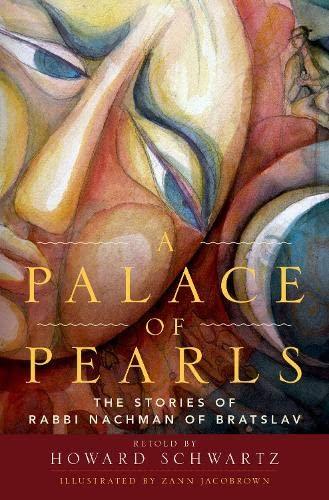

A Palace of Pearls

The Stories of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav

RETOLD BY HOWARD SCHWARTZ

FOREWORD BY RABBI RAMI SHAPIRO

ILLUSTRATED BY ZANN JACOBROWN

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© 2018 Howard Schwartz Illustrations © Zann Jacobrown

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Nachman, of Bratslav, 1772–1811, author. | Schwartz, Howard, 1945– author, translator. Title: A palace of pearls : the stories of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav / retold by Howard Schwartz ; foreword by Rami Shapiro. Description: New York, NY : Oxford University Press, [2018] | Some of these stories previously appeared in other works by the same translator. | Includes bibliographical references and index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017033700 (print) | LCCN 2017035517 (ebook) | ISBN 9780190243579 (updf) | ISBN 9780190243586 (epub) | ISBN 9780190243562 (cloth)

Subjects: LCSH: Hasidic parables. | Nachman, of Bratslav, 1772–1811.

Classification: LCC BM198 (ebook) | LCC BM198 .N24213 2018 (print) | DDC 296.1/9—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017033700

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed by Sheridan Books, Inc., United States of America

Some of these stories previously appeared in Elijah’s Violin & Other Jewish Fairy Tales, Miriam’s Tambourine: Jewish Folktales from Around the World, Lilith’s Cave: Jewish Tales of the Supernatural, Gabriel’s Palace: Jewish Mystical Tales, Leaves from the Garden of Eden: One Hundred Classic Jewish Tales, Reimagining the Bible: The Storytelling of the Rabbis, Gates to the New City: A Treasury of Modern Jewish Tales, and Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism.

The Diagram of the Ten Sefirot on page 373 is by Tsila Schwartz.

For Tsila, Shira, Nati, Miriam, Babak, Ari, Ava, Ariyah, and in memory of my parents, Nathan, and Bluma Schwartz

I tried to bring you back to God through my talks and Torah teachings, but they haven’t worked. So now I must tell you stories. People say stories help you fall asleep. But I say that telling stories wakes people up.

Reb Nachman of Bratslav Siach Sarfey Kodesh 2 p. 124, #476 and Hayey Moharan 8b #25

Every story has something hidden. What is concealed is the hidden light. God created light on the first day, the sun, the moon, and the stars on the fourth. What was the light that existed before that of the sun? It was a sacred, primordial light, and God hid it for future use. Where was it hidden? In the stories of the Torah.

