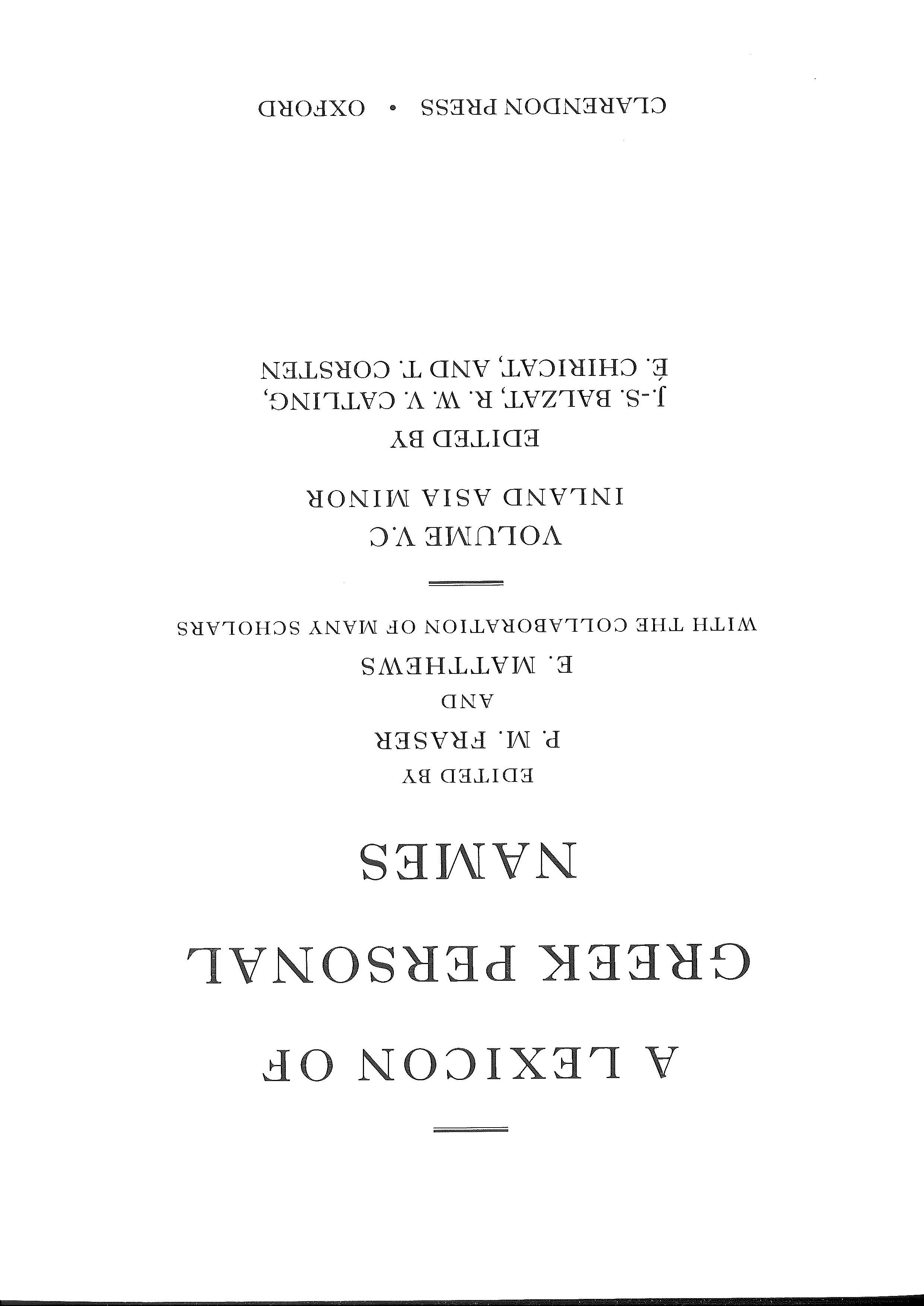

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Our first and greatest debt continues to be to the bodies that have provided funding for the Lexicon of Greek Personal N anzes. Since 2007, core funding for the project has come from the Arts and Humanities Research Council, in the form of grants under the Research Project scheme (2007-12, 2012-16, 2016-19). We also acknowledge the continuing assistance of the British Academy in granting funds for special purposes. The Academy of Athens has maintained its generous support of LGPN and we thank in particular Vasileios Petrakos its Secretary General, for his role in securing its patronage. '

We repeat our expression of gratitude to Robert Parker Director of LGPN, for his advice and support in obtainin~ this funding, as well as in many other scholarly, administrative, and practical matters that have contributed to the completion of yet another stage of the project.

Once again, in the compilation of this volume, we have incurred many debts to colleagues in Britain and in other countries and we take the opportunity to thank warmly all those who have given generously of their time, expertise, and advice or have provided us with materials not yet published. Without their contributions, this volume, like its predecessors, would be greatly impoverished.

As will be explained in the Introduction, no systematic work of compilation for the regions covered in this volume had been conducted in the early stages of the LGPN project. The only exception has been Stephen 1\/Iitchell's work on northern Phrygia. Much more recently Edouard Chiricat compiled the names from Eastern Phrygia, as part of a wider study of the region carried out over nine months in 2011/12 with the support of a grant from the John Fell Fund (University of Oxford).

Our debts to individual scholars for contributions of various kinds relating to the specific regions included in this volume are recorded below.

Eastern Phrygia

In October 2016, Peter Thonemann generously provided the texts of seventy-six unpublished inscriptions recorded by W. M. Ramsay during two journeys in this region in 1906 and 1911, together with five more from Ikonion and its territory. Altogether they have added 182 named individuals. These transcripts are preserved in Ramsay's notebooks, now housed in the Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents, Oxford University. Reference to this material cites Ramsay's notebook by year, followed by Thonemann's draft catalogue numbers (e.g. Unp. (Ramsay 1906)) which will also be cited in the eventual publication.

Galatia

Stephen Mitchell kindly made available the unpublished draft of The Greek and Latin Inscriptions of Ankara ( Ancyra). II, Late Roman, Byzantine and Other Texts edited by him and D. H. French (to be published in the Vestigia series, Munich).

Christian Wallner, during a three-month visit to work with LGPN in 2015, made a detailed study of the material compiled from Galatia, working closely with Chiricat.

See below (Phrygia) for the material from western Galatia recorded by Peter Frei.

Isauria

Mehmet Alkan granted access to the forthcoming corpus Haczb~ba Dagz. Isauria Bolgesi'nde Bir Epigrafi ve Eskirag Tarzhz Arajtzrmasz edited by him and Mehmet Kurt, containing_some seventy unpublished inscriptions with photographs, which greatly ennch the onomastic profile of an otherwise poorly documented region. Its publication is expected in the Akron Series of the Akdeniz University (Antalya).

Kappadokia

Timothy Mitford provided the epigraphic chapter of his East of Asia Minor: Rome's Hidden Frontier (Oxford, 2017), which presents the inscriptions from Melitene to Daskousa and beyond along the Euphrates, in the far east of Kappadokia bordering Armenia.

Kibyratis-Kabalis

Names have been drawn from a considerable number of unpublished inscriptions, in particular from the territory of Kibyra and the region to its north and northeast; most of these will be published by T. Corsten in Inschriften aus der Kibyratis und Pisidien (IKibPis), while others are drawn from the unpublished schedae and notebooks in the collection of the 'Arbeitsgruppe Epigraphik' (formerly the 'Kleinasiatische Kommission') of the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna which generously allowed use to be made of their archives. The names from recently discovered inscriptions at Kibyra, many of Hellenistic date and therefore of great onomastic significance, unfortunately could not be made available.

Milyas

Bi.ilent iplikvioglu made available more than one hundred copies of inscriptions made by him during field trips in the Milyas and Western Pisidia during the years 1991-6. Although this important material could not be integrated in this volume, it has been of great help in the verification of old and new names attested in the region.

Phrygia

An enormous debt of gratitude is owed to Tullia Ritti who besides much other help, provided a full set of corrected read~ ings for the published funerary inscriptions from Hierapolis. Her corrections are indicated where appropriate as '(reading Ritti)'.

The late Peter Frei's unfinished corpus of the inscriptions of Dorylaion and Midaion and their respective territories in northern Phrygia was made available at a late stage through the offices of Christian Marek and Thomas Corsten. This enormous collection contains many unpublished texts. The names extracted from them have been entered in such a way as to allow their identification when this material is eventually published. For many of the inscriptions housed in the museum at Eski§ehir the inventory numbers recorded by Frei have been used, e.g. 'Unp. (Eski§ehir Mus.) A-2-94', but sometimes these are lacking. Frei also was able to copy a

number of inscriptions in a private collection in Eski~ehir, to which we refer as 'Unp. (Eski~ehir, Private Coll.)'. For many others, recorded in modern villages, the village name has been added as an aid to identification, e.g. 'Unp. (Frei, Avdan)', 'Unp. (Frei, Karapazar)'. The draft made available to us also includes a large number of texts from the northern part of the territory of N akoleia and smaller quantities described in less detail from some of the administrative districts of western Galatia, which appear here as e.g. 'Unp. (Frei, Sivrihisar district)'. In addition Frei made many improvements to the readings of personal names in previously published inscriptions, as well as recording the find-spots of stones which later found their way to the Eski~ehir museum without any note of their provenance; such instances are noted respectively as '(reading Frei)' and '(locn., Frei)'. vVe are indebted to Alan Cadwallader for drawing our attention to an inscription, so far not fully published, described and illustrated in his Fragments of Colossae: Sifting through the Traces (Adelaide, 2015) (non vidimus). He has also provided an advance copy of a paper publishing two further inscriptions from Kolossai (now published in Stone, Bones and the Sacred: Essays on Material Culture and Ancient Religion in honor of Dennis E. Smith (Atlanta, 2016).

The late 1\/Iaurice Byrne sent photographs and copies of unpublished inscriptions recorded by him at and around ancient Thiounta (modern Gozler). These are cited as 'Unp. (Byrne)' followed by the number of his provisional catalogue.

