC(:,1),’Linewidth’,3); lgd=legend(’observerA’,’observerB’,’observerC’,’fontsize’); lgd.FontSize=12; 1.6THEPROBABLEERRORANDLEVELSOFREJECTION

Theprobableerror Pe_50% isdefinedasthe50%orequalprobabilitythatatrueerrorcan arise.Inotherwords,50%probabilityoccurswhen j vi j > Pe_50% and50%when j vi j < Pe_50% as shownin Fig.1.10

FIG.1.10 The50%probableerror.

Foragroupofobservations,the50%probableerroristhemedianofresidualerrorsafter sortingtheminascendingordescendingorder,andthereforeitissometimestermedasthe medianabsolutedeviation (MAD)(Chapter12).However,byusingthisapproach,theprobable errorisnotsensitivetogrosserrorsasshowninthefollowingillustrationswheretheprobable erroris500 forbotherrorsetsdespitetheexistenceofgrosserrorof9400 .

Statistically,torelatetheprobableerror Pe_50% withthestandarddeviations,wecanapply thefollowingderivationbytheintegrationofthenormaldistributioncurveequationas:

Accordingly,theprobableerrorisevaluatedas:

where σ isthestandarddeviationand v isresidualerror. Applyingthesamederivationprocedure,wecancomputetheprobableerrorforanygiven standarddeviation.Hence,theprobableerrorfortherange σ isfoundtobe:

Therefore,theprobableerrorbetween σ and+ σ is68%ofthetotalareaofthenormal curveasshownin Fig.1.11.Asanillustration,whenalinelengthisobservedwithaprecision of 0.06m,itmeansthereisaprobabilityof68%thatthetrueerrorofobservationsisequalto orlessthan 0.06m.

point

Inflection point

FIG.1.11 Probableerrorintherangeof σ

Inthesamemanner,theprobableerroroftheintervals 2σ and 3σ arecomputedas showninEq. (1.13) and Fig.1.12.

FIG.1.12 Differentstandarddeviationslimitsofthenormaldistributioncurve.

Usually,thethresholdof3σ isusedforblenderdetection.Accordingly,residualsfallingat anyofthetwoendsofthenormalcurveinthe1%marginalareaoutsidethe99%ofconfidence areassumedtobeblunders. Table1.3 illustratesdifferentprobabilitypercentagesandtheassociatedstandarddeviationthresholdsthatcanbeadoptedforblunderdetectionorother postanalysisapplications.

TABLE1.3 TheRelationBetweenProbableErrorsandStandardDeviations

1.7PRINCIPLEOFLEASTSQUARESADJUSTMENT

NormaldistributioncurveasmentionedinEq. (1.9) is:

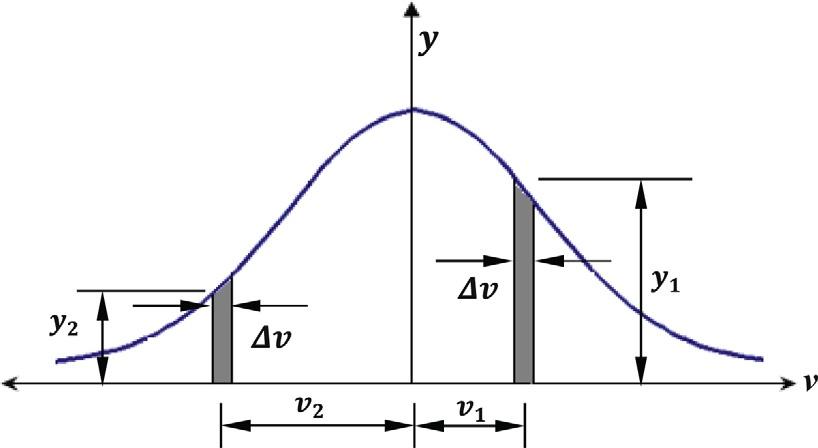

Theprobabilityofoccurrenceof vi ismathematicallyexpressedasarectangularslicearea underthenormaldistributioncurveasshownin Fig.1.13 withavalueof y1 Δ vi.Accordingly, theprobability Pvi ofhavingmoreresidualerrors v1, v2, … vn intheobservationsare:

FIG.1.13 Theprobabilityoferror vi occurrence.

