AbsoluteTime RiftsinEarlyModern BritishMetaphysics

EmilyThomas

GreatClarendonStreet,Oxford,OX26DP, UnitedKingdom

OxfordUniversityPressisadepartmentoftheUniversityofOxford. ItfurtherstheUniversity’sobjectiveofexcellenceinresearch,scholarship, andeducationbypublishingworldwide.Oxfordisaregisteredtrademarkof OxfordUniversityPressintheUKandincertainothercountries

©EmilyThomas2018

Themoralrightsoftheauthorhavebeenasserted

FirstEditionpublishedin2018

Impression:1

Allrightsreserved.Nopartofthispublicationmaybereproduced,storedin aretrievalsystem,ortransmitted,inanyformorbyanymeans,withoutthe priorpermissioninwritingofOxfordUniversityPress,orasexpresslypermitted bylaw,bylicenceorundertermsagreedwiththeappropriatereprographics rightsorganization.Enquiriesconcerningreproductionoutsidethescopeofthe aboveshouldbesenttotheRightsDepartment,OxfordUniversityPress,atthe addressabove

Youmustnotcirculatethisworkinanyotherform andyoumustimposethissameconditiononanyacquirer

PublishedintheUnitedStatesofAmericabyOxfordUniversityPress 198MadisonAvenue,NewYork,NY10016,UnitedStatesofAmerica

BritishLibraryCataloguinginPublicationData

Dataavailable

LibraryofCongressControlNumber:2017957995

ISBN978–0–19–880793–3

Printedandboundby

CPIGroup(UK)Ltd,Croydon,CR04YY

LinkstothirdpartywebsitesareprovidedbyOxfordingoodfaithand forinformationonly.Oxforddisclaimsanyresponsibilityforthematerials containedinanythirdpartywebsitereferencedinthiswork.

1.SceneSetting:Time,Philosophy,andSeventeenth-CenturyBritain13

4.SpaceandTimeinIsaacBarrow:AModalRelationistMetaphysic68

4.4.1The firstreading:Barrowlacksadeepermetaphysics

4.4.2Thesecondreading:identifyingspaceandtimewithGod

4.4.3Thethirdreading:spaceandtimeasunrealcontainers

4.5.3AnobjectiontoreadingBarrowasamodalrelationist

5.EarlyBritishReactionstoAbsolutism:1664to168793

6.Newton’ s DeGravitatione onGodandhisEmanativeEffects104

7.LockeasaSteadfastRelationistaboutTimeandSpace125

7.2SketchingLocke’sLifeandWorks

7.3Locke

s1676–1678journals

7.4ANewtonianInterlude:Locke,Newton,andthe1687 Principia

’s1690 Essay

7.5.1ReadingLocke’s1690 Essay asexplicitlyneutral

7.5.2UnderminingtheabsolutistreadingofLocke’s1690 Essay

7.5.3ReadingLocke’s1690 Essay asimplicitlyrelationist

8.LaterBritishReactionstoAbsolutism:1690–1704150

Abbreviations

ATDescartes,Rene(1964–76). OeuvresdeDescartes [VolsI–XII].Edited byAdam,C.&Tannery,P.Vrin/C.N.R.S.:Paris.

CLNicolson,MarjorieandSarahHutton(eds.)(1992). TheConway Letters:theCorrespondenceofAnne,ViscountessConway,HenryMore andtheirFriends,1642–1684.OxfordUniversityPress:NewYork.

CSM/KDescartes,Rene(1985–91). ThePhilosophicalWritingsofDescartes [VolumesI–III].TranslatedbyJohnCottingham,RobertStoothoff, DugaldMurdoch,and(forVolumeIII)AnthonyKenny.Cambridge UniversityPress:Cambridge.

HClarke,Samuel(1738). TheWorksofSamuelClarke.Editedby BenjaminHoadley.London.

NBarrow,Isaac(1859). TheTheologicalWorksofIsaacBarrow.Edited byAlexanderNapier.CambridgeUniversityPress:Cambridge.

PPMore,Henry(1878). TheCompletePoemsofDr.HenryMore.Edited byAlexanderB.Grosart.EdinburghUniversityPress:Edinburgh.

PWNewton,Isaac(2004). PhilosophicalWritings.EditedbyAndrew Janiak.CambridgeUniversityPress:Cambridge.

WBarrow,Isaac(1860). TheMathematicalWorksofIsaacBarrow.Edited byWilliamWhewell.CambridgeUniversityPress:Cambridge.

VClarke,Samuel(1998). ADemonstrationoftheBeingandAttributesof God,andotherwritings.EditedbyEzioVailati.CambridgeUniversity Press:Cambridge.

