T heories = Tools

of society must be empirical. That is, information should be based on observations, experiments, or other data collection rather than on ideology, religion, intuition, or conventional

sociology as the scientific study of two aspects of society: social statics and social dynamics. cial statics investigates how principles of social order explain a particular society, as well as the interconnections between institutions. dynamics explores how individuals and societies change over time. Comte’s emphasis on social order and change within and across societies is still useful today because many sociolo gists examine the relationships between education and politics (social statics), as well as how such interconnections change over time (social dynamics).

1-4b Harriet Martineau

empirical information that is based on observations, experiments, or other data collection rather than on ideology, religion, intuition, or conventional wisdom.

social facts aspects of social life, external to the individual, that can be measured.

Harriet Martineau (1802–1876), an English author, pub lished several dozen books on a wide range of topics in social science, politics, literature, and history. Her translation and condensation of Auguste Comte’s difficult material for popular consumption was largely responsible for the dissemination of Comte’s work. “We might say, then, that sociology had parents of both sexes” (Adams and Sydie, 2001: 32). She emphasized the importance of systematic data collection through observation and interviews, and an objective analysis of data to explain events and behavior. She also published the first sociology research methods textbook.

Martineau, a feminist and strong opponent of slavery, denounced many aspects of capitalism as alienating and degrading, and criticized dangerous workplaces that often led to injury and death. Martineau promoted improving women’s positions in the workforce through education, nondiscriminatory employment, and training programs. She advocated women’s admission into medical schools and emphasized issues such as infant care, the rights of the aged, suicide prevention, and other social problems (Hoecker-Drysdale, 1992).

After a long tour of the United States, Martineau described American women as being socialized to be subservient and dependent rather than equal marriage partners. She also criticized American and European religious institutions for expecting women to be pious and passive rather than educating them in philosophy and politics. Most scholars, including sociologists, ridiculed and dismissed such ideas as too radical.

Émile Durkheim

Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), a French sociologist and writer, agreed with Comte that societies are characterized by unity and cohesion because their members are bound together by common interests and attitudes. Whereas Comte acknowledged the importance of using scientific methods to study society, Durkheim actually did so by poring over official statistics to test a theory about suicide (Adams