Hence,theprobabilityoftheoccurrenceoftheerrorsaltogetheristhemultiplicationofthe involvedprobabilitiesas:

orsimplifiedas:

FIG.1.14 Theinverserelationbetween x and e x .

Theinverserelationbetweenexponentialfunction e x andvariable x isillustratedin Fig.1.14 wheretheminimalvalueof x isattainedwhen e x isatmaximum.

Accordingly,referringbacktoEq. (1.16),themaximumprobabilityvaluecanbeattained whenthesumofthesquarederrors(v1 2 + v2 2 + … + vn 2 )isatminimum,whichistheprincipleof leastsquaresadjustmentmethod.

orinmatrixformsas:

Insummary,the MPV (adjustedvalue)isthevaluewhenitssumofsquaredresidualerrors isatminimum.Theleastsquaresmethodisconsideredthemostcommonandrobust statistical-basedmethodofadjustmentofobservations.

EXAMPLE1.3

Provethatthearithmeticmean x representsthe MPV oftherepetitiveobservationsofaquantity xi usingtheprincipleofleastsquares.

Solution

The MPV intheconceptofleastsquaressatisfiestheminimumofsquaredresidualerrorsand, accordingly,ifaquantity xi isobserved n timesinthesameprecision,wecanputforththefollowing formulation:

where v ’ s aretheresidualerrors.BysubstitutingEq. (1.19) inEq. (1.17) ofleastsquaresmethod, wegetthefollowing:

Hence,deriving P v 2 withrespecttothemean x:

2

Aftersimplification,wegetthefollowing:

or

Then

1.8WEIGHTEDOBSERVATIONS

Inpractice,theobservationsarenotacquiredinthesameprecisionbecauseofdifferent observers,instruments,dates,dissimilarquantities,etc.

Therefore,thedifferenceinweights w shouldbeconsideredtogiverealisticadjustment results.Whenevertherequiredprecisionishigher,theobservationweightishigher.Onthis basis:

•Theweightisinverselyproportionaltostandarddeviationsofobservationsas:

•Theweightisinverselyproportionaltoobservedlength(asinlevelingnetworks):

•Theweightisconverselyproportionaltothenumberofobservations n as:

TheleastsquaresprincipleofEq. (1.17) canbeupdatedbyconsideringtheweightsas:

Further,thearithmeticmean x withtheconsiderationofweightswillbecomputedas follows:

ThestandarddeviationoftheweightedmeanisalsoupdatedcomparedtoEq. (1.8) tothe followingform:

Tocomputethestandarddeviationforoneobservation xi thathasaweightof wi,weusethe followingequation:

It’sworthmentioningthatEqs. (1.27)and(1.28) canbeprovenbyapplyingthepropagation oferrorslawof Chapter2