ChronologyofSelectedWritings

1644Descartes PrinciplesofPhilosophy

1644Gassendi DisquisitioMetaphysica

1647HenryMore PhilosophicalPoems

1648JanBaptistvanHelmont Ortusmedicinae

1651Hobbes Leviathan

1652IsaacBarrow CartesianaHypothesis

1653HenryMore AntidoteagainstAtheism

1654WalterCharleton PhysiologiaEpicuro-Gassendo-Charletoniana

1655Hobbes DeCorpore

1655HenryMore AntidoteagainstAtheism,secondedition 1655ThomasHobbes DeCorpore

1658Gassendi OperaOmnia

1659HenryMore ImmortalityoftheSoule

1664MargaretCavendish PhilosophicalLetters

1665SamuelParker TentaminaPhysico-TheologicadeDeo

c.1664–66IsaacBarrowdeliverstwosetsoflecturesatCambridge,laterpublishedas LectionesGeometricae and Mathematicae

1668HenryMore DivineDialogues

1670IsaacBarrow LectionesGeometricae

1671HenryMore EnchiridiumMetaphysicum

1671LockecomposesDraftsAandBof AnEssayConcerningHuman Understanding

1674NathanielFairfax ATreatiseoftheBulkandSelvedgeoftheWorld

1675RobertBoyle SomeConsiderationsabouttheReconcileablenessof ReasonandReligion

1676–78Lockemakesseveraljournalentriesontimeandspace

c.1677–79AnneConwaycomposes ThePrinciplesoftheMostAncientand ModernPhilosophy

1677Spinoza Ethics

1678RalphCudworth TheIntellectualSystemoftheUniverse 1679HenryMore EnchiridiumMetaphysicum,secondedition 1683JohnTurner DiscourseoftheDivineOmnipresence

1683IsaacBarrow LectionesMathematicae

c.1664–85Newtoncomposes DeGravitatione

1685LockecomposesDraftCof AnEssayConcerningHumanUnderstanding

1687Newton PhilosophiæNaturalisPrincipiaMathematica

1690Locke AnEssayConcerningHumanUnderstanding

1690AnneConway’ s ThePrinciplesoftheMostAncientandModern Philosophy isanonymouslypublishedinthecollection Opuscula philosophica

1694RichardBurthogge AnEssayuponReason,andtheNatureofSpirits

1696RichardBentley EightSermonspreach’dattheHonourableRobert Boyle’sLecture

1697JosephRaphson DeSpatioReali

1702JohnKeill Introductioadveramphysical

1704WilliamKing DeOrigineMali

1704Newton Opticks

1704JohnToland LetterstoSerena

1704SamuelClarkedelivershis firstsetofBoylelectures,laterpublished as ADemonstrationoftheBeingandAttributesofGod

1704WilliamWotton ALettertoEusebia

1705SamuelClarke ADemonstrationoftheBeingandAttributesofGod

1705GeorgeCheyne PhilosophicalPrinciplesofNaturalReligion

1706Newton’ s Opticks translatedintoLatin Optice

1710Berkeley PrinciplesofHumanKnowledge

1712SamuelClarke Scripture-doctrineoftheTrinity

1713Newton PhilosophiæNaturalisPrincipiaMathematica, second edition

1714JohnJackson ThreeLetterstoDr.SamuelClarke

1715GeorgeCheyne PhilosophicalPrinciplesofReligion,Naturaland Revealed.

1715–16LeibnizandSamuelClarkecorrespond

1717 ACollectionofPapers,WhichpassedbetweenthelateLearned Mr.LeibnizandDr.Clarke

1718Newton Opticks,secondedition

1718SamuelColliber AnImpartialInquiryintotheExistenceandNature ofGod

1726Newton PhilosophiæNaturalisPrincipiaMathematica, thirdedition

1728HenryPemberton AViewofSirI.Newton’sPhilosophy

1731EdmundLaw AnEssayontheOriginofEvil

1732JohnClarke DefenceofDr.Clarke’sDemonstrationoftheBeingand AttributesofGod

1732EdmundLaw AnEssayontheOriginofEvil,secondedition

1733JohnClarke SeconddefenceofDr.Clarke’sDemonstrationofthe BeingandAttributesofGod

1733JosephClarke Dr.Clarke’snotionsofspaceexamined

1733JohnClarke ThirddefenceofDr.Clarke’sDemonstrationoftheBeing andAttributesofGod

1733IsaacWatts PhilosophicalEssaysonVariousSubjects

1734JohnJackson TheExistenceandUnityofGod

1734JosephClarke AfartherexaminationofDr.Clarke’snotionsofspace

1734EdmundLaw AnEnquiryIntotheIdeasofSpace,Time,Immensity, andEternity&c

1735JohnJackson DefenceofTheExistenceandUnityofGod

1735SamuelColliber AnImpartialEnquiryIntotheExistenceandNature ofGod,thirdedition

1743CatharineCockburn RemarksUponsomeWritersonMorality

Acknowledgements

Metaphysicaltheoriesdonotspringfullyformedfromtheether,andnordo books.Anumberofpeopleandinstitutionshavehelpedmebringthisbookinto existence,andIofferthemmysincerethanks.

Overcupsofteaandglassesofwine,I’veespeciallyreceivedadvicefrom ChristophJedan,MartinLenz,AndreaSangiacomo,ErinWilson,MattDuncombe, HanThomasAdriaenssen,SanderdeBoer,BiancaBosman,SarahHutton,Robin LePoidevin,TimCrane,TomStoneham,JeremyDunham,JessLeech,OriBelkind, EricSchliesser,CarlaRitaPalmerino,GeoffGorham,EdSlowik,andAndrew Janiak.

IamalsogratefulforthethoughtfulworkofPeterMomtchiloff,andthatof theotherstaffatOxfordUniversityPress,throughoutthepublicationprocess. The firstpeopletoreadthismanuscriptasawholewereinfacttwoanonymous refereesforOxfordUniversityPress,andtheirdetailedcommentsonthat first(significantlyrougher)draftwerephenomenallyhelpful youknowwho youare.