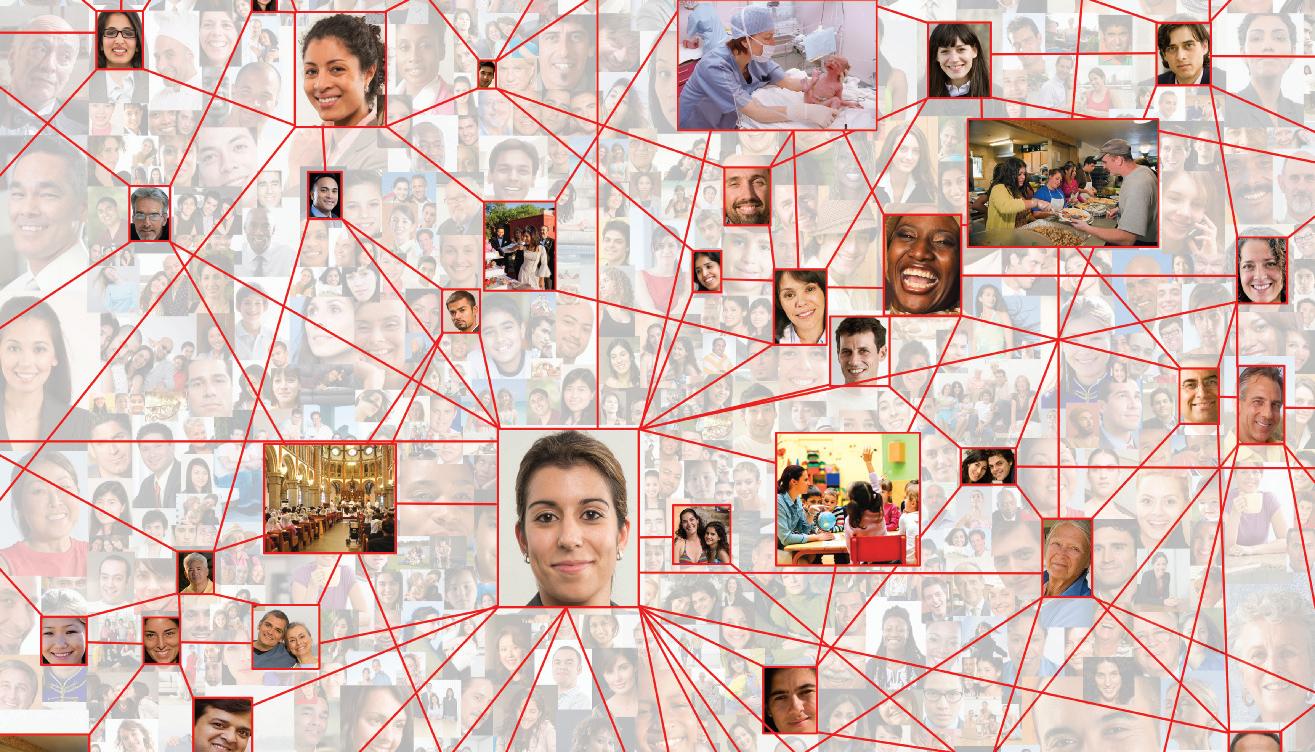

To be scientific, Durkheim maintained, sociology must study social facts—aspects of social life, external to the individual, that can be measured. Sociologists can determine material facts by examining demo graphic characteristics such as age, place of residence, and population size. They can gauge nonmaterial facts, like communication processes, by observing everyday behavior and how people relate to each other (see Chapters 3 to 6). For contemporary sociologists, social facts

The Father of Sociology— Auguste Comte

Harriet Martineau

Creatas Images/Jupiter Images

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Spencer Arnold/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

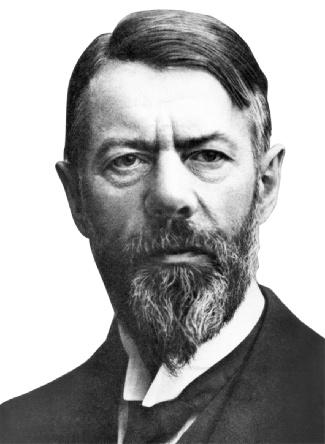

1-4e Max Weber

Max Weber (pronounced VAY-ber; 1864–1920) was a German sociologist, economist, legal scholar, historian, and politician. Unlike Marx’s emphasis on economics as a major factor in explaining society, Weber focused on social organization, a subjective understanding of behavior, and a value-free sociology.

SOCIAL ORGANIZATION

For Weber, economic factors were important, but ideas, religious values, ideologies, and charismatic leaders were just as crucial in shaping and changing societies. He maintained that a complete understanding of society requires an analysis of the social organization and interrelationships among economic, political, and cultural institutions. In his Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, for example, Weber (1920/1958) argued that the self-denial fostered by Calvinism supported the rise of capitalism and shaped many of our current values about working hard (see Chapters 3 and 6).

SUBJECTIVE UNDERSTANDING

Weber posited that an understanding of society requires a “subjective” understanding of behav ior. Such understanding, or verstehen (pronounced fer-SHTAY-en), involves knowing how people perceive the world in which they live. Weber described two types of verstehen. In direct servational understanding, the social scientist observes a person’s facial expressions, gestures, and listens to his/her words. In explanatory understanding, the social scientist tries to grasp the intention and context of the behavior.

Is It Possible to Be a Value-Free Sociologist?

Max Weber was concerned about popular professors who took political positions that pleased many of their students. He felt that these professors were behaving improperly because science, including sociology, must be “value free.” Faculty must set their personal values aside to make a contribution to society. According to a sociologist who agrees with Weber, sociology’s weakness is its tendency toward moralism and ideology:

Many people become sociologists out of an impulse to reform society, fight injustice, and help people. Those sentiments are noble, but unless they are tempered by skepticism, discipline, and scientific detachment, they can be destructive. Especially when you are morally outraged and burning with a desire for action, you need to be cautious (Massey, 2007: B12).

Some argue that being value free is a myth because it’s impossible for a scholar’s attitudes and opinions to be totally divorced from her or his scholarship (Gouldner, 1962). Many sociologists, after all, do research on topics that they consider significant and about which they have strong views.

Others maintain that one’s values should be passionately partisan, should frame research issues, and should improve society (Feagin, 2001). Sociologists

Can sociologists be value free— especially when they have strong feelings about many societal issues? Should they be?

shouldn’t apologize for being subjective in their teaching and research. By staying silent, social scientists “cede the conversation to those with the loudest voices or deepest pockets . . . people with megaphones who spread sensational misinformation” that deprives the public of the best available data (Wang, 2015: A48).