Michael \,Vorrle kindly provided his revised readings of the names of the ambassadors of Aizanoi sent to congratulate Septimius Severns in 195 AD (Oliver, Greek Constitutions 213). His corrections are indicated as '(reading Worrle)'.

Pisidia

We owe a particular debt of gratitude to Asuman Co~kun Abuagla. During her visit as LGPN academic visitor in 2013 she worked on the edition of the inscriptions of the Isparta :Museum, due to be published in the series Erganzungsbande zu den Tituli Asiae Minoris of the Austrian Academy. She kindly allowed us to make use of her work on new texts and enabled the verification of many old texts.

During his visit as LGPN academic visitor to Oxford in 201 S, in addition to being instrumental in facilitating contacts with Turkish epigraphists, Burak Takmer provided access in advance of publication to articles in the volume dedicated to the memory of Sencer ~ahin (Vir Doctus Anatolicus: Studies in Nlenwry of Sencer $ahin (Istanbul, 2016), in which new inscriptions from the region are published.

We are grateful to Claude Brixhe for providing the names from inscriptions published for the first time in Steles et langues de Pisidie (Nancy, 2016) in advance of publication.

Pontos and Armenia 111.inor

Timothy Mitford provided the sections on KabeiraNeokaisareia, Komana-Hierokaisareia, and Sebasteia extracted from his draft of Studia Pontica III (2), covering the eastern part of Pontos as far as the Euphrates. When published it will complete the epigraphic coverage of Pontos and Armenia Minor begun in 1910 by J. G. C. Anderson, F Cumont, and H. Gregoire. Mitford also made available the epigraphic :hapter of his East of Asia Minor: Rome's Hidden Frontier :Oxford, 2017), in which the inscriptions from Nikopolis and

Satala are presented, following the numeration to be employed in Studia Pontica III (2).

Thanks to Mustafa Adak we were able to see his and Christian Marek's Epigraphische Forschungen in Bithynien, Paphlagonien, Galatien und Pontos (Istanbul, 2016) in advance of publication.

Numismatics

Richard Ashton has once again acted as a general advisor on numismatic matters, among other things keeping us informed of newly attested names on coins for sale in the market. He also made available his important study of the late Hellenistic bronze and brass coinage of Apameia, due to be published in Kelainai-Apameia Kibotos. II, Une metropole achemenide, hellenistique et romaine (Bordeaux).

Christopher Howgego and Jerome Mairat allowed us to consult Roman Provincial Coinage. III, Nerva, Trajan and Hadrian (AD 96-138) prior to its publication in 2015.

Marguerite Spoerri provided a copy of the late Edoardo Levante's unfinished draft of Roman Provincial Coinage. VIII, Philip I.

William Metcalf checked and supplemented the short list of magistrates' names which figure on the coins of the second half of the third century AD, which will be included in Roman Provincial Coinage. X, Valerian to Diocletian ( AD 253-297).

Other Acknowledgements

The project is grateful to the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften for its continuing generosity in donating copies of new volumes of Inscriptiones Graecae to the LG P N library, and to Thomas Corsten for the annual gift of the latest Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum (SEC). For other donations we are grateful to Mustafa Adak, Alexandru Avram, Ferit Baz, Wolfgang Bli.imel, Dan Dana, Laurent Dubois, JeanLouis Ferrary, Miltiades Hatzopoulos, Bilge Hi.irmi.izli.i,Pantelis Nigdelis, Spyros Petrounakos, and Soren Sorensen.

For help and advice of a general or specific nature and for communicating newly published papers we would like to thank Mustafa Adak, Alexandru Avram, Frarn;:ois de Callatay, Domitilla Campanile, Sylvain Destephen, Armin Eich, Nuray Gi:ikalp, Christina Kokkinia, Guy Labarre, Ergi.in Lafh, Neil McLynn, Nicholas Milner, Philomen Probert, Eimear Reilly, Efthymios Rizos, Peter Thonemann, Soren Sorensen, Penny Wilson, and Michael Zellmann-Rohrer.

We are as ever grateful to Jonathan l\!Ioffett for his patience and help in resolving technical issues involving the LGPN database and the typesetting of the book. Sebastian Rahtz, the other digital architect of previous volumes, sadly died on 15 March 2016. Sebastian had long been an advocate of the radical transformation, now close to being realized, of LGPN's system of data storage and its associated working routines. This will see all its work conducted within the framework of a single XML database and will be a long-lasting memorial to his brilliance in the digital humanities.

As previously, it is a pleasure to acknowledge the administrative support received from the Classics Office in Oxford, as well as to express our thanks to Neil Leeder and Diggory Gray for providing day-to-day help and advice on matters relating to IT. Finally, we are grateful to Maggy Sasanow (Centre for the Study of Ancient Documents) for her contributions to the administration of the project and much other assistance.

This, the last of the three projected fascicles of Volume V, treats the regions of inland Asia Minor and this introduction has as one of its objectives the provision of the essential socio-historical background against which the onomastics of its constituent regions should be set. In this geographical space, for the first time in LGPN's coverage of the personal names of the ancient Greek world, not a single Greek city-state of the Archaic or Classical periods is to be found. 1 During the Archaic period, large parts of the region lay under the control of powerful indigenous centralized states, to begin with the Phrygians whose dominant role was briefly taken over by the Lydians before the Persians came to rule all of Asia Minor in the second half of the sixth century, a situation that remained essentially unchanged until the conquests of Alexander the Great. This was a multi-ethnic and multi-lingual landscape in which there was no one dominant culture. Some of its inhabitants were direct descendants of their second-millennium Luwian predecessors, while others such as the Phrygians, the Celts, and Italians were later newcomers from continental Europe. The non-Greek component (indigenous, Iranian, Celtic, Italian) among the names in this fascicle is correspondingly substantial, something which also characterized those regions treated in LGPN V.B where native culture remained resilient and/or hellenization made little impression until comparatively late. In the period before the Macedonian conquest, inland Asia Minor was a world in which large central places with urban functions were few and far between. Contacts with Greeks were very limited, mainly confined to exchanges in luxury goods and the trade in slaves, though the simultaneous adoption by Greeks and Phrygians of an alphabet sharing many of the same characters, based on the Phoenician script, does imply rather closer and more intimate relations. So, when Xenophon with the 10,000 accompanied Kyros the Younger on his journey to Mesopotamia in 401 BC, they were probably the first large body of Greeks, many of them from the Peloponnese and Central Greece, to set foot in the central and southern parts of inland Asia Minor before the Macedonians traced some of the same routes in 334-333 BC. No Greek inscription is known from any part of this vast land mass before the conquest. 2 Soon after those world-changing events, pioneering Greco-Macedonian settlements appeared in parts of Phrygia. Subsequently the Seleucid and Attalid kingdoms kept a great part of inland Asia Minor integrated into the wider Greek world, reinforcing the Greek presence in southern Phrygia and northern Pisidia through the foundation of cities (Laodikeia, Hierapolis, Apameia, Eumeneia, Apollonia, Antiocheia), some of which rose to great prominence and prosperity. Elsewhere the impact of cultural and political hellenization was felt to varying degrees in the third and second centuries BC. Situated on the fringe of the Greek world, Pisidian communities, though receptive to hellenizing influences, remained determinedly independent of external control until the first century BC. Celtic tribes migrating from the

' Vve are grateful to Simon Hornblower, Stephen lVIitchell, Robert Parker, Peter Thonemann, and Michael Zellmann-Rohrer for their constructive comments on earlier drafts of this Introduction. Vvefurther wish to emphasize that the bibliographical references cited here are intended as a guide to a wider literature and are by no means comprehensive.

Balkans occupied the north-eastern part of Greater Phrygia in the third century, controlling large territories from old centres of population, and were for a long time a destabilizing element in the geopolitics of western Asia Minor. In the northern and eastern parts of inland Asia Minor, dynasties of Iranian origin in Pontos (the Mithradatids, traceable from the end of the fourth century BC) and in Kappadokia (Ariarathes I, active at the time of the Macedonian conquest) ruled over vast territories where Iranian cultural influences were strong. Paphlagonia was divided among minor chiefdoms, the strongest centred on Gangra in the south, and frequently contested between the Bithynian and Pontic kings. Lykaonia and Isauria remained much more isolated and barely figure in any way in the Hellenistic period, in spite of the fact that a route of vital importance to the Seleucids led by way of the Kilikian Gates through Lykaonia to their possessions in western Asia Minor. By promoting large-scale urbanization on the model of the Greek city with its characteristic institutions, the conquest and rule of Rome firmly attached inland Asia Minor to the Greco-Roman Niediterranean world, and this was further promoted by the later spread of Christianity. It is on this latter stage in the onomastic history of these regions, and especially during the climax of the Roman ascendancy from c.100 to 300 AD, that the epigraphic and literary evidence throws the most intense light.

For the reasons summarized above, the original plan, enunciated in the Introduction to Volume I (pp. vii-viii), consigned inland Asia Minor to a second phase of the LGPN project which would concern itself with those parts of the ancient world which were largely untouched by Greeks and the Greek language until the conquests of Alexander: Syria, Palestine, Arabia, Egypt, and the trans-Euphratic regions, as well as what Fraser termed 'continental Asia Minor'. This policy was changed only when more detailed plans were being made for Volume Von Asia Minor between 2000-2. In the Introduction to LGPN V.A (p. x) it is stated that it was to be the first of three fascicles on Asia Minor, the third of which would treat the interior. However, the consequence of the earlier plan meant that no systematic work had been done on the basic compilation of the personal names for inland Asia Minor in the initial stages of the project, other than those found scattered among documents and texts relating to those regions covered by LGPN I-V.B. So when work on this fascicle began in earnest in late summer 2013, it involved working ab initio on a large body of epigraphic material for which there is relatively little coverage in the standard corpora of inscriptions, much of it being found in journal publications of the later nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Therefore, within the constraints of time imposed by the funding for its completion, the main thrust of our work has had to be directed at the basic compilation of the personal names.

Previous innovations in LGPN practices and conventions announced in the Introductions to LGPN V.A and V.B have

1 The cities treated in this volume of course fall outside the chronological scope of the Copenhagen Palis Centre's Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis (Oxford, 2004).