Alongtheway,Ihavepresentedportionsofthisbookatavarietyofmeetings, seminars,andconferences,includingtalksattheGhentUniversity;Universityof Cambridge;UniversityofYork;UniversityofGroningen;KohnInstitute,Tel Aviv;DurhamUniversity;CUNY,NewYork;MacalesterCollege;Universityof Alaska,Anchorage;andLeidenUniversity.Inaddition,thebookbenefitedhugely fromafull-dayCHiPhibookinprogressworkshop,hostedin2015bythe UniversityofSheffield.Iamgratefultoeveryonewhoparticipatedinthesetalks. Thisbookformspartofalargerprojectthatwassupportedthroughoutbya NetherlandsResearchCouncil(NWO)Venigrant.Itwaswrittenandrevised acrossmytimeasapostdocattheUniversityofGroningen;asavisitingfellowat Christ’sCollege,Cambridge;andasalectureratDurhamUniversity.Iam extremelygratefultoallfouroftheseinstitutionsfortheirsupport.Appropriately,thisbook’scoverimageistakenfromanearlyeighteenth-centurymanuscriptauthoredbyaDutchman.

Twochaptersofthebookarepartlybasedonmaterialthathasalreadybeen published.Chapter2makesuseofmypaper ‘HenryMoreontheDevelopmentof AbsoluteTime’ (2015, StudiesintheHistoryandPhilosophyofScience 54:11–19). ChapterVIImakesuseofmypaper ‘Onthe “Evolution” ofLocke’sSpaceand TimeMetaphysics’ (2016, HistoryofPhilosophyofQuarterly 33:305–326) Iam

gratefultobothofthesejournalsforprovidingmewiththeappropriatepermissions,andtotheiranonymousrefereesforimprovingboththearticlesandthe requisitepartsofthemonograph.

Finally,I’dliketothankmywonderfulfamily,withaspecialmentiontoCT andFR.Thisbookisdedicatedtothem.

Introduction

MisshapenTime,copesmateofuglynight, Swiftsubtlepost,carrierofgrisliecare, Eaterofyouth,falseslavetofalsedelight, Basewatchofwoes,sin’spackhorse,vertuessnare; Thounursestall,andmurthrestallthatare.

WilliamShakespeare(1594,925–9)

AsShakespearesobaroquelydescribes,ourlivestakeplaceintime.Wearenursed init,andultimatelywedieinit.Philosophershavelongasked,What is time? Traditionally,ithasbeenansweredthattimeisaproductofthehumanmind,or themotionofcelestialbodies.Intheseventeenthcentury,anotheransweremerged: timeis ‘absolute’,somethingthatisindependentofhumanmindsandmaterial bodies.Absolutismcomesinmanyvarieties,andsomeabsolutistsconsideredtime tobeabarelyrealbeing,whilstothersidentifieditwithGod’seternity.

ThisstudyexploresthedevelopmentofabsolutetimeduringoneofBritain’ s richestandmostcreativemetaphysicalperiods,fromthe1640stothe1730s.It featuresaninterconnectedsetofmaincharacters HenryMore,WalterCharleton, IsaacBarrow,IsaacNewton,JohnLocke,SamuelClarke,andJohnJackson alongsidealargeandvariedsupportingcast,whosemetaphysicsareallreadin theirhistoricalcontextandgivenaplaceintheseventeenth-andeighteenthcenturydevelopmentofthoughtontime.AlthoughNewtonandLockeareby somedistancethemostfamiliarofthemaincast,itwillbeseenthattheyareparts ofamuchlargerBritishnetwork.

Thiswedgeofphilosophicalhistoryisinterestingforseveralreasons.Oneis thatabsolutismraisesmanyfurtherimportantphilosophicalquestions.What kindsofthingsexist?Howarethingscreated?Howdotheychange?IsGod presentintime?Ifso,how?Anotherreasonisthat,asweshallsee,themetaphysicsoftimetogetherwithspacewasoneof the definingmetaphysicalissuesof theperiod,discussedbyphilosophersofallstripes.Further,goingbeyondthe

history,workontimeinmetaphysicsandphilosophyofphysicscontinuesapace today,andseveralcurrentdebatesdrawdirectlyontheconceptualframeworks developedduringthisperiod.Finally,goingbeyondphilosophy,anotherreason absolutismisinterestingisthatfromthemid-eighteenthcenturyonwardsithas playedaroleinsubjectsasdiverseasart,geology,andphilosophicaltheology.

InwhatfollowsIwillplacethisstudyintheexistingliteratureandexplainitsscope, beforesettingoutitsgeneralthesesandgivinganoverviewofthecomingchapters.

ExistingLiterature

Theexistingliteraturedealingwithabsolutetimeorspaceintheearlymodern periodcanberoughlycategorizedintofourgroups.The firstcomprisesgeneral overviewsofthehistoryofphilosophyoftime,fromantiquityonwards.Asone wouldexpect,theseoverviewsareextremelyselective,andtheyusuallyrestrict themselvestorelativelybriefcommentsonsomepickoftheearlymodern philosophicalgiants:Descartes,Hobbes,Spinoza,Locke,Newton,orLeibniz.