Can sociologists really be value free—especially when they have strong feelings about many societal issues? Should they be?

Max Weber

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

If a person bursts into tears (direct observational understanding), the observer knows what the person may be feeling (anger, sorrow, and so on). An explana tory understanding goes a step further by spelling out the reason for the behavior (rejection by a loved one, frustration if you lose your smartphone, humiliation if a boss yells at you in public).

VALUE-FREE SOCIOLOGY

One of Weber’s most lasting and controversial views was the notion that sociologists must be as objective, or “value free,” as possible in analyzing society. A researcher who is value free is one who separates her or his personal values, opinions, ideology, and beliefs from scientific research.

During Weber’s time, the government and other organizations demanded that university faculty teach the “right” ideas. Weber encouraged everyone to be involved as citizens, but he maintained that educators and scholars should be as dispassionate as possible politically and ideologically. The task of the teacher, Weber argued, was to provide students with knowledge and scientific experience, not to “imprint” the teacher’s personal political views and value judgments (Gerth and Mills, 1946). “Is It Possible to Be a Value-Free Sociologist?” examines this issue further.

1-4f Jane Addams

Jane Addams (1860–1935) was a social worker who cofounded Hull House, one of the first settlement houses in Chicago that served the neighborhood poor. An active reformer throughout her life, Jane Addams was a leader in the women’s suffrage movement and, in 1931, was the first American woman to be awarded the Nobel Peace Prize for her advocacy of negotiating, rather than waging war, to settle disputes.

Sociologist Mary Jo Deegan (1986) describes Jane Addams as “the greatest woman sociologist of her day.” However, she was ignored by her colleagues at the University of Chicago (the first sociology department established in the United States in 1892) because discrimination against women sociologists was “rampant” (p. 8).

Despite such discrimination, Addams published articles in many popular

and scholarly journals, as well as many books on the everyday life of urban neighborhoods, especially the effects of social disorganization and immigration. Much of her work contributed to symbolic interaction, an emerging school of thought that you’ll read about shortly. One of Addams’ greatest intellectual legacies was her emphasis on applying knowledge to everyday problems. Her pioneering work in criminology included ecological maps of Chicago that were later credited to men (Moyer, 2003).

1-4g W. E. B. Du Bois

W. E. B. Du Bois (pronounced Do-BOICE; 1868–1963) was a prominent black sociologist, writer, editor, social reformer, and orator. The author of almost two dozen books on Africans and black Americans, Du Bois spent most of his life responding to the critics and detractors of black life. He was the first African American to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard University, but once remarked, “I was in Harvard but not of it.”

Du Bois helped found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) and edited its journal, Crisis. The problem of the twentieth century, he wrote, is the problem of the color line. Du Bois believed that the race problem was one of ignorance, and advocated a “cure” for prejudice and discrimination. Such cures included promoting black political power and civil rights and providing blacks with a higher education rather than funneling them into techical schools.

These and other writings were unpopular at a time when Booker T. Washington, a well-known black educator, encouraged black people to be patient instead of demanding equal rights. As a result, Du Bois was dismissed as a radical by his contemporaries but was rediscovered by a new generation of black scholars during the 1970s and 1980s. Among his many contributions, Du Bois examined the oppressive effects of race and social class, advocated women’s rights, and played a key role in reshaping black–white relations in America (Du Bois, 1986; Lewis, 1993).

All of these and other early thinkers agreed that people are transformed by each other’s actions, social patterns, and historical changes. They and other scholars shaped contemporary sociological theories.

Jane Addams with a child at Hull House

Wallace Kirkland//Time Life Pictures/Getty Images

social classes) rise. Thus, mergers might be functional for people at the upper end of the socioeconomic ladder, but dysfunctional for those on the lower rungs.

SOCIAL INEQUALITY

Unlike functionalists, conflict theorists see society not as cooperative and harmonious, but as a system of widespread inequality. For conflict theorists, there’s a continuous tension between the haves and the have-nots, most of whom are children, women, minorities, people with low incomes, and the poor.

Many conflict theorists focus on how those in power—typically wealthy white Anglo-Saxon Protestant males (WASPs)—dominate political and economic decision making in U.S. society. This group controls a variety of institutions—like education, criminal justice, and the media—and passes laws that benefit primarily people like themselves (see Chapters 8 and 11).