EXAMPLE1.4

Given

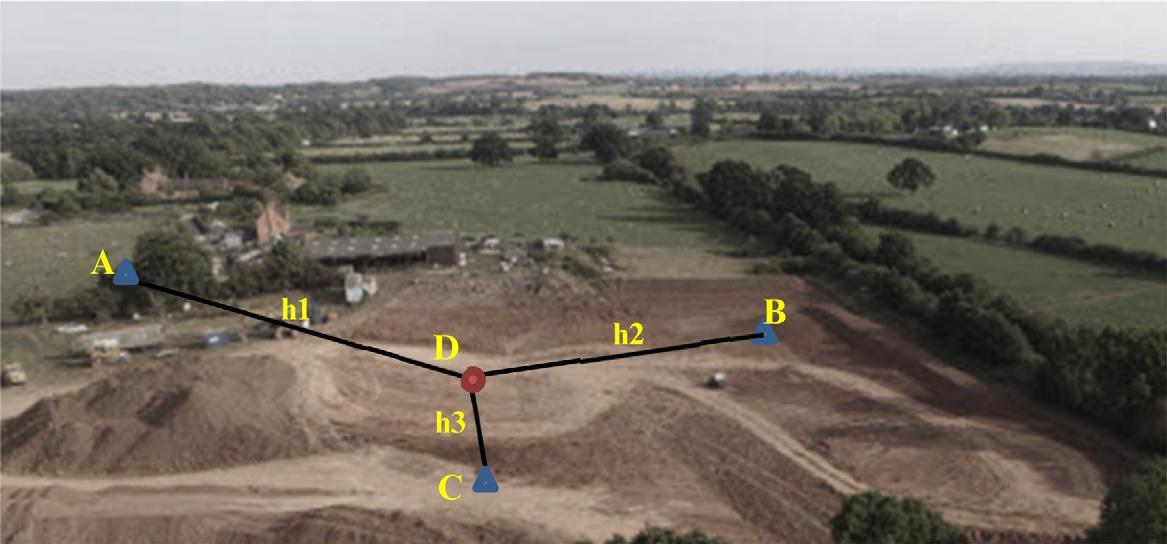

•Threeheightbenchmarks A, B,and C (Fig.1.15)as: HA ¼ 10.00m, HB ¼ 11.01m, HC ¼ 12.05m.

•Theobserveddifferenceinelevationsandlevelinglengthsaregivenas:

ΔHA ¼ 4 00m, LAD ¼ 1 10km

ΔHB ¼ 3:00m, LAD ¼ 0:75km

ΔHC ¼ 2 00m, LAD ¼ 0 50km

FIG.1.15 LevelingnetworkofExample1.4.

Required

ComputetheadjustedheightofstationDanditsstandarddeviationtothenearestcm.

Solution

Theweightedmeanrepresentsthe MPV oftheheightandaccordinglyweightscanbecomputed fortheobserveddifferencesinheightsfromthethreebenchmarksA,B,andCtotheunknownstationD.Asmentioned,weightsareinverselyproportionaltolevelinglinelengthsandthereforethe weightsarecomputedas:

TheestimatedheightofDfromeverylevelinglineisevaluatedasfollows:

Then

Tocomputethestandarddeviationoftheweightedmean,wefirstneedtocomputetheresiduals andthevarianceofunitweightasfollows:

Hence,thestandarddeviationoftheweightedmeaniscomputedas:

ThenthefinaladjustedheightofstationDis14.03m 16mm.

MATLABcode

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%chapter1-example1.4%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% %%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% clc,clear,closeall

%Given dha=4;dhb=3;dhc=2;%diff.inheight

La=1.1;Lb=.75;Lc=.5;%length

Ha=10;Hb=11.01;Hc=12.05;%absoluteheight

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

%weights

wa=1/La;wb=1/Lb;wc=1/Lc; %initialheightofD

Hd1=Ha+dha; Hd2=Hb+dhb; Hd3=Hc+dhc;

%weightedmean

M=round(100*(Hd1*wa+Hd2*wb+Hd3*wc)/(wa+wb+wc))/100; %thevarianceofunitweight va=(Hd1-M)*1000; vb=(Hd2-M)*1000; vc=(Hd3-M)*1000; sigma=(wa*va^2+wb*vb^2+wc*vc^2)/(3-1); %%%standarddeviationoftheweightedmean s_M=round(sqrt(sigma/(wa+wb+wc)))

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%% disp(’Result’) [num2str(M),’m’,char(177),num2str(s_M),’mm’]

%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%%

EXAMPLE1.5

Given

Threeangles A, B,and C areobservedinatriangulartraversebytwoobserversasfollows (Table1.4):

TABLE1.4 TheMeasuredAnglesbytheTwoObservers

Required

Computetheadjustedangles A, B,and C usingtheweightedmeancomputations.

Solution

Theanglesshouldbefirstadjustedtothegeometricconditionofthesumoftriangleanglesto180 asillustratedin Table1.5.