2 The only possible exception is the inscription on a rock tomb of Lykian type dated to the fourth cent. (Kokkinia, Boubon 91) in what was later the territory of Boubon in the Kabalis but less than 15 km from Lykian Symbra.

been adhered to in this fascicle. Therefore, bearers of the Roman tria nonzina with an Italian cognomen vvho were permanent residents in the region all find a place, all the more importantly in inland Asia l\!Iinor where a significant number of Roman colonies and new foundations contribute to an abundant and highly diverse collection of Italian names. "\i\Then attested in Latin, Italian names are transliterated into Greek; only very rarely is there no attested Greek form which allows a documented rendition of a name written in Latin; as always the Latin form is given in the final brackets. A very small number of Greek names has been drawn from inscriptions of the Hellenistic and Imperial periods written in Greek script in the Phrygian language, as well as inscriptions of Imperial date in Pisidian. The principles set out in LGPN V.B (p. xxviii) for the treatment of other non-Greek names are also followed. Indigenous Anatolian names and Lallnamen are neither accented nor aspirated, though manuscript traditions which supply one or other or both are recorded in the final brackets. No attempt is made to standardize the orthography of variations in the spelling of what is evidently the same name; each form appears under a separate heading. Where the nominative form has to be deduced from an oblique case, the attested form is recorded in the final brackets. Celtic names are treated in the same way as the indigenous names, while diacritics are applied to Iranian and Semitic names only when they are known from literary sources. The inherent difficulties that sometimes arise in determining whether a name should be treated as Greek or indigenous were elaborated at some length in LGPN V.B (pp. xxviii-xxix) and are equally valid here.

In his I<:.leinasiatischePersonennamen, which has remained for us a fundamental guide for the identification and treatment of Anatolian onomastics (see already LGPN VB p. xxx), Zgusta paid particular attention to the geographical distribution of personal names. 3 The main regional divisions (Phrygia, Lykaonia, Pisidia, etc.) adopted in his work largely coincide with those used in LGPN V.C. However, since his collection of names was mainly conceived as a work on Anatolian linguistics, his geographical arrangement of the material sometimes differs considerably from that followed in LGPN.+ The most significant difference in this respect is his use of transitional and border regions (Ubergangs- and Grenzgebiete). 5 Two cases may serve to illustrate his method. Zgusta placed the Anatolian names from the Kibyratis within a 'siidphrygischpisidisches Ubergangsgebiet' and those from the Killanion pedion, the Orondeis, Amblada, and Ouasada in a 'pisidischlykaonisches Ubergangsgebiet'. One of the reasons advocated for this practice was that it allowed users of his catalogue to assign names from these transitional areas to one region or another on linguistic grounds. 6 This kind of arrangement overlaps with an underlying problem in the study of Anatolian onomastics, which cannot be fully addressed here, that of the general difficulty of identifying Anatolian names as exclusively !saurian, Kappadokian, Phrygian, Pisidian, etc. on the sole basis of geographical criteria and more generally associating

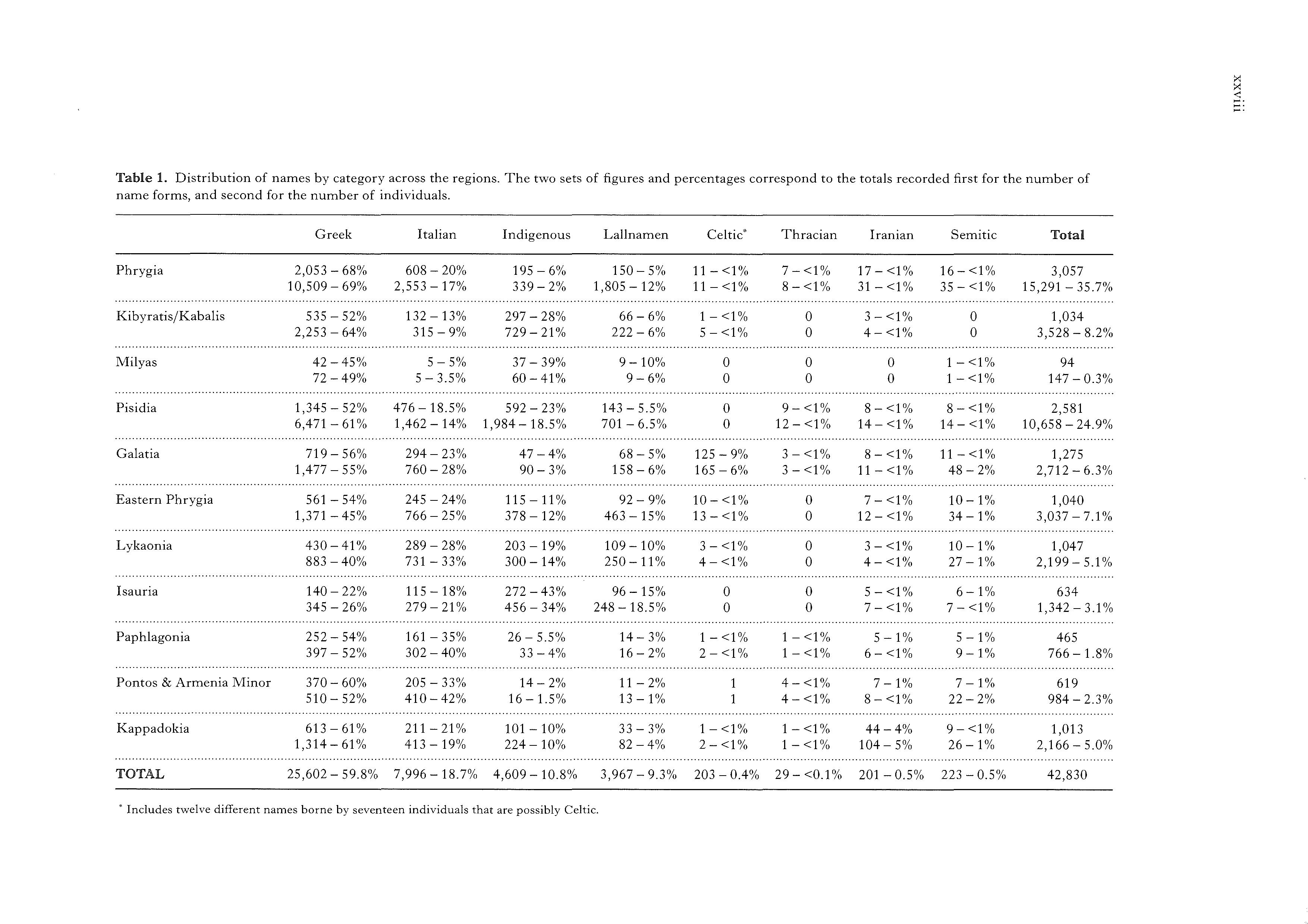

a stock of Anatolian names with ethnic designations used by historians of the Classical world. In this context it is worth stressing that the percentages given for the category 'indigenous names' in each region in Table 1 (p. xxviii) relate to a broad category of names rather than to names specific to each region (e.g. the figure of 43% for indigenous names in Isauria does not relate only to !saurian names).

The Contents of the Volume

The two previous fascicles of Volume V covered the coastal regions of Asia l\llinor, from Trapezous at the easternmost limit of Pontos to Kilikian Rhosos on the south side of the Gulf of Issos. Volume VC presents the personal names of the interior, from the westernmost parts-Phrygia, the Kibyratis and Kabalis, the Milyas, and Pisidia-to the central and eastern regions-Galatia, Eastern Phrygia, Lykaonia, Isauria, Paphlagonia, inner Pontos, Armenia Minor, and Kappadokia. This vast area, often referred to as Anatolia, covers approximately 300,000 km 2 and stretches more than 800 km from Laodikeia in the west to Melitene on the Euphrates in the east, and almost 550 km from northern Paphlagonia to the mountains of Isauria. 7 Geographically, inland Asia Minor is dominated by a high central plateau, for the most part between 900-1, 100 m above sea level, which incorporates most of Phrygia, Galatia, Eastern Phrygia, Lykaonia, and western Kappadokia. It is bordered to the north by the high mountain ranges of Paphlagonia and Pontos and to the south and east by the formidable barriers of the Taurus and Antitaurus in Isauria and eastern Kappadokia. These sharply divide the interior from the coast and form a natural obstacle to easy communications between the two. There are many remarkable and contrasting aspects to its landscape, from the upland lakes of northern Pisidia, to the flat steppe plain of Lykaonia, the great salt lake (Lake Tatta, modern Tuz Golii) in the centre, the eroded volcanic terrain of western Kappadokia, the lush river valleys of Pontos, the forests of Paphlagonia, and the inaccessible canyons of the Antitaurus, to name but a few. A continental climate of hot dry summers and harsh winters prevails on the plateau, but, surprisingly, this did not prevent the cultivation of the olive in certain favoured places, notably in the environs of Synnada and in upland Pisidia around Sagalassos. 8 Western Phrygia, the Kibyratis and Kabalis, the Milyas and Pisidia occupy transitional zones between the Anatolian plateau and their coastal neighbours along the Propontis, Aegean, and l\!Iediterranean, with which they were connected at most periods. It is, however, in Pisidia and the Kabalis that city sites are found at the highest altitudes; Sagalassos is situated above 1,500 m and the acropolis of Balboura is even higher at over 1,600 m. In the east the area covered in this volume does not extend beyond the river Euphrates into Armenia nor to the south of the eastern spur of the Taurus mountains into Kommagene, which will be treated in Volume VI.

Although this volume is the fruit of the joint work of the four co-editors, each has had the principal responsibility

.1 Zgusta, KP pp. 31-9; see also his distribution maps in Anatolische Personennamensippen (Prague, 1964).

• E.g. I onia is not used as a geographical division, so that Anatolian names found at Ephesos appear under Lydia (Zgusta, KP p. 34).

5 Border zones also figure in \1/aelkens, Tiirsteine pp. 240, 249, 275.

6 Zgusta, KP pp. 33--4.

7 A magnificent and wide-ranging synthetic study of inland Asia lVIinor, concerned primarily with the period of the Roman Empire until late antiquity, is to be found in the two volumes of S. lVIitchell's Anatolia. Land, JI/Jen,and Gods i11Asia Jl!Iinor (I, The Celts, and the Impact of Roman Rule; II, The Rise of the Church. Oxford, 1993).