Reb Nachman of Bratslav Likutey Moharan 1, #234

CONTENTS

Foreword: “People of the Stories” by Rabbi Rami Shapiro xiii

Preface xix

Acknowledgments xxiii

Introduction 1 PART ONE THE MAJOR STORIES

The Lost Princess 25

The Pirate Princess 35

The Enchanted Tree 43

The Bull and the Ram 48

The Prince Who Was Made of Precious Gems 52

The Missing Portrait 58

The Spider and the Fly 61

The Rabbi and His Son 64

The Clever Man and the Simple Man 66

The Merchant and the Pauper 75

The Prince and the Slave 88

The Master of Prayer 95

The Seven Beggars 117

PART TWO ADDITIONAL STORIES

The Tale of the Bread 149

The Hanukkah Guest 154

The Tzaddik of Sadness 157

Destined to Be a Thief 159

The Rich Man and the Thief 163

The Tale of the Pact 164

The Tale of the Diamond 167

The Palace Beneath the Sea 169

A Tale of Delusion 173

The Perfect Saint 175

The Mysterious Painting 177

Hungarian Wine 179

PART THREE THE PARABLES

The Angel of Losses 183

The Menorah of Defects 184

The Prince Who Thought He Was a Rooster 186

The Synagogue in Jerusalem 188

The Soul of the World 190

The Coming of the Messiah 192

A Parable of Father and Son 193

The Fable of the Rose and the Thistle 194

Harvest of Madness 195

The Tale of the Millstone 196

The Princess of the Torah 197

The Fable of the Spider Web 199

What Am I Holding? 200

The Parable of the Eggs 201

The Tale of the Wolf 201

The Map of Time and Space 202

The Heart of the World 204

The Fable of the Two Birds 206

The Last Resort 209

The Tale of the Candles 210

When a Candle Is Blown Out 211

The Wise Son and the Foolish Son 212

The King and the Peasant 213

The Condemned Prince 214

The Tale of the Letter 215

The Three Messengers 216

The Royal Messenger 217

The Wheel of Creation 219

PART FOUR DREAMS AND VISIONS

The Endless Forest 223

The Dream of the Shofar 224

The Dream of the Brides 225

The Tzaddik Who Was Shunned 226

The Vision of the Man in the Circle 227

The Sea of Wisdom 229

Unable to Teach 230

The Dream of the Birds 231

The Dream of a Throne 232

The Sacrifice 233

A Dream of Disgrace 234

The Accusation 235

The Man Who Had Died 237

The Dream of a Wedding 238

PART

FIVE

The Treasure 243

The Fixer 245

FOLKTALES TOLD BY REB NACHMAN

The Jealous Minister 249

The Road to the Cemetery 251

A Tale of Two Artists 252

PART SIX TALES OF HASIDIM TOLD BY REB NACHMAN

The Sabbath Guests 257

Capturing the Bird 259

The Ba’al Shem Tov and the Preacher 260

The Opposition of the Birds 261

The Journey of the Dead Merchant 262

The Hasid Who Had Died 264

The Simple Servant 265

For the Sake of a Cat 265

The Plank and the Pillar of Fire 266

PART SEVEN HASIDIC TALES ABOUT REB NACHMAN

Bound to Reb Nachman 271

The Chamber of Souls 272

Reb Yisroel the Dead 274

A Vision of Light 275

The Tale of the Plums 276

The Scribe 279

The Sabbath Fish 280

The Lost Tale 282

The Journey to Kamenetz 283

The Sword of the Messiah 288

The Master of the Field 290

The Tale of the Lamp 293

A Hidden Saint 296

A Healing Verse 297

An Argument with the Evil One 298

The Tale of the Question 299

Divining from the Zohar 301

The Tale of the Heavenly Court 302

The Mysterious Old Man 304

The Rabbi’s Attendant in the World-to-Come 305

The Book That Was Burned 306

A Letter from the Beyond 308

Reb Nachman’s Chair 310

Reb Nachman’s Tomb 312

The Soul of Reb Nachman 314

PART

EIGHT

STORIES RETOLD FROM UNFINISHED TALES OF REB NACHMAN

A Garment for the Moon 319

The Souls of Trees 325

The Celestial Orchestra 328

The Mountain of Fire 333

The Lost Tzaddik 340

The Golden Bird 343

The Tale of the Deer 348

The Princess of Light 350

The Hollow of the Sling 352

APPENDICES

I. The Art of Telling and Retelling 355

II. The Exile of the Shekhinah 359

III. How the Ari Created a Myth and Transformed Judaism 363

IV. Cosmic Cataclysms in Jewish Tradition 369

V. Diagram of the Ten Sefirot 373

VI. Important Dates in Reb Nachman’s Life 375

Notes 377

Glossary 385

Hebrew Bibliography 391

English Bibliography 393

Index 399

FOREWORD: “PEOPLE OF THE STORIES”

By Rabbi Rami Shapiro

We are the stories we tell. Stories provide us with identity, meaning, and purpose. Story is how we make sense of the world, and find a place for ourselves within it.

In the premodern past we believed that our stories were not stories at all, but facts. To draw from the stories with which I am most familiar: God created the world in six days and destroyed it in forty—fact. Humanity began with a single couple, Adam and Eve—fact. God spoke to Abraham and chose his and Sarah’s descendants as His chosen people—fact. God plagued the Egyptians, split the Red Sea, wrote the Ten Commandments, deeded His Chosen in perpetuity with a land flowing with milk and honey—all facts.