Togivearelativelyrecentexample,AdrianBardon’s2013 ABriefHistoryof thePhilosophyofTime runsfromthepre-Socraticstothepresentday,andselects asmallgroupofearlymoderntimetheorists,includingLocke,Newton,and Leibniz.1 Incontrast,thepresentstudydealswithamuchlargernumberof thinkers,manyofwhomarenotwellknown.

Thesecondgroupliesattheotherextreme:focused,specialistliterature dealingwiththeworkofjustoneearlymodernthinker,includingtheirviews ontimeorspace.Thisliteraturemaytaketheformofindividualjournalarticles, suchasGeoffreyGorhamandEdward’sSlowik’s2014paperonLocke’sabsolutism;ormonographs,suchasAntoniaLoLordo’s2007 PierreGassendiandthe BirthofEarlyModernPhilosophy.Whilstvaluableinthemselves,thesespecialist studiesarenotgenerallyconcernedwiththewiderdevelopmentoftimeorspace inthisperiod.Thatsaid,JasperReid’s2012 TheMetaphysicsofHenryMore constitutesanimportantexceptiontothisrule.

Thethirdgrouprelatestoanongoing,multifaceteddebatethatdraws directlyontheconceptualframeworksdevelopedduringourperiod.Oneof themostfamoussetpiecesofearlymodernmetaphysicsisaseriesoflettersthat passedbetweenSamuelClarke,whoissometimesreadasactingasNewton’ s mouthpiece,andLeibniz.AsdetailedinChapterIX,Clarkedefends ‘absolutism’ , andLeibnizappearstodefend ‘relationism ’,onwhichtimeandspaceare identifiedwiththetemporalandspatialrelationsholdingbetweenbodies.

1 SeealsoGunn(1929),Heath(1936),Whitrow(1988),Turetzky(1998),andJammer(2006).

Today,adescendantofthisdebatecontinues:absolutismor ‘substantivalism’2 stillbattlesrelationism.Asaresultofthecloseconnectionsbetweentheearly modernabsolutism–relationismdebate,andtoday’sabsolutism/substantivalism–relationismdebate,anumberofstudiesdigintotheformerwiththeaimof sheddinglightonthelatter.Toillustrate,JohnEarman’s1989 WorldEnough andSpace-Time:AbsoluteVs.RelationalTheoriesofSpaceandTime opensby consideringNewtonianabsolutism;andGordonBelot’s2011 GeometricPossibility, astudyofrelationism,containsalengthyexplorationofLeibniz.3 Although fascinating,thesestudiesrarelygobeyondtheirtightlylimitedremit,andhence areunconcernedwiththedevelopmentalstoryofearlymodernabsolutism.

Finally,thereisthegroupofliteraturemostrelevanttothisstudy:widerangingexplorationsoftheearlymodernperiodwithaspecialemphasisonthe developmentoftherelevantmetaphysics.Thetwentiethcenturysawseveral suchmagisterialtomes:E.A.Burtt’s1924 TheMetaphysicalFoundationsof ModernPhysicalScience,AlexandreKoyré’s1957 FromtheClosedWorldtothe InfiniteUniverse, andEdwardGrant’s1981 MuchAdoAboutNothing. 4 Although thesestudiesarefocusedonspaceratherthantime,manyoftheirconclusions areimportanttousbecausesomanyphilosopherstreattimeandspacesymmetrically.However,Burtt,Koyré,andGrantareinterestedinthedevelopmental historyofspaceinWesternEuropeanphilosophymorebroadly,consideringthe workofItalianthinkerssuchasGalileo;FrenchthinkerssuchasDescartes, Gassendi,andNicolasMalebranche;DutchthinkerssuchasSpinoza;andGerman thinkerssuchasJohannesKeplerandLeibniz.Incontrast,thisstudyfocuses exclusivelyonBritishthinkers.WhilstthesetomesdiscussBritishthinkers and thefollowingpageswillfrequentlyengagewiththem theydonotenternearlyso deeplyorbroadlyintotheBritishcontext.

The finalpieceofliteraturebelongingtothisgroupdeservesaspecialmention: JohnTullBaker’s1930 AnHistoricalandCriticalExaminationofEnglishSpace andTimeTheories.Asitstitlesuggests,Baker’smonographbearscomparison

2 ‘Substantivalism’ isatwentieth-centurytermofartforapositionwhichisusuallytakentobe closelyrelatedtoabsolutism.Sklar(1977,162)characterizessubstantivalismastheviewthatspace orspacetimehasan ‘independentreality...akindofsubstance’.Dainton(2001,2)writesthat substantivalistswouldincludespaceandtimeintheirinventoryoftheworld,andprovidesahandy pictorialrepresentationofspaceasacontainer.Belot(2011,2)writesthatsubstantivalistsmaintain thatspaceconsistsofpartsandthatthegeometricrelationsbetweenbodiesarederivativeonthe relationsbetweenthepartsofspacetheyoccupy.