8 See Jllfaeander Valley pp. 53-6. Strabo also mentions olive cultivation in other parts of Pisidia (xii 7. 1) and around Melitcne in Kappadokia (xii 2. 1).

for particular regions or parts thereof, as follows: Balzat: Pisidia, the Milyas, southern Lykaonia, and Isauria; Catling: Paphlagonia, Pontos with Armenia Minor, Phrygia (except for Laodikeia), northern Lykaonia, and Kappadokia; Chiricat: Galatia and Eastern Phrygia; Corsten: Kibyratis/Kabalis and Laodikeia in Phrygia. No further additions were made to the contents after the end of January 2017.

Each of the regions treated in this volume is described in what follows, with particular attention given to defining their borders. In addition, those aspects of their history and ethnic composition that influenced their onomastic profiles are summarized, together with any other background information deemed to be relevant. In some instances more detailed explanations are required to clarify problems specific to a particular region or city and their treatment here.

Phrygia

Phrygia is the westernmost of the regions of inland Asia lVIinor and as defined here describes a much more limited area than it had at its greatest extent in the early first millennium BC. 9 Until the arrival of the Celtic tribes in the third century it extended east as far as lake Tatta, over all the area later designated as Galatia where its old royal capital Gordion was located. 10 It also naturally included Eastern Phrygia, treated separately here for reasons set out below, and reached as far as lkonion, referred to by Xenophon (An. i 2. 19) as the furthermost city of Phrygia. The vast fortified city on Mt Kerkenes, perhaps to be identified as Herodotos' city of Pteria (i 76-9), situated on the frontier with Kappadokia, may have been a Phrygian foundation. To the north-west Phrygia also encompassed the southern shores of the Propontis (so-called Hellespontine Phrygia), but in spite of their encounters with the Greek colonial cities the inhabitants showed themselves surprisingly unreceptive to Greek culture. Hellespontine Phrygia has been treated in LGPN V.A as part of Mysia and Bithynia. At its greatest extent during the Early Iron Age and Archaic periods, Phrygia was a significant regional power in western Asia Minor, with a centralized system of administration, stratified society, and craft specialization (most visible in the monumental architecture and tumuli at Gordion and the rocktombs in the Phrygian Highlands), features which underlie Greek traditions about King Midas and the wealth of Phrygia. Although Phrygian supremacy eventually gave way to the Lydians in the late seventh century, it was only after the Persians had established control over western Asia lVIinor that there was a marked decline in social and economic complexity.

Phrygia in its reduced state was bordered to the west by Mysia, Lydia, and Karia, to the north by Bithynia, to the east by Galatia, and to the south by Pisidia. Conspicuous mountain barriers separate southern Phrygia from Karia and Pisidia, and again in the north divide the Tembris valley from the

Sangarios valley in Bithynia. But there is no such natural barrier between Phrygia and Galatia, nor with Eastern Phrygia. In the Tembris valley the division with Galatia may be placed around modern Beylikova to the east of Alpu, and further south by the upper reaches of the Sangarios; the territory of Amorion runs seamlessly into Eastern Phrygia, but further south there is a perceptible change of terrain from rolling hills to open steppe. In the south-west the Maeander and its northern tributaries separate Phrygia from Lydia, while further north its limits are marked by the transition from the upland plains and basins around Temenothyrai, Aizanoi, and modern Tav~anh to the more rugged and fragmented landscape of north-eastern Lydia and Mysia, where lie the headwaters of the river systems that flow towards the Aegean. 11 Within these boundaries, Phrygia comprises a patchwork of fertile upland basins and river valleys of varying extent, separated from one another by broken terrain and several high mountain ranges with peaks in excess of 2,200 m. The centres of human settlement all lie above 750 m, the majority between 900 and 1,100 m, the only exception being the Lykos valley in the south-west around Hierapolis, Laodikeia, and Kolossai.

Nucleated settlements are well attested in Phrygia from an early date. Herodotos (vii 30) in his account of Xerxes' march from Kappadokia to Sardis mentions Kelainai, the small city of Anaua (probably identical with Sanaos), and the much larger Kolossai, all of which had a long history of ancient occupation. Some eighty years later Xenophon (An. i 2. 6-7) also passed through the large, populous, and prosperous cities of Kolossai and Kelainai before taking a circuitous route via Peltai, the otherwise unknown Keramon Agora and Thymbrion, before reaching Tyriaion; an equally early history is possible for many other places attested later as cities. However, urbanization on the model of the Greek polis is not recognizable until after the lVIacedonian conquest, when a number of small cities populated at least in part by GrecoMacedonian settlers first emerges, sometimes bearing the name of their founders (e.g. Dokimeion, Dorylaion, Lysias, Philomelion, Themisonion); several other cities later boasted of their Macedonian origins (Eukarpia, Peltai; perhaps also Synnada). These were substantially reinforced by Seleucid city foundations in the third century, the most important being Laodikeia and Hierapolis in the Lykos valley, as well as the refoundation of Kelainai as Apameia. 12 Further Attalid foundations occurred in the second century (Dionysopolis, Eumeneia) and there is other evidence for the presence of military settlers at Amorion, Aizanoi, and Tyriaion in the late third and second centuries; an inscription dated to the years after 188 BC details the grant of polis status by the Attalid king Eumenes II to the inhabitants of Tyriaion, a mixture of Greeks, Galatians, and indigenous people. 13

In spite of their geographic isolation, there are some signs of interaction with Greek cities of the eastern Aegean; citizens

9 For an excellent summary account of the critical phases in the history of settlement and the hellenization of Phrygia, see P. Thonemann, 'Phrygia: an anarchist history, 950 BC-AD 100' in Roman Phrygia pp. 1-40.

10 This has the rather unfortunate result that all the names recorded from Hellenistic Gordion appear under the heading of Galatia, rather than Phrygia.

11 Strabo (xiii 4. 12) remarks on the difficulties of defining these borders.

12 For these eponymous city foundations of the Hellenistic period, see P. lVI. Fraser's detailed appendix in Greek Ethnic Terminology (Oxford, 2009) pp. 325-76 and, more generally, G. Cohen, The Hellenistic Settlements

in Europe, the Islands, and Asia 1Vli11or(Berkeley & Oxford, 1995) pp. 275326.

13 L. Jonnes and M. Riel, 'A New Royal Inscription from Phrygia Paroreios: Eumenes II Grants Tyriaion the Status of a po/is', Epigr. Anal. 29 (1997) pp. 1-30 = I Sultan Dag1 393. The spelling of the place-name found in the texts of Xenophon and Strabo has been adopted, even though the inscription cited indicates that its proper form, in the Hellenistic period at least, was Toriaion: see P.Thonemann, 'Cistophoric Geography: Toriaion and Kormasa', NC 2008, p. 48 and Zgusta, KO 1387-2.

of Laodikeia and Synnada appear in a list of proxenoi of Chios perhaps as early as the late third century, and the city of Peltai invites a judge from Antandros in the Troad to adjudicate a local dispute in the second century. 14 But it is only in the late second and first centuries that evidence builds for an emerging civic life conducted along Greek lines, the minting of coinage expressing city identity, and, most importantly for the recording of personal names, the development of the epigraphic habit. This relatively sudden and widespread development coincided with Phrygia's incorporation into the Roman province of Asia between 122 and 116 BC. From the mid-first century BC Italian negotiatores and their agents are widely attested, many of whom settled permanently in the region, thereby introducing an influential new strain of personal names. Apameia in particular was a centre for their activities, as a slave-market among other things. 15 Within this partially urbanized landscape, with a stable population and free from insecurity, the Romans had no pressing need to reinforce it with colonies or new foundations; the city of Sebaste was founded under Augustus through the synoikism of a number of villages, 16 and the city of Hadrianopolis in Phrygia Paroreios may also have replaced an earlier settlement (perhaps Xenophon's Thymbrion). At a much later date, some formerly dependent villages acquired city status. 17 Although most cities were physically small, Laodikeia and Hierapolis developed large urban centres and have much more in common with the cities of the coastal regions. The city elites, many of Italian origin, participated in the public life of the province, with members of the most prominent families becoming high priests of the provincial imperial cult, even from insignificant cities such as Alioi, Diokleia, Otrous, Stektorion, and the otherwise unknown Okokleia. However, it was extremely rare for these to reach the higher offices of the imperial administration and senatorial rank. Although Phrygia was primarily an agrarian society and economy, it was most famous for the marbles from the quarries at Dokimeion and in the Upper Tembris valley, under imperial control and procuratorial management, and the textiles produced at Hierapolis and Laodikeia. 18

Several cities often treated as part of Phrygia have previously found a place in some of its neighbouring regions. Thus, along the poorly defined western limits, Kadoi, Synaos, and Ankyra Sidera have been placed in Mysia while Blaundos was attached to Lydia, all covered in LGPN VA. However, following convention, the three cities of the modern Ac1payam valley (Eriza, Keretapa, and Themisonion) in the far south-west are included in Phrygia in spite of their closer geographical and cultural affinities with the Kibyratis and western Pisidia. Although the political geography of Phrygia has been well established in its essentials since the pioneering work of

1+ Chios: RPh 1937, pp. 327-811. 16-17; Antandros: Michel 542.

15 See JVIaeander Valley pp. 88-129.

16 In the list of cities attached to the conventus of Apameia, Sebaste appears as <P1t<µ,<<s o[ vvv lt<yoµ,<vo,I:</3aar17voi:C. Habicht, 'New Evidence on the Province of Asia', JRS 65 (1975) pp. 85-6; other villages perhaps included Babdalai, Dioskome, and Eibeos.

17 Soa, in the Upper Tembris valley, evidently acquired independence from Appia (J\IIAMA IX p. xvi with n. 15), while Orkistos in north-eastern Phrygia, formerly a dependency of Nakoleia, was granted po/is status by Constantine in 331 AD (MAMA VII 305).