For premodern thinkers (whether ancient or contemporary) story is history, history is the will of God, and war determines whose god is God. Eve, for premodernists, is an historical figure, drawn from the side (or rib, depending on whether you are reading the Bible in Hebrew or Greek) of Adam. It was she who brought death into the world, and caused the exile of humanity from paradise. Modern thinkers claim to separate history from story, relegate story (including theology and religion) to the sidelines, and argue that if we can only get beyond our stories—religious, ethnic, national, tribal, etc.—we would create a world of peace and harmony based on facts alone. Perhaps, but at what cost?

A world without story is a world without imagination, creativity, and possibility. As Albert Einstein told a Saturday Evening Post reporter in 1929, “I am enough of the artist to draw freely upon my imagination. Imagination is more important than knowledge. Knowledge is limited. Imagination encircles the world.” What Einstein is calling “knowledge” I am calling “fact.”

Of course the modern world isn’t bereft of story; it simply relegates story to the domains of entertainment and advertising. The hero’s journey is the stuff of movies and theme parks. In the entertainment universe the heroine/hero wins by acquiring the proper weapon; in the advertising universe, the heroine/hero wins

by acquiring the proper deodorant, smartphone, or app. Outside of entertainment and advertising, however, the heroine/hero doesn’t win at all, and is merely a cog in the military–cyber–financial complex that convinces us that being consumers is the highest human attainment, while in fact reducing us to the consumed.

Like premodernists, postmodern thinkers understand that there is no getting beyond story: story is who we are. Unlike them, however, postmodernists know that story is not history, and suspect that even history isn’t history, but merely the story told to explain why the winners won (God willed it) and the losers lost (they backed the wrong god). This does not mean there is no reality transcending our stories, only that we cannot step outside of story to experience it directly. If we could see reality without the lens of story, what we would see is so profoundly beyond our ability to understand that it would in all likelihood drive us insane. So even scientists tell us a story in order to provide the unalloyed chaos of the universe with a veneer of meaning and purpose.

The postmodern condition is about knowing that we cannot know, and this notknowing is profoundly liberating because it is deeply humbling. When you imagine you know the truth (the modernist), or worse, that you somehow own it (the premodernist), you are easily seduced to cruelty and violence in defense of your story. When you know you don’t know; when you know you can’t know, you can’t be manipulated by those who pretend to know: the storytellers who occupy the seats of power, national, religious, and economic.

Premoderns, mistaking story for fact, fear the gods they invent; moderns, mistaking story for falsehood, fear the gods others invent; postmoderns, knowing that story is essential and yet never more than story, see gods as psychological archetypes, and replace fear with a gentle humor that allows them to live gracefully in the face of uncertainty. Where the premodern doesn’t recognize story, and the modern denigrates story, the postmodern celebrates story.

I am a postmodernist. I cannot live without attending to fact, but I cannot thrive without attending to story, the product of imagination. Story carries archetypal truths from the unconscious to the conscious. Story is a map to territory so deeply imbedded in the human psyche that MRI scans alone cannot grasp it.

I am also a rabbi. For me Judaism isn’t a matter of ethics and law, but of myth, legend, and story. My postmodern Judaism honors story as story, and embraces myth and metaphor as the best tools we have for pointing beyond the idols of the known toward the reality of the unknown and unknowable. For me a Jew is a person whose personal story is consciously, though by no means exclusively, shaped by Jewish stories to which she or he turns when seeking meaning and life-purpose. For me Jewish identity is rooted not in genes, but memes, the carriers of culture among which story reigns supreme.

I am also a perennialist. I believe that the deep teachings of Jewish stories are mirrored in the equally deep teachings of Hindu, Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim stories, among many others. I believe that to restrict myself to one set of stories is

to abandon the fullness of my humanity. And I believe that if humanity is to have a creative future, our stories must be revealed for what they truly are: human maps to meaning, timeless vehicles for carrying the deepest spiritual yearnings of the human psyche into the realm of consciousness, where they can be embodied in acts of justice, kindness, and humility.

Enter the Rebbe

Jews have been telling stories since, well, since there were Jews. After all, our most sacred text, Torah, opens with bereshit or “Once upon a time . . .” Most of the stories we tell—both ancient and modern—are about ourselves, but there is an exception: the perennialist stories of Rebbe Nachman of Bratslav.