CRITICAL EVALUATION

Conflict theory explains how societies create and cope with disagreements. However, some have criticized conflict theorists for overemphasizing competition and coercion at the expense of order and stability. Inequality exists and struggles over scarce resources occur, critics agree, but conflict theorists often ignore cooperation and harmony. Voters, for example, can boot dominant white males out of office and replace them with women and minority group members. Critics also point out that the have-nots can increase their power through negotiation, bargaining, lawsuits, and strikes.

1-5c Feminist Theories

Among other manifest functions, schools transmit knowledge and prepare children for adult economic roles. Among their latent functions, schools provide matchmaking opportunities. What are some other examples of education’s manifest and latent functions?

and 1970s, men—who dominated universities and scholarship—were largely “blind to the importance of gender” (Kramer and Beutel, 2015: 17).

Feminist scholars agree with contemporary conflict theorists that much of society is characterized by tension and struggle, but feminist theories go a step further by focusing on women’s social, economic, and political inequality. The theories maintain that women often suffer injustice primarily because of their gender, rather than personal inadequacies like low educational levels or not caring about success. Feminist scholars assert that people should be treated fairly and equally regardless not only of their sex but also of other characteristics such as their race, ethnicity, national origin, age, religion, class, sexual orientation, or disability. They emphasize that women should be freed from traditionally oppressive expectations, constraints, roles, and behavior (see Reger, 2012).

FOCUSING ON GENDER

“Sometimes the best man for the job isn’t.”

Author Unknown

Feminist scholars have documented women’s historical exclusion from most sociological analyses (see, for example, Smith, 1987, and Adams and Sydie, 2001). Before the 1960s women’s movement in the United States, very few sociologists published anything about gender roles, women’s sexuality, fathers, or intimate partner violence. According to sociologist Myra Ferree (2005: B10), during the 1970s, “the Harvard socialscience library could fit all its books on gender inequalities onto a single halfshelf.” Because of feminist scholars, many researchers—both women and men—now routinely include gender as an important research variable on both micro and macro levels.

You’ll recall that influential male theorists generally overlooked or marginalized early female sociologists’ contributions. Until the feminist activism of the 1960s

Globally, except for some predominantly Muslim countries, solid majorities of both women and men support gender equality and agree that women should be able to work outside the home. When jobs are scarce, however, many women and men believe

feminist theories examine women’s social, economic, and political inequality.

of the most important of these shared meanings is the definition of the situation, or the way we perceive reality and react to it. Relationships often end, for example, because people view emotional closeness differently (“We broke up because my partner wanted more sex. I wanted more communication.”). We typically learn our definitions of the situation through interaction with significant others—especially parents, friends, relatives, and teachers—who play an important role in our socialization (as you’ll see in Chapters 4 and 5).

CRITICAL EVALUATION

Unlike other theorists, symbolic interactionists show how people play an active role in shaping their lives on a micro level. One of the most common criticisms is that symbolic interaction overlooks the widespread impact of macro-level factors (e.g., economic forces, social movements, and public policies) on our everyday behavior and relationships. During economic downturns, for example, unemployment and ensuing financial problems create considerable interpersonal conflict among couples and families (see Chapters 11 and 12). Symbolic interaction rarely considers such macro-level changes in explaining everyday behavior.

A related criticism is that interactionists sometimes have an optimistic and unrealistic view of people’s everyday choices. Most of us enjoy little flexibility in our daily lives because deeply embedded social

arrangements and practices benefit those in power. For instance, people are usually powerless when corporations transfer jobs overseas or cut the pension funds of retired employees.

Some also believe that interaction theory is flawed because it ignores the irrational and unconscious aspects of human behavior (LaRossa and Reitzes, 1993). People don’t always consider the meaning of their actions or behave as reflectively as interactionists assume. Instead, we often act impulsively or say hurtful things without weighing the consequences of our actions or words.

1-5e Other Theoretical Approaches

Table 1.3 summarizes the major sociological perspectives that you’ve just read about. However, new theoretical perspectives arise because society is always changing. For example, postmodern theory analyzes contemporary societies that are characterized by postindustrialization, consumerism, and global communications.

Sociology, like other social sciences, has subfields. The subfields—such as socialization, deviance, and social stratification—offer specific theories that reinforce and illustrate functionalist, conflict, feminist, and interactionist approaches. No single theory explains social life completely. Each theory, however, provides different insights that guide sociological research, the topic of Chapter 2.