18 lVIarble from the Dokimeion quarries was transported overland to Ephesos and exported to many parts of the Mediterranean: Robert, OJVIS VII pp. 71-121; BE 1984, no. 457; Fant, Cavum Antrum pp. 6-41; P. Pensabene,

Ramsay, Anderson and others, many small Phrygian cities which minted coinage cannot be firmly identified with sites on the ground (e.g. Akkilaion, Eriza, Hydrela, Keretapa, Lysias, Okokleia, Otrous, Palaiobeudos, Peltai, Siblia, Siocharax, Themisonion, Tiberiopolis), even if their approximate location can be determined. It is revealing that nine of the 21 cities and political communities listed in an Ephesian inscription of the Flavian period under the conventus of Apameia cannot be located and that three of the nine are only known from this text (Kainai Komai, the Ammoniatai and the Assaiorhenoi) .19 Part of the reason for this must lie in their small physical size and their lack of the monumental characteristics typical of a Greco-Roman city. Of the very much larger number of village names / ethnics attested epigraphically (well in excess of 150), only a small number can be identified with an archaeological site.

As a consequence, attributing inscriptions to a particular city, let alone a village, is fraught with uncertainties, especially when so many are found far from any central place. The situation in the Ac1payam valley is particularly acute; none of its three cities can be located with certainty. In this volume cautious identifications are made for Keretapa with remains at modern Ye~ilyuva at the north end of the valley, for Eriza with the prominent mound site at Karahiiyuk in the middle, and for Themisonion with a cluster of epigraphic finds in villages at its southern end (Dodurga, Kumaf~ar, Yumruta~ and i~kenpazar), in the knowledge that future discoveries may prove them wrong. 20 There is a similar difficulty concerning the exact location of Tyriaion in south-east Phrygia. It is often identified with modern Ilgm which probably preserves the name of ancient Lageina, a village possibly on the territory of Tyriaion. In spite of the uncertainties and for the sake of convenience, all the names from the inscriptions found at Ilgm and in its environs have been entered under the heading of Tyriaion. In north-west Phrygia, an impressive number of inscriptions comes from the Tav~anh basin, where no ancient city is known; prosopographical links and the style of the funerary monuments suggest that this formed part of the territory of Aizanoi and it is treated so in this volume. 21 Still further north, some inscriptions have been found in the area of modern Domani<; on the Rhyndakos, where Phrygia meets Mysia and Bithynia; in the absence of any ancient toponym, the few names involved appear under the heading 'Domani<; (mod.) (area)'.

Within Phrygia there were two cities called Hierapolis and two called Metropolis, to be differentiated as follows. The much smaller Hierapolis of the Pentapolis is designated 'Hierapolis (N.)' (i.e. Hierapolis (North)) to distinguish it from the great mercantile city of the Lykos valley, which appears without any further identifying markers. The Metropolis between Apameia

I manni nella Roma antica (Rome, 2013) pp. 360-87. Other quarries, such as those around Thiounta, supplied local demands (ibid. p. 390). Textiles: lVIaeander Valley pp. 185-90

19 C. Habicht (n. 16) pp. 64-91, esp. 80-7.

20 It should be noted that the personal names found in two inscriptions from modern Hisarkoy (BCH 24 [1900) p. 51), in an isolated location on the south-east slopes of lVIt Sal bake in the upper reaches of the modern Dalaman (:ay (the ancient Indos, marked on the Barrington Atlas [p. 65) as the Kazanes), which drains the Ac1payam valley, have been listed under the heading of Phrygia. One of the names, Arr17s, is common in the Kibyratis and suggests that the named persons should be associated with regions upstream rather than with Karia or Lykia.

21 JVIA1VIA IX pp. xix-xx.

and Synnada in southern Phrygia, is designated 'Metropolis (S. )', while its more northerly homonym, located in the socalled Highlands of Phrygia, is referred to as 'Metropolis (N. )'.

In most of the cities of Phrygia the Sullan era, starting in 85 BC, was used for dating purposes. This era was also in force at Aizanoi where the Actian era, starting in 31 BC, had previously been thought to apply. 22 An adjustment of fiftyfour years has therefore had to be made for the dated inscriptions of Aizanoi. This mainly involves the earliest group of pediment doorstones from Aizanoi (Waelkens Typ M, MAMA IX Type IV), many of which are dated. An upward adjustment of half a century has been applied to the undated inscriptions on the same type of doorstone, so that all are now ascribed to the second half of the first century AD rather than to the first half of the second century. No further revisions to the chronology of the later doorstones are required once the chronological overlap between the pediment stones and the earlier series of complete doorstones has been removed.

The Phrygians spoke an lndo-European language unrelated to the Anatolian family to which most of the other languages of Asia Minor belonged. Instead it is related to Greek and from the eighth to the third century BC was written in an alphabetic script which shares many letters with Greek, though it is only partially understood. It is likely that the Phrygians, like the Bithynians and, much later, the Galatians, were an intrusive population in Asia lVlinor from the southern Balkans, but it is far from clear when and under what circumstances they arrived. 23 Inscriptions in Old Phrygian are most numerous from the eighth to sixth centuries and their wide distribution, from Daskyleion in the north-west, to Kerkenes in the north-east and Tyana in the south-east, is an indicator of the extent of Phrygian influence across central Asia Minor. 24 The decline in social complexity of the later sixth century was accompanied by a decline in literacy and the rapid demise of the Old Phrygian script. 25 However, as a spoken language it survived among the Phrygian population in order to be revived in written form on a limited scale in Neo-Phrygian inscriptions of the second and third centuries AD, almost exclusively in the form of formulaic curses against the disturbance of a tomb appended to a standard funerary epitaph in Greek. 26 The distribution of these inscriptions seems to imply that the language did not survive in the whole of Phrygia. Most numerous in the east and south-east,

22 lVI. Worrle, 'Neue Inschriftenfunde aus Aizanoi II: Das Problem der Ara von Aizanoi', Chiron 25 (1995) pp. 72-5 revising M. Waelkens in Tiirsteine pp. 48-9 and MAIVIA IX pp. liv-lvi, and also W. Leschhorn, Antike Aren (Stuttgart, 1993) pp. 234-44.

23 Herodotos (vii 73) records a Macedonian tradition that the Phrygians had once inhabited a part of Europe adjoining lVIacedonian territory.

24 The Old Phrygian inscriptions have been published as a corpus: C. Brixhe and lVI.Lejeune, Co,pus des inscriptions paleo-ph rygiennes (Paris, 1984 ), with supplements in Kadmos 41 (2002) pp. 1-102 and 43 (2004) pp. 1-130.

25 A unique inscription in Phrygian dated c.300 BC is written in Greek, indicating that the Old Phrygian script was by then defunct: see P. Thonemann (n. 9) pp. 18-19.

26 There is no comprehensive, modern corpus of these inscriptions, which are most conveniently collected in 0. Haas, Die ph1ygischen Sprachdenkmiiler (Sofia, 1966) pp. 113-29 where 110 texts are listed; for some more recent finds, see C. Brixhe and lVI. Lejeune, 'Decouverte de la plus longue inscription neo-phrygienne: !'inscription de Gezler Koyil', Kadmos 24 (1985) pp. 161-84; C. Brixhe and T. Drew-Bear, 'Huit inscriptions neo-phrygiennes', in Frigi efrigio. Atti de/ 1" Simposio Internazionale, Roma, 16-17 ottobre 1995, edd. R. Gusmani, M. Salvini, and P. Vannicelli (Rome, 1997) pp. 71-114; C. Brixhe, 'Prolegomenes au corpus neo-phrygien', Bulletin de la societe de linguistique de Paris 94 (1999) pp. 285-315.

as well as throughout Eastern Phrygia and some of the northernmost parts of Pisidia, and to a lesser degree in the north of Phrygia, Neo-Phrygian texts are completely absent from the west half of the region where hellenizing tendencies were always strongest and most deeply rooted.

It is in Phrygia that some of the early Christian communities are documented in inscriptions for the first time. 27 The funerary monuments of several bishops can be dated to the latter half of the second century. 28 Most famous of these is the elaborate funerary epigram of Abercius, bishop of Hierapolis in the Pentapolis (SEC XXX 1479). 29 The name Apollinarios inscribed on the tomb of Philip the Apostle at the other Hierapolis, the city where he was martyred, has been tentatively identified with the bishop Claudius Apollinarius, known for his polemics against heretics and non-believers in the same period. 3° From the early third century, the so-called 'Eumeneian formula' (lurni ain0 1rpo,Tov fh6v, 'he shall reckon with God'), an addition to the familiar imprecations against disturbance of the grave, is appended to funerary inscriptions in southern Phrygia, predominantly by Christians and occasionally by Jews. 31 At much the same time in the Upper Tembris valley and adjacent areas of western Phrygia, Christians unambiguously proclaimed themselves on their gravestones as 'Xpwnavoi XpwnavoZ,' ('Christians for Christians'). 32

Kibyratis-Kabalis

The region called Kibyratis-Kabalis, as well as serving as a geographical term, is a cultural rather than a political entity, except for a period of about one hundred years from the early second until the early first century BC, when the territory of the so-called 'Kibyratan Tetrapolis' grouped together the cities of Kibyra, Boubon, Balboura, and Oinoanda. 33 The cultural ties between the four cities go back to the late third or early second century BC, when they were (re- )founded by 'colonizing' Termessians in the context of Pisidian expansion to the west. 34 It is unknown whether all were previously existing centres of habitation, but there were certainly small settlements, whose remains have been identified, at or close to the later cities. Politically, the Kibyratis-Kabalis is presumed to have been under nominal Seleucid control in the third century (perhaps amounting to no more than a Seleucid

27 Mitchell, Anatolia 2 pp. 37-43.

28 Two funerary monuments naming bishops of Temenothyrai are dated to the 180s: see S. Mitchell 'An Epigraphic Probe into the Origins of lVIontanism', in Roman Phrygia pp. 173-5 nos. 1 and 3. Slightly earlier are several dated Christian gravestones from nearby Kadoi, often treated as a Phrygian city: see MAIVIA X pp. xxxvi-xxxix.