3 SeealsoSklar(1977),Barbour(1989;1999),Jammer(1993),andDainton(2001).

4 IfreadersarewonderingwhyIdonotplaceMichaelEdwards’ excellent2013 Timeandthe ScienceoftheSoulinEarlyModernPhilosophy inthisgroup,itisbecauseEdwardsexplicitlytracks theAristoteliantraditionthroughthisperiod,andabsolutismisananti-Aristotelianposition.

withthepresentvolume:itconsidersthedevelopmentalhistoryofspaceandtime inEnglishphilosophy,anditschoiceof figurespartlyoverlapswithmyown. Nonetheless,therearedifferences.OneisthatBakerisconcernedwithEnglish theoriesgenerally,notabsolutisminparticular.Anotheristhatthepresentstudy enterssignificantlyfurtherintotheperiod,discussingafarbroaderselectionof figuresandviews.Additionally,itisworthnotingthatonmanyissuesthisstudy disagreeswithBaker’s;forexample,BakerreadsBarrow,Locke,andNewtonas absolutistsinthestyleofMore,andIrejectsuchreadings.Nonetheless,thisstudy owesagreatdebttoBaker’swork,andtomany,manyotherworksofscholarship.

Scope

Thissectionexplainsthescopeofthisstudywithregardtogeography,historical period,andtopic.

Geographically,Itake ‘British’ intheearlymodernsense,tocovertheStuart kingdomsofEngland,Scotland,andIreland,andtheprincipalityWales.Itwillbe seenthatallthemain figuresofthisstudyandmany(thoughcertainlynotall)of thesupportingcastareEnglish.AsSarahHutton(2015,4)explainsinherlandmark BritishPhilosophyintheSeventeenthCentury,itisamatterofhistoricalrecordthatin theseventeenthcentury,Englandproducedmorephilosophersofnotethantherest oftheStuartkingdomsputtogether.AlthoughScotlandhademergedasaphilosophicalpowerbythemid-eighteenthcentury,thisstudywillnottakeusquitesofar.

Anadvantageofthisgeographicfocusisthatitallowsustostudyaninterconnectednetworkofphilosophers,manyofwhomwerepersonallyacquainted. Inadditiontopersonalfriendships,thesephilosopherscameintocontact throughcorrespondence,andbyreadingoneanother’sbooks.Toprovideafew illustrations,NewtonreadMoreandCharletonclosely,andengagedpersonally withMoreandBarrowatCambridge;NewtonandClarkebecameclosefriends andwerelaterneighboursinLondon;LockereadMore,anddevelopeda friendshipwithNewton;ClarkeexchangedlettersonphilosophywithJackson, whichinturnledtoafriendship;andJacksonmadeuseofLocke’stexts.Itisno coincidencethatthese figuresaresocloselylinked;onthecontrary,Ihaveselected thempreciselybecauseofit.Theprocessoftracingintellectualconnectionshasled meto figuresfaroutsideofthecanon,withtheaimofmoreaccuratelysketching thedevelopmentofabsolutetimeinearlymodernBritishmetaphysics.

AlthoughthisstudyfocusesonatightlyconnectedcoreofBritish figures,they werenotworkinginageographicvacuumfromtherestofEurope.Aswewill see,inadditiontoreadingbooksauthoredbyphilosopherslivingontheContinent,Britishphilosopherssometimescorrespondedthroughletterwiththeir Continentalcontemporaries,ormetthemthroughtravel.Togiveafewexamples,

someofourphilosophersareengagingwithDescartes’ identificationinrealityof spacewithmaterialbody;withGassendi’sabsolutism;withSpinoza’sperceived pantheismoratheism;andwithLeibniz’srelationism.Consequently,Iprovide briefdiscussionsoftheseissuesalongtheway.Althoughthisstudydoesnotoffer in-depthinterpretationsofnon-British figures,itdoesprovidereferencesto furtherliteraturefortheinterestedreader.

Historically,thescopeofthisstudyisroughlyacentury,startingfromthe 1640s.Tobemoreprecise,thisstudystartswithMore’s1647 Philosophical Poems,andendswithJackson’s1734 TheExistenceandUnityofGod,which ItaketobethelastrealcontributiontoBritishabsolutistmetaphysicsoftime duringtheearlymodernperiod.

Althoughthisstudyislimitedintemporalscope,our figureswerenomore workinginatemporalvacuumthanageographicone,andmanyofthemare respondingtopastunderstandingsoftime,including,mostprominently,Aristotle’ s. Forthisreason,the firstchapterofthisstudyprovidesaspeedyandhighly selectiveintroductiontothehistoryofphilosophyoftimefromantiquity,again withmanyreferencestofurtherreading.Relatedly,asabsolutismabouttimedoes notpulltoacompletehaltin1734,the finalchapterindicateshowthedebate continuesafterthispoint.

Movingontotheobjectofthisstudy,theprimaryfocusis(asindicatedbythe title)onabsolutistmetaphysicsoftime.However,itsscopeiswiderthanthisin severalrespects.Forexample,Ialsodiscusstheworkoftwo figuresIreadasnonabsolutists:BarrowandLocke.Theyareincludedherebecausetheyarecommonlyreadasabsolutists.Astimeandspacearesocloselylinkedinthisperiod, Idiscuss(albeitmorebriefly)Britishabsolutismaboutspace.Ialsodiscuss variouscritiquesofabsolutism,andanumberofnon-absolutistpositionson timeadvancedbyBritishthinkersinreactiontoabsolutism.