For many people, a diamond, especially in an engagement ring, signifies love and commitment. For others, diamonds represent Western exploitation of poor people in Africa who are paid next to nothing for their backbreaking labor in mining these stones.

Spring break is all about beer fests, wet T-shirt contests, frolicking on the beach, and hooking up, right? Maybe not. A national survey found that 70 percent of college students stay home with their parents, and 84 percent of those who throng to vacation spots report consuming alcohol in moderation (The Nielsen Company, 2008). If you suspect that these numbers are too high or too low and wonder how the survey was done, you’re thinking like a researcher, the focus of this chapter.

WHAT DO YOU THINK?

People can find data to support any opinion they have.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 strongly agree strongly disagree

2-1 HOW DO WE KNOW WHAT WE KNOW?

Much of our knowledge is based on tradition, a handing down of statements, beliefs, and customs from generation to generation (“The groom’s parents should pay for the wedding rehearsal dinner”). Another common source of knowledge is authority, a socially accepted source of information that includes “experts,” parents, government officials, police, judges, and religious leaders (“My mom says that . . .” or “According to the American Heart Association . . .”).

Knowledge based on tradition and authority simplifies our lives because it provides us with basic rules about socially and legally acceptable behavior. The information can be misleading or wrong, however. Suppose a 2-yearold throws a temper tantrum at a family barbecue. One adult comments, “What that kid needs is a smack on the behind.” Someone else immediately disagrees: “All kids go through this stage. Just ignore it.”

Who’s right? To answer this and other questions, sociologists rely on research methods, organized and systematic procedures to gain knowledge about a particular topic. Much research shows, for example, that neither ignoring a problem nor inflicting physical punishment (like spanking) stops a toddler’s bad behavior. Instead, most young children’s misbehavior can be curbed by having simple rules, being consistent in disciplining misbehavior, praising good behavior, and setting a good example (see Benokraitis, 2015).

2-2 WHY IS SOCIOLOGICAL RESEARCH IMPORTANT IN OUR EVERYDAY LIVES?

In contrast to knowledge based on tradition and authority, sociological research is important in our everyday lives for several reasons:

1. It counteracts misinformation. Blatant dishonesty and misinformation spread rapidly through digital communication. In 2015, violent crimes were 77 percent below their 1993 level, but 70 percent of Americans believe that the rate has increased (Gramlich, 2016; Truman and Morgan, 2016). Such unfounded fears—fueled by mass shootings, the media’s focus on crime, powerful lobby groups such as the National Rifle Association, and Donald Trump’s false claim that “inner city crime is reaching record levels”—are partly responsible for the growth of gun ownership in the past 20 years (Cohn et al., 2013; see also Chapter 7).

2. It exposes myths. According to many newspapers and television shows, suicide rates are highest during the Christmas holidays. In fact, suicide rates are lowest in December and highest in the spring and fall (but the reasons for these peaks are unclear). Another myth is that more women are victims of domestic violence on Super Bowl Sunday than on any other day of the year, presumably because men become intoxicated and abusive. In fact, intimate partner violence rates are high, and consistent, throughout the year (Romer, 2011; “Super Bull Sunday,” 2015).

3. It helps explain why people behave as they do. A recent study predicted that older drivers, particularly those age 70 and older, would be more likely than younger drivers to have fatal crashes,

research methods organized and systematic procedures to gain knowledge about a particular topic.

“Facebook Causes 20 Percent of Today’s Divorces.” What?!

The founder and self-described leader of the United Kingdom’s online divorce site (Divorce-Online) sent out a press release titled “Facebook Is Bad for Your Marriage—Research Finds,” and claimed that Facebook causes 20 percent of today’s divorces. News media around the world ran stories about this press release with headlines such as “Facebook to Blame for Divorce Boom.” You’ll see in Chapter 12 that there’s no divorce boom, so where did the 20 percent number come from?

In 2009, the managing director of DivorceOnline scanned its online divorce petition database

but found the opposite (Braitman et al., 2011). The researchers couldn’t explain why their prediction turned out to be false. Sociologists posit that older Americans are less likely to have fatal crashes because many avoid driving at night or during bad weather, and they’re much less likely than younger drivers to use cell phones or text while driving (Halsey, 2010).