29 See P. Thonemann, 'Abercius of Hierapolis. Christianization and Social Memory in Late Antique Asia lVIinor', in Historical and Religious Memory pp. 257-82 on the use of epigraphic material in the composition of the life of St Abercius.

30 See F. D'Andria, 'II santuario e la tomba dell'Apostolo Filippo a Hierapolis di Frigia', Rend. Pont. 84 (2011-12) pp. 3-61, esp. 53-4 on Apollinarios.

31 Robert, Hell. 11-12 pp. 399-413.

32 The texts are collected in Gibson, Christians.

33 Balboura 1 p. 78.

34 A reminiscence of the movement in Str. xiii 4. 17. See Balboura 1 pp. 62-7; T. Corsten, 'Termessos in Pisidien und die Griindung griechischer Stadte in "Nord-Lykien"', in Euploia. La Lycie et la Carie antiques. Dynamiques des territoires, echanges et identites. Actes du colloque de Bordeaux, 5, 6 et 7 novembre 2009, edd. P. Brun, L. Cavalier, K. Konuk, and F. Prost (Bordeaux, 2013) pp. 77-83.

claim), but the power vacuum towards the end of this century was exploited by the Pisidians, in particular from Termessos, to expand into the region. The newly founded or re-founded cities of the Kabalis must have been independent from Seleucid rule, as they were not incorporated into the Attalid kingdom after the peace of Apameia. In Imperial times, however, the southern part of the region, comprising Boubon, Balboura, and Oinoanda, was attached to the province of Lycia when this was established in 43 AD, whereas Kibyra remained in the province of Asia to which it had belonged since about 84 or 82/1 BC. 35

The designations ancient writers employed for this region are not always entirely transparent. Thus, Strabo distinguishes first Kibyra and the Kabalis, but later establishes a connection between the two by reporting that the Kabalis was occupied by the Kibyratans. He names Pisidia, the Milyas, Lykia, and the Rhodian Peraia as the regions surrounding Kibyra, unless he is speaking of the Kibyratan Tetrapolis at that point; for, even if probable, it is not obvious whether Strabo counts Boubon, Balboura, and Oinoanda as Kabalian cities or not. 36 Ptolemy, on the other hand, follows the Roman provincial boundaries and, consequently, separates Kibyra, which he places in 'Greater Phrygia', from Boubon, Oinoanda, and Balboura, which constitute the Kabalis. 37

The boundaries of the Kibyratis-Kabalis and those of its four cities cannot be determined in every detail and anyway are likely to have changed over time; therefore we adhere to what is believed to have been the situation in the Imperial period to which most of the personal names belong. 38 The western border with Karia is clearly marked by the Indos and Kazanes valleys and the formidable Salbake mountain range, while the remaining borders are best defined by the territorial limits of its four cities. The territory of Kibyra consists mainly of two large valleys, one in which the city itself is located and another to its north-east containing a large private estate, centred on the village of Alassos. 39 Inscriptions from this latter valley include lengthy lists of the farming population from the second and third centuries AD, yielding 818 named individuals. A narrow defile to the north-west of Kibyra gives access to the plain of modern Ac1payam, here treated as part of Phrygia, which, at least in its southern section, may have belonged to Kibyra in the Imperial period. Lagbe, at the eastern end of the Kibyra valley, was perhaps an independent city in the Hellenistic period, but since fines for the violation

.15 The status of Boubon, Oinoanda, and Balboura between 84 BC and 43 AD remains a vexed issue: SEC LV 1452; Xanthos 10 pp. 99-107; Balboura 1 p. 123. For the date of 82/1 BC for the abolition of the Kibyratan Tetrapolis, see !VI.Vitale, 'Kibyra, die Tetrapolis und IVIurena: eine neue Freiheitsara in Boubon und Kibyra?', Chiron 42 (2012) pp. 551-66.

.1, Str. xiii 4. 14--17. J. J. Coulton, in Balboura 1 p. 10, assumes that, for Strabo, 'the territory of these four cities constituted the whole of, or more probably a large part of, a district called Kabalis'.

.17 Ptol. v 2 (Kibyra) and v 4 (Kabalia).

.1s See Balboura 1 pp. 1 and 10-11 with fig. 1.9 (p. 13).

.19 For the location of Alassos near the modern towns of Karmanh and Tefenni, see T. Corsten, T. Drew-Bear, and !VI.Ozsait, 'Forschungen in der Kibyratis', Epigr. Anat. 30 (1998) pp. 50-7.

40 Balboura 1 p. xxii (modern names) and pp. 28, 30-1, and 98. A. S. Hall and J. J. Coulton, 'A Hellenistic Allotment List from Balboura in the Kibyratis', Chiron 20 (1990) p. 128 n. 15, suggest that Lagbe was already under Kibyra's control in the Hellenistic period.

41 N. P. IVIilner, in Balboura 2 pp. 412-13, seems to count it under Balboura, whereas Coulton assigns it to the territory of Kibyra (see, e.g., his fig. 1.2 in Balboura 1 p. 2).

of tombs were payable to Kibyra in the Imperial period, it is taken here to have been a dependent town. 40 The area with the rock-sanctuary of the Dioskouroi at Kozagac1 to the southeast of the city, as 1.vell as the environs of modern Golci.ik and K1z1lbel, are all assigned to the territory of Kibyra, 41 this last being the only departure from Coulton's definition of Balbouran territory. 42 Boubon was the smallest city in the Kabalis and also had the least extensive territory. 43 In spite of their geographical location on the fringes of the plain of Elmah, which forms the core of the l\!Iilyas, the villages of Orpenna and Elbessos had become dependent on Oinoanda in the Imperial period. 44 As everywhere in inland Asia Minor, the epigraphic evidence dates very largely from the Imperial period and exhibits a predictable dilution of the indigenous onomastics. However, the long allotment list from Balboura of the later Hellenistic period contains some 320 named individuals, the vast majority bearing Anatolian names, many of which reveal a close connection with Pisidian Termessos. 45 A similar pattern of naming is likely to have prevailed in the other cities of this region, where names of Pisidian origin continue to be comparatively frequent in the Imperial period. On the other hand, there are no names that can be attributed with certainty to the Lydian or the obscure Solymian languages, which, according to Strabo (xiii 4. 17), were spoken in the Kibyratis in addition to Greek and Pisidian. 46

Milyas

The Milyas, and the Anatolian people called the Milyai or l\llilyeis, are mentioned several times in connection with the Kabalians, Lykians, and Pamphylians by Herodotos (i 173; iii 90; vii 77). Where exactly these Milyai were settled and the extent of the land they occupied is uncertain and likely to have varied over time.47 Following the treaty of Apameia in 188 BC, the Attalid king Eumenes II was granted a large portion of inland Asia Minor, including Greater Phrygia, L ykaonia, and the Milyas (Plb. xxi 46. 10). At that time the Milyas might have encompassed a large area directly to the west of the Pisidian communities (Termessos, Kremna, Sagalassos), extending from the plain of modern Elmah (ancient Akarassos) as far north as the lake of Burdur. 48 In this volume the Milyas describes a much more restricted space, confined to the small cities and communities of the Elmali plain, leaving the Lysis valley and the Bozova plain as far as Isinda in Pisidia. 49

42 Balboura 1 pp. 26-31 and 80-3; see the map with the putative territory of Balboura on p. 2 (fig. 1.2) and that delineating the borders between the four cities of the Tetrapolis on p. 27 (fig. 2.11 ).

43 Kokkinia, Boubon pp. 12-14.

44 Xanthos 10 pp. 114-20 with figs 40 and 41; Balboura 1 pp. 29-30, cf. p. 27 fig. 2.11.

45 A. S. Hall and J. J. Coulton (n. 40) pp. 130-2; cf. Balboura 1 pp. 65-7.

46 It is not clear what relationship Lydian names such as Kaooas and Kaows (LGPN V.A svv.) have with Ka8aas, Kaoaos, Kaoaovas, Kaoavas, and Kaoovas, names which are attested in the Kibyratis-Kabalis and neighbouring parts of Pisidia. Complex names with Kao- as the first root element, as well as simple names, also occur in Isauria.

47 The evidence is discussed in detail in A. S. Hall, 'R.E.C.A.lVI. Notes and Studies No. 9: The lVIilyadeis and their Territory', Anat. Stud. 36 (1986) pp. 137-57. Several inscriptions bearing on the geography of the area have recently come to light and are treated by D. Rousset in Xanthos 10 pp. 6-12 no. 1 and pp. 135-52 nos. 4-6.

.,s Str. xiii 4. 17 and A. S. Hall (n. 47) pp. 142-52.

49 In an inscription from the L ysis valley the 'IVIilyadeis and the Roman businessmen living among them and the Thracians settled among them' are

Orientated on a south-west-north-east axis, this narrow upland plain borders two powerful neighbours, which competed for control of it.so To the north-west, it adjoined the territory of Oinoanda, and on its southern side, Lykia. To the north-east a defile connects to the plain where the Pisidian city of Isinda lay. 51 The treaty between the Lykian confederation and Rome in 46 BC reveals that Choma, the main polis of the Milyas, and smaller communities like Elbessos, Akarassos, Terponella, and Kodopa, belonged to the Lykian confederation, while in the time of Claudius Choma, Podalia, Kodopa, Akarassos, and Soklai are mentioned as stations on the stadiasmus of the province of Lykia. 52 These small communities are here treated as independent cities, in spite of the uncertain political status of many of them. Even though the number of individuals recorded from the Milyas is small (147 entries), the indigenous component in the personal names is instructive as to their affiliation with their Pisidian rather than their Lykian neighbours.