Rebbe Nachman was born in 1772 in Medzeboz, in what was eastern Poland and what is today Ukraine. His mother, Feiga, was the granddaughter of Rabbi Israel ben Eliezer, the founder of Hasidism best known as the Ba’al Shem Tov, the Master of the Good Name. By his mid-teens Rebbe Nachman was gathering a following, and while his teachings were innovative, they were, by and large, well within the traditional mode of Jewish teaching. Then, seemingly without giving his disciples any advance notice, the Rebbe proclaimed, “I will now begin to tell stories.”

His proclamation is often linked to his commentary on Psalm 119:126: It is time to work for God, for they have disregarded Your Torah. The Torah that is disregarded is not the Halakhic (legal) rulings of the rabbis pertaining to people’s behavior, but to the deeper spiritual wisdom Rebbe Nachman thought Judaism embodied. The people have kept the form but have lost sight of the meaning. To regain the meaning—the innermost wisdom of Torah—new stories must be told.

These new stories are not over and against Torah, but are the very heart of Torah. This, Rebbe Nachman says, is derived from the notion of p’sol, to carve. In Exodus 34:1 Moses is told to carve out two stone tablets on which God will (for a second time) write the Ten Commandments. Rabbinic tradition takes this to mean that Moses was to take stones and chisel away the excess rock until what remained were the two tablets he needed.1 Nachman sees himself as doing something similar with his stories: carving away what is nonessential to divine wisdom until what is left is the essential revelation of God—Nachman’s stories.2

According to Rebbe Nachman, the process of awakening people to wisdom is best done through stories:

When we want to show people their true face (as the Image and Likeness of God) and hence awaken them from sleep (ignorance), we must clothe the face in stories that the listener might be able to grasp the truth and awaken to it.3

Stories have the potential to reveal one’s truest face and awaken one to being that face, but not just any stories. Up until Rebbe Nachman, Jewish stories fell into various baskets: stories from the Bible, stories told by the early sages elaborating on Bible tales, stories told about the early rabbis and later the Hasidic masters, etc. All of these stories were intrinsically and extrinsically Jewish: that is, they spoke of, about, and to Jews. Rebbe Nachman, too, told such stories, but the stories he began to tell in order to awaken people to their true face are of a different order altogether.

Rebbe Nachman wasn’t trying to retell ancient tales; he was trying to articulate the deep spiritual nature of humanity. And because he was trying to do so through language, he used archetypal tales rather than tribal legends as his primary tool. The stories Rebbe Nachman told differed from most others in Jewish life in that they weren’t stories about Biblical figures, rabbinic sages, or other Hasidic Rebbes. They were mythic tales whose central characters were archetypal figures such as princesses, kings, peasants, and beggars. These new stories, the stories Howard Schwartz shares in A Palace of Pearls, were archetypal tales articulating the universal truths. They were not “once upon a time” tales, but “at this very moment” tales: stories that showed you your true face and shocked you awake. As such, you don’t merely read the stories of Rebbe Nachman, you live them. The characters in his tales aren’t people dredged up from the past, but aspects of your psyche present at this and every moment.

In his 1806 tale “The Lost Princess,” for example, the king’s minister sets out to find and free the king’s daughter, who was kidnapped and imprisoned by the Not-Good. After many adventures, the minister finds the princess, and takes up residence in the city where she is imprisoned so that he might design and execute a plan to free her. And then, just when you expect Rebbe Nachman to tell us how the minister succeeded in his task so that we might learn from him and succeed in rescuing our own lost princess,4 he merely says, “And in the end he did free her.” But how? How did he free her? As Rabbi Nathan tells us in his writing down of the story, “How he freed her, Rebbe Nachman did not say.” Why didn’t he say? Because it isn’t for Rebbe Nachman to tell you how to free the princess, only to tell you that freeing her is possible. In other words, you are the viceroy, and the only way to know how the story ends is to live out its ending for yourself as yourself.

In this case, Nachman’s tales are more like koans than fairy tales or parables: Zen puzzles that must be solved and yet that cannot be solved until you burn through all options and opinions and are left with only the solution no longer hidden beneath a heap of conventional notions, theories, and ideas:

The koan is not a conundrum to be solved by a nimble wit. It is not a verbal psychiatric device for shocking the disintegrating ego of the student into some kind of stability. Nor, in my opinion, is it ever a paradoxical statement except to those who view it from outside. When the koan is resolved, it is realized to be a simple and clear statement made from the state of consciousness it has helped to awaken.5

In other words, you won’t know how to free the princess—until you have exhausted every way not to free her.