4. It affects social policies. According to the captain of a large North Carolina Police Department, “Research dictates everything that officers do, whether we realize it or not,” in reducing crime. Examples include tracking criminal activity in highrisk locations, implementing research-based policies in training patrol officers and detectives, and managing limited resources more efficiently (Nolette, 2015).

for use of the word Facebook , and found 989 instances in about 5,000 petitions. Divorce-Online never said that the petitions were only those filed by members of the American Academy of Matrimonial Lawyers, who comprise a very small percentage of all divorce attorneys. Two years later, many Internet sites and blogs were still spreading the fiction that “Facebook Causes Divorce” (see Bialik, 2011). In reality, as you’ll see in Chapter 12, there are a number of interrelated macro- and micro-level reasons for divorce; there’s no single “cause,” much less Facebook.

scientific method a body of objective and systematic techniques used to investige phenomena, acquire knowledge, and test hypotheses and theories.

5. It sharpens critical thinking skills. Many Americans, particularly women, rely on talk shows for information on a number of topics. Oprah Winfrey has featured and applauded guests who maintained, among other things, that children contract autism from the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccinations they receive as babies; that fortune cards can help people diagnose their illnesses; and that people can wish away cancer (Kosova and Wingert, 2009; Clemmons et al., 2015; see also “Clueless,” 2014, for other recent examples of “celebrity bogus science”).

All of these claims are false, and as you’ll see in Chapter 14, endanger our health.

RTimages/Shutterstock.com

A fact-checking website found that, during the 2016 presidential campaign, only 25 percent of Hillary Clinton’s and 4 percent of Donald Trump’s statements were true (PolitiFact, 2016). Fake news— misinformation that deliberately misleads people for financial, political, or other gain—has been around for a long time. About 84 percent of Americans are confident that they can identify false news (Barthel et al., 2016).

Many of us, however, are susceptible to confirmation bias, a tendency to embrace and recall information that confirms our beliefs and ignores or downplays contrary evidence. The scientific method, which requires critical thinking skills that you read about in Chapter 1, strengthens our ability to separate fact from fiction, but do people always believe scientific findings?

2-3 THE SCIENTIFIC METHOD

Sociologists rely on the scientific method, a body of objective and systematic techniques used to investigate phenomena, acquire knowledge, and test hypotheses and theories. The techniques include careful data collection, exact measurement, accurate recording and analysis of the findings, thoughtful interpretation of results, and, when appropriate, generalization of the findings to a larger

group. Before collecting any data, however, social scientists must grapple with a number of research-related issues. Let’s begin with concepts, variables, and hypotheses.

2-3a Concepts, Variables, and Hypotheses

A basic element of the scientific method is a concept an abstract idea, mental image, or general notion that represents some aspect of the world. Some examples of concepts are “blood pressure,” “religion,” and “marriage.”

Because concepts are abstract, scientists use variables to measure (operationalize) concepts. A variable is a characteristic that can change in value or magnitude under different conditions. Variables can be attitudes, behaviors, or traits (e.g., ethnicity, age, and social class).

An independent variable is a characteristic that has an effect on the dependent variable, the outcome. A control variable is a characteristic that is constant and unchanged during the research process.

Scientists can simply ask a research question (“Why are people poor?”), but they usually begin with a hypothesis—a statement of the expected relationship

Figure 2.1 Deductive and Inductive Approaches

between two or more variables—such as “Unemployment increases poverty.” In this example, “unemployment” is the independent variable and “poverty” is the dependent variable.

Researchers might also use control variables, like education, to explain the relationship between unemployment and poverty. For example, people with at least a college degree generally have lower poverty rates than those with lower educational levels because the former are less likely to experience long periods of unemployment.

2-3b Deductive and Inductive

Reasoning

Deduction and induction are two different but equally valuable approaches in examining the relationship between variables. Generally, deductive reasoning begins with a theory, prediction, or general principle that is then tested through data collection. An alternative mode of inquiry, inductive reasoning, begins with specific observations, followed by data collection, a conclusion about patterns or regularities, and the formulation of hypotheses that can lead to theory construction (Figure 2.1).

concept an abstract idea, mental image, or general notion that represents some aspect of the world.

variable a characteristic that can change in value or magnitude under different conditions.

independent variable a characteristic that has an effect on the dependent variable.

dependent variable the outcome that may be affected by the independent variable.

control variable a characteristic that is constant and unchanged during the research process.

hypothesis a statement of the expected relationship between two or more variables.

deductive reasoning begins with a theory, prediction, or general principle that is then tested through data collection.

inductive reasoning begins with a specific observation, followed by data collection, a conclusion about patterns or regularities, and the formulation of hypotheses that can lead to theory construction.