Withregardtomydiscussionsofthelatter,Iaddanote.OfBritishphilosophers writingbetween1647and1734,four ‘giants’ standout:Hobbes,Newton,Locke, andBerkeley.Ofthesegiants,onlyNewtonandLockearediscussedindetailinthis study,becauseonlyNewtonandLockearecommonlytakentobeabsolutists. Nonetheless,itmightbewonderedwhyHobbesandBerkeleyarenotaccorded moreprominentdiscussions.ThereasonisthatIsimplycouldn’tcovereverything, andwherepossibleIchosetofocusmyenergieson neglected partsofthehistory. ThereisasignificantamountofscholarshipontimeinHobbesandBerkeley (again,thesereferencesareprovidedintheappropriateplacesfortheinterested reader).Incontrast,asfarasIamaware,thereisnoscholarshipatallontimeinthe workof figuressuchasMargaretCavendish,NathanielFairfax,orJosephClarke.

Itake ‘metaphysics’ verybroadly,inlinewiththewayitwasunderstoodduring theperiod:metaphysicswasnotclearlydistinguishedfromsubjectswemight

nowlabelphysicsortheology,andconsequentlydiscussionsofmetaphysics frequentlyleadintothem.5 DespitehowbroadlyIinterpretmetaphysics,this studystillgoesbeyondmetaphysicsinvariousways.Balancingthehistoryand thephilosophyinanyhistoryofphilosophyisdifficult,andalongtheway thisstudyaimstoprovideenoughhistory scientific,theological,social,and political tounderstandthephilosophy.Tothisend,the firstchapterprovides historicalcontextaswellasphilosophicalcontext,forexample,discussingthe developmentofthependulumclockandtheriseofapocalypsestudies.Additionally,eachofthemain figuresinthisstudyreceivesabriefbiographicalsketch, whichhelpsustoplacethemhistoricallyandintellectually(aswellascommunicatingafaintimpressionofthe people behindtheideasunderdiscussion). Althoughthisstudywillprimarilybeofinteresttohistoriansofphilosophyand contemporaryphilosophersoftime,thiscontextualizationshouldhelptorender thebookaccessibletoscholarsworkinginrelated fields,suchasthehistoryof science,orphilosophicaltheology.

GeneralTheses

Inadditiontothethesesadvancedbyindividualchapters,thisstudyadvances twogeneraldevelopmentaltheses.The firstisthatthecomplexityofpositionson time(andspace)defendedinearlymodernthoughtishugelyunder-appreciated. Tomakethispoint,imaginethatourwedgeofhistoryisakindoflandscapethat isbeingstudiedandpainted.

Manypiecesofliterature inthe first,third,orfourthgroupsdescribedin SectionI.1ofthischapter areapproachingthislandscapefromafar,paintingit aspartofalargerbackdrop.Fromthiswiderperspective,themountainsare especiallyprominent,whilstthelessobviousfeaturesofthelandscapefadetoan indistinguishableblur.Consequently,onecancomeawaywiththeimpression thatthereisnothing to thislandscapeexceptitsmountains.Thisisespeciallytrue ofthelavishliteraturedealingwiththedebatebetweenNewtonianabsolutism andLeibnizianrelationism,eitheronitsowntermsorwithaneyetomorerecent philosophy:thesemountainouspositionsareforegroundedsoexclusivelythat onecancomeawaywiththeimpressionthatinearlymodernphilosophythey weretheonlypositionseverdefended.6

5 Toillustrate,Descartesoncehappilycoveredthenatureofthesoul,thenecessityofGod,the formationofthematerialuniverse,andthemovementofthetidesinjustonework the Principlesof Philosophy andmanyofourBritishauthorsadoptasimilarlywholesaleapproach.

6 Forexample,Earman’s(1989,1–2)openinghistoricalsurveyoftherelationism–absolutism debatementionsnootherpositions.Dainton(2001,2)writesthatthereare ‘twoopposedviews’ on