Nachman’s Nathan, Nathan’s Howard

Without the work of Nathan Sternhartz, known among the Bratslavers as Nathan of Nemirov, we would have scant knowledge of Rebbe Nachman. That’s because many of the Rebbe’s teachings and stories were shared on Shabbat and holy days when writing was forbidden according to Jewish law. Nathan would memorize the words of his Rebbe and transcribe them as soon as writing was again permitted. He would, when possible, review his text with Rebbe Nachman and make any changes the Rebbe deemed necessary.

Nathan took over leadership of the Bratslaver Hasidim upon the death of Rebbe Nachman in October 1810. His role was not that of Rebbe, however, for Rebbe Nachman chose no successor, suggesting instead that his spiritual presence would continue to guide his community after his death. Nathan of Bratslav took upon himself the task of spreading the teachings of his Rebbe and strengthening the movement his Rebbe started. Perhaps his most prescient act was to purchase a printing press and to begin to publish the entirety of Rebbe Nachman’s teachings and tales.

Over time, Nathan’s nineteenth-century telling of Rebbe Nachman’s tales needed refreshing; they needed the heart of a storyteller to rekindle their power. Martin Buber’s free retelling of Nachman’s stories, almost one hundred years after the Rebbe’s first telling, revealed the existentialism Buber saw hidden in the tales. A little over one hundred years after Buber, and two hundred–plus years after Nachman himself, Howard Schwartz takes up the mantle of Nathan of Nemirov and tells Rebbe Nachman’s stories anew. Howard Schwartz is a digger of tales, a restorer of story, and he has been at this for a very long time. This is not his first foray into the stories of Rebbe Nachman, but it is the first examination of Rebbe Nachman to include virtually all of his stories, dreams, visions, and parables. What Nathan did for Nachman, Howard does for Nathan: preserve the tales of the Rebbe for another age. But that is not all. This time, the goal isn’t to reframe the tales of Rebbe Nachman in light of a specific philosophical stance, but to rekindle them in the imagination of the contemporary reader so that they might once again shed light and reveal the true face of the reader to the reader.

In his magnum opus, Tree of Souls: The Mythology of Judaism (2004), Schwartz curates the vast library of Jewish myths from Torah, Talmud, and Kabbalistic sources ancient, medieval, and modern. Many of the stories in Tree of Souls reflect or build upon earlier stories, and almost all of them can be traced back to the foundation myth of Judaism itself: God so loved the world that He gave His only Revelation (Torah) to His Chosen People (the Jews) that they might be a light unto the nations (Isaiah 49:6), and lead humanity toward holiness, understood as universal justice,

compassion, humility, and peace.6 But A Palace of Pearls is different: where the myths of Tree of Souls are explicitly Jewish, the stories of Rebbe Nachman transcend ethnicity and religion. While they come to us through a Jew (three Jews in fact: Nachman, Nathan, and Howard), and while they can be made to reflect Judaism, in and of themselves they reflect nothing less than the true face of humanity.

Think of Tree of Souls as the place where mythology meets Judaism, and think of A Palace of Pearls as the place where mythology meets humanity, and humanity’s greatest struggles for awakening. Hence A Palace of Pearls is not a collection of stories to be read, but rather a collection of koans to be contemplated. Don’t read more than one tale or teaching at a time, and read it over and over again that it might chip away at the excess rock of self to reveal the holy tablets of Self on which one finds the mirrored Face of God reflected as your face and every face.

Rabbi Rami Shapiro is director of the One River Foundation and author of numerous books on religion and spirituality, including Hasidic Tales, Annotated and Explained, and The World Wisdom Bible.