Pisidia

Pisidia is the highland region that derives its name from the ancient Pisidians, an Anatolian population of Luwian origin. It stretched from the edge of the Pamphylian plain to the lakes of Burdur, Egridir, and Bey 9ehir on the fringes of Phrygia. 53 In the Hellenistic period, the Pisidians were divided among independent communities in settlements that were usually fortified and mostly located above 1,000 m (Termessos, Selge, Kremna, Sagalassos, etc). In this volume, Pisidia also encompasses, to the north of the lakes, Apollonia/Sozopolis, Antiocheia towards Pisidia (1rpo,IIwio{av) and the Killanion pedion, which all had close cultural links with Phrygia. On its eastern side the Sultan Dag1 and the Erenler Dag1 form natural mountain barriers separating Pisidia from Phrygia and the Lykaonian plain. The Orondeis, including Pappa-Tiberiopolis and MistiaKlaudiokaisareia, as well as Ouasada, are therefore placed within Pisidia. 54 Along the upper reaches of the river Melas, the Pisidian strongholds of Kotenna and Etenna command the borders with Kilikia and Pamphylia. Its western limits extended north from Termessos to Isinda, the Roman colony

found dedicating a monument to Rome and Augustus (text published and translated by A. S. Hall. [n. 47] p. 139). Note the veteran of Legio VII (do1110 Nfilyada) attested in an epitaph from Dalmatia (CIL III 8487 with observations by S. Mitchell, 'Legio VII and the garrison of Augustan Galatia', CQ 27 [1976] p. 304). Recorded here under the Milyas this veteran may have been from the group of lVIilyadeis attested in the Lysis valley under Augustus. See also a man with the ethnic Mv,\,\d, in the Hellenistic allotment list of Balboura (SEGXL 1268 C, 33).

5

° For its location, see Stadiasmus map 3 and Xanthos 10 figs 41 and 43.

51 A. S. Hall (n. 47) pp. 148 and 151 makes a distinction between the Lykian lVIilyas and the Pisidian lVIilyas, which, although useful, is supported by no textual evidence.

52 SEG LV 1452, 54, 58-9 (treaty) and Stadiasmus p. 39 11. 35-42. As indicated above, Elbessos and Orpenna were dependent communities in the territory of Oinoanda during the Imperial period.

53 For a physical description of Pisidia, see X. de Planhol, De la plaine pa111phylien11eaux lacs pisidiens. Nomadisme et vie paysanne (Paris, 1958) pp. 23-64.

54 For the Killanion pedion and the Orondeis, see Robert, Hell. 13 pp. 73-94.

55 This ha_sbeen identified, probably incorrectly, with Keretapa/Diokaisarea by L. Robert, Villes pp. 105-21; 318-38; contra von Aulock, NISPhrygiens 1 pp. 65-70 and J. Nolle, 'Bcitr,ige zur kleinasiatischen Miinzkunde und Geschichte 6-9', Gephyra 6 (2009) p. 54 n. 289.

of Olbasa, and as far as an ancient site near modern Ye 9ilova, on the eastern shore of the Salda lake. 55 Pisidians first appeared in Greek sources when Kyros the Younger launched an attack against them after they had ravaged the Persian king's territory (X., An. i 1. 11 and HG iii 1. 13). During the Hellenistic period Pisidian cities are evoked mainly for their military strength in historical accounts of warfare, s6 and the warlike reputation of the Pisidians is reflected in their regular appearance among the mercenaries of the Hellenistic kings. 57 Thracian names attested in the region in the Imperial period are likely to originate in the settlement of Thracian soldiers on its margins (in the Lysis valley, at Apollonia, and in the Killanionpedion) by the Seleucid kings_ss Around 200 BC the dynamism of the Pisidian communities is demonstrated by the involvement of the Termessians in the (re-)foundation of Kibyra, Oinoanda, and Balboura in the Kabalis. 59 The first Roman to march through Pisidia was the consul Manlius Vulso on his way to Galatia in the aftermath of the battle of Magnesia in 189 BC (Liv. xxxviii 15). During the second and first centuries BC large-scale public buildings (paved agoras, temples, bouleuteria, heroons, stoas) appeared in many Pisidian cities. 60 In the second century BC Greek inscriptions also show some of these cities to have been wellorganized independent communities with a developed civic life based on characteristic Greek political and social institutions. 61 The Orondicus Tmctus, an area of land north of the city of Mistia, was incorporated in the ager publicus during the campaigns of Servilius Isauricus in the 70s BC. Pisidia became part of the Roman province of Galatia in 25 BC following the death of Amyntas who had been installed as king fourteen years earlier by Marcus Antonius (App., BC v 75). Later, perhaps as early as 43 AD, most of Pisidia was attached to the province of Lycia-Pamphylia, though Apollonia and Antiocheia remained in Galatia. 62 The early Imperial period is marked by the foundation of Roman colonies at Antiocheia, Komama, Kremna, Olbasa, and Parlais under Augustus, at PappaTiberiopolis under Tiberius, and at Mistia-Klaudiokaisareia under Claudius, some of which were connected by the Via Sebaste built in 6 BC. 63 These Roman foundations account for

56 S. Mitchell, 'Hellenismus in Pisidien', in Forschungen in Pisidien, ed. E. Schwertheim (ANIS 6. Bonn, 1992) pp. 4-6.

57 Launey 1 pp. 471-6.

58 Onom. Thrac. p. !iii.

59 T. Corsten (n. 34) pp. 77-83.

60 S. Mitchell (n. 56) pp. 7-20.

61 Robert, Documents p. 53 (Termessos, 281 Be); TANI III (1) 2 (Termessos and Adada, second cent. Be); IBurdurNius 326 (Olbasa, 159-158 BC).

62 For the administrative organization of the area under Rome, see G. Arena, Citta di Panfilia e Pisidia sotto il do111inioromano (Catania, 2005) pp. 35-47; H. Brandt and F. Kolb, Lycia et Pamphylia. Eine romische Provinz im Siidzuesten Kleinasiens (lVIainz, 2005) pp. 20-6. For Sagalassos, see VI. Eck, 'Die Dedikation des Apollo Klarios unter Proculus, legatus Augusti pro praetore Lyciae-Pamphyliae, unter Antoninus Pius', in Exempli gratia. Saga lassos, JYiarc TVaelkens and I11terdiscipli11aryArchaeology, ed. J. Poblome (Louvain, 2013) pp. 43-9.

63 B. Levick, Roman Colonies in Southern Asia JYiinor (Oxford, 1967); A. De Giorgi, 'Colonial Space and the City: Augustus' Geopolitics in Pisidia', in Roman Colonies in the First Century of their Foundation, ed. R. J. Sweetman (Oxford, 2011) pp. 135-49. For the milestones of the Via Sebaste, see D. H. French, Roman Roads and Milestones of Asia JY[inor. 3, Nfilestones. 3.6, Lycia-Pamphylia (BIAA Electronic Monograph 6. Ankara, 2014) pp. 26-45 (http://biaa.ac. uk/publications/item/name/electronicmonographs).

the large number of Roman names, including some rare nomina gentilicia, attested in Pisidia. 64 Under the empire individuals from local elite families regularly pursued equestrian and senatorial careers. 65 The troubles of the middle and late third century AD, marked in Pisidia by the Roman siege of Kremna in 278 AD and more widespread brigandage, encouraged the greater involvement of local men in Roman military careers. 66

The bulk of the epigraphic evidence dates to the first three centuries of the Imperial period, coinciding with the most intense period of public construction in the region. An exceptionally large number of names (more than 4,500 out of the 10,658 registered in Pisidia as a whole) has been preserved from Termessos, the great majority inscribed on sarcophagi and other funerary monuments of the second and third centuries AD, which often record the names of several generations of ancestors. 67 Another substantial and coherent body of material comes from the territory of the Roman colony of Antiocheia, where the sanctuary of Men Askaenos with its Ionic temple dating from the second century BC has yielded abundant epigraphic evidence in the Imperial period, mainly in the form of dedications in Greek and Latin (c.350 individuals). At two locations on the territory of Antiocheia, as many as forty-five inscriptions, many of them fragmentary, which list the contributions of a cult association, have produced the names of c.600 of its members entitled the Xenoi Tekmoreioi.

68 Around 130 different ethnics, mostly of villages, are attested in these lists. Few of these villages can be located, though they were presumably not very far from Antiocheia, either in northern Pisidia or south-eastern Phrygia; the many unlocated ethnics appear under the heading 'Phrygia (S.E.)Pisidia (N.)'. 69 Also noteworthy in the epigraphy of the Imperial period are the inscriptions in a 'Pisidian' language written in Greek script, mainly from the area of Tymbriada, from which those individuals bearing Greek names have been included in this volume. 70

Galatia

Galatia comprises the northern part of the Anatolian plateau, which, until the early third century BC, had been part of Greater Phrygia. 71 To the west it borders with Phrygia, to the north with the south-eastern tip of Bithynia, Paphlagonia, and

64 See 0. Salomies, 'Roman names in Pisidian Antioch. Some Observations', Arctos 40 (2006) pp. 91-107.

65 For an illustration of this process of integration, see H. Devijver, 'Local Elite, Equestrians and Senators: a Social History of Roman Sagalassos', Anc. Soc. 27 (1996) pp. 105-62.

66 S. l\/Iitchell, 'Native Rebellion in the Pisidian Taurus', in Organised Crime in Antiquity, ed. K. Hopwood (London, 1999) pp. 155-7 5; K. Hopwood, 'Greek Epigraphy and Social Change. A Study of the Romanization of SouthWest Asia Minor in the Third Century AD', in XI Congresso Internazionale di Epigrafia Greca e Latina. Roma, 18-24 settembre 1997. Atti, II (Rome, 1999) pp. 428-31; ICentPisid 29 and 105.

67 Among these funerary monuments some belonged to families composed of freed individuals and ol,dra, (e.g. TANI III (1) 338, 421, 429, 485, 772). To avoid splitting family groups, freedmen and olKera, of Termessos have consistently been entered under the heading 'Termessos". For Termessian onomastics, see 0. van Nijf, 'Being Termessian: Local Knowledge and Identity Politics in a Pisidian City', in Local Knowledge and Niicroidentities in the Imperial. Greek World, ed. T. Whitmarsh (Cambridge, 2010) pp. 163-88.