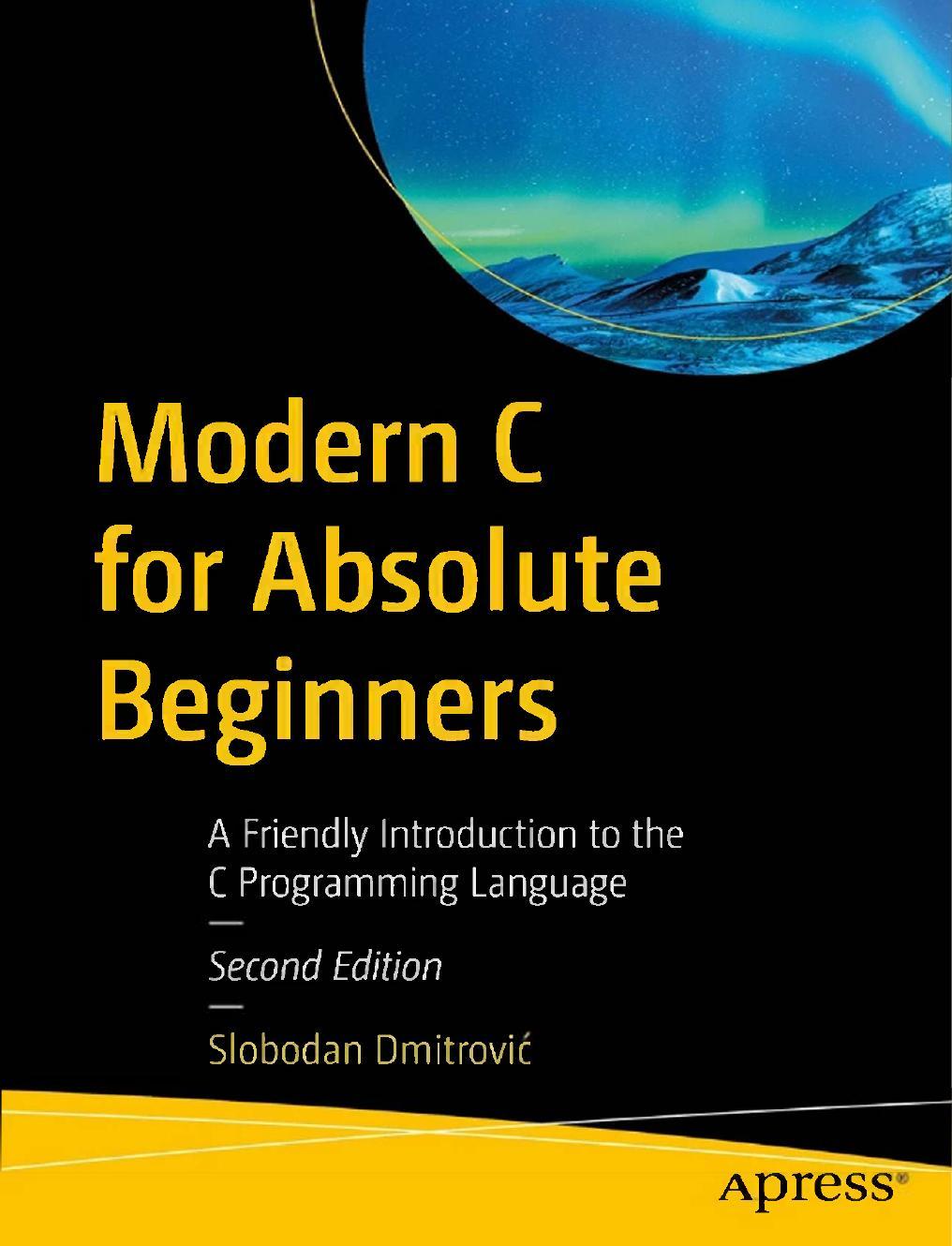

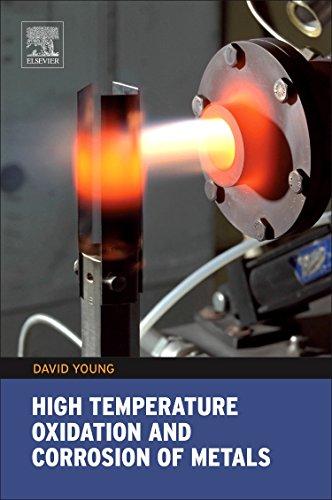

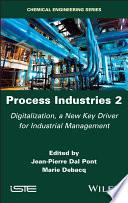

Question I: Assuming reality is temporal or spatial, is time, duration, or space something?

YesNo

Question II: Is time, duration, or space independent of human minds?

Yes

Question III: Is time, duration, or space independent of material bodies?

No

‘Void’ theory e.g. time is nothing

‘Idealism’ e.g. time comprises an abstract idea, or mind-dependent relations

No

Yes

‘Absolutism’ e.g. time is identified with God’s eternity, or time is an independently existing being

‘Non-absolutist realism’ e.g. time is identified with the successive motions of real bodies, or time comprises real relations

FigureI.1. Roadmaptoearlymodernmetaphysicsoftime,duration,orspace.

Bypaintingthislandscapefromacloserperspective,resolvingtheblurinto woodsandhillsandfolds,thisstudydecisivelyoverthrowssuchmisimpressions. Aswewillsee,awiderangeofpositionsontime,duration,andspaceare defendedbyearlymoderns.Asthereissomuchvariety,Ihavecreatedakind of(non-exhaustive)roadmaptothem(seeFigureI.1).

Understandingthemaprequiressomeexplanation,aprocesswhichwillhave theadditionaladvantageofpinningdowntheterminologyusedthroughoutthis

theontologicalissueofwhetherspaceandtimeexist:substantivalismandrelationism.Having defined ‘realism’ astheviewthatrealityhasadeterminatespatialstructure,Belot(2011,1–2)tellsus firmly, ‘Realistsaboutspacecanbeeitherrelationistsorsubstantivalists’

study.QuestionIassumesthattheworldistemporalorspatial,inthesensethat realityhassomekindoftemporalorspatialstructure,suchthatthingsreally happenbeforeorafteroneanother,orspacecanbesaidtobeinfiniteor finite.As farasIamaware,thisassumptionissharedbyallBritishthinkersduringthis period;itisonlydeniedbycertainidealistswhoholdthattimeandspacebelong toappearance,notreality.7 QuestionIaskswhethertime,duration,orspaceis anythingatall,includingaproductofthehumanmind.Theoristswhoanswer thisquestionnegativelyarecommittedto ‘voidtheory’:thepositionthattime, duration,andspaceareliterallynothing,theyaremereabsenceor(asSamuel Clarkeputsit) ‘absolutelyNothing’ . 8 InearlymodernBritishphilosophythis positionseemstohavebeenadoptedbyAnthonyCollinsandWilliamWollaston.