PREFACE

Reb Nachman of Bratslav (1772–1810) is a unique figure in Hasidic tradition and in Jewish literature. He was the great-grandson of the Ba’al Shem Tov, the founder of Hasidim, and he was raised in the same house the Ba’al Shem Tov had lived in. Like his great-grandfather, he was recognized as a Hasidic Rebbe (master). He was not that well known during his lifetime, and he was caught up in several controversies, but today his followers number many thousands and are referred to as Bratslavers. He is widely recognized as a major Torah scholar; his Torah teachings and commentaries are found in the multi-volume Likutey Moharan (Collected Teachings of Rabbi Nachman). However, unlike every other Torah scholar, he is best known as a teller of original tales, tales that have no obvious Jewish content and yet, to the initiated, reveal hidden truths of a deeply religious and often mystical nature. Cynthia Ozick calls him “the great and visionary storyteller of the Hasidic movement.” Further, he is credited with having a major influence on succeeding generations of Yiddish storytellers, such as I. L. Peretz and Isaac Bashevis Singer. Because of his unique stories, Reb Nachman deserves to be recognized as a major literary figure, in the class of Miguel Cervantes, Hans Christian Andersen, Nikolai Gogol, Jonathan Swift, and Franz Kafka. Pinchas Sadeh, a prominent Israeli poet and literary critic said, “I have come to the conclusion that it is possible that Reb Nachman is not only the greatest writer in modern Hebrew literature, but is one of the greatest creative writers in the history of world literature.”

Reb Nachman’s life existed entirely within a pious Hasidic framework. “The only thing that has absolute existence is God Himself. God is the Place of the world.”7 Intense prayer and turning to God, along with dedicated observance to Jewish rituals and holy days, was the priority of his life. He personally was most inspired during the Jewish holy days, especially Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. He believed that the Torah is primarily intended for the soul, but that this world stands before our eyes, preventing us from seeing its light. He interpreted the verse I shall dwell in them (Ex. 25:8) to mean that “God’s Divine Presence dwells in each and every Jew.”8

For most of his career, Reb Nachman transmitted his teachings to his Hasidim by way of traditional commentary on the sacred texts, along with his own interpretations. Today that commentary, collected in Likutey Moharan, is considered a major classic. But in the last four years of his life, in addition to his Torah commentaries, he started telling stories to his Hasidim—complex, convoluted, allegorical tales. These stories, told orally in Yiddish, were later written down in Yiddish and translated into Hebrew and published in 1816 in Ostrog, Ukraine, by his loyal scribe, Reb Nathan Sternhartz of Nemirov (1780–1844). For those who don’t recognize their meaning, the stories may seem like imaginative fairy tales. But for those who perceive Reb Nachman’s true purpose, the stories are profound tales that draw on Kabbalistic myths, Jewish and world folklore, and traditional Jewish teachings. They are, therefore, successful both as entertaining narratives and as compelling allegories. As Reb Nathan writes: “The Tzaddik attempts to rouse the world from sleep by telling stories. They contain extraordinary, hidden, deep meanings.”

Reb Nachman would often walk in the forests and fields, as the Ba’al Shem Tov had done. As Hillel Zeitlin puts it: “Reb Nachman attained all his high rungs through wandering about in fields and forests, calling out the Psalms from within deep caves, sitting alone in a frail vessel on the great river.”9 There he would practice hitbodedut, meditations and conversations with God. Arthur Green defines hitbodedut as “the lone outpouring of the soul before God.”10 This finds expression in Psalms 102:1, and before God he shall pour out his heart. In his own prayer, Reb Nachman elaborated on this psalm: “May I pour out the words of my heart before your Presence like water, O Lord, and lift up my hands to You in worship, on my behalf, and that of my children.” Elsewhere Reb Nachman said, “You must always desire to come close to God,”11 and “I only came into the world to bring Jewish souls closer to God.”12 He intended the stories he told to serve this purpose, and they do. Reb Nachman had an intuitive understanding of allegory and symbolism, and the meaning of his stories was often closely linked to Kabbalah. He considered Kabbalah “The inner essence of the Torah”13 and once said of it: “Where the wisdom of philosophy ends, that is where Kabbalah begins.”14

All of Reb Nachman’s major stories were originally included in Sipurey Ma’asiyot (1816). All of these stories are included here in the order they appear in that book, with “The Lost Princess,” his first tale, first, and “The Seven Beggars,” his final tale, last. Also included here are less well-known tales, folktales he told to his Hasidim, such as “The Treasure,” and tales about earlier Hasidic masters, such as the Ba’al Shem Tov. Reb Nathan notes that “The Rebbe would sometimes relate ordinary folktales but he would embellish them.” This book also includes Reb Nachman’s surviving dreams, which he shared with his Hasidim, and which are remarkably similar to his tales. Finally, Reb Nachman often told parables, such as “The Angel of Losses,” p. 183, to illustrate his Torah teachings.