68 Most of the lists were published by W. M. Ramsay and J.R. S. Sterrett. For a new fragment, see C. Wallner, 'Xenoi Tekmoreioi. Ein neues Fragment', Epigr. Anal. 49 (2016) pp. 157-75.

western Pontos, to the east with north-western Kappadokia, and to the south with Eastern Phrygia. None of these boundaries are very securely fixed. 72 The divide with Phrygia is marked largely by the upper course of the Sangarios, which runs between the territory of Pessinous on the Galatian side and those of Nakoleia, Orkistos, and Amorion on the other (for further detail seep. ix above). Towards the north-west, the river Hieros/Siberis separated Galatia from luliopolis and Bithynia, while to the north the modern Terme <;::ayperhaps divided it from Paphlagonia. Further to the north-east the boundary with Pontos is placed in this volume along a line running to the south of modern Sungurlu and Alaca, assuming a large territory for Pon tic Amaseia. To the east the border lies between the small Galatian cities of Kinna and Aspona and the equally small Kappadokian city of Parnassos, at the top of lake Tatta. However, it is much less clear how far the territory of Taouion extended to its east and south; a rather arbitrary line has been drawn between Lake Tatta north-east to modern Yerkoy and Sorgun. The southern boundary is equally ill-defined. The region of Haymana very likely formed part of the territory of Ankyra but further south the central plateau with its great estates lay outside its jurisdiction. A line, north of modern Kozanh, Kerpis;, and Emirler, where the first evidence for these estates appears, is used to demarcate Galatia and Eastern Phrygia (see below p. xvi for further detail).

The region derives its name from the Galatians, a Celtic people, who, after crossing from Europe into Asia Minor in 278/7 BC and causing havoc among the cities of western Asia Minor, settled in north-eastern Phrygia by the end of the 60s. In the Hellenistic period the main urban centres were, from west to east, the temple-state of Pessinous (the centre of an ancient Phrygian cult of Kybele), the old Phrygian capital of Gordion, destroyed by Manlius Vulso in 189 BC, and the trading centre of Taouion. 73 It therefore comes as a surprise to find seventy-seven individuals buried at Athens bearing the ethnic 'AyKvpav6,/f1 who are dated to the Hellenistic period, when other evidence suggests that Ankyra was not yet a polis. Outside the urban centres, the Galatians clung to their tribal organization, exercising control over their territories from small fortified strongholds.

74 Following the death of its last king Amyntas in 25 BC, Augustus annexed his kingdom and established the province of Galatia. He founded three urban communities, the Sebasteni Tolistobogii Pessinuntii,

69 Out of the many variant spellings of the same ethnic that occur in these lists (e.g. To.A,p.<TEVS,TaA<<p.<T'7Vos,To.A<p.<TT'7Vos), a 'standard' form has been adopted under which all those from that place are registered (in the above case 'Talimeteis' was chosen).

70 Brixhe, Steles.

71 For the history of the Galatians in Anatolia, see Mitchell, Anatolia l pp. 11-58; K. Strobel, Die Galater: Geschichte und Eigenart der keltischen Staatenbildung auf dem Boden des hellenistischen und romischen Kleinasien. I, Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und historischen Geographie des hellenistischen und romischen Kleinasien I (Berlin, 1996); and, for more recent bibliography, references in A. Co~kun, 'Histoire par les noms in Ancient Galatia', in Personal Names in Ancient Anatolia, ed. R. Parker (Oxford, 2013) pp. 79-82.

72 Cf. K. Strobel, 'Galatien und seine Grenzregionen. Zu Fragen der historischen Geographie Galatiens', in Forschungen in Galatien, ed. E. Schwertheim (Bonn, 1994) pp. 30-65.

73 Hellenistic Pessinous: P. Thonemann, 'Pessinous and the Attalids: A New Royal Letter', ZPE 194 (2015) pp. 125-6; Hellenistic Gordian: P. Thonemann (n. 9) pp. 20-1; Taouion: Mitchell, Anatolia l pp. 51-4.

7+ For a gazetteer of Galatian fortresses, see INGalatia pp. 25-7.

the Sebasteni Tectosages Ancyrani, and the Sebasteni Trocmi Taviani, incorporating the lands of the Galatian tribes into a civic organization. 75 Not far to the north of Pessinous he also founded the Roman colony of Germa. However, the largest of the Augustan foundations was Ankyra, the capital of the new province. 76 North-west of lake Tatta, the small settlement of Kinna acquired the status of a polis perhaps during the early second century AD. 77 A little further east, close to the border with Kappadokia, was another small city, Aspona. In the north-west, in a fertile region between the lower Tembris and Sangarios, a group of seven villages comprised the Konsidiana choria, a private estate which by the second century AD had become imperial property; another private estate, belonging to the family of the Plancii of Perge, was located a little further north in the same general area. 78 Since the inscriptions from these estates contain significant numbers of Celtic names, they have been treated as parts of Galatia.

The Celtic language of the Galatians apparently remained in use in spoken form, perhaps until the late sixth century AD. 79 All the epigraphic documentation, as elsewhere, is in Greek or Latin and almost exclusively of Imperial date or later. However, a significant number of names in these inscriptions, as well as in the literary sources relating to the Hellenistic period, can be identified as Celtic. 80 The names recorded in the literary sources, which belong to members of the Galatian ruling class in the Hellenistic period, are almost exclusively of Celtic origin, suggesting that the nobility did not intermarry other than with members of other dynastic families of Asia Minor. 81 A different pattern emerges from the inscriptions of the rural hinterland, showing Celtic names to have been current in families which also favoured names of Phrygian, Greek, and Italian origin. 82

Eastern Phrygia

Eastern Phrygia is a term used to refer to the tract of land comprising the territory of Laodikeia Katakekaumene and

75 The creation of these cities was probably simultaneous, despite slightly different foundation dates extrapolated from local eras: see IVIitchell, Anatolia 1 p. 87.

76 For the borders of the Galatian cities, see INGalatia, pp. 19-22 and Mitchell, Anatolia 1 pp. 87-8.

"MAMA XI p. xxvii; TIE 4 pp. 189-90.

78 For these estates, see IVIitchell, Anatolia 1 pp. 152-3. The Konsidiana choria had become an imperial estate as early as the reign of Hadrian. The property of the Plancii was acquired during the Julio-Claudian period, perhaps by the senator !VI.Plancius Varus himself.

79 S. Mitchell, 'Population and the Land in Roman Galatia', in ANRTY II 7.2 (1980) p. 1058. This is attested in Luc., Alex. 51; St Jerome, Comm. in ep. ad Galatas 2. 3; Cyr. S., V Euthym. SS (after 543 AD).

80 X. Delamarre's Noms de personnes celtiques dans l'epigraphie classique (Paris, 2007), ,vhich covers the Celtic personal names attested in Europe, has been a valuable point of reference in identifying some of the less distinctively Celtic names. vVhenever a Galatian name finds a counterpart in the Celtic West, a reference to Delamarre's book has been added, and where necessary to the list of roots found at its end. But, given the limitations in our knowledge of the indigenous languages, Phrygian in particular, these references should not always be taken as decisive.

81 S. Mitchell (n. 79) p. 1057 with n. 17.

82 See also A. Co~kun (n. 71) pp. 100-1 on the distribution of Celtic names in the hinterland.

83 It has been employed inter alias by W. M. Calder in l\lIAJ\IIA I and VII for a rather wider area, by L. Zgusta in his JQeinasiatische Personennanzen P- 38 (Ostphrygien) and by C. Brixhe in his Essai sur le grec anatolien au debut de notre ere (2nd edn, Nancy, 1987) (Phrygie Orientale). The treeless steppe is equivalent to the region referred to under the headings of the Axylon and Laodikeia Katakekaumene in l\lJAJ\IIA I pp. xv-xvi and XI pp. xxiv-xxvi (see

the treeless steppe to its north, 83 which on various grounds could equally have been treated as part of either Phrygia or Galatia. There are, however, sound geographic, historical, cultural, and practical reasons for treating it separately from these two regions. It forms the westernmost part of the arid Anatolian steppe plateau, with a long history of pastoralism, 84 distinct from the patchwork of mountains and plains characteristic of much of Phrygia. In the late Hellenistic period a part of it may have been ceded to the Galatians and included in what Ptolemy called the Proseilemmene, 'the added land', and under the Roman Empire it was administered as part of the province of Galatia, whereas the rest of Phrygia lay within the province of Asia. 85 The small town of Ouetissos, close to its northern limit, was included among the poleis of the Galatian Tolistobogioi by Ptolemy. 86 However, this region presents a number of Phrygian cultural markers during the Imperial period which set it apart from Galatia. Not only do Neo-Phrygian inscriptions occur throughout but it preserves a stock of personal names, including some of its most common, which can plausibly be identified as Phrygian. 87 Door-stone funerary monuments, typical of so much of Phrygia, are also found in good numbers, but they also occur over a much wider area, including Galatia. Not surprisingly, it has been characterized as a Phrygian-Galatian transitional zone. 88 Unlike neighbouring regions Eastern Phrygia remained largely non-urbanized throughout antiquity. Laodikeia, a Seleucid foundation at its southern edge, and Ouetissos, insignificant enough for its exact location to remain unknown, are its only cities. 89 In the Imperial period it is essentially a zone of villages (e.g. Gdanmaa, Pillitokome, Selmea) and large estates whose owners along with their freedmen and other agents often figure in the inscriptions. Initially these estates were privately owned but by the second century some of them had become imperial properties. 90 The Sergii Paulli of the Roman colony of Antiocheia in Pisidia owned a large estate near

below n. 88). Other authorities have treated it as part of Lykaonia, e.g. L. Robert in 1Vo111sindigenes passim.

" Strabo (xii 6.1) reports that king Amyntas had owned three hundred herds of animals in the plain of Lykaonia: Mitchell, Anatolia 1 p. 148.

85 See Plin., HN v 25 and Ptol. v 4. 8 with Mitchell, Anatolia 1 pp. SS and 148. According to K. Strobel (n. 72) pp. 56-7, the Proseilemmene was assigned as a regio attributa to the territory of Ankyra in 25/4 BC and then to the territory of Kinna during the Antonine period: see also Der Neue Pauly 10 col. 437 s.v. Proseilemmenitai.

86 Ptol. v 4. 5. A few Galatian names occur in Eastern Phrygia, mostly in the area of Ouetissos and at Laodikeia: B<AAa, BpoyopEL,, Bwi3op,,, I'avi3aTO<;, Erroaaopi,;, Kaµµa, Karµapo,, and Kovf3anaKo<;.