QuestionIIaskswhethertime,duration,orspaceisindependentofhuman minds.Ilabelthinkerswhoanswerthisquestionnegatively ‘idealists’9 abouttime, duration,orspace,andthereishugevarietyamongstthem.Forexample,inthe earlyseventeenthcentury,Hobbesdescribestimeandspaceasimaginarychimeras;HobbesisworkinginthemajorAristoteliantraditionwhichtakestimeto dependonthemind.Intheearlyeighteenthcentury,EdmundLawandIsaac WattsholdsthattimeandspaceareLockeanabstractideas;Berkeleyappearsto identifytimewiththesuccessionofideasinourminds;andJosephClarkeholds thattimeandspacearemind-dependentrelations,aformofrelationism.Itis importanttodistinguishthesemetaphysicalviewsaboutwhattime is,from epistemologicalviewsaboutour knowledge oftime.Toillustrate,itwouldbe consistenttoholdthemetaphysicalviewthattimeisabsolute,andalsohold theepistemologicalviewthatweobtainourideaoftimeby(say)reflectingonthe successionofourideas.

Againsttheidealists,allthinkerswhoanswerQuestionIIpositivelyare ‘realists’ abouttime,duration,orspace.QuestionIIIdividestheserealistsinto twocamps.ThinkerswhoanswerQuestionIIInegativelyarerealistsbutnot absolutists,andtheyareratheramixedbunch.Intothiscampfallsadvocatesof thesecondmajorAristoteliantraditionontime:thosewhoidentifytimewiththe motion,orthemeasureofthemotion,ofthecelestialbodies.Thiscampincludes thinkerssuchasMargaretCavendishandAnneConway,whoidentifytimewith

7 Togiveanexample,theearlytwentieth-centuryidealistJ.M.E.McTaggartarguesthatinreality nothingistemporalorspatial,suchthatnothingreallyhappensbeforeorafteranythingelse.For manyfurtherexamples,seeThomas(2015b).

8 Aswewillsee,Clarkedistinguishesthisviewfromthepositionthatspaceis ‘amereIdea’.Sotoo doIsaacWattsandEdmundLaw.

9 Thereishistoricalbasisforthisterminology.Forexample,JosephClarke(1734,4)labelsthings thatonlyexistinthemind ‘ideal’

themotionsoractivitiesofcreatedbeings.Further,thiscampincludesrelationistssuchastheearlyLocke,whoholdthattimecomprisesmind-independent temporalrelations.

ThinkerswhoanswerQuestionIIIaffirmativelyareabsolutists.Together,these threequestionsunderliemycharacterizationofabsolutismastheviewthattime, duration,orspaceisindependentofhumanmindsandmaterialbodies.Although thisprecisecharacterizationismyown,Idonotbelieveitiscontroversial.Many scholarlydiscussionsofabsolutismrefrainfromcharacterizingit,butthosethat dogenerallyemphasizethe independence oftime,duration,orspacefromother beings.10 AlthoughIspeakof ‘absolute’ time,duration,andspacewithregardto many figures,someofthemdidnotusethisterm,asitdidnotbecomecommon currencyuntilafterthepublicationofNewton’s1687 Principia.Nonetheless,Ido notbelieveanyofthemwouldobjecttomyuseoftheterm ‘absolute’ whenitis understoodtomeanindependentofhumanmindsormaterialbodies.11 Inany case,theterm ‘absolute’ iswidelyappliedinexistingscholarshiptotheoriesof timepredatingNewton.

Thesecondgeneral,developmentalthesisofthisstudyisthatduringthis periodthreedistinctkindsofabsolutismemergedinBritishphilosophy.Oneis ‘Morean’ absolutism,anditholdsthattime,duration,orspaceis reallyidentical withGod.Onthisview,time,duration,orspacemaybeconceptuallydistinct fromGod,but,inreality,theyarethesamebeing.WewillseethatHenryMore’ s workliesattherootsofthispositionwithregardtoearlymodernBritish metaphysics.Moreanabsolutismcanbecontrastedwith ‘Gassendist’ absolutism, onwhichtime,duration,orspaceis reallydistinct fromGod.Asmylabel suggests,GassendistabsolutismshavetheirrootsintheworkofGassendi (althoughwewillseethatGassendi’sactualpositionontherelationshipbetween space,time,andGodisunclear).

10 Earman(1989,11)takesonesenseofabsolutenesstobethatthereisanabsoluteduration, ‘independentofthepathconnectingtheevents’.Ariotti(1973,31)describesabsolutetimeas ‘independentofexternalmotion’.Ferguson(1974,42)writesofNewton’sabsolutism, ‘thestatusofspace andtimeisthatofsubstanceswhichhavetheirownindependentexistence’.Hutton(1977,363)refersto the ‘measureofindependence’ accordedtoabsolutetime.Edwards(2013,1)writesthatabsolutetimeis ‘whollyindependent’ ofanything ‘external’,includingmotionandthehumansoul.Aswewillseelater inthissection,Janiakalsoemphasizesindependence.

11 AswewillseeinChapterIV,BarrowusesthetermbeforeNewton,forexample,inthecontext ofarguingthattheabsolute(absolutam)andintrinsicnatureoftimedoesnotimplymotion. FollowingNewton’ s Principia,Toland(1704,12–13)describes ‘absoluteTime’ asdistinctfromthe durationsofthings.Later,againwritingonNewton’sabsolutism,HenryPemberton(1728,112) statesthatabsolutetime ‘consideredinitsselfpassesonequablywithoutrelationtoanything external’.Allthesecharacterizationsofabsolutismarecompatiblewithmine.