Some stories about Reb Nachman (in contrast to the stories he told), are found in various collections of Hasidic tales, primarily those of the Bratslav Hasidim, and are

included here. Hasidim loved to tell stories about the Tzaddikim (saints or masters). Reb Nachman said, “Know that the stories told about Tzaddikim are a very sublime thing. Through these stories the heart is awakened and yearns with the strongest possible yearnings for God.”15 In one tale, “A Healing Verse,” p. 297, such tales demonstrate a healing power. That is why this book includes a section of stories told by Reb Nachman about other Hasidic masters. Reb Nachman did not make up these stories, but he felt they were important enough to share with his Hasidim.

Midrash often teaches religious and ethical Jewish precepts, whether explicit or implicit. Reb Nachman’s stories never stray far from these precepts, no matter how labyrinthine they may appear. Close readers will observe that the morals of his stories follow his Torah teachings and his mystical worldview. While parable and allegory are traditional teaching methods, Reb Nachman uniquely created secular folktales and fairy tales to convey to his followers profound Torah insights and mystical truths. Although the conscious creation of folktales may seem a contradiction, since almost all folktales are anonymous and found in the oral tradition, works such as those of Hans Christian Andersen demonstrate that there can be an exception, and Reb Nachman’s tales are likewise such an exception.

There are several outstanding collections of Reb Nachman’s stories, but there is no single volume in English, until this one, that collects all of his major stories, his less well-known tales, his dreams and visions, his parables, the stories told about him, and the stories he told about Tzaddikim. As editor, I have provided sources and commentaries after each tale that I hope clarify their allegorical meanings and mystical concepts. I have also included traditional Bratslaver interpretations and contemporary scholarship. In addition I have provided an introduction that gives useful background information about Reb Nachman’s life and worldview, for a greater understanding and appreciation of his stories.

Reb Nachman loved good storytelling: “One must also know how to tell a story. Each story is a crystallization of a greater reality. The teller must take hold of the words of the tale and enter into the thought beyond them.”

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I am grateful to many people for assistance in editing this book, above all my editors Cynthia Read and Drew Anderla. Thanks, too, to my agent, Susan Cohen of Writer’s House. Many thanks to my wife, Tsila, for her patience and support while I worked on this all-consuming book. I would also like to thank my children, Shira Schwartz, Nati Zohar, and Miriam Kanani, who share my love for Reb Nachman. Special thanks to Lester Goldman for his close reading of the manuscript. I am also grateful to the following editors, scholars, rabbis, and friends: Penina Adelman, Irene Barnard, Dan Ben-Amos, Rabbi Jim Bennett, Judy Blitz, Marc Bregman, the late Deborah Brodie, Bonny Fetterman, Rabbi Tirzah Firestone, Ellen Frankel, Elliot Ginsburg, Idit Pintel-Ginsberg, Rabbi James Stone Goodman, Rabbi Arthur Green, Avraham Greenberg, the late Lyle Harris, Eve Ilsen, Zann Jacobrown, Babak Kanani, Rodger Kamenetz, Pamela Altman Malone, Daniel Matt, Jerred Metz, Tracy Nathan, the late Dov Noy, Arielle North Olson, Cynthia Ozick, Rabbi Carni Rose, Rabbi Neal and Carol Rose, Barbara Rush, Rabbi Marc Saperstein, Peninnah Schram, Cherie Karo Schwartz, David Schwartz, the late Maury Schwartz, the late Rabbi Zalman Schachter- Shalomi, Laya Firestone Seghi, Rabbi Rami Shapiro, the late Rabbi Byron Sherwin, Yaacov David Shulman, Will Soll, the late Ted Solotaroff, Rabbi Marc Soloway, Jules Steimnitz, Rabbi Lane Steinger, Steve Stern, Rabbi Jeffrey Stiffman, Susan Stone, Rabbi Susan Talve, Paul Tompsett, Shlomo Vinner, Wendy Walker, the late Yehuda Yaari, Eli Yassif, Enid Zafran, and Paul Zakrewski. I am also grateful to Reb Nachman, with whom I have lived for more than fifty years, for his enduring inspiration